François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXI: Napoleon: Russia - Invasion and Retreat: to 1813

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXI: Chapter 1: The Invasion of Russia – Vilna – Wibicki, the Polish Senator – The Russian Parlimentarian Balashov – Smolensk – Murat – Platov’s son

- Book XXI: Chapter 2: The Russian retreat – The Borysthenes – Bonaparte’s obsession – Kutuzov succeeds Barclay in command of the Russian Army – The Battle of Moscow or Borodino – Bulletin – The appearance of the battlefield

- Book XXI: Chapter 3: Extract from the eighteenth bulletin of the Grand Army

- Book XXI: Chapter 4: The French advance – Rostopchin – Bonaparte on Salutation Hill – The View of Moscow – Napoleon enters the Kremlin – The Burning of Moscow – Bonaparte reaches the Petrovsky Palace with difficulty – Rostopchin’s proclamation – A halt among the ruins of Moscow – Bonaparte’s pastimes

- Book XXI: Chapter 5: Retreat

- Book XXI: Chapter 6: Smolensk – The Retreat continued

- Book XXI: Chapter 7: Smolensk – The Crossing of the Berezina

- Book XXI: Chapter 8: A verdict on the Russian Campaign – The last bulletin of the Grand Army – Bonaparte’s return to Paris – The Senate Address

Book XXI: Chapter 1: The Invasion of Russia – Vilna – Wibicki, the Polish Senator – The Russian Parlimentarian Balashov – Smolensk – Murat – Platov’s son

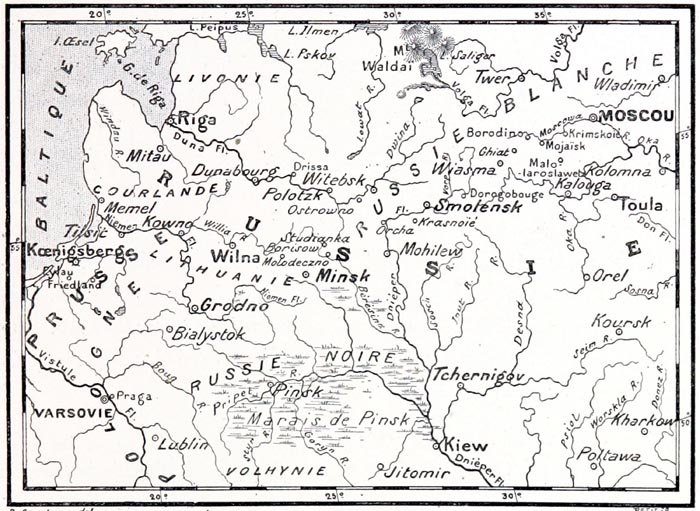

‘Carte de la Campagne de Russie’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p797, 1888)

The British Library

BkXXI:Chap1:Sec1

When Bonaparte crossed the Niemen, eighty-five million five hundred thousand souls recognised his rule or that of his family; half the population of Christendom obeyed him; his orders were executed over the space of nineteen degrees latitude and thirty degrees longitude. Never has so gigantic an expedition been seen before, nor will be seen again.

On the 22nd of June, at his headquarters at Wilkowiski, Napoleon declares war: ‘Soldiers, the second Polish War has commenced; the first ended at Tilsit; Russia is driven on by fate: her destiny must be accomplished.’

Moscow replies to this still youthful voice through the mouth of its Metropolitan, a hundred and ten years old: ‘The city of Moscow welcomes Alexander its Saviour as a mother in the arms of her eager sons, and sings Hosanna! Blessed be he who comes!’ Bonaparte addressed himself to Destiny, Alexander to Providence.

On the 23rd of June 1812, Bonaparte reconnoitred the Niemen at night; he ordered three bridges thrown across it. At nightfall of the following day, a handful of sappers crossed the river by boat; they found no one on the other side. A Cossack officer, commanding a patrol, came up to them and asked who they were. ‘Frenchmen.’ – ‘Why have you come to Russia?’ – ‘To make war on you.’ The Cossack vanished into the trees; three sappers fired towards the forest; there was no response: just universal silence.

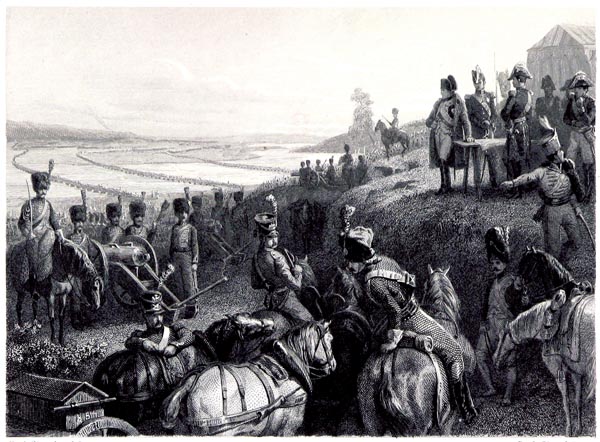

‘Passage du Niemen’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p205, 1845)

The British Library

Bonaparte spent a whole day lying down, without strength but without recuperation either: he could feel something retreating from him. His military columns advanced through the forest of Pilwisky, under cover of darkness, like the Huns who were led by a doe across the Sea of Azov. The Niemen could not be seen; to recognise it one had to be on its banks.

At daybreak, instead of Muscovite battalions, or Lithuanians, advancing to meet their liberators, there was only bare sand and empty forest to be seen: ‘Three hundred paces from the river on the highest point the Emperor’s tent was visible. Around it all the hills, slopes and valleys were covered with men and horses.’ (Ségur.)

The whole force under Napoleon’s orders amounted to six hundred and eighty thousand three hundred infantry, and seventy-six thousand eight hundred and fifty cavalry. In the War of the Succession, Louis XIV had six hundred thousand men under arms, all French. The regular infantry, under Bonaparte’s immediate command, was divided into ten corps. These corps were made up of twenty thousand Italians; eighty thousand men from the Confederation of the Rhine; thirty thousand Poles; thirty thousand Austrians, twenty thousand Prussians; and two hundred and seventy thousand Frenchmen.

The army crosses the Niemen; Bonaparte passes over the fateful bridge himself and sets foot on Russian soil. He halts to watch his soldiers file past then vanishes from sight, to gallop at random through the forest, as if he has been summoned to a council of spirits on the heath. He returns; he listens; the army listens. They imagined they could hear cannon fire rumbling in the distance; they were filled with joy: it was merely a storm; battle was postponed. Bonaparte took shelter in a deserted monastery: a doubly peaceful sanctuary.

There is a story that Napoleon’s horse stumbled and someone was heard to murmur: ‘It’s a bad omen; a Roman would turn back.’ This is the old tale told of Scipio, William the Conqueror, Edward III, and Malesherbes setting out for the Revolutionary Tribunal.

Three days were needed for the troops to cross; then they fell into line and advanced. Napoleon pressed on; time cried out to him: ‘March! March!’ as Bossuet once proclaimed.

At Vilna, Bonaparte received Senator Wibicki, of the Diet of Warsaw: a Russian parliamentarian, Balashov, presented himself in turn; he declared that a treaty was still possible, that Alexander was not the aggressor, and that the French had appeared in Russia without declaring war. Napoleon replied that Alexander was merely a parade-ground general; and that Alexander only had three real generals: Kutuzov, about whom he, Bonaparte, was not concerned since he was Russian; Bennigsen, who had been too old six years earlier and was now in his second childhood; and Barclay, who was retired. The Duke of Vicenza, believing himself to have been insulted by Bonaparte during the conversation, interrupted him angrily: ‘I am a good Frenchman; I have proved so; I will prove it again by repeating that this war is ill-advised, dangerous, and will ruin the army, France and the Emperor.’

Bonaparte had said to the Russian envoy: ‘Do you think I care about your Polish Jacobins?’ Madame de Staël records this last comment, her exalted contacts kept her well-informed: she affirms that a letter exists written to Monsieur de Romanzov by one of Bonaparte’s Ministers, which proposed the erasure of the words Poland and Polish from European treaties: overwhelming proof of Napoleon’s contempt for his brave petitioners.

Bonaparte asked Balashov how many churches there were in Moscow; on his replying, he exclaimed: ‘What, so many churches in an age which is no longer Christian?’ – ‘Pardon, Sire,’ replied the Muscovite, ‘the Russians and the Spaniards still are.’

Balashov having been despatched with several unacceptable proposals, the last glimmer of peace vanished. The bulletins proclaimed: ‘Here then is the Russian Empire, so formidable from afar! It is a wasteland. It will take Alexander longer to collect his troops than Napoleon to reach Moscow.’

Bonaparte, arriving in Vitebsk, thought for a moment of calling a halt there. Returning to his headquarters, after seeing Barclay retreat once more, he flung his sword onto some maps and exclaimed: ‘I am stopping here! My 1812 campaign is over: that of 1813 will do the rest.’ He would have been happier if he had kept to this resolution which all his generals advised. He had invested some pride in receiving fresh peace proposals: seeing none appear, he grew bored; he was only twenty days from Moscow. ‘Moscow, the holy city!’ he kept saying. His eyes flashed, his brow darkened: the order to advance was given. Representations were made to him; he disdained them; Daru, when questioned, replied that: ‘he could conceive neither the purpose nor the necessity for such a war.’ The Emperor replied: ‘Do they take me for a madman? Do they think I make war on whim?’ Had they not heard him, the Emperor, say that ‘the Spanish War and the Russian were two cancers gnawing at France’? But to make peace, that needed two, and not a single letter from Alexander had been received.

And those cancers, where did they come from? These inconsequential statements go unnoticed, and are transformed if needs be into proofs of Napoleon’s guileless sincerity.

Bonaparte would have thought it degrading to be caught acknowledging an error. His soldiers complain that they no longer see him except in moments of battle, forever sending them to their deaths, never trying to keep them alive: he is deaf to their complaints. The news of peace between the Russians and Turks surprises him but does not hold him back: he launches himself on Smolensk. The Russian proclamations declared: ‘He (Napoleon) is coming, treachery in his heart but loyalty on his lips; he is coming to chain us to his legions of slaves. Let us carry the cross in our hearts and steel in our hands; let us draw the teeth of this lion; let us overthrow the tyrant who overthrows the world.’

On the heights of Smolensk Napoleon met up with the Russian Army, composed of a hundred and twenty thousand men: ‘I have them!’ he exclaimed. On the 17th of August, at daybreak, Belliard hurled a band of Cossacks into the Dnieper; the curtain of troops having fallen back, the Russian army could be seen on the road to Moscow; it was retiring. Bonaparte’s dream had eluded him once more. Murat, who had played a major part in the vain pursuit, felt such despair he wanted to die.

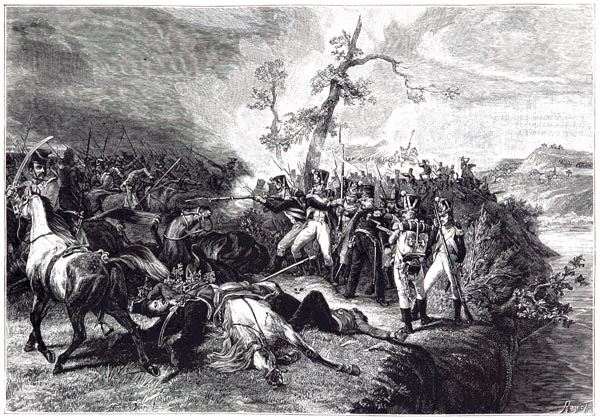

‘Enfants de Paris Devant Witepsk. 200 Voltigeurs du 9e Régiment Repousantles Charges des Cosaques de la Garde à la Traversée de la Dwina (27 juillet 1812). Tableau d'Horace Vernet, d'Après la Gravure de Jazet’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p807, 1888)

The British Library

He refused to quit one of our batteries shattered by the fire from the citadel of Smolensk, which had not yet been evacuated: ‘Get back, all of you; leave me alone here!’ he shouted. A fierce attack on that citadel took place: lined up on the heights above, which formed an amphitheatre, our army contemplated the battle below: when they saw the attackers plunging forward through fire and grapeshot, they clapped their hands as they had done on seeing the ruins of Thebes.

During the night, a fire attracted attention. One of Davout’s non-commissioned officers scaled the wall, and entered the citadel through the smoke; the sound of distant voices reached his ear: pistol in hand he advanced in that direction, and to his great astonishment, ran into a friendly patrol. The Russians had abandoned the town, and Poniatowski’s Poles had occupied it.

When we saw the Hetman Platov in Paris, we did not know of his paternal affliction: in 1812 he had a son, handsome as the Orient; this son rode a superb white horse from the Ukraine; the seventeen year old warrior fought with the daring of youth which flowers and hopes: a Polish uhlan (lancer) killed him. The Cossacks came respectfully to kiss the hand of the corpse which was laid out on a bearskin. They chanted the funeral prayers, and interred him on a pine-covered hillock; then, holding their horses’ bridles, they filed round the grave, with the points of their lances reversed: one might have thought one was watching an example of those funerals described by the historian of the Goths, or the Praetorian Guard reversing their fasces before the ashes of Germanicus, versi fasces. ‘The wind blew flakes of snow along, carried by the northern spring in its hair.’ (Saemund’s Edda)

Book XXI: Chapter 2: The Russian retreat – The Borysthenes – Bonaparte’s obsession – Kutuzov succeeds Barclay in command of the Russian Army – The Battle of Moscow or Borodino – Bulletin – The appearance of the battlefield

BkXXI:Chap2:Sec1

Bonaparte wrote to France from Smolensk saying that he was owner of the Russian salt-works, and that his Minister of Finance could count on eighty millions more.

Russia fled towards the pole: the nobility, leaving their wooden châteaux, left with their families, their serfs and their herds. The Dnieper, the ancient Borysthenes, whose waters were once proclaimed as holy by Vladimir, was crossed: that river had brought the Barbarian invasions to the civilised nations; now it carried an invasion by the civilised nations. A savage disguised under a Greek name, it no longer brought to mind the first Slavic migrations; it continued to flow unnoticed, carrying among forests, in its small boats, instead of Odin’s children, perfumes and shawls for the ladies of St Petersburg and Warsaw. Its story for the world only commences at those eastern mountains where Alexander’s altars were raised.

From Smolensk an army could be led either towards St Petersburg or Moscow. Smolensk should have been a warning to the conqueror to halt; for a moment he felt urged to do so: ‘The Emperor,’ says Monsieur Fain, ‘greatly discouraged, spoke of the idea of stopping at Smolensk.’ Medical supplies were already beginning to run out. General Gourgaud records that General Lariboisière was obliged to hand over the wadding from his guns: in order to provide dressings for the wounded. But Bonaparte was driven on; he delighted in contemplating the twin dawns at the ends of Europe which lit his armies, one above scorching plains the other over frozen steppes.

Orlando, in his narrow circuit of chivalry, chased after Angelica; conquerors of the first rank pursue a nobler sovereign: no rest for them until they clasp in their arms that divinity crowned with towers, the bride of Time, daughter of Heaven and mother of the gods. Obsessed by his own being, Bonaparte reduced everything to the personal; Napoleon had taken possession of Napoleon; there was no longer anything in him but self. So far he had only explored famous regions; now he was travelling a nameless road along which Peter the Great had scarcely sketched out the future cities of an empire not yet a hundred years old. If precedents were instructive, Bonaparte might have been concerned by the memory of Charles XII who passed through Smolensk on his way to Moscow. At Kolodrina there was a murderous engagement: the French corpses were buried in haste, so that Napoleon could not judge the extent of his losses. At Dorogobouj, he encountered a Russian with a beard of dazzling whiteness covering his chest: too old to follow his family and left alone in his house, he had seen the marvels of the end of Peter the Great’s reign and now, filled with silent indignation, was present to witness the devastation of his country.

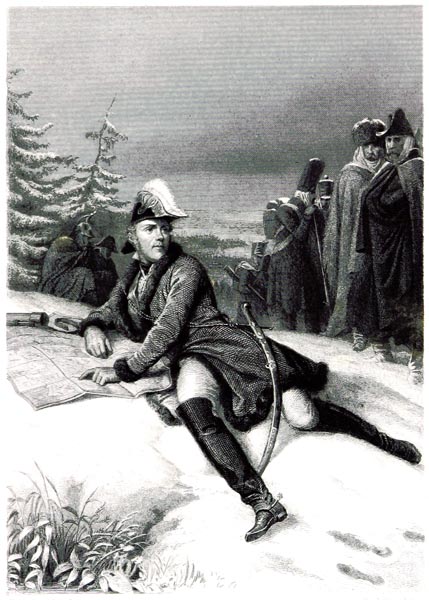

A succession of battles, offered and refused, brought the French to the field of Borodino. At every bivouac the Emperor discussed the situation with his generals, listening to their arguments while seated on a pine branch or toying with a Russian cannon ball which he rolled about with his foot.

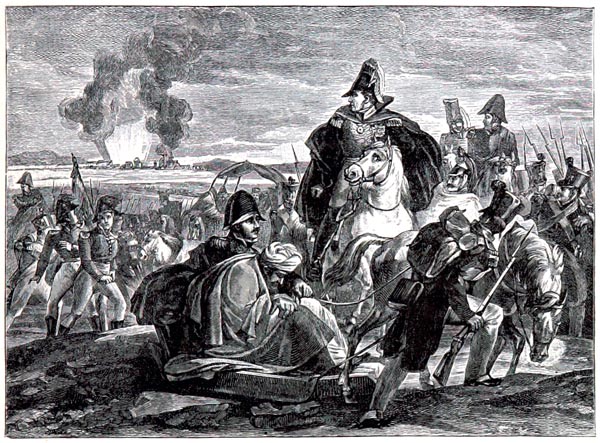

Barclay, the Livonian pastor, become a general, was the originator of this series of retreats which gave autumn time to overtake him: an intrigue at Court toppled him. The ageing Kutuzov replaced Barclay, Kutuzov who was beaten at Austerlitz because his advice, to avoid battle until the arrival of Prince Charles, was ignored. The Russians saw Kutuzov as a general of their own, Suvorov’s pupil, conqueror of the Grand Vizier in 1811, and author of the peace treaty with the Porte, so necessary to Russia at that time. At this juncture, a Muscovite officer presented himself at Davout’s outpost; he had been charged with bringing vague proposals; his true mission seemed to be to inspect and examine: he was shown everything. The French with their carefree, fearless curiosity asked him what they would find between Vyazma and Moscow: ‘Pultava,’ he replied.

Reaching the heights of Borodino, Bonaparte saw the Russian Army at last, which had halted and was formidably entrenched. It consisted of a hundred and twenty thousand men and six hundred guns; the French had a similar force. After inspecting the Russian left, Marshal Davout advises Napoleon to turn the enemy flank. ‘That would lose me too much time’, the Emperor replies. Davout insists: he undertakes to complete his manoeuvre before six in the morning; Napoleon interrupts sharply: ‘Oh, you are always wanting to turn the enemy’s flank.’

A great stir could be seen in the Muscovite camp: the troops were under arms; Kutuzov, surrounded by priests and archimandrites and preceded by religious emblems and a holy icon rescued from the ruins of Smolensk was talking to his soldiers about Heaven and the motherland; he called Napoleon the universal despot.

In the midst of battle songs and triumphant choruses mingled with cries of grief, a Christian voice was heard from the French camp also; it could be distinguished from all the rest; it was the sacred hymn rising alone beneath the vaults of the church. The soldier, whose voice calm, yet full of emotion, lingered beyond the others, was the aide-de-camp of the Marshal in command of the Horse-Guards. This aide-de-camp had been involved in every battle of the Russian Campaign; he speaks of Napoleon, as one of his greatest admirers; but he recognised his weaknesses; he corrects false tales, and declares that the errors made were due to the leader’s pride and his officers’ neglect of God. ‘In the Russian camp,’ Lieutenant-Colonel Baudus says, ‘they sanctified that vigil on a day which would be the last for so many brave men............................

The spectacle offered to my eyes by the enemy’s piety, as well as the jests it suggested to too many of the officers in our ranks, reminded me that the greatest of our kings, Charlemagne, was also inclined to begin the most dangerous of his enterprises with religious ceremony.

Ah, doubtless, among those errant Christians, a large number were to be found whose sincere belief sanctified their prayers; for if the Russians were defeated at the Moskva, our complete annihilation, which can in no way be considered glorious, since it was the manifest work of Providence, would show several months later that their pleas had only been too favourably heard!’

But where was the Tsar? He happened to say modestly to the fugitive Madame de Staël that he regretted not being a great general. At that moment Monsieur de Bausset, an officer of the Palace, appeared in our bivouacs: come from the tranquil woods of Saint-Cloud, following the dreadful tracks of our army, he arrived on the eve of the funerals by the Moskva; he had been charged with a portrait of the King of Rome, which Marie-Louise had sent to the Emperor. Monsieur Fain and Monsieur de Ségur portray the feeling which seized Napoleon on seeing it; according to General Gourgaud, Bonaparte, having viewed the portrait, exclaimed: ‘Take it away; he is seeing the field of battle too soon.’

The day before the storm was extremely calm: ‘The kind of skill,’ says Monsieur Baudus, ‘which goes into preparing such cruel follies, is somewhat humiliating to human reason when one thinks about it cold-bloodedly at my age; since, in my youth, I found it quite fine.’

Towards evening on the 6th of September, Bonaparte dictated this proclamation; it was not known to most of his remaining troops until after the victory:

‘Soldiers, here is the battle you so longed for. Victory now depends on you; it is essential to us, it will bring us wealth and a quick return home. Conduct yourselves as you did at Austerlitz, Friedland, Vitebsk and Smolensk, and may the most remote posterity cite your conduct on this day; may they say of you: “He was at that great battle before the walls of Moscow.”’

Bonaparte spent an anxious night: at one moment believing the enemy was retreating, at another worrying about his soldiers’ destitute state, and his officers’ weariness. He knew what was being said all around him: ‘To what end have we been made to march two thousand miles only to find marsh-water, hunger, and a bivouac among smoking ruins? Every year the war is worse: fresh conquests force him to seek out fresh enemies. Soon Europe will no longer suffice; he must have Asia.’ Indeed Bonaparte had looked with no indifferent eye on the waters which flowed into the Volga; born for Babylon, he had already been tempted by a previous route. Halted at Jaffa, at the western gate of Asia, halted at Moscow, at the northern gateway to that very Asia, he departed to die among the waves at the edge of that region of the world where mankind and the sun were born.

In the middle of the night, Napoleon summoned one of his aides-de-camp; the latter found him with his head buried in his hands: ‘What is war?’ he asked; ‘a barbaric trade whose only art consists in being stronger at any given point.’ He complained of the inconstancy of fortune; he sent for reports on the enemy positions: he was told that the fires were burning as brightly and in the same numbers; he calmed down. At five in the morning, Ney sent a request for the order to attack; Bonaparte went outside and exclaimed: ‘Let us open the gates of Moscow.’ Day broke; Napoleon pointed to the eastern sky which was beginning to redden: ‘See, the sun of Austerlitz!’ he cried.

Book XXI: Chapter 3: Extract from the eighteenth bulletin of the Grand Army

BkXXI:Chap3:Sec1

‘Mojaisk, 12th September 1812.

On the 6th, at two in the morning, the Emperor rode up and down the enemy’s forward positions; the day was spent in mutual reconnoitring. The enemy held a very well-defended position.

The position appeared good and strong. It would have been easy to manoeuvre and force the enemy to leave; but that would have delayed the action.............................

On the 7th, at six in the morning, General Comte Sorbier, who had set up the battery on the right with artillery from the Guard’s Reserve, began to fire..............................

At half-past six, General Compans was wounded. At seven, the Prince d’Eckmühl’s horse was killed.....................

At seven, Marshal le Duc d’Elchingen started to move forward once more and, under the protection of sixty cannon that General Foucher had positioned opposite the enemy centre the previous evening, advanced towards the centre. A thousand guns vomited death on every side.

At eight, the enemy positions were won, their redoubts taken, and our artillery crowned the summits..................

The enemy redoubts on the right still held out; General le Comte Morand advanced and took them; but at nine in the morning, attacked on all sides, he could not maintain his position. The enemy, encouraged by this success, advanced their reserve and their remaining troops in order to try their luck. The Russian Imperial Guard was part of the manoeuvre. It attacked our centre on which our right had pivoted. For a moment it looked as though it might take the burning village; Friant’s division fell on it; eighty French cannon first halted and then began to destroy the enemy columns which held out for two solid hours under heavy bombardment, not daring to advance, not wishing to retreat, while renouncing all hope of victory. The King of Naples put an end to their indecision; he ordered the fourth cavalry corps to charge; it penetrated the gaps that our cannon bombardment had made in the serried mass of Russians and theirs squadrons of cuirassiers; they scattered in all directions.....................

At two in the afternoon, the enemy abandon hope: the battle is over, the gunfire still continues; they beat the drums for a retreat and salute, but not for victory.

Our total losses are estimated at ten thousand men; those of the enemy at forty or fifty thousand. A like battlefield has never been seen. Of every six corpses one was French and five Russians. Forty Russian generals were killed, wounded or taken: General Bagration was wounded.

We have lost Major-General le Comte Montbrun, killed by a cannonball; General le Comte Caulaincourt, who had been sent to replace him, was killed in a similar manner an hour later.

‘Prise de la Grande Redonte, à la Moskora. Mort du Général Jean-Gabriel, Comte de Caulaincourt, Frère Cadet de Duc de Vicence - d'Après un Dessin d'Albrecht Adam, peintre de S. A. I. le Prince Eugène’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p813, 1888)

The British Library

Brigadier-Generals Compère, Plauzonne, Marion, and Huard have been killed; seven or eight Generals have been wounded, most of them lightly. The Prince d’Eckmühl is unharmed. The French troops have covered themselves with glory and have shown their great superiority over the Russians.’

Such in a few words is a sketch of the Battle of the Moskva, waged thirty miles from Mojaisk and seventy-five miles from Moscow.

The Emperor was never in danger; the Guard, on foot or horseback, has not yielded or lost a single man. The victory was never in doubt. If the enemy, forced from their positions, had not decided to re-take them, our losses would have been greater than theirs; but they have destroyed their army in holding fast from eight till two under fire from our batteries and persisting in re-taking what they had surrendered. That is the reason for their immense losses.’

This calm and reticent bulletin gives little idea of the Battle of the Moskva, and particularly of the terrible massacre at the Grand Redoubt: eighty thousand men were rendered hors de combat; thirty thousand of them belonged to France. Auguste de La Rochejaquelein had his face slashed by a sabre blow and became a prisoner of the Muscovites: he remembered other battles and another flag. Bonaparte, reviewing the 61st Regiment which had been virtually annihilated, said to the colonel: ‘Colonel, what have you done with one of your battalions?’ – ‘Sire, it is in the Redoubt.’ The Russians have always maintained and still maintain that they won the battle: they decided to raise a triumphal funeral column on the heights of Borodino.

Monsieur de Ségur’s narrative supplies what is missing from Bonaparte’s bulletin: ‘The Emperor rode up and down the field of battle.’ he says. ‘There has never been one with so terrible an aspect. All things conspired: a cloudy sky, a chill rain, a violent wind, houses in ashes, a devastated plain covered with debris and ruins; on the horizon the sad and sombre verdure of the northern trees; soldiers everywhere, wandering among the corpses looking for supplies, even in their dead comrades’ knapsacks; terrible wounds, for the Russian cannonballs are larger than ours; silent bivouacs; no more songs, an end to stories: only a dismal taciturnity.

Around the eagles, the remaining officers and junior officers could be seen, and a few soldiers, scarcely enough to guard the flags. Their uniforms were torn from the fierce fighting, blackened with powder, stained with blood; and yet, in the midst of these scarecrows, this wretchedness, this disaster, they had a proud air, and even, on sight of the Emperor, gave a few victory cries, though sparse and frenzied: since, in that army capable, in those days of analysis, of enthusiasm, each man judged the position of them all.

The Emperor could only judge his victory by the dead. The ground within the redoubts was so strewn with recumbent Frenchmen that it appeared to belong to them more than to those who remained standing. There seemed to more dead conquerors than living ones there.

Amongst the mass of bodies, over which it was necessary to step in order to follow Napoleon, a horse’s hoof touched a wounded man and drew from him a last sign of life and pain. The Emperor, mute till then like his victory, oppressed by the sight of so many victims, cried out, and relieved his feelings in cries of indignation, and by a multitude of attentions which he insisted on this poor wretch being shown. Then he sent the officers following him away, to help those who could be heard crying out on all sides.

Above all they could be found in the deep ravines into which the majority of our casualties had been precipitated, and where several had been dragged to give them more shelter from the enemy and the storm. Some while groaning called out the name of their country or their mother: they were the youngest. The older men waited for death with an impassive or sardonic air, without deigning to plead or complain: others demanded to be killed on the battlefield: but we passed by these wretched men, able to bring them neither the vain mercy of assistance, nor the cruel mercy of despatch.’

Such is Monsieur de Ségur’s tale. Anathema to the victories which are not won in defence of the motherland, and which only serve to feed a conqueror’s vanity!

The Guard, composed of twenty-five thousand elite troops, was not involved in the Battle of Borodino: Bonaparte refused to use them, giving various pretexts. Contrary to custom, he kept away from the firing, and could not follow the manoeuvres with his own eyes. He sat or walked about close to a redoubt taken the previous day: when he was told of the death of one of his generals, he made a gesture of resignation. This display of impassiveness caused some astonishment; Ney exclaimed: ‘What’s he doing behind the army? There, only reverses reach him, not success. Since he no longer wages war on his own behalf, and is no longer a general, since he wants to play the Emperor everywhere, let him return to the Tuileries and leave us to be generals on his behalf.’ Murat swore that on that great day he no longer recognised Napoleon’s genius.

Uncritical admirers have attributed Napoleon’s torpor to the worsening of the illness from which, they assure us, he was then suffering; they affirm that he was often obliged to dismount , and would often remain motionless, his forehead pressed against a cannon. That may be so: a temporary indisposition may have contributed at that time to a lessening of his energy; but given that he regained that energy in his campaign in Saxony and his famous campaign in France, one needs to find another explanation for his inaction at Borodino. What! You confess in your bulletin that it would have been easy to manoeuvre and force the enemy to abandon his excellent position; but that would have delayed the action; and you, who had enough mental agility to condemn so many thousands of our soldiers to death, you had not the physical strength to order your Guard even to go to their aid? There can be no other explanation of this than the very nature of the man: adversity had arrived; its first touch chilled him. Napoleon’s greatness was not of that quality which thrives on misfortune; only success left him in full possession of his faculties: he was not made for disaster.

Book XXI: Chapter 4: The French advance – Rostopchin – Bonaparte on Salutation Hill – The View of Moscow – Napoleon enters the Kremlin – The Burning of Moscow – Bonaparte reaches the Petrovsky Palace with difficulty – Rostopchin’s proclamation – A halt among the ruins of Moscow – Bonaparte’s pastimes

BkXXI:Chap4:Sec1

Between the Moskva and Moscow, Murat joined battle outside Mojaïsk. The town was entered: ten thousand dead and dying were found there; the dead were thrown through the windows to make room for the living. The Russians fell back in good order towards Moscow.

On the evening of the 13th of September, Kutuzov had summoned a council of war: all his generals declared that ‘Moscow was not the motherland.’ Buturlin (Histoire de la campagne de Russie), the same officer whom Alexander sent to the Duc d’Angoulême’s headquarters in Spain, and Barclay in his Mémoire justificatif, give the reasons which motivated the council’s opinion. Kutuzov proposed a ceasefire to the King of Naples, while the Russian soldiers passed through the ancient capital of the Tsars. The ceasefire was agreed, since the French wanted to preserve the city intact; Murat alone pressed the enemy rear-guard hard, and our grenadiers trod in the footsteps of the retreating Russian grenadiers. But Napoleon was far from the success which he though to be within reach: behind Kutuzov was Rostopchin.

Count Rostopchin was the Governor of Moscow. His vengeance promised to drop from heaven: a huge balloon, constructed at great expense, was to float above the French army, pick out the Emperor among his thousands, and fall on his head in a shower of fire and steel. In trial, the wings of the airship broke; forcing him to renounce his bombshell from the clouds; but Rostopchin kept the flares. The news of the disaster at Borodino had reached Moscow while the rest of the Empire was rejoicing over what one of Kutuzov’s bulletins called a victory. Rostopchin issued various proclamations in rhythmic prose; he said:

‘Come, my friends the Muscovites, let us march too! We’ll gather a hundred thousand men, we’ll take an icon of the Holy Virgin, and a hundred and fifty cannon, and put an end to all this.’

He advised the inhabitants to arm themselves simply with pitchforks, since a Frenchman weighed no more than a sheaf of corn.

We know that Rostopchin later denied all part in the burning of Moscow; we also know that Alexander never commented on the matter. Did Rostopchin wish to avoid the reproaches of the merchants and nobles whose fortunes had perished? Was Alexander afraid of being called a Barbarian by the Institute? This is such a wretched age, and Bonaparte had monopolized all its splendours to such a degree, that when something worthy happened, everyone repudiated it and disclaimed all responsibility.

The burning of Moscow remains a historic decision which preserved the freedom of one nation and contributed to the liberation of several others. Numantia has not lost its right to the admiration of mankind. What matter that Moscow burned! Had it not been burnt seven times before? Is it not brilliantly restored today, despite Napoleon’s twenty-first bulletin prophesying that the burning of its capital would put Russia back a hundred years? ‘Moscow’s very misfortune,’ as Madame de Staël so admirably said, ‘regenerated the Empire: that holy city perished like a martyr whose blood once shed grants new strength to the brothers who survive him.’ (Dix années d’exil)

Where would the nations be, if Bonaparte, from the heights of the Kremlin, had covered the world with his despotism as if with a funeral pall? The rights of the human race are supreme. For myself, if the world were a combustible globe, I would not hesitate to set fire to it if it were a question of freeing my country. Nevertheless, it takes nothing less than the superior interests of human liberty for a Frenchman, his head covered in mourning and his eyes full of tears, to bring himself to speak of a decision which proved fatal to so many Frenchmen.

Count Rostopchin, an educated and spiritual man, has been to Paris: in his writings, his thoughts are hidden beneath a certain buffoonery; he was a sort of civilized Barbarian, an ironic even depraved poet, capable of generous inclinations, while scornful of nations and kings: Gothic churches admit grotesque decorations amidst their grandeur.

The rout of Moscow had begun; the roads to Kazan were covered with fugitives, on foot, in carriages, alone or accompanied by servants.

An omen had momentarily raised everyone’s spirits: a vulture was caught in the chains which supported the cross on the principal church; Rome, like Moscow, would have seen Napoleon’s captivity in that omen.

With the arrival of long convoys of wounded Russians at the city gates, all hope evaporated. Kutuzov had promised Rostopchin that he would defend the city with the ninety-one thousand men left to him: you have read how the council of war obliged him to retreat. Rostopchin remained alone.

Night fell: messengers knocked mysteriously on every door, announcing that all must leave, that Nineveh was doomed. Inflammable material was piled in public buildings and markets, in shops and private houses; fire-fighting equipment was removed. Then Rostopchin ordered the prisons to be opened: from a filthy gang of prisoners a Russian and a Frenchman were brought forward; the Russian, a member of a sect of German Illuminati, was accused of attempting to betray his country and of having translated the French proclamation; his father ran up; the Governor granted him a few moments to bless his son: ‘Me, bless a traitor!’ the old Muscovite cried, and cursed him instead. The prisoner was handed to the people and killed.

‘As for you,’ Rostopchin said to the Frenchman, ‘you were right to desire your countrymen’s arrival: go free. Tell your comrades that there was only a single traitor in all of Russia, and he has been punished.’

The other malefactors who were released, were given, with their freedom, orders to set the city on fire, when the moment arrived. Rostopchin was the last to leave Moscow, as a ship’s captain is last over the side in a shipwreck.

BkXXI:Chap4:Sec2

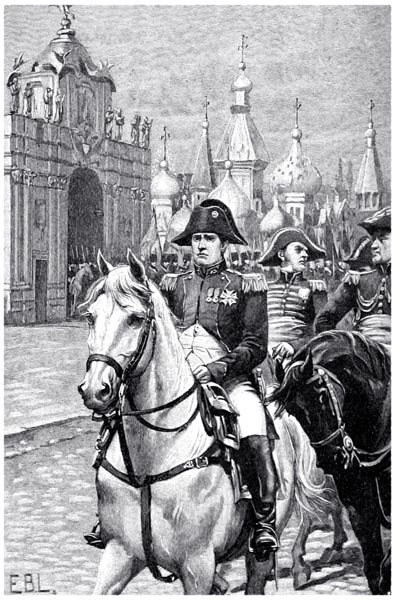

Napoleon, on horseback, had joined the vanguard. One height remained to be crossed; it overlooked Moscow as Montmartre does Paris; it was called Salutation Hill, because the Russians prayed there in sight of their holy city, as the pilgrims do on catching sight of Jerusalem. Moscow of the gilded cupolas, as the Slav poets say, shone in the sunlight, with its two hundred and ninety-five churches, its fifteen hundred castles, its wooden houses in yellow, green and pink: it lacked only cypress trees and the Bosphorus. The Kremlin formed part of this mass, covered with polished and painted metal. Amongst elegant villas of brick and marble, the Moskva flowed through parks planted with fir, the palm-trees of that region: Venice in the days of its glory was not more brilliant, rising from the Adriatic wave. It was at two in the afternoon, on the 14th of September, that Bonaparte, by the light of a sun glittering with polar diamonds, saw his new conquest. Moscow, like a European princess at the edge of his Empire, adorned with all the riches of Asia, seemed there for marriage with Napoleon.

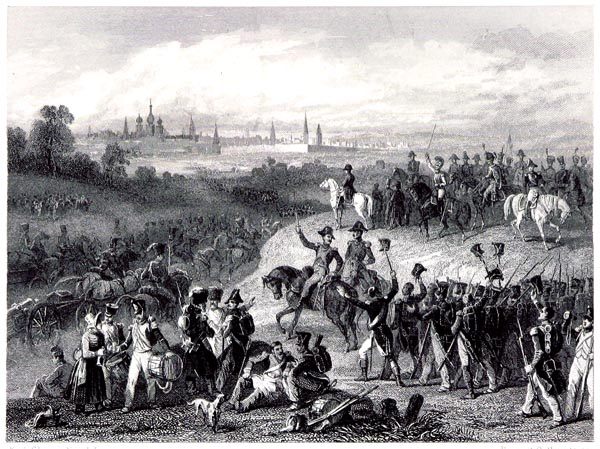

‘L'Armée Fançaise Devant Moscou’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p179, 1845)

The British Library

Shouts rose: ‘Moscow! Moscow! cried our soldiers; they clapped their hands yet again; in the days of our past glory, in victory or defeat, they were wont to shout: ‘Long live the King!’ ‘It was a wonderful moment,’ says Lieutenant-Colonel de Baudus, ‘that in which the magnificent panorama presented by the whole of that immense city suddenly offered itself to my gaze. I will always remember the emotion that manifested itself in ranks of the Polish division; it struck me especially in that it was revealed in an impulsive moment of religious feeling. On seeing Moscow, whole regiments threw themselves to their knees and thanked the God of Armies for having led them in victory to the capital of their bitterest enemy.’

The acclamation ceased; they descended silently towards the city; no deputation emerged from the gates to present the keys in a silver bowl. All signs of life had been suspended in that great city. Moscow fell mute before the stranger: three days later she had vanished’ the Circassian of the North, the beautiful intended, had lain down on her funeral pyre.

While the city was still standing, Napoleon, marching towards it, cried: ‘So, this is the famous city! and he gazed: Moscow, abandoned, resembled the city mourned over in Lamentations. Eugène and Poniatowski had already climbed the walls; some of our officers entered the city; they returned to tell Napoleon: ‘Moscow is deserted!’ – Moscow deserted, that’s unlikely! Bring me the boyars.’ There were no boyars, only a few beggars in hiding. The streets were abandoned, the windows shuttered: no smoke rose from the houses from which torrents would soon pour. There was not the slightest sound. Bonaparte shrugged his shoulders.

Murat, advancing as far as the Kremlin, was greeted with howls of fury from the prisoners set free in order to defend their country: he was forced to blast the gates open with cannon.

Napoleon was taken to the Dorogomilov Gate; he installed himself in one of the first houses in the suburb, took a ride along the Moskva, and saw no one. He returned to his quarters and appointed Marshal Mortier Governor of Moscow, General Durosnel Commandant, and Monsieur de Lesseps, in his capacity as Quarter-Master General, as Head of Administration. The Imperial Guard and the troops were in full-dress to parade before the absent populace. Bonaparte soon learnt that the city was positively threatened with disaster. At two in the morning he was told that a fire had broken out. The conqueror left the Dorogomilov suburb and took shelter in the Kremlin: this was on the morning of the 15th of October. He experienced an instant of joy on entering Peter the Great’s Palace; his pride assuaged he wrote a few words to Alexander, by the light of the bazaar which had just caught fire, just as the defeated Alexander had previously written to him from the field of Austerlitz.

‘Napolean's Entry into Moscow’

Battles of the Nineteenth Century - Archibald Forbes, Andrew Hilliard Atteridge (p332, 1901)

Internet Archive Book Images

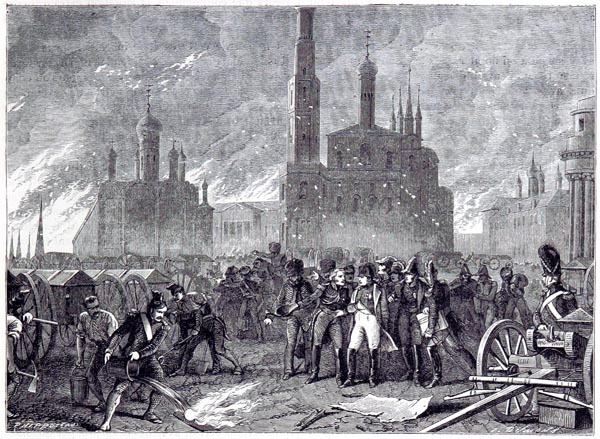

In the bazaar long rows of locked and shuttered shops could be seen. At first the fire was contained; but during the second night it broke out everywhere; star-shells hurled into the air by rockets burst and fell in sheaves of light over the palaces and churches. A fierce northerly drove the sparks before it and scattered flakes of fire over the Kremlin: it contained a powder magazine; an artillery-park had been left under Bonaparte’s very windows. Our soldiers were driven from quarter to quarter by the eruptions from the volcano. Gorgons and Medusas, torch in hand, rushed through the livid crossroads of this inferno; others poked the fires with spears of tarred wood. Bonaparte, in the halls of this new Pergamos, rushed to the windows, crying: ‘What amazing resolution! What people! They are Scythians!’

A rumour spread that the Kremlin was mined: servants discovered they were ill, while the soldiers resigned themselves to their fate. The mouths of the various fires outside grew wider, approached each other, and met: the tower of the Arsenal, like a tall taper, burnt in the midst of a blazing sanctuary. The Kremlin was nothing but a black island against which broke a sea awash with fire. The sky, reflecting the glow, seemed as if traversed by the flickering lights of the aurora borealis.

The third night fell; one could scarcely breathe in the suffocating atmosphere: twice fuses had been attached to the building housing Napoleon. How to escape? The flames had merged blocking the gates of the citadel. After searching around, a postern was found leading to the Moskva. The conqueror and his retinue slipped away through this exit to safety. Around him in the city, arches were collapsing with a roar, and belfries from which showers of molten metal poured, were leaning, breaking and falling. Beams, rafters and roofs, cracking, sparking, and crumbling, plunged into a Phlegethon whose burning waves they sent leaping in a million golden spangles. Bonaparte made his escape over the cold embers of a district already reduced to ashes: he gained Petrovsky, the Tsar’s palace.

‘Incendie de Moscou - le Général Lariboisière Force Napoléon à Quitter le Kremlin, Menacé d'un Formidable Explosion’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Vol 03 - Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p173, 1865)

The British Library

General Gourgaud, criticising Monsieur Ségur’s work, accuses the Emperor’s orderly of being in error: indeed, it seems proven, by Monsieur de Baudus’ narrative, he being aide-de-camp to Marshal Bessières, and who himself acted as guide to Napoleon, that the latter did not escape by a postern, but left by the main doorway of the Kremlin. From the shores of St Helena, Napoleon recalled the Scythian city in flames: ‘Never,’ he said, ‘despite all their poetry, could the fictional accounts of the burning of Troy equal the reality of that of Moscow.’

Remembering that catastrophe later, Bonaparte further wrote: ‘My evil genius appeared, to announce my destiny, which I met with on the Island of Elba.’ Kutuzov had first set out towards the east; then he fell back towards the south. His night march was partially lit by the distant fires of Moscow, from which rose a dismal noise; one would have said that the great bell, which had never in fact been mounted because of its immense weight, had been magically suspended at the summit of a burning steeple to sound the death-knell. Kutuzov reached Voronovo, Count Rostopchin’s estate; scarcely had he set eyes on that splendid residence when it vanished in the depths of a fresh conflagration. On the iron door of the church one could read this inscription, the scritta morta (last words), from the proprietor’s hand: ‘I have improved this land for eighteen years, and lived here happily in the bosom of my family; the inhabitants of this place, to the number of seventeen hundred and twenty, have left at your approach, and I have set fire to my house so that it might not be soiled by your presence. Frenchmen, I have left you my two houses in Moscow with contents worth half a million roubles. Here you will find nothing but ashes.

ROSTOPCHIN.’

Bonaparte at first had admired the Scythian fires as a spectacle that suited his imaginings; but soon the evil which that catastrophe had worked on him chilled him and made him revert to his abusive diatribes. Sending Rostopchin’s letter to France, he added: ‘Rostopchin seems insane; the Russians consider him a kind of Marat.’ He who does not understand greatness in others will not comprehend it on his own behalf when the time for sacrifice arrives.

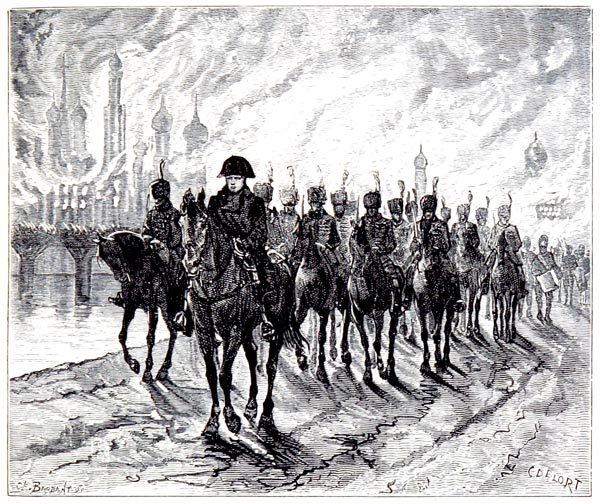

‘L'Armée Quittant le Kremlin’

L'Histoire de France Depuis 1789 Jusqu'en 1848, Racontée à mes Petits-Enfants, par M. Guizot. Leçons Recueillies par Madame de Witt, Vol 02 - François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (p267, 1878)

The British Library

Alexander understood adversity without becoming despondent. ‘Retreat,’ he wrote, ‘when Europe encourages us with its regard! Let us serve it as an example; let us salute the hand which chose us to be first among nations in the cause of virtue and liberty.’ An invocation to the Lord On High follows.

A style in which the words God, virtue and liberty are found is powerful: it pleases men, reassures and consoles them; how superior it is to those affected phrases, sadly imprinted with pagan locutions, and Turkish fatalism: it was to be, they had to be, fatality has overcome them! sterile phraseology, always idle, even when applied to the greatest of actions.

BkXXI:Chap4:Sec3

Leaving Moscow during the night of the 15th of September, Napoleon re-entered it on the 18th. While returning he had come across camp-fires burning in the mud, fed with mahogany furniture and gilded panelling. Around these fires in the open air were blackened, mud-stained soldiers, dressed in rags, lying on silk sofas or sitting in velvet armchairs, with Kashmir shawls, Siberian furs, or golden fabrics from Paris as carpets, in the mud, beneath their feet, and eating blackened paste, or the blood-stained flesh of dead horses, from silver dishes.

Irregular looting having started, it was regularized; each regiment fell upon the quarry in turn. Peasants driven from their huts, Cossacks, and enemy deserters, roamed around the French camps and fed on whatever our squads had left behind. Everything that could be carried away was taken; soon, overloaded with their spoils, our soldiers threw them away, on happening to remember that they were fifteen hundred miles from home.

The expeditions they undertook, searching for provisions, produced some pathetic scenes: one French squad brought back a cow; a woman approached them, accompanied by a man carrying a child of a few months old in his arms; they pointed to the cow that had just been taken from them. The mother tore at the wretched clothes covering her breasts, to show she had no milk left; the father made a gesture as if to break the child’s head on a stone. The officer made his men return the cow, and he adds: ‘The effect this scene had on my soldiers was such that, for a long time, not a single word was spoken in the ranks.’

Bonaparte’s dreams had altered; he announced that he wished to march on St Petersburg; he had already mapped out the route; he explained the excellence of his new plan, the certainty of entering the empire’s second capital: ‘What had he to do from now on with ruins? Was it not sufficiently glorious for him to have been enthroned in the Kremlin?’ Such were Napoleon’s fresh fantasies; the man touched madness, but his dreams were still those of a great spirit.

‘We are only fifteen day’s march from St Petersburg,’ says Monsieur Fain: ‘Napoleon thinks of falling back towards that capital.’ Instead of fifteen day’s march, at that time, in those circumstances, one ought to say two months. General Gourgaud adds that all the information from St Petersburg indicated fear regarding Napoleon’s movements. It is certain that in St Petersburg no one doubted his victory if he appeared; but they prepared to leave him the carcass of a second city, and a retreat to Archangel was planned. You cannot subjugate a nation whose final citadel is the Pole. Moreover the English fleet, penetrating the Baltic in the spring, would simply have destroyed St Petersburg once taken.

But while Bonaparte’s unbridled imagination toyed with the idea of an expedition to St Petersburg, he was seriously occupied with the contrary idea: his belief in his dreams was not such as to rob him of all good sense. His dominating thought was to carry a peace treaty to Paris signed in Moscow. In that way he would avoid the dangers of a retreat, he would have accomplished an astonishing feat, and he would return to the Tuileries olive branch in hand. After the first note he had written to Alexander on arriving at the Kremlin, he had neglected the opportunity of renewing his advances. In an affable discussion with a Russian field officer, Monsieur de Toutelmine, assistant director of the Foundlings Hospital in Moscow, a hospital miraculously spared by the fire, he had let slip words favourable to reaching an accommodation. Through Monsieur Jacowleff, brother of the former Russian Minister in Stuttgart, he wrote directly to Alexander, and Monsieur Jacowleff undertook to hand this letter to the Tsar personally. Finally General Lauriston was sent to Kutuzov: the latter promised his good offices towards a peace negotiation; but he refused to grant General Lauriston a safe-conduct for St Petersburg.

Napoleon remained convinced that he exercised the same power over Alexander that he had exercised at Tilsit and Erfurt, and yet, on the 21st of October Alexander wrote to Prince Michael Larcanowitz: ‘I learn, to my extreme dissatisfaction, that General Bennigsen has met with the King of Naples........All the specifics contained in the orders which were addressed to you by myself should have convinced you that my resolution is unshakeable, and that at this time no proposal by the enemy could commit me to terminating the war, and so weakening the sacred duty of avenging the motherland.’

The Russian generals took advantage of the self-esteem and naivety, of Murat, who commanded the vanguard; continually delighted by the Cossacks’ attentiveness, he borrowed jewels from his officers to give them as presents to his courtiers from the Don; but the Russian generals, far from desiring peace, dreaded it. Despite Alexander’s resolve, they knew their Emperor’s weakness, and feared the persuasiveness of ours. In order to achieve vengeance, it was merely a matter of gaining a month, in order to await the first frost: the Muscovite Christians’ prayers were supplications to heaven to bring on the storms.

General Wilson arrived, in his capacity as English emissary to the Russian Army; he had already crossed Bonaparte’s path in Egypt. Fabvier, for his part, had rejoined our army of the north from that of the south. The English urged Kutuzov to attack, and everyone knew that the news Fabvier brought was far from good. At two ends of Europe, the two nations who alone fought for their freedom, threatened the head of Moscow’s conqueror. No reply came from Alexander; the French troops lingered; Napoleon’s anxiety grew; the peasants warned our soldiers: ‘You don’t know our climate,’ they said, ‘in a month’s time the cold will make your nails drop off.’ Milton, whose great fame embellishes everything, in his Brief History of Moscovia, says, as naively, that it is: ‘so cold in winter, that the very sap of their wood fuel burning on the fire, freezes at the brand’s end, where it drops.’

Bonaparte, believing that one reverse step would lesson his prestige and cause the fear of his name to evaporate, could not bring himself to back down: despite the warnings of imminent peril, he remained there, waiting all the while for a reply from St Petersburg; he, who had conducted himself with such contempt, sighed for a few wretched words from the defeated. In the Kremlin he occupied himself with regulations for the Comédie-Française; he spent three evenings completing this majestic work; with his aides he discussed the merit of some new verses received from Paris; those around him admired the great man’s sang-froid, while the wounded from his latest battles were still dying in terrible pain, and while, by delaying a few more days, he condemned to death the hundred thousand men who remained. The servile stupidity of the age tries to pass this pitiful affectation off as the design of an incommensurable spirit.

Bonaparte toured the Kremlin buildings. He descended and then re-ascended the staircase on which Peter the Great had the Strelitz guards murdered; he walked up and down the banquet hall where Peter had the prisoners assembled, lashing out at the head of one of them between each glass, proposing to his guests, princes and ambassadors, to divert themselves in the same way. Men were then broken on the wheel, and women buried alive; they hung two thousand of the Strelitz whose bodies were left dangling from the walls.

BkXXI:Chap4:Sec4

Instead of instructions regarding the theatre, Bonaparte would have done better to write to the Senate (Conservateur) the letter which Peter wrote to the Moscow Senate from the banks of the Pruth: ‘I announce to you, that misled by bad advice, and without it being my fault, I find my camp here surrounded by a force four times larger than mine. If I am taken, you are no longer to consider me as your lord and Tsar, nor to take account of any order which may be sent to you in my name, even if you recognise it as being in my own hand. If I perish, you must choose the worthiest of you as my successor.’

A note of Napoleon’s addressed to Cambacérès contained unintelligible orders: there was some deliberation, and though the signature on the note was a lengthened form of a classical name, the writing being recognised as Bonaparte’s, it was decreed that the unintelligible orders be executed.

The Kremlin contains a Double Throne for a pair of brothers: Napoleon chose not to share his. In one of the rooms a stretcher could be seen, shattered by a cannonball, on which the wounded Charles XII had been carried at the Battle of Pultava. Always eclipsed in the ranks of generous feeling, did Bonaparte remember, on visiting the tombs of the Tsars, that on feast-days they were covered with magnificent palls; that when a subject had some favour to solicit, he laid his petition on one of the tombs, and only the Tsar had the right to remove it?

These requests of the unfortunate, presented by death to majesty, were not to Napoleon’s taste. He was occupied with other cares; partly out of a desire for deception, partly because it was his nature, he planned, as he did on leaving Egypt, to summon actors to Moscow, and he declared that an Italian singer would be arriving. He despoiled the Kremlin churches, filled his wagons with sacred ornaments and icons, along with the crescents and horse-tails captured from the Mohammedans. He had the huge cross taken down from Ivan the Great’s bell-tower; his plan was to install it on the dome of the Invalides: it would have complemented the masterpieces of the Vatican with which he had adorned the Louvre. While they were detaching this cross, crows flew about it cawing: ‘What do those birds want with me?’ Bonaparte asked.

The fatal moment approached: Daru raised objections to various plans sketched out by Bonaparte: ‘What path should we take, then?’ the Emperor exclaimed. – ‘Remain here; turn Moscow into a vast fortified camp; spend the winter here; salt down the horses that we are unable to feed; and wait for spring: our reinforcements and the Lithuanian army will relieve us and complete the conquest.’ – ‘That’s a lion’s counsel,’ replied Napoleon; but what would Paris say? France will not countenance my absence.’ – ‘What do they say of me in Athens? Alexander the Great would ask.

He plunged again into uncertainty: should he go, or should he stay? He was unsure. Countless deliberations followed. Finally a skirmish at Vinkovo, on the 18th of October, persuaded him to leave the ruins of Moscow with his army: that same day, without fuss or noise, without a backward look, wishing to avoid the direct route to Smolensk, he took one of the two roads to Kaluga.

For thirty-five days, like those fearsome African serpents that sleep when they have dined, he had lost sight of himself: this it would seem was the time needed to alter the fate of such a man. During that period the star of his destiny sank in the sky. At last he awoke, caught between winter and a burned-out capital; he slipped away from ruin: it was too late; a hundred thousand men were condemned to die. Marshal Mortier, commanding the rear-guard, was ordered, on his retreat, to blow up the Kremlin.

Book XXI: Chapter 5: Retreat

BkXXI:Chap5:Sec1

Bonaparte, deceiving himself or wishing to deceive others, wrote a letter to the Duc de Bassano, on the 18th of October, reproduced by Monsieur Fain: ‘By the end of the first few weeks of November,’ he writes, ‘I will have brought my troops back to the square bounded by Smolensk, Mohilov, Minsk and Vitebsk. I am decided on this manoeuvre, since Moscow is no longer a position of military value; I am about to locate another, more favourable to the start of the next campaign. Operations will then be directed towards Petersburg and Kiev.’ A pitiful boast, if it were merely a question of gaining acceptance for a lie; but with Bonaparte, the idea of conquest, despite being contrary to all logic, always offered the possibility of being honest.

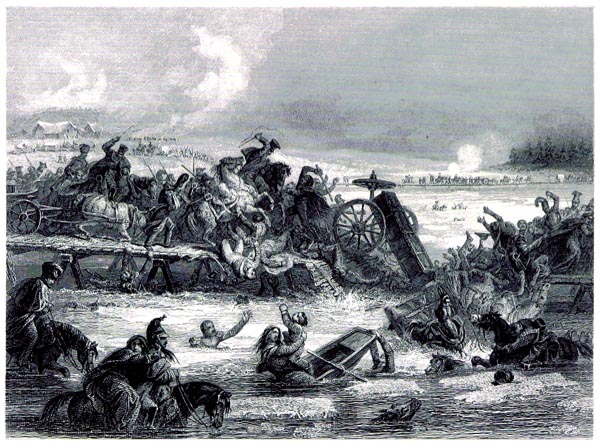

They retreated towards Maloyaroslavets: due to the volume of baggage and badly-harnessed vehicles, after three days march they were still only thirty miles from Moscow. They intended to outpace Kutuzov: indeed Prince Eugène’s vanguard reached Fominskoe before him. There were still a hundred thousand infantrymen left when the retreat began. The cavalry was almost non-existent apart from the three thousand five hundred Horse-guards. Our troops, having reached the new road to Kaluga on the 21st of October, entered Borowsk on the 22nd, and on the 23rd Delzons’ division occupied Maloyaroslavets. Napoleon was delighted; he thought they had escaped.

On the 23rd of October at half-past one in the morning, the earth shook: a hundred and eighty three thousand pounds of gunpowder, placed beneath the Kremlin, tore apart the palace of the Tsars. Mortier, who blew up the Kremlin, was destined to meet Fieschi’s infernal machine. What worlds passed between those two explosions, in time and among men!

‘Explosion du Kremlin. Dessiné par Martinet’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p817, 1888)

The British Library

After this deafening roar, a loud cannonade sounded through the silence, from the direction of Maloyaroslavets: to the same degree that Napoleon had longed to hear this noise on entering Russia, he dreaded hearing it on leaving. An aide-de-camp to the Viceroy announced a Russian general attack: during the night Compans and Gérard arrived to assist Prince Eugène. Many men perished on both sides; the enemy managed to ride along the Kaluga Road and completely shut off access to the route we had hoped to follow. There was no option but to fall back on the road to Mojaïsk and re-enter Smolensk along the track of our previous misfortune.

Napoleon stayed that night at Gorodnia, in a humble house where the officers attached to various generals were unable to find shelter. They gathered under Bonaparte’s window; it lacked curtains or shutters; light could be seen escaping, while the officers who remained outside were plunged in darkness. Napoleon was sitting in his little room, his head bowed on his hands; Murat, Berthier, and Bessières stood near him, silent and motionless. He gave no orders, and mounted his horse on the morning of the 25th of October, in order to inspect the Russian army’s positions.

He had barely left when a cascade of Cossacks swept almost to his feet. The living avalanche had crossed the Luzh, and had been hidden from sight, at the edge of a wood. Everyone drew his sword, including the Emperor. If these marauders had been possessed of greater courage, Bonaparte would have been captured. In the burning town of Maloyaroslavets, the streets were strewn with bodies, half-charred, slashed, crushed; mutilated by the wheels of the guns, which had passed over them. In order to continue the push towards Kaluga, it had been necessary to fight a second battle; the Emperor considered it inappropriate. There amounts to a disagreement in this regard between the supporters of Bonaparte and the friends of the Marshals. Who gave the advice to pursue once more the original route taken by the French? Evidently it was Napoleon: it cost him little to pronounce great and fatal judgements; he was used to it.

Returning to Borowsk next day, on the 26th, near to Vereia, General Wintzingerode and his aide-de-camp Count Nariskin were brought before the leader of our armies: they had been caught entering Moscow prematurely. Bonaparte lost his temper: ‘Let them shoot this general!’ he shouted, beside himself: ‘he is a deserter from the Kingdom of Wurtemberg; it belongs to the Confederation of the Rhine.’ He poured out invective against the Russian nobility and ended with these words: ‘I will go to St Petersburg, I will hurl that city into the Neva.’, and suddenly he ordered the burning of a castle that could be seen on the heights: the wounded lion lashing out, foaming, at everything around him.

Nevertheless, in the midst of his wild anger, while he was giving Mortier the order to destroy the Kremlin, he obeyed, at the same moment, his double nature; he wrote to that same Duke of Treviso in sentimental phrases; aware that his missives would become known, he urged him with paternal tenderness to save the hospitals; ‘since that is how,’ he added, ‘I treated Saint-Jean-d’Acre.’ Now, in Palestine, he had the Turkish prisoners shot, and with no opposition from Desgenettes, he poisoned the sick! Berthier and Murat saved Prince Wintzingerode.

Kutuzov however pursued us sluggishly. When Wilson urged the Russian general to act, the general replied: ‘Let the snows come.’ On the 29th of October, they reached the Moskva’s fatal heights: a shout of grief and surprise escaped our army. A vast slaughterhouse was revealed, displaying forty thousand corpses in varying stages of decay. The orderly rows of bodies still seemed to maintain military discipline; detached skeletons in front, on levelled hillocks, indicated the officers and dominated the ranks of dead. Everywhere were broken weapons, shattered drums, fragments of cuirasses and uniforms, and torn standards, scattered among the trunks of trees cut down by cannonballs a few feet from the ground; it was the Grand Redoubt of Borodino.

At the heart of this motionless destruction something was seen moving: a French soldier who had lost both legs made his way through this cemetery which seemed to have disgorged its entrails. The body of a horse brought down by a shell had served to nourish this soldier: he lived there, gnawing away at his cave of flesh; the putrefying flesh of the dead nearby served him in place of bandages to dress his wounds and ointment to soothe his stumps. The terrifying remorse that glory brings dragged itself towards Napoleon: Napoleon did not linger.

The silence of the soldiers, hurrying away from cold, hunger and the enemy, was profound; they thought they might soon resemble those comrades whose remains they could see. Amongst the remnant nothing could be heard but heaving breath and the involuntary tremor of noise from battalions in retreat.

Further on was the Abbey of Kotloskoy which had been turned into a hospital; all medical assistance was lacking: there was only enough life left there to witness death. Bonaparte, reaching the place, burnt the wood of his shattered wagons. When the army took to the road again, those in mortal agony rose in order to reach the threshold of their last sanctuary, allowing themselves to collapse on the roadway, holding out their failing arms to their comrades who were departing: they seemed at the same time to entreat them and seek to delay them.

At every instant the sound of explosions rang out from the ammunition boxes they had been forced to abandon. The camp-followers flung the dying into the ditches. The Russian prisoners, who were being escorted by foreigners in the French service, were dispatched by their guards: executed in a regular manner, their brains were spilled from their skulls. Bonaparte had led all Europe all along with him; every language was spoken in his army; every manner of cockade and flag could be seen there. Italians, forced to fight, were defeated with the French; Spaniards had maintained their reputation for courage: Naples and Andalusia were for them no more than the regret for a sweet dream. It is said that Bonaparte was only defeated by Europe in its entirety, and that is fair; but the fact is forgotten that Bonaparte only conquered with Europe’s aid, with force or willingness as his allies.

Russia alone resisted a Europe led by Napoleon; France, alone and defended by Napoleon, fell to a Europe in a different mode; but it should be said that Russia was defended by her climate, and that Europe marched regretfully behind its master. France, on the contrary, was defended neither by its climate nor its decimated population; it had only courage and the remembrance of glory.

Indifferent to his soldiers’ miseries, Bonaparte was only concerned with his own interests: in camp, his conversation turned to those ministers who had sold themselves, he said, to the English, ministers who had fomented this war; unwilling to confess that this war was his responsibility alone. The Duke of Vicenza who persisted in bringing trouble upon himself by his noble conduct, indulged in an outburst, faced with the flattery prevalent in their bivouac. He shouted: ‘What atrocious cruelty! So this is the civilisation we have brought Russia!’ To Bonaparte’s amazed retort, he made a gesture of anger and incredulity and withdrew. That man whom the least contradiction sent into fits of fury tolerated Caulaincourt’s rudeness in expiation of the letter he had once made him carry to Ettenheim. When you have committed an action deserving of reproach, heaven in punishment imposes witnesses on you: it was vain for the tyrants of the ancient world to make them vanish; descending to the underworld, those witnesses entered the bodies of Furies and returned.

BkXXI:Chap5:Sec2

Passing through Gjatsk, Napoleon pressed forward to Viasma; he carried on beyond, not having met with the enemy he feared he might encounter there. On the 3rd of November he reached Slavkovo: there he learnt that a battle had been fought at Viasma against Miloradovich’s troops, fatal to us: our soldiers, our officers, wounded, arms in slings, heads swathed in bandages, in a miracle of valour, threw themselves at the enemy cannon.

These successive actions in familiar places, these layers of dead upon dead, these battles echoed by other battles, would have doubly immortalised these fatal fields, if oblivion had not swiftly cloaked our dust. Who thinks of those countrymen left behind in Russia? Are those rustics content to have been at the great battle beneath the walls of Moscow? Perhaps only I on autumn evenings, watching birds from the North flying high in the sky, recall having seen the grave of our compatriots. Industrial companies have transported their cauldrons and furnaces into the wilderness; the bones have been converted into animal-black: whether from dog or man, varnish fetches the same price, and gleams no less brightly for being produced from the obscure or the glorious. There you see the respect we have for the dead these days! Behold the sacred rites of the new religion! Diis Manibus: to the gods of the shades. Fortunate companions of Charles XII, you were not visited by these sacrilegious hyenas! In winter the ermine appears among your virginal snows and in summer the flowering mosses of Pultava.

BkXXI:Chap5:Sec3

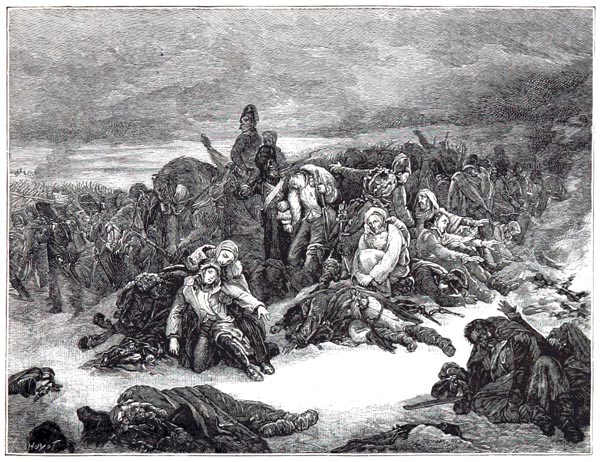

On the 6th of November 1812 the thermometer fell to eighteen degrees (Réamur) below zero: everything vanished under a blanket of snow. The soldiers lacking boots felt their feet dying; their muskets, whose very touch burnt, fell from their stiff purple fingers; their hair bristled with hoar-frost, their beards with their frozen breath; their wretched clothes turned into frosty cassocks. They fell, and the snow covered them; they formed little ridges of graves on the ground. No one knew which way the rivers flowed; they had to break the ice to discover the direction to take. Lost in the wilderness, the various army corps lit fires to signal to and recognise one another, as ships in peril fire cannon in their distress. The fir-trees were transformed into motionless crystal, rising up here and there, candelabra at these obsequies. Crows, and packs of master-less white dogs, followed this procession of corpses, at a distance.

It was galling, after each day’s march, to be obliged, at some deserted halt, to take the precautions suited to a strong, well-equipped host, to post sentries; occupy key positions, and station pickets. During the sixteen hour nights, battered by gusts from the north, our troops did not know where to sit or lie down; the trees chopped down with all their alabaster coating, refused to catch fire; to melt a little snow was as much as they could manage, and then mix a spoonful of rye-flour into it. They were no sooner stretched out on the frozen ground than Cossack howls echoed through the woods; the enemy’s light artillery rumbled; our soldiers’ fast was saluted like a banquet at which kings sit down to dine; cannon-balls rolled among the famished guests like loaves of iron. At dawn, which was barely followed by daybreak, the beat of a frost-coated drum, or a hoarse note from a trumpet could be heard: nothing could have been sadder than this mournful reveille, calling to arms warriors whom it could no longer rouse. The growing light revealed circles of infantrymen dead and frozen around extinguished fires.

A few survivors remained; they advanced, towards unknown horizons which, ever-receding, vanished into the fog at every step. Under a shivering sky, as if weary of last night’s storms, our thinning ranks crossed region after region, forest on forest, in which an Ocean seemed to have left its foam among the dishevelled branches of the birch-trees. Among these woods there was not even a sign of that sad little bird of winter who sings, like me, among the leafless bushes. If I suddenly find myself again, by analogy, in the presence of former days, oh my comrades (soldiers are all brothers), your sufferings too recall my youth, when, retreating in advance of your track, I, so wretched and abandoned, journeyed over the heath-land of the Ardennes.

The Russian Grand Army followed ours: the latter was organised in several divisions sub-divided into columns: Prince Eugène commanded the vanguard, Napoleon the centre, Marshal Ney the rear-guard. Hindered by various obstacles and skirmishes, these corps failed to keep a distance between them: sometimes they overtook one another; sometimes they marched on a parallel course, often without seeing each other or being able to communicate, through lack of cavalry. The Tartars, riding small ponies whose manes swept the ground, gave our soldiers harassed by these gadflies of the snow no rest, day or night. The landscape was changing: where a river had been visible, one found a torrent suspended by bonds of ice from the steep sides of its ravine. ‘In a single night,’ Bonaparte writes (Records of St Helena), ‘we lost thirty thousand horses: we were forced to abandon almost all the artillery, still five hundred pieces strong; we could take neither munitions nor provisions. For lack of horses, we could not carry out any reconnaissance, nor send cavalry forward to reconnoitre the route. The soldiers lost their courage and their wits, and fell, in the confusion. The slightest set-back alarmed them. Four or five men were enough to fill a whole battalion with dread. Instead of keeping together, they wandered off separately seeking the nearest fire. Those who were sent ahead, as scouts, abandoned their task, and went to some house, in order to find the means to warm themselves. They spread out on all sides, estranged from their corps, and easily fell prey to the enemy. Others fell asleep, lying on the ground: a little blood flowed from their nostrils, and they died while sleeping. Thousands of soldiers perished. The Poles saved some of their horses, and a small amount of artillery; but the French and the soldiers of other nations were not the same men. The cavalry suffered most particularly. Of forty thousand men I do not believe three thousand were allowed to escape.’

‘Retraite de Russie. Tableau d'Ary Scheffer’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p829, 1888)

The British Library

And you, who recounted this under the glittering sun of another hemisphere, were you merely a witness to all this wretchedness?

On that very day (the 6th of November) when the thermometer fell so low, the first courier seen for many a long day arrived like a lost screech-owl: he carried evil tidings of Malet’s conspiracy. This conspiracy revealed something profound about Napoleon’s fortunes. According to General Gourgaud, what made the most impression on the Emperor was the over-abundant proof ‘that monarchical principles as applied to his monarchy had flung out such shallow roots that the great functionaries, at the news of the Emperor’s death, had already forgotten that, the sovereign being dead, there was another left to succeed him.’

Bonaparte on St Helena (Las Cases’ Mémorial) remarked that he had said to his Court at the Tuileries, in speaking of Malet’s conspiracy: ‘Well, Gentlemen, you considered your revolution over; you thought me dead: but what of the King of Rome, your oaths, your principles, your doctrines? You make me shudder for the future!’ Bonaparte reasoned logically; it was a question of his dynasty: would he have found the reasoning as correct if it had been a question concerning Saint Louis’ race?

Bonaparte learned of the Paris incident in the midst of the wilderness, among the ruins of an all but vanished army, whose blood the snow drank; Napoleon’s rule rooted in force was annihilated in Russia along with his force, while a single man sufficed to cast it in doubt in the capital: without religion, justice, and liberty, there is no rule.

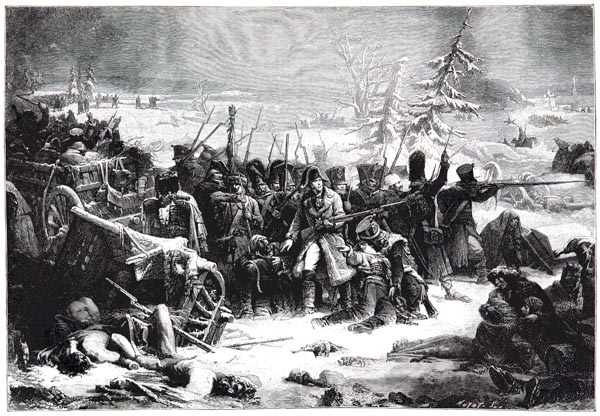

At almost the very moment that Bonaparte learned of what had happened in Paris, he received a letter from Marshal Ney. This letter informed him that: ‘the best of the army were asking why they alone were fighting to protect the flight of the rest; why the eagle continued to protect and kill; why it was necessary to die in battalions, since there was nothing left to do but flee?’

‘Retraite de Russie. Le Maréchal Ney Soutient l'Arrière-Garde de la Grande Armée. Tableau de Yvon, au Musée de Versailles’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p833, 1888)

The British Library

When Ney’s aide-de-camp tried to go into the specific grievances, Bonaparte interrupted him: ‘Colonel, I did not ask you for details.’ – This expedition to Russia was a foolish extravagance which all civil and military authorities within the Empire condemned: the victories and sufferings marked out by the route of their retreat discouraged and embittered the soldiers: in that path of ascent and descent, Napoleon might equally have found a symbol of the two segments of his life.

Book XXI: Chapter 6: Smolensk – The Retreat continued

BkXXI:Chap6:Sec1

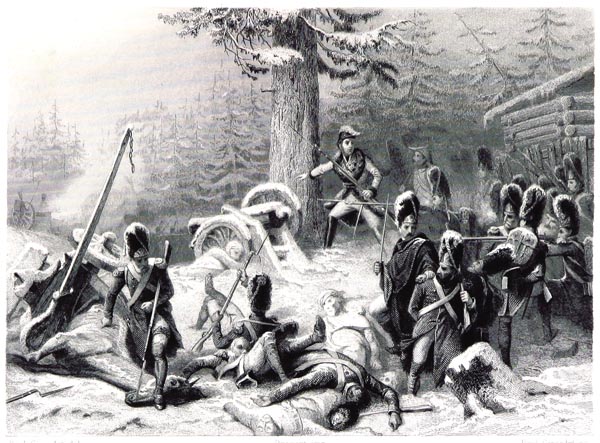

On the 9th of November, they finally reached Smolensk. An order from Bonaparte forbade anyone entering prior to the sentry-posts being occupied by the Imperial Guard. The soldiers outside gathered at the foot of the walls; the soldiers inside held the gates closed. The air was rent by the imprecations of the excluded and desperate, dressed in dirty Cossack smocks, patched greatcoats, ragged cloaks and uniforms, blankets and horsecloths, their heads covered by caps, knotted handkerchiefs, battered shakos, and twisted and dented helmets; all this spattered with blood and snow, riddled with bullets or slashed by sabre-cuts. With haggard, drawn faces, and sombre glittering eyes, they gnashed their teeth and gazed up at the ramparts, with the air of those mutilated prisoners, who, under Louis the Fat, carried their amputated left hand in their right: they might have been taken for frenzied mourners or demented patients escaped from the madhouse. The Young and Old Guards arrived; they entered a city ravaged by fire on our previous visit. Shouts rose, aimed at the privileged band: ‘Will the army never have aught but their leavings?’ The famished cohorts ran wildly towards the shops as if in spectral insurrection; they were driven off and began fighting: the dead were left in the streets, the women and children, and the dying, in the carts. The air stank with the corruption of a multitude of decomposed corpses; some soldiers were touched with imbecility or madness; some with hair tangled or on end, blaspheming or shaking with crazed laughter, fell dead. Bonaparte vented his anger on a wretched supplier not a single of whose orders had been fulfilled.