François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XI: First Literary Works 1798-1799

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XI: Chapter 1: A defect in my character

- Book XI: Chapter 2: The Essai historique sur les Révolutions – Its effect – A letter from Lemière, the nephew of the poet

- Book XI: Chapter 3: Fontanes – Cléry

- Book XI: Chapter 4: The death of my mother – Return to Religion

- Book XI: Chapter 5: Le Génie du Christianisme – A letter from the Chevalier de Panat

- Book XI: Chapter 6: My uncle, Monsieur de Bedée – His eldest daughter

Book XI: Chapter 1: A defect in my character

London, April to September 1822. (Revised December 1846)

BkXI:Chap1:Sec1

My relations with Deboffe regarding L’Essai sur les Révolutions had never completely lapsed, and it was important for me to re-establish them swiftly in London to support my everyday life. But where had my previous problems come from: my obstinate silence. To understand this, you need to delve into my character.

At no time has it been possible for me to overcome that spirit of reserve and inner solitariness that prevents me talking freely about what moves me. No one can affirm without lying that I have ever uttered what the majority of people utter in their moments of pain, pleasure or vanity. Names, confessions of any degree of seriousness, rarely or ever emerge from my lips. I never speak about my passing interests, my plans, my work, my ideas, my relationships, my joys, or my sorrows, persuaded of the profound ennui that one causes others in speaking of oneself.

Sincere and truthful, I lack openness of heart: my soul always tends to shut itself off; I have never spoken fully of any matter, and I have never revealed my life except in these Memoirs. If I try to begin a story, the thought of its length suddenly terrifies me; after three or four words, the sound of my own voice becomes intolerable and I fall silent. As I have no faith in anything, except religion, I challenge everything: ill-will and denigration are two characteristics of the French spirit; mockery and slander, the guaranteed result of any confidences.

What benefit have I gained then from my reticent nature: that of becoming since I seemed impenetrable a product of others’ imaginations, which bore no relation to my reality. Even my friends were in error concerning me, in thinking to make me better known, and embellishing me with the illusions conjured by their devotion. All the mediocrities of the antechamber, offices, news-sheets and cafes, considered me full of ambition, and I had none. Cold and detached in everyday matters, I showed nothing of the man of enthusiasm or sentiment: but my swift, precise perception quickly traversed men and events, and stripped them of all importance. Far from training me to idealize applied truth, my imagination brought the highest matters down to earth, disabusing me of my illusions. The petty and ridiculous aspect of things was always the first to strike me; to my eyes, hardly anything revealed genius or greatness. Polite, laudatory, admiring of the self-important who proclaimed themselves superior intellects, my secret contempt smiled and placed over all those faces wreathed in incense the masks of Callot. In politics, the warmth of my opinions never lasted longer than my speech or my pamphlet. In my inward and contemplative being, I was a man filled with dreams; in my outward and practical being, a man of realities. Adventurous yet orderly, passionate yet methodical, there has never been a creature more fanciful and yet practical than I, more ardent and more icy; strangely androgynous, formed of the differing seed of my mother and my father.

The portraits painted of me, lacking any real resemblance, owe that fact principally to the reticence of my speech. The crowd is too superficial, too inattentive to give time, unless it has been alerted beforehand, to viewing individuals as they truly are. Whenever, by chance, I have tried to counter one of these false judgements in my prefaces, no one has believed me. In the last resort, all things being equal, I have not insisted; an as you will always freed me from the tedium of trying to persuade anyone, or seeking to prove the truth. I retreated into my heart’s depths, like a hare into its form: there I again set myself to contemplating the movement of a leaf or the angle of a blade of grass.

I do not make a virtue of my unassailable circumspection in as much as it is involuntary: though it is not insincerity it has the appearance of it; it is not in harmony with happier, kinder, more easy-going, more innocent, more abundant, more communicative natures than mine. It has often harmed me in matters of feeling, and business affairs, because I could never endure explanations and reparations by means of protestations and clarifications, lamentation and tears, verbiage and reproaches, details and apology.

In the case of the Ives family, this obstinate silence of mine, regarding myself, was fatal to me in the extreme. Twenty times Charlotte’s mother had enquired about my parents and had brought me to the verge of revelation. Not foreseeing where my muteness would lead, I was content, as usual, to reply in a few brief vague words. If I had not suffered from that hateful spiritual fault, no error would have been made, and I would not have displayed the appearance of having deceived the most generously hospitable of people: the truth, spoken by me at the decisive moment, does not excuse my behaviour: a real wrong was committed nevertheless.

I resumed my work in the midst of my sorrows and the just reproaches I heaped on myself. I accustomed myself to the work, since it occurred to me that in acquiring fame I would render the Ives family less regretful of the interest they had shown in me. Charlotte, whom I sought to reconcile myself to through renown, presided over my labours. Her image sat before me while I wrote. When I lifted my eyes from the paper, they rested on the beloved image, as though the original had been there in reality. The inhabitants of the island of Ceylon saw the daystar rise one day in unparalleled splendour: its sphere opened, and out of it came a shining creature which said to the Ceylonese: ‘I am come to reign over you.’ Charlotte, bathed in a shaft of light, reigned over me.

Let us forego these memories; memories age, and vanish, like our hopes. My life is about to change, it will unfold under other skies, in other valleys. First love of my youth, you flee with your charms! I happened to see Charlotte again, it is true, but how many years later was it, that I did see her again? Sweet light of the past, pale rose of the twilight, which edges the night, when the sun has long set!

Book XI: Chapter 2: The Essai historique sur les Révolutions – Its effect – A letter from Lemière, the nephew of the poet

London, April to September 1822.

BkXI:Chap2:Sec1

Life has often been represented (by me above all), as a mountain which one climbs from one side, to hurtle down the other: it would also be valid to compare it to one of the Alps, its bald summit crowned with ice, which has no far side. Pursuing this image, the traveller always ascends and never descends; thus he has a better view of the distance he has travelled, the paths he has not taken and with whose help he would have been elevated by an easier slope: he gazes with regret and sadness at the point where he started to go astray. So, it is from the publication of the Essai historique that I must mark the first step of mine that made me stray from the path of peace. I had completed the first part of the great work I had planned; I wrote the last words of it caught between the idea of death (I had fallen ill again) and a vanished dream: In somnis venit imago conjugis: the image of a spouse appeared in sleep. Printed by Baylis, the Essai appeared in Deboffe’s bookshop in 1797. The date is that of a transformation in my life. There are moments when our destiny, whether yielding to social pressures, obeying the dictates of nature, or commencing to make of us what we will become, suddenly swerves from its initial path, like a river changing course around a sudden bend.

The Essai offers a compendium of my existence, as poet, moralist, publicist and politician. To say that I hoped, inasmuch at least as I was able to hope, a great success for the work, that goes without saying: we lesser authors, little prodigies of a prodigious era, we have pretensions of maintaining a conversation with the future race; but we have no knowledge, to my mind, of posterity’s place of residence, we pen its address incorrectly. When we sleep in the tomb, death will freeze our words, written or sung, so solidly, they will not melt again like Rabelais’ frozen words.

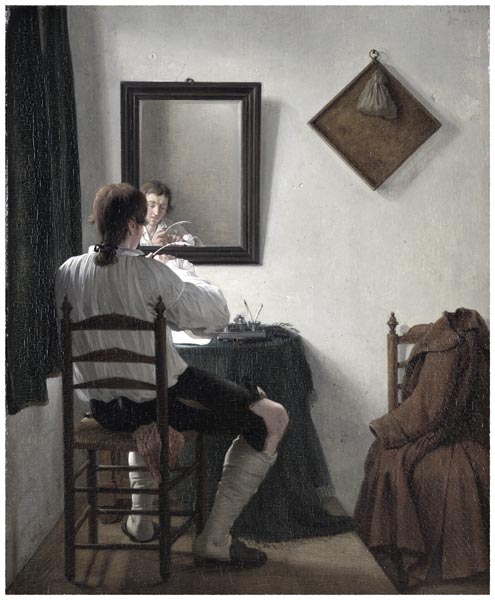

The Essai became a sort of historical encyclopaedia. The only volume published was already a sufficiently deep investigation; I had the remainder in manuscript, then a poet’s lays and virelais arrived to accompany the annalist’s researches and annotations, then the Natchez, etc. I can scarcely understand today how I managed to carry out such extensive labours, in the midst of an active life, a wanderer subject to so many reverses. My tenacity when working explains this fecundity: in my youth, I have often written for twelve to fifteen hours with getting up from the table at which I sat, editing and reworking the same page a dozen times. I have not lost this ability for application with age: my diplomatic correspondence now, which is not allowed to interrupt my literary compositions, is entirely from my own hand.

‘A Writer Trimming his Pen’

Jan Ekels (II), 1784

The Rijksmuseum

The Essai made a stir among the émigrés: it was in contradiction to the views of my companions in misfortune: my independence regarding diverse social attitudes has almost always wounded the men with whom I have been aligned. I have in turn been the commander-in-chief of various armies whose soldiers were not of my own party: I have led the old Royalists to the achievement of public freedoms, and above all that of the freedom of the press, which they detested; I have rallied the liberals in the name of that same freedom to the Bourbon flag which they regarded with horror. Émigré opinion happened to attach itself, through pride, to my person: the English Revues, having spoken of me in glowing terms, their praise reflected on the whole corps of the faithful.

I had sent copies of the Essai to Laharpe, Ginguené and De Sales. Lemierre, nephew of the poet of that name and translator of Gray’s verses, wrote to me from Paris, on the 15th of July 1797, to tell me that my Essai was a great success. It is true that the Essai was acknowledged for a moment, it was also soon forgotten: a sudden shadow engulfed my first rays of fame.

Having become nigh on well-known, the émigré nobility sought me out in London. I made my way from street to street; I first left Holborn-Tottenham Court Road, and advanced as far as the Hampstead Road. There I stayed several months at the home of Mrs O’Larry, an Irish widow, mother of a very pretty fourteen year old daughter, and fond cat-lover. Bound by this mutual passion, we had the misfortune to lose two elegant cats, white as ermine, with black tips to their tails.

Elderly neighbours visited Mrs O’Larry, with whom I was obliged to take tea according to the ancient custom. Madame de Staël has depicted the scene in Corinne at Lady Edgermond’s house: ‘My dear, do you think the water is hot enough to add it to the tea? – My dear, I think that would be premature.’

A very beautiful young Irish lady, Mary Neale, also came to these soirees escorted by her guardian. She found some pain in the depths of my gaze, for she said to me: ‘You carry your heart in a sling’. I carried my heart I don’t know how.

Mrs O’Larry left for Dublin; then moving once more from the eastern district colonised by poor émigrés, I progressed from lodging to lodging, as far as the western quarter of rich émigrés, among the bishops, families of the Court, and colonists from Martinique.

Peltier was back; he had married heedlessly; always boastful, wasting his resources, and frequenting his neighbours’ money rather than their persons.

I made several new acquaintances, especially in the circles where I had family connections. Christian de Lamoignon, badly wounded in the leg in the Quiberon affair, and now a colleague in the Chamber of Peers, became my friend. He presented me to Mrs Lindsay, a friend of Auguste de Lamoignon, his brother: not quite as President Guillaume de Lamoignon was installed at Basville, between Boileau, Madame de Sevigné and Bourdaloue.

Mrs Lindsay, of Irish origin, with a dry wit, a somewhat abrupt manner, elegant height, and a pleasant figure, had nobility of soul and an elevated character: émigrés of note spent the evening at the fireside of this last Ninon. The old monarchy perished with all its abuses and all its graces. It will be disinterred one day, like those skeletons of queens, adorned with necklaces, bracelets, and earrings that they exhume in Etruria. At this rendezvous I encountered Monsieur Malouët and Madame du Belloy, a woman deserving of relationship, the Comte de Montlosier and the Chevalier de Panat. The latter had a well-earned reputation for his wit, slovenliness, and greed: he belonged to that set, of men of taste, who used to sit arms crossed before French society; idlers whose mission was to see everything and judge everything, they exercised the functions newspapers now exercise, without possessing their bitterness, but also without achieving their immense popular influence.

BkXI:Chap2:Sec2

Montlosier was forced to travel because of his famous phrase about the cross of wood, a phrase which I reshaped a little, when I quoted it in the Génie, but which is profoundly true. On leaving France, he went to Coblentz; received badly by the Princes, he was involved in a duel, fought at night on the banks of the Rhine and was spitted. Unable to move, and seeing no blood, he asked the witnesses if the sword point had emerged behind: ‘Three inches’ they said after feeling around. ‘Then it’s nothing,’ Montlosier replied, ‘sir, withdraw your thrust’

Montlosier, welcomed thus for his royalist sympathies, crossed to England, and took refuge in literature, the great hospital for émigrés where I had a straw-pallet next to his. He obtained the editorship of the Courrier de Londres. Beside his newspaper, he wrote physico-politico-philosophical works: in one of these tracts he demonstrated that blue was the colour of life because the veins turned blue after death, which indicated that life was returning to the body’s surface in order to evaporate and return to the blue heavens: as I liked blue very much, I was quite charmed.

Feudally liberal, an aristocrat and democrat, a strange spirit, made of bits and pieces, Montlosier gave birth with difficulty to disparate ideas, but when he could manage to free them from the natal cord, they were often fine, and always full of vigour: opposed to priests as he was to noblemen, converted to Christianity by means of sophisms, while a lover of ancient times, he had been, under the influence of paganism, a warm supporter of freedom in theory and slavery in practice, who would feed the slave to the fish in the name of the liberty of the human race. Crushing in argument, a quibbler, daring and tousled, the former deputy of the Riom nobility nevertheless permitted himself to make concessions to the powerful: he knew how to manage his interests, but allowed no one to see him at it, and hid his weaknesses as a man behind his honour as a gentleman. I will hear nothing evil said of my hazy Auvernat, with his ballads of Mont-d’or and his polemics of the Plain; I had a liking for his heterogeneous personality. The long obscure development and swirl of his ideas, with its parentheses, throaty gasps, and tremulous cries of: ‘oh! oh!’ bored me (the shadowy, muddled, vaporous, and tiresome, I find abominable); but on the other hand, I was diverted by this naturalist of the volcanic regions, this lost Pascal, this orator from the mountains who ranted to the gallery as his little compatriots, the sweeps, sang from the heights of their chimneys; I liked this journalist of peat bogs and little castles, this liberal explaining the Charter through a Gothic window, this shepherd lord half-wedded to his cowgirl, sowing his barley himself, in the snow, in his little stony field: I was always grateful to him for having dedicated to me, in his hut in the Puy-de-Dôme, an ancient black stone, taken from a cemetery of the Gauls which he had discovered.

BkXI:Chap2:Sec3

The Abbé Delille, another compatriot of those Auvernats, Sidoine Apollinaire, the Chancelier de l’Hospital, La Fayette, Thomas, and Chamfort, driven from the Continent by the torrent of Republican victories, had also recently established himself in London. The Emigration counted him among its ranks with pride; he sang our ills, even more reason to be enchanted with his muse. He worked hard; he had to, since Madame Delille locked him up, and only let him out when he had filled his day with a certain number of lines. One day, I had gone to see him; he was delayed, and then appeared, with very red cheeks: they say that Madame Delille used to slap him; I don’t know; I only say what I saw.

Who has not heard the Abbé Delille declaim his verse? He speaks very well; his person, ugly, rumpled, animated by imagination, wonderfully suits the charm of his delivery, the nature of his talent, and his priestly profession. The Abbé Delille’s masterpiece is his translation of the Georgics, in parts close to the original in feeling; but it is as if you were reading Racine translated into the language of Louis XV.

Eighteenth century literature, aside from the few fine geniuses that dominate it, that literature placed between the classical literature of the seventeenth century and the romantic literature of the nineteenth, without lacking naturalness, lacks nature; dedicated to the arrangement of words, it is neither sufficiently original like the new school, nor sufficiently pure like the old school. The Abbé Delille was the poet of modern châteaux as the troubadour was the poet of old ones; the verse of the one, the ballads of the other, reveal the difference between the aristocracy at the centre of power, and the aristocracy in a state of degeneration: the Abbé depicts readings and games of chess in country houses, where the troubadours sang of crusades and tourneys.

BkXI:Chap2:Sec4

The distinguished members of our Church Militant were then in England: the Abbé Carron, of whom I have spoken already, in borrowing from his life of my sister Julie; the Bishop of Saint-Pol-de-Léon, a severe and narrow-minded prelate, who contributed to separating Monsieur le Comte d’Artois further and further from his century; the Archbishop of Aix, slandered perhaps because of his worldly success; another wise and pious bishop, but so avaricious, that if had experienced the misfortune of losing his soul, he would never have bought it back. Almost all misers are men of intelligence: I ought to be totally stupid.

Among the French in the western region of London, one might name Madame de Boigne, charming, spiritual, full of talent, extremely pretty and the youngest of all; she has since represented, with her father, the Marquis of Osmond, the French Court, in England, much better than my savagery achieved. She writes now, and her talent depicts what she has seen, wonderfully well.

Mesdames de Caumont, de Gontaut, and du Cluzel also inhabited that quarter of exiled felicity, that is, if I am not confused regarding Madame de Caumont and Madame du Cluzel, whom I had audience with in Brussels.

Madame la Duchesse de Duras, was certainly in London at this time; I would not meet her till ten years later. How many times in life one passes by what would give delight, like a sailor crossing the waters of a land enamoured of the sun, which he has missed, beyond the horizon, by a day’s sailing! I write this by the banks of the Thames, and tomorrow a letter will go in the post to tell Madame de Duras, on the banks of the Seine, that I have met again with my first memory of her.

Book XI: Chapter 3: Fontanes – Cléry

London, April to September 1822.

BkXI:Chap3:Sec1

From time to time, the Revolution brought us émigrés of a new kind with fresh opinions; various layers of exiles formed: as the earth contains beds of sand or clay, deposited by the waves of the flood. One of these waves brought me a man whose demise I still deplore today, a man who was my guide in literature and whose friendship has been one of the honours and consolations of my life.

In Book IV of these Memoirs you have seen that I met Monsieur de Fontanes in 1789: it was last year, in Berlin, that I learnt the news of his death. He was born at Niort, of a noble and Protestant family: his father had the misfortune to kill his brother-in-law in a duel. The young Fontanes, raised by a very worthy brother, came to Paris. He saw Voltaire die, and that great representative of the eighteenth century inspired his first lines: his poetic attempts were noticed by Laharpe. He undertook several works for the theatre, and befriended a charming actress, Mademoiselle Desgarcins. Lodged near the Odéon, wandering around the Chartreuse, he celebrated solitude there. He had met a friend destined to become mine also, Monsieur Joubert. The Revolution arrived: the poet became involved with one of those static parties that vanishes: torn apart by the party of progress which drags it forward, and the retrograde party which holds it back. The monarchists connected Monsieur de Fontanes with the editorship of the Modérateur. When times grew worse, he took refuge at Lyon, and married there. His wife gave birth to a son: during the siege of the town which the Revolutionaries had named a Commune affranchie (liberated), as Louis XI, while banishing its citizens, had called Arras a Ville franchise, Madame de Fontanes was obliged to move her infant’s cradle to protect it from the shelling. Returning to Paris after the 9th Thermidor, Monsieur de Fontanes founded the Mémorial, with Monsieur de Laharpe and the Abbé de Vauxelles. Proscribed on the 18th Fructidor, England became his port of refuge.

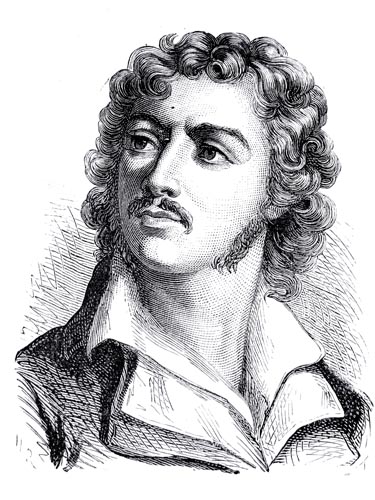

‘Fontanes’

Morceaux Choisis: Extraits des Oeuvres Complètes - Vicomte de François-René Chateaubriand (p606, 1915)

Internet Archive Book Images

Monsieur de Fontanes has been, with Chénier, the last writer of the elder branch of the Classical school: his prose and his verse are akin and belong to the same order of merit. His thoughts and imagery possess a forgotten melancholy from the age of Louis XIV, which only recognises the austere and sacred sadness of religious eloquence. That melancholy is found amongst all the works of the bard of Jour des Morts, like the imprint of the age in which he lived; it fixes the date of his appearance; it shows that he was born after Rousseau, in his taste adhering to Fénelon. If one were to reduce the writings of Monsieur de Fontanes to two quite thin volumes, one of prose, the other of verse, they would form the most elegant of funeral monuments that one could raise over the tomb of the Classical school. (It is to be raised through the filial piety of Madame Christine de Fontanes; Monsieur de Saint-Beuve has adorned the pediment of the monument with his ingenious words. Note: Paris, 1839)

Among the papers my friend left behind, may be found several cantos of a poem on Grece sauvée, books of odes, and diverse poems, etc. He published nothing more himself: since that critic, so subtle, enlightened, and impartial, when political opinion did not blind him, had a terrible fear of criticism. He had been royally unjust towards Madame de Staël. In an article on the Forêt de Navarre, Garat, full of envy, thought to cut short his poetic career at its inception. Fontanes, on his appearance, killed off the affected school of Dorat, but was unable to re-establish the Classical school which ultimately touched on the language of Racine.

Among the posthumous odes of Monsieur de Fontanes, there is one on the Anniversary of his Birth: it has all the charm of Jour des Morts, with a deeper and more personal sentiment. I only remember these two verses:

‘Age is already here with its sufferings:

Brief hopes? Are they all the future brings?

What does the past grant? Errors, and regret.

Such is man’s destiny; he learns with age:

But what use is the sage,

Now so little time is left?

Past, present, future, they all grieve me:

Life in its decline for me lacks glory;

In the mirror of time, its charms are gone.

Pleasure! Go seek love and youthfulness;

Leave me to sadness,

And do not condemn!’

If anything in the world was bound to be antipathetic to Monsieur de Fontanes, it was my literary style. A revolution in French literature began with me, and the so-called Romantic school: however, my friend, instead of being revolted by my barbarity, conceived a passion for it. I saw immense amazement on his face when I read bits of Les Natchez, Atala and René to him; he could not analyse these works according to normal critical rules, rather he realised that he was entering a new world; he saw nature afresh; he understood a language which he could not speak. I received excellent advice from him; I owe to him whatever is correct in my style; he taught me to respect the sounds; he prevented me from falling into over-extravagant invention and the harshness of execution of my disciples.

It was a great joy to meet him again in London, feted by the emigration; they demanded cantos of Grèce sauvée from him; they crowded round to hear. He lodged near me; we were never apart. We assisted together at a scene worthy of those unfortunate times: Cléry having recently disembarked, we read the manuscript of his Memoirs. Imagine the emotion of an audience of exiles, listening to the valet de chambre of Louis XVI, recounting, as an eye witness, the suffering and death of the prisoner of the Temple! The Directory, fearing Cléry’s memoirs, published an edition of them with interpolations, which had the author speaking like a lackey and Louis XVI like a street-porter: among the base tricks of the Revolutionaries, this was one of the nastiest.

BkXI:Chap3:Sec2

A Peasant From the Vendée

Monsieur du Theil, Monsieur the Comte d’Artois’ chargé d’affaires in London, was quick to seek out Fontanes: he in turn begged me to introduce him to the Princes’ agent. We discovered him surrounded by all the defenders of the throne and altar who walked the pavements of Piccadilly, by a host of spies and knights of industry who had escaped from Paris under various names and disguises, and by a swarm of adventurers, Belgian, German, Irish, vendors of counter-revolution. In a corner of this crowd was a man of thirty to thirty-two whom no one noticed, and who only paid attention himself to an engraving of the death of General Wolfe. Struck by his appearance, I enquired about his person: one of my neighbours replied: ‘He’s no one; a peasant from the Vendée, a messenger with a letter from his leaders.’

This man, who was no one, had seen Cathelineau die, the first general of the Vendée and a peasant like himself; Bonchamp, in whom Bayard lived again; Lescure, armed with a hair-shirt, no proof against a bullet; General d’Elbée, executed by firing squad while seated in an armchair, his wounds preventing him from meeting death while standing; and La Rochejaquelein, whose death the patriots ordered verified, so as to reassure the Convention in the midst of its victories. This man, who was no one, had been involved in the capture and re-capture of towns, villages, and redoubts, in seven hundred individual actions and seventeen formal battles; he had fought against an army of three hundred thousand regulars, and six to seven hundred thousand conscripts and National Guards; he had helped to capture a hundred canon, and fifty thousand rifles; he had passed through the columns from hell, companies of incendiaries commanded by Conventionnels; he found himself in the midst of an ocean of fire, which, on three occasions, rolled its waves towards the woods of the Vendée; at last, he had seen three hundred thousand Hercules of the plough perish, companions in labour, and seen a thousand square miles of fertile country change to a desert of ashes.

The two Frances met on this ground levelled for them. Every drop of blood, every memory of the France of the Crusades that still remained, combated whatever of fresh blood, and hope existed in Revolutionary France. The victor acknowledged the greatness of the vanquished. Turreau, the Republican general, declared that: ‘the Vendeans will be placed by history in the front rank of military nations.’ Another general wrote to Merlin de Thionville: ‘Troops who have beaten such Frenchmen can well take pride in fighting all the other nations.’ The legions of Probus, in their song, say as much of their forefathers. Bonaparte called the battles of the Vendée ‘the battles of giants.’

‘Merlin de Thionville, Engraved by E.Thomas from the Design by H. Rousseau’

Album du Centenaire, Grands Hommes et Grands Faits de la Révolution Française (1789-1804) - Augustin Challamel, Desire Lacroix (1889)

Wikimedia Commons

In the waiting room crowd, I was the only person to treat with admiration and respect this representative of the ancient Jacques, who, in throwing off the yoke of their lords completely, under Charles V, repulsed the foreign invader: I seemed to be looking at a son of those communes of the age of Charles VII, who with the minor provincial nobility, re-conquered the soil of France, foot by foot, furrow by furrow. He had the indifferent air of a savage; his look was grey and inflexible like a rod of iron; his lower lip quivered over gritted teeth; his hair hung from his head in serpent locks, seemingly lifeless, but ready to spring upwards again; his arms, hanging by his sides, gave a nervous twitch to enormous wrists marked by sabre cuts; he might have been taken for a sawyer of longstanding. His physiognomy expressed a working man’s rustic nature, placed, by the powers that be, at the service of ideas and interests contrary to that nature; the inborn fidelity of the vassal, the simple faith of the Christian, mingled there with a rough plebeian independence accustomed to value itself and do itself justice. The feeling for liberty seemed in him to be no more than the strength of his hand and the intrepidity of his heart. He spoke no more than a lion does; he scratched himself like a lion, yawned like a lion, turned to one side like a bored lion, dreaming, it would seem, of blood and the wild: his knowledge was like that of the dead.

What men, everywhere, the French were then: what a race we are today! But the Republicans had their leadership with them, amongst them, while the Royalist leadership was outside France. The Vendéans deputed for the exiles; the giants sent a request for leadership to the pygmies. The rustic messenger I gazed at had seized the Revolution by the throat, and cried out: ‘Come; follow me; it will do you no harm; it can’t move; I’m holding it.’ No one wanted to follow: then Jacques Bonhomme released the Revolution once more, and Charette broke his sword.

BkXI:Chap3:Sec3

My Walks With Fontanes

While I was indulging in these reflections on the ploughman, like those of another sort I had indulged in at the sight of Mirabeau and Danton, Fontanes obtained a private audience with the person he called amusingly the Controller General of Finances: he emerged highly satisfied, since Monsieur du Theil had promised to support the publication of my works, and Fontanes thought only of me. It was impossible to find a better man: reticent regarding what concerned himself he was all courage for a friend; he showed it, at the time of my resignation following the death of the Duke d’Enghien. In conversation he bristled with ridiculous literary passions. In politics, he talked nonsense; the crimes of the Convention had induced in him a horror of liberty. He detested the newspapers, philosophizing, ideology, and he communicated that dislike to Bonaparte, when he drew near the master of Europe.

We went on walks in the countryside; we would stop beneath one of those large spreading elms in the meadows. Leaning against the trunk of the elm, my friend would tell me about his former travels in England before the Revolution, and recite the lines he had once addressed to two young ladies, who had become old in the shadow of the towers of Westminster; those towers which he had found standing as he had left them, while at their base were buried the hours and illusions of his youth.

We often dined in some solitary tavern in Chelsea, beside the Thames, and talked of Milton and Shakespeare: they had seen what we were seeing; had sat like us by the river, for us a foreign river, for them that of their homeland. At night we returned to London, in the fading light of the stars, which submerged one after another in the City fog. We reached our lodgings, guided by the flickering lamps which barely marked a route for us through the smoke from coal fires reddened around each street light: so passes the life of a poet.

We saw London in detail: an experienced exile, I served as cicerone to the conscripted exiles that the Revolution produced, young and old: there was no legal age to qualify for unhappiness. In the middle of one of these excursions, we were surprised by a thunderstorm, and were forced to take refuge in the alleyway of an insignificant mansion whose door was by chance open. There we met the Duke de Bourbon: I saw for the first time, at this Chantilly, a prince who was not yet the last of the Condés.

The Duke de Bourbon, Fontanes and I, all equally proscribed, sought shelter, on foreign soil, under a poor man’s roof, from the same storm! Fata viam invenient: Fate finds a way.

Fontanes was recalled to France. He embraced me, vowing that we would soon be reunited. Arriving in Germany, he wrote me the following letter:

28th of July 1798.

‘If you have felt regret at my departure from London, I swear to you that mine has been no less real. You are the second person in whom, in the course of my life, I have found a heart and imagination like my own. I will never forget the consolations you have introduced me to, in exile and in a foreign land. My dearest and most constant thought, since I left you, concerns Les Natchez. What you read me of it, especially in those last days, is admirable, and has not vanished from my memory. But the charm of the poetic ideas you left me with disappeared in an instant on my arrival in Germany. The most terrible news from France has followed that which I showed you on leaving. I spent five or six days in the cruellest perplexity. I even feared my family might be persecuted. My terrors are much abated today. Even the misfortunes have been quite light; they threaten more than they perpetrate, and it is not against people of my age that the executioners bear a grudge. The last mail brought me assurances of peace and goodwill. I can continue my journey, and will be travelling at the beginning of next month. I will be staying close to the forest of Saint-Germain, with my family, my Gréce, and my books, how can I not add Les Natchez too! The unexpected storm that has just taken place in Paris was caused, I am certain, by the blunders of the leaders and agents you know of. I have had obvious proof of it in my hands. Because of my certainty, I am writing to Great Pulteney Street (where Monsieur du Theil is staying), with all possible politeness, but also with all the care that prudence demands. I wish to avoid all correspondence next month, and I am leaving it totally in doubt as to whom I will take with me, and the location I select. As to other things, I still speak of you in accents of friendship, and wish with all my heart that the hopes of my being useful to you, that you may have vested in me, nourish the warm feelings shown me in that regard, and which are so much due to your person and great talent. Work, work, my dear friend, and become illustrious. You can achieve it: the future is yours. I hope that the promise so often repeated by the Controller General of Finances is at least fulfilled in part. That consideration consoles me, since I cannot endure the thought that a fine work might be lost for lack of support. Write to me; let our hearts commune, let our muses always be friends. Never doubt that, as long as I can travel our country freely, I shall be preparing a beehive and a flowery glade for you there, next to mine. My friendship is unalterable. I will be lonely in so much as I am not with you. Tell me about your labours. I wish you the joy of completing them: I have finished half of a new canto on the banks of the Elbe, and I am happier with it than with all the rest.

Adieu, I embrace you tenderly, and am your friend,

Fontanes.’

Fontanes tells me he is composing verse while changing his place of exile. One can never rob a poet of all he has; he carries his lyre with him. Leave the swan its wings; each night unknown waves will repeat melodious cries that would be better heard on the Eurotas.

The future is yours: did Fontanes speak true? Ought I to congratulate myself on his prediction? Alas! The future he announced is already past: shall I possess another.

That first affectionate letter from the foremost friend I encountered in my life, and who after that date marched in step with me for twenty-three years, warns me painfully of my increasing isolation. Fontanes is no more; a profound grief, the tragic death of a son, sent him to the grave before his time. Almost all the people I have spoken of in these Memoirs have vanished; it is a Register of Deaths that I hold. A few more years, and I, condemned to catalogue the dead, will leave no one behind to inscribe my name in the book of absentees.

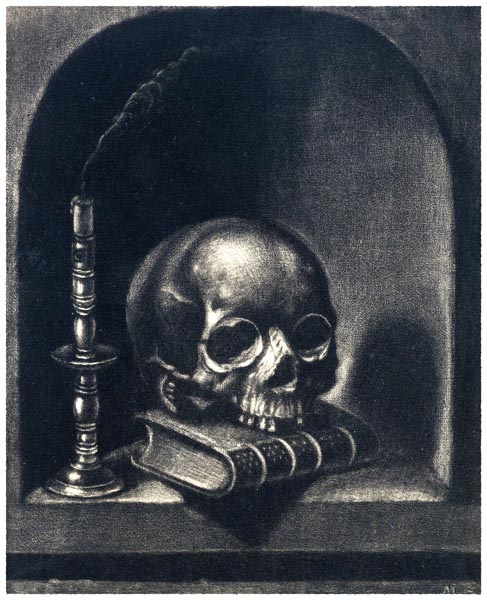

‘An Allegory of Transience’

Harmen de Mayer, Wallerant Vaillant, 1651 - 1701

The Rijksmuseum

But if I must remain alone, if no other being who loves me remains to conduct me to my last refuge, I need a guide less than others: I am making my enquiries about the road, I have studied the places I must pass through, I have sought to know what happens at the last. Often, at the edge of a grave into which the coffin is lowered by means of ropes, I have heard the ropes groan; then I have heard the sound of the first spade-full of earth fall on the coffin: at each new spade-full the hollow noise diminished; the earth in filling up the hole, made the eternal silence above the surface of the coffin deepen, little by little.

Fontanes! You wrote to me: Let our muses always be friends; you did not write in vain.

Book XI: Chapter 4: The death of my mother – Return to Religion

London, April to September 1822.

BkXI:Chap4:Sec1

‘Alloquar? audiero numquam tua verba loquentem?

Nunquam ego te, vita frater amabilior,

Aspiciam posthac? at, certe, simper amabo!’

‘Am I never to speak to you? Never to hear your voice? Never to see you, brother more beloved than life? Ah! I will always love you!’

I had just lost a friend, I then lost a mother: it was necessary to repeat the lines Catullus addressed to his brother. In our valley of tears, just as in hell, there is some unknown eternal lament, which represents the lowest depth or the dominant note of human grief; one hears it ceaselessly, and it would continue if all created pain should chance to fall silent.

A letter from Julie which I received shortly after that of Fontanes, confirmed my sad remark regarding my progressive isolation: Fontanes urged me to work, to become illustrious; my sister pressed me to renounce writing: one proposed glory, the other oblivion. You have seen from my account of Madame de Farcy that she was prone to such ideas; she had grown to hate literature, because she regarded it as one of her life’s temptations.

Saint-Servan, 1st July 1798.

‘My dear, we have just lost the best of mothers; it is with regret that I tell you of this sad blow. We shall have ceased to live, when you cease to be the object of our solicitude. If you knew how many tears your errors have caused our venerable mother to shed, how deplorable they appear to all who think and profess not only piety but reason; if you knew this, perhaps it would help to open your eyes, and induce you to renounce writing; and if Heaven, moved by our prayers, permits our reunion, you will find all the happiness among us that can be enjoyed on earth; you would grant us that happiness also, since there is none for us, as long as we lack your presence, and have reason to be anxious about your fate.’

Ah! Why did I not follow my sister’s advice! Why did I go on writing? If my times had lacked my writings, would anything of the events and spirit of those times have altered?

Thus, I had lost my mother; thus I had troubled her last hours! While she was breathing her last sigh far from her last living son, praying for him, what was I doing, here in London? Perhaps I was out walking in the cool of the morning, while the death-sweat was drenching my mother’s brow, and my hand not there to wipe it away!

The filial affection I retained for Madame de Chateaubriand went deep. My childhood and youth were intimately linked to the memory of my mother; all I knew came to me from her. The idea that I had poisoned the last days of the woman who carried me in her womb, made me despair: I threw my copies of the Essai into the fire, as the instrument of my crime; if it had been possible for me to annihilate the work, I would have done so without hesitation. I did not recover from this grief until the idea came to me of expiating the effect of my first work by a religious work: this was the origin of Le Génie du Christianisme.

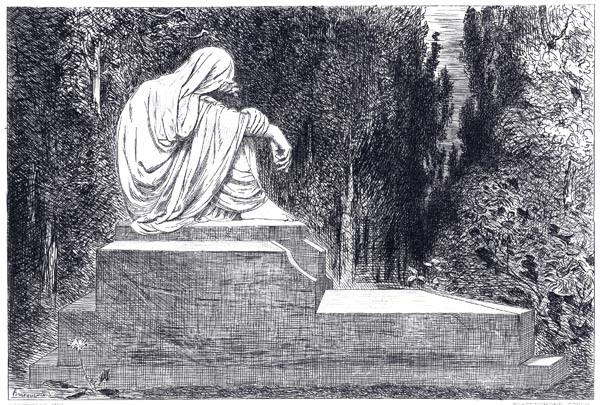

‘My mother,’ I wrote in the first preface to that work, ‘after being locked in jail at the age of seventy-two, imprisoned there still when one of her sons died, expired eventually on the pallet to which her misfortunes had brought her. The memory of my errors cast a great bitterness over her last days; at her death, she charged one of my sisters with recalling me to the religion in which I was raised. My sister sent me details of my mother’s last desire. When that letter reached me across the sea, my sister herself was no more; she too had died of the effects of her imprisonment. Those two voices from the tomb, that death which acted as Death’s interpreter, impressed me powerfully. I became a Christian. I did not yield, I must admit, to great supernatural enlightenment: my conviction came from the heart; I wept and I believed.’

‘Monument Funèbre au Cimetière Montmartre’

Félix Bracquemond, A. Salmon, 1860 - 1867

The Rijksmuseum

I exaggerated my faults; the Essai was not an impious book, but a book of doubt and sorrow. Through the shadows of that book, glides a ray of the Christian light that shone on my cradle. It required no great effort to return from the scepticism of the Essai to the certainty of Le Génie du Christianisme.

Book XI: Chapter 5: Le Génie du Christianisme – A letter from the Chevalier de Panat

London, April to September 1822.

BkXI:Chap5:Sec1

When, after the sad news of Madame de Chateaubriand’s death, I resolved to make a sudden change of course, the title Le Génie de Christianisme, which I thought of instantly, inspired me; I set to work; I laboured at it with the ardour of a son building a mausoleum to his mother. My material was that which my previous studies had been gathering and rough-hewing for some time. I knew the works of the Fathers better than they are known these days; I had studied them in order to oppose them and having entered on that path with ill intentions, instead of leaving it as victor, I left it vanquished.

As to history proper, I had occupied myself with it specifically in composing the Essai sur les Révolutions. The Camden antiquities I had recently examined had made me familiar with the institutions and manners of the Middle Ages. Finally my daunting manuscript of Les Natchez, of two thousand three hundred and ninety-three folio pages contained all the Génie du Christianisme might need in the way of nature description: I could draw heavily on that source, as I had already for the Essai.

I wrote the first part of the Génie du Christianisme. Dulau, who had become booksellers to the émigré French clergy, agreed to publish it. The first sheets of the first volume were printed.

The work thus begun in London in 1799 was only completed in Paris, in 1802: see the different prefaces to Le Génie du Christianisme. A species of fever consumed me during the whole time of its writing: no one will ever know what it was like to carry Atala and René at the same moment in one’s brain, blood and soul, and to involve in the painful birth of those passionate twins the effort of composing the remaining parts of Le Génie du Christianisme. The memory of Charlotte penetrated and warmed it all: moreover a first longing for glory inflamed my exalted imagination. This longing arose in me from filial tenderness; I wanted to create a great stir, so that the sound of it would rise to where my mother was, and the angels would bring her my solemn expiation.

As one item of study leads to another, I could not occupy myself with French scholarship, without taking account of the people and literature amongst which I was living; I was drawn towards this other research. My days and nights were spent in reading, writing, taking lessons in Hebrew from a knowledgeable priest, the Abbé Caperan, consulting the libraries and men of learning, roaming the fields with my endless daydreams, and in making and receiving visits. If there are retroactive effects, ones symptomatic of future events, I ought to have been able to detect the noise and tremor of the work which was to make me famous, in the seething of my spirit and the palpitations of my muse.

A few readings of my first sketches served to inform me. Readings provide excellent input, as long as they do not involve the obligation to flatter for money. As long as an author is honest, he soon knows, from other’s instinctive reaction, the weak parts of his work, and especially whether the work is too long or too short, whether he has kept to, fallen short of, or exceeded the just measure. I received a letter from the Chevalier de Panat concerning readings of the as yet unknown work. The letter is delightful: the sharp wit and mockery of the slovenly Chevalier had not seemed open to addressing itself to poetry in this way. I do not hesitate to give you this letter, documenting my history, though it is smeared from end to end with praise, as if the shrewd author had taken pleasure in spilling his inkwell over his letter:

‘This Monday.

Goodness! What a fascinating reading, this morning, which I owe to your extreme kindness! Our religion has counted among its defenders great geniuses, illustrious Fathers of the Church: those athletes handled all the weapons of reason with vigour; unbelief was vanquished; but that was insufficient; it was necessary to demonstrate all the charms of that admirable religion; it was necessary to show how suited it is to the human heart, and reveal the magnificent pictures it offers to the imagination. It is not here a theologian of the schools, but a great painter and man of feeling who reveals a fresh horizon. Your work was missed, and you were called to do it. Nature has endowed you liberally with the fine qualities it demanded: you belong to another century.

Ah! If the truths of feeling come first in the order of nature, no one will demonstrate those of our religion more adequately than you; you will confound impiety at the door of the temple and you will introduce sensitive spirits and feeling hearts to the inner sanctuary. You picture again for me those ancient philosophers who gave out their teachings their heads crowned with flowers and their hands full of sweet perfumes. That is indeed a weak representation of your spirit, so tender, classical and pure.

I congratulate myself every day on the happy circumstance that brought me close to you; I cannot ever forget that it was through Fontane’s generosity; I love him the more, and my heart will never distinguish between two names which fame must unite, if Providence should open for us the gates of our country.

Chevalier de Panat.’

The Abbé Delille also heard the reading of several extracts from Le Génie du Christianisme. He seemed surprised, and he did me the honour, a little later, of versifying the prose that had pleased him. He naturalised my savage flowers of America in his various French gardens, and cooled my wine, which was a little too heated, in the icy water of his clear fountain.

The incomplete edition of Le Génie du Christianisme, which I had begun in London, differs somewhat in its order of contents from the edition published in France. The Consular Censor, who soon became the Imperial one, showed himself to be extremely touchy on the question of kings: their person, honour and virtue were already dear to him in anticipation. Fouché’s police could already see the white dove with the sacred phial descending from the sky, symbols of Bonaparte’s ingenuousness and of revolutionary innocence. The sincere believers in the Republican processions at Lyon forced me to cut a chapter entitled the Royal atheists, and to disseminate the paragraphs of it here and there in the body of the work.

Book XI: Chapter 6: My uncle, Monsieur de Bedée – His eldest daughter

London, April to September 1822.

BkXI:Chap6:Sec1

Before continuing these literary considerations, I must interrupt them a moment, to take leave of my uncle Bedée: alas, that is to take leave of my life’s first joys: freno non remorante dies: there is no bridle to curb the flying days. Consider the ancient tombs in ancient crypts themselves conquered by age, blank and lacking titles, having lost their inscriptions, they are forgotten like the name of those they enclose.

I had written to my uncle on the subject of my mother’s death; he replied to me in a long letter, in which were touching words of regret; but three quarters of his double folio pages were dedicated to my genealogy. Above all he recommended me, when I returned to France, to research the arms quartered with Bedée, conferred on my brother. Thus, for this venerable émigré, there had been neither exile, nor ruin, nor the destruction of close relatives, nor the execution of Louis XVI, nor the warning presented by the Revolution; nothing had changed, nothing had occurred; he was still at the point of the Breton States, and the Assembly of Nobles. This fixity in the man’s ideas is most striking in the midst of and the presence of the alterations to his body, the flight of the years, the loss of his relatives and friends.

When the émigrés returned, my uncle Bedée retired to Dinan, where he died, seven miles from Monchoix, without seeing it again. My cousin Caroline, the eldest of my three cousins, is still alive. She remains an old maid, despite the respectful advances made to her former youth. She writes me letters devoid of spelling, where she addresses me as tu, calls me Chevalier, and talks of the good old days: in illo tempore: in those times. She was blessed with beautiful dark eyes and a pretty waist; she danced like La Camargo, and she thinks she remembers that in secret I bore her a shy love. I reply in the same tone, setting aside, as she has, my age, my honours and my fame: ‘Yes, dear Caroline, your Chevalier etc.’ It is thirty or so years since we met: Heaven be praised! For, God knows, if we ever came to embrace to each other, what a figure we should cut!

Gentle, patriarchal, innocent, honourable family friendship, your age has passed! We are no longer tied to the earth by a multitude of roots, shoots and flowers; we are born and die now, one by one. Those living are urged to hurl the dead into Eternity, and dispose of the corpse. Among friends, some attend the coffin to the church, muttering about the loss of time and the disturbance to their routine; others take their devotion as far as following the procession to the cemetery; the grave filled, all memory is effaced. You will never return, days of religion and tenderness, when the son died in the same house, the same chair, close to the same hearth where his father and grandfather had died, surrounded, as they had been, by weeping children and grandchildren, on whom the last paternal blessing descended!

![Grave of Chateaubriand [Adaptation, A. D. Kline 2015]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Chateaubriand/interior_chateaubriand_memoirs_bk11chap6sec1.jpg)

‘Grave of Chateaubriand [Adaptation]’

A Ramble round France - J. Chesney (p33, 1885)

The British Library

Adieu, my dear uncle! Adieu, my mother’s family, which is vanishing like the rest of my family! Adieu, my long ago cousin, you who love me still, as you loved me when we listened to our good aunt Boisteilleul lamenting over The Sparrow-hawk, or when you assisted at the repetition of my nurse’s prayer, in the Church of Notre-Dame de Nazareth! If you survive me, accept the share of gratitude and affection I bequeath you here. Never think the smile that shaped itself on my lips, in speaking of you, was a false one: my eyes, I assure you, are full of tears.

End of Book XI