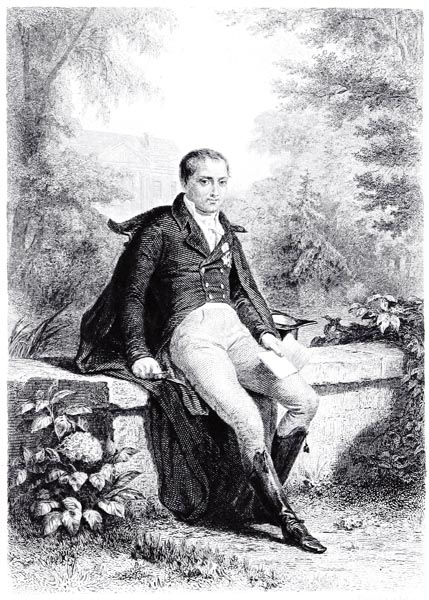

François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXII: Napoleon - Defeat and Exile: to 1815

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXII: Chapter 1: The ills of France – Forced celebrations – A sojourn in my Valley – The Legitimacy awakes

- Book XXII: Chapter 2: The Pope at Fontainebleau

- Book XXII: Chapter 3: Defections – The deaths of Lagrange and Delille

- Book XXII: Chapter 4: The Battles of Lützen, Bautzen and Dresden – Reverses in Spain

- Book XXII: Chapter 5: The Campaign in Saxony, or the Campaign of The Poets

- Book XXII: Chapter 6: The Battle of Leipzig – Bonaparte’s return to Paris – the Treaty of Valençay

- Book XXII: Chapter 7: The Legislature convened – Then adjourned – The Allies cross the Rhine – Bonaparte’s anger – New Year’s Day 1814

- Book XXII: Chapter 8: The Pope set at liberty

- Book XXII: Chapter 9: Notes which became the pamphlet: De Bonaparte et des Bourbons – I take an apartment on the Rue de Rivoli – The notable Campaign of 1814 in France

- Book XXII: Chapter 10: I begin printing my pamphlet – A note from Madame de Chateaubriand

- Book XXII: Chapter 11: War at the gates of Paris – The appearance of Paris – Battle at Belleville – The Flight of Marie-Louise and the Regency – Monsieur de Talleyrand remains in Paris

- Book XXII: Chapter 12: The proclamation of General the Prince Schwarzenberg – Alexander’s speech – The capitulation of Paris

- Book XXII: Chapter 13: The Allies enter Paris.

- Book XXII: Chapter 14: Bonaparte at Fontainebleau – The Regency at Blois

- Book XXII: Chapter 15: The publication of my pamphlet – De Bonaparte et Des Bourbons

- Book XXII: Chapter 16: The Senate issue the Decree of Deposition

- Book XXII: Chapter 17: The Hôtel de la Rue Saint-Florentin – Monsieur de Talleyrand

- Book XXII: Chapter 18: The Proclamations of the Provisional Government – The Constitution proposed by the Senate

- Book XXII: Chapter 19: The arrival of the Comte d’Artois – Bonaparte’s abdication at Fontainebleau

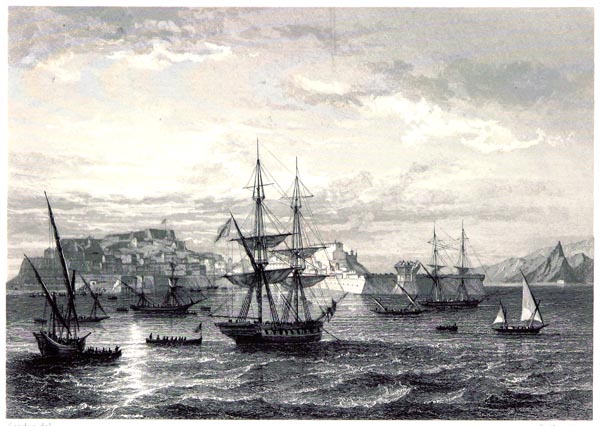

- Book XXII: Chapter 20: Napoleon’s Journey to the Isle of Elba

- Book XXII: Chapter 21: Louis XVIII at Compiègne – His entry into Paris – The Old Guard – An Irreparable Fault – The Declaration of Saint-Ouen – The Treaty of Paris – The Charter – Departure of the Allies

- Book XXII: Chapter 22: The first year of the Restoration

- Book XXII: Chapter 23: Were the Royalists to blame for the Restoration?

- Book XXII: Chapter 24: First Minister – I publish Réflexions Politiques – Madame la Duchesse de Duras – I am named as Ambassador to Sweden

- Book XXII: Chapter 25: The exhumation of the remains of Louis XVI – My first 21st of January at Saint-Denis

- Book XXII: Chapter 26: The Island of Elba

Book XXII: Chapter 1: The ills of France – Forced celebrations – A sojourn in my Valley – The Legitimacy awakes

BkXXII:Chap1:Sec1

When Bonaparte arrived, preceded by his bulletin, there was general consternation. ‘The Empire,’ says Monsieur Ségur, ‘could only count on men aged by time or war, and children! Almost all the mature men, where were they? Women’s tears, mothers’ cries, spoke clearly enough! Bowed laboriously over the land, which without them would have remained untilled, they cursed the war he personified.’

Returning from the Berezina, there was no less of a requirement to dance: that is what one learns from the Souvenirs pour servir à l’histoire, of Queen Hortense. One was forced to go to the ball, death in one’s heart, weeping inwardly for relatives or friends. Such was the dishonour to which despotism had condemned France: one saw in the salons what one met with in the streets, creatures distracting themselves from their own lives by singing out their misery to divert the passers-by.

‘La Reine Hortense’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p175, 1845)

The British Library

For three years I had been in retirement at Aulnay: from my pine-clad hill, in 1811, I had followed with my eyes the comet which during the night fled towards the wooded horizon; she was beautiful and melancholy, and, like a queen, drew her long train behind her. Whom did she seek, that lost stranger to our world? Towards whom did she make her way through the wastes of the sky?

On the 23rd of October 1812, sheltering for a moment in Paris, on the Rue des Saints-Pères, at the Hôtel Lavalette, Madame Lavalette, my hostess, being deaf and furnished with her long ear-trumpet, roused me: ‘Monsieur! Monsieur! Bonaparte is dead! General Malet has killed Hulin. All the powers that be are changed. The Revolution is over.’

Bonaparte was so beloved that for a while Paris was in a state of joy, except for the authorities who were left in an absurd limbo. A rumour had almost toppled the Empire. Escaping from prison at midnight a soldier was master of the world at daybreak; a fantasy was close to carrying off a formidable reality. The most moderate said: ‘If Napoleon is not dead, he will return chastened by his mistakes and reverses; he will make peace with Europe, and our remaining children will be saved.’ Two hours after his wife had spoken to me, Monsieur Lavelette entered to inform me of Malet’s arrest: it was no secret (that was his habitual phrase) that all was over. Day and night occurred simultaneously. I have related how Bonaparte received the news in a snowy field near Smolensk. The Senatus Consulte (of 12th of January 1813) put at the disposal of the returning Napoleon two hundred and fifty thousand men; inexhaustible France saw flow, from its blood through its wounds, fresh soldiers. Then a long-forgotten voice was heard; a few aged French ears thought they recognised the sound: it was the voice of Louis XVIII; it rose from the depths of exile. Louis XVI’s brother proclaimed the principles to be established one day by constitutional charter; the first aspiration towards liberty that emanated from our former kings.

Alexander, having entered Warsaw, addressed a proclamation to Europe: .............................

‘If the North will imitate the sublime example set by the Castilians, the world’s period of mourning is over. Europe, on the verge of falling prey to a monster, will recover its freedom and tranquillity. Let this blood-stained colossus who has menaced the continent with his endless criminality remain in the end merely a distant memory of horror and pity!’

That monster, that blood-stained colossus who menaced the continent with his endless criminality, had learnt so little from misfortune that barely escaped from the Cossacks he flung himself upon an old man whom he still held prisoner.

Book XXII: Chapter 2: The Pope at Fontainebleau

BkXXII:Chap2:Sec1

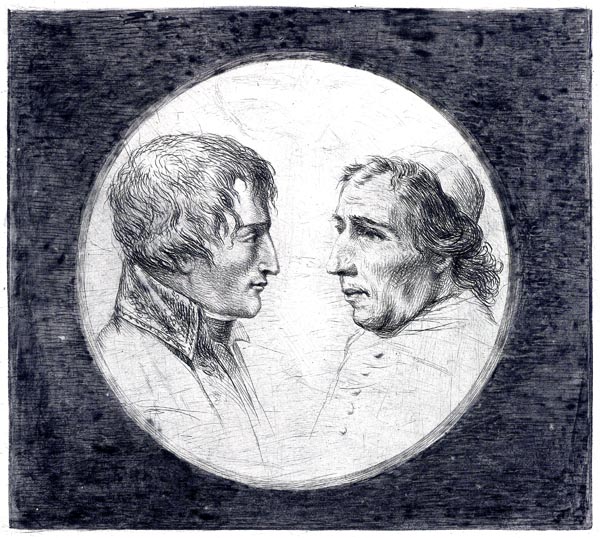

We saw the Pope’s abduction from Rome, his stay at Savona, then his detention at Fontainebleau. Discord held sway in the Sacred College: some Cardinals wished the Holy Father to resist for spiritual reasons, and they were ordered to only wear black garments; some were sent into exile in the provinces; some of the leading French clergy were imprisoned at Vincennes: other Cardinals assented to the Pope’s total submission; they retained their red garments; it was a second visitation of the Candlemas candles.

While at Fontainebleau the Pope obtained some respite from the obsession with Red Cardinals, he walked alone in the galleries of Francis I; he recognised some remnants of arts which recalled the Holy City, and from his windows he could see the pine trees that Louis XVI had planted facing the gloomy apartments where Monaldeschi was assassinated. From this deserted place, like Jesus, he could take pity on the kingdoms of the earth. The septuagenarian, half-dead, Bonaparte himself visiting to torment him, mechanically signed that Concordat of 1813, which he protested against as soon as Cardinals Pacca and Consalvi arrived.

When Pacca rejoined the captive with whom he had left Rome, he thought to find a large crowd around the royal jail; he only found a few servants in the courtyards and a sentry on duty at the top of the Horseshoe Staircase. The windows and doors to the palace were closed: in the first antechamber to the apartments he found Cardinal Doria, in the other rooms stood several French bishops. Pacca was announced to His Holiness: he was standing motionless, pale, hunched, thin, his eyes sunken in his head.

‘Sentier de la Forêt de Fontainebleau — Dessin d'Après Desjobert’

La France et les Colonies, Illustré - Onésime Reclus (p143, 1887)

The British Library

The Cardinal told him that he had hurried his journey to throw himself at his feet. Then the Pope said: ‘These Cardinals dragged us to the table and made us sign.’ Pacca withdrew to the apartment prepared for him, overcome by the solitariness of the residence, the expressionless eyes, the despondent faces, and the profound sorrow imprinted on the Pope’s visage. Returning to His Holiness, he ‘found him’ (he himself speaks) ‘in a state worthy of compassion and in fear of his life. He was overwhelmed by an inconsolable sadness when speaking of what had taken place; that tormenting thought stopped him sleeping and prevented him taking the nourishment which sufficed to keep him from death: - “As to that”, he said, “I shall die mad like Clement XIV.”’

In the silence of those empty galleries, where the voices of Saint Louis, Francis I, Henry IV, and Louis XIV were no longer heard, the Holy Father, spent several days composing and copying the letter which was to be sent to the Emperor. Cardinal Pacca carried the document about hidden in his robes, at some risk since the Pope had added a few lines to it in his own handwriting. The work done, the Pope gave it, on the 24th of May 1813, to Colonel Lagorce and asked him to take it to the Emperor. At the same time he read a short speech to the various Cardinals who were present: he considered the brief he had issued at Savona and the Concordat of 25th January as null and void. ‘May the Lord be blessed,’ the speech read, ‘who has not removed his mercy from us! He has simply wished to humble us through salutary confession. Let us then be humbled for the good of our soul; to Him, through all the centuries, exaltation, honour and glory!

From the Palace of Fontainebleau, the 24th of March 1813.’

No finer decree has ever issued from that Palace. The Pope’s conscience was eased, the martyr’s expression became serene; his smile and his lips regained their charm, and his eyes closed in sleep.

At first Napoleon threatened to make the heads of some of those priests at Fontainebleau leap from their shoulders; he considered declaring himself head of State religion; then, regaining his temper, he pretended to know nothing of the Pope’s letter, But his fortunes were in decline. The Pope, from an order of poor monks, dragged by misfortune among the crowd, seemed to have taken on the great mantle of Tribune of the People once more, and given the signal for the deposition of the oppressor of public freedom.

Book XXII: Chapter 3: Defections – The deaths of Lagrange and Delille

BkXXII:Chap3:Sec1

Ill fortune brings betrayal with it but does not justify it; in March of 1813, Prussia allies itself with Russia at Kalisz. On the 3rd of March, Sweden signs a treaty with the Court of St James; she is obliged to provide thirty thousand men, Hamburg is evacuated by the French, Berlin entered by Cossacks, Dresden occupied by the Russians and Prussians.

The defection of the Confederation of the Rhine is imminent. Austria adheres to its alliance with Russia and Prussia. The war in Italy re-commences and Prince Eugène is sent there.

In Spain, the English army defeats Joseph at Vittoria; the paintings stripped from the churches and palaces fall into the Ebro; I have seen them in Madrid and at the Escorial; I had seen them when they were restored in Paris: the waves and Napoleon had passed over these Murillos and Raphaels, velut umbra (like a shadow). Wellington, ever advancing, defeats Soult at Roncesvalles: our noblest memories formed the background to the scene of our later fate.

On the 14th of February, at the opening of the Legislature, Bonaparte had declared that he had always wanted peace and that it was essential for the world. This lie no longer emanated from him. Moreover there was little sympathy for the grief of France from the lips of one who called us his subjects: Bonaparte exacted suffering from us, as a tribute due to him.

On the 3rd of April, the Senate (Conservateur) added a hundred and eighty thousand combatants to those it had already allocated: an extraordinary levy of men in the midst of the regular levies. On the 10th of April, Lagrange was taken; the Abbé Delille died some days later. If nobility of feeling outweighs depth of thought in Heaven, the singer of La Pitié is nearer the throne of God than the author of the Theory of Analytic Functions. Bonaparte left Paris on the 15th of April.

Book XXII: Chapter 4: The Battles of Lützen, Bautzen and Dresden – Reverses in Spain

BkXXII:Chap4:Sec1

The levies of 1812, following one another, have halted in Saxony. Napoleon arrives. The honours of the former lost host are handed to two hundred thousand conscripts who fight like the grenadiers of Marengo. On the 2nd of May, the battle of Lützen is won: Bonaparte, in these fresh battles, scarcely used artillery any longer. Entering Dresden, he tells the inhabitants: ‘I am not unaware of the joy in which you indulged when the Emperor Alexander and the King of Prussia entered your walls. We can still see on the cobblestones the remains of the flowers that your young girls scattered in the path of those monarchs.’ Did Napoleon remember the young girls of Verdun? It was in the days of his youth.

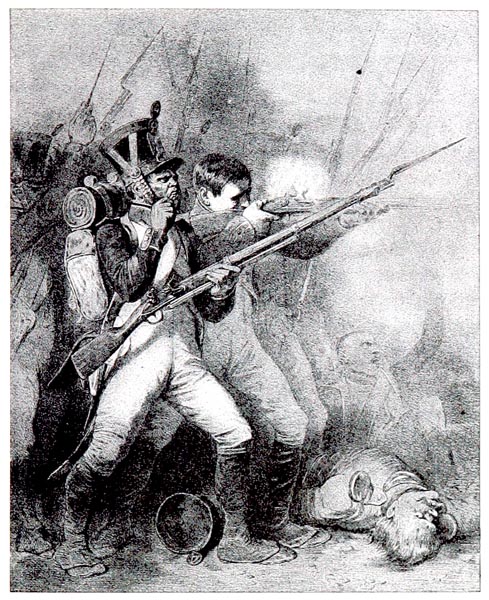

‘Campagne de Saxe, Les Conscrits de 1813. Peint par Raffet, Lithographié par Llanta’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p843, 1888)

The British Library

At Bautzen, another triumph, but one after which the Commander of the Engineers, Kirgener, and Duroc, the Grand Marshal of the Palace, were buried. ‘There is a future life,’ the Emperor told Duroc, ‘we will meet again.’ Did Duroc care much about that meeting?

On the 26th and 27th of August, they reached the Elbe, on fields already famous. Returned from America, having seen Bernadotte in Stockholm, and Alexander in Prague, Moreau had both legs carried away by a cannonball, at Dresden, at the side of the Russian Emperor: a familiar outcome of Napoleonic destiny. They learned, in the French camp, of the death of the victor of Hohenlinden, by means of a stray dog, on whose collar was inscribed the name of the new Turenne; the animal, living on without its master, ran here and there among the dead: Te, janitor Orci (You, oh guardian of the Underworld)!

The Prince of Sweden, who had become the Generalissimo of the Army of North Germany, had addressed a proclamation to his soldiers on the 15th of August:

‘Soldiers, the same feelings that guided the French in 1792, and which led them to unite, and combat the armies entering their territory, must now direct your valour against one who, having invaded the soil which bore you, still enslaves your brothers, your wives and your children.’

Bonaparte, incurring universal disapproval, set himself against liberty which attacked him on all sides, in all its forms. A Senatus-Consulte of the 28th of August annulled the judgement of a jury at Anvers: a very minor infraction, doubtless, of the rights of citizens, after the arbitrary enormities employed by the Emperor; but at the heart of the law is a sacred freedom whose cry must be heard: that oppression practised against a jury made more noise than the many other oppressions to which France fell victim.

Finally, in the south, the enemy trod our soil; the English, Bonaparte’s obsession and the source of almost all his mistakes, crossed the Bidasoa on the 7th of October: Wellington, the man of destiny, was the first to set his foot on the soil of France.

Insisting on remaining in Saxony, despite Vandamme’s capture in Bohemia and Ney’s defeat near Berlin by Bernadotte, Napoleon returned to Dresden. Then the Landsturm was levied; a patriotic war, similar to that which had freed Spain, was being organised.

Book XXII: Chapter 5: The Campaign in Saxony, or the Campaign of The Poets

BkXXII:Chap5:Sec1

The battles of 1813 have been referred to as the Campaign in Saxony: they would be better named the Campaign of Young Germany or the Campaign of the Poets. To what despair had Bonaparte not reduced us by his oppression, that while watching our own blood flow, we could yet deny a gesture of support for generous youth taking up the sword in the name of freedom? Each of those battles was a protest on behalf of national rights.

In one of his proclamations, dated from Kalisz on the 25th of March 1813, Alexander called the people of Germany to arms, promising them, in the name of his royal ‘brothers’, free institutions. This was the signal for open activity by the Burschenschaft, which had already been formed in secret. The German universities re-opened; they set aside sorrow in order to think only of reparation for their injuries: ‘Let mourning and tears be brief, grief and distress long-lasting.’ said the ancient Germans, ‘it is right for women to weep, for men to remember: ‘Lamenta ac lacrymas cito, dolorem et tristitiam tarde ponunt. Feminis lugere honestum est, viris meminisse.’ Then the young Germans hastened to free their country; then they were in a hurry, those Germans, allies of the Empire, whom ancient Rome aided, in supplying them with armour and spears, velut tela atque arma.

In Berlin, in 1813, Professor Fichte gave a lecture on duty; he spoke of the disasters which afflicted Germany, and finished his lecture with these words: ‘This course will be suspended until the end of the Campaign. We will continue it when our country is free, or we will die regaining our freedom.’ His young audience rise to their feet in acclamation: Fichte descends from his seat, passes through the crowd, and goes to enrol in a corps leaving for the army.

All Bonaparte has scorned and insulted becomes a danger to him: intellect enters the lists against brute force; Moscow is the flame by whose light Germany dons its harness: ‘To arms!’ the Muse cries. ‘The Phoenix of Russia has soared from its pyre!’ That Queen of Prussia, so defenceless and so beautiful, whom Napoleon showered his clever insults upon, is transformed into an implored and imploring shade: ‘How softly she sleeps!’ sing the bards, ‘Ah, may you sleep until that day when your people wash away the rust of their swords with blood! Wake, then! Wake! Be our angel of liberty and vengeance!’

Körner had only one fear, that of dying in prose: ‘Poesy! Poesy!’ he exclaimed, ‘bring me death at the break of day!’

He composed, in camp, the hymn of The Lyre and the Sword.

THE KNIGHT.

‘Tell me fine sword, sword at my side, why the light of your glance is so ardent today? You glance at me with the gaze of love, fine sword, sword that is my joy. Huzza!’

THE SWORD.

‘It’s because a brave knight bears me along: that is what inflames my glance; for I am the strength of a free man. Huzza!’

THE KNIGHT.

‘Yes, my blade, yes, I am a free man, and I love you from the depths of my heart: I love you as if you were my betrothed; I love you like a dear mistress.’

THE SWORD.

‘And I, I give myself to you! To you my life, to you my soul of steel! Oh! If we are betrothed, when will you say: Come to me, come my dear mistress?’

Might one not believe one is listening to one of those Northern warriors, one of those men of battle and solitude, of whom Saxo Grammaticus wrote: ‘He fell, smiling: and died.’

It is not the cool enthusiasm of a Skald certainly: Körner had his sword by his side; handsome, fair, young, an Apollo on horseback, he sang of the darkness like an Arab in the saddle; his maoual (chant), while charging the enemy, was accompanied by the sound of his galloping mount. Wounded at Lützen, he dragged himself into the woods, where some peasants found him; he emerged to die on the plains of Mecklenburg, at the age of twenty-one: he fled the arms of a woman he loved, and forsook all the delights of life. ‘Women take pleasure,’ said Tyrtaeus, ‘in contemplating the radiant and upright man: he is no less handsome if he falls in the front ranks.’

The new followers of Arminius, raised in the school of Greece, had a common national anthem: when these students abandoned the peaceful avenues of science for the field of battle, the silent joys of study for the noisy perils of war, Homer and the Niebelungenlied for the sword, with what did they counter our hymn of blood, our Revolutionary canticle? These stanzas full of religious feeling, and human sincerity:

‘Where is Germany? Name that great land to me! Wherever the German language sounds, and our German song is heard praising God: there is Germany.

Germany is the land where a shake of the hand suffices as a pledge, where simple honesty shines in every glance, where affection glows in every heart.

O God, in Heaven, cast your eyes on us: grant us that purity of spirit, truly German, so that we may be loyal and true. There, is a German’s country, all that land is his land.’

These college friends, now companions in arms, do not join clubs where Septembrists vow to murder with the knife: loyal to their poetic imaginings, to historical tradition, to the cult of the past, they make an old castle, an ancient forest, a defensive sanctuary of the Burschenschaft. The Queen of Prussia becomes their patroness, instead of the Queen of Night.

At the summit of a hill, among the ruins, the soldier-scholars, with their officer-professors, see revealed the pinnacle of their beloved university halls: moved by memories of their learned past, and by this sight of the sanctuary of their studies and the games of their youth, they swear to free their country, as Melchthal, Fürst and Stauffacher had pronounced their triple oath in sight of the Alps, immortalised by them, and depicted by them. The German spirit has something mystical about it; Schiller’s Thekla for example is a Teutonic daughter gifted with second-sight and imbued with a divine element. The Germans today worship liberty with an indefinable mysticism, just as they once designated the secret depths of the forests as God: Deorumque nominibus appellant secretum illud. The man whose life was a dithyramb of action only fell when the poets of Young Germany had sung, and taken up the sword, against their rival Napoleon, the armed poet.

Alexander was worthy of being the herald sent to the young Germans: he shared their elevated feelings, and he was in a position of power which made their plans achievable; but he let himself be made fearful by the fears of the monarchs who surrounded him. Those monarchs had never kept their promises; they gave their people nothing in the way of benevolent political institutions. The children of the Muse (the flame by whom the inert mass of soldiers had been animated) were thrust into dungeons in recompense for their devotion and their noble beliefs. Alas, the generation that brought the Teutons freedom had vanished; there were only old worn out political incumbents in Germany. They praised Napoleon as a great man at every opportunity, so that their present admiration might excuse their past abasement. In that foolish enthusiasm for the man which made governments continue to grovel when they been whipped, they barely remembered Körner: ‘Arminius, Germany’s liberator,’ says Tacitus, ‘was unknown to the Greeks who only admired themselves, and little celebrated among the Romans whom he had vanquished; but the barbarous nations still sing of him, caniturque barbaras apud gentes.’

Book XXII: Chapter 6: The Battle of Leipzig – Bonaparte’s return to Paris – the Treaty of Valençay

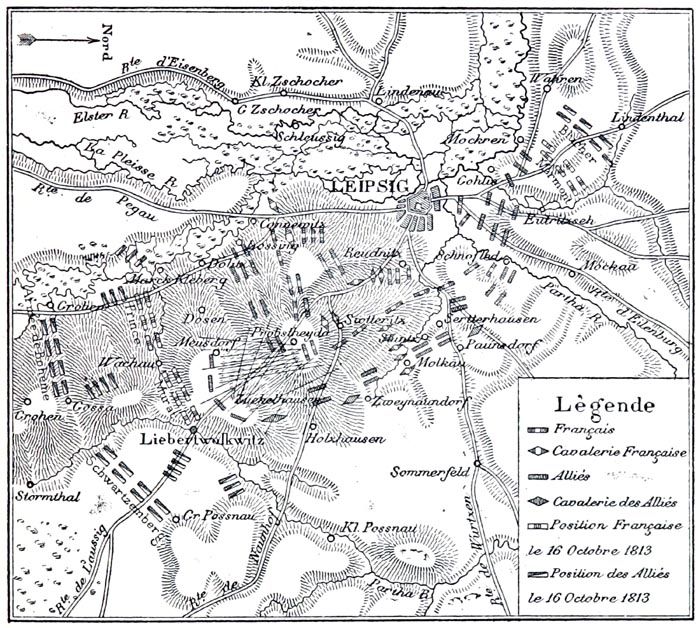

‘Plan de la Bataille de Leipzig, dite la Bataille des Nations’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p863, 1888)

The British Library

BkXXII:Chap6:Sec1

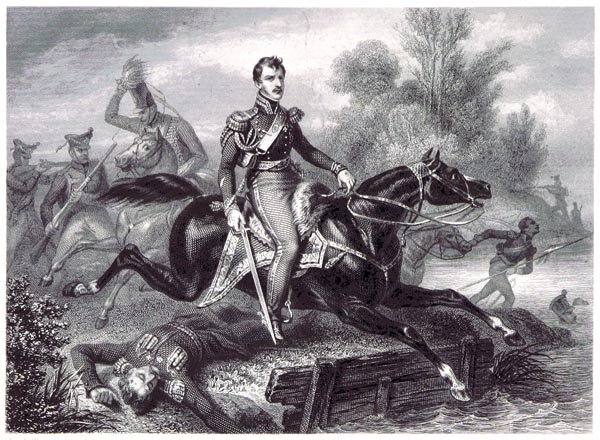

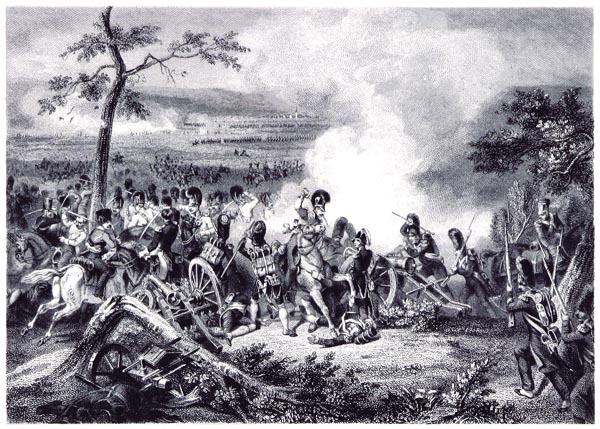

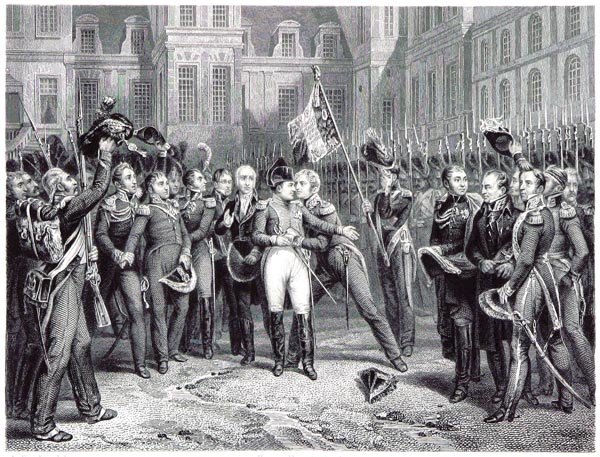

On the 18th and 19th of October 1813 the battle took place on the fields of Leipzig that the Germans call the Battle of the Nations. Towards the end of the second day, the Saxons and the Wurtenbergers, deserting Napoleon’s camp beneath the banner of Bernadotte, decided the outcome of the action: victory was tarnished by betrayal. The Prince of Sweden, the Emperor of Russia, and the King of Prussia entered Leipzig through three different gates. Napoleon, having experienced a crushing defeat, retreated. Since he knew nothing of sergeant’s retreats, as he once said, he blew the bridges behind him. Prince Poniatowski, twice wounded, was drowned in the Weisse Elster: Poland fell with its last defender.

‘Poniatowski - Mort en Traversant l'Elster, le 19 octobre 1813’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p165, 1845)

The British Library

Napoleon did not halt till Erfurt: from there his bulletin announced that his army, ever victorious, had met with a great battle: Erfurt, not long before, had seen Napoleon at the height of his prosperity.

Finally, the Bavarians, following the other deserters from ill fortune, tried to annihilate the rest of our soldiers at Hanau. Wrède was defeated by the Guards of Honour alone: a few conscripts, already veterans, treated him ruthlessly; they saved Bonaparte and took up position behind the Rhine. Arriving in Mainz as a fugitive, Napoleon, returned to Saint-Cloud on the 9th of November; the indefatigable De Lacépède arrived to tell him: ‘Your Majesty has overcome all.’ Monsieur de Lacépède spoke appropriately concerning oviparous creatures; but could not keep on his feet.

‘Bataille de Hanau’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p213, 1845)

The British Library

Holland regained its freedom, and recalled the Prince of Orange. On the 1st of December the Allied Powers declared: ‘that they were not making war against France, only against the Emperor, or rather against that domination he had exercised for too long, beyond the borders of his Empire, to the detriment of Europe and France.’

As the moment approached when we would be shut in our former territory once more we asked what purpose the upheaval in Europe, and the massacre of so many millions of men, had served? Time swallows us and continues tranquilly on its course.

By the Treaty of Valençay of the 11th of December, the wretched Ferdinand VII was returned to Madrid: thus ended, obscurely and in haste, that criminal enterprise in Spain, the primary cause of Napoleon’s fall. One can always go to the bad, one can always kill people, including a king; but the way back is difficult: Jacques Clément repaired his sandals for the journey to Saint-Cloud, his colleagues, smiling, questioned how long his handiwork would last: ‘Long enough for the road I travel, ‘ he replied, ‘I am obliged to go, not to return.’

Book XXII: Chapter 7: The Legislature convened – Then adjourned – The Allies cross the Rhine – Bonaparte’s anger – New Year’s Day 1814

BkXXII:Chap7:Sec1

The Legislature assembled on the 19th of December 1813. Astounding on the field of battle, remarkable in his councils of State, Bonaparte was less effective in politics: the language of liberty he knew nothing of; if he wished to express congenial feelings, or paternal sentiments, he was moved in an inappropriate way, and masked a lack of feeling with tender words. ‘My heart,’ he told the Legislature, ‘needs the presence and affection of my subjects. I have never been seduced by prosperity; adversity will find me immune to its sufferings. I have conceived and executed great schemes for the prosperity and good of the world. Monarch and father, I feel that peace enhances the security of thrones and that of families.’

An official Moniteur article said, in July 1804, that under the Empire, France would never extend beyond the Rhine, and its armies would no longer cross it.

The allies crossed that river on the 21st of December 1813, from Basle to Schaffhausen, with more than a hundred thousand men; on the 31st of the same month, the Army of Silesia commanded by Blücher, crossed in turn, from Mannheim to Coblentz.

By order of the Emperor, the Senate and the Legislature appointed two commissions charged with examining documents related to negotiation with the Coalition powers; foresight on the part of a power which, denying consequences which had become inevitable, wished to transfer the responsibility to another authority.

The Legislative commission, presided over by Monsieur Lainé, dared to state ‘that steps towards peace would be assured of their effect if the French were convinced that their blood would only be shed in order to defend the country and laws which protect them; that His Majesty must be implored to maintain the whole and constant execution of the laws which guarantee to the French the rights of liberty, security, and property, and to the nation the free exercise of its political rights.’

The Minister of Police, the Duke of Rovigo, has all traces of their report removed; a decree of the 31st December adjourns the Legislature; the doors of the room are locked. Bonaparte considered the members of the Legislative commission as agents in the pay of England: ‘The said Lainé, ‘he remarked, ‘is a traitor who corresponds with the Prince Regent through the intermediary De Sèze; Raynouard, Maine de Biran, and Flaugergues are dissidents.’

The soldier was astonished not to be encountering those Poles he had abandoned, who, drowning themselves in order to obey his orders, still shouted: ‘Long Live the Emperor!’ He called the report of the commission a motion passed by a Jacobin club. There is not a speech of Bonaparte’s in which his aversion for the Republic which spawned him does not emerge; though he detested its crimes less than its freedoms. Regarding this same report, he added: ‘Do they want to re-establish the sovereignty of the people? Well, in that case, I constitute the people; since I intend always to be wherever sovereignty resides.’ No despot has ever revealed his character more clearly: it is Louis XIV’s phrase re-visited: ‘The State: that is I.’

At the reception on New Year’s Day 1814, a scene was anticipated. I knew someone attached to the Court, who proposed to take his sword along in his hand, just in case. Nevertheless Napoleon went no further than violent words, though he uttered them in a quantity that even caused some embarrassment to his halberdiers: ‘Why,’ he shouted, ‘talk about these domestic matters in front of all Europe? Dirty linen should be washed in private. What is a throne? A piece of wood covered with a piece of cloth: all depends on who is seated there. France has more need of me than I of her. I am one of those men one can kill, but not dishonour. We will have peace in three months, or the enemy will be driven from our territory, or I will be dead.’

Bonaparte was accustomed to wash French linen in blood. In three months there was no peace, the enemy was not driven from our territory, and Bonaparte had not lost his life: death was not yet his fate. Overwhelmed by so many problems and the obstinate ingratitude of the master she had bestowed on herself, France saw herself invaded with the motionless stupor born of despair.

An Imperial decree mobilised one hundred and twenty-one battalions of the National Guard; another decree created a Regency Cabinet, presided over by Cambacérès and composed of Ministers, at whose head the Empress was installed. Joseph, an available monarch, back from Spain with his spoils, was made Commandant General of Paris. On the 25th of January 1814, Bonaparte left his palace for the army, off to light a brilliant flame as he faded away.

Book XXII: Chapter 8: The Pope set at liberty

BkXXII:Chap8:Sec1

A few days before, the Pope had regained his freedom; the hand that went to him bearing chains was forced to break those irons he had bestowed: Providence had altered their fates, and the wind which blew in Napoleon’s face drove the allies towards Paris.

Pius VII, informed of his deliverance, hastened to make a brief prayer in the chapel of Francis I; he climbed into a carriage and traversed that forest in which, according to popular tradition, the great hunter Death could be seen when a king was about to visit Saint Denis.

The Pope travelled under the surveillance of an officer of the gendarmerie who followed him in a second carriage. At Orléans, he learnt the name of the town he was entering.

He followed the Southern route to the acclamations of the people of those provinces which Napoleon would soon pass through, scarcely feeling safe despite the guardianship of foreign officers. His Holiness was delayed in his journey by his oppressor’s very fall: the authorities had ceased to function; no one was obeyed; an order penned by Bonaparte, an order which twenty-four hours earlier would have bowed the noblest head and made a kingdom topple, was worthless paper: Napoleon lacked those remaining moments of power in which to protect the captive his power had persecuted. A provisional mandate of the Bourbons was needed to ensure that Pontiff was set free who had placed their crown on an alien head: what a confusion of destinies!

Pius VII travelled among hymns and tears, to the sound of bells, to cries of: ‘Long live the Pope! Long live the Head of the Church!’ They brought him, not the keys of towns, capitulations drenched with blood and obtained by murder, rather they brought to the sides of his carriage the sick for him to heal, and newly married couples for him to bless; he said to the former: ‘May God console you!’ He extended his peace-giving hands over the latter; he touched little children in their mother’s arms. Only those unable to walk remained in the towns. The pilgrims spent the night in the fields to await the arrival of an old freed priest. The peasants, in their simplicity, thought that the Holy Father resembled Our Lord; Protestants, moved, said: ‘There is the greatest man of his century. Such is the grandeur of a truly Christian society, where God ceaselessly mingles with men; such is the superiority over the power of the sword and the sceptre of the power of humility, sustained by religion and misfortune.

Pius VII passed through Carcassonne, Béziers, Montpellier and Nîmes, to reach Italy once more. On the banks of the Rhine, it seemed as if the innumerable crusaders of Raymond of Toulouse were still passing in revue at Saint-Rémy. The Pope saw Nice again, Savona, Imola, witness of his fresh afflictions and the first mortifications of his life: one likes to weep where one has wept. In commonplace moments one remembers places or times of happiness. Pius VII travelled again his virtuous hours and his sufferings, as a man in memory reviews his faded passions.

At Bologna, the Pope was left in the hands of the Austrian authorities. Murat, Joachim-Napoléon, King of Naples, wrote to him on the 4th of April 1814:

‘Most Holy Father, the fortunes of war having rendered me master of the States which you possessed when you were forced to leave Rome, I do not hesitate to return them to your authority, renouncing all my rights of conquest over these lands, in your favour.’

What remained to Joachim and Napoleon at their deaths?

‘Double portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte and Pope Pius VII’

Bernard Coclers, c. 1801 - c. 1804

The Rijksmuseum

The Pope no sooner arrived in Rome than he offered refuge to Napoleon’s mother. The legates had retaken possession of the Eternal City. On the 23rd of May, in the fullness of spring, Pius VII saw the dome of Saint-Peter’s. He has told of shedding tears on seeing the sacred dome again. Preparing to enter the Porta del Populo, the Pontiff halted: twenty-two orphans dressed in white robes, and forty-five young girls carrying large gilded palm-leaves came forward singing hymns. The crowd shouted: ‘Hosanna!’ Pignatelli who had commanded the troops on the Quirinal when Radet took Pius VII’s Garden of Olives by assault, now led the procession of palms. At the same time that Pignatelli was changing roles, various noble perjurers, in Paris, were once more taking up their functions as grand-domestics, behind Louis XVIII’s armchair: prosperity was handed to us with slavery, as in former times a seigniorial estate was sold with its serfs.

Book XXII: Chapter 9: Notes which became the pamphlet: De Bonaparte et des Bourbons – I take an apartment on the Rue de Rivoli – The notable Campaign of 1814 in France

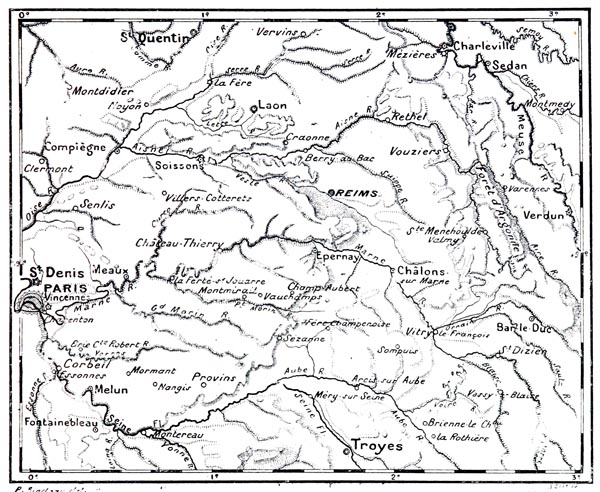

‘Carte de la Campagne de France.’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p881, 1888)

The British Library

BkXXII:Chap9:Sec1

In the second book of these Memoirs, it states (I was then returning from my first exile in Dieppe): ‘I was allowed to return to my Vallée. The earth trembles under the feet of foreign soldiers. I write like one of the last Romans, amidst the sounds of the Barbarian invasion. By day I trace pages as troubled as the events of the day..at night, while the rumble of distant cannon dies away among my woods, I return to the silence of years that sleep in the tomb, to the tranquillity of my earliest memories.’

These restless pages that I trace today were notes respecting the events of the time, which, collected, became my pamphlet: De Bonaparte et des Bourbons. I had such an elevated idea of Napoleon’s genius and the bravery of our soldiers, that foreign invasion, happy as it might be in its final outcome, would never have entered my head: but I thought that invasion, in making France realise the danger into which Napoleon’s ambition had led her, would lead to an internal reaction, and that the freedom of the French would be achieved by their own efforts. It was with this idea in mind that I wrote my notes, in order that if our political assemblies halted the march of the Allies, and resolved to divorce themselves from the great man, who had become a scourge, they would know whom to resort to; it seemed to me that recourse was to be found in that authority, modified to suit the times, under which our ancestors had lived for eight centuries: when in a storm one finds only an old building within reach, ruined as it is, one shelters there.

In the winter of 1813-1814, I took an apartment on the Rue de Rivoli, facing the front railings of the Tuileries Garden, before which I had heard the death of the Duc d’Enghien being cried aloud. As yet in that street one could only see the arcades built by the Government and a few isolated houses, rising up here and there, their jagged sides outlines of waiting stone.

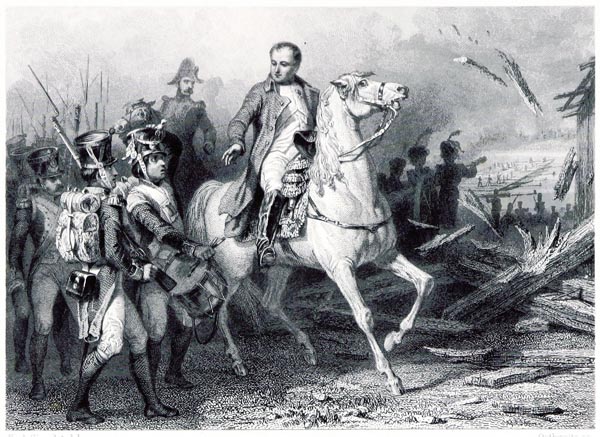

It required nothing less than the ills that weighed on France, to maintain the aversion that Napoleon inspired and at the same time resist the admiration that he could arouse as soon as he stirred: he was the most incredible genius in action who ever existed; his first Campaign in Italy and his last Campaign in France (I do not speak of Waterloo) were his two finest campaigns; Condé in the first, Turenne in the second, a great warrior in the former, a great man in the latter; though they differed in their outcomes: since with the one he gained an Empire, with the other he lost it. His last moments of power, naked and rootless as they were, could not have been extracted from him, like the teeth of a lion, except by the exertion of all Europe. Napoleon’s name was still so formidable that the enemy armies only crossed the Rhine with apprehension; they looked behind them constantly to make sure that retreat was still possible; masters of Paris they still trembled. Alexander glancing back at Russia, on entering France, congratulated those who could return there, and wrote to his mother to express his anxiety and regret.

Napoleon beat the Russians at Saint-Dizier, the Prussians and the Russians at Brienne, as if to honour the fields in which he had been nurtured. He overthrew the Silesian army at Montmirail, at Champaubert and a section of the Grand Army at Montereau. He resisted everywhere; passing and re-passing in his own steps; pushing back the columns that surrounded him. The Allies proposed an armistice; Bonaparte tore up the peace preliminaries offered and shouted: ‘I am nearer to Vienna than the Austrian Emperor is to Paris!’

‘Bataille de Montereau, 18 février 1814. Peint par Ch. Langlois’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p895, 1888)

The British Library

Russia, Austria, Prussia and England, for mutual support, concluded a fresh treaty of alliance at Chaumont; but at heart, alarmed by Bonaparte’s resistance, they thought of retreat. At Lyons, an army presented itself on the Austrian flank; in the south, Marshal Soult halted the English; the Congress of Châtillon, which was not dissolved till the 15th of March, was still in negotiations. Bonaparte drove Blücher from the heights of Craonne. The Allied Grand Army only triumphed at Bar-sur-Aube, on the 27th of February, by weight of numbers. Bonaparte, increasing his forces, had recovered Troyes which had been reoccupied by the Allies. From Craonne he took himself to Rheims. ‘Tonight,’ he said, ‘I am off to catch my father-in-law at Troyes.’

On the 20th of March, an engagement took place near Arcis-sur-Aube. During an artillery barrage, on a shell falling in front of a Guards’ square the square appeared to make a slight movement. Bonaparte dashed up to the projectile whose fuse was smoking and made his horse sniff at it; the shell exploded, while the Emperor emerged safe and sound from the midst of the shattered lightning-bolt.

The battle was due to recommence the following day; but Bonaparte, yielding to the inspiration of genius, an inspiration nonetheless fatal to him, withdrew in order to bear down on the rear of the allied troops, separate them from their supplies, and swell his army with the garrisons from the frontier forts. The invaders were preparing to fall back towards the Rhine, when Alexander, by one of those heaven-sent impulses which change the world, decided to march on Paris, to which the road was now open (I have heard General Pozzo recount that it was he who persuaded the Emperor to advance). Napoleon thought he was drawing the bulk of the enemy after him, but he was only followed by ten thousand cavalry, whom he took to be the vanguard of the main body, and who were masking the true movement of the Prussians and Muscovites. He scattered those ten thousand horsemen at Saint-Dizier and Vitry, and then realised that the Allied Grand Army was not behind them; that army, hastening towards the capital, had only Marshals Marmont and Mortier facing it, with about twelve thousand conscripts.

Napoleon headed in haste for Fontainebleau: where the sacred prisoner, in departing, had left it to those who would repay and avenge. Two things are always linked together throughout history: when a man opens the way to injustice, at that same moment he opens a way to perdition, into which, after a certain distance, the former path will collapse.

Book XXII: Chapter 10: I begin printing my pamphlet – A note from Madame de Chateaubriand

BkXXII:Chap10:Sec1

Minds were greatly agitated: the hope of seeing the end, cost what it might, of the cruel war which had weighed on a France sated for twenty years with glory and misfortune overcame national pride among the masses. All were concerned with the part they would have to play in the imminent catastrophe. Every evening my friends came to Madame de Chateaubriand’s to talk, to recount and comment on the day’s events. Messieurs de Fontanes, de Clausel, and Joubert, came with a crowd of those transient friends whom events bring and events take away. Madame la Duchesse de Lévis, beautiful, tranquil and devoted, whom we will meet again in Ghent, kept Madame de Chateaubriand faithful company. Madame la Duchesse de Duras was also in Paris, and I often went to see Madame la Marquise de Montcalm, the Duc de Richelieu’s sister.

I continued to be persuaded, despite the approach of fighting, that the Allies would not enter Paris, and that a national uprising would put an end to our fears. My obsession with that idea prevented me reacting to the presence of the foreign armies as keenly as I might have done: but I could not help reflecting on the calamities which we had inflicted on Europe, seeing Europe bringing them upon us in turn.

I did not stop working at my pamphlet; I was preparing it like a remedy for the time when anarchy would burst upon us. We no longer write like that today, at our ease, and with nothing to fear but newspaper skirmishes: at night I locked myself in; I put my papers under my pillow, a pair of loaded pistols on my table: I slept between those two Muses. My text was a double one; I had composed it in the form, which it retained, of a pamphlet, and also as a speech, differing in some respects from the pamphlet; I assumed that when France met, it would gather at the Hôtel de Ville, and I was doubly prepared.

Madame de Chateaubriand took notes at various times in our life together; among these notes, I find the following paragraph:

‘Monsieur de Chateaubriand wrote his pamphlet De Bonaparte et des Bourbons. If this pamphlet had been seized, punishment was not in doubt: the sentence would have been the scaffold. Yet the author betrayed unbelievable negligence in hiding it. Often, when he went out, he left it forgotten on the table; his prudence never went beyond placing it under his pillow, which he did in front of his manservant, a very honest lad, but one who might have succumbed to temptation. As for me, I was in mortal fear: as soon as Monsieur de Chateaubriand went out, I went to get the manuscript and hid it about me. One day, crossing the Tuileries, I realised I no longer had it, and, sure it was there when I went out, I was certain I had lost it en route. I saw the fatal writing already in the hands of the police, and Monsieur de Chateabriand arrested: I fell down, unconscious, in the middle of the gardens; some kind gentlemen came to my assistance, and took me back to the house which was not far away. What torment as I climbed the stairs, torn between fear, which was almost certainty, and a faint hope of having forgotten to pick up the pamphlet! Nearing my husband’s room, I felt a new faintness: I entered finally, nothing on the table: I went towards the bed; I first felt the pillow: I could feel nothing; I lifted it: I saw the scroll of paper! My heart quivers every time I think of it. I have never in my life experienced such a joyous moment. Certainly, I can truthfully say, it could have been no greater if I had found myself saved at the foot of the scaffold: since it was in fact someone dearer to me than my self who had been saved.’

How unhappy I would have been if I had realised I was capable of causing Madame de Chateaubriand a moment of pain!

However I had been obliged to entrust a printer with my secret; he had agreed to take the risk; according to the news of the hour, he returned or came to collect the half-composed proofs, as the sound of cannon fire approached or receded from Paris: for almost a fortnight I played heads or tails like this with my life.

Book XXII: Chapter 11: War at the gates of Paris – The appearance of Paris – Battle at Belleville – The Flight of Marie-Louise and the Regency – Monsieur de Talleyrand remains in Paris

BkXXII:Chap11:Sec1

The circle was tightening round the capital: every instant we learnt of the enemy’s progress. Russian prisoners and wounded Frenchmen were carried pell-mell through the gates in carts; some, half-dead, fell beneath the wheels which they stained with blood. Conscripts, called-up from the interior, crossed the capital in long files, to join the army. At night, you could hear artillery trains passing along the outer boulevards, and no one knew if the distant explosions proclaimed decisive victory or final defeat.

The war finally reached the gates of Paris. From the towers of Notre-Dame you could see the heads of the Russian columns appearing, like the first undulations of a tidal-wave on the beach. I felt as a Roman must have felt, on the summit of the Capitol, with Alaric’s soldiers and the ancient city of the Latins at his feet, just as I had Russian soldiers at my feet and the ancient city of the Gauls. Farewell then, paternal Lares, hearths which preserved national traditions, roofs beneath which breathed both Virginia sacrificed by her father to modesty and freedom, and that Héloïse consecrated by love to letters and religion.

For centuries Paris had not seen the smoke of enemy camp-fires, and it was Bonaparte, passing from triumph to triumph, who had given the Thebans sight of the women of Sparta. Paris was the marker from which he left to roam the earth: he returned leaving behind him the vast conflagration of his vain conquests.

People rushed to the Jardin des Plantes which the fortified abbey of Saint-Victor might once have been able to protect: the little world of swans and plantain-trees, to which our power had promised eternal peace, was troubled. From the summit of the maze, above the great cedar, over the granaries which Bonaparte had not had time to complete, beyond the site of the Bastille and the keep of Vincennes (places which tell of our historical development), the crowd could see the infantry-fire of the fight at Belleville. Montmartre was taken; cannonballs fell as far as the Boulevard du Temple. A few companies of the National Guard made a sortie and lost three hundred men in the fields around the ‘tomb of the martyrs’. Never did military France shine more brightly in the midst of her reverses: the ultimate heroes were the hundred and fifty young men of the École Polytechnique, transformed into artillery-men in the redoubts of the Chemin de Vincennes. Surrounded by the enemy, they refused to surrender; they had to be dragged from their guns: the Russian Grenadier seized them blackened with powder and covered with wounds; while they struggled in his arms, he lifted those young French palm branches in the air with cries of triumph and admiration, and restored them blood-stained to their mothers.

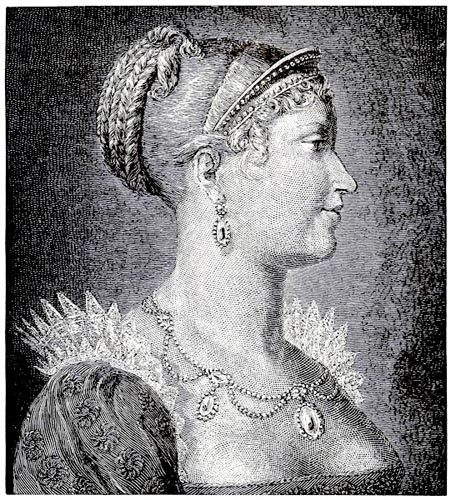

‘Marie-Louise of Austria, Second Wife of Napoleon I’

The Story History of France From the Reign of Clovis, 481 A.D., to the Signing of the Armistice, November, 1918 - John Bonner (p368, 1919)

Internet Archive Book Images

At that time Cambacérès had fled with Marie-Louise, the King of Rome and the Regency. On the walls you could read the following proclamation:

‘King Joseph, Lieutenant-General of the Emperor

Commander-in-Chief of the National Guard.

Citizens of Paris,

The Regency Council has provided for the safety of the Empress and the King of Rome: I remain here with you. Let us arm ourselves to defend our city, its monuments, its riches, our women, our children, and all that is dear to us. Let this vast city become a fortified camp for a while, and let the enemy find shame beneath her walls which he hopes to enter in triumph.’

‘Joseph Bonaparte’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p223, 1845)

The British Library

Rostopchin had not tried to defend Moscow; he set fire to it. Joseph announced that he would never abandon the Parisians, and decamped quietly, leaving us his brave words posted on the street corners.

Monsieur de Talleyrand was nominated as a member of the Regency by Napoleon. From the moment that the Bishop of Autun ceased to be Minister for Foreign Affairs, under the Empire, he only dreamt of one thing, Bonaparte’s disappearance, followed by the Regency of Marie-Louise; a Regency of which he, the Prince of Benevento, would be the head. Bonaparte, in naming him a member of the provisional Regency in 1814, seemed to have favoured his secret wishes. Napoleon’s death had not yet happened; it remained only for Monsieur de Talleyrand to hobble at the feet of the colossus he could not overthrow, and take advantage of the moment in his own interests: his savoir-faire was the genius of that man of bargains and compromise. The situation was difficult: to remain in the capital was what was indicated; but if Bonaparte returned, the Prince separated from the fugitive Regency, the tardy Prince, ran the risk of being shot; on the other hand, how could he abandon Paris at the moment when the Allies might enter? Would that not be to renounce the benefits of success, betray that dawn of events, for which Monsieur de Talleyrand had been created? Far from siding with the Bourbons, he feared them because of their sundry apostasies. However, since they stood a chance of power, Monsieur de Vitrolles, with the consent of the married priest, went furtively to the Congress of Châtillon, as the unacknowledged go-between with the Legitimacy. That precaution taken, the Prince, in order to extract himself from his Paris difficulty, had recourse to one of those tricks of which he was past master.

Monsieur Laborie, who a little later became, under Monsieur Dupont de Nemours, Private Secretary to the Provisional Government, went to find Monsieur de Laborde, attaché to the National Guard; he told him of Monsieur de Talleyrand’s departure: ‘He is disposed,’ he said, ‘to follow the Regency; it may appear necessary to you to prevent him, in order for him to be in a position to negotiate with the Allies, if needs be.’ The comedy was played to perfection. The Prince’s carriages were loaded up, with great commotion; he set out at high noon, on the 30th of March: arriving at the Barrière d’Enfer, he was inexorably returned to his residence, despite his protestations. In case of Napoleon’s miraculous return, the evidence was there, witnessing that the former Minister had wished to join Marie-Louise and that armed force had refused him passage.

Book XXII: Chapter 12: The proclamation of General the Prince Schwarzenberg – Alexander’s speech – The capitulation of Paris

BkXXII:Chap12:Sec1

Meanwhile, on the arrival of the Allies, Comte Alexander de Laborde and Monsieur Tourton, senior officers of the National Guard, had been sent to General the Prince Schwarzenberg, who had been one of Napoleon’s generals during the Russian Campaign. The General’s proclamation was issued in Paris on the evening of the 30th of March. It read: ‘For twenty years Europe has been drenched in blood and tears; attempts to put an end to these ills have proven vain, since there exists, in the very nature of the Government which oppresses you, an insurmountable obstacle to peace. Parisians, you know the state of your country: the preservation and tranquillity of your city will be subject to careful attention on the part of the Allies. It is with these sentiments that Europe, in arms beneath your walls, addresses you.’

What a magnificent acknowledgement of France’s greatness: Europe, in arms beneath your walls, addresses you!

We, who had respected nothing, were granted respect by those whose cities we had ravaged, and who, in turn, had become stronger. We seemed to them a sacred nation; our land appeared to them like the fields of Elis which, by decree of the gods, no army could tread. Nevertheless, if Paris had thought it necessary to resist, within twenty four hours the result might quite easily have been different; but no one, except soldiers intoxicated by war and honour, desired Bonaparte any longer, and, in fear of his remaining in power, they rushed to open the gates.

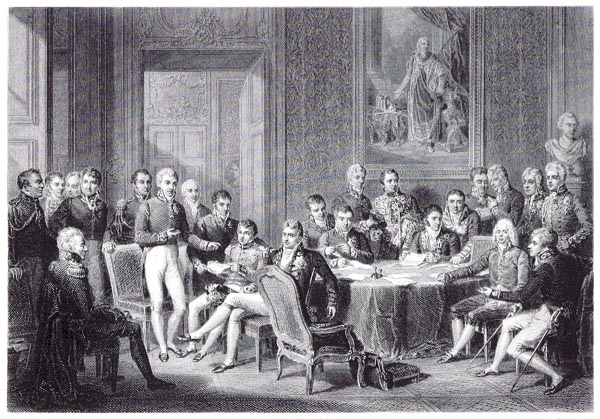

Paris capitulated on the 31st of March 1814: the military surrender was signed, in the names of Marshals Mortier and Marmont, by Colonels Denis and Fabvier; the civil surrender took place in the name of the mayors of Paris. The municipal and departmental council were deputed to visit the Russian headquarters in order to settle the various articles: my companion in exile, Christian de Lamoignon, was one of the representatives. Alexander told them:

‘Your Emperor, who was my ally, recently entered the heart of my State and brought to it evils whose traces will be long lasting; the rights of defence led me here. I am far from wishing to cause France the ills which I have experienced. I am just, and I know it is not the fault of the French. The French are my friends, and I will prove it to them by rendering good for evil. Napoleon alone is my enemy. I promise my personal protection to the city of Paris; I will protect your National Guard which is composed of the elite of your citizens. It is for you to assure your future happiness; you must adopt a Government which will bring you and Europe peace. It is for you to voice your wishes: you will find me ready always to support your efforts.’

Words which were swiftly realised: the joy of victory overrode every other interest, as far as the Allies were concerned. What must Alexander’s feelings have been, as he gazed at the domed buildings of that city which the stranger only ever enters in order to admire, to enjoy the wonders of civilisation and intellect; of that inviolable city, defended by its great men for twelve centuries; of that glorious capital which seemed protected now from Louis XIV’s shadow, and Bonaparte’s return!

Book XXII: Chapter 13: The Allies enter Paris.

BkXXII:Chap13:Sec1

God had uttered one of those words which at rare intervals shatter the silence of eternity. Now, for the present generation, the hammer that Paris had only heard sound once before, rose to strike the hour; on the 25th of December 496, Rheims proclaimed the baptism of Clovis, and the gates of Lutetia opened to the Franks; on the 30th of March 1814, after the blood-stained baptism of Louis XVI, the old hammer, motionless for so long, rose anew in the belfry of the ancient monarchy; a second stroke rang out, and the Tartars entered Paris. In the intervening one thousand three hundred and eighteen years, foreigners had damaged the walls of our Empire’s capital without ever finding the means to enter, save when they slipped in, summoned by our own divisions. The Normans besieged the city of the Parisii; the Parisii jeered at the sparrow-hawks they bore on their fists; Odo, child of Paris and future king, rex futurus, says Abbo, drove back the pirates from the North: the Parisiens let slip their eagles in 1814; the Allies entered the Louvre.

Bonaparte had waged war unjustly against Alexander, his admirer, who had begged for peace on his knees; Bonaparte had ordered the carnage at Borodino; he had forced the Russians to set fire to Moscow themselves; Bonaparte had plundered Berlin; humiliated its King, insulted its Queen: what reprisals were we then to expect? You shall see.

In the Floridas, I had wandered round nameless monuments, devastated long ago by conquerors of whom no trace remains, and had lived to see the Caucasian hordes encamped in the courtyard of the Louvre. In those events of history which, according to Montaigne: ‘are feeble testimony to our worth and capacity’, my tongue cleaves to my palate:

‘Adhaeret lingua mea faucibus meis’

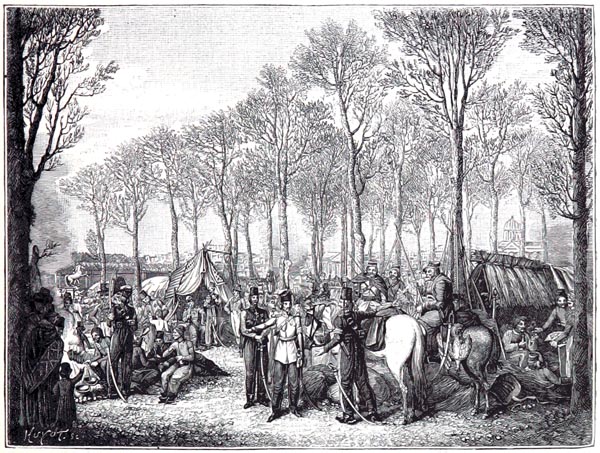

The Allied Army entered Paris at midday on the 31st of March 1814, only ten days after the anniversary of the death of the Duc d’Enghien, on the 21st of March 1804. Was it worth Bonaparte’s while to commit a deed so long remembered for the sake of so short a reign? The Emperor of Russia and the King of Prussia rode at the head of their troops. I watched them marching along the boulevards. Stupefied and inwardly amazed, as if someone had torn from me my French identity and substituted a number by which I would henceforth be known in the mines of Siberia, at the same time I felt my exasperation with that man, whose glory had reduced us to this shame, increase.

‘Bivouac des Cosaques, dans les Champs-Élysées, à Paris, d'Après une Aquarelle de G. Opiz (Collection Hennin)’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p907, 1888)

The British Library

However, this first invasion of the Allies remains unparalleled in the history of the world: peace, order, and moderation reigned everywhere; the shops re-opened; Russian guardsmen, six feet tall, were guided through the streets by little French urchins who laughed at them, as if they were wooden puppets or carnival mummers. The conquered might have been taken for conquerors; the latter, trembling at their success, had an apologetic air. The National Guard alone garrisoned the interior of Paris, with the exception of the houses in which foreign kings and princes lodged. On the 31st of March 1814, countless armies were occupying France; a few months later, all those troops re-crossed the frontier, without firing a shot, without shedding a drop of blood, after the return of the Bourbons. The former France found herself augmented on some of her frontiers; the ships and warehouses of Antwerp were shared with her; three hundred thousand prisoners scattered throughout the countries where victory or defeat had left them, were restored to her. After twenty years of fighting, the sound of weapons ceased from one end of Europe to the other; Alexander departed, leaving us the looted masterpieces and the freedom enshrined in the Charter, freedom which we owed as much to his enlightenment as his influence. The head of the two supreme authorities, autocrat by means of both the sword and religion, he alone of all the sovereigns of Europe had understood that at the stage of civilisation which France had attained, she could only be governed by virtue of a free constitution.

In our quite natural hostility towards foreigners, we have confused the invasions of 1814 and 1815, which were in no sense alike.

Alexander considered himself merely an instrument of Providence and took no credit himself. Madame de Staël complimenting him on the good fortune which his subjects, lacking a constitution, enjoyed in being governed by him, he made his well known reply: ‘I am merely a happy accident.’

A young man, in a Paris street, expressed to him his admiration at the affability with which he greeted the humblest citizens; he replied: ‘Are sovereigns not made for that?’ He had no wish to inhabit the Tuileries, remembering that Bonaparte had taken his pleasure in the palaces of Vienna, Berlin and Moscow.

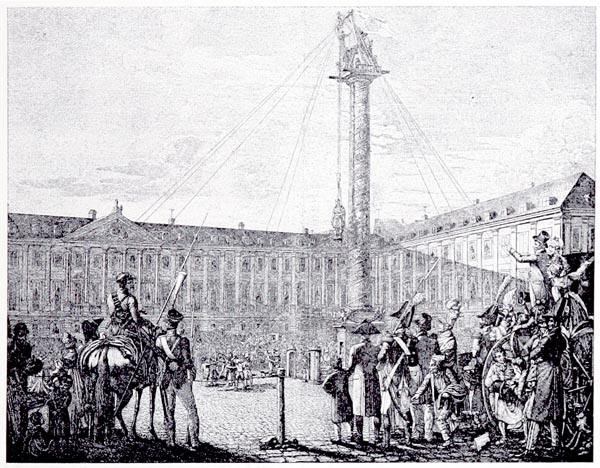

Gazing at the statue of Napoleon on the column in the Place Vendôme, he remarked: ‘If I were as high up as that, I would be afraid of vertigo.’

When he was touring the Tuileries Palace, he was shown the Salon de la Paix: ‘What use,’ he said laughing, ‘was this room to Bonaparte?’

On the day Louis XVIII entered Paris, Alexander hid behind a window, wearing no mark of distinction, to watch the procession pass.

He frequently displayed elegant and charming manners. Visiting a madhouse, he asked a woman if the number who had gone mad with love was considerable: ‘Not until now,’ she replied, ‘but it is to be feared it will increase from the time of Your Majesty’s entering Paris.’

One of Napoleon’s grand dignitaries said to the Tsar: ‘We have been waiting and hoping here for your arrival, for a long time, Sire.’ – ‘I would have come sooner,’ he replied, ‘blame French valour alone for my delay.’ it is known that when crossing the Rhine he had regretted not being able to return peacefully to his family.

At the Hôtel des Invalides, he found the maimed soldiers who had defeated him at Austerlitz: they were silent and sombre; only the sound of their wooden legs echoed in the empty courtyards and denuded church; Alexander was moved by this sound made by brave men: he ordered that twelve Russian cannon should be given to them.

A proposal to change the name of the Pont d’Austerlitz was made to him: ‘No,’ he said, ‘it is enough for me to have crossed that bridge with my army.’

Alexander had something calm and sorrowful about him: he went about Paris, on horseback or on foot, without his suite and without affectation. He seemed surprised at his triumph; his almost tender gaze wandered over a population whom he seemed to consider superior to himself: one would have said that he found himself a barbarian among us, as a Roman would have felt ashamed in Athens. Perhaps he also reflected that these same Frenchmen had appeared in his burnt-out capital; that his soldiers were in turn masters of Paris where he might have found some of the extinguished torches by which Moscow was freed and consumed. This sense of destiny, of changing fortunes, of the common suffering of nations and kings, must have struck a mind as religious as his profoundly.

Book XXII: Chapter 14: Bonaparte at Fontainebleau – The Regency at Blois

BkXXII:Chap14:Sec1

What was the victor of Borodino doing? As soon as he heard of Alexander’s decision, he sent orders to Major Maillard de Lescourt of the artillery to blow up the powder-magazine at Grenelle: Rostopchin had set fire to Moscow, but he had evacuated the inhabitants first. From Fontainebleau, to which he had returned, Napoleon advanced as far as Villejuif: there he looked down on Paris; foreign soldiers were guarding the city gates; the conqueror recalled the days when his grenadiers had kept watch on the ramparts of Berlin, Moscow, and Vienna.

Events erase other events: how insignificant today seems the grief of Henri IV learning at Villejuif of the death of Gabrielle, and returning thence to Fontainebleau! Bonaparte returned to that solitude also; nothing awaited him there but the memory of his august prisoner: the captive of peace had mot long since departed the palace in order to leave it free for the captive of war, ‘so swiftly does misfortune fill a place.’

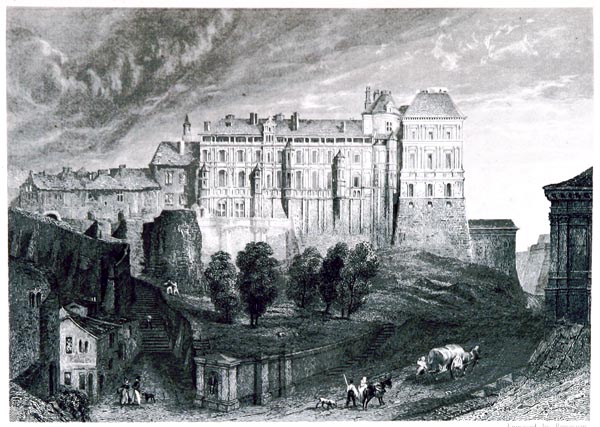

The Regency had retired to Blois. Bonaparte had given orders for the Empress and the King of Rome to leave Paris, saying he would prefer to see them at the bottom of the Seine than led to Vienna in triumph; but at the same time he urged Joseph to remain in the capital. His brother’s flight made him furious, and he accused the King of Spain of ruining everything. The Ministers, the members of the Regency, Napoleon’s brothers, his wife and son arrived at Blois in disorder, swept away by the debacle: wagons, baggage-vans, carriages, everything was there; even the royal coaches were there and were dragged through the mud of the Beauce to Chambord, the only morsel of France left to Louis XIV’s heirs. Some of the ministers crossed over, and went to hide in Brittany, while Cambacérès was carried in state in a sedan-chair through the steep streets of Blois. Various rumours were current; there was talk of two camps and a general requisition. For several days they knew nothing of what was happening in Paris; the uncertainty only ended with the arrival of a carter whose pass was signed Sacken. Soon the Russian General Shuvalov arrived at the Auberge de la Galère: he was promptly besieged by the grandees, desperate to obtain visas from him for their headlong flight. However, before leaving Blois, they all drew on Regency funds for their travelling expenses and arrears of salary: they grasped their passports in one hand and their money in the other, taking care at the same time to assure the Provisional Government of their support, not losing their heads. Madame Mère and her brother, Cardinal Fesch, left for Rome. Prince Esterhazy arrived on behalf of Francis II to fetch Marie-Louise and her son. Joseph and Jérôme headed for Switzerland, after trying to compel the Empress, in vain, to share their fate. Marie-Louise hastened to join her father: indifferently attached to Bonaparte, she found thereby the means to console herself, and rejoiced at being delivered from the double tyranny of a husband and master. When, the following year, Bonaparte brought this same confused flight on the Bourbons, the latter, barely free of their long tribulations, had not enjoyed fourteen years of unexampled prosperity in which to grow accustomed to the comfort of a throne.

‘Château de Blois’

L'Orléanais. Histoire des Ducs et du Duché d'Oriéans...Illustrée par MM. Baron, Louis Français - Henri-Charles-Antoine Baron (p507, 1845)

The British Library

Book XXII: Chapter 15: The publication of my pamphlet – De Bonaparte et Des Bourbons

BkXXII:Chap15:Sec1

However Napoleon was not yet dethroned; more than forty thousand of the best soldiers in the world accompanied him; he could withdraw beyond the Loire; the French armies which had arrived from Spain were making growling noises in the south; the seething military population might still discharge its lava; even among the foreign leaders, there was still talk of Napoleon or his son ruling France: for two days Alexander hesitated. Monsieur de Talleyrand was secretly inclined, as I have said, to the policy which favoured crowning the King of Rome, since he dreaded the Bourbons; if he did not enter unreservedly into the plan for the Regency of Marie-Louise, it was because, Napoleon still being alive, he, the Prince of Benevento, feared that he would be unable to retain control during a minority threatened by the existence of a restless, unpredictable and enterprising man still in the prime of life.

It was during these critical days that I launched my pamphlet De Bonaparte et des Bourbons in order to turn the scale: the effect is well known. I threw myself headlong into the fray to serve as a shield to renascent liberty against a tyranny which was still active and whose strength was increased threefold by despair. I spoke in the name of the Legitimacy, in order to lend my words the authority of pragmatic politics. I apprised France of what the old royal family represented; I told her how many members of that family were still alive, and their names and characters; it was as if I were listing the children of the Emperor of China, so thoroughly had the Republic and Empire invaded the present and relegated the Bourbons to the past. Louis XVIII declared, as I have mentioned several times elsewhere, that my pamphlet had been more use to him than an army of a hundred thousand men; he might have added that it acted as proof of his existence. I helped to crown him for a second time, by the favourable outcome of the Spanish War.

From the very beginning of my political career, I had made myself unpopular with the people, but from that moment on I also lost favour with the powerful. All those who had been slaves under Bonaparte detested me; on the other hand, I was suspect among all those who wished to return France to a state of vassalage. Of all the sovereigns, only Bonaparte himself was on my side at first. He perused my pamphlet at Fontainebleau: the Duke of Bassano had brought it to him; he discussed it impartially, saying: ‘This is right, this is not right. I have nothing to reproach Chateaubriand with; he opposed me when I was in power; but those swine, such and such!’ and he named them.

My admiration for Bonaparte has always been great and sincere, even when I attacked Napoleon most fiercely.

Posterity is not as just in its assessments as they say; there are passions, infatuations, errors of distance as there are passions and errors of proximity. When posterity admires someone unreservedly it is scandalised if the contemporaries of the man it admires had not the same opinion it holds itself. Yet, it is obvious: the things which offended in that person are done with; his infirmities died with him; of him, only the imperishable life remains; but the evil he caused is no less real; evil in itself and in essence, evil above all for those who endured it.

It is fashionable today to exaggerate Bonaparte’s victories: those who suffered have disappeared; we no longer hear the curses, the cries of pain, the distress of the victims; we no longer see France exhausted, with only women to till her soil; we no longer see parents arrested as hostages for their sons, or the inhabitants of a village sentenced one and all to punishments applicable to a deserter; we no longer see conscription notices posted on street corners, the passers-by crowding to see those vast death-warrants, searching, in consternation for the names of children, brothers, friends and neighbours. We forget that everyone mourned the victories; we forget that the slightest allusion antagonistic to Bonaparte, in the theatre, that escaped the censors, was seized on with joy; we forget that the people, the Court, the generals, the ministers, and Napoleon’s relatives were weary of his oppression and his conquests, weary of that game which was always won and always in play, of that existence which was brought into question each morning by the impossibility of peace.

The reality of our sufferings is revealed by the catastrophe itself: if France had been devoted to Bonaparte, would she have rejected him twice, abruptly and totally, without making a last effort to retain him? If France owed everything to Bonaparte, glory, liberty, order, prosperity, industry, commerce, manufacture, monuments, literature, and fine arts; if the nation had achieved nothing itself prior to his period of rule; if the Republic had neither defended nor enlarged its borders, devoid of genius and courage, then would not France have been truly ungrateful, truly cowardly, in allowing Napoleon to fall into the hands of his enemies, or at least in not protesting against the captivity of so great a benefactor?

This reproach, which might be justly levelled against us, is not however levelled against us, and why? Because it is evident that, at the moment of his fall, France did not wish to defend Napoleon; on the contrary, she deliberately abandoned him; in our bitter distaste, we no longer recognised anything in him but the author and despiser of our woes. The Allies did not conquer us: it was we ourselves, choosing between two scourges, who renounced the shedding of our blood, which had ceased to flow for freedom.

The Republic had been too cruel, it is true, but everyone had hoped it would end, that sooner or later we would recover our rights, while retaining the defensive conquests it had made in the Alps and on the Rhine. All the victories it had brought us were gained in our name; for the Republic it was a question of France solely; it was ever France that had triumphed, that had conquered; it was our soldiers who had achieved everything and for whom triumphs or funeral celebrations were established; the generals (and there were some very great ones) won an honourable but humble place in public memory: such were Marceau, Moreau, Hoche, Joubert; the two latter destined to hold command under Bonaparte, who, new to glory, quickly encountered General Hoche, and rendered illustrious by his jealousy that warrior and peacemaker, who died shortly after his triumphs at Altenkirchen, Neuwied and Kleinnister.

Under the Empire, we vanished; it was no longer a question of us, everything belonged to Bonaparte: I have ordered, I have conquered, I have spoken; my eagles, my crown, my blood, my family, my subjects.

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p922, 1888)

The British Library

Yet what happened in those two situations at once similar and contrasting? We did not abandon the Republic in its reverses; it killed us, but it honoured us; we avoided the shame of being someone else’s property; thanks to our efforts, it was not invaded; the Russians, defeated beyond the mountains, had just shot their bolt at Zürich.

As for Bonaparte, he, despite his vast acquisitions, succumbed, not because he was defeated, but because France no longer wanted him. A mighty lesson! One that we ought always to remember, that there is a germ of death in everything that wounds human dignity.

BkXXII:Chap15:Sec2

Free spirits of every shade of opinion employed a common language at the time when my pamphlet was published. Lafayette, Camille Jordan, Ducis, Lemercier, Lanjuinais, Madame de Staël, Chénier, Benjamin Constant, Lebrun, thought and wrote as I did. Lanjuinais said: ‘We have been seeking a master among men whom the Romans did not desire as slaves.’

Chénier treated Bonaparte no more favourably:

‘A Corsican devoured the French inheritance.

You the elite, you heroes reaped in battle,

You martyrs, dragged with glory to the scaffold,

You died content with other hopes perchance.

Waves of blood, of tears have drenched France,

Those tears; that blood, one man inherited.

.....................

Believer, for a while, I praised his victories,

In forum, senate, pleasures, and festivities.

.....................

But, when he hurried home again, in flight,

Forsaking laurels for an Empire, overnight,

I did not bow before his glittering infamy;

My voice has ever been oppression’s enemy;

Watching while waves of flatterers, or worse,

Sold him, the State, their adulatory verse,

The court, the tyrant, caught no sight of me;

For I sang not of power, I sang of glory.’

(Promenade, 1805)

Madame de Staël passed no less severe a judgement on Napoleon:

‘Would it not provide a fine example to the human species, if the Directors (the five members of the Directory), very unwarlike men, could rise again from their ashes and call Napoleon to account for the lost frontiers of the Rhine and the Alps, conquered by the Republic, for the two-fold entry of foreign armies into Paris; for the three million French who perished from Cadiz to Moscow; above all for that sympathy the nations felt for the cause of French freedom, which is now transformed into an inveterate aversion?’

(Considérations sur la Révolution Française)

Let us listen to Benjamin Constant:

‘He who, for twelve years, proclaimed he was destined to conquer the world, has made honourable amends for his pretensions..........

Even before his territory was invaded, he was the victim of problems he could not conceal. His frontiers were scarcely breached, when he divested himself of all his conquests. He required the abdication of one of his brothers; he agreed the expulsion of another; without being asked he announced his renunciation of it all.