Cornelius Tacitus

The Annals

Book XIII: I-XXXIII - Nero and Agrippina

‘Nemesis, Retributive Justice’

History of Rome and the Roman people, from its origin to the establishment of the Christian empire - Victor Duruy (1811 - 1894) (p528, 1884)

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2017 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XIII:I The death of Julius Silanus.

- Book XIII:II Agrippina’s hold on power.

- Book XIII:III Nero’s eulogy on Claudius.

- Book XIII:IV Nero addresses the Senate.

- Book XIII:V A good start, but Agrippina still seeks supremacy.

- Book XIII:VI The Parthians expel Radamistus and ravage Armenia.

- Book XIII:VII Nero’s strategy, and good luck, avert the threat.

- Book XIII:VIII Corbulo and Quadratus compete for authority.

- Book XIII:IX Vologeses gives hostages.

- Book XIII:X Nero shows a welcome modesty.

- Book XIII:XI The emperor’s restraint continues.

- Book XIII:XII Agrippina’s hold over Nero weakens.

- Book XIII:XIII She begins to concede ground.

- Book XIII:XIV She challenges Nero directly.

- Book XIII:XV Nero moves against Britannicus.

- Book XIII:XVI Britannicus is poisoned.

- Book XIII:XVII His funeral pyre.

- Book XIII:XVIII Agrippina isolated by the emperor.

- Book XIII:XIX Agrippina is indicted.

- Book XIII:XX Nero contemplates murdering his mother.

- Book XIII:XXI Agrippina rebuts the charges.

- Book XIII:XXII Rewards and punishments.

- Book XIII:XXIII Pallas is banished.

- Book XIII:XXIV A purification of the city.

- Book XIII:XXV Nero roams the streets.

- Book XIII:XXVI The Senate debates the rights of freedmen.

- Book XIII:XXVII The emperor rules in favour of the status quo.

- Book XIII:XXVIII Conflicts of authority between the magistrates.

- Book XIII:XXIX The administration of the Senatorial treasury.

- Book XIII:XXX Four indictments, and an honourable passing.

- Book XIII:XXXI No great events, AD57.

- Book XIII:XXXII Regarding Pomponia Graecina.

- Book XIII:XXXIII Publius Celer, Cossutianus Capito, Epirus Marcellus indicted.

Book XIII:I The death of Julius Silanus

The first death under the new emperor, that of Julius Silanus, the proconsul for Asia Minor, was brought about by Agrippina’s guile, without Nero’s knowledge. It was hardly a case of Silanus provoking his end by any innate aggression, he being so lethargic, and so completely disdained by previous regimes that Caligula used to call him ‘the golden sheep’, but rather that Agrippina who had brought about the death of his brother Lucius, feared the possibility of revenge, since it was commonly thought that a man of mature years should take precedence over Nero, almost an adolescent still, and emperor only through crime, while Julius was of unstained reputation and noble lineage and, as was to be taken note of at such a time, also a descendant of the Caesars: since he too was the son of a great-granddaughter of Augustus.

Such was the motive for his execution: the instruments were Publius Celer, a Roman knight, and Helius, a freedman, who ran the emperor’s affairs in Asia Minor. They administered poison to Silanus at a dinner, too openly to avoid detection.

With no less haste, Claudius’ freedman Narcissus, whose quarrels with Agrippina I have already noted, was driven to suicide by harsh custody and extreme deprivation, though against Nero’s wishes, since his greed and prodigality were wonderfully in harmony with the emperor’s as yet hidden vices.

Book XIII:II Agrippina’s hold on power

He would have progressed to murder, had not Afranius Burrus and Seneca the Younger intervened. Both guardians to the imperial youth, and both in agreement, a rarity where power is shared, they influenced him equally by contrasting methods. Burrus, with his military interests and austere character, and Seneca, with his lessons in eloquence and kindly virtue, aided one another in ensuring that the emperor’s years of easy temptation would be kept, if he scorned moderation, within the bounds of acceptable pleasure.

Each faced the same opposition in Agrippina’s pride, who, burning with all the passion of ill-founded authority, possessed the allegiance of Pallas, at whose instigation Claudius had destroyed himself, through an incestuous marriage, and a fatal act of adoption. Yet equally, Nero’s character was not one of subservience, and Pallas, whose sullen arrogance exceeded the limits of a freedman, had attracted his loathing.

Nevertheless, in public, every honour was heaped upon Agrippina, and when the guards’ tribune asked for the password, in accordance with military routine, Nero replied: ‘The best of mothers’. The Senate too granted her a pair of lictors, and the office of priestess to Claudius, in the same session whereby he was voted a public funeral, followed by deification.

Book XIII:III Nero’s eulogy on Claudius

On the day of the funeral, Nero began his eulogy on Claudius, and while rehearsing the antiquity of that emperor’s family, the consulates and triumphs of his ancestors, he was taken seriously both by himself and others. Also his references to Claudius’ literary achievements and the absence of defeats abroad during that reign, were listened to respectfully. But when he referred to the deceased’s foresight and wisdom, no one could repress a smile, though the speech, composed by Seneca, showed the degree of refinement expected from a man whose pleasing ingenuity was so well-suited to the listeners of that age.

The elder statesmen, whose pastime always is to compare past and present, noted that Nero was the first of those who had held power to require a borrowed eloquence. For Julius Caesar, as dictator, had rivalled the greatest orators; and Augustus possessed the ready and fluent eloquence worthy of one who ruled. Tiberius too was skilled in the art, weighing his words, and powerful in his judgements, or deliberately ambiguous. Even Caligula’s troubled mind did not affect his power of speech. Nor did Claudius lack eloquence when he had prepared his thoughts. Nero, though, even as a child, immediately turned his lively mind to other things: composing, painting, singing, displaying his command of horses; and occasionally, in forging a set of verses, showing that he had in him the rudiments of learning.

Book XIII:IV Nero addresses the Senate

When all this pretence of grief was over, Nero entered the Senate House, and prefacing his speech with references to the senators’ authority, and the military consensus, talked of the advice and precedents he could draw upon in governing supremely well. Nor, he said, had his youth been filled with civil war or domestic strife; he brought to his task neither hatred, nor injury, nor desire for vengeance.

He then described the future form of his rule, those things to be especially shunned that had aroused recent dissatisfaction. He would not be the judge of every matter, with prosecutors and defendants shut in the same room, and the power of the few given full rein; to his inner circle bribery and intrigue would find no access; palace and State would be separate entities.

Let the Senate, he cried, retain its ancient rights, let Italy and the public provinces face the consuls’ tribunal before the consuls gave them access to the senators: while he himself would account for the interests of the armies entrusted to him.

Book XIII:V A good start, but Agrippina still seeks supremacy

Nor was adherence to this lacking, and many decisions were devolved to the Senate: for example, none were to sell their services in pleading a cause, neither for cash nor gifts; nor were quaestors designate obliged to mount a gladiatorial show. This latter point, though opposed by Agrippina, as a subversion of Claudius’ decree, was passed by the senators, who had been summoned specially to the palace so that she could position herself at a newly-added door to the rear concealed by a curtain, to hide her from view but not prevent her hearing.

Indeed, when an embassy from Armenia, was pleading the nation’s cause before Nero, she would have ascended the emperor’s tribunal and presided there alongside him, if Seneca had not advised him, while others stood stupefied in alarm, to descend and greet her. This guise of filial piety thus averted a scandal.

Book XIII:VI The Parthians expel Radamistus and ravage Armenia

At the end of that year, there were disturbing rumours that the Parthians had again erupted and were ravaging Armenia after driving out Radamistus who, often ruling that kingdom then fleeing, had once more deserted the field.

In Rome, with its appetite for gossip, the question therefore arose as to how an emperor who was barely seventeen could contain or repel such a threat. What safety lay in a youth ruled by a woman? Were battles also, the siege of cities, all the business of war, to be handled by his tutors, they asked.

Others maintained that things were better than if it were Claudius, weakened by age and idleness, who had been summoned to take on the efforts of a campaign, while complying with orders from his servants! Burrus and Seneca, however, were known for their experience of affairs; and was the emperor so lacking in years, when it was said that Pompey at eighteen (84BC) and Octavian (Augustus) at nineteen (44BC) had withstood civil war?

More was achieved by a ruler’s auspices and advice, than his sword and a strong right hand. If, unmoved by jealousies, he employed an outstanding general rather than one relying on bribery and court favour, it gave a strong indication as to whether the friends around him were honest or otherwise.

Book XIII:VII Nero’s strategy, and good luck, avert the threat

In this midst of all this gossip, Nero ordered that recruits from the neighbouring provinces were to be moved to reinforce the eastern legions, while the legions themselves were to be stationed closer to Armenia. At the same time the two veteran kings Herod Agrippa II, and Antiochus IV, with their forces, were to prepare to cross the Parthian borders, and two bridges were to be constructed over the Euphrates, while Lesser Armenia was entrusted to Aristobulus, and the district of Sophene to Sohaemus, both receiving the royal insignia.

Then, just at the right moment, a rival to Vologeses II, his son Vardanes appeared; and the Parthians, so as to postpone hostilities, abandoned Armenia.

Book XIII:VIII Corbulo and Quadratus compete for authority

In the Senate, however, the whole thing was glorified in speeches by those who proposed that there should be a public thanksgiving, and that on the day of thanksgiving the emperor should wear triumphal robes, enter Rome to an ovation, and be voted a statue of himself, the same size as that of Mars the Avenger and to be placed in the same temple.

Apart from the usual sycophancy, there was delight in the appointment of Domitius Corbulo to secure Armenia, a choice which seemed to open a path for the virtues. The forces in the east were divided accordingly, with half the auxiliaries and two legions remaining in the province of Syria under its governor Ummidius Quadratus, while Corbulo was assigned an equal number of allies and Roman citizens, with the addition of the auxiliary cohorts and cavalry wintering in Cappadocia.

The allied kings were to take orders from either, according to the requirements of war: but they were more eager to support Corbulo, who to confirm his reputation, which is valuable at the start of a campaign, travelled swiftly, and met with Quadratus at the Cilician town of Aegeae (Yumurtalik, Turkey). Quadratus had travelled there, for fear that once Corbulo had assumed command of the forces in Syria allocated to him, all eyes would be turned towards this massive and grandiloquent general, noted for his experience and judgement as much as his vain splendour.

Book XIII:IX Vologeses gives hostages

However each of them advised King Vologeses to choose peace rather than war, and by giving hostages preserve that respect towards the Roman people customary among his predecessors. Vologeses handed over the most illustrious members of the Arsacian house, either to prepare for war when he wished, or remove his suspected rivals in the guise of granting hostages.

They were received by the centurion Insteius, Quadratus’ envoy, who chanced to be with the king on prior business. Once Corbulo had news of this, he ordered Arrius Varius, a cohort prefect, to go and take charge of the hostages.

A quarrel then started between prefect and centurion who, so as not to provide a spectacle for foreigners, left the decision to the hostages and the envoys escorting them. They chose Corbulo, on the strength of his recent successes and of that liking for him shown even by his enemies. Discord between the generals ensued; Quadratus complaining that he had been robbed of the fruits of his policy, Corbulo asserting that, on the contrary, the king had not been prepared to offer hostages until he himself was appointed as commander in the field, the king’s ambition then giving way to fear.

Nero, in order to resolve their differences, ordered a proclamation to this effect: in view of the successes obtained by Quadratus and Corbulo, laurels were to be added to the imperial rods and axes (fasces).

All this I have related together, although the series of events extended into the following consulate.

Book XIII:X Nero shows a welcome modesty

That same year, Nero asked the Senate for a statue to his father Gnaeus Domitius, and consular insignia for Asconius Labeo, who had acted as his guardian; but vetoed the offer of statues of himself, in solid-gold or silver.

And though the senators had decreed that the new year should begin in December, the month in which Nero had been born, he retained the first of January as the opening day of the year, out of respect for its old religious associations.

Nor was prosecution of Carrinas Celer allowed, the senator being accused by a slave, nor that of Julius Densus of the equestrian order, whose support for Britannicus was claimed as a crime.

‘Roman Emperor (likely Nero)’

Anonymous, c. 1750 - c. 1830

The Rijksmuseum

Book XIII:XI The emperor’s restraint continues

In the consulate of Nero and Lucius Antistius, when the magistrates were swearing loyalty to the acts of empire, he restrained his colleague Antistius from swearing loyalty to those performed by himself: and was applauded warmly by the senators, who hoped that his young mind, elevated by the glory attached even to small things, might aspire to greater ones.

Indeed a display of leniency towards Plautius Lateranus followed, who was now restored to the ranks of the Senate, having been demoted for adultery with Messalina. Nero, in fact, pledged himself to clemency, in a series of speeches which Seneca kept offering to the public via the emperor’s lips, either in order to teach virtue, or to advertise his skill.

Book XIII:XII Agrippina’s hold over Nero weakens

As far as other matters were concerned, Agrippina’s maternal authority had somewhat weakened, Nero lapsing into a love affair with a freedwoman named Acte, and at the same time taking into his confidence two handsome young men, Marcus Otho (the future emperor) and Claudius Senecio; the former being of consular family, the latter the son of an imperial freedman.

Without his mother’s knowledge, then despite her ineffectual objections, they had insinuated themselves into his household, through sharing both his dissipation and his dubious secrets, while even the emperor’s older friends were not against the girl gratifying his desires without harming anyone, since he loathed his wife Octavia, despite her nobility and known virtue, either it being so fated, or because what is illicit proves stronger, while there was always the fear that if his passions were thwarted, he might take to despoiling women of higher rank.

Book XIII:XIII She begins to concede ground

But Agrippina complained bitterly, as is a woman’s way, against ‘her rival the freedwoman’, ‘her daughter-in-law the serving wench’ with more in the same vein. She refused to wait for her son’s repentance or satiety, and the viler her reproaches the more she fanned the flames until, conquered by the force of his love, Nero relinquished his obedience to his mother, and placed himself in the hands of Seneca, whose close friend, Annaeus Serenus, feigning a love affair with the same freedwoman, screened the emperor’s adolescent desires, and used his own name so freely, that the gifts conferred on the girl by Nero in private were openly attributed to Serenus.

Agrippina now reversed her approach, attacking her son with blandishments, offering her bedroom and its privacy to hide what his dawning manhood and high estate demanded. Indeed she even confessed her ill-timed severity, and offered to transfer to him her own wealth, which was not much less than the emperor’s riches, a change as intemperate in its humility, as the excessive harshness with which she had lately repressed him. This reversal was not lost on Nero, and struck fear into his intimates, who begged him to beware the machinations of a woman always ruthless, and now deceitful towards him also.

About this time, it chanced that Nero, on inspecting some glittering apparel which had once adorned the wives and mothers of the imperial house, chose a dress and some jewellery and sent them to his mother as a gift. There was no question of frugality in the action, since he was conferring on her extremely valuable items previously coveted by others. But Agrippina proclaimed that the move was designed less to enrich her wardrobe than to deprive her of the rest, and that her son was dividing property that he owned solely because of her.

Book XIII:XIV She challenges Nero directly

There was no lack of those who ascribed worse to her. And Nero, inimical to anyone who supported such female arrogance, removed Pallas from the role to which Claudius had appointed him, and in which he virtually controlled the government. It was said, that as he departed, with his vast multitude of followers, the emperor remarked, not inappropriately, that Pallas was off to swear the formal oath on exiting office (thereby stating that he had done nothing illegal), and indeed Pallas had stipulated that there should be no enquiry into his past actions, and that his accounts with the State balanced perfectly.

Agrippina now turned precipitously to threats and alarms, nor were the emperor’s ears spared her testimony that Britannicus was now of age, the true and worthy successor to his father’s powers, which he, a spurious adopted heir, was now exercising through his mother’s wrongdoing. She had no objection to all the evils of that unhappy house being revealed, starting with her marriage, and her use of poison: the only act of foresight on her part and the gods, being that her stepson still lived. She would go with Britannicus to the guards camp: there let the daughter of Germanicus be heard on the one side, and on the other Burrus the maimed, and Seneca the exiled, claiming no doubt, with twisted hand and schoolmaster’s tongue, lordship over the human race.

At that moment she raised her arm, and heaping reproaches on him, invoked the deified Claudius, the shades of the brothers Silanus, and all the many pointless crimes.

Book XIII:XV Nero moves against Britannicus

Startled by all this, and with the day nearing on which Britannicus completed his fourteenth year and hence came of age, Nero began to brood, now on his mother’s violent moods, now on his rival’s character, lately revealed by a trivial test, which nevertheless gained the lad wide sympathy. During the drunken days of the Saturnalia, when among other diversions his contemporaries were drawing lots as to who should be their king, chance favoured Nero. He commanded various actions of the rest, intending to spare them embarrassment, but on ordering Britannicus to stand, walk to the centre, and recite something, hoping by this to make a laughing stock of a boy who knew nothing of sober, never mind drunken, entertainment, his victim steadfastly began a poem in which he hinted at his eviction from his father’s house and from the heights of power. This awoke feelings of compassion, all the more manifest in that night and revelry had banished dissimulation.

Nero, aware of ill-will, redoubled his hatred; and faced with Agrippina’s urgent threats, but not openly daring to order his brother’s execution, there being no grounds for criminal charges, he moved secretly, ordering poison to be prepared. His agent in this was Julius Pollio, tribune of a praetorian cohort, to whose charge was committed the convicted poisoner Locusta, notorious for her wickedness.

Now, that no one close to Britannicus gave a thought to right or loyalty, had long been provided for, and the first dose of poison he received was administered by his own tutors, but his bowels being opened he excreted the potion, which was either not powerful enough or had been diluted to prevent immediate action. Nero, however, unable to endure any tardiness in the execution of crime, threatened the tribune and the sorceress with execution, on the grounds that, too mindful of their reputation and already preparing their defence, they were creating obstacles to his safety. Promising, then, that death would be as instantaneous as if effected by the blade, they concocted the venom next to Nero’s bedroom, guaranteeing its potency by prior tests.

Book XIII:XVI Britannicus is poisoned

It was the custom for the emperor’s children to be seated, with other noble offspring of the same age, in sight of their relations, at a more scantily furnished table. There Britannicus dined, and since his food and drink was first tasted by one of his attendants, the following deceit was used, to avoid altering the procedure, or revealing the plot in killing both.

A harmless hot drink, previously tasted, was handed to Britannicus, and when he rejected it as still over-warm, cold water was added containing the poison. It thus pervaded his whole body, so that his voice and his ability to breathe failed him simultaneously. Those seated around him were startled, and the more unwise began to disperse: but those with a deeper understanding sat motionless gazing at Nero. He, reclining, and as if unknowing, observed that this was a not unfamiliar event due to the epilepsy with which Britannicus had been afflicted from infancy, and that consciousness and feeling would presently return.

But from Agrippina came such a shudder, provoked by terror and mental anguish, despite her usual ability to control her features, that it was obvious she had been as ignorant of the plot as was Britannicus’ sister Octavia, and now realised that indeed all hope was lost, and the precedent had been set for her own murder. Octavia, though young and inexperienced, hid her grief, her concern, her every emotion. So, after a brief silence, the pleasures of the feast were resumed.

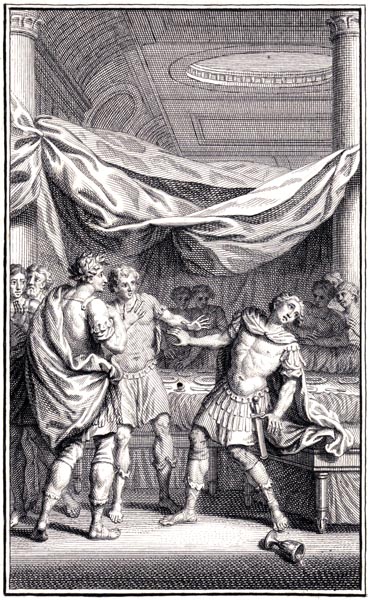

‘The Death of Britannicus’

Pieter Tanjé, after Louis Fabritius Dubourg, 1743

The Rijksmuseum

Book XIII:XVII His funeral pyre

The one night saw both Britannicus’ murder and his funeral, the pyre and its trappings, modest as they were, having been prepared in advance. Yet his ashes were interred in the Mausoleum of Augustus, on the Field of Mars, though in such a downpour of rain the crowd believed it portended the anger of the heavens against a crime which has again and again been condoned by the majority when taking into account the age-old discord between brothers, and its incompatibility with autocratic rule.

Many authors of the period claim that, on a series of days prior to the murder, Nero had so abused Britannicus’ innocence that his death might no longer be seen as too cruel, or arriving too soon, even though it took place amongst the sanctities of the table without his being granted time even to embrace his sister and before his enemy’s eyes, by its coming so swiftly to this last scion of the Claudian House, since he had been defiled by lust before the poison.

The hastiness of the funeral was defended in a decree of the emperor, claiming that it was a tradition among our ancestors to remove untimely obsequies from the public gaze, and not detain it with eulogies and processions. Moreover, having lost the help of his brother, all remaining hope rested on the State, and the Senate and people themselves must cherish their emperor the more, as he was in fact the sole survivor of a house (the Claudian) fashioned for the heights of power.

Book XIII:XVIII Agrippina isolated by the emperor

He now showered gifts on the most important of his friends. Nor were men lacking to condemn those who, though professing austerity at the time, divided up houses and villas like so much plunder. Others however believed that they had been compelled to do so by the emperor, conscious of his crime but hopeful of forgiveness, so that by his generosity he could place the most powerful men under an obligation.

However, no show of munificence could assuage his mother’s anger. She took Octavia to her heart, held endless private conversations with her friends, while, with more than her inborn greed, she appropriated money from every source as a reserve. She welcomed tribunes and centurions courteously, and showed a respect for the titles and virtues of the nobility, of whom some indeed still survived, as if in search of a faction and a leader.

This was known to Nero, and he withdrew the military guard which she had acquired as an emperor’s wife and had retained as the present emperor’s mother, as well as the German bodyguards lately assigned to her as a similar mark of honour. He created his own household, and lest her gatherings might draw a crowd, he installed his mother in the house that had belonged to Antonia the Younger, and when he visited her there arrived with a throng of centurions, and left after a perfunctory kiss.

Book XIII:XIX Agrippina is indicted

Nothing in human affairs is as fickle and mutable as fame attached to a power not supported by its own strength. Agrippina’s threshold was instantly avoided: no condolences, no visits except from a very few women, from love or perhaps hatred. Among these was Junia Silana, driven from her husband Silanus by Messalina, as I have related.

Noted for her ancestry, beauty and lasciviousness, and long Agrippina’s most dear friend, she was later involved in a private quarrel between them, since Agrippina had dissuaded the young nobleman Sextius Africanus from marrying Silana, describing her as a loose woman of uncertain age, not with the intention of winning him for herself, but to keep the rich and childless Silana from gaining a husband. She, in hopes of wreaking revenge, procured two of her own followers, Iturius and Calvisius, to bring charges against Agrippina, not by employing the old often-heard tale of the latter being in mourning for Britannicus, or of broadcasting the wrongs done against Octavia, but claiming that she was resolved to encourage Rubellius Plautus to foment rebellion, he being equally descended, with Nero, from the divine Augustus (as his great-great-grandson) on the mother’s side. As Plautus’ wife and then empress she would once more enter into power.

The charges were communicated to Atimetus, a freedman of Nero’s aunt Domitia, by Iturius and Calvisius. Delighted by what had been disclosed (since the rivalry between Agrippina and Domitia was fierce) Atimetus urged the actor Paris, also a freedman of Domitia, to go instantly and present the charge to Nero in the most brutal manner possible.

Book XIII:XX Nero contemplates murdering his mother

The night was well-advanced, and Nero was spending it over his wine, when Paris, who was accustomed usually to bring some life to the emperor’s debauchery, but now feigned melancholy, entered the room, and revealing the evidence in detail so terrified his listener, that Nero not only determined to kill his mother together with Plautus, but even to remove Burrus from his command, on the grounds that his promotion had been furthered by Agrippina and Burrus was repaying the debt.

According to Fabius Rusticus, the letter to Caecina Tuscus, ordering him to take over command of the praetorian cohorts had been written, but the role remained with Burrus thanks to Seneca’s intervention. Pliny and Cluvius Rufus do say that Nero never doubted the prefect’s loyalty; and indeed Fabius Rusticus is inclined to overpraise Seneca, through whose friendship he flourished. For my part, when the historians agree, I will follow them, where they disagree I will record the various versions against their respective names.

In a state of trepidation, and desirous of his mother’s death, Nero would brook no delay, until Burrus, promising she should indeed die if her guilt could be conclusively proven, said that anyone, especially a parent, was permitted a defence; and there were no accusers present, only a lone voice, here from the house of an enemy. Let the emperor consider the darkness, a night spent wakefully in feasting, all that was conducive to rash and foolish action.

Book XIII:XXI Agrippina rebuts the charges

The emperor’s fears having been calmed in this manner, a visit was paid at daybreak to Agrippina, so that she might hear the charges and either rebut them or pay the penalty, the task being undertaken by Burrus, with Seneca present; while a number of freedmen attended to bear witness to the conversation.

After expounding all the accusations and their various sources, Burrus adopted a threatening attitude. Agrippina however summoned all her arrogance, saying: ‘It is no surprise that Silana, who has never given birth, is ignorant of maternal affection; parents do not change their children as an adulteress changes lovers. Nor, if Iturius and Calvisius, having exhausted their estates, pay for an ageing mistress with this latest effort, by inventing charges, is that a justification for my sad reputation, or the emperor’s conscience, being tainted with parricide.

As for Domitia, I should be grateful for her enmity if, instead of now staging this theatrical scenario with the help of her bedfellow Atimetus and her actor Paris, she were competing with me in benevolence towards my Nero. While my advice was preparing the way for his adoption, his proconsular powers, his designation as consul, and his other steps to power, she was beautifying the fishponds at her beloved Baiae!

Who can stand forth and accuse me of tampering with the guards in the city, or shaking the loyalty of the provinces, or finally of seducing slaves or freedmen to crime? Could I have lived happily with Britannicus as master of all? And even if Plautus or some other were to sit in judgement over the State, would there not still, without doubt, be plenty of accusers ready to charge me, not with some odd impatient utterance of unguarded affection but with that crime from which only a son could absolve me?’

Those present were moved, and moreover tried to assuage her feelings, but she insisted on an audience with her son; where she spoke neither of her innocence, as if unsure of him, nor of her past services to him, as if in reproach, but by way of winning vengeance for herself and recognition for her friends.

Book XIII:XXII Rewards and punishments

As a result, Faenius Rufus was made custodian of the corn-supply, Arruntius Stella supervisor of the Games to be given by Nero, and Tiberius Balbillus governor of Egypt. Syria was destined for Publius Anteius, but through various subterfuges it eluded him, and ultimately he was kept in Rome.

Silana, on the other hand, was driven into exile; Calvisius and Iturius were also relegated; Atimetus received the death penalty; while Paris was too vital to the emperor’s debaucheries for any punishment to be inflicted. Plautus was, for the moment, passed over in silence.

Book XIII:XXIII Pallas is banished

It was then reported that Pallas and Burrus had agreed to summon Cornelius Sulla to power, on the strength of his illustrious ancestry and his relationship to Claudius, whose son-in-law he had become by marrying Antonia.

The accusation was brought by one Paetus, notorious for supervising the treasury’s sales by auction, and now convicted of lying. But Pallas’ insolence caused offence more than his innocence of the charge gave pleasure: since on the freedmen being named, on whose complicity he was alleged to have relied, he replied (mere names not being evidence) that he never indicated anything under his own roof except by a nod or a gesture, or if more was needed, wrote a note to avoid speaking.

Burrus however, though a defendant, gave the verdict amongst the judges. Pallas was sentenced to banishment and the account books, with which he was resurrecting cancelled debts owing to the treasury, were burned.

Book XIII:XXIV A purification of the city

At the end of the year, the guards usually present at the Games were withdrawn, to give a greater appearance of liberty, to prevent the men being corrupted by close contact with the theatre’s licentiousness, and to see if the masses would behave if the soldiers were removed.

A purification of the city was performed by the emperor, as advised by the soothsayers, after the temples of Jove and Minerva were struck by lightning.

Book XIII:XXV Nero roams the streets

The consulate of Quintus Volusius and Publius Scipio (56AD) was a time of peace, but with shameful excess at home, where Nero, disguised in slave’s dress, roamed the streets, whorehouses, and inns with his gang of friends, snatching goods for sale, and assaulting those they met, the victims so unaware of his identity that he received blows with the rest, and bore the marks on his face.

Then, when it became known that the emperor was the perpetrator, outrages against men and women of note increased, and others, taking advantage of the licence now permitted, began to carry out the same in their own gangs, in Nero’s name and with impunity. Julius Montanus, a member of the senatorial order, though he had not yet held office, who on meeting the emperor by chance in the dark repelled the violence offered then, recognising him, begged pardon but as if in reproach, was driven to suicide.

However, Nero, less venturesome in future, surrounded himself with soldiers and groups of gladiators, who were to hold back at first from quarrels of a modest almost private extent, but use their weapons if there was too great a show of energy by the injured party.

He even turned the players’ licence and their factions in the audience into something akin to warfare, waiving penalties and offering prizes himself, while looking on secretly or openly until, with the masses in conflict and for fear of worse commotions, no other remedy could be found but to expel all the actors from Italy, and station soldiers at the theatres again.

Book XIII:XXVI The Senate debates the rights of freedmen

At about that time, the Senate debated the offences committed by freedmen, and the demand made that, in unsatisfactory cases, former owners should have the right to revoke an act of emancipation. There was no lack of support for this, but the consuls did not dare to put the motion without the emperor’s knowledge, though they wrote to him that the Senate were in agreement.

Nero was doubtful whether he could sponsor the measure, his few advisors being of conflicting opinions: some complained indignantly that insolence had flourished with liberty, that patrons no longer possessed the same rights in law as the freedmen, who strained their patrons’ patience, and even raised their hands to strike them with impunity, or if they were punished it was in a manner suggested by themselves!

What redress was open to an injured patron, except to banish his freedman beyond the hundredth milestone, which merely meant to the beaches of Campania? But beyond that, the courts were open and equal to all: and some measure impossible to ignore should be enacted. It should be no great trouble for a freedman to retain his liberty by practising the same obedience that had earned it: but those convicted of wrongdoing should be returned to slavery, so that fear might encourage those whom kindness had not altered.

Book XIII:XXVII The emperor rules in favour of the status quo

Against this, it was maintained that the guilt of the few should only affect themselves, the rights of the many ought not to be diminished. Freedmen formed a group from which the tribes, the magistrate’s staff, the priests, and even the city watch were largely recruited, while most of the knights and senators owned to no other origin: if the freedmen were divided off, the lack of free-born would be more than apparent!

It was not without reason, that our ancestors, in creating the various classes, made freedmen a communal asset. Indeed, two forms of manumission (formal and complete, or informal and incomplete) had been instituted, so as to leave room for a change of heart or renewed favour. Those who had not been liberated ‘by the rod’, were in some manner still held by the bond of slavery. All must judge on the merits of the case, and be slow to concede what could not be retrieved.

This latter view prevailed, and Nero wrote to the Senate that they must consider each freedman’s case individually, where their patron had brought the accusation: nothing generally applying should be amended. Not long afterwards, Domitia, his aunt, had her freedman Paris taken from her, as if by civil law and much to the emperor’s discredit, by whose command a ruling of noble birth had been obtained.

Book XIII:XXVIII Conflicts of authority between the magistrates

Nevertheless some shadow of the republic still remained. For a quarrel arose between the praetor Vibullius and the plebeian tribune Antistius, who had ordered the release of some disorderly members of the theatre factions, who had been clapped in irons by the praetor. The senators approved the arrest, and censured the liberty taken by Antistius.

At the same time the tribunes were forbidden from pre-empting praetorian and consular jurisdiction by summoning people from any area of Italian when civil action against them was already pending there. Lucius Piso, the consul designate, added a proposal that their powers should not be exercised under their own roofs, nor were the many fines they imposed to be entered in the treasury accounts by the quaestors until four moths had passed; in the meantime appeals were to be allowed, the decision lying with the consuls.

The powers of the aediles were also narrowed, and limits set on the amounts up to which the curule or plebeian aediles could seize assets pledged as security, or impose fines. And the plebeian tribune Helvidius Priscus brought a private action against the treasury quaestor Obultronius Sabinus, arguing that he was going to merciless lengths in his use of auction sales against the impoverished. The emperor then transferred responsibility for the public accounts from the quaestors to the prefects.

Book XIII:XXIX The administration of the Senatorial treasury

Authority over the Senatorial treasury had been in various hands, often altering. Augustus left the choice of prefects to the Senate; then as bribery for votes was suspected, they were drawn by lot from among the praetors. This was short-lived too, as the lots often fell upon those unequal to the task.

Claudius then reinstated the quaestors (as in the Republic) and promised them immediate promotion to higher rank: but as this was their first magistrate’s appointment they lacked the necessary years of experience: Nero therefore chose ex-praetors with a proven track-record.

Book XIII:XXX Four indictments, and an honourable passing

In that same consulate (AD56), Vipsanius Laenas was convicted, in his province of Sardinia, of financial corruption. Cestius Proculus, on the other hand, was acquitted on a charge of extortion brought by the Cretans.

Clodius Quirinalis who, in command of the oarsmen stationed at Ravenna, had troubled Italy with his savagery and debauchery, as though Italy were the least of nations, pre-empted his execution by taking poison. And Caninius Rebilus, who ranked amongst the most illustrious for his legal knowledge and the magnitude of his fortune, escaped the torments of sickness and old-age, by opening his veins, though due to the un-masculine vices for which he was notorious he had been thought incapable of the willpower required to commit suicide.

However, Lucius Volusius departed this life, his illustrious reputation intact, after enjoying ninety-three years of life, a notable fortune virtuously gained, and the unbroken friendship of a succession of emperors.

Book XIII:XXXI No great events, AD57

In Nero’s second consulate, Lucius Piso being his colleague, little occurred worthy of note, unless one wished to fill a volume by celebrating the foundations of, and beams with which, the emperor built his vast wooden amphitheatre on the Field of Mars, though it has been found more in accord with the dignity of the Roman people to entrust great events to the histories, and such things as those to the daily papers.

As for other matters, the colonies of Capua and Nuceria (Nocera Inferiore, Campania) were reinforced by the addition of veterans, and the populace given a grant of four gold pieces per head.

Also four hundred thousand gold pieces were paid into the treasury to support public credit, while the tax of four per cent levied on the purchase of slaves was remitted, though more in appearance than fact since, being required now to fall on the vendor, the buyer found it merely inflated the price.

Nero issued an edict, too, to the effect that no magistrate or procurator should mount a gladiatorial or wild-beast show, or any other entertainment, in the province they administered. For prior to this, their subjects were no less oppressed by their largesse, than by their financial greed, since they were merely masking their corrupt practices by courting favour with the crowd.

Book XIII:XXXII Regarding Pomponia Graecina

A Senate decree was also passed, both precautionary and punitive, whereby if a man was killed by his own slaves, those of his household granted freedom under his last will and testament should still suffer the same punishment as a slave.

The consular Lurius Varus, sentenced long before on extortion charges, was restored to his rank. And Pomponia Graecina, a woman of illustrious family, married to that Aulus Plautius whose ovation following the British campaign I recorded elsewhere, being charged with following alien rites, was left to her husband’s jurisdiction. He, following ancient custom, held the enquiry into his wife’s life and reputation before a family council, and pronounced her innocent.

Pomponia was destined to live many years, and experience continual sorrow. For after Julia Livia, daughter of Drusus the Younger, had been executed (AD43) as a result of Messalina’s treachery, Pomponia survived forty years dressed only in mourning and so saddened in spirit that her constancy to Julia’s memory, which went unpunished in Claudius’ time, later became her title to glory.

Book XIII:XXXIII Publius Celer, Cossutianus Capito, Epirus Marcellus indicted

That same year, saw many indictments, one being of Publius Celer, by the province of Asia Minor, which Nero could not forgive so delayed the case until the defendant died of old age; though Celer’s murder of the proconsul Julius Silanus (AD54), which I have recorded, was a great enough crime to eclipse all his other wrongdoings.

Also, the foul and hideous Cossutianus Capito was indicted, a man who thought that the same audacious authority he exerted in Rome should apply in the provinces but, defeated by his accusers’ tenacity, ultimately waived his defence and was convicted under the law of extortion.

However, lobbying on behalf of Epirus Marcellus, from whom the Lycians were claiming reparation, was so effective that various of his accusers were punished with exile, for endangering an innocent man.

End of the Annals Book XIII: I-XXXIII