François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XX: Napoleon: Italy, Germany, Spain, The Papal States: to 1812

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XX: Chapter 1: The position of France on Bonaparte’s return from the Egyptian Campaign

- Book XX: Chapter 2: The Consulate: A fresh invasion of Italy – The Thirty-Day Campaign – The Victory of Hohenlinden – The Peace of Luneville

- Book XX: Chapter 3: The Peace of Amiens – The breaking of the Treaty – Bonaparte created Emperor

- Book XX: Chapter 4: Empire: The Coronation – The Kingdom of Italy

- Book XX: Chapter 5: The Invasion of Germany – Austerlitz – The Peace Treaty of Pressbourg – The Sanhedrin

- Book XX: Chapter 6: The Fourth Coalition – Prussia vanishes – The Berlin Decree – War against Russia continues in Poland – Tilsit – A plan to divide the world between Napoleon and Alexander – Peace

- Book XX: Chapter 7: The War in Spain – Erfurt – The Emergence of Wellington

- Book XX: Chapter 8: Pius VII – The Union of the Roman States with France

- Book XX: Chapter 9: The sovereign Pontiff’s protest – He is removed from Rome

- Book XX: Chapter 10: The Fifth Coalition – The Capture of Venice – The Battle of Essling – The Battle of Wagram – Peace signed in the Emperor of Austria’s palace – Divorce – Napoleon marries Marie-Louise – The birth of the King of Rome

- Book XX: Chapter 11: Plans and preparations for the War on Russia – Napoleon’s embarrassment

- Book XX: Chapter 12: The Emperor undertakes his Russian expedition – Objections – Napoleon’s mistake

- Book XX: Chapter 13: The meeting in Dresden – Bonaparte reviews his army and arrives on the banks of the Niemen

Book XX: Chapter 1: The position of France on Bonaparte’s return from the Egyptian Campaign

BkXX:Chap1:Sec1

I left England some months after Napoleon had left Egypt; we returned to France at almost the same moment, he from Memphis; I from London: he had seized towns and kingdoms; his hands were full of powerful realities; I had still only captured chimaeras.

What had taken place in Europe during Napoleon’s absence?

The war in Italy had recommenced, in the Kingdom of Naples and in Sardinia; Rome and Naples were occupied for a while; Pius VI, a prisoner, was brought to die in France; and a treaty of alliance was concluded between the cabinets of Petersburg and London.

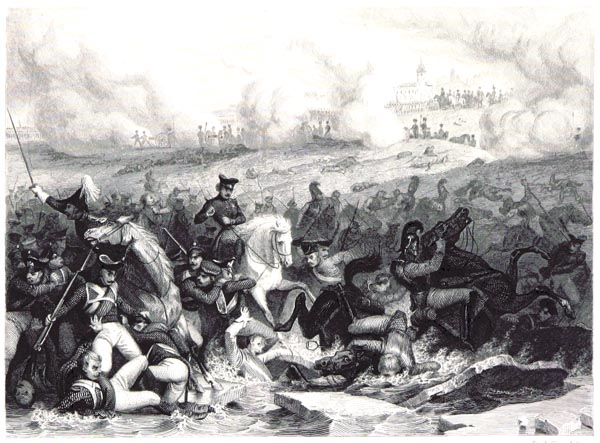

There was a second continental coalition against France. On the 8th of April 1799, the Congress of Rastatt broke up, and the French plenipotentiaries were assassinated. Suvorov, arriving in Italy, beats the French at Cassano. The citadel of Milan surrenders to the Russian general. One of our armies, commanded by General Macdonald, forced to evacuate Naples, survives with difficulty. Masséna defends Switzerland.

Mantua succumbs after a blockade of seventy-two days and a siege of twenty. On the 15th of October 1799, General Joubert is killed at Novi, leaving the field free for Bonaparte; he would have been destined to play the role of the latter: alas for those crossed by fatal misfortune, witness Hoche, Moreau and Joubert! Twenty thousand English descending on Den Helder, where the Dutch fleet in 1794 had been partly frozen in the ice, and our cavalry charged and took the vessels, remain there ineffectually. The twenty-eight thousand Russians, to which battle and exhaustion had reduced Suvorov’s army, traversing the Saint-Gothard on the 24th of September, are engaged in the Valley of the Reuss. Masséna saves France at the battle of Zurich. Suvorov, re-enters Germany, blames the Austrians and retires to Poland. Such was the position of France when Bonaparte re-appeared, overthrew the Directory and established the Consulate.

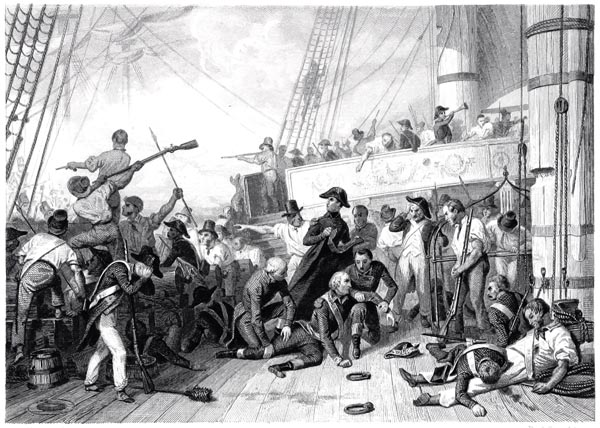

‘Conquest of the Fleet at Den Helder by the French, 1795’

Lejeune, 1795 - 1800

The Rijksmuseum

Before continuing further, I will mention something of which the reader will already be aware: I am not writing a detailed life of Bonaparte; I am sketching an abridgement and summary of his actions; I depict his battles, I do not describe them; one can find such descriptions everywhere, from Pommereul, who gave us his Italian Campaign, to our usual critics and commentators on battles in which they have fought, to the foreign tacticians, English, Russian, German, Italian and Spanish. Napoleon’s general bulletins and his secret despatches provide the very uncertain thread of these narrations. The works of General Jomini furnish a better source of information: the author is especially credible since he has demonstrated his knowledge in his Traité de la grande tactique and his Traité des grands opérations militaries. An admirer of Napoleon to the point of bias, attached to Marshal Ney’s staff, he provides a critical military history of the Revolutionary campaigns: he saw with his own eyes the war in Germany, Prussia, Poland and Russia up to the taking of Smolensk; he was present in Saxony in the fighting of 1813; from there he subsequently went over to the Alliance; he was condemned to death by a council of war of Bonaparte’s, and at the same moment named as aide-de-camp to the Emperor Alexander. Attacked by General Sarrazin in his Histoire de la guerre de Russie et d’Allemagne, Jomini replied. Jomini had at his disposal material filed at the War Ministry and in other royal archives; he was a thorough witness of our army’s retreat, having served to lead their advance. His narrative is lucid and threaded by fine and judicious comments. Pages have often been borrowed from him without acknowledgement; but I am no copyist nor have I any ambition to claim the renown of being an unknown Caesar, lacking only a helmet in order to subjugate the world once more. If I had chosen to assist the memory of the veterans, by manoeuvring around maps, jogging around battlefields filled with peaceful crops, making extracts from various documents, piling up description on ever-identical description, I would have accumulated volume after volume, I would have acquired a reputation for hard work, but at the risk of burying beneath my labours, my self, my readers, and my hero. Being only a humble soldier, I bow before the science of Vegetius; I have not assumed my public to be officers on half-pay; and the lowliest corporal knows more about it than I do.

Book XX: Chapter 2: The Consulate: A fresh invasion of Italy – The Thirty-Day Campaign – The Victory of Hohenlinden – The Peace of Luneville

BkXX:Chap2:Sec1

To make certain of the position he occupied, Napoleon needed to surpass his own previous miracles.

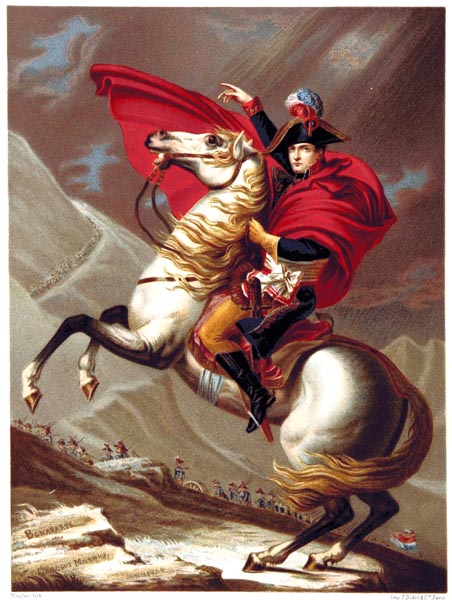

From the 25th to the 30th of April 1800, the French cross the Rhine, Moreau at their head. The Austrian army beaten four times in eight days fall back on one side on Voralberg, and on the other on Ulm. Bonaparte crosses the Great Saint Bernard Pass on the 16th of May; and on the 20th the Little Saint Bernard, the Simplon, the Saint Gothard, the Mont Cenis, and the Mont Genève, are assaulted and carried; we penetrate Italy through three defiles, considered impregnable, with caves for bears, cliffs for eagles. The army seize Milan on the 2nd of June, and the Cisalpine Republic is re-organised; but Genoa is obliged to surrender after a memorable siege, withstood by Masséna.

‘Le Premier Consul Franchissant le Mont Saint Bernard, Tableau de David, Musée de Versailles’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p13, 1888)

The British Library

The occupation of Pavia and the fortunate affair of Montebello precede the victory at Marengo.

A defeat begins that victory: Lannes’ and Victor’s exhausted corps cease fighting and abandon the ground; the battle begins again with four thousand infantrymen led by Desaix supported by Kellerman’s cavalry brigade; Desaix is killed. Kellerman’s charge decides success; on a day that serves to confirm Mélas’ ordinariness.

Desaix, gentleman of Auvergne, second-lieutenant in the Breton regiment, aide-de-camp to General Victor de Broglie, commanded a division of Moreau’s army in 1796, and went to the Orient with Bonaparte. His character was selfless, uncomplicated and easy-going. When the treaty of El-Arish released him, he was detained by Lord Keith in the lazaretto at Livorno. ‘When the lights were extinguished,’ says Miot his companion on the voyage, ‘our general told us stories of ghosts and brigands; he shared our pleasures and calmed our quarrels; he had a great love of women and only wished to earn their love through his love of glory.’ On disembarking in Europe, he received a letter from the First Consul summoning him to his side; it was waiting for him, and Desaix said; ‘Poor Bonaparte is covered with glory, and he is not happy.’ Reading in the papers about the march of the army reserve, he wrote: ‘He will leave us nothing to do.’ Bonaparte left him the task of winning him victory, and then dying.

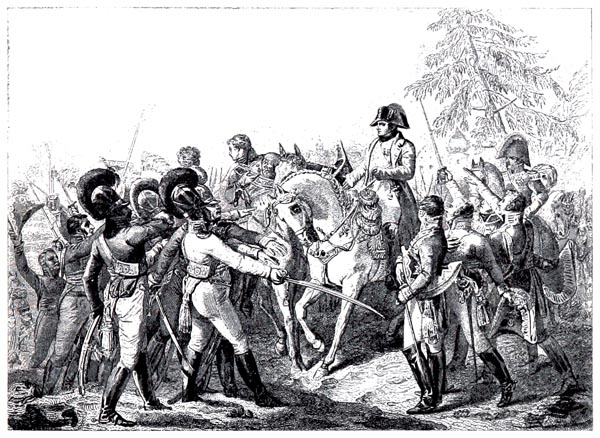

‘Desaix à Marengo’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p17, 1845)

The British Library

Desaix was buried among the Alpine summits, at the hospice of Mont Saint-Bernard, as Napoleon was buried on the heights of St Helena.

Kléber, assassinated, met his death in Egypt on the same day that Desaix found his in Italy. After the departure of the commander-in-chief, Kléber with eleven thousand men defeated a hundred thousand Turks under the command of the Grand Vizier, at Heliopolis; an exploit with which Napoleon had nothing to compare.

‘Kléber’

L'Histoire de France Depuis 1789 Jusqu'en 1848, Racontée à mes Petits-Enfants, par M. Guizot. Leçons Recueillies par Madame de Witt, Vol 01 - François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (p477, 1878)

The British Library

On the 15th of June, the Convention of Alexandria was signed. The Austrians retreated to the left bank of the lower Po. The fate of Italy was decided in this campaign known as the Thirty Days.

The victory of Höchstadt won by Moreau appeased the spirit of Louis XIV. However the armistice between Germany and Italy, concluded after the battle of Marengo, was denounced on the 20th of October 1800.

BkXX:Chap2:Sec2

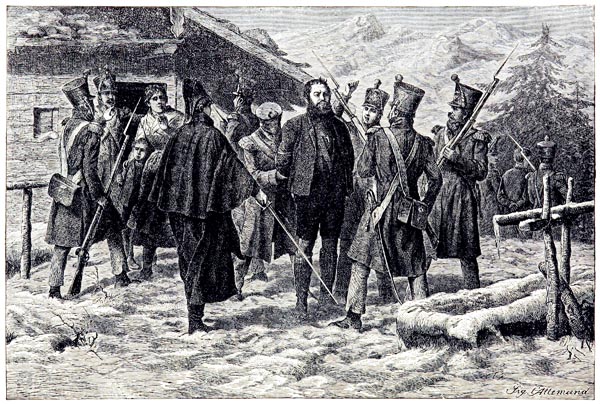

The 3rd of December brought the victory of Hohenlinden in the midst of a snow-storm; a victory obtained yet again by Moreau, a great general commanded by another great genius. The compatriot of Du Guesclin marched on Vienna. At twenty-five leagues from that capital, he concluded the suspension of hostilities at Steyer, with Archduke Charles. After the battle of Pozzolo, and the crossing of the Mincio, the Adige and the Brenta, the Peace Treaty of Lunéville was signed, on the 9th of February 1801.

‘Moreau à Hohenlinden’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p33, 1845)

The British Library

And it was scarcely nine months since Napoleon had been on the banks of the Nile! Nine months were enough for him to overthrow a popular revolution in France and crush the absolute monarchies of Europe.

I am not sure if it is to this period that one ought to attribute an anecdote found in informal memoirs, or even whether the anecdote is worth the trouble of recalling; but there is no lack of tales concerning Caesar: life is not all on one level, sometimes one rises, often one falls: Napoleon received into his bed, in Milan, an Italian girl, sixteen years old, lovely as the dawn; in the middle of the night he sent her away, just as he would have ordered a bouquet of flowers to be tossed from a window.

On another occasion, one of these spring flowers slipped into the same palace as he; she entered at three in the morning, kept the witching hour, and chanced her youth in the jaws of the lion; more benevolent on that day.

Those pleasures, far from representing love, had no real power over the man of death: he would have set fire to Persepolis on his own account, not for the joys of a courtesan. ‘Francis I, ‘says Tavannes, ‘saw to business when he had finished with women: Alexander saw to women when he had finished with business.’

Women in general, and mothers in particular, detested Bonaparte; they had little liking for him as women, since they were not liked: lacking delicacy, he insulted them, or only sought them out momentarily. He inspired a degree of imaginative passion after his fall: in those days, for a female heart, the poetry of destiny was less seductive than that of misfortune; there are flowers among the ruins.

Following the example of Saint-Louis’ order of chivalry, the Legion of Honour is created: through that institution a ray of the old monarchy passes, and introduces a barrier to the new equality. The transfer of Turenne’s remains to the Invalides brought Napoleon esteem; Captain Baudin’s expedition carried his fame around the globe. All that might have harmed the First Consul failed: he defeats a plot by guilty parties on the 18th Vendémiaire and escapes the Infernal machine of the 3rd Nivôse; Pitt retires; Tsar Paul dies; Alexander succeeds him; Wellington has not yet come to notice. But India moves to take from us our control of the Nile; Egypt is attacked via the Red Sea, while the Capitan-Pasha lands there from the Mediterranean. Napoleon stirs Empires: all the earth is involved with him.

Book XX: Chapter 3: The Peace of Amiens – The breaking of the Treaty – Bonaparte created Emperor

BkXX:Chap3:Sec1

The peace preliminaries between France and England, agreed in London on the 1st of October 1801, were converted into a treaty at Amiens. The Napoleonic world was not yet fixed; its boundaries changed with the ebb and flow of the tide of our victories.

It was about then that the First Consul named Toussaint-Louverture Governor for life of Santa Domingo, and incorporated the Isle of Elba within France; but Toussaint, treacherously taken, was to die in a harsh fortress in the Jura, while Bonaparte provided himself with a prison at Porto-Ferrajo, in order to meet the needs of the Emperor of the world when he no should longer possess anywhere else.

On the 6th of May 1802, Napoleon is elected Consul for ten years, and shortly Consul for life. He finds himself cramped by the overriding domination that the peace with England has accorded him: without being embarrassed for a moment by the Treaty of Amiens, without a thought for the fresh wars into which his decision will plunge him, under the pretext of the non-evacuation of Malta, he annexes the provinces of Piedmont to the French State, and, because of the disturbances arising in Switzerland, occupies it. England breaks with us: that rupture takes place between the 13th and the 20th of March 1803, and on the 22nd of May the unofficial decree appears requiring the arrest of all English people trading or travelling in France.

Bonaparte invades the Electorate of Hanover on the 3rd of June: in Rome, I was then closing the eyes of a little-known woman.

On the 21st of March 1804 occurs the death of the Duc d’Enghien: I have described it to you. On the same day, the Civil Code or Code Napoleon is decreed in order to teach us to respect the law.

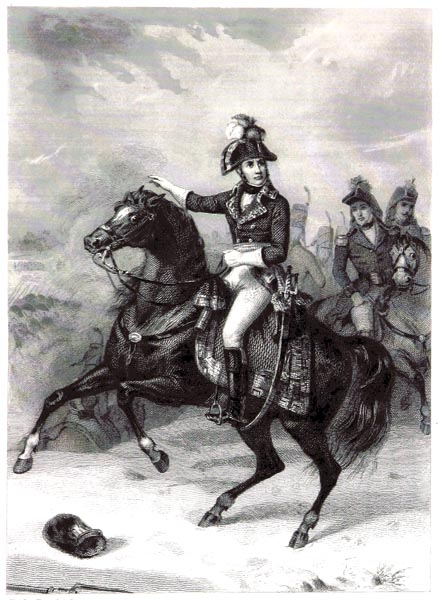

Forty days after the death of the Duc d’Enghien, on the 30th of April 1804, a member of the Tribunate named Curée presents a motion elevating Bonaparte to a position of supreme power, apparently because they are all dedicated to freedom: never has a more brilliant master been created at the suggestion of a more obscure slave.

The Senate (Sénat Conservateur) in its decree alters the Tribunate’s suggestion. Bonaparte imitates neither Caesar nor Cromwell: more assured regarding the crown, he accepts it. On the 18th of May he is proclaimed Emperor at Saint-Cloud, in the rooms from which he had himself driven the people, in the place where Henri III was assassinated, Henrietta of England was poisoned, Marie-Antoinette gathered fugitive joys which led here to the scaffold, and from where Charles X left for his last exile.

The speeches of congratulation flowed. Mirabeau in 1790 had said: ‘We provide a fresh example of that blind and unmotivated thoughtlessness which has led us, from age to age, into all the crises that have successively afflicted us. It seems that our eyes cannot be opened and that we have resolved to be, to the end of time, children who are sometimes rebels and always slaves.’

The plebiscite of the 1st of December 1804 is presented to Napoleon; the Emperor replies: ‘My descendants will command this throne for many years.’ When one beholds the illusions with which Providence cloaks the powerful, one is consoled by their short duration.

‘Napoleon Proclamé Empereur’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p81, 1845)

The British Library

Book XX: Chapter 4: Empire: The Coronation – The Kingdom of Italy

BkXX:Chap4:Sec1

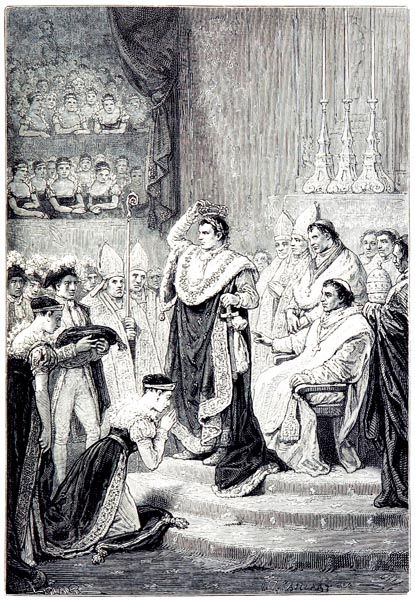

On the 2nd of December 1804 the consecration and coronation of the Emperor took place at Notre-Dame de Paris. The Pope uttered this prayer: ‘Eternal and Almighty God, who made Hazael Governor of Syria, and Jehu King of Israel, manifesting your will through the voice of the prophet Elijah; who equally anointed the heads of Saul and David with the sacred unction of kings, by the ministry of the prophet Samuel, pour the treasure of your grace and your blessings from my hands upon your servant Napoleon, so that despite our personal worthlessness, we may consecrate him Emperor today in your name.’ In 1797, Pius VII while still only Bishop of Imola had said: ‘Yes, my most dear friends, siate buoni cristiani, e sarete ottimi democrati (be good Christians and you will be the best of democrats). Moral virtue makes good democrats. The first Christians were animated by the spirit of democracy: God looked favourably on the works of Cato of Utica and the illustrious republicans of Rome.’ Quo turbine fertur vita hominum: on what whirlwind is the life of man borne away?

‘Le Sacre’

L'Histoire de France Depuis 1789 Jusqu'en 1848, Racontée à mes Petits-Enfants, par M. Guizot. Leçons Recueillies par Madame de Witt, Vol 01 - François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (p627, 1878)

The British Library

On the 18th of March, the Emperor announced to the Senate that he was accepting the iron crown that had been offered to him by the electoral college of the Cisalpine Republic: he was at that time the secret instigator of the wish and the public object of the wish. Little by little all of Italy embraced the rule of law; he attached the country to his diadem, as in the sixteenth century the leaders in warfare placed a diamond instead of a buttonhole in their hat.

‘Portrait of Emperor Napoleon I’

Workshop of Baron François Pascal Simon Gérard (c. 1805 - 1815)

The Rijksmuseum

Book XX: Chapter 5: The Invasion of Germany – Austerlitz – The Peace Treaty of Pressbourg – The Sanhedrin

BkXX:Chap5:Sec1

Europe, wounded, wished to apply a bandage to the wound: Austria adheres to the treaty of Petersburg concluded between Great Britain and Russia. Alexander and the King of Prussia have a meeting at Potsdam, which furnishes Napoleon with a subject for ignoble jest. The Third Continental Coalition is constructed. These coalitions are constantly reborn out of defiance and fear; Napoleon delighted in storms: he profited from them.

He makes a dash from the coast of Boulogne where he has decreed a column be erected, and has threatened Albion with a flotilla. An army organised by Davout streams towards the River Rhine. On the 1st of October 1805, the Emperor harangues his one hundred and sixty thousand soldiers: his speed of movement disconcerts Austria. There is fighting at the Lech, at Wertingen, at Günzburg. On the 17th of October, Napoleon appears before Ulm; to Mack he issues the order: ‘Lay down your arms!’ Mack and his thirty thousand men obey. Munich surrenders; the River Inn is passed, Salzburg taken, the Traun crossed. On the 13th of November, Napoleon enters one of those capitals he will re-visit time and time again: he traverses Vienna; chained by his own triumphs, he is drawn in their wake to the centre of Moravia to meet the Russians. On the left Bohemia rises; on the right Hungary; Archduke Charles hastens to Italy. Prussia, entering into the Coalition clandestinely and not yet having declared war, sends its Minister Haugwitz to carry an ultimatum.

BkXX:Chap5:Sec2

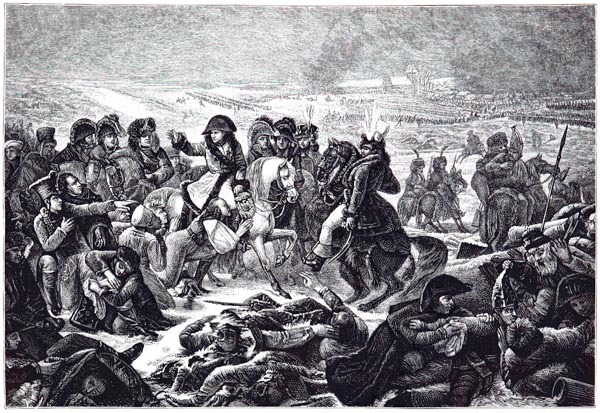

The morning of Austerlitz arrives, the 2nd of December 1805. The allies are waiting for a third Russian corps which is no more than eight day’s march distant. Kutuzov maintains that the risk of battle must be evaded; Napoleon by his manoeuvres forces the Russians to accept a fight: they are defeated. In less than two months the French, starting from the Channel, advancing beyond the capital of Austria, have wiped out Catherine’s legions. The Prussian foreign minister came to congratulate Napoleon at his headquarters: ‘Here we have,’ said the conqueror, ‘a compliment whose destination fate has altered.’ Francis II presented himself in turn at the fortunate soldier’s camp: ‘I welcome you,’ Napoleon told him, ‘in the only palace I have seen in the last two months.’ – ‘You know how to take advantage of this dwelling so well,’ replied Francis, ‘that it must please you.’ Is it worth the effort for equal powers to fight? An armistice is agreed. The Russians retreat in three columns, in stages, in the order decided by Napoleon. After the battle of Austerlitz, Bonaparte does scarcely anything but make mistakes.

‘Bataille d'Austerlitz’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p99, 1845)

The British Library

The peace treaty of Pressburg is signed on the 26th of December 1805. Napoleon makes kings of the Elector of Bavaria and the Elector of Wurtemberg. The republics Bonaparte had created he destroyed in order to transform them into monarchies; and perversely according to this method, on the 27th of December, at the palace of Schonbrunn, he declared that the dynasty of Naples had ceased to reign; merely in order to replace it with his own: at the sound of his voice, kings entered or leapt from windows. The designs of Providence were no less fulfilled than those of Napoleon: one saw both God and man on the march together. After his victory, Bonaparte commanded the building of the bridge of Austerlitz in Paris: the heavens commanded Alexander to pass over it.

BkXX:Chap5:Sec3

The war begun in the Tyrol was pursued, while it continued in Moravia. In the midst of prostrations, when you find someone standing you breathe once more: Hofer, the Tyrolean, did not capitulate like his master; but magnanimity moved Napoleon not a jot; it seemed stupidity to him or madness. The Austrian emperor abandoned Hofer. When I crossed Lake Garda, immortalised by Catullus and Virgil, I was shown the place where the warrior was shot: that taught me all I needed to know of the courage of the subject and the cowardice of the king.

‘Capture of Andrew Hofer, 1810’

Cassell's Illustrated Universal History, Vol 04 - Edmund Ollier (p546, 1893)

The British Library

On the 14th of January 1806, Prince Eugène married the daughter of the new king of Bavaria: thrones appeared on all sides in the family of the Corsican soldier. On the 20th of February the Emperor orders the restoration of the church of Saint-Denis; he dedicates the reconstructed vaults to be the tomb of the princes of his race, but Napoleon will not be buried there: man proposes his grave; God disposes.

Berg and Cleves are settled on Murat, the Two Sicilies on Joseph. A memory of Charlemagne comes to Napoleon’s mind, and the University is re-established.

The Batavian Republic, driven to admiration of princes, sends a message on the 5th of June 1806 begging that Napoleon deign to grant it his brother Louis as king.

The idea of associating Batavia with France in the guise more or less of union arose from covetousness without rhyme or reason: it was to prefer a little cheese-making province to the advantages which would result from alliance with a great and friendly kingdom, while increasing to no purpose European fears and jealousies: it was to confirm the English in possession of India, while obliging them, for their security, to guard the Cape of Good Hope and Ceylon which they seized as soon as we invaded Holland. The scene was set for endowing Prince Louis with the United Provinces: the Tuileries Palace was granted a re-enactment of Louis XIV’s display of his grandson Philip V at Versailles. On the following day a gala lunch was held in the Salon de Diana. One of Queen Hortense’s sons enters; Bonaparte says to him: ‘Darling, repeat the fable you have learned, for us.’ The child immediately proclaims: ‘The frogs ask for a king,’ and continues:

The frogs, rendered weary

Of their state of democracy,

Made so much sound and fury

Jove sent a king to them, to keep the peace.

Sitting behind the new sovereign of Holland, the Emperor, as was a habit of his, pinched his ear: though he was at the pinnacle of society, he was not always the best of company.

On the 12th of July 1806 the Treaty of the Confederation of the Rhine is signed; sixteen German princes separating from the Empire, joining together and with France: Napoleon takes the title of Protector of the Confederation.

On the 20th of July a peace treaty between France and Russia is signed, Francis II, following the Confederation of the Rhine States, on the 6th of August renounces the title of Emperor Elect of Germany, and becomes hereditary Emperor of Austria: the Holy Roman Empire collapses. That immense event was hardly noticed; after the French Revolution, everything seemed trivial; after the fall of Clovis’ throne, one scarcely heard the sound of the German throne disintegrating.

At the start of our Revolution, Germany had a multitude of sovereigns. Two principal monarchies tended to attract the various powers to them: Austria created by time, Prussia by a single man. Two religions divided the country and relied, for better rather than worse, on the tenets of the Treaty of Westphalia. Germany dreamed of political unity; but Germany lacked the political training to achieve freedom, as Italy lacked the military training to achieve that same freedom. Germany, with its ancient traditions, resembled those basilicas with multiple bell towers, which sin against the rules of art, but represent the majesty of religion and the power of the centuries no less.

The Confederation of the Rhine was a great unfinished work, which demanded, much of the time, special knowledge of the rights and interests of its peoples; it suddenly fell to pieces in the mind of him who conceived it: of that profound scheme, only the fiscal and military workings survived. Bonaparte, his first designs of genius spent, saw only money and soldiers; the tax-collector and the recruiting-officer took the place of greatness. The Michelangelo of politics and war, he left portfolios full of vast sketches.

Disturber of everything, Napoleon conceived a grand Sanhedrin about this time: that assembly did not award Jerusalem to him; but, by a series of consequences, it allowed world finance to fall into Jewish hands, and because of that allowed a fatal subversion of the social economy.

The Marquis of Lauderdale came to Paris to replace Mr Fox in the pending negotiations between France and England; diplomatic discussions which boil down to this comment of the English Ambassador to Monsieur de Talleyrand: ‘It is muck’ (I employ the more polite expression) ‘in a silk stocking.’

Book XX: Chapter 6: The Fourth Coalition – Prussia vanishes – The Berlin Decree – War against Russia continues in Poland – Tilsit – A plan to divide the world between Napoleon and Alexander – Peace

BkXX:Chap6:Sec1

During the course of 1806, the Fourth Coalition breaks up. Napoleon leaves Saint-Cloud, arrives at Mainz, and removes the enemy’s supplies from Saalburg. At Saalfeld, Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia is killed. At the twin battles of Auerstadt and Jena, on the 14th of October, Prussia vanishes; I no longer found it on my return from Jerusalem.

The Prussian Bulletin says it all in a sentence: ‘The King’s army has been beaten. The king and his brothers still live.’ The Duke of Brunswick soon died of his wounds: in 1792, his proclamation had roused France; he had saluted me on the road when, a poor soldier, I went to join the brothers of Louis XIV.

The Prince of Orange, and Mollendorf, with several other officers trapped in Halle, were granted permission to retreat by virtue of its capitulation.

Mollendorf, who was more than eighty years old, had been the companion of Frederick, who praised him in his History of his Time, as did Mirabeau in his Secret History. He was present at our disaster of Rosbach and was witness to our triumph at Jena: thus the Duke of Brunswick saw Assas die at Klosterkamp, and Ferdinand of Prussia fall at Auerstadt, guilty only of his hatred, born of a generous spirit, for the murder of the Duc d’Enghien. Those spectres from the old wars of Hanover and Silesia had endured the cannon fire of our two Empires: but the powerless shadows of the past could not prevent the march of the future; between the smoke from our old campfires and our new, they had appeared, and vanished.

Erfurt capitulates; Leipzig is seized by Davout; the passages of the Elbe are forced; Spandau yields; at Potsdam, Bonaparte takes Frederick’s sword captive. On the 27th of October 1806, the great King of Prussia, hears soldiers marching through the dust surrounding his empty palaces in Berlin, in a manner which reveals they are foreign grenadiers: Napoleon has arrived. While a monument to philosophy fell beside the Spree, I, in Jerusalem, was visiting an imperishable monument to religion.

Stettin, and Custrin surrender; there is a great victory at Lübeck; the capital of Wagria is carried by assault; Blücher, destined to reach Paris twice, falls into our hands. It is the story of Holland and its forty-six towns, captured during a campaign in 1672 by Louis XIV.

On the 21st of November the Berlin Decree establishing the Continental System appeared, a far-reaching decree which placed England under total ban, and was on the verge of being fulfilled; the decree seemed foolish, its results were immense. Regardless of the fact that, on the one hand, the continental blockade created the manufacturing industries of France, Germany, Switzerland and Italy, on the other it spread English trade throughout the globe: by embarrassing the governments within our alliance, it appalled industrial interests, fomented hatred, and contributed to the rupture between the Ministry of the Tuileries and that of St Petersburg. The blockade then was a questionable act: Richelieu would not have initiated it.

Silesia, following quickly on Frederick’s other States, is overrun. The war between France and Prussia has begun on the 9th of October: in seventeen days our soldiers, like a host of birds of prey, have glided through the defiles of Franconia, and over the waters of the Saal and Elbe; the 6th of December finds them before the Vistula. Since the 29th of December, Murat has been garrisoned in Warsaw, from which the Russians, who have arrived too late to aid the Prussians, have retreated. The Elector of Saxony, promoted to being a Napoleonic king, accedes to the Confederation of the Rhine, and agrees in case of war to supply a contingent of twenty thousand men.

BkXX:Chap6:Sec2

The winter of 1807 sees a suspension of hostilities between the French and Russian Empires; but those Empires are on a collision course and a change in their destiny can be observed. However, Bonaparte’s star is still in the ascendant despite his aberrations. On the 9th of February, 1807, he inspects the battlefield at Eylau: that place of carnage gives us one of Gros’ finest paintings, adorned with an idealised head of Napoleon. After fifty-one days of siege, Dantzig opens its gates to Marshal Lefebvre, who was continually saying to his gunners during the siege: ‘I know nothing about it; but make me a hole and I will pass through.’ The former sergeant in the French Guards became Duke of Dantzig.

‘Bataille d'Eylau, Tableau de Gros, Musée du Louvre’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p553, 1845)

The British Library

On the 14th of June 1807, Friedland costs the Russians seventeen thousand dead and wounded, as many prisoners, and seventy cannon; we paid too dearly for it; we had a different kind of enemy; we no longer achieved success except by freely opening French veins. Könisberg is taken; an armistice is concluded at Tilsit.

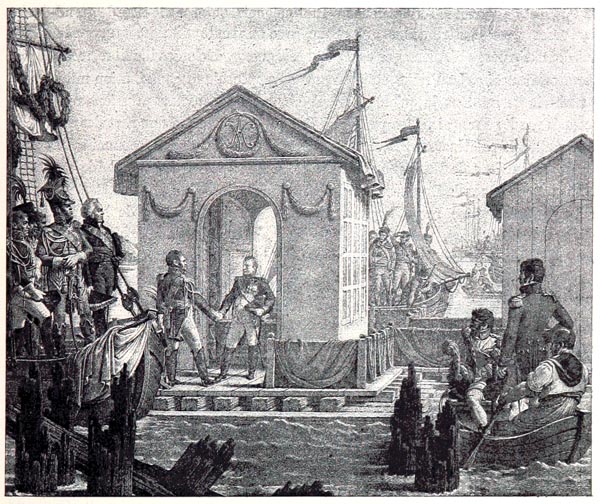

Napoleon and Alexander meet in a pavilion, on a raft. Alexander keeps the King of Prussia, whom one is scarcely aware of, on a leash: the fate of the world floats on the Niemen, where it will later be fulfilled. At Tilsit, a secret treaty in ten articles was discussed. By this treaty, European Turkey would be devolved to Russia, as well as whatever Muscovite conquest and weaponry could achieve in Asia. For his part, Bonaparte would become master of Spain and Portugal, would reunite Rome and its dependencies with the Kingdom of Italy, would cross to Africa, seize Tunis and Algiers, possess Malta, and invade Egypt, the Mediterranean being open only to French, Russian, Spanish and Italian vessels: these were the cantatas playing endlessly in Napoleon’s brain. A plan to invade India by land had already been agreed in 1800 between Napoleon and Emperor Paul I.

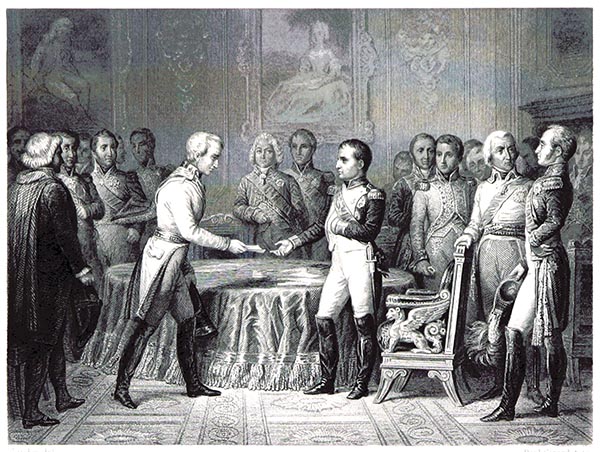

‘Entrevue de Napoléon Ier et de l'Empereur Alexandre, à Tilsit, Tableau de Gautherot, d'Après une Lithographie de Levilly’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p563, 1888)

The British Library

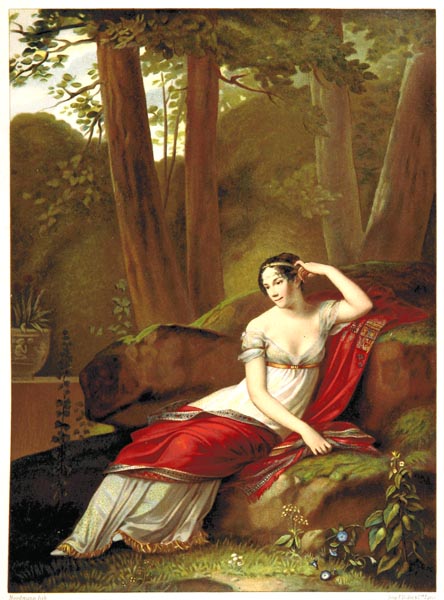

Peace is concluded on the 7th of July. Napoleon, hateful from the first to the Queen of Prussia, chose not to respond to her intercessions. She stayed, forlornly, in a little house on the right bank of the Niemen, and was honoured by being twice invited to the Emperors’ dinners. Silesia once invaded unjustly by Frederick, was given to Prussia: the rights of that previous injustice were respected; what was achieved by force was sacred. One region of Polish territory passed under the sovereignty of Saxony; Danzig’s independence was re-established; those killed in its streets and ditches counted for nothing: ridiculous and pointless wartime murders! Alexander recognised the Confederation of the Rhine, and Napoleon’s three brothers Joseph, Louis and Jérôme, as Kings of Naples, Holland, and Westphalia.

‘Portrait of Louise of Prussia’

Wilhelm Devrient, 1825 - 1899

The Rijksmuseum

Book XX: Chapter 7: The War in Spain – Erfurt – The Emergence of Wellington

BkXX:Chap7:Sec1

That fatality with which Bonaparte threatened kings threatened him also; almost simultaneously he attacks Russia, Spain and Rome: three doomed enterprises. You can read in The Congress of Verona, whose publication has preceded that of these Memoirs, the history of the invasion of Spain. The Treaty of Fontainebleau was signed on the 29th of October 1807. Junot, arriving in Portugal, declared that according to Bonaparte’s decree the House of Braganza had ceased to reign; to adopt the protocol: you will be aware that they still reign. They were so well informed in Lisbon as to what was happening in the world that John VI was only aware of this decree through an edition of the Moniteur carried there by chance, when the French army was already only three day’s march from the capital of Lusitania. It merely remained for the court to flee to those seas that welcomed Da Gama’s sails, and knew the verses of Camoëns.

At the moment that Bonaparte, to his misfortune, penetrated Russia in the north, the curtain rose in the south; other regions and scenes appeared, the sun of Andalusia, the palm trees of the Guadalquivir to which our grenadiers presented arms. Bullfights were on display in the arena, half-naked guerrillas in the mountains, and priests at prayer in the cloisters.

With the invasion of Spain, the character of the war altered; Napoleon found himself opposing England, his fatal genius; and it gave him a lesson in warfare: England destroyed Napoleon’s fleet at Aboukir, halted him at Saint-Jean-d’Acre, removed his remaining ships at Trafalgar, forced him to evacuate Iberia, seized the south of France as far as the Garonne, and awaited him at Waterloo: today they guard his grave at St Helena as they occupied his cradle of Corsica.

‘Trafalgar’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p95, 1845)

The British Library

On the 5th of May 1808, the Treaty of Bayonne, in the name of Charles IV cedes all that monarch’s rights to Napoleon: the confiscation of Spanish possessions, shows Bonaparte only as an Italian Prince, in the style of Machiavelli’s, except for the enormity of the theft. The occupation of the Peninsula reduces his forces positioned against Russia, of which he is still ostensibly a friend and ally, but towards which at heart he bears a hidden animosity. In his proclamation, Napoleon said to the Spaniards: ‘Your nation has been destroyed. I have seen your ills, I am going to remedy them; I wish your most distant cousins to preserve the memory of me and say: he was the regenerator of our country.’ Yes, he was the regenerator of Spain, but he uttered words he ill understood. A catechism of those days, composed by the Spanish, explained the true meaning of his prophecy:

‘Tell me, my son, who are you? – A Spaniard, by the grace of God. – Who is inimical to our happiness? – The Emperor of France. – What is he? – A miscreant. – How many natures has he? – Two, a human nature and a diabolical nature. – What gave birth to Napoleon? – Sin. – What torment does a Spaniard deserve who fails in his duty? – The death and infamy due to traitors. – Who are the French? – Former Christians turned heretics.’

Bonaparte, after his fall, condemned his Spanish foray in unequivocal terms: ‘I embarked,’ he said, ‘on that affair, on quite the wrong basis. Immorality is revealed by excessive licence, injustice by excessive cynicism, and the whole thing appears quite vile to me since I succumbed; for that assault appears merely nakedly shameful, when deprived of all the great and numerous potential benefits which filled out my plan. Posterity would advocate it yet, if I had succeeded, and with reason maybe, given its great and fortunate results. That project did for me. It destroyed my moral standing in Europe, and created a training ground for English soldiers. That wretched Spanish War was a genuine wound, the original cause of France’s misfortunes..

This confession, to re-deploy Napoleon’s phrase, is excessively cynical; but we are not deceived by it: in accusing himself, Bonaparte’s aim is to drive into the desert, under a curse, that devious assault, in order to summon up unreserved admiration for all his other actions.

With the battle lost to us at Bailén, the rulers of Europe, astonished at the Spanish success, blush at their own faint-heartedness. Wellington appears on the horizon for the first time, in the direction of the sunset; the English army disembarks on the 31st of July 1808 near Lisbon, and on the 30th of August the French troops evacuate Lusitania. In his satchel Soult had proclamations in which he titled himself Nicolas I, King of Portugal. Napoleon recalled the Grand-Duke of Berg from Madrid. He was pleased to effect a transmutation between his brother Joseph, and his brother-in-law, Joachim: he took the crown of Naples from the head of the former and set it on the head of the latter; with a flourish of his hand he deposited these adornments for the hair on the foreheads of two new kings, and off they went, in different directions, like two conscripts exchanging shakos.

BkXX:Chap7:Sec2

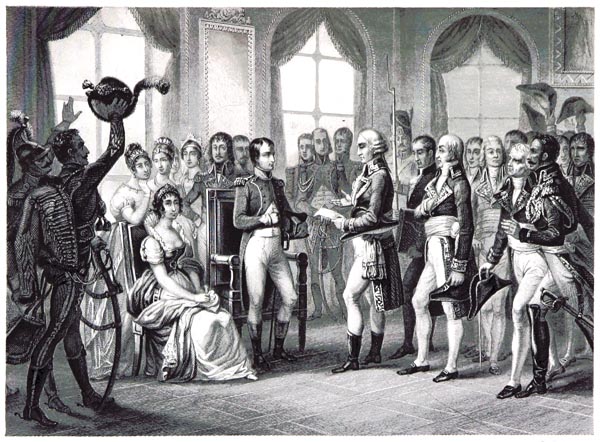

On the 27th of September, at Erfurt, Bonaparte gave one of the last demonstrations of his power; he thought to have fun with Alexander and made him drunk on praise. One general wrote: ‘We gave a glass of tincture of opium to the Tsar and, while he slept, we occupied ourselves elsewhere.’

A hut had been transformed into a theatre; two armchairs were placed in front of the orchestra for the two potentates; to left and right, fancy chairs for the monarchs; behind were benches for the princes: Talma, king of the stage, played before stalls full of kings. At the line:

‘A great man’s friendship is a blessing from the gods.’

Alexander took his great friend’s hand, bowed and said: ‘I have never felt it more deeply.’

‘Conférences d'Erfurt’

Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Faisant Suite à l'Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 12

Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p161, 1845)

The British Library

To Bonaparte’s eyes, at that time, Alexander appeared a fool; he made a laughing-stock of him; he admired him only when he considered him deceitful: ‘He is a Greek of the Later Empire,’ he would say, ‘one must set him at nought.’ At Erfurt, Napoleon affected the bold effrontery of a conquering soldier; Alexander dissimulated like a conquered prince: cunning grappled with lies, Occidental politics and Oriental politics maintained their masks.

London evaded the overtures of peace, and the Vienna ministry deceitfully decided on war. Abandoned once more to his imagination, Bonaparte made this declaration to the Legislative Corps, on the 26th of October: ‘The Emperor of Russia and I met one another at Erfurt: we are of one mind, and unalterably united in peace as in war.’ He added: ‘When I appear on that side of the Pyrenees, the terrified Leopard will seek the Ocean to escape disgrace, defeat or death.’ But the Leopard appeared on this side of the Pyrenees.

Napoleon who always believed what he wished, thought he would return to Russia, after having achieved the submission of Spain in four months, as has since happened to the Legitimacy, consequently he retired eighty thousand of the veterans of Saxony, Poland and Prussia; he himself marched on Spain; to the deputation from the city of Madrid he said: ‘There is no obstacle which can long delay the execution of my wishes. The Bourbons can no longer reign in Europe; no power under the influence of England can exist on the Continent.’

It was thirty-two years ago that this oracle was proclaimed, and that the taking of Zaragoza, on the 21st of February 1809, announced universal deliverance.

All that French gallantry was of no avail; the forests armed themselves, the bushes became enemies. Reprisals prevented nothing, because in those regions reprisals are expected. The business of Bailén, the defences of Girona and Cuidad-Rodrigo, signalled the resurrection of a people. La Romana, at the far end of the Baltic, sent his regiments to Spain, as formerly the Franks, fleeing the North Sea, landed triumphantly at the mouths of the Rhine. Conquerors of superior forces in Europe, we shed blood of lesser ones with that impious rage that France acquired from Voltaire’s buffooneries and the atheistic madness of the Terror. Yet it was those militias of the cloister who put an end to the success of our experienced soldiers; they did not wait to encounter these monks, on horseback like fire-breathing dragons, among the burning timbers of the Zaragoza buildings, loading their blunderbusses amidst the flames, to the sound of mandolins, to the rhythm of the bolero, and the requiem mass for the dead: the ruins of Saguntum applauded.

But nevertheless the secret of the Moorish palaces, changed into Christian basilicas, was penetrated; the pillaged churches lost their masterpieces by Velásquez and Murillo; fragments of the bones of Rodrigo at Burgos were disinterred; men were so filled with glory they did not fear to rouse the Cid’s ghost against them, just as they did not fear to irritate the shade of Condé.

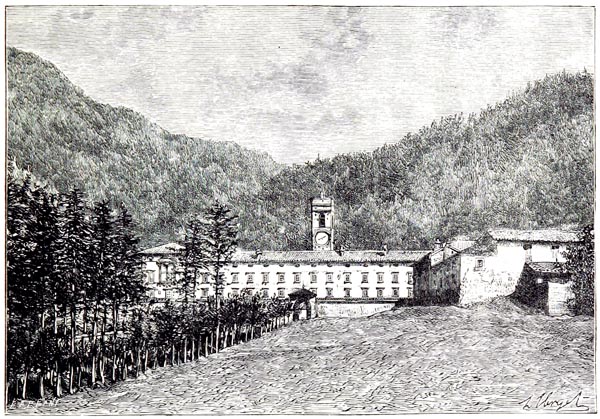

When, on leaving the ruins of Carthage, I travelled through Hesperia before the French invasion, I found the Spaniards still protected by their ancient way of life. The Escorial revealed to me, in a single site and a single set of buildings, Castilian severity: a barracks for coenobites, built by Philip II in the shape of a martyr’s grid, in remembrance of one of our disasters, the Escorial was built on rocky ground among gloomy barrens. It contained royal tombs, filled or to be filled; a library on which the spiders had set their seal; and masterpieces by Raphael mouldering away in an empty sacristy. Its eleven hundred and forty windows, three quarters of them broken, opened on silent reaches of earth and sky: the Court and the Hieronymites, gathered there formerly, expressed their epoch and their distaste for their epoch.

Near that redoubtable edifice, like an aspect of the Inquisition driven into the desert, was a park scattered with broom and a village whose smoke-stained buildings revealed the ancient passage of man. This Versailles of the barrens was only inhabited during intermittent royal visits. I saw a redwing, thrush of the heath, perched on the roof at dawn. Nothing could be more imposing than that sombre religious architecture, invincible in its faith, noble in its expression, taciturn in its history; an irresistible force drew my eyes to the sacred pilasters, stone hermits carrying religion on their heads.

Farewell, monasteries, which I have gazed at in the valleys of the Sierra Nevada, and on the coast of Murcia! There, to the tolling of a bell which soon will chime no more, under crumbling archways, among lauras without anchorites, voiceless tombs, the shade-less dead; in empty refectories, and abandoned courtyards where Bruno has left behind his silence, Francis his sandals, Dominic his torch, Charles his crown, Ignatius his sword, Rancé his hair-shirt; there, at the altar of a dying faith, one became accustomed to despising time and life: if one still dreamed of the passions there, your solitude lent them something which well suited the vanity of dreams.

Among these funereal buildings, one saw the shade of a man in black pass, that of Philip II, their creator.

Book XX: Chapter 8: Pius VII – The Union of the Roman States with France

BkXX:Chap8:Sec1

Bonaparte was subject to the transit of what the astrologers call an adverse planet: the same political pressures which troubled him in vassal Spain troubled him in submissive Italy. What had been the result of his squabbles with the clergy? Were the sovereign Pontiff, bishops, and priests, even the catechism, not overflowing with praise of his power? Did they not preach sufficient obedience? Were the weakened Roman States, diminished by half, an obstacle to him? Were things not subject to his will? Had not Rome itself been despoiled of its masterpieces and its treasures? Only its ruins remained to it.

Was it the moral and religious power of the Holy See that Napoleon feared? Yet, in persecuting the Papacy, did he not increase that power? Would not Saint Peter’s successor, submissive, as he was, have been more useful working in concert with his master, than being forced to defend himself against his oppressor? What drove Bonaparte then? The dark side of his genius, his inability to rest: an eternal gambler, when he could not stake an empire on a card, he staked a fantasy.

It is probable that at the root of these anxieties lay some desire for domination, some recollections from history entering athwart his ideas, inapplicable to his times. All authority (even that hallowed by time and faith) which was not attributed to himself seemed an insult to the Emperor. Russia and England fed his hunger for dominance, one because of its autocracy, the other because of its spiritual supremacy. He recalled the time when the Popes resided at Avignon, when France enclosed the source of religious dominance within its own boundaries: a salaried Pope on the Civil List would have delighted him. He could not see that in persecuting Pius VII, in rendering himself guilty of pointless ingratitude, he lost the benefit of appearing as the restorer of religion among the Catholic community: in his covetousness he acquired the last vestments of the priestly nonentity who had crowned him, and the honour of playing gaoler to an old and dying man. Yet in the end Napoleon required a department of the Tiber; it is said that he could not achieve total conquest except by taking the Eternal City: Rome is always the world’s greatest prize.

Pius VII had blessed Napoleon. On the point of returning to Rome, the Pope was told that he might be held in Paris: ‘All is foreseen,’ the Pontiff replied, ‘before leaving Italy I signed a formal notice of abdication; it is in the hands of Cardinal Pignatelli at Palermo, outside the range of French power. Instead of a Pope, all that will remain in your hands is a monk named Barnabé Chiaramonti.’

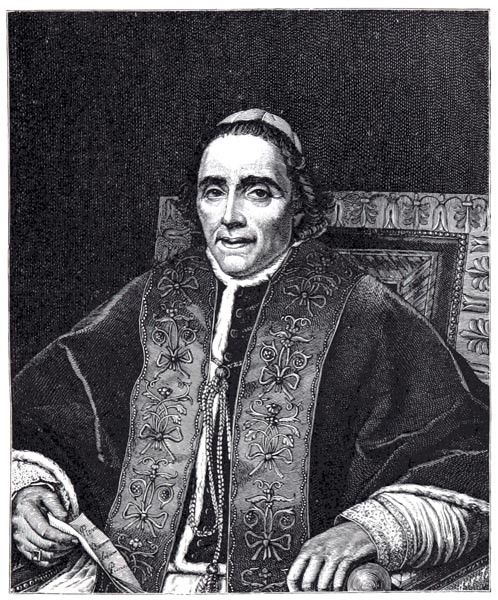

‘Le Pape Pie VII, Tableau de David, Musée du Louvre’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p403, 1888)

The British Library

The initial pretext for dispute given by the one seeking the dispute was the permission the Pope had accorded the English (with whom the sovereign Pontiff was at peace) to visit Rome like other foreigners. Now, Jérôme Bonaparte having married Miss Patterson in the United States, Napoleon disapproved of his alliance: Madame Jérôme Bonaparte, about to give birth, was not allowed to disembark in France and was obliged to land in England. Bonaparte wished the marriage annulled by Rome; Pius VII refused, finding no reason to nullify the contract, even though it had been made between a Catholic and a Protestant. Who defended the rules of justice, liberty and religion, the Pope or the Emperor? It was the latter who cried: ‘I have found a priest in this century more powerful than I; he rules minds, I only rule matter: the priests keep the soul and leave me the body.’ Remove Napoleon’s bad faith from the communications between those two men, one standing among the ruins of the new, the other seated among the ruins of the old, and an extraordinary depth of greatness remains.

A letter dated from Benavente in Spain, from the theatre of destruction, mixes the comic with the tragic: one might think oneself present at a performance of Shakespeare: the master of the world orders his Minister of Foreign Affairs to write to Rome and tell the Pope that he, Napoleon, would not accept the Candlemas candles, which the King of Spain, Joseph no longer desired; the Kings of Naples and Holland, Joachim and Louis, were equally required to refuse the aforesaid candles.

The French Consul had been ordered to tell Pius VII ‘that it was neither crimson robes nor power which give things their worth (the crimson robes and power of an aged captive!), that there might well be Popes and priests in hell, and that a candle blessed by a priest might be as holy a thing as that blessed by a Pope’: wretched indecencies of the philosophy of the clubs.

Then Bonaparte, having passed in a stride from Madrid to Vienna, taking up his role of exterminator once more, by a decree dated the 17th of May 1809, united the Papal States with the French Empire, declared Rome a free imperial city, and named a Consulte (Council) to take possession of it.

The Pope, having been dispossessed, still lived in the Quirinal; he still had command of several devoted members of the authorities, and the Swiss of his Papal Guard; it was excessive: Bonaparte needed a pretext for a final act of force; it was found in a ridiculous incident, which nevertheless displayed a naïve proof of affection: the fishermen of the Tiber had caught a sturgeon; they wanted to take it to their new Saint Peter in Chains; the agents of France immediately called this a riot, and whatever of the Papal government remained was dispersed. The sound of the cannon from Castel Sant’Angelo announces the fall of the Pontiff’s temporal sovereignty. The Papal flag is lowered and gives way to that tricolour which has announced glory and ruin in all parts of the world. Rome has seen plenty of other storms pass by and vanish: it is only necessary to lift the dust with which her ancient brow is covered.

Book XX: Chapter 9: The sovereign Pontiff’s protest – He is removed from Rome

BkXX:Chap9:Sec1

Cardinal Pacca, one of the successors to Consalvi, who had retired, hastens to the Holy Father. Both of them cry: ‘Consummatum est! (All is over!)’ The Cardinal’s nephew, Tiberio Pacca, brings him a copy of a decree of Napoleon’s; the Cardinal takes the decree, goes to a window whose closed shutters only allow a meagre light to enter, and tries to read the paper; he only does so with difficulty, with his unfortunate sovereign a few paces from him, while listening to the cannon fire of the imperial triumph. Two old men at night in a Roman palace struggling alone against a force which was crushing the world; they drew on the vigour of old age: near death one is invincible.

The Pope first signed a solemn protest; but before signing the Bull of excommunication prepared some time ago, he enquired of Cardinal Pacca: ‘What would you do?’ – ‘Lift your eyes to Heaven,’ replied his servant, ‘then give your orders: what issues from your mouth will be what Heaven wills.’ The Pope raised his eyes, signed and said: ‘Let the Bull go forth.’

Megacci posted the first copies of the Bull on the doors of three churches, Saint Peter’s, Santa Maria Maggiore, and San Giovanni in Laterano. The placards were torn down; General Miollis dispatched one to the Emperor.

If anything could have given excommunication a little of its ancient force, it was Pius VII’s virtue: among the ancients a lighting flash from a calm sky was considered the more threatening. But the Bull still displayed a weakness of character: Napoleon, included among the spoliators of the Church, was not expressly named. The times were fearful; the timid took refuge, with a secure conscience, in this absence of nominal excommunication. It was necessary to fight against thunder-bolts; it was necessary to hurl lightning for lightning, since defence was not an option; it was necessary to suspend religion, close the doors of the temples, forbid church-going, and order priests not to administer the sacraments. Whether the times were right or not for this great attempt, it was worth trying: Gregory VII had not failed to do so. If on the one hand there was insufficient faith to sustain an excommunication, on the other, there was not enough for Bonaparte, like Henry VIII, to make himself head of a separate Church. The Emperor, totally excommunicated, found himself in inextricable difficulties: force could close churches, but not open them; there was no way of forcing people to worship or priests to offer the holy sacrament. Never had anyone played as overwhelming a game with Napoleon.

A sixty-eight year old priest, without a single soldier, held the Empire in check. Murat dispatched seven hundred Neopolitans to Miollis, the inaugurator of the feast of Virgil at Mantua. Radet, General of the Gendarmerie who was in Rome, was charged with seizing the Pope and Cardinal Pacca. Military precautions were employed, and orders were given in the greatest of secrecy exactly as on Saint Bartholomew’s Night: when an hour after midnight struck on the Quirinal clock, the troops that had assembled in silence began intrepidly to climb the stairs of the two decrepit priests’ gaol.

At the agreed moment, General Radet penetrated the courtyard of the Quirinal via the main entrance; Colonel Siry, who had slipped into the palace, opened the doors for him from within. The General ascended to the apartments: having arrived in the Hall of Sanctification, he found the Swiss Guard there, forty strong; they made no resistance, having received orders to abstain from doing so: the Pope wished only God to defend him.

The palace windows giving onto the street running to the Porta Pia had been shattered by axe-blows. The Pope having risen in haste, dressed in rochet and mozetta, occupied the Hall of Common Audience with Cardinal Pacca, Cardinal Despuig, several prelates and members of the secretariat. He was sitting before a table between the two Cardinals; Radet enters; both parties remain silent. Radet, pale and disconcerted, finally speaks: he tells Pius VII that he must renounce temporal sovereignty over Rome, and that if his Holiness refuses to obey, he has orders to conduct him to General Miollis.

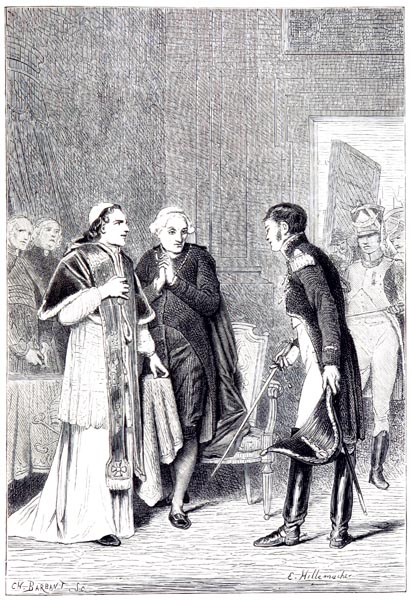

‘J'ai une Mission Douloureuse à Accomplir’

L'Histoire de France Depuis 1789 Jusqu'en 1848, Racontée à mes Petits-Enfants, par M. Guizot. Leçons Recueillies par Madame de Witt, Vol 02 - François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (p131, 1878)

The British Library

The Pope replied that if the vows of loyalty obliged Radet to obey Bonaparte’s injunctions, all the more reason why he, Pius VII, must keep the vows which he made when receiving the tiara; he could neither yield nor abandon the domain of the Church which did not belong to him, and of which he was merely the administrator.

The Pope having asked if he must go alone: ‘Your Holiness,’ the general replied, ‘may take your minister with you.’ Pacca hastened to don his Cardinal’s robes in a neighbouring chamber.

On Christmas Eve, Gregory VII, while celebrating Holy Communion at Santa Maria Maggiore, was dragged from the altar, beaten about the head, despoiled of his ornaments and led to one of the towers by order of the Prefect Cencius. The people took up arms; a fearful Censius fell at his captive’s feet; Gregory, having calmed the people, was led back to Santa Maria Maggiore and completed the Communion.

Nogaret and Colonna, entering at night (on the 8th of September 1303) in Agnani, attacked Boniface VIII’s residence, he waiting for them with his Pontiff’s mantle over his shoulders, his head crowned with the tiara, armed with the keys and cross. Colonna struck him in the face: Boniface dying later of anger and grief.

Pius VII, humble and dignified, showed neither the same human courage nor the same worldly pride; his exemplar was closer to him in time; his trials resembled those of Pius VI. Two Popes of the same name, one the successor of the other, were victims of our revolutions. Both dragged through France on the Via Dolorosa; one, at the age of eighty-two, brought to die at Valence, the other, a septuagenarian, enduring imprisonment at Fontainebleau. Pius VII seemed the ghost of Pius VI, travelling the same road.

When Pacca returned in his Cardinal’s robe, he found his august master already in the hands of the gendarmes and their henchmen who forced him to descend the stairs through the debris of the overthrown doors. Pius VI, taken from the Vatican on the 20th of February 1798, three hours before sunrise, forsook the world of masterpieces which seemed to mourn him and left Rome, through the Porta Angelica. Pius VII, taken from the Quirinal on the 6th of July at daybreak, left by the Porta Pia; he made a tour of the walls as far as the Porta del Popolo. This Porta Pia, where I have so often walked alone, was that by which Alaric entered Rome. Following the circuit, along which Pius VII passed, I only saw in the Villa Borghese Raphael’s retreat and in Monte Pincio the refuge of Claude Lorrain, and Poussin; marvellous memories of female beauty and the light of Rome; memories of artistic genius sponsored by Papal power, which might pursue and console a captive and despoiled prince.

BkXX:Chap9:Sec2

When Pius VII left Rome, he had in his pocket a papetto worth twenty two sous: like a soldier at five sous per halt, he has regained the Vatican. Bonaparte, at the moment of General Radet’s exploit, had his hands full of kingdoms: what else remained? Radet has written an account of his exploit; he had a picture painted which he has left to his family: so are notions of justice and honour confused in some minds.

In the courtyard of the Quirinal, the Pope met his Neapolitan oppressors; he blessed them and the city: that apostolic benediction infusing everything, misfortune as well as prosperity, gives a particular character to the events of the lives of these royal Pontiffs who in no way resemble other kings.

The post horses were waiting outside the Porta del Populo. The blinds of the coach into which Pius VII climbed were drawn on the side where he sat; the Pope entered, the doors were doubly locked, and Radet put the keys in his pocket; the Chief of Gendarmes had to accompany the Pope as far as the Charterhouse at Florence.

At Monterossi weeping women stood on their doorsteps: the General begged his Holiness to lower the blinds in order to conceal himself. The heat was oppressive. Towards evening Pius VII requested a drink; the sergeant Cardigny filled a bottle from a natural spring flowing by the road; Pius VII drank with great pleasure. On the hill of Radicofani, the Pope stopped at a humble inn; his vestments were drenched with sweat, and he had nothing to change into; Pacca helped the servant make up his Holiness’ bed. On the next day the Pope came across some peasants, and said to them: ‘Courage and prayer!’ They passed through Siena; they entered Florence, and one of the carriage wheels shattered; the people, moved, cried: ‘Santo padre! Santo padre!’ The Pope was pulled through the overturned carriage’s door. Some prostrated themselves; others touched His Holiness’ vestments, as the people of Jerusalem did the robe of Christ.

The Pope was at last able to start for the Charterhouse; he was the heir of the bed which Pius VI had occupied ten years earlier, in that solitude, where two grooms hoisted him into the carriage as he groaned with pain. The Charterhouse belonged to the Vallombrosa site; through a series of pine woods you reached Camaldoli, and from there, from cliff to cliff, the summit of the Apennines from which two seas can be seen. An abrupt command forced Pius VII to leave again for Alessandria; he had time only to ask the prior for a breviary; Pacca was separated from his royal Pontiff.

‘Vallombrosa’

Italian Pictures, Drawn with Pen and Pencil - Samuel Manning (p195, 1885)

The British Library

From the Charterhouse to Alessandria the populace crowded in from every side; they threw flowers to the prisoner, they gave him water, they presented him with fruit; the countrymen wanted to free him, calling out: ‘Vuole? Dica! Do you wish it? Say!’ An old thief stole a pin from him, a relic which would open the gates of heaven for the culprit.

Three miles from Genoa, a litter bore the Pope to the seashore; a felucca carried him from the far side of the town to San Pier d’Arena. By way of Alessandria and Mondovi Pius VII reached the first French village; he was welcomed there with effusions of religious tenderness; he said: ‘How could God allow us to be insensible to these marks of affection?’

The Spaniards taken prisoner at Zaragoza were being held at Grenoble: like those European garrisons forgotten amongst the hills of India, they sang at night and made the alien atmosphere echo with the airs of their homeland. Suddenly the Pope descends on them; he seemed to have responded to those Christian voices. The prisoners fly to meet this new captive; they fall to their knees; Pius VII almost pushes his whole body through the door; he extends his thin and trembling hands over these warriors who have defended Spanish liberty with the sword, as they have defended Italian liberty with their loyalty; the twin swords cross over those heroic heads.

BkXX:Chap9:Sec3

From Grenoble Pius VII reached Valence. There, Pius VI had died; there, he exclaimed when shown to the people: ‘Ecce homo!’ There, Pius VI parted company from Pius VII; the dead man encountering his grave, entered it; he brings the twin apparition to an end, for until then the two Popes could be seen travelling together, like the shadow accompanying the body. Pius VII wore the ring that Pius VI had on his finger when he died: the emblem of his having accepted the wretchedness and fate of his precursor.

Two leagues from Comana, Saint John Chrysostom rested at the chapel of Saint Basiliscus; that martyr appeared to him during the night and said to him: ‘Courage: brother John! Tomorrow we will be together.’ John replied: ‘Glory be to God for all things!’ He lay down on the ground and died.

At Valence, Bonaparte had begun the career with which he hurtled towards Rome. Pius VII was not allowed the time to visit the remains of Pius VI; he was urged precipitately towards Avignon: in order to bring him to that little Rome where he could view the ice cellar beneath the palace of another line of Pontiffs, and hear the voice of the laurel-crowned poet of former times who had summoned the successors of Saint Peter back to the Capitol.

Driven on recklessly, he entered Savoy Maritime; at the Pont du Var, he wished to cross on foot; he met the population ranked in order of merit, the ecclesiastics dressed in their sacerdotal vestments, and ten thousand people kneeling in profound silence. The Queen of Etruria with her two children, also kneeling, waited for Saint Peter at the end of the bridge. At Nice, the streets of the town were strewn with flowers. The captain, who was taking the Pope to Savona, took an unfrequented road through the woods that night; to his great astonishment he found himself in the midst of a flood of solitary light; a lantern had been hung from every tree. Along the seafront, the Corniche was similarly illuminated; the ships saw these signals from afar lit, for the shipwreck of a captive priest, out of respect, tenderness and piety. Was this the way Napoleon returned from Moscow? Was he preceded by reports of his good deeds and his blessing of the people?

During this long journey, the Battle of Wagram had been won, while Napoleon’s marriage with Marie-Louise was delayed. Thirty Cardinals summoned to Paris were exiled, and the Roman Consulte created by France had to announce anew the union of the Holy See and the Empire.

The Pope, while detained at Savona, weary and besieged by Napoleon’s creatures, issued a brief, whose principal author was Cardinal Roverella, which allowed confirmatory Bulls to be sent to the various bishops named. The Emperor had not expected such compliance; he rejected the brief because it would have obliged him to set the royal Pontiff at liberty. In an access of rage he ordered the Cardinals who opposed him to quit their crimson robes; some were imprisoned at Vincennes.

The Prefect of Nice wrote to Pius VII that: ‘he was forbidden to communicate with any church in the Empire, under sentence of disobedience; that he, Pius VII, had ceased to be the organ of the Church because he was preaching rebellion and his spirit was full of venom; and that, since nothing could make him see sense, he would find His Majesty quite powerful enough to depose a Pope.’

Was it actually the victor of Marengo who dictated the minute of this same letter?

At last, after three years in captivity at Savona, on the 9th of June 1812, the Pope was summoned to France. He was requested to change his clothes: conducted to Turin, he arrived at the hospice of Mont Cenis in the middle of the night. There, close to death, he received extreme unction. He was only permitted to halt for the time necessary to administer the last sacraments; he was not allowed to remain close to Heaven. He did not complain; he gave a fresh example of the meekness of the martyr of Vercelli. At the foot of the mountain, at the moment when she was about to be beheaded, seeing the clasp of the executioner’s chlamys fall, she said to the man: ‘See, a gold clasp has just fallen from your shoulder; pick it up, for fear of losing what you have only won with much effort.’

During his journey through France, Pius VII was not allowed to descend from his carriage. When he ate some food it was in that same carriage, which was locked when starting the next stage. On the 20th of June in the morning he arrived at Fontainebleau; three days later Napoleon crossed the Niemen to begin his expiation. The doorman refused to receive the prisoner, because no such order had yet reached him. The order having been sent to Paris, the Pope enters the chateau; heavenly justice thereby entering with him: on the same table where Pius VII rested his failing hand, Napoleon signed his abdication.

‘L'Empereur va au-Devant du Pape à Fontainebleau, (1804), (Dessiné par Mounet)’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p401, 1888)

The British Library

If the iniquitous invasion of Spain roused the world of politics against Bonaparte, the unrewarding occupation of Rome set him against the world of morality: without the least benefit, he alienated as if for pleasure nations and altars, man and God. Between these two precipices he had created at the borders of his life, he travelled, by a straight path, to seek his destruction at the boundary of Europe, as if over the bridge that Death, aided by disease, threw across the chaos.

Pius VII is no stranger to these Memoirs: he was the first sovereign to whom, during my political career, begun and suddenly interrupted during the Empire, I carried out an embassy. I see him still, receiving me at the Vatican, Le Génie du Christianisme open on his desk, in the same office to which I have been admitted to kneel at the feet of Leo XII and Pius VIII. I like to recall what he underwent; my remembrance of his sufferings will repay my debt of gratitude to him, for his blessing of those other sufferings at Rome in 1803.

Book XX: Chapter 10: The Fifth Coalition – The Capture of Venice – The Battle of Essling – The Battle of Wagram – Peace signed in the Emperor of Austria’s palace – Divorce – Napoleon marries Marie-Louise – The birth of the King of Rome

BkXX:Chap10:Sec1

On the 9th of April 1809, the Fifth Coalition between England, Austria and Spain, was declared, silently relying on the discontent of other nations. The Austrians, complaining of the violation of previous treaties, all at once crossed the River Inn at Braunau: they have been reproached for their tardiness, they wanted to do a Napoleon; but speed was not their style. Happy to have left Spain, Bonaparte hastened to Bavaria; he set himself at the head of the Bavarians without waiting for the French: any soldiers would do for him. At Abensberg, he defeated Archduke Louis, at Eckmühl Archduke Charles: he cuts the Austrian Army in two, and achieves the passage of the Salza.

‘Napoléon Harangue les Troupes Bavaroises et Wurtembergeoises à Abensberg (20 avril 1809), Peint par Debret.’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p613, 1888)

The British Library

He enters Vienna. On the 21st and 22nd of May the dreadful affair of Aspern-Essling takes place. The account of Archduke Charles reports that, on the first day, two hundred and eighty eight Austrian cannon fired fifty-one thousand rounds, and that, on the next day, more than four hundred cannon took part on both sides. Marshal Lannes was mortally wounded. Bonaparte spoke to him and then forgot him: human relationships cool as quickly as the cannonball that strikes them.

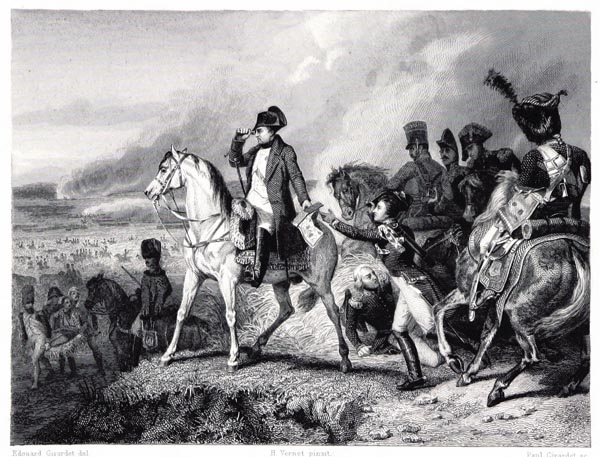

The Battle of Wagram (5th-6th of July 1809) continues the run of battles executed in Germany: Bonaparte deploys all his genius there. General César de Laville, ordered to prevent disaster striking the left flank, finds him on the right flank directing Marshal Davout’s attack. Napoleon immediately returns to the left flank and repairs the damage incurred by Masséna. It was then, at the moment when the battle was thought lost, that, alone judging to the contrary from the enemy manoeuvres, he shouted: ‘The battle is won!’ He sets his mind against a half-hearted victory; he brings things back to the boil as Caesar dragged his astonished veterans back to the fight by the throat. Nine hundred mouths of bronze roar; the plain and the cornfields are in flames; whole villages vanish; the action lasts twelve hours. In one charge alone, Lauriston trots towards the enemy at the head of a hundred cannon. Four days afterwards they gathered up, amongst the wheat, soldiers who had died in the sunlight beneath the trampled crop, lying there, sticky with blood: maggots had already infested the wounds of the riper corpses.

‘Bataille de Wagram, Tableau d'Horace Vernet, Musée de Versailles.’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p627, 1888)

The British Library

In my youth, people read commentaries by Folard and Guischardt, Tempelhof and Lloyd, on Frederick II’s campaigns; they studied ordre profond and ordre mince; on my second-lieutenant’s desk I manoeuvred plenty of little squares, of wood. Military science changed like everything else as a result of the Revolution; Bonaparte invented war on a grand scale, the victories of the Republic having furnished him with the idea through their mass requisitions. He despised fortresses, which he was content to ignore; adventured into countries he had invaded, and won everything by dint of battle. He was never concerned with retreat; he travelled straight ahead like those Roman roads that cross mountains and precipices without a detour. He moved all his forces to one point, and then gathered in an arc the isolated corps whose lines he had scattered. This manoeuvre which suited him was in accord with French aggression; but it produced scant success with less impetuous and agile troops. Towards the end of his career he also ordered artillery charges and took redoubts with cavalry. What was the result? In leading France into war, Europe was taught how to march: it was no more than a question of increasing the means; masses counter-balanced masses. Instead of a hundred thousand men, six hundred thousand were employed; instead of a hundred cannon, five hundred were used: there is no increase in skill; it is merely on a larger scale. Turenne knew as much as Bonaparte, but he was not absolute master and had not forty million men at his disposal. Sooner or later we must return to the civilised warfare Moreau still knew, warfare which leaves nations intact while a small number of soldiers carry out their duty; we must revisit the art of retreat, the defence of a country by means of fortresses, and patient manoeuvres which cost time but spare men. Napoleon’s gigantic battles are beyond the bounds of glory; the eye cannot embrace those fields of carnage which, eventually, fail to produce a result proportional to their calamities. Europe, barring unforeseen events, will be weary of war for many a long year. Napoleon has killed war by exaggerating it: our Algerian war is merely an experimental training ground created for our soldiers.

Among the dead, on the field of Wagram, Napoleon showed the impassibility that both belonged to him and that he affected when he appeared before others; he spoke coldly or more often he repeated his habitual phrase in such circumstances: ‘This is a mighty consummation!’

When wounded officers were mentioned to him, he replied: ‘They are not present.’ If military virtue teaches various virtues, it weakens others: too humane a soldier cannot accomplish his task; the sight of blood and tears, the suffering, the cries of pain, delaying him at every step, would destroy within him what created the Caesars; a race, after all, that one would happily do without.

After the battle of Wagram an armistice was agreed at Znaïm. The Austrians, according to our bulletins, retired in good order and left not one mounted cannon behind them. Bonaparte, in possession of Schonbrünn, worked there on the peace. ‘On the 13th of October,’ says the Duke of Cadore, ‘I came to Vienna to work with the Emperor. After a few moments discussion, he said to me: “I am going to the review; stay in my office; you can draw up that note and I’ll read it after the review.” I stayed in his office with Monsieur de Menéval his private secretary; he soon returned. – “Has the Prince of Lichtenstein made known to you,” Napoleon said to me, “that it has often been suggested to him that I should be assassinated?” – “Yes, Sire; he expressed the horror with which he rejected such proposals.” – “Well, Someone is here to try! Follow me.” I went into the salon with him. There were several people looking very agitated, surrounding a young man from eighteen to twenty years old, of a fine, quite mild appearance, proclaiming a kind of candour, who alone seemed to be perfectly calm. It was the assassin. He was interrogated with extreme gentleness by Napoleon himself, General Rapp serving as interpreter. I will only record those of his replies which struck me favourably.

“Why do you wish to assassinate me?” – “Because there can be no peace for Germany while you are alive.” – “What inspired you to attempt this?” – “Love of my country.” – “Have you discussed it with anyone else?” – “I was conscience-bound.” – Do you realise the danger to which you exposed yourself?” – “I realise it; but I would be happy to die for my country.” – “You own to religious principles; do you think that God authorises assassination?” – “I hope that God will forgive me on account of my motive.” – “Do they teach that doctrine in the schools you have attended?” – “A large number of those who attended them with me are animated by these sentiments and disposed to devote their life to their country’s good.” – “What will you do if I set you at liberty?” – “I will kill you.”

The shocking naivety of these replies, the cold and unshakeable intent they indicated, and that fanaticism, so resolute in the face of human fear, made an impression on Napoleon that I regarded as the more profound the more cold-blooded it appeared. He made everyone retire, and I alone stayed with him. After a few comments on a fanaticism so blind and so intellectual, he said to me: “It is essential to make peace.”’ This account by the Duc de Cadore deserves to be quoted in its entirety.

The nations commenced to levy troops; to Bonaparte they heralded enemies more powerful than kings; the resolution of one man among a people saved Austria then. However Napoleon’s fate had not yet averted its gaze. On the 14th of August 1809, in the Austrian Emperor’s own palace, he made peace; on that occasion a daughter of the Caesars was the palm offered; but Josephine was crowned, and Marie-Louise was not: with his first wife’s departure, the virtue of the divine unction seemed to leave the conqueror. I might have seen in Notre-Dame de Paris the same ceremony which I saw in the cathedral at Rheims; with the exception of Napoleon the same people were present.