François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book X: Exile in England 1793-1797

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book X: Chapter 1: The Ardennes

- Book X: Chapter 2: The Prince de Ligne’s wagons – The women of Namur – I find my brother again in Brussels – Our last farewell

- Book X: Chapter 3: Ostend – The crossing to Jersey – I am landed on Guernsey – The pilot’s wife – Jersey – My uncle De Bedée and his family – A description of the island – The Duc de Berry – Friends and relatives lost – The misfortune of growing old – I cross to England – My last meeting with Gesril

- Book X: Chapter 4: The Literary Fund – An attic in Holborn – The worsening of my health – A visit to the doctors – Émigrés in London

- Book X: Chapter 5: Peltier – Literary effort – My friendship with Hingant – Our walks – A night in Westminster Cathedral

- Book X: Chapter 6: Distress – Unforeseen help – A lodging over a cemetery – New friends in misfortune – Our pleasures – My cousin La Bouëtardais

- Book X: Chapter 7: A sumptuous reception – The end of my forty crowns – Fresh misery - Table d’hôte – Bishops – Dining at the London Tavern – Camden’s manuscripts

- Book X: Chapter 8: My provincial occupations – My brother’s death – Family misfortunes – Two Frances – Hingant’s letters

- Book X: Chapter 9: Charlotte

- Book X: Chapter 10: Return to London

- Book X: Chapter 11: An astonishing encounter

Book X: Chapter 1: The Ardennes

London, April to September 1822. (Revised February 1845)

BkX:Chap1:Sec1

Leaving Arlon, a farmer’s cart picked me up, and for the sum of four sous deposited me twelve miles off on a pile of stones. Having hopped a few feet with the aid of my crutch, I washed the bandages of my scratch, which had become a wound, in a spring which flowed beside the roadway, which served me very well. The smallpox fever had completely gone, and I felt relieved. I had not abandoned my knapsack though its straps cut my shoulders.

I spent the first night in a barn, with nothing to eat. The wife of the farmer who owned the barn refused payment for my bed; at daybreak she brought me a large bowl of white coffee and a cob of black bread which I found excellent. I took to the road again full of energy, though I often fell. I had been joined by four or five of my comrades who carried my rucksack; they too were quite ill. We met villagers, and riding on cart after cart, we covered enough of the road after five days to reach Attert, Flamizoul and Bellevue. On the sixth day, I found myself alone again. My smallpox swellings had whitened and subsided.

After staggering six miles, which took me six hours, I saw the camp of a gipsy family, with their two goats and a donkey, on the far side of a ditch, around a fire made from undergrowth. I had scarcely arrived before I slumped down and the singular creatures hastened to my aid. A young woman dressed in rags, lively, dark-haired, and mischievous, sang, skipped and span round and round, while holding her child slantwise to her breast, like the hurdy-gurdy which might have enlivened her dancing, then she sat on her heels, opposite me, gazing at me with curiosity in the firelight, and took my feeble hand to read my fortune, while demanding a little sou; it was too expensive. It would be difficult to possess more wisdom, kindness, or be poorer than my sibyl of the Ardennes. I am not sure when the nomads, of whom I should have made a noble son, left me: when, at daybreak, I had shaken off my dullness, I found them no longer there. My fortune-teller had gone taking with her the secret of my fate. In exchange for my petit sou, she had placed an apple beside me that served to refresh my mouth. I was shivering like Jeannot Lapin in the thyme and the dew; but I could neither nibble nor scamper, nor run madly in circles. I rose nevertheless with the intention of paying court to the dawn: she was very beautiful, and I was very ugly; her rosy cheeks proclaimed her good health; she was in better shape than her poor Armorican Cephalus. Though we were both young, we were old friends, and I imagined her tears that morning were for me.

I plunged into the forest: I was not overly saddened; solitude had brought me back to my true nature. I chanted a ballad by the unfortunate Cazotte:

‘Deep in the midst of the Ardennes,

A castle stands on a rocky height’ etc. etc.

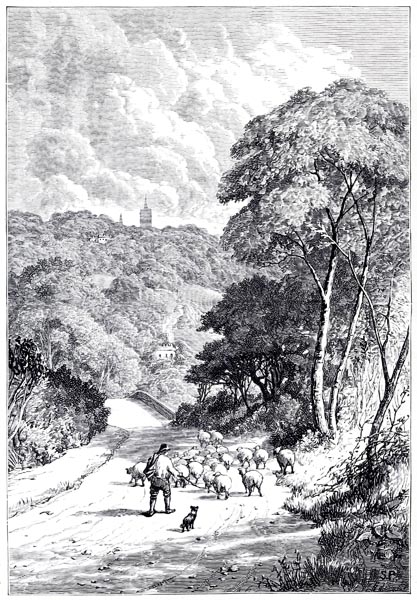

Was it not in the keep of this castle full of phantoms, that the King of Spain, Philip II, imprisoned my compatriot, the captain, La Noue, who had a Chateaubriand for a grandmother? Philip consented to the release of his illustrious prisoner, if he would consent to being blinded; La Noue was on the point of accepting this offer, such was his hunger to regain his beloved Brittany. Alas! I was possessed with the same desire, and to lose my sight it would only require the effects of the illness, with which it had pleased God to afflict me, I did not meet with Sir Enguerrand on his way from Spain, but with poor wretches, market stallholders, who, like me, carried their whole fortune on their backs. A woodcutter, with felt knee-pads, entered the wood: he might have taken me for a dead branch and lopped me. Crows, skylarks, and buntings, a species of large finch, hopped in the roadway, or perched motionless on the line of stones, alert to the hawk that glided in circles in the heavens. From time to time, I heard the sound of the swineherd’s horn as he guarded his sows and their young, feeding on acorns. I rested in a shepherd’s hut on wheels; I found no one at home other than a kitten which gave me a thousand graceful caresses. The shepherd was standing far off, in the middle of a track, his dogs stationed round the sheep at various distances; during the day, this shepherd gathered simples, he was a herbalist and a sorcerer; at night he gazed at the stars, he was a Chaldean shepherd.

I was stationed a mile or more higher, in deer-pasture: hunters traversed its boundary. A fountain welled up at my feet; in the depths of this fountain, in this same forest, Orlando, innamorato, not furioso, saw a palace of crystal full of knights and ladies. If the paladin, who met with the shining naiads, had at least left Golden-Bridle beside the spring; if Shakespeare had sent me Rosalind and the exiled Duke, it would have been a great help to me.

Having regained my breath, I continued my journey. My weakened thoughts drifted on a sea which was not without charm; my old phantoms, scarcely possessing the consistency of shadows, three-quarters effaced, surrounded me to wish me farewell. I no longer had the power of memory; I saw in the indefinite distance, mingled with unknown images, the airy forms of my relatives and friends. When I sat down against a milestone, I thought I could see faces smiling at me from the thresholds of far-off huts, in the blue smoke escaping from the roofs of thatched cottages, in the tops of the trees, in the transparent clouds, in the luminous sheaves of the sun drawing its rays over the heather like a golden rake. The apparitions were those of the Muses arriving to assist at the death of a poet: my grave, dug with the lintel of their lyres beneath an oak-tree in the Ardennes, would be as fitting for the soldier as the traveller. Only the hazel grouse, wandering where the hares shelter beneath the privet, and the insects, made a murmur around me; lives as slight, as unknown as mine. I could walk no further; I felt I was in extremities; the small-pox had returned and was suffocating me.

Towards the end of that day, I was lying on my back on the ground, in a ditch, my head supported by the knapsack containing Atala, my crutch beside me, my eyes fixed on the sun, whose gaze was fading with mine. I saluted with utter mildness of thought the star which had lighted my early youth in my native land: we were setting together, he to rise more gloriously, I, in all likelihood, never to wake again. I lapsed into unconsciousness with a religious feeling: the last sound I heard was the fall of a leaf and the whistling of a bullfinch.

Book X: Chapter 2: The Prince de Ligne’s wagons – The women of Namur – I find my brother again in Brussels – Our last farewell

London, April to September 1822.

BkX:Chap2:Sec1

It seems that I was unconscious for two hours more or less. The Prince de Ligne’s wagons happened to pass by; one of the drivers had stopped to cut a branch of silver birch, and without noticing me, stumbled over me: he thought me dead and grasped me by the leg; I gave a sign of life. The driver called to his friends, and, with merciful instinct, threw me into a cart. The jolting revived me: I was able to speak to my saviours; I told them I was a soldier in the Army of Princes, and that if they would take me to Brussels, where I was going, I would repay them for their effort. ‘Well, friend,’ one of them replied, ‘you will have to get off at Namur, since we are forbidden to carry anyone for hire. We will pick you up again on the other side of the town.’ I asked for a drink; I swallowed several gulps of brandy which brought the symptoms of my illness to the surface and relieved my chest for a while: nature had endowed me with extraordinary powers of resistance.

About ten in the morning we arrived in the suburbs of Namur. I set foot on the ground and followed the carts from a distance; I soon lost sight of them. On entering the town I was stopped. While they were examining my papers I sat in the doorway. The soldiers on guard there, on seeing my uniform, offered me a crust of army bread, and the corporal presented me with pear brandy in a blue glass pot. I made several attempts to drink from the cup of military hospitality: ‘Come on, drink it!’ he cried angrily, accompanying his injunction with a Sacrement der Teufel!

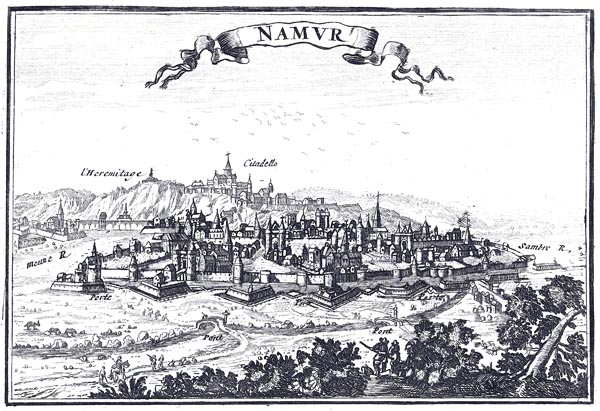

‘Namur’

Laurens Scherm, Pieter Mortier (I), 1702-1703

The Rijksmuseum

My traverse of Namur was painful: I went by, leaning against the buildings. The first woman who saw me came out of her shop, and gave me her arm with a look of compassion, and helped me drag myself along; I thanked her and she replied: ‘No, no, soldier.’ Soon other women ran up to me, bringing bread, wine, fruit, milk, broth, old clothes, and blankets. ‘He is wounded,’ some said in their Brabant-French patois; ‘He has smallpox,’ cried others, and pushed their children away. ‘But, young man, you can’t walk; you will die; stop at the hospital.’ They wanted to take me there, and relayed me from door to door, conducting me in this way to the one hospital the town possessed, outside which I found the wagons. You have seen a farmer’s wife succour me, you will see another woman, in Guernsey, take me in. Women who have helped me in my distress, if you are still alive, may God aid you in old age and sadness! If you have left this life, may your children own a share of that happiness that heaven refused me for so long!

The women of Namur helped me climb into the wagon, recommended me to the driver, and forced me to accept a woollen blanket. I noticed that they treated me with a kind of respect, or deference: there is something elevated and thoughtful in the French character that other nations recognise. The Prince de Ligne’s people set me down in the road where it entered Brussels and refused my last écu.

In Brussels, not one hotel would accept me. The Wandering Jew, the Orestes of the populace, whom the old ballad of lament placed in that town:

‘When he was in that town

Of Brussels in Brabant,’

was more welcome there than I was, since he had five sous in his pocket. I knocked, someone opened; seeing me they shouted: ‘Pass on! Pass on!’ and shut the door in my face. They drove me from the cafes. My hair hung over my face, masked by my beard and moustache; my thigh was encased in a plaster, made of clay and straw; over my ragged uniform, I wore the woollen blanket from Namur, tied round my neck like a cloak. The beggar in the Odyssey was more insolent, but not as poor as me.

At first I presented myself in vain at the hotel where I had stayed with my brother; I made a second attempt: as I was approaching the entrance, I saw the Comte de Chateaubriand descend from a carriage with the Baron de Montboissier. He was frightened by my spectre. They looked for a room for me outside the hotel, since the owner refused utterly to admit me. A wigmaker offered a hovel suited to my wretchedness. My brother brought a doctor and a surgeon to me. He had received letters from Paris; Monsieur de Malesherbes invited him to return to France. He told me of the Tenth of August, the September Massacres, and the latest political situation of which I knew nothing. He approved of my plan to cross to Jersey, and advanced me twenty-five louis. My weakened eyesight barely enabled me to make out my unfortunate brother’s features; I thought that those shadows emanated from me, when they were in reality the shadows that Eternity was casting around him: without knowing it, we were seeing each other for the last time. All of us, while we live, have only the present moment; what follows is a matter for God: there are two possibilities of never again meeting the friend we are leaving: our death or his. How many men never remount the staircase they have just descended?

Death touches us more before than after the passing of a friend: it is a part of ourselves that is detaching itself, a world of childhood memories, family intimacies, common affections and interest which dissolves. My brother preceded me from my mother’s loins; he was first to inhabit that same sacred womb from which I emerged after him; he sat before me at the paternal hearth; he waited several years to welcome me, gave me my baptismal name, and was part of my whole youth. My blood, mixed with his blood in the revolutionary tub, would have had the same flavour, like milk produced from the pastures of a single mountain. But if men have caused my elder brother’s head, my godfather’s, to fall before its time, the years have not spared mine: already my forehead is bald; I feel, these days, as if an Ugolino leant over me, who gnaws at my skull:

...come’l pan per fame si manduca (as bread is chewed, out of hunger)

Book X: Chapter 3: Ostend – The crossing to Jersey – I am landed on Guernsey – The pilot’s wife – Jersey – My uncle De Bedée and his family – A description of the island – The Duc de Berry – Friends and relatives lost – The misfortune of growing old – I cross to England – My last meeting with Gesril

London, April to September 1822.

BkX:Chap3:Sec1

The doctor could net get over his astonishment: he considered this fluctuating smallpox that failed to kill me, and did not develop to a natural crisis, as a phenomenon for which medicine offered no precedent. As for my wound, gangrene had set in: the wound was dressed with cinchona. Having obtained this first aid, I insisted in leaving for Ostend. Brussels was odious to me; I was keen to get away; it was filling once more with those heroes of domesticity, returning from Verdun in their carriages, whom I did not see, in that same Brussels, when I accompanied the King during the Hundred Days.

I reached Ostend slowly via the canals: there I found several Bretons, my companions in arms. We chartered a decked boat and sailed down the Channel. We slept in the hold, on the shingle that served as ballast. My physical strength was exhausted. I could no longer speak; the swell of a rough sea brought me to the point of collapse. I could barely swallow a few drops of lemon water, and when bad weather forced us to put into Guernsey, they thought I was about to expire; an emigrant priest read me the prayers for the dying. The captain, not wishing me to do so, on board, ordered them to set me down on the quay: they sat me in the sun, back against a wall, head turned towards the open sea, facing the island of Alderney, where eight months or so previously I had faced death in another form.

Apparently I was fated to arouse pity. The wife of an English pilot happened to be passing; she was moved, and called her husband who, aided by two or three sailors, carried me, a friend of the waves, into a fisherman’s cottage; they laid me on a comfortable bed, between the whitest sheets. The young woman took every possible care of the stranger: I owe her my life. The next day I was taken back on board. My hostess almost wept on parting from her patient; women have a heaven-sent instinct regarding misfortune. My lovely, fair-haired guardian, who resembled a figure from some old English print, pressed my swollen, burning hands between her long, cool ones: I was ashamed to bring such ugliness close to such beauty.

We set sail, and reached the westernmost point of Jersey. Monsieur de Tilleul, one of my companions, went to St Helier, to my uncle. Next day, Monsieur de Bedée came in a carriage to fetch me. We crossed the whole island: though I felt quite deathly, I was still charmed by its hedged fields: but babbled nothing but nonsense about them, having fallen into a delirium.

I lay for four months between life and death. My uncle, his wife, his son, and three daughters, took turns beside my bed. I occupied an apartment in one of the houses they had begun to build along the foreshore: my bedroom windows reached the floor, and beyond the end of my bed I could see the sea. The doctor, Monsieur Delattre, had forbidden any talk of serious matters, especially politics, with me. Towards the end of January 1793, seeing my uncle enter my room in full mourning, I trembled, thinking we had lost a member of the family: he informed me of the death of Louis XVI. I was not surprised; I had foreseen it. I asked for news of my relatives; my sisters and my wife had returned to Brittany briefly after the September Massacres; they had found considerable difficulty in leaving Paris. My brother, on his return to France, was living quietly with Monsieur Malesherbes.

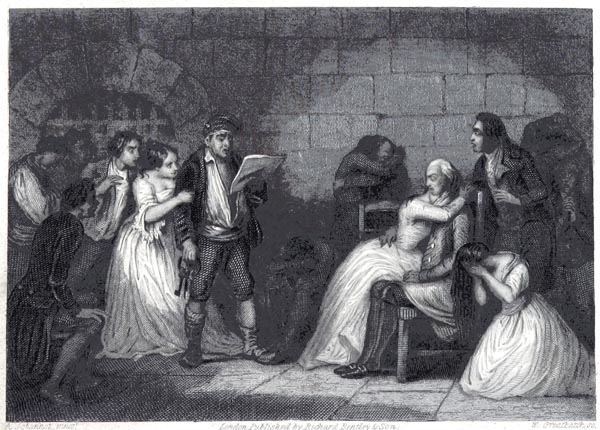

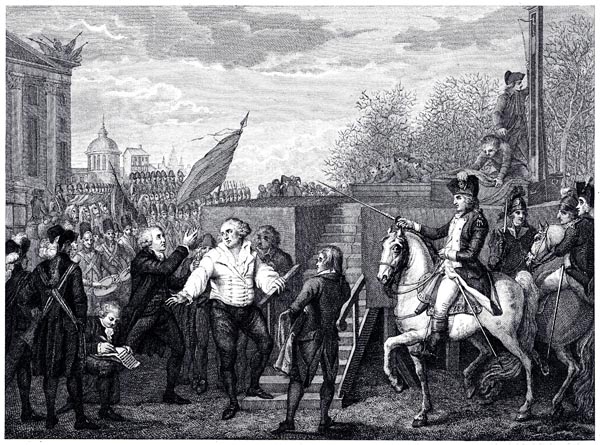

‘Summoning to Execution’

The History of the French Revolution. Translated by F. Shoberl, Vol 05 - Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p10, 1881)

The British Library

I began to leave my bed; the smallpox had vanished; but I felt pain in my chest, and a weakness remained which stayed with me for a long time.

BkX:Chap3:Sec2

Jersey, the Caesarea of the Antonine itinerary, was subject to the English crown from the death of Robert, Duke of Normandy; we have attempted to recapture it on several occasions, but always without success. The island is a relic of our ancient history. Saints, who came from Hibernia and Albion to Brittany-Armorica, broke their journey at Jersey.

St Helier, solitary, is sited among the rocks of Caesarea; the Vandals committed massacres there. On Jersey one finds a sample of ancient Normans; one might think one was hearing William the Bastard speaking, or the author of the Roman du Rou.

The island is fertile; it has two towns and twelve parishes; it is covered with country houses and herds. The ocean breeze, which seems to forego its harshness, allows Jersey to produce exquisite honey, extremely soft cream, and butter of a rich yellow colour that smells of violets. Bernardin de Saint-Pierre presumes that apple-trees came to us from Jersey; he is wrong: we obtained the apple and pear from Greece, as we owe the peach to Persia, the lemon to the Medes, the plum to Syria, the cherry to Cerasonte (Turkey), the chestnut to Castania (Pontus or Thessaly), the quince to Cydon (Crete), and the pomegranate to Cyprus.

I took great pleasure in going about during the first few days of May. Spring retains all its freshness on Jersey; one might still call it primavera as long ago, a name which while growing old, has left behind a daughter, the primrose, the first flower with which it garlands itself.

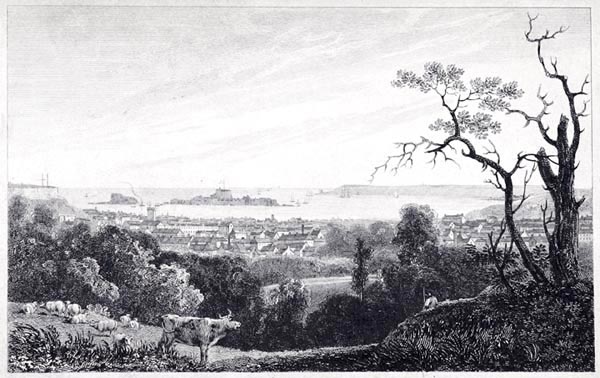

Cæsarea. The Island of Jersey - Appendix (p10, 1840)

The British Library

Here I will transcribe two pages for you from my life of the Duc de Berry, which is no less to tell you of mine:

‘After twenty-two years of struggle, the barrier of bronze which enclosed France had been forced: the hour of the Restoration neared; our Princes left their retreats. Each of them made for different points on the various frontiers, like travellers who seek, on peril of their life, to penetrate a country of which wonders are told. Monsieur headed for the Swiss, Monseigneur le Duc d’Angouleme for the Spanish, and his brother for Jersey. In that island, where several of Charles I’s judges died, ignored by the world, Monseigneur le Duc de Berry met French royalists, aged by exile, their virtues forgotten, as formerly had been the English regicides’ crime. He met old priests, now consecrated to solitude; he recognised in them the character invented by the poet who wrote of a Bourbon setting foot on Jersey, after a storm. Just such a confessor and martyr might have said to the heir of Henry IV, as the hermit of Jersey said to that great King:

‘Far then from the Court, in this obscure place,

I come to bewail the injury to my faith.’ (Henriade)

Monseigneur le Duc de Berry spent several months in Jersey; the sea, the wind, and politics kept him there. All of them ran counter to his impatient wishes; he found himself on the point of renouncing his enterprise, and embarking for Bordeaux. A letter from him to Madame la Maréchale Moreau, vividly displays his pre-occupation, on his rocky isle:

‘8th of February 1814.

Here I am then, like Tantalus, in sight of that unhappy France which has so much trouble breaking free of its chains. You whose soul is so fine, so French, reflect on all that I experience; on what it costs me to be far from those shores that it would only take me two hours to reach! When the sun illuminates them, I climb the highest cliff, and, telescope in hand, I possess the whole coastline; I see the cliffs of Coutances. My imagination is exalted, I see myself leaping to earth, surrounded by the French, with white cockades in their hats: I hear the cry of: ‘Long live the King!’ that cry which the French can never hear unmoved; the most beautiful lady of the province drapes a white scarf around me, since love and glory are always found together. We march on Cherbourg; some villainous army, with a garrison of foreigners, tries to defend it: we carry it by assault, and a vessel leaves to go and bring the King, under the white banner which recalls days of glory and happiness for France! Ah! Madame, when one is only a few hours away from a dream so achievable, how can one think of going further away?’

It is three years since I wrote these pages in Paris; My presence in Jersey, that island of exile, had preceded Monsieur le Duc de Berry’s by twenty-two years; I was obliged to leave my name there, since Armand de Chateaubriand married there and his son Frédérick was born there.

BkX:Chap3:Sec3

Gaiety had not abandoned my uncle Bedée’s family; my aunt kept a large and cherished dog descended from those whose virtues I have recounted; as he bit everyone and was mangy, my cousins secretly had him put down, despite his nobility. Madame de Bedée was persuaded that the English officers, charmed by the beauty of Azor, had stolen him, and that he lived full of honours and dinners, in the richest castle of the three kingdoms. Alas! Our present hilarity was only composed of our past gaiety. In retracing scenes from Monchoix, we found the means to generate laughter in Jersey. That is rare enough, for in the human heart, pleasures do not maintain the same relationship between themselves that sorrows preserve there: new joys do not recreate former joys, but recent sorrows revive old sorrows.

One more thing, the émigrés excited general sympathy at that time; our cause seemed the cause of the European orders: honourable adversity is something, and ours was such.

Monsieur de Bouillon was the protector of the French refugees in Jersey: he dissuaded me from my plan to cross to Brittany, unfit as I was to endure an existence in caves and forests; he advised me to head for England and look for an opportunity there of entering the regular service. My uncle, ill provided with money, began to feel uneasy given his large family; he found himself obliged to send his son to London to feed himself on poverty and hope. Fearing to be a burden on Monsieur de Bedée, I decided to relieve him of my person.

Thirty louis brought to me by a Saint-Malo smuggler, enabled me to execute my plan and I booked a berth on the Southampton packet. On saying farewell to my uncle, I was deeply moved; he had cared for me with a father’s affection; the few happy moments of my childhood were associated with him; he knew all that was dear to me; I saw a certain resemblance to my mother in his features. I had left that excellent mother behind, and I would not see her again; I had left my sister Julie and my brother, and was doomed to meet them no more; I was leaving my uncle, and his beaming countenance would never again gladden my eyes. A few months had sufficed to bring about all these losses, for the death of our friends is not to be reckoned from the moment when they die, but from that when we cease to live with them.

If one could say to Time: ‘All is fair!’ one could arrest it at the moment of delight; but since one cannot, let us not linger down here; let us depart, before we have seen our friends vanish, and those years which the poet found alone worthy of life: Vita dignior aetas. What enchants us at the age for liaisons becomes a matter of pain and regret at the age of detachment. One no longer wishes for the return of the smiling seasons; rather one fears it: the birds, the flowers, a lovely evening at the end of April, a lovely night beginning at dusk with the first nightingale, completed at dawn by the first swallow, those things which stir the need and desire for happiness, you extinguish. Other charms, you still feel them, but they are not for you: youth which tastes them at your side and which you gaze at disdainfully, renders you jealous and makes you understand the depth of your loss. The freshness and grace of Nature, in reminding you of past joys, increases the ugliness of your woes. You are no more than a blemish on Nature: you spoil the harmony and sweetness by your presence, by your words, and even by the sentiments which you dare to express. You could love, but you can no longer be an object of love. The fountain of spring has renewed its waters without giving you back your youth, and the sight of everything that is reborn, everything joyful, limits you to the painful memory of your pleasures.

The packet I embarked on was crowded with émigré families. There I made the acquaintance of Monsieur Hingant, a former colleague of my brother’s at the High Court of Brittany, a man of taste and intelligence of whom I shall have much to say. A naval officer was playing chess in the captain’s cabin; he did not recognise my face, I was so changed; but I remembered Gesril. We had not seen each other since Brest; we were destined to part at Southampton. I told him about my travels, he told me of his. This young man, born near me among the waves, embraced his first friend for the last time in the midst of those waves which would soon bear witness to his glorious death. Lamba Doria, the Genoese Admiral, having overcome the Venetian fleet, learnt that his son had been killed: Give him to the sea, said the father, in the manner of the ancient Romans, as if he had said: ‘Give him to glory.’ Gesril only left the waves into which he threw himself, voluntarily, in order to better reveal to them his glory on their shore.

I have already given, at the beginning of the sixth book of these Memoirs, the certificate of my disembarkation from Jersey at Southampton. Here then, after my journeys through the woods of America, and the army camps of Germany, I came in 1793, as a poor émigré, to the country in which, in 1822, I write all this, and to which I am now the glorious ambassador.

‘Old Water Gate and Gaol - Southampton’

Summer Tour to the Isle of Wight; including Portsmouth, Southampton, Winchester, the South Western Railway - Thomas Roscoe (p248, 1843)

The British Library

Book X: Chapter 4: The Literary Fund – An attic in Holborn – The worsening of my health – A visit to the doctors – Émigrés in London

London, April to September 1822.

BkX:Chap4:Sec1

A society exists in London to provide assistance to men of letters, English as well as foreign. This society recently invited me to its annual meeting; it was my duty to attend and pay my subscription. His Royal Highness the Duke of York occupied the president’s chair; on his right was the Duke of Somerset, and Lords Torrington and Bolton; he placed me on his left. There I met my friend Mr Canning. The poet, orator, and illustrious minister made a speech in which appeared this passage making honourable mention of me, which the newspapers repeated: ‘Though the person of my noble friend, the French Ambassador, may be little known here as yet, his character and writings are well known throughout the whole of Europe. He began his career by revealing the principles of Christianity; he has continued it by defending that of the Monarchy, and now he has arrived in this country to unite our two States through the common ties of monarchist principle and Christian virtue.’

It is many years since Mr Canning, man of letters, learnt his politics in London under Mr Pitt; almost the same number of years since I began writing, in obscurity, in this same English capital. Both of us, reaching high station, are members now of a society dedicated to helping unfortunate writers. Is it the affinity of grandeur, or the compatibility of suffering, that has united us? What are a Governor-General of India and a French Ambassador doing at a banquet of the distressed Muses? It was George Canning and François de Chateaubriand who sat there, in remembrance of their past adversity and perhaps felicity; they have drunk to the memory of Homer, reciting his verse for a morsel of bread.

‘George Canning’

England in the nineteenth century - Mary Elizabeth Latimer (p95, 1894)

The British Library

If the Literary Fund had been available to me when I arrived in London from Southampton, on the 21st of May 1793, it might perhaps have paid for the doctor’s visits to my attic in Holborn, where my cousin La Bouëtardais, son of my uncle Bedée, accommodated me. Wonders were expected from the change of air in restoring to me the necessary strength for a soldier’s life; but my health, instead of recovering, declined. My chest was the first problem; I was thin and pale, coughed frequently, and breathed painfully; I experienced sweating and spat blood. My friends, as poor as me, dragged me from doctor to doctor. These followers of Hippocrates made the crowd of beggars wait outside the door then declared, at the price of a guinea, that it was necessary for me to endure my illness patiently, adding: ‘T’is done, dear Sir.’ Doctor Goodwyn, celebrated for his experiments related to drowning and performed on his own person according to his instructions, was more generous: he assisted me with free advice; but told me, with the harshness he applied to himself, that I might last a few months, perhaps a year or two, so long as I gave up everything that tired me. ‘Don’t count on a long career’: such was the summary of his consultations.

The certainty I so gained of my imminent end, by increasing the natural mournfulness of my imagination, induced in me an incredible mental calm. That inner disposition explains a passage in the foreword at the head of my Essai Historique, and this other passage of the same Essai: ‘Attacked by an illness which leaves me with little hope, I regard all objects with a tranquil eye; the calm air of the tomb makes itself apparent to the traveller who is only a few days journey from it.’ The bitterness of the reflections expanded on in the Essai will not then astonish anyone: it was after suffering the mortal blow of a death sentence, between the judgement and the execution, that I composed that work. A writer who thinks he has reached his end, in poverty and exile, can hardly display a smiling face to the world.

But how to pass the period of grace allotted me? I could either live or die swiftly on my sword: physical effort was forbidden me; what was left? My pen? It was unknown and unproven and I did not know its power. Could my innate taste for literature, my childhood attempts at poetry, my travel sketches, suffice to attract the attention of the public? The idea of writing a work comparing the various Revolutions came to me; it occupied my mind as a subject appropriate to the concerns of the day; but who would undertake to print a manuscript without patrons, and during the composition of the manuscript, who would support me? Though I had only a few months left on earth, nevertheless it was necessary to have some means of living out those few months. My thirty louis, already much reduced, would not last long enough, and in addition to my specific needs, I ought to be alleviating the general distress of the émigrés. My companions in London all had occupations: some were in the coal trade; some made straw hats with their wives, others taught French they barely knew themselves. They were all very cheerful. The fault of our nation, its flippancy, at that time became a virtue. They laughed in the face of fortune; that thief sheepishly carried off what no one any longer demanded of her.

Book X: Chapter 5: Peltier – Literary effort – My friendship with Hingant – Our walks – A night in Westminster Cathedral

London, April to September 1822.

BkX:Chap5:Sec1

Peltier, author of Domine salvum fac Regem (God Save the King) and editor-in-chief of the Actes des Apôtres, continued his Parisian enterprises in London. He was not exactly prone to vice; but he was eaten by vermin, small faults of which he could not be purged: a libertine, a rebellious subject, making plenty of money and consuming the same, at once servant of the legitimacy and ambassador to George III for the Negro King Christophe, diplomatic correspond for Monsieur le Comte de Limonade, drinking as champagne the appointments for which he was paid in sugar. A kind of Monsieur Violet playing the fine tunes of the Revolution on a pocket violin, he came to see me, and offered me his services, as a Breton. I spoke to him of my idea for the Essai; he strongly approved: ‘That would be superb!’ he cried, and suggested a room at the house of his printer Baylis, who would print the work as it was created. Deboffe’s bookshop would handle the sale of it; he, Peltier, would trumpet it in his journal, while it could be inserted in the Courrier Français de Londres, whose editorship later passed to Monsieur de Montlosier. Peltier had no misgivings: he talked of getting me the Cross of Saint-Louis for my efforts at the siege of Thionville. My Gil Blas, tall, thin, difficult, with powdered hair and balding forehead, forever shouting and laughing, tipped his round hat over one ear, took me by the arm and led me to the printer, Baylis, where without any fuss he rented me a room, at the price of a guinea a month.

I was on the brink of a golden future; but as for the present, over what plank could I cross it? Peltier found work for me translating from Latin and English: during the day I laboured at these translations, at night on the Essai historique in sections of which I included my travels and my daydreams. Baylis provided me with books, and I employed a few shillings badly in buying others from the bookstalls.

Hingant whom I had met on the Jersey packet, became a close friend. He cultivated literary matters, was knowledgeable, and wrote novels secretly the pages of which he read to me. He lodged not far from Baylis, at the end of a street leading into Holborn. Every morning, at ten, I breakfasted with him; we talked about politics and above all about my work. I would tell him how much of my nocturnal edifice, the Essai, I had constructed; then I would return to my day’s work, translation. We met for dinner, at a shilling a head, in a public house; from there, we made for the fields. Often too we would go for walks alone, since the two of us were fond of musing.

BkX:Chap5:Sec2

I would make my way, in those days, towards Kensington or Westminster. Kensington pleased me; I would walk in the secluded part, while the part adjacent to Hyde Park was filled by a brilliant multitude. The contrast between my poverty and their wealth, my isolation and the crowd, suited me. With that confused longing with which my sylph used to afflict me, when having decked her out in all my follies I scarcely dared to raise my eyes to my handiwork, I would watch young Englishmen going by in the distance. Death, which I thought myself to be approaching, added mystery to this vision of a world which I had almost left. Did anyone cast an eye on the foreigner sitting at the foot of a pine-tree? Did some lovely woman divine the unknown presence of René?

At Westminster I had another pastime: in that labyrinth of tombs, I thought of my own, ready to open. The bust of an insignificant man like me would never have a place amongst these illustrious effigies. Then the royal sepulchres would loom: Charles I was not there and Cromwell was no longer there. The ashes of a traitor, Robert d’Artois, lay beneath the flagstones that I trod with loyal steps. The fate of Charles I had just been extended to Louis XVI; every day the steel reaped its harvest, in France, and the graves of my relatives had already been dug.

The singing of the choir and the conversation of visitors interrupted my reflections. I could not visit frequently, since it obliged me to give the wardens of those no longer living the shilling which I needed in order to stay alive. But instead I would circle the Abbey with the rooks, or stop to gaze at the towers, twins that appeared of unequal size, which the setting sun lit with its blood-red fires against the black backcloth of City smoke.

‘View in Westminster Abbey’

Holmes's Great Metropolis: or, Views and history of London in the Nnineteenth Century - William Gray Fearnside, Thomas Harrel (p157, 1851)

The British Library

One day, however, it so happened that wishing to contemplate the interior of the basilica, I was lost, at evening, in admiration of that bold, capricious architecture. Overcome by the feeling of the sombre immensity of Christian churches (Montaigne), I wandered about with slow steps, and was benighted: the doors were closed. I tried to find an exit; I called for the usher, and rattled the gates: all this noise, spreading and fading in the silence, was lost; I had to resign myself to sleeping among the dead.

After hesitating in my choice of bed, I stopped by the mausoleum of Lord Chatham, at the foot of the rood screen, and the double flight of steps to the Chapel of the Knights and of Henry VII. At the entrance to these stairs, these aisles closed by grills, a tomb built into the wall, facing a marble statue of Death armed with a spear, offered me shelter. The folds of a shroud, equally of marble, provided a niche: following Charles Quint’s example, I accustomed myself to my interment. I was lodged perfectly for seeing the world as it truly is. What heaps of grandeur are enclosed by those vaults! What remains of us? Our sorrows are no less vain than our joys; the unfortunate Jane Grey is no different from the happy Alys of Salisbury; only her skeleton is less dreadful, since it lacks a head; her carcass improved by her fate and the absence of that which gave her beauty. The tournaments of the victor of Crécy, the entertainments of Henry VIII’s Field of the Cloth of Gold, will not continue in this chamber of funereal sights. Bacon, Newton, Milton are as deeply buried, as eternally past, as their more obscure contemporaries. I, a poor, wandering, exile, would I consent to be no longer the little, sad neglected thing I was, in order to have been one of these famous dead, powerful and sated with pleasure? Oh, life is not about all that! If from the shores of this world we fail to see divine things clearly, let us not be surprised: time is a veil interposed between God and ourselves, as our eyelid is between our eye and the light.

‘The Tomb of Henry The Third, Westminster Abbey’

The Beauties of England and Wales - John Britton (p9, 1801)

The British Library

Concealed beneath my marble cloak, I lapsed from these lofty thoughts into my naïve impressions of place and time. My anxiety mixed with pleasure, was similar to that which I experienced in winter in my tower at Combourg, when I listened to the wind: a sigh and a shade are of like nature.

Gradually, I accustomed myself to the darkness, and made out the statues placed on the tombs. I gazed at the corbelled vaulting of the English Saint-Denis, from which one would have said past events and vanished years hung in a Gothic light: the whole edifice was like a monolithic temple of petrified centuries.

I counted ten hours, eleven by the clock; the hammer which rose and fell, on the bronze, was the only ‘living’ thing beside me in the place. Outside, a vehicle passing by, the cry of a watchman, that was all: those distant sounds of earth reached me in a world within a world. The Thames fog, and the smoke from the chimneys, infiltrated the basilica, and spread secondary shadows.

At last, a pre-dawn glow blossomed in a corner of dullest gloom: I gazed fixedly at the progressive growth of the light; did it emanate from the two sons of Edward IV, murdered by their uncle? ‘O, thus lay the gentle babes’, says the great tragedian, ‘.girdling one another within their alabaster innocent arms. Their lips were four red roses on a stalk, and in their summer beauty kiss’d each other.’ God did not send me those sad and tender souls; but the slender phantom of a barely adolescent girl carrying a light sheltered by a leaf of paper twisted like a shell: it was the little bell-ringer. I heard the sound of a kiss, and the bell rang for daybreak. The bell-ringer was utterly terrified when I exited with her through the cloister door. I told her my tale; she explained that she was there to carry out her father’s task because he was ill; we did not speak of the kiss.

Book X: Chapter 6: Distress – Unforeseen help – A lodging over a cemetery – New friends in misfortune – Our pleasures – My cousin La Bouëtardais

London, April to September 1822.

BkX:Chap6:Sec1

I amused Hingant with the tale of my adventure, and we decided to make a retreat at Westminster; but our poverty summoned us among the dead in a less poetic way.

My funds were running out: Baylis and Deboffe, in return for a written promise of reimbursement in case of poor sales, ventured to begin printing the Essai; it was the end of their generosity, and that was only natural; I was more surprised at their daring. No more translation work arrived: Peltier, being a man dedicated to pleasure, grew weary of his prolonged kindness to me. He would willingly have given me what he had, if he had not preferred spending it; but hunting for work here and there, and doing a good deed patiently, were impossibilities, to him. Hingant too saw his resources diminishing; between the two of us, we possessed only sixty francs. We cut down on our rations, as if on a prolonged voyage aboard ship. Instead of a shilling a head, we only spent sixpence on dinner. With our morning tea, we halved the amount of bread, and gave up butter. This abstinence frayed my friend’s nerves. It crazed him; he would prick up his ears as if he were listening for someone; then, as if in response, start laughing, or burst into tears. Hingant believed in magnetism, and confused his brain with Swedenborg’s gibberish. In the morning he would tell me of being disturbed by noises during the night; he grew angry if I ridiculed his imaginings. The anxiety he caused me prevented me from feeling my own sufferings.

They were significant, nevertheless: the rigorous diet, and my work, inflamed my diseased chest; I began to find difficulty in walking, yet I spent my days and part of my nights out of doors, so no one would be aware of my poverty. Down to our last shilling, my friend and I agreed to employ it to provide a semblance of breakfasting. We decided to buy a penny roll; and would allow the hot water and teapot to be brought as usual; we would not put the tea in, we would eat no bread, but we would drink the hot water, with a few of the small grains of sugar left at the bottom of the sugar-bowl.

Five days passed like this. Hunger consumed me; I was feverish; sleep deserted me; I sucked pieces of linen soaked in water; I chewed grass and paper. When I passed the bakers’ shops, the torment was terrible. One bitter wintry night, I stood for two hours outside a shop which sold dried fruit and smoked meat, devouring everything I saw with my eyes: I could have eaten not merely the food, but the boxes, baskets and trays.

BkX:Chap6:Sec2

On the morning of the fifth day, fainting from inanition, I dragged myself to Hingant’s room; I knocked at the door, it was locked; I called out, Hingant did not reply for a while; at last he got up and opened the door. He was laughing in an odd manner; his frock coat was buttoned up: he sat down at the tea table: ‘Our breakfast is on its way,’ he said, in a strange voice. I though I could see spots of blood on his shirt; I unbuttoned his coat swiftly: he had given himself a stab-wound, two inches deep, low on his left breast. I shouted for help. The maidservant ran for a surgeon. The wound was dangerous.

This new misfortune forced me to take action. Hingant, a counsellor at the High Court of Brittany, had refused to accept the payment that the British Government granted to French magistrates, just as I had declined the alms of a shilling a day for émigrés: I wrote to Monsieur de Barentin and explained my friend’s situation to him. Hingant’s relatives rushed to his side and took him off to the country. At that very moment, my uncle Bedée sent me forty crowns, a touching gift from my persecuted family; it seemed like all the gold of Peru to me: the gift of those prisoners of France supported the exiled Frenchman.

My poverty had become an obstacle to working. Since I no longer provided copy, printing had been suspended. Deprived of Hingant’s company, I relinquished my guinea-a-month lodging with Baylis; I paid the outstanding rent and left. Lower still than the needy émigrés who had proved my first patrons in London, were others, needier still. There are levels among the poor as among the rich; one can descend from the man who huddles with his dog against the winter cold, to the man who shivers in tattered rags. My friends found me a room better suited to my diminishing fortune (one is not always at the height of prosperity); they installed me near Marylebone Street, in a garret, its window overlooking a cemetery: each night the watchman’s rattle alerted me to the presence of body-snatchers. I had the consolation of knowing that Hingant was out of danger.

Friends visited my attic. Given our freedom and our poverty, we might have been taken for painters among the ruins of Rome: we were artists in destitution among the ruins of France. My figure served as a model and my bed as a seat for my pupils. This bed consisted of a mattress and a blanket. I had no sheets; in cold weather, a chair, my clothes, and the blanket, rendered me warm. Too weak to move my bed, it remained where God had placed it.

My cousin La Bouëtardais, hounded from an Irish hovel for failing to pay his rent, though he had left his violin as a pledge, came to me seeking shelter from the bailiff; a curate from southern Brittany loaned him a camp-bed. La Bouëtardais was, like Hingant, a counsellor at the High Court of Brittany; he had not a handkerchief to call his own; but he had deserted with bag and baggage, that is to say he had carried off his mitre-board and his red robe, and he slept beneath the purple by my side. When we could not sleep, being high-spirited and a good musician, with a fine voice, he would sit quite naked on his camp-bed, wearing his mitre-board, and singing ballads, accompanying himself on a guitar with only three strings. One night as the poor lad was humming the Hymn to Venus by Metastasio: Scendi propizia, he had a stroke, and his mouth became twisted: he eventually died of one, years later: thinking it the effect of a cold draught, I merely rubbed his cheeks, energetically. We would take council in our high chamber, we would discuss politics; we would fill our time with émigré gossip. In the evenings, we would go and dance at our aunts’ and cousins’ houses, fashionably beribboned, with our hats done up.

Book X: Chapter 7: A sumptuous reception – The end of my forty crowns – Fresh misery - Table d’hôte – Bishops – Dining at the London Tavern – Camden’s manuscripts

London, April to September 1822.

BkX:Chap7:Sec1

Those reading this part of my Memoirs are not aware that I have twice interrupted my writing of them: once, to offer a banquet for the Duke of York, brother of the King of England; and again, to give a reception marking the anniversary of the King of France’s return to Paris, on the 8th of July. This reception cost me forty thousand francs. Peers and Peeresses of the British Empire, ambassadors, and distinguished foreigners filled my splendidly decorated rooms. My tables shone with the glitter of London crystal, and the gold of Sèvres porcelain. There was an abundance of the finest dishes, wines and flowers. Portland Place was dense with gleaming carriages. Collinet, and Almack’s orchestra, charmed the fashionably melancholy dandies, and the dreamy beauty of the pensively dancing ladies. The Opposition and the Ministerial majority had called a truce; Lady Canning chatted with Lord Londonderry, Lady Jersey with the Duke of Wellington. Monsieur, who complimented me this year, 1822, on my lavish hospitality, had no idea that in 1793 there existed not far from him a future Minister, who pending greatness, fasted above a cemetery as a penance for his loyalty. Today, I congratulate myself on having been almost shipwrecked, glimpsed war, and shared the sufferings of the lowest class of society, just as I am thankful in times of prosperity for meeting slander and injustice. I have benefited from these lessons: life, without the ills which give it gravity, is a child’s bauble.

I was the man with forty crowns; but equality of wealth had not yet been established, and food was no cheaper, so there was nothing to offset my rapidly emptying purse. I could not count on further help from my family, exposed in Brittany to the double scourge of the Chouan insurrection and the Terror. I saw nothing ahead but the workhouse or the Thames.

The resourceful Peltier, dug me up, or rather unearthed me in my eyrie. He had read in a newspaper, in Yarmouth, that a group of antiquaries was preparing a history of the country of Suffolk, and were seeking a Frenchman capable of deciphering some twelfth-century French manuscripts from Camden’s collection. The parson of Beccles, was in charge of the enterprise, and it was him I needed to contact. ‘This is for you’ Peltier told me, ‘go: decipher these old papers; you can go on sending copy for the Essai to Baylis; I’ll force the coward to start printing again; and you’ll return to London with two hundred guineas, and your work done, come what may!’

I tried to stammer out my objections: ‘Ah! What the devil,’ he cried, ‘do you reckon on staying here, in this palace, where I’m already half-frozen? If Rivarol, Champcenetz, Mirabeau-Tonneau and I had been lily-livered, we’d have made a fine mess of the Actes des Apôtres! Do you know that this tale of Hingant made a hell of a row! You’d prefer both of you died of hunger, then? Ha! Ha! Ha! Pouf!...Ha! Ha!’ Peltier, bent in two, grasped his knees he was laughing so much. He had happened to sell a hundred copies of his newspaper to the Colonies; he had received payment and made the guineas jingle in his pocket. He took me away by force, with the apoplectic La Bouëtardais, and two ragged émigrés who were at hand, to dine at the London Tavern. He made us drink Port, and eat roast beef and plum pudding till we were bursting. ‘Monsieur le Comte,’ he said to my cousin, ‘why is your mouth all twisted?’ La Bouëtardais, half offended, half pleased, explained as best he could; he told him how he had a sudden seizure while singing those few words: O bella Venere! My poor stricken friend had so dead, so numb, so worn an air, while mutilating his bella Venere, that Peltier, convulsed with mad laughter, contrived to upset the table, striking it from below with both feet.

On reflection, the advice of my compatriot, truly a character invented by my other compatriot Le Sage, did not seem so bad. After three days spent making enquiries and being fitted out by Peltier’s tailor, I left for Beccles with some cash that Deboffe lent me, on the basis that I would resume writing the Essai. I altered my name, since the English could not pronounce it, to that of Combourg, which my brother had borne, and which recalled the pain and pleasure of my first youth. Ensconced at the inn, I presented the local minister with a letter from Deboffe, well regarded by the English literary world, which recommended me as a scholar of the first order. Well received, I met all the gentlemen of the district, and encountered two officers of our own Royal Navy who gave lessons in French to the neighbourhood.

Book X: Chapter 8: My provincial occupations – My brother’s death – Family misfortunes – Two Frances – Hingant’s letters

London, April to September 1822.

BkX:Chap8:Sec1

I regained my strength; the excursions I made on horseback restored my health somewhat. England, seen in detail, was gloomy, everywhere the same, with the same aspect. Monsieur de Combourg was invited to all the gatherings. I had my studies to thank for the first alleviation of my lot. Cicero was right to recommend the commerce of letters while among the sorrows of existence. The ladies were delighted to meet a Frenchman with whom they could speak French.

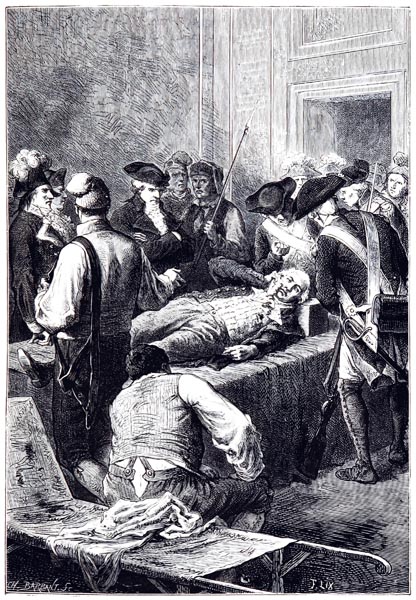

The misfortunes of my family, which I learnt of from the newspapers and which made my real name known, (since I could not conceal my grief) increased people’s interest in me. The public pages announced the death of Monsieur de Malesherbes; that of his daughter, Madame la Présidente de Rosanbo; that of his grand-daughter, Madame la Comtesse de Chateaubriand; and that of his grandson-in-law, the Comte de Chateaubriand, my brother, executed together, on the same day, at the same hour, on the same scaffold. Monsieur de Malesherbes was an object of admiration and veneration among the English; my family connection with the defender of Louis XVI added to my hosts’ kindness.

‘Man Climbing the Steps to the Guillotine’

Reinier Vinkeles, Daniël Vrijdag, 1793 - 1795

The Rijksmuseum

My uncle Bedée told me of the persecution suffered by my other relatives. My aged, incomparable mother had been thrown into a cart with other victims, and taken from the depths of Brittany to the gaols of Paris, in order to share the fate of the son she loved so dearly. My wife and my sister Lucile, were awaiting sentence in the dungeons at Rennes; there had been talk of imprisoning them in the Château of Combourg, which was to become a State stronghold: they were accused in their innocence of the crime of my emigration. What were our sorrows on foreign soil, compared to those of the French still living in their own land? Yet, how sad, in the midst of the sufferings of exile, to know that our very exile was a pretext for the persecution of those close to us!

Two years ago it was, that my sister-in-law’s wedding ring was found in the gutter of the Rue Casette; someone brought it to me; it was broken; its two entwined strands had come apart, and hung together like links of a chain; the names engraved there were perfectly legible. How had the ring been found? Where and when had it been lost? Had the victim, a prisoner in the Luxembourg, passed through the Rue Casette on the way to execution? Had she dropped the ring from the tumbril? Had it been torn from her finger after death? I was deeply moved at the sight of this emblem, which, by its state and its inscription, recalled such cruel events. Something fateful and mysterious attached itself to this ring, which my sister-in-law sent me from the place of the dead, as a token of herself and my brother. I have given it to her son: may it not bring him ill luck!

Dear orphan, image of your mother,

From heaven, for you, below, I ask,

The sweet days taken from your father,

The children that your uncle lacks.

This poor verse and two or three others are the only wedding gifts that I was able to fashion for my nephew when he married.

BkX:Chap8:Sec2

I have another relic of those misfortunes: here is what Monsieur de Contencin wrote to me, who, while searching the City archives, found the order of the Revolutionary Tribunal which sent my brother and his relatives to the scaffold:

‘Monsieur le Vicomte,

There is a kind of cruelty in awakening in the soul of someone who has suffered greatly the memory of those ills which have affected him the most grievously. This thought made me hesitate for a while before offering you an extremely sad document which came into my hands during my historical research. It is a death warrant signed before execution by a man who always showed himself as implacable as death, every time he found lustre and virtue showered on the same head.

I hope Monsieur le Vicomte that you will not be too dissatisfied with me for adding a paper to your family archives which revives such cruel memories. I assumed it would interest you, since I found it of value, and in consequence thought to offer it to you. If I am not being indiscreet, I can congratulate myself doubly, since I find the occasion, today, in taking this step, of expressing to you the feelings of profound respect and admiration which you have inspired in me, for many years, and with which I am, Monsieur le Vicomte,

Your very humble and obedient servant,

A. de Contencin.

Hôtel de la préfrecture de la Seine.

Paris, the 28th of March, 1835.’

Here is my reply to this letter:

‘I made a search, Monsieur, in Sainte-Chapelle, for the documents concerning my unfortunate brother’s trial, but no one could find the warrant which you have been so good as to send me. This warrant and so many others, with their erasures, their misspelled names, will have been presented to Fouquier before God’s Tribunal: there he would certainly have had to admit to his signature. Those were the times that some regret, and about which they write volumes in admiration! Nevertheless, I envy my brother: for many years he has been beyond this sad world. I thank you infinitely, Monsieur, for the esteem that you are pleased to show me in your fine and noble letter, and beg you to accept my assurance of the very great consideration with which I have the honour to be, etc.’

That death warrant is especially remarkable as evidence of the carelessness with which murder was committed: some names are wrongly spelled, others are erased. These formal errors, which would have been enough to invalidate the lightest sentence, did not halt the executioners; they were only exact in the matter of the hour of death: at five o’clock precisely. Here is the authentic document, copied here faithfully:

THE ENFORCER OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE

REVOLUTIONARY TRIBUNAL

The enforcer of criminal justice will not fail to attend the house of justice of the Conciergerie, in order to execute there the sentence which condemns Mousset d’Esprémenil, Chapelier, Thouret, Hell, Lamoignon Malsherbes, the wife of Lepelletier Rosambo, Chateau Brian and his wife (the correct name erased, unreadable), the widow Duchatelet, the wife of Grammont, former Duke, the wife of Rochechuart (Rochechouart), and Parmentier:

- 14, on pain of death. The execution will take place today, at five o’clock precisely, in the Place de la Révolution of this city.

The Public Prosecutor,

H. Q. Fouquier

Given at the Tribunal, the third Floréal, Year Two, of the French Republic.

Two carts.’

The 9th Thermidor saved my mother’s life; but she was left, forgotten, in the Conciergerie. The commissary for the Convention discovered her: ‘What are you doing here, citizeness?’ he asked; ‘Who are you? Why are you still here?’ My mother answered that having lost her son, she had no further interest in what was happening, and was indifferent as to whether she died in prison or elsewhere. ‘But perhaps you have other children?’ the commissary replied. My mother mentioned my wife and sisters, imprisoned at Rennes. An order to set them at liberty was swiftly sent, and my mother was compelled to leave.

‘Mort de Robespierre’

L'Histoire de France Depuis 1789 Jusqu'en 1848, Racontée à mes Petits-Enfants, par M. Guizot. Leçons Recueillies par Madame de Witt, Vol 01 - François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (p259, 1878)

The British Library

In histories of the Revolution, they omit to paint the external picture of France to set alongside the internal picture, one which reveals the great colony of exiles, varying its effort and industry to suit the diversity of climate and the different national customs.

Outside France, everything happened individually, through changes of condition, hidden sufferings, wordless sacrifices, without reward; yet in that plethora of individuals of every pedigree, age, and sex, one fixed concept was maintained; the old France was abroad with all its prejudices and loyalties, as once the Church of God wandered the earth with its virtues and its martyrs.

Inside France, everything operated en masse; Barère proclaimed murders and victories, civil wars and foreign wars; the titanic conflicts of the Vendée and the banks of the Rhine; thrones disintegrating at the sound of our marching armies; our fleets engulfed by the waves; the mob disinterring the monarchs at Saint-Denis, and throwing the dust of dead Kings in the faces of living ones to blind them; the new France, glorying in its new-found freedoms, proud even of its crimes, stable on its own soil, extending all its frontiers, doubly armed with the executioner’s blade and the soldier’s sword.

In the midst of my family grief, several letters arrived from Hingant reassuring me as to his fate, letters moreover of a remarkable nature: he wrote to me in September 1795: ‘Your letter of the 23rd of August is full of the most moving sentiments. I have shown them to several people who had tears in their eyes while reading them. I am almost tempted to say of them as Diderot said on the day when Rousseau shed tears over him in his prison, at Vincennes: “See how my friends love me.” My illness has only proved, in truth, a nervous fever which caused a great deal of suffering, and for which time and patience are the best remedies. I have been reading extracts from Phaedo and Timaeus. Those books give one an appetite for death, and I have said like Cato:

“It must be so, Plato; thou reason’st well!”

I conceived an idea of my voyage, as one conceives the idea of a voyage to the Indies. I imagined I saw hosts of new objects in the world of spirits (as Swedenborg calls it), and especially that I would be freed from the effort and danger of the voyage.’

Book X: Chapter 9: Charlotte

London, April to September 1822.

BkX:Chap9:Sec1

Six miles from Beccles, in a little town called Bungay, lived an English clergyman, The Reverend Mr. Ives, a great Hellenist and mathematician. He had a wife, still young, and of charming appearance, mind, and manners, and an only daughter, aged fifteen. Introduced to this household, I was better received there than anywhere else. We drank in the old English fashion, and stayed at table for two hours after the ladies had withdrawn. Mr Ives, who had been to America, liked to recount his travels, hear the story of mine, and talk about Newton and Homer. His daughter, who had studied in order to please him, was an excellent musician and sang as Madame Pasta does today. She re-appeared at tea and charmed away the old minister’s infectious drowsiness. Leaning on the end of the piano, I listened to Miss Ives in silence.

The music being over, the young lady questioned me on France, and literature; she asked me to draw up a plan of study for her; she particularly wanted to know the Italian authors, and begged me to give her some notes on the Divine Comedy and the Gerusalemme Liberata. Little by little, I began to experience the shy charm of an affection born in the soul: I had decked out the Floridians, but I would not have dared to pick up Miss Ives’ glove; I felt embarrassed when I tried to translate a passage from Tasso. I was more comfortable with that more masculine and chaste genius Dante.

Charlotte’s age and mine were complementary. Into relationships which form only in the midst of one’s life, a certain melancholy enters; if two people do not meet at the very outset, the memories of the beloved do not concern the part of one’s life when one breathed without knowing her: those days which belong to the society of others are painful to the memory and as if divorced from one’s true existence. Is there a disproportion of age? Then the drawbacks increase: the older began life before the younger was born; the younger is destined, in turn, to remain alone; one walked in solitude this side of the cradle, the other will traverse a solitude that side of the tomb; the past was a desert for the former, the future will be a desert for the latter. It is difficult to love and possess all the circumstances needed for happiness: youth, beauty, opportunity, taste, character, grace, and maturity.

After a fall from my horse, I stayed for some time at Mr Ives’ house. It was winter; my life’s dreams began to flee in the face of reality. Miss Ives became more reserved; she ceased to bring me flowers; she preferred not to sing.

If I had been told that I would spend the rest of my life, unknown, at the heart of this secluded family, I would have died of joy: love only needs continuance to become at once Eden before the Fall and a Hosanna without end. Make beauty stay, youth last, and the heart never tire, and you will recreate Heaven. Love is so assuredly the supreme happiness that it is haunted by an illusion of never-ending life; it only wishes to pronounce irrevocable vows; in the absence of joy, it seeks to make sorrow eternal; a fallen angel, it still speaks the language it spoke in its incorruptible habitation; its hope is never to die; in its twofold nature, possessed of its twofold illusions here, it tries to perpetuate itself by immortal thoughts and inexhaustible generation.

BkX:Chap9:Sec2

I looked forward with dismay to the time when I would be obliged to leave. On the eve of the day set for my departure, dinner was a gloomy affair. To my great astonishment, Mr Ives withdrew after dessert taking his daughter with him, and I was left alone with Mrs Ives: she was in a state of extreme embarrassment. I thought she intended to reproach me for an inclination she might have discovered but which I had never spoken of. She looked at me, lowered her eyes, and blushed; charming, as she was, in her confusion, there was no point of feeling that she might not have claimed for herself. At last, with an effort, overcoming the obstacle which prevented her speaking, she said to me, in English; ‘Sir, you have seen my confusion: I do not know if Charlotte pleases you, but it is impossible to deceive a mother; my daughter has certainly conceived an attachment for you. Mr Ives and I have discussed the matter; you suit us in every respect; we think you will make our daughter happy. You no longer possess a country; you have just lost your relatives; your property has been auctioned; who then could call you back to France? Until you inherit from us, you shall live with us.’

Of all the painful things I have endured, this was the greatest and most deeply felt. I threw myself at Mrs Ives’ feet; I covered her hands with my kisses and tears. She thought I was weeping with happiness, and began to sob with joy. She stretched out her arm to pull the bell-rope; she called to her husband and daughter: ‘Stop!’ I cried; ‘I am married!’ She fell back in a swoon.

I went out, and without returning to my room, I left on foot. I reached Beccles, and took the mail-coach for London, after writing a letter to Mrs Ives of which I regret not keeping a copy.

‘Four Horse-drawn Diligence’

Anonymous, 1825 - 1835

The Rijksmuseum

The sweetest, the most tender, and most grateful memory, of this event remain with me. Before I became known, Mr Ives’ family was the only one which took an interest in me, and welcomed me with real affection. Poor, obscure, proscribed, without looks or charm, I was offered a secure future, a country, a delightful wife to draw me out of my solitude, a mother almost her equal in beauty, to take the place of my aged mother, and a father, well-educated, loving and cultivating literature, to replace the father of whom Heaven had deprived me; what did I possess to compensate for all that? They could have had no illusions in choosing me: I could only consider myself loved. Since that time, I have only met with one attachment noble enough to inspire me with the same confidence. As for the interest of which I seemed to be the object later, I have never known whether or not external causes, the noise of fame, the prestige of party, the glamour of high literary or political status, were the cloak which attracted such eager attention to me.

For the rest, in marrying Charlotte Ives, my role in the world would have altered: buried in a county of England, I would have become a hunting gentleman: not a single line would have issued from my pen; I would even have forgotten my own language, since I could write English, and the thoughts in my head were starting to shape themselves in English. Would my country have lost much by my disappearance? If I were to set aside what has been my consolation, I would say I might have already reckoned on many peaceful days, instead of the troubled days that have been my lot. The Empire, the Restoration, divisions, the disputes within France, what would I have had to do with all that? I would not have had to counteract faults, and combat errors, each morning. Is it certain that I have a true talent, and a talent worth the painful sacrifices of my life? Will I outlast my tomb? When I pass beyond, will there be, given the transformations which will occur, in a world altered and preoccupied with other things, will there be a public to listen to me? Will I not be a man of the past, unintelligible to the new generations? Will my ideas, my sentiments, even my style not seem boring and old-fashioned to scornful posterity? Will my shade be able to say as Virgil’s did to Dante: ‘Poeta fui e cantai: I was a poet, and sang.’!

Book X: Chapter 10: Return to London

London, April to September 1822.

BkX:Chap10:Sec1

Returning to London, I found no peace: I had fled from my fate like a malefactor from his crime. How painful it must have been to a family so worthy of homage, respect and gratitude, to experience a species of rejection by the unknown they had welcomed, to whom they had offered a new home with a naturalness, an absence of suspicion, or precaution, patriarchal in character! I imagined Charlotte’s grief, the deserved reproaches that they could and would heap upon me: since I had after all been ready to abandon myself to an inclination which I knew was unquestionably wrong. Had I made a confused attempt at seduction, without taking account of the blame that would accrue to my conduct? But whether by halting, as I did, in order to remain a man of integrity, or by ignoring all obstacles in order to satisfy a desire already condemned by my conduct, I could only succeed in plunging the object of that seduction into regret or sorrow.

I allowed my mind to turn from these bitter reflections to other thoughts no less filled with bitterness: I cursed my marriage, which, contracted according to the false perceptions of my then disturbed mind, had thrown me off course, and robbed me of happiness. I did not realise that because of the innate malaise from which I suffered and the romantic notions of liberty I nourished, marriage with Miss Ives would have been just as painful to me as a freer union.

One thing pure and delightful, though profoundly sad, remained with me: the image of Charlotte; that image finally prevailed over my rebellion against my fate. I was tempted, a hundred times, to return to Bungay, not to present myself before the troubled family, but to conceal myself by the roadside to see Charlotte pass by, to follow her to the church where we had the same God, if not the same altar in common, to offer that girl, through the medium of Heaven, the inexpressible ardour of my vows, and to pronounce, at least in thought, the prayer from the marriage blessing that I might have heard from a clergyman’s lips in that church.

‘O, God, be pleased to join together the spirits of these two married people, and fill their hearts with true friendship. Look favourably upon your servant. Make their yoke one of love and peace, so that they may enjoy a happy fecundity; Lord, let these married people see before them their children and their children’s children to the third and fourth generation, and let them reach a happy old age.’

Drifting from resolution to resolution, I wrote Charlotte long letters which I destroyed. Each insignificant note I had received from her, served as a talisman; attached by my thought to my very steps, Charlotte, gracious, tender, followed me, in purifying them, along the paths of the sylph. She absorbed my faculties; she was the centre through which my intellect plunged, as blood passes through the heart; she made me disgusted with all other things, since I made of them perpetual objects of comparison, favourable to her. A true and blighted passion is a poisoned leaven that occupies the depths of the soul and spoils the bread of angels.

The places where I had been, the hours and words I had shared with Charlotte, were engraved in my memory: I saw the smile of the spouse who had been destined for me; I touched her black tresses, respectfully; I pressed her beautiful arms to my breast like a chain of lilies which I might have worn about my neck. I was no sooner in some secluded spot, than Charlotte of the white hands, came to sit at my side. I divined her presence, as one breathes, at night, the perfume of flowers which one cannot see.

Deprived of Hingant’s company, my walks, more solitary than ever, left me free to take with me Charlotte’s image. There is not a heath, road, or church within thirty miles of London that I have not visited. The most deserted places, a patch of nettles, a gap full of thistles, anything neglected by men, became favourite spots for me, and in those spots Byron already breathed. Head resting on my hand, I gazed at those places men scorned; when their painful impression affected me too deeply, the memory of Charlotte came to delight me: I was like the pilgrim, then, who reaching a desert solitude in sight of the rocks of Mount Sinai, had heard a nightingale sing.

‘Hampstead, from the Kilburn Road’

Old and New London: a Narrative of its History, its People, and its Places - Walter Thornbury (p7, 1873)

Internet Archive Book Images

In London, people were surprised at my behaviour. I looked at no one, I failed to reply, I did not understand what was said to me: my old friends considered me touched by madness.

Book X: Chapter 11: An astonishing encounter

London, April to September 1822.

BkX:Chap11:Sec1

What had happened at Bungay after I left? What became of that family to which I brought joy and grief?

You will bear in mind that I am now Ambassador to George IV, and write in London, in 1822, of what happened in London in 1797.

Official business obliged me, a week ago, to interrupt the narrative I am resuming today. One afternoon between twelve and one, during this interval, my valet came to tell me that a carriage was at the door, and that an English lady asked to speak to me. As I had made it a rule, in my public role, never to refuse to see anyone, I asked that the lady be shown upstairs.

I was in my study; Lady Sutton was announced; I saw a lady dressed in mourning enter, accompanied by two fine boys, also in mourning; one might have been sixteen years old, the other fourteen. I went to meet the stranger; she was so moved she could barely walk. She said to me in a faltering voice: ‘My lord, do you remember me?’ Yes, I recognised Miss Ives! The years which had passed over her head had left only their springtime behind. I took her by the hand: I made her sit, and sat down by her side. I could not speak; my eyes were filled with tears; I gazed at her in silence through those tears; I felt, from what I was experiencing, how deeply I had loved her. At last, I was able to say in turn: ‘And you Madame, do you recognise me?’ She raised her eyes, which she had kept lowered, and for sole response, gave me a smiling but melancholy glance like a long remembrance. Her hand was still between mine. Charlotte said to me: ‘I am in mourning for my mother; my father died some years ago. These are my children.’ Saying this, she withdrew her hand, and sank back into her chair, covering her eyes with her handkerchief.

Shortly she continued: ‘My lord, I am now speaking to you in the language which I practised with you at Bungay. I feel ashamed: forgive me. My children are the sons of Admiral Sutton, whom I married three years after you left England. But today I am not calm enough to enter into details. Permit me to return later.’ I asked for her address and gave her my arm to escort her to her carriage. She trembled, and I pressed her hand against my heart.