Cornelius Tacitus

The Annals

Book XII: XLI-LXIX - The murder of Claudius

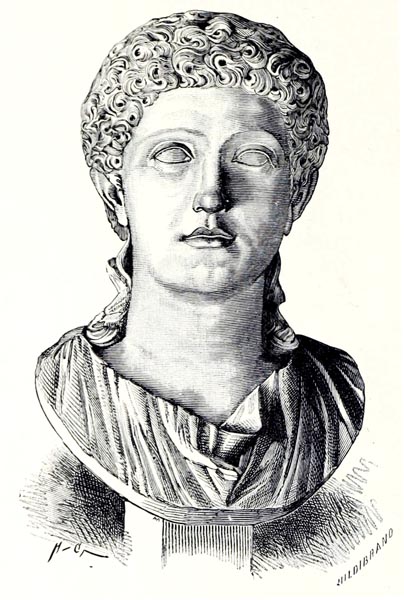

‘Isis’

History of Rome and the Roman people, from its origin to the establishment of the Christian empire - Victor Duruy (1811 - 1894) (p670, 1884)

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2017 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XII:XLI Friction between Nero and Britannicus.

- Book XII:XLII Agrippina extends her influence.

- Book XII:XLIII Problems with the corn supply.

- Book XII:XLIV Trouble looms in Armenia.

- Book XII:XLV Radamistus invades Armenia.

- Book XII:XLVI Pollio is bribed to pressurise Mithridates into a treaty.

- Book XII:XLVII Mithridates betrayed.

- Book XII:XLVIII Quadratus reviews the situation.

- Book XII:XLIX Julius Paelignus confuses the issue.

- Book XII:L Vologeses attacks Armenia, Radamistus occupies the country.

- Book XII:LI Radamistus escapes, his wife Zenobia survives.

- Book XII:LII The death of Furius Scribonianus.

- Book XII:LIII Pallas rewarded.

- Book XII:LIV The activities of his brother Felix in Judaea.

- Book XII:LV Trouble in Cilicia.

- Book XII:LVI The draining of Lake Fucinus (Lago di Celano)

- Book XII:LVII The partial failure of the scheme.

- Book XII:LVIII Nero marries and exerts his influence.

- Book XII:LIX The death of Statilius Taurus.

- Book XII:LX Claudius devolves powers to his procurators.

- Book XII:LXI Claudius grants the island of Cos exemption from tribute.

- Book XII:LXII An embassy from the Byzantines.

- Book XII:LXIII The history of Byzantium..

- Book XII:LXIV Ominous portents.

- Book XII:LXV Domitia Lepida the Younger condemned to death.

- Book XII:LXVI Agrippina obtains poison.

- Book XII:LXVII Xenophon completes the murder of Claudius.

- Book XII:LXVIII Agrippina detains Britannicus and his sisters.

- Book XII:LXIX Nero is hailed by the guards’ camp.

Book XII:XLI Friction between Nero and Britannicus

Claudius being consul for the fifth time, along with Servius Cornelius Orfitus, the toga of manhood was conferred on Nero despite his age (thirteen, not fourteen as required), so that he would appear ready for public office. Claudius yielded with pleasure to the senators’ sycophancy, by which they decreed that Nero assume the consulate when he reached the age of twenty and that, meanwhile, as consul designate, he should exert proconsular authority outside the capital, and be titled Prince of Youth (as Claudius’ nominated successor). A gratuity to the army and a gift of food to the populace were added, in his name.

At the games in the Circus, mounted to gain him favour with the masses, Nero now rode past in triumphal dress, Britannicus in the purple-bordered juvenile toga, so that the crowd might view the former in the robes of imperial power, the latter in a boy’s robes, and anticipate the fortunes of each. Simultaneously, those centurions and tribunes showing sympathy for Britannicus’ fate were removed, some for wholly fictitious reasons, others in the guise of promotion.

Even those freedmen with unbroken loyalty to him were dismissed, on the following pretext: that during an encounter between the two boys Nero greeted Britannicus by his given name, but the latter saluted Nero as ‘Domitius’. Agrippina reported the incident to her husband with loud complaints, as a first sign of discord: saying that Nero’s adoption had been put to scorn, the Senate decree and the people’s will rendered void, and in his own household; and that unless the perverse and hostile influence of Britannicus’ tutors was removed, public catastrophe would ensue.

Troubled by these near accusations, Claudius imposed death or exile on the best of his son’s teachers, and handed him over to the guardians appointed by his stepmother.

Book XII:XLII Agrippina extends her influence

Agrippina, however, did not dare to wield supreme power until she could obtain the removal of Lusius Geta and Rufrius Crispinus from command of the praetorian guard, believing them loyal to Messalina’s memory and her children’s cause. Therefore asserting to her husband that their rivalry was dividing the men, and that under a single head discipline would be stricter, she persuaded him to transfer command to Afranius Burrus, of the highest military reputation, yet aware to whose favour he owed his new rank.

To promote a greater awareness of her own dignity, Agrippina also began entering the Capitol in an ornate carriage, which honour, reserved by antiquity for priests and sacred things, added to the reverence felt for a woman who to this day offers a unique precedent, in being the daughter of a commander-in-chief (Germanicus, as Imperator), and the sister, wife and mother respectively of three emperors, Caligula, Claudius and Nero.

Meanwhile, however, her principal champion, Vitellius, was attacked by accusations raised by the senator Junius Lupus. Vitellius was charged with treason and a desire for imperial power, to which Claudius might have leant an ear, had not Agrippina’s use of threats rather than her pleas converted him to the idea of exiling the accuser instead, formally denying him ‘fire and water’, Vitellius seeking no greater a punishment for him.

Book XII:XLIII Problems with the corn supply

Many portents occurred that year. Ominous birds roosted on the Capitol; houses collapsed in a series of earthquakes and, as fear spread, the weak were trampled underfoot by the panicking crowd. Also a shortage of corn and the resulting famine were taken as warnings. Nor were all the complaints uttered in private, for Claudius, while administering justice, was surrounded by a clamorous mob, driven into the farthest corner of the Forum, and hemmed in by force, until a way was forced through the hostile mass by a body of troops.

It was discovered that Rome had food for fifteen days, no longer, and the crisis was relieved only by the great beneficence of the gods and the mildness of the winter weather. Yet, by Hercules, Italy once exported legionary supplies to the remote provinces, nor is there any lack of agricultural potential now, rather it is that we rely on North African and Egyptian harvests, and the lives of the Roman populace depend on cargo-boats and chance.

Book XII:XLIV Trouble looms in Armenia

That same year, also, an outbreak of warfare between the Armenians and the Iberians (of eastern Georgia) was the cause of very serious issues between Parthia and Rome. The Parthian nation was now ruled by Vologeses I, the descendant of a Greek concubine on the mother’s side, who had gained the crown with his brothers’ agreement; Iberia was in the possession of the aged Pharasmanes I; while Armenia was held by his brother Mithridates, with our support.

Pharasmanes I had a son by the name of Radamistus, tall, handsome and noted for his physical strength, educated to embrace the national virtues, and with a high reputation among the neighbouring peoples. He claimed too often and too boldly for his ambitions to remain hidden, that the little kingdom of Iberia was being denied him by his father’s longevity. Pharasmanes, fearful of this youth eager for power and also supported by the people’s favour, while his own years were declining, directed him to other hopes and pointed to Armenia which, he observed, he himself had granted to Mithridates by expelling the Parthians.

Force however must wait, he added, some ruse by which they might catch him off guard was preferable. Radamistus, therefore, feigning a disagreement with his father, as if unable to endure his stepmother’s hatred, made his way to his uncle, and though treated by him with great kindness, as though he had been Mithridates’ own son, enticed the Armenian nobles to rebellion, undetected and even honoured further by Mithridates himself.

Book XII:XLV Radamistus invades Armenia

Assuming the mask of reconciliation, he returned to his father, and announced that all was ready that deceit could engineer, the rest must be pursued by arms. Meanwhile Pharasmanes invented a pretext for war: that, during his conflict with the king of Caucasian Albania, his appeal for help from Rome had been opposed by his brother, and he would avenge that injury by the latter’s destruction. Simultaneously, he entrusted a large force to his son.

He, by a sudden incursion, unnerved Mithridates and, forcing him from the plains, drove him into the fortress of Gorneae, protected by its situation and defended by a garrison of auxiliaries under the command of the prefect Caelius Pollio and a centurion Casperius. Nothing is so unknown to barbarians as the machinery and refinements of siege warfare, a branch of military operations well understood by ourselves.

Thus, after several attacks, ineffectual or worse, on the defences, Radamistus blockaded the fortress, and when force was disregarded, he appealed to the prefect’s avarice, despite Casperius’ protests that Mithridates, an allied king, and Armenia, a gift to him from the Roman people, were being overthrown by sinful gold. At last, with Pollio employing the pretext of enemy numbers and Radamistus his father’s orders, Casperius departed, on the assumption of a truce, in order to deter Pharasmanes from his campaign or, failing that, to explain the state of Armenian affairs to the governor of Syria, Ummidius Quadratus.

Book XII:XLVI Pollio is bribed to pressurise Mithridates into a treaty

With the centurion’s departure, the prefect, as if rid of a warder, exhorted Mithridates to ratify a treaty, referring to the ties of brotherhood, to Pharasmanes’ being the elder, and to other titles of kinship, namely his marriage to his brother’s daughter, and the fact that he himself was Radamistus’ father-in-law. Though the Iberians were for the time being the stronger force, he said, they would not reject peace; while he himself knew enough of Armenian treachery, his only refuge being a badly-provisioned fortress if Mithridates preferred to turn to weapons rather than an arrangement avoiding the spilling of blood.

While Mithridates hesitated despite these arguments, since the prefect’s advice was suspect, he having seduced a royal concubine and being thought open to every twist and turn of venality, Casperius meanwhile sought an audience with Pharasmanes, and demanded urgently that the Iberians raise the siege. The king’s replies in public were bland and mostly vague; but privately he warned Radamistus, by messenger, to advance the siege by all possible means.

The reward for treachery was increased accordingly, and Pollio in turn secretly induced the auxiliaries, by bribery, to demand peace, accompanied by their threat to abandon the position. As a result Mithridates was forced to accept the place and time suggested for ratification of a treaty, and leave the fortress.

Book XII:XLVII Mithridates betrayed

Radamistus’ first action was to embrace Mithridates fervently, calling him his father-in-law, his parent, adding his sworn oath that he would not employ steel or strong poison against him. At the same moment, he dragged him into a grove nearby, telling him that there the means for sacrifice had been provided, so that peace might be affirmed with the gods as witnesses.

Their custom is that whenever kings conclude an alliance they clasp hands, tie the thumbs together, and tighten the knot: the blood soon runs to the extremities, where a slight incision elicits a few drops, which each of them licks in turn. Such an agreement acquires mysterious force, as if consecrated by the blood shared. But on this occasion, he who tied the knot pretended to slip, and clasping Mithridates by the knees, threw him face down; at once men ran to him and clapped him in irons.

He was dragged away, at the end of a chain, to barbarians the ultimate disgrace; and soon the crowd who had experienced the harshness of his regime, were aiming blows and abuse at him. Against this, there were those who pitied so complete a change of fortune, while his wife following with their little children, filled the air with her laments. The prisoners were led away to separate covered wagons, awaiting Pharasmanes’ orders.

His desire for the crown was more powerful than his love for a brother, or his own daughter, and his nature was inclined to wickedness; yet he spared himself the sight of their being slain in his presence. While Radamistus, as if recalling the oath he had sworn, used neither steel nor poison against his sister and uncle, but killed them by throwing them to the ground and smothering them under a heavy pile of clothing. Mithridates’ sons were also murdered, because they had shed tears on the death of their parents.

Book XII:XLVIII Quadratus reviews the situation

Quadratus, in Syria, hearing that Mithridates had been betrayed and his kingdom appropriated by his murderers, called his council together, to inform them of events and decide whether he should exact revenge. A few spoke of their concern for the honour of the State, the majority of its security: any kind of foreign villainy was to be regarded with delight, they said, and the seeds of division should even be sown, as Roman emperors had often, under the guise of generosity, given away this same Armenia, to stir up barbarian minds. Let Radamistus keep his ill-gotten gains, as long as he was hated and infamous, since that was more use to us than if he had won them gloriously. This view was adopted, but lest they appeared to have endorsed a crime when the emperor might command otherwise, messengers were sent to Pharasmanes, telling him to withdraw from Armenia territory and recall his son.

Book XII:XLIX Julius Paelignus confuses the issue

The procurator of Cappadocia, Julius Paelignus, was doubly despised, both for his mental laziness, and his physical grotesqueness, yet was on terms of the greatest intimacy with Claudius, once he was free to amuse himself during his hours of idle leisure in the company of buffoons. This Paelignus, had assembled the provincial auxiliaries, with the aim of regaining Armenia. Plundering our allies rather than the enemy, his men absconded, leaving him defenceless against the barbarians, so he made his way to Radamistus. More than overcome by the prince’s generosity, he exhorted him to assume the royal insignia, and was present at the ceremony, as his sponsor and attendant.

Ugly reports of the event spread, and lest other Romans too were judged by Paelignus’ behaviour, the legate Helvidius Priscus was sent off, with a legion, to deal with the situation as required. After crossing the Taurus range at speed, then calming matters more by moderation than force, he was ordered to return to Syria, lest he initiated war with Parthia.

Book XII:L Vologeses attacks Armenia, Radamistus occupies the country

Since Vologeses, considering the opportunity had arrived to invade Armenia, once possessed by his ancestors and now gained by a foreign king through criminal means, gathered his forces, and prepared to install his brother Tiridates on the throne, so that no branch of the family should lack a kingdom.

The Parthian incursion drove the Iberians back, without a battle, and the Armenian towns of Artaxata (Artashat) and Tigranocerta (Silvan or Arzan) submitted. Then a severe winter, a shortage of supplies, and an epidemic due to both these causes, forced Vologeses to abandon the action.

Armenia, once again without a ruler, was occupied by Radamistus, more ferocious than ever towards such traitors, who were bound to rebel, given time. They in turn, though accustomed to servitude, lost patience, and fully armed surrounded the palace.

Book XII:LI Radamistus escapes, his wife Zenobia survives

The only recourse open to Radamistus lay in the speed of the horses that bore away himself and his wife. His wife however was heavy with child, though fear of the enemy and love of her husband sustained her at first. Yet with the continuous pace, which jarred and shook her womb and innards, she began to beg for an honourable death, to save her from the insult of captivity.

Initially he held and supported her, encouraging her, now wondering at her bravery, now sick with fear lest she be left in the hands of another. Finally overcome by his passion for her, and no stranger to violence, he drew his scimitar, and wounding her dragged her to the bank of the river Araxes (Aras), and gave her to its stream, so that even her corpse might be lost. He himself rode headlong to his native kingdom of Iberia.

Meanwhile Zenobia, as his wife was named, was found by shepherds, in a quiet backwater, breathing and showing other signs of life. Arguing, from the nobility of her appearance, that she was of high birth, they bound her wound, applied their local remedies, and on learning her name and travails, carried her to Artaxata, from which town, thanks to the attention of the people, she was escorted to Tiridates, and after a kind welcome was treated with royal honour.

Book XII:LII The death of Furius Scribonianus

In the consulate of Faustus Sulla and Salvius Otho (AD52), Furius Scribonianus was driven into exile, charged with questioning astrologers regarding the emperor’s death. His mother Vibidia was linked to the indictment, as being impatient of her prior punishment (she had been relegated). Her husband, Camillus, the father of Scribonianus, had taken up arms against the emperor, in Dalmatia (AD42); and Claudius ascribed it to his clemency that he was sparing this hostile breed for a second time.

The exile, however, did not survive long: whether he died a natural death or from poison being asserted according to the speaker’s belief. A draconian, but ineffective Senate decree ordered the expulsion of all astrologers from Italy.

A speech by the emperor followed, in which he praised those senators who voluntarily renounced their rank due to straightened circumstances, and commanded the removal of those who added impudence to poverty by remaining.

Book XII:LIII Pallas rewarded

At the same time, Claudius submitted a proposal to the senators regarding women who married slaves; and it was decided that if the woman had stooped so low without the knowledge of the slave’s owner, she should be classed as a slave, while if he had consented to the marriage, she was to be considered a freedwoman.

Barea Soranus, the consul designate, suggested that Pallas, whom Claudius identified as the deviser of the proposal, should be granted praetorian insignia and a hundred and fifty thousand gold pieces. Cornelius Scipio added that Pallas should receive the thanks of the nation, because though a scion of Arcadian kings (playing on the name of Evander’s ancestor, Aeneid VIII.51), he disregarded his ancient ancestry, to the benefit of the public, allowing himself only to be considered as one of the emperor’s servants.

Claudius earnestly assured them that Pallas, content with the honour, would remain in his former state of poverty. And a Senate decree was inscribed on official bronze, heaping praise on this freedman, the possessor of three million gold pieces, for his old-world frugality!

Book XII:LIV The activities of his brother Felix in Judaea

But his brother, Antonius Felix, who had held the governorship of Judaea for some time past, revealed no such humility, clearly thinking that, with such powerful backing, all wrongdoing could be indulged in with impunity. The Jewish people, it is true, had shown signs of disaffection in rioting prompted by Caligula’s order that his statue be placed in the Temple; and though his murder rendered compliance unnecessary, the fear remained that another emperor might demand the same.

Meanwhile, Felix was fuelling the flames, by untimely measures, emulated in his worst efforts by Ventidius Cumanus his colleague in the other half of the province, which was divided such that the populace of Galilee was subject to Ventidius, that of Samaria to Felix, areas previously in conflict, and now, in contempt of their overlords, with hatred less constrained.

They raided each other’s territory, therefore, sending out bands of robbers, sometimes engaging in battle, and turning over the thefts and spoils to their respective procurators, who were, at first, delighted. Then when the destruction quickly increased, and the procurators intervened with armed troops, the troops were defeated, and if not for reinforcements sent by Quadratus, the governor of Syria, the province would have been ablaze with conflict.

There was no great hesitation in inflicting the death penalty on those Jewish fighters who had caused the deaths of regular soldiers, but the question of Cumanus and Felix gave rise to greater embarrassment, since Claudius, on hearing of the cause of these disturbances, had empowered Quadratus to deal with the procurators himself. Quadratus, as a result, exhibited Felix among the judges, and welcomed him to the tribunal, hoping to quell the zeal of his accusers; Cumanus was convicted of the wrongs that both had committed, and quiet returned to the province.

Book XII:LV Trouble in Cilicia

Not long afterwards, the tribes of barbarous Cilicians known as the Cietae, who had caused trouble on many previous occasions, who were encamped in their rugged hills and led by Troxobor, descended to the townships and the coast and dared to use force against farmers and townsmen, and even more often merchants and ships’ captains, The city of Anemurium (Anamur, Turkey) was besieged, and a cavalry troop sent to its relief from Syria, led by the prefect Curtius Severus, was routed, because the rough ground in the vicinity, suited to fighting on foot, did not allow effective cavalry engagement.

Eventually King Antiochus IV of Commagene, the coastline being his responsibility, by cajoling the masses and deceiving their leader, scattered the barbarian forces and, after executing Troxobor and a few of the leading chieftains, pardoned the rest.

Book XII:LVI The draining of Lake Fucinus (Lago di Celano)

At about this time, a drainage channel under the mountain (Monte Salviano) between Lake Fucinus and the river Liris (Liri) was completed, and a naval fight staged on the lake itself, so that the magnitude of the result could be viewed by many. The display was on the model of an earlier spectacle mounted by Augustus, on his artificial lagoon adjoining the Tiber, but with lighter vessels and a smaller force.

Claudius armed triremes, quadriremes, and nineteen thousand men. Rafts marked the circumference to allow no easy escape, but with enough space within to display vigorous rowing, the helmsmen’s skills, the shock of encounter, and all the usual action in battle. Companies and squadrons of the praetorian cohorts were stationed on the rafts, fronted by shielded platforms from which to operate catapults and ballistae. The rest of the lake was occupied by marines on decked vessels.

The lakeshore, hills and mountain ridges formed a kind of amphitheatre, filled with an innumerable crowd of people from the neighbouring towns, and even Rome itself, drawn by curiosity or respect for the emperor. He and Agrippina presided, he dressed in a magnificent military cloak, she, not far away, in a Greek mantle of cloth of gold.

The battle, though between convicted criminals, was contested with the spirit and bravery of free men, and after much blood-letting the combatants were spared execution.

Book XII:LVII The partial failure of the scheme

At the end of the display, the tunnel was opened for the discharge of water, but faulty construction was immediately evident, the passage not having been sunk to the maximum or even mean depth of the lake, and time had to be allowed for it to be dug to a lower level, with a view to gathering a fresh audience and mounting a gladiatorial display, on pontoons also laid for an infantry battle.

Moreover, a banquet had been served near the outlet to the lake, leading to widespread panic when the water broke through carrying all away nearby, and either overwhelming those further away or terrifying them with the shock and its reverberation. Agrippina seized on the emperor’s agitation to accuse Narcissus, as Minister of Works, of greed and fraud. He was not to be silenced, and attacked her, in return, as an overbearing woman of excessive ambition.

Book XII:LVIII Nero marries and exerts his influence

In the consulate of Decimus Junius and Quintus Haterius (AD53), Nero, at the age of sixteen, married Claudia Octavia the emperor’s daughter.

Desiring to shine, through liberal learning and a reputation for eloquence, he took up the cause of Ilium (Hisarlik, Turkey) and gave a speech on the Romans’ Trojan descent; Aeneas as the progenitor of the Julian line; and other traditions which were not far from fable; with the result that the inhabitants of Ilium were released from all state taxation.

Again, through his oratory, the colony of Bononia (Bologna) which had been destroyed by fire, was assisted by a grant of one hundred thousand gold pieces; the inhabitants of Rhodes regained their freedoms, the frequent forfeiting or re-confirmation of these being the result of sedition at home balanced against their military service abroad; and finally Apamea on the Maeander (Dinar, Turkey) which had suffered an earthquake was relieved from tribute for the following five years.

Book XII:LIX The death of Statilius Taurus

Yet Claudius, through the continued machinations of Agrippina, was compelled to display extreme harshness, Statilius Taurus, of famous wealth and whose gardens she coveted, being ruined after being accused by Tarquitius Priscus, who had been legate to Taurus when the latter, exercising proconsular power, governed Asia Minor. On their return, Priscus charged him with acts of extortion, but more seriously with practising magical rites.

Taurus, impatient of these false accusations and his undeserved disgrace, anticipated the Senate’s verdict and took his own life. As a result, Priscus was driven from the House, a point which the senators, in their loathing of informers, carried in the face of Agrippina’s intrigues.

Book XII:LX Claudius devolves powers to his procurators

On several occasions during the year, Claudius was heard to remark that the judgements of his procurators ought to carry as much weight as his own. In order that his views might not be taken as unfortunate lapses, a fuller and wider provision to that effect was further enacted by Senate decree. For the divine Augustus had ordered that legal powers be conferred on the members of the equestrian order who governed Egypt, and that their decisions were to apply as though they had been handed down by the magistrates in Rome.

Later, both in other provinces and the city, a host of judgements were permitted them that had previously been handled by the praetors. Claudius granted them the full powers so often disputed by public dissent or force, for example when the Sempronian rogations placed the equestrian order in possession of the courts (122BC); when the Servilian law returned these to the Senate (106BC); or when in the days of Marius and Sulla it provided the main grounds for conflict.

However the partisanship then was between the classes and, whoever won, the results applied generally. Gaius Oppius and Cornelius Balbus, supported by the power of Julius Caesar, were the first individuals who could decide the conditions for peace, or the management of war. There is little purpose in mentioning their successors, Matius, Vedius, and the names of other Roman knights with such exalted powers, given that Claudius had placed the freedmen whom he had set in charge of his personal affairs on a level with himself and the law.

Book XII:LXI Claudius grants the island of Cos exemption from tribute

Claudius next raised the question of exempting the island of Cos from tribute, and spoke at length about their ancient history: the oldest inhabitants of the island having been Argives, or possibly the people of Coeus, the father of Latona; later the advent of Aesculapius having brought us the art of medicine, celebrated most highly by his descendants (for example Hippocrates). Here, Claudius listed their individual names, and the times in which they had flourished.

Indeed, Gaius Xenophon, he said, to whose knowledge he himself had recourse, was also of that same ancestry, and he asked that, at his request, the Coans might be exempted from all tribute in future, to cultivate their island in the service of its god. No doubt a great number of their services to the Roman people, and of victories which they had shared in, might have been cited, but Claudius, with his usual affability, did not wish to add extraneous arguments to his concession to a single individual.

Book XII:LXII An embassy from the Byzantines

In contrast, the Byzantines, when granted an opportunity to speak, in protesting to the Senate about the magnitude of their burden, rehearsed their whole history. Beginning with the treaty (146BC) struck with ourselves, at the time of our war against the pretender (Andriscus) to the throne of Macedonia, whose dubious birth earned him the title of Pseudo-Philip, they recalled the forces they had sent against Antiochus III (192BC), Perseus of Macedon (168BC) and Aristonicus (Eumenes III, 129BC); their assistance to Marcus Antonius in his war against piracy (101BC); their assistance to Sulla, Lucullus, and Pompey, and more recently their services to the Caesars, since they occupied a territory well-placed for the transit of generals and armies by land or sea, and the transport of supplies.

Book XII:LXIII The history of Byzantium

For it was on the narrow straits between Europe and Asian Minor, at the extreme end of Europe, that Byzantium was founded by Greeks, who on consulting the oracle of Pythian Apollo as to where to build a city were told to seek a home opposite the country of the blind. That referred it seems to the inhabitants of Chalcedon, opposite, who had arrived from Megara before them, surveyed the qualities of the area, and chosen for the worse.

For Byzantium itself has fertile soil, and rich waters, since vast shoals of tuna, on emerging from the Euxine, fearful of the shelving reefs beneath the sea, shun the winding coast of Asia Minor and head for the harbour opposite. They were thus a thriving and wealthy community.

However, driven by the burden of tribute, they now asked for an exemption or at least a reduction, and their request was accepted by the emperor, given their exhaustion after the recent Thracian (AD46) and Bosporan (AD48) wars which entitled them to relief. They were therefore exempted from tribute for five years.

Book XII:LXIV Ominous portents

In the consulate of Marcus Asinius and Manius Acilius (AD54), it appeared from a series of portents that a change for the worse was at hand. Fire from the heavens flickered around the soldiers’ standards and tents. A swarm of bees settled on the heights of the Capitol. It was said that hermaphrodites were born, and a pig with the talons of a hawk. It was counted amongst these portents that the numbers of each magistracy were diminished in the same way by the deaths of a quaestor, an aedile, a tribune, a praetor and a consul, all within a few months.

But Agrippina felt especial fear. Troubled by a comment Claudius let fall, when intoxicated, that it was his fate to suffer, and then punish, his wives’ ill-conduct, she decided to act, and quickly. First though, she ruined Domitia Lepida the Younger, and for a woman’s reason, that Lepida, as the daughter of Antonia the Elder, grand-niece to Augustus, first cousin once removed to Agrippina, and sister of the latter’s ex-husband Gnaeus Domitius, believed herself equally illustrious.

There was little to distinguish them in beauty, age and riches; and since each was as shameless, disreputable, and violent as the other, they were no less rivals in their vices than in the advantages they had received from fortune’s favour. And the fiercest quarrel by far was as to whether the aunt or the mother was to prevail as regards Nero; since the aunt, Lepida, was trying to captivate his young mind by flattery and generosity, while on the other hand, his mother, Agrippina, grim and menacing, might grant her son an empire, but would never endure him as emperor.

Book XII:LXV Domitia Lepida the Younger condemned to death

However the actual charges against Lepida were that she had sought the life of the emperor’s wife by the use of magic spells, and that by failing to control her regiments of slaves throughout Calabria she was disturbing the peace of Italy. On these grounds the death penalty was pronounced, despite the determined opposition of Narcissus, who with his deepening suspicion of Agrippina, was said to have remarked to his closest friends: that his own destruction was certain, whether Britannicus or Nero came to power; yet Claudius’ kindness to himself had been such that he would sacrifice his own life for the emperor’s benefit.

Messalina and Silius, he said, had been condemned, and there were like grounds for a like charge; there was no fear for the emperor’s life if Britannicus succeeded to the throne: but the stepmother’s intrigues were aimed at destroying the whole imperial House, a much greater disgrace to him than his keeping quiet about her predecessor’s infidelities. Though there was no lack of infidelity even here, adultery with Pallas leaving no doubt that she valued her dignity, her modesty, her body, her all, less than the throne.

With these and other comments he would embrace Britannicus, praying for him to reach man’s estate as swiftly as possible then, raising his hands now towards the heavens, now towards the prince, that once grown to manhood, he would expel his father’s enemies and take vengeance on his mother’s murderers.

Book XII:LXVI Agrippina obtains poison

Narcissus’ health suffered under this weight of cares, and he left for Sinuessa’s (Mondragone, Italy) medicinal springs, to recover his strength in a gentler climate. Agrippina, long determined on murder, eager to seize the opportunity offered, and not lacking helpers, now took advice as to the type of poison to be used. Too swift and drastic an action would reveal the crime; whereas if she chose something slow and enervating, Claudius, facing his end and aware of her treachery, might revert to affection for his son.

Something choice was needed, to derange the mind while delaying death. A specialist in such things was found, a woman named Locusta, lately condemned on a poison charge, and long retained as an instrument of power. This woman’s ingenuity supplied the potion, to be administered by the eunuch Halotus, who was accustomed to bringing in and tasting the emperor’s food.

‘Agrippina’

History of Rome and the Roman people, from its origin to the establishment of the Christian empire - Victor Duruy (1811 - 1894) (p473, 1884)

Internet Archive Book Images

Book XII:LXVII Xenophon completes the murder of Claudius

So widely known was all this later, that the historians of the period recorded that the poison was introduced into a tasty dish of mushrooms, though the full force of the drug was not immediately felt, due to Claudius’ lethargy or his state of intoxication; at the same time a loosening of the bowels seemed to relieve him.

Agrippina, therefore, was terrified, and since it was her own death that was to be dreaded, scorning to act in person, she invoked the complicity of the doctor Xenophon, already forewarned by her. He, as if encouraging the emperor’s effort to vomit, is believed to have plunged a feather dipped in a swift-acting poison down Claudius’ throat, aware that the greatest crimes must begin dangerously to end profitably.

Book XII:LXVIII Agrippina detains Britannicus and his sisters

Meanwhile the Senate had been convened, and the consuls and priests were formally praying for the emperor’s safety at the very moment when the lifeless body was being swathed in blankets and warm bandages, while already the requisite measures were being taken to secure Nero’s accession.

Firstly Agrippina prevented Britannicus from leaving his room, by clasping him in her arms as though heart-broken and seeking comfort, calling him the living picture of his father, and by employing diverse other means. She likewise detained his sisters, Antonia and Octavia, and had guards secure every entrance. She gave out news continuously that the emperor’s health was improving, to maintain the soldier’s hopes, and waited for the opportune moment as advised by the astrologers.

Book XII:LXIX Nero is hailed by the guards’ camp

Then, at noon on the thirteenth of October, the palace gates suddenly swung open, and Nero with Burrus in attendance, exited to meet the cohort who were on guard according to the rules of the service. Once there, at a hint from the prefect, he was greeted with cheers, and placed in a litter.

Some of the men are said to have hesitated, looking back and asking where Britannicus might be: then as no one promoted the alternative, they accepted the choice on offer. Nero was carried to the camp and, after a few words appropriate to the moment and following his father’s generous example, promised them a gratuity, and was hailed as emperor.

The decision of the troops was supported by Senate decree, nor was there any hesitation in the provinces. Claudius was voted divine status, and his funeral solemnities celebrated with the magnificence accorded those of the deified Augustus, Agrippina emulating the lavishness of her great-grandmother Livia.

Claudius’ will however was not read aloud, lest the injustice and invidiousness of his preferring the stepson to the son should disturb the minds of the crowd.

End of the Annals Book XII: XLI-LXIX