François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXV: The Second Restoration: 1815-1820

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXV: Chapter 1: The changing world

- Book XXV: Chapter 2: The years 1815,1816 in my life – I am appointed a Peer of France – My debut at the rostrum – Various speeches

- Book XXV: Chapter 3: Monarchy according to the Charter

- Book XXV: Chapter 4: Louis XVIII

- Book XXV: Chapter 5: Monsieur Decazes

- Book XXV: Chapter 6: I am struck off the list of Ministers of State – I sell my books and La Vallée

- Book XXV: Chapter 7: Further speeches of mine in 1817 and 1818

- Book XXV: Chapter 8: Meetings at Piet’s

- Book XXV: Chapter 9: The Conservateur

- Book XXV: Chapter 10: On the Morality of Material Interests and that of Duty

- Book XXV: Chapter 11: My life in 1820 – The death of the Duc de Berry

- Book XXV: Chapter 12: The birth of the Duke of Bordeaux – The women of Bordeaux Market

- Book XXV: Chapter 13: I assist Monsieur de Villèle and Monsieur de Corbière to their first Ministry – My letter to the Duc de Richelieu – A note from the Duc de Richelieu and my reply – A note from Monsieur de Polignac – Letters from Monsieur de Montmorency and Monsieur de Pasquier

Book XXV: Chapter 1: The changing world

Paris, 1839 (Revised 22nd February 1845)

BkXXV:Chap1:Sec1

To plunge from Bonaparte and the Empire into what followed them, is to plunge from reality into nothingness, from the summit of a mountain into the gulf. Did everything not end with Bonaparte? Ought I to speak of anything else? What could be of interest after him? Can there be any question of who or what, in the wake of such a man? Dante alone had the right to associate with the great poets in the regions of the afterlife. How can one speak of Louis XVIII instead of the Emperor? I am embarrassed when I think that I had to twitter along at that time with a crowd of miniscule creatures of whom I made one, dubious-seeming nocturnal beings as we were, in a landscape from which the great sun had departed.

The Bonapartists themselves had shrivelled. Their limbs were folded and contracted: a soul was missing from the new universe the moment Bonaparte withdrew his breath; objects faded now that they were no longer illuminated by the glow which had given them shape and colour. At the beginning of these Memoirs I had only myself to speak of: now there is always a kind of primacy in individual human solitude; then I was surrounded by miracles: those miracles sustained my voice; but in the days after the conquest of Egypt, after the battles of Marengo, Austerlitz, Jena, after the retreat from Russia, after the taking of Paris, the return from Elba, the battle of Waterloo, the funeral on St Helena: what then? Portraits to which Molière’s genius alone could grant theatrical gravity!

In expressing our lack of worth, I have examined my conscience closely; I have asked myself whether I have not identified myself in a calculated manner with the nullity of those days, in order to claim the right to condemn others; persuaded as I was in petto (privately) that my name spoke for itself among all those unassuming souls. No: I am convinced that we will all vanish: firstly because we have not that in us with which to stay alive; secondly because the century, in which we are beginning or ending our days, lacks the means itself with which to keep us alive. Mutilated, worn out, despicable generations, without faith, dedicated to the nothingness they love, do not know how to grant anything immortality; they have no power to create a reputation; when you give ear to their speech you hear nothing: no sound issues from the lips of the dead.

However one thing strikes me: the little world, which I address now, was superior to the world which succeeded it in 1830: we were giants in comparison with the society of mites which it bred.

The Restoration offers at least one aspect from which one can retrieve something of importance: after the pride of a single man, that man being past, the pride of mankind was reborn. If despotism has been replaced by liberty, if we know something of freedom now, if we have lost the habit of crawling, if the laws of human nature are no longer unknown, it is to the Restoration that we are thus indebted. Let me throw myself into the throng, so that, to the best of my abilities, I too might revive the species if the individual is finished.

On then, let us pursue our task! Let us plunge with groans towards myself and my colleagues. You have seen me in the midst of my dreams; you will see me now in the midst of my reality; if it is less interesting, if I decline, reader, be just: take my subject’s part.

Book XXV: Chapter 2: The years 1815,1816 in my life – I am appointed a Peer of France – My debut at the rostrum – Various speeches

BkXXV:Chap2:Sec1

After the King’s second return and Bonaparte’s final disappearance, the Government being in the hands of Monsieur the Duke of Otranto and Monsieur le Prince de Talleyrand, I was appointed President of the Electoral College for the department of Loiret. The elections of 1815 gave the King the introuvable (unparalleled) Chamber. Everyone in Orléans made a fuss of me, when the decree which appointed me to the Chamber of Peers arrived. My career as a man of action which had barely commenced suddenly changed direction: what might I have become if I had taken my seat in the Elected Chamber? It is quite probable that a career there, if successful, would have ended with my joining the Interior Ministry, instead of my being led to the Foreign Ministry. My habits and manners were more in tune with the peerage, and though the latter was hostile to me from the first, because of my liberal opinions, it is still the fact that my views on the freedom of the Press and against subservience to foreigners gave that noble Chamber the popularity it enjoyed as long as it tolerated my opinions.

On arrival I received the only honour my colleagues have ever granted me during my fifty years residence among them: I was appointed as one of the four secretaries during the session of 1816. Lord Byron obtained no more favour when he appeared in the Lords, and he chose to distance himself from it forever; I should have gone back to my wilderness.

‘Palais du Luxembourg, Façade de la Rue de Vaurigard’

Les Merveilles du Nouveau Paris - Joseph Décembre, Edmond Alonnier (p134, 1867)

Internet Archive Book Images

My debut at the rostrum was a speech on the permanence of judges; I praised the principle, but criticised its immediate application. During the Revolution of 1830 the men of the left most committed to that Revolution wished to suspend the decree of permanence for a while.

On the 22nd of February 1816, the Duc de Richelieu brought us the signed will of the former Queen; I mounted the rostrum and said:

‘He who preserved the will of Marie-Antoinette purchased the estate of Montboissier. A judge who tried Louis XVI, he erected on that estate a monument to a defender of Louis XVI; he himself engraved an epitaph in French verse on that monument in praise of Monsieur de Malesherbes. That astonishing impartiality tells us that everything is askew in the moral world.’

On the 12th of March 1816 the question of ecclesiastical pensions was raised. ‘You would refuse food,’ I said, ‘to some poor vicar the rest of whose life is consecrated to the altar, and yet you would grant pensions to Joseph Lebon, who made so many heads roll, to Francis Chabot, who demanded a law for emigrés so biased that a child could have sent them to the guillotine, and to Jacques Roux, who, refusing to accept Louis XVI’s last testament in the Temple, replied to that unfortunate monarch: ‘I am only charged with conducting you to your death.’

A proposed law regarding the electoral process was brought before the hereditary Chamber; I declared myself in favour of the total renewal of the Chamber of Deputies; it was only in 1824, when a Minister, that I was able to make it law.

It was also during this first speech on electoral law in 1816 that I replied to an adversary: ‘I do not accept what has been said regarding Europe’s interest in our discussions. For myself, Gentlemen, I doubtless owe to the French blood flowing in my veins that impatience I experience when, in order to influence my vote, people speak to me of opinions expressed beyond my country’s borders; if civilised Europe wished to impose the Charter on me, I should go and live at Constantinople.’

On the 9th of April 1816, I put a proposal to the Chamber regarding the Barbary Pirates. The Chamber decided that it was necessary to concern itself with the matter. I had already thought of opposing forced slavery, before I obtained this favourable decision of the peerage, the first political intervention of a great power in favour of the Greeks: ‘I have viewed the ruins of Carthage;’ I said to my colleagues, ‘I have encountered, among those ruins, the successors to those unfortunate Christians for whose deliverance St Louis sacrificed his life. Philosophy will be able to share in the glory attached to the success of my proposal, and boast of having achieved in an age of enlightenment what religion attempted in vain to achieve in an age of darkness.’

‘Fight of the Gunboats’

Our Navy and the Barbary Corsairs - Gardner Weld Allen (p230, 1905)

Internet Archive Book Images

I had taken my seat in an assembly where, three quarters of the time, my words were turned against me. One can influence a popular Chamber: an aristocratic Chamber is deaf. Away from the rostrum, in camera, before those old men, the desiccated remains of the Old Monarchy, the Revolution, and the Empire, what strayed from the most commonplace of tones appeared folly. One day the first row of chairs, close to the rostrum, was filled with respectable Peers, each one deafer than the rest, heads drooping, clasping their ear-trumpets with horns directed towards the rostrum. I put them to sleep, which was natural. One of them let slip his ear-trumpet; his neighbour, woken by the noise, wished, politely, to recover his colleague’s aid; he fell over. The problem was that I began laughing, though I should have been speaking movingly on who knows what touching subject.

The orators who were successful in that Chamber were those who spoke, lacking ideas, in a level monotone, or who had the sense only to be moved by the wretched Ministers. Monsieur de Lally-Tollendal thundered on in favour of public freedoms: he would make our solitary vaults echo, he claimed, in praise of three or four English Lord Chancellors, his ancestors. When his panegyric on the liberty of the Press ended, a ‘but’ emerged dictated by circumstances, which ‘but’ kept our honour intact, beneath the beneficial gaze of the censor.

The Restoration gave an impetus to intellectual thought; it freed reflections stifled by Bonaparte: wit, like a caryatid liberated from some building which bowed down its brow, raised its head once more. The Empire struck France mute; liberty, once restored, dubbed her and restored her speech: it discovered talented orators who took up again where Mirabeau and Cazalès had left off, and the Revolution continued its course.

Book XXV: Chapter 3: Monarchy according to the Charter

BkXXV:Chap3:Sec1

My labours were not limited to the rostrum, so new to me. Appalled by the arrangements that were being contemplated and by French ignorance regarding the principles of representative government, I wrote and published La Monarchie selon la Charte.

This publication marked one of the great epochs of my political life: it ranked me among the publicists; it served to form public opinion regarding the nature of our government. The English newspapers praised the piece to the skies; over here, even the Abbé Morellet could not get over my change of style and the dogmatic precision of its truths.

Monarchy according to the Charter is a constitutional catechism: from it are drawn the majority of propositions advanced as new these days. Thus the principle that the King reigns and does not govern, is found complete in chapters IV to VII on the royal prerogative.

These constitutional principles were set out in the first part of Monarchy according to the Charter, in the second part I examined the workings of the three governments which had followed in succession between 1814 and 1816; in this latter part are found various predictions since only too surely verified, and the exposition of doctrines then unrecognised. These words can be found in Chapter XXXVI, of the second part: ‘It is taken as read amongst a certain group of people that a revolution of the nature of ours can only end in a change of dynasty; others, more moderate, say in a change in the order of succession to the Crown.’

As I was completing my work, the decree of the 5th of September 1816 appeared; that measure scattered the few royalists who had gathered to reconstitute the legitimate monarchy. I hastened to write a postscript which produced an explosion of anger on the part of Monsieur the Duc de Richelieu, and Monsieur Decazes, Louis XVIII’s favourite.

The postscript having been added, I hastened to Monsieur Le Normant, my bookseller; on arrival, I found the gendarmes, with a police commissioner orchestrating things. They had seized various parcels and affixed their seal. I had not braved Bonaparte to be intimidated by Monsieur Decazes: I opposed the seizure; I declared that as a free Frenchman and a Peer of France I would only yield to force: the force arrived and I withdrew. I presented myself on the 18th of September to the Royal notaries, Messieurs Louis-Marthe Mesnier and his colleague; I registered my protest at their office and requested them to record my factual declaration of the seizure of my work, wishing to secure the rights of French citizens by that protest. Monsieur Baude imitated me in 1830.

I next found myself engaged in a long correspondence with Monsieur the Chancellor, Monsieur the Minister of Police, and Monsieur Bellart, the Public Prosecutor, until the 9th of November, the day on which the Chancellor announced a decree rendered in my favour by the tribunal of the first instance, which set me once more in possession of my impounded work. In one of his letters, Monsieur the Chancellor told me that he had been greatly distressed to witness the discontent with my work which the King had expressed publicly. That discontent arose from the chapters where I set myself against the establishment of a government of universal policing in a constitutional country.

Book XXV: Chapter 4: Louis XVIII

BkXXV:Chap4:Sec1

In my account of the journey from Ghent, you saw what a worthy scion of Hugh Capet Louis XVIII was; in my text, Le Roi est mort: vive le Roi! I have enumerated that Prince’s actual qualities. But man is not a single unity: why have so few faithful portraits been produced? Because the model was posed at such and such a period of his life; ten years afterwards, the portrait no longer resembled him.

‘Louis XVIII, d'Après J. L. David’

L'Histoire de France Depuis 1789 Jusqu'en 1848, Racontée à mes Petits-Enfants, par M. Guizot. Leçons Recueillies par Madame de Witt, Vol 02 - François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (p595, 1878)

The British Library

Louis XVIII did not adopt the long view of objects before and around him; all seemed beautiful or ugly to him according to his angle of vision. Influenced by his century, it is to be feared that religion for that Very Christian King was only a suitable elixir in which to mix the compounds from which royalty was constituted. The free-thinking spirit he had inherited from his grandfather might have presented a barrier to his undertakings; but he was self-aware, and when he spoke in an assertive manner, he took pride in making fun of himself. I spoke to him one day about the necessity of Monsieur le Duc de Bourbon marrying afresh, to bring new life to the Condé line: he approved strongly of the idea, though he cared little about the aforesaid revival; but in that regard he spoke to me of Monsier le Comte d’Artois saying: ‘My brother could marry without any alteration in the succession to the throne, he only produces younger sons; as for me, I only produce older ones: I do not wish to disinherit Monsieur le Duc d’Angoulême.’ And he puffed out his breast with a capable mocking air; but I did not to intend to quarrel with the King about power.

An unprejudiced egoist, Louis XVIII desired peace at any price: he supported his ministers as long as they commanded a majority: he dismissed them as soon as their majority was overturned, and there was a risk of his rest being disturbed; he did not mind retreating if, with a view to achieving victory, he had been obliged to take a step forward. His greatness was in patience; he did not advance towards events, events came to meet him.

Without being cruel, the King was not humane: catastrophic tragedies neither astonished nor moved him: he contented himself with saying to the Duc de Berry, who apologised for having had the misfortune to trouble the King’s rest in dying: ‘I slept straight through.’ Yet that calm individual, when he was annoyed, indulged in terrible rages; and this Prince, so cold, so insensitive, had relationships which resembled passions: thus there succeeded in his intimacy the Comte d’Avaray, Monsieur de Blacas, Monsieur Decazes, Madame de Balbi, and Madame du Cayla; all these beloved personages were favourites; unfortunately they kept far too many letters in their hands.

Louis XVIII appears to us clothed in all the depths of historic tradition; he displayed the favouritism of former royalty. Is there some void in the hearts of solitary monarchs which they fill with the first object they find? Is it empathy, affinity with a nature analogous to theirs? Is it a friendship that heaven sends them to console their greatness? Is it an inclination towards a slave who gives body and soul, before whom one conceals nothing, a slave who becomes a garment, a plaything, an obsession linked to every feeling, every taste, every whim of him to whom the slave submits, and whom the slave holds power over through an unbreakable fascination? The more submissive and intimate the favourite has been, the less easily can that favourite be dismissed, being in possession of secrets which would embarrass if they were divulged: the one preferred acquires a dual power from depravity, and from the master’s weaknesses.

When the favourite happens to be a great man, like the obsessive Richelieu or the irreplaceable Mazarin, nations, while detesting him, profit from his glory and his power; they merely exchange a wretched king in law for an illustrious king in fact.

‘Le Cardinal de Richelieu’

Promenades Pittoresques en Touraine. Histoire, Légendes, Monuments, Paysages...Gravures...d'Après Karl Girardet et Français - Casimir Chevalier, Carl Girardet, Louis Français (p506, 1869)

The British Library

Book XXV: Chapter 5: Monsieur Decazes

BkXXV:Chap5:Sec1

As soon as Monsieur Decazes was appointed a Minister, carriages jammed the Quai Malaquais each evening, to deposit whatever was noblest of the Faubourg Saint-Germain at the newcomer’s salon. The Frenchman has to do things well, he can never be merely a courtier; no matter what it is, as long as it will make him a power to be reckoned with.

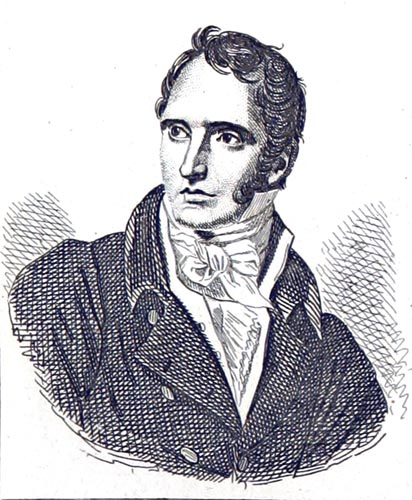

‘Decazes’

France Pittoresque...des Départements et Colonies de la France, Vol 02 - Jean Abel Hugo (p389, 1838)

The British Library

A formidable coalition of idiocies soon formed around a new favourite. In a democratic society, you can chatter about liberty, claim that you can foresee the course of the human race and the future of things, while winning a few prize medals with your speeches, and you are sure of your place; in an aristocratic society, play whist, churn out commonplaces and pre-conceived witticisms with a profound and serious air, and your talent is assured of good fortune.

A compatriot of Murat, but a Murat without a kingdom, Monsieur Decazes came to us courtesy of Napoleon’s mother. He was friendly, obliging, and never insolent; he wished me well, I do not know why, since I was indifferent: from that arose the beginning of my problems. It was to teach me that one must never show lack of respect to a favourite. The King lavished kindnesses and wealth on him, and married him later to a very well-born lady, the daughter of Monsieur de Sainte-Aulaire. It is true that Monsieur Decazes served royalty almost too well; it was he who unearthed Marshal Ney in the mountains of the Auvergne where he was hiding.

Faithful to his ideas of royalty, Louis XVIII said of Monsieur Decazes: ‘I will elevate him such that he will be envied by the greatest of lords.’ That phrase, borrowed from another king, was merely an anachronism: to elevate others one must be certain not to descend oneself; now, at the period Louis XVIII had reached, what were monarchs? If they could still make a man’s fortune, they could not make him great; they were no more than their favourites’ bankers.

Madame Princeteau, sister of Monsieur Decazes, was a pleasant, modest, excellent person; the King was infatuated with the prospect of her. Monsieur Decazes the elder, whom I saw in the throne-room in full dress, sword at his side, hat under his arm, nevertheless had no success.

Finally, the death of Monsieur the Duc de Berry increased hostility on all sides and led to the favourite’s fall. I said that his feet were slippery with blood, which did not signify, God forbid, that he was guilty of murder, but that he fell into that crimson sea which formed beneath Louvel’s knife.

Book XXV: Chapter 6: I am struck off the list of Ministers of State – I sell my books and La Vallée

BkXXV:Chap6:Sec1

I resisted the seizure of La Monarchie selon la Charte in order to shed light on the abuse of royal power, and to defend freedom of thought and the Press; I had freely embraced our institutions, and remained faithful to them.

These troubles being over, I was left bloodstained from the wounds dealt me on publication of my pamphlet. I was unable to take possession of my political career without scars from the blows I received on entering that career: I felt ill, I could not breathe.

A little while later, a decree signed Richelieu struck me off the list of Ministers of State, and I was deprived of a position which until then had been considered permanent; it had been granted to me at Ghent, and the pension attached to the position was withdrawn: the hand which had welcomed Fouché struck at me.

I have had the honour of being despoiled by the Legitimacy on three occasions: the first time, for having followed the scions of St Louis into exile; the second, for having written in support of the principles of monarchy by consent; the third time, for ruining myself in accord with a disastrous law at the moment when I was about to achieve a military triumph: the soldiers of the country of Spain had returned to the white banner, and if I had been left in office, I should have extended our frontier to the banks of the Rhine once more.

My nature makes me totally indifferent to loss of office; I was reduced to going on foot again and, on wet days, taking a cab to the Chamber of Peers. In my public vehicle, protected by the rabble which travelled around me, I returned to the laws of the proletariat of whom I now made one: from the height of my fiacre I could look down on the processions of kings.

I was obliged to sell my books: Monsieur Merlin put them up for auction at the Sylvestre Room, on the Rue des Bons-Enfants. I kept only a little Homer in Greek, in whose margins were attempts at translation and comments written in my own hand. Soon I had to cut back; I asked Monsieur the Minister of the Interior for permission to sell my country house by lottery: the lottery was inaugurated at the offices of Monsieur Denis, the notary. There were ninety tickets at 1000 francs each: the Royalists would not take up the tickets; Madame the Dowager Duchesse d’Orléans, took three; my friend Monsieur Lainé, Minister of the Interior, who had signed the decree of 5th September and agreed to my erasure in council, took a fourth ticket, under a false name. The money was returned to the subscribers; however, Monsieur Lainé refused to reclaim his 1000 francs; he left it with the notary to be given to the poor.

A short while afterwards, my Vallé-aux-Loups was sold, as the poor sell their furniture, at the Place Chatelet. I suffered a great deal on that sale; I was fond of my trees, planted and growing, so to speak, with my memories. The offer price was 50,000 francs; it was accepted by Monsieur le Vicomte de Montmorency, who alone dared to overbid by a hundred francs: the Vallé was his. He has since taken possession of my retreat: it is not wise to be involved with my fate: that virtuous man is no more.

Book XXV: Chapter 7: Further speeches of mine in 1817 and 1818

BkXXV:Chap7:Sec1

After the publication of Monarchy according to the Charter, and at the opening of the new session in November 1816, I continued my struggle. In the Chambers of Peers on the 23rd of that month, I put forward a proposal by which the King was humbly implored to have investigations made into what had transpired during the recent elections. The corruption and force employed by the government in those elections had been flagrant.

Regarding my opinion on a legal matter relating to the finances (the 21st of March 1817), I objected to item XI of that proposal: it concerned the intention to allocate the State forests to a sinking fund, and the desire then to sell off a hundred and fifty thousand hectares. These forests comprised three sorts of property: the ancient domains of the Crown, several Commanderies of the Order of Malta and the remaining Church assets. I am not sure why, even today, I take a melancholy interest in my words; they find echoes in my Memoirs:

‘With all due respect to those who have only been administrators during the troubles, it is not material tokens, but the morals of a nation that create public credit. Will the new owners be worthy of their new properties? They will be called to account for despoiling these, the legacies of nine centuries stolen from their former possessors. Instead of those immutable patrimonies in which the same family lived, like a succession of oak trees, you will have disposable properties where the reeds scarcely have time to grow and die before they have changed masters. Houses will cease to be the guardians of domestic morality; they will lose their traditional authority; highways open to all comers, they will no longer be consecrated, as ancestral seats and cradles of the new-born.

Peers of France, it is your cause I plead here and not mine: I speak to you on behalf of your children; I shall have no concern with posterity; I have no children; I have lost my father’s estate, and the few trees I have planted will soon be mine no longer.’

Book XXV: Chapter 8: Meetings at Piet’s

BkXXV:Chap8:Sec1

Due to a meeting of minds, a close one at that time, camaraderie was established between the minority groupings in both Chambers. France educated itself concerning representative government: as I was so foolish as to stick to the letter of it, and felt a veritable passion for it, to my detriment, I supported those who espoused it, without concerning myself as to whether they exhibited in their opposition more of human motive than the pure love I conceived for the Charter; not that I was a complete fool, but I did idealize my mistress, and I would have traversed the flames to take her in my arms. It was during this constitutional fit, in 1816, that I met Monsieur de Villèle. He was calmer; he controlled his ardour; he also intended to win freedom; but he laid siege by rule; he cut trenches methodically; while I, who desired to assault the place, I scaled ladders and was often hurled down into the moat.

I encountered Monsieur de Villèle for the first time at the Duchesse de Lévi’s. He had become leader of the Royalist opposition in the elected Chamber, as I was in the hereditary Chamber. Monsieur de Corbière was a friend of his. That gentleman never left his side, and people spoke of Villèle and Corbière, as one says Orestes and Pylades, or Euryalus and Nisus.

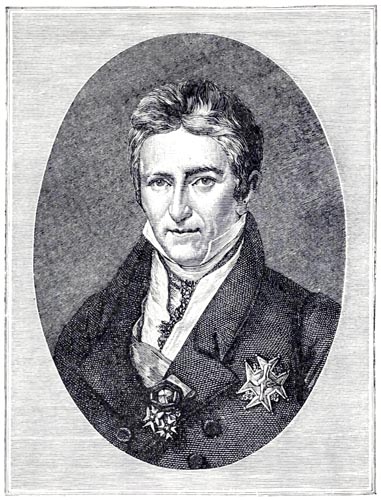

‘Villèle. From a Painting in Private Possession (from d'Héricault)’

A History of all Nations From the Earliest Times; Being a Universal Historical Library - John Henry Wright (p153, 1905)

Internet Archive Book Images

To enter into fastidious detail regarding people whose names one will have forgotten tomorrow would be a foolish vanity. Obscure and tedious events, that one thinks of immense interest, and that interest no one; past machinations, that led to no major outcome, ought to be left to those happy optimists who consider themselves to be or have been the world’s object of attention.

Yet there were moments of pride when my arguments with Monsieur de Villèle seemed to me like the dissension between Marius and Sulla, or Caesar and Pompey. With the other members of the opposition, we quite often went to the Rue Thérèse, to spend the evening in discussion at Monsieur Piet’s. We would arrive in an extremely ugly mood, and would sit round the walls of a salon lit by a lamp which smoked. In that legislative fog, we talked of proposed laws, motions to be enacted, of approaches to be made to the secretariat, the administration, and various commissions. There was criticism on all sides. We looked considerably like those assemblies of the early church, as depicted by the enemies of the faith: we spewed out the direst news; we declared that things must change, that Rome would be troubled by division, that our armies would be defeated.

Monsieur de Villèle listened, summarised and concluded nothing: he was a great aid to business; a cautious sailor, he never set out to sea during a storm, and though he would enter a known harbour, skilfully, he could never have discovered the New World. I often remarked, regarding our discussions about the sale of church assets, that the most Christian among us were the most ardent in defending the constitutional position. Religion is a source of freedom: in Rome, the flamen dialis only wore only a hollow ring on his finger, because a solid ring might suggest a link of chain; on his clothing and his cap Jupiter’s high priest allowed no knots.

After a meeting, Monsieur de Villèle would withdraw, accompanied by Monsieur de Corbière. During those meetings, I studied many individuals, learnt many things, and occupied myself with the many subjects of our get-togethers: I was initiated into the elements of finance, something that I always sweated over; the army, the judicial system, and the administration. I left those conferences a little more of a Statesman and a little more persuaded of the poverty of all such science. All night long, half-asleep, I saw bald heads in various attitudes, the faces of those Solons, with various expressions on their visages, disarranged and separated from their bodies: it was all very respectable for sure; but I preferred the swallow that woke me in my youth and the Muses who filled my dreams: the rays of dawn, striking the swans in flight, that cast the shadows of those white birds onto a gilded wave; the rising sun appearing to me in Syria at the crest of a palm tree, as if in a phoenix’s nest, delighted me more.

Book XXV: Chapter 9: The Conservateur

BkXXV:Chap9:Sec1

I felt that my battles at the rostrum, in a closed Chamber, and in the midst of an assembly which was poorly disposed towards me, were an ineffective path to victory and that I needed another weapon. Censorship of the daily papers having been established, I could only fulfil my aim by means of a free paper, published irregularly, by the aid of which I could attack both the governmental system and the extreme left-wing opinions expressed by Monsieur Étienne in the Minerve. In the summer of 1818, I was at Noisiel, the home of Madame the Duchesse de Lévis, where my publisher Monsieur Le Normant came to see me. I explained the idea which preoccupied me; he took fire, offering to run all the risks and cover all the costs. I spoke to my friends Messieurs de Bonald and de Lamennais, asking them if they would collaborate with me: they agreed, and the paper soon appeared under the name of the Conservateur.

That newspaper caused an extraordinary revolution: in France it affected the majority in the two Chambers; abroad it transformed government attitudes.

Thus the Royalists did me the favour of emerging from the nothingness into which they had fallen vis-à-vis nations and kings. I set a pen in the hands of the greatest families of France. I presented the Montmorencys and Lévis as journalists; I summoned the arrière-ban, and made feudalism march to the aid of the freedom of the Press. I brought together once more the most brilliant lights of the Royalist party, Messieurs de Villèle, de Corbière, de Vitrolles, de Castelbajac etc. I could not help blessing Providence every time I draped the red robe of a Prince of the Church over the Conservateur to act as a cover, or had the pleasure of reading an article signed in full: the Cardinal de La Luzerne. But it so happened that after leading my knights to the constitutional crusade, as soon as they had overcome power and delivered freedom, as soon as they had become princes of Edessa, Antioch and Damascus, they shut themselves in their new States with Eleanor of Aquitaine, and left me to mope at the foot of the wall of Jerusalem where the infidels had recaptured the Holy Tomb.

My polemic, begun in the Conservateur, lasted from 1818 until 1820 that is to say until the re-establishment of censorship, for which the pretext was the death of the Duc de Berry. At this first stage of my polemic, I brought about the fall of the current minister and brought Monsieur de Villèle to power.

I began speaking out immediately after the Hundred Days; it was then that I set about educating Royalists in the constitution. After 1824, when I took up the pen again in pamphlets and in the Journal des Débats, the situation had altered. Yet what did they matter to me, those wretched futilities, to me who have never believed in the times in which I have lived; to me who might have belonged to the past, to me without faith in kings, lacking conviction in nationalism, to me who never cared for anything but dreams, on condition however that they did not last longer than a night!

The first article in the Conservateur sketched out the state of affairs at the moment when I entered the lists. During the two years the newspaper existed, I depicted successively the events of the day, and examined key interests. I had occasion to note the cowardice represented by that private correspondence which the Paris police had published in London. Those private correspondences might libel, but they could not dishonour: what is base has no power to debase; honour alone can inflict dishonour. ‘Anonymous calumniators’ I proclaimed, ‘have the courage to state who you are; a little shame is soon overcome; add your surname to your articles, it will only add one despicable word more.’

I sometimes made fun of Ministers and I expressed that ironic tendency that I always disapprove of in myself.

The Conservateur of the 5th of December 1818 contained a serious article concerning the morality of various interests and the morality of duty: from that article, which made a stir, derives the phraseology concerning moral interests and material interests, first mooted by me, and then adopted by everyone. Here it is, highly abridged; elevated beyond the usual level of a newspaper, it is one of my works to which my reason ascribes some value. It has not aged, because the ideas it contains are timeless.

Book XXV: Chapter 10: On the Morality of Material Interests and that of Duty

BkXXV:Chap10:Sec1

‘The Government has invented a new morality, that of interests; that of duty has been abandoned to imbeciles. Now, this morality of interests, on which they wish to found our administration, has corrupted the nation more in the space of three years than the Revolution did in a quarter of a century.

What destroys morality among nations, and with morality those nations themselves, is not violence, but seduction; and by seduction I mean that which all false doctrine contains of the flattering and the specious. Men often mistake error for truth, because every faculty of feeling or intellect has its false representation: calmness resembles virtue, rationalisation reason, emptiness depth, and so on.

The eighteenth century was a destructive century; we were all seduced. We distorted politics; we distracted ourselves with culpable novelties while searching for social reality in a corruption of morals. The Revolution arrived to awaken us: dragging the Frenchman from his bed, it hurled him into his grave. However, the Reign of Terror is perhaps, of all the stages of the Revolution, that which was least dangerous to morality, because no conscience was constrained: the crime was in its freedom. Orgies drenched in blood, scandals which no longer had the power to shock; all was there. The nation’s women set to their tasks around the murderous mechanism as if it were their fireside: the scaffolds constituted public morality, and death the basis of government. Nothing was clearer than each man’s position: no one spoke of specialists, or affirmation, or a system of interests. All this gibberish produced by petty minds and bad consciences was unknown. They said to a man: ‘You are a royalist, noble, and wealthy: die’: and he died. Antonelli wrote that there were no charges made out against such prisoners, they were condemned as aristocrats: a monstrous indulgence which nevertheless left the moral order untouched; since it is not killing the innocent as innocents which destroys society, it is killing them as though they were guilty.

As a consequence, those terrible times were times of great devotion. Women marched heroically then, to torment; fathers gave themselves up to protect their sons, sons to protect their fathers; unexpected help was given in prison, and the priest, being sought, consoled the victim beside an executioner who did not acknowledge him.

Morality under the Directory had to combat the corruption of manners rather than that of doctrine; there was excess. One was flung into pleasure as one had been crammed into prison; one compelled the present to produce an advance on future joy, for fear of seeing the past reborn. Not yet having had time to create a place to live, everyone lived in the street, on the promenades, in the public rooms. Familiar with scaffolds, and already half beyond the world, one found it scarcely worth while going home. It was not merely a question of arts, dances, fashions; one changed clothes and jewellery as easily as one was stripped of life.

Under Bonaparte the seduction began again, but it was a seduction which brought with it its own remedy: Bonaparte seduced us with the power of glory, and everything great carries a legislative principle within itself. He thought it useful to allow the doctrine of all nations to be taught, the morality of all ages, the religion of all eternity.

I would not be astonished to hear the reply: To found society on a duty is to erect it on a fiction; to root it in self-interest is to establish it on a reality. Now, it is precisely duty that is a fact, and self-interest that is a fiction. Duty which has its source in the Divinity descends to the family, where it establishes a real relationship between father and children; from there, passing into society and separating into two branches, it regulates the relations between king and subject; it establishes in the moral order the chain of service and protection, benefit and gratitude.

There is then no more positive fact than duty, since it gives human society the sole durable existence it can possess.

Self-interest on the contrary is a fiction when it is taken as it is today, in the rigorous and physical sense, since it is no longer in the evening what it was in the morning, since it changes its nature at every instant, since founded on wealth it is possessed of variability.

According to the morality of self-interest, every citizen is in a state of hostility regarding the law and the government, because in society it is always the majority who suffer. No one fights for abstract ideas of order, peace or country; or if they do fight for them, it is because they attach the idea of sacrifice to them: then the morality of self-interest is left behind to return to that of duty: so true is it that society cannot be found to exist outside that sacred boundary!

He who does his duty attracts esteem; he who yields to self-interest is esteemed little. It is a fine thing for the age to extract a principle of government from a source of contempt! Raise politicians to think only of what affects them, and you will see how they will run the State; in that way you will only obtain corrupt greedy ministers, like those mutilated slaves who governed the later Roman Empire who sold everything, remembering that they had been sold themselves.

Note this: self-interest only has power while it still prospers; if times grow hard, it is enfeebled. Duty, on the contrary, is never as energetic as when there is a cost involved in fulfilling it. When times are good, it becomes slack. I like a principle of government which thrives on misfortune: that to a great extent resembles virtue.

What is more absurd that to tell people: Don’t show devotion! Don’t betray enthusiasm! Don’t think of anything but your own interests! It is as though you said to them: Don’t come to our aid, abandon us, if that is in your interest! With that profound approach to politics, when the hour for sacrifice arrives everyone locks their doors, rushes to the window, and watches the monarchy go by.’

Such was my article on the morality of self-interest and the morality of duty.

On the 3rd of December 1819, I mounted the rostrum of the Chamber of Peers once more: I spoke against the false Frenchmen who would give us as a symbol of peace our surveillance by the European powers. ‘Do we have need of guardians? Are we still to be the victim of circumstances? Ought we then to receive, via diplomatic notes, certificates of good conduct? And have we merely changed a garrison of Cossacks for a garrison of ambassadors?’

From that time on I spoke of foreigners as I have since spoken of them during the war in Spain; I dreamt of our freedom at a time when even the liberals opposed me. Men of opposing opinions make a great noise, merely to arrive at silence! Let a few years pass, and the actors leave the scene and the spectators are no longer there to criticise or applaud.

Book XXV: Chapter 11: My life in 1820 – The death of the Duc de Berry

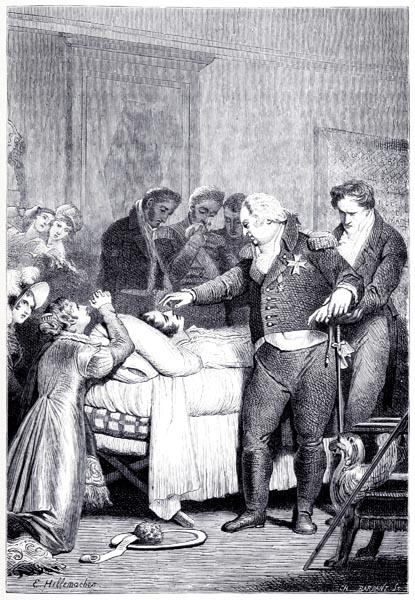

‘Le Duc de Berry’

L'Histoire de France Depuis 1789 Jusqu'en 1848, Racontée à mes Petits-Enfants, par M. Guizot. Leçons Recueillies par Madame de Witt, Vol 02 - François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (p579, 1878)

The British Library

BkXXV:Chap11:Sec1

I was retiring to bed on the evening of the 13th of February, when the Marquis de Vibraye arrived to tell me of the assassination of the Duc de Berry. In his hurry, he forgot to tell me where the event had occurred. I rose in haste and climbed into Monsieur de Vibraye’s carriage. I was surprised to see the coachman take the Rue de Richelieu, and more astonished still when he stopped at the Opéra: the crowd outside was immense. We ascended, between two lines of soldiers, by the side entrance on the left, and, as we were dressed as Peers, we were allowed to pass. We arrived at a kind of little antechamber: this space was crammed with everyone from the palace. I edged my way to the door of a box and found myself face to face with Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans. I was struck by the ill-concealed expression of jubilation in his eyes, though he imposed on himself an almost apologetic countenance: he saw himself closer to the throne. My gaze embarrassed him; he left the box and turned his back on me. Around me the details of the hideous crime were being recounted, the name of the perpetrator, the conjectures of various people involved in his arrest; everyone was agitated, busied: men love a spectacle, especially one involving death, when that death involves the great. Everyone who emerged from the blood-stained laboratory was asked for news. General Alexandre de Girardin was heard to tell of how he had been left for dead on the field of battle, and was not in the least recovered from his wounds: he hoped for such and such, consoled himself with such and such, grieved at such and such. Soon silence overcame the crowd; a hush fell; from the interior of the box issued a slight sound: I put my ear to the door; I made out a groaning noise; the noise ceased: the royal family had arrived to receive the last sigh of a scion of Louis XIV! I entered immediately.

Imagine an empty theatre, after a tragic disaster: the curtain raised, the orchestra pit deserted, the lights extinguished, the machinery still, the scenery motionless and shadowy, the actors, singers, dancers vanished through their trapdoors and secret passages! The royal line of St Louis expired behind a mask, in a place that incurred the Church’s wrath, among carnival debauchery.

In another work I have presented the life and death of Monsieur le Duc de Berry. My reflections, then, are still valid today:

‘A descendant of St Louis, last shoot of the ancient branch, escapes from long exile and returns to his own land; he begins to taste some happiness; he flatters himself in imagining himself reborn, in imagining the monarchy reborn also, in the children God has promised him: suddenly he is struck down in the midst of those hopes, almost in his wife’s arms. He is to die, and he is still young! Should he not accuse Heaven, demanding of it why it treats him with such harshness? Ah, it would be pardonable in him to complain of his fate! For what evil has he done, indeed? He has lived informally among us in perfect simplicity; he has joined in our pleasures and eased our pains; six of his relatives have perished already; why murder him now, why seek him out, innocent as he is, so far from the throne, twenty-seven years after the death of Louis XVI? Let us understand the heart of this Bourbon more deeply! That heart, pierced by a dagger, has never raised a single murmur against us: not one regret regarding his life; not one bitter word has been pronounced by this Prince. Husband, son, father and brother, prey to all the agonies of the soul, all the sufferings of the flesh, he has never ceased asking pardon for the man, whom he will not even call his assassin! The most impetuous of characters suddenly becomes the most gentle. A man bound to life by all the heart’s ties; a prince in the flower of his years; an heir to the finest earthly kingdom is dying, and you might call him unfortunate indeed who has nothing to lose down here.’

‘Le Roi Louis XVIII Ferma Lui-Même les Yeux de ce Neveu, qu'il Appelait son Fils’

L'Histoire de France Depuis 1789 Jusqu'en 1848, Racontée à mes Petits-Enfants, par M. Guizot. Leçons Recueillies par Madame de Witt, Vol 02 - François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (p583, 1878)

The British Library

The murderer Louvel was a young man of sly and unpleasant aspect, such as you see in their thousands in the streets of Paris. He was ill-tempered; he had an aggressive and solitary manner. It is probable that Louvel belonged to no secret society; he was a sectarian not a plotter; he belonged to one of those idealistic conspiracies, whose members may sometimes meet, but often act alone, pursuing their own individual motives. His mind nourished a single idea, like a heart intoxicated with one sole passion. His action was a consequence of his principles: he wished to destroy the whole royal race at a single blow. Louvel has his admirers just as Robespierre does. Our material society, an accomplice in every material enterprise, has quickly destroyed the chapel created in expiation of that crime. We have a horror of moral feeling, because within it the enemy and the accuser are revealed: tears would seem like a recrimination; they hastened to take away the cross from some Christians because of their weeping.

On the 18th of February 1820, the Conservateur paid its tribute of regret in memory of Monsieur le Duc de Berry. The article ended with this line from Racine:

‘If only some drop of our royal blood has escaped!’

Alas! That drop of blood has fallen onto foreign soil!

Monsieur Decazes fell from office. Censorship returned, and despite the assassination of the Duc de Berry, I voted against it: not wishing it to tarnish the reputation of the Conservateur, that journal effectively ended with this apostrophe on the Duc de Berry.

‘Christian Prince! Worthy scion of St Louis! Illustrious offspring of so many monarchs, before you descend to your last resting place, receive our last homage. You read and enjoyed a publication that the censor is about to destroy. You told us several times that its publication saved the throne: alas, we were unable to save your life! We are ceasing to write at the moment when you have ceased to exist: we have the sad consolation of marking the end of our labours with the ending of your life.’

Book XXV: Chapter 12: The birth of the Duke of Bordeaux – The women of Bordeaux Market

BkXXV:Chap12:Sec1

Monsieur the Duc de Bordeaux entered the world on the 29th of September 1820. The newly-born infant was called the child of Europe and the miraculous child: nonetheless he would become the child of exile.

Some time before the Princess went into labour, three women of the Bordeaux market had a cradle made, and, on behalf of all their companions, chose me to present it, and them, to the Duchesse de Berry. Mesdames Dasté, Duranton, and Rivaille, arrived. I hastened to ask the gentleman in the Duchess’ service to ask for an audience according to etiquette. Behold, Monsieur de Sèze considered the right to such an honour belonged to him: it was said that I would never succeed at Court. I was still not reconciled with the government, and I did not appear to be worthy of the task of introducing my humble ambassadresses. I emerged from this grand negotiation as usual, by paying their expenses.

‘The Duchess of Berry and her Children. From a Steel Engraving by Delannoy. Original painting by François Pascal Gerard (1770-1837)’

A History of all Nations From the Earliest Times; Being a Universal Historical Library - John Henry Wright (p148, 1905)

Internet Archive Book Images

It all became an affair of State; the title-tattle concerning it made the newspapers. The ladies from Bordeaux, having heard of it, wrote the following letter to me, on the subject:

‘Bordeaux, the 24th of October 1820.

Monsieur le Vicomte,

We owe you thanks for your goodness in having placed our delight and respect at the feet of Madame la Duchesse de Berry: on this occasion at least no one will prevent you from acting as our interpreter. We have read with the greatest unhappiness the fuss Monsieur le Comte de Sèze has made, in the newspapers; and if we have kept silence, it was for fear of giving you pain. However, Monsieur le Vicomte, no one can be better equipped than you are to pay homage to the truth and correct Monsieur de Sèze’s error regarding our true intentions in our choice of someone to present us to her Royal Highness. We offer to relate everything that has occurred, in a journal of your choice; and, as no one has the right to select our guide, and even to the last moment we flattered ourselves that you would be that guide, what we would state in that regard would necessarily silence everyone.

That is what we have decided, Monsieur le Vicomte; but we thought it was our duty to do nothing without your agreement. Be assured that we would willingly publish, to the world, the details of the fine things you have done regarding the question of our being presented. If we have been a cause of anxiety, we are ready to repair the damage.

We are, and will be forever,

Monsieur le Vicomte,

Your very humble and respectful servants,

Mesdames DASTÉ, DURANTON, RIVAILLE.’

I replied to these generous women, who so little resembled the great ladies:

‘Thank you, dear ladies, for the offer you have made of publishing in a newspaper all that happened regarding Monsieur de Sèze. You are royalists, par excellence, and I too am a good royalist: we must remember above all that Monsieur de Sèze is a respectable man, and has been a defender of our King. That fine action is not erased by a trifling moment of vanity. Let us keep silent: I am satisfied with your good opinion of me among your friends. I have already thanked you for the excellent fruit: Madame de Chateaubriand and I eat the chestnuts every day and speak of you.

Now permit your host to embrace you. My wife sends her compliments, and I am:

Your servant and friend.

CHATEAUBRIAND.

Paris, the 2nd of November 1820.’

But who thinks of those futile arguments these days? The joy and the feasting of that baptismal day are far behind us. When Henri was born on St Michael’s day, would one not have thought that the archangel had trodden the dragon underfoot? It is to be feared, on the contrary, that the flaming sword was only drawn from its sheath to drive the innocent from the terrestrial paradise, and close the gates against them.

Book XXV: Chapter 13: I assist Monsieur de Villèle and Monsieur de Corbière to their first Ministry – My letter to the Duc de Richelieu – A note from the Duc de Richelieu and my reply – A note from Monsieur de Polignac – Letters from Monsieur de Montmorency and Monsieur de Pasquier

BkXXV:Chap13:Sec1

However, the complication of events had still resolved nothing. The assassination of Monsieur the Duc de Berry had led to the fall of Monsieur Decazes, which did not happen without a wrench. Monsieur the Duc de Richelieu would only consent to grieve his old master after a promise from Monsieur Pasquier of Monsieur Decazes’ receiving a foreign mission. He left for the London embassy where I was to replace him. Everything was incomplete. Monsieur de Villèle remained on the sidelines with his shadow, Monsieur de Corbière. I for my part presented a considerable obstacle. Madame de Montcalm never ceased urging me to make peace: I was very well disposed to do so, only wishing sincerely to emerge from the problems which enveloped me and for which I had a sovereign contempt. Monsieur de Villèle, though more flexible, was not easy to handle at that time.

There are two ways to become a minister; the one way is brusquely and by force, the other is by patience and skill; the first method was not Monsieur de Villèle’s approach: cunning excludes energy, but it is more certain and less likely to lose the position it gains. The essentials of this latter method are to accept many rebuffs, and to know how to swallow a tangle of snakes: Monsieur de Talleyrand made great use of this second system for satisfying his ambitions. In general, one achieves an entry into office by means of the mediocre elements in one’s character, and remains there because of the superior ones. This combination of opposing factors is a rare thing, and that is why there are so few Statesmen.

Monsieur de Villèle had precisely the sort of down-to-earth qualities which opened the door for him: he ignored the noise around him, in order to gather the fruits of the fear that had gripped the Court. Now and then he made bellicose speeches, but ones where various phrases allowed optimism of a reasonable nature to shine forth. I considered that a man of that type ought to begin by attaining office, no matter how, and in not too precarious a position. It seemed to me that he ought first to become a minister without portfolio, in order to obtain the Presidency of that same administration one day. That would give him a reputation for moderation, which would suit him perfectly; it would appear evident that the royalist opposition leader in parliament was un-ambitious, since he would have consented to reign himself in for the benefit of peace. Every man who has been a Minister, no matter by what title, becomes one again: a first ministry is a rung on the ladder to a second; the individual who has worn the embroidered coat retains the odour of his portfolio, which sooner or later finds him again in office.

Madame de Montcalm told me, on her brother’s behalf, that there were no Ministries vacant; but that if my two friends wished to enter the government as Ministers of State without portfolio, the King would be delighted, promising something better later. She added that if I consented to go abroad, I would be sent to Berlin. I replied that it was entirely up to him; as for myself I was always ready to leave and that I would go to the devil if it were the case that kings had some mission to fulfil with their cousin; but that I would only accept exile if Monsieur de Villèle accepted a position on the Council. I also wished to obtain a place for Monsieur Lainé alongside my two friends. I charged myself with this threefold negotiation. I had become the master of French politics through my own efforts. One can scarcely doubt that it was I who achieved Monsieur de Villèle’s first Ministerial appointment, and I who promoted that Mayor of Toulouse’s career.

I found unconquerable obstinacy to be an element in Monsieur Lainé’s character. Monsieur de Corbière did not simply wish to enter the Council; I flattered him with the expectation that the position would also involve the Public Education portfolio. Monsieur de Villèle alone went along with my wishes with repugnance, first raising a thousand objections; his fine intellect and his ambition at last made him agree to move forward: all was arranged. Here is the irrefutable proof of what I have just said; tedious documents full of small matters which have rightly passed into oblivion, but useful to my own history:

‘20th of December, 3.30pm

TO MONSIEUR THE DUC DE RICHELIEU

I have had the honour of passing by your house, Monsieur le Duc, to give you an account of the state of affairs: all is going on marvellously. I have seen our two friends: Villèle at last consents to become a Minister as a Secretary of State for the Council, without portfolio, if Corbière will consent to do the same, with the same title, and with control of the Education portfolio. Corbière, for his part, is very happy to accept those conditions, assuming Villèle’s agreement. Thus there is no longer a difficulty. Complete your labours, Monsieur le Duc; see our two friends; and when you have heard what I have written from their own mouths, you can render France peaceful internally, as you have given her peace abroad.

Allow me to suggest a further idea to you: would you find it a great inconvenience to grant Monsieur de Villèle the post left vacant by Monsieur de Barante’s retirement? He would then be placed in a position more equal to that of his friend. However, he has stated to me in positive terms that he will consent to enter the Council, without portfolio, if Corbière takes Education. I only say this as a means of satisfying the Royalists more completely, and securing you an immense and unshakeable majority.

Lastly I have the honour to draw to your attention that tomorrow evening the grand reunion of Royalists takes place at Piet’s, and it would be very useful if our two friends could say something tomorrow evening which might calm the excitement and prevent any division.

As I am not involved, Monsieur le Duc, in the outcome of all this, you will, I hope, interpret my eagerness merely as the loyalty of a man who desires his country’s good and your success.

Accept, I beg you, Monsieur le Duc, the assurance of my highest regard.

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

‘Wednesday.

I have just written to Messieurs de Villèle and de Corbière, Monsieur, and committed them to spending the evening with me, since in so vital a matter not a moment should be lost. I must thank you for having progressed everything so swiftly; I trust that we will achieve a satisfactory conclusion. Be assured, Monsieur of the pleasure I take in being under this obligation to you, and receive the assurance of my highest regard.

RICHELIEU.’

‘Allow me to congratulate you, Monsieur le Duc, on the happy outcome of this important matter, and to applaud myself for having played a part in it all. It would be very desirable for the announcement to be made tomorrow: it would put an end to all opposition. In that connection, I can be useful to our two friends.

I have the honour, Monsieur le Duc, to renew my assurance to you of my highest regard.

CHATEAUBRIAND’

‘Friday.

I have received with extreme pleasure the note which Monsieur le Vicomte de Chateaubriand has done me the honour of writing to me. I think he will have nothing to repent of in his reliance on the King’s kindness, and, if he will permit me to so add, on the desire I have of contributing to whatever might be agreeable to him. I beg him to accept the assurance of my highest regard.

RICHELIEU.’

‘Thursday.

My noble colleague, you will no doubt be aware that the business has been concluded this evening at eleven, and all is settled on the basis agreed between you and the Duc de Richelieu. Your intervention has been very helpful to us: thanks are due to you for this step towards the improvement in the situation that from now on can be considered likely.

Yours throughout life,

J. DE POLIGNAC.’

‘Paris, Wednesday the 20th of December, 11.30 at night.

I have just visited your house where you are asleep, dear Vicomte: I came from Villèle who himself returned late from the meeting which you arranged and of which you had informed him. He asked me, as your nearest neighbour, to let you know what Corbiere also wishes to inform you of, namely that the business of the day that you primarily conducted and managed has finally been agreed in the simplest and briefest manner: he without portfolio, his friend taking Education. He seemed to think that, by waiting a little, further conditions could have been exacted; but he agreed not to thwart a spokesman and negotiator such as you. Truly you have opened up a new career for them both: they count on you to make all smooth for them. On your side, during the little time in which we yet have the advantage of your being among us, speak to your most energetic friends on the subject of furthering or at least not hindering the project of closer union. Good night. I further compliment you on the promptness with which you led the negotiation. You will arrange matters in Germany thus, so as to return the more swiftly to your friends. I am delighted, for my part, in the improvement in your own situation.

I reaffirm all my sentiments towards you.

MONSIEUR DE MONTMORENCY.’

‘Here is, Monsieur, a request addressed by a Guard of the King’s Corps to the King of Prussia: it has been handed to me on the recommendation of a senior Guards officer. I beg you to take it with you and make use of it, if you believe, when you have had a little time to examine the situation in Berlin, that it is of the kind to command any chance of success.

It is with great pleasure that I take this opportunity of congratulating you and myself on this morning’s Moniteur, and to thank you for the part you played in this happy outcome which, I hope, will have a fortunate influence on the affairs of France.

Please accept the assurance of my highest regard and my sincere attachment.

PASQUIER.’

This sequence of notes shows that I am not over-egging my activities; it was a great bother to me to buzz around like that; the shafts or the coachman’s nose are not places I ever had the ambition to perch on: whether the coach arrives at the top, or rolls back down to the bottom, matters little to me. Accustomed to living concealed in my own depths, or momentarily in the wider life of the centuries, I have no taste for the mysteries of the antechamber. I fail badly when circulating as a piece of today’s coinage; to protect myself I withdraw closer to God; a preoccupation sent from above isolates you, and makes everything around you die away.

End of Book XXV