François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXVII: The London Embassy: 1822

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXVII: Chapter 1: The year 1822 – First despatches from London

- Book XXVII: Chapter 2: A conversation with George IV regarding Monsieur Decazes – The nobility of our diplomacy under the Legitimacy – The Parliamentary Session

- Book XXVII: Chapter 3: English Society

- Book XXVII: Chapter 4: More despatches

- Book XXVII: Chapter 5: The resumption of Parliamentary activity – A ball given on behalf of the Irish – A duel between the Duke of Bedford and the Duke of Buckingham – Dinner at Royal Lodge – The Marchioness of Conyngham and her secret

- Book XXVII: Chapter 6: Portraits of the Ministers

- Book XXVII: Chapter 7: More of my despatches

- Book XXVII: Chapter 8: Discussion about the Congress of Verona – A letter to Monsieur Montmorency; his reply which allows me to sense a refusal – Monsieur Villèle’s letter is more favourable – I write to Madame de Duras – A note from Monsieur de Villèle to Madame de Duras

- Book XXVII: Chapter 9: The death of Lord Londonderry

- Book XXVII: Chapter 10: A new letter from Monsieur de Montmorency – A trip to Hartwell – A note from Monsieur de Villèle announcing my nomination to the Congress

- Book XXVII: Chapter 11: The end of the old England – Charlotte Reflections – I leave London

Book XXVII: Chapter 1: The year 1822 – First despatches from London

Revised: December 1846.

BkXXVII:Chap1:Sec1

It was in London, in 1822, that I wrote the longest successive instalment of my Memoirs, containing my voyage to America, my return to France, my marriage, my crossing to Paris, my emigration to Germany with my brother, and my residence and misfortunes in England from 1793 to 1800. There will be found my description of England as it was; and when I revisited it all during my embassy in 1822, the changes which had taken place in the manners and people since 1793, at the century’s end, struck me forcibly; I was naturally drawn to compare what I saw in 1822, with what I had seen during my seven year exile across the Channel.

Thus the things which I would have set down here, under the appropriate dates covering my diplomatic mission, have already been anticipated. The prologue to Book VI told you of my emotion, the feelings recalled by the sight of those places dear to my memory; but perhaps you have not read that book? You have done well. It is enough now that I have told you of the place where the gaps which must exist in this present recital of my London embassy have been filled. Behold me then, writing in 1839, among the dead of 1822, and the dead who preceded them in 1793.

In London, in the month of April 1822, I was a hundred and fifty miles from Madame Sutton. I walked in Kensington Park, bearing my recent impressions, and the distant past of my youth: confusions in time which produced in me confusions of memory; life which consumes itself mingles, like the burning of Corinth, the molten bronze of the statues of the Muses and of Love, the tripods and the tombs.

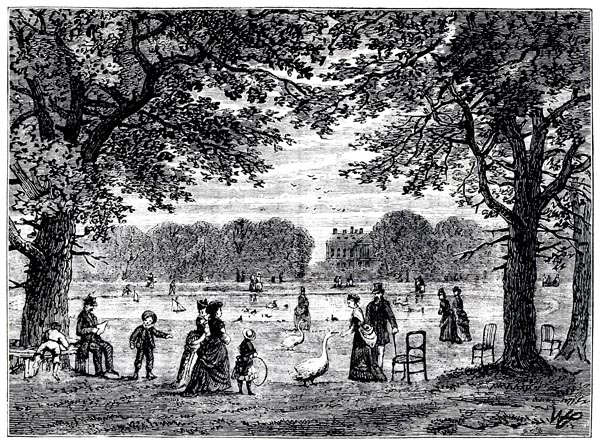

‘The Round Pond, Kensington Gardens’

Old and New London: a Narrative of its History, its People, and its Places - Walter Thornbury (p169, 1873)

Internet Archive Book Images

The parliamentary vacation was in progress when I reached my residence on Portland Place. The Under-Secretary of State, Monsieur Planta, invited me, on behalf of the Marquis of Londonderry, to dinner at North Cray, the noble lord’s estate. That villa, with a large tree before the windows on the garden side, overlooked the meadows; woody undergrowth on the hills distinguished this site from the ordinary English view. Lady Londonderry was very fashionable in her role as a Marchioness and the wife of the Prime Minister.

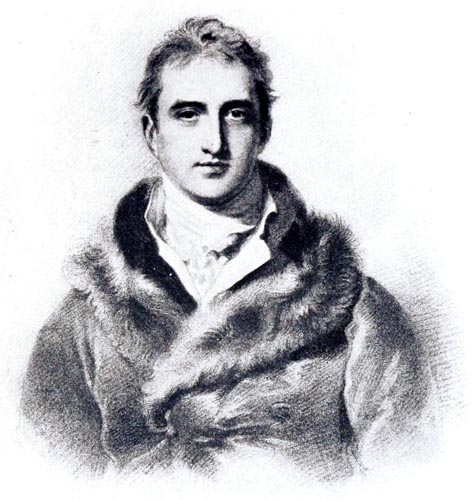

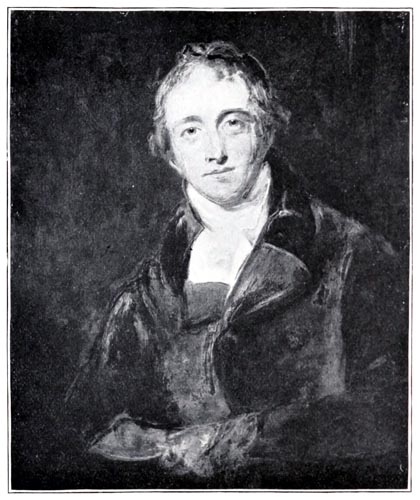

‘Robert Stuart, Viscount Castlereagh 2nd Marquess of Londonderry (After the Painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence)’

Wellington, Soldier and Statesman, and the Revival of the Military Power of England - William O'Connor Morris (p52, 1904)

Internet Archive Book Images

My despatch of the 12th of April, no.4, details my first meeting with Lord Londonderry; it touched on matters which were to concern me.

‘London, 12th of April 1822.

Monsieur le Vicomte,

I went, the day before yesterday, Wednesday the 10th, to North Cray. I have the honour to send you an account of my conversation with the Marquis of Londonderry. It lasted an hour and a half, before dinner, and we resumed later, but less informally, since we were not alone.

Lord Londonderry first asked for news of the King’s health, with an insistence which visibly declared a political interest; reassured by me on that point, he passed to the government: “It is strengthened,” he said to me. I replied; “It was never weakened, and as it adheres to party, it will remain in control as long as that party dominates the two Chambers.” That led us to discuss the elections: he seemed struck by what I said regarding the advantage of a summer session in order to restore order to the financial year; he had not fully understood till then the state of the matter.

The war between Russia and Turkey then became the subject of our conversation. Lord Londonderry, in speaking to me of soldiers and arms, appeared to me to hold the opinion of our previous government regarding the danger to us represented by massing our troops; I rejected that idea, and maintained that there was nothing to fear by our sending French soldiers into combat; that none would be disloyal faced with the enemy flag; that our army had just been strengthened; that it would be tripled tomorrow, if that were necessary, without the least trouble; that indeed some junior officers might shout “Long Live the Charter!” in their garrisons, but that our grenadiers always shouted “Long Live the King!” on the battlefield.

I do not know if high politics has made Lord Londonderry forget about the slave trade; he said not a word to me about it. Changing the subject, he spoke to me of a message from the President of the United States committing Congress to recognise the independence of the Spanish Colonies. “Commercial interests,” I said, “may draw some benefit from it, but I doubt that political interests will find the same profit in it: there are enough Republican ideas in the world already. To add to the weight of those ideas, is to compromise further the fate of the European monarchies.” Lord Londonderry concurred with me, and said these notable words: “As for us (the English), we are not disposed to recognise revolutionary governments.” Was he being sincere?

It was necessary, Monsieur le Vicomte, to relate so important a conversation to you verbatim. However, we should not mislead ourselves: the English will sooner or later recognise the independence of the Spanish Colonies; public opinion and foreign trade will require it. They have already gone to considerable expense, in the last three years, establishing secret relations with the insurgent provinces north and south of the Isthmus of Panama.

In summary, Monsieur le Vicomte, I found the Marquis of Londonderry a man of intellect, of doubtful frankness perhaps; a man still imbued with the old system of government; a man accustomed to diplomatic subservience and surprised, without being offended, by a nobler mode of speech from France; a man finally who cannot avoid a kind of astonishment in speaking to one of those Royalists who, for the last seven years, have been represented to him as fools or madmen.

I have the honour, etc.’

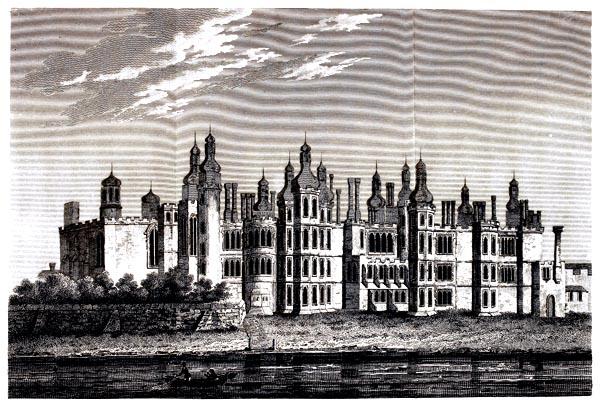

‘Wynyard Park, Principal Residence of the Marquis of Londonderry’

The County Seats of the Noblemen and Gentlemen of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol 02 - Francis Orpen Morris (p38, 1866)

The British Library

With these general matters were mixed, as in all embassies, specific transactions. I had to attend to a request from the Duke of Fitzjames, regarding the proceedings of the boat Eliza-Ann, the depredations of Jersey fishermen among the Granville oyster-beds, etc. etc. I regretted being obliged to dedicate a small compartment of my brain to claimants’ dossiers. Though one rummages one’s memory, it is hard to recall Messieurs Usquin, Coppinger, Deliège and Piffre. But, in a few years time, will we be any more well-known than these gentlemen? A certain Monsieur Bonnet having died in America, all the Bonnets in France wrote to me to claim the succession; those tormenters write to me yet! They might have left me in peace, by now. I have replied politely to them that the small accident of the fall of the throne having occurred, I am no longer concerned with all that: they stick tight, and wish to inherit at all costs.

As for the East, it was a matter of recalling the various ambassadors from Constantinople. I foresaw that the English would not follow the actions of the Continental Alliance: I told Monsieur de Montmorency so. The rupture that had been feared between Russia and the Porte did not occur: Alexander’s moderation delayed the event. I expended in this regard a vast amount of to-ing and fro-ing, sagacity and reason; I wrote many despatches, which are mouldering in our archives, giving an account of events that did not happen. I had at least the advantage over my colleagues of placing no importance on my efforts; I saw them, unconcernedly, swallowed in oblivion with all the lost thoughts of men.

Parliament began its session once more on the 17th of April; the King returned on the 18th, and I was presented to him on the 19th. I gave an account of this presentation in my despatch of the 19th; it ended thus:

‘His Majesty, with his rich and varied conversation, did not leave me room to say anything of those matters with which our King has specially entrusted me; but the imminent and favourable opportunity of a fresh audience presents itself.’

‘King George IV’

England in the nineteenth century - Mary Elizabeth Latimer (p55, 1894)

The British Library

Book XXVII: Chapter 2: A conversation with George IV regarding Monsieur Decazes – The nobility of our diplomacy under the Legitimacy – The Parliamentary Session

BkXXVII:Chap2:Sec1

The thing which the King had particularly charged me to raise with George IV concerned Monsieur le Duc Decazes. I fulfilled the obligation a little later: I told George IV that Louis XVIII was troubled by the coolness with which the Ambassador of His Very Christian Majesty had been received. George IV replied:

‘Listen, Monsieur de Chateaubriand, and I will make you a confession: Monsieur Decaze’s appointment did not please me; I was presented with it somewhat cavalierly. My friendship for the King of France alone made me tolerate a favourite who had no other merit than that of his attachment to his master. Louis XVIII has often relied on my goodwill, with good reason; but I could not permit the indulgence of treating Monsieur Decazes with a distinction which would have harmed England. However, tell your King that I am concerned by what he has charged you with telling me, and that I will always be happy to show him my true attachment.’

Emboldened by these words, I made George IV aware of all that came to mind in favour of Monsieur Decazes. He replied, partly in French, partly in English: ‘À merveille! You are a true gentleman.’ On my return to Paris, I recounted this conversation to Louis XVIII: he seemed grateful to me. George IV had spoken like a noble prince but also like an independent spirit; he was without bitterness because he was thinking of other things. It did not do however to gamble with him except in moderation. One of his gaming friends had bet that he would ask George IV to pull the bell-cord and that George IV would obey. Indeed, George IV did pull the cord and said to the gentleman of his establishment: ‘Show Monsieur the door.’

The idea of returning our armies to power and splendour possessed me continually. I wrote to Monsieur de Montmorency, on the 13th of April: ‘An idea has come to me, Monsieur the Vicomte, which I submit to your judgement: would you find me at fault if in conversation with Prince Esterhazy, I were to tell him that if Austria should need to withdraw a section of its troops from Piedmont, we might replace them?’ Rumours which spread of an intended mobilisation of our troops in the Dauphiné offered me a favourable pretext. I had proposed to the former minister to send a garrison to Savoy, during the revolt of June 1821 (see one of my despatches from Berlin). He rejected the measure, and I think that in doing so he made a capital error. I persist in believing that the presence of French troops in Italy would have produced a fine effect on public opinion, and that the King’s government would have gained much glory from it.

Proofs abound of the nobility of our diplomacy during the Restoration. What did it matter to anyone? Did I not read only this morning, in a left-wing newspaper, that the Alliance had forced us to be its policemen and to make war in Spain, when the records of the Congress of Verona exist, when the diplomatic documents show in an irrefutable manner that all Europe, with the exception of Russia, did not want war; that not only did she not want it, but that England openly rejected it, and Austria thwarted us in secret by less noble measures? That will not prevent some new lie tomorrow; no one will give themselves the trouble of investigating the matter, of reading that which they speak of knowingly without having read! Every lie repeated becomes a truth: one cannot have too much contempt for human opinion.

Lord John Russell put forward, on the 25th of April, in the Commons, a motion regarding the state of national representation in parliament: Mr Canning opposed it. The latter in turn proposed a bill to repeal part of the act which deprived Catholic Peers of the right to vote and sit in the Lords. I was present at the sessions in the Lords, on the Woolsack, where the Lord Chancellor made me sit. Mr Canning was present in 1822 at the session of the Chamber of Peers which finally rejected his bill; he was offended by a phrase of the aged Lord Chancellor; the latter, speaking of the author of the bill, exclaimed disdainfully: ‘We are assured that he is leaving for India: ah! Let him go, this fine gentleman, let him go! Farewell!’ Mr Canning said to me on emerging: ‘I will see him again.’

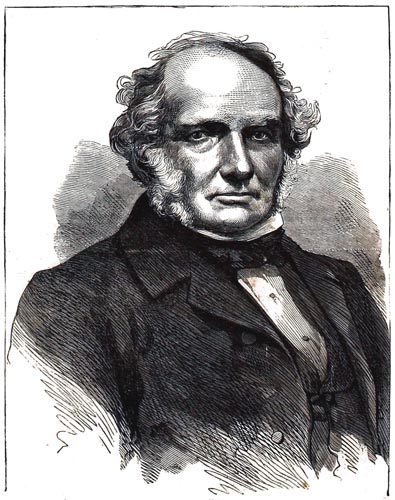

‘Earl John Russell’

Harper's Weekly - John Bonner et al. (p707, 1857)

Internet Archive Book Images

Lord Holland spoke very well, without however recalling Mr Fox. He twisted himself about, so that he often presented his back to the assembly and addressed his sentences to the wall. They shouted: ‘Hear! Hear!’ No one was shocked by his eccentricity.

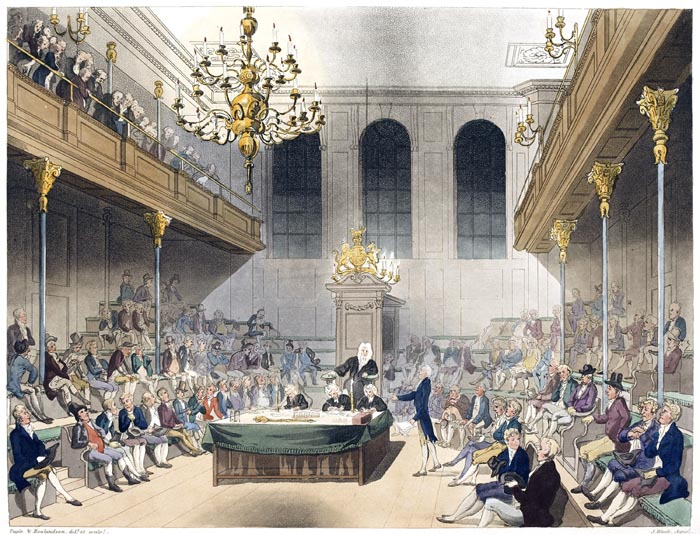

‘House of Commons’

The Microcosm of London - Thomas Rowlandson and A. C. Pugin (1808 - 1811)

The British Library

In England everyone expresses themselves as they wish; formal advocacy is unknown; nothing is consistent in the voices or declamation of the orators. They are listened to patiently; no one is shocked if the speaker lacks ability; let him stammer, let him drone on, let him struggle to find the words, he has nevertheless made a fine speech if he has said something sensible. This variability of men, left as nature made them, ends by being agreeable; it breaks the monotony. It is true that only a small number of Lords and Members of the Commons got to their feet. We, always on stage, we hold forth and gesticulate, we serious puppets. It was a useful lesson for me that passage from the silent and secretive monarchy of Berlin to the noisy public monarchy of London: one might receive some instruction by comparing two nations at either end of the scale.

Book XXVII: Chapter 3: English Society

BkXXVII:Chap3:Sec1

The arrival of the King, the return of Parliament, the opening of the festive season, mingled duty, business and pleasure; one might meet the Ministers at Court, at a ball, or in Parliament. To celebrate the official anniversary of His Majesty’s birth, I dined with Lord Londonderry, I dined on the Lord Mayor’s barge, which sailed as far as Richmond: I prefer the miniature Bucentaur in the Venice Arsenal, bearing only a memory of the Doges and a Virgilian name. Formerly as an émigré, lean and half-naked, I amused myself, though no Scipio, with throwing stones into the water, along that shoreline grazed by the Lord Mayor’s broad and well-lined barge.

‘Richmond Palace’

The Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth - John Nichols (p434, 1823)

Internet Archive Book Images

I also dined in the East End with Monsieur Rothschild of London, younger brother of Salomon: where did I not dine? The roast-beef had as imposing a presence as the Tower of London; the fish were so large one could not see as far as their tails; ladies, whom I only saw there, sang like Abigail. I drank Tokay, not far from the places where I drank water straight from the jug while almost dying of hunger; reclining in the depths of my comfortable carriage, on the silk-covered padding, I gazed at Westminster Abbey in which I had spent the night imprisoned, and around which I would walk, all muddy, with Hingant and Fontanes. My residence, which cost me 30,000 francs to rent, may be compared with the attic I lived in with my cousin La Bouëtardais, when, in a red robe, he played the guitar on an uncomfortable camp bed, which I had made space for next to my own.

There was no longer any question of those émigré hops where we danced to the sound of a violin played by a Councillor of the Breton Parliament; it was Almack’s, with Colinet as conductor, that provided my pleasures; a public ball-room under the patronage of the great ladies of the West End. There the old and young dandies met. Among the old the conqueror of Waterloo shone, who paraded his glory to set a trap for the ladies during the quadrilles; at the head of the younger ones Lord Clanwilliam was prominent, the son, it was said, of the Duc de Richelieu. He did wonderful things: he rode his horse to Richmond, and returned to Almack’s, having fallen off twice. He had a certain trick of speaking in the manner of Alcibiades, which delighted. Fashions in words, affectations of language and pronunciation, changed in London high society with almost every Parliamentary session: a straightforward man is quite dumbfounded at not understanding English, when he understood it perfectly six months previously. In 1822, the fashionable were obliged to present themselves, at first sight, as ill and unhappy; they had to possess something negligent about the person, long nails, a partial beard, not shaved, but allowed to grow a little, neglectfully, during their preoccupation with despair; locks of straggling hair; a profound gaze, sublime, errant and fatal; lips curled in contempt of the human species; the heart wearied, Byronic, filled with the disgust and mystery of existence.

Today that is all past: the dandy must possess a conquering, careless, insolent air; he must though care for his appearance, cultivate a moustache, or a beard trimmed as round as a ruff in the age of Elizabeth I, or like a radiant sun disc; he reveals his proud independence of character by keeping his hat on his head, lounging on a sofa, stretching his booted legs out under the noses of the admiring ladies seated on chairs around him; he rides with a crop which he holds upright like a candlestick, indifferent to the horse which chances to be between his legs. His health needs to be perfect, and his soul filled with half a dozen joys or so. Some radical dandies, the most advanced, sport a pipe.

‘Colley Cibber as Lord Foppington, Engraved in Mezzotint by R. B. Parkes from the Painting by J. Grisoni’

Days of the Dandies (p144, 1900)

Internet Archive Book Images

But doubtless, all this has changed at the very moment I set out to describe it. They say the dandy of today must not be aware of whether he exists or no, whether society is there, whether it contains ladies, and whether he should greet his fellow man. Is it not strange to find the original of the dandy in the reign of Henri III: ‘Those pretty darlings,’ says the author of The Isle of Hermaphrodites, ‘wear their hair long, curled and re-curled, rising above their little velvet bonnets, like women, and the ruffs of their linen shirts of starched finery, and half a foot long, such that seeing their heads above their ruffs, they look like St John the Baptist, with his head on a platter.’

They go to present themselves at Henry III’s apartments, ‘swinging their body, head and limbs, so one would think they would fall headlong at the slightest obstacle. They find this manner of walking finer than any other.’

The English are all mad by nature or by fashion.

BkXXVII:Chap3:Sec2

Lord Clanwilliam soon passed by: I met him again at Verona; he became an Ambassador in Berlin after me. We followed the same path for an instant, though we did not walk at the same pace.

Nothing succeeded, in London, like insolence, witness Comte d’Orsay, the brother of the Duchesse de Guiche: he galloped in Hyde Park, leapt the fences, gamed, rubbed shoulders informally with the dandies: he had a success without equal, and, to complete it all, ended by conquering a whole family, father, mother and children.

The ladies most in fashion pleased me least; one of them however, Lady Gwydir, was delightful; she was like a Frenchwoman in her style and manners. Lady Jersey still preserved her beauty. I met the Opposition at her house. Lady Conyngham belonged to that Opposition, and the King himself kept a secret fondness for his former friends. Among the noted patronesses of Almack’s was the Ambassadress of Russia.

She, the Countess von Lieven, had various quite ridiculous affairs involving Madame d’Osmond and George IV. As she was daring and was regarded as being in favour, she had become extremely fashionable. She was thought to show spirit, because her husband was supposed to lack it; which was untrue: Monsieur de Lieven was wholly superior to Madame. Madame de Lieven, of sharp and unpleasant features, is a common woman, wearisome, and arid, who has only one form of conversation, vulgar politics; moreover, she knows nothing, and hides her poverty of ideas beneath an abundance of words. When she finds herself among men of worth, her sterility silences her; she decks out her nullity with an air of superior ennui, as if she has the right to be bored; reduced by the ravages of time, and unable to prevent herself meddling in everything, the Dowager of Congresses arrived from Verona to bestow on Paris, with the permission of the magistrates of St Petersburg, an account of the diplomatic puerilities of yesteryear. She chattered about the contents of private correspondence, and appeared prominently in regard to failed marriages. The novices among us were launched into the salons to learn about polite society and the art of keeping secrets; they confided their own, which elaborated on by Madame von Lieven, were transmuted to dull gossip. The Ministers, and those who aspired to become such, are all proud of being the protégés of a lady who had the honour to know Monsieur Metternich in the days when the great man, in order to relieve himself of the weight of business, amused himself by unpicking threads. Ridicule followed Madame von Lieven in Paris. A grave and pedantic theorist fell at Omphale’s feet: ‘Love, you destroyed Troy.’

The days in London were divided thus: at ten in the morning, people went to an orgy, consisting of breakfast in the country; they returned to dine in London; they changed their clothes to parade through Bond Street or Hyde Park; they changed again to dine at seven-thirty; they changed again for the Opera; at midnight, they changed again for a party or a reception! What an enchanting life! I would have preferred the galleys a hundred times over. The acme of good taste was, after being unable to penetrate the ante-rooms of a private ball, to remain on the staircase blocked by the crowd, and find oneself face to face with the Duke of Somerset; a blessing which I once attained. The new breed of English people is infinitely more frivolous than us; their heads are turned by a show: if the Paris executioner arrived in London he would drive England wild. Did not Marshal Soult fill the ladies, with enthusiasm, like Blücher, whose moustache they kissed? Our Marshal, who is no Antipater, Antigonus, Seleuceus, Antiochus or Ptolemy, no royal general of Alexander’s, is a distinguished soldier, who pillaged Spain while making war, and from whom the Capuchins bought their lives with their paintings. But it is true that he published, in March 1814, a furious proclamation against Bonaparte, whom he welcomed in triumph a few days later: he has since performed his Easter Duty at St Thomas Aquinas. In London they show an old pair of his boots for a shilling.

Everyone famous soon visits the banks of the Thames and goes away again. In 1822 I found that great city full of memories of Bonaparte; they had gone from denigrating Old Nick to wild enthusiasm. Memories of Bonaparte swarmed there; his bust adorned every mantelpiece; prints of him glowed in every picture-seller’s window; the colossal statue of him by Canova decorated the Duke of Wellington’s staircase. Could not another sanctuary have been dedicated to Mars enchained? That deification seems rather the representation of a caretaker’s vanity than a warrior’s honour. – General you did not vanquish Napoleon at Waterloo, you merely broke the last link of a destiny already shattered.

Book XXVII: Chapter 4: More despatches

BkXXVII:Chap4:Sec1

After my official presentation to George IV, I saw him several times. The recognition of the Spanish colonies by England was shortly resolved; at least it seemed that the ships of those independent States were to be welcomed in the harbours of the British Empire under their own flag. My despatch of the 7th of May gave an account of a conversation I had with Lord Londonderry, and of that Minister’s thoughts. This despatch, important then in the order of things, would be almost without interest to today’s reader. Two things were to be distinguished as regards the Spanish colonies relative to England and France: commercial interests and political interests. I entered into the details of those interests. ‘The more I see of the Marquis of Londonderry,’ I said to Monsieur de Montmorency ‘the more subtle I find him. He is a man full of resource, who only ever says what he wishes to; one would sometimes be tempted to think him good-natured. He has the laughter in his voice, the look, something, of Monsieur Pozzo di Borgo. He does not exactly inspire trust.’

The despatch ends thus: ‘If Europe is forced to recognise the de facto governments of America, all her politics should tend towards the generation of monarchies in the New World, instead of revolutionary republics which export their principles to us with the products of their soil.

Reading this despatch, Monsieur le Vicomte, you will doubtless experience, as I do, a feeling of satisfaction. A significant political step has already been achieved in having obliged England to desire our involvement in matters regarding which she would not have deigned to consult us six months ago. I congratulate myself as a good Frenchman on all which tends to re-establish our country in the high position which it ought to occupy among other nations.’

This letter was the foundation for all my ideas and negotiations regarding colonial affairs with which I occupied myself during the War in Spain, almost a year before that war was actually declared.

Book XXVII: Chapter 5: The resumption of Parliamentary activity – A ball given on behalf of the Irish – A duel between the Duke of Bedford and the Duke of Buckingham – Dinner at Royal Lodge – The Marchioness of Conyngham and her secret

BkXXVII:Chap5:Sec1

On the 17th of May I was at Covent Garden, in the Duke of York’s box. The King appeared. That prince, once detested, was welcomed with acclamation such as he would never have received from the monks who once inhabited that ancient monastery. On the 26th, the Duke of York came to dine at the Embassy: George IV was tempted to do me the honour also; but he feared diplomatic jealousy on the part of my colleagues.

‘His Royal Highness, The Duke of York’

A Circumstantial Report of the Evidence and Proceedings Upon the Charges Preferred Against His Royal Highness The Duke Of York... - Frederick Augustus, Duke of York and Albany et al. (p472, 1809)

Internet Archive Book Images

The Vicomte de Montmorency refused to enter into negotiations over the Spanish colonies with the Court of St James. I learnt, on the 19th of May, of the sudden death of Monsieur le Duc de Richelieu. That honest man had patiently endured his first dismissal from government; but events causing him to lose too much time he missed any further opportunity, since he lacked a second life to replace that which he had lost. The great name of Richelieu has only been transmitted to us via the female line.

Revolution continued in the Americas. I wrote to Monsieur de Montmorency:

‘No. 26. London, 28th May 1822.

Peru has just adopted a monarchical constitution. European politics must exert all its energies on achieving a like result in the colonies which have declared their independence. The United States specifically fears the establishment of an empire in Mexico. If the New World remains republican as a whole, the monarchies of the Old World will die out.’

There was much talk of distress among the Irish peasantry, and peopled danced for consolation. A grand ball held at the Opera, engaged all feeling souls. The King, encountering me in the corridor, asked me what I was doing there, and taking me by the arm, led me to his box.

The stalls, in the days when I was an exile, were rough and rowdy; sailors drank beer there, ate oranges, and shouted at the boxes. I once found myself next to a sailor who had arrived in a state of intoxication; he demanded to know where he was; I told him: ‘Covent Garden. – A pretty garden, indeed!’ he exclaimed, seized, like the gods in Homer, with inextinguishable laughter.

Invited recently to an evening at Lord Lansdowne’s, His Lordship presented me to a severe-looking lady of sixty-six: she was dressed in crepe, wore a black veil like a tiara on her white hair, and resembled some queen who had abdicated. She greeted me in solemn tones, with three mispronounced quotations from Le Génie du Christianisme; then she told me with no less solemnity: ‘I am Mrs Siddons.’ If she had said: ‘I am Lady Macbeth’, I would have believed her. I had seen her previously on the stage at the height of her powers. It was necessary only to have lived long enough to find the debris of one century hurled onto the shore of another by Time’s waves.

The visitors from France I received in London were Monsieur le Duc and Madame la Duchesse de Guiche, whom I will speak about in talking of Prague; Monsieur le Marquis de Custine, whom I had known when he was a child at Fervaques; and Madame la Vicomtesse de Noailles, as pleasant, spiritual and gracious as if she were still fourteen and wandering through the lovely gardens at Méréville.

People tired of receptions; the Ambassadors dreamed of going on leave: Prince Esterhazy prepared to depart for Vienna; he hoped to be summoned to the Congress, since they were already talking of a Congress. Monsieur Rothschild returned to France, he and his brother having arranged the Russian loan of 23 million roubles. The Duke of Bedford fought with the high-spending Duke of Buckingham, at the bottom of a hollow, in Kensington Gardens; a song injurious to the King of France, brought from Paris and printed in the London papers, amused the radical English scoundrels who laugh without knowing at what.

I left on the 6th of June for Royal Lodge, where the King was. He had invited me to dinner, and to stay the night.

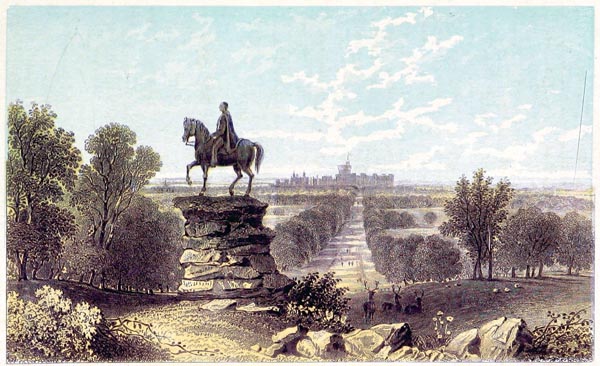

‘Long Walk and Statue of George III, Windsor Castle’

The Royal Windsor Guide, with a Brief Account of Eton (p89, 1868)

The British Library

I saw George IV again on the 12th, 13th and 14th, at a levee, at a drawing-room reception, and at a ball given by his Majesty. On the 24th, I gave a dinner for the Prince and Princess of Denmark; the Duke of York was invited.

The kindness, with which the Marchioness of Conyngham treated me, might have been a thing of importance once: she told me that His Majesty’s idea of a trip to the continent had not been entirely abandoned. I hid this great secret religiously in my breast. What important despatches might have been written about this word from a favourite, in the age of Mesdames de Verneuil, de Maintenon, Des Ursins and de Pompadour! Besides, it would have been inappropriate for me to stir myself to obtain information from the Court of St James: you speak in vain, no one hears.

Book XXVII: Chapter 6: Portraits of the Ministers

BkXXVII:Chap6:Sec1

Lord Londonderry was particularly impenetrable: he hindered one by his sincerity as a Minister and at the same time his reserve as a man. He explained his political views frankly in a most frigid manner and kept a profound silence where events were concerned. He seemed as indifferent about what he said as about what he did not; one did not know what to think of what he revealed or of what he hid. He would not have budged if you had exploded a firecracker in his ear, as Saint-Simon has it.

Lord Londonderry possessed a kind of Irish eloquence which often caused hilarity in the Lords, and gaiety amongst the public: his blunders were celebrated, but he sometimes attained marks of eloquence which swayed a crowd, for example his speeches regarding the battle of Waterloo: I reminded him of them.

The Earl of Harrowby was Lord President of the Council; he spoke with propriety, lucidity and knowledge of the facts. It would have been considered unseemly in London if the President had expressed himself with prolixity and loquacity. Otherwise he was a perfect gentleman in manner. One day, in the Paquis, at Geneva, an Englishman was announced: Lord Harrowby entered; I barely recognised him: he had lost his former king; mine was in exile. It was the last time the England of my period of grandeur appeared before me.

I have mentioned Mr Peel and Lord Westmoreland in The Congress of Verona.

I do not know if Lord Bathurst is descended from and is the grandson of the Lord Bathurst of whom Sterne wrote: ‘This nobleman, I say, is a prodigy! For at eighty five he has all the wit and promptness of a man of thirty, a disposition to be pleased, and a power to please others, beyond what-ever I knew.’ Lord Bathurst, the Minister of whom I am speaking, was educated and polite; he kept up the traditions of old French manners and good company. He had three or four daughters who ran, or rather flew like sea terns, beside the waves, slender, white, and weightless. What has become of them? Have they fallen into the Tiber like the young Englishwoman of that name?

Lord Liverpool was not, like Lord Londonderry, the leading Minister; but he was the Minister who was most influential and most respected. He enjoyed reputation as a religious man and one of good will, a thing so potent for those who possess it; the man was approached with the trust one bestows on one’s father; no action appeared good if it was not approved by this saintly person, invested with an authority greatly superior to that of mere talent. Lord Liverpool was the son of Charles Jenkinson, Earl of Liverpool, Baron Hawkesbury, favourite of Lord Bute. Almost all the English Statesmen first pursued a literary career, in pieces of verse of varying quality, and in articles, generally excellent, inserted in the reviews. There is a portrait of this 1st Earl of Liverpool when he was private secretary to Lord Bute; his family was in great distress: vanity, puerile at all times, is doubtless still more so today; but let us not forget that our most fiery revolutionaries acquired their hatred of society from natural disadvantage or social inferiority.

‘Robert Bankes, Lord Hawkesbury, Afterwards 2nd Earl of Liverpool’

Catalogue of Portraits, Miniatures etc. in the Possession of Cecil George Savile, 4th Earl of Liverpool, Lord Steward - Cecil George Savile (p146, 1905)

Internet Archive Book Images

It is possible that Lord Liverpool, inclined to reform, and to whom Mr Canning owed his last Ministry, was influenced, despite the strictness of his religious principles, by unpleasant memories. At the time when I knew Lord Liverpool, he was an inspired Puritan almost. He lived alone, though habit, with an elderly sister, some miles from London. He spoke little; his expression was gloomy; he often cupped his ear with the air of listening to something sad: one would have said he was listening to his last years falling, like drops of winter rain on the paving stones. For the rest, he had few passions, and lived according to God’s law.

Mr Croker, Secretary of the Admiralty, celebrated as an author and orator, belonged to the school of Mr Pitt, as did Mr Canning; but he was more disillusioned than the latter. He occupied one of those gloomy apartments in Whitehall, from a window of which Charles I emerged to walk to his scaffold erected on the same level. One is astonished on entering London at the buildings where the Directors of organisations sit whose power is felt at the ends of the earth. A handful of men in black frock coats at a bare table: that is all you will find: yet these are the directors of English shipping, or the members of that company of merchants, successors to the Mogul emperors, who claim two hundred million subjects in India.

Two years ago, Mr Croker came to visit me at the Marie-Thérèse Infirmary. He remarked on the similarity of our opinions and fates. Events separated us from society; politics creates it solitaries as religion creates its anchorites. When man inhabits the desert, he finds there some distant image of the infinite being who, living alone in the immensity, watches worlds complete their revolutions.

Book XXVII: Chapter 7: More of my despatches

BkXXVII:Chap7:Sec1

During the course of June and July, affairs in Spain began to seriously concern the Cabinet in London. Lord Londonderry and the majority of his Ambassadors when speaking of these matters displayed anxiety and an almost laughable dread. The government feared that in the event of a rupture we would need to defeat the Spanish; the Ministers of other powers trembled lest we be defeated; they always envisaged our army adopting the tricolour cockade.

In my despatch of 28th June, no. 35, the English position is faithfully reflected:

No. 35‘London, the 28th June 1822.

Monsieur le Vicomte,

It is easier to tell you what Lord Londonderry thinks, regarding Spain, than it would be to penetrate the secret instructions given to Sir William A’Court; however I will neglect nothing in my attempts to procure the information you requested in your last despatch, no. 18. If I have judged the political position of the English Cabinet and the character of Lord Londonderry correctly, I am convinced that Sir William A’Court is carrying almost nothing in writing. He will have been recommended, verbally, to observe the parties without getting involved in their quarrels. The Cabinet of St James does not like the Cortès, but it despises Ferdinand. It will do nothing for the Royalists: that is certain. Moreover, it suffices that our influence is exercised in favour of opinions where English influence supports opposite opinions. Our reviving prosperity is inspiring lively envy. Among the Statesmen here, there is certainly a vague fear of the revolutionary passions that are traversing Spain; but this fear is silent in the face of private interests: of such a kind that if on the one side Great Britain could exclude our goods from the Peninsula, and on the other she could recognise the independence of the Spanish colonies, she would readily involve herself in events, and console herself concerning the problems which would newly overwhelm the continental monarchies. The same principle which prevents England withdrawing her Ambassador from Constantinople causes her to send an Ambassador to Madrid: she holds back from the common fate, and only concerns herself with the part she might play in the revolutions of empires.

I have the honour, etc.’

Returning, in my despatch of the 16th July, no. 40, to the news from Spain, I said to Monsieur Montmorency:

No. 40‘London, the 16th of July 1822.

Monsieur le Vicomte,

The English newspapers, following the French newspapers, this morning carried the news from Madrid, up to the 18th inclusive. I had expected no better of the King of Spain, and was not surprised. If that wretched Prince must perish, the nature of the catastrophe is not a matter of indifference to the rest of the world; a dagger would only cut down the monarch, a scaffold might end the monarchy. It already smacks far too much of the judgement meted out to Charles I and Louis XVI; Heaven preserve us from a third judgement whereby such crimes might seem to establish by their authority popular validity, and a body of law hostile to kings! We can now wait on everything: a declaration of war on the part of the Spanish government is among the eventualities that the French government must have foreseen. In any case, we will soon be obliged to end the ‘cordon sanitaire’, since, once September is past, if the plague does not reappear in Barcelona, it would be truly derisory to speak of a cordon sanitaire; it would then be necessary to declare it frankly to be an army, and spell out the reasons which oblige us to maintain that army’s presence. Would that not be equivalent to declaring war on the Cortès? On the other hand, how could we dissolve the cordon sanitaire? That act of weakness would compromise French security, debase government, and revive among us the hopes of the revolutionary faction.

I have the honour to be, etc, etc, etc.’

‘Fernando VII’

Historia de la Villa y Corte de Madrid - José Amador de los Ríos, Juan de Dios de la Rada y Delgado, Cayetano Rosell (p456, 1860)

Internet Archive Book Images

Book XXVII: Chapter 8: Discussion about the Congress of Verona – A letter to Monsieur Montmorency; his reply which allows me to sense a refusal – Monsieur Villèle’s letter is more favourable – I write to Madame de Duras – A note from Monsieur de Villèle to Madame de Duras

BkXXVII:Chap8:Sec1

Since the Congresses of Vienna and Aix-la-Chapelle, the Princes of Europe were obsessed with congresses: it was there that one amused oneself and divided things up between the nations. Scarcely had the Congress, begun at Troppau and continued at Laibach, ended, than they thought of convoking another in Vienna, Ferrara, or Verona: the affairs of Spain offered an opportunity to expedite the event. Each country had already designated its Ambassador.

In London I witnessed everyone preparing to leave for Verona: as my head was full of the events in Spain, and as I dreamed of a project to bring France honour, I thought I might be of some use at the new Congress by making myself known in a connection which had not been considered. I had written to Monsieur de Montmorency on the 24th of May; but did not find favour. The Minister’s lengthy reply was evasive, embarrassed, and tortuous; a marked distancing of himself seemed to me to be ill concealed beneath the benevolence; he finished with this paragraph:

‘Since I am writing confidentially, dear Vicomte, I will tell you what I would not say in an official despatch, but what personal observation, and the advice too of those who well know the terrain in which you are placed, have prompted. Have you considered firstly that, vis-à-vis the English Minister, one must be cautious of certain effects of jealousy and mood that are always likely to be engendered regarding any direct marks of favour from the King, or of credit in society? Tell me, have you not chanced to notice traces of such?’

Through whom had complaints concerning my credit with the King and in society (that is to say, I assume, with the Marchioness Conyngham) been transmitted to the Vicomte de Montmorency? I do not know.

Anticipating, by this private despatch, that my cause was lost with the Foreign Minister, I addressed myself to Monsieur de Villèle, then my friend, and who was not greatly inclined towards his colleague. In his letter of the 5th of May 1822, he at first replied favourably to me.

‘Paris, the 5th of May, 1822.

I must thank you,’ he says, ‘for all you have achieved on our behalf in London; the decisions of that Court regarding the Spanish colonies should not influence our own; our position is quite different; we must avoid above all being prevented, by a war with Spain, from acting as we ought to elsewhere, should affairs in the Orient lead to new political alignments in Europe.

We will not allow the French government to be dishonoured by failing to participate in events which may arise from the current world situation: others may intervene to greater advantage, none with greater courage and loyalty.

Others are greatly mistaken, I believe, concerning both our country’s true means, and the power that the King’s government can still exercise through prescribed forms; these command more resources than they appear to think, and I trust that we will know how to reveal them on occasion.

You will support us, my dear friend, during these major events if they occur. We know it, and count on it; the honour will be yours, and not merely according to your share in the matters currently in question, but according to services rendered; let us vie with all zeal as to who will distinguish themselves most.

I do not know in truth if all this will turn into a Congress; but, in any case, I will not forget what you have said to me.

JH. DE VILLÈLE.’

At this first sign of good intent, I put pressure on the Minister of Finance through Madame la Duchesse de Duras; she had already leant me the support of her friendship regarding the Court’s neglect in 1814. She soon received this note from Monsieur de Villèle:

‘All we could say has been said; all that it is in my heart and my judgement to do for the public good, and for my friend, has been done and will be done: be certain of it. I have no need of being preached at, nor converted, I repeat; I act from conviction and sentiment.

Accept, Madame, the homage of my affectionate respect.’

Book XXVII: Chapter 9: The death of Lord Londonderry

BkXXVII:Chap9:Sec1

My final despatch, dated the 9th of August, announced to Monsieur de Montmorency that Lord Londonderry was leaving for Vienna, between the 15th and the 20th. A sudden momentous curtailment of mortal plans was revealed to me; I thought I would only have to communicate news of human affairs to the Very Christian King’s council, and I had to give an account of the affairs of God:

‘London, 12th of August 1822: 4 o’clock in the afternoon.

Despatch transmitted to Paris via the Calais telegraph-station.

The Marquis of Londonderry died suddenly at nine this morning, in his country house at North-Cray.’

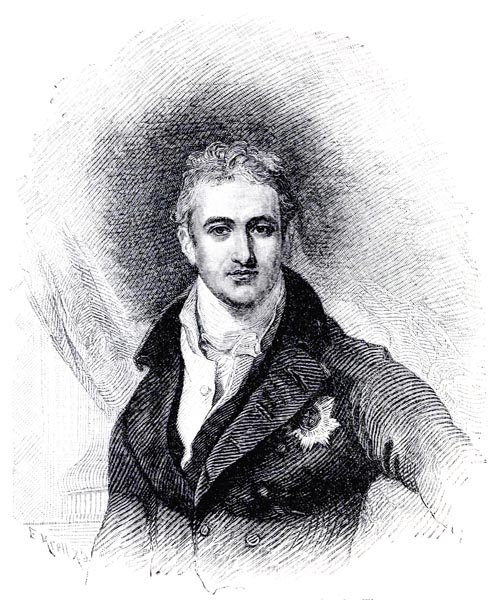

‘Castlereagh. From an engraving by Thompson’

A History of all Nations From the Earliest Times; Being a Universal Historical Library - John Henry Wright (p65, 1905)

Internet Archive Book Images

No. 49. ‘London, the 13th of August 1822.

Monsieur le Vicomte,

If the weather caused no delay to my telegraphed despatch, and if no accident occurred to my special courier, who left here at four, I anticipate that you will have received the first news on the Continent of Lord Londonderry’s sudden death.

His death is tragic in the extreme. The noble Marquis was in London on Friday; he had a minor headache; he had himself bled between his shoulder-blades. After which he left for North-Cray, where the Marchioness of Londonderry had been staying for the past month. Fever declared itself on Saturday the 10th and Sunday the 11th; but it seemed to recede between Sunday night and Monday morning, and on the Monday morning, the 12th, the illness appeared so improved, that his wife who was looking after him, thought she might leave him for a moment. Lord Londonderry, whose mind was disturbed, finding himself alone, rose, went into his office, seized a razor, and slit his jugular at the first stroke. He fell, bathed in blood, at the feet of the doctor who came to his aid.

This deplorable incident has been concealed as much as possible, but it has reached the public in garbled form, and given birth to all kinds of rumours.

Why should Lord Londonderry cut short his life? He had neither passions nor misfortunes; he was more secure in his position than ever. He was preparing to leave the following Thursday. He would have turned what is a business journey into a pleasant excursion. He was due to return on the 15th of October for a shooting trip arranged in advance, to which he had invited me. Providence has decreed otherwise, and Lord Londonderry has followed the Duc de Richelieu.’

Here are a few details which did not appear in my despatches.

On returning to London, George IV told me that Lord Londonderry had brought him the plan of instruction which he had drawn up for himself and which he would follow at the Congress. George IV took the manuscript, to consider its terms more closely, and began to read in a loud voice. He noticed that Lord Londonderry was not listening, and that his gaze was directed towards the ceiling of the room: “What is the matter, Milord? the King asked. – Sire,” replied the Marquis, “here is that insupportable John (a jockey) at the door; he won’t go away, though I am always ordering him to do so.” The King, astonished, folded the document and said: “You are ill, Milord: go home; have yourself bled.” Lord Londonderry left and went off to buy the knife with which he cut his throat.

On the 13th of August, I continued my despatch to Monsieur de Montmorency.

‘They have sent couriers everywhere, to the spas, to the coastal resorts, to the country houses, to seek the absent Ministers. At the moment when the incident occurred none of them were in London. They are expected today or tomorrow; they will hold a council meeting, but will be unable to decide anything, since, in the final result, it is the King who will nominate one of them, and the King is in Edinburgh. It is probable that His Majesty will not hasten to make a choice during the holiday season. Lord Londonderry’s death is a disaster for England: he was not loved, but he was feared; the Radicals detested him, but they were afraid of him. Singularly brave, he impressed the Opposition who dared not insult him too much at the despatch box or in the newspapers. His imperturbable sang-froid, his profound indifference to men and things, his despotic instinct and secret contempt for constitutional freedoms, made him a Minister fitted to struggle with success against the tendencies of the century. His faults appeared qualities in an age when extremism and democracy threaten society.

I have the honour, etc.’

‘London, the 15th of August 1822.

Monsieur le Vicomte,

Subsequent information has confirmed what I had the honour to tell you regarding the death of the Marquis of Londonderry, in my regular despatch, no. 49, of the day before yesterday. Only, the fatal instrument with which the unfortunate Minister cut his jugular vein was a pen-knife and not a razor as I advised you previously. The Coroner’s report, which you will see in the newspapers, will tell you all. An inquest into the death of Great-Britain’s leading Minister, as over the body of a murderer, adds something even more dreadful to that event.

You doubtless now know Monsieur le Vicomte that Lord Londonderry had shown signs of mental alienation a few days before his suicide, and that the King himself perceived them. A small circumstance to which I paid no attention, but which I have recalled since the tragedy, is worth relating. I went to see the Marquis of Londonderry, a fortnight or so ago. Contrary to his custom, and to that of the country, he received me familiarly in his dressing-room. He was about to shave himself, and while laughing with a sardonic laugh he made me a eulogy on English razors. I complimented him on the impending closure of the Parliamentary session. “Yes,” he said, “It will have to end or I will.”

I have the honour, etc.’

All that the English Radicals and the French Liberals have said of the death of Lord Londonderry, namely: that he killed himself because of political depression, feeling that the principles opposed to his own would triumph, is a pure fable invented by the imagination of some, the party bias and foolishness of others. Lord Londonderry was not the man to repent of having sinned against humanity, for which he scarcely cared, nor the intellectuals of the period, for whom he had a profound contempt: his insanity was introduced into the Castlereagh family through the female line.

It was decided that the Duke of Wellington, accompanied by Lord Clanwilliam, would take Lord Londonderry’s place at the Congress. The official instructions were reduced to these: forget about Italy completely: don’t get involved with affairs in Spain: negotiate regarding those of the Orient, towards maintaining the peace without adding to Russia’s influence. Luck as always was with Mr Canning, and the Foreign Affairs portfolio was only entrusted to Lord Bathurst, Minister for the Colonies, for the interim.

I was present at Lord Londonderry’s funeral, at Westminster, on the 29th of August. The Duke of Wellington seemed moved; Lord Liverpool was obliged to cover his face with his hat to hide his tears. Outside cries of insult could be heard, and of delight when the body entered the Abbey: were Colbert and Louis XIV any more respected? The living can teach the dead nothing; the dead, on the contrary, instruct the living.

‘Westminster Abbey’

Illustrated London, or, a Series of Views in the British Metropolis and its Vicinity - Albert Henry Payne (p76, 1846)

The British Library

Book XXVII: Chapter 10: A new letter from Monsieur de Montmorency – A trip to Hartwell – A note from Monsieur de Villèle announcing my nomination to the Congress

BkXXVII:Chap10:Sec1

A Letter from Monsieur de Montmorency

‘Paris, 17th of August.

Though there are no despatches of any importance to entrust to your faithful Hyacinthe, I desire however to send him on to you, noble Vicomte, according to your own wish, and the one which he has expressed to me on behalf of Madame de Chateaubriand, that of seeing him returned promptly to you. I will take advantage of it to address a few highly confidential words to you on the profound impression made here, as in London, by the news of the dreadful death of the Marquis of Londonderry, and also, at the same time, on that matter in which you seem rightly to take an exaggerated and exclusive interest. The King’s council has profited from it, and fixed for today, immediately after the closure of the session which took place this very morning, a discussion of the principal direction to be decided upon, the instructions to be given, and likewise the representatives to be selected: the first question is to decide whether there shall be one or many. You have expressed, it seems to me, a fraction of the astonishment felt that they could think of sending ..., by not preferring you to him, you know very well that he could not do the same job for us. If after mature consideration, we do not believe it possible to profit from the goodwill you have shown us with great frankness, in this regard, it would without doubt be for serious reasons which I would communicate to you equally frankly: the adjournment is rather favourable to your wishes, in this sense, that it would be totally inappropriate, for you and for us, for you to leave London in the next few weeks, before the ministerial decision is made, one which does not fail to occupy the whole Cabinet. It strikes everyone in the same way, as friends told me the other day: “If Monsieur de Chateaubriand were to come straight to Paris, it would be very annoying for him to be obliged to return to London.” So we await that important nomination, on their King’s return from Edinburgh. Sir Charles Stuart said yesterday that the Duke of Wellington would certainly go to the Congress; Monsieur Hyde de Neuville arrived yesterday in good health. I was delighted to see him. I renew all my inviolable sentiments towards you, noble Vicomte,

MONTMORENCY.’

This fresh letter from Monsieur de Montmorency, containing ironic phrases, plainly confirmed to me that he did not wish me to attend the Congress.

I gave a dinner on Saint-Louis’ day in honour of Louis XVIII, and paid a visit to Hartwell in memory of that King’s exile; I fulfilled a duty rather than enjoying a pleasure. Unfortunate Royals are now so common that one is scarcely interested in places except those where genius or virtue lived. In the little park at Hartwell I only saw Louis XVI’s daughter.

Finally and suddenly I received this unexpected note from Monsieur de Villèle which gave the lie to my presentiments and put an end to my uncertainty:

‘27th of August 1822.

My dear Chateaubriand, it has been decided that as soon as the proprieties regarding the King’s return to London allow, you will be authorised to return to Paris, in order to travel from there to Vienna or Verona as one of the three plenipotentiaries charged with representing France at the Congress. The two others will be Messieurs de Caraman and de La Ferronays; which does not prevent Monsieur le Vicomte de Montmorency leaving for Vienna the day after tomorrow, in order to assist at the discussions which may take place there before the Congress. He is to return to Paris when the sovereigns depart for Verona.

This is for your eyes alone. I am happy that the matter has taken the direction you desire; my heart is all yours.’

After this note, I prepared to leave.

Book XXVII: Chapter 11: The end of the old England – Charlotte Reflections – I leave London

BkXXVII:Chap11:Sec1

The lightning which dogs my footsteps follows me everywhere. With Lord Londonderry the old England, which up till then had struggled amidst a whirlpool of innovation, expired. Mr Canning rose: pride led him to speak at the rostrum in the language of the propagandist. After him the Duke of Wellington appeared, a conservative who came to destroy: when the judgement of nations is pronounced, it will be seen that the hand which ought to have lifted up, only knew how to drag down. Lord Grey, O’Connell, all the specialists in ruination, worked successively at the demise of the old institutions. Parliamentary Reform, the Emancipation of Ireland, things which were excellent in themselves, became, through the un-healthiness of the times, causes of destruction. Fear increases evils; if one is not strongly affected by threats, one can resist them with a modicum of success.

What need had England to indulge in our recent disturbances? Immured in its island, nurturing its national enmities, it remained protected. What need had the Court of St James to dread Irish Separation? Ireland was merely England’s dinghy: cut the painter, and the dinghy, separated from the mother vessel, would founder amongst the waves. Lord Liverpool himself had sad presentiments. I dined with him one day: after dinner we chatted by a window looking out over the Thames; downstream one could see a section of the city looming through the smoke and fog. I praised, to my host, the solidity of the English monarchy, maintaining as it did the balance between freedom and power. The venerable Lord, raising and extending his arm, pointed towards the city, saying: ‘Where is the solidity in vast cities like these? One serious insurrection, in London, and all will be lost.’

It seems to me that I chart a course through England, similar to that which I once made through the ruins of Athens, Jerusalem, Memphis and Carthage. Summoning up the centuries of Albion, passing from famous person to famous person, watching them vanish one by one, I experience a sort of mournful vertigo. Where are those brilliant and tumultuous times in which Shakespeare and Milton, Henry VIII and Elizabeth, Cromwell and William III, Pitt and Burke lived? All that is over; superiority and mediocrity, love and hatred, happiness and misery, oppressors and oppressed, executioners and victims, kings and people, all rest in the same silence and the same dust. What nothingness is ours then, if the most vibrant portion of the human species inhabits it, genius which casts a shadow of former times into the present generations, but no longer has life itself, and is disregarded as if it had never been?

How many times has England been invaded over the course of the centuries! How many revolutions has she passed through to arrive at the brink of the greatest, most profound of revolutions, one which will encompass posterity! I have been witness to those notable British Parliaments in all their power: what has become of them? I saw England in her traditional prosperity, living her traditional way of life: everywhere little solitary churches with their towers, Gray’s country churchyards, everywhere narrow sandy roads, valleys filled with cattle, moorlands dotted with sheep, parks, country houses, towns: a few large woods, a few birds, the wind off the sea. These were not the fields of Andalusia where I came across old Christians and young lovers, among the voluptuous palaces of the Moors, among aloes and palm-trees.

‘Quid dignum memorare tuis, Hispania, terris

Vox human valet?’

‘What human voice, O Spain, is worthy of recalling your shores?’

This was not that Roman Campagne whose irresistible charm ceaselessly called to me; these waves, this sunlight, were not those which bathed and illuminated the promontory on which Plato taught his disciples, that Sunium where I heard the cicada asking Minerva in vain for the hearth of the priests of her temple; but ultimately, she was charming and formidable, that England, surrounded as she was by her ships, covered by her herds, and professing the religion of her great men.

Today, her valleys are obscured by the fumes from forges and factories, her roads are changed to iron tracks; and along those roads, instead of Milton and Shakespeare, restless trains travel. Already the cradles of science, Oxford and Cambridge, take on a deserted air: their colleges and gothic chapels, half-disused, trouble the sight; in their cloisters beside the tombstones of the Middle Ages, rest the forgotten marble annals of the ancient peoples of Greece; ruins guarding ruins.

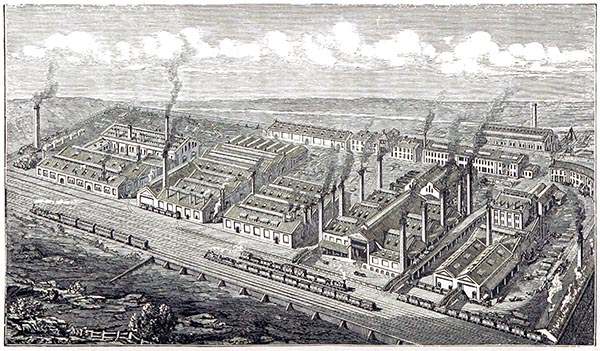

‘River Don Works - Messrs, Vickers, Sons and Co. Limited’

The Illustrated Guide to Sheffield and the Surrounding District, etc. - John Taylor (p246, 1879)

The British Library

Beside those monuments, around which a void is beginning to form, I left the rediscovered days of my springtime; I separated from my youth for a second time, on the same shore where I had abandoned it once before: Charlotte had suddenly reappeared like that light, the joy of the darkness, which, retarded in its monthly course, will rise at midnight. If you are not too weary, go and seek in Book X of these Memoirs the effect that the sudden sight of that woman had on me in 1822. When she knew me previously, I had not then met those other Englishwomen a crowd of whom surrounded me in my days of power and fame: their homage brought a kind of mildness to my fate. Now, when sixteen long years have vanished since my London embassy, and when so much else has been destroyed, my gaze returns towards that daughter of the land of Desdemona and Juliet: she is no less important to my thoughts than that day when her unexpected presence relit the torch of my memories. A new Epimenides, waking after a long sleep, I fix my eyes on a beacon, ever more radiant now that the others along the shore are extinguished; except for one that will shine long after me.

I have not related all that concerns Charlotte in the preceding books of my Memoirs: she came with some of her family to see me in France, when I was Minister there in 1823. By one of those inexplicable human misfortunes, preoccupied as I was with a war on which the fate of the French monarchy depended, something was doubtless lacking in my response, since Charlotte, on returning to England, sent me a letter in which she appeared wounded by the coldness of my reception of her. I dared neither write to her nor return the literary fragments she had sent me, which I had promised to add to, and forward to her. If it were true that she had real cause for complaint, I would throw what I have written of my first journey abroad into the fire.

It has often occurred to me to seek clarification of my doubts; but how can I return to England, I who am too weak even to dare visit the native rock where I have marked out my tomb? I am afraid of sensation now: time, in stealing my youth, has left me like those soldiers whose limbs remain on the field of battle; my blood, having a smaller path in which to circulate, reaches my heart with so rapid a flow that this old organ of my joys and sorrows beats as though ready to burst. The desire to burn what appertains to Charlotte, even though she may have been treated there with religious respect, mingles in me with the wish to destroy these Memoirs: if they still belonged to me, or if I could buy them back, I might succumb to the temptation. I have such a disgust with everything, such a contempt for the present and the immediate future, so firm a persuasion that men from now on, taken together as ‘the public’ (and for several centuries ahead), will be pitiful, that I blush to employ my last moments in telling of things past, in depicting a lost world whose language and name are no longer known.

Man is as much deceived by the success of his wishes as by their disappointment: I had desired, contrary to my natural instincts, to go to the congress of Verona; profiting from one of Monsieur de Villèle’s prejudices, I had led him to force Monsieur de Montmorency’s hand. Well, my real inclination was for other than what I had obtained; doubtless I would have been annoyed if they had made me stay in England; but soon the idea of going to see Lady Sutton, of making a tour of the three kingdoms, would have overcome that false wave of ambition, something not fundamental to my nature. God ordered things otherwise and I left for Verona: hence the change in my life, my Ministry, the Spanish War, my triumph, and my fall, soon followed by that of the monarchy.

One of the two fine children in whom Charlotte had begged me to interest myself in 1822 has just been to visit me in Paris; today he is Captain Sutton; he is married to a charming young lady, and tells me that his mother, who is very ill, has recently spent the winter in London.

I embarked at Dover on the 8th of September 1822, the same port from which, twenty-two years earlier, Monsieur Lassagne, of Neuchâtel, had set sail. Between that first departure and this moment when I have again taken up my pen, thirty nine years have elapsed. When a man reads or listens to an account of his past life, he seems to be viewing on a deserted sea the wake of a vanished vessel; he seems to hear the tolling of a bell whose ancient tower is lost to sight.

End of Book XXVII