François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XII: England, and Return to France 1799-1800

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XII: Chapter 1: DIGRESSIONS: English Literature – The withering away of the old schools – Historians – Poets – Publicists - Shakespeare

- Book XII: Chapter 2: DIGRESSIONS: Old Novels – New novels – Richardson – Walter Scott

- Book XII: Chapter 3: DIGRESSIONS: The new poetry – Beattie

- Book XII: Chapter 4: DIGRESSIONS: Lord Byron

- Book XII: Chapter 5: England from Richmond to Greenwich – A trip with Peltier – Blenheim – Stowe – Hampton Court – Oxford – Eton College – Private life; political life – Fox – Pitt – Burke – George III

- Book XII: Chapter 6: The Émigrés return to France – The Prussian Minister grants me a false passport under the name of Lassagne, a resident of Neuchâtel, in Switzerland – The end of my career as a soldier and traveller – I land at Calais

Book XII: Chapter 1: DIGRESSIONS: English Literature – The withering away of the old schools – Historians – Poets – Publicists - Shakespeare

London, April to September 1822. (Revised February 1845)

BkXII:Chap1:Sec1

My studies related to Le Génie du Christianisme led me gradually (as I have said) to a deeper study of English literature. When, after 1792, I sought refuge in England, I was forced to revise most of the judgements I had garnered from the critics. With regard to historians, Hume was renowned as a Tory and a backward-looking writer: he was accused, like Gibbon, of having overloaded the English language with Gallicisms; his heir, Smollett, was preferred. A philosopher during his life, who became a Christian before his death, Gibbon was remembered, in that way, as moved and converted by man’s poverty. One still spoke of Robertson because of his terseness.

As regards the poets, Elegant Extracts introduced the exile to selections from Dryden: one did not excuse Pope’s rhymes, though one visited his house at Twickenham and cut a twig from the weeping willow planted by him, withering like his fame.

Blair was considered a critic tedious after the French manner: he was placed well below Johnson. As for the old Spectator, it was consigned to the attic.

English political works held little interest for us. Treatises on economics were less limited; calculations concerning the wealth of nations, the employment of capital, and the balance of trade, applied in part to European countries.

Burke took on a national political identity: in declaring himself opposed to the French Revolution, he drew his country into that long train of hostilities which ended on the field of Waterloo.

However, the great figures remained. One encountered Milton and Shakespeare in particular. Did Montmorency, Biron, Sully, successively French ambassadors to Elizabeth I and James I, never hear tell of a strolling player, an actor in his own comedies and those of others? Did they ever pronounce the name, so barbarous in French, of Shakespeare? Did they suspect that there a glory existed before which their honours, their pomp, their rank, would be nullified? Well! The actor charged with the role of the ghost in Hamlet, was the great phantom, the shadow of the Middle Ages who rose above the world, like the star of night, at the moment in which those ages descended among the dead: vast centuries which Dante opened and Shakespeare closed.

‘Milton’

The Prose Works of John Milton; with an introductory review by R. Fletcher - John Milton (p10, 1833)

The British Library

In the Memorials of Whitelocke, a contemporary of the bard of Paradise Lost, one reads of: ‘A certain blind person, named Milton, Latin Secretary to the Parliament.’ Molière, the ham, played Pourceaugnac, while Shakespeare, the buffoon, grimaced as Falstaff.

Those veiled travellers, who appear from time to time to sit at our table, are treated by us as ordinary guests; we ignore their true nature until they day they vanish. Leaving earth, they are transfigured, and say to us like the heavenly messenger to Tobit: ‘I am one of the seven who appear before the Lord.’ But if they are misjudged by men in their travels, these divinities are not misjudged by each other. ‘What needs my Shakespeare,’ wrote Milton, ‘for his honour’d bones, the labour of an age in piled stones?’ Michelangelo envying the destiny and genius of Dante; cried:

‘Fuss’io pur lui! .

Per l’aspro esilio suo, co’ la virtute,

Dare’ del mondo il più felice stato.’

‘To be such as him! For his bitter exile and his virtue, I would give the world’s greatest joys!’

Tasso celebrated Camoëns who was still almost unknown, and served to make him famous. Is there anything more admirable than this society of illustrious equals revealing themselves to each other by means of signs, greeting each other, and speaking together in a language belonging only to themselves?

Was Shakespeare lame like Lord Byron, Walter Scott and the Prayers, daughters of Jupiter? If indeed he was, the Stratford Boy, far from being ashamed of his infirmity, like Childe Harold, did not fear speaking of it to one of his mistresses:

‘...lame by fortune’s dearest spite.’

Shakespeare should have had many loves, if one reckoned one per sonnet. The creator of Desdemona and Juliet grew old without ceasing to be in love. Was the unknown woman addressed in delightful verse proud and happy to be the subject of Shakespeare’s sonnets? One may doubt it: fame is for an old man what diamonds are for an old woman; they adorn but cannot improve.

‘No longer mourn for me when I am dead’, says the English tragedian to his mistress, ‘...if you read this line, remember not the hand that writ it; for I love you so, that I in your sweet thoughts would be forgot, if thinking on me then should make you woe. Oh, if, I say, you look upon this verse, when I perhaps compounded am with clay, do not so much as my poor name rehearse, but let your love even with my life decay.’

‘William Shakespeare’

First Folio. Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies - William Shakespeare (1623)

The British Library

Shakespeare loved, but he thought no more of love than other things: a woman for him was a flower, a bird, a breeze, something delightful that passes. Through heedlessness or ignorance of his future destiny, through his birth, which found him far from rank, beyond conditions which he could not affect, he seems at first to have taken life for a thoughtless, unoccupied hour, as a swift, sweet moment of leisure.

Shakespeare, in his youth, met aged monks turned out of their cloisters, who had met with Henry VIII’s reforms, his dissolution of the monasteries, his fools, wives, mistresses, executioners. When the poet left this life, Charles I was sixteen years old.

So, with one hand Shakespeare might have touched the white hairs, which the sword of the last Tudor but one threatened, with the other the dark haired poll of the second Stuart, removed by the axe of the Parliamentarians. Pressing on those tragic brows, high Tragedy thrust them into the grave; he filled the intervening years of his life with ghosts, blind kings, ambitious men punished, and unfortunate women, in order to link, by his parallel fictions, the reality of the past to the reality of the future.

Shakespeare is among the five or six writers who possessed all that was needed to nourish thought; these mother-geniuses seem to have given birth to and suckled all the rest. Homer created Classical antiquity: Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes, Horace, Virgil are his sons. Dante engendered modern Italy, from Petrarch to Tasso. Rabelais created French literature; Montaigne, La Fontaine, Molière were his descendants. England is all Shakespeare, and even in modern times he has given his language to Byron, his dialogue to Walter Scott.

Frequently one renounces these great masters; one rebels against them; one tallies their faults; one accuses them of being boring, over-long, idiosyncratic, in bad taste, while stealing and dressing oneself in their feathers; but one struggles in vain under their yoke. All is painted in their colours; everywhere is imprinted with their steps; they invented words and names which went to swell the common vocabulary of nations; their expressions became proverbs, their fictional characters changed into real characters which possess heirs and a lineage. They opened up horizons from which rays of light pour; they sowed ideas, seeds of a thousand others; they furnished images, subjects, styles to all the arts: their works are the mines or the wombs of the human spirit.

Such geniuses occupy the first rank; their immensity, variety, fecundity, originality, made them known above all for their rules, examples, forms, types of diverse intelligence, as if there were four or five human races, derived from a single stem of which the rest are merely the branches. Let us be wary of criticising the disorder into which these powerful beings sometimes fell; let us not imitate the cursed Ham; let us not laugh if we encounter, naked and asleep, in the shadow of the grounded Ark in the mountains of Armenia, the one and only navigator of the flood. Let us respect the diluvian sea-captain who recommenced the creation when the waterfalls from the sky had ceased: pious children, blessed by our father, let us cover him discreetly with our cloak.

Shakespeare, in his lifetime, never thought he would live on after his life was done: what does my hymn of admiration matter to him today? In admitting all these suppositions, in reasoning about the truths or errors with which the human spirit is penetrated or filled, what does fame mean to Shakespeare, the noise of which cannot rise to his level? A Christian? In the midst of eternal joys, does he trouble himself about the nothingness of earth? A Deist? Free of the shades of matter, lost among the splendours of God, does he cast a glance towards the grain of sand where he passed his life? An Atheist? He lies in a sleep without breath or re-awakening, called death. Nothing is vainer, then, than glory beyond the tomb, unless it has given life to friendship, been an aid to virtue, a helper in adversity, and allowed us to enjoy the heaven of an idea, consoling, generous, and liberating, left behind by us on earth.

Book XII: Chapter 2: DIGRESSIONS: Old Novels – New novels – Richardson – Walter Scott

London, April to September 1822.

BkXII:Chap2:Sec1

The novel, at the end of the last century, was included in the general condemnation. Richardson rested forgotten; his compatriots found traces in his style of the inferior society at the heart of which he had lived. Fielding held his own, Sterne, purveyor of originality, was passé. One still read The Vicar of Wakefield.

If Richardson has no style (of which we are no judges, we foreigners), he will not live, since one only lives because of one’s style. It is vain to rebel against this truth: the best composed work, adorned with fine likenesses, full of a thousand other perfections, is still-born if it lacks style. Style, and there are a thousand different ones, is not learnt; it is a gift of the gods, it is talent. But if Richardson has only been forgotten because of certain middle class mannerisms, unacceptable to elegant society, he can be revived; the Revolution which operates by dethroning the aristocracy and elevating the middle classes will render less obvious or eliminate the marks of inferior ways of living and speaking.

From Clarissa and Tom Jones derive the two principal branches of the genre of modern English novels, those novels picturing the family and domestic drama, and the novels of adventure showing society in general. After Richardson, the manners of the west of the city forced their way into the domain of fiction: novels were full of country houses, lords and ladies, scenes on the water, adventures on horseback, at the ball, the Opera, at Ranelagh, with chit-chat, a cackling that never ended. The scene swiftly transported itself to Italy; lovers crossed the Alps among terrifying dangers and agonies of soul enough to move lions: the lion sheds tears! was a phrase adopted in the best company.

Among those thousands of novels which have flooded England in the last half-century, two have retained their place: Caleb Williams and The Monk. I never saw Godwin during my exile in London; but I met Lewis twice. He was a very pleasant young Member of the Commons, who had the look and manner of a Frenchman. The works of Anne Radcliffe were a species apart. Those of Mrs Barbauld, Miss Edgeworth, Miss Burney, etc, have, they say, a likelihood of survival. ‘There ought to be laws,’ says Montaigne, ‘against inept and useless scribblers, as there are against vagabonds and loafers. They should ban the use of people’s hands, mine and a hundred others. Scribbling seems to be a kind of symptom of a hyper-active age.’

But these diverse schools of sedentary novelists, of novelists who travel in stage-coach and carriage, of novelists of lake and mountain, ghosts and ruins, novelists of cities and salons, have recently been subsumed in the new school of Walter Scott, even as poetry has thrown itself at Lord Byron’s feet.

The illustrious portrayer of Scotland began his literary career, during my London exile, with a translation of Goethe’s Götz von Berlichingen. He continued to make himself known through his poetry, while the slant of his genius led him at last to the novel. He seems to me to have created an artificial genre; he has perverted both novel and history; novelists have begun creating historical novels and historians novelistic history. If, in Walter Scott, I am sometimes obliged to skip the interminable dialogue, that is unquestionably my fault; but one of the great merits of Walter Scott, in my eyes, is to be read by the whole world. It takes a greater effort of genius to create interest while maintaining order, than to please while exceeding all measure; it is less easy to rule the heart than to trouble it.

‘Sir Walter Scott’

The Poetical Works of Sir Walter Scott - Sir Walter Scott (p10, 1882)

The British Library

Burke pinned English politics to the past, Walter Scott took the English back to the Middle Ages; everything he wrote, made, built, was Gothic: books, furniture, houses, churches, mansions. But the lords of Magna Carta are today the fashionables of Bond Street; a frivolous race encamped in ancient stately homes, awaiting the arrival of future generations ready to drive them forth.

Book XII: Chapter 3: DIGRESSIONS: The new poetry – Beattie

London, April to September 1822.

BkXII:Chap3:Sec1

At the same instant that the novel entered a Romantic state, poetry was subject to a like transformation. Cowper abandoned the French school in order to revive the national school; Burns, in Scotland, commenced the same revolution. After them came the restorers of the ballad form. Several of these poets of 1792 to 1800 belonged to the Lake School (the name has lasted), since these Romantics lived by the lakes of Cumberland and Westmoreland, and sometimes wrote of them.

Thomas Moore, Campbell, Rogers, Crabbe, Wordsworth, Southey, Hunt, Knowles, Lord Holland, Canning, Croker, still live to honour English letters; but one must be born English to wholly appreciate the merits of an intimate style of composition particularly to the taste of men of that country.

Nothing, in a living literature, is judged competent except works written in the native language. It is in vain to think you possess a foreign idiom in all its depth, you failed to imbibe it with your nurses’ milk, those first words that she taught you at her breast, on your tongue; certain notes belong to their homeland. Among our forms of literature, English and German own to the strangest ideas: they delight in what we scorn, they scorn what we take delight in; they pay no attention to Racine, La Fontaine, nor Molière in his entirety. It makes one laugh to learn what they make of our great writers in London, Vienna, Berlin, St Petersburg, Munich, Leipzig, Göttingen, Cologne, to learn what they read there avidly, and what they do not read.

When an author’s chief merit is his verbal style, a stranger will never fully comprehend his merit. The more intimate, individual, national a talent, the more its mysteries escape the mind that is not, so to speak, a compatriot of that talent. We admire the Greek and Romans by hearsay; our admiration comes to us by tradition, and the Greeks and Romans are not here to mock our Barbarian pronunciation. Who of us has any idea of the harmony of Demosthenes’ prose, or Cicero’s, of the cadence of Alcaeus’ verse or Horace’s, such as they were received by a Greek or Latin ear? It is said that true beauty is of all time, and every country: yes, beauties of feeling and thought; not the beauties of style. Style is not, like thought, cosmopolitan: it has a native soil, a sky, a sun of its own.

Burns, Mason, Cowper died during my exile in London, before and in 1800; they ended the century; I began one. Erasmus Darwin and Beattie died a couple of years after my return from exile.

Beattie had announced a new era of the lyre. The Minstrel, or the Progress of Genius, depicts the first effects of the Muse on a young bard, still ignorant of whose breath torments him. Now the future poet goes and sits by the sea-shore during a storm; now he leaves the village fair to listen, apart, to the sound of distant music.

Beattie has covered the entire series of daydreams and melancholy ideas of which a hundred other poets thought themselves discoverers. Beattie intended to continue his poem; in fact he wrote the second canto of it: Edwin hears a solemn voice lifted one evening from a valley’s depths; it is that of a solitary who, having come to know the world’s illusions, has buried himself in this retreat in order to win back his soul and sing the wonders of the Creator. This hermit instructs the young minstrel and reveals the secret of his genius to him. The idea was a happy one; the execution did not quite match the happiness of the idea. Beattie was destined to weep; the death of his son broke the father’s heart; like Ossian after the loss of his son Oscar, he hung his harp from the branches of an oak-tree. Perhaps Beattie’s son was that young minstrel that a father sang of and whom he no longer saw walking the mountain-side.

Book XII: Chapter 4: DIGRESSIONS: Lord Byron

London, April to September 1822.

BkXII:Chap4:Sec1

There are striking resemblances to The Minstrel in Lord Byron’s verse: at the time of my English exile, Lord Byron was not yet at Harrow School, in its village ten miles from London. He was a child, I was young and as unknown as he was: he had been raised among the Scottish heather, near the sea, as I was on the moors of Brittany, near the sea; he loved the Bible and Ossian, as I loved them; he sang the memories of childhood at Newstead Abbey as I sang them at the Château of Combourg.

‘When I rov’d a young Highlander o’er the dark heath,

And climb’d thy steep summit, oh Morven of snow!

To gaze on the torrent that thunder’d beneath,

Or the mist of the tempest that gather’d below.’

In my journeys around London, when I was so destitute, I passed through Harrow village a score of times, without realising what a genius it was destined to contain. I sat in the cemetery, at the foot of the elm on which, in 1807, Lord Byron wrote these lines, at the moment when I returned from Palestine:

‘Spot of my youth! whose hoary branches sigh,

Swept by the breeze that fans thy cloudless sky; .

Where now alone I muse, who oft have trod,

With those I loved, thy soft and verdant sod.

When fate shall chill, at length, this fevered breast,

And calm its cares and passions into rest.

(Where).here it lingered, here my heart might lie;

Here might I sleep, where all my hopes arose,

Blest by the tongues that charmed my youthful ear,

Mourned by the few my soul acknowledged here;

Deplored by those in early days allied,

And unremembered by the world beside.’

And I salute the ancient elm, at whose foot the young Byron gave himself to the caprices of youth, not long after I had dreamed of René in its shade, that same shade where later the Poet came to dream in turn of Childe Harold! Byron asked of that cemetery, witness of his first childhood games, an unknown grave: a vain prayer that fame denied him. However Byron’s name is no longer what it has been; staying in Venice I heard of him on all sides: after a few years, in that same city where I had found it everywhere, I found it effaced and everywhere unknown. The echoes of the Lido no longer repeat it, and if you ask the Venetians they no longer know of whom you are speaking. Lord Byron is long dead as far as they are concerned; they no longer hear the neighing of his horse: it is the same in London, where his memory has faded. That is what becomes of us.

‘George Gordon Byron’

The Works of Lord Byron, Comprehending the Suppressed Poems - George Gordon Byron (p8, 1822)

The British Library

If I had passed through Harrow without knowing that the young Lord Byron would breathe there, the English passed Combourg without suspecting that a little vagabond, climbing the trees, would leave any trace behind. The traveller Arthur Young, travelling through Combourg, wrote:

‘To Combourg, the country has a savage aspect; husbandry not much further advanced, at least in skill, than among the Hurons, which appears incredible amidst inclosures; the people almost as wild as their country, and their town of Combourg one of the most brutal filthy places that can be seen; mud houses, no windows, and a pavement so broken, as to impede all passengers, but ease none—yet here is a chateau, and inhabited; who is this Mons. de Chateaubriant, the owner, that has nerves strung for a residence amidst such filth and poverty? Below this hideous heap of wretchedness is a fine lake, surrounded by well wooded inclosures.’

This Mons. de Chateaubriant was my brother; the retreat which seemed so hideous to the ill-tempered agriculturalist, was none the less a fair and noble domain, though solemn and sombre. As for me, what if Mr Young had been able to see me there, a feeble ivy plant who began by climbing the foot of those savage towers, he who was only occupied with reviewing our harvest!

Allow me to add to these lines written in England in 1822, the following written in 1834 and 1840: they complete this fragment on Lord Byron; a fragment rounded off in particular by reading what I said about the great poet when passing through Venice.

There would perhaps have been some interest in the future in noting the meeting of two leaders of the new English and French schools, possessing the same fund of ideas, and destiny, though without much similarity in morals: one a peer of England, the other a peer of France, both travellers in the East, quite often not far apart, yet never meeting: only the life of the English poet was involved with less profound events than mine.

BkXII:Chap4:Sec2

Lord Byron visited the ruins of Greece after me: in Childe Harold it is as though he embellishes my descriptions in L’Itinéraire with his own colours. At the start of my pilgrimage, I reproduced the Sire de Joinville’s farewell to his castle; Byron says a similar farewell to his Gothic mansion.

In Les Martyrs, Eudore leaves Messenia to return to Rome: ‘Our voyage was a long one,’ he says ‘...we saw all those promontories marked by temples or tombs. My young companions had never heard tell of the metamorphoses of Jupiter, and they understood nothing of the remains before their eyes; I had already sat, like the prophet, among the ruins of desolate cities, and Babylon told me of Corinth.’

Childe Harold's Pilgrimage. Cantos I-IV - George Gordon Byron (p225, 1886)

The British Library

The English poet, as the French prose writer, follows the letter from Sulpicius to Cicero; - so perfect an agreement is singularly glorious for me, since I anticipated the immortal bard on that shore of which we have similar memories, and where we commemorated the same ruins.

I have the honour of also being in tune with Lord Byron in our descriptions of Rome: Les Martyrs and my Lettre sur la campagne romaine have the inestimable advantage, to me, of having prefigured the inspirations of a fine talent.

Lord Byron’s first translators, commentators and admirers were careful not to comment on the fact that several pages from my works may have stayed for a moment in the memory of the creator of Childe Harold; they would have considered that it took something from his genius. Now that the enthusiasm has abated a little, they are less prone to deny me that honour. Our immortal singer, in the last volume of his Chansons, has said: ‘In one of the verses preceding this, I spoke of the lyricists that France owes to Monsieur de Chateaubriand. I have no fears that this verse will be refuted by the new poetic school, which, born beneath the eagle’s wings, has with reason, often boasted of such an origin. The influence of the author of Le Génie du Christianisme has equally made itself felt abroad, and it would perhaps be just to recognise that the bard of Childe Harold is of the family of René.’

In an excellent article on Lord Byron, Monsieur Villemain repeated Monsieur de Béranger’s remark: ‘Several incomparable pages of René,’ he said, ‘have, in truth, fully exploited this poetic character. I do not know if Byron imitated them or recreated them out of his genius.’

What I may chance to say of the affinities of imagination and destiny between the chronicler of René and the poet of Childe Harold plucks not a single hair from the head of the immortal bard. What could my Muse, pedestrian and without a lute, take from the Muse of the Dee, with wings and lyre? Lord Byron will live, regardless of whether as a child of his age like me, he has, like me and like Goethe before us, expressed its passion and tragedy; or whether my journey and the lantern of my French barque revealed a course to the English vessel through uncharted waters.

Moreover, two spirits analogous in nature may very easily conceive of like things, without bearing the reproach of having followed the same path in a servile manner. It is permissible to profit from ideas and images expressed in a foreign language, to enrich one’s own: that has been observed in all ages and all times. I am the first to admit that in early youth, Ossian, Werther, Les Rêveries du promeneur solitaires, and Les Études de la nature, may well have contained ideas similar to mine; but I have hidden nothing, concealed nothing of the pleasure the works I delighted in gave me.

If it were true that René counted for something in the composition of unique characters presented under various names in Childe Harold, the Corsair, Lara, Manfred, and The Giaour; or if, by chance, Lord Byron had nourished my life with his, would he have been so weak as never to mention me? Was I then one of those contemporaries one disowns on achieving power? Could Lord Byron have been totally ignorant of me, he who cites almost all the French authors who were his contemporaries? Had he never heard tell of me, when the English journals, as the French ones, have echoed twenty years after his death with controversy over my work, when the New Times has drawn a parallel between the author of Le Génie du Christianisme and the author of Childe Harold?

There is no mind, however blessed, that fails to possess its sensitivities, its mistrust: one guards the sceptre, one fears to share it, one is irritated by comparison. So, another superior talent omitted my name in her work De la littèrature. Thank goodness that, valuing myself at my true worth, I have never pretended to an empire; since I only believe in religious truth of which freedom is an aspect, I have no more faith in myself than in anything else below. But I have never felt the need to be silent about what I admire; that is why I proclaim my enthusiasm for Madame de Staël and Lord Byron. What is sweeter than admiration? It derives from heavenly love, from tenderness elevated towards worship; one feels oneself penetrated by gratitude for the divinity that extends the roots of our faculties, opens new vistas to the soul, grants us a happiness that is great, and pure, without fear or envy.

In addition, the little quibble I make in these Memoirs, over the greatest poet England has produced since Milton, only proves one thing: the high value I would have attached to being remembered by his muse.

Lord Byron has founded a deplorable school: I presume that he has been as sorry for giving birth to those Childe Harolds, as I am of the Renés who daydream around me.

BkXII:Chap4:Sec3

Lord Byron’s life is the subject of many analyses and slanders: young men have taken his magical words too seriously; women have felt disposed to allow themselves to be seduced, fearfully, by that monster, in order to solace this solitary and unfortunate Satan. Who knows? Perhaps he has not met the woman he sought, a woman beautiful enough, a heart as vast as his own. Byron, according to fantastical opinion, is the ancient serpent, a seducer and a corrupter, since he sees the corruption of the human species; he is a fatal and suffering genius, situated between the mysteries of mind and matter, who sees no point in speaking of the enigma of the universe, who regards life as a dreadful irony without cause, like a perverse evil smile; he is the child of despair, who scorns and renounces, who bearing within himself an incurable wound, revenges himself by leading all whom he meets, through pleasure, to grief. He is a man who has never passed through an age of innocence, who has never had the advantage of being rejected and cursed by God; a man who, emerging as an outcast from nature’s breast, is condemned to nothingness.

Such is the Byron of the fevered imagination: it bears no relation it seems to me to the reality.

As with most men, two different men are united in Lord Byron: the natural man and the social man. The poet, recognising the role which the public wished him to play, accepted it and set himself to curse the world that at first he had merely daydreamed about: that progress is perceptible in the chronological order of his works.

As for his genius, far from having extended what was attributed to him, he has grown much narrower; his poetic thought is no more than a moan, a complaint, an imprecation; in that vein, however, it is admirable: one ought not to ask of his lyricism what it thinks, only what it sings.

As for his wit, he is sarcastic and various, but in a manner that perturbs and with a disastrous influence: the writer has read Voltaire deeply, and he imitates him.

Lord Byron, endowed with all the advantages, has little to complain of concerning his origins; the same accident of birth that made him wretched, and which saddled his superior powers with human infirmity, ought not to have tormented him, since it has not prevented him being loved. The immortal poet knows for himself the truth of Zeno’s maxim: ‘The voice is the flower of beauty.’

One deplorable thing is the speed with which reputations flee these days. After a few years, what say I, after a few months, the craze vanishes; the denigration follows. Lord Byron’s fame is already fading; his genius is better understood among us; the altars to him will burn longer in France than in England. Since Childe Harold excels principally in expressing particularly individualistic feelings, the English, who prefer feelings common to all, will end by lacking awareness of the poet whose cry is so melancholy and profound. Let them take care: if they shatter the image of the man who has given them new life, what will be left them?

While I was writing, in 1822, during my London stay, these sentiments with regard to Lord Byron, he had only two years to live: he died in 1824, at the moment when disenchantment and disgust had begun to assail him. I preceded him into life; he has preceded me into death; he has been called before his time; my number was ahead of his, and yet he has departed first. Childe Harold has been forced to rest; the world could lose me without noticing my disappearance. I have met, in continuing my journey, Madame Guiccioli in Rome, and Lady Byron in Paris. Frailty and virtue were thus apparent to me: the former perhaps is too concerned with realities the latter has too few dreams.

Book XII: Chapter 5: England from Richmond to Greenwich – A trip with Peltier – Blenheim – Stowe – Hampton Court – Oxford – Eton College – Private life; political life – Fox – Pitt – Burke – George III

London, April to September 1822.

BkXII:Chap5:Sec1

Now, after having spoken to you of English writers at the time when England served as my refuge, it only remains for me to say something of England itself at that period, its appearance, famous places, stately homes, and its private and political manners.

All of England can perhaps be appreciated in the space of twenty two miles, between Richmond, above London, and Greenwich below it.

Below London, lies industrial and commercial England, with its docks, warehouses, customs houses, arsenals, breweries, factories, foundries, and ships; the latter, at each tide, sail up the Thames in three groups, the smallest first, the middle-sized next, and lastly, the large vessels which shave with their sails the columns of the Royal Hospital and the windows of the tavern where visitors dine.

Above London, is agricultural and pastoral England with meadows, herds, country houses, and parks, whose lawns and shrubs the waters of the Thames, driven back by the rising tide, bathe twice a day. Between these two opposite points of Richmond and Greenwich, London merges together all of this double England: to the west aristocracy, to the east democracy, the Tower of London and Westminster, the boundaries between which the entire history of Great Britain has been enacted.

I spent part of the summer of 1799 at Richmond with Christian de Lamoignon, occupying myself with the Génie du Christianisme. I took boat trips on the Thames, or turns in Richmond Park. I would dearly have liked the London Richmond to be the Richmond of the treaty Honor Richemundiae, since then I would have found myself at home, and here is the reason: William the Bastard presented Alain, Duke de Bretagne, his son-in-law, with four hundred and forty-two areas of manorial land in England, which from then on formed the County of Richmond (see the Domesday Book): the Dukes of Brittany, Alain’s successors enfeoffed these domains to Breton knights, cadet branches of the families of Rohan, Tinteniac, Chateaubriand, Goyon, and Montboucher. But despite my dearest wish I would have needed to seek in Yorkshire for that County of Richmond made into a Duchy under Charles II for his bastard son: Richmond on Thames is the ancient Shene of Edward III.

There Edward III died in 1377, that famous king robbed by Alice Perrers, his mistress, no longer the Alice or Catherine of Salisbury of the early days of the victor of Crécy’s life: do not love except at an age when you can be loved. Henry VII and Elizabeth also died at Richmond: where can one not die? Henry VIII enjoyed it as a place of residence. English historians are deeply embarrassed by this abominable human being; on the one hand they cannot hide his tyranny and Parliament’s subservience; on the other, if they speak out too much against the leader of the Reformation, they condemn themselves in condemning him:

‘The viler the oppressor, the more the slave is vile.’

In Richmond Park they show you the hillock that served Henry VIII as an observation post while watching for the sign of Anne Boleyn’s execution. Henry shivered with pleasure at the signal-rocket fired from the Tower of London. What delight! The axe had severed that delicate neck, bloodying the lovely hair in which the poet-king had twined his fatal caresses.

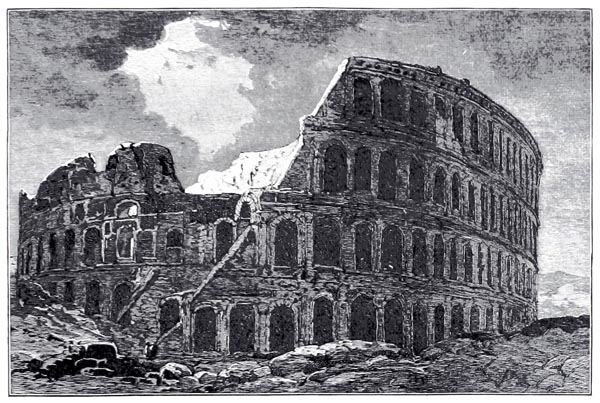

‘View from Richmond Hill’

Historical Richmond - Edwin Beresford Chancellor (p205, 1885)

The British Library

In a deserted Richmond Park, I did not await a signal indicating murder: I would not have wished even the smallest ill on anyone who might betray me. I walked there among a few peaceable deer: accustomed to run before a pack of hounds, they stopped when they were tired; they were brought back, very happy and quite content from this sport, in a cart filled with straw. I would go to see the kangaroos at Kew, ridiculous creatures, precisely the opposite of giraffes: those innocent quadrupeds stocked Australia more fittingly than the old Duke of Queensbury’s whores did the alleys of Richmond. The Thames bordered the lawn of a cottage half-hidden beneath a cedar of Lebanon, among weeping willows: a newly married couple had arrived to spend their honeymoon in this paradise.

Now, as I was walking quietly one evening on the lawns of Twickenham, Peltier appeared, holding his handkerchief to his mouth: ‘What an eternal cloud of fog!’ he cried as soon as he was capable of speaking. ‘How the devil can you stay here? I have made a list: Stowe, Blenheim, Hampton Court, Oxford; with your dreamy way of going on, you will be here with John Bull in vitam aeternam, and see nothing.’

I asked to be spared, in vain, I had to go. In the carriage, Peltier recounted his hopes to me; he employed relays; one dying under him, he would bestride another, and so on, leg by leg, to the end of his days. One of his hopes, the most solid, led him in the end to Napoleon whom he took by the throat: Napoleon had the foolishness to cross swords with him. Peltier had James Mackintosh as his defence lawyer; condemned by the Court, he made a fresh fortune (which he consumed incontinently) in selling the narrative of his trial.

Blenheim was disagreeable to me: I suffered all the more over my country’s historic defeat, in that I had been forced to endure the insult of a recent affront: a boat upstream on the Thames spotted me on the shore; the rowers aware of a Frenchman began jeering; they had just heard the news of the naval action at Aboukir Bay: this foreign victory which might open the gates of France again, was nevertheless odious to me. Nelson, whom I had seen several times in Hyde Park, followed up his victories at Naples dressed in Lady Hamilton’s shawl, while the lazzaroni (the homeless idlers of Naples) played at bowls with heads. The admiral died gloriously at Trafalgar, and his mistress miserably at Calais, having lost beauty, youth and fortune. And I whom the triumph at Aboukir offended so greatly on the banks on the Thames, I have seen the palm trees of Libya lining the shore of a sea calm and empty which was once reddened by the blood of my countrymen.

The park at Stowe is famous for its ornamental structures: I liked its shade more. The guide to the place showed us, in a dark valley, a copy of a temple whose model I would admire in the gleaming Valley of Cephisus. Fine paintings of the Italian School grieved in the depths of a few inhabited rooms, whose shutters were closed: poor Raphael imprisoned in a mansion of the ancient Britons, far from the heaven of the Farnesina!

Hampton Court retained its collection of portraits of Charles II’ mistresses: that’s how this Prince conducted himself after escaping a Revolution that saw his father’s head fall and which was forced to drive out his race.

‘View of the Palace from Moulsey’

The Stranger's Guide to Hampton Court Palace - John Grundy (p43, 1848)

The British Library

We arrived at Slough, Herschel and his learned sister, and his great forty-foot telescope; he sought new planets: that made Peltier laugh who held fast to the seven ancient ones.

We stayed for two days in Oxford. I enjoyed being in that republic founded by Alfred the Great; it represented the privileged freedoms and manners of the literary institutions of the Middle Age. We explored the twenty colleges in depth, the libraries, the paintings, the museum, the botanical garden. Amongst the manuscript collection of Worcester College, I leafed through a life of the Black Prince, written in French verse by the Prince’s Herald at Arms, with great delight.

Oxford, without resembling them, brought to mind the modest colleges of Dol, Rennes and Dinan. I had translated Gray’s Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard.

‘The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,’

- an imitation of these lines from Dante:

‘...squilla di lontano,

Che paia il giorno pianger che si more.’

Peltier hastened to publish my translation, to the sound of trumpets, in his journal. At the sight of Oxford, I recalled the same poets Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College.

‘Ah, happy hills, ah, pleasing shade,

Ah, fields beloved in vain,

Where once my careless childhood strayed,

A stranger yet to pain!

I feel the gales, that from ye blow,

A momentary bliss bestow,

As waving fresh their gladsome wing,

My weary soul they seem to soothe,

And, redolent of joy and youth,

To breathe a second spring.

Say, Father Thames..

What idle progeny succeed

To chase the rolling circle’s speed,

Or urge the flying ball?....

Alas, regardless of their doom,

The little victims play!

No sense have they of ills to come,

Nor care beyond today.’

Who has not experienced the feelings and regrets expressed here with all the sweetness of the Muse? Who has not been moved at memories of the games, studies, loves of former years? But can one bring them back to life? The delights of youth reproduced in memory are ruins seen by torchlight.

‘Balliol and Trinity Colleges’

The Perambulation of Oxford, Blenheim, and Nuneham - Giulio-Romano Pippi (p130, 1824)

The British Library

BkXII:Chap5:Sec2

The Private Life Of The English

Divorced from the Continent by a long war, the English, at the end of the last century, retained their national character and way of life. They were still one people, in whose name power was exercised by an aristocratic government; there were but two great classes friendly towards each other and bound by a common interest, the patrons and their dependants. That jealous class, called the bourgeoisie in France, which is beginning to appear in England, did not yet exist: nothing stood between the rich landowners and men occupied with their trade. Everything had not yet become the machinery of professional manufacture, the follies of the privileged order. On the same pavements where one now sees grimy faces and men in frock-coats, little girls in white cloaks passed by, their straw hats fastened under the chin with a ribbon, a basket containing fruit or books on their arm; all kept their eyes lowered, all blushed when one looked at them. Britain, says Shakespeare, is: ‘in a great pool a swan’s nest.’ Frock-coats without a jacket beneath were so unusual in London in 1793 that a woman, weeping bitterly over the death of Louis XVI, said to me: ‘But, my dear sir is it true that the poor King was dressed in a frock-coat when they cut off his head?’

The gentleman farmers had not yet sold their patrimony in order to live in London; in the House of Commons they still formed that independent faction which, supporting now the opposition now the government, maintained the ideals of liberty, order and propriety. They hunted foxes and shot pheasants in the autumn, ate fatted geese at Christmas, shouted vivat at roast beef, grumbled about the present, praised the past, cursed Pitt and the war, because it raised the price of port, and went to bed drunk to recommence the same life the next day. They were convinced that the glory of Great Britain would never fade as long as they sang God save the King, rotten boroughs were maintained, the game laws kept in force, and as long as they secretly sent hares and partridges to market under the titles of lions and ostriches.

The Anglican clergy was learned, hospitable and generous; it had welcomed the French clergy with truly Christian charity. Oxford University, at its own expense printed, and distributed freely among the curés, a New Testament according to the Latin Vulgate, with the imprint: in usum cleri gallicani in Anglia exulantis. As for English high society, as a poor exile I only saw it from the outside. When there was a reception at Court or at the Princess of Wales’, ladies went by in sedan chairs sitting sideways; their great hoop-petticoats emerged from the door like altar hangings. They themselves, set on those waist-high altars, looked like madonnas or pagodas. Those fine ladies were the daughters whose mothers the Duc de Guiche and the Duc de Lauzun had once admired; those daughters are, in 1822, the mothers and grandmothers of the little girls who dance at my residence in short frocks to the music of Collinet’s flute, a passing generation of flowers.

BkXII:Chap5:Sec3

Political Life

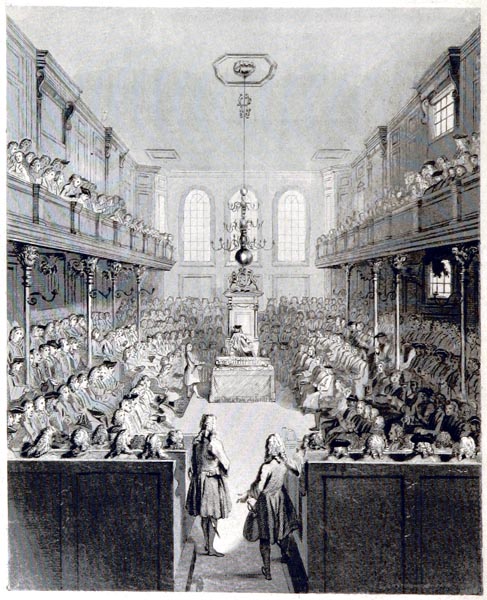

England in 1688, at the close of the last century, was at the peak of its glory. A poor émigré in London, from 1792 to 1800, I heard speeches by Pitt, Fox, Sheridan, Wilberforce, Grenville, Whitbread, Lauderdale and Erskine; today in 1822, as Ambassador to London in all my magnificence, I am not sure how it strikes me, since, instead of the great orators I admired previously, I see those rise to speak who were their followers at the time of my first visit, students in place of the masters. Common ideas have penetrated that individualistic society. But the enlightened aristocracy, placed in charge of the country for a hundred and forty years, will have displayed to the world one of the finest and greatest social orders which has done honour to the human species since the Roman Patriciate. Perhaps, some old family, in the depths of the country, will recognize the society I happen to describe, and will regret the passing of those times whose loss I here deplore.

‘Interior of the House of Commons in 1690’

History of the House of Commons, from the Convention Parliament of 1688-9 to the passing of the Reform Bill, in 1832 - William Charles Townsend (p10, 1843)

The British Library

In 1792, Mr Burke split from Mr Fox. The breach concerned the French Revolution which Mr Burke attacked, and Mr Fox supported. Never had the two orators, who until then had been friends, deployed such eloquence. The whole Chamber was moved, and tears filled Mr Fox’s eyes, when Mr Burke ended his reply with these words: ‘The Right Honourable gentleman, in the speech he has made, has treated me in every phrase with uncommon harshness; he has censured my entire life, my conduct and my opinions. Notwithstanding this great and serious attack, unmerited on my part, I will not be intimidated; I do not fear to declare my sentiments in this Chamber nor anywhere else. I say to the whole world that the Constitution is in peril. It is indiscreet at any period, but especially at my time of life, to provoke enemies, or give my friends occasion to desert me. Yet if my firm and steady adherence to the British Constitution place me in such a dilemma, I am ready to risk it, and, as public need and public prudence demand, with, my last words to exclaim: “Fly from the French Constitution!”’

Mr Fox having said that it was not a question of loss of friends, Mr Burke cried: ‘Yes, there is a loss of friends! I know the price of my conduct. I have done my duty at the price of my friend. Our friendship is at an end. I warn the Right Honourable gentlemen, who are the greatest rivals in this Chamber, that they must in future (whether they move in the political hemisphere like two great meteors, or whether they march together like brothers), I warn them that they must cherish and preserve the British Constitution, that they must guard it against innovation and save it from the danger of these new theories.’ A memorable age of the world.

Mr Burke, whom I met at the end of his life, overwhelmed by the death of his only son, founded a school dedicated to the children of impoverished émigrés. I went to see what he called his nursery. He was delighted with the liveliness of this foreign race that passed beneath his paternal genius. Watching the little exiles leaping heedlessly, he said to me: ‘Our boys could not do that’ and his eyes filled with tears: he was thinking of his son who had gone to a longer exile.

Pitt, Fox, Burke are no more, and the English Constitution has suddenly acquired the influence of those new theories. One has to have listened to the seriousness of the parliamentary debates of that era, to have heard those orators whose prophetic voices seemed to announce an imminent revolution, to gain an idea of the scene that I recall. Liberty, contained within the limits of order, seemed at Westminster to struggle against the influence of anarchic liberty, which spoke to the gallery still bloody from the Convention.

Mr Pitt, tall and thin, had a mournful mocking air. His speech was cold, his delivery monotonous, and his gestures lifeless; yet, the lucidity and fluency of his thought, the logic of his reasoning, suddenly illumined by flashes of eloquence, rendered his talents something out of the ordinary.

I saw Mr Pitt quite frequently, as he crossed Saint James’s Park on foot from his residence to visit the king. George III, for his part, would arrive from Windsor, having drunk beer from a pewter pot with the neighbouring farmers; he would cross the ugly courtyards of his ugly citadel, in a grey carriage followed by several Horse Guards; he was the master of the kings of Europe, as five or six City merchants are the masters of India. Mr Pitt, dressed in black, a sword with a steel hilt at his side, his hat under his arm, climbed in taking two or three of the steps at a time. On his journey he only met with three or four idle émigrés: casting a disdainful glance towards us, he passed by, nose in air, pale of face.

That great financier kept no order at home; no fixed hours for meals or sleep. Crippled with debt, he paid nothing, and could not bear to commit the sum to paper. A valet ran his house. Badly dressed, without pleasures, or passions, only eager for power, he despised honours, and wished to be no more than William Pitt.

Lord Liverpool, in the month of June of this year 1822, took me to dine at his country house: crossing Putney Heath, he showed me the little house where the son of Lord Chatham died in debt, the statesman who had had Europe in his pay and distributed all the earth’s billions with his own hands.

George III survived Mr Pitt, but lost his reason and his sight. Each session, at the opening of Parliament, the Ministers read quietly in their chambers awaiting the bulletin regarding the king’s health. One day, I went to visit Windsor: for a few shillings I obtained the good will of a doorman who concealed me so as to see the king. The monarch, blind and white-haired, appeared, like King Lear, wandering his palace, groping his way along the walls. He sat down at a piano whose location he was familiar with, and played several bars of a sonata by Handel: a fine end to Old England!

Book XII: Chapter 6: The Émigrés return to France – The Prussian Minister grants me a false passport under the name of Lassagne, a resident of Neuchâtel, in Switzerland – The end of my career as a soldier and traveller – I land at Calais

London, April to September 1822.

BkXII:Chap6:Sec1

I began to turn my eyes towards my native land. A great Revolution had occurred. Bonaparte, having become First Consul, was re-establishing order by despotism; many exiles were returning; the noble émigrés, in particular, were hurrying to gather in the remainder of their wealth: loyalty faded at the head, while its heart still beat in the breasts of a few half-clothed provincial gentlemen. Mrs Lindsay had departed; she wrote to Auguste and Christian de Lamoignon telling them to return; she also extended an invitation to Madame d’Aguesseau, their sister, to cross to France. Fontanes summoned me, to complete the printing of Le Génie du Christianisme in Paris. Though full of memories of my country, I felt no desire to see it again; gods more powerful than the paternal Lares held me back; I no longer had possessions or sanctuary in France; my motherland had become a bosom of stone to me, a breast without milk: I would not find my mother, brother or sister Julie there. Lucile was still alive, but she had married Monsieur de Caud, and no longer bore my name; my young widow had known me through a union of only a few months, through misfortune and an eight-year absence.

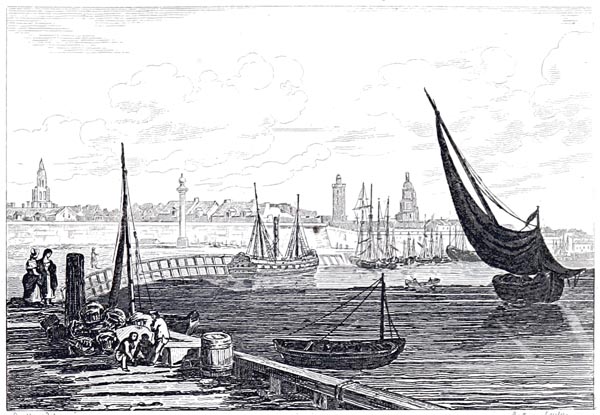

Left to myself, I do not know if I would have had the strength to leave; but I saw my small circle breaking up; Madame d’Aguesseau offered to take me to Paris: I allowed myself to go. The Prussian Minister procured a passport for me, under the name of Lassagne, a resident of Neuchâtel; Dulau and Co ceased printing Le Génie du Christianisme, and gave me the sheets that had been composed. I separated the sketches of Atala and René from Les Natchez; I placed the rest of the manuscript in a trunk and entrusted its transit to my hosts in London, and I set out en route for Dover with Madame d’Aguesseau: Madame Lindsay waited for us at Calais.

Thus I left England in 1800; my heart was otherwise engaged than it is at the time of writing, in 1822. I brought nothing back from the land of exile but regrets and dreams; today, my head is full of displays of ambition, politics, and Court splendours, so ill-suited to my nature. What events pile up in my present existence! Go on, gentlemen, go on; my turn will come. I have merely unrolled a third of my life before your eyes; if the trials I endured weighed on my springtime serenity, now, entering a more fruitful time, the germ of René will develop, though bitterness of a different kind will be blended with my narrative! What will I not have to tell you, in speaking of my country, of her revolutions, of which I have already shown you the initial outline; of that Empire and the colossus whose fall I saw; of that Restoration in which I played so large a part, glorious as it is today in 1822, but which nevertheless I see only through a kind of fateful mist?

Here, I end this twelfth book, which has brought me to the spring of 1800. Arriving at the end of my first career, the career of a writer opens before me; from a private man I am about to become a public man; I am leaving the silent virginal sanctuary of solitude to enter the noisy, dusty cross-roads of the world; broad daylight will illuminate my life of dreams, light will penetrate the kingdom of shadows. I cast a tender glance over these books which enclose my unremembered hours; I seem to be saying a last goodbye to my paternal home; I take leave of the thoughts and chimeras of my youth as of sisters, as of sweethearts I am leaving by the family hearth, never to see them again.

We took four hours to cross from Dover to Calais. I slipped into my country protected by a foreign name: doubly hidden beneath the obscurity of the Swiss, Lassagne, and my own, I entered France with the century.

Revised December 1846

‘Calais’

France Pittoresque...des Départements et Colonies de la France, Vol 02 - Jean Abel Hugo (p645, 1838)

The British Library

End of Book XII