Cornelius Tacitus

The Annals

Book XIII: XXXIV-LVIII - War in Armenia and Germany

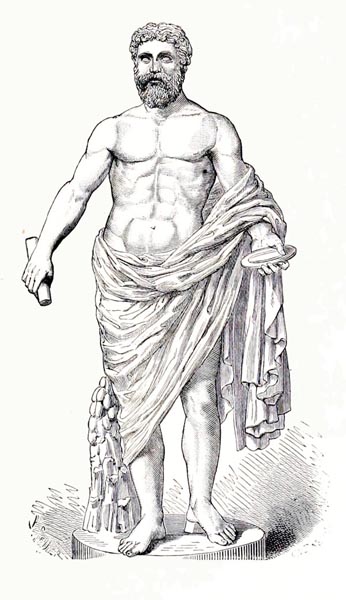

‘Statue of Jupiter’

History of Rome and the Roman people, from its origin to the establishment of the Christian empire - Victor Duruy (1811 - 1894) (p92, 1884)

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2017 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XIII:XXXIV War against Parthia renewed.

- Book XIII:XXXV Corbulo advances.

- Book XIII:XXXVI Paccius Orfitus is routed.

- Book XIII:XXXVII Tiridates, under threat, seeks peace.

- Book XIII:XXXVIII Corbulo and Tiridates fail to meet.

- Book XIII:XXXIX Corbulo reduces the Armenian fortresses.

- Book XIII:XL Tiridates attacks, then retreats.

- Book XIII:XLI Corbulo takes Artaxata.

- Book XIII:XLII Publius Suillius accused.

- Book XIII:XLIII Suillius claims that he was simply obeying orders.

- Book XIII:XLIV The trial of Octavius Sagitta.

- Book XIII:XLV The rise of Poppaea Sabina.

- Book XIII:XLVI Mistress to Nero.

- Book XIII:XLVII Cornelius Sulla banished to Marseilles.

- Book XIII:XLVIII The situation in Puteoli (Pozzuoli) resolved.

- Book XIII:XLIX Thrasea justifies his approach.

- Book XIII:L The question of indirect taxation.

- Book XIII:LI Nero tightens the control of taxation.

- Book XIII:LII The trials of Sulpicius Camerinus and Pompeius Silvanus.

- Book XIII:LIII Lucius Vetus proposes a Saône-Moselle canal.

- Book XIII:LIV Trouble with the Frisians.

- Book XIII:LV Boiocalus addresses Avitus.

- Book XIII:LVI Avitus rejects his pleas.

- Book XIII:LVII Tribal warfare and the Cologne fire.

- Book XIII:LVIII The fig-tree, the Ruminalis, in the Comitium is renewed.

Book XIII:XXXIV War against Parthia renewed

Nero being consul for a third time (AD58), Valerius Messala joined him as his colleague, his great-grandfather, the orator Corvinus, being remembered, as I write, by only a few of the very old, as colleague (AD31) to the divine Augustus, the great-great grandfather of Nero, in that same role. However the honour of a noble ancestry required the support of an annual subsidy of five thousand gold pieces, such that Messala could maintain an honest poverty. The emperor also granted a yearly stipend to Aurelius Cotta and Haterius Antoninus, even though their profligacy had dissipated their family estates.

At the start of the year, the struggle between Parthia and Rome for possession of Armenia, which had begun quietly, and been deferred till now, was pursued with energy. For Vologeses I of Parthia refused to allow his brother, Tiridates I of Armenia, to be barred from a kingdom which he himself had granted him, or to hold it as a gift from an alien power, while on our side Corbulo considered that the majesty of the Roman people was owed the recovery of possessions once held by Lucullus and Pompey.

Added to that, the Armenians, of dubious loyalty, were invoking the aid of both sides, though by their geography, and the similarity of their way of life, they were closer to the Parthians, with whom they intermarried, and under whom, being ignorant of true freedom, they were more inclined to accept servitude.

Book XIII:XXXV Corbulo advances

Corbulo’s main difficulty, however, was rather countering his troops’ lethargy than enemy treachery: since the legions transferred from Syria, sluggish after a long peace, tolerated their duties in a Roman camp only reluctantly. It was well enough known that his army contained veterans who had never mounted guard, or stood on watch, who viewed ditches and ramparts as something strange and wonderful, had neither helmets nor breastplates but, sleek and prosperous, had served their time in town. So, after dismissing the aged and sick, he sought reinforcements.

Levies were raised throughout Galatia and Cappadocia, and a legion from Germany was added, with its complement of auxiliary horse and foot. The whole army was kept under canvas, though the winter weather was so fierce that the ice-covered ground had to be dug over to provide pitches for the tents. Many of the men had frostbite from the force of the cold, and a few died while on sentry-duty. One soldier was seen carrying a bundle of firewood, his hands so frozen to his load that they were torn from his arms when it fell.

Corbulo himself, lightly clothed and bare-headed, frequently amongst them on the march, or at their labours, praising the strong, comforting the weak, was an example to them all. Then objection to orders, and desertion, became so frequent due to the harsh climate and the military task, that the remedy was sought in greater severity.

Indeed, contrary to the rule elsewhere, no pardon was granted for first and second offences, but whoever relinquished the standard immediately paid with his life. It was clear that this procedure had a salutary effect, and was more effective than showing sympathy: since the camp experienced fewer desertions than in those where exemptions were granted.

Book XIII:XXXVI Paccius Orfitus is routed

Meanwhile, until spring came, Corbulo kept the legions encamped, and positioned the auxiliary cohorts at suitable locations, with orders not to attack first: giving command of these garrison-posts to Paccius Orfitus, who had held the rank of leading centurion. Though Paccius sent word in writing that the barbarians were off guard and there was the chance to mount a successful action, he was ordered to stay within the lines awaiting stronger forces.

However, when a few inexperienced squadrons arrived from the nearest fort, and cried out for battle, he broke orders, engaged the enemy, and was routed. And his failure so terrified the troops who ought to have come to his rescue, they beat a hasty retreat to their various camps.

The incident vexed Corbulo considerably, and reprimanding Paccius he ordered him, with his prefects, and men, to bivouac outside the rampart, in which humiliating position they remained until reprieved following a petition from the entire army.

Book XIII:XXXVII Tiridates, under threat, seeks peace

Meanwhile Tiridates, now supported not merely by his own vassals, but by assistance from his brother Vologeses, began to attack Armenia, no longer by stealth, but in open warfare, destroying those he considered loyal to ourselves or, if troops were led against him, avoiding contact, and flying here and there, terrifying the populace more by rumour than the sword.

Corbulo, frustrated by an endless quest for battle, and forced to follow his enemy’s example in pursuing war everywhere, divided his forces so that legates and prefects might attack together but at diverse locations. At the same time, he advised Antiochus IV of Commagene to advance on the neighbouring prefectures. For Pharasmanes I of Iberia, who had executed his son Radamistus as a traitor, was now, as a witness to his loyalty to us, readily pursuing his old feud with the Armenians; while, for the first time, the Moschi of Armenia, a tribe previously allied to Rome, were now won to his cause and raided the Armenian wilderness.

Thus Tiridates’ strategy was completely overturned, and he sent ambassadors, demanding in his own name and that of Parthia why, after the recent grant of hostages and renewal of friendship, meant to open the way to further favour, he was being expelled from his long-standing possession of Armenia. Indeed, he said, Vologeses had made no move himself, simply because they both preferred to act with reason and not by force: but if the warfare continued, the House of Arsaces lacked none of that courage and good-fortune which had resulted several times already in Roman defeat.

To this, Corbulo, who was satisfied that Vologeses was detained by a revolt in Hyrcania (to the east), replied by advising Tiridates to petition the emperor: since a stable kingdom and a bloodless reign might be his, if he renounced a dim and distant hope and pursued one within his immediate grasp.

Book XIII:XXXVIII Corbulo and Tiridates fail to meet

It was thus agreed, since passing messages to and from in turn was doing nothing to achieve peace, to designate a time and place where they could talk together. Tiridates announced that a guard of a thousand horsemen would accompany him: as to the size and composition of the force which might attend on Corbulo, he made no stipulation, so long as they came in the guise of peace, without breastplates and helmets.

Any ordinary mortal, much less an experienced and far-sighted general, could comprehend the barbarian’s tactic: and that the point of offering a restriction on his own numbers, while allowing the other an unlimited escort, was to prepare an act of treachery; since if unprotected soldiers were exposed to horsemen trained to the bow, numbers would prove irrelevant. Feigning unawareness of this, however, Corbulo replied that consultations of national import were better conducted in the presence of both armies, and chose a site, one part gently rolling hills suitable for ranks of infantry, the other extending to a plain allowing the deployment of cavalry.

First there, on the day chosen, Corbulo positioned the allied cohorts and the auxiliaries provided by the kings on the wings, and in the centre the Sixth legion, with three thousand men of the Third summoned from another camp by night, the solitary eagle appearing to denote a single legion’s strength only.

Day was already declining, when Tiridates took up position far off, where he was visible rather than audible. The Roman general therefore, without joining him, ordered his troops to return to their different camps.

Book XIII:XXXIX Corbulo reduces the Armenian fortresses

Tiridates, suspecting a ruse since our troops were moving off in several directions, or hoping to intercept the supplies reaching us via the Black Sea and the town of Trapezus (Trabzon, Turkey, historically Trebizond), departed in haste. Yet not only was he unable to use force against our supply trains, since they were led through mountain passes held by our posts, but Corbulo to avoid a fruitless campaign and at the same time force the Armenians onto the defensive, prepared to raze their fortresses.

The strongest in that district was known as Volandum, which he reserved for himself; leaving the smaller forts to the legate Cornelius Flaccus, and the camp-prefect Insteius Capito. Then after inspecting its defences and making appropriate provision for the assault, he exhorted his men to drive this nomadic enemy, ready for neither peace nor battle, but confessing its treachery and cowardice by flight, from its lair, and think of both glory and the spoils.

He then divided his force in four, leading one section massed in ‘tortoise’ formation to undermine the ramparts, another to move ladders against the walls, while ordering a strong party to launch burning brands and spears from the catapults. The slingers, both ‘libritores’ and ‘funditores’, were assigned a position from which to hurl their shot at long range lest, threatened on all sides, one point under pressure was relieved by reinforcements from another.

In the event, the men showed so much ardour in action, that before a third of the day had passed, the walls were cleared of defenders, the barricaded gateways shattered, the fortifications taken by escalade, and all the adult males within slaughtered, without the loss of one soldier, and with very few wounds incurred. The crowd of non-combatants were sold at auction, the rest of the spoils falling to the victors.

The legionary commander and the prefect had equal good fortune, and with three forts taken in a day the rest surrendered, from panic, or by the will of those inside. All this inspired confidence for an attack on the national capital Artaxata (Artashat). The legions were not led there by the shortest route, however, since the bridge over the Araxes (Aras), which runs beside the city walls, would have brought them within missile range: thus they crossed further away by a ford wider than the bridge.

Book XIII:XL Tiridates attacks, then retreats

Meanwhile Tiridates, torn between shame and fear, in that if he conceded the outcome of the siege he would appear powerless, while if he intervened he might find himself and his cavalry caught on impassable ground, finally decided to reveal his forces in line of battle and, given an opportunity, to begin the fight, or simulate flight in order to prepare a place for ambush.

His attack on the Roman column was therefore sudden, and from all quarters, but without surprising our commander, who had organised his troops for battle as well as the march. On the right were the Third legion, on the left the Sixth, and picked men of the Tenth in the centre; the baggage had been brought within the lines, and a thousand horse protected the rear, their instructions being to resist an enemy attack at close quarters, but not pursue if they retreated. Archers on foot were on the flanks with the rest of the cavalry, the left wing extending along the foothills, so that if the enemy forced their way through, they could be met simultaneously both in front and by an enveloping movement.

Tiridates, on the other hand, attacked in desultory fashion, never within javelin throw, but now threatening and now feigning panic, in hopes of disorganising the ranks and falling on them while scattered. Then since there was no breach due to rashness, and the example presented by a cavalry officer in his advancing too audaciously, and being transfixed by arrows, merely confirmed the discipline of the rest, Tiridates drew back at the coming of nightfall.

Book XIII:XLI Corbulo takes Artaxata

Laying out a camp on the spot, Corbulo considered whether to advance on Artaxata with unencumbered legions, by night, and lay siege to the city, into which he assumed Tiridates had retired. Later, when his scouts brought news that the king’s journey appeared to be a lengthy one, it being uncertain whether he was headed for Media or Caucasian Albania, Corbulo waited for dawn, but sent lightly-armed troops forward meanwhile to throw a cordon round the walls and start the attack from a distance.

However, the townspeople opened the gates of their own accord, and surrendered themselves and their property to the Romans, thereby securing their personal safety. Artaxata itself was set on fire, demolished, and razed to the ground, since it could not be held without a robust garrison, nor was our strength such that it could be divided between a strong garrison and the waging of a campaign, while if the town was left unscathed and unguarded the mere fact of its capture could be neither beneficial nor glorious.

In addition a portent appeared, as if sent by the powers above: for the whole landscape shone with sunlight as far as Artaxata, yet suddenly the area bounded by the fortifications was enveloped in dark cloud and distinguished by lightning, such that it was believed hostile gods were consigning it to its doom.

For this, Nero was hailed as Imperator, and thanksgivings were held by Senate decree, statues, and arches, and successive consulates were granted him, and the days on which victory was achieved, and announced, and on which the resolution concerning it was passed, were to rank as national festivals. More, in the same vein, was agreed, so utterly excessive that Gaius Cassius who had approved the other honours pointed out that if thanks were shown to the gods in accord with the benignity of fortune, a whole year would not suffice for thanksgiving, and therefore there ought to be a distinction drawn between sacred days and working days, ones on which the heavens could be worshipped without impeding human activity.

Book XIII:XLII Publius Suillius accused

Next, a defendant was convicted who had been hurled about by a variety of events and earned himself the hatred of many, though his conviction was not achieved without some loss of popularity on Seneca’s part. He was Publius Suillius, the terrible and venal favourite of Claudius’ reign, who was less diminished by the change of emperor than his enemies wished, and would rather be treated as a defendant than as a supplicant.

For the sake, it was believed, of crushing him, an earlier Senate decree had been revived, along with its penalties prescribed by the Cincian law against lawyers who pleaded cases for gain. Suillius abstained from neither complaints nor reproaches, with a freedom due not only to his fierce spirit but also his extreme age, attacking Seneca as an enemy to all friends of Claudius, the emperor under whom that Seneca had suffered a well-earned exile (in AD41).

At the same time, he exclaimed, since Seneca was accustomed only to insipid books and callow youths, he possessed a jaundiced eye for those who applied a vivid and genuine eloquence to the defence of their fellow-citizens. He himself had been Germanicus’ quaestor, Seneca an adulterer under that prince’s roof. Was it to be judged a graver offence to obtain a client’s gift for honourable service than to pollute the bed of an imperial princess (Julia Livilla).

By what manner of wisdom, what precepts of philosophy, had he acquired, in a mere four years of imperial favour, three million gold pieces? In Rome, the childless and their wills were caught in his net; Italy and the provinces were sucked dry by his boundless usury: while he, Suillius, possessed only his hard-earned and modest income. He would rather suffer charge, trial everything, than submit his ancient, homespun honour to this sudden success.

Book XIII:XLIII Suillius claims that he was simply obeying orders

There was no lack of hearers to report his words, unchanged or with changes for the worse, to Seneca. Accusers were found to charge Suillius with plundering our allies, during the time when he ran Asia Minor, and embezzling public funds. Then as the prosecution had sought a year’s delay to continue their enquiries, it seemed expedient to start on his crimes at home, witnesses to them being at hand.

They accused Suillius of the cruel indictment which drove Quintus Pomponius to the last resort of rebelling against the emperor (AD42); of hounding to death Drusus the Younger’s daughter Julia Livia (AD43) and Poppaea Sabina the Elder (AD47); the entrapment of Valerius Asiaticus (AD47), Lusius Saturninus, and Cornelius Lupus; and lastly the conviction of a host of Roman knights, with all the savagery of Claudius’ reign.

He, in his defence, claimed that none of his actions were undertaken of his own free will, but that he had merely obeyed the emperor’s orders, before Nero cut short his oration by stating that he knew from his father’s papers that Claudius had never compelled the bringing of a single prosecution. Then orders from Messalina were given as the excuse, and the defence gave way: why had no one else been chosen then, it was asked, to give voice to that shameless woman’s ravings? Punishment must fall on the perpetrators of such atrocities as these, who win the rewards of crime, then ascribe their crimes to others.

Therefore, after the seizure of part of his estate (his son and grand-daughter being granted the rest, after exempting the property they had received from their mother’s or their grandmother’s will) he was banished to the Balearic Islands. His spirit was broken neither by the trial nor his conviction; and it was said that a rich and pleasant way of life made his seclusion tolerable.

When his son, Nerullinus, was attacked by the accusers, who relied both on his father’s unpopularity and on charges of extortion, Nero interceded, on the grounds that the desire for vengeance had been fully satisfied.

Book XIII:XLIV The trial of Octavius Sagitta

At around the same time, Octavius Sagitta, a plebeian tribune, who was madly in love with a married woman named Pontia, first bribed her to commit adultery by means of substantial gifts, and then to desert her husband, for his own part promising to wed her, and gaining her agreement too. But once the woman had obtained her freedom, she contrived a delay, pleading that it was against her father’s wishes, and then broke her promise when a wealthier prospect appeared.

Octavius now remonstrated with her, now threatened her, claiming the ruin of his reputation, the exhaustion of his wealth, finally placing his life, all that was left to him, in her hands. Moreover, having been rejected, he demanded the consolation of a single night with her, as a solace to him thereafter. The night was set, and Pontia entrusted a maidservant in the know, with guarding the bedroom. Octavius, a dagger hidden beneath his clothing, now arrived accompanied by a freedman.

Now, as is usual in love, came angry words, entreaty, reproach, and reparation, a portion of the night being devoted to passion; inflamed by which, it seems, she still suspecting nothing, he pierced her with his weapon, scared away the maid who came running, by wounding her, and fled from the room. Next day the murder was revealed, and the assassin’s name not in doubt, since it was shown that he had been alone with the victim.

However, the freedman claimed the crime was his own, he had avenged the injury done his master. This account, as an instance of devotion, shook some, until the maidservant, recovered of her wound, revealed the truth. Brought before the consuls, after resigning the tribunate, by the victim’s father, Octavius was convicted by the Senate, and sentenced under the laws applying to murder and assassination.

Book XIII:XLV The rise of Poppaea Sabina

That year, a no less striking example of shameful behaviour proved to be the beginning of grave harm to the State. There was in Rome a daughter of Titus Ollius, named Poppaea Sabina the Younger after her maternal grandfather Poppaeus Sabinus, of illustrious memory, who with the honours of the consulate (AD9) and triumphal insignia (AD26) outshone her father Ollius who before ever achieving office was ruined by his friendship with Sejanus.

Poppaea was a woman possessed of every advantage except a virtuous character. Indeed her mother, who had eclipsed in beauty every woman of her day, endowed her equally with good looks and ambition, and her wealth matched the distinction of her birth. Her conversation was charming, her wit not wasted: she displayed modesty and practised lasciviousness, rarely appearing in public, and then with her face partly veiled in order not to satisfy the onlooker, or because it became her so.

She was never sparing of her reputation, drawing no distinction between husbands and lovers; a slave neither to her own moods or those of others, wherever advantage was revealed, there she directed her passion. Thus, while married to Rufrius Crispinus, a Roman knight by whom she had a son, she was attracted by Otho’s youth, excesses, and his reputed position as Nero’s most brilliant friend: nor was it long before her adultery ended in their marriage.

Book XIII:XLVI Mistress to Nero

Otho praised his wife’s beauty and elegance before Nero, either employing such terms of endearment incautiously, or perhaps to inflame the emperor’s desire, and thus through their sharing the same woman forge a powerful bond between them. He was frequently heard to say, as he rose from Nero’s table, that he at least must return to his wife, since to his lot had fallen an excellence and beauty which all longed for and only the fortunate enjoyed.

In view of these and similar incitements, no great delay intervened, before Poppaea, once admitted to Nero’s presence, gained an ascendancy, first by blandishments and cunning, pretending to be unequal to her passion, captivated by Nero’s looks; then, as the emperor’s love grew fiercer, turning to arrogance, and if detained for more than a night or two, insisting that she was a wife, and could not renounce her marriage, linked as she was to Otho by a way of life that none could equal: he being of splendid mind and culture, seen by that to be worthy of the highest fortune: while Nero, enthralled by a slut of a girl, habituated to an Acte, drew nothing that was not mean and abject from that slavish relationship.

Otho was barred from his usual intimacy with Nero, later from his audiences and his suite, and finally, lest he acted as a rival in Rome, he was appointed to Lusitania; where until the outbreak of civil conflict he lived not in the notorious style of the past, but honestly and virtuously, active in his amusements but temperate in his use of power.

Book XIII:XLVII Cornelius Sulla banished to Marseilles

From that time onwards, Nero no longer tried to conceal his debauchery or his crimes. He was acutely suspicious of Cornelius Sulla, mistaking his slowness of wit for cunning and deceit. This fear was deepened through the mendacity of Graptus, a freedman of the Caesars, whose age and experience had acquainted him with the households of the emperors from Tiberius onwards.

At that time the Mulvian bridge was famous for its night-life, and Nero frequented the area, to run wild more freely outside (two miles north of) the city. The story went that an ambush of the emperor had been intended, as he re-entered Rome via the Flaminian way, which by chance had been avoided, since he had returned, by another route, to the Gardens of Sallust; and that the author of the plot was Sulla. The foundation for the tale was that as some of the emperor’s servants were on their way home, they happened to be thrown into a baseless panic by some juvenile revels, instances of which occurred indiscriminately at that time.

None of Sulla’s servants or followers were seen to be involved, and his contemptible character, incapable of any kind of daring, was totally incompatible with the charge: yet just as though he had been found guilty, he was ordered to leave his homeland and incarcerate himself within the walls of Marseilles (Massilia).

Book XIII:XLVIII The situation in Puteoli (Pozzuoli) resolved

In the same consulate, two deputations from Puteoli (Pozzuoli) were granted an audience, sent separately to the Senate by the town council, and the populace, the former bemoaning the violence of the mob, the latter the avarice shown by the magistrates and leading citizens. Lest the sedition, which had progressed to stone-throwing and threats of arson, should lead to armed bloodshed, Gaius Cassius was entrusted with applying the remedy.

As his harshness was resisted, the task was transferred to the Scribonius brothers at his request. They were given a praetorian cohort, the fear of whom, plus a few executions, restored harmony to the town.

Book XIII:XLIX Thrasea justifies his approach

I would not have chosen to record here a commonplace Senate decree allowing the town of Syracuse to exceed the set numbers for gladiatorial shows, if Thrasea Paetus had not, by speaking against the proposal, presented his opponents with material for denouncing his approach. Why, they asked, if he thought the management of affairs showed a lack of senatorial freedom, did he pursue such trivia? Why not argue for or against matters of war and peace, finance, law, or whatever else was vital to the Roman State?

It was open to members, whenever they were allocated time to speak their piece, to express whatever views they wished, and demand a debate. Was the only bill worth amending that regarding the extent of public entertainment in Syracuse? Was everything else throughout the empire in such a state of perfection that it was as if Thrasea’s and not Nero’s hand was at the helm? If the greatest matters were allowed to pass in silence, how much greater the need to avoid irrelevancies.

Thrasea, on his friends requesting he give his reasons, answered by saying that it was not ignorance of the present state of affairs that made him seek to amend proposals of this nature, but that he was paying members a compliment, by showing that in turning their attention to the slightest of issues, neither would they be silent regarding matters of greater import.

Book XIII:L The question of indirect taxation

That same year (AD58), due to repeated public complaints denouncing the extortionate demands of the indirect-tax gatherers, Nero debated whether to order the abolition of all such duties and levies, and thereby grant the finest of gifts to the human race.

However, the senators, after first praising his generosity of spirit, restrained his initial impulse by pointing to a dissolution of the empire if the revenues that supported the State were reduced. If the customs duties, for example, were abolished, then surely demands for the abolition of direct taxation would follow. The companies of knights collecting the indirect taxes had largely been established by the consuls and plebeian tribunes when the independence of the Roman people was at its most vigorous; and subsequent provision had only been made to ensure a proper balance between income and essential expenditure.

Plainly though, they commented, the zeal of these indirect-tax collectors should be contained, or a system that had survived for so many years without objection might become distinctly unpopular through a newly-applied harshness.

Book XIII:LI Nero tightens the control of taxation

The emperor therefore issued an edict that individual tax regulations, previously kept secret, should be published in writing; that lapsed claims could not be revived after a year had passed; that in Rome the praetor, and in the provinces the propraetors or proconsuls, were to give priority to legal actions against indirect-tax collectors; and that soldiers were to retain their exemptions except as regards goods they themselves offered for sale. Other extremely fair rulings were included, which were observed briefly then evaded, though the abolition of the two, and two and a half, percent taxes, and whatever other specific illicit forms of extortion the indirect-tax gatherers had invented, is still in force.

The duties on transport of grain in the overseas provinces were reduced, and it was stipulated that a merchant’s cargo vessels were not to be included in the assessment of his assets or treated as taxable.

‘Emperor Nero’

Joos Gietleughen (Dutch, 1559)

The Rijksmuseum

Book XIII:LII The trials of Sulpicius Camerinus and Pompeius Silvanus

Two defendants, Sulpicius Camerinus and Pompeius Silvanus, from the province of North Africa, where they had held proconsular powers, were acquitted by Nero. Camerinus’ adversaries were a handful of private individuals, and the charges concerned acts of cruelty rather than financial malpractice. A strong force of accusers had laid siege to Silvanus, and were demanding time to summon their witnesses: but the accused insisted on defending himself at once. He prevailed, due to his wealth, age and childlessness, and outlived those whose intrigues he had escaped.

Book XIII:LIII Lucius Vetus proposes a Saône-Moselle canal

Quiet had prevailed in Germany, up to then, thanks to the nature of our generals there, who, triumphal insignia having become commonplace, anticipated greater honour from maintaining the peace.

The armies were commanded at that time (AD55) by Paulinus Pompeius (Upper Germany) and Lucius Vetus (Lower Germany). Not to allow idleness among the troops, however, Paulinus began completion of the Rhine embankments, begun sixty-seven years earlier (12BC) by Drusus the Elder: while Vetus prepared to connect the Saône (Arar) and Moselle by canal, so that goods shipped by sea, and then up the Rhone and Saône, could enter the Rhine via this canal, and reach the ocean; thus with the natural obstacles removed, there would be a navigable route between the shores of the western Mediterranean and the North Sea.

Jealous of the scheme, Aelius Gracilis, the governor of Belgica, discouraged Vetus from courting popularity in Gaul by marching his legions into a province outside his jurisdiction, saying it would arouse the emperor’s fears, the usual barrier to honest enterprise.

Book XIII:LIV Trouble with the Frisians

However, through prolonged inaction on the part of the armies, a rumour began that the legates had been denied authority to lead them against the enemy. Accordingly, the Frisians moved to the banks of the Rhine, the warriors by way of the forests and marshes, those unfit for war via the lakes (later the Zuyder Zee), where they settled in the clearings reserved for troops. The instigators were Verritus and Malorix, who ruled the tribe, to the extent that anyone does command a tribe in Germany.

They had already set up home, sown the fields, and were exploiting the soil of their new homeland, when Dubius Avitus, who had taken over the province (of Upper Germany) from Paulinus, coerced Verritus and Malorix into petitioning the emperor in Rome, threatening them with force unless they withdrew to their previous location or secured endorsement of the new settlement.

They departed for the capital, where, while awaiting an audience with Nero who was preoccupied with other matters, they visited, among the other sights shown to barbarians, the Theatre of Pompey, to view the vast numbers of people. There, to pass the time (not knowing enough to be amused by the performance), they were enquiring about the audience, the distinctions in rank, which were the knights, where was the Senate, when they noticed a few individuals in foreign garb among the senatorial seats.

On asking who those people were, and hearing that theirs was an honour granted to ambassadors from nations distinguished by their courage and friendship to Rome, they exclaimed that none excelled the Germans in arms or loyalty, made their way down and took their seats alongside the senators. It was taken in good part by the audience, as showing a primitive impetuosity and a generous spirit of rivalry.

Nero granted both of them Roman citizenship. The Frisians, however, he ordered to give up the land they had occupied. As they scorned to do so, compulsion was applied by the sudden despatch of auxiliary cavalry, who captured or killed those most obstinate in refusal.

Book XIII:LV Boiocalus addresses Avitus

The same ground was then occupied by the Ampsivarii, a tribe not only stronger in numbers, but bolstered by the sympathy shown them by their neighbours, since they had been driven out by the Chauci, and were a homeless people begging for a safe place of exile. Added to this was the support of one Boiocalus, an illustrious individual among the clans, and loyal to us also, who reminded Avitus that during the Cheruscan revolt he had been clapped in irons on Arminius’ orders, then had served under the leadership of Tiberius and Germanicus, and was now adding to his fifty years of allegiance to us by submitting his people to our rule.

Why, he asked, should such a large tract of ground lie there unused, so as to allow passage someday for the army’s flocks and herds? Let them, by all means, keep pasture for their animals to feed hungry men, but not to the extent of preferring a solitary wasteland to friendly nations! Once those fields belonged to the Chamavi, then the Tubantes, and after them the Usipi. As the skies had been granted to the gods, so had the earth to the human species; and what was unoccupied, was there to be shared.

Then raising his eyes to the sun, and invoking the other heavenly bodies, calling out to them as if he stood before them, he demanded if they too wished to gaze on empty lands: sooner let the sea pour out its waters, he cried, against these appropriators of the earth!

Book XIII:LVI Avitus rejects his pleas

Avitus, moved by this, replied that all must submit to the commands of their betters; it pleased the gods, whom they invoked, that the decision as to what to give and what to take away should lie with the Roman people, and that they should submit to no judges but themselves. This was his official response to the Ampsivarii, but he would grant land to Boiocalus himself, as a reminder of their friendship. Scorning this, as the reward for treason, the German added: ‘We may lack land to live in, but not to die in’: and they parted with hostile thoughts on both sides.

The Ampsivarii invited the Bructeri, the Tencteri, and tribes even more remote, to join them in war: Avitus wrote to Curtilius Mancia, then commander of the army of Upper Germany, requesting him to cross the Rhine and display his forces to the rear, while he himself led his legions into the territory of the Tencteri, threatening them with destruction unless they dissociated themselves from the cause.

They desisting, the same threat deterred the Bructeri; and since the other tribes also abandoned this foreign confrontation, the Ampsivarii, isolated, fell back on the Usipi and Tubantes. Driven from those territories also, they sought refuge with the Chatti, then the Cherusci, and after long wanderings, in which they were treated as guests, beggars, and then enemies, their young men died on alien soil, while those not of fighting age were portioned out as spoils.

Book XIII:LVII Tribal warfare and the Cologne fire

That same summer, a great battle was fought between the Hermunduri and the Chatti, trying to take by force a boundary river, and the rich salt-springs nearby. Besides their passion for settling everything by the sword, they held an innate belief that this area was dear to the heavens, and nowhere did the gods give closer ear to human prayer. So, with the gods’ indulgence, salt was not produced as it is in other lands by evaporation from pools left behind by the waves, but beside this river and in these forests by pouring the water over a pile of burning logs, the crystals forming from the fusion of those two elements, water and fire.

But this war favouring the Hermunduri, was disastrous to the Chatti, since both sides consecrated, if victorious, their adversaries to Mars (Tiu/Tyr) and Mercury (Odin/Woden/ Wotan); horses, men and all to be given to slaughter. The enemy threatening us thus turned upon itself. Nevertheless the township (Cologne) of our allies the Ubii, was afflicted with a sudden catastrophe. Devouring fires, beneath ground, took hold of farms, crops and villages, and swept towards the walls of the colony, founded not long before (50AD).

Nothing could extinguish the flames, rain nor running water nor liquid of any kind, till devoid of remedy and angered by the destruction a few countrymen threw stones at the fire from far away, then as the flames halted they drew closer, beating them down with sticks and other things, trying to scare them off as if they were wild creatures: finally tearing their clothes off and heaping them on the coals, which they were the more likely to smother the more worn and soiled by use the clothes happened to be.

Book XIII:LVIII The fig-tree, the Ruminalis, in the Comitium is renewed

By that same year (AD58), the tree in the Comitium sacred to Rumina (goddess of nursing mothers) which had sheltered the infants Romulus and Remus eight hundred and thirty years before, had reached such a stage of decrepitude, with its dead branches and withered trunk, that its state had been taken as a portent, until now, when it revived and showed fresh shoots.

End of the Annals Book XIII: XXXIV-LVIII