François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXVI: The Berlin Embassy: 1821

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXVI: Chapter 1: My life in 1821 – The Berlin Embassy – Arrival in Berlin – Monsieur Ancillon – The Royal Family – Celebrations for Grand-Duke Nicholas’ marriage – Berlin

- Book XXVI: Chapter 2: Ministers and Ambassadors – History of the Court and society

- Book XXVI: Chapter 3: William Humboldt – Adelbert de Chamisso

- Book XXVI: Chapter 4: Princess William – The Opera – A concert

- Book XXVI: Chapter 5: My first despatches – Monsieur de Bonnay

- Book XXVI: Chapter 6: The Park – The Duchess of Cumberland

- Book XXVI: Chapter 7 – My despatches, continued

- Book XXVI: Chapter 8 – A memoir I started: on Germany

- Book XXVI: Chapter 9 – Charlottenburg

- Book XXVI: Chapter 10 – The interval between my Berlin and London Embassies – The baptism of Monsieur le Duc de Bordeaux – A letter to Monsieur Pasquier – A letter from Monsieur de Bernstorff – A letter from Monsieur Ancillon – A last letter from Madame the Duchess of Cumberland

- Book XXVI: Chapter 11 – Monsieur de Villèle, Finance Minister– I am appointed Ambassador to London

Book XXVI: Chapter 1: My life in 1821 – The Berlin Embassy – Arrival in Berlin – Monsieur Ancillon – The Royal Family – Celebrations for Grand-Duke Nicholas’ marriage – Berlin

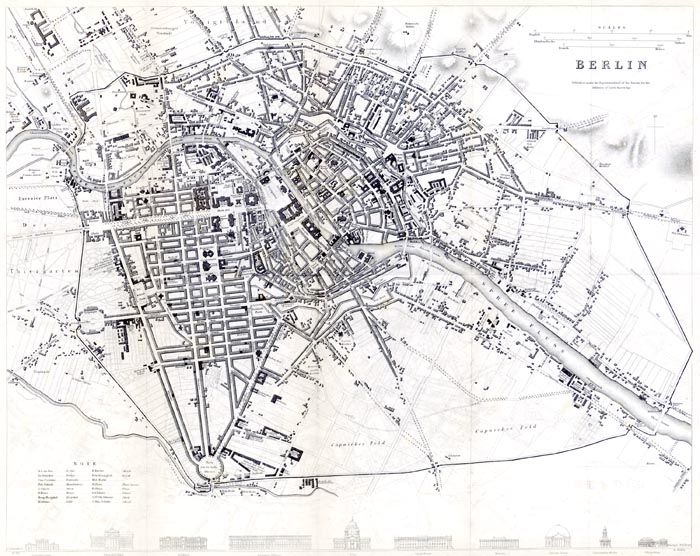

‘Berlin’

Asher's Picture of Berlin and its Environs - Adolph Asher (p143, 1837)

The British Library

BkXXVI:Chap1:Sec1

I departed France, leaving my friends in possession of posts which I had purchased for them at the price of my own absence: I was a lesser Lycurgus. What was fine about it was that the first trial of my own political strength that I had attempted had set me at liberty; I was about to enjoy that freedom abroad in a position of power. At the heart of this new situation for me, I saw romance, of a kind, confused with the reality: was there nothing in court life? Were there not solitudes of another kind? There were perhaps Elysian Fields with their shades.

I left Paris on the 1st of January 1821: the Seine was frozen, and for the first time I travelled the roads with the comforts money could buy. Gradually I recovered my contempt for wealth; I began by feeling that it was a fine thing to ride in a comfortable carriage, to receive good service, not to have to bother with anything, to be preceded by a giant chasseur from Warsaw, always half-starved, who, in the absence of the Tsar, would have devoured Poland all by himself. But I quickly accustomed myself to my good fortune; I had a presentiment that it would not last long, and I would soon be back on my own two feet when it suited. By the time I arrived at my destination, nothing remained of my journey but my original inclination for the journey itself; an inclination for freedom – the satisfaction of having loosed my ties to society.

You will read, when I return from Prague in 1833, what I have to say of my old memories of the Rhine: I was obliged, because of the ice, to ascend its banks, and cross above Mainz. I barely concerned myself with Maguntia, its archbishop, its three or four sieges, and the printing press by mean of which however I held sway. Frankfurt, a Jewish city, only detained me for one of its business transactions: a currency conversion.

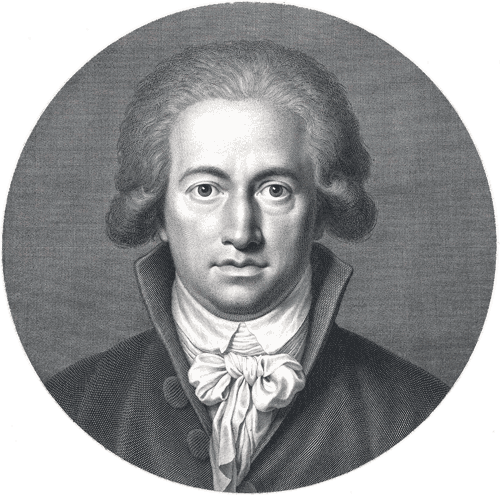

The journey was a melancholy one: the high-road was snow-covered and frost wreathed the branches of the pine trees. Jena appeared in the distance with the larvae of its twin battles. I passed through Erfurt and Weimar: the Emperor was no longer at Erfurt; Goethe, whom I so much admired, and whom I now admire a great deal less, lived in Weimar. The singer of Matter lived, and its ancient dust yet clung about his genius. I might have known Goethe, and I never met him; he leaves a gap in the procession of famous people who have passed before my eyes.

‘Portrait of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’

Johann Heinrich Lips, 1791

The Rijksmuseum

The tomb of Luther at Wittenberg did not detain me: Protestantism is not a religion but an illogical heresy; politically, an abortive revolution. Having eaten a little rye bread, while crossing the Elbe, that must have been kneaded in a cloud of tobacco smoke, I could have done with a drink from Luther’s great glass, conserved as a relic. Passing through Potsdam and crossing the Spree, a river of ink on which barges, guarded by white dogs, ride, I arrived in Berlin. There, as I have said, lived the false Julian in his false Athens. I looked in vain for the sun of Mount Hymettus. I wrote Book IV of these Memoirs in Berlin: there you have seen my description of that city, my trip to Potsdam, my thoughts on Frederick the Great, his horse, his greyhounds, and Voltaire.

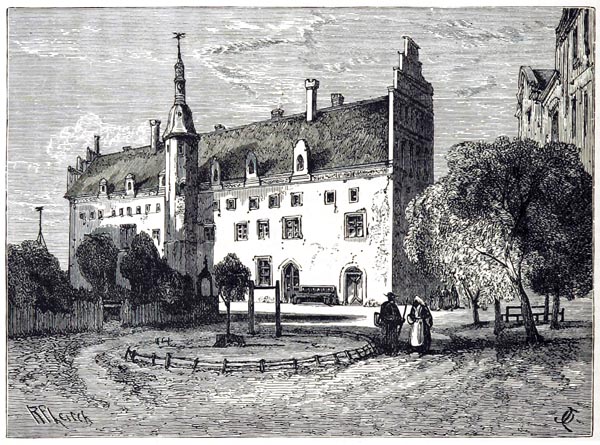

‘Luther's House, Wittenberg’

Cassell's Illustrated Universal History, Vol 04 - Edmund Ollier (p102, 1893)

The British Library

Staying at an inn for the night of the 11th of January, I then went off to reside on Unter den Linden, in a house vacated by Monsieur the Marquis de Bonnay, which belonged to Madame the Duchess de Dino; I was received by Messieurs de Caux, de Flavigny and de Cussy, secretaries to the legation.

On the 17th of January, I had the honour of presenting Monsieur le Marquis de Bonnay’s letter of re-accreditation, and my letter of accreditation, to the King, who lodged in a simple house, its only distinction being two sentries at the door: anyone might enter; anyone might speak to him if he was at home. This simple style adopted by the German Princes contributed to rendering the names and prerogatives of the great less apparent to inferior mortals. Frederick-William went out each day, at the same hour, in an uncovered carriage which he drove himself, helmet on his head, a greyish cloak on his back, to smoke a cigar in the park. I often met him and we would continue our walks side by side. When he returned to Berlin, the sentry at the Brandenburg Gate announced him at the top of his voice; the guard presented arms and marched off; the King passed through, and all was done.

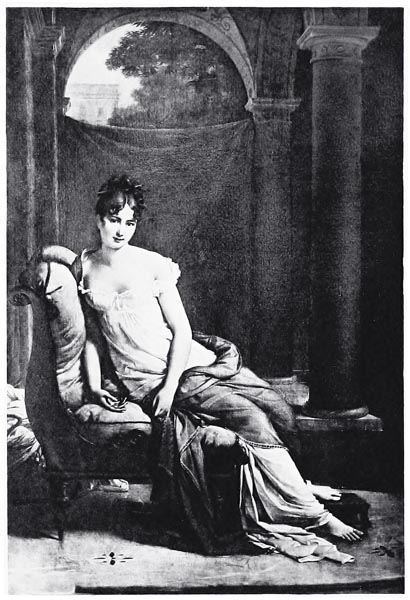

On the same day I paid court to the Royal Prince and his brothers, young and very light-hearted military men. I saw the Grand-Duke Nicholas and the Grand-Duchess, not long married, and still in the midst of celebrations. I also met the Duke and Duchess of Cumberland, Prince William, the King’s brother, and Prince Augustus of Prussia, long our prisoner: he had wanted to marry Madame Récamier; he owned the fine portrait of her that Gérard had painted and which he had exchanged with the prince for the picture of Corinna.

‘Madame Récamier, d'Après le Portrait Peint par François Gérard’

Madame Récamier - Edouard Herriot, Alys Hallard (p7, 1906)

Internet Archive Book Images

I was urged to seek out Monsieur Ancillon. We knew one another through our writings. I had met him in Paris with his pupil the Crown Prince; in the interim he had been charged with the Foreign Affairs portfolio in Berlin during Count von Bernstorff’s absence. His life was very sad: his wife had lost her sight: all the doors of his house were left open; the poor blind lady roamed from room to room among her flowers, and perched here and there like a nightingale in a cage: she sang beautifully but soon died.

Monsieur Ancillon, like many of Prussia’s illustrious men, was of French origin: a Protestant Minister, his opinions were at first extremely liberal; little by little they hardened. When I met him again in Rome in 1828, he had become a moderate Royalist once more, and reverted to monarchical absolutism. With a fierce delight in generous feeling, he had a fear and hatred of revolutionaries; it was that hatred that pushed him towards despotism, in order to seek shelter there. Do those who still celebrate 1793, and admire the crimes committed then, never comprehend how the horror with which those crimes gripped people presents an obstacle to the establishment of liberty?

There was a reception at court, and there commenced the honours shown me of which I was so little worthy. Jean Bart wore a suit of cloth of gold lined with silvered cloth, on his visit to Versailles, which made him feel very uncomfortable. The Grand-Duchess, now the Empress of Russia, and the Duchess of Cumberland took my arm in a Polish march: my romance with society began. The air of that polonaise was a kind of pot-pourri composed of several little pieces among which, to my great satisfaction, I recognised the song about King Dagobert: it encouraged me, and came to the rescue of my timidity. These receptions were repeated; one of them in particular took place in the King’s great palace. Not wishing to give an account of it myself, I reproduce here the one submitted to the Berlin Morgenblatt by the Baroness von Hohenhausen:

‘The Empress Alexandra, Wife of Nicholas I, From a Painting by Hesse in Berlin’

The Court of Russia in the Nineteenth Century - Edward Arthur Brayley Hodgetts (p249, 1908)

Internet Archive Book Images

‘Berlin, the 22nd of March 1821.

Morgenblatt (The Morning Paper), no. 70.

One of the notable people who attended this reception was the Vicomte de Chateaubriand, the French Ambassador, and, however splendid the spectacle unfolding before their eyes, Berlin’s lovely ladies still spared a glance for the author of Atala, that fine and melancholy story in which the most ardent love succumbs in its struggle with religion. The death of Atala and Chactas’ moment of happiness, during a storm in the ancient forests of America, painted in Milton’s tones, remain forever engraved on the memories of all its readers. Monsieur de Chateaubriand wrote Atala in his youth, during which he was painfully afflicted by exile from his homeland: from that derives the profound melancholy and burning passion which fill the entire work. At present, this consummate Statesman has dedicated his pen wholly to politics. His most recent work, The Life and Death of the Duc de Berry, is written completely in the style of the panegyrists of Louis XIV.

Monsieur de Chateaubriand is of quite a modest and yet slender stature. His oval face bears an expression of piety and melancholy. He has dark hair and eyes: the latter shine with the light of his spirit which reveals itself in his features.’

But I have white hair; moreover I am more than a century old, I am dead: so forgive Madame the Baroness von Hohenhausen for having sketched me in my prime, though she already grants me my years. The portrait is, moreover, very kind; but I owe it to truth to say that it is no good likeness.

Book XXVI: Chapter 2: Ministers and Ambassadors – History of the Court and society

BkXXVI:Chap2:Sec1

The house Under the Lindens, Unter den Linden, was far too large for me, cold and dilapidated: I occupied only a small corner.

Among my colleagues, the Ministers and Ambassadors, the only remarkable person was Monsieur d’Alopeus. I have since met his wife and daughter again, in Rome, with the Grand-Duchess Helène: I would have been happier if the latter had been in Berlin instead of the Grand-Duchess Nicholas, her sister-in-law.

Monsieur d’Alopeus, my colleague, had the pleasant conviction of believing himself adored. He was persecuted by the passions which he inspired: ‘By my faith,’ he said to me, ‘I have no idea what power it is that I possess; but wherever I go women pursue me. Madame d’Alopeus is quite dedicated in her attachment to me.’ He had been a convinced Saint-Simonian. Private society, like public society, has its charms: in the former, there are relationships forever being forged and broken, family matters, deaths, births, particular joys and sorrows; all varying in character according to the age. In the latter, there are governments forever changing, battles lost or won, negotiations with the court, kings who pass by, and kingdoms that fall.

Under Frederick II, Elector of Brandenburg, nicknamed Iron Tooth; under Joachim II, who it was claimed was poisoned by Lippold of Prague; under John Sigismund, who brought his Electorate the Duchy of Prussia; under George William, the Irresolute, who, while losing his fortresses, left Gustavus-Adolphus conversing with the ladies of his court, and said: ‘So what? We have cannon’; under the Great-Elector, who throughout his States found only heaps of ash that kept the grass from growing, who gave an audience to the Ambassador from Tartary, whose interpreter had a wooden nose and cropped ears; under his son, the first King of Prussia, who, woken suddenly by his wife, took a fever from the fright and died of it; under all these rulers, various memoirs allow us simply to witness a repetition of similar events in private society.

Frederick-William I, the father of Frederick the Great, a strange and harsh individual, was raised by Madame de Rocoules, the refugee: he loved a young woman who could not improve him; he retreated to his smoking-room. He named Gundling, the buffoon, President of the Royal Academy in Berlin; he imprisoned his son in the citadel of Custrin, and Katte had his head removed in the presence of the young prince; that was the private life of that age. Frederick the Great, when he came to the throne, had an intrigue with an Italian dancer, La Barbarini, the only woman he ever showed an interest in: he was content to play the flute on his wedding night beneath the window of his bride Elizabeth of Brunswick. Frederick had a taste for music, and a mania for verse. The intrigues and epigrams of the two poets, Frederick and Voltaire, troubled Madame de Pompadour, the Abbé de Bernis, and Louis XV. The Margrave of Bayreuth was amorously involved in it all, as much as one can be with a poet. The literary circles around the King, the greyhounds on filthy armchairs; the concerts in front of statues of Antinous; the grand dinners; the bouts of philosophy; freedom of the press and strokes of the birch; then the lobster or eel pie which ended the life of a grand old man, who wanted to live: these are the matters that occupied the private lives of that age of letters and battles. – And, Frederick, nevertheless remodelled Germany, created a counter-weight to Austria, and altered all the political interests and relationships within the country.

In the next reign we find the Marble Palace; Madame Rietz and her son, Alexander, the Graf von der Mark; ‘Baroness’ Stolzenberg, Mistress of the Margrave Schwed, a former actress; Prince Henry and his suspect friends; Mademoiselle Voss, Madame Rietz’s rival; an intrigue at a masked ball between a young Frenchman and the wife of a Prussian general; and finally Madame de F., whose adventures you can read of in the Secret History of the Court of Berlin; who recalls all those names? Who will remember ours? Now, in the Prussian capital, only a few octogenarians preserve the memory of that past generation.

Book XXVI: Chapter 3: William Humboldt – Adelbert de Chamisso

BkXXVI:Chap3:Sec1

The habits of Berlin society suited me: between five and six one went out for the evening; all was over by nine, and I slept right through as if I were not an Ambassador. Sleep consumes existence: that is what is fine about it: ‘Time is long, and life is short’, said Fénelon. William von Humboldt, brother of my illustrious friend Baron Alexander, was in Berlin: I knew him as a Minister in Rome; under suspicion, as far as government was concerned, because of his opinions, he led a retired life; to kill time he studied all the world’s languages and even dialects. He rediscovered peoples, ancient inhabitants of the earth, by means of the geographical denominatives of countries. One of his daughters spoke ancient and modern Greek equally well: if one came upon him on the right day, one could converse at dinner in Sanskrit.

Adelbert de Chamisso was housed in the Botanical Gardens, at some distance from Berlin. I visited him in that solitude where the plants were freezing in the greenhouses. He was tall, of a very handsome figure. I felt an attraction to this traveller, exiled like myself: he had seen those polar seas I had hoped to penetrate. An émigré, as I had been, he had been brought up in Berlin as a page. Adelbert, travelling through Switzerland, stopped for a moment at Coppet. He found himself one of a party on the lake, where he thought he would perish. He wrote that very day: ‘I see clearly that I must seek my salvation on the great waters.’

‘Adelbert de Chamisso’

Edvard Grieg Archives

Bergen Public Library, Norway

Monsieur de Chamisso had been nominated by Monsieur de Fontanes as a professor at La Roche-sur-Yon, then as professor of Greek at Strasbourg; he refused the offer with these noble words: ‘The primary condition required, for work in instructing the young, is freedom: though I admire Bonaparte’s genius, it would not suit me.’ He refused likewise the benefits offered him under the Restoration: ‘I have done nothing for the Bourbons’, he said, ‘and I cannot receive a reward for the blood and service of my forefathers. In this age every man must achieve things for himself.’ In Monsieur Chamisso’s family they preserve this note, written in the Temple, by Louis XVI himself: ‘I recommend Monsieur de Chamisso, one of my loyal servants, to my brothers.’ The royal martyr had hidden this note in his shirt so that it would be given to his senior page, Hippolyte Chamisso, Adelbert’s eldest brother.

Perhaps the most moving work of this child of the Muses, concealed beneath foreign arms and adopted by German bards, are these lines which he first penned in German and translated into French verse, about the Château de Boncourt, his paternal hearth:

‘Weighed down by my white hair;

I still dream of my early life;

You pursue me, image so fair,

Renewing beneath Time’s scythe.

From the depths of an emerald sea

Rose that noble château of ours,

I recall its roof high above me,

With its crenellated towers;

Those lions on our coat of arms,

Still show their kindly gaze,

I smile at you, beloved guards;

And hurl myself through the maze.

There’s the sphinx of the fountain,

There’s the fig tree growing green;

There, the vain shadow blossomed

Of a child’s first poetry.

I search for, and I see again

My grandfather’s chapel tomb;

There his weapons hang in array.

On their pillar, in the gloom.

That marble the sunlight gilds,

Those sacred characters too,

No, I cannot see them still,

A veil of mist clouds my view.

My forebears’ trusted domain

Within me alone, you renew!

Proud, nothing of you remains,

the plough has passed over you!...

Be fertile, my cherished land,

I bless you, with heart at rest;

Bless, as he may, the ploughman,

Whose blade furrows your breast.’

Chamisso blesses the farmer who ploughs the furrow of which he himself has been despoiled; his soul must have inhabited the regions where my friend Joubert soared. I regret Combourg, and with less resignation, even though it may not have left my family. Embarking on a vessel provided by Count Romanzov, Monsieur de Chamisso with Captain Kotzebue discovered the straight to the east of the Behring Strait, and gave his name to one of the islands from which Cook glimpsed the coast of America. On Kamchatka, he discovered a portrait of Madame Récamier on porcelain, and his own little tale of Peter Schlemihl, translated into Dutch. Adelbert’s hero, Peter Schlemihl, sold his soul to the devil: I would have preferred to sell him my body.

I remember Chamisso like the faint breeze which lightly swayed the stems of the bushes I passed through as I returned to Berlin.

Book XXVI: Chapter 4: Princess William – The Opera – A concert

BkXXVI:Chap4:Sec1

Following a ruling of Frederick II, the Princes and Princesses of the bloodline in Berlin did not mix with the diplomatic corps; but, thanks to the carnival, to the marriage of the Duke of Cumberland with Princess Frederica of Prussia, sister of the late queen, thanks also to a certain relaxation of etiquette which, it was said, was allowed because of who I was, I had occasion to find myself among the royal family more often than my colleagues. As I visited the great palace from time to time, I encountered the Princess William: she was so kind as to conduct me through the apartments. I have never seen a sadder look than hers; in the inhabited rooms at the rear of the palace, overlooking the Spree, she showed me a chamber haunted at certain times by a lady in white, and, huddling against me in positive fright, she looked like that pale lady. For her part, the Duchess of Cumberland told me that she and her sister the Queen of Prussia, while they were both very young, had heard their mother who had just died speaking to them from behind her closed curtains.

The King, into whose presence I fell on emerging from my tour of the curiosities, led me to his oratory: he drew my attention to the crucifix and the paintings, and gave me the credit for these innovations because, as he told me, having read in Le Génie du Christianisme that the Protestants had stripped their religion bare, he had found my comment just: he had not yet attained his excesses of Lutheran fanaticism.

At the Opera in the evenings I had a box near the Royal box, facing the stage. I chatted to the Princesses; the King went outside in the intervals; I met him in the corridor, he looked to see if there was anyone about and whether anyone could hear us; then he confessed to me in a low voice his hatred of Rossini and his love for Gluck. He elaborated his lament on artistic decadence and especially those gargled notes destructive of dramatic singing: he confided in me that he only dared say this to me, because of the people who surrounded him. Seeing someone coming, he hastened back to his box.

‘Opera Platz, Berlin’

Asher's Picture of Berlin and its Environs - Adolph Asher (p28, 1837)

The British Library

I saw Schiller’s Joan of Arc performed: Rheims Cathedral was imitated perfectly. The King, serious in his beliefs, only tolerated representation of the Catholic religion, in the theatre, with pain. Monsieur Spontini, the author of La Vestale, was the director of the Opera-House. Madame Spontini, the daughter of Monsieur Érard, was very pleasant but she seemed to be atoning for female volubility by the slowness with which she spoke: each word was divided into separate syllables as it expired on her lips; if she had wished to say: I love you, a Frenchman’s amorousness might well have vanished between the beginning and end of the three words. She could never complete my name, and failed to end it not without a certain grace.

A public concert took place two or three times a week. In the evening, on returning from work, young working-class girls, baskets under their arms, and young workmen carrying the tools of their trade, pushed pell-mell into a room; on entering they were given a music sheet, and they joined the mass choir with astonishing precision. It was somehow amazing that these two or three hundred voices blended together. When the piece was finished, each took their way home again. We are far from that sense of harmony, a powerful means of civilisation; it has brought to the peasant cottages of Germany an education lacking to our farm workers: everywhere there is a piano there is an end to coarseness.

Book XXVI: Chapter 5: My first despatches – Monsieur de Bonnay

BkXXVI:Chap5:Sec1

Around the 13th of January, I began my series of despatches to the Foreign Minister. My mind submits easily to this kind of task: why not? Were not Dante, Ariosto and Milton as successful in politics as in poetry? Doubtless I was no Dante, Ariosto, or Milton; Europe and France did see what I could achieve however in my Congress of Verona.

My predecessor in Berlin had dealt with me in 1816 as he had dealt with Monsieur Lameth, in a little poem at the beginning of the Revolution. When one is as amiable as that, it does not do to leave files behind or to show a clerk’s correctness when one lacks the ability of a diplomat. It might happen, in the age in which we live, that a gust of wind blows someone you have spoken against into your role; and as the first duty of an ambassador is to study the embassy archives, that is where he will come across letters as they fell from the master’s hand. What can one expect? Those profound minds, who laboured for the success of the true cause, could not think of everything.

EXTRACTS FROM MONSIEUR DE BONNAY’S FILES

No. 64 ‘22nd of November 1816.

The words the King addressed to the new Cabinet, formed from the Chamber of Peers, are known and approved of throughout Europe. I have been asked how it is possible that men devoted to the King, people attached to his person and occupying places in his household, or in those of our Princes, could indeed have cast their votes for Monsieur de Chateaubriand’s entry to the secretariat. My response was that the ballot was a secret one, and that no one could know how individuals voted. “Ah!” exclaimed a notable person, “if the King could only be assured of that, I think access to the Tuileries would quickly be denied such disloyal servants.” I thought I should say nothing, and I did so.’

‘15th of October 1816.

It will be the same with the measure of the 5th as with that of the 20th of September, Monsieur le Duc: in Europe both merely meet with approval. But what is astonishing, is to see the purest and worthiest of Royalists continuing in their passion for Monsieur de Chateaubriand, despite the publication of a pamphlet which claims in principle that the King of France, by virtue of the Charter, is simply a moral being, essentially null, and devoid of his own will. If anyone other than he had advanced a similar proposition, that man would, not without reason, have been considered a Jacobin.’

See how surely I am put in my place. Moreover it is a good lesson; it teaches us to close our ears, in learning what will be thought of us later.

Reading the despatches of Monsieur de Bonnay and those of other ambassadors of the old regime, it seemed to me that their despatches dealt less with political matters than with anecdotes relating to people in society and at Court: they reduced themselves to being diaries of praise like Dangeau’s or of satire like Tallemant’s. Louis XVIII and Charles X too would have much preferred my colleagues’ amusing letters to my serious correspondence. I could have laughed and mocked like my predecessors; but the age when foreign affairs involved scandalous adventures and petty intrigues had passed. What benefit would a portrait of Monsieur Hardenberg have been to my country, an old man white as a swan, deaf as a post, going off to Rome without permission, amusing himself far too much, believing in all sorts of fantasies, delivered up finally to magnetism at the hands of Doctor Koreff, whom I met in remote places trotting his horse between the devil, medicine and the Muses?

This contempt for frivolous correspondence made me write to Monsieur Pasquier in my letter of 13th February 1821 no. 13:

‘I have not spoken to you, Monsieur le Baron, as is usual, of receptions, balls, plays, etc.; I have sent you no little pen-portraits or vain satires; I have tried to rid diplomacy of gossip. The reign of the commonplace returns when extraordinary times have passed: now it is only necessary to depict what ought to be and to attack what threatens.’

Book XXVI: Chapter 6: The Park – The Duchess of Cumberland

BkXXVI:Chap6:Sec1

Berlin has left me with one lasting memory, because the nature of the recreations I found there recalled my childhood and youth; except that real princesses fulfilled the role of my Sylph. The aged crows, my eternal friends, came to perch on the lime trees in front of my window; I threw them food: with unimaginable dexterity, if they seized too large a piece of bread, they would drop it in order to seize a smaller piece; so that they could take another a little larger, and then another in succession till they seized an ultimate piece, which, being at the end of their beak, forced it to remain open, without any of the intervening layers of food falling. Their meal done, the birds sang after their fashion: cantus cornicum ut saecla vetusta: the sound of crows like the centuries past. I wandered through the empty wastes of a frozen Berlin; but I did not hear the lovely voices of young girls rise from its walls as they did from the ancient walls of Rome. Instead of Capuchins with white beards dragging their sandals through the flowers, I met soldiers rolling snowballs.

One day, on a round of the outer walls, Hyacinthe and I found ourselves faced by an east wind so piercing that we were obliged to run through the fields and regain the city half-dead. We crossed fenced ground, and all the guard dogs snapped at our heels and tore after us. The thermometer that day dropped to 22 degrees (Réamur) below freezing. A couple of the sentries at Potsdam were frozen.

On the far side of the park was an old abandoned pheasant covert – the Prussian Princes did not shoot. I crossed a little wooden bridge over a canal running into the Spree, and found myself among trunks of fir trees which formed a portico to the covert. A fox, reminding me of those in the avenue at Combourg, emerged from a hole made in the wall of the reserve, came to ask my news then retreated into his copse.

What they call the park, in Berlin, is a wood of oak-trees, silver birch, beech, lime and Dutch poplars. It is situated at the Charlottenburg Gate and is crossed by the high-road which leads to that Royal residence. On the right of the park, is the Field of Mars; on the left, various little restaurants.

Within the park, which was not at that time pierced by regular alleyways, one discovered meadows, wild places and beech-wood benches on which German youth had formerly etched, with a knife, hearts pierced by daggers: beneath these pierced hearts one read the name Sand. Flocks of crows, living in trees approaching spring, began to call. Animal nature revived before vegetable nature: and the frogs, black all over, were consumed by ducks, in the waters which here and there were free of ice: the nightingales there, announced springtime in the woods of Berlin. However the park did not lack for attractive creatures; squirrels scampered among the branches or played on the ground, waving their tails like flags. When I approached the festivities, the actors fled up the trunks of the oak-trees, halting in a fork to grumble as they watched me pass beneath them. Few strollers frequented the plantation whose uneven ground was lined and cut by canals. Sometimes I encountered a gouty old officer who said to me, warmly in his delight, speaking of the pale ray of sunlight in which I shivered: ‘It’s breaking through!’ From time to time I met the Duke of Cumberland, on horseback and almost blind, halted by a Dutch poplar against which he had just banged his nose. One or two six-horse carriages passed: they carried the Ambassadress of Austria, or the Princess de Radzivill and her daughter, aged fifteen, delightful as one of those nudes with virgin faces which surround Ossian’s moon. The Duchess of Cumberland took the same direction with me almost every day: now she would be off to a cottage to help a poor woman of Spandau, now she would stop to tell me graciously that she had hoped to meet me; a delightful daughter of royalty, descending from her car like the goddess of night to wander through the forests! I also saw her at home; she repeatedly told me that she wished to entrust her son to me, that little George who became the Prince whom his cousin Victoria, they say, would have wished at her side when she became Queen of England.

Princess Frederica, has since walked, in her days on the banks of the Thames, in those gardens at Kew which once witnessed my wanderings, between my two acolytes, illusion and poverty. After my departure from Berlin, she honoured me with her correspondence; she depicted hour by hour the life of an inhabitant of those heaths where Voltaire walked, where Frederick died, where that Mirabeau hid who was to begin the Revolution of which I was a victim. The mind is captivated by perceiving the links which connect so many men who remain unknown to one another.

Here are a few extracts from the correspondence which commenced between me and the Duchess of Cumberland:

‘19th of April, Thursday.

This morning, when I woke, I was brought the last witness of your memory of me; later I passed by your house, I saw the windows open as usual; all was in its place, except you! I cannot express to you how it afflicted me! I no longer know where to locate you; each instant you are more distant; the only fixed point is the 26th, the day when you expect to arrive, and the memory of you which I retain.

God willing you will find all changed for the better, for you and for the common good! Accustomed to sacrifice, I will even bear that of never seeing you again, if it is for your good and that of France.’

‘22nd.

Since Thursday, I have passed your house every day to go to church; I prayed deeply on your behalf. Your windows are constantly open, that affects me: who is it who has the thoughtfulness to follow your orders and tastes, despite your absence? It makes me think, sometimes, that you have not left; that business detains you, or that you wished to brush away bothersome things in order to finish things at your ease. Do not take that as a reproach: it’s the only way; but if that is the case, confide it to me.’

‘23rd.

Today the heat is so prodigious, even in church, that I could not take my walk at the usual time: it’s all the same to me at present. The dear little wood no longer charms me, everything bores me! This sudden alteration from cold to heat is common in the north; the inhabitants do not take after the climate in their control over their character and feelings.’

‘24th.

Nature is much more beautiful; all the leaves have emerged since your departure: I wish they could have arrived a few days earlier, so that you could have taken away a more radiant image of your stay here.’

‘Berlin, 12th of May 1821.

God be thanked, at last there is a letter from you! I know you could not write to me earlier; but, despite all the calculations my mind made, three weeks, or should I say rather twenty-three days, is a long time for friendship to endure, and to be without news resembles the saddest of exiles: yet memory and hope remained with me.’

‘15th of May.

It is not from the stirrup, like the Grand Turk, but always from my bed that I write to you; but this retreat gives me the time to reflect on the new regime that you wish to insist on regarding Henri V. I am pleased with it; roast lion will only do him good; I merely advise you to start with the heart. You will have to feed lamb to your other pupil (George) so he does not play the devil too much. It is essential that this plan of education be realised and that Georges and Henri become good friends and allies.’

Madame the Duchess of Cumberland continued to write to me of the waters at Ems, then the waters of Schwalbach, and after that Berlin, to which she returned on the 22nd of September 1821. She wrote from Ems: ‘The coronation in England will take place without me; I am upset that the king has decided on the saddest day of my life for his crowning; that on which I saw my beloved sister (the Queen of Prussia) die. Bonaparte’s death has also made me think of the suffering he caused her.’

‘From Berlin, 22nd September.

I have already seen those great solitary alleys again. How indebted I shall be to you, if you send me as you promised the lines you have written on Charlottenburg! I have also made my way once more to the cottage in the wood where you had the goodness to help me in assisting the poor woman of Spandau; how good you are to remember her name! You recall happy times to me. It is nothing new to regret happiness.

At the moment when I was about to send this letter, I learnt that the King has been detained at sea by storms, and probably driven to the Irish coast; he had not arrived at London on the 14th; but you will know of his return before us.

Poor Princess William today received sad news of the death of her mother, the Dowager Landgraf of Hesse-Homburg. You see how I speak to you of all that concerns our family; Heaven send that you have better news to give me!’

Does it not seem when the sister of the lovely Queen of Prussia speaks of our family as if she did me the kindness of speaking about my grandmother, my aunt and my obscure relatives at Plancoët? Did the French Royal family ever honour me with a smile compared with that of this foreign Royal family, who hardly knew me and owed me nothing? I suppress several other affectionate letters: they contain elements of suffering and contentment, resignation and nobility, the familiar and the elevated: they serve to counterbalance whatever I have said, perhaps too harshly, about the race of kings. A thousand years ago, and Princess Frederica as a daughter of Charlemagne would have carried Eginhard at night on her shoulders, so that he might leave no trace on the snow.

I have just re-read this chapter in 1840: I cannot prevent myself from being struck by the continuing romance of my life. So many paths missed! If I had returned to England with little George, the potential heir to the Crown, I should have seen any new dream of changing my country vanish, just as, if I had not married, I would have remained from the very first in the land of Shakespeare and Milton. The young Duke of Cumberland, who has also lost his sight, did not marry his cousin the Queen of England. The Duchess of Cumberland has become the Queen of Hanover: where is she? Is she happy? Where am I? Where is my King? God willing, in a few years time I shall no longer have to cast my eyes over my past life, nor ask myself those questions. But it is impossible for me not to pray Heaven to shed its favour on Princess Frederica’s last years.

Book XXVI: Chapter 7 – My despatches, continued

BkXXVI:Chap7:Sec1

I had only been sent to Berlin with an olive branch, and because my presence was a nuisance to the administration; but, knowing the inconstancy of fortune, and feeling that my political role was not complete, I kept an eye on events: I did not wish to desert my friends. I soon saw that the reconciliation between the Royalist party and the Ministerial party lacked sincerity; mistrust and prejudice remained; I was not dealt with as they had promised: they began to attack me. The entry to the Cabinet of Messieurs Villèle and Corbière excited the jealousy of the extreme right; it no longer marched beneath the banner of the former, and he, ambitiously impatient, became frustrated. We exchanged a few letters. Monsieur de Villèle regretted entering the Cabinet: he was wrong, and the proof that I had foreseen things correctly was that less than a year went by before he became Finance Minister and Monsieur de Corbière took the Interior Ministry.

I explained myself to Monsieur le Baron Pasquier also; on the 10th of February 1821 I wrote to him:

‘I learn from Paris, Monsieur le Baron, by the courier who arrived on the morning of the 9th of February, that it is claimed, wrongly, that I wrote from Mainz to the Prince de Hardenberg, or even that I sent a courier to him. I did not write to Monsieur de Hardenberg and even less did I send him a courier. I request, Monsieur le Baron, to be spared these machinations. If my services should prove no longer acceptable, it would give me no greater pleasure than to be told so quite openly. I neither solicited nor desired the mission with which I am charged; I have accepted an honourable exile neither from taste nor choice, but only for the good of harmony. If the Royalists have rallied to the Government, the Government knows that I have had the pleasure of contributing to that reconciliation. I would have some right to complain. What has been done for the Royalists since my departure? I have not ceased to write on their behalf: has anyone listened to me? Monsieur le Baron I have, by the grace of God, other things to do in life than to attend grand balls. My country requests my presence, my sick wife has need of my care, my friends ask for their guide. I am above or below the level of an Ambassador, and the same goes for Minister of State. You have no lack of men more skilful than I am in conducting diplomatic affairs; thus it would be useless to search for pretexts to quarrel with me. I can understand without having to have things spelt out; and you will find me ready to re-enter my previous obscurity.’

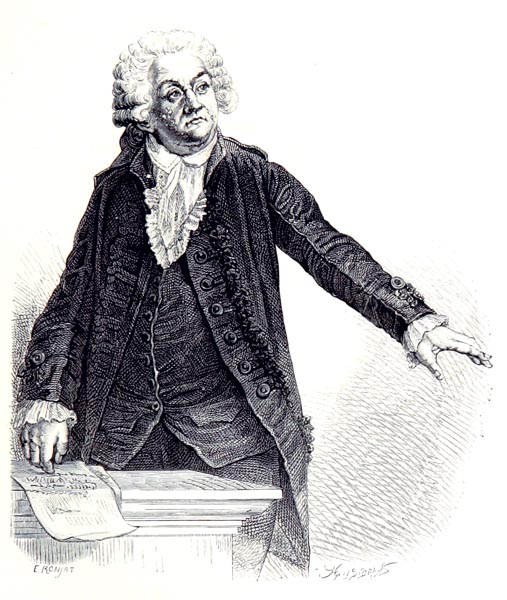

‘Portrait of Pasquier’

François-Séraphin Delpech (French, 1778 - 1825). After: Antoine Maurin (French, 1793 - 1860)

Yale University Art Gallery

All this was sincerely said; the ability to drive things home, and regret nothing, would have been of great use to me, if I had possessed some ambition.

MY DESPATCHES CONTINUED

My diplomatic correspondence with Monsieur Pasquier took its course: continuing my pre-occupation with the affair at Naples, I wrote:

‘Nos. 15 and 16 20th of February 1821

‘Austria is rendering a service to all monarchies by destroying the edifice of Jacobinism in the Two Sicilies; but she will lose the support of those monarchies if the result of a salutary and necessary expedition is the conquest of a province or the oppression of a people. It is necessary to free Naples from demagogic independence and establish monarchical liberty; break their shackles, not bring them chains. But Austria does not want a constitution for Naples: what will she give them? Men? Where are they? It only needs a liberal priest and two hundred soldiers to begin it again.

After occupation, voluntary or forced, you should intervene to establish a constitutional government in Naples under which all social freedoms can be respected.’

I had always retained in France a weight of opinion which obliged me to keep an eye on the interior. I dared to submit this plan to my Minister:

‘To definitely adopt a Constitutional form of government.

To introduce a septennial renewal with no intention of retaining any of the actual Chamber; a move which would be suspected; nor of retaining it all which would prove dangerous.

To renounce extra-ordinary laws, which are the source of arbitrariness, and an endless subject of quarrels and calumnies.

To free the districts from Ministerial despotism.’

In my despatch of the 3rd of March, no. 18, I returned to the question of Spain; I wrote:

‘It would be possible for Spain to speedily change its monarchy into a republic: its constitution ought to bear fruit. The King will flee, or be killed or deposed; he is not strong enough to take a grip on revolution. It is yet possible that Spain might remain for some time under popular rule, if it is organised into a federal republic, for the aggregation of which it is more suitable than any other country by reason of the diversity of its kingdoms, its manners, its laws and even its language.’

The affair at Naples appears two or three times. I observed (6th of March, no. 19):

‘That the Legitimacy has been unable to put down deep roots in a State which has so often changed ownership, and whose customs have been overthrown by so many revolutions. Affection has not had time to be born, habits to receive the uniform imprint of centuries and institutions. There are many corrupt or savage men among the Neapolitans who have no relationship with each other, and who are only weakly attached to the Crown: royalty is too close to beggary and too far from being Calabrese to be respected. To establish democratic freedom, the French had to show too much military ability; the Neapolitans will not show enough.’

Finally, I said a few words again about Portugal and Spain.

The rumour had spread that John VI of Braganza had embarked at Rio de Janeiro for Lisbon. It was an irony of fate worthy of our age that a King of Portugal should go to seek shelter from a South American revolution beneath a European one, while passing the base of a rock which had held the conqueror who had forced him to take refuge in the New World.

‘The worst is to be feared regarding Spain,’ I wrote (17th of March, no. 21); the Peninsular revolution will run in cycles, unless someone lifts an arm capable of halting it; but where is that arm? That is forever the question.’

That arm I had the honour of discovering in 1823; it was that of France.

I discover once more with pleasure, in this passage of my despatch of the 10th of April, no. 26, my antipathetic jealousy against the allies and my preoccupation with the dignity of France; I said apropos of Piedmont:

‘I do not fear a prolongation of the troubles in Piedmont given their immediate outcome; but they may produce a deferred evil in motivating military intervention by Austria and Russia. The Russian army is continually on the move and has received no counter-orders.

Consider if, in that case, it would not be better for the safety and dignity of France to occupy Savoy with twenty-five thousand men, while Russia and Austria are occupying Piedmont. I am convinced that such an action, vigorously conducted and politically strategic, flattering to French pride, would by that alone gain great popularity and bring infinite honour to the ministers concerned. Ten thousand Royal Guardsmen and a selection of the rest of our troops will easily create for you an army of twenty-five thousand excellent and loyal soldiers: the white cockade will be assured of success when it faces the enemy once more.

I feel, Monsier le Baron, that we should avoid wounding French self-esteem and that the dominance of the Russians and Austrians in Italy ought to arouse our national pride; but we have an easy means of satisfying it, which is to occupy Savoy ourselves. The Royalists would be delighted and the liberals could only applaud if they saw us adopting an attitude worthy of our might. We would have at the same instant the pleasure of wiping out a demagogic revolution and the honour of re-establishing the superiority of our arms. It would be to greatly misunderstand the French spirit if we feared to assemble twenty-five thousand men to march into a foreign country, and rank ourselves alongside the Russians and Austrians as a military power. I would answer for the outcome with my head. We may have stayed neutral in the Naples affair: can we do so in safety and with glory where the disturbances in Piedmont are concerned?’

Here all my method is revealed: I was a Frenchman; I had my settled political views well before the Spanish War, and I glimpsed how the responsibility of success, if I obtained it, might weigh on my head.

All I recall here is doubtless of interest to no one; but such is the inconvenience of Memoirs: when there are no historical facts to record, they only tell you about the author, and stupefy you. Leave these forgotten shades alone! I prefer to recall that Mirabeau, as yet unknown, fulfilled a secret mission in Berlin in 1786, and was obliged to train a pigeon to send news to the King of France of the Mighty Frederick’s last sighs.

‘I was in some perplexity,’ Mirabeau writes, ‘I was certain that the gates of the city were closed; it was even possible that the bridges from the island of Potsdam had been raised as soon as the event occurred, and in that case things might remain in a state of uncertainty for as long as the new King wished. Given the first supposition, how could a courier leave? There was no way of scaling the ramparts or the palisades, without exposing oneself to a challenge; the sentries forming a chain every forty paces behind the palisade, and every sixty paces behind the walls, what to do? Had I been the Ambassador, the certainty that the symptoms were mortal would have encouraged me to send a despatch before he died, since what more can the word dead deliver? In my position what ought I to do? Whatever it might be, the most important thing was to be of service. I had good reason to be wary of the activities of our embassy. What should I do? I sent a reliable man on a lively and vigorous mount four miles out of Berlin, to a farm, from whose pigeon-loft I had acquired some days ago two pairs of pigeons, whose ability to return had been proven, so that unless the bridges of the island of Potsdam had not been raised, I was sure of my actions.

I decided then that we were not rich enough to throw a hundred louis out of the window; I renounced all my fine preparations that had cost me an amount of thought, activity, and louis, and I released my pigeons with the word home. Did I do right? Did I do wrong? I do not know; but I had no express orders, and people are sometimes less than grateful when one does more than one’s duty.’

‘Mirabeau’

L'Histoire de France Depuis 1789 Jusqu'en 1848, Racontée à mes Petits-Enfants, par M. Guizot. Leçons Recueillies par Madame de Witt, Vol 01 - François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (p59, 1878)

The British Library

Book XXVI: Chapter 8 – A memoir I started: on Germany

BkXXVI:Chap8:Sec1

During their sojourn in foreign parts, ambassadors were encouraged to write a memoir on the state of the nations and governments to which they were accredited. This spate of memoirs may prove useful historically. Nowadays the same injunction is made, but hardly any diplomatic agents submit one. I have been too brief a resident in my embassies to finish any lengthy studies; nevertheless, I have outlined some; my patient work has not been totally sterile. I found this sketch of my research on Germany which I began there:

‘After the fall of Napoleon, the introduction of representative government to the German Confederacy re-awoke in Germany those first innovative ideas that the Revolution had originally given birth to there. They fermented there often violently: youth was summoned to the country’s defence by the promise of liberty; that promise was avidly received by the students who discovered in their teachers the tendency to support liberal theory that science has posessed in this century. Under German skies, that love of liberty became a kind of fanaticism, sombre and mysterious, propagating itself by means of secret societies. Sand frightened Europe. That man, however, who revealed a powerful sect, was only a vulgar enthusiast; he erred, and mistook the commonplace spirit for a transcendental one: his crime will be forgotten as that of a scribbler whose genius could not rise to empire, and who had too little of the king and conqueror to be worthy of a dagger blow.

A kind of political tribunal of inquisition, and the suppression of freedom of the Press, has arrested that movement of minds; but one should not believe it has broken the spring of action. Germany now, like Italy, desires political unity, and with that idea, which stays dormant for a shorter or longer period of time depending on men and events, they will always be able, in waking it, to stir the Germanic peoples. The Princes or Ministers who may appear in the ranks of the Confederation of German States will hasten or retard the revolution in that country, but they will not stop the human race from developing: each century takes it own course. Today there is no one of note in Germany, nor even in Europe: we have passed from giants to dwarfs, and fallen from immensity into the narrow and limited. Bavaria, because of the government created by Monsieur de Montgelas, still promotes new ideas, though it went backwards as long as the Landgraviat of Hesse-Kassel refused to admit there had been a European Revolution. The Prince, who has just died, wished his soldiers, formerly soldiers of Jérôme Bonaparte, to wear powder and queues; he mistook the old fashions for the old ways, forgetting that one can copy the former, but can never bring back the latter.’

Book XXVI: Chapter 9 – Charlottenburg

BkXXVI:Chap9:Sec1

In Berlin, and in the North generally, monuments are fortresses; their aspect alone grips the heart. When one finds these buildings on fertile inhabited terrain, they give birth to the idea of legitimate defence; women and children sitting and playing some way from these sentinels, contrast pleasantly enough with them; but a fortress on heath-land, in a waste, only brings to mind human wrath: against whom are they raised these ramparts, if not against poverty and freedom? You need to be me, to find any pleasure in roaming around at the foot of those bastions, listening to the gusts of wind in the ditches, in sight of those parapets raised in expectation of enemies who might never appear. Those military labyrinths, those silent guns facing each other at the angles of grassy salients, those sentries of stone where one sees no one and from which no eye looks out at you, are of an unbelievable gloominess. If, in the twin solitude of nature and war, you find a daisy sheltering beneath the slope of a field-work, that gift of Flora refreshes you. When, in Italian castellos, I glimpsed she-goats clinging to the ruins, and the goat-girl sitting under a pine tree for a parasol; when, on the medieval walls that encircle Jerusalem, my gaze plunged into the valley of the Cedron and fell on Arab women clambering up the escarpments among the stones; the spectacle was sad no doubt, but history was there and the silence of the present merely allowed me to hear the noise of the past more clearly.

‘Charlottenburg’

Asher's Picture of Berlin and its Environs - Adolph Asher (p99, 1837)

The British Library

I asked for leave on the occasion of the baptism of the Duc de Bordeaux. The request having been granted, I prepared to depart: Voltaire, in a letter to his niece, said that he was watching the Spree flow, that the Spree ran into the Elbe, the Elbe into the sea, and the sea received the Seine; thus he was heading towards Paris. Before leaving Berlin, I made a last visit to Charlottenburg: it was not Windsor, Aranjuez, Caserta, or Fontainebleau: the villa, attached to a hamlet, is surrounded by an English park of small extent from which one can see the fallows beyond. The Queen of Prussia enjoyed a peace here which the memory of Bonaparte could no longer disturb. What a row that exterminator once made in that sanctuary of silence, when he appeared there with his fanfares and his legions blood-stained from Jena! It was from Berlin, having wiped Frederick the Great’s kingdom from the map, that he denounced the Continental blockade and planned the Moscow Campaign in his mind; his words had already brought death to the heart of an accomplished Princess: she sleeps now at Charlottenburg, beneath a mausoleum; a tomb with her fine statue in marble, represents her. I made these verses about the tomb at the request of the Duchess of Cumberland:

THE TRAVELLER

Under the tall pines who guards these springs,

Say, keeper, this new monument’s for whom?

THE KEEPER

One day ‘twill mark for you the end of things:

Oh traveller, it is a tomb!

THE TRAVELLER

Who lies here?

THE KEEPER

A thing once full of charm.

THE TRAVELLER

That someone loved?

THE KEEPER

Who was adored.

THE TRAVELLER

Open then.

THE KEEPER

Enter not, if you fear the harm

Tears bring.

THE TRAVELLER

I have often wept before.

From Greece or Italy

They stole this marble for a sepulchre;

What tomb released it to enchant us here?

Cornelia’s perhaps or Antigone’s?

THE KEEPER

The beauty whose image stirs your words

spent her whole life among these trees.

THE TRAVELLER

Who then amidst these marble-clad walls

hung those faded crowns for her, in a row?

THE KEEPER

The beautiful children who with all

her virtues were crowned here below.

THE TRAVELLER

Someone comes.

THE KEEPER

A husband: this way he’ll often go,

Nurturing his sad private memories.

THE TRAVELLER

He lost all then?

THE KEEPER

No: his throne he keeps.

THE TRAVELLER

A throne cannot console.

Book XXVI: Chapter 10 – The interval between my Berlin and London Embassies – The baptism of Monsieur le Duc de Bordeaux – A letter to Monsieur Pasquier – A letter from Monsieur de Bernstorff – A letter from Monsieur Ancillon – A last letter from Madame the Duchess of Cumberland

Paris, 1839

BkXXVI:Chap10:Sec1

I arrived in Paris at the moment of celebration for the baptism of Monsieur le Duc de Bordeaux. The cradle of that scion of Louis XIV, which I had the honour of paying carriage for, has vanished like that of the King of Rome, though the latter cradle was attached to a spear-head in order to be hurled to the other side of the river where we shall all land. In another age than ours, Louvel’s terrible deed would have guaranteed Henri V the sceptre; but crime no longer confers rights except on the man who commits it.

After the baptism of Monsieur le Duc de Bordeaux, I was at last reinstated as a Minister of State: Monsieur de Richelieu had taken away, Monsieur de Richelieu now gave; the reparation was no more agreeable to me than the wrong wounded me.

While I was flattering myself that I would be off to see my crows again, the deck was shuffled: Monsieur de Villèle stood down. Out of loyalty to my friends and my political principles, I thought it necessary to resign with him. I wrote to Monsieur Pasquier:

‘Paris, 30th of July 1821.

Monsieur le Baron,

When you had the kindness to invite me to your residence on the 14th of this month it was to tell me that my presence in Berlin was essential. I had the honour to reply that it appeared as if Messieurs de Corbière and Villèle would resign from the government, and that my duty was to follow them. In practising representative government it is the custom for men of the same opinion to share the same fate. Whatever the custom, Monsieur le Baron, honour demands it, since it is not a question of favour but one of disgrace. Consequently, I am repeating in writing the offer I made to you verbally of my resignation as plenipotentiary minister to the Court of Berlin; I hope Monsieur le Baron that you will be kind enough to inform the King. I beg His Majesty to credit my motives, and to accept my profound and respectful gratitude for the recognition he has deigned to honour me with.

I have the honour to be, etc.

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

I announced the event which would sever our diplomatic relationship to Monsieur the Count von Bernstorff; he replied as follows:

‘Monsieur le Vicomte,

Though I may have anticipated the news you have been kind enough to inform me of, for some time, I am no less painfully affected by it. I understand and respect the motives which, in this delicate matter, have determined your decision; but in adding new titles to those which have earned you universal esteem in this country, it also augments the regrets felt here in the certainty of a loss long-feared and forever irreparable. These sentiments are strongly shared by the King and the royal family, and I wait only for the moment of your recall to say it to you in an official capacity.

Preserve your memory and goodwill towards me, I beg you, and accept this new expression of my inviolable devotion and the high regard with which I have the honour to be, etc, etc.

BERNSTORFF.

Berlin, the 25th of August 1821.’

I was urged to express my friendship and regrets to Monsieur Ancillon: his very fine reply (the praise for me apart) merits its inclusion here:

‘Berlin, the 22nd of September 1821.

You are then, my dear Sir and illustrious friend, irrevocably lost to us? I foresaw this misfortune, and yet it has affected me, as much as if it had been unexpected. We deserved to possess and retain you, because we have at least the feeble merit of fully feeling, knowing and admiring your superiority. To tell you that the King, the Princes, the Court and the city regret your absence is to praise them more than yourself; to tell you that I rejoice in those regrets, that I am proud of my country as a result, and that I share strongly in them, would fall far short of the truth, and give you a very poor notion of what I feel. Allow me to believe that you know me well enough to read my heart. If that heart accuses you, my mind not only absolves you but renders homage to your noble action and the principles which dictated it. You will provide a great lesson and be a fine example to France; you have given both, by refusing to serve a government which does not know how to evaluate the situation, or has not the necessary strength of mind to resolve it. In a representative monarchy, the ministers and those who they employ in senior positions ought to form a homogenous whole, all parts of which should show solidarity with one another. There, less than anywhere else, should one separate from one’s friends; one supports them and rises with them, equally one descends and falls with them. You have shown France the truth of this maxim, in resigning with Messieurs de Villèle and Corbière. At the same time, you have also taught her that fortune is not a consideration when it is a matter of principles; and, indeed, if yours had not reason, conscience and the experience of all times, on their side, it would only take the sacrifices they dictate to such a person as yourself to establish a powerful presumption in their favour, in the eyes of all those who understand nobility.

I await with impatience the result of the next election to draw France’s horoscope. They will decide her future.

Farewell, my illustrious friend; let drops of dew fall sometimes from the heights you inhabit onto a heart which will not cease to admire you and love you until it ceases to beat.

ANCILLON.’

Attentive to the good of France, and no longer concerned with myself or my friends, I sent the following note at a later date to Monsieur:

‘NOTE.

If the King does me the honour of consulting me, here is what I would propose for the good of the service and the peace of France:

The centre-left of the elected Chamber was satisfied with the nomination of Monsieur Royer-Collard; yet I believe peace would be more assured if someone of merit was introduced into the Council of that opinion and selected from among the members of the Chamber of Peers or the Chamber of Deputies.

To appoint to the Council an independent deputy of the right;

To complete the distribution of appointments in that spirit.

As for other things:

To present complete legislation at the appropriate time covering the freedom of the Press, in which ‘proceedings based on tendency’ and ‘discretionary censure’ would be abolished; to prepare a definition of common law; to complete the legislation on septennial renewal, taking the age of eligibility to thirty years; in a word going forward Charter in hand, to defend religion, courageously, against impiety, but at the same time protecting it from fanaticism and the imprudence of a zeal which does it great harm.

As for external affairs, three things should guide the King’s Ministers: honour, freedom and the interests of France,

France is now wholly Royalist; she can become wholly revolutionary: let us attend to institutions and I will answer with my head for a few coming centuries; violate or distort those institutions, and I would not answer for a few months.

I and my friends are ready to support with all our strength an administration built on the foundations indicated above.

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

A voice, in which the woman overcame the princess, arrived to give consolation to what would have been the mere unpleasantness of a life forever changing. Madame the Duchess of Cumberland’s handwriting was so altered that I had difficulty in recognising it. The letter bore the date 28th of September 1821: it was the last that I received from the royal hand. (Princess Frederica, Queen of Hanover, succumbed after a long illness. Note: Paris, July 1841) Alas, the noble friends who sustained me in Paris in those days have left this world! Am I to remain here so obstinately, that no one to whom I am attached shall survive me? Happy are those on whom age has the same effect as wine, who lose their memory when they are full of years!

Book XXVI: Chapter 11 – Monsieur de Villèle, Finance Minister– I am appointed Ambassador to London

BkXXVI:Chap11:Sec1

The resignations of Messieurs de Villèle and de Corbière did not long delay the dissolution of the Cabinet and the re-entry of my friends to the Council, as I had foreseen; Monsieur le Vicomte de Montmorency was appointed as Foreign Minister, Monsieur de Villèle as Finance Minister, and Monsieur de Corbière as Minister of the Interior. I had played too great a part in recent political events and I exercised too great an influence on opinion to be passed over. It was decided that Monsieur le Duc Decazes be replaced as Ambassador in London: Louis XVIII was always happy to send me away. I went to thank him; he talked to me of his favourite with a constancy of attachment rare in a king; he begged me to erase from George IV’s mind the prejudices that he had conceived against Monsieur Decazes, and to forget myself the divisions which had existed between me and the former Minister of Police. This monarch, from whom so many misfortunes had failed to draw a tear, was moved by the suffering with which the man he had honoured with his friendship may have been afflicted.

My appointment brought back memories: Charlotte entered my thoughts again; my youth, my emigration, appeared to me all with their joy and pain. Human weakness also gave me pleasure at the thought of reappearing, powerful and recognised, where I had been unknown and powerless. Madame de Chateaubriand, fearing the sea, did not dare to cross the Channel, and I departed alone. The secretaries to the embassy had gone on ahead.

End of Book XXVI