François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXIII: Napoleon - The Hundred Days: 1815

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXIII: Chapter 1: The Commencement of The Hundred Days – The return from Elba

- Book XXIII: Chapter 2: The Legitimacy in a state of torpor – Benjamin Constant’s article – Marshal Soult’s order of the day – A Royal session – The Petition of the Law School to the Chamber of Deputies

- Book XXIII: Chapter 3: A plan for the defence of Paris

- Book XXIII: Chapter 4: The flight of the King – I leave with Madame de Chateaubriand – Problems on the way – The Duc d’Orléans and the Prince de Condé – Tournai, Brussels – Memories – The Duc de Richelieu – The King halts at Ghent and summons me

- Book XXIII: Chapter 5: THE HUNDRED DAYS IN GHENT – The King and his council – I become interim Minister of the Interieur – Monsieur de Lallay-Tollendal – Madame the Duchesse de Duras – Marshal Victor– The Abbé Louis and Comte Beugnot – The Abbé Montesquiou – Dining on white fish: guests

- Book XXIII: Chapter 6: THE HUNDRED DAYS IN GHENT, CONTINUED – The Ghent Moniteur – My report to the King: the effect of that report in Paris – Falsification

- Book XXIII: Chapter 7: THE HUNDRED DAYS IN GHENT, CONTINUED – The Beguinage – How I was received – A grand dinner – Madame de Chateaubriand’s trip to Ostend – My life’s echoes – Anvers – A Stammerer– Death of a young English girl

- Book XXIII: Chapter 8: THE HUNDRED DAYS IN GHENT, CONTINUED – Unusual activity at Ghent – The Duke of Wellington – Monsieur – Louis XVIII

- Book XXIII: Chapter 9: THE HUNDRED DAYS IN GHENT, CONTINUED – Historical memories in Ghent – Madame the Duchesse d’Angouleme arrives in Ghent – Monsieur de Sèze – Madame the Duchesse de Lévis

- Book XXIII: Chapter 10: THE HUNDRED DAYS IN GHENT, CONTINUED – The Pavillon Marsan’s equivalent at Ghent – Monsieur Gaillard, Councillor to the Royal Court – A secret visit by Madame la Baronne de Vitrolles – A note from Monsieur – Fouché

- Book XXIII: Chapter 11: EVENTS IN VIENNA – Negotiations by Monsieur de Saint-Léon, Fouché’s envoy – A proposal regarding Monsieur the Duc d’Orléans – Monsieur de Talleyrand – Alexander’s discontent with Louis XVIII – Various claims – La Besnardières’ report – An unexpected proposal to the Congress from Alexander: Lord Clancarthy causes it to fail – Monsieur de Talleyrand returns: his dispatch to Louis XVIII – The Declaration of Alliance, in truncated form in the official Frankfurt newspaper – Monsieur de Talleyrand wishes the King to return to France via the south-east provinces – Various visits to Vienna by the Prince of Benevento – he writes to me at Ghent: his letter

- Book XXIII: Chapter 12: THE HUNDRED DAYS IN PARIS – The effect of the Legitimacy’s departure from France – Bonaparte’s astonishment – He is forced to capitulate to ideas he thought moribund – His new system – Three mighty players left – Liberal illusions – Clubs and Federations – Conjuring away the Republic: the Supplementary Act – The Chamber of Representatives convened – The futile Champ-De-Mai

- Book XXIII: Chapter 13: THE HUNDRED DAYS IN PARIS, CONTINUED – Bonaparte’s anxiety and bitterness

- Book XXIII: Chapter 14: A Resolution in Vienna – Action in Paris

- Book XXIII: Chapter 15: What was going on in Ghent – Monsieur de Blacas

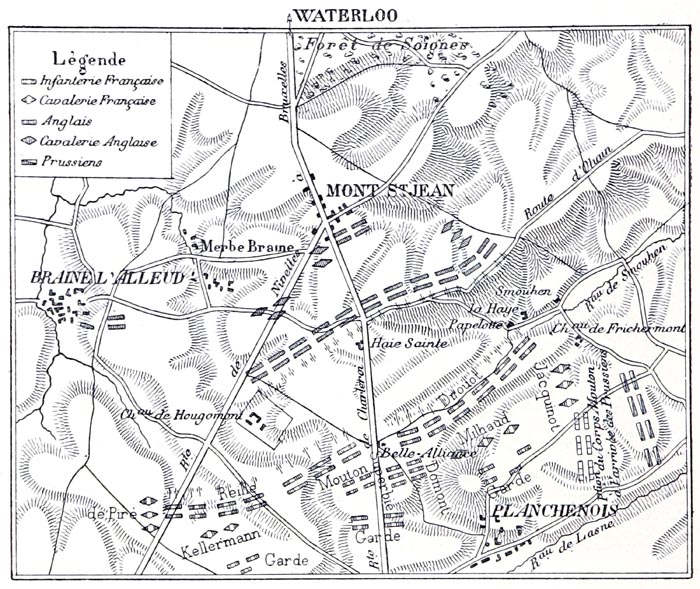

- Book XXIII: Chapter 16: The Battle of Waterloo

- Book XXIII: Chapter 17: Confusion in Ghent – The reality of Waterloo

- Book XXIII: Chapter 18: Return of the Emperor – Re-appearance of Lafayette – Bonaparte’s fresh abdication – Stormy sessions of the Chamber of Peers - Threatening omens for the Second Restoration

- Book XXIII: Chapter 19: Departure from Ghent – Arrival at Mons – I lose the first chance of success in my political career – Monsieur de Talleyrand at Mons – A scene with the King – Stupidly, I show an interest in Monsieur de Talleyrand

- Book XXIII: Chapter 20: From Mons to Gonesse – With Monsieur le Comte Beugnot I oppose Fouché’s nomination as a Minister: my reasons – The Duke of Wellington gains the upper hand – Arnouville – Saint-Denis – A last conversation with the King

Book XXIII: Chapter 1: The Commencement of The Hundred Days – The return from Elba

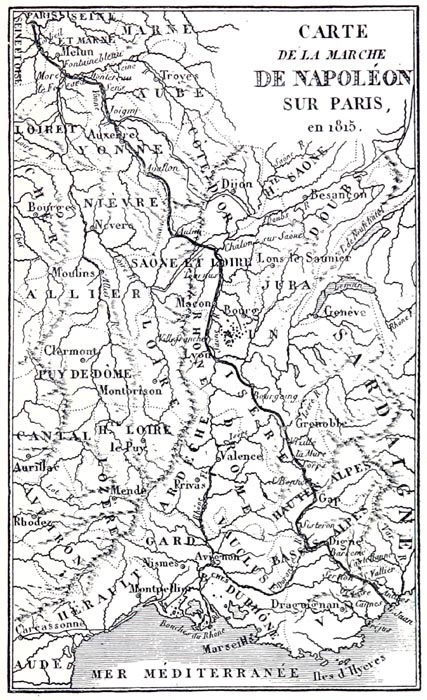

‘Carte Indiquant la Marche de Napoléon sur Paris en 1815’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p927, 1888)

The British Library

BkXXIII:Chap1:Sec1

Suddenly the telegraph announced to the soldiers and an incredulous world that the man had disembarked: Monsieur hastened to Lyons with the Duc d’Orléans and Marshal Macdonald; he quickly returned. Marshal Soult, denounced in the Chamber of Deputies, surrendered his office on the 11th of March to the Duc de Feltre. Bonaparte found the general facing him, as Minister of War under Louis XVIII in 1815, who had acted as his last Minister of War in 1814.

The boldness of the enterprise was incredible. From the political viewpoint, it can be regarded as Napoleon’s unpardonable crime and his capital error. He knew that the Princes, still gathered at the Congress, and Europe still under arms, would not permit his return to power; his judgement should have warned him that success, if he obtained it, could not last more than a moment: to his longing to reappear on the world’s stage, he was sacrificing the peace of a nation which had lavished on him its blood and wealth; he was exposing to dismemberment that country from which he had derived everything he had been in the past, and all he might be in the future. In this fantastic undertaking there was a ferocious egoism, and a terrible lack of gratitude and generosity towards France.

All this is true according to practical reason, for a man of heart rather than brain; but for beings of Napoleon’s sort, another kind of reason exists; those creatures of great renown have a way of their own: comets describe tracks which escape precise calculation; they are tied to nothing and seem purposeless; if a sphere appears in their path, they shatter it and vanish into the abyss of the sky; their tracks are known to God alone. Extraordinary individuals are monuments to human intellect; they are not its rule.

Bonaparte, then, was persuaded to his enterprise by the false reports of his friends, rather than his genius being driven to it by necessity: he took up the cross by virtue of the faith within him. For a great man, being born is not everything: he must also die. Was exile on Elba a fitting end for Napoleon? Could he accept the sovereignty of a villa, like Tiberius on Capri, or of a cabbage-patch, like Diocletian at Salona? Would he have had greater chance of success if he had waited until his memory aroused less emotion, his soldiers had left the army, and new social attitudes had been adopted?

Well, he took the world head-on! And, at the beginning, must have believed he had not deceived himself as to the extent of his power.

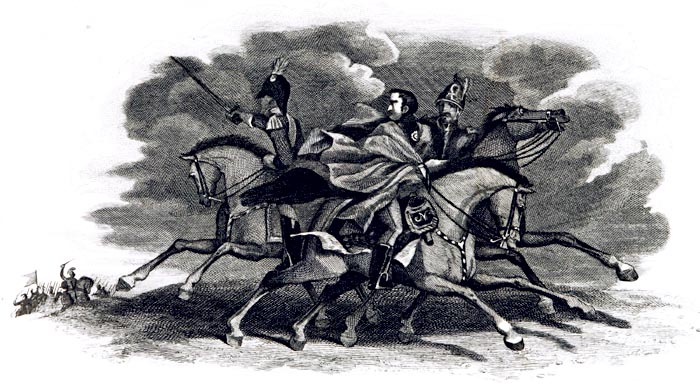

On the night of the 25th and 26th of February 1815, at the end of a ball at which the Princess Borghèse did the honours, he escaped with success, long his comrade and accomplice; he crossed a sea covered with our ships, meeting two frigates, a vessel of seventy-four guns and the brig Zephyr, which stopped him and interrogated him; he replied to the captain’s questions himself; the sea and the waves saluted him and he pursued his course. The deck of the Inconstant, his little brig, served him as a study and an exercise-yard; he dictated amongst the breezes, and had copies made, on that table, of three proclamations to the army and France; a few feluccas, carrying his companions in fortune, accompanied his flagship, flying a white flag sprinkled with stars. On the 1st of March, at three in the morning, he landed on the coast of France, between Cannes and Antibes, at Golfe-Juan: he landed, strolled along the shore, picked some violets, and bivouacked in an olive-grove. The population, stupefied, concealed themselves. He avoided Antibes, and plunged into the mountains of Grasse, passing through Sernon, Barrême, Digne and Gap. At Sisteron twenty men could have stopped him, and he encountered nobody. He advanced without opposition from the inhabitants who a few months earlier had wanted to cut his throat. When handfuls of soldiers entered the void which formed around his giant shadow, they were seduced irresistibly by the sight of his eagles. His enemies, spellbound, searched for him and failed to find him; he hid himself in his glory, as the lion of the Sahara clothes himself in the sun’s rays to divert the gaze of dazzled hunters. Clothed in a fiery whirlwind, the blood-stained phantoms of Arcola, Marengo, Austerlitz, Jena, Friedland, Eylau, Borodino, Lützen and Bautzen, provided an escort for him of a million dead. From the heart of this column of fire and smoke, there issued, at the entrance to every town a few trumpet blasts accompanied by the brandishing of the tricolour standards: and the gates of the town fell. When Napoleon crossed the Niemen at the head of four hundred thousand infantry and a hundred thousand cavalry, to blow up the palace of the Tsars in Moscow, it was less astonishing than when, breaking his ban, and hurling his chains in the faces of kings, he travelled alone, from Cannes to Paris, to sleep peacefully in the Tuileries.

‘Retoure de l'Ile d'Elbe’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p229, 1845)

The British Library

Book XXIII: Chapter 2: The Legitimacy in a state of torpor – Benjamin Constant’s article – Marshal Soult’s order of the day – A Royal session – The Petition of the Law School to the Chamber of Deputies

BkXXIII:Chap2:Sec1

Alongside this astonishing invasion by a single individual, one must set another, a repercussion of the first: the Legitimacy was seized by stupor; the paralysis at the heart of the State spread through its limbs and rendered France immobile. For twenty days, Bonaparte advanced stage by stage; his eagles flew from steeple to steeple, and throughout his journey of six hundred miles, the Government, master of all, with money and labour at its disposal, had neither the time nor the means to blow a bridge, or fell a tree, to delay for even an hour the advance of this man whom the population chose not to oppose, but whom they no longer followed.

This torpor on the part of the Government seemed so much the more deplorable in that public opinion in Paris was extremely confused; it was open to any suggestion, despite Marshal Ney’s defection. Benjamin Constant wrote in the newspaper:

‘Having scourged our nation, he left French soil. Who did not believe he had left forever? Suddenly he appears again, promising the French liberty, victory and peace. The author of the most tyrannical constitution ever to bind France, does he now speak of liberty? Yet he is the one who, for fourteen years, has eroded and destroyed liberty. He has not the justification of lineage, the customary excuse of power; he was not born to the purple. He has enslaved his fellow citizens, enchained his equals. He did not inherit power; he desired and meditated tyranny: what liberty can he promise? Are we not a thousand times freer than under his Empire? He promises victory, and has abandoned his troops three times, in Egypt, Spain, and Russia, leaving his companions in arms to the triple agonies of cold, misery and despair. He has brought on France the humiliation of being invaded; he has lost the conquests we made prior to him. He promises peace yet his mere name is a signal for war. The nation so unfortunate as to serve him would become an object of hatred to all Europe; his triumph would be the beginning of mortal combat against the whole civilised world. He has nothing to re-claim or to offer. Who could he convince, who could he sway? Internal strife, external war, those are the gifts he brings us.’

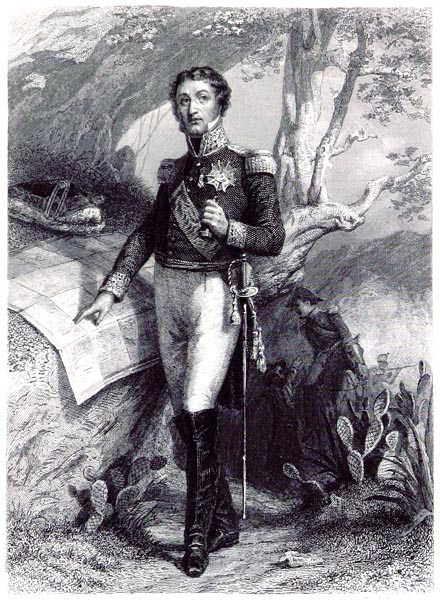

Marshal Soult’s order of the day, dated the 8th of March 1815, followed Benjamin Constant’s ideas closely, in an outburst of loyalty:

‘Soldiers,

That man who recently abdicated, in the sight of all Europe, the power he had usurped, which he had used so fatefully, has landed on French soil which he should never have seen again.

What does he desire? Civil war: what does he seek? Traitors: where will he find them? Shall it be among those soldiers he has deceived and sacrificed so many times, wasting their bravery? Shall it be in the bosoms of those families whom his name alone fills with fear?

Bonaparte despises us enough to believe that we will desert our legitimate and beloved sovereign, to share the fate of a man who is no better than an adventurer. He believes it, the madman! And his last foolish act is to make it known.

Soldiers, the French army is the bravest in Europe, it will also be the most loyal.

Let us rally to the banner of the fleur-de-lis, to the voice of the father of the nation, of that worthy heir to the virtues of the great Henry. He himself decreed for you the duties which you have to fulfil. He places at your head that prince, a model of French knighthood, whose happy return to our country has already driven out the usurper, and who now by his presence will destroy the usurper’s sole and final hope.’

‘Le Maréchal Soult’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p173, 1845)

The British Library

Louis XVIII appeared before the Chamber of Deputies on the 16th of March; it was a question of France and the world. When His Majesty entered, the Deputies and spectators in the gallery bared their heads and stood; their acclamations made the walls of the room shake. Louis XVIII climbed slowly to the throne; the Princes, Marshals and Captains of the Guard ranged themselves on either side of the King. The cries ceased; all were silent: in that hush, it was as though Napoleon’s distant tread could be heard. His Majesty, seated, looked at the assembly for a moment and uttered this speech in a firm voice:

‘Gentlemen,

‘At this moment of crisis, when a public enemy has penetrated one region of my kingdom and threatens the liberty of all the rest, I come amongst you to tighten further the bonds which, by uniting you and I, create the strength of the State; I come to address you and reveal my feelings and wishes to all France.

I have seen my country once more; I have achieved her reconciliation with the foreign powers, who, be in no doubt, will stay faithful to the treaties which have brought us peace; I have laboured for the happiness of my people; I have received, I do receive, every day the most touching marks of their affection; could I end my career more gloriously, at sixty years of age, than by dying in her defence?

I fear nothing now as regards myself, but I fear for France: he who comes to light the torch of civil war amongst us carries also the scourge of foreign war; he comes to set our country once more beneath his iron yoke; he comes to destroy finally the Constitutional Charter I have granted you, that Charter, which will be my finest title in the eyes of posterity, that Charter which every French person cherishes and which I swear now to maintain: let us rally round it then.’

The King was still speaking when a cloud deepened the gloom in the chamber; all eyes turned to the ceiling to discover the reason for this sudden darkness. When the monarch and legislator ceased to speak, cries of: ‘Long live the King!’ rose again in the midst of tears. ‘The Assembly,’ reported the Moniteur accurately, ‘electrified by the King’s sublime speech, were standing, hands outstretched towards the throne. Nothing could be heard but the words; ‘Long Live the King! Our lives for the King! The King: in life and death!’ repeated in a delirium that all French hearts shared.’

‘Louis VIII’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p237, 1845)

The British Library

Indeed, the spectacle was filled with pathos: an old infirm King, who, as a reward for the massacre of his family and twenty-three years of exile, had brought France peace, liberty, and an amnesty for all the insults and all the misfortunes; this patriarch of sovereigns came to tell the nation’s Deputies that at his age, having seen his country once more, he could find no finer end to his career than dying in defence of his people! The Princes swore loyalty to the Charter; the belated pledges were terminated by those of the Prince de Condé and the adherence of the father of the Duc d’Enghien. That heroic race about to be extinguished, that race of patrician swords, seeking in liberty a shield against a younger, longer and crueller plebeian sword, offered, in the light of a multitude of memories, something sad in the extreme.

Louis XVIII’s speech, once known beyond those walls, inspired inexpressible transports of joy. Paris was wholly Royalist, and remained so during the Hundred Days. Women in particular supported the Bourbons.

The young today adore Bonaparte’s memory, because they are humiliated by the role the present Government forces France to play in Europe; youth, in 1814, welcomed the Restoration, because it felled tyranny and elevated liberty. In the ranks of the Royalist cause were to be found Monsieur Odilon Barrot, a large number of the students of the School of Medicine, and the whole of the Law School; the latter addressed the following petition to the Chamber of Deputies on the 13th of March:

‘Gentlemen,

‘We offer ourselves for King and country; the whole Law School asks permission to march. We will not abandon our sovereign, or our Constitution. Loyal to French honour, we ask you for weapons. The feeling of affection we have towards Louis XVIII matches yours in constancy and devotion. We desire no more chains, we desire liberty. We will have it: they come to tear it from us: we will defend it to the death. Long live the King! Long live the Constitution!’

In this energetic language, natural and sincere, you can feel the generosity of youth and its love of liberty. Those who tell us today that the Restoration was received by France with sadness and disgust are either ambitious individuals promoting their party, or young men who knew nothing of Bonaparte’s oppression, or old revolutionary and Imperialist liars who, having applauded the return of the Bourbons with everyone else, now insult, according to their custom, whatever has fallen, and return instinctively to assassination, a police state, and servitude.

Book XXIII: Chapter 3: A plan for the defence of Paris

BkXXIII:Chap3:Sec1

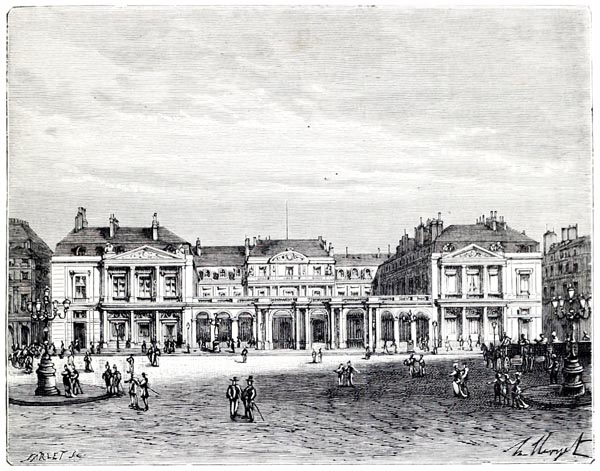

The King’s speech filled me with hope. Discussions were held at the residence of the President of the Chamber of Deputies, Monsieur Lainé. I met Monsieur de Lafayette there: I had only seen him at a distance in another epoch, that of the Constituent Assembly. The proposals varied; for the most part they were spineless, as happens when danger looms: some wanted the King to quit Paris and retire to Le Havre; others spoke of conveying him to the Vendée; this group here spewed out words without reaching a conclusion, that over there said we must wait and see what happens: yet what was happening was extremely apparent. I expressed a contrary opinion: a singular thing, Monsieur de Lafayette supported me, and warmly! (Monsieur de Lafayette confirms, in his Memoirs, precise as to facts, published since his death, the singular agreement of his opinion and mine concerning Bonaparte’s return. Monsieur de Lafayette sincerely loves honour and freedom. Note: Paris, 1840) Monsieur Lainé and Marshal Marmont were also of my opinion. I spoke thus:

‘Let the King keep his word; let him stay in the capital. The National Guard support us. Let us secure Vincennes. We have money and weapons: with money we command the weak and greedy. If the King leaves Paris, Paris will allow Bonaparte to enter; Bonaparte as master of Paris is master of France. The army has not gone over en masse to the enemy; several regiments, many generals and officers, have not yet betrayed their oath: let us stand firm, and they will remain loyal. Let us disperse the Royal family, only protecting the King. Let MONSIEUR go to Le Havre, the Duc de Berry to Lille, the Duc de Bourbon to the Vendée, the Duc d’Orléans to Metz; Madame la Duchesse and Monsieur le Duc d’Angoulême are already in the Midi. Our various points of resistance will prevent Bonaparte from concentrating his forces. Let us barricade ourselves within Paris. The National Guards of neighbouring departments are already coming to our aid. In the midst of this activity, our aged monarch, protected by Louis XVI’s last will and testament, with the Charter in his hand, will rest easy seated on his throne in the Tuileries; the Diplomatic Corps can range themselves around him; the two Chambers can meet in the two pavilions of the château; the King’s household can camp on the Carrousel and in the Tuileries Garden. We will line the quays and the riverside terrace with cannon: let Bonaparte attack us in that scenario; let him assault our barricades one by one; let him bombard Paris if he wishes and if he has the guns; let him render himself obnoxious to the whole population, and we shall see the result of his enterprise! If we can hold out for only three days, victory is ours. The King, by defending himself in his own palace, will arouse universal enthusiasm. Finally, if he must perish, let him die in a manner worthy of his rank let Napoleon’s last exploit be the slaughter of an old man. Louis XVIII, by sacrificing his life, would have won the only battle he shall have fought; he would win it to benefit the liberty of the human race.’

So I spoke: one is never welcomed for saying all is lost when nothing has yet been tried. What would have been finer than an ancient son of Saint Louis overcoming with the French, in a few moments, a man whom all the kings conjured from Europe spent so many years trying to defeat?

This suggestion, apparently born out of desperation, was in fact quite realistic and offered not the least risk. I will always remain convinced that Bonaparte, finding Paris opposed to him, and the king in residence, would not have attempted to take it by force. Without artillery, without supplies, without money, he had with him only an army collected by chance, still in disorder, astounded at their sudden change of cockade, their oaths of loyalty sworn in flight on the highways: they would have been swiftly scattered. A few hours delayed and Napoleon would have been lost; it only required a little courage. At that time we could even count on sections of the army; the two Swiss regiments kept faith: did not Marshal Gouvion Saint-Cyr re-adopt the white cockade in the Orléans garrison two days after Bonaparte entered Paris? From Marseilles to Bordeaux, everyone recognised the King’s authority throughout the whole of March: at Bordeaux the troops wavered; they would have remained loyal to the Duchesse d’Angoulême, if the King had been known to be at the Tuileries and Paris defending itself. The provincial towns would have followed Paris’s lead. The Tenth Regiment of the Line fought well under the Duc de Angoulême; Masséna revealed himself as cautious and undecided; at Lille, the garrison responded to a lively proclamation by Marshal Mortier. If all this evidence of potential loyalty existed despite the possibility of the King’s flight, what might there not have been in the event of resistance?

If my plan had been adopted, there would have been no new foreign invasion of France; our Princes would not have returned with the enemy armies; the Legitimacy would have saved itself. There would have been one thing only to fear after that success: too great a confidence on the part of Royalty in armed force, and in consequence attempts to limit our national rights.

Why was I born to an epoch to which I was so badly suited? Why was I a Royalist against my instincts at a time when the wretched race at Court neither listened to nor understood me? Why was I thrown amongst that crowd of mediocrities who treated me like an idiot, when I spoke of courage; as a revolutionary if I spoke of freedom?

It was merely a question of self-defence! The king had nothing to fear, and my plan pleased him sufficiently by the grandeur, à la Louis XIV somewhat, that it possessed; but other faces lengthened. The diamonds from the royal coronet were packed away (acquired in the past with the sovereigns’ private funds), leaving thirty-three million crowns in the treasury and forty-two millions of personal effects. These seventy-five millions were the fruits of taxation: they should have been returned to the people rather than left to the tyrant!

A dual procession mounted and descended the stairs of the Pavillon de Flore; people asked what was to be done: there was no reply. The Captain of the Guards was asked; the chaplains, cantors, and priests were interrogated: nothing: idle chatter, idle projects, and an idle flow of news. I have seen young men weep in fury over their vain requests for orders and weapons; I have seen women taken ill in their anger and contempt. Approach the King, impossible; etiquette sealed the door.

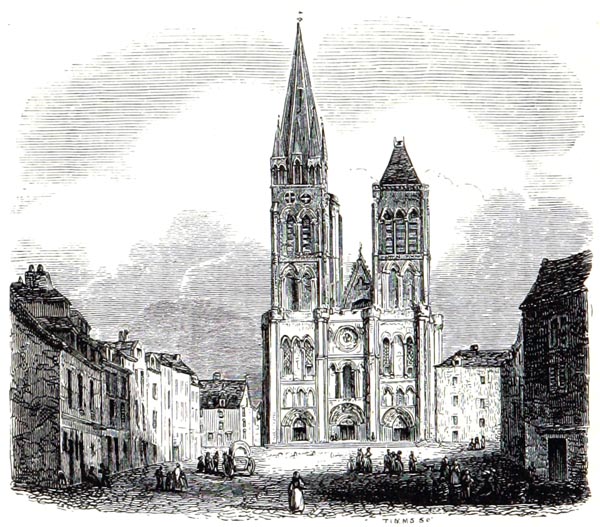

‘Palais-Royal’

La France Illustrée: Géographie, Histoire, Administration, Statistique - Victor Adolfe Malte-Brun (p352, 1881)

Internet Archive Book Images

The grand measure decreed to counter Bonaparte was an order to charge (courir sus): Louis XVIII, with deficient limbs, to charge a conqueror over-striding the earth! That formula of the ancient law, revived for this occasion, suffices to reveal the mental capacity of the officers of State at that time. To charge in 1815! Charge! Against what: against a wolf, against a brigand chief, against an errant Lord? No: against Napoleon who had himself charged kings, captured them, and branded them on the shoulder forever with his ineffaceable N!

In this decree, when considered more closely, a political truth which no one has observed is revealed: the legitimate race, strangers to the nation for twenty-three years had remained in the hour and place where the Revolution had left them, while the nation had advanced through time and space. From that arose the impossibility of them understanding or re-joining it; religion, ideas, interests, language, heaven and earth, all were different for people and King, because they were no longer at the same point on the road, because they were separated by a quarter of a century, equivalent to many centuries.

But if the order to charge appears strange in its retention of an ancient legal phrase, had Bonaparte the intention initially to act in any more effective a way, even though he was employing a new manner of speech? The papers of Monsieur de Hauterive, catalogued by Monsieur Artaud, prove that it took a great deal of effort to prevent Napoleon from having the Duc d’Angoulême shot, despite what the official statement in the Moniteur said, a statement issued and left behind for show: he found it unacceptable that the prince stood up for himself. And yet the fugitive from Elba, in leaving Fontainebleau, had recommended that his soldiers should be loyal to the monarchFrance had chosen. At the moment when Napoleon again spoke of killing a son of France, was he anything more than the dual usurper of the new Bourbon monarchy and popular liberty? What! Was the Duc d’Enghien’s blood insufficient for him? Bonaparte’s family had been respected; Queen Hortense had obtained the title of the Duchesse de Saint-Leu from Louis XVIII; Caroline, who still reigned in Naples, had merely had her kingdom traded by Monsieur de Talleyrand during the Congress of Vienna.

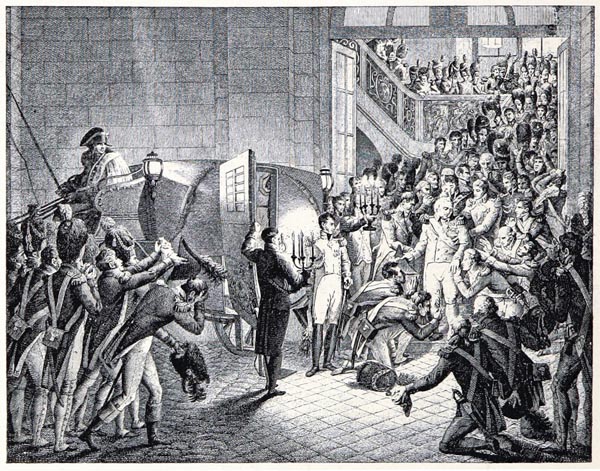

That epoch, where everyone lacked openness, seared the heart: everyone threw a profession of loyalty before them, like a footbridge over the difficulties of the hour; even if it meant changing direction, the difficulty was traversed: only youth was sincere, because it retained traces of the cradle. Bonaparte solemnly declares that he renounces the crown; he leaves and returns after nine months. Benjamin Constant publishes his vigorous protest against the tyrant, and changes his mind within twenty-four hours. Later you will discover, in a further book of these Memoirs, who it was inspired him to this noble action, to which the changeability of his nature did not allow him to remain faithful. Marshal Soult stirrs the troops against their former leader; a few days later he roars with laughter at his proclamation in Napoleon’s study at the Tuileries, and becomes Major-General of the Army of Waterloo; Marshal Ney kisses the King’s hand, swears to bring him Bonaparte in an iron cage, and then hands over to Bonaparte all the corps he commands. Alas! And the King of France....He declares that at sixty he can embrace no better end to his career than dying in defence of his people.and then goes off to Ghent! At this lack of truthfulness in the expression of feeling, at this discord between words and actions, one was seized with disgust at the human species.

Louis XVIII, on the 20th of March, intended to died at the heart of France; if he had kept his word, the Legitimacy might have endured for a century; nature even seemed to have robbed the aged king of the means of retreat, by saddling him with infirm health; but the future destiny of the human race would have been hindered if the author of the Charter had accomplished his resolution. Bonaparte hastened to the aid of the future; that Christ of evil powers took this latest paralytic by the hand, and said to him: ‘Take up thy bed and go; surge, tolle lectum tuum.’

‘Départ du Roi, le 19 mars 1815. Dessiné par Heim, Gravé par Couché Fils’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p930, 1888)

The British Library

Book XXIII: Chapter 4: The flight of the King – I leave with Madame de Chateaubriand – Problems on the way – The Duc d’Orléans and the Prince de Condé – Tournai, Brussels – Memories – The Duc de Richelieu – The King halts at Ghent and summons me

BkXXIII:Chap4:Sec1

It was evident that they were about to decamp: due to the fear of being detained, they did not even warn those who, like me, might have been shot an hour after Bonaparte entered Paris. I met the Duc de Richelieu on the Champs Elysees: ‘They are deceiving us,’ he said to me; ‘I am mounting guard here, since I do not intend to wait for the Emperor alone in the Tuileries.’

Madame de Chateaubriand had sent a servant to the Carrousel on the evening of the 19th, with orders not to return unless he was certain of the King’s flight. At midnight, the servant not having returned, I went off to bed. I was just getting ready for sleep, when Monsieur Clausel de Coussergues entered. He told us that His Majesty had left and was heading for Lille. He brought me this news on behalf of the Chancellor, who knowing I was in danger, violated security on my behalf and brought me twelve thousand francs, due to me on my appointment as Minister for Sweden. I insisted on staying, not wishing to leave Paris until I was absolutely sure of the Royal move. The servant sent to discover it, returned: he had seen the carriages file out of the courtyard. Madame de Chateaubriand pushed me into her carriage at four in the morning on the 20th of March. I was in such a fit of rage I knew neither where I was going nor what I was doing.

We left by the Barrière Saint-Martin. At dawn, I watched the crows, descending peacefully from the elms by the highway where they had spent the night, about to breakfast in the fields, without bothering about Louis XVIII or Napoleon: they were not, those crows, obliged to leave their country, and thanks to their wings, they scorned the dreadful road I was jolting over. Old friends from Combourg! We were more akin when long ago at daybreak we dined on blackberries among the dense thickets of Brittany!

The road had broken up, the weather was wet, and Madame de Chateaubriand felt ill: she looked constantly through the window at the rear of the vehicle to see if we were being pursued. We slept at Amiens, where Du Cange was born; then at Arras, Robespierre’s home city: there, I was recognised. Having despatched a request for horses, on the morning of the 22nd, the post-master said they had been commandeered by a general who was carrying news to Lille of the Emperor’s triumphant entry into Paris; Madame de Chateaubriand was dying of fear, not for herself, but for me. I hastened to the stables and, with money, removed the difficulty.

Arriving beneath the ramparts of Lille on the 23rd, at two in the morning, we found the gates closed; the order was not to open them to anybody. They could not or would not say if the King had entered the city. I engaged a coachman for a few louis, to take us to the other side of the city via the exterior of the glacis, and then conduct us to Tournai; in 1792, I had taken this same road, at night, on foot, with my brother. Reaching Tournai, I learnt that Louis XVIII had definitely entered Lille with Marshal Mortier, and that he counted on defending it. I sent a courier to Monsieur Blacas, begging him to send me a permit allowing me to enter the city. My courier returned with a permit from the commandant but no word from Monsieur Blacas. I was setting out in a carriage to return to Lille, leaving Madame de Chateaubriand at Tournai, when the Prince de Condé arrived. We learnt from him that the King had left and that Marshal Mortier had provided an escort for him to the border. After this explanation, it was obvious that Louis XVIII had not been at Lille when my letter arrived there.

The Duc d’Orléans soon followed the Prince de Condé. Appearing discontented, he was content at heart to find he was out of the fight; the ambiguity of his declaration of support for the Charter and his conduct bore the imprint of his nature. As for the aged Prince de Condé, the Emigration remained his fixed point. He was not afraid of Monsieur de Bonaparte; he would fight if they wished, he would leave if they wished: things were a little confused in his brain; he did not know if he was stopping at Rocroi to give battle, or to go and dine at the Grand-Cerf. He struck camp a few hours before us, telling me to recommend the innkeeper’s coffee to those of his household whom he had left behind. He did not know I had handed in my resignation on the death of his grandson; he only felt about that name a certain halo of glory which may as well have clung to some Condé whom he did not recall.

Do you remember my first passing through Tournai with my brother, during my first emigration? Do you remember, regarding it, the man changed into a donkey, the girl from whose ears sprang ears of corn, the cloud of rooks that spread fire everywhere? In 1815, we were like that cloud of rooks ourselves, except that we spread no fires. Alas! I was no longer accompanied by my unfortunate brother! Between 1792 and 1815, the Republic and the Empire had vanished: what revolutions had taken place in my life also! Time had ravaged me along with all the rest. And you, the younger generations of this age, let twenty-three years go by, and you will ask at my grave where all your present passions and illusions are.

The Bertin brothers had arrived at Tournai: Monsieur Bertin de Vaux returned to Paris; the other Bertin, the elder Bertin, was my friend. You will know from the fifteenth book of these Memoirs what attracted me to him.

From Tournai we travelled to Brussels: there I found no Baron de Breteuil, no Rivarol, nor all those young aides-de-camps, now dead or grown old which are the same thing. There was no sign of the barber who had given me refuge. I carried a pen and not a musket; I had turned from soldiering to scribbling on paper. I located Louis XVIII; he was in Ghent, where Messieurs Blacas and de Duras had escorted him: their intention at first had been to have the King embark for England. If the King had consented to that project, he would never have recovered the throne.

Entering a boarding house to look at a room, I found the Duc de Richelieu, smoking while reclining on a sofa, in the depths of a darkened chamber. He spoke of the Princes in a coarse manner, declaring that he was off to Russia, and wanted to hear no more of that lot. Madame the Duchesse de Duras, who had arrived in Brussels had the grief of her mother dying there.

The capital of Brabant is hateful to me; it has never served me for anything but a route to exile; it has always brought me, or my friends, trouble.

An order from the King summoned me to Ghent. The Royal volunteers and the Duc de Berry’s tiny army had been sent away to Béthune, to the mud and mess of a military debacle: there had been moving farewells. Two hundred men of the King’s household remained and were confined to Alost; my two nephews, Louis and Christian de Chateaubriand, were part of that corps.

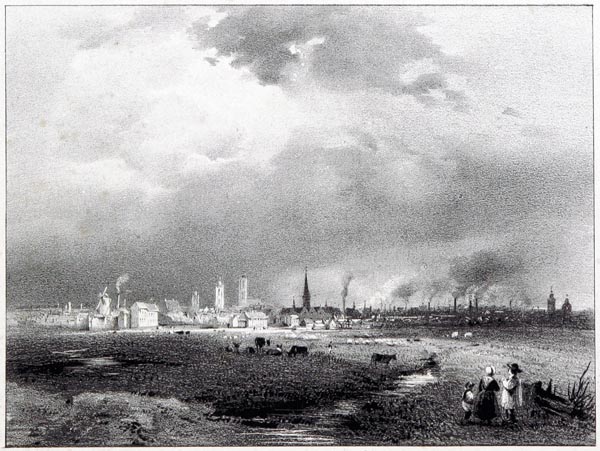

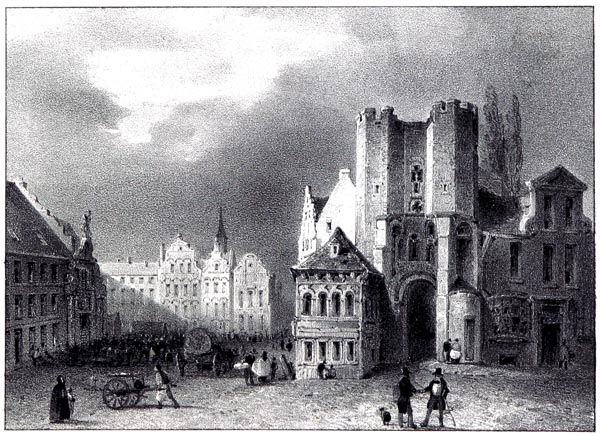

‘Vue Générale de Gand’

Vues Pittoresques des Principaux Monuments de la Ville de Gand - C. Auguste Voisin (p10, 1836)

The British Library

Book XXIII: Chapter 5: THE HUNDRED DAYS IN GHENT – The King and his council – I become interim Minister of the Interieur – Monsieur de Lallay-Tollendal – Madame the Duchesse de Duras – Marshal Victor– The Abbé Louis and Comte Beugnot – The Abbé Montesquiou – Dining on white fish: guests

BkXXIII:Chap5:Sec1

I was given a billet which I did not take advantage of: a Baroness whose name I forget sought out Madame de Chateaubriand at the inn and offered us a room at her house: she begged us to accept it with such good grace! ‘Pay no attention,’ she said, ‘to what my husband tells you: he has a problem with his mind.you understand? My daughter is also a bit strange; she has terrible fits, poor child! But the rest of the time she is gentle as a lamb. Alas! It is not she who causes me the most grief it is my son Louis, the youngest of my children: if God does not help him, he will be worse than his father.’ Madame de Chateaubriand refused politely to go and live among such reasonable people.

The King, comfortably lodged, having his servants and his guards around him, formed his council. The empire of this great monarch comprised a palace of the Kingdom of the Low Countries, which palace was situated in a city which, though it was the city that saw Charles V’s birth, had been the headquarters of one of Bonaparte’s prefectures: those two names between them covered a good number of events and centuries.

The Abbé de Montesquiou being in London, Louis XVIII named me as Minister of the Interior for the interim. My correspondence with the regions did not require much effort; I kept my correspondence with the prefects, sub-prefects, mayors and deputies of the fine towns within our frontiers up to date quite easily; I did not repair many roads and I let the church-towers crumble; my budget scarcely increased my wealth; I had no private funds; only, by a glaring abuse, I drew concurrent salaries; I was still Minister plenipotentiary of His Majesty to the King of Sweden, who, like his compatriot, Henri IV, reigned by right of conquest, rather than by right of birth. We spoke round a table covered with green velvet in the King’s study. Monsieur de Lally-Tollendal who was, I think, Minister for Public Instruction, gave extensive speeches, with more flesh on them than his person: he cited his illustrious ancestors the Kings of Ireland and muddled his father’s trial with those of Charles I and Louis XVI. At night he recovered from the tears, sweat and speeches he had poured out in council, with a lady who had hastened from Paris carried along by enthusiasm for his genius; he sought virtuously to cure her of her disease, but his eloquence triumphed over his virtue and only drove the poison deeper.

Madame the Duchesse de Duras came to rejoin Monsieur the Duc de Duras among the exiles. I will speak no more of the evils of adversity, since I spent three months with this excellent woman, conversing of all that minds and true hearts can find in an agreement of tastes, ideas, principles and feelings. Madame de Duras was ambitious for me: she alone knew from the start what value I might have politically; she was continually disappointed by the envy and blindness that distanced me from the King’s Council; but she was yet more disappointed by the obstacles that my character placed in the way of my fortunes: she scolded me, she wanted to cure me of my casual attitude, my frankness, my naivety, and make me adopt the methods of the courtiers, which she herself could not stand. Nothing perhaps serves more to cement attachment and gratitude than to feel yourself under the patronage of a superior friendship, which by virtue of its social influence, makes your faults pass for qualities, your imperfections for charms. A man assists you for what it is worth to him, a woman because of what you are worth: which is why of the two empires the first is so hateful, the second so sweet.

Since I lost that most generous individual, of so noble a soul, a mind which united something of the powers of intellect of Madame de Staël with the grace of Madame de Lafayette’s talent, I have not ceased, while weeping, to reproach myself for the changeability with which I may have occasionally distressed those hearts devoted to me. Let us have particular regard to character! Let us consider that we can, despite a profound relationship, nevertheless poison days that we would buy back at the cost of all our blood. When our friends have descended into the grave, what means have we of repairing our mistakes? Are our useless regrets, our vain repentance a remedy for the pain we have given them? They would have loved a smile from us while they were alive more than all our tears for them after their death.

The delightful Clara (Madame the Duchesse de Rauzan) was in Ghent with her mother. Between us, we made terrible couplets to the air of La Tyrolienne. I have held on my lap plenty of pretty little girls who are young grandmothers today. When you leave a woman behind you, married before you at sixteen, and you return sixteen years later, you will find she is still the same age: ‘Ah, Madame, you have not aged a day!’ Doubtless: but you say that to the young girl, to the young girl you again lead to the altar. But you, sad witness of her two marriages, you close away the sixteen years you have received at each union: wedding gifts which will hasten your own marriage to a pale lady, a little on the thin side.

Marshal Victor came to stand with us, at Ghent, with admirable straightforwardness: he asked for nothing, never bothered the King by being over-eager; one scarcely saw him; I do not know if he was ever accorded the honour and grace of even a single invitation to dine with His Majesty. I subsequently met Marshal Victor; I have been his colleague at the Ministry, and always the same excellent character was on view. In Paris, in 1823, Monsieur le Dauphin was extremely harsh towards this honest soldier: a fine thing: that this Duke of Belluno should receive, in return for his humble devotion, such thoughtless ingratitude! Ingenuousness attracts me and moves me, even though on certain occasions it appears ultimately as an expression of naivety. Thus the Marshal told me of the death of his wife in the language of a soldier, and made me cry: he pronounced coarse words so hastily, and edited them with so much modesty, that one even had to smile at them.

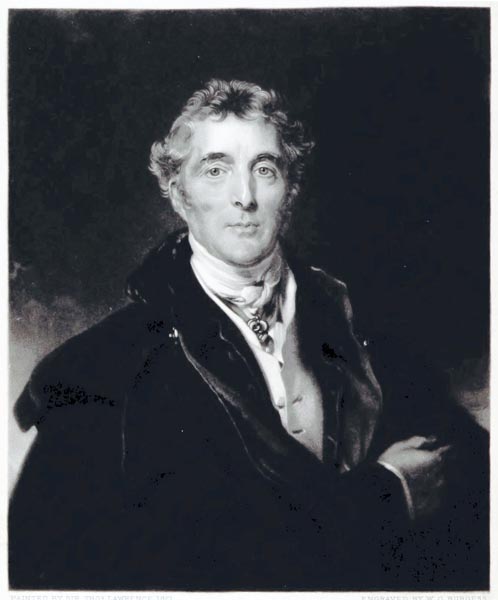

‘Le Maréchal Victor’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p133, 1845)

The British Library

Monsieur de Vaublanc and Monsieur Capelle, rejoined us. The former told us he had a bit of everything in his satchel. Do you want some Montesquieu? He’s here: some Bossuet? Here he is. As soon as the assembly seemed to wish for another face, travellers arrived for us.

The Abbé Louis and Monsieur the Comte Beugnot stayed at the inn where I was lodging. Madame de Chateaubriand had dreadful fits of breathlessness, and I stayed up to watch over her. The two new arrivals installed themselves in a room which was only separated from my wife’s by a thin partition; it was impossible not to hear, unless one stopped one’s ears: between eleven and midnight the occupants raised their voices; the Abbé Louis who spoke wolfishly, and jerkily, said to Monsieur Beugnot: ‘You, a Minister? You won’t be one any longer! You’ve perpetrated nothing but idiocies!’ I could not hear Monsieur the Comte Beugnot’s reply clearly, but he spoke of thirty-three millions left behind in the Royal Treasury. The Abbé pushed a chair over, apparently in anger. Despite the crash, I grasped these words; ‘The Duc de Angoulême? He must buy the National assets at the gate of Paris. I will sell the rest of the State forests. I will fell them all, the elms along the highway, the woods of Boulogne, the Champs-Elysées: what use are they? Hey!’ Monsieur Louis’ brutality was his principal merit; his talent was a stupid love of material interests. If the Finance Minister drew the forests after him, he doubtless possessed a different secret to that of Orpheus, who made the woods follow him by his beautiful music. In the jargon of the time, Monsieur Louis was described as a specialist; his financial speciality had led him to pile up taxpayers’ money in the Treasury, to have it seized by Bonaparte. Good for the Directory at the most, Napoleon had no need of this specialist, who was not at all unique.

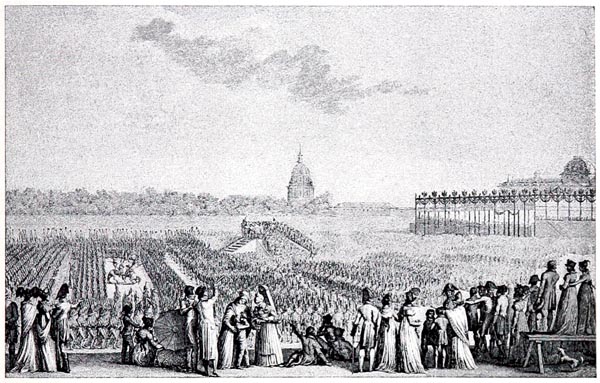

The Abbé Louis had come to Ghent to reclaim his Ministry; he was very close to Monsieur de Talleyrand, with whom he had officiated solemnly at the First Federation on the Champ-de-Mars: the Bishop served as priest, the Abbé Louis as deacon, and the Abbé Desrenaudes as sub-deacon. Monsieur de Talleyrand, remembering that amazing profanation, said to Baron Louis: ‘Abbé, you were a very fine deacon on the Champ-de-Mars!’ We endured that shame under Bonaparte’s grand tyranny: had we to endure it again?

The Very-Christian King was protected from all reproach of that kind: he had a married bishop on his Council, Monsieur de Talleyrand; a priest with a concubine, Monsieur Louis; an Abbé who scarcely practised his religion, Monsieur de Montesquiou.

The latter, a man as feverish as a consumptive, with a certain facility in speaking, had a narrow mind adept at denigration, a heart full of hatred, an embittered nature. One day when I had spoken out in favour of the freedom of the press, the descendant of Clovis, passing in front of me, who only derived from the Breton Mormoran, gave me a shove in the leg with his knee, which was not in good taste; I returned it, which was impolite: we played at being the Coadjutor and the Duc de La Rochefoucauld. The Abbé de Montesquiou amusingly called Monsieur de Lally-Tollendal ‘a creature after the English manner’.

In the rivers around Ghent, they angled for a very delicate white fish: we would eat, tutti quanti (all and sundry) these fine fish in the restaurant, waiting for the battles which end empires. Monsieur Laborie was always present at the rendezvous: I had met him for the first time at Savigny, when, fleeing from Bonaparte, he entered by way of one of Madame de Beaumont’s windows, and exited through another. Tireless in his efforts, proliferating errands and notes, as pleased at rendering a service as others are at receiving them, he has been slandered: the essence of slander is not the accusation of having been slandered but the slanderer’s reasons. I showed weariness with the promises in which Monsieur Laborie was wealthy; but why? Dreams are like torments: they always pass an hour or two. I have often taken in hand, with a golden bridle, vicious old memories which could no longer stand upright, which I had taken for young and dashing hopes.

I also saw Monsieur Mounier at the white-fish dinners, a man of reason and probity. Monsieur Guizot too deigned to honour us with his presence.

Book XXIII: Chapter 6: THE HUNDRED DAYS IN GHENT, CONTINUED – The Ghent Moniteur – My report to the King: the effect of that report in Paris – Falsification

BkXXIII:Chap6:Sec1

A Moniteur was established in Ghent: my report to the King of the 12th of May, inserted in this paper, show that my sentiments regarding the freedom of the press and regarding foreign domination have been identical at all times and in all places. I can cite these passages today; they do not contradict my record in any way:

‘Sire, you should begin to set a crown on the institutions whose foundations you have laid. You have specified a date for the commencement of hereditary peerages; the Government should have acquired greater unity; the Ministers should have become members of the two Chambers, according to the true spirit of the Charter; a law should have been proposed whereby one could be elected as a member of the Chamber of Deputies at under forty years of age and citizens could enjoy a genuine political career. Work was going to start on a legal code covering press offences, after the adoption of which the press would have been entirely free, since that freedom is inseparable from representative government.........

Sire, this is the moment to register a solemn protest: all your Ministers, all the members of your council, are indissolubly attached to wise principles of freedom; they draw from their proximity to you that love of law, order, and justice, without which there is no happiness for a nation. Sire, may we be permitted to say to you, we are ready to shed our last drop of blood for you, to follow you to the ends of the earth, to share with you the tribulations which it may please the Almighty to send you, because we believe before God that you will maintain the constitution you have granted to your people, that the sincerest wish of your royal spirit is the liberty of the French. If it had been otherwise, Sire, we would always have died at your feet in the defence of your sacred person; but we would merely have been your soldiers, we would have ceased to be your councillors and ministers.....

Sire, at this moment we share your Royal grief; there is not one of your councillors and ministers who would not give his life to prevent the invasion of France. Sire, you are French, we are French! Sensitive to the honour of our country, proud of the glory of our arms, admirers of our soldiers’ courage, we would wish, at the heart of their battalions, to shed our last drop of blood to show them their duty or to share with them the triumphs of the Legitimacy. We cannot view without the most profound sorrow the evils that are ready to fall upon our country.’

Thus, at Ghent, I proposed to give the Charter what it still lacked, and I showed my sorrow at the new invasion which threatened France: I was as yet only an exile whose hopes lacked the events which could re-open the gates of my country to me. Those pages were written in a State belonging to a royal ally; among princes and émigrés who detested the freedom of the Press; and in the midst of armies marching to conquest of whom we were, so to speak, prisoners: those circumstances added some power perhaps to the sentiments I dared to express.

My report, arriving in Paris, caused a great stir; it was reprinted by Monsieur Le Normant the younger, who risked his life on that occasion, and for whom I took all the trouble in the world to obtain a fruitless patent as printer to the King. Bonaparte acted or sanctioned action, in a manner barely worthy of him: when my report appeared they did as the Directory had done on the appearance of Cléry’s Memoirs, they doctored the piece: I was supposed to have suggested to Louis XVIII inanities regarding the restoration of feudal rights, church tithes, and the return of national assets, as if the original publication in the Ghent Moniteur, at a precise and known date, did not contradict this imposture; but they needed a timely deception. The pseudonymous author charged with this dishonest pamphlet was a military man of reasonably high rank: he was destitute after the Hundred Days; his destitution was accounted for by his conduct towards me; he sent his friends to me; they begged me to intervene in order that a worthy man should not lose his only means of existence: I wrote to the Minister of War, and obtained a retirement pension for the officer. He is dead: the officer’s wife remained devoted to Madame de Chateaubriand with a gratitude which I was far from entitled to. Certain things are over-valued; the most ordinary of people are susceptible to these acts of generosity. A reputation is granted to stale virtue: the superior soul is not that which forgives; it is that which has no need of forgiveness.

I am not sure why Bonaparte decided, on St Helena, that I had rendered a vital service at Ghent: if he assessed my role too favourably, at least he felt some appreciation of my political worth.

Book XXIII: Chapter 7: THE HUNDRED DAYS IN GHENT, CONTINUED – The Beguinage – How I was received – A grand dinner – Madame de Chateaubriand’s trip to Ostend – My life’s echoes – Anvers – A Stammerer– Death of a young English girl

BkXXIII:Chap7:Sec1

In Ghent, I avoided as much as I could, those intrigues antipathetic to my nature and wretched to witness; since, at heart, in our petty disaster I perceived social disaster. My refuge, among the idlers and wastrels, was the Beguinage Close: I wandered around this little world of women, veiled or wimpled, devoted to various Christian works; a region of calm sited, like the African Syrtes, at the edge of the storms. There, nothing disparate jarred my thoughts, since the religious atmosphere is so elevated, that it is never alien to the most serious resolutions: the solitaries of the Thebaid and those Barbarians who destroyed the Roman world were not in fact discordant or mutually exclusive.

I was received graciously in that Close as the author of Le Génie du Christianisme; everywhere I go, among Christians, priests come to meet me; then the mothers bring their children; the latter recite my chapter on First Communion. Then unfortunates present themselves who tell me the good I have been happy enough to bring them. My passage through a Catholic town is announced like that of the missionary and the doctor. I am moved by this dual reputation: it is the only pleasant memory of self that I preserve; the rest of my personality and my fame displease me.

I was frequently invited to dinners with the family of Monsieur and Madame d’Ops, a venerable father and mother surrounded by thirty or so children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. At Mr Coppens’ house, a gala dinner, which I was prevailed upon to attend, lasted from one in the afternoon to eight in the evening. I counted nine courses: they began with preserves and ended with mutton chops. Only the French know how to dine to a plan, as they are the only ones who know how to structure a book.

My Ministry kept me in Ghent; Madame de Chateaubriand, less pre-occupied, went off to visit Ostend, where I had embarked for Jersey in 1792. I had sailed down those same canals, exiled and at death’s door, that I walked now, still an exile, though in perfect health: always these echoes in my life! The sorrows and joys of my first emigration wakened in my thoughts; I saw England once more, my companions in misfortune, and Charlotte whom I was obliged to view again. No one is as guilty as I am of creating a real world by evoking shadows; it works in such a way that my remembered life takes on the feel of my present life. Even people I have never been involved with, when they die, invade my memory: one might almost say that no one can be my companion until they have entered the grave, which leads me to me believe I am myself one with the dead. Where others find eternal separation, I find eternal reunion; let one of my friends leave this earth, and it is as if he comes to stay with me; he leaves me no more. As the present world fades, the past world returns to me. If the current generations scorn the older generations, their contempt loses its force, in regard to me: I do not even perceive their existence.

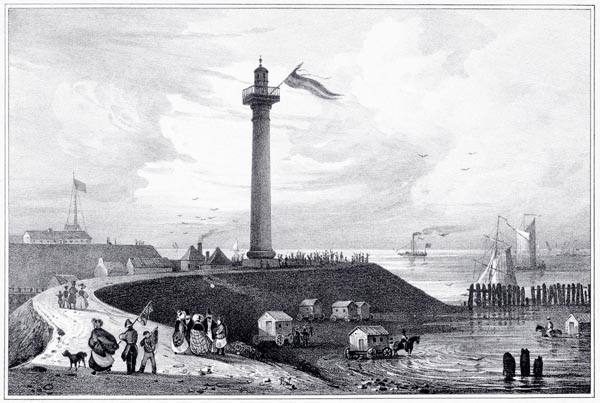

‘Ostend, 1830’

Paulus Lauters, Jobard, 1830 - 1831

The Rijksmuseum

My insignia of the Golden Fleece was not yet at Bruges, Madame de Chateaubriand could not bring it to me. At Bruges in 1426, there was a man whose name was John, who invented or perfected oil painting: let us give thanks to Jan van Eyck of Bruges; without the adoption of his method, Raphael’s masterpieces would have faded by now. Where did the Flemish painters steal the light which illuminates their paintings? What ray of Greek sunlight strayed to the shores of Batavia?

After her trip to Ostend, Madame de Chateaubriand set out for Anvers. In a cemetery there, she saw souls in Purgatory done in plaster daubed with soot and flames. At Louvain she recruited a gentleman who stammered at me, a knowledgeable professor who came to Ghent expressly to see so extraordinary a man as my wife’s husband. He addressed me: ‘Illus.ttt.rr.’ his speech detracted from his admiration, and I asked him to dine. When the Hellenist had drunk some curaçao, his tongue was freed. We started on the merits of Thucydides, whom the wine rendered clear as crystal to us. In order to contend with my guest, I ended up, I believe, talking Dutch; at least I no longer understood what I was saying.

Madame de Chateaubriand endured a sad night in the inn at Anvers: a young English girl, who had just given birth, died; for two hours she uttered her moans; then her voice grew weak, and her last groan, which scarcely reached the stranger’s ear died into eternal silence. The cries of that traveller, lonely and deserted, seemed a prelude to the thousand dying voices about to call out at Waterloo.

Book XXIII: Chapter 8: THE HUNDRED DAYS IN GHENT, CONTINUED – Unusual activity at Ghent – The Duke of Wellington – Monsieur – Louis XVIII

BkXXIII:Chap8:Sec1

The usual quietness of Ghent was made more apparent by the crowd of foreigners who now animated it, and who rose early. Belgian and English recruits took their exercise in the squares and under the trees of the walkways; gunners, supply-merchants, and dragoons landed artillery trains, herds of oxen, and horses that struggled in the air while they were lowered suspended in strapping; camp-followers unloaded their sacks, their children and their husbands’ rifles: all were heading, without knowing why and without the least interest in it, for the vast rendezvous of destruction that Bonaparte would provide for them. Along the canals, politicians could be seen gesticulating, near to some motionless fisherman, and émigrés trotting along from the King’s residence to Monsieur’s, from Monsieur’s to the King’s. The Chancellor of France, Monsieur D’Ambray, in a green coat, and a round hat, with an old novel under his arm, was off to the council to amend the Charter; the Duc de Lévis went to pay his court in old cut-away slippers, which his feet emerged from, because, like a brave modern Achilles, he had been wounded in the heel. He was full of wit, which one can see from his collection of maxims.

The Duke of Wellington visited from time to time to review the troops. After dinner each day, Louis XVIII went out in a coach and six with the First Gentleman of the Bedchamber and his Guards, to make the tour of Ghent, just as if he had been in Paris. If he met the Duke of Wellington on the way, he gave him a little nod of the head in patronage.

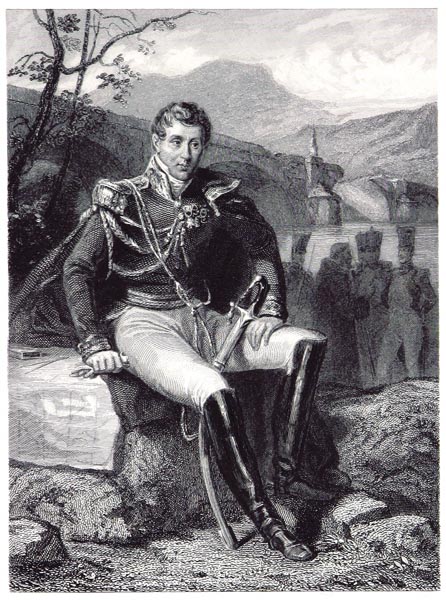

‘The Duke of Wellington’

The Dispatches of the Duke of Wellington During his Various Campaigns in India, Denmark, Portugal, Spain, the Low Countries and France from 1799 to 1818 - John Gurwood (p12, 1844)

The British Library

Louis XVIII never forgot his pre-eminence in the cradle; he was King everywhere, as God is God everywhere, in the nursery or the temple, at an altar of gold or of clay. He never made a single concession to misfortune; his pride grew with his abasement; his name was his crown; he had the air of saying: ‘Kill me, but you cannot kill the centuries written on my brow.’ If they had chiselled away at his coat of arms on the Louvre what did it matter; were they not engraved on the globe? Had Commisioners been sent to all corners of the world to efface them? Had they been erased in India, at Pondicherry, in the Americas, at Lima and in Mexico; in the East, at Antioch, Jerusalem, Acre, Cairo, Constantinople, Rhodes, and in the Morea; in the West, on the walls of Rome, on the ceilings of the Caserta and the Escorial, in the vaulting of spaces at Ratisbon and Westminster, in the escutcheons of all the kings? Had they scored them from the compass point, where they appear to announce the reign of the fleur-de-lis over scattered regions of the earth?

The obsession Louis XVIII acquired, with grandeur, antiquity, dignity, and the majesty of his race, provided Louis XVIII with a veritable empire. One felt his dominance; even Bonaparte’s generals confessed to it: they felt more intimidated before this powerless old man than before the terrible master who had commanded them in a hundred battles. In Paris, when Louis XVIII granted the triumphant monarchs the honour of dining at his table, he passed without question as the first of those Princes whose soldiers were camped in the courtyard of the Louvre; he treated them like vassals who were only doing their duty in leading their troops into the presence of their sovereign lord. In Europe, there was only one monarchy, that of France; the fate of the other monarchies was bound to the destiny of hers. All the royal lines were once linked to the race of Hugh Capet, and almost all are junior branches. Our ancient royal power was the ancient royalty of the world: from the banishment of the Capetians will date the era of the expulsion of Kings.

The more impolitic this pride of Saint Louis’ descendant (it became fatal in his heirs) the more it fuelled National pride: the French delight in seeing sovereigns who, conquered, carry their chains like men, in order to wear, as conquerors, the yoke of the race.

Louis XVIII’s unshakeable faith in his rank was the real power which granted him the sceptre; it is that faith, which, twice remembered, set a crown on his head regarding which Europe had not expected, and had not intended to exhaust its people and its wealth. The exile without an army was still there, after all those battles which he himself had not waged. Louis XVIII was the Legitimacy incarnate; it ceased to be visible once he had vanished.

Book XXIII: Chapter 9: THE HUNDRED DAYS IN GHENT, CONTINUED – Historical memories in Ghent – Madame the Duchesse d’Angouleme arrives in Ghent – Monsieur de Sèze – Madame the Duchesse de Lévis

BkXXIII:Chap9:Sec1

I took solitary walks in Ghent, as I do everywhere. The small boats slipped down the narrow canals, forced to traverse thirty or forty miles of meadows to reach the sea, as if they were sailing over the grass; they reminded me of the canals in the savage swamps among the wild grains of Missouri. Halting at the edge of the water, as the patches of white canvas sank below the skyline, my eyes wandered to the city steeples; history appeared in the clouds of the sky.

The inhabitants of Ghent rise against Henri de Châtillon, the French Governor; the wife of Edward III brings John of Gaunt into the world, root of the House of Lancaster; Artevelde exercises popular rule: ‘Good people, who is attacking you? Why are you so unhappy with me? How have I angered you? – You must die!’ shout the people: it is what the age always shouts at us. Then later I see the Dukes of Burgundy; the Spaniards arrive: then come the pacification, the sieges, and the taking of Ghent.

When I had dreamt my way through the centuries, the sound of a bugle or Scottish bagpipes woke me. I saw live soldiers hastening to rejoin their battalions buried deeper in Batavia: always destruction, power brought down; and, in the end, vanishing shades and past names.

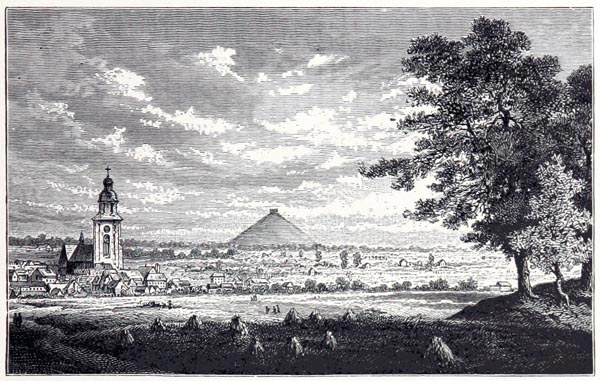

Maritime Flanders was one of the first areas occupied by the companions of Clodion and Clovis. Ghent, Bruges, and their surrounding countryside provided almost a tenth of the grenadiers of the Old Guard: that feared militia was drawn in part from the cradle of our forefathers, and it ended up being wiped out near to that cradle. Has not the Lys given its flower to our Kings’ armies?

Spanish style has left its imprint: the buildings in Ghent conjured for me those of Granada, lacking the skies of the Vega. A great city, almost without inhabitants, deserted streets, canals as deserted as the streets.twenty six islands created by canals, which are not those of Venice, an enormous artillery piece from the middle ages, these are what, in Ghent, replace the city of the Zegris, the Darro and the Xenil, the Generalife and the Alhambra: my old dreams, shall I never see you again?

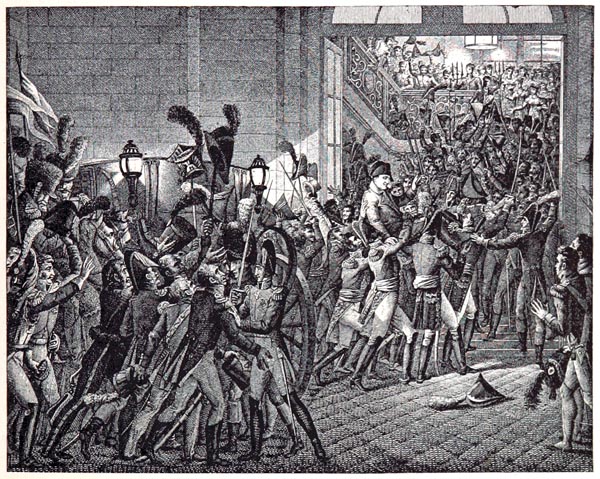

‘Ancien Château des Comtes de Flandre’

Vues Pittoresques des Principaux Monuments de la Ville de Gand - C. Auguste Voisin (p28, 1836)

The British Library

Madame the Duchesse d’Angoulême, embarking in the Gironde, reached us via England with General Donnadieu and Monsieur de Sèze, who had crossed the sea, his blue ribbon outside his coat. The Duke and Duchess of Lévis had followed the Princess: they threw themselves into the stagecoach and fled Paris by the Bordeaux road. The travellers and their companions talked politics: ‘That rascal, Chateaubriand, ‘said one of them, ‘is no fool! For three days, his carriage sat there, loaded up, in the courtyard: the bird has flown. It wouldn’t have been a bad thing if Napoleon had caught him!...’

Madame the Duchess of Lévis was a very beautiful, very fine person, as calm in spirit as Madame the Duchess de Duras was agitated. She never left Madame de Chateaubriand’s side; she was our assiduous companion in Ghent. No one has brought more peace to my life, something which I need greatly. The least troubled moments of my life are those I spent at Noisiel, at the home of that lady whose words and feelings only entered one’s soul to bring it serenity. I remember them with regret, those moments spent beneath the great chestnut-trees of Noisier! My mind soothed, my heart eased, I gazed at the ruins of the Abbey of Chelles, and the little lights of the boats moored among the willows by the Marne. The memory of Madame de Lévis is, for me, one of autumnal evening silence.

She died a few years later; she is mingled with the dead, as with the source of all rest. I saw her lowered silently into her grave in the cemetery of Père-Lachaise; she was placed higher than Monsieur de Fontanes, where he sleeps by his son Saint-Marcellin, killed in a duel. Thus, in bowing before the tomb of Madame de Lévis, I encounter two other sepulchres; a man cannot waken one grief without waking another: during the night, diverse flowers bloom, which only open in the dark.

To the affectionate goodness of Madame de Lévis towards me was joined the friendship of Monsieur the Duke de Lévis, the father: in future I ought only to count in generations. Monsieur de Levis was a fine writer; he had a copious and fecund imagination that felt for his noble race, seen at Quiberon, its ranks spread over the shore.

All shall not end there; it was an impulse of friendship which passed to the second generation. Monsieur the Duke de Lévis, the son, today attached to Monsieur the Comte de Chambord, is close to me; my hereditary affection to him is no less than my fidelity to his august father. The new, delightful, Duchesse de Lévis, his wife, unites with the great name of Aubusson the most brilliant qualities of mind and feeling: it is something to have lived where the graces imprint history with the passage of their un-wearying wings!

Book XXIII: Chapter 10: THE HUNDRED DAYS IN GHENT, CONTINUED – The Pavillon Marsan’s equivalent at Ghent – Monsieur Gaillard, Councillor to the Royal Court – A secret visit by Madame la Baronne de Vitrolles – A note from Monsieur – Fouché

BkXXIII:Chap10:Sec1

In Ghent, as in Paris, there was a Pavillon Marsan. Each day brought news to Monsieur, from France, which gave birth to interest or a stimulus to imagination.

Monsieur Gaillard, former member of the Oratory, councillor to the Royal Court in Paris, intimate friend of Fouché, arrived among us; he made himself known and was put in touch with Monsieur Capelle.

When I went to Monsieur’s, which was rarely, his entourage spoke to me in hushed tones and with many sighs of a man who (it must be admitted) has behaved marvellously well: he has hindered all of the Emperor’s operations; he defended the Faubourg St Germain, etc, etc, etc. The faithful Marshal Soult was the object of Monsieur’s predilection too, and after Fouché, the most loyal man in France.

One day, a carriage arrived at the door of my inn, and I saw Madame the Baronne de Vitrolles emerge: she was arriving charged with powers by the Duc d’Otrante. She brought a note in Monsieur’s own hand, in which the Prince declared that he would preserve an eternal gratitude towards those who had saved Monsieur de Vitrolles. Fouché needed no more; armed with this note, he was sure of his future in the event of a second Restoration. From that moment there was no longer any question in Ghent of the immense obligation owed to the excellent Monsieur Fouché of Nantes, or of the impossibility of returning to France except through the goodwill of this keeper of the law: the only problem was how to make this new Redeemer of the Monarchy acceptable to the King.

After the Hundred Days, Madame de Custine pressed me into dining with Fouché at her house. I had met him one before, six months previously, regarding the sentence passed against my poor cousin Armand. The former Minister knew that I had opposed his nomination at Roye, Gonesse, and Arnouville; and as he supposed I possessed some power, he wanted to make peace with me. The best of him was shown in the death of Louis XVI: he was a regicide in all innocence. Verbose, like all the revolutionaries, threshing the air with empty phrases, he churned out a mass of commonplace stuff about destiny, necessity, the law of things, mingling with this nonsensical philosophy other nonsense concerning the advance and progress of society, impudent maxims benefiting the strong in favour of the weak; finding no fault with bold confessions regarding the rightness of success, the worthlessness of severed heads, the fair-mindedness of those who prosper, the unfair attitudes of those who suffer, affecting to speak casually and indifferently of the most terrible disasters, as a genius above such stupidities. There escaped from him, concerning everything, not one choice idea, or remarkable insight. I left shrugging my shoulders at crime.

Monsieur Fouché never forgave my dryness and the slightness of the effect he had on me. He thought I would be fascinated by seeing the blade of the fatal machine rising and falling in front of my eyes, as if it were some glory of Sinai; he imagined that I would think that lunatic a colossus who, speaking of the soil of Lyons, said: ‘This soil will be ploughed over; on the ruins of this proud and rebellious town will be raised scattered cottages which the friends of equality will hasten to inhabit. We shall have the energy and courage to cross vast graveyards of conspirators......The blood-stained corpses must be thrown into the Rhone, offering to its twin shores and its mouth the imprint of terror and the mark of the all-powerful people......We shall celebrate the victory of Toulon; tonight we will give two hundred and sixty rebels to the lightning-bolt.’

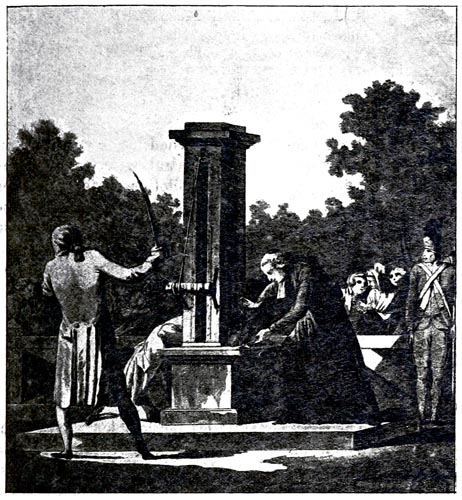

‘Machine Proposée à l’Assemblée Nationale par Mr. Guillotin pour le Supplice des Criminels’

Louis XVI. et la Révolution - Maurice Souriau (p299, 1803)

The British Library

His dreadful embellishments failed to impress me, since Monsieur de Nantes had mixed those Republican crimes with Imperial mud; that the sans-culotte, metamorphosed into a Duke, had twined the lantern-rope with the cord of the Legion of Honour did not seem to me to be either clever or grand. Jacobins detest men who think little of their atrocities and who scorn their murders; their pride is irritated like that of authors whose talent one contests.

Book XXIII: Chapter 11: EVENTS IN VIENNA – Negotiations by Monsieur de Saint-Léon, Fouché’s envoy – A proposal regarding Monsieur the Duc d’Orléans – Monsieur de Talleyrand – Alexander’s discontent with Louis XVIII – Various claims – La Besnardières’ report – An unexpected proposal to the Congress from Alexander: Lord Clancarthy causes it to fail – Monsieur de Talleyrand returns: his dispatch to Louis XVIII – The Declaration of Alliance, in truncated form in the official Frankfurt newspaper – Monsieur de Talleyrand wishes the King to return to France via the south-east provinces – Various visits to Vienna by the Prince of Benevento – he writes to me at Ghent: his letter

BkXXIII:Chap11:Sec1

At the same time that Fouché was sending Monsieur Gaillard to Ghent to negotiate with Louis XVI’s brother, his agents in Basle were talking to those of Prince Metternich regarding Napoleon II, and Monsieur de Saint-Léon, dispatched by that same Fouché, was arriving in Vienna to discuss the possible coronation of Monsieur the Duke d’Orléans. The friends of the Duke of Otranto could no more count on him than his enemies: on the return of the Legitimate Princes, he kept his old colleague Monsieur Thibaudeau on his list of exiles, while for his part Monsieur de Talleyrand erased from the list or added to the catalogue such and such a proscribed individual, according to whim. Had not the Faubourg Saint-Germain reason to believe in Monsieur Fouché?

Monsieur de Saint-Léon carried three notes to Vienna, one of which was addressed to Monsieur de Talleyrand: the Duke of Otranto proposed to the ambassador of Louis XVIII that he should promote, if he could see the way, the son of Philippe Egalité for the throne. What probity in negotiation! How happy one was to deal with such honest men! Yet we have admired them, poured incense over them, blessed their Seal; we have paid court to them; we have called them Milord! That explains the present age. In addition, Monsieur de Montrond arrived, following Monsieur de Saint-Léon.

Monsieur the Duke of Orléans was not conspiring in fact, only by consent; he left intrigue to those of revolutionary affinities: what a lovely society! In the depths of the woods, the plenipotentiary of the King of France leant an ear to Fouché’s overtures.

BkXXIII:Chap11:Sec2

Regarding Monsieur de Talleyrand’s ‘arrest’ at the Barrière d’Enfer, I have mentioned the objective that Monsieur de Talleyrand had possessed, till then, regarding the ‘Regency’ of Marie-Louise: he was forced to deviate from it, in the event, by the presence of the Bourbons; but he was always ill at ease; it seemed to him that, under the heirs of Saint Louis, a married bishop was never sure of his place. Thus the idea of substituting the cadet branch for the elder branch amused him, and more so because he had previously had relations with the Palais-Royal.

Taking part, without however revealing his hand completely, he hazarded a few words to Alexander regarding Fouché’s project. The Tsar had lost interest in Louis XVIII: the latter had offended him in Paris by affecting a superiority of race; he had also offended him by rejecting the idea of the Duc de Berry marrying one of the Emperor’s sisters; the Princess was refused for three reasons: she was a schismatic; she was not of an ancient enough line; she was from a family with a history of madness: reasons which were inadequate, were expedients, and which when they became known triply offended Alexander. As a final matter for complaint against the old sovereign of exile, the Tsar objected to the proposed alliance between England, France and Austria. Moreover, it seemed that the succession was an open question; the whole world claimed its inheritance from Louis XIV’s sons: Benjamin Constant, in the name of Madame Murat, pleaded the rights Napoleon’s sister believed she had to the Kingdom of Naples; Bernadotte cast a distant gaze on Versailles, apparently because the King of Sweden came from Pau.

La Besnardière, Head of Section in the Foreign Office, called on Monsieur de Caulaincourt; he had with him a bound report, On the Grievances and Contradictions in France, aimed at the Legitimacy. The attack having been launched, Monsieur de Talleyrand found the means to communicate the report to Alexander; annoyed and volatile, the autocrat was struck by La Besnardière’s pamphlet. Suddenly, in full Congress, and to everyone’s astonishment, the Tsar asked if there were not matter for consideration in an examination of the extent to which Monsieur the Duke of Orléans might suit France and Europe in the role of king. It was perhaps one of the most amazing actions of those extraordinary times, and perhaps the more extraordinary in that the matter had been spoken of so little. (A pamphlet which appeared, entitled: Lettres de l’étranger, which seems to have been written by an able and well-versed diplomat, lays out the nature of that strange Russian attempt at negotiation in Vienna. Note: Paris, 1840) Lord Clancarty ensured the Russian proposal was turned down: his Lordship declared that they did not have the authority to handle such a serious issue: ‘For my part,’ he said, giving a personal opinion ‘I think that setting Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans on the throne of France would be to replace a military usurpation by a domestic usurpation, more dangerous to monarchy that all other usurpations.’ The members of the Congress went off to dine and marked the page of their protocols at which they had stopped with the sceptre of Saint Louis, as if with a straw.

Given the obstacle the Tsar had encountered, Monsieur de Talleyrand did an about face: reckoning on word of the attempted coup getting out, he sent an account to Louis XVIII (in a dispatch I have seen bearing the number 25 or 27) of that odd session of Congress (It is claimed that in 1830, Monsieur de Talleyrand removed his correspondence with Louis XVIII from the Crown’s private archives, just as he had removed everything he had written concerning the death of the Duc d’Enghien and the business with Spain from Bonaparte’s archives. Note: Paris, 1840): he thought himself obliged to inform His Majesty of so outrageous a step, since that news, he said, would not be long in reaching the ears of the King: singularly naïve on the part of Monsieur le Prince de Talleyrand.