François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXVIII: Political Power: 1823-1828

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 1: The deliverance of the King of Spain – My dismissal

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 2: The Opposition follows me

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 3: My final diplomatic letters

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 4: Neuchâtel in Switzerland

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 5: The death of Louis XVIII – The coronation of Charles X

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 6: Reception of the Knights of the Orders

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 7: I gather my former adversaries around me – My public changes

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 8: An extract from my polemic after my fall

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 9: I refuse the pension the Minister of State wishes to pay me – The Greek Committee – Monsieur Molé’s note – A letter from Canaris to his son – Madame Récamier sends me an extract from another letter – My complete works

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 10: A trip to Lausanne

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 11: Return to Paris – The Jesuits – A Letter from Monsieur de Montlosier and my reply

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 12: More of my polemics

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 13: A letter from General Sébastiani

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 14: The death of General Foy – The Law of Love and Justice – A letter from Monsieur Étienne – A letter from Benjamin Constant – I reach the summit of my political importance – An article regarding the King’s name-day – Withdrawal of the law on the policing of the press – Paris illuminated – Monsieur Michaud’s note.

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 15: Monsieur Villèle’s annoyance – Charles X decides to review the National Guard on the Champ-de-Mars – I write to him: my letter

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 16: The Review – The disbanding of the National Guard – The Elected Chamber is dissolved - The new Chamber – The Refusal to Contest - The fall of Villele’s ministry – I contribute to the formation of the new ministry and I accept the Rome embassy

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 17: An examination of the reproach against me

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 18: Madame de Staël – Her first trip to Germany – Madame Récamier in Paris

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 19: Madame de Staël’s return –– Madame Récamier at Coppet – Prince Augustus of Prussia

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 20: Madame de Staël’s second trip –– Madame de Staël’s letter to Bonaparte – The Château de Chaumont

- Book XXVIII: Chapter 21: Madame Récamier and Monsieur de Montmorency are exiled –– Madame Récamier at Chalons

Book XXVIII: Chapter 1: The deliverance of the King of Spain – My dismissal

Revised: December 1846.

BkXXVIII:Chap1:Sec1

Here in its place in time comes Le Congrès de Vérone which I published in two volumes. If anyone should wish to read it again, they will find it everywhere. My Spanish War, the great political event of my life, was an immense undertaking. For the first time, the Legitimacy was going to burn powder under the white banner, to fire its first cannon after that cannon-fire of the Empire that will echo to all posterity. To bestride Spain with a single step, to succeed on the same soil where the man of history’s armies had formerly met defeat, to do in six months what he failed to do in seven years, who could have aspired to so prodigious an outcome? Yet that is what I achieved; though how many curses fell on my head at the gaming-table where the Restoration had seated me! I had before me a France hostile to the Bourbons and two great Foreign Ministers, Prince von Metternich and Mr Canning. Not a day passed without my receiving letters prophesying disaster since the war with Spain was not at all popular in France, or in Europe. Indeed, after my success in the Peninsula, my downfall was not long in coming.

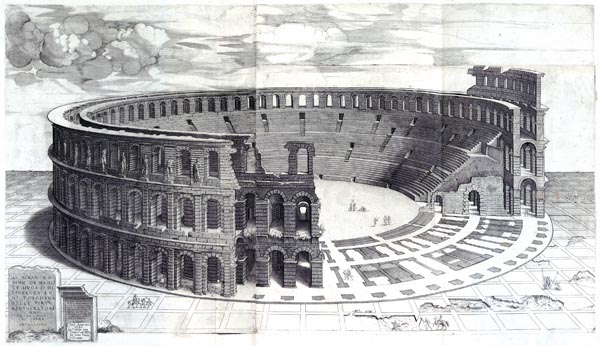

‘The Arena at Verona’

Enea Vico, Clemens Agatius, c. 1543 - c. 1567

The Rijksmuseum

In our joy over the telegraph message which announced the King of Spain’s release, we Ministers hastened to the palace. There I had a presentiment of my fall: I met with a bucket of cold-water over my head which restored me to my usual humility. The King and Monsieur did not notice us. Madame la Duchesse d’Angoulême, overjoyed by her husband’s triumph, had eyes for nobody. That immortal victim wrote a letter of Ferdinand’s deliverance ending with this exclamation, a sublime one issuing from the mouth of Louis XVI’s daughter: ‘So here is the proof that one can save an unfortunate king!’

‘Marie Thérèse-Charlotte, Fille de Louis XVI’

Procès des Bourbons, Contenant des Détails Historiques sur la Journée du 10 aôut 1792 - Pierre Turbat (p260, 1798)

Internet Archive Book Images

On the Sunday, I returned before the meeting of the council to pay my court to the Royal Family; the august Princess gave each of my colleagues a pleasant word: to me she addressed no comment. I did not merit, it is true, such an honour. Silence from the Orphan of the Temple, can never be deemed ingratitude: Heaven has a right to the earth’s worship and owes nothing to anyone.

I hung on, after that, till Whitsuntide; yet my friends were not without their anxieties; they often said to me: ‘You will be fired tomorrow. – Straight away if you like,’ I would reply. On Whit Sunday, the 6th of June 1824, I made my way to Monsieur’s outer rooms: an usher came to tell me that I was required. It was Hyacinthe, my secretary. He told me on seeing me that I was no longer the Minister. I opened the envelope he presented to me; there I found this note from Monsieur de Villèle:

‘Monsieur le Vicomte,

I am obeying the King’s command in at once communicating to Your Excellency an order His Majesty has just issued.

“The Sieur Comte de Villèle, President of our Council of Ministers, is entrusted for the interim with the Foreign Affairs portfolio, replacing the Sieur Vicomte de Chateaubriand.”’

This order was in Monsieur de Rainneville’s handwriting, he who is so good as to be embarrassed by it still, when he meets me. Ah! Goodness me! Do I know Monsieur de Rainneville? Have I ever given him a thought? I encounter him often enough. Has he ever perceived my knowledge of his handwriting on the ordinance which erased me from the list of Ministers?

And yet, what had I done? Where were my supposed intrigues and ambitions? Did I go for secret solitary walks in the depths of the Bois de Boulogne because I desired Monsieur de Villèle’s place? It was that strange life of mine that ruined me. I was foolish enough to remain as Heaven has made me, and, since I wished for nothing, they thought I desired everything. Today I am well aware that my isolated life was a great mistake. ‘What! You don’t wish to be anything! Off with you, then! We don’t like it when a man despises what we adore, and thinks himself entitled to scorn the mediocrity of our lives.’

The problems of wealth and the inconveniences of poverty followed me to my lodgings in the Rue de l’Université: on the day of my dismissal, I had an immense dinner booked at the Ministry; I had to send my apologies to the guests, and squeeze three vast courses for forty persons into my little kitchen for two. Montmirel and his staff set to work, and cramming dripping-pans, saucepans, and bowls into every corner, he found shelter for his re-heated masterpiece. An old friend came to share my first meal as a marooned sailor. Town and Court hastened to me, since there was an outcry at the brutality of my dismissal, after the service I had just rendered; they were convinced my disgrace would be of short duration; they adopted liberal airs in consoling me for my few days bad luck, at the end of which they would be able to provide a fruitful reminder to the unfortunate man on his return to power that they had not abandoned him.

They were wrong; their courage was wasted on me: they had counted on my being commonplace, on my snivelling, on my possessing the ambition of a lap-dog, on my willingness to confess myself at fault, to go stalking after those who had chased me away: that was to comprehend me badly. I departed, without even claiming the salary that was due to me, without accepting a single favour or a single farthing from the Court; I shut my door on those who had betrayed me; I spurned the crowd’s condolences and took up weapons. Then they all dispersed; universal condemnation erupted, and my stance, which had appeared admirable at first to the salons and ante-chambers, seemed appalling.

After my dismissal, would it not have been better to keep silent? Had not the brutality of the proceedings rallied the public to me? Monsieur de Villèle has repeatedly said that the letter of dismissal was delayed; because of this accident, it had unfortunately been handed to me at the Palace; perhaps it was so; but when one plays a game, one should take account of chance; above all one should not write, to a friend that one values, a letter of the sort one would be ashamed to address to a guilty valet, whom one would kick out onto the pavement, without ceremony or remorse. The Villèle party’s irritation with me was all the greater in that they wanted to appropriate my success, and because I had displayed a grasp of matters about which I was supposed to know nothing.

No doubt (as they said at the time) with silence and moderation I would have won praise from that species that lives in perpetual adoration of the portfolio; by doing penance for my innocence, I would have prepared my way for re-joining the Council. It would have been better in a commonplace way; but that was to take me for what I am not; it assumed a desire to grasp the helm of State once more, a wish to make my way; a desire and a wish that would not have occurred to me in a thousand years.

The idea I had of representative government led to my joining the opposition; systematic opposition seems to me the only kind suitable for that kind of government; the opposition called that of conscience is powerless. Conscience can judge a moral issue, but not an intellectual one. There is no choice but to place oneself under a leader, one who can distinguish between good and bad law. If not, then a representative may mistake his own stupidity for conscience, and vote accordingly. The opposition called that of conscience consists in drifting between parties, gnawing at the leash, even voting, according to circumstance, for the government, being magnanimous in one’s rage; an opposition of mischievous mutiny among soldiers, of calculated ambition among leaders. To the extent that England has remained healthy, it never had other than a systematic opposition: one entered and left it with one’s friends; on relinquishing the portfolio one went to sit on the opposition benches. Since one was assumed to have been removed for not wishing to accept a system, that system, remaining vested in the crown, had of necessity to be opposed. Now, the men merely representing principles, systematic opposition only sought to change the principles, while handing over the attack on them to men.

Book XXVIII: Chapter 2: The Opposition follows me

BkXXVIII:Chap2:Sec1

My downfall made a great noise: those who appeared most satisfied criticized the manner of it. I have since learnt that Monsieur de Villèle hesitated; Monsieur de Corbière decided the matter: ‘If he returns through one door of the Council chamber’, he is supposed to have said, ‘I leave through the other.’ They allowed me to depart: it was obvious that they would prefer Monsieur de Corbière to me. I did not like him: I troubled him, he drove me out: he did right.

The day after my dismissal and the following days, the Journal des Débats carried these words which do Monsieur Bertin so much honour:

‘For a second time Monsieur de Chateaubriand has undergone the ordeal of formal dismissal.

He was dismissed in 1816, as Minister of State, for attacking, in his immortal work Monarchy according to the Charter, the famous decree of the 5th of September, which proclaimed the dissolution of the ‘Unparalleled Chamber’ of 1815. Messieurs de Villèle and Corbière were simply Deputies then, leaders of the Royalist opposition, and it was for taking on the mantle of their defence that Monsieur de Chateaubriand became a victim of Ministerial wrath.

In 1824, Monsieur de Chateaubriand is again dismissed, and it is by Messieurs de Villèle and Corbière, now Ministers, that he is sacrificed. A remarkable thing! In 1816, he was punished for speaking out; in 1824, they punish him for saying nothing; his crime is to have kept silent during the debate regarding the interest rate on Government bonds. Disgrace is not always a disaster; public opinion, the ultimate judge, will tell us in which class Monsieur de Chateaubriand’s must be placed; it will also tell us to whom today’s order will be most fatal, the vanquisher or the vanquished.

Who said, at the start of the session, that in this manner we would spoil the whole outcome of the Spanish enterprise? What is needed this year is simply the law regarding the seven-year term (but the whole law), and the budget. The business of Spain, the Orient and the Americas, conducted as it was being, prudently and silently, would have been resolved; the brightest of futures would have been before us; they wanted to gather unripe fruit; it has not fallen, and they thought to remedy haste by violence.

Anger and envy are bad counsellors; States are not governed by passion, or in fits and starts.

P. S. The law regarding the seven-year term was passed, this evening, in the Chamber of Deputies. One might say that Monsieur de Chateaubriand’s doctrines have triumphed after that Minister’s departure. This law, which he conceived some time ago, as an addition to our institutions, will forever, along with the War in Spain, mark his term in office. It is wholly regrettable that Monsieur de Corbière, on Saturday, prevented one who was then still his illustrious colleague from speaking. The Chamber of Peers would at least have heard his swansong.

As for ourselves, it is with the greatest regret that we return to our path of struggle, from which we had hoped to be freed forever by the unification of the Royalists; but honour, political loyalty, the well-being of France, do not allow us to falter in the course which we must take.’

The signal for action was thus given. Monsieur de Villèle was not too alarmed at first; he failed to realise the weight of opinion. It took several years to defeat him, but he fell at last.

Book XXVIII: Chapter 3: My final diplomatic letters

BkXXVIII:Chap3:Sec1

I received a letter from the President of the Council, in final settlement, which proved that, in my great simplicity, I had failed to appropriate anything of that which renders a man respectable and respected:

‘Paris, 16th June 1824.

Monsieur le Vicomte,

I hastened to submit to His Majesty the order by means of which he might consider you wholly and completely discharged of the sums you received from the Royal treasury, for private expenses, during the period of your Ministry.

The King has approved all the terms of this order, the original of which I have the honour of enclosing.

Accept, Monsieur le Vicomte, etc.’

My friends and I soon despatched a volley of correspondence:

Monsieur de Chateaubriand to Monsieur de Talaru

‘Paris, the 9th of June 1824.

I am no longer a Minister, my dear friend; they say you will be. When I obtained the Madrid embassy for you, I said to several people, who still remember: ‘I have just named my successor.’ I wish to have been a prophet. Monsieur de Villèle holds the portfolio ad interim.

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

Monsieur de Chateaubriand to Monsieur de Rayneval

‘Paris, the 16th of June 1824.

I am finished, dear Sir; I hope you will still be in place for some time. I have made sure you shall have no grounds to complain of me.

It is possible that I will retire to Neuchâtel, in Switzerland; if that happens, please ask His Prussian Majesty in advance for his protection and goodwill; offer my respects to Count von Bernstorff, my friendship to Monsieur Ancillon, and my compliments to all your secretaries. I beg you, dear Sir, to believe in my devotion and my sincere attachment to you.

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

Monsieur de Chateaubriand to Monsieur de Caraman

‘Paris, the 22nd of June 1824.

Monsieur le Marquis, I have received your letters of the 11th of this month. Someone other than me will advise you of the course you must follow from now on; if it conforms to what you have already heard, it will take you far. It is probable that my dismissal will give great pleasure to Monsieur von Metternich, for a fortnight.

Monsieur le Marquis, accept my farewells and fresh assurance of my devotion and my highest consideration.

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

Monsieur de Chateaubriand to Monsieur de Neuville

‘Paris, the 22nd of June 1824.

No doubt you have learned of my dismissal. It only remains for me to say how happy I have been with the relations between us, which are not severed. Continue, dear friend, to render service to your country, but do not count too much on recognition for doing so, and don’t expect your successes to provide a reason for keeping you in place or for showing you any honour.

I wish you dear Sir, all the happiness you deserve, and I embrace you.

CHATEAUBRIAND.

P. S. I have just received your letter of the 5th of this month, in which you inform me of the arrival of Monsieur de Mérona. Thank you for your firm friendship; be certain I have found nothing but that in your letters.’

Monsieur de Chateaubriand to Monsieur de le Compte de Serre

‘Paris, the 23rd of June 1824.

My dismissal will have proven to you, Monsieur le Comte, my inability to serve you; it only remains for me to express my wish to see you in the situation to which your talents summon you. I am retiring, happy to have contributed to returning France her military and political freedom, and to have introduced the seven-year term into the electoral system; that is not all I would have done; the change in qualifying age is a necessary consequence of it; but the principle is finally established; time will do the rest, if it does not undo it. I dare to flatter myself in believing, Monsieur le Comte, that you have had nothing to complain of in our relationship; and I congratulate myself always on having met a man of your worth in government.

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

Monsieur de Chateaubriand to Monsieur de la Feronnays

‘Paris, the 16th of June 1824.

If by any chance you are still in St Petersburg, Monsieur le Comte, I would not wish to end our correspondence without expressing all the esteem and friendship you have aroused in me: be well; be happier than me, and believe that you may see me again through all life’s circumstances. I am writing a note to the Emperor.

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

The reply to this parting note arrived in early August. Monsieur de La Ferronays had agreed to function as Ambassador during my Ministry; later I became in turn an Ambassador during Monsieur de La Ferronnay’s Ministry: neither thought the other had been risen or fallen. Compatriots and friends, we rendered each other mutual justice. Monsieur de La Ferronays had endured the harshest trials without complaint; he remained loyal despite his sufferings and his noble poverty. After my fall, he acted on my behalf in St Petersburg as I would have acted on his: an honest man is always sure of being understood by an honest man. I am happy to produce this moving testimonial of Monsieur de La Feronnays’ courage, loyalty and nobility of soul. At the moment when I received this letter, it was a compensation for me, far beyond the capricious and banal favours of fortune. Here alone, and for the first time, I feel I ought to violate the honourable privacy that friendship urges.

Monsieur de la Ferronays to Monsieur de Chateaubriand

‘St Petersburg, the 4th of July 1824.

The Russian courier, who arrived the day before yesterday, handed me your little note of the 16th; to me it is one of the most precious of all those I have had the pleasure of receiving from you; I will retain it as if it were a title I had been honoured with, and I have the firm expectation and intimate conviction that I will soon present it to you in less mournful circumstances. I will follow, Monsieur le Vicomte, the example you have shown me, and not allow myself to reflect on the event which has so brusquely and so unexpectedly interrupted the relations which the service established between us; yet the nature of those relations, the confidence with which you honoured me, and the gravest of considerations, since they are not exclusively personal, will provide sufficient explanation of the motives and the whole extent of my regrets. What has happened still remains entirely inexplicable to me; I have no knowledge of the cause, but I see the effects of it; they were so easy, so logical, to foresee, that I am astonished so little concern is shown as to defy them. Yet I know too well the nobility of feeling that animates you, and the purity of your patriotism, to doubt that you will approve the course which I felt I should pursue in this situation; it was dictated by duty, by my love of country, and was even in the interests of your own glory; and you are too much of a Frenchman to accept the protection and support of strangers, in the circumstances in which you find yourself. You have gained the trust and esteem of Europe forever; but it is France you serve, it is her alone to whom you belong; she may prove unjust but neither you nor your true friends will ever allow your cause to be rendered less fine or pure by its defence being entrusted to foreign spokesmen. I have therefore suppressed all private feelings and considerations in favour of the common interest; I have avoided steps whose first effect would be to create dangerous division among us, and strike at the dignity of the throne. It is the last service I rendered here before my departure; you alone, Monsieur le Vicomte, have knowledge of it; confidence is due you, and I know the nobility of your character too well to doubt that you will keep my secret, and will find that my conduct, in the circumstances, conforms to the sentiments you have the right to demand of those you honour with your esteem and friendship.

Adieu, Monsieur le Vicomte: if the relationship I have had the happiness to enjoy with you has been able to provide you with a true idea of my character, you should know that changes of circumstance cannot influence my sentiments, and you will never doubt the attachment and devotion of one who, in the present circumstances, esteems himself the most fortunate of men in being considered one of your friends.

LA FERRONNAYS.

P. S. Messieurs de Fontenay and de Pontcarré feel most strongly the value of the memory of them which you choose to retain: witnesses, like me, to the increase in respect which France has gained since your entry into government, it is obvious that they share my sentiments and regrets.’

Book XXVIII: Chapter 4: Neuchâtel in Switzerland

BkXXVIII:Chap4:Sec1

I began the battles of my newly-established opposition immediately after my downfall; but they were interrupted by the death of Louis XVIII, and were not actively resumed until after Charles X’s coronation. In July, I re-joined Madame de Chateaubriand at Neuchâtel, she having gone there to await me. She had rented a cottage by the lake-shore. Before us, the Alpine chain stretched north and south to a great distance: we had our backs to the Jura, whose slopes black with fir-trees rose steeply above our heads. The lake was deserted; a wooden gallery served me for exercise. I recalled Milord Maréchal. When I climbed to the heights of the Jura, I could see Lake Biel to whose waves and breezes Jean-Jacques Rousseau owed one of his happiest inspirations. Madame de Chateaubriand was off to visit Fribourg and a country-house which we had been told was charming, but which she found chilly, even though it was nicknamed Little Provence. A thin black cat, half-wild, which caught little fish by dipping its paw into a large bucket filled with lake-water, was my only distraction. A tranquil old woman, who was always knitting, prepared our banquets on an earthenware stove, without moving from her chair. I had not lost the habit of eating like a field-mouse.

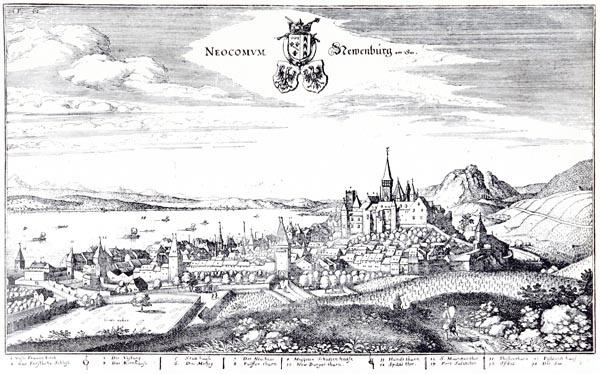

‘Neuchâtel au Dix-Septième Siècle, d'Après Merian’

Histoire de la Nation Suisse - Berthold van Muyden (p303, 1896)

The British Library

Neuchâtel has known moments of importance; it belonged to the Duchesse de Nemours; Jean-Jacques Rousseau walked, dressed as an Armenian, on its heights, and Madame de Charrière, so delicately observed by Monsieur de Saint-Beuve, described its society in her Lettres neuchâteloises: though Juliane, Mademoiselle de La Prise, and Henri Meyer, were not there; I only saw poor Fauche-Borel, out of the émigré past: he later threw himself from a window. Monsieur Pourtalès’ tidy gardens charmed me no more than did a rock from England erected by human hand in a neighbouring vineyard facing the Jura. Berthier, the last Prince of Neuchâtel, thanks to Bonaparte, was forgotten despite his little Simplon in the Val de Travers, and even though he shattered his skull in the same manner as Fauche-Borel.

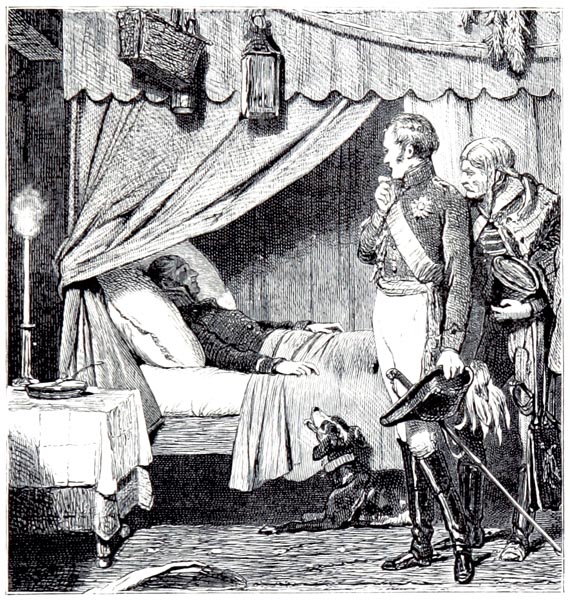

Book XXVIII: Chapter 5: The death of Louis XVIII – The coronation of Charles X

BkXXVIII:Chap5:Sec1

The King’s illness recalled me to Paris. The King died on the 16th of September, barely four months after my dismissal. My pamphlet, entitled ‘The King is dead: long live the King!’ in which I hailed the new sovereign, did for Charles X what my pamphlet ‘Of Bonaparte and the Bourbons’ had done for Louis XVIII. I went to seek Madame de Chateaubriand at Neuchâtel, and we returned to Paris, to lodge in the Rue du Regard. Charles X gained popularity at the start of his reign by abolishing censorship; his coronation took place in the spring of 1825. ‘Already the bees began to buzz, the birds to sing, the lambs to leap.’

I found the following notes, written at Rheims, among my papers:

‘Rheims, the 26th of May 1825.

The King arrives the day after tomorrow: his coronation will be on Sunday the 29th; I will see a crown placed on his head, a sight no one could have conceived of when I raised my voice in 1814. I helped to open the gates of France for him; I gave him champions, by conducting the Spanish War successfully; I ensured the Charter was adopted, and I knew how to raise an army, the two things with which the King could rule at home and abroad: what role was reserved for me at the coronation: that of an outcast. I have received a decoration, one indiscriminately awarded to a whole crowd of people, not even handed out by Charles X. The people I served, and won places for, have turned their backs on me. The King will take his hands in mine; he will see me at his feet without being moved, when I take the oath, as he has watched me recommence my woes without interest. Does it bother me? No. Delivered from any obligation to visit the Tuileries, freedom compensates me for everything.

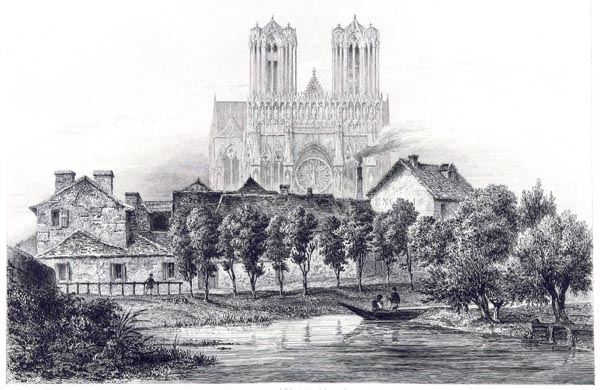

‘Notre Dame Cathedrale de Rheims, Vue Prise des Lavoirs’

Reims, la Ville de Sacres - Isidore Justin Séverin Taylor, Baron (p14, 1860)

The British Library

I write this page of my Memoirs in a room where I am forgotten amidst the noise. This morning I visited Saint-Rémi and the Cathedral decorated with hangings. I only have a clear idea of this last building because of the scenery in Schiller’s Jeanne d’Arc, which was performed before me in Berlin: theatrical design allowed me to see on the banks of the Spree what theatrical design will hide from me on the banks of the Vesle: for the rest, I entertain myself among the ancient dynasties, from Clovis and his Franks, and his pigeon descending from heaven, to Charles VII with Joan of Arc at his side.

“I come from my own country

no higher than a boot, yet,

it’s with a la, with a si,

And with my marmot.

One little sou, Monsieur, if you would!”

That was what a little Savoyard who had just arrived in Rheims, sang to me on my way back. “And what are you doing here?” I asked him. – “I’ve come for the Coronation, Monsieur. – With your marmot? – Yes, Monsieur, with a la, with a si, and with my marmot,” he replied, dancing and tumbling. – “Well I too, my lad!”

That was not true: I had come to the Coronation without a marmot, and a marmot is a great resource: in my coffers I only had an old daydream and I would scarcely be given a little sou by a passer-by to see that climb a stick.

Louis XVII and Louis XVIII had no coronation; that of Charles X followed in succession that of Louis XVI. Charles X was present at his brother’s coronation; he represented the Duke of Normandy, William the Conqueror. Under what happy auspices Louis XVI mounted the throne! How popular he was, succeeding Louis XV! And yet, what became of him? The actual Coronation will not be a Coronation, but merely the representation of a Coronation: we will behold Marshal Moncey, who acted at Napoleon’s Coronation: that Marshal, who once celebrated the death of the tyrant Louis XVI among his troops, we will see brandishing the Royal sword at Rheims, in his role as Count of Flanders or Duke of Acquitaine. Who is fooled by such antics? I would have wished for an absence of pomp, at this time: the King on horseback, the church bare, adorned only with its ancient vaults and its ancient tombs; the two Chambers present, the oath of loyalty to the Charter pronounced on the Gospel in a loud voice. This is the rebirth of the monarchy; it could be reborn in freedom and religion: unfortunately there is little love of freedom; but still, they might at least have a taste for glory!

‘Ah! Deep in their dusty tombs, the noble shades

Of all those valiant kings, what will they say?

What will Pharamond say, or Clodion or Clovis,

Our Pepins, our Martels, our Charles, and Louis,

Who, in the heat of war, with their own blood

Won, for their scions, this land so fair and good?’

In the end, has not the new style of coronation, when the Pope anointed a man as great as the founder of the second dynasty, destroyed, by transmuting the head anointed, the effect of our ancient and historic ceremony? The nation has been led to think that a pious rite sets someone on the throne, and renders it a matter of indifference which brow is chosen to receive the sacred oil. The extras at Notre-Dame de Paris, corresponding to those in the cathedral at Rheims, will be no more than obligatory players on a vulgar stage: the advantage remains with Napoleon who passes on his attendants to Charles X. The figure of the Emperor dominates everything these days. It looms behind events and ideas: the leaves of these inferior times in which we live wither beneath the gaze of his eagles.’

‘Rheims, Saturday, the eve of the Coronation.

I watched the King’s entry; I saw the gilded coaches of a monarch who had scarcely a horse to ride not long ago; I watched those carriages, filled with courtiers who found themselves unable to defend their master, roll by. That gang were off to the Cathedral to chant the Te Deum, while I went to view a Roman ruin and walk alone in a wood of elms known as the Wood of Love. I heard far off the jubilation of the bells, and I gazed at the towers of the Cathedral, age-old witnesses of that ceremony which is always the same and yet varies with history, the age, ideas, manners, practices and customs. The monarchy perished, and for some years the Cathedral was used as a stable. Does Charles X, seeing it today, remember that he saw Louis XVI anointed in the same place where he is to be anointed in his turn? Does he think that a Coronation can provide a defence against misfortune? There is no longer a hand virtuous enough to heal the King’s evil, no longer a holy phial so powerful as to render kings inviolable.’

Book XXVIII: Chapter 6: Reception of the Knights of the Orders

BkXXVIII:Chap6:Sec1

I wrote what you have just read hurriedly on the half-empty pages of a pamphlet entitled: ‘The Coronation; by Barnage of Rheims, lawyer’ and on a printed letter of the Grand Referendary, Monsieur de Sémonville, reading: ‘The Grand Referendary has the honour to inform his Lordship, Monsieur le Vicomte de Chateaubriand, that places are reserved in the chancel of Rheims Cathedral for such of the Peers who wish to be present the day after the Coronation of His Majesty at the reception ceremony for the Grand Master of the Orders of the Holy Ghost and of St Michael and the reception for Messieurs the Knights and Commanders.’

Charles X, however, intended to make his peace with me. The Archbishop of Paris spoke to him at Rheims about those in opposition: the King said: ‘Those who want nothing to do with me, I ignore.’ The Archbishop replied: ‘But Sire, Monsieur de Chateaubriand? – Oh, him I regret!’ The Archbishop asked the King if he could tell me so: the King hesitated, took two or three turns round the room and replied: ‘Well, yes, tell him!’ and the Archbishop forgot to say anything to me.

At the ceremony for the Knights of the Orders, I found myself kneeling at the King’s feet, just as Monsieur de Villèle was taking the oath. I exchanged a few polite words with my companion in knighthood, regarding a feather which had come loose from my hat. We left the Sovereign’s presence and all was done. The King, having had some difficulty in removing his gloves to take my hands in his, said to me with a laugh: ‘A gloved cat catches no mice.’ It was thought that he had spoken to me at length, and a rumour spread of my return to favour. It is probable that Charles X, thinking that the Archbishop had told me of his goodwill, expected a word of gratitude from me and was offended by my silence.

‘Charles X, d'Après un Portrait de Gérard’

L'Histoire de France Depuis 1789 Jusqu'en 1848, Racontée à mes Petits-Enfants, par M. Guizot. Leçons Recueillies par Madame de Witt, Vol 02 - François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (p627, 1878)

The British Library

Thus I was present at the last Coronation of the successors of Clovis; I had initiated it by the pages where I urged the Coronation, and described it in my pamphlet ‘Le Roi est mort: vive le Roi!’ Not that I had the slightest belief in the ceremony; but since the Legitimacy lacked all credibility, I had to use every argument to support it, however worthless. I recalled Adalbéron’s pronouncement: ‘The Coronation of a king of France is a public matter, not a private affair: publica sunt haec negotia, non privata’; I quoted the admirable prayer reserved for the Coronation: ‘O God, who by Thy virtues counsel Thy peoples, grant to this Thy servant the spirit of Thy wisdom! May these days see equity and justice born for all: succour for friends, hindrance for enemies, for the afflicted consolation, for the young correction, for the rich instruction, for the needy pity, for the pilgrim hospitality, for the poorer subject peace and protection in his homeland! Let him (the King) learn self-control, and to govern all men moderately according to their condition, so that, O Lord, he may set all people an example pleasing to Thee!’

‘The Anointing of Charles X. of France in the Cathedral of Rheims on May 29, 1825. From a Steel Engraving by Dien of the Original Painting by François Pascal Gérard (Versailles, Historical Gallery)’

A History of all Nations From the Earliest Times; Being a Universal Historical Library - John Henry Wright (p161, 1905)

Internet Archive Book Images

Before reproducing this prayer, recorded by Du Tillet, in my pamphlet, ‘Le Roi est mort: vive le Roi!’ I exclaimed: ‘Let us humbly beseech Charles X to imitate his ancestors: thirty-two sovereigns of the third dynasty have received the Royal unction.’

All my duties being fulfilled, I left Rheims and could say like Joan of Arc: ‘My mission is over.’

Book XXVIII: Chapter 7: I gather my former adversaries around me – My public changes

BkXXVIII:Chap7:Sec1

Paris put an end to its recent celebrations: the age of indulgence, reconciliation, and favour was past: sad reality alone was left us.

Since, in 1820, censorship had finished off the Conservateur, I lost no time recommencing, seven years afterwards, the same polemic in another form and using another printer. The men who fought alongside me on the Conservateur demanded, like me, freedom of thought and the pen: they were in opposition as I was, in disgrace like me, and they called themselves my friends. Achieving power in 1820, by my efforts even more than their own, they turned against the freedom of the press: from the persecuted, they became the persecutors; they ceased to be or to call themselves my friends; they maintained that Press licence only began on the 6th of June 1824, the day of my dismissal from government; their memories were short: if they had re-read the opinions they had stated, the articles they had written against another government, and in favour of the freedom of the Press, they would have been forced to admit that in 1818 and 1819 they were at least the seconds-in-command of licence.

On the other side, my former adversaries gathered round me. I tried to link the partisans of freedom to legitimate Royalty, with more success than I had rallied the servants of throne and altar to the Charter. My public had altered. I was obliged to warn the Government of the dangers of absolutism, after having protected it from popular preaching. Accustomed to show my readers respect, I did not deliver them a line that I had not written with all the care of which I was capable: so many of those little works of a day cost me more pain, in proportion, than the longest works from my pen. My life was incredibly busy. Honour and my country called me onto the field of battle. I had arrived at an age when a man needs peace and quiet; but if I had judged my years by the ever-increasing hatred that oppression and baseness aroused in me I would have thought myself young again.

I gathered around me a group of writers to give unity to my struggles. Among them were Peers, Deputies, Magistrates, and young authors starting out on their careers. There flocked to me Messieurs Montalivet, Salvandy, Duvergier de Hauranne, and plenty of others who were my pupils and who churn out today, as new, reflections on representative monarchy, things which I taught them, and appear throughout my works. Monsieur de Montalivet became Interior Minister and a favourite of Louis-Philippe; those who enjoy following the vagaries of destiny will find this letter quite interesting:

‘Monsieur le Vicomte,

I have the honour to send you a statement of the errors I have found in the table of judgements of the Royal Court which has been conveyed to you. I have verified them further, and I think I can attest to the correctness of the attached list.

Deign to accept, my dear Vicomte, the homage of profound respect with which I have the honour to be,

Your very devoted colleague and sincere admirer,

MONTALIVET.’

That did not prevent my devoted colleague and sincere admirer, Monsieur le Comte de Monalivet, so great a partisan in his time of the freedom of the Press, having me, as a protagonist of that freedom, committed to Monsieur Gisquet’s gaol.

A summary of my fresh polemics which lasted five years, but which finished by my triumphing, will convey the power of ideas that opposed events, even those backed by force. I was dismissed on the 6th of June 1824; on the 21st I entered the arena, I remained there until the 18th of December 1826: I entered alone, naked and despoiled, and I emerged victorious. It is history I write here, in making an extract of the arguments I employed.

Book XXVIII: Chapter 8: An extract from my polemic after my fall

BkXXVIII:Chap8:Sec1

‘We have had the courage and sense of honour to carry out a risky war in the presence of a free Press, and it is the first occasion that this noble spectacle has been demonstrated to the monarchy. We have quickly repented of our trust. We have braved the newspapers when they could only have been harmful to the success of our soldiers and officers; it is necessary to subjugate them when they dare to speak of clerks and ministers.

If those who administer the State appear to ignore the spirit of France completely in serious matters they are no less strangers to those matters of grace and ornament which mingle, to adorn it, with the life of civilised nations.

The riches which the Legitimacy expends on the arts exceed the aid that the usurper’s government accorded them; but how are they allocated? Sworn to omission by nature and taste, the dispensers of these riches seem to possess an antipathy for the famous; their obscurity is so invincible, that in approaching the illustrious they make them fade; one might say that they pour money over the arts in order to extinguish them, as over our freedom in order to stifle it.

Yet if the rack on which they place France to her discomfort resembles those detailed models which one examines with a magnifying glass in amateur collections, the minuteness of that inspection might interest for a moment but no more: it is a petty thing badly executed.’

‘We have said that the system followed by the administration at present harms the French spirit: we will try to prove that it equally misunderstands the nature of our institutions.

Monarchy has been re-established in France without effort, because it is dominant in our history, because the Crown is borne by a family which almost witnessed the birth of our nation, which formed it, civilised it, gave it all its liberties, rendered it immortal; but time has reduced that monarchy to something mundane. The age of myth in politics is over; we can no longer have a government of worship, religion and mystery: everyone knows their rights; nothing is possible if it ignores the bounds of reason; and including the granting of favours, the last illusion of absolute monarchy, everything now is weighed, everything is assessed.

Let us not deceive ourselves; a new era has begun for all nations; will it be a happy one? Providence alone knows. As for us, it is our task to prepare ourselves for future events. Let us not imagine that we can return to the past: there is no salvation for us except in the Charter.

Constitutional monarchy was not born among us systematically in writing, even though there is a printed Code; it is the child of time and event, like the ancient monarchy of our forefathers.

Why could freedom not survive within the edifice constructed by despotism, where it has left its traces? Victory, still adorned with the tricolour so to speak, has taken refuge in the Duc d’Angoulême’s tent; the Legitimacy occupies the Louvre, even though one can still see the eagles there.

In a Constitutional monarchy, public freedoms are respected; they are considered safeguards of the monarch, the people and the law.

We mean something different by Representative government. These people form a company (one might even say two rival companies, since competition is essential) to bribe newspapers with money. They do not hesitate to take scandalous action against proprietors who do not wish to sell themselves; they would prefer to oblige them to endure erroneous court arrest. Men of honour, repugnant to the calling, are enlisted, to support a Royalist government, libellers who have pursued the Royal family with their calumnies. They recruit all who served in the former police force and the Imperial ante-chambers; as among our neighbours, who, when they want to recruit sailors, press the taverns and suspect places. These galley-slaves of free writers have taken to the waves, in five or six bought newspapers, and yet what they say is called public opinion by Ministers.’

That is a much abridged, but perhaps still too lengthy, specimen of my polemic in my pamphlets and in the Journal des Débats: in it are found all the principles that people proclaim today.

Book XXVIII: Chapter 9: I refuse the pension the Minister of State wishes to pay me – The Greek Committee – Monsieur Molé’s note – A letter from Canaris to his son – Madame Récamier sends me an extract from another letter – My complete works

BkXXVIII:Chap9:Sec1

When they drove me from government, they did not give me my pension as a Minister of State; and I did not claim it; but Monsieur de Villèle, following a remark of the King’s, decided to despatch a fresh pension certificate to me via Monsieur de Peyronnet. I rejected it. Either I had the right to my former pension, or I did not: in the former case, I did not require a new certificate; in the latter, I did not wish to owe my pension to the President of the Council.

The Hellenes shook of their yoke: a Greek committee was formed in Paris of which I made one. The committee met at Monsieur Ternaux’s, in the Place des Victories. The members of the society would arrive in succession at the debating chamber. General Sebastiani would declare, as soon as he was seated, that it was a shocking business; he would elaborate endlessly: which displeased our energetic president Monsieur Ternaux, who was happy to manufacture shawls for Aspasia, but would not waste his time on her. Monsieur Fabvier’s speeches made the committee suffer; he grumbled at us a great deal; he held us responsible for what did not take place according to his views, it was we who failed to win the battle at Marathon. I devoted myself to Greek independence: it seemed to me like fulfilling a filial duty towards one’s mother. I wrote a Note on Greece; I addressed myself to the successors of the Russian Emperor, as I had addressed myself to the Emperor in person at Verona. The Note was printed and then reprinted at the front of the Itinerary.

I worked for the same cause in the Chamber of Peers, in order to stir the body politic into life. This note of Monsieur de Molé’s reveals the obstacles I encountered and the round-about methods I was forced to employ:

‘You will find us all ready tomorrow, at the opening session, to follow your lead. I am going to write to Lainé if I cannot find him. It is only necessary for him to allow for the phrasing concerning the Greeks; but be careful they do not counter your move by restricting any amendments and, rulebook in hand, refuse you. They may suggest lodging your proposal with the bureau: you could do that as well, after saying all you need to say. Pasquier happens to be quite unwell, and I fear he will not be on his feet tomorrow. As for a vote, we will have one. What will do better still is the arrangement you have made with your booksellers. It is a fine thing to restore by means of it all that the injustice and ingratitude of men has taken from us.

Yours for life,

MOLÉ.’

Greece was freed of the Islamic yoke; but, instead of a federal republic, as I desired, a Bavarian monarchy was established in Athens. Now, since Kings are lacking in memories, I who had done a little service to the Argives’ cause, heard tell of them in future only in Homer. Greece, once free, did not say: ‘Thank you.’ She ignored my name as much as, and more than, in the days when I wept over her ruins while crossing her wastes.

Hellas, before royalty, had been more grateful. Among various children the Committee educated was young Canaris: his father, distinguished as a naval commander by his efforts at Mycale, wrote him a note which the child translated into French on a blank sheet at the end of the letter. The boy sent me the dual text; I have kept it as a tribute to the Greek Committee:

‘My dear boy,

Not every Greek has the good fortune you have had: that of being selected by the benevolent Committee which interests itself in us in order to teach men their duties. I begot you; but these commendable gentlemen will give you an education which will truly make a man of you. Be dutiful as regards the counsels of your new fathers, if you would console the last years of one who gave you to the light. Be well.

Your father,

C. CANARIS.

Napflion (Napoli de Romanie), the 5th of September 1825.’

Republican Greece gave witness to private regrets when I left the government. Madame Récamier wrote to me from Naples on the 29th of October 1824:

‘I have received a letter from Greece which made a long detour before reaching me. In it I found several lines regarding you which I would like you to know of; these are they:

“The decree of the 6th of June has arrived, and has had a strong effect on our leaders. Their deepest hopes being vested in France’s generosity, they are asking themselves anxiously what the dismissal of a man whose character presaged future support for them might mean.”

If I am not wrong this homage will please you. I enclose the letter: its first page only concerns me.’

You will soon read about Madame Récamier’s life: you may guess how sweet it was to me to receive a memory of the land of the Muses from a woman who adorns them.

As for the note from Monsieur Molé given above, it makes allusion to the contract I had agreed regarding the publication of my Complete Works. That arrangement should, indeed, have assured me a life of ease; it nevertheless turned sour, even though it has worked out well for the publishers to whom Monsieur Ladvocat, after his bankruptcy, left my Works. Vis à vis Plutus or Pluto (the mythologists confuse the two) I am like Alcestis, I am forever seeing the fatal barque; like William Pitt, and that is my excuse, I am a leaking basket; but I did not myself make the hole in the basket.

At the end of the general preface to my Works (1826, Volume I) I address France thus:

‘O France, my dear country, my first love, one of your sons, at the end of his career, displays beneath your gaze any title he might have to your kindness. If he can do no more for you, you can do all for him, by declaring that his attachment to your religion, your king, and your freedom, has been acceptable to you. Famous and beloved land, I have only desired glory in order to add to yours.’

Book XXVIII: Chapter 10: A trip to Lausanne

BkXXVIII:Chap10:Sec1

Madame de Chateaubriand, being ill, took a trip to the south of France, and feeling no better, returned to Lyons, where Doctor Prunelle condemned her condition. I went to meet her; I took her to Lausanne, where she gave the lie to Monsieur Prunelle. I stayed at Lausanne alternately with Monsieur de Sivry and Madame de Cottens, an affectionate, spiritual but unfortunate woman. I met Madame de Montolieu; she lived in retirement on a lofty hillside; she pined away amongst romantic illusions, like Madame de Genlis, her contemporary. Gibbon had composed his History of the Roman Empire at my very door: ‘It was among the ruins of the Capitol’, he wrote, in Lausanne, on the 27th of June 1787 ‘that I first conceived the idea of a work which has amused and exercised near twenty years of my life.’ Madame de Staël had appeared in Lausanne with Madame Récamier. All the émigrés, a whole past world, stayed for a while in that sad and smiling city, a kind of imitation Granada. Madame de Duras has evoked the memory in her Memoirs and this letter told me of a fresh loss to which I was condemned:

‘Bex, 13th of July 1826.

It is finished, Monsieur, your friend exists no more. She has rendered her soul to God, painlessly, this morning at a quarter to eleven. She was still out in her carriage yesterday evening. Nothing suggested so immediate a death; what can I say, we did not think her illness would end thus. Monsieur de Custine, whose grief does not allow him to write to you himself, was even out in the mountains round Bex yesterday morning, to arrange a daily delivery of mountain milk for the dear invalid.

I am too oppressed by grief myself to enter into lengthy details. We are preparing to return to France with the precious remains of that best of mothers and friends. Enguerrand will lie between his two mothers.

We will pass through Lausanne, where Monsieur de Custine will seek you out as soon as we arrive.

Accept, Monsieur, the assurance of respectful attachment with which I am, etc.

See my earlier and later comments, to discover what I have had the pleasure and misfortune to recall regarding my memories of Madame de Custine.

The Letters written from Lausanne, a work of Madame de Charrière, gives a good description of the scenery that met my eyes each day, and the feelings of grandeur it inspired: ‘I take my rest in solitude,’ says Cécile’s mother, ‘by an open window which overlooks the lake. I thank you, mountains, snow, sunlight, for all the pleasure you give me. I thank You, Creator of all I see, for having made these things so delightful to see. Fine and glorious beauties of nature! My eyes admire you every day, and every day you register yourself within my heart.’

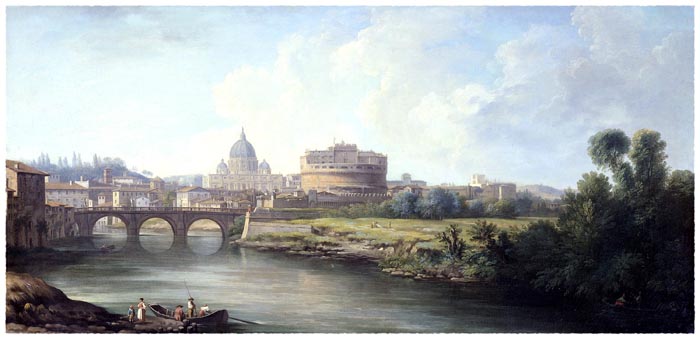

‘View of Lausanne’

Enea Vico, Clemens Agatius, c. 1543 - c. 1567

The Rijksmuseum

In Lausanne, I began my Notes on the first work I wrote, the Essai sur les Revolutions anciennes et modernes. From my windows I could see the rocks of Meillerie:

‘Rousseau,’ I wrote in one of these Notes, ‘only really goes beyond other authors of his age in sixty or so letters of La Nouvelle Héloïse, in a few pages of his Rêveries and his Confessions. There, revealing the true nature of his talent, he arrives at a passionate eloquence before him unknown. Voltaire and Montesquieu proved stylistic models for writers of the century of Louis XIV; Rousseau, and to some extent Buffon, in another genre, created a language unknown to that great century.’

Book XXVIII: Chapter 11: Return to Paris – The Jesuits – A Letter from Monsieur de Montlosier and my reply

BkXXVIII:Chap11:Sec1

On returning to Paris, my life was occupied by my household on the Rue d’Enfer, my renewed struggles in the Chamber of Peers and my pamphlets opposing various proposed laws in conflict with public freedom; by my speeches and my writings in support of the Greeks, and my efforts towards my Complete Works. The Emperor of Russia had died, and with him the only Royal friendship that remained to me. The Duc de Montmorency had become tutor to the Duc de Bordeaux. He did not enjoy that weighty honour long: he died on Good Friday 1826, in the Church of Saint-Thomas-Aquinas, at the hour when Jesus died on the cross; he went to God with Christ’s last sigh.

Battle was commenced against the Jesuits; banal and tiresome declamations were made against that illustrious Order, which, it must be admitted, concealed something disturbing within it, for a mysterious cloud of darkness covered all the affairs of the Jesuits.

Regarding the Jesuits, I received this letter from Monsieur de Montlosier, and sent him the reply which you will find following the letter.

Ne derelinquas amicum antiquam,

Novus enim non erit similes illi. (Ecclesiastes IX,10)

(Do not forsake an old friend, since the new cannot equal him)

‘My dear friend, those words are not only very ancient, they are not only very wise; for Christians, they are sacred. I invoke in you all the authority they may possess. Reconciliation is never necessary between old friends, or between good citizens. To close ranks, to tighten the bond between us, by emulation to strengthen all our vows, increase all our efforts, stimulate all our feelings, is a duty demanded by the eminently deplorable state of king and country. In addressing these words to you, I do not ignore the fact that they will be received by a heart torn by ingratitude and injustice; and yet I still address them to you with confidence, certain as I am that there is light beyond the darkness. On this delicate issue, my dear friend, I do not know whether you are pleased with me; but, in the midst of your tribulations, if I have chanced to hear you accused, I have not troubled to defend you: I have not even listened. I said to myself: and if that should be so? I am not sure that Alcibiades was not showing a little too much anger when he threw a rhetorician out of his own house for not possessing the works of Homer. I am not sure that Hannibal was not showing a little too much violence when he ejected a senator, who spoke against his opinion, from his headquarters. If I were to confess my thoughts on the subject of Achilles, perhaps I would not approve his exiling himself from the Greek army because of some young girl who was stolen from him. After that, it is enough to pronounce the names Alcibiades, Hannibal, Achilles, for all disagreement to be over: it is the same today with the iracundus and inexorabilis, the irascible and inexorable, Chateaubriand. Once his name is pronounced, all is said. At that name, when I say to myself: he is complaining, I feel my tenderness stirred; when I say to myself: France needs him, I feel myself filled with respect. Yes, my friend, France needs you. She shall need you still more; through you she has recovered her love of her religion and her ancestors: that benefit must be maintained; and for that, she must be dragged away from the errors of her priests, to drag those priests themselves away from the fatal slope on which they are standing.

My dear friend, you and I have struggled for many years. It is left to us to preserve the King and the State from the preponderance of ecclesiastics who call themselves religious. In former times, the evil and its roots were within us; we could circumvent and master it. Today the branches which cover us within have their roots outside us. The private doctrines of the race of Louis XVI and Charles I have given way to the tainted doctrines of Henri IV and Henri III. Neither you nor I surely can support this state of things; it is in order to unite with you, to receive your approbation which will encourage me, and offer you like a soldier my loyalty and arms, that I write to you.

It is with these sentiments of admiration for you and a true devotion to you that I tenderly and respectfully implore you.

Comte de MONTLOSIER.

Randanne, the 28th of November 1825.’

‘TO MONSIEUR DE MONTLOSIER

Paris, this 3rd of December 1825.

Your letter, my dear old friend, is very serious, and yet it made me smile in regard to myself. Alcibiades, Hannibal, Achilles! You cannot be serious regarding all that. As for the son of Peleus’ young girl, if that refers to my portfolio, I protest that I barely loved the faithless one three days, and have not experienced a quarter of an hour’s regret. My resentment: that is another matter. Monsieur de Villèle, whom I sincerely and cordially like, has not only foregone the duties of friendship, the public signs of attachment I showed him, the sacrifices I made for him, but even the simplest of courtesies.

The King no longer requires my services, nothing then is more natural than to dismiss me from his Council; but the manner of it means everything to a gentleman, and as I have not stolen the King’s clock from his mantelpiece, I ought not to be hunted down as if I had. I merely made war in Spain and kept the peace in Europe during a dangerous period; through this alone I created an army for the Legitimacy, and I have been ejected from my place, by all the Restoration Ministers, without any mark of recognition from the Crown, as if I had betrayed Prince and country. Monsieur de Villèle thinks I will accept such treatment: he is mistaken. I have shown my sincerity: I will be an irreconcilable enemy. I am born under a cloud: the wounds I have received never close.

But this is all about me: let us speak of something more important. I am afraid I do not agree with you on weighty matters, and I am sorry for it! I desire the Charter, the whole Charter, the freedom of the public to its whole extent. Do you wish that?

I desire religion as you do; I hate the congregation and these associations of hypocrites who make spies of my servants, and who only seek power at the altar. But I believe that the clergy, once rid of these parasitic plants, can easily form part of a constitutional regime, and even become the prop for our new institutions. Do you not seek too strongly to sow division among the political order? Here I give you a proof of my extreme impartiality. The clergy, who, I hate to say it, owe me so much, do not like me, and have never defended me, nor rendered me any service. Does it matter? It is a question of being just, and seeing what is fitting for religion and the monarchy.

My dear friend, I do not doubt your courage; you will do, I am convinced, everything which seems right to you, and your talents guarantee you victory. I await your future communications, and I embrace with all my heart my loyal companion in exile.

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

Book XXVIII: Chapter 12: More of my polemics

BkXXVIII:Chap12:Sec1

I resumed my polemics. Every day I skirmished, and fought battles in the vanguard, with the soldiers of the Ministerial staff; they did not always use their swords effectively. In the first two centuries of Rome, they punished horsemen who held back from the charge, because they were too heavy, or not brave enough, condemning them to suffer heavy losses: I tasked myself with their punishment.

‘The universe around us is changing,’ I said: ‘new nations are appearing on the world-scene; ancient nations are reviving in the midst of ruin; astonishing discoveries promise an imminent revolution in the arts of peace and war: religion, politics, ways of life, all take on a new character. Do we take note of this movement? Are we in tune with society? Are we pursuing the trend of the age? Are we ready to hold our place in the transformation or development of civilisation? No: the men who lead us are as much strangers to the state of things in Europe as the latest tribes to be discovered in the heart of Africa. What do they understand? The Stock Exchange! And they understand that inadequately. Are we condemned to bear the burden of obscurity, to punish ourselves for having suffered the yoke of glory?’

The transactions regarding Santo Domingo supplied me with the opportunity to develop several arguments regarding our public rights, which no one had considered.

Reaching the noblest of conclusions and announcing the transformation of the world, I replied to those opponents who cried: ‘What! We may be Republicans some day? Drivel! Who dreams of a Republic these days? etc etc.’

‘Rationally devoted to monarchical order,’ I replied, ‘I consider constitutional monarchy the best form of government possible at this stage of society.

But if one wishes to reduce everything to personal interests, if one supposes that I believe I would have anything to fear personally from a Republican State, one is in error.

Could it treat me any worse than the monarchy has? Twice or thrice despoiled by it, or by the Empire, which would have done everything for me if I had wished, could it have repudiated me more savagely? I have a horror of slavery; liberty delights my innate love of independence; I prefer that liberty expressed in a monarchical order of things, but I can conceive of it in a popular form. Who has less to fear from the future than I? I possess what no revolution can steal from me: without post, without honour, without wealth, any government not so foolish as to ignore public opinion is obliged to assign me some value. Popular governments especially are composed of individuals, and create common worth from the particular worth of each citizen. I will always be sure of public esteem, because I will never do anything to forgo it, and I may find more justice perhaps among my enemies than among my so-called friends.

Thus, all things considered, I would be unafraid of a republic, as I would be without antipathy towards its freedom: I am not a king; I am not waiting to be crowned; it is not my own cause I plead.

I have said, under another government, and regarding that government, that one morning they would seat themselves at the window to watch the monarchy go by.

I said to the present Ministers: “If you go on as you are, the whole revolution would, in due time, boil down to a new version of the Charter in which one would be content merely to alter one or two words.”’

I have highlighted these final phrases to fix the reader’s eye on a striking prediction. Now that even opinions are in disorder, and every man utters wrongly and awry whatever passes through his brain, these Republican ideas expressed by a Royalist during the Restoration still seem daring. As regards the future, so-called progressive spirits own the initiative in nothing.

Book XXVIII: Chapter 13: A letter from General Sébastiani

BkXXVIII:Chap13:Sec1

My later articles even stirred up Monsieur de Lafayette who, as sole compliment, sent me a laurel leaf. The effect of my views, to the great surprise of those who had no belief in them, made itself felt, from the booksellers who sent a deputation to me, to the parliamentarians who were initially furthest from my politics. The signature on the letter shown below, as proof of what I claim, caused some astonishment. It is only necessary to note the signature of this letter, and the alteration in the ideas and position of him that wrote it and him that received it: as for the wording, I am Bossuet and Montesquieu, that goes without saying; we authors, that is our daily bread, just as Ministers are always Sully and Colbert.

‘Monsieur le Vicomte,

Permit me to associate myself with the general admiration for you: I have experienced the sentiment for far too long to resist the desire to express it to you.

You have united the pride of Bossuet with the profundity of Montesquieu: you have rediscovered their pen and their genius. Your articles provide a great education for Statesmen.

In the new style of warfare you have initiated, you recall the powerful hand of he who, in other battles, also filled the world with glory. May your successes be more lasting: they concern our country and mankind.

All those who, as I do, embrace the principles of constitutional monarchy, are proud to find in you their noblest interpreter.

Accept, Monsieur le Vicomte, fresh assurance of my highest esteem.

HORACE SÉBASTIANI.

Sunday, the 30th of October.’

Thus friends, enemies, adversaries fell at my feet at the moment of victory. All the faint-hearts and ambitious types who thought me lost saw me rise again, radiant, from the clouds of dust shrouding the lists: it was my second Spanish War; I triumphed over all the parties at home as I had triumphed abroad over France’s enemies. It had been necessary to pay with my person, just as with my despatches I had paralysed and rendered vain the despatches of Prince von Metternich and Mr Canning.

‘Metternich’

Stories of Persons and Places in Europe - E. L. Benedict (p270, 1887)

Internet Archive Book Images

Book XXVIII: Chapter 14: The death of General Foy – The Law of Love and Justice – A letter from Monsieur Étienne – A letter from Benjamin Constant – I reach the summit of my political importance – An article regarding the King’s name-day – Withdrawal of the law on the policing of the press – Paris illuminated – Monsieur Michaud’s note.

BkXXVIII:Chap14:Sec1

General Foy and the Deputy, Manuel, had died and stolen from the left-wing opposition its finest orators. Monsieur de Serre and Camille Jordan had also descended into the grave. Even from my chair in the Academy I was obliged to defend the freedom of the Press despite the whimpering pleas of Monsieur de Lally-Tolendal. The law on policing the Press, which was named the law of love and justice, owed its rejection principally to my attacks. My Opinion on this proposed law is a historically interesting work; I received a number of compliments among which two names are worth noting.

‘Monsieur le Vicomte,

I am sensible of the thanks you have chosen to address to me. You term a kindness something which I regarded as a debt, and I was happy to pay it to the eloquent writer. All true friends of letters associate themselves with your triumph and ought to regard themselves as identified with your success. Far off, as near, I will support you with all my power, if it is possible that you have need of efforts as feeble as mine.

In an enlightened century like ours, genius is the sole force which can rise above the consequences of disgrace; it belongs to you, Monsieur, to furnish living proof of it to those who rejoice in it, as well as those who have had the misfortune to grieve over it.

I have the honour to be, with the most distinguished esteem, yours etc, etc.

‘Paris, this 5th of April 1827.

I am rather late, Monsieur, in thanking you for your admirable speech. Trouble with my eyes, work in the Chamber, and furthermore the dreadful sessions of that Chamber, must serve as my excuse. You know moreover how my mind and spirit agree with all you say and are in sympathy with all the good you strive to do our unfortunate country. I am happy to add my feeble efforts to your powerful influence, and the madness of a government which is tormenting France and wishes to degrade it, while disquieting me as to its immediate results, consoles me with the certainty that such a state of things cannot long endure. You will have contributed powerfully to ending it, and if I am worthy one day to have my name placed after yours in the struggle which must be maintained against such foolishness and criminality, I will judge myself well compensated.

Accept, Monsieur, the homage of sincere admiration, profound respect and the highest esteem.

BENJAMIN CONSTANT.

Paris, this 21st of May 1827.’

It is at the moment of which I speak that I attained the summit of my political importance. With the War in Spain I had mastered Europe; but violent opposition countered me in France: after my fall, I became the avowed master of public opinion at home. Those who accused me of having committed an irreparable fault in taking up the pen once more were forced to acknowledge that I had created an empire more powerful than the first. The youth of France came over completely to my side and have never since quit me. Among several industrial sectors, the workers were at my command, and I could not take a walk in the street without being mobbed. Where did my popularity come from? From the fact that I had understood the true spirit of France. I was left with only a single newspaper to fight with, and I became master of all the others. My bravery sprang from my indifference: as it would have been just the same to me if I had failed, I achieved success without being embarrassed by the possibility of defeat. I was left with my own satisfaction, since what does past popularity matter to anyone today, something rightly effaced from everyone’s memory?

The King’s name day arrived, and I took the opportunity to express a loyalty which my liberal opinions had not altered. I published this article:

‘A truce with the King!

Peace today to the Ministers!

Glory, honour, long life and lasting happiness to Charles X! It is St Charles’ Day!

The history of Charles X should be asked of me especially, as a former companion in exile of our monarch.

You, French men and women who have not been forced to leave your country, you moreover who have only welcomed a Frenchman who would relieve you of Imperial despotism and the foreign yoke, inhabitants of a great and fine city, you who have only seen a fortunate Prince: when you pressed round him on the 12th of April 1814, touching the sacred hands with tears of emotion, when you discovered all the grace of youth on a brow ennobled by age and misfortune, as one sees beauty through a veil, you saw only virtue triumphant, and you led the son of kings to the royal seat of his ancestors.

But we, we have seen him sleeping on the ground, like us without a refuge, like us proscribed and despoiled. Well, that kindness which charms you was the same then; he bore misfortune as he bears the crown today, without finding the burden too great, with that Christian mildness which tempers the brightness of his influence, as it softens the brightness of his prosperity.

Charles X’s benefactions are added to all the benefactions his ancestors lavished on us: the name-day of a Christian king is a feast of thanksgiving for the French: allow us then the transports of gratitude with which it should inspire us. Let nothing enter for a moment into our souls that might render our joy less pure! For Heaven’s sake.! We would break our truce! Long Live the King!’

My eyes filled with tears while copying out my polemic, and I no longer have the courage to continue with my extracts. Oh! My King! You whom I saw on foreign soil, I saw you again on that same soil where you went to die. When I fought with such ardour to snatch you from the hands which were beginning to destroy you, judge by the words which I have just transcribed whether I was your enemy or rather the most tender and sincere of your servants! Alas! I speak and you can no longer hear me.

The proposal regarding a law to police the Press having been withdrawn, Paris was illuminated. I was struck by this public display, an evil omen for the monarchy: opposition had passed to the people, and the people, by its very nature, transformed opposition into revolution.

Hatred for Monsieur de Villèle began to increase; the Royalists, as in the days of the Conservateur, were ranked behind me again as supporters of the constitution: Monsieur Michaud wrote to me:

‘My honourable Lord,

Yesterday I printed the announcement of your work on the censure; but the entry, comprising two lines, has been deleted by the Censors. Monsieur Capefigue will explain to you why we have not set it in black and white.

If God does not come to our aid, all is lost; Royalty is like the unhappy Jerusalem in the hands of the Turks, its own children scarcely dare approach it; what a cause we sacrifice ourselves for!

MICHAUD.’

Book XXVIII: Chapter 15: Monsieur Villèle’s annoyance – Charles X decides to review the National Guard on the Champ-de-Mars – I write to him: my letter

BkXXVIII:Chap15:Sec1

The Opposition had finally provoked Monsieur de Villèle’s cool temperament into irascibility, and rendered Monsieur de Corbière’s destructive spirit despotic. The latter had stripped the Duc de Liancourt of seventeen charitable posts. The Duc de Liancourt was no saint, but in him one knew a benefactor, to whom philanthropy had awarded the title venerable; through the sanctity time gives, former revolutionaries are no longer referred to except with an epithet like Homer’s gods: it is always the respectable Monsieur so and so, always the inflexible citizen so and so, who, like Achilles, never ate pap (a-chylos). On the occasion of a scandal arising during Monsieur de Liancourt’s obsequies, Monsieur de Sémonville, in the Chamber of Peers, said: ‘Be at ease, Gentlemen, it will not happen again; I will conduct you to the cemetery myself.’

In April 1827, the King decided to review the National Guard on the Champ-des-Mars. Two days before that fateful review, urged on by my zeal and only asking to lay down my arms, I addressed a letter to Charles X which was passed on to him by Monsieur de Blacas and whose receipt he acknowledged by this note:

‘I have not lost an instant, Monsieur le Vicomte, in passing on to the King the letter which you have had the honour to address to His Majesty; and if he deigns to entrust a reply to me, I will be no less eager in ensuring it reaches you.

Accept, Monsieur le Vicomte, my most sincere compliments.

BLACAS D’AULPS.

‘This 27th April 1827, at one o’clock.’

TO THE KING.

Sire,

Permit a loyal subject, whom troubled times will always find at the foot of the throne, to communicate a few reflections he thinks useful to the glory of the throne, as to the happiness and security of the King.

Sire, it is only too true, there is danger to the State: but it is equally certain that this danger will be trivial if the principles of government themselves are not thwarted.

A great secret has been revealed, Sire: your Ministers have had the misfortune to inform France that certain people who were said no longer to exist are still alive. Paris, for twice twenty-four hours, has shaken off all authority. The same scenes are being repeated throughout France: the factional elements will not forget this foray.

But popular gatherings, so dangerous to absolute monarchies, because they take place in the presence of the monarch himself, are of little note in representative monarchies, because they are not in contact with him except via his Ministers or the law. Between the monarch and his subjects lies a barrier which restrains everyone: the two Chambers and the public institutions. Outside of these movements, the King will always see his authority and his sacred person protected.

But, Sire, there is one condition which is indispensable to general security, it concerns the spirit of the institutions: your council’s resistance to that spirit renders the popular movements as dangerous in a representative monarchy as in an absolute one.

From theory I pass to practice:

Your Majesty will appear at the review: you will be received there as you should be; but it is possible that among the shouts of ‘Long Live the King!’ other shouts will be heard which will make known to you the opinion of the public regarding your Ministers.

Furthermore, Sire, it is false that there is at present, as is claimed, a Republican faction; but it is true that there are supporters of illegitimate monarchy: now, the latter are too skilful not to take advantage of the occasion and mingle their cries on the 29th with those of France demanding change.