François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XV: The Death of Madame de Beaumont, Rome 1803-1804

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XV: Chapter 1: The year 1803 – Madame de Beaumont’s manuscripts – The letters of Madame de Caud

- Book XV: Chapter 2: Madame de Beaumont’s arrival in Rome – A letter from my sister

- Book XV: Chapter 3: A letter from Madame de Krüdner

- Book XV: Chapter 4: The death of Madame de Beaumont

- Book XV: Chapter 5: The Funeral

- Book XV: Chapter 6: The year 1803: Letters fom Monsieur Chênedollé, Monsieur de Fontanes, Monsieur Necker, and Madame de Staël

- Book XV: Chapter 7: The years 1803 and 1804: The first idea of my Memoirs – I am named Minister of France for the Valais – Departure from Rome

Book XV: Chapter 1: The year 1803 – Madame de Beaumont’s manuscripts – The letters of Madame de Caud

Paris, 1837 (Revised the 22nd February 1845)

BkXV:Chap1:Sec1

When I left France, we were quite blind to Madame de Beaumont’s condition: she wept a great deal, and her will proved that she thought herself doomed. However, her friends, without sharing their fears, sought to reassure each other; they believed in the miraculous spa waters, followed by the effects of Italian sun; they separated and took different routes: their rendezvous was Rome.

Fragments written in Paris, at Mont Dore, and in Rome, by Madame de Beaumont, and found among her papers, show her state of mind.

For several years, my health has worsened in a material way. Symptoms that I took as the signal to depart appeared, without my being prepared yet for departure. My delusions are increasing with the progress of my illness. I have experienced many examples of this singular weakness, and I see that they will do me no good. I have already given myself up to remedies as tedious as they are ineffectual, and, without doubt, I would not have the strength to protect myself from the cruel remedies with which they do not fail to torment those who must die of chest complaints. Like others, I will live in hope; in hope! Do I desire to live, then? My past life has been a series of misfortunes, my present life is full of trouble and agitation; spiritual peace has left me forever. My death would be a momentary sorrow for some, a benefit to others, and the greatest of blessings to me.

This 21st Floréal, the 10th of May, the anniversary of the deaths of my mother and my brother:

‘I shall perish the last, and most miserable!’

Oh, why have I not the courage to die? This illness, that I have had the weakness almost to fear, is arrested, and perhaps I am condemned to live for a long time yet: I feel though that I could die with joy:

‘My days are scarcely worth the cost of a sigh to me.’

No one has more reason than I to rail against nature: in refusing me everything, she has yet given me a feeling for all I lack. There is never a moment when I cease to feel the weight of the total mediocrity to which I am condemned. I know that one’s contentment and happiness are often achieved at the cost of that mediocrity of which I complain so bitterly; but in failing to grant me the gift of self-delusion nature has made a torment of it for me. I resemble a deposed being who cannot forget what she has lost, and has not the strength to regain it. This absolute lack of illusions, and consequently of ambition, creates disaster for me in a thousand ways. I judge myself as someone indifferent to me might judge me and I see my friends as they are. I only have value through my excess of kindness which is not vigorous enough to be appreciated or truly useful, and from which my impatient nature drains all the charm: it makes me sensitive to others’ ills without granting me the means to alleviate them. However, I owe to it the small amount of true pleasure I have experienced in life; I owe to it especially my never having known envy, so common a characteristic of honest mediocrity.’

I intended to reveal some details concerning myself; but weariness made the pen fall from my hand.

Everything painful and bitter in my situation would change to happiness, if I could be sure of quitting this life in a few months time.

If I had the strength to put an end myself to my sorrows in the only way possible, I would not employ it: it would be to act contrary to my intentions, to grant too much recognition to my sufferings, and create too grievous a wound in a soul whom I have judged worthy of supporting me in my ills.

Weeping, I entreat myself to take a path as harsh as it is indispensable. Charlotte Corday claimed that there is no course of action from which one does not derive more pleasure than the pain it has cost to decide upon; but she went off to die, while I may still live a long time. What will become of me? Where shall I hide myself? What grave shall I choose? How shall I prevent hope from penetrating me? What power will block its entry?

To withdraw silently, to let myself be forgotten, to bury myself forever, such is the duty imposed on me and which I hope I have the courage to accomplish. If the cup is too bitter, once laid aside nothing compels me to drain it completely, and perhaps my life will quite simply not last as long as I fear.

If I had decided on my place of retreat, I feel I would be calmer; but my present difficulty adds to the difficulties arising from my weakness, and it would need something of the supernatural to act against it with force, to treat it with sufficient harshness as one would a violent and cruel enemy.’

‘Rome, 28th October.

For ten months, I have not been free of suffering; for six, I have shown all the symptoms of consumption, and some in the last degree: the only things lacking are illusions and perhaps I even have a few of those!’

Monsieur Joubert, frightened of that eagerness for death which tormented Madame de Beaumont, addressed these words to her in his Pensées: ‘Love and respect life, if not for itself, then for your friends at least. In whatever state yours may be, I would always prefer to know you were occupied with stitching than unstitching.’

My sister, Lucile, wrote to Madame de Beaumont, at this time. I possess that correspondence, given into my care by death. Ancient poetry represents some Nereid or other as a flower drifting over an abyss: Lucile was that flower. In comparing her letters with the extracts quoted above, one is struck by the resemblance of spiritual melancholy, expressed in the differing language of these unhappy angels. When I consider that I have shared the society of such spirits, I am astonished I valued it so little. These pages written by two superior women, vanishing from the earth quite closely together, do not meet my gaze without bitterly affecting me:

‘At Lascardais, 30th July

I was so delighted, Madame, to receive a letter from you at last, that I did not have time to enjoy the pleasure of reading it all at once: I broke off my reading to go and tell everyone in the château that I had just received your news, without reflecting that my excitement meant scarcely anything here, and that hardly anyone knew I was corresponding with you. Seeing myself surrounded by cold looks, I returned to my upstairs room, reconciling myself to being joyful alone. I set myself to finishing your letter, and though I have re-read it several times, to tell you the truth, Madame, I cannot comprehend all that it contains. The joy that I continually feel on seeing this letter that I so desired, detracts from the attention I should be giving it.

You are leaving, then, Madame? Once back at Mont Dore, do not go forgetting about your health; give it all your care, I beg you with all the tenderness of my heart. My brother tells me that he hopes to see you in Italy. Fate, like Nature, has been pleased to distinguish him from myself in a favourable way. At least, I will not yield to my brother the happiness of loving you: I will share it with him all my life. Ah, goodness, Madame, how weary and crushed my heart is! You do not know how beneficial your letters are to me, since they inspire me with disdain for my ills! The idea that you think of me, that I interest you, raises my spirits enormously. So write to me, Madame, so that I can maintain that idea, which is so essential to me.

I have not yet seen Monsieur Chênedollé; I desire his visit greatly. I will be able to talk with him about yourself, and Monsieur Joubert; that will be a great pleasure to me. Allow me again, Madame, to recommend your health to you, the poor state of which worries and concerns me endlessly. How can you not be mindful of yourself? You are so kind and dear to all; have the justice to include yourself in your generosity.

Lucile.’

2nd September

What you tell me of your health, Madame, alarms and saddens me; however I reassure myself by thinking of your youth, by considering that, though you are very delicate, you are full of life.

I am distressed that you find yourself in a region that displeases you. I would see you surrounded by those things which are essential to entertain and revive you. I hope that with returning health, you will reconcile yourself to the Auvergne: there is scarcely a place that cannot offer something beautiful to eyes such as yours. I am now living in Rennes: I find my isolation acceptable enough. I change my residence frequently, Madame, as you see; I seem like a displaced being on this earth: indeed, I have long regarded myself as a superfluous creation. I think, Madame, you have spoken of my sorrows and anxieties. At present, it is no longer a question of all that, I am enjoying an inward peace which it is no longer in anyone’s power to disturb. Though I have reached the age I am, having through circumstances and taste lead a mostly solitary life, I knew nothing of the world: at last I achieved that gloomy knowledge. Happily, reflection came to my aid. I asked myself what was so formidable about this world, then, and in what its worth resided, that which in itself could never be, for good or ill, more than an object of pity? Is it not true, Madame, that human judgement is as limited as the rest of our being, as fluid, and as unbelieving as it is ignorant? All this good or faulty reasoning has allowed me to put aside, without difficulty, the strange vestment with which I have been clothed: I find myself full of strength and sincerity; nothing more can trouble me. I work with all my powers to gain control of my life, in order to make it wholly depend upon myself.

Also consider, Madame, that I am not to be pitied too much, since my brother, the better part of me, is in a pleasant situation, and that I still have eyes to admire the beauties of nature, God to support me, and for refuge a heart filled with peace and sweet memories. If you continue to have the goodness, Madame, to write to me, that will prove a vast addition to my happiness.’

The mystery of style, a mystery visible everywhere, and present nowhere; the revelation of a nature painfully blessed; the artlessness of a woman one might have thought in her first youth, and the humble simplicity of a genius unknown to itself, breathes through these letters, a great many of which I have passed over. Did Madame de Sévigné write to Madame de Grignan with a more grateful affection than Madame de Caud did to Madame de Beaumont? Her tenderness had the power to take it upon itself to walk in step with that other. My sister loved my friend with all the passion of the tomb, since she felt she was about to die. Lucile had never ceased to inhabit a spiritual Rochers; she was the daughter of her century and a Sévigné of solitude.

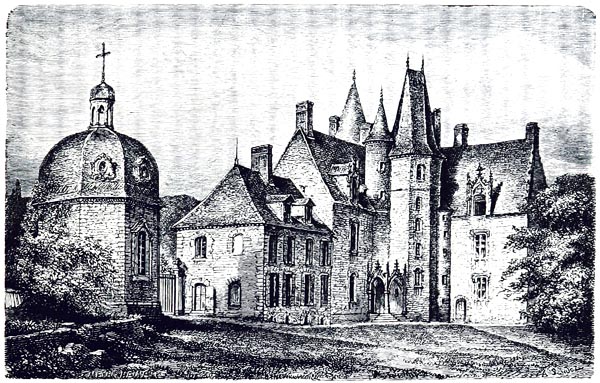

‘Château des Rochers-Sévigné’

La France Pittoresque. Ouvrage Illustré - Jules Gourdault (p85, 1893)

The British Library

Book XV: Chapter 2: Madame de Beaumont’s arrival in Rome – A letter from my sister

Paris, 1837

BkXV:Chap2:Sec1

A letter from Monsieur Ballanche dated the 30th Fructidor (the 17th of September), told me of the pending arrival of Madame de Beaumont, who had travelled from Mont Dore to Lyons on her way to Italy. He told me not to fear the misfortune I dreaded, and that the patient’s health appeared to be improving. Madame de Beaumont, reaching Milan, came upon Monsieur Bertin whom business affairs had summoned there: he had the kindness to take charge of the poor traveller, and escorted her to Florence where I had gone to meet her. I was shocked on seeing her; she had strength enough only to smile. After a few days’ rest, we set out for Rome, travelling at walking pace to avoid jolting her. Madame de Beaumont received careful attention everywhere: this kindly woman attracted interest, so ill and forlorn, the only one left of all her family. The very maids at the inns gave way to gentle commiseration.

What I felt can be imagined: one has conducted friends to the grave, but they were mute, and no shadow of vague hope remained to render one’s grief more poignant. I no longer saw the lovely countryside through which we passed; I had followed La Pérouse’s road: what did Italy signify to me? I still found the climate too fierce, and if the wind blew a little, the breezes seemed like tempests to me.

At Terni, Madame de Beaumont wished to see the falls; after making the effort to lean on my arm, she sat down again, saying: ‘We must let the waters go.’ I had rented a secluded house for her in Rome near the Piazza d’Espagna, at the foot of Monte Pincio; it had a little garden with espalier oranges, and a courtyard with a fig-tree. There I deposited the dying woman. It had been difficult for me to secure this retreat, since there is a prejudice in Rome against diseases of the chest, which are regarded as contagious.

‘View of the Marmore Falls’

Daniël Dupré, 1761 - 1817

The Rijksmuseum

At that period of social renewal, everything appertaining to the old monarchy was sought after: the Pope sent for news of Monsieur de Montmorin’s daughter; Cardinal Consalvi and the members of the Sacred College followed His Holiness’ example; Cardinal Fesch himself showed Madame de Beaumont, till the day of her death, marks of deference and respect which I would not have expected from him, and made me forget the wretched divisions of my first days in Rome. I had written to Monsieur Joubert concerning the anxieties with which I was tormented, before Madame de Beaumont’s arrival: ‘Our friend writes letters to me from Mont Dore,’ I told him, ‘that break my heart: she says that she feels there is no more oil in the lamp; she speaks of the last tremors of her heart. Why have you left her to journey alone? Why have you not written to her? What will become of us if we lose her? Who will console us for her? We do not feel the worth of our friends until the moment when we are threatened with their loss. We are even mad enough when things are going well to imagine that we can distance ourselves from them with impunity: the heavens punish us for it; they remove them from us and we are terrified by the solitude it leaves around us. Pardon me, my dear Joubert; I feel my heart today is only twenty years old; this Italy has rejuvenated me; I love everything that is dear to me with the same force as in my youth. Sorrow is my element: I only find myself again when I am unhappy. My friends are of so rare a species at present, that merely the fear of seeing them taken from me freezes my blood. Forgive my lamentations: I am sure you are as unhappy as I am. Write to me, and write to that other unfortunate Breton too.’

At first, Madame de Beaumont experienced some relief. The patient herself began to believe in her recovery. I had the satisfaction of believing, at least, that Madame de Beaumont would no longer leave me: I counted on taking her to Naples in the spring, and from there, sending in my resignation to the Foreign Minister. Monsieur d’Agincourt, that true philosopher, came to see the fragile bird of passage which had perched in Rome before leaving for an unknown land; Monsieur Boguet, already the most senior of our painters, presented himself. These reinforcements to hope sustained the patient, and soothed her with an illusion which in her heart’s depths she no longer subscribed to. Letters, which were painful to read, arrived for me from all directions, expressing fear and hope. On the 4th of October, Lucile wrote to me from Rennes:

‘I started a letter to you the other day; I have just been searching for it in vain; I spoke to you there of Madame de Beaumont, and I complained of her silence in my regard. My friend, what a strange sad life I lead these many months! Also these words of the prophet revolve endlessly in my mind: ‘The Lord will crown thee with suffering, and hurl thee away like a ball.’ But let us leave my troubles and speak of your worries. I cannot convince myself they are well-founded: I always see Madame de Beaumont as full of life and youth, and almost non-material: nothing gloomy can fill my heart, on that subject. Heaven, which knows our feelings for her, will certainly preserve her. My friend, we will not lose her; I feel that certainty within me. I cheer myself by thinking that, by the time you receive my letter, your anxiety will have passed. Convey to her, for my part, all the true and tender interest I take in her; tell her that the memory of her is one of the loveliest things in life to me. Keep your promise and don’t fail to give me news whenever you can. Ah, what a long space of time must pass before I receive a reply to this letter! How cruel a thing separation is! When will you tell me of your return to France? If you seek to delude me, you wrong me. In the midst of my sorrows, a sweet thought rises in me, that of your friendship and that I exist in your memory such as god has pleased to form me. My friend, I can no longer see any sure refuge for me on earth except your heart; I am a stranger and unknown to all the rest. Farewell, my poor brother! Will I see you again? That idea does not offer itself to me in a distinct enough manner. If you see me again, I fear lest you find me completely insane. Farewell, you to whom I owe so much! Farewell, my unmixed blessing! O memory of my happier days, can you not now lighten my sorrowful days a little?

I am not one of those who exhaust their grief in the moment of separation; each day adds to the sadness I feel due to your absence, and were you a hundred years in Rome, you could not come to the end of that sadness. In order to make the distance seem an illusion, I do not pass a day without reading a few pages of your works: I make every effort to believe I hear you speaking. The friendship I have for you is only natural; from childhood you have been my defender and my friend; all your life you have tried to shed your charm over mine; you have never caused me a tear, and have never made a friend who has not been a friend to me. My kind brother, heaven which has been pleased to toy with all my other joys, wishes me to find my happiness completely in you, and entrust myself to your heart. Send me news quickly of Madame de Beaumont. Address your letters for me to Mademoiselle Lamotte, since I do not know how long I shall be able to stay here. Since our last separation, I am always, in regard to my habitation, as if subject to a quicksand that sinks under my feet: it is surely the case that for those who do not know me, I must appear inexplicable; however I only vary outwardly, since the depths are forever the same.’

The voice of a swan preparing to die was transmitted, through me, to a dying swan: I was the echo of those last ineffable tones!

Book XV: Chapter 3: A letter from Madame de Krüdner

BkXV:Chap3:Sec1

Another, and quite different, letter from the above, but written by a woman who has enjoyed an extraordinary role, Madame de Krüdner, demonstrates the hold that Madame de Beaumont, without any great beauty, fame, power or wealth, exercised over other spirits.

‘Paris, 24th November 1803.

I heard the day before yesterday from Monsieur Michaud, who has returned to Lyons, that Madame de Beaumont was in Rome, and that she was very, very ill: that is what he has said. I am deeply sorry to hear it; my nerves have felt it, and I have thought much of that charming woman, whom I have not known for long, but whom I truly love. How often I have wished for her happiness! How often, I have wished she might cross the Alps and find under Italian skies the sweet and profound emotions I have experienced there myself! Alas! Has she reached so delightful a country only to know sadness there and be exposed to dangers I dread! I do not know how to express to you how much the idea of it troubles me. Forgive me, if I am so absorbed in the matter, that I have not yet spoken of yourself, my dear Chateaubriand; you must know my sincere attachment to you, and in revealing to you the real interest that Madame de Beaumont inspires in me, it is in order to move you more than I would have been able to do by speaking about yourself. I have that sad spectacle before my eyes; I know the secret of grief, and my soul always stops short before those souls on whom nature inflicts the power to suffer more than others. I hoped that Madame de Beaumont might enjoy the gift she received, in being happier; I hoped she might find a modicum of health again given Italian sun and the pleasure of your company. Ah! Reassure me, speak to me; tell her I love her sincerely, that I pray for her. Has she had my letter written in response to hers at Clermont? Address your reply to Michaud: I only ask for a word, since I know, my dear Chateaubriand, how much you feel and suffer. I thought her better; I have not written to her; I was overwhelmed with tasks; but I thought of the pleasure she would gain from seeing you again, and I could imagine it. Tell me a little of how you are; trust in my friendship, in the interest I have avowed towards you always, and do not forget me.

Baronne Krudner.’

Book XV: Chapter 4: The death of Madame de Beaumont

Paris, 1838

BkXV:Chap4:Sec1

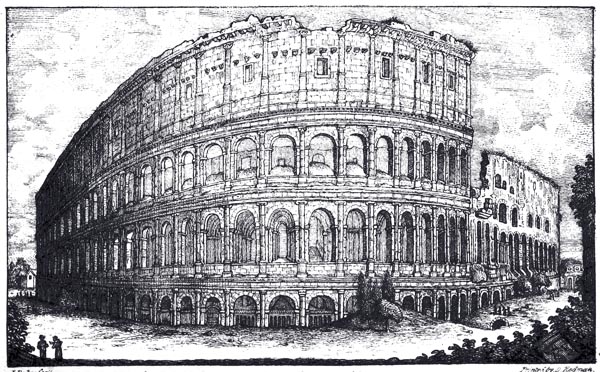

The improvement that the air of Rome had produced in Madame de Beaumont, did not last: the signs of an imminent collapse disappeared, it is true; but it seems that the final moment is always delayed in order to deceive us. On two or three occasions I attempted to take the patient for a drive; I tried hard to distract her, by remarking to her on the countryside and the sky: she no longer took an interest in anything. One day, I took her to the Colosseum; it was on of those October days such as one only sees in Rome. She managed to descend from the carriage, and went to sit on a stone, facing one of the altars placed at the perimeter of the building. She raised her eyes; and gazed slowly at those porticoes, dead themselves for so many years, which had seen so much death; the ruins were thick with briars and with columbines yellowed by autumn and bathed in light. The dying woman then lowered her eyes, little by little, to the arena, leaving the sun behind; she fixed them on the altar cross, and said to me: ‘Let us go; I am cold.’ I took her home; she retired to bed and never rose again.

‘The Colosseum of Rome’

Voyages and Travels of Her Majesty, Caroline Queen of Great Britain - Louise Demont (p226, 1821)

The British Library

I was put in communication with the Comte de La Luzerne; I sent him from Rome, by each courier, a report on the health of his sister-in-law. When his uncle had been charged by Louis XVI with the diplomatic mission to London, he had taken my brother with him: André Chenier took part in that embassy.

The doctors whom I had gathered together again after our attempt to enjoy a drive, told me that a miracle alone could save Madame de Beaumont. She was taken with the idea that she would not survive the 2nd of November, All Souls’ Day; then she remembered that one of her relatives, I do not know which, had died on the 4th of November. I told her that her imagination was disturbed; that she would discover the idleness of her fears; she replied, to console me: ‘Oh! Yes, I shall live longer!’ She saw a few tears that I tried to conceal from her; she took my hand, and said: ‘You are a child; were you not expecting this?’

On the eve of her death, Thursday the 3rd of November, she seemed calmer. She spoke to me about the disposal of her fortune, and told me, in speaking of her will, that everything was settled; but everything was yet to be done, and that she would have liked just two hours to see to it. That evening, the doctor advised me that he felt obliged to warn the patient that it was time for her to think of setting her conscience in order: I had an instant of weakness; the fear of shortening, through a preparation for death, the few moments that Madame Beaumont still had to live, horrified me. I was angry with the doctor then begged him to at least wait until the following day.

My night was a cruel one, with the secret I held in my breast. The patient did not allow me to spend it in her room. I stayed outside, trembling at every noise I heard: when the door was opened a little, I saw the feeble glimmer of a dying light.

On Friday the 4th of November, I entered, followed by the doctor. Madame de Beaumont saw my agitation, and said: ‘Why do you look like that? I have passed a good night.’ The doctor then affected to tell me out loud that he wished to see me in the adjoining room. I went out: when I returned, I no longer knew if I existed. Madame de Beaumont asked me what the doctor had wanted me for. I flung myself down by her bed, dissolved in tears. She did not speak for a moment, looked at me, and said in a firm voice, as if she wanted to give me strength: ‘I did not think that it would happen quite so quickly as this: go, I must say goodbye to you for a moment. Call the Abbé de Bonnevie.’

The Abbé de Bonnevie, having obtained the relevant authority, came to Madame de Beaumont’s house. She told him she had always possessed a profound religious sentiment at heart; but that the unheard-of misfortunes that had struck her during the Revolution had sometimes made her doubt the justice of Providence; that she was ready to admit her errors and commend herself to the eternal mercy; that she hoped the ills she had suffered in this life would shorten her expiation in the next. She made me a sign to retire, and remained alone with her confessor.

I saw him come out an hour afterwards, wiping his eyes, and saying that he had never heard such beautiful language, nor seen such heroism. They sent for the parish priest, to administer the Sacraments. I returned to Madame de Beaumont. On seeing me, she said: ‘Well! Are you pleased with me?’ She was moved by what she deigned to call my kindness to her: ah, if at that moment I could have bought back one of her days by sacrificing all of mine, with what joy I would have done so! Madame de Beaumont’s other friends, who were not present at this scene, at least only had to weep once: while, at the head of that bed of pain where a man hears his last hour strike, each of the dying woman’s smiles gave me life and stole it from me as it faded. A terrible idea overwhelmed me: I realised that Madame de Beaumont had been unsure to this very last breath of the true affection I had for her: she did not cease from showing her surprise and seemed to be dying in both despair and delight. She had considered herself a burden on me, and had wished to depart to set me free.

The priest arrived at eleven: the room filled with that crowd of the curious and the idle that one cannot prevent from following a priest in Rome. Madame de Beaumont watched the formidable solemnity without the least sign of fear. We knelt, and the dying woman received both Communion and the Extreme Unction. When everyone had gone, she made me sit on the edge of her bed and talked to me for half an hour about my work and my plans with the greatest nobility of spirit and the most touching friendship; she urged me above all to be close to Madame de Chateaubriand and Monsieur Joubert; but would Monsieur Joubert go on living?

She begged me to open the window, because she felt stifled. A ray of sunlight lit her bed and seemed to re-kindle her. Then she reminded me of her idea of retiring to the countryside, which we had sometimes talked of together, and she began to cry.

Between two and three in the afternoon, Madame de Beaumont, asked Madame Saint-Germain, an old Spanish lady’s-maid who served her with affection worthy of so good a mistress, to move her to another bed: the doctor opposed this for fear that Madame de Beaumont might die during the transfer. Then she told me she felt the approach of the death-pang. Suddenly, she flung back the coverlet, held out her hand to me, and pressed mine convulsively; her gaze wandering from side to side. With her free hand, she made signs to someone she saw at the foot of the bed; then, returning her hand to her breast she said: ‘It is there!’ Dismayed, I asked her if she recognised me: the ghost of a smile appeared amidst her distraction; she gave me a little nod of the head; her speech was no longer with this world. The convulsions lasted only a few minutes. We supported her in our arms, the doctor, the nurse, and I: one of my hands rested on her heart which throbbed against her fragile bones; it beat rapidly like a clock unwinding, its chain broken. Oh, moment of horror and fear, I felt it stop! We laid on her pillow the woman who had found peace; her head drooped. A few locks of her hair, unwound, fell over her brow; her eyes were closed, eternal night had descended. The doctor held a mirror and a candle to the mouth of the traveller; the mirror was not clouded by a breath of life and the candle remained unmoving. All was over.

‘Dante's Dream at the Time of the Death of Beatrice’

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882)

Book XV: Chapter 5: The Funeral

BkXV:Chap5:Sec1

Ordinarily, those who weep can indulge their tears in peace, others being charged with attending to the requirements of religion: as the representative of France, on behalf of the Cardinal and Minister who was then absent; and as the sole friend of Monsieur de Montmorin’s daughter, and responsible to her family, I was obliged to see to everything: I had to select the place of burial, arrange the size and depth of the grave, order the shroud, and give the carpenter the dimensions of the coffin.

Two monks watched by this coffin, which was to be carried to San Luigi dei Francesi. One of these fathers was from the Auvergne and a native of Montmorin itself. Madame de Beaumont had requested to be buried in a piece of cloth that her brother Auguste, who alone had not died on the scaffold, had sent her from Mauritius. This cloth was not in Rome; we could only find a fragment of it which she carried everywhere. Madame Saint-Germain fastened this strip around the body with a cornelian locket containing a piece of Monsieur de Montmorin’s hair. The French ecclesiastics were invited; Princess Borghèse lent her family hearse; Cardinal Fesch had left orders, in the event of the only too predictable occurrence, to send his livery and his carriages. On Saturday the 5th of November at seven in the evening, by torchlight in the midst of a large crowd, Madame de Beamont passed along the road by which we all must pass. On Sunday the 6th of November, the Funeral Mass was celebrated. The event would have been less French in Paris than it was at Rome. That religious architecture, which bears among its ornamentation the arms and inscriptions of our ancient land; those tombs on which the names of some of the most historic families of our annals are carved; that church, under the protection of a great saint, a great king, and a great man, all that gave no consolation, but it gave honour to misfortune. I wished the last offshoot of a once high family to find some support, at least, in my obscure attachment, and the friendship not be lacking like the fortune.

‘Funeral coach’

Abel Faivre, 1867 - 1945

Images from the History of Medicine - US National Library of Medicine

The people of Rome, accustomed to foreigners, treat them as brothers and sisters. Madame de Beaumont has left on that soil, hospitable to the dead, a pious memory; they still remember her: I have seen Leo XII pray at her tomb. In 1828, I visited the monument of her who was the soul of a vanished society; the sound of my footsteps around that mute monument, in a solitary church, was a warning to me. ‘I shall love you always,’ says the Greek epitaph, ‘but you, among the dead, drink not, I beg you, of that cup which brings forgetfulness of former friends.’

Book XV: Chapter 6: The year 1803: Letters fom Monsieur Chênedollé, Monsieur de Fontanes, Monsieur Necker, and Madame de Staël

Paris, 1838

BkXV:Chap6:Sec1

If one considers on the scale of public events the calamities of private life, those calamities ought scarcely to occupy a word in a set of Memoirs. Who has not lost a friend? Who has not seen one die? Who has not had to recall a similar scene of mourning? The reflection is just, however none of us are cured of retelling our own adventures; on the ship that carries them, the sailors are like a family ashore, who are of interest to and mutually support each other. Every man encloses within himself a world apart, a stranger to the laws and common fate of the centuries. It is, moreover, an error to believe that revolutions, celebrated events, and resounding catastrophes, are the only splendours unique to our nature: one by one we all labour at the links of common history and the mortal universe is in God’s eyes formed of all those individual existences.

In gathering together these regrets around Madame de Beaumont’s ashes, I only seek to lay on her grave the wreaths destined for it.

‘A Letter From Monsieur Chênedollé

You cannot doubt, my dear unfortunate friend, how much I share in your affliction. My grief is not as great as yours, since that is impossible; but I am most profoundly affected by this loss, and it comes to darken yet further this life, which for a long time has been no more than a burden to me. So passes then and effaces itself from earth all that is good, kind and sensitive. My poor friend, hasten to return to France; come and seek solace with your old friend. You know how I love you: do come.

I was full of the greatest anxiety about you; I have not received news of you for more than three months, and three letters of mine remain without reply. Did you receive them? Madame de Caud suddenly stopped writing to me, two months ago. It has caused me mortal pain, and yet I am not aware of having done any wrong to her with which I could reproach myself. But whatever she may do, it cannot affect the lifetime’s tender friendship and respect I have vowed for her. Fontanes and Joubert have also stopped writing to me; so, all those I love seem to be united together in forgetting me. Do not forget me, oh you, my kind friend, that in this world of tears one heart yet might remain on which I might count! Farewell! I embrace you, while weeping. Be certain, my kind friend, that I feel your loss as one must feel it.

23rd November, 1803.’

‘A Letter From Monsieur De Fontanes

I share all your regrets, my dear friend: I feel the sadness of your circumstances. To die so young and after surviving all her family! But, at least, that fascinating and unfortunate woman did not lack the aid and tokens of friendship. Her memory will live in hearts worthy of her. I have passed to Monsieur de La Luzerne the touching description destined for him. Old Saint-Germain, your friend’s manservant, was charged with bringing it. That good servant has made me weep by speaking about his mistress. I have told him that he has been left a legacy of ten thousand francs; but he was not interested in it for a moment. If it were possible to talk of business in such dismal circumstances, I would tell you that it was quite natural to leave you at least the usufruct of a property which is to act as remote and almost unknown collateral.’ (Monsieur de Fontanes’ friendship goes far too far; Madame de Beaumont judged me better; she knew without doubt that if she left me her fortune, I would not accept it.) ‘I approve of your conduct; I know your delicacy; but I cannot show the same disinterestedness towards my friend as he shows towards himself. I swear that such self-forgetfulness astonishes and pains me. Madame de Beaumont on her death-bed spoke to you, with the eloquence of parting words, of the future and your destiny. Her voice must have greater force than mine. But did she counsel you to renounce eight to twelve thousand francs of your appointment monies when your path was being cleared of its first thorns? Can you be rushing into an even more important step, my dear friend? You cannot doubt the great pleasure I would have in seeing you again. If I consulted only my own happiness, I would say to you: Come at once. But your interests are as dear to me as mine, and I fail to see resources imminent enough to compensate you for advantages which you relinquish voluntarily. I know that your talent, name and efforts will never leave you at the mercy of your fundamental needs; but I see more of glory than of wealth in them. Your education and your habits demand a modicum of expenditure. Fame alone is not sufficient for life’s wants and that wretched art of beef and two vegetables comes before all others if you wish to live in tranquillity and independence. I keep hoping that nothing will persuade you to seek your fortune among foreigners. Ah, my friend, you can be sure that after the first welcome they will still prove to be worth less than your compatriots. If your dying friend had considered all this, her last moments would have been troubled a little by them; but I trust that at the foot of her grave you will find counsel and superior insight in all that your remaining friends can grant you. That kindly woman loved you: she will advise you well. Her memory and your heart will guide you surely: I am no longer anxious if you listen to both. Farewell, my dear friend, I embrace you tenderly.’

Monsieur Necker wrote me the only letter I ever received from him. I had been a witness to the joy at Court on the dismissal of this Minister, whose honest opinions contributed to the overthrow of the monarchy. He had been a colleague of Monsieur de Montmorin. Monsieur Necker was soon to die in the place from which his letter is dated: lacking Madame de Staël by his side, he himself found a few tears for his daughter’s friend:

‘A Letter From Monsieur Necker

My daughter, Sir, on setting out for Germany begged me to open any large packets which might be addressed to her, in order to decide it if was worth the trouble of sending them on to her by post: that is the reason that I am advised, before she is, of Madame de Beaumont’s death. I have sent your letter on to Frankfurt, Sir, from where it will probably be transmitted further, perhaps to Weimar or Berlin. Do not be surprised then, Sir, if you do not receive Madame de Staël’s reply as rapidly as you have right to expect. You may indeed be sure, Sir, of the grief Madame de Staël will experience in learning of the loss of a friend of whom I have always heard her speak with profound sentiment. I associate myself with her pain, I associate myself with yours, Sir, and I share a part of it myself especially, when I think of the unfortunate fate of my friend Monsieur de Montmorin’s whole family.

I see that you are on the verge of quitting Rome, Sir, in order to return to France; I hope you will make your way via Geneva, where I will be spending the winter. I would be very willing to do you the honours of a town where you are already known by reputation. But where are you not so, Sir? Your last work, sparkling with incomparable beauties, is in the hands of all those who love to read.

I have the honour to present you, Sir, with assurances and the homage of my most distinguished feelings.

Necker.

Coppet, 27th November 1803.’

‘A Letter From Madame De Staël

Frankfurt, 3rd December 1803.

Oh, my dear Francis, what sorrow seized me on receiving your letter! Already yesterday, this dreadful news sprung at me from the newspaper, and your heart-rending description will be engraved on my heart forever in letters of blood. How can you speak to me, how can you, of differing opinions on religion, and priests? Are there two opinions where there is only one sentiment? I could not read your description except through the saddest of tears. My dear Francis, recall the time when you felt greater friendship for me; do not forget that period especially when my whole heart was attracted towards you, and tell yourself that those feelings, more tender, deeper than ever for you, exist in the depths of my soul. I loved; I admired Madame de Beaumont’s character: I have never known anyone more generous, more grateful; more passionately sensitive. Ever since I entered society, I have not ceased to communicate with her, and I always felt that even in the midst of our differences I was bound to her by every tie. My dear Francis, keep a place for me in your life. I admire you, I love you; I loved her whom you regret. I am a devoted friend; I will be a sister to you. More than ever, I must give way to your opinions: Mathieu who shares them, has been an angel to me in the last trouble I experienced. Give me a new reason to consider them; allow me to be useful or kind to you in some way. Have they written to tell you that I have been exiled forty leagues from Paris? I have taken the opportunity to make a tour of Germany; but, in the spring, I will return, to Paris itself if my exile is revoked, or close to Paris, or Geneva. Let us be reunited somehow or other. Do you not feel that my spirit and soul understand yours, and do you not sense how we resemble one another, despite the differences? Monsieur de Humboldt wrote a letter to me, a few days ago, in which he spoke of your work with a degree of admiration that must flatter you coming from a man of his worth and opinions. But what am I doing speaking to you of your success at such a moment? Yet, she loved that success; she attached her glory to it. Continue to render illustrious that which she loved so. Farewell, my dear François, I will write to you from Weimar in Saxony. Reply to me, at Messieurs Desport, my bankers. What heart-rending words there are in your description! And that commitment to look after poor Saint-Germain; you shall bring him to my house sometime.

Farewell, tenderly: sorrowfully farewell.

N. De Staël.’

This prompt letter, swift in its affection, written by an illustrious woman, redoubled my emotion. Madame de Beaumont would have been happy at that moment, if heaven had allowed her to be re-born! But our attachments, which gain us a hearing among the dead, lack the power to free them: when Lazarus rose from the grave, his hands and feet were tied with bandages and his face covered by a shroud: now, friendship can only say, as Christ did to Martha and Mary: ‘Loose him, and let him go.’

Those who consoled me are also gone, and they ask of me the regrets for themselves that they showed for another.

Book XV: Chapter 7: The years 1803 and 1804: The first idea of my Memoirs – I am named Minister of France for the Valais – Departure from Rome

Paris, 1838

BkXV:Chap7:Sec1

I was determined to quit that diplomatic career where human tragedy had become blended with mediocrity of effort and vile political worries. No one knows what desolation of spirit is, unless they have been left alone to wander among places once inhabited by someone who adorned their life: you seek for her and find her not; she speaks to you, you smile, you are with her; everything she has moved or touched conjures her image; there is only a transparent veil between you, yet so heavy you cannot lift it. The memory of the first friend whom you have left behind on the way is cruel; for, if your days are prolonged, you will necessarily have other losses: those dead who follow attach themselves to the first, and you will grieve together in the one person for all those you have successively lost.

While I was setting in train lengthy arrangements in far-off France, I remained alone in the ruins of Rome. On my first outing, the aspects seemed changed, I failed to recognise the trees, monuments, and sky; I wandered through the Campagne, along the arches of the aqueducts, as I once did beneath the arbours of the New World. I returned to the eternal City, which had now added one more extinguished life to so many lost existences. By dint of travelling the solitudes of the Tiber, they were so deeply engraved on my memory, that I reproduced them correctly enough in my letter to Monsieur de Fontanes: ‘If a traveller is unhappy,’ I said, ‘if he has mingled the ashes of a loved one with the ashes of the famous, with what charm will he not pass from Cecilia Metella’s tomb to the grave of an unfortunate woman!’

It was in Rome too, that I had the first idea of writing the Mémoires de ma vie; I find here a few lines written at hazard, in which I can decipher these few words: ‘Having wandered the earth, and spent the best years of my youth far from my country, and suffered more or less all that a man can suffer, including hunger, I returned to Paris in 1800.’

In a letter to Monsieur Joubert, I sketched out my plan thus:

‘My sole happiness is to snatch a few hours and occupy myself with a work which alone can ease my suffering: namely the Mémoires de ma vie. Rome will appear in them: It is only in that way that I can speak of Rome in future. Don’t worry; they will not be confessions that will pain my friends: if I achieve anything in future, my friends will be there with names as fine as they are respectable. No more shall I reveal to posterity the details of my frailties; I will only say those things about myself that suit my dignity as a human being, and, I dare say, the nobility of my heart. One must reveal to the world only what is beautiful; it is not a deception before God to only show whatever of one’s life can inspire noble and generous feelings in our fellow men. It is not that, ultimately, I have anything to hide; I have not driven a serving girl away because of a stolen ribbon, nor abandoned my friend dying in the street, nor dishonoured the woman who welcomed me, nor placed my bastard offspring in the Foundlings Hospital, but I have my frailties, my despondencies of heart; one groan of mine is enough to comprehend the common miseries of the world, fitted to remain behind the veil. What does society gain by reproducing those wounds we see everywhere? There is no lack of examples if one wishes to triumph over poor human nature.’

In the plan that I sketched out, I passed over my family, my childhood, my youth, my travels and my exile: yet those are the passages where I am perhaps shown to most advantage.

I lived like a cheerful slave: accustomed to setting chains on his freedom, he has no idea what to do with his leisure, when his chains are broken. When I wanted to give myself up to work, a face would appear before me, and I could not turn my eyes away: only religion gained my attention through its seriousness and the thoughts of a superior nature that it suggested to me.

Still, in occupying myself with the idea of writing my Memoirs, I felt the value that the ancients attached to the importance of their name; perhaps there is a touching reality in perpetuating memories that one might let go as they pass. Perhaps, for the great men of antiquity, that idea of an immortal existence amidst the human race took the place for them of that immortality of the soul which remained a problem to them. If fame is nothing much as it appertains to our selves, it must nevertheless be admitted that it is a fine privilege, deriving from the friendship of genius, to grant imperishable existence to all it has loved.

I began a commentary on several books of the Bible beginning with Genesis. On the verses: And the Lord God said, behold the man is become as one of us, to know good and evil, and now, lest he put forth his hand, and take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live for ever; I remarked on the Creator’s great irony: Behold the man is become as one of us, etc. Lest he put forth his hand and take also of the tree of life. Why? Because he has now tasted the fruit of science and knows goodness from evil; he is now overwhelmed with troubles; so, he shall not live for ever: what a kindness of God is death!

Prayers commenced, some for inquietude of soul, others to fortify against the prosperity of the spiteful: I tried to call back my thoughts, wandering far from me, to a centre of repose.

Since God did not intend my life to end there, reserving it for lengthy trials, the storms that had arisen calmed once more. Suddenly the Cardinal, and Ambassador, altered his manner towards me: I had a discussion with him, and declared to him my decision to withdraw from office. He opposed it: he claimed that my resignation, at that time, would carry a suggestion of disgrace; that I would give pleasure to my enemies, and the First Consul would be angered, which would prevent me from enjoying my place of retirement in tranquillity. He suggested I go and spend a fortnight, or even a month, at Naples.

At this very moment, the Russians sounded me out as to whether I would accept the position of Governorship of a Grand-Duchy; it might have been just as good as choosing to sacrifice the remainder of my life to the cause of Henri V.

BkXV:Chap7:Sec2

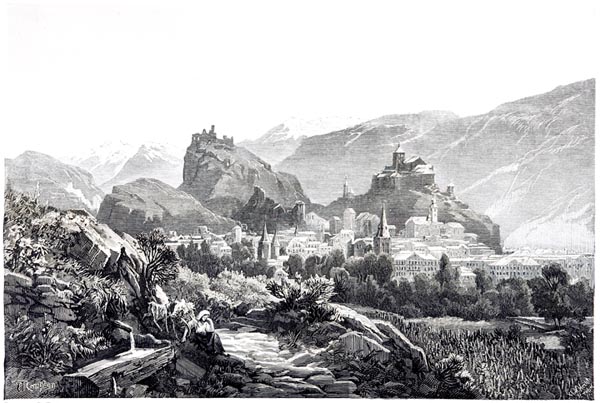

While I hovered between a thousand courses of action, I received the news that the First Consul had nominated me as Minister to the Valais. Initially he was angered by those denunciations of me; but he regained his temper and understood that I was of that race which is useless unless it is in the foreground, that it was no use subordinating me to others, or it would be better to have no dealings with me at all. There were no places vacant; he created one, and selecting it as suitable for my instinct for solitude and independence, he set me down in the Alps; he gave me a Catholic republic with a wealth of mountain streams; the Rhône and our soldiers met at my feet, the former descending towards France, the latter climbing towards Italy, the Simplon opened its daring path before me. The Consul granted me as much time as I would have wished to travel in Italy, and Madame Bacciochi let me know via Fontanes that the first significant Embassy available was reserved for me. I therefore obtained this first diplomatic triumph without expecting or wishing it: it is true that there was a fine intellect acting as Head of State, which did not wish to abandon to office intrigue another intellect, which it felt was all too disposed to separate itself from the power nexus.

‘Sion, Chief Town of Canton Valais’

Switzerland: its Scenery and People - Theodor Gsell-Fels (p117, 1881)

The British Library

That comment is even truer in that Cardinal Fesch, to whom I grant in my Memoirs a justice he might not have expected, had sent two malevolent dispatches to Paris, almost at the very moment when his manner to me had become most obliging after the death of Madame de Beaumont. Was his true opinion reflected in his conversations, during which he agreed to my going to Naples, or in his diplomatic missives? The conversations and missives were of the same date, and contradictory. It was entirely within my hands to remedy Monsieur le Cardinal’s inconsistency, by erasing all trace of the reports concerning myself: it would have been sufficient to remove the Ambassador’s ranting from the files, while I was Minister for Foreign Affairs: I would only have been doing what Monsieur de Talleyrand used to do with regard to his correspondence with the Emperor. I did not consider I had the right to use my power for my own benefit. If anyone chances to look for those documents again, they will be found in their proper place. That this manner of acting would have been duplicitous, I well knew; but in order not to credit me with the merit of a virtue I did not show, one should understand that this respect for my detractors’ correspondence owed more to contempt than to generosity. In the Embassy archive in Berlin I found offensive letters from Monsieur le Marquis de Bonnay concerning myself, as well: far from letting them lie, I made them known.

Monsieur le Cardinal Fesch was no more reserved about poor Abbé Guillon (the Bishop of Maroc): he was marked down as a Russian agent. Bonaparte considered Monsieur Lainé an agent of England: it was in that way, from such gossip, that the great man acquired the unpleasant habit of initiating police reports. But was nothing said about Monsieur Fesch himself? What did his own family make of him? The Cardinal de Clermont-Tonnerre was in Rome, as I was, in 1803; what did he not say concerning Napoleon’s uncle! I have the letters.

As for the rest, to whom then do these things matter, buried as they have been for forty years in worm-eaten files? Only one of the actors remains from that époque, Bonaparte. All we who pretend to live are already dead: who reads an insect’s name in the feeble light that it sometimes sheds behind it in its crawling?

Monsieur le Cardinal Fesch has met me since, as ambassador to Leo XII; he gave me proofs of his esteem: for my part, I determined to avoid him and respect him. It is natural moreover that I should have been judged with a severity that I never spare myself. It is all past and done: I would not even recognise the writing of those who, in 1803, served as official or unofficial secretaries to Monsieur le Cardinal Fesch.

BkXV:Chap7:Sec3

I left for Naples: there I began a year without Madame de Beaumont; a year of her absence, to be followed by so many others! I have never returned to Naples since that time (except for 1828, when I was at the gates of that same city, which I promised to visit with Madame de Chateaubriand). The orange trees were heavy with fruit, and the myrtles covered with flowers. Baiae, the Elysian Fields, and the sea, were enchantments that I could no longer tell anyone of. I have described the Bay of Naples in Les Martyrs. I climbed Vesuvius and descended into its crater. I plagiarised myself: I was acting out a scene from René.

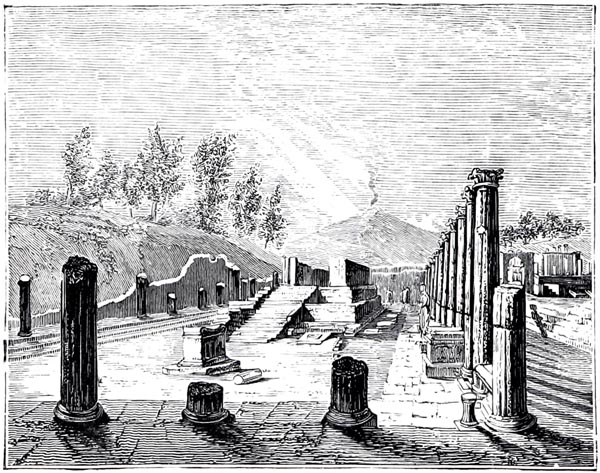

At Pompeii, they showed me a skeleton in chains, and ill-formed Latin words, daubed on the walls by soldiers. I returned to Rome. Canova granted me entry to his studio, while he was working on the statue of a nymph. Elsewhere the marble tomb figures which I had ordered were already full of expression. I had been to pray over the ashes from the bed of Saint Louis, and left for Paris on the 21st of January 1804, another inauspicious day.

‘A Temple at Pompeii’

South by East. Notes of travel in Southern Europe - George Farrer Rodwell (p184, 1877)

The British Library

Behold a prodigious sorrow: thirty five years have passed since the date of those events. Did my grief flatter itself, in those distant days, that the tie which had been broken would be my last tie? And yet how quickly I have, not forgotten, but replaced what was dear to me! So a man passes from frailty to frailty. While he is young and his life is before him he has the shadow of an excuse; but when he is yoked to it and dragging it painfully behind him how can he be excused? The poverty of our nature is so great, that in our weakness and fickleness, we can only employ the words we have already used in our former relationships to expression our most recent affections. They are words however that should only serve us once: one profanes them by repeating them. Friendships deserted and betrayed reproach us for the new associations we engage in; our days accuse one another: our life is a perpetual blush of shame, because it is an ongoing error.

End of Book XV