François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XVI: The Execution of the Duc d’Enghien 1804

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XVI: Chapter 1: The year 1804 – The Valais Republic – A visit to the Tuileries Palace – The Hôtel de Montmorin – I hear of the death of the Duc d’Enghien – I hand in my resignation

- Book XVI: Chapter 2: The Death of the Duc d’Enghien

- Book XVI: Chapter 3: The Year 1804

- Book XVI: Chapter 4: General Hulin

- Book XVI: Chapter 5: The Duc de Rovigo

- Book XVI: Chapter 6: Monsieur de Talleyrand

- Book XVI: Chapter 7: Their various roles

- Book XVI: Chapter 8: Bonaparte: his sophistry and remorse

- Book XVI: Chapter 9: What should be concluded from all this – Enmities created by the death of the Duc d’Enghien

- Book XVI: Chapter 10: An article in Le Mercure – The change in Bonaparte’s existence

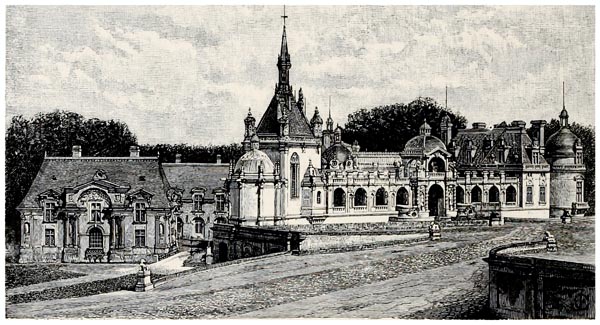

- Book XVI: Chapter 11: Chantilly Deserted

Book XVI: Chapter 1: The year 1804 – The Valais Republic – A visit to the Tuileries Palace – The Hôtel de Montmorin – I hear of the death of the Duc d’Enghien – I hand in my resignation

Paris, 1838 (Revised the 22nd February 1845)

BkXVI:Chap1:Sec1

It not being my intention to remain in Paris, I stayed at the Hôtel de France, in the Rue de Beaune, where Madame de Chateaubriand was to join me, to travel with me to the Valais. My former circle, already half-scattered, had broken the ties which bound it.

Bonaparte marched on towards Empire; his genius rose to meet escalating events: he could, like gunpowder exploding, carry a world before him; already vast, and yet not considering himself to have attained his peak, his powers tormented him; he was feeling his way, he appeared to be searching for his path: when I arrived in Paris, it lay via Pichegru and Moreau: with a mean motivation he had consented to accept them as rivals: Moreau, Pichegru and Georges Cadoudal, who was greatly their superior, were arrested.

This mundane series of intrigues that one meets in all the affairs of life, corresponded to nothing in my nature, and I was happy to flee into the mountains.

The town Council of Sion wrote to me. The naivety of this dispatch makes it for me a document to treasure; I entered politics through religion: Le Génie du Christianisme opened doors for me.

REPUBLIC OF VALAIS

Sion, the 20th of February 1804.

THE COUNCIL OF THE TOWN OF SION,

To Monsieur Chateaubriand,

Secretary to the Legation of the French Republic in Rome.

‘Sir,

By an official letter, from our Grand Bailiff, we have been apprised of your appointment to the position of Minister of France to our Republic. We hasten to testify to you the enormous pleasure this choice has given us. We see in this nomination a precious token of the First Consul’s benevolence towards our Republic, and we congratulate ourselves on the honour of welcoming you within our walls: we derive from it the happiest auguries of advantage to our country and our town. To bear witness to you of our feelings, we have decided to have temporary accommodation prepared for you, worthy to receive you, equipped with furniture and effects suitable for your use, inasmuch as the location and circumstances permit, expecting that you will be making your own arrangements at your own convenience.

Please accept this offer, Sir, as a proof of our sincere intent to honour the French Government in the person of its employee, the choice of whom must give particular pleasure to a religious nation. We beg you to give us sufficient notice of your arrival in our town.

Accept, Sir, assurances of our respectful consideration.

The President of the Council of the town of Sion.

DE RIEDMATTEN.

For the Town Council:

The Secretary of the Council,

DE TORRENTE.’

Two days before the 21st of March, I dressed formally to go and take leave of Bonaparte at the Tuileries; I had not seen him since the time when he had spoken to me at Lucien’s. The gallery in which he was receiving visits was full; he was accompanied by Murat and a principal aide-de-camp; he strode along almost without stopping. As he reached me, I was struck by the alteration in his face: his cheeks were hollow and livid, his eyes burning, his complexion pale and blotchy; his expression sombre and fierce. The attraction he had previously possessed for me, ceased; instead of standing in his path, I made a movement as if to avoid him. He threw me a glance as if he was trying to recognise me, took a few paces towards me, then turned and walked away. Had I seemed to him like a warning? His aide-de-camp noticed me; when the crowd hid me, this aide-de-camp tried to catch sight of me between the people standing in front of me, and redirected the Consul towards me. This game continued for about a quarter of an hour, I forever retreating, Napoleon forever following me unawares. I have never known what motivated the aide-de-camp. Did he take me for a suspicious person whom he did not know? If he knew who I was, did he want to press Bonaparte into speaking to me? Whatever may have been the reason, Napoleon went on into another room. Satisfied at having done my duty by presenting myself at the Tuileries, I withdrew. Given the joy I always felt at leaving palaces, it is clear I was never made for entering them.

‘Les Tuileries’

Résidences Royales et Impériales de France, Histoire et Monuments - Jean Jacques Bourassé (p108, 1864)

The British Library

Returning to the Hôtel de France, I told my friends: ‘Something strange must be happening that we know nothing of, since Bonaparte can not have changed as much as this without being ill.’ Monsieur Bourrienne knew of my singular prescience, he has only confused the dates: here is his comment: ‘On returning from seeing the First Consul, Monsieur de Chateaubriand told his friends that he had noticed a great change in the First Consul, and something sinister in his glance.’

Yes, I noticed it: a superior intelligence does not produce evil without pain, because it is not its natural fruit, and it ought not to bear it.

Two days later, on the 21st March, I rose early, for the sake of a memory sad and dear to me. Monsieur de Montmorin had built himself a house at the corner of the Rue Plumet, on the new Boulevard des Invalides. In the garden of this house, which was sold during the Revolution, Madame de Beaumont, when little more than a child, had planted a cypress tree, which she had occasionally taken pleasure in showing me as we passed: it was to this cypress, whose origin and history I alone knew, that I was going, to say my farewells. It still exists, but is languishing and scarcely rises as far as the window beneath which her vanished hand used to tend it. I can distinguish that poor tree from among three or four others of the same species; it seems to know me and rejoice when I approach; melancholy breezes bend its yellowed head somewhat towards me, and it murmurs at the window of the deserted room: a mysterious understanding between us, that will cease when one or the other of us falls.

My pious tribute made, I descended the Boulevard, crossed the Esplanade des Invalides, the Pont Louis XVI and the Tuileries Gardens, which I left by the gate, near the Pavilion Marsan, which now leads into the Rue de Rivoli. There, between eleven and twelve o’clock, I heard a man and a woman shouting out official news; passers-by were stopping, suddenly petrified at the words: ‘Verdict of the special military commission convened at Vincennes, sentencing to death THE MAN NAMED LOUIS-ANTOINE-HENRI DE BOURBON, BORN THE 2ND AUGUST 1772 AT CHANTILLY.’

This cry in the street struck me like a bolt of lightning; it changed my life, as it changed that of Napoleon. I went home; I said to Madame de Chateaubriand: ‘The Duc d’Enghien has just been shot.’ I sat at the table, and began writing my letter of resignation. Madame de Chateaubriand did not oppose my decision, and with great courage watched me write it. She was not deceived as to the risk: Generals Moreau and Cadoudal were being tried; the lion had tasted blood, this was not the moment to annoy him.

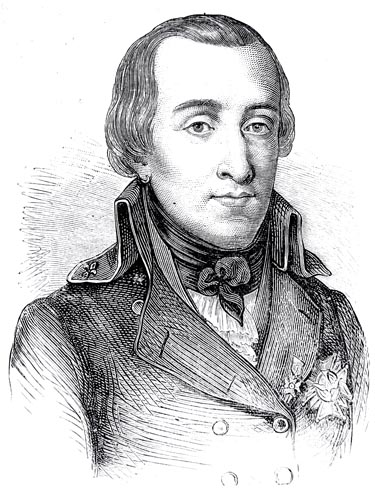

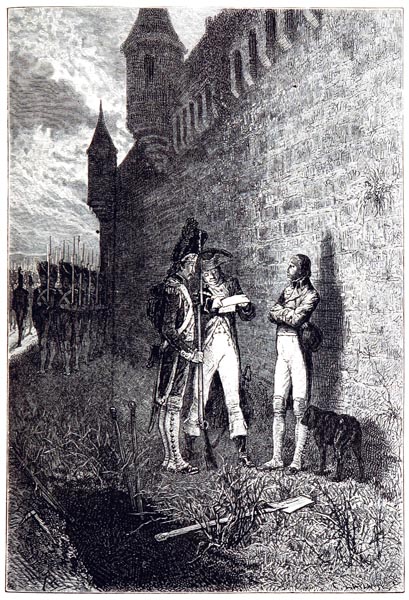

‘The Duc d’Enghien, Engraved by E.Thomas from the Design by H. Rousseau’

Album du Centenaire, Grands Hommes et Grands Faits de la Révolution Française (1789 - 1804) - Augustin Challamel, Desire Lacroix (1889)

Wikimedia Commons

Monsieur Clausel de Coussergues arrived at this juncture; he too had heard the verdict shouted out. He found me pen in hand; my letter, some angry phrases of which he made me omit, out of consideration for Madame de Chateaubriand, was dispatched; it was addressed to the Foreign Minister. The wording mattered little: the expression of my opinion, and my crime lay in the fact of my resignation: Bonaparte would make no mistake there. Madame Bacciochi shrieked loudly when she learned of what she called my defection; she sent for me and reproached me in a vigorous manner. Monsieur de Fontanes, was almost mad with fear initially, and then acted with fearless friendship; he regarded me as already as good as executed, along with everyone attached to me. For several days, my friends were afraid of my being taken away by the police; they appeared at my house from time to time, always trembling as they reached the porter’s lodge. Monsieur Pasquier came to embrace me the day after my resignation, saying how happy a thing it was to have such a friend. He stayed quite some considerable time indulging in an honourable and impartial analysis of position and power.

Nevertheless, these expressions of sympathy, which swept us along in their praise of a generous action, ceased. I had accepted, because of religion, an appointment outside France, an appointment conferred on me by a powerful genius, who had conquered anarchy, a leader who had emerged on the basis of popular principle, the consul of a republic, and not a king continuing the line of a usurped monarchy; thus, I was isolated in my opinions, because I was strictly logical in my actions; I resigned when the conditions to which I could subscribe altered; yet, immediately the hero turned murderer, others hastened into his ante-chambers. Six months after the 21st March, one might have thought there had only been one opinion in the upper echelons of society, except for a few nasty jibes allowed behind closed doors. Those who had fallen claimed to have been forced out, and people said that only those of significant lineage or great importance had been forced out, and that each, as proof of their importance or their lineage, had ensured they would be forced out by dint of asking for it to happen.

Those, who had applauded my action most, distanced themselves; my presence was a reproach to them: prudent men find those who yield to a point of honour imprudent. There are times when nobility of soul is a positive handicap; no one understands it; it is treated as proof of limited intellect, a result of prejudice, a whim, a fault which prevents you from judging correctly; an imbecility that is worthy perhaps, they might say, but still a stupid helotism. What intelligence is to be found in seeing nothing, in living divorced from the march of the century, the swirl of ideas, the transformation of our way of life, the progress of society? Is it not a deplorable mistake to attach an importance to events which they do not possess? Barricaded within your narrow principles, lacking in wit as well as judgement, you are like a man lodged in the rear of a building, looking out on only a tiny courtyard, unaware of what is passing in the street, and what the noises are outside. See how a little independence cuts you down to size, object of pity to mediocrities that you are: as for great spirits with their affected pride and sublime eyes, oculos sublimes, their merciful disdain forgives you because they know that you cannot understand. So I retreated humbly into my literary career; a poor Pindar destined in the first Olympian to sing of the excellence of water, leaving wine to happier men.

Friendship heartily requited Monsieur de Fontanes; Madame Bacciochi kindly placed herself between her brother’s anger and my decision; Monsieur de Talleyrand, through indifference or calculation, kept my letter of resignation for several days before mentioning it: when he told Bonaparte of it, the latter had already spent time in reflection. Receiving from me the only direct token of blame, from an honest man who did not hesitate to defy him, he only pronounced these two words: ‘That’s fine.’ Later he said to his sister: ‘You were quite fearful for your friend.’ Long afterwards, in conversation with Monsieur de Fontanes, he confessed to him that my resignation was one of the things that most impressed him. Monsieur de Talleyrand had an official letter sent to me, in which he reproached me graciously for depriving his department of my talents and services. I returned the cost of my installation, and everything was over it would seem. But by daring to turn my back on Bonaparte, I had set myself on a par with him, and he was opposed to me in all perfidy, as I was opposed to him in all loyalty. Until he fell, he held a sword suspended above my head; he turned to me sometimes through a natural inclination, and tried to engulf me in his fatal prosperity; sometimes I inclined towards him through the admiration with which he inspired me, through the idea that I was assisting in a social transformation, not merely a change of dynasty: but antipathetic despite our many empathies, our two natures reasserted themselves, and if he would willingly have had me shot, I would have felt no great compunction in killing him.

Death makes or unmakes a great man; it halts him on the step from which he was about to descend, or at the level from which he was about to ascend: it represents a destiny accomplished or foregone; in the first case, one is concerned with what has happened; in the second with conjectures about what might have happened.

If I had been carrying out an exercise with a view to my long term ambitions, I would have been in error. Charles X only learnt in Prague of what I had done in 1804: he had reclaimed the monarchy. ‘Chateaubriand,’ he asked me in the Castle of Hradschin, ‘did you serve Bonaparte? – Yes, Sire – Did you resign on the death of Monsieur le Duc d’Enghien? – Yes, Sire.’ Misfortune instructs or erases the memory. I have told you how, once, in London, having taken refuge with Monsieur de Fontanes in a drive-way during a shower, Monsieur le Duc de Bourbon happened to share the same shelter: in France, his gallant father and himself, who thanked so politely whoever wrote the funeral oration for Monsieur le Duc d’Enghien, gave me not a thought: they also doubtless were ignorant of my action: it is true that I had never spoken of it to them.

Book XVI: Chapter 2: The Death of the Duc d’Enghien

Chantilly, November 1837

BkXVI:Chap2:Sec1

Like a migrating bird, restlessness seized me during the month of October which would have forced a change of climate on me if I had only had the use of wings, and sufficient time to spare: the clouds which sped across the sky made me envy their flight. In order to evade this instinct I rushed off to Chantilly. I wandered the lawns where old guardsmen shuffled along at the edge of the woods. A flight of crows scudding in front of me, among the broom, copses and clearings, led me to the lakes of Commelle. Death had already breathed on the friends who once accompanied me to the White Queen’s Castle: these secluded sites were no more than a sad horizon, opening, for an instant, into my past. In the days of René, I would have discovered life’s mysteries in the Thève stream: its course steals among horsetails and moss; reeds veil it; it dies away among the pools that nourish its birth, endlessly vanishing, endlessly renewing: those waters charmed me when I bore within me a wilderness with its phantoms, who smiled on me despite their melancholy, and whom I adorned with flowers.

Returning beside the barely visible hedgerows, rain surprised me; I took refuge under a beech tree: its last leaves were falling like my days; its crown like my hair was thinning; it was marked on its trunk with a red circle, for felling, like me. Back at my inn, with an armful of autumn plants, and in a mood hardly disposed for joy, I will recount for you the death of Monsieur le Duc d’Enghien, in sight of the ruins of Chantilly.

That death, at first, froze all hearts with terror; people dreaded the return of Robespierre’s reign. Paris thought it saw the return of one of those days one sees only once in a lifetime, the day of Louis XVI’s execution. Bonaparte’s servants, friends and relatives were dismayed. Abroad, if popular feeling was swiftly stifled by diplomatic language, the event none the less touched the crowd’s heart. Among the family of Bourbon exiles the coup penetrated deeply: Louis XVIII returned his Order of the Golden Fleece to the King of Spain, which Bonaparte happened to have been decorated with; its despatch was accompanied by this letter, which does honour to the royal spirit:

‘Sir and dear cousin, there can be nothing in common between myself and the great criminal whom audacity and fate have placed on a throne which he has had the barbarity to stain with the pure blood of a Bourbon, the Duc d’Enghien. Religion may oblige me to pardon an assassin; but the tyrant over my people must be my enemy forever. Providence, for reasons which are inexplicable, may condemn me to end my days in exile; but neither my contemporaries, nor posterity, will be able to say that, in times of adversity, I showed myself unworthy to occupy, until my last breath, the throne of my ancestors.’

‘Le Duc d’Enghien en 1788’

Les Arts dans la Maison de Condé - Gustave Macon (p110, 1903)

Internet Archive Book Images

One must not forget another name which was associated with that of the Duc d’Enghien: Gustave-Adolphe, since dethroned and banished, was the only king then reigning who dared to raise his voice to protect the young French prince. He ordered an aide-de-camp to be sent from Carlsruhe with a letter to Bonaparte; the letter arrived too late: the last of the Condé no longer existed. Gustave-Adolphe returned his Order of the Black Eagle to the King of Prussia, as Louis XVIII had returned his Golden Fleece to the King of Spain. Gustave declared to the heir of Frederick the Great that in accord with the laws of chivalry he could not consent to be the brother-in-arms of the murderer of the Duc d’Enghien. (Bonaparte had received the Black Eagle.) How much bitter derision there was expressed by those nigh on foolish tokens of chivalry, suppressed everywhere except in the heart of an unfortunate king on behalf of a murdered friend; a noble sympathy towards misfortune, one which lived concealed and not understood, in an unknowing world of men!

Alas! We had endured too many varying despotisms, and our characters, crushed beneath a series of ills and oppressions, no longer had sufficient energy to allow grief to wear mourning for the death of young Condé for long: little by little the tears dried; fear spilled over in the form of congratulations on the danger which the First Consul had just escaped; it wept with gratitude at having been saved by so saintly a sacrifice. Nero, at Seneca’s dictation, wrote an apologetic letter to the Senate regarding Agrippina’s murder; the senators, carried away, heaped blessings on the magnanimous son who had not feared to pluck out his own heart by so salutary an act of matricide! Society quickly returned to its pleasures; it was afraid of its own mourning: after the Terror, the victims, who had been spared, danced; forced themselves to appear happy, and fearful lest they be suspected of the crime of remembering, displayed the same cheerfulness with which they went to the scaffold.

The Duc d’Enghien was not arrested on the spur of the moment, without thought; Bonaparte had taken account of the various Bourbons in Europe. In a meeting attended by Messieurs de Talleyrand and Fouché, it was noted that the Duc d’Angoulême was in Warsaw with Louis XVIII; the Comte d’Artois and the Duc de Berry were in London, with the Princes de Condé and de Bourbon. The youngest of the Condés was at Ettenheim, in the Duchy of Baden. It appears that Taylor and Drake, English agents, were intriguing on his behalf. The Duc de Bourbon warned his son, on the 16th of June 1803, of the possibility of arrest, in a note to him addressed from London which is extant. Bonaparte summoned his two consular colleagues to him; he first reproached Monsieur Réal bitterly for having left him in ignorance of what was being plotted against him. He listened patiently to their objections: it was Cambacérès who expressed himself most vigorously. Bonaparte thanked him and passed on. That is what I have read in Cambacérès’ Memoirs which one of his nephews, Monsieur de Cambacérès, a Peer of France, has allowed me to consult, in a most obliging manner of which I retain the grateful memory. The missile once sent on its way does not return; it goes where the engineer sends it, and descends. In order to execute Bonaparte’s orders, it was necessary to violate German territory, and that territory was promptly violated. The Duc d’Enghien was arrested at Ettenheim. With him, not General Dumouriez, but only the Marquis de Thumery and a few other émigrés of little renown were found: that should have been a warning that an error had been made. The Duc d’Enghien was taken to Strasbourg. The commencement of the catastrophe of Vincennes has been recounted for us by the Prince himself: he left behind a little journal of the journey from Ettenheim to Strasbourg: the hero of the tragedy steps onto the forestage to pronounce the prologue:

BkXVI:Chap2:Sec2

Journal Of The Duc d’Enghien

‘On Tuesday the 15th of March, at Ettenheim, my house surrounded by a detachment of dragoons, pickets and military police; in total, about two hundred men, two generals, the colonel of dragoons, colonel Charlot of the Strasbourg military police, at five o’clock (in the morning). At five-thirty the doors broken open, taken to Le Moulin near La Tuilerie. My papers removed, sealed. Led in a cart, between two lines of fusiliers, to the Rhine. Embarked for Rheinau. Disembarked and marched on foot to Pfortsheim. Breakfast at the inn. Climbed into a carriage with Colonel Charlot, the sergeant of the gendarmerie, a gendarme on the box seat, and Grünstein. Arrived at Strasbourg, at Colonel Charlot’s house, towards five-thirty. Transferred, half an hour later, in a fiacre, to the citadel .................................

Sunday the 18th, they came to fetch me at one-thirty in the morning. I was not given time to dress. I embraced my unfortunate companions, and my people. I left alone with two officers of the gendarmerie and two gendarmes. Colonel Charlot announced to me that we were going to see the Divisional General, who had received orders from Paris. Instead of that, I found a carriage with six post-horses waiting in the Place de l’Église. Lieutenant Petermann climbed up beside me, sergeant Blitersdorff on the box seat, two gendarmes inside, the other outside.’

Here the shipwrecked voyager, about to be swallowed up, broke off his logbook.

Arriving about four o’clock in the evening at one of the gates of the capital, where the Strasbourg road terminated, the carriage, instead of entering Paris, followed the outer boulevard and stopped at the Château of Vincennes. The Prince, descending from the carriage in the inner courtyard, was conducted to a room in the fortress, and locked in, at which point he fell asleep. As the Prince approached Paris, Bonaparte affected an unnatural calm. On the 18th of March he left for Malmaison; it was Palm Sunday. Madame Bonaparte, who, with all her family, was told of the Prince’s arrest, spoke to him about it. Bonaparte replied: ‘You understand nothing of politics.’ Colonel Savary had become one of Bonaparte’s regular companions. Why? Because he had seen the First Consul in tears at Marengo. Men apart must suppress their own tears, they who put ordinary men under the yoke. Tears are one of those weaknesses by which a witness can render himself master of a great man’s will.

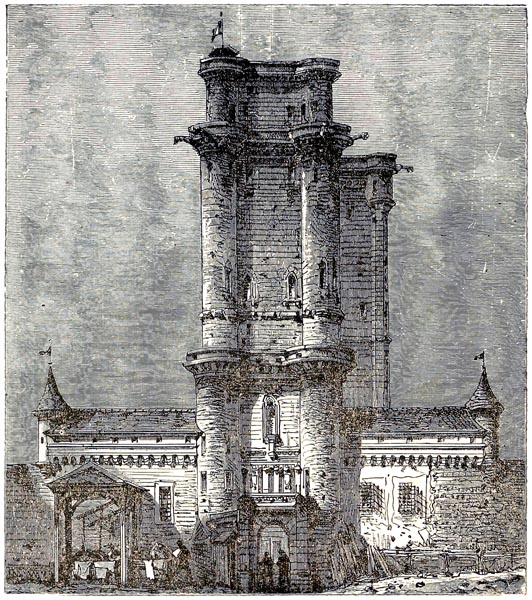

‘The Donjon Of Vincennes’

Three Vassar Girls Abroad. Rambles of Three College Girls on a Vacation Trip Through France and Spain For Amusement and Instruction. With Their Haps And Mishaps - Elizabeth Williams Champney (p39, 1883)

Internet Archive Book Images

It is certain that the First Consul drew up all the orders for Vincennes. It was stated in one of those orders, that if the sentence anticipated was a death sentence, it was to be carried out immediately. I believe that version of events, even though I cannot prove it, since the orders have vanished. Madame de Rémusat, who on the evening of the 20th March, was playing chess at Malmaison with the First Consul, heard him mutter a few lines on Augustus’ clemency; she thought that Bonaparte had come to himself, and that the Prince was safe. No; fate had pronounced its oracle. When Savary re-appeared at Malmaison, Madame Bonaparte guessed the whole unhappy business. The First Consul shut himself up alone for several hours. And then the breeze sighed, and all was over.

BkXVI:Chap2:Sec3

The Military Commission Appointed

Bonaparte’s order, of the 20th Ventôse Year XII (20th March 1804), appointed a military commission, composed of seven members nominated by the Governor-General of Paris (Murat), to meet at Vincennes, to judge the former Duc d’Enghien, accused of carrying arms against the Republic etc.

Executing this order, the same day, 20th Ventôse, Joachim Murat nominates to the aforesaid commission, seven officers; namely:

General Hulin, commanding the Grenadiers of the Consular Guard, President;

Colonel Guitton, commanding the 1st Regiment Cuirassiers;

Colonel Bazancourt, commanding the 4th Regiment Light Infantry;

Colonel Ravier, commanding the 18th Infantry Regiment;

Colonel Barrois, commanding the 96th Infantry Regiment;

Colonel Rabbe, commanding the 2nd Regiment Paris Municipal Guard

Citizen d’Autancourt, Major of the Élite Gendarmerie, who will fulfil the functions of Recording-Officer.

Interrogation By The Recording-Officer

Captain d’Autancourt, Squadron Commander Jacquin, of the Élite Legion, two gendarmes from the same corps, Lerva and Tharsis, and citizen Noirot, a lieutenant in the same corps, go to the Duc d’Enghien’s room; they wake him: he has no more than a quarter of an hour to wait before returning to his rest. The recording-officer, assisted by Molin, captain in the 18th Regiment, chosen as clerk of the court by the aforesaid recording-officer, interrogates the Prince.

Asked for his name, forenames, age and place of birth?

Replied that his name was Louis-Antoine-Henri de Bourbon, Duc d’Enghien, born the 2nd of August 1772, at Chantilly.

Asked where he had lived since his departure from France?

Replied that having accompanied his relatives, and the Army of Condé being formed, he had been completely involved in the war and that before that he was involved in the campaign of 1792, in Brabant, with the Bourbon Army.

Asked if he had been to England at any time, and if that power had granted him a regular allowance?

Replied that he had never been there: that England did grant him an allowance which was all he had to live on.

Asked what rank he held in the Army of Condé?

Replied: Commander of the Vanguard in 1796, before that campaign a volunteer at his grandfather’s headquarters, but always, since 1796, Commander of the Vanguard.

Asked if he had known General Pichegru; and had dealings with him?

Replied: I don’t think I have ever seen him. I have never met with him. I know he wished to meet me. I congratulate myself on not having known him, given the vile means they say he intended to employ, if what they say is true.

Asked if he knew ex-general Dumouriez, and had dealings with him?

Replied: No longer.

From this, the present account has been drawn up, and signed by the Duc d’Enghien, Squadron Commander Jacquin, Lieutenant Noirot, the two gendarmes and the Recording-Officer.

Before signing the final account of his interrogation, the Duc d’Enghien said: ‘I am making an official request for a personal audience with the First Consul. My name, rank, opinions and the horror of my situation make me hopeful that he will not refuse my request.’

Judgement of the Session Of The Military Commission

‘At two in the morning, on the 21st of March, the Duc d’Enghien was led to the room where the commission was sitting, and repeated what he had said during his interrogation by the Recording-Officer. He persisted in his declaration: he added that he was prepared for war, and that he wished to serve in England’s latest war with France. Being asked if he had anything to say in his own defence, he replied he had no more to say.

The President had the accused removed; the council deliberated in private, the President took a vote, starting with the most junior rank; then, having given his opinion last, by a unanimous vote declared the Duc d’Enghien to be guilty, and applied to him the article of the law so designated and in consequence condemned him to death. It was ordered that the present judgement be executed at once at the behest of the Recording-Officer, after having read the sentence to the condemned man, in the presence of various detachments of the garrison.

Completed, closed and sentence passed, in continuous session, at Vincennes, on the day, month and year above, and we have duly signed.’

The grave being completed, filled, and closed, ten years of oblivion, general consensus, and astounding glory covered it; the grass grew to the sound of salvoes announcing victory, to illuminations lighting the Papal coronation, the marriage of the daughter of the Caesars, and the birth of the King of Rome. Only a few afflicted individuals, wandering the woods, adventured a furtive glance into the depths of the moat towards the dreadful place, while a handful of prisoners observed it from the heights of the keep that enclosed them. The Restoration came: the soil of the grave was disturbed, and with it various consciences; each sought to justify itself. Monsieur Dupin the Elder published his discussion of the matter; Monsieur Hulin, President of the military commission, spoke out; Monsieur le Duc de Rovigo entered into controversy by accusing Monsieur de Talleyrand; a third party replied on Monsieur de Talleyrand’s behalf, and Napoleon raised his great voice from the rock of St Helena.

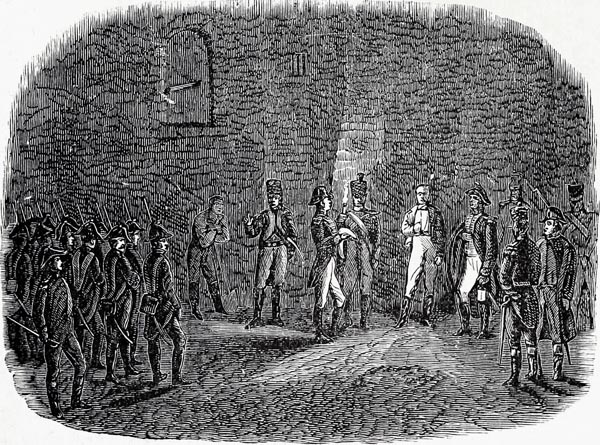

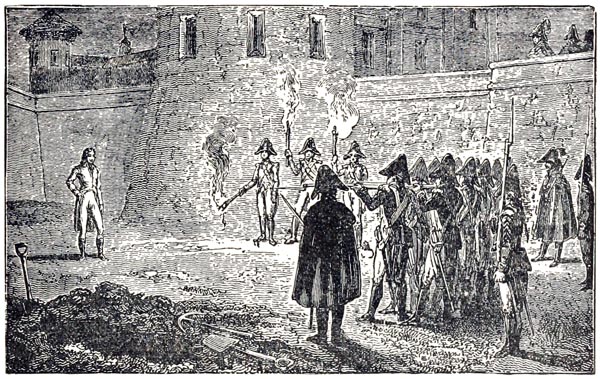

‘Execution Of The Duke Of Enghien’

The Student's France, a History Of France From the Earliest Times to the Establishment of the Second Empire In 1852 - William Henley Jervis (p617, 1870)

Internet Archive Book Images

These documents should be reproduced and studied, in order to assign to each of the actors the role he fulfilled and the place which he ought to occupy in the drama. It is night, and we are at Chantilly; it was night when the Duc d’Enghien was at Vincennes.

Book XVI: Chapter 3: The Year 1804

Chantilly, November 1837

BkXVI:Chap3:Sec1

When Monsieur Dupin published his pamphlet, he sent me a copy of it with this letter:

Paris, this 10th November 1823.

‘Monsieur le Vicomte,

Please accept a copy of my publication regarding the assassination of the Duc d’Enghien.

It would have appeared long before, if I had not desired, before all, to respect the wishes of Monseigneur le Duc de Bourbon, who having knowledge of my work, had expressed his desire that the deplorable affair not be disinterred.

But Providence having allowed others to take the initiative, it became necessary to make the truth known, and after being assured that no one wished me to keep silence about the matter any longer, I have spoken with freedom and sincerity.

I have the honour to be with profound respect,

Monsieur le Vicomte,

Your Excellency’s most humble and obedient servant,

DUPIN.’

Monsieur Dupin whom I congratulated and thanked, revealed in his accompanying letter a little known and touching quality of the noble and compassionate virtues possessed by the victim’s father. Monsieur Dupin began his pamphlet thus:

‘The death of the unfortunate Duc d’Enghien is one of those events which most grieved the French nation: it has dishonoured the Consular government.

A young Prince, in the flower of his years, surprised deceitfully on foreign soil, where he lived in peace, under the protection of the rights of man; carried off violently to France; dragged in front of so-called judges who, in no sense had the right to act as his; accused of imaginary crimes; deprived of the aid of a defence counsel; interrogated and condemned behind closed doors; put to death at night in the moat of a fortress that acted as a State prison, so many unknown virtues, and so many dear hopes thus destroyed, will forever render this catastrophe one of the most revolting acts to which an absolute government could abandon itself!

If the forms were not respected; if the judges were incompetents; if they did not even take the trouble to give, in making their judgement, the dates and texts of the laws on which they pretended to base their sentence; if the poor Duc d’Enghien was shot by virtue of an order left unsigned.and not regularised until after the blow was struck, then he is no longer simply the innocent victim of a legal error; it is time to give the matter its true name: it was an odious assassination.’

This eloquent exordium leads Monsieur Dupin to an examination of the evidence: he shows firstly the illegality of the arrest; the Duc d’Enghien was not arrested in France; he was not a prisoner of war, because he was not armed when captured; he was not a prisoner on civil grounds, since extradition was not requested; it was a violent abduction of an individual, comparable to those of Tunisian and Algerian pirates, an attack by brigands, incursio latronum.

The legal expert goes on to consider the incompetence of the military commission; information concerning so-called plots, which may have been woven against the State, has never been the responsibility of military commissions.

Following that he comes to an examination of the trial:

‘The interrogation (Monsieur Dupin continues) took place on the 29th Ventôse at midnight. On the 30th Ventôse, at two in the morning, the Duc d’Enghien was brought before the military commission.

In the minutes of the trial one reads: Today, the 30th Ventôse Year XII of the Republic, at two in the morning: those words, two in the morning, which could only have been set down there because it was indeed that hour, were erased from the minutes, without being replaced by any other indication.

Not one single witness against the accused was produced, or heard.

The accused is declared guilty! Guilty of what? The judgement does not say.

Every judgement which pronounces sentence must contain a citation of the law in virtue of which the sentence is applied.

Well, in this case, none of the forms were applied: there is no mention in these proceedings that the commission had before it a copy of the law; nothing certifies that the President had read the text before applying it. Far from doing so, the judgement, in its material expression, proves that the commission declared its sentence without knowing either the date or the content of the law; since it has left blank in the minutes, regarding the sentence, the date of the law, the article number, and the place destined to receive its text. And yet it is on the basis of a sentence framed in this unsatisfactory way that the noblest of blood was spilt by the executioners!

Deliberations may be carried out in secret: but the declaration of the judgement has to be made in public; it is the Law furthermore that tells us this. Now the judgement of 30th Ventôse does indeed say: The council deliberated behind closed doors; but there is no mention there of the doors being re-opened, there is nothing there saying that the result of those deliberations was declared in public session. If it did say so, how could anyone credit it? A public session, at two in the morning, in the keep of Vincennes, while every entrance to the castle was guarded by elite gendarmes! In the end, they did not even take the precaution of resorting to a lie; the judgement is silent on this point.

‘Vue du Donjon de Vincennes’

Les Merveilles du Nouveau Paris - Joseph Décembre, Edmond Alonnier (p396, 1867)

Internet Archive Book Images

The judgement is signed by the President and the six other members of the commission, including the Reporting-Officer; but it is noticeable that the minute was not signed by the Clerk of the Court, whose confirmation was needed however to grant it authenticity.

The sentence ends in this terrible phrase: to be executed IMMEDIATELYat the behest of the Recording Officer.

IMMEDIATELY! Desperate words, the work of judges! IMMEDIATELY! And yet a law, that of 15th Brumaire Year VI, expressly granted the right of appeal against all military judgements!’

Monsieur Dupin, passing on to the execution, continues thus:

‘Interrogated at night, tried at night, the Duc d’Enghien was killed at night. That terrible sacrifice had to be consummated in darkness, so that all the laws may be said to have been violated, all, even those which prescribed that executions should be conducted in public.’

Our legal expert now comes to the irregularities in the hearing:

‘Article 19 of the law of 13th Brumaire, Year V, lays down that after ending the interrogation, the Recording-Officer shall tell the accused to select a friend to defend him. – The accused shall have the right to choose his defence from any class of citizen present at the time; if he declares himself unable to choose, the Recording-Officer shall choose for him.

Oh, the Prince certainly had no friends (an allusion to a disgraceful reply it is said they made to Monsieur le Duc d’Enghien) among those who surrounded him! That cruel statement was made to him by one of the actors in that horrible scene!...Alas! Why were we not present? Why was the Prince not permitted to make an appeal to the Paris Bar? There, he would have found friends in adversity, defenders in misfortune. It was with a view to making this judgement presentable to the public eye that a new version of it seems to have been prepared when time allowed. The later substitution of this second version, more regular in appearance that the first (though equally unjust) in no way reduced the odiousness of ordering the Duc d’Enghien’s execution based on a threadbare judgement signed in haste, and which as yet has never received a full explanation.’

Such is Monsieur Dupin’s illuminating pamphlet. However I am not sure myself, regarding an act of the kind that the author examines, that greater or lesser irregularity is of any importance: if the Duc d’Enghien had been strangled in a post-chaise from Strasbourg to Paris, or killed in the woods of Vincennes, the thing is the same. But is it not providential to see, after many years, one set of men demonstrating the irregularity of a murder in which they were not involved, while another set rush, without it being demanded of them, to public interrogation? What have they heard? What voice from on high has summoned them to appear?

Book XVI: Chapter 4: General Hulin

Chantilly, November 1837

BkXVI:Chap4:Sec1

After the grand legal expert, here comes a blind veteran: he commanded grenadiers of the Old Guard; enough said, to the brave. His final wound in the jaw he received from Malet, whose ineffectual lead was left embedded in a visage that did not flinch from the bullet. Afflicted by blindness, retired from society, having only family cares for consolation (these are his very words), the Duc d’Enghien’s judge seems to rise from the grave at the command of the Sovereign Judge; he pleads his cause without deceit or excuses:

‘Let no one be mistaken,’ he says, ‘regarding my intentions. I am not writing out of fear, since my person is protected by laws issuing from the throne itself, and under the government of a just king, I am not apprehensive of arbitrary violence. I am writing in order to speak the truth, even regarding things which may work against me. So, I do not seek to justify either the form or content of the judgement, but to show that it was rendered under the Empire and in the midst of a fatal combination of circumstances; I wish to distance my colleagues and myself from the idea that we were motivated by party. If we are still to be blamed for it, I would like them also to say of us: “They were most unfortunate!”’

General Hulin confirms that, named as President of the military commission, he did not know its aim; that he arrived at Vincennes, still ignorant of it; that the other members of the commission were equally in ignorance; that the Governor of the château, Monsieur Harel, on being asked, replied that he himself knew nothing, adding these words: “What would you have? I am nothing here. All is done without my orders or involvement: it is another who commands here.”’

It was ten o’clock in the evening when General Hulin was freed from his uncertainty by the communication of documentary information to him.

– The interview was over by midnight, when the examination of the prisoner by the Recording-Officer was complete. “Reading over the documents, ‘said the President of the commission, ‘gave rise to an incident. We remarked that at the end of the interrogation conducted before the Reporting-Officer, the Prince, before signing, traced, with his own hand, some lines in which he expressed his desire to have a meeting with the First Consul. One member of the commission proposed that this demand should be transmitted to the government. The commission had decided to refer the matter; but at that very moment, the general, who had just come to stand behind my chair, suggested that the request would be inopportune. Moreover, we found no legal arrangement which authorised us to defer judgement. The commission then passed on, setting aside time, after the discussions, to consider the prisoner’s wish.’

That is what General Hulin recounts. Now one can also read this passage in the Duc de Rovigo’s pamphlet: ‘There were sufficient persons there to make it difficult for me, arriving last, to get behind the President’s seat where I managed to place myself.’

Was it the Duc de Rovigo then who was standing behind the chair occupied by the President? But what right had he, or any other, having no role on the commission, to intervene in the discussions of that commission and suggest that a request was inopportune?

Let us hear the commander of grenadiers of the Old Guard speak of the courage of Condé’s young son; he knew about such things:

‘I proceeded to interrogate the accused; I have to say, he appeared before us with noble assurance, rejecting totally any involvement directly or indirectly in a plot to assassinate the First Consul; but he did confess also to having borne arms against France, saying, with a courage and pride which did not allow for our varying the point, even in his own interest: “That he had maintained the rights of his family, and that a Condé could never return to France except under arms. My birth, my opinions,” he added, “will render me forever an enemy to your government.”

The firmness of his confession was the despair of his judges. A dozen times we set him a course towards revising his statements, always he persisted in an unshakeable manner: “I recognise,” he said at intervals, “the honourable intentions of the members of the commission, but I can by no means take advantage of what they offer me.” And regarding the warning that the military commission’s judgement was final: “I know,” he replied to me, “and I do not deceive myself as to the danger I court; I only wish for an interview with the First Consul.”’

Is there a more moving page of our history? New France judging the former France, rendering it homage, presenting arms to it, saluting it with the flag while condemning it; the tribunal established in the fortress where the Great Condé, as a prisoner, cultivated flowers: the general of grenadiers in Bonaparte’s Guard, sitting opposite the last descendant of the victor of Rocroi, moved with admiration for the defenceless accused, a man forsaken on this earth, interrogating him while the sound of the gravedigger digging the grave mingled with the assured replies of the young soldier! A few days after the execution, General Hulin exclaimed: ‘Oh what a brave young man! What courage! I would hope to die like him!’

General Hulin, after speaking about the minutes, and the second version of the judgement, says: ‘As for the second version, the sole truth is, since it did not contain the order for immediate execution, but only the immediate reading of the sentence to the condemned man, that the immediate execution was not the commission’s doing, but solely those who took it upon their own responsibility to hasten that fatal deed.

Alas, we had many second thoughts! The judgement was barely signed before I sent a letter in which, rendering myself interpreter of the commission’s unanimous wish, I wrote to the First Consul to make him aware of the wish that the Prince had expressed to have an interview with him, and also to entreat him to ease the difficulty which the constraints of our situation had not enabled us to evade.

It was at that moment that a man spoke, who was constantly present in the judgement chamber, and whom I would name in an instant, if I did not consider that, even though defending myself, I ought not to accuse him. – What are you doing? He asked me, drawing close to me. – I am writing to the First Consul, I replied, to express to him the wishes of the council and those of the condemned man. – Your business is done with, he said to me taking away the pen: now it is my concern.

I swear that I thought, and several of my colleagues did also, that he meant: It is my concern to advise the First Consul. The reply, taken in that sense, allowed us to hope that the request would be transmitted none the less. And how should we arrive at the idea that whoever it was who was with us, had been ordered to ignore the formalities the law requires?’

The whole secret of that sad catastrophe is in this deposition. The old soldier, who, always prepared to die on the field of battle, had learnt from death the language of truth, concludes with these words:

‘I have spoken about what passed in the hallway next to the meeting room. Private conversations took place; I was waiting for my carriage, which being unable to enter the inner courtyard, like those of other members, delayed my departure and theirs; we were ourselves locked in, without anyone being able to communicate from outside, when there was an explosion: a terrible noise which echoed in the depths of our souls and froze them with fear and dread.

Yes, I swear, in the name of all my colleagues, that execution was not authorised by us: our judgement stated that it would be sent by despatch to the Minister of War, the Chief Justice, and the Governor-General of Paris.

The order of execution could not have been properly decreed except by the latter; the copies had not yet been despatched; they could not reach their destination before some part of the day had passed. Returning to Paris, if I had sought out the Governor, the First Consul, what did I know? And all at once a fearful noise had just revealed to us that the Prince no longer existed!

We did not know if he who had hastened that sad execution, so cruelly, had orders to do so: if he had not, he alone was responsible; if he had, the commission, not privy to the orders, the commission, set up privately, the commission, whose first wish was for the health of the Prince, could have done nothing to prevent, or evade the outcome. One cannot accuse it of causing that event.

The twenty years that have passed since have not lessened the bitterness of my regrets. Let them accuse me of ignorance, of error, I agree; let them reproach me with obedience to that which I would well know how to evade today, in similar circumstances; my attachment to a man whom I thought destined to work the good of my country; my loyalty to a government which I thought legitimate then and which had received my pledge; but let them take account of the fact that I, and my colleagues, had been summoned to pronounce judgement in the midst of fatal circumstances.’

The defence is weak, but you repent General: may peace be with you! If your judgement acted as the last Condé’s order to depart, you will march, in the vanguard of the dead, to rejoin that last conscript of our former country. The young soldier will take pleasure in sharing his slumber with the grenadier of the Old Guard; the France of Fribourg and the France of Marengo will rest together.

Book XVI: Chapter 5: The Duc de Rovigo

Chantilly, November 1837

BkXVI:Chap5:Sec1

Monsieur le Duc de Rovigo, striking his breast, takes his place in the procession which comes to confess before the grave. I had been in the confidence of the Minister of Police for some time; he was swayed by the influence he supposed me to have had in the return of the legitimacy: he communicated to me a part of his Mémoires. Men, in his position, speak of what they have done with marvellous candour; they have no suspicion of what they are saying against themselves: accusing themselves without being aware of it, they never suspect there might be another opinion to their own, either regarding the functions with which they were charged, or their mode of conduct. If they have been lacking in loyalty, they never consider they have violated their oath; if they have taken upon themselves roles repugnant to other characters than theirs, they believe they have rendered great service. Their naivety does not justify them, but it excuses them.

Monsieur le Duc de Rovigo consulted me about the chapters where he treats of the Duc d’Enghien’s death; he wished to know my thoughts, precisely because he knew what I had done; I was grateful for this mark of esteem, and repaying frankness with frankness, advised him not to publish. I said to him: ‘Let it all die; in France it doesn’t take long to forget. You imagine that you will absolve Napoleon of reproach and throw the blame on Monsieur de Talleyrand; well, you have not sufficiently justified the former, and not sufficiently condemned the latter. You are exposing your flank to your enemies; they will not lose the opportunity to reply. What need is there for you to remind the public that you commanded the elite gendarmerie at Vincennes? They are unaware of the direct involvement you had in that unhappy event and you will be revealing it to them. General, throw the manuscript in the fire: I am speaking in your own interest.’

Imbued with the governmental maxims of the Empire, the Duc de Rovigo thought those maxims equally suited to the legitimate monarchy; he had the conviction that his pamphlet would re-open the gates of the Tuileries to him.

It is partly in the light of his writings that posterity will see the ghosts of mourning silhouetted. I wished to hide the accused, he who had come seeking my help in the night; he would not accept the protection of my hearth.

Monsieur de Rovigo tells the story of the departure of Monsieur de Caulaincourt, whom he does not name; he speaks of the abduction from Ettenheim, the journey of the prisoner to Strasbourg, and his arrival at Vincennes. After an expedition to the Normandy coast, General Savary returned to Malmaison. He was summoned, at five in the evening on the 19th of March 1804, to the office of the First Consul, who gave him a sealed letter to take to General Murat, the Governor of Paris. He flew to the General’s residence, met the Minister for Foreign Affairs, and received the order to take the elite gendarmerie and go to Vincennes. He arrived there at eight in the evening and saw the members of the commission arriving. He later reached the room where the Prince was being tried, on the 20th, at one in the morning, and went to sit behind the President. He reports the Duc d’Enghien’s replies, more or less as they are reported in the proceedings of the solitary session. He told me that the Prince, after he had given his last response, quickly removed his cap, set it down on the table, and like a man resigning life, said to the President: ‘Sir, I have nothing more to say.’

Monsieur de Rovigo insists that the meeting was not at all mysterious: ‘The doors of the room,’ he affirms, ‘were open freely to anyone who might be present there at that hour.’ Monsieur Dupin has already noted this tortuous reasoning. Regarding that occasion, even Monsieur Achille Roche, who usually seems to write on behalf of Monsieur Talleyrand, exclaims: ‘The meeting was in no way mysterious! At midnight, it was held in the inhabited part of the castle; in the inhabited part of a prison! Who assisted at that meeting? Gaolers, soldiers, executioners.’

No one can give more precise details as to the time and place where the lightning stuck than Monsieur le Duc de Rovigo; let us hear him:

‘After the delivery of the verdict, I retired with the officers of my corps who, like me, had assisted in the discussion, and went to rejoin the troops on the esplanade of the Château. The officer, who commanded the infantry in my legion, came to tell me with deep emotion, that a picket had been demanded of him to execute the military commission’s sentence: – Supply them, I replied. – But, where shall I place them? – There, where you won’t wound anyone. For the inhabitants of the heavily populated areas of Paris were already afoot on their way to the various markets.

After taking a good look round, the officer chose the moat as being the best place to avoid wounding anyone. Monsieur le Duc d’Enghien was taken there by the stairs of the entrance tower on the Park side, and there heard the sentence, which was executed.’

Beneath this paragraph, one finds a note by the author of the memoir: ‘Between the sentence and the execution the grave was dug. That is why it has been said that the grave was dug before the verdict.’

Unfortunately, there is deplorable negligence here: ‘Monsieur de Rovigo claims,’ says Monsieur Achille Roche, apologist for Monsieur de Talleyrand, ‘that he was obeying orders! Who transmitted the order for the execution to him? It appears it was a Monsieur Delga, killed at Wagram. But whether it was Monsieur Delga, or not, if Monsieur Savary is in error in naming Monsieur Delga, doubtless no one today will claim the glory that he attributes to that officer. Monsieur de Rovigo is accused of having hastened the execution; he replies that it was not him: a man who has since died told him he had given the orders to hasten it.’

The Duc de Rovigo is not satisfactory on the subject of the execution, which he says took place in daylight; however that changes nothing, it would merely remove a torch from the tragedy.

‘At sunrise, in the open air, would it need a lantern,’ the General asks, ‘in order to see a man, at six paces! It was only the case that the sun,’ he adds, ‘was not clear and bright; since a fine rain had fallen all night, and a damp mist remained which delayed his appearance. The execution took place at six in the morning, the fact is attested to by indisputable documents.’

‘Mort du Duc d’Enghien’

L'Histoire de France Depuis 1789 Jusqu'en 1848, Racontée à mes Petits-Enfants, par M. Guizot. Leçons Recueillies par Madame de Witt, Vol 01 - François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (p607, 1878)

The British Library

But the General neither supplies, nor indicates the whereabouts of, these documents. The progress of the trial demonstrates that the Duc d’Enghien was sentenced at two in the morning and was shot immediately. Those words, two in the morning, initially written down at the beginning of the trial, were afterwards erased from the minutes. The official report of the exhumation, on the deposition of three witnesses, Madame Bon, Monsieur Godard, and Monsieur Bounelet (the latter had helped dig the grave), proves that he was put to death at night. Monsieur Dupin the Elder recalls the circumstance that a taper had been pinned over the Duc d’Enghien’s heart, to serve as a focal point to aim at, or held by the Prince with a firm hand, with the same intention. They spoke of a large stone removed from the grave with which the subject’s head would have been crushed. Finally, the Duc de Rovigo is claimed to have taken possession of various remains of the victim: I myself believed these rumours; but the legal documents prove them to be unfounded.

‘Hertigen af Enghein Arkebusera’

Ett Hundra År: en Återblick på det Nittonde Seklet - Carl Fredrik Peterson (p85, 1892)

Internet Archive Book Images

In the official report, dated Tuesday the 20th March 1816, by the doctors and surgeons, regarding the exhumation of the body, it was acknowledged that the skull was fractured, that the upper jaw, entirely separated from the bones of the face, was furnished with twelve teeth; that the lower jaw, completely fractured, was split in two and revealed only three teeth. The body was face down, the head lower than the feet; the neck vertebrae were encircled by a gold chain.

The second official report of the exhumation (with the same date, 20th March 1816), the General Report, certifies that they found, along with the rest of the skeleton, a leather purse containing eleven gold pieces, seventy gold pieces in sealed rolls, some hair, the remains of his clothes, and fragments of his cap bearing the marks of the bullets that had passed through it.

So, Monsieur de Rovigo had removed no relics; the earth which held them has rendered them again, and testified to the General’s probity; no taper had been pinned over the Prince’s heart, the fragments of it would have been found, like those of the torn cap; no large stone had been removed from the grave; the pickets’ fire at six paces had sufficed to shatter the skull, and separate the upper jaw from the bones of the face, etc.

The only items this mockery of human vanities lacks are the similar immolation of Murat, the Governor of Paris, the death of the captive Bonaparte, and this inscription engraved on the Duc d’Enghien’s coffin: ‘Here is the body of the very noble and mighty Prince of the blood, Peer of France, died at Vincennes on the 21st of March 1804, aged 31 years 7 months and 19 days.’ The body was bare shattered bones; the noble and mighty Prince, the broken fragments of a soldier’s corpse: not a word to recall the catastrophe, not a word of blame or grief in this epitaph engraved by a family in tears; what a prodigious effort of respect the century shows to revolutionary works and sensitivities! They have hastened likewise to get rid of the Duc de Berry’s mortuary chapel.

What futility! Bourbons, returning uselessly to your palaces, you have to do only with exhumations and funerals; your time has passed. God willed it! France’s former glory died beneath the gaze of the Great Conde’s shade, in a moat at Vincennes: perhaps at the very place where Louis IX, whom one ever approached as if he were a saint, ‘sat beneath an oak, where any who had business with him came to speak with him, without hindrance by bailiffs or others; and when he heard whatever required amends, in the words of those who spoke for others, he amended it with his own lips, and all those who had business before him were around him’ (JOINVILLE).

The Duc d’Enghien asked to speak to Bonaparte: he had business before him; he was not heard! Who was there, on the edge of the outworks, contemplating, in the depths of the moat, those weapons, those soldiers hardly illuminated by a lantern in the mist and shadow, as if in eternal night? Where was the light placed? Did the Duc d’Enghien have his open grave at his feet? Was he required to stride across it to place himself at the distance of six paces mentioned by the Duc de Rovigo?

There is a letter extant from the nine-year old Duc d’Enghien to his father the Duc de Bourbon; he writes to him: ‘All the Enghiens are fortunate; he of the battle of Cerisoles, he who won the battle of Rocroi: I hope to be so too.’

Is it true that the victim was refused a priest? Is it true that he had difficulty in finding anyone whom he could charge with carrying to a woman a last token of his attachment? What did feelings of piety or tenderness matter to his executioners? He was there to die, the Duc d’Enghien, to die.

Through the ministrations of a priest, the Duc d’Enghien had married Princess Charlotte de Rohan secretly: in those times when the country was in turmoil, a man, by reason of his rank, could be subjected to a thousand political restrictions; in order to enjoy what society in general allows all of us, he was obliged to hide. This legitimate marriage, common knowledge today, heightened the splendour of his tragic end; for heavenly mercy he substituted heavenly glory: religion perpetuated the unfortunate man’s pomp when, following the completion of the catastrophe, a cross was raised over that deserted place.

Book XVI: Chapter 6: Monsieur de Talleyrand

Chantilly, November 1837

BkXVI:Chap6:Sec1

Following Monsieur de Rovigo’s pamphlet, Monsieur de Talleyrand presented a supporting memoir to Louis XVIII: this memoir, which I have not seen, and which ought to have clarified everything, clarified nothing. Named as plenipotentiary minister to Berlin, in 1820, I dug up, from the ambassadorial archives, a letter from Citizen Laforest, writing to Citizen Talleyrand, on the subject of Monsieur le Duc d’Enghien. This vigorous letter is the more honourable in that its author does not hesitate to compromise his career, while receiving no reward by way of public opinion, his action remaining unknown: a noble abnegation by a man who, by his very obscurity, condemned the good he had done to obscurity also.

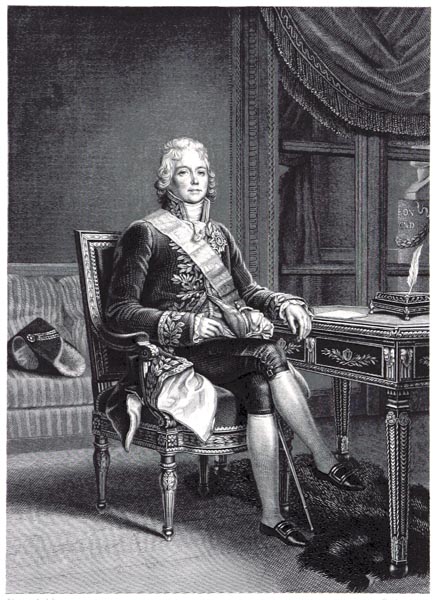

‘Talleyrand’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p29, 1845)

The British Library

Monsieur de Talleyrand received the lecture, and was silent; at least, I have not found anything from him in the identical archive, concerning the Prince’s death. Yet, the Minister for Foreign Affairs sent word to the Minister for the Elector of Baden, on the 2nd Ventôse: ‘that the First Consul has thought it his duty to give an order to the detachments to go to Offenbourg and Ettenheim, and there seize the instigators of unheard-of conspiracies which, by their nature, put beyond the law all those who manifestly have been involved in them.’

Extracts from the writings of Generals Gourgaud and Montholon, and of Doctor Warden place Bonaparte on stage: ‘My minister,’ he said, ‘represented to me most strongly that it was essential to seize the Duc d’Enghien, although he was on neutral territory. But I still hesitated, and the Prince of Benevento twice brought me the order for his arrest, for my signature. It was not until later however that I was convinced of the urgency for such an action, and decided to sign.’

According to the Mémorial de Saint-Hélène, the following words escaped Bonaparte: ‘The Duc d’Enghien carried himself with great bravery before the tribunal. On his arrival at Strasbourg, he wrote me a letter: that letter was handed over to Talleyrand who kept it until the execution.’

I think little of this idea of a letter: Napoleon has transformed into a letter the request that the Duc d’Enghien made to talk to the Conqueror of Italy, or rather the few lines expressing this request, which, before signing the interrogation attributed to him in front of the Recording-Officer, the Prince had traced in his own hand. However, since this letter has not been found, a rigorous conclusion must be that it was never written: ‘I know,’ said the Duc de Rovigo, ‘that in the first days of the Restoration, in 1814, one of Monsieur de Talleyrand’s secretaries searched endlessly in the archives, beneath the Museum gallery. I have this information from the person who received the order to allow him entry there. He did the same at the War Office, searching for the notes from the trial of Monsieur le Duc D’Enghien, of which only the record of the sentence remained.’

The fact is correct: all Monsieur Talleyrand’s diplomatic papers and notably his correspondence with the Emperor and the First Consul, were transported from the Museum archives to his house on the Rue Saint-Florentin; part were destroyed; the rest were tucked away in a stove, that they neglected to light: the prudence of the minister could do no more to counteract the rashness of the Prince. The documents were retrieved unburned; someone thought them worth keeping: I have held in my hands and read with my own eyes one of Monsieur de Talleyrand’s letters; it is dated the 8th of March 1804 and relates to the arrest of Monsieur le Duc d’Enghien which had not yet been performed. The Minister invites the First Consul to act harshly against his enemies. I was not allowed to retain the letter, and only remember these two passages: ‘If justice obliges us to punish rigorously, politics requires us to punish without exception...I indicated Monsieur de Caulaincourt to the First Consul, as one to whom he could give his orders, and who would execute them with discretion as well as loyalty.’

Will this document by the Prince de Talleyrand appear in its entirety one day? I know not; but what I do know is that it was still in existence two years ago.

There was an agreement in council to arrest the Duc d’Enghien. Cambacères, in his unpublished Memoirs affirms, and I believe it, that he opposed the arrest; but in recounting what he said, he does not say how he replied.

As for the rest, the Mémorial de Saint-Hélène denies the appeals for clemency to which Bonaparte might have been exposed. The imaginary scene in which Josephine on her knees begged mercy for the Duc d’Enghien, grasping a piece of her husband’s clothing and being dragged along by that inexorable husband, is one of those melodramatic inventions with which our writers of fable today compose true histories. Josephine had no knowledge, on the evening of the 19th of March, that the Duc d’Enghien was being tried; she only knew of his arrest. She had promised Madame de Rémusat to interest herself in the Prince’s fate. When the latter returned to Malmaison with Josephine, on the evening of the 19th, it was remarked that the future Empress, instead of being wholly preoccupied by the danger surrounding the prisoner at Vincennes, often put her head out of the carriage window to look at a general melee among her following: female coquetry had banished any thought that might have saved the Duc d’Enghien’s life. It was not till the 21st of March that Bonaparte said to his wife: ‘The Duc d’Enghien has been shot.’ That phrase, uttered while looking at a clock, has been wrongly attributed to Monsieur de Talleyrand.

The Memoirs of Madame de Rémusat, which I have read, are extremely interesting regarding the internal details of the Imperial Court. The author burnt them during the Hundred Days, and then wrote them anew: they are only memories written from memory; the colouring is weak; but Bonaparte is always shown there nakedly and judged impartially.

The men attached to Napoleon say that he knew nothing of the death of the Duc d’Enghien until after the execution of the Prince: this idea appears to receive some support from the anecdote repeated aloud by the Duc de Rovigo, concerning Réal’s visit to Vincennes, if the anecdote is true. Once the death had been brought about by revolutionary party intrigue, Bonaparte recognised it as a fait accompli, in order not to annoy those whom he considered powerful: this ingenious explanation will not do.

Book XVI: Chapter 7: Their various roles

BkXVI:Chap7:Sec1

Summarising these facts now, this is what they prove to me: Bonaparte wanted the Duc d’Enghien dead; no one had made that death a condition for his accession to the throne. Such a supposed condition is one of those political subtleties that pretend to find occult causes for everything. – However, it is probable that certain compromised individuals did not view without pleasure the idea of the First Consul being at odds with the Bourbons forever. The trial at Vincennes was an affair that owed itself to Bonaparte’s violent temperament, a fit of cold anger fed by his minister’s reports.

Monsieur de Caulaincourt is not guilty of having executed the order of arrest.

Murat only had to reproach himself for transmitting general orders and not having had the strength to avoid doing so.

The Duc de Rovigo is found to have been charged with the execution; he probably had secret orders: General Hulin insinuates as much. Who would have dared take it upon himself to carry out a sentence of death on the Duc d’Enghien, if he had not been acting on Imperial orders?

As for Monsieur de Talleyrand, priest and gentleman, he inspired and prepared the ground for the murder by insistently prodding Bonaparte: he feared the return of the Legitimacy. It would be possible, by collating what Napoleon said at St Helena and the letters which the Bishop of Autun wrote, to prove that the latter played a vital role in the death of the Duc d’Enghien. It is in vain to object that the worldliness, character and education of the minister would distance him from violence, that corruption, to him, would have been a waste of energy; the fact would nevertheless remain that he persuaded the Consul to order the fatal arrest. That arrest of the Duc d’Enghien on the 15th of March, was not unknown to Monsieur Talleyrand; he was in daily communication with Bonaparte and conferred with him; during the interval which elapsed between the arrest and the execution, did Monsieur de Talleyrand, himself, the ministerial instigator, repent, did he say a single word to the First Consul in favour of the unfortunate Prince? It is natural to believe that he applauded the execution of the sentence.

The military commission tried the Duc d’Enghien, but with sadness and repented of it.

Such was, judging conscientiously, impartially, and strictly, the true part each played. My fate has been too closely tied to that catastrophe for me not to have tried to cast light among shadows and expose the details. If Bonaparte had not killed the Duc d’Enghien, if he had grown closer and closer to him (and his liking for him took him in that direction), what would the result have been for me? My literary career was over; entering fully into a political career, where I have proved what I might have done by my involvement with the War in Spain, I would have become rich and powerful. France might have gained from my reconciliation with the Emperor; I myself would have been lost. Perhaps I might have succeeded in maintaining some idea of liberty and moderation in the great man’s mind; but my life, ranking among those one calls fortunate, would have been deprived of what has given it character and honour: poverty, conflict, and independence.

Book XVI: Chapter 8: Bonaparte: his sophistry and remorse

Chantilly, November 1837

BkXVI:Chap8:Sec1

Finally the principal accused appears, after all the others: he ends the parade of blood-stained penitents. Let us suppose that a judge had the person named Bonaparte appear before him, as the Recording-Officer had the person named d’Enghien appear; let us suppose that we had the minutes of the later interrogation before us in the same form as the earlier; read and compare:

On being asked his name and forenames?

– He replied that his name was Napoléon Bonaparte.

On being asked where he has resided since he left France?

– He replied: at the Pyramids, Madrid, Berlin, Vienna, Moscow,

and St Helena.

On being asked what rank he occupied in the Army?

– He replied: Commander of the Vanguard of the Armies of God. No other response emerges from the mouth of the defendant.

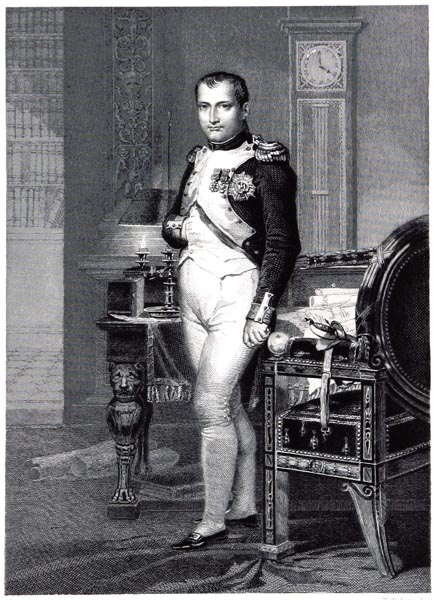

‘Napoléan’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p85, 1845)

The British Library

The various actors of the tragedy are charged together; Bonaparte alone denies guilt in person; he does not bow his head, he stands upright; he cries, like the Stoic: ‘Pain, I will never accept you as evil!’ But if in his pride he will never admit anything to the living, he is forced to confess to the dead. This Prometheus, the vulture at his breast, thief of celestial fire, believed himself superior to all, and he is forced to respond to the Duc d’Enghien whom he made dust before his time: the skeleton, a relic on which he bore down, interrogates him and masters him through divine necessity.

Domesticity and the army, the antechamber and the tent, had their representation on St Helena; a servant, estimable in his loyalty to his chosen master, placed himself beside Napoleon like an echo in his service. Foolishness imitated fable, by giving him a tone of sincerity. Bonaparte was Destiny; like her the outward form deceived enchanted minds; but at the root of these impostures, one heard that inexorable truth ring out: ‘I am!’ And the universe felt the weight of it.

The author of the most reliable work concerning St Helena exposes a theory Napoleon invented for the benefit of murderers; the voluntary exile held as Gospel truth a murderous chatter with pretensions to profundity, which alone could explain the life of Napoleon, such as he wished to arrange it, and as he pretended it had been written. He left instructions for his neophytes: Monsieur le Comte de Las-Cases learnt his lessons without being aware; the prodigious prisoner, wandering in solitary walks, drew his credulous adorer after him with lies, as Hercules suspended men from his mouth by golden chains.

‘The first time,’ says the honest chamberlain, ‘that I heard Napoleon pronounce the name of the Duc d’Enghien, I blushed with embarrassment. Happily, I was walking behind him on a narrow path or he could not have missed seeing it. Nevertheless, when, for the first time, the Emperor developed his whole account of that event, its details and secondary incidents; when he revealed his various motives with his strict logic, luminously, carried away, I must confess the affair seemed to acquire a somewhat new appearance. The Emperor often dealt with this subject, which allowed me to remark in his person those characteristic nuances which were so pronounced. I was able to see in him very distinctly on that occasion, and many other times, the private man debating with the public man, and the natural sentiments of his heart grappling with his pride and the dignity of his position. In the un-guardedness of intimacy, he showed himself not indifferent to the unfortunate Prince’s fate; but as soon as it was a question of the public, it was altogether another thing. One day, after having spoken to me of the fate and youth of the unfortunate man, he ended by saying: – “And I have learnt since, my dear friend, that he regarded me favourably; they tell me he never spoke of me without admiration; and yet this is the justice handed out down here!” – And these latter words were spoken with a significant expression, all the lines of his features appearing so harmonious, that if the man Napoleon pitied had been in his power at that moment, I am quite sure that, whatever his intentions and acts had been, he would have been pardoned with ardour. The Emperor was accustomed to consider that affair under two quite distinct headings: that of common law or established justice, and that of natural law or a violent lapse.

Between us and in confidence, the Emperor said that the fault, at root, could be attributed to an excess of zeal in those around him, or to private designs, or ultimately to mysterious intrigues. He said that he been under unexpected pressure, that his thoughts had been so to speak taken by surprise, his action precipitated, the outcome pre-determined. “Assuredly,” he said, “if I had been made aware at the time of certain particulars concerning the Prince’s nature and opinions; if above all I had seen the letter he wrote to me which was not passed to me, God knows with what motive, until after he was no more, I should certainly have pardoned him.” And it was easy for us to see that his nature and feelings alone dictated these words of the Emperor, and to us alone; for he would have felt himself humiliated that anyone could believe for an instant that he sought to blame others, or descended to self-justification; his fear in that regard, or his susceptibility, was such that in speaking to strangers or dictating for the public on this subject, he restrained himself from declaring that, if he had known about the Prince’s letter, perhaps he would have pardoned him, seeing the great political advantages that he could have accrued from doing so; and, tracing his last thoughts with his own hand, which he assumed must be sacred to his contemporaries and posterity, he pronounces on this subject, which he regards as one of the most delicate in his memoirs, that if it was to do again, he would still do it.’