François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXIV: Napoleon - St Helena: 1815-1821

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXIV: Chapter 1: Bonaparte at Malmaison – Universal desertion

- Book XXIV: Chapter 2: Departure from Malmaison – Rambouillet – Rochefort

- Book XXIV: Chapter 3: Bonaparte takes refuge with the English fleet – He writes to the Prince Regent

- Book XXIV: Chapter 4: Bonparte aboard the Bellerephon – Torbay – The Act confining Bonaparte to St Helena – He transfers to the Northumberland and sets sail

- Book XXIV: Chapter 5: An assessment of Bonaparte

- Book XXIV: Chapter 6: Bonaparte’s character

- Book XXIV: Chapter 7: Whether Bonaparte has left us in renown the equivalent of what he has taken from us by force?

- Book XXIV: Chapter 8: The uselessness of the truths revealed above

- Book XXIV: Chapter 9: The island of St Helena – Bonaparte travels the Atlantic

- Book XXIV: Chapter 10: Napoleon lands on St Helena – His establishment at Longwood – Precautions – Life at Longwood – Visits.

- Book XXIV: Chapter 11: Manzoni – Bonaparte’s illness – Ossian – Napoleon’s daydreams by the sea – Projects of escape – Bonaparte’s last occupation – He lies down and does not rise again – He dictates his will – Napoleon’s religious sentiments – Vignali the Chaplain – Napoleon argues with Antomarchi, his doctor – He receives the last sacraments – He dies

- Book XXIV: Chapter 12: Funeral rites

- Book XXIV: Chapter 13: The destruction of Napoleon’s world

- Book XXIV: Chapter 14: My last comments on Napoleon

- Book XXIV: Chapter 15: St Helena since Napoleon’s death

- Book XXIV: Chapter 16: Bonaparte’s exhumation

- Book XXIV: Chapter 17: My visit to Cannes

Book XXIV: Chapter 1: Bonaparte at Malmaison – Universal desertion

BkXXIV:Chap1:Sec1

If a man were suddenly transported from life’s most clamorous scenes to the silent shores of the icy ocean, he would experience what I experience beside Napoleon’s tomb, since we are now, in an instant, beside that tomb.

Leaving Paris on the 25th of June, Napoleon awaited at Malmaison the moment of his departure from France. I return to him there: I shall not leave him, revisiting past days, and anticipating the future, until after his death.

Malmaison, where the Emperor stayed, was empty. Joséphine was dead; Bonaparte found himself alone in that retreat. There his good fortune had begun; there he had been happy; there he had become intoxicated with the incense of the world; there, from the heart of that tomb, had issued orders which shook the world. In those gardens, where the feet of the mob had once scarred the sandy paths, grass and brambles grew green; I discovered this when walking there. Already, for want of attention, the exotic trees were pining away; the black Australian swans no longer glided along the canals; the aviary no longer caged its tropical birds: they had flown away to await their host in their native land.

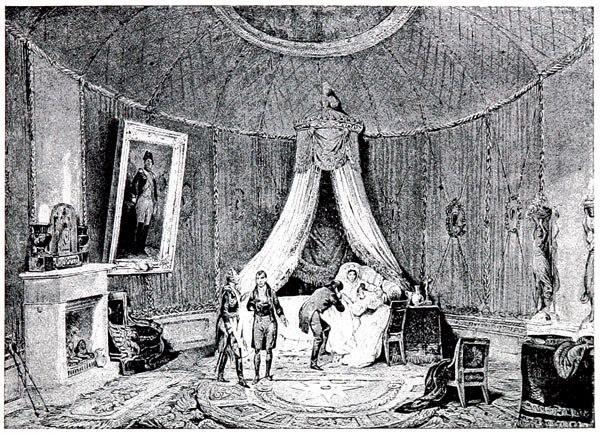

‘Mort de l'Impératrice Joséphine à la Malmaison, d'Après le Dessin et la Lithographie de Tirpenne et Monthelier (Collection Hennin)’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p917, 1888)

The British Library

Bonaparte was able to find matter for consolation however in turning his gaze back on his early days: fallen kings grieve above all because they still perceive the hereditary splendour and the pomp of their cradles that preceded their fall: but what could Napoleon discover ante-dating his prosperity: a nursery crib in a Corsican village? Grown more magnanimous in doffing his purple mantle, he should have donned with pride the goatherd’s smock; but men never conceive of themselves in the humble surroundings from which they originated; it seems that an unjust heaven deprives them of their patrimony when the lottery of fate forces them to lose what they have gained, and moreover Napoleon’s grandeur arose from what issued from himself: none of his race had preceded him in preparing the road to power.

At the sight of those abandoned gardens, those uninhabited rooms, those galleries faded from entertainments, those rooms in which music and song had ceased, Napoleon could review his career: he could ask himself whether a little more moderation might have maintained his happiness. They were not foreigners and enemies who were banishing him now; he was not going away a quasi-victor, leaving the nations lost in admiration of his passage, after that prodigious campaign of 1814; he was retiring defeated. Frenchmen, his friends, were urging his immediate abdication, pressing him to depart, not desiring him to remain even as a general, sending him courier after courier, obliging him to quit the soil over which he had poured glory as much as suffering.

To this harsh lesson were added other warnings: the Prussians were on the prowl in the neighbourhood of Malmaison: Blücher, reeling about drunkenly, ordered them to seize and hang that conqueror who had dared to set his foot on the necks of kings. The rising fortunes, vulgarity of manners, speed of elevation, and degree of abasement of modern men will, I fear, deny our times the nobility we find in history: Greece and Rome did not talk of hanging Alexander or Caesar.

The scenes which had taken place in 1814 were repeated in 1815, but with something more offensive about them, because the ingrates were moved by fear: they had to get rid of Napoleon quickly; the Allies were arriving; Alexander was not there initially, to temper the sense of triumph and curb the insolence of victory; Paris was no longer adorned with its sacred inviolability, that first invasion had profaned the sanctuary; it was no longer God’s wrath that was falling upon us, it was Heaven’s scorn: the lightning-bolt had extinguished itself.

All the cowards had acquired a fresh degree of malignity during the Hundred Days; affecting, through love of country, to rise above personal attachments, they cried out that Bonaparte had been only too criminal in violating the treaties of 1814. But the true culprits, were they not those who had supported his plans? If, in 1815, having deserted him once and in order to desert him again, instead of re-creating his armies, they had said to him, after he had taken up residence in the Tuileries: ‘Your genius is in error; opinion is no longer with you; take pity on France. Retire, after this last visit to our soil; go and live among Washington’s citizens. Who knows if the Bourbons will not prove to be a mistake? Who knows if one day France will not turn its gaze towards you, at a time when, in the school of liberty, you shall have learnt respect for its laws? You may return them, not as a raptor swooping on its prey, but as a great citizen, the pacifier of his country.’

They did not use that language to him: they gave full reign to their passions; they helped to blind him, certain they would profit from his victory or his defeat. His soldiers alone died for Napoleon with an admirable sincerity; the rest were no more than a grazing herd, fattening themselves to right and left. If only the Viziers of the despoiled Caliph had been content to turn their back on him! But no: they profited from his final moments; they overwhelmed him with sordid demands; all wished to make money out of his poverty.

There was never such a complete desertion; Bonaparte was responsible for it: insensible to others’ troubles, the world repaid him with indifference for indifference. Like most despots, he was good to his servants; at heart he cared for no one: a solitary man, he was self-sufficient; misfortune merely returned him to the wilderness that was his life.

When I gather my memories together, when I recall having seen Washington in his little house in Philadelphia, and Bonaparte in his palace, it seems to me that Washington, retiring to the fields of Virginia, cannot have experienced the regrets that Bonaparte experienced, awaiting exile in the gardens at Malmaison. Nothing had changed in the life of the former; he returned to his modest habits; he had not elevated himself above the happiness of the ploughmen he had liberated; but everything in the life of the latter was overthrown.

Book XXIV: Chapter 2: Departure from Malmaison – Rambouillet – Rochefort

BkXXIV:Chap2:Sec1

Napoleon left Malmaison accompanied by Generals Bertrand, Rovigo, and Beker, the latter acting in the capacity of warder or commissary. On the way, he was seized with a desire to stop at Rambouillet. He left it, to embark at Rochefort, as Charles X had, to embark at Cherbourg; Rambouillet, the inglorious retreat where all that was greatest in men or their race was eclipsed; the fatal place where Francois I died; where Henri III, escaping from the barricades, slept booted and spurred; where Louis XVI left his shadow behind! How fortunate Louis, Napoleon, and Charles would have been, if they had merely been humble shepherds of the flocks at Rambouillet!

Arriving in Rochefort, Napoleon hesitated: the Executive commission sent out peremptory orders: ‘The garrisons of Rochefort and La Rochelle,’ said these despatches, ‘must use main force to ensure Napoleon takes ship. Make him go. H services cannot be accepted.’

Napoleon’s services could not be accepted! And had you not accepted his gifts and his chains? Napoleon did not go away; he was driven off: and by whom?

Bonaparte had only believed in good fortune; he gave no thought to misfortune; he absolved the ungrateful in advance: a just retribution made him submit to his own system. When success ceased to animate his person and became incarnate in another individual, the disciples abandoned the master to follow the school. If I, who believe in the legitimacy of gifts and the sovereignty of misfortune, had served Bonaparte, I would not have left him; I would have proved to him, by my loyalty, the falsity of his political principles; while sharing his disgrace, I would have remained at his side, a living contradiction to his sterile doctrines and the worthlessness of the rule of prosperity.

Since the 1st of July, frigates had been waiting for him in the Rochefort roads: hopes which never die, memories inseparable from a final farewell, detained him. How he must have regretted his childhood days when his serene gaze had not yet seen the first raindrops fall! He gave the English fleet time to approach. He could still have embarked on one of two luggers which were due to join a Danish ship at sea (this was the course adopted by his brother Joseph); but his resolution failed him as he gazed at the coast of France. He had an aversion for Republics; the liberty and equality espoused by the United States was repugnant to him. He was inclined to demand asylum of the English: ‘What disadvantage do you see in that course?’ he asked those he consulted. – ‘The disadvantage of dishonouring you’, a naval officer replied: ‘You must not fall into the hands of the English, dead or alive. They will have you stuffed and exhibit you at a shilling a head.’

Book XXIV: Chapter 3: Bonaparte takes refuge with the English fleet – He writes to the Prince Regent

BkXXIV:Chap3:Sec1

Despite these comments, the Emperor resolved to give himself up to his conquerors. On the 13th of July, Louis XVIII having already been in Paris five days, Napoleon sent the captain of the English ship Bellerophon the following letter, addressed to the Prince Regent:

‘Royal Highness,

Prey to the factions which are dividing my country, and the enmity of the greatest powers of Europe, I have ended my political career, and I come, like Themistocles, to ‘sit at the hearth’ of the British people. I place myself under the protection of their laws, which I ask of Your Royal Highness as the most powerful, most constant and most generous of my enemies.

Rochefort, the 13th of July, 1815.’

If Bonaparte had not for twenty years heaped outrage upon the English people, their government, their King and the King’s heir, one might be able to find some propriety of tone in this letter; but how had this Royal Highness, so despised and insulted by Napoleon, suddenly become the most powerful, most constant, and most generous of enemies, merely by being victorious? Napoleon could not have been convinced of what he was saying: and these days what is not true is not eloquent. The phrases that reveal the fact of fallen greatness addressing itself to an enemy are fine; the banal example of Themistocles is superfluous.

There is something worse than a lack of sincerity in the step Bonaparte took; there is a lack of consideration for France: the Emperor was pre-occupied only by his personal disaster; when the fall came, we no longer counted for anything in his eyes. Without reflecting that in giving England the preference over America, his choice represented an insult to national grief, he solicited asylum from a government that, for twenty years, had paid Europe to fight against us, from a government whose Commissioner with the Russian Army, General Wilson, had urged Kutuzov, during the retreat from Moscow, to finish us off completely: the English, fortunate in the final battle, were camped in the Bois de Boulogne. Go then, Themistocles, and sit quietly by the British hearth, while the earth has not yet finished drinking the French blood shed for you at Waterloo! What part would the fugitive have played, if he had been entertained on the banks of the Thames, with France invaded, and Wellington dictator of the Louvre? Napoleon’s noble fate served him better: the English allowing themselves to be drawn into a short-sighted and spiteful policy lacked a final triumph; instead of humiliating their supplicant by admitting him to their castles and their banquets, they rendered the crown they thought they had taken from him brighter for posterity. He grew greater in his captivity by virtue of the fear instilled in all the Powers: in vain the Ocean enchained him, Europe in arms camped on the shore, her gaze fixed on the sea.

Book XXIV: Chapter 4: Bonparte aboard the Bellerephon – Torbay – The Act confining Bonaparte to St Helena – He transfers to the Northumberland and sets sail

BkXXIV:Chap4:Sec1

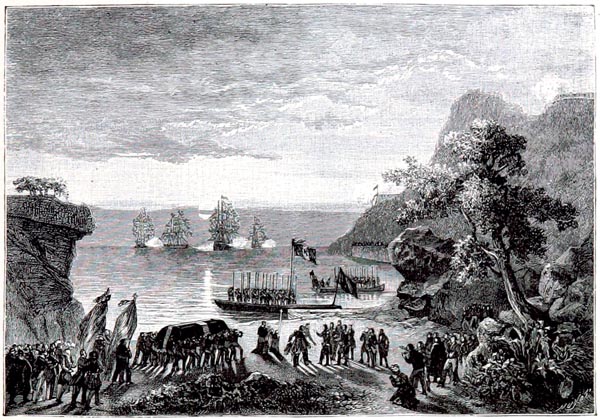

On the 15th of July, the Épervier conveyed Bonaparte to the Bellerephon. The French boat was so small that, from the deck of the English vessel, they could not see the giant riding the waves. The Emperor, accosting Captain Maitland, said: ‘I come to place myself under the protection of the laws of England.’ For once at least the contemner of the laws admitted their authority.

The fleet sailed for Torbay: a host of ships cruised around the Bellerephon; the same excitement was shown at Plymouth. On the 30th of July, Lord Keith notified the supplicant of the act which confined him to St Helena: ‘That is worse than Tamerlane’s cage,’ Napoleon said.

This violation of the rights of man, and of respect for hospitality, was disgusting: if you first see the light of day on any ship, provided it is under sail, you are English born; by virtue of the age-old customs of London, the waves are considered the soil of Albion. And yet an English ship was not an inviolable altar for a suppliant, it did not place the great man who embraced the Bellerephon’s stern under the protection of the British trident! Bonpaarte protested; he argued points of law, spoke of treachery and perfidy, and appealed to the future: yet had he not, in his might, trampled underfoot the sacred things whose guardianship he now invoked? Had he not carried off Toussaint-Louverture and the King of Spain? Had he not had English travellers, who happened to be in France at the time of the breaking of the Peace of Amiens, arrested and imprisoned for years? It was permissible therefore for mercantile England to imitate what he had done himself, and inflict an ignoble reprisal; but she could have acted differently. Civil rights and the rights of man were violated in the person of the Duc d’Enghien; yet the heroic race of the Condés never claimed a drop of blood from the immortal soldier on his defeat. Monsieur Dupin’s letter makes known to us the generosity of the unfortunate Duc de Bourbon regarding his son’s remains. (See Book Sixteen of these Memoirs.)

Napoleon’s heart did not match his head in greatness; his quarrels with the English are deplorable; they revolted Lord Byron. How could he deign to honour his gaolers with even a word? It is painful to see him stoop to verbose conflicts with Lord Keith at Torbay, and with Sir Hudson Lowe at St Helena, issuing memos because they break faith with him, quibbling about a title, or a little more or less gold or honours. Bonaparte confined to himself, was confined to his glory, and that ought to have sufficed: he had nothing to ask of men; he failed to treat adversity despotically enough; one could have forgiven him for making a last slave of fortune. I find nothing remarkable in his protest against the violation of the laws of hospitality except the place and signature attached to that protest: ‘On board the Bellerephon, at sea: Napoleon.’ The harmonies of immensity are at play there.

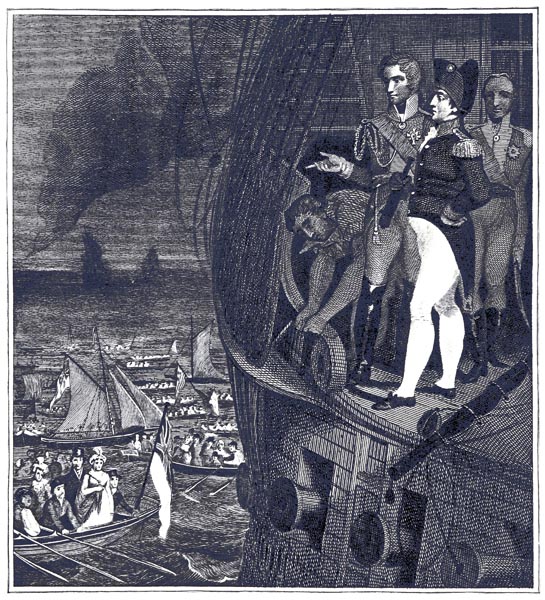

‘Bonaparte on Board the Belerophon off Plymoth’

A Full and Circumstantial Account of the Memorable Battle of Waterloo... - Christopher Kelly (p302, 1817)

The British Library

From the Bellerephon, Bonaparte was transferred to the Northumberland. Two frigates burdened with the future garrison of St Helena escorted him. Some of the officers of that garrison had fought at Waterloo. This explorer of the globe was allowed to have with him Monsieur and Madame Bertrand, and the Messieurs de Montholon, Gourgaud, and de Las Cases, willing and generous passengers on a submerged plank. According to an article in the Captain’s instructions, Bonaparte was to be disarmed: Napoleon alone, prisoner on a vessel, in the midst of the Ocean, disarmed! What magnificent terror his power invoked! But what a lesson of Heaven’s to men who abuse the sword! The stupid Admiralty treated like a Botany-Bay felon this grand convict of the human race: did the Black Prince disarm King Jean?

The squadron weighed anchor. Since the boat that carried Caesar, no vessel has been burdened with a like destiny. Bonaparte drew near to that sea of miracles over which the Arabs of Sinai had seen him pass. The last Napoleon saw of the French coast was Cape la Hague; scene of another English victory.

The Emperor was mistaken as to the degree of interest in him, when he expressed the desire to remain in Europe; he would soon have become merely a commonplace, withered prisoner: his old role was finished. But the new location carried him to fresh fame, beyond that role. No man of similar renown has had a like end to Napoleon’s. He was not, as after his first fall, proclaimed the autocrat of a few iron and marble quarries, the former to provide him with a sword, the latter a bust; eagle that he was they gave him a rock, on the point of which he remained in the sunlight until his death, in full view of the whole world.

Book XXIV: Chapter 5: An assessment of Bonaparte

BkXXIV:Chap5:Sec1

At the instant when Bonaparte is leaving Europe, abandoning life in order to seek his destined death, it is appropriate to examine this man of dual existence, to portray the true Napoleon and the false: they blend and form a whole, in their mixing of reality and myth. I ask you to bear in mind what I have previously said about the man, in speaking about the death of the Duc d’Enghien, in showing him in action in Europe before, during and after the Russian Campaign; and in giving an account of my pamphlet ‘De Bonaparte et des Bourbons’. The parallel drawn with Washington in the sixth book of these Memoirs also throws some light on Napoleon’s character.

From the combination of these observations, it can be seen that Bonaparte was a poet in action, an immense genius in warfare, an indefatigable, able and intelligent mind where administration was concerned, a thorough and rational legislator. That is why he has such a hold on the popular imagination, and such authority over the decisions of practical men. But as a politician he will always appear deficient in the eyes of Statesmen. This observation, made inadvertently by most of his panegyrists, will, I am convinced, become the definitive judgement regarding him; it explains the contrast between his prodigious efforts and their pitiful results. At St Helena, he himself severely condemned his political activity in two regards: the War in Spain and the War in Russia; he might have broadened his confession to include other sins. His admirers will surely not maintain that he was wrong when blaming himself? Let us recapitulate:

Bonaparte acted in defiance of all prudence, without yet again speaking of the odiousness of the deed, in killing the Duc d’Enghien: he attached a burden to his life. Despite his puerile apologists, that death, as we have seen, was the hidden catalyst of the discord which subsequently broke out between Alexander and Napoleon, as also between Prussia and France.

The assault on Spain was wholly improper: the Peninsula belonged to the Emperor; he could have turned it to the most profitable account: instead, he made it a training-ground for English soldiers, and the cause of his own destruction through a nation’s rebellion.

The detention of the Pope, and the annexation of the Papal States by France, were tyrannical whims by which he lost the advantage of passing for a restorer of religion.

Bonaparte did not halt, as he should have done, once he had married a daughter of the Caesars: Russia and England were appealing for mercy.

He did not revive Poland, when the security of Europe depended upon re-establishing that kingdom.

He hurled himself at Russia despite the representations of his Generals and counsellors.

Madness having set in, he went on beyond Smolensk; everyone told him that he ought not go further at a first attempt, that his first Campaign in the North was over and a second (he felt it himself) would make him master of the Empire of the Tsars.

He was incapable of computing the days or foreseeing the effect of the climate, things everyone in Moscow computed and foresaw. Read too what I wrote regarding the Continental Blockade and the Confederation of the Rhine; the first a vast concept, but a dubious act; the second a considerable achievement but spoilt in execution by a campaign mentality and monetary instincts. Napoleon received as a gift the old French monarchy as it had been created by the centuries and by an uninterrupted succession of great men, as Louis XIV’s majesty and Louis XV’s alliances had left it, as the Republic had enlarged it. He seated himself on that magnificent pedestal, stretched out his arms, seized hold of nations, and gathered them round him; but he lost Europe as swiftly as he had won it; he twice brought the Allies to Paris, despite the miracles of his military intelligence. He had the world at his feet and all he earned from it was a prison for himself, exile for his family, and the loss of all his conquests plus a measure of the former French territories.

That is history, demonstrated by facts which no one can dispute. Where did the errors I have just indicated stem from; errors followed by so speedy and fatal a collapse? They stemmed from Napoleon’s inadequacies as a politician.

In his alliances he enslaved other governments by conceding territory, whose borders he would soon alter; constantly showing a tendency to take back what he had given, always making himself felt as the oppressor; re-organising nothing after his invasions, with the exception of Italy. Instead of halting after each step, to build up behind him, in another form, what he had overthrown, he continued to advance through the ruins: he travelled so quickly he barely had time to take breath wherever he passed. If, by some kind of Treaty of Westphalia, he could have ordered and assured the existence of the various States within Germany, Prussia and Poland, then, on his first retrograde march, he could fallen back on settled populations and found shelter among them. But his poetic edifice of victories, lacking a foundation, and only suspended in air by his genius, fell when his genius began to fail. The Macedonian founded Empires at the double, Bonaparte, as he ran, only knew how to destroy; his sole aim was to be master of the world in his own person, without worrying about how to preserve it.

People have wished to make Bonaparte appear as a perfect being, the type of feeling, sensitivity, morality and justice, a writer like Caesar or Thucydides, an orator or historian like Demosthenes or Tacitus. Napoleon’s public speeches, his words from council chamber or tent are less inspired by prophetic breath than by announcements of unaccomplished catastrophe. While the Isaiah of the sword himself has vanished, his prophecies regarding Nineveh which dogged States without touching or destroying them remain puerile rather than sublime. Bonaparte in truth was Destiny for sixteen years: Destiny is silent, and Bonaparte ought to have been so. Bonaparte was no Caesar; his education was neither learned nor select; half a foreigner, he was ignorant of the basic rules of our language: what did it matter, after all, if his speech was faulty? He issued orders to the world. His bulletins have the eloquence of victory. Sometimes, intoxicated with success, men affected to embroider them on a drum; in the midst of gloomy tones there rose fatal bursts of laughter. I have read carefully what Bonaparte wrote, his first childish manuscripts, his novels, then his pamphlets in letter form to Buttafuoco, le Souper de Beaucaire, his private letters to Josephine, his five volumes of speeches, his orders and bulletins, and his unpublished dispatches ruined by the editing carried out by Monsieur de Talleyrand’s office. I know a lot about it: I only recently discovered, in a vile autograph copy left on the Island of Elba, various thoughts which echo the nature of the great islander:

‘My heart rejects familiar joys as it does commonplace sorrows.’

‘Not having given myself life, I will not deprive myself of it, as long as it demands something fine of me.’

‘My evil genius appeared and announced my end, which I met at Leipzig.’

‘I have conjured the terrible spirit of novelty which traverses the world.’

Something of the true Bonaparte is certainly captured there.

If Bonaparte’s bulletins, speeches, allocutions, and proclamations are distinguished by energy, that energy does not truly belong to him; it was of the age, it derived from revolutionary inspiration which weakened in Bonaparte, because he marched in opposition to that inspiration. Danton said: ‘Metal seethes; if you don’t keep an eye on the furnace you’ll get burnt.’ Saint-Just said: ‘Dare!’ That word contains all of our Revolutionary politics; those who make half-revolutions only dig a grave for themselves.

Are Bonaparte’s bulletins nobler than this proud phrase-making?

As for the numerous volumes published under the title of Memoirs of St Helena, Napoleon in Exile etc., etc., etc., those documents, received from Bonaparte’s lips, or dictated by him to various people, have a few fine passages on warfare, a few remarkable assessments of certain men; but in the end Napoleon is only concerned with creating his apology, justifying his past, building, on nascent ideas and completed events, things which he never dreamed of during the course of those events. In that compilation, where for and against succeed one another, where each opinion finds a favourable authority and a peremptory refutation, it is difficult to untangle that which belongs to Napoleon and that which belongs to his secretaries. It is probable that he produced a different version for each of them, so that his readers might choose according to their taste, and create in future any Napoleon they wished. He dictated his history such as he wished to leave it; he was an author writing articles about his own work. Nothing then is more absurd than to go into raptures over this collection from many hands, which is not like Caesar’s Commentaries a short work, emerging from a great mind, composed by a superior writer; and yet those brief commentaries, so Asinius Pollio thought, were neither exact nor faithful. The Memorial de Saint-Hélène is fine, written throughout with candour and naïve admiration.

One of the things which most contributed to rendering Napoleon detestable in his lifetime, was his penchant for degrading everything: in a burning town, he coupled decrees regarding the re-establishment of theatres, with orders suppressing monarchies; a parody of the omnipotence of God, who rules the fate of the world and of an ant. With the fall of empires he mingled insults to women; he took pleasure in the abasement of what he had brought down; he slandered and injured especially whoever dared to resist him. His arrogance equalled his good fortune; he thought himself all the greater for dragging others down. Jealous of his generals, he accused them of his own faults, since as far as he was concerned he had no flaws. Contemptuous of all people of merit, he reproached them harshly for their mistakes. He would not have said, as Louis XIV did to Marshal Villeroi, after the disaster of Ramillies: ‘Monsieur le Maréchal, at our age one is never fortunate.’ A touching magnanimity, that was unknown to Napoleon. The age of Louis XIV was created by Louis the Great: his own age made Bonaparte.

The Emperor’s history, modified by false accounts, was distorted even further by the state of society in the Imperial epoch. Every Revolution reported by a free Press enables the facts to be seen in depth, since everyone describes them as they see them: Cromwell’s reign is known about, because people told the Protector what they thought about his actions and his person. In France, even under the Republic, despite the inexorable censure of the executioner, truth emerged; the same faction was not always victorious; each succumbed quickly, and the succeeding faction informed you as to what its precursor had hidden from you: between one scaffold and another, between two severed heads, there was freedom. But when Bonaparte seized power, and speech was gagged, and only the voice of despotism was heard which never spoke except in praise of itself and allowed discussion of nothing but itself, truth vanished.

The authentic pieces, so-called, from that time are corrupt: nothing was published, neither books nor newspapers, except at the master’s bidding: Bonaparte watched over the Moniteur articles; his Prefects sent back citations, congratulations, and felicitations from the various departments as the authorities in Paris had dictated and transmitted them, expressing public opinion as it was agreed to be, quite different from that opinion in actuality. Write history using these same documents! As proof of the impartiality of your material, evaluate the authenticity of what you have drawn on: you will be quoting only lies based on lies.

If one casts doubt on this universal deception, if men who saw nothing of the days of the Empire insist on treating as genuine whatever they find in the published documents, or even what they can dig out of the Ministerial archives, it is only necessary to refer to an irrefutable witness, to the Senate Conservateur: there, in a decree I have cited above, you have read their own words: ‘Considering that the freedom of the press, .has been constantly subjected to arbitrary police censure, and that at the same time he has continually used the press to fill France and Europe with fabricated information, and false maxims.that the acts and reports, heard by the Senate, have been subject to alteration in the process of publication; etc.’ What can there be to say to that declaration?

Bonaparte’s life was an incontestable reality that deception has been charged with documenting.

Book XXIV: Chapter 6: Bonaparte’s character

BkXXIV:Chap6:Sec1

Monstrous pride and incessant affectation spoilt Napoleon’s character. At the time of his supremacy, what need had he to exaggerate his stature, when the Lord of Hosts had furnished him with that chariot ‘with living wheels’.

He had Italian blood; his nature was complex: great men, a very small family on earth, unfortunately find no one but themselves to imitate them. At once a model and a copy, a real person and an actor playing that person, Napoleon was his own mimic; he would not have believed himself a hero if he had not decked himself out in a hero’s costume. This curious weakness imparted something false and equivocal to his astonishing reality; one is in fear of mistaking the King of Kings for Roscius, or Roscius for the King of Kings.

Napoleon’s qualities are so adulterated in the gazettes, pamphlets and verses, and even the popular songs imbued with Imperialism, that those qualities are completely unrecognizable. All the touching things attributed to Bonaparte in the Anecdotes about prisoners, the dead, the soldiers are nonsense, given the lie by his life’s actions.

The Grandmother of my illustrious friend Béranger is merely an admirable ballad: Bonaparte had nothing good-natured about him. Tyranny personified, he was cold; that frigidity formed an antidote to his ardent imagination, in himself he found not words but a reality, and a reality ready to be irritated by the least show of independence: a midge that flew without his permission was to his mind a rebellious insect.

It was not enough to fill the ears with lies, it was necessary to fill the eyes also: here, in an engraving, we see Bonaparte taking his hat off to the Austrian wounded; there we have a little soldier-boy preventing the Emperor’s passage; farther on Napoleon touches the plague-victims at Jaffa when he never touched them in fact; or he crosses the St Bernard Pass on a high-spirited horse in snowy weather, when in fact it was as fine as could be.

Is there not a wish now to transform the Emperor into a Roman of the early days of the Aventine, into a missionary of liberty, a citizen who instituted slavery only through love of its virtuous opposite? Judge from two actions of the great founder of equality: he ordered his brother’s, Jérôme’s, marriage to Miss Patterson to be annulled, because Napoleon’s brother could only ally himself with the blood of princes; and later, on his return from Elba, he invested the new democratic Constitution with a peerage, and crowned it with the Supplementary Act.

‘Jerome Bonaparte, After the Engraving by Read’

Memoirs of Madame Junot (Duchesse D'Abrantès) - Laure Junot Abrantès, Duchesse d' (p194, 1895)

Internet Archive Book Images

‘Elisabeth Paterson Bonaparte’

Silhuetter: Magdalene Thoresen, Emma Dahl, Camilla Collett, Hanna Ouchterlony, Elisa Paterson Bonaparte Dronning Sophie - Clara Tschudi (p126, 1898)

Internet Archive Book Images

That Bonaparte, continuator of the Republic’s success, disseminated principles of freedom everywhere, that his victories helped to loosen the bonds between nations and their kings, freeing those peoples from the force of old customs and ancient concepts; that, in this sense, he contributed to social emancipation, I do not pretend to deny: but that he deliberately worked for the civil and political deliverance of countries, of his own free will; that he established the strictest of tyrannies with the idea of giving Europe, and France in particular, the widest possible constitution; that he was really a tribune disguised as a despot, that is a supposition I find impossible to accept.

Bonaparte, like the race of princes, wished for and sought only the arbitrary, arriving there however on the back of liberty, since he arrived on the world scene in 1793. The Revolution, which was Napoleon’s wet nurse, quickly seemed to him an enemy; he never ceased opposing it. The Emperor, moreover, was well aware of evil when the evil did not emanate directly from the Emperor; since he was not lacking in moral sense. Sophisms advanced regarding Bonaparte’s love of liberty prove only one thing, how one can abuse reason; now it lends itself to any argument. Has it not been established that the Terror was a time of humanity? Indeed, was not the abolition of the death-penalty demanded, while everyone was being killed? Have not great civilisers, as they are called, always murdered human beings, and is it not for that reason, as has been proved, that Robespierre was the heir of Jesus Christ?

The Emperor involved himself in everything; his mind never rested; he had a sort of perpetual agitation of ideas. With his impetuous nature, instead of steady and continuous progress, he advanced by leaps and bounds, threw himself at the world and shook it; he wanted none of that world, if he was obliged to wait for it: an incomprehensible being, who found a way to abase his loftiest actions, by disdaining them, and who raised his least elevated actions to his own level. Impatient of will, patient by nature, incomplete and as it were unfinished, Napoleon possessed lacunae in his genius: his understanding resembled the sky of that other hemisphere beneath which he was to die, that sky whose stars are separated by empty space.

One asks oneself by means of what influence Bonaparte, so aristocratic, such an enemy of the people, came to win the popularity he enjoyed: since that forger of yokes has assuredly remained popular with a nation whose pretension it was to raise altars to liberty and equality; this is the solution to the enigma:

Daily experience shows that the French are instinctively attracted to power; they have no love for freedom; equality alone is their idol. Now, equality and tyranny are secretly connected. In those two respects, Napoleon took his origin from a source in the hearts of the French, militarily inclined towards power, democratically enamoured of the levelling process. Mounting the throne, he seated the people there too; a proletarian king, he humiliated kings and nobles in his ante-chambers; he levelled social ranks not by lowering them, but by elevating them: levelling down would have pleased plebeian envy more, levelling up was more flattering to its pride. French vanity was inflated too by the superiority Bonaparte gave us to the rest of Europe; another cause of Napoleon’s popularity stemmed from the confinement of his last days. After his death, as people became better acquainted with what he had endured on St Helena, they began to pity him; they forgot his tyranny, remembering only that after first conquering our enemies, and subsequently drawing them into France, he had defended us from them; today we conceive that he might have saved us from the disgrace into which we have sunk: we were reminded by his misfortune of his fame; his glory profited by his adversity.

Finally his miraculous feats of arms have bewitched the young, in teaching them to worship brute force. His incredible good fortune has left every ambitious man with the conceited hope of reaching his heights of achievement.

And yet this man, popular as he was for levelling France with his egalitarian roller, was the mortal enemy of equality and the most powerful of organisers of an aristocracy within a democracy.

I cannot acquiesce in the false praise with which Bonaparte has been insulted, by those wishing to justify everything about his conduct; I cannot abrogate my reason, nor wax lyrical about things which arouse my horror or pity.

If I have succeeded in conveying what I have felt, my portrait of him will remain that of one of the premier figures in history; but I will have none of that fantastic creature composed of lies; lies which I saw born, which were recognised at first for what they were, but which have, in time, attained the status of truth, due to the infatuation and mindless credulity of mankind. I refuse to be a silly goose, and fall headlong into a fit of admiration. I endeavour to depict people conscientiously, without robbing them of what they possess, and without granting them what they do not. If success came to be equated with innocence; if, by corrupting posterity, it loaded it with its chains; if that suborned posterity, a slave hereafter, engendered by a slavish past, became the accomplice of whoever was to be victorious, where would the right lie, what would be the point of sacrifice? Good and evil rendered only relative, all morality would be effaced from human action

Such is the problem that glittering fame causes an impartial writer: he ignores it as far as possible, in order to lay bare the truth; but the glory returns like a radiant mist and hides his picture in an instant.

Book XXIV: Chapter 7: Whether Bonaparte has left us in renown the equivalent of what he has taken from us by force?

BkXXIV:Chap7:Sec1

In order not to admit the reduction in territory and power which we owe to Bonaparte, the present generation consoles itself by claiming that what he has taken from us by force, he has given back in glory. ‘Are we not now famous,’ they say, ‘in every corner of the earth? Is not a Frenchman feared, pointed out, known on every shore?’

But were we condemned only to one of those two conditions, immortality without power, or power without immortality? Alexander made the Greek name famous throughout the world; he left Greece no less than four empires in Asia; the language and civilisation of the Hellenes extended from the Nile to Babylon, and from Babylon to the Indus. At his death, his ancestral kingdom of Macedonia, far from being diminished, had increased a hundredfold. Bonaparte spread our fame to every shore; under his command, the French subjugated Europe such that France’s name yet prevails, and the Arc d’Étoile can stand there without seeming a puerile trophy; but before our defeats that monument would have been a witness instead of merely being a chronicle. Yet, had not Dumouriez with his conscripts already dealt the foreigner his first lessons, had not Jourdan won the Battle of Fleurus, Pichegru conquered Belgium and Holland, Hoche crossed the Rhine, Masséna triumphed at Zurich, Moreau at Hohenlinden; all exploits difficult to perform that prepared the way for others? Bonaparte gave unity to those disparate successes; he continued them, he made those victories shine forth: but without those first marvels could he have achieved the last? He rose above all others only when the mind within him was executing the inspirations of the poet.

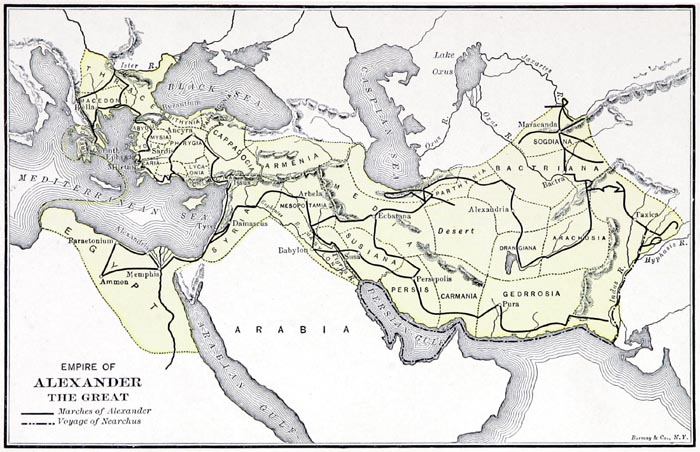

‘The Empire of Alexander the Great’

"A History of Greece for High Schools and Academies - George Willis Botsford (p377, 1899)

The British Library

Our sovereign’s fame cost us a mere two or three hundred thousand men a year; we paid for it with a mere three million of our soldiers; our fellow citizens bought it at the price merely of their sufferings and of fifteen years of their freedom: what do such trifles matter? Are not the generations who come after us resplendent with glory? So much the worse for those who vanished! The disasters which occurred under the Republic ensured the safety of all; our misfortunes under the Empire did much more; they deified Bonaparte! That should suffice us.

It does not suffice me; I refuse to abase myself by hiding my country behind Bonaparte; he did not create France, France created him. No genius, no superiority, will ever induce me to accept a power which can deprive me of my freedom, my home, my friends with a word: if I do not add my wealth and my honour, it’s because one’s wealth does not seem to me worth defending; as for honour, it is immune to tyranny: it is the soul of martyrdom; bonds encompass it but do not enchain it; it pierces prison walls liberating the whole man along with it.

The wrong which a true philosophy will never forgive Bonaparte is that of having accustomed society to passive obedience, thrusting humanity back towards the age of moral degradation, and corrupting the nature of manners, to such a degree perhaps that it is impossible to say when men’s hearts might begin once more to throb with noble feelings. The weakness which has overcome us both in regard to ourselves, and Europe, and our present abasement, are the consequence of Napoleonic slavery: all that remains to us is the ability to bear the yoke. Bonaparte has even disordered the future; it would not astonish me, if, in our sickly impotence we weakened further, barricading ourselves against Europe instead of going out to meet it, giving up our internal freedoms to deliver ourselves from imaginary external dangers, losing ourselves in unworthy precautions, contrary to our genius and the fourteen centuries which have created our national way of life. The atmosphere of despotism Bonaparte left behind him will close around us like a fortress.

The fashion today is to greet liberty with a sardonic smile, to regard it as an old-fashioned concept fallen into disuse, like that of honour. I am unfashionable, I think the world is empty without liberty; it makes life worth living; if I were its last defender, I would never cease to proclaim its rights. To attack Napoleon in the name of past events, to assail him with dead ideas, is to provide him with fresh triumphs. He can be fought only with something greater than himself, namely liberty: he was guilty of offending her and consequently of offending the human race.

Book XXIV: Chapter 8: The uselessness of the truths revealed above

BkXXIV:Chap8:Sec1

Vain words! I feel their uselessness more than anyone. Hereafter all comment, however moderate, will be considered sacrilegious: it takes courage to brave the popular outcry, to ignore the fear of being considered narrow-minded and incapable of sensing or appreciating Napoleon’s genius, solely because despite the true and lively admiration you profess for him, you still cannot sing the praises of his imperfections. The world belongs to Bonaparte; what the destroyer could not manage to conquer, his fame has usurped; living he lost a world, dead he possesses it. You can complain all you like: generations will pass without listening to you. Antiquity had the shade of Priam’s son say: ‘Do not judge Hector by his petty tomb: the Iliad, Homer, the Greeks in flight, those are my sepulchre: I am interred within all those great actions.’

Bonaparte is no longer the real Bonaparte, but a legendary figure fashioned from the poet’s whims, soldiers’ tales, and popular legend; it is a Charlemagne or Alexander of medieval epic we behold today. This hero of fantasy will become the real individual, the other portraits will vanish. Bonaparte was so strongly wedded to absolute domination, that after enduring his tyranny in person, we now have to endure the tyranny of his memory. This latter despotism is more oppressive than the former, since if he was sometimes opposed while he was on the throne, there is universal agreement in accepting the chains he throws around us now he is dead. He is an obstacle to future events: how could power emerging from the army establish itself after him? Has he not killed all military glory in surpassing it? How could a free government arise, when he has corrupted the principle of freedom in men’s hearts? No legitimate power now can drive that usurping spectre from the mind of man: soldier and citizen, republican and monarchist, rich and poor alike place busts and portraits of Napoleon in their homes, whether palace or cottage; the former vanquished agree with the former vanquishers; one cannot move a step in Germany without coming across him, since in that country the younger generation which rejected him has gone. Usually, the centuries sit down before the portrait of a great man, and complete it by lengthy, successive efforts. On this occasion the human race refused to wait; perhaps it was in too much haste to engrave the drawing.

And yet can a whole nation be in error? Is there not a true source from which all the lies emerged? It is time to compare the defective part of the statue with the finished part.

Bonaparte was not great by virtue of words, speeches, writings, or a love of liberty which he never possessed and never intended to foster; he is great in that he created firm and powerful government, a code of laws adopted in various countries, courts of justice, and schools, and a strong, active and intelligent administration which we are still living under; he is great in that he revived, enlightened, and governed Italy superlatively well; he is great in that, in France, he restored order from the midst of chaos, rebuilt the altars, reduced to working for him the savage demagogues, proud scholars, anarchic men of letters, Voltairean atheists, crossroads orators, cut-throats from the streets and prisons, starvelings from the tribune, clubs and scaffolds; he is great in that he curbed an anarchical mob; he is great in that he put an end to the familiarities of a shared fate, forcing soldiers who were his equals, and captains who were his superiors or rivals to bend to his will; he was above all great in that he was born of himself alone, able, with no other authority than his genius, to compel thirty six millions subjects to obey him in an age where no illusions surrounded the throne; he is great because he overthrew all the kings who opposed him, because he defeated all the armies however varied in discipline and courage, because he taught his name to savages as well as to civilised peoples, because he surpassed all the conquerors who preceded him, because he filled ten years with such prodigious deeds that we find it hard today to comprehend them.

‘Napoléon’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p245, 1845)

The British Library

The famous delinquent is no longer a subject for triumphs, and the few men who still appreciate noble sentiments can do homage to his glory without fearing it, without repenting of having proclaimed what was fatal regarding that glory, and without being forced to recognise a destroyer of freedom as the father of emancipation: Napoleon has no need for borrowed merit; he was sufficiently endowed at birth.

So now that, severed from his age, his story is ended and his myth is beginning, let us go and watch him die: let us leave Europe; let us follow him beneath the skies of his apotheosis! The tremor of the sea, where his ships furled their sails, will indicate to us the place where he vanished: ‘At the extremity of our hemisphere,’ says Tacitus, ‘one hears the sound of the sun sinking beneath the waves: sonum insuper immergentis audiri.’

Book XXIV: Chapter 9: The island of St Helena – Bonaparte travels the Atlantic

BkXXIV:Chap9:Sec1

Juan da Nova, the Portuguese navigator, was wandering through the waters separating Africa from America. In 1502, on the 21st of May, Saint Helena’s day, she being the mother of the first Christian Emperor, he discovered an island in latitude 16 degrees south, and longitude 6 degrees west; he landed there and named it after the day of its discovery.

Having visited the island over several years, the Portuguese abandoned it: the Dutch established themselves there, and then deserted it for the Cape of Good Hope; the British East India Company seized it; the Dutch took it back briefly in 1673, but the English occupied it once more and stayed there.

When Juan da Nova appeared at St Helena, the interior of the island was only inhabited by forest. Fernando Lopez, a renegade Portuguese, jumped ship onto this oasis, peopling it with cows, goats, chickens, guinea-fowl, and other birds from the four corners of the earth. There boarded successively, as if they were boarding the Ark, the creatures of the whole creation.

Five hundred Whites and five hundred Negroes, as well as Mulattos, Javanese and Chinese, composed the population of the island. Jamestown is the main town and port. Before the English became masters of the Cape of Good Hope, the Company fleets, returning from India, broke their voyage at Jamestown. The sailors laid out their cheap goods at the foot of the cabbage palms: mute and solitary forest turned, year by year, into a noisy populous market.

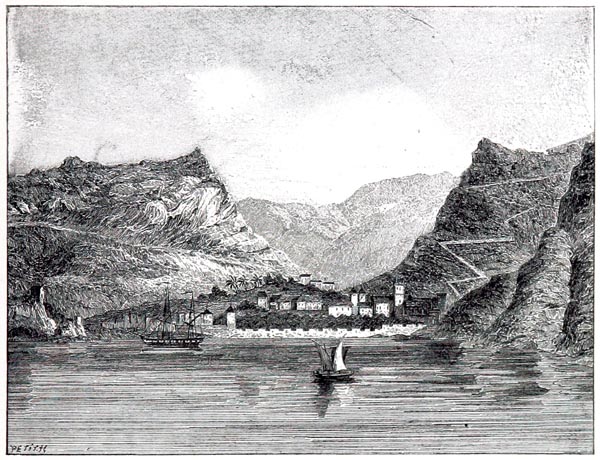

‘Sainte-Hélène. Vue de James-Town’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p963, 1888)

The British Library

The climate of the island is healthy, but rainy: this prison of Neptune’s, which is no more than twenty four miles or so in circumference, draws the Ocean vapours. The equatorial sun at midday oppresses everything that breathes, forcing silence and rest on all except the midges, obliging men and animals to seek the shade. The waves are illuminated at night by what is called sea-light; the light produced by the myriads of insects whose amours, charged by the storms, light the torches of a universal wedding on the surface of the deep. The shadow of the island, dark and solid, rests in the midst of a moving plain of diamonds. The spectacle of the sky is similarly magnificent, according to my learned and celebrated friend Monsieur von Humboldt (Voyage to the Equinoctial Regions). ‘One experiences,’ he says, ‘I do not know what strange feeling, when in approaching the equator, and especially in crossing from one hemisphere to the other, one sees the stars one has known from childhood progressively declining and at last vanishing from the night sky. One knows one is no longer in Europe when one sees the immense constellation of Argo Navis, or the phosphorescent Magellanic Clouds.

We only saw the Southern Cross distinctly,’ he says, ‘on the night of the 4th of July, in 16 degrees of latitude.

I recalled that sublime passage of Dante’s which the most celebrated commentators consider applies to this constellation:

“Io mi volsi a man destra, etc.”

Among the Portuguese and Spaniards, a religious sentiment attaches to this constellation whose form recalls that sign of faith to them, planted by their forebears in the wastes of the New World.’

The poets of France and Lusitania have set elegiac scenes on the shores of Melinde and the neighbouring islands. It is a long way from those fictional sorrows to the real sufferings of Napoleon beneath stars known to Beatrice’s singer, in tropical waters like those of Éléonore and Virginie. Did the great men of Rome, exiled to the isles of Greece, care for the charms of those shores and the divinities of Crete and Naxos? What delighted Da Gama and Camoëns failed to move Bonaparte: lying down at the vessel’s stern, he appeared not to notice that unknown constellations glittered above his head whose rays would have met his gaze for the first time. What did he make of those stars he would never have seen in camp, which had not shone over his Empire? And yet there was no star lacking in his fate: one half of the firmament shone at his birth; the other half was destined for his funeral ceremony.

The sea Napoleon sailed was not that friendly sea that carried him from the havens of Corsica, the sands of Aboukir, the rocky cliffs of Elba, to the shores of Provence; it was that hostile ocean that, having imprisoned him in Germany, France, Portugal and Spain, only opened before his path in order to close behind him. Possibly, while watching the waves urging on his ship, the trade winds blowing him onwards with unceasing breath, he did not reflect on his downfall in the way to which I am inspired: every man experiences life in his own way, and he who yields the world a fine spectacle is less moved and less instructed than the spectator. Pre-occupied with the past, as though he might still rise again, hoping yet among his memories, Bonaparte hardly noticed that he had crossed the line, and he asked not who had traced those orbits within which the planets are forced to confine their eternal progress.

On the 15th of August, the wandering colony celebrated St Napoleon’s Day on board the vessel conducting Napoleon to his last resting-place. On the 15th of October, the Northumberland was abreast of St Helena. The passenger went on deck; he could barely make out an imperceptible black speck in the bluish immensity; he took a telescope; he observed that particle of earth as he would once have surveyed a fortress in the midst of a lake. He could see the little town of St James set among sheer cliffs; there was not a wrinkle in that sterile facade that was without a gun clinging there: they seemed to wish to receive the captive in a manner suited to his genius.

On the 16th of October 1815, Bonaparte landed on the rock, his mausoleum, just as on the 12th of October 1492, Christopher Columbus landed in the New World, his monument: ‘There,’ says Walter Scott, ‘at the gateway to the Indian Ocean, Bonaparte was deprived of the means of making a second avatar or incarnation on earth.’

Book XXIV: Chapter 10: Napoleon lands on St Helena – His establishment at Longwood – Precautions – Life at Longwood – Visits.

BkXXIV:Chap10:Sec1

Before being moved to the residence of Longwood, Bonaparte occupied a villa, The Briars, near Balcomb’s Cottage. On the 9th of December, Longwood, hurriedly enlarged by carpenters from the English flotilla, received its guest. The house situated on a plateau in the hills, consisted of a drawing room, a dining room, a library, a study, and a bedroom. It was not much: those who had occupied the tower of the Temple and the keep at Vincennes were still worse lodged; true, their hosts were considerate enough as to abridge their stay. General Gourgaud, Monsieur and Madame Montholon with their children, Monsieur Las Cases and his son, camped out provisionally in tents; Monsieur and Madame Bertrand installed themselves at Hut’s Gate, a cottage at the edge of the Longwood grounds.

For his exercise-yard, Napoleon had a stretch of sand twelve miles long; sentries surround the tract, and look-outs were sited on the tallest summits. The lion could extend his walks further, but he then had to agree to be guarded by an English watch-dog. Two camps defended this enclosure for the excommunicated: at night the circle of sentries contracted around Longwood. After nine, Napoleon was constrained from going out; the patrols made their rounds; cavalry on mounted sentry duty, and infantry posted here and there, kept watch over the creeks and ravines which sloped towards the sea. Two armed brigs cruised about, one to leeward, the other to windward of the island. What precautions to guard one man in the midst of an ocean! After sunset, no vessels could put out to sea; the fishing-boats were counted, and at night they were moored in harbour under the eye of a naval lieutenant. The sovereign leader who had summoned the world to his stirrup was called upon to present himself before a junior officer twice a day. Bonaparte would not acquiesce to that order; when he chanced to escape the notice of the officer on duty, that officer dare not say if and when he had seen that man whose absence it was more difficult to prove than to prove the presence of the universe.

Sir George Cockburn, the author of these harsh regulations, was replaced by Sir Hudson Lowe. The bickering then began that all the Memoirs speak of. If we are to believe these Memoirs, the new Governor was related to the species of giant St Helena spiders, and was the reptile of those woods where snakes are unknown. England lacked nobility, Napoleon dignity. To put an end to the demands of etiquette, Bonaparte sometimes seemed determined to conceal himself beneath a pseudonym, like a monarch when in a foreign country; he had the touching idea of taking the name of one of his aides-de-camp killed at the Battle of Arcola. France, Austria and Russia appointed Commissioners for the St Helena residence; the prisoner was accustomed to receiving the ambassadors of the two latter powers; the Legitimacy, which had not recognised Napoleon as Emperor, would have acted more nobly by not recognising Napoleon as a prisoner.

A large wooden house, constructed in London, was sent to St Helena; but Napoleon did not feel well enough to live in it yet. His life at Longwood was arranged thus: he rose at no set time; Monsieur Marchand, his valet, read to him as he lay in bed; when he rose each morning, he dictated to Generals Montholon and Gourgaud, and the son of Monsieur de Las Cases. He breakfasted at ten, went for a ride or a drive until three, returned indoors at six and went to bed at eleven. He affected the costume in which he is depicted in Isabey’s portrait: in the morning he wrapped himself in a caftan and wound a Madras kerchief round his head.

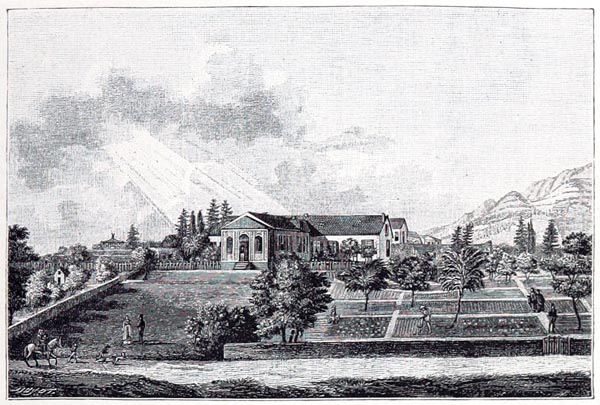

‘Vue de Longwood. Dessinée d'Après Nature (Sainte-Hélène, 1820)’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p965, 1888)

The British Library

St Helena lies between the two Poles. Navigators journeying from one to the other welcome this first station where the land soothes eyes wearied by the sight of the Ocean and offers fruit and the coolness of fresh water to mouths chafed by the salt. Bonaparte’s presence changed this promised isle to a plague-stricken rock: foreign ships no longer touched there; as soon as they were sighted fifty miles off, a cruiser went to challenge them, and ordered them to stand away; they were not allowed to anchor, except in stormy weather, unless they were Royal Navy vessels.

Some of the English travellers who had recently admired, or were off to view, the marvels of the Ganges visited another marvel on their way: India, accustomed to conquerors, had one chained at her gate.

Napoleon reluctantly allowed these visits. He agreed to see Lord Amherst, on the latter’s return from his Chinese embassy. Admiral Sir Pulteney Malcolm he liked: ‘Does your Government,’ he asked one day, ‘intend to keep me on this rock until I die?’ The Admiral replied that he feared so. ‘Then my death will soon occur.’ – I hope not, Monsieur; you must live long enough to record your great deeds; they are so numerous that the task will guarantee you a long life.’

Napoleon was not offended by that simple title of Monsieur; he revealed himself at that instant in his true greatness. Fortunately for him, he never wrote his own life; he would have diminished its dimensions: men of that nature should leave their memoirs to be recounted by that unknown voice, which belongs to no one and which issues from nations and centuries. Only we, the commonplace ones, are allowed to speak of ourselves, since otherwise no one would speak of us.

Captain Basil Hall presented himself at Longwood: Bonaparte remembered having met the Captain’s father at Brienne: ‘Your father,’ he said, ‘was the first Englishman I ever met; that is why I have remembered it all my life.’ He spoke with the Captain about the recent discovery of Loo-Choo: ‘The inhabitants have no weapons,’ said the Captain. – ‘No weapons! Bonaparte exclaimed – Neither cannon nor rifles – Spears surely, bows and arrows? – Nothing like that. – No daggers? – No daggers. – Well how do they fight? – They know nothing of what is happening in the world; they know nothing of the existence of France and England; they have never heard of Your Majesty.’ Bonaparte smiled in a manner that amazed the Captain: the more serious the face, the more beautiful the smile.

The various voyagers remarked that there was not a trace of colour in Bonaparte’s features: his head resembled a marble bust whose whiteness had yellowed slightly with time. No furrows on his brow, no hollows in his cheeks; his soul seemed at peace. That visible serenity gave the impression that the flame of his genius had died. He spoke slowly; his expression was pleasant and almost tender; sometimes he revealed a penetrating glance, but the state swiftly passed; his eyes misted over and became saddened.

Ah! Other voyagers known to Napoleon had once appeared on that shore.

After the explosion of the ‘infernal machine’, a senatus consulte of 5th of January 1801 pronounced judgement, a simple matter for the police, the exile overseas of three hundred Republicans: embarked on the frigate La Chiffone and the corvette La Flèche, they were taken to the Seychelles and shortly afterwards scattered through the Comoros archipelago, between Africa and Madagascar: there almost all of them died. Two of the deportees, Lefranc and Saunois, who managed to escape on an American vessel, landed on St Helena in 1803: it was there twelve years later that Providence was to imprison their great oppressor.

The all-too-famous General Rossignol, their companion in misfortune, a quarter of an hour before his last sigh, exclaimed: ‘I die conquered by the most terrible pain; but I would die content if I knew that my country’s despot was to endure the same suffering.’ So, even in that other hemisphere, freedom’s curses awaited him who had betrayed her.

Book XXIV: Chapter 11: Manzoni – Bonaparte’s illness – Ossian – Napoleon’s daydreams by the sea – Projects of escape – Bonaparte’s last occupation – He lies down and does not rise again – He dictates his will – Napoleon’s religious sentiments – Vignali the Chaplain – Napoleon argues with Antomarchi, his doctor – He receives the last sacraments – He dies

BkXXIV:Chap11:Sec1

Italy, woken from its long sleep by Napoleon, turned its eyes towards its illustrious son who wished to reinstate its former glory and with whom it had fallen once more under the yoke. The sons of the Muses, the noblest and most grateful of men, when they are not the basest and most ungrateful, gazed at St Helena. The latest poet of Virgil’s homeland sang of the latest warrior of Caesar’s:

‘Tutto ei provo, la Gloria

Maggior dopo il periglio,

La fuga e la vittoria,

La reggia e il triste esiglio:

Due volte nella polvere,

Due volte sugli altar.

Ei si nomò; due secoli,

L’un contro l’altro armato,

Sommessi a lui si volsero,

Come aspettando il fato:

Ei fè silenzio ed arbitro

S’assise in mezzo a lor.’

‘He experienced all,’ says Manzoni, ‘his glory greater after peril, flight and victory, royalty and sad exile, twice in the dust, twice at the altar.

He spoke his name: two centuries, armed against each other, submitted to him, awaiting their fate: he commanded silence and sat in judgement between them.’

Bonaparte was approaching his end; plagued by an internal pain, poisoned by sorrow, he had endured that pain in the midst of prosperity: it was the only inheritance he had received from his father; the rest came to him out of God’s munificence.

He had already known six years of exile; he needed less time to conquer Europe. He remained almost perpetually indoors, and read Ossian in Cesarotti’s Italian translation. Everything saddened him, beneath a sky under which life seemed short, the sun remaining for three days less in that hemisphere than in ours. When Bonaparte went out, he passed along stony paths bordered by aloes and scented broom. He walked among sparsely-flowering gum-trees bent in one direction by the prevailing winds, or else concealed himself in thick clouds that hugged the ground. He was seen sitting at the foot of Diana’s Peak, Flagstaff, or Ladder Hill, contemplating the sea through the gaps in the mountains. Before him stretched an Ocean which on one side washes the African coast, on the other the shores of America, and which flows like a river without banks to lose itself in the southern seas. No civilised land nearer than the Cape of Storms. Who can say what thoughts went through the mind of that Prometheus, torn apart by death while still living, when, pressing his hand to his aching breast, he looked out over the waves! Christ was carried to a mountain summit from which He viewed the kingdoms of the world; but in Christ’s case the tempter of mankind was told: ‘Thou shalt not tempt the Lord thy God.’

Bonaparte, forgetting a thought of his own which I have quoted (‘Not having given myself life I will not deprive myself of it.’), spoke of killing himself; he also forgot his order of the day regarding the suicide of one of his soldiers. He had sufficient confidence in the devotion of his companions in captivity to believe that they would consent to suffocating with him in the fumes from a brazier: a grand illusion. Such are the intoxications born of long supremacy; but regarding Napoleon’s fits of impatience we must consider the degree of suffering he had attained. Monsieur de Las Cases having written to Lucien on a piece of white silk, in contravention of the rules, received the order to leave St Helena: his absence increased the void around the exile.

On the 18th of May 1817, Lord Holland, in the House of Lords, introduced a motion on the subject of the complaints transmitted to England by General Montholon: ‘Posterity will not ask’ he said, ‘whether Napoleon was justly punished for his crimes, but whether England showed the generosity befitting a great nation.’ Lord Bathurst opposed the motion.

Cardinal Fesch sent two priests to his nephew. Princess Borghèse begged the favour of being allowed to join her brother: ‘No,’ said Napoleon, ‘I do not wish her to witness my humiliation, and the insults to which I am subjected.’ That beloved sister of his, germana Jovis (Jove’s sister) did not cross the seas; she died in a region where Napoleon had left his fame behind him.

Projects were conceived for his abduction: a Colonel Latapie, at the head of a band of American adventurers, contemplated a landing on St Helena. Johnston, a bold smuggler, thought of carrying Bonaparte off in a submarine. Some young noblemen entered into these plans; they schemed at breaking the oppressor’s bonds; while they would have left some liberator of the human race to die in chains without a thought. Bonaparte hoped his deliverance might be achieved on the back of the political movements in Europe. If he had lived until 1830, perhaps he would have returned to us; but what would he have done amongst us? He would have seemed obsolete and outdated in the midst of new ideas. Once his tyranny seemed like liberty to our slavery; now his greatness would look like despotism to our pettiness. In the present age everything is decrepit in a day; whoever lives too long dies while they are still alive. Advancing through life, we leave behind three or four representations of ourselves, differing one from another; we see them again through the mists of the past like portraits painted at different ages.

Bonaparte stripped of his power occupied himself exactly like a child: he amused himself by making an ornamental pond in his garden; he added a few fish: the cement used in making the pond contained copper, and the fish died. Bonaparte said: ‘Everything that attaches itself to me is doomed.’

BkXXIV:Chap11:Sec2

Towards the end of February 1821, Napoleon was obliged to take to his bed and did not rise again. ‘How low I have fallen!’ he murmured, ‘I have overturned a world and cannot lift an eyelid!’ He had no faith in medicine and objected to a consultation between Antomarchi and the Jamestown doctors. However he allowed Dr Arnott to approach his death-bed. From the 16th to the 24th of April he dictated his will; on the 28th, he ordered his heart to be sent to Marie-Louise; he forbade any English surgeon to lay a hand on him after his death. Convinced that he was succumbing to the disease which afflicted his father, he asked for the autopsy report to be sent to the Duke of Reichstadt: the paternal precaution was of no avail; Napoleon II has joined Napoleon I.

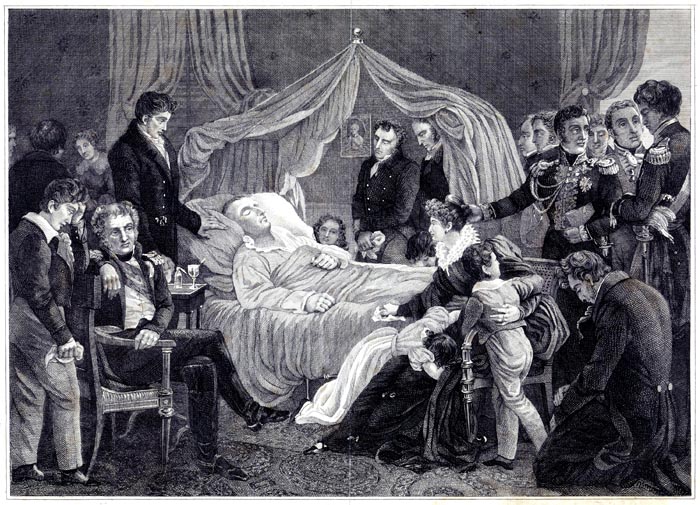

‘The Deathbed of Napolean’

Abraham Vinkeles, C. L. Schleijer, 1840

The Rijksmuseum

At this final hour, the religious feeling, with which Bonaparte had always been imbued, awoke. Thibaudeau in his Memoirs of the Consulate, tells us, with reference to the restoration of religious worship, that the First Consul said to him: ‘Last Sunday, in the midst of Nature’s hush, I was walking in those gardens (at Malmaison); the sound of the bells from Rueil happened to strike my ear and revived all the impressions of my youth; I was moved, so strong is the force of early habit, and I said to myself: “If it is so for me, what effect must like memories not produce on simple and credulous people?” Let your philosophers reply to that!’ ..............................................and raising his hands to heaven: ‘Who is He, who made it all?’

In 1797, by his Proclamation of Macerata, Bonaparte permitted the French priests who had taken refuge in the Papal States to remain there, forbade them to be molested, ordered the monasteries to support them, and allotted them a stipend.

His vagaries in Egypt, his fits of anger against the Church, which he restored, show that a spiritual instinct dominated in the very midst of his errors, since his lapses and his rages are not philosophical at root and bear the imprint of a religious temperament.

When Bonaparte was giving Vignali details of the tapers with which he wished his remains to be surrounded in the chapel, thought that he perceived his instructions were displeasing to Antomarchi, and he explained his conduct to the doctor, saying: ‘You are above these weaknesses: but what would you, I am neither a doctor nor a philosopher; I believe in God; I am of my father’s religion. Not all who wish can be atheists...How can you not believe in God? After all, everything proclaims his existence, and the greatest geniuses have believed so. You are a doctor. such people deal in nothing but material things: they never believe in anything.’

You Rationalists abandon your admiration for Napoleon; you have nothing in common with that poor man: did he imagine that a comet had come for him, as one once carried off Caesar? Moreover, he believed in God; he was of his father’s religion; he was no philosopher; he was no atheist; he had not, as you have, joined battle with the Eternal One, though he had vanquished a good number of kings; he found that everything proclaimed the existence of the Supreme Being; he declared that the greatest geniuses had believed in His existence, and he wished to believe as his forefathers did. Lastly, terrible to relate, this foremost man of modern times, this man for all the centuries, was a Christian of the nineteenth century! His will begins with this statement:

‘I DIE IN THE APOSTOLIC AND ROMAN RELIGION, IN THE BOSOM OF WHICH I WAS BORN MORE THAN FIFTY YEARS AGO.’

In the thirds paragraph of Louis XVI’s will, we read:

‘I DIE IN THE UNION OF OUR HOLY MOTHER THE CATHOLIC, APOSTOLIC, AND ROMAN CHURCH.’

The Revolution taught us many lessons but is any one of them comparable with this? Napoleon and Louis XVI making the same profession of faith! Do you wish to know the worth of the Cross? Then search the whole world for what best suits virtue in misfortune or the man of genius on his death bed.

On the 3rd of May, Napoleon was given Extreme Unction and received the Blessed Viaticum. The silence of the bedroom was punctuated only by the dying man’s irregular breathing and the steady tick of a pendulum clock: the shadow, before fading on the dial, did a few more rounds; the sun which cast it found difficulty in setting. On the 4th, the storm of Cromwell’s death agony rose: nearly all the trees at Longwood were uprooted. Finally, on the 5th, at eleven minutes to six in the evening, in the midst of wind, rain and the thunder of the waves, Bonaparte rendered up to God the mightiest breath of life that ever animated human clay. The last words on the conqueror’s lips were: ‘Head.army, or Head of the Army.’ His thoughts still wandered amongst battles. When he closed his eyes forever, his sword, which died with him, lay at his left side, and a crucifix rested on his breast: the symbol of peace applied to Napoleon’s heart calmed the throbbing of that heart, as a ray of sunlight quiets the flood.

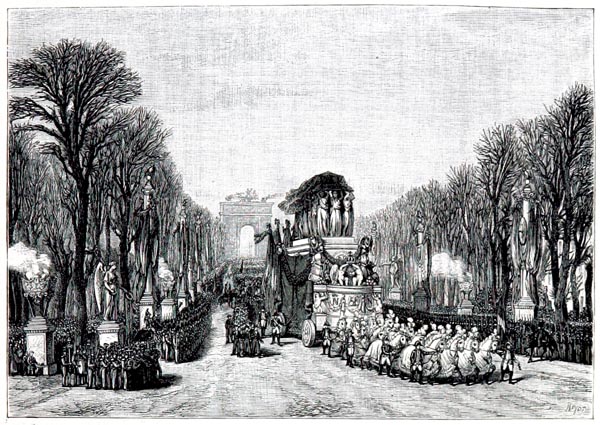

Book XXIV: Chapter 12: Funeral rites

BkXXIV:Chap12:Sec1

Bonaparte had first asked to be buried in the Cathedral at Ajaccio, then, by a codicil to his will dated the 16th of April 1821, he bequeathed his bones to France: Heaven had served him better; his real mausoleum is the rock on which he expired: turn again to my account of the Duc d’Enghien’s death. Napoleon, foreseeing the opposition of the British Government to his last wishes, eventually chose a burial place on St Helena.

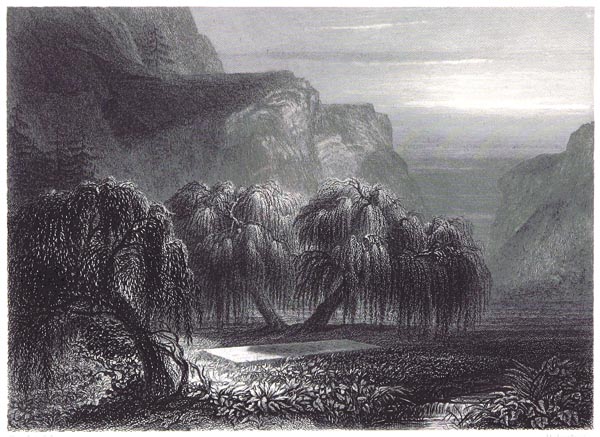

In the narrow valley known as Sane or Geranium Valley, and now the Valley of the Tomb, there is a spring; Napoleon’s Chinese servants, as faithful as Camoën’s Javanese, used to fill their pitchers there: two weeping willows hung over the fount; green grass studded with champa grows all around, ‘Champa,’ say the Sanskrit poems, ‘for all its splendour and perfume, is not a sought after flower, because it grows on graves.’ In the declivities of the deforested slopes, there is a sparse growth of bitter lemon trees, nut-bearing coconut palms, larches and a catchfly from which the sap is gathered that sticks to the beards of goats.

Napoleon liked the willows by the spring; he asked peace of the Sane Valley, as the exiled Dante sought peace at the monastery of Corvo. In gratitude for the transient repose which he enjoyed there in the last days of his life, he chose this valley to shelter his eternal rest. Speaking of its spring he said: ‘If God allowed me to recover, I would raise a monument at the place where it rises.’ That monument was his tomb. In Plutarch’s day, at a spot on the banks of the Strymon dedicated to the nymphs, one could still see a stone seat on which Alexander sat.

‘Sainte-Hélène’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p247, 1845)

The British Library

Napoleon, booted and spurred, dressed in the uniform of a Colonel of the Guard, decorated with the Legion of Honour, was laid out on his little iron bedstead; on the face which had never shown surprise, the soul, in departing, had left a sublime stupor. The planers and joiners soldered and nailed Bonaparte into a fourfold coffin of mahogany, lead, mahogany once more, and tin; it was as if they feared he could never be sufficiently contained. The cloak which the former conqueror had worn at the vast funeral rite of Marengo served as a pall for the coffin.