François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XIII: Literary Fame 1800-1803

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XIII: Chapter 1: My stay in Dieppe – Two societies

- Book XIII: Chapter 2: The stage my Memoirs have reached

- Book XIII: Chapter 3: The year 1800 – The scene in France – I arrive in Paris

- Book XIII: Chapter 4: The year 1800 – My life in Paris

- Book XIII: Chapter 5: A change in society

- Book XIII: Chapter 6: My life in 1801 – Le Mercure - Atala

- Book XIII: Chapter 7: The year 1801 – Madame de Beaumont: her set

- Book XIII: Chapter 8: The year 1801 – Summer at Savigny

- Book XIII: Chapter 9: The year 1802 – Talma

- Book XIII: Chapter 10: The years 1802 and 1803 – Le Génie du Christianisme – Disaster predicted – The reason for ultimate success

- Book XIII: Chapter 11: Le Génie du Christianisme, continued – The faults of the work

Book XIII: Chapter 1: My stay in Dieppe – Two societies

Dieppe, 1836 (Revised in December 1846)

BkXIII:Chap1:Sec1

You know that I have changed my place of residence many times during the writing of these Memoirs; that I often describe these places, having spoken of the feelings they inspired in me, and retrace my memories, so as to merge the history of my thoughts and my various homes with the story of my life.

You will discover where I am now. Walking this morning on the cliffs, behind Dieppe castle, I noticed the postern which communicates with the cliffs by means of a bridge flung over a moat: Madame de Longueville fled across it to reach Queen Anne of Austria; taking ship at Le Havre, landing at Rotterdam, she returned to Stenay, and the Marshal de Turenne. The great captain’s laurels were no longer unstained, and she, the scornful exile, no longer treated the guilty party with much consideration.

Madame de Longueville, who enhanced the Hotel Rambouillet, the throne of Versailles, and the municipality of Paris, acquired a passion for the author of the Maxims, and was faithful to him for as long as she could be. He in turn thought less of his pensées than of his friendship with Madame de La Fayette and Madame de Sévigné, the verse of La Fontaine and the love of Madame de Longueville: such is the power of illustrious attachments.

The Princesse de Condé, near to death, said to Madame de Brienne: ‘My dear friend, tell that poor wretch, at Stenay, the state you see me in, and to learn how to die.’ Fine words; but the Princess forgot that she herself had been loved by Henri IV, and that escorted from Brussels by her husband she had wished to rejoin the Béarnais, to escape at night, through the window, and then ride twenty or thirty leagues on horseback; she was then a poor wretch of seventeen.

Descending the cliffs, I found myself on the main Paris road; it climbed quickly on leaving Dieppe. On the right, on the ascending line of a bank, a cemetery wall rose; alongside this wall was fixed a wheel for winding rope. Two rope-makers, walking backwards in parallel and putting their weight on each leg in turn, sang together quietly. I listened; they had reached these lines of Le Vieux Caporal: that fine poetic falsity, which has brought us where we are.

‘Who is gazing and weeping there?

Ah! It’s the drummer’s widow,’ etc.

The men sang the refrain: Conscripts, fall in; don’t weep.march in step, in step.in so sad and manly a tone that tears sprang to my eyes. In marking the steps themselves, while winding the hemp, they looked as though they were shadowing the last movements of the old lance-corporal: I would not have been able to say what part of this fineness, revealed solely by two sailors in sight of the sea singing the death of a soldier, was due to Béranger.

The cliff had called up for me monarchist grandeur, the road plebeian celebrity; I compared in my mind people at either extreme of society; I asked myself to which of those two eras I would have preferred to belong. When the present has disappeared like the past, which of those two names will most attract the gaze of posterity?

Moreover, if facts are everything, if, in history, the value of a name does not outweigh the value of an event, what is the difference between my times and the times which unrolled from the death of Henri IV to that of Mazarin! What are the troubles of 1648 compared to that Revolution, which has consumed the previous world, of which perhaps it will die, by leaving neither an old nor a new society behind it? Have I not depicted in my Memoirs scenes of vastly greater importance than those revealed by the Duc de Rochefoucauld? Even at Dieppe, what is that cool and voluptuous idol of Paris, seductive and rebellious, beside Madame la Duchesse de Berry? The cannon fire that announced the royal widow’s presence here, no longer sounds; the tribute of smoke and powder has left nothing behind on the shore but the moaning of the waves.

Those two Bourbon daughters, Anne-Geneviève and Marie-Caroline, are gone; the two sailors and the song of the plebeian poet are engulfed; Dieppe is emptied of me; it was another I, an I of my lost early years, who once lived in these places, and that I is dead, since our days die before us. Here you have seen a second-lieutenant in the Navarre Regiment, exercising recruits on the shingle; you have seen me exiled under Bonaparte; you will meet me when July days find me here once more. Here I am still; I take up my pen again to continue my Confessions.

In order to recognise where we are up to, it is useful to cast a glance at the progress of my Memoirs.

Book XIII: Chapter 2: The stage my Memoirs have reached

BkXIII:Chap2:Sec1

What has happened with me is what happens with all who undertake a work on a grand scale: I have, first of all, set up a flag at both ends then, planting and replanting my scaffolding here and there, I have raised the stones and cement of intervening constructions; it takes several centuries to create a Gothic cathedral. If Heaven allows me to live, the monument will be completed throughout my life, the architect, ever the same, will only vary in his age. For the rest, it is painful to keep the intellectual self intact, imprisoned in a worn material envelope. Saint Augustine feeling his body weakening, said to God: ‘Be the tabernacle of my soul’; and he said to men: ‘When you find me in this book..pray for me.’

Thirty-six years have elapsed between the events which formed the first part of my Memoirs, and those which I am involved in today. How to recommence with ardour the narration of subjects one filled for me with passion and warmth, when the people are no longer alive with whom I can discuss them, when it is a question of waking frozen effigies from the depths of Eternity, of descending into a burial vault to play at life there? Am I not myself already half-dead? Have not my opinions altered? Can I see things from the same viewpoint? Those personal events which so troubled me, the prodigious public events which accompanied or followed them, have they not diminished in importance in the world’s eyes, as in my own? Whoever has a long life feels his days grow colder; he finds that tomorrow no longer bears the interest it did of old. When I search my thoughts, there are names, and people almost, who escape my memory, however much they may have made my heart beat: the vanity of man, forgetting and forgotten! It is not enough to say to our dreams, our loves: ‘Renew!’ for them to do so; one cannot enter the realm of shadows without the golden bough, and it needs a young man’s strength to pluck it.

Book XIII: Chapter 3: The year 1800 – The scene in France – I arrive in Paris

Dieppe, 1836

BkXIII:Chap3:Sec1

Someone, of the ancestral house, is here. (Rabelais)

For eight years, exiled in Great Britain, I had seen only an English world, so different, particularly then, to the rest of the European world.

As the Dover packet neared Calais, in the spring of 1800, my gaze was on shore before me. I was struck by the impoverished air of my country: hardly any masts rose from the harbour; a crowd in short jackets (en carmagnole) and cotton caps strode in front of us along the jetty: the conquerors of a continent were announced to me by the sound of clogs. When we drew alongside the pier, the police and customs men leaped onto the bridge, to check our luggage and passports: in France, a man is always suspect, and the first thing one is aware of in public matters, as in our pleasures, is a three cornered hat or a bayonet.

Mrs Lindsay was waiting for us at the inn; next day we left for Paris with her: Madame Aguesseau, a young relative of hers, and I.

On the road, one saw hardly any men; women bronzed and blackened, worked the fields, their feet naked, their heads bare, or covered by a handkerchief: one would have taken them for slaves. I was bound to be somewhat amazed by the independence and vigour of this land where women handled the hoe while men handled the musket. One would have said that a fire had passed through the villages; they were in a wretched state and half-demolished: all was dust and mud, smoke and debris.

To right and left of the road, ruined country houses appeared; of their razed plantations, only a few felled trunks remained, on which children played. One could see shattered boundary walls, abandoned churches, from which the dead had been driven, bell-towers without bells, cemeteries without crosses, headless saints stoned in their niches. Daubed on the walls, and already old, was the Republican inscription: LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY OR DEATH. Sometimes there had been an attempt to erase the word DEATH, but the red or black letters still appeared under a layer of whitewash. The nation, which seemed on the point of dissolution, was entering a new world, like those peoples fleeing the darkness of barbarity and destruction in the Middle Ages.

Approaching the capital, between Écouen and Paris, the elms had not been cut down; I was struck by those beautiful tree-lined avenues, unknown on English soil. France was as new to me as once the forests of America had been. Saint-Denis was exposed, its windows shattered; rain penetrated its grassy naves, and there were no longer any tombs; I have since seen the bones of Louis XVI there, the Cossacks, the Duc de Berry’s coffin, and the catafalque of Louis XVIII.

Auguste de Lamoignon came to meet Mrs Lindsay: his elegant carriage contrasted with the heavy carts, and dirty stagecoaches, dilapidated and drawn by broken-down nags hitched to them with ropes, that I had encountered since Calais. Mrs Lindsay lived at Ternes. They set me down in the Chemin de la Revolté and I crossed the fields to reach my hostess’s home. I stayed at her house for twenty-four hours; there I met a certain tall fat Monsieur Lasalle who arranged émigré matters for her. She warned Monsieur de Fontanes of my arrival; at the end of forty-eight hours, he came to find me in the depths of a little room which Mrs Lindsay had rented for me in an inn almost at her door.

It was a Sunday: towards three in the afternoon, we entered Paris on foot through the Barrière de l’Étoile. We have no idea today of the impression that the excesses of the Revolution made on the minds of Europe, and principally among men absent from France during the Terror; it seemed to me, that I was literally landing in Hell. I had been witness, it is true, to the start of the Revolution; but the greatest crimes had not then been committed, and I was bowed down by subsequent events, such of them as were recounted in a peaceful and well-ordered English society.

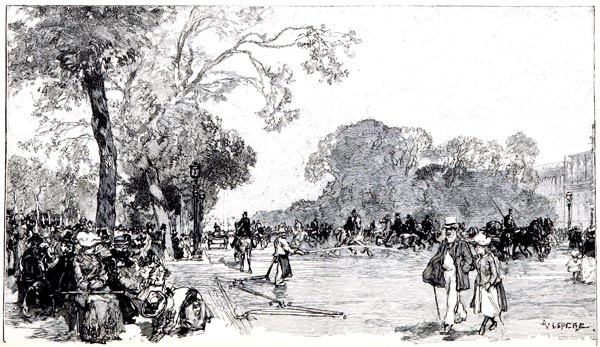

Appearing under a false name, and convinced that I was compromising my friend Fontanes, on entering the Champs-Elysées I was amazed to hear the sounds of violins, horns, clarinets and drums. I saw dance-halls where men and women were dancing; further on, the Tuileries palace appeared at the far end of its two great stands of chestnut trees. As for the Place Louis XV, it was bare; it had the ruined look, melancholy and deserted, of an ancient amphitheatre; I passed it swiftly; I was quite surprised not to hear any groans; I was fearful of putting my foot in a pool of blood of which there was not a trace; my eyes were drawn to that corner of sky where the instrument of death had towered; I thought I could see my brother and sister-in-law in their shifts lying beneath the blood-drenched machine: there Louis XVI’s head fell. Despite the joyful streets, the church towers were silent; it felt as though I was returning on that day of immense grief, Good Friday.

‘The Champs Elysées’

The Praise of Paris - Theodore Child (p73, 1893)

The British Library

BkXIII:Chap3:Sec2

Monsieur de Fontanes lived in the Rue Saint-Honoré, near Saint-Roch. He led me to his house, presented me to his wife, and then conducted me to the house of a friend, Monsieur Joubert, where I found temporary shelter: I was received like a traveller of whom word had been given.

Next day I went to the prefecture, and under the name of Lassagne handed over my foreign passport, receiving in exchange, to cover my stay in Paris, a permit renewable from month to month. After a few days, I rented a mezzanine in the Rue de Lille, near the Rue Saints-Pères.

I had brought with me the manuscript of Le Génie de Christianisme and the first pages of that work, printed in London. I was sent to Monsieur Migneret, a worthy man, who agreed to re-commence the interrupted printing and to forward me an advance to live on. Not a soul knew of my Essai sur les Révolutions, despite what Monsieur Lemierre had told me. I dug out the old philosopher Deslisle de Sales, who was about to publish his Mémoire en faveur de Dieu, and I returned to Ginguené’s house. He was lodged in the Rue de Grenelle-Saint-Germain, near the Hôtel du Bon La Fontaine. On the concierge’s lodge was a sign: Here we respect the title of citizen, and address each other as tu. Keep the door closed, please. I went up: Monsieur Ginguené, who scarcely recognised me, spoke to me from the heights of grandeur of all that he was and had been. I retired humbly, and did not attempt to renew so incompatible a relationship.

Always, in the depths of my heart, I nourished regrets for, and memories of, England; I had lived in that country for so long that I had grown accustomed to it: I could not get used to the filthiness of our houses, and our stairs, our dirtiness, our noise, our familiarity, our indiscreet gossip: I was English in manners, taste, and, up to a point, in thought; for if, as is claimed, Lord Byron was sometimes inspired by René while writing Childe Harold, it is also true to say that eight years residence in Great Britain, preceded by a voyage to America, and a prolonged acquaintance with speaking, writing, and even thinking in English, had necessarily influenced the direction and expression of my ideas. But little by little I tasted that sociability that distinguishes us, that delightful interaction between intelligent men, rapid and easy, that absence of all arrogance and prejudice, that indifference to fortune and name, that natural levelling of the classes, that equality of spirit that makes French society unique and makes amends for our faults: after a few months living among us, one feels one can only live in Paris.

Book XIII: Chapter 4: The year 1800 – My life in Paris

Paris, 1837

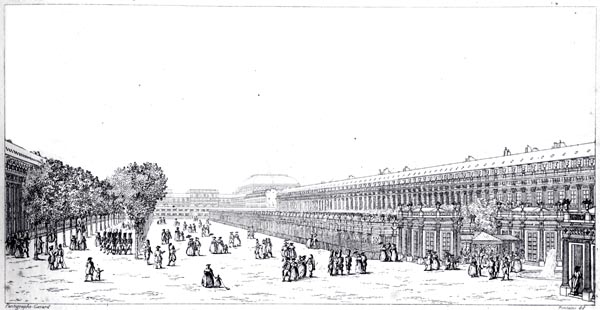

‘Vue Exterieure du Cirque du Jardin du Palais Royal 1799’

Histoire du Palais Royal - Pierre François Léonard Fontaine (p73, 1834)

The British Library

BkXIII:Chap4:Sec1

I shut myself in my mezzanine and gave myself up completely to work. In my moments of relaxation, I made exploratory trips in various directions. In the middle of the Palais-Royal, the Cirque (an immense oblong building) was being constructed; Camille Desmoulins no longer orated outdoors; the crowds of prostitutes, those virginal companions of the goddess Reason, no longer circulated, led by David their wardrobe-master and Corybant. At the exit from each street, among the arcades, one met tradesmen crying their curious wares, shadow puppets, optical glasses, science exhibitions, curious creatures; despite the mound of heads, there were still idlers. From the depths of the cellars of the Palais-Marchand came bursts of music, accompanied by the rattle of drums: perhaps it was there that those giants I sought lived who must necessarily have produced such vast events. I descended; a subterranean ball was in progress in the midst of seated spectators drinking beer. A little hunchback, planted on a table, played a violin and sang a hymn to Bonaparte, which ended with these lines:

For his virtues, for his merits,

He deserves to be their father!

One handed him a sou after the refrain. Such was the nature of that human society that once supported Alexander and now supported Napoleon.

I visited the places where I had walked, and daydreamed, in my early youth. In the former monasteries the members of the clubs had been driven out to join the monks. Wandering behind the Luxembourg, I was led to visit the Charterhouse; it had been completely demolished.

The Place des Victoires, and that of the Vendôme wept for their missing statues of the great King; the Community of Capuchins had been pillaged: the cloister within served as a setting for Robertson’s Phantasmagoria. At the Cordeliers, I sought in vain for the Gothic nave where I had seen Marat and Danton in their prime. On the Quai des Théatins, the church of those monks had become a café and a theatre for tightrope walkers. In the doorway, an illuminated sign depicted the artists, and large letters read: Free show. I dived with the throng into this treacherous lair: I was no sooner in my seat when waiters entered, napkin in hand, shouting like fanatics: ‘Drinks, gentlemen! Drinks!’ I did not wait to hear twice, and escaped in a sorry manner to the mocking laughter of the gathering, because I had not had anything to drink.

Book XIII: Chapter 5: A change in society

BkXIII:Chap5:Sec1

The Revolution was divided into three phases with nothing in common between them: the Republic, the Empire, and the Restoration; three diverse worlds, each of them as completely finished as the other two, and appearing as if separated by centuries. Each of these three worlds had a guiding principle: that of the Republic was equality; that of the Empire force, that of the Restoration liberty. The Republican era was the most original and the most deeply etched, since it is unique in history: never had there been seen, never again will there be seen, physical order produced by moral disorder, unity emerge from government by the masses, the scaffold substituted for law and served in the name of humanity.

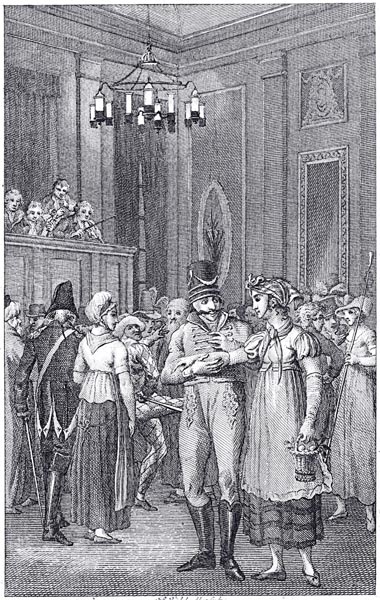

In 1801, I witnessed a second social transformation. The confusion involved was bizarre: by agreeing to wear disguises, a crowd of people became characters they were not: each had their nom de guerre or pseudonym hung round their neck, like the Venetians, in the Carnival, carrying in their hand a little mask to warn that they were masked. One was deemed to be Italian or Spanish, another Prussian or Dutch; I was Swiss. Mothers passed for their son’s aunt, fathers for their daughter’s uncle; a landowner was only his steward. This movement reminded me, in an opposite sense, of that of 1789, when monks and nuns left their cloisters and the old society was invaded by the new: the latter having replaced the former, was in turn replaced itself.

‘Masked Ball’

Reinier Vinkeles, 1809

The Rijksmuseum

However an orderly world began to emerge once more; people left the streets and cafes to go home; they gathered together their remaining family; they reconstituted their inheritance and in collecting the debris, just as after a war, they beat the recall and took stock of what they had lost. The churches which were left undamaged re-opened: I had the happiness of sounding the trumpet at the gate of the Temple. One could distinguish the old retreating Republican generations, from the advancing Imperial generations. The generals produced by the draft, poor, badly spoken, of severe demeanour, who, from all their campaigns, had only brought back wounds and tattered uniforms, passed officers of the Consular army glittering with gold braid. The returning émigré chatted calmly with those who had murdered some of his close relatives. All the doormen, great supporters of the late Monsieur Robespierre, now regretted the spectacles in the Place Louis XV, where they cut off the heads of women who, as my own concierge in the Rue de Lille told me, had white necks like the flesh of chickens. The Septembrists, having changed name and district, had become sellers of cooking apples on street corners; but they were often required to move on, because people, recognising them, knocked their stalls down and tried to beat them. The revolutionaries who had enriched themselves began to occupy the grand houses for sale in the Faubourg Saint-Germain. In the process of becoming barons and counts, the Jacobins spoke only of the horrors of 1793, of the necessity of punishing the proletariat and suppressing the excesses of the populace. Bonaparte, appointing Brutus and Scaevola to his police force, prepared to dye their ribbons, sully their titles, force them to betray their beliefs and denounce their crimes. Among them jostled a vigorous generation conceived in blood and nurtured only to spill that of foreigners; day by day the metamorphoses of Republicans into Imperialists, and the tyranny of the many into the despotism of the one, were being accomplished.

Book XIII: Chapter 6: My life in 1801 – Le Mercure - Atala

Paris, 1837 (Revised, December 1846)

BkXIII:Chap6:Sec1

While I was occupied with removing, adding and altering the pages of Le Génie du Christianisme, necessity obliged me to work on other things. Monsieur de Fontanes was at that time writing for Le Mercure de France: he proposed I should also write for that paper. Such exercises were not without peril: politics was only visible through literature, and Bonaparte’s police read every word. One odd circumstance, in keeping me from sleeping, lengthened my waking hours, and gave me more time. I had bought some turtledoves; they cooed eternally: at night I shut them, in vain, in my travelling trunk; they only cooed the more. In one of the moments of insomnia they provoked, I thought to write a letter for Le Mercure, addressed to Madame de Stael. This sally suddenly caused me to quit the darkness; what my two thick volumes on Les Révolutions had failed to do for me was achieved by a few pages in a newspaper. My head emerged a little from the shadows.

This first success seemed to presage that which followed. I was busy revising the proofs of Atala (an episode included, like René, in Le Genie du Christianisme) when I realised that some pages were missing. Fear gripped me: I though that someone had stolen part of my story, which was a wholly baseless anxiety, since no one thought my work worth the effort of stealing from. Be that as it may, I determined to publish Atala separately, and I announced my intention in a letter sent to the Journal des Débats and Le Publiciste.

Before taking the risk of revealing the work to the light of day, I showed it to Monsieur Fontanes: he had already read parts of it in London in manuscript. When he reached father Aubry’s speech, by Atala’s deathbed, he said sharply in a harsh tone: ‘That’s not it; that’s poor; rework it!’ I withdrew hurt; I felt incapable of improving it. I wanted to hurl the whole thing into the flames; I spent the hours from eight till eleven in the evening, in my room, sitting at my table, my forehead resting on the back of my hands which lay open on my papers. I was angry with Fontanes; I was angry with myself; I did not even attempt to write, I despaired of my ability so deeply. Towards midnight, the sound of my turtledoves registered with me, softened, and rendered more plaintive, by the prison I had confined them in: inspiration returned; I quickly re-drafted the missionary’s speech, without a single gap, without scratching out a single word, just as it remained and exists today. With beating heart, I took it to Fontanes that morning, who cried: ‘That’s it! That’s it! I said you could do better!’

My fame in this world dates from the publication of Atala: I ceased to live for myself alone, and began my public career. After so many military triumphs, a literary triumph seemed a wonder; people were starved. The novelty of the work added to the public interest. Atala appearing in the midst of the Empire’s literature, that school of classicism, a rejuvenated old-age the first glance at which created boredom, was a kind of production of an unknown type. They were unsure as to whether to class it among the monstrosities or among the beauties; was she a Gorgon or a Venus? The assembled academicians gave learned dissertations on her sex and her nature, just as they made their reports concerning Le Génie du Christianisme. The old era rejected it, the new welcomed it.

Atala became so popular that, in company with the Marquise de Brinvilliers, she went to swell Curtius’ waxworks collection. The carters’ taverns were decked with engravings in red, green and blue representing Chactas, Father Aubry, and the daughter of Simaghan. In the wooden booths, on the quais, they displayed my characters modelled in wax, as images of the Virgin and the saints are displayed at fairs. I saw my savage lady in a street theatre plumed with a cockerel’s feathers, speaking of the soul of solitude to a savage of her tribe, in a manner such as to make me sweat with embarrassment. At the Varieties they performed a piece in which a young boy and girl, leaving their lodgings, travelled by stagecoach to marry in their little village; on arrival they spoke of nothing but alligators, egrets and forests, their parents believing they had gone mad. Parodies, caricatures, lampoons showered on me. The Abbé Morellet, to confound me, made his servant girl sit on his knees to prove he was unable to hold that young virgin’s feet in his hands, as Chactas had held Atala’s feet during the storm: if this Chactas of the Rue Anjou were to have had himself painted like that I would have forgiven him his criticism.

BkXIII:Chap6:Sec2

All this added to the hullabaloo surrounding my appearance. I became fashionable. My head was turned: I was unacquainted with the pleasures of self-importance, and I became drunk. I loved fame as one does a woman, like a first love. Nevertheless coward that I was my terror equalled my passion: a conscript, I behaved badly under fire. My natural barbarity, the doubt I had always harboured concerning my talent, made me humble in the midst of my triumph. I hid from my own splendour; I walked in splendour, searching for the means to extinguish the halo with which my head was crowned. In the evenings, my hat pulled down over my eyes, for fear lest someone might recognise the great man, I went to the tavern to read surreptitiously the praise given to me in some little known newspaper. Together with my fame, I extended my peregrinations as far as the steam-driven pumping plant at Chaillot, on the same road where I had suffered so much when travelling to Court; I was no more at ease with my new honours. When My Excellency dined for thirty sous in the Latin Quarter, his food went down the wrong way, disturbed by the gazes of which he was the object. I contemplated myself, I said: ‘It’s only you, this extraordinary creature, that eats like any other man!’ On the Champs-Élysées there was a café I was fond of, because of the nightingales in a cage suspended from the wall of the back room; Madame Rousseau, the proprietress of the place, knew me by sight without knowing who I was. About ten in the evening she would bring me a cup of coffee, and I would find Atala in Les Petites-Affiches, to the sound of my half-dozen Philomelas. Alas! I was soon to hear of Madame Rousseau’s death; our flock of nightingales and the Indian girl who sang: Sweet habit of loving, so needed for living, lasted only a moment!

If success was unable to maintain that stupid passion of vanity in me for long, nor pervert my reason, it held dangers of another kind; those dangers increased with the appearance of Le Génie du Christianisme, and my resignation over the death of the Duc d’Enghien. Then there came pressing around me, as well as the young girls who weep at novels, a crowd of Christians, and those other noble enthusiasts whose hearts beat faster at an honourable action. The ephebes of thirteen or fourteen years, were the most perilous; since knowing neither what they want nor what they want of you, they confuse your image, seductively, with one made of stories, ribbons and flowers. Jean-Jacques Rousseau speaks of the declarations he received on publication of La Nouvelle Héloïse and the conquests it offered him: I have no idea whether it would have delivered empires to me, thus, but I know that I was buried under a pile of perfumed letters; if those letters were not today those of grandmothers, I would be hard put to it to recount with fitting modesty how they competed for a word from my pen, how they gathered up some envelope I had written, and how, blushing, they would hide it, lowering their heads, beneath the veil that fell from their flowing hair. If I was not spoiled, it must be because my character is robust.

Out of real politeness or inquisitive weakness, I sometimes allowed myself to go as far as feeling myself obliged to thank the unknown ladies who sent me their names with their flatteries: one day, climbing to a fourth storey I found a delightful creature, under her mother’s wing, whose home I never set foot in again. A Polonaise invited me into silk-lined rooms; a mixture of odalisque (eastern concubine) and Valkyrie, she had the look of a snowdrop with its white petals, or one of those elegant heath-flowers that replace the other daughters of Flora, when the latter’s season is not yet arrived, or has gone by: that feminine choir, varying in age and beauty, was a realisation of my former sylph. The combined effect on my vanity and my feelings might have been all the more serious in that till then, except for one serious attachment, I had not been sought after nor distinguished from the crowd. However I must say: though it might have been easy to take advantage of passing illusion, the idea of an amorous adventure via the chaste path of Religion was an affront to my integrity: to be loved on account of Le Génie du Christianisme, loved for The Extreme Unction, for The Dance of Death! I could never have played so shameful a hypocrite.

I knew a provincial medical man, Doctor Vigaroux; having arrived at the age where every pleasure takes a day from our life, he said ‘he had no regret for time lost in such a way; without worrying if he conferred the happiness which he received, he travelled towards death which he hoped to make his last delight.’ Nevertheless I was witness to his sorry tears when he died; he could not hide his misery from me; he had left things too late; his white hairs did not dangle low enough to catch and absorb his tears. There is no real unhappiness in leaving this earth except in unbelief: for the man without faith, existence possesses something of the dread with which it senses nothingness; if one had not been born, one could not experience the horror of no longer existing: life for the atheist is a fearsome flash of lightning that only serves to reveal the abyss.

God of generosity and mercy! You have not placed us on earth for worthless sorrows and wretched happiness! Our inevitable disenchantment tells us that our destiny is more sublime. Whatever our faults may have been, if we have retained a steadfast spirit and thought of you amidst our frailties, we will be raised, when your goodness delivers us, to that realm where all bonds are eternal.

Book XIII: Chapter 7: The year 1801 – Madame de Beaumont: her set

Paris, 1837.

BkXIII:Chap7:Sec1

I did not have to wait long for punishment of my vanity as an author, of the most unpleasant kind, though not the most foolish: I had thought to savour in petto the satisfaction of being a sublime genius, not by wearing, as now, a beard and a strange costume, but distinguished merely by my superiority while still dressing like other honest men; vain hope! My pride was due its reward; correction arrived via the politicians I was obliged to know: celebrity is a gift paid for by the soul.

Monsieur de Fontanes was a friend of Madame Bacciochi; he presented me to this sister of Bonaparte, and soon to the First Consul’s brother, Lucien. The latter had a country house near Senlis (Plessis-Chamant), where I was forced to go and dine; the château had belonged to the Cardinal de Bernis. In the garden there was the tomb of Lucien’s first wife, a lady half German and half Spanish, and the memory of the poet-Cardinal. The nymph feeding a stream, its bed dug out with a spade, was a she-mule who drew the water from a well: that was the source of all those rivers Bonaparte caused to flow through his Empire. Efforts were made to obtain my erasure from the list of émigrés; already I was called and was calling myself Chateaubriand in public, forgetting that I ought still to be called Lassagne. The émigrés returned, among others Messieurs de Bonald and de Chênedollé. Christian de Lamoignon, my friend in exile in London, took me to Madame Récamier’s house: the curtain between her and I was suddenly parted.

The person who occupied the greatest place in my existence on my return from the Emigration was Madame la Comtesse de Beaumont. She lived for part of the year at the Château de Passy, near Villeneuve-sur-Yonne, which Monsieur Joubert occupied during the summer. Madame de Beaumont returned to Paris and wished to meet me.

In order to make of my life one long chain of regrets, Providence decreed that the first person to treat me with kindness at the start of my public career was also the first to vanish. Madame de Beaumont heads the funeral procession of those women who have died before me. My most distant memories rest among ashes, and they have continued falling from coffin to coffin; like the Indian Pandit, I recite the prayers for the dead, until the flowers of my rosary have faded.

Madame de Beaumont was the daughter of Armand-Marc de Saint-Hérem, Comte de Montmorin, French Ambassador in Madrid, Commandant of Brittany, a member of the Assembly of Notables in 1787, and entrusted with the portfolio of Foreign Affairs under Louis XVI, who was very fond of him: he died on the scaffold to which he was later followed by several members of his family.

Madame de Beaumont, with a poor rather than a fine figure, strongly resembled the portrait of her by Madame Lebrun. Her face was thin and pale; her almond-shaped eyes would perhaps have been too bright if an extraordinary sweetness had not half-quenched her glances, making them glow languidly, as a ray of light is dimmed by passing through clear water. Her character had a sort of stiffness and impatience which was due to the strength of her feelings, and the inward suffering she experienced. An elevated soul, of great courage, she was born for the world from which her spirit had withdrawn through unhappiness, and by choice; but when a friendly voice summoned up that lonely intellect, it emerged and spoke to you heavenly words. Madame de Beaumont’s extreme weakness made her slow of expression, and that slowness was touching; I only knew this sadly afflicted woman at the time of her flight; she was already mortally ill, and I devoted myself to her sufferings. I had taken lodgings in the Rue Saint-Honoré, at the Hôtel d’Étampes, near the Rue Neuve-du-Luxembourg (Rue Cambon). Madame de Beaumont occupied an apartment in the latter street, with a view of the gardens belonging to the Justice Ministry. I went to see her each evening with her friends and mine, Monsieur Joubert, Monsieur de Fontanes, Monsieur de Bonald, Monsieur Molé, Monsieur Pasquier, and Monsieur Chênedollé, men who have played a role in literature and public affairs.

Full of odd habits and originality Monsieur Joubert will be eternally missed by those who knew him. He exerted an extraordinary hold on the mind and heart, and when he captured you, his image was there like an event, like an obsession that one could not rid oneself of. His great pretension was to calm, yet no one was as troubled as he was: he was on the alert to stifle those emotions of the spirit that he thought harmful to his health, and his friends were always disrupting the precautions he had taken to remain well, since he could not stop himself being moved by their sadness or their joy: he was an egotist who only cared about others. In order to gather his forces, he considered himself obliged to close his eyes and not speak for hours at a time. God alone knows what sounds and turbulence occurred within him during the silence and calm he prescribed for himself. Monsieur Joubert altered his diet and regime from one moment to the next, living on milk one day, and mincemeat the next, jogging at a rapid pace on the roughest of roads, or dawdling with tiny steps along the best laid avenues. When he was reading he would tear out the pages he disliked, possessing, as a result, a personal library composed of eviscerated works, enclosed by overlarge covers.

A profound metaphysician, his philosophy, by a process of elaboration peculiar to himself, became art or poetry: a Plato with the heart of a La Fontaine, he was taken with an ideal of perfection that prevented his achieving anything. In the manuscripts discovered after his death, he wrote: ‘I am like an Aeolian harp, which produces sweet sounds but plays no tune.’ Madame Victorine de Chastenay claimed that he had the air of a soul which had encountered a body by chance, and managed it as best it could: a statement both delightful and true.

We laughed at enemies of Monsieur de Fontanes, who took him for a deep and subtle politician: he was quite simply an irascible poet, direct to the point of fury, a spirit whom contrariness drove to extremes, and one who could no more hide his opinions than accept those of anyone else. His friend Joubert’s literary principles were not his: the former found something good everywhere and in all writings; Fontanes, on the other hand, was horrified by some or another doctrine, and could not bear to hear the names of certain authors pronounced. He was the sworn enemy of the principles of modern composition: to display material events to the reader’s eyes, the workings of crime or the gibbet with its rope, to him seemed enormities; he claimed one should never behold an object except in a poetic setting, as if within a crystal globe. Grief played out mechanically in front of one’s eyes seemed to him mere sensationalism, like the Circus or the Place de Grève; he could not comprehend tragic feeling that ennobles through awe, and changes, through art, into a sweet pity. I cited the Greek vase paintings to him: in the arabesques decorating those vases, one sees the body of Hector dragged behind Achilles’ chariot, while a tiny figure, suspended in the air, represents the shade of Patroclus, consoled by this vengeance enacted by Thetis’ son. ‘Well, Joubert’ Fontanes would cry, ‘what do you say to this metamorphosis of nakedness? How those Greeks could portray the soul!’ Joubert would consider himself under attack, and would get Fontanes to contradict himself, while reprimanding him for his indulgence towards me. These arguments, often extremely comical, were never ending: one evening, at half past eleven, when I was living in the Place Louis XV, in the top story of Madame de Coislin’s house, Fontanes climbed the eighty-four steps to vent his fury, rapping the floor with the tip of his cane, to finish an argument he had left incomplete: it was a question of Picard, whom he set, at that moment, well above Molière; he would have taken great care to avoid writing down a single word of what he said: Fontanes speaking and Fontanes with pen in hand were two different men.

It was Monsieur Fontanes, I love to relate, who encouraged my first attempts; it was he who heralded Le Génie du Christianisme; it was his muse that, full of wondering devotion, directed mine to the new paths into which it was hastened; he taught me how to hide the deformities in things by the manner in which they were lit; to place, as much as it as in me to do so, classical language in the mouths of my Romantic characters. There were once men who were the guardians of taste, like those dragons that guarded the golden apples in the garden of the Hesperides; they only allowed youth to enter when it could touch the fruit without spoiling it.

My friend’s writings set one on a happy course; the spirit experiences well-being and finds itself in a harmonious environment where everything charms and nothing harms. Monsieur de Fontanes revised his works ceaselessly; no one was more convinced, than this master of a former age, of the excellence of the maxim: ‘Hasten, slowly.’ What would he say of the present day, both morally and materially, where they attempt to dig up the road and yet never consider themselves to be travelling quickly enough? Monsieur de Fontanes preferred to travel as the delightful measure took him. You have read what I wrote of him when I met him again in London; the regrets I expressed then, I must repeat here: life obliges us to weep endlessly, in anticipation or in remembrance.

BkXIII:Chap7:Sec2

Monsieur de Bonald had a nimble mind: one might have taken his ingenuity for genius; he had dreamed up his metaphysical politics in Condé’s army, in the Black Forest, like those professors at Jena and Göttingen who have since marched at the head of their students and were killed for the cause of German liberty. An innovator, though he had been a musketeer under Louis XVI, he regarded his seniors as children when it came to politics and literature; and he claimed, employing for the first time that self-conceit of present-day language, that the Vice-Chancellor of the University was not yet advanced enough to understand all that.

Chênedollé, possessing knowledge and talent, acquired rather than natural, was so gloomy he was nicknamed the Raven; he prowled around my works. We had made a treaty: I had abandoned my skies, mists and clouds to him; but he agreed to leave me my breezes, waves and forests.

I am only speaking here of my literary friends; as for my political ones, I am not sure if I should speak to you of them: their principles and speeches have dug deep pits between us!

Madame Hocquart and Madame de Vintimille gathered to the Rue Neuve-du-Luxembourg. Madame de Vintimille, a woman of an earlier age, the like of which few remain, frequented society and reported to us what occurred there; I asked her if they were still founding cities. The description of petty scandals sketched with vivid mockery, without being offensive, made us appreciate the value of our own cautiousness more. Madame de Vintimille and her sister had been celebrated in verse by Monsieur Laharpe. Her language was circumspect, her character restrained, her wit borrowed: she might have known Mesdames de Chevreuse, de Longueville, de La Vallière, and de Maintenon, or Madame Geoffrin and Madame du Deffand. She mixed easily in a society where pleasure was taken in the difference between minds, and in the combination of their various worth.

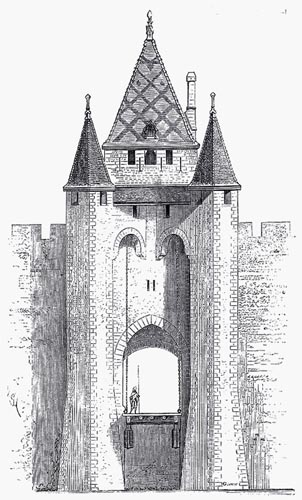

Madame Hocquart was dearly loved by Madame de Beaumont’s brother, whose thoughts were full of her even on the scaffold, just as Aubiac went to the gallows kissing a piece of blue velvet sleeve left to him through Marguerite de Valois’ kindness. From now on, nowhere were gathered under one roof so many distinguished people differing in social position and possessing different destinies, able to speak of the most ordinary or the most elevated things; a simplicity of speech due not to incapacity but choice. It was perhaps the last social venue where the old style French wit was displayed. One no longer finds that urbanity among young French people, the fruit of education transformed by habitual usage into an aspect of character. What happened to that society? Make your plans then, collect your friends, in order to prepare yourself for an eternity of grief! Madame de Beamont is no more, Joubert is no more, Chênedollé is no more; Madame de Vintimille is no more. Once, during the grape harvest, I visited Monsieur Joubert at Villeneuve: I walked with him on the banks of the Yonne; he picked mushrooms in the copses, I gathered autumn crocuses in the meadows. We talked about everything and especially our friend Madame de Beaumont, lost for ever: we summoned up the memory of our former hopes. That evening, we returned to Villeneuve, that town encircled by crumbling walls from the age of Philippe-Auguste and half-ruined towers, above which rose the smoke from the wine-growers’ hearths. Joubert showed me, far-off on a hill, a sandy path through the woods which he took when he went to see his neighbour, concealed in her château of Passy during the Terror.

‘L'Élévation Extérieure de la Porte de Villeneuve-sur-Yonne’

Dictionnaire Raisonné de l’Architecture Française du XIe au XVIe Siècle - Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (p73, 1856)

Wikisource

Since the death of my dear host, I have travelled that region of Sens four or five times. I gazed at the hills from the high road: Joubert no longer walked there; I saw again the woods, fields, vineyards, the little heaps of stone where we used to take a rest. Passing through Villeneuve, I glanced at my friend’s deserted street and shuttered house. The last time it occurred, I was on my way to the Embassy in Rome: ah, if he had been there, I would have carried him off to the grave of Madame de Beaumont! It had pleased God to reveal a heavenly Rome to Monsieur Joubert, still better suited to his Platonic soul, converted to Christianity. I will see him no longer down here: I shall go to him; but he shall not return to me.

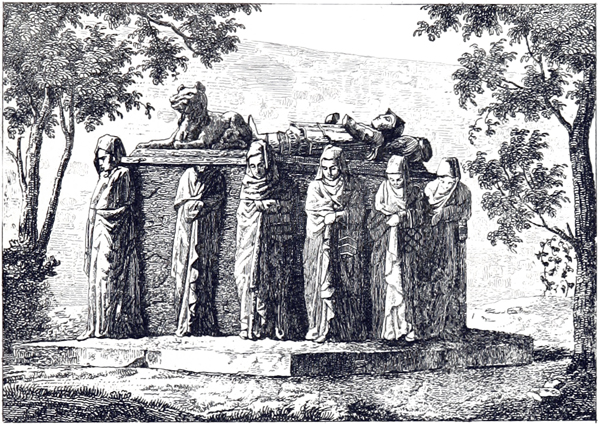

‘Tombeau de Philippe Pot’

France Pittoresque...des Départements et Colonies de la France, Vol 01 - Jean Abel Hugo (p613, 1838)

The British Library

Book XIII: Chapter 8: The year 1801 – Summer at Savigny

Paris, 1837.

BkXIII:Chap8:Sec1

The success of Atala having persuaded me to continue Le Génie du Christianisme, two volumes of which were already in print, Madame de Beaumont offered me a room in the country in a house she had just rented, at Savigny. I spent six months in this retreat of hers, with Monsieur Joubert and other friends.

The house was situated at the entrance to the village, on the Paris side, near an old highway known there as the Chemin de Henri IV; it had its back to a vine-covered slope, and its face to Savigny Park, which ended in a screen of trees, and was crossed by the little River Orge. On the left, the Plain of Viry stretched away as far as the springs of Juvisy. All round this countryside, were valleys, which we visited in the evenings in search of fresh walks.

In the mornings, we breakfasted together; after breakfast, I retired to my work; Madame de Beaumont had the goodness to copy out sections which I indicated to her. This noble woman offered me shelter when I had none: without the peace she granted me, perhaps I would never have finished a work I had been unable to complete during my times of hardship.

I will remember forever certain evenings spent in this friendly refuge; returning from our walks, we would gather together by a clear-water pond, in the middle of a lawn in the kitchen garden; Madame Joubert, Madame de Beaumont and I, would sit on a bench; Madame Joubert’s son rolled on the grass at our feet; that child has already vanished. Monsieur Joubert walked by himself down a gravel path; two guard dogs and a cat played round us, while pigeons cooed in the eaves. What happiness for a man newly returned from exile, after spending eight years in profound isolation, except for a few days swiftly flown! It was usually on such evenings that my friends made me tell them about my travels; I have never described the wildernesses of the New World as well as then. At night, when the windows of our country salon were open, Madame de Beaumont would point out various constellations, saying one day I would remember her teaching me to recognise them; since I have lost her, I have, several times, not far from her grave in Rome, searched for those stars she named, in the firmament; I have seen them gleaming above the Sabine Hills; the rays of light projected from those stars struck the Tiber’s surface in their fall. The place from which I saw them above the woods of Savigny, and the places where I saw them once more; my unsettled fate; the sign left behind in the sky by a woman, one by which I was to remember her, all this broke my heart. By what miracle does man consent to do what he does on this earth, he who must die?

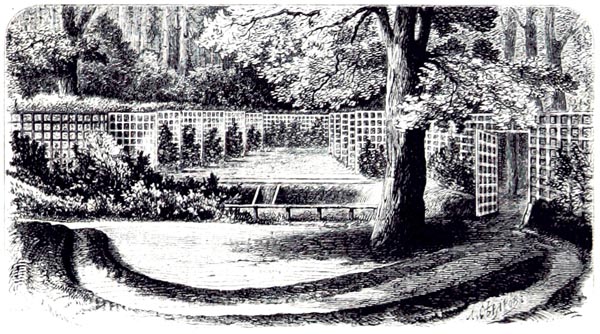

Pavlovsk. Ocherk History and Description, 1777-1877 - Compiled at the Request of Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich (p173, 1877)

The British Library

One evening, we saw someone climb surreptitiously through one window and leave by another; it was Monsieur Laborie; he was fleeing from Bonaparte’s clutches. Shortly afterwards there appeared one of those souls in pain who are of a different species to other souls, and who merge, in passing, their obscure unhappiness with the vulgar sufferings of the human species: it was Lucile, my sister.

After my arrival in France, I had written to my family to tell them of my return. Madame la Comtesse de Marigny, my elder sister, first to seek me, mistook the street, and met with five Monsieur Lassagnes, the last of whom emerged from a cobbler’s trap-door to answer to his name. Madame de Chateaubriand arrived in turn: she was delightful, and filled with all the qualities fitted to grant me the happiness I have found with her, since we have been reunited. Madame la Comtesse de Caud, Lucile, presented herself next. Monsieur Joubert and Madame de Beaumont conceived a passionate fondness and tender pity for her. A correspondence began then between them, which only ended with the death of the two women who inclined to each other like two flowers of a similar nature on the point of fading away. Madame Lucile, having stopped at Versailles, on the 30th of September 1801, I received this note from her: ‘I write to beg you to thank Madame de Beaumont for me, for the invitation to Savigny she sends me. I hope to have that pleasure of visiting, in about a fortnight’s time, as long as there is no impediment on Madame de Beaumont’s side.’ Madame de Caud came to Savigny as she had promised.

I have told you how, in my youth, my sister, a canoness of the Chapter of Argentière, and destined for that of Remiremont, had conceived an attachment for Monsieur de Malfilâtre, a counsellor at the High Court of Brittany, an attachment which, locked in her breast, had added to her innate melancholy. During the Revolution, she married Monsieur le Comte de Caud, and lost him after fifteen months of marriage. The death of Madame la Comtesse de Farcy, a sister whom she loved tenderly, increased Madame de Caud’s sadness. She then attached herself to my wife, Madame de Chateaubriand; and gained an ascendancy over her which became tiresome, since Lucile was forceful, imperious, unreasonable, and Madame de Chateaubriand, subject to her whims, in order to render her the services which a wealthier friend may to a sensitive and less fortunate one, hid those services from her.

Lucile’s genius and her deep nature had almost brought her to Rousseau’s state of madness; she thought she was exposed to secret enemies: she gave Madame de Beaumont, Monsieur Joubert, and myself, false addresses at which we might write to her, she examined the seals of her letters, looking to ensure that they had not been broken; she wandered from house to house, unable to stay with my sisters or my wife; she had conceived an antipathy for them, and Madame de Chateaubriand, after having been devoted to her beyond anything one might conceive, had finally been overwhelmed by the burden of so cruel an attachment.

Another fatality struck Lucile: Monsieur de Chênedollé, living near Vire, had gone to see her at Fougères; soon there was question of a marriage, which fell through. Everything eluded my sister at once, and left to herself she had not the strength to endure it. This plaintive spectre sat for a moment on a stone, in the smiling solitude of Savigny: so many hearts had welcomed her there with joy! They would have been more than happy to restore her to the sweet realities of existence! But Lucile’s heart could only beat in an atmosphere made expressly for herself, which no one else had ever breathed. She consumed the days swiftly in that isolated world in which heaven had placed her. Why had God created a being destined only to suffer? What mysterious connection can there be between a tormented nature and an eternal principle?

My sister had not altered; she had only taken on the fixed expression produced by her ills: her head was a little bowed, like one on whom the hours have weighed. She reminded me of my parents; those first family memories, summoned by the grave, surrounded me like moths rushing to burn themselves at night in the dying flames of a funeral pyre. In contemplating her, I thought I saw all my childhood in Lucile, gazing at me a little lost from behind her eyes.

The vision of grief had vanished: this woman, burdened with life, seemed to have come seeking the other dispirited woman whom she was obliged to carry away.

Book XIII: Chapter 9: The year 1802 – Talma

Paris, 1837.

BkXIII:Chap9:Sec1

The summer passed: according to custom, I promised to repeat it again the following year; but the clock-hand never returns to the hour one would wish it to revisit. During the winter in Paris, I made several new acquaintances. Monsieur Julien, wealthy, obliging, a cheerful guest, though from a family where they kill themselves, had a box at the Théâtre Français; he lent it to Madame de Beaumont; I went to see the show on four or five occasions with Monsieur de Fontanes and Monsieur Joubert. When I entered society, the old comedy was in full swing; I met with it again when it was in a state of complete decay; tragedy was still going strong, thanks to Mademoiselle Duchesnois and above all to Talma, who had achieved the peak of his dramatic talent. I had seen him on his debut; he was not as handsome and in a manner of speaking, not as young as he was when I saw him again: he had acquired distinction, nobility and gravitas with the years.

The portrait Madame de Staël has painted of Talma in her work on Germany is only half true: the brilliant writer perceived the great actor with a woman’s imagination, and endowed him with a quality he lacked.

Talma had no use for the Middle Ages: he understood nothing of the gentleman; he did not know of our ancient society; he had not sat at the ladies’ table, in a Gothic tower in the depths of the woods; he was ignorant of the pliability, the sensitivity of taste, the gallantry, the swift movement of manners, the simplicity, the tenderness, the heroic sense of honour, the Christian devotion of chivalry: he was no Tancred, or Coucy, or at least, he transformed them into heroes of a Middle Ages of his own creation: Othello was at the root of his Vendôme.

What was Talma, then? His age and classical times were both his. He had deep and intense passions, inspired by love and by his country; they exploded from his breast. He possessed the fatal inspiration, the genius for disorder, of that Revolution through which he had passed. The terrible scenes, that had surrounded him, echoed, in his art, with the distant and mournful tones of Sophocles’ and Euripides’ choruses. His mode of acting which was not the accepted mode, gripped you like an illness. Black ambition, remorse, jealousy, the soul’s melancholy, physical pain, madness and conflict among the gods, human grief: that is what he understood. His mere entry during a scene, the mere sound of his voice, was powerfully tragic. His brow showed suffering and thought, which were alive in his immobility, his stance, his gestures, his paces. A Greek, he arrived, gloomy and panting from the ruins of Argos, an immortal Orestes, tormented as he had been for three thousand years by the Eumenides; A Frenchman, he came from the solitudes of Saint-Denis, where the Parcae of 1793 had cut the thread of the kings’ sepulchral existence. Utterly sad, waiting for something unknown but decreed by an unjust heaven, he stepped forward, driven by destiny, inexorably bound, between fatality and terror.

That time cast an inevitable shadow over ageing dramatic masterpieces; its gloom could change the clearest Raphael into a Rembrandt; without Talma a major part of the wonders of Corneille and Racine would have remained unknown. Dramatic skill is a fiery torch; it communicates its flames to other partially-lit torches and makes those dramatists of genius live again to delight you with their re-born splendour.

To Talma we owe the perfection of the actor’s costume. But is theatrical truth and authenticity of dress as necessary to the art as one might suppose? Racine’s characters gain nothing from the cut of their cloth: in the paintings of the masters the backgrounds are poorly done and the clothes inexact. Orestes’ Rages or Joad’s Prophecy, played in a salon by Talma in morning dress, have just as much effect as if they are declaimed on the stage by Talma in a Greek cloak or a Hebrew robe. Iphigenia was dressed like Madame de Sévigné, when Boileau addressed these fine lines to his friend:

‘Never did Iphigenia, at Aulis, sacrificed,

Cost the throng of Greeks more tearful cries,

Than La Champmeslé shed, in her guise,

In this great drama played before our eyes.’

This fidelity in representing the inanimate object embodies the spirit of the arts of our times: it heralds the decadence of high poetry and true drama; we content ourselves with minor beauties when we are powerless to create great ones; we imitate armchairs and velvet upholstery, to deceive the eye, when we can no longer draw the features of the man seated in that armchair, on that upholstery. Moreover, once we have stooped to this exactness of material form, we find ourselves forced to replicate it; since the public, materialists themselves, demand it.

Book XIII: Chapter 10: The years 1802 and 1803 – Le Génie du Christianisme – Disaster predicted – The reason for ultimate success

BkXIII:Chap10:Sec1

Meanwhile I completed Le Génie du Christianisme: Lucien asked to see various proof sheets; I sent them to him; he added some commonplace notes in the margins.

Although the success of my large work was as brilliant as that of little Atala, it nevertheless provoked more opposition: it was a serious work in which I was no longer attacking the principles of classical literature and philosophy by means of a novel, but by reason and faith. The empire of Voltaire gave the alarm, and rushed to arm itself. Madame de Staël was mistaken about the prospect for my religious writings: they brought her the work uncut; she riffled her fingers through the pages, stopped at the chapter on Virginity, and said to Monsieur Adrien de Montmorency, who happened to be with her: ‘Oh! My goodness! Our poor Chateaubriand! This will fall flat on its face!’ The Abbé de Boulogne, having had access to parts of my work before submitting them to print, replied to a bookseller who consulted him: ‘If you wish to ruin yourself, publish it.’ Yet the Abbé de Boulogne has since pronounced an overly magnificent eulogy regarding my book.

‘Mme de Staël, d'Après le Portrait Peint par le Baron Gérard’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p43, 1888)

The British Library

Everything, in fact, seemed to predict disaster for me: what hope could I have, I without a name and without patrons, of countering the influence of Voltaire, dominant for more than half a century, of Voltaire, who had raised the enormous edifice completed by the Encyclopedists and consolidated by all the distinguished men of Europe? What! Were Diderot, D’Alembert, Duclos, Dupuis, Helvétius, Condorcet spirits without authority? What! Must the world return to the Golden Legend, renounce its admiration acquired through the master-works of science and reason? Could I win a cause that Rome in its wrath, the clergy with all its power, could not protect: a cause defended in vain by the Archbishop of Paris, Christophe de Beaumont, supported by Parliamentary decrees, by armed force and in the King’s name? Was it not as ridiculous as rash for an obscure individual to oppose a philosophical movement so overwhelming that it produced the Revolution? It was a curiosity to see a pygmy flexing his little arms to stifle a century’s progress, arrest a civilisation, and set the human race moving backwards! By God’s grace, it would only take a word to crush this madman: for Monsieur Ginguené, savaging Le Génie du Cristianisme, declared in La Décade, that the criticism came too late, since my repetitious harping was already forgotten. He said this, five or six months after the publication of a work that the assault of the whole French Academy, on the occasion of the Decennial Prize, could not kill.

It was amongst the ruins of our temples that I published Le Génie du Christianisme. The faithful believed themselves rescued: there was a need then for faith, avidity for religious consolation arising from the long years during which those consolations were denied. What supernatural powers were needed to overcome so many adversities suffered! How many shattered families were forced to search for their lost children in the bosom of the Father of Mankind! How many broken hearts, how many isolated souls, called for a divine hand to heal them! They ran to the house of God as one hurries to the doctor’s house during a plague. The victims of our troubles (and what an array of victims) hastened to the altar; suffering shipwreck they clung to the rock on which they sought salvation.

Bonaparte, desiring at that time to establish his power on the deepest foundations of society, came to an arrangement with the See of Rome: initially he placed no obstacle in the way of a work that increased the popularity of his intentions; he had to struggle with those surrounding him, and against the declared enemies of religion; he was happy then to be defended from without by the opinions which Le Génie du Christianisme expressed. Later, he repented of his error: traditional ideas of monarchy entered with these religious ideas.

BkXIII:Chap10:Sec2

One episode from Le Génie du Christianisme, which made less noise then than Atala, fixed a typical character from modern literature; however, if René did not already exist, I would no longer choose to write it; if it were possible for me to destroy it, I would destroy it. A whole hive of René poets and René prose-writers has swarmed: one hears nothing but appalling, disjointed phrases; it has seemed nothing but winds and storms, unspecified ills delivered over to clouds and the night. There is not a single puppy leaving college who has not dreamed himself the most unfortunate of men; not a stripling of sixteen who is not tired of life, who does not think himself tormented by genius; who, in the depths of his thoughts, is not given to waves of passion; who has not clasped his pale, tousled forehead, who has not amazed astonished men with an illness whose name he knows no more than they.

In René, I exposed the sickness of my era; but it was a different folly of the novelists to render affliction present beyond everything else. The common feelings which are the foundation of humanity, paternal and maternal affection, filial piety, friendship, love, are inexhaustible; but unique modes of feeling, individualities of character and spirit cannot be broadened and multiplied in vast and numerous tapestries. The little undiscovered corners of the human heart are a narrow field; there is nothing left to gather from that field after the first hand has reaped there. A malady of the soul is not a permanent or natural state: one cannot reproduce it, to create a literature, by taking advantage of universal feeling continually modified at the hands of artists who mould it to shape its form.

Be that as it may, literature was dyed with the colours of my religious painting, as public affairs have retained the phraseology of my writings on the city; La Monarchie selon la Charte, has been the basis of our representative government, and my article for the Conservateur, on moral interests and material interests endowed politics with those two designations.

Writers did me the honour of imitating Atala and René, just as the pulpit followed my tales of Missions and Christian good works. The passages in which I demonstrate that in driving out the pagan gods of the woods, our religion broadened so as to return nature to solitude; the paragraphs where I handle the influence of our religion on our ways of seeing and depicting, where I examine the changes which occurred in poetry and oratory; the chapters that I dedicated to research into the alien feelings introduced into dramatic roles in antiquity, contained the seeds of the new criticism. Racine’s characters, as I said, are and are not Greek characters, they are Christian characters: that had not been at all understood.

If the effect of Le Génie du Christianisme had been no more than a reaction against the doctrines to which were attributed our revolutionary ills that effect would have ceased when its cause vanished; it would not have lasted until this moment in which I write. But the effect of Le Génie du Christianisme on opinion was not limited to a momentary resurrection of religion, as if pretended to on the point of death: a more lasting metamorphosis occurred. If there was stylistic innovation in the work, there was also a change of doctrine; the foundations were altered like the form; atheism and materialism were no longer the basis for belief or unbelief in young minds; the idea of God and the immortality of the soul reclaimed their empire: from then on, there was an alteration in that chain of ideas which linked one with another. One was not nailed in place by antireligious prejudice; one was no longer obliged to remain a mummy of non-existence, wound round by philosophical bindings; one allowed oneself to examine each system however absurd one might find it to be, even were it a Christian one.

Besides the faithful who returned to the voice of their Pastor, other faithful were formed a priori, by this right of free examination. Establish God as a principle, and the Word follows: the Son is born inevitably of the Father.

The various abstract schemes only serve to substitute more incomprehensible mysteries for the Christian ones: pantheism, which moreover takes two or three different forms, and which it is today’s fashion to ascribe to enlightened intellects, is the most absurd of Eastern daydreams, brought back to light by Spinoza; regarding this subject it suffices to read the article by a sceptical Bayle on Amsterdam’s Jewish philosopher. The peremptory tone with which some people speak about all this appals one, unless it is due to lack of study: they are struck by words they cannot understand, and imagine them to be those of transcendental genius. How easy it is to believe that Abelard, Saint Bernard, Saint Thomas Aquinas brought to metaphysics an intellectual superiority which we cannot match; that the systems of Saint-Simon, Fourier’s Phalansterianism, and Humanism had been discovered and practised already by sundry heretics: that what are held up to us as products of progress, as new discoveries, are the outdated concepts trailed for fifteen centuries through the schools of Greece and the colleges of the Middle Ages. The trouble is that the first sectarians were unable to found their Neo-Platonist republic, such as Gallienus consented to Plotinus attempting in Campania: so, much later, we encounter the crime of burning sectarians for wishing to establish communal possessions, and declaring prostitution holy, asserting that a woman could not, without sin, refuse a man who demanded casual union with her in Jesus Christ’s name: to arrive at this union, they claimed, it was only necessary to relinquish the soul, and allow it to rest for a moment in God’s breast.

The spiritual shock that Le Génie du Christianisme gave, thrust the eighteenth-century out of its rut, and pushed it one and for all onto a new track: people began once more, or rather for the first time, to study the sources of Christianity: on re-reading the Fathers (assuming they had ever read them in the first place) they were struck by a plethora of interesting facts, scientific philosophy, beauties of style in every genre, ideas, which, by a more or less obvious gradation, created the transition from ancient society to modern society: a unique and memorable era of humanity, when heaven communicated with earth through the souls of men of genius.

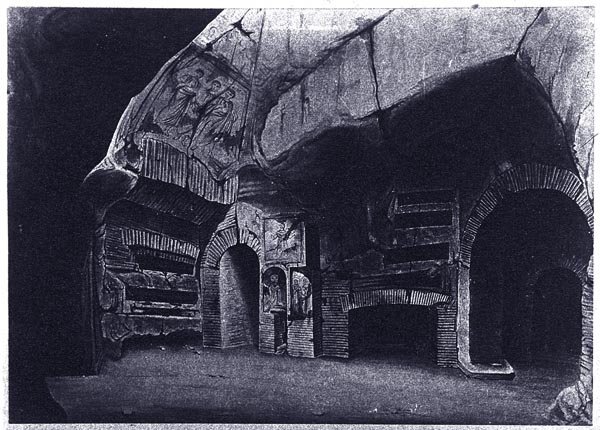

In the past, beside the crumbling world of paganism, another world was created, as if outside society, a spectator of those great spectacles, poor, secluded, solitary, not mixing in life’s affairs except when its teachings or help were needed. It is a marvellous thing to behold those first bishops, almost all honoured by the name of saint or martyr, those simple priests watching over their relics and catacombs, those monks and hermits in their monasteries and grottos, creating their rule of peace, morality and charity, when all was war, corruption and barbarity: journeying to the tyrants of Rome and from them to the leaders of the Tartars and the Goths, in order to prevent the injustices of the former and the cruelties of the latter, halting armies with a wooden cross and the word of peace: the weakest of men, yet defending the world against Attila; set between two universes in order to connect them, in order to solace the last moments of a dying society and support the first steps of a society fresh from its cradle.

‘Catacomb, Rome Italy’

Anonymous, c. 1900 - c. 1925

The Rijksmuseum

Book XIII: Chapter 11: Le Génie du Christianisme, continued – The faults of the work

BkXIII:Chap11:Sec1

It was impossible for the ideas developed in Le Génie du Christianisme not to contribute to an alteration in ideas. It is still that work which present taste turns to in order to discover the edifices of the Middle Ages: it is I who woke the new century to an admiration for the ancient temples. If my view has been carried too far; if it is untrue that our cathedrals match the beauty of the Parthenon; if it is false that those churches teach us forgotten facts in documents of stone; if it is foolish to maintain that those granite memoirs reveal to us things which escaped the Benedictine savants; if by dint of repetition of the Gothic everyone is dying of boredom, it is not my fault. As for the rest, in relation to the arts, I know what is lacking in Le Génie du Christianisme; that section of my work is defective, because in 1800 I did not understand the arts: I had not seen Italy, Greece, or Egypt. Similarly, I had not taken sufficient account of the lives of the saints and the legends; yet they offered me wonderful stories: selecting from them with taste, one could have reaped an abundant harvest. This rich field of the imagination of the Middle Ages surpassed in fecundity Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the Milesian fables. There are, moreover, false or facile judgements in my work, such as those I held concerning Dante, to whom I have since rendered shining homage.

Among my more serious works, I completed the task of Le Génie du Christianisme in my Études historiques, one of my works less talked of and less stolen from.

The success of Atala delighted me, because my spirit was still fresh; that of Le Génie du Christianisme was tiresome to me: I was obliged to give my time to useless correspondence and compliments from abroad. Admiration, so-called, did not compensate me for the disgust that seizes a man whose name the crowd has retained. What benefit can offset the peace you have lost by allowing the public to invade your privacy? Add to that the difficulties that the Muses delight in inflicting on those who follow their cult, the embarrassment of an easy-going character, the inability to deal with good fortune, time-wasting, unstable moods, lively affections, sadness for no reason, joy without cause: who would wish, if he were in charge, to purchase on these conditions, the uncertain advantages of a reputation that one is not sure of achieving, which will be challenged during one’s lifetime, which posterity will fail to confirm, and from which your death will render you forever remote?

The literary controversy regarding novelties of style which Atala generated was renewed on publication of Le Génie du Christianisme.

A characteristic trait of the Imperial school, and even the Republican school, is to observe: while society advanced, for good or ill, literature remained stationary; a stranger to the change in ideas, it failed to be involved in its times. In comedy, the lords of the manor, Colin, Babet, or the intrigues of those salons that are no longer known, were played (as I have already remarked) in front of rough and blood-stained men, destroyers of those manners whose portrait was displayed to them; in tragedy the plebeian stalls were entranced by the families of nobles and kings.

Two things held literature frozen in the eighteenth century; the impiety that Voltaire and the Revolution had brought to it, the despotism with which Bonaparte controlled it. The Chief of State found it advantageous to subordinate literature which he had confined to barracks, where it presented arms, and emerged when he cried: ‘On parade!’; marched in ranks, and manoeuvred like an army. Any independence seemed like a rebellion against his authority; he no more desired a riot of words and ideas than he wished to experience insurrection. He suspended Habeas corpus with regard to thought as with regard to individual liberty. We also recognised that the public, weary of anarchy, willingly accepted their rulers’ yoke once more.

BkXIII:Chap11:Sec2

The literature which expresses the new era has only held sway for forty or fifty years from the moment whose idiom it became. During this half century it has only been employed by the opposition. It was Madame de Staël, Benjamin Constant, Lemercier, Bonald, and, finally, I who first spoke that language. The changes in literature, which the nineteenth century boasted of, arose from emigration and exile; it was Monsieur de Fontanes who hatched these birds of another species than his own, because, returning to the seventeenth century, he had acquired the strength of those times, and forsaken the sterility of the eighteenth. One aspect of the human mind, that which deals with transcendental matters, advances alone at the same rate as civilisation; unfortunately the glory of knowledge is not without its stains: Laplace, Lagrange, Cuvier, Monge, Chaptal, Berthollet, all those prodigies, once fierce democrats, became Napoleon’s most obsequious servants. One must say this in honour of literature: the new literature was liberated, science was servile; character had not bowed to genius, yet those in whom thought had mounted to the heights of heaven, could not raise their souls above the level of Bonaparte’s feet: they claimed to have no need of a God, because they had need of a tyrant.

Napoleonic classicism was the genius of the nineteenth century decked out in Louis XIV’s wig, or curly-haired as in the time of Louis XV. Bonaparte wished the men of the Revolution only to appear at his court in formal dress, sword at side. One was not seeing the France of the time; it was not about rank, it was about discipline. Also, nothing was more tedious than that pallid resurrection of previous literature. That frigid copy, that unproductive anachronism vanished when the new literature made its thunderous appearance with Le Génie du Christianisme. The death of the Duc d’Enghien had the benefit for me, in setting me apart, of allowing me to follow my individual aspirations in solitude and prevented me from enlisting in the regular infantry of old Pindus: I owe my intellectual liberty to my moral liberty.

In the last chapter of Le Génie du Christianisme, I consider what might have happened to the world if the faith had not been preached at the moment of the Barbarian invasion; in a further paragraph, I mention an important study to be undertaken on the changes that Christianity brought in the law after the conversion of Constantine.

Supposing that religious opinion existed as it does now at the moment when I am writing, Le Génie du Christianisme being yet to do, I would create it quite differently than it is: instead of recalling the benefits and institutions of our religion in the past, I would show that Christianity is the thought of the future and of human liberty; that its redemptive and messianic thought is the sole basis for social equality; that it alone can establish it, because it sets the necessity of duty, the corrective to and regulator of the democratic instinct, alongside that equality. The law is not sufficient to control equality, because it is not permanent; it acquires its powers from legislation; but legislation is the work of men who change and vanish. A law is not always mandatory; it can always be altered by another law: morality on the other hand is permanent; its power is within, because it arises from the immutable order; that alone can give it durability.