Cornelius Tacitus

The Annals

Book XIV: I-XXXIX - The murder of Agrippina, war in Armenia and Britain

‘Bonus Eventus’

History of Rome and the Roman people, from its origin to the establishment of the Christian empire - Victor Duruy (1811 - 1894) (p76, 1884)

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2017 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XIV:I Nero again contemplates murdering Agrippina.

- Book XIV:II Suggestions that Agrippina sought incest with her son.

- Book XIV:III Nero plots her assassination.

- Book XIV:IV The scheme is put in motion.

- Book XIV:V The murder attempted.

- Book XIV:VI Agrippina sends word to Nero of her ‘accident’

- Book XIV:VII Nero panics, in consequence.

- Book XIV:VIII The assassination of Agrippina.

- Book XIV:IX The prophecy fulfilled.

- Book XIV:X Nero haunted by the crime.

- Book XIV:XI He rakes up old charges against her.

- Book XIV:XII Decrees, portents, restorations.

- Book XIV:XIII Nero returns to Rome in triumph.

- Book XIV:XIV He indulges in chariot-racing and the lyre.

- Book XIV:XV The Games of Youth.

- Book XIV:XVI Nero toys with poetry and philosophy.

- Book XIV:XVII Nuceria (Nocera) versus Pompeii.

- Book XIV:XVIII Pedius Blaesus and Acilius Strabo indicted.

- Book XIV:XIX The deaths of Domitius Afer and Marcus Servilius.

- Book XIV:XX The Greek Games of AD60.

- Book XIV:XXI The pretext for imported novelty.

- Book XIV:XXII Portents and sacrilege.

- Book XIV:XXIII Corbulo marches on Artaxata.

- Book XIV:XXIV The city of Tigranocerta surrenders.

- Book XIV:XXV Legerda taken, and a Hyrcanian alliance.

- Book XIV:XXVI Tigranes VI granted Armenia.

- Book XIV:XXVII Decline of the Italian colonial towns.

- Book XIV:XXVIII Rulings and a banishment.

- Book XIV:XXIX Trouble in Britain.

- Book XIV:XXX Destruction of the Druids.

- Book XIV:XXXI Revolt of the Iceni.

- Book XIV:XXXII Camulodunum (Colchester) destroyed.

- Book XIV:XXXIII Londinium (London) and Verulamium (St Albans) follow..

- Book XIV:XXXIV Suetonius Paulinus chooses his location for battle.

- Book XIV:XXXV Boudicca (Boadicea) addresses her warriors.

- Book XIV:XXXVI Suetonius Paulus exhorts his troops.

- Book XIV:XXXVII Defeat of the Iceni.

- Book XIV:XXXVIII The troops in Britain strengthened.

- Book XIV:XXXIX Peace achieved through moderation.

Book XIV:I Nero again contemplates murdering Agrippina

In the consulate of Gaius Vipstanius and Gaius Fonteius (AD59), Nero no longer postponed the long-considered crime, since a long period of authority had fuelled his audacity, and day by day his love for Poppaea burned more fiercely. She, who while Agrippina lived, saw no hope of marriage for herself, nor divorce for Octavia, hurled reproaches at the emperor, and sometimes shafts of wit, calling him the ‘little ward’, submissive not only to other’s orders regarding his rule, but even lacking basic freedoms. Why, she asked, was their marriage deferred? Presumably her beauty displeased him, or her grandfather’s triumph, or was it her fecundity and true spirit? Or was there the fear that, once she was his wife, she might disclose the wrongs done to senators, the anger of the populace against his mother’s pride and avarice?

Or if Agrippina would brook no daughter-in-law not hostile to her son, she argued, let she herself be restored to Otho: or go to whatever corner of the earth existed, where she might rather hear, not witness, this insult to the emperor, and no longer be entangled in his troubles. None opposed such reproaches, pressed home as they were with tears and seductive art, all longed for the mother’s hold to be broken, yet none believed his hatred could harden him to murder.

Book XIV:II Suggestions that Agrippina sought incest with her son

Cluvius states that Agrippina’s craving to retain her power, was carried so far that at noon, when Nero was warmed by food and wine, she often presented herself to her tipsy son, ready for incest and dressed for the part. Already lascivious kisses and endearments, heralding the guilty act, had been noted by his intimates, before Seneca sought in a woman the antidote to Agrippina’s feminine wiles, by introducing the freedwoman Acte, seemingly alarmed at her own danger and Nero’s supposed infamy, to report to him that the incest was already common knowledge, his mother boasting of it, and that the army would not tolerate rule by a sacrilegious emperor.

Fabius Rusticus claims that Nero, not Agrippina desired it, the scheme being wrecked by that same freedwoman’s astuteness. But other authors too support what Cluvius puts forward, and tradition leans towards them, either the monstrous idea truly being conceived in Agrippina’s mind, or it being the more credible that such unheard of lustfulness be seen in one who, in hopes of winning power, had when still a girl committed sexual acts with Marcus Lepidus; who for similar reasons had prostituted herself to Pallas’ desires; and who had been weaned to a thing so shameful by marriage with her uncle.

Book XIV:III Nero plots her assassination

So Nero now avoided meeting privately with her, and whenever she withdrew to her gardens or her estates at Tusculum (near Frascati) or Antium (Anzio), he commended her cultivation of leisure. Finally, considering her a burden upon him wherever she might be, he decided to kill her, only debating at that point as to whether it should be by poison, the blade, or some other violent end.

At first he chose poison. But if it were given her at the emperor’s table, then it would not be ascribed to chance, Britannicus having died in that very manner; and it would seem difficult to try and suborn the servants of a woman whose experience of crime made her vigilant against deceit; and besides she would have protected herself by prior use of antidotes. The employment of cold steel, with its attendant bloodshed, no one could find a way to hide; and besides there was the fear that whoever was chosen for such a task might well disobey orders.

It was the freedman Anicetus, admiral of the fleet at Misenum (Miseno), Nero’s childhood tutor, and through mutual hatred an enemy of Agrippina, who suggested the solution. He pointed out that a vessel could be built, part of which could be cunningly made to detach itself at sea, dashing the unsuspecting victim underwater: nothing offered such scope for accidents as the sea; and if she was shipwrecked and lost, who could be so unjust as to attribute what wind and wave had perpetrated to any wrongdoing? The emperor would of course need to grant the deceased a temple, altars, and the other trappings of filial piety.

Book XIV:IV The scheme is put in motion

This clever scheme was accepted, even the timing was favourable, as Nero was accustomed to celebrate the festival of Minerva (the Quinquatria, 19-23 March) at Baiae. He lured his mother there, giving out that parental irascibility must be endured, and he must show a forgiving spirit, in order to give birth to rumours of a reconciliation, which Agrippina might credit, given a woman’s ready belief in what gave her pleasure.

He greeted her arrival on the shore, as she had come from Antium (Anzio), took her hand, embraced her and escorted her to the villa named Bauli, washed by an arm of the sea between the promontory of Misenum (Miseno) and the lake of Baiae. Here among other vessels lay a more ornate one, seemingly one further attention granted his mother, since she had been accustomed to travel by water in a trireme with marines at the oars. She had then been invited to dinner also, so that night would be at hand to conceal the crime.

It is well established that some informer appeared, and that Agrippina, warned of a plot but uncertain whether to believe it, journeyed to Baiae carried in a litter. There, her fears allayed by flattery, she received a cordial welcome and a seat above the emperor himself. Now with a flow of words, at one moment boyishly familiar, and then again frowning as though to share something serious, after long drawn-out entertainments, Nero attended her departure, clinging more closely than usual to the sight of her and to her embrace, either in a last show of deceit, or because the last look at his doomed mother daunted even his brutal spirit.

Book XIV:V The murder attempted

A night bright with stars, and the quiet of a calm sea, seemed sent by the gods as if to reveal the evidence of crime. The vessel had made scant progress as yet, and two of Agrippina’s household were in attendance: Crepereius Gallus was standing not far from the tiller, while Acerronia, leaning above the feet of the reclining princess, was joyfully recalling the son’s penitence and the mother’s restoration to favour, when the signal was given, and the canopy over them, heavily weighted with lead, suddenly dropped, crushing Crepereius, and killing him instantly.

Agrippina and Acerronia were protected by the high sides to the couch which by chance were too solid to yield to the impact. Nor did the break-up of the vessel follow, confusion being universal and even those aware of the plot impeded by the mass of those who were not. Then the oarsmen decided to lean to one side and so sink the vessel, but agreement did not come promptly enough for sudden measures, and a counter-effort by others provided an opportunity for the victims’ gentler entry into the waves.

Acerronia, in fact, unwisely calling out that she was Agrippina and demanding aid for the emperor’s mother, was despatched with poles, oars and every piece of nautical equipment to hand: but Agrippina, silent, and so less easily detected (though she received a wound in the shoulder), swam for it, then reaching some sailing-vessels was carried to the Lucrine lake, and brought to her villa.

Book XIV:VI Agrippina sends word to Nero of her ‘accident’

There she reflected on the evident motive for the treacherous invitation she had received, and the striking attention shown her, and on the fact that the vessel, close to shore, not driven before a gale or striking some reef, had collapsed from above as if by some earthly contrivance; while, in considering Acerronia’s murder, and glancing at her wound, she realised her sole defence against treachery was not to show it had been perceived.

She therefore sent her freedman Agermus to tell her son that by the grace of the gods and his good fortune she had avoided a serious accident; begging him, however great his alarm at his mother’s condition, to defer the kindness of a visit; her need at the moment was for rest. Meanwhile, with apparent unconcern, she applied balm to her wound and warm bandages to her body. She also ordered a search for Acerronia’s last will and testament, and the sealing up of her property, a process that could not be masked.

Book XIV:VII Nero panics, in consequence

Meanwhile, as Nero was waiting for messengers to confirm the deed had been done, the news arrived that Agrippina had escaped with only a slight wound from a blow, but had suffered enough danger not to doubt its author. Then half-dead with terror, he swore she would be there at any moment, eager for revenge, and whether she armed her slaves, or roused the troops, or appealed to the Senate and the people, charging him with the shipwreck, her wound, and the killing of her friends, what could aid him against her? Unless it were Burrus and Seneca whom he had sent for immediately, perhaps to test their reaction, or as being already in the know.

A long silence ensued on both their parts, either not to give adverse advice in vain, or because they believed the matter had reach a point where, unless Agrippina was forestalled, Nero must perish. Then Seneca went so far as to glance at Burrus and ask if the fatal order should be given to the soldiers. Nero replied that the guards, attached as they were to the entire house of the Caesars and the memory of Germanicus, would never venture such an atrocity against the latter’s issue: Anicetus must make good his promise. He, in fact, without hesitating, asked to take full responsibility for the deed.

His words brought a declaration from Nero that this day gifted him an empire, and a freedman was the author of that great gift: Anicetus was to go swiftly, and take with him the men most prompt to obey orders. Hearing that Agrippina’s messenger Agermus had arrived with a message, he himself set the scene for the man to be charged with treason, throwing a sword at his feet as he performed his errand, then ordering him clapped in chains as if the man himself had dropped it; so as to pretend his mother had aimed at the emperor’s life, and taken refuge in suicide herself for fear of being apprehended.

Book XIV:VIII The assassination of Agrippina

In the meantime, Agrippina’s situation became known, as if the result of an accident, and as the news spread there was a rush to the beach. Some clambered over the sea-wall, others into nearby sailing boats; others waded into the sea as far as they could go; while some stood with outstretched arms; the whole shore filled with lamentations, vows, and the clamour of endless questions and uncertain replies. A vast crowd poured in, bringing lights, and, as the news that she was safe permeated, set out to offer their congratulations, until at the sight of the arrival of an armed and menacing column they were forced to scatter.

Anicetus now cordoned off the villa and, breaking down the door, dragged aside the servants in the way, until he reached the entrance to the bedroom. A few servants stood there, the rest had fled in terror at the onslaught. There was a dim light in the room, and a single handmaid, Agrippina’s anxiety growing moment by moment, as to why no one had come from her son, not even Agermus: joyful tidings wore another face; now there was only solitude, loud alarms, and the signs of a final act of evil.

Then the maid rose to go: ‘Do you too forsake me,’ Agrippina began, then looking behind her saw Anicetus accompanied by Herculeis, a trireme captain, and Obaritus, a captain of marines. If he had come, she said, to visit her, he could return with word she was recovered, if to perform a crime. she would not believe it of a son; matricide could not have been commanded.

Her executioners surrounded the couch, and the trireme captain struck at her head with a club. The captain of marines was already drawing his sword to bring about her death, when she offered her belly to the blow: ‘Strike here,’ she cried, and with many a wound was despatched.

‘The tragic death of Agrippina’

Charles Ange Boily, after Benjamin Samuel Bolomey, c. 1753 - 1813

The Rijksmuseum

Book XIV:IX The prophecy fulfilled

So far the accounts agree. But some affirm and some deny that Nero now came to inspect his mother’s body, and that he praised the corpse’s figure. She was cremated the same night on a banqueting couch, with modest rites; nor while Nero reigned was the earth piled up to enclose the ashes.

Later, through the attention of her servants, she received a humble tomb, close by the road to Misenum and that villa of Julius the dictator, which looks from its highest point to the bay spread below. Now, as the pyre was kindled, one of her freedmen, Mnester, ran a sword through his body, whether from love of his mistress or fear of execution is unknown.

This was the end to which, years before, Agrippina had given credence, and for which she had shown contempt. For on her enquiring as to Nero’s destiny, the astrologers had replied that he would reign but kill his mother; and: ‘Let him kill’, she had said, ‘so long as he reigns.’

Book XIV:X Nero haunted by the crime

Yet only when the crime was done, did Nero realise its magnitude. For the remainder of the night, sometimes silent and unmoving, often starting to his feet in fear, his mind a blank, he waited for the daylight as if it were bringing him death.

It was the adulation of the centurions and tribunes, organised by Burro, that first gave Nero hope, as they grasped his hand and congratulated him on escaping the danger presented by his mother’s crime. His friends then visited the temples, and given the example, the nearest towns of Campania gave witness to their joy with sacrifices and deputations.

He himself, in a contrasting display of hypocrisy, was mournful as if remorseful at his own preservation, and tearful at his mother’s death. Yet because the grave aspect of that sea and those shores obtruded on his gaze, the landscape not changing as human faces do (with some believing trumpet calls were heard from the surrounding hills, and lamentations from his mother’s grave), he withdrew to Naples, and sent a letter to the Senate, the sum of which was that Agermus, an intimate freedman of Agrippina armed with a blade, had been revealed as an assassin, and that Agrippina, conscious of having prepared the crime, had paid the penalty.

Book XIV:XI He rakes up old charges against her

He added a list of less recent charges: that she had hoped to share power, and for the praetorian guard to swear allegiance to a woman, and for the Senate and people to do the same; and that later in frustration she had become an enemy of the soldiers, the senators and the populace, opposing the gratuities and gifts of food, and had worked for the ruin of illustrious men.

With what effort had he not succeeded in preventing her invading the Senate and giving the response to foreign nations! He attacked the Claudian reign indirectly, attributing every scandal of that period to his mother, calling her death a public blessing. Even the incident of the shipwreck was related: though who could ever be foolish enough to believe it an accident, or that only one solitary man had been sent, by a woman half-drowned, to make his way past all the imperial guards and marines with a weapon!

It was Seneca therefore, who by composing such a speech had penned a confession, whom public opinion censured, no longer Nero, whose savagery was beyond all protest.

Book XIV:XII Decrees, portents, restorations

Nevertheless, in a spirit of wondrous emulation among the nobility, it was decreed that thanksgivings be held at all the sacred sites; that the Festival of Minerva, during which the conspiracy had been revealed, be celebrated with annual games; that a gold statue of the goddess, with an image of the emperor nearby, be erected in the Senate House; and that Agrippina’s date of birth (6th of November) be entered among the inauspicious days.

Thrasea Paetus, had usually allowed previous marks of adulation to pass, either by keeping silence or with a brief nod of assent, but now he left the House, creating a source of risk to himself, despite planting no seed of independence in the rest.

Idle portents also appeared, thick and fast. A woman gave birth to a snake, another was killed in her husband’s embrace; the sun was suddenly eclipsed; and the fourteen districts of the capital were struck by lightning. Which events, however, occurred without the gods’ being concerned, as Nero’s rule and wickedness continued for many years thereafter.

As for the rest, to exacerbate popular feeling against his mother, and to show that his own leniency had increased with her death, he restored two women of high rank, Junia Calvina and Calpurnia, along with the ex-praetors Valerius Capito and Licinius Gabolus previously driven into exile by Agrippina, to their native soil.

He even allowed the return of Lollia Paulina’s ashes, and the erection of a tomb; also Iturius and Calvisius, whom he had relegated a short while ago, he now absolved from punishment. Though Silana, having returned to Tarentum (Taranto) from distant exile, as Agrippina through whose enmity she had fallen was already weakened or had relented, had since died a natural death.

Book XIV:XIII Nero returns to Rome in triumph

Still, Nero lingered in the towns of Campania, anxious as to how to effect his entry to Rome, and whether he would meet with obedience on the part of the Senate, or enthusiasm on that of the crowd. Against his nervousness, all of the scoundrels, of whom no court in existence has ever proved more prolific, asserted that Agrippina’s name was loathed, and that her death had gained him the favour of the populace: let him enter intrepidly and experience the reverence felt for his person! At the same time, they asked leave to precede him.

Indeed, they found an eagerness greater than promised, the tribes on their way to meet him, a column of senators in festive dress, with their wives and children, ranked according to age and gender, and tiers of seats erected for spectators, as if to observe a triumph, past which he progressed.

From there, full of pride, victor over a nation of slaves, he made his way to the Capitol, gave thanks, and again abandoned himself to every vice, having been constrained till now, though scarcely repressed, by some sort of deference to his mother.

Book XIV:XIV He indulges in chariot-racing and the lyre

It was an old desire of his to drive a chariot and four, and a no less distasteful ambition to sing to the lyre in the theatrical manner. He recalled that horse-racing was the sport of kings, practised by the leaders of antiquity, celebrated in the glorious works of the poets, and performed in honour of the gods. Indeed the practice of song was sacred to Apollo, and this great and prescient deity was seen to stand so attired, not only in Greek cities but also in Roman temples.

He could no longer be contained when Seneca and Burrus decided to concede the one point rather than have him carry both. An area was enclosed in the Vatican valley, where he could command his horses without being seen by all. Soon the people were summoned at will, and extolled his praises, as is the way of crowds hungry for amusement, and joyful if the emperor has the same inclination.

However, this shameful publicity brought not satiety as expected, but an incitement to perform. And thinking to ameliorate his own disgraceful actions, by tarnishing others, he brought to the stage those scions of the nobility rendered venal through lack of funds. They having passed on, I regard it as a duty to their ancestors not to record them by name. For the disgrace is his who rewards an offence rather than preventing it. He even compelled notable Roman knights to promise their services in the arena, one would have said by means of vast inducements, if it were not that gifts from one with the power to command are applied with the force of compulsion.

Book XIV:XV The Games of Youth

Not wishing as yet to disgrace himself on a public stage, he instituted the so-called Games of Youth (Juvenalia), for which people volunteered their names indiscriminately. Neither rank, nor age, nor a public career, prevented anyone from practising the arts of Greek and Latin theatre, down to gestures and music not intended for the male sex. Even illustrious women studied indecent parts; and in the grove which Augustus had planted round a lake created for the navy to perform their displays, little meeting-places and drinking-dens sprang up, with inducements to voluptuousness exposed for sale.

Funds were made available too, for the virtuous to spend as compelled, and the extravagant for the glory of it. Thence debauchery and scandal flowed, nor has anything contributed more in the way of lasciviousness to our long-corrupted morality than that rabble. Even in the virtuous arts, decency is hard to maintain, far less could any vestige of shame or modesty or integrity survive amidst that vicious rivalry.

Finally, Nero took the stage himself, trying out his lyre, giving it close attention, and practising a few notes for his singing-masters who were standing by. A guards cohort had been added to the audience, tribunes and centurions, and Burrus with his sighs and applause; and for the first time ever, a company of Roman knights known as the Augustiani, notably young and muscular, some wanton by nature, others for the sake of gaining influence. They were there to provide thunderous applause day and night; apply divine epithets to the emperor’s form and voice; and earn, as if by virtue, fame and honour.

Book XIV:XVI Nero toys with poetry and philosophy

Yet, lest it were only the emperor’s theatrical skills which gained attention, he also affected the study of poetry, gathering together those with some skill in composition, but not yet distinguished. After dining they sat with him, stringing together verses they had brought, or invented on the spot, and filling out phrases provided, in one way or another, by the emperor himself, the method being obvious from the poems themselves, which lacked force, inspiration, or fluency by way of a unified style.

He even granted time to doctors of philosophy, after dinner, to enjoy the hostile battle of assertions. Nor was they any lack of those, with gloomy faces and expressions, desirous of being seen amidst these princely entertainments.

Book XIV:XVII Nuceria (Nocera) versus Pompeii

At about that time, a minor incident led to serious trouble between the colonies of Nuceria (Nocera) and Pompeii, during a gladiatorial show staged by Livineius Regulus, whose removal from the Senate has been noted elsewhere.

With the freedom typical of country places, the crowd took turns in hurling abuse, then stones, finally resorting to weapons; the Pompeians, in whose town the spectacle was being presented, proving the stronger.

As a result, many of the Nucerians were carried home to their township, their bodies maimed and wounded, where most mourned the death of a parent or a child. Judgment on the matter was delegated by the emperor to the Senate, and by the Senate to the consuls. And on it being returned to the Senate once more, the Pompeians were barred from holding any such gathering again for ten years, while the illegal factions they had formed were dissolved.

Livineius and the other instigators of the conflict were punished with exile.

Book XIV:XVIII Pedius Blaesus and Acilius Strabo indicted

Pedius Blaesus too was removed from the Senate, accused by the inhabitants of Cyrene (Shahhat, Libya) with violating the treasury of Aesculapius and, for money and to curry favour, manipulating the process of military recruitment.

An indictment was also brought by Cyrene against Acilius Strabo, who had held praetorian powers and been sent by Claudius to pass judgement regarding land, handed down by his father to their king, Ptolemy Apion, which the latter had bequeathed along with the kingdom to the Roman people (96BC). It had been taken over by neighbouring landowners who relied on their long-accepted annexation as granting fair and just title.

So, when judgement went against them, there was an outbreak of ill-will towards the judge. The Senate could only reply that Claudius’ instructions were unknown to them, and the present emperor would need to be consulted. Nero, while endorsing Strabo’s verdict, wrote that none the less he was minded to assist, and yielded them the land they had taken.

Book XIV:XIX The deaths of Domitius Afer and Marcus Servilius

The deaths of two illustrious men, Domitius Afer and Marcus Servilius Nonianus, followed, who had flourished as senior officials and orators of eloquence, Afer as a pleader of causes, Servilius for his long court service, being celebrated thereafter as a historian of Roman affairs and for his refined lifestyle, more noticeable for his being Afer’s equal in intellect, but the pair being markedly different in character.

Book XIV:XX The Greek Games of AD60

In Nero’s fourth consulate (AD60), his colleague being Cornelius Cossus, a quinquennial games (the Neronia) was established in Rome, after the Greek style of contest, to varied criticism as with all new things.

It was said that Pompey had been censured by his elders too, in his case for establishing a permanent home for theatre. Before then, games had been shown with the construction of tiers of benches and a stage improvised for the occasion, and even further back people simply stood to watch, lest if provided with seats they might pass whole days in idleness.

Let the old form of these attractions be maintained, it was argued, whenever the praetor presided, and with no obligation on citizens to compete. But the nation’s morals, to which people had gradually become indifferent, were being utterly destroyed by foreign lewdness, such that whatever could corrupt, or be corrupted, was on view in Rome, and our youth were degenerating by acquiring alien tastes, into devotees of the gymnasia, idleness, and sordid affairs, at the instigation of an emperor and Senate who not only granted a licence to vice, but applied compulsion, so that the Roman nobility might be shamed on stage, by way of delivering a poem or oration.

What remained, they cried, but to strip the body bare, put on boxing gloves, and indulge in bouts of fighting, instead of armed military service. Would it serve justice better, would the panel of equestrian judges better fulfil their distinguished legal function, if they were trained to listen to soft tones and dulcet voices? Even the night hours were attuned to scandal, so that modesty had no space left, and amidst a promiscuous crowd, every abandoned creature might dare in the dark what was lusted for in the light.

Book XIV:XXI The pretext for imported novelty

It was this very licence that attracted the majority, and yet their pretexts were honestly given. Our ancestors too, they asserted, had not been averse to amusing themselves in keeping with their wealth, which was why actors were then imported from Etruria, horse-racing from Thurium (near Sybaris); and since the annexation of Achaia (146BC) and Asia Minor (133BC), more ambitious games had been mounted, yet no one in Rome born of honourable rank had descended to taking up the theatrical arts, it now being two hundred years since Lucius Mummius’ triumph, when a performance of that kind was first mounted (145BC) in the capital.

And anyway, it was more economic, they added, to house the theatre in a permanent structure, than to build one, and tear it down, each year, at enormous expense. Just as the magistrates would not find all their private resources exhausted, the populace not having the same excuse for demanding Greek style contests of them, since the cost would be borne by the State.

The victories won by orators and poets would apply the spur to genius, they claimed, nor would any judge feel obliged to turn a deaf ear to arts made reputable and pleasures made lawful. A few nights, in five whole years, were being given over to joy not wantonness; nights in which, in the blaze of the lights, nothing illicit could be hidden.

Indeed the performance in question passed off without any sign of scandal. There was not the slightest outbreak of partisanship among the audience, since the actors though restored to the stage were barred from the sacred competitions. No one carried off the prize for eloquence, as the emperor was declared the winner. The Greek dress, which many adopted throughout the festival, was immediately rendered obsolete.

Book XIV:XXII Portents and sacrilege

Meanwhile a comet blazed amongst the stars, from which the vulgar opinion arose that it portended a change of emperor. Thus, as if Nero was already dethroned, they began to question who might next be chosen. Rubellius Plautus was the name on every tongue, who, on his mother’s side, drew nobility from the Julian House. He cherished the beliefs of his ancestors, austere of character, his household chaste and secluded, and the more retiring he became due to his fears, the finer his reputation.

The rumours were increased by the interpretation, equally worthless, placed on a lightning strike. For while Nero was dining beside the Simbruine dams (at Subiaco), in his villa known as Sublaqueum (Below the Waters), the banquet was struck and the table shattered. Because the accident occurred in the area of Tibur (Tivoli), from which Plautus’ father originated, it was believed that he had been marked out by divine intent. He was favoured by many of those whose desire, and generally unrewarding ambition, it is to nurture the new and dubious.

Nero, therefore, troubled by this, composed a letter to Plautus advising him to consider the peace of the capital, and remove himself from the scandal-mongers: saying that he had family estates in Asia Minor, where he could enjoy his youth in safety, and undisturbed. Accordingly, Plautus retired there, with his wife Antistia, and a few intimate friends.

At about the same time, Nero’s desire for excess, brought him into disrepute and some danger. He had entered the source of the water that Quintus Marcius had brought to Rome (via the Aqua Marcia) in order to swim, and it was considered that by bathing there he had polluted the holy spring, and profaned the sanctity of the site. Divine anger was confirmed by a severe illness that followed.

Book XIV:XXIII Corbulo marches on Artaxata

Meanwhile Corbulo, having razed Artaxata (Artashat), thought to profit by the terror recently induced, and seize Tigranocerta, which he could destroy and so increase the enemy’s alarm, or spare, thus earning a reputation for mercy. He marched upon it, avoiding an offensive, so as not to dispel their hope of pardon, but nevertheless maintaining vigilance, knowing the facile inconstancy of a nation as slow to embrace danger as it was quick to seize the opportunity for treachery.

The barbarians, according to their nature, either met him with prayers, or abandoned their villages and fled into the wilds; while some concealed themselves and their dearest possessions in caverns. The Roman general therefore varied his tactics, extending pardon to the suppliants, and granting a swift pursuit to the fugitives, while to those who hid he was merciless, firing the exits and entrances to their caves, after blockading them with brushwood and lopped branches.

The Mardi, disciplined bands of brigands defended by a mountain barrier against invasion, harassed his march along their border; against whom Corbulo sent the Iberians, ravaging the country, and punishing the enemy’s boldness by spilling foreign blood.

Book XIV:XXIV The city of Tigranocerta surrenders

He himself and his army, despite incurring no casualties in battle, were wearied by short rations and continual effort, forced to keep starvation at bay by killing livestock. Added to this were lack of water, the hot summer and the long marches; the only mitigating factor being the general’s powers of endurance, he suffering the same privations as the common soldier, or greater.

In time they reached cultivated land, reaped the crops, and of the two forts in which the Armenians had sought refuge took one by storm and reduced the other, which had repulsed the first assault, by siege. From there Corbulo crossed into the Tauronite region, where he survived an unexpected threat. For a barbarian of rank was discovered with a weapon near Corbulo’s tent, revealing the nature of the conspiracy, his part in it, and his accomplices, under torture. The conviction and punishment of those who were plotting to commit murder under the cloak of friendship, quickly followed.

Not long afterwards, an embassy from Tigranocerta brought news that the city gates lay open, and the inhabitants were awaiting his orders: at the same time, as a token of welcome, they handed him a golden crown. He accepted it courteously, and took nothing from the city, prompting readier loyalty by leaving it intact.

Book XIV:XXV Legerda taken, and a Hyrcanian alliance

But the outpost at Legerda, which some resolute young warriors defended, was only carried with a struggle, since they not only risked a fight outside the walls, but when driven within the ramparts yielded only to siege-works and armed assault.

These victories were gained more easily since the Parthians were fully occupied by their war with Hyrcania. The Hyrcanians had sent ambassadors to the Roman emperor, seeking alliance, and as a pledge of amity pointing to their efforts in detaining Vologeses. On their return, Corbulo, to prevent their being intercepted from the enemy outposts, assigned them a full escort and conducted them to the shores of their own sea (the Caspian), from which they were able to regain their homeland while avoiding Parthian territory.

Book XIV:XXVI Tigranes VI granted Armenia

Indeed, as Tiridates was attempting to penetrate furthest Armenia by way of Media, Corbulo sent the legate Verulanus forward with the auxiliaries, and after a forced march himself compelled Tiridates to withdraw to some distance and abandon the conflict.

After ravaging the districts he found hostile to ourselves, with fire and sword, he had secured possession of Armenia, when Tigranes arrived, chosen by Nero to assume the throne (as Tigranes VI), he being of the Cappadocian royal house, and a great-grandson of King Archelaus of Cappadocia, though he had been long a hostage at Rome, and reduced to a servile submissiveness. Nor was his welcome universal, since the Arsacids remained popular with some. Nevertheless the majority, detesting Persian arrogance, preferred a king appointed by Rome.

In addition, he was given a garrison of a thousand legionaries, three allied cohorts and two cavalry squadrons, and so that he might more easily defend the new kingdom, the regions of Armenia adjoining the frontiers with Pharasmanes I of Iberia, Polemon II of Pontus, Aristobulus of Lesser Armenia, and Antiochus IV of Commagene, were ordered to obey him.

Corbulo withdrew to Syria, deprived of a governor by the death of Ummidius, and since then left to its own devices.

Book XIV:XXVII Decline of the Italian colonial towns

That same year, Laodicea on the Lycus, one of the most illustrious cities in Asia Minor, was ruined by an earthquake, but recovered from the disaster by employing its own resources without help from ourselves.

In Italy, the old town of Puteoli (Pozzuoli) acquired from Nero the rights and title of a colony. Veterans were also drafted to Tarentum (Taranto) and Antium (Anzio), yet without preventing the decline in population of those districts, the majority slipping away to the provinces where they had completed their military service; and as it was their habit not to take wives or rear families, the homes they left were bereft of heirs. It was not, indeed, as in past times when entire legions, with their tribunes, centurions, and ordered ranks of soldiers, in a spirit of unanimity and comradeship, created some new element of the State; now, strangers to one another, from diverse companies, without a leader, without mutual affection, as if suddenly gathered together from any other human occupation but their own, combined as one, more to make up the numbers than as a colony.

Book XIV:XXVIII Rulings and a banishment

The praetorian elections, usually administered by the Senate, being troubled by over-energetic canvassing, Nero restored calm by appointing the three candidates in excess of the numbers required to legionary command.

He also increased the senators’ powers, by ruling that those who appealed to the Senate from civil tribunals should risk the same deposit as those who applied to the emperor; previously the process had been free of charge and without penalty.

At the close of the year, Vibius Secundus, the Roman knight, was convicted on a charge of extortion, brought by the Mauretanians, and exiled from Italy, avoiding no heavier a sentence due to the resources of his brother, Vibius Crispus.

Book XIV:XXIX Trouble in Britain

In the consulate of Caesennius Paetus and Petronius Turpilianus (AD61), a serious reverse was sustained in Britain. As I have mentioned, the governor Aulus Didius, had only retained territory, and his successor, Veranius, having harassed the Silurians with a few minor raids, was prevented by death (AD58) from pursuing the campaign. Famous in life for great strictness, his ambitions became evident in the closing words of his last will and testament: where he added, to his extensive flattery of Nero, that if he had lived two more years, he would have laid the province at the emperor’s feet.

But it was Suetonius Paulinus who was now in charge of Britain, in military skill and by popular report, which allows none to lack rivals, a competitor to Corbulo, desirous of equalling the glory of the latter’s recovery of Armenia, by crushing the enemy.

He therefore prepared to attack the Island of Mona (Anglesey), itself densely inhabited and also a haven for refugees, flat-bottomed boats being constructed to counter the uncertain shallows. Thus the infantry were ported across, while the cavalry waded behind, or swam their horses through the deeper water.

Book XIV:XXX Destruction of the Druids

The opposing array lined the beach, a mass of arms and men, with women flitting about amongst them dressed in black, with dishevelled hair, brandishing their torches like Furies. A circle of Druids, hands raised to the heavens, pouring out dire imprecations, struck such awe into the soldiers, at the strangeness of the sight, that they exposed their motionless bodies to injury as though their limbs were paralysed.

Then, encouraged by their general, and exhorting each other not to be cowed by a host of women and fanatics, they charged with the standards, slew all before them, and enveloped the enemy in their own flames. A garrison was then imposed on the defeated, and the groves sacred to their savage cult were felled: for they believed it their duty to drench their altars in the blood of their captives, and consult their gods by the use of human entrails.

While thus engaged, news came of sudden revolt in the rest of the province.

Book XIV:XXXI Revolt of the Iceni

Prasutagus, king of the Iceni, famous for his long-lived opulence, had named the emperor heir, along with his own two daughters, thinking by such deference to keep his kingdom and household out of harm’s way.

The result was quite to the contrary, so much so that his kingdom was ravaged by centurions and his household by their slaves, as if both had been taken captive. Already his wife Boudicca (Boadicea), had felt the lash, and his daughters had been violated: all the Icenian nobility had been stripped of their family estates, and the king’s relatives were treated as servants.

At this outrage, and fearing worse to come, since they had been reduced to the status of a province, they took up arms and stirred the Trinobantes to rebellion, along with others not yet broken by servitude, who had entered into the secret plot to regain their freedom.

Their bitterest hatred was for the legionaries. Indeed fresh from their recent settlement in the colony of Camulodunum (Colchester), the Roman veterans were driving them from their homes, ejecting them from their land, styling them captives and slaves, their violence fuelled by the regular troops, with a like manner of behaving and hopes of similar licence.

Add to this that the temple raised to the divine Claudius rose to their view like a citadel of eternal domination, while those of them chosen as priests had to pour out their whole fortune, under the pretext of supporting his rites.

They found little difficulty in demolishing a colony unprotected by fortifications; a point too little allowed for by our commanders, who had paid attention to the amenities rather than what was needed.

Book XIV:XXXII Camulodunum (Colchester) destroyed

Meanwhile, the statue of Victory at Camulodunum (Colchester) fell, for no obvious reason, with its back turned as if retreating from the enemy. Their women, whipped into a frenzy, cried out that destruction was at hand, and that the foreigners’ cries had had been heard in their senate house; the theatre had resounded to their screams, and a vision of the ruined colony had been seen in the estuary of the Thames. That the sea indeed had appeared blood-red, and the ebbing tide had left behind the very images of human corpses, brought hope to the Britons and fear to the veterans: however, as Suetonius was far off, the latter sought help from the procurator, Catus Decianus.

He sent no more than two hundred men, without suitable weapons; while there was a small force of troops in the town. Relying on the protection of the temple, but impeded by those who, aware of the covert rebellion, interfered with their plans, they neither defended themselves with a ditch and rampart, nor ensured, by removing the women and the aged, that only the young men remained; behaving as incautiously when surrounded by a crowd of barbarians as if they were in the midst of peace.

Everything else was ravaged or set on fire in the assault: only the temple, where the troops were congregated, withstood a two day siege, and was afterwards stormed. Then the victorious Britons, turned to face Petilius Cerialis, legate of the Ninth, who was advancing to the rescue, routed the legion, and slaughtered the infantry to a man. Cerialis escaped to the camp, along with the cavalry, and found shelter behind its defences. The procurator, Catus, unnerved by the disaster and loathed by the provincials, whom his avarice had roused to war, crossed to Gaul.

Book XIV:XXXIII Londinium (London) and Verulamium (St Albans) follow

But Suetonius Paulinus, showing remarkable strength of mind, headed, straight through the midst of the enemy, to Londinium (London) which though not honoured with the title of colony, was nevertheless densely populated, and filled with traders and their goods.

Once there, he was uncertain whether to adopt it as his military base, but on considering the paucity of troops, and the severe enough lesson dealt Petilius’ foolhardiness, he decided to sacrifice one town to save the whole. He was inflexible regarding the weeping and lamentations of the inhabitants as they begged his help, simply giving the order to depart, while allowing them to accompany the column: all those prevented from doing so by reason of gender, the fatigue of age, or their attachment to the location, were seized by the enemy.

A similar fate overtook Verulamium (St Albans), since the barbarians, with their delight in plunder and reluctance to exert themselves, left the forts and garrison-posts alone, and sought out the site which offered the richest spoils and was hardest to defend. It is well-known that seventy thousand Roman citizens and their allies died in the afore-mentioned places. For the enemy neither captured nor sold them, nor entered into any of the other transactions of war, but hurried on the slaughter, hanging, burning, crucifying, as though punishment must follow but only after revenge had been taken in the interim.

Book XIV:XXXIV Suetonius Paulinus chooses his location for battle

Suetonius Paulinus had with him the Fourteenth legion, with a detachment of the Twentieth, and the auxiliaries from the nearest posts, making almost ten thousand armed men, as he prepared to dispense with delay, and fight a pitched battle. He selected a position with a narrow approach closed off by woodland to the rear, once sufficiently satisfied that the only enemy was in front, and that the level ground was open, without risk of ambush.

The legionaries were ranked shoulder to shoulder, the light-troops round them, with the cavalry on the wings. The British forces, however, composed of squads of foot and horse, ranged about at will, in unprecedented numbers, their spirits so high they had brought their wives with them to witness their success, placing them in wagons stationed just beyond the edge of the plain.

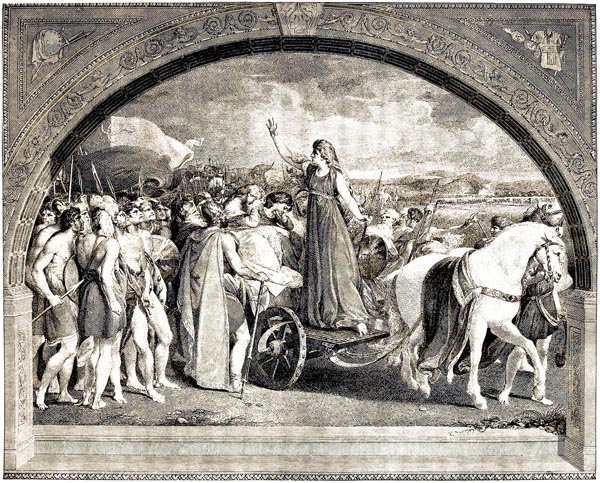

Book XIV:XXXV Boudicca (Boadicea) addresses her warriors

Boudicca (Boadicea), mounted in a chariot, her daughters before her, rode up to each clan, giving witness that though, in truth, it was customary for Britons to wage war under a female leader, she, born of highest ancestry, was taking vengeance not simply for the insult to her realm and power but, as a woman of the people, her freedom lost, her body scarred by the lash, for the shame visited on her daughters.

Roman covetousness was now such that their very bodies and neither old-age nor virginity itself remained unpolluted. Yet the gods of just revenge were present: one legion, daring to give battle, had perished; the rest were skulking in camp or seeking a way of escape. They would never endure the roar and clamour of so many thousands, much less an attack in force: let the clansmen but think of their strength under arms, of their reasons for war, and on that field let them conquer or die! Such was a woman’s destiny, let it be left to men to live as slaves!

‘Boudicca’

Character Sketches of Romance, Fiction and the Drama - Ebenezer Cobham Brewer (p270, 1892)

Internet Archive Book Images

Book XIV:XXXVI Suetonius Paulus exhorts his troops

Not even Suetonius Paulinus could be silent in the face of such danger. Though trusting in the courage of his men, he still both exhorted and entreated them to scorn the barbarians’ noise and empty threats: more women than warriors were visible out there. Unwarlike, defenceless, they would yield at once, and, so often routed, once more acknowledge the swords and courage of their conquerors.

Even amidst many legions, he cried, it was the few who decided battles: and their glory would be all the greater, in that their modest force would win fame for the whole army. Let them but engage and, their javelins once sent on their way, with shield-boss and sword let them go on piling up the dead, forgetting all thought of plunder: with victory gained all would accrue to them.

Such was the ardour following his words, so swiftly did his veteran troops, proven in many a battle, ready themselves to hurl their javelins, that Suetonius Paulus, certain of the outcome, gave the signal for battle.

Book XIV:XXXVII Defeat of the Iceni

At first the legionaries held position, with the defile as a defence, then when the enemy’s closer advance enabled them to hurl their missiles with accuracy, they ran forward in wedge formation. The auxiliaries charged in the same manner; and the cavalry, with lances extended, broke through whatever force opposed them. The remainder turned and fled, though escape was difficult, since the surrounding wagons blocked their exit.

The soldiers gave the women no quarter, and even the baggage animals were speared and added to the pile of dead. The glory won that day was brilliant and equalled our ancient victories: indeed they say that scarcely fewer than eighty thousand Britons met their deaths, with some four hundred Romans killed, and a not much greater number injured.

Boudicca (Boedicea) ended her life by taking poison. While Poenius Postumus, camp-prefect of the Second legion, learning of the success gained by the men of the Fourteenth and Twentieth, and that he had robbed his own troops of a share of the glory by disobeying his commander’s orders in contravention of the rules of the service, fell on his own sword.

Book XIV:XXXVIII The troops in Britain strengthened

The whole army was now concentrated, under canvas, ready to complete what remained of the campaign. Nero increased its strength, sending two thousand legionaries from Germany, eight auxiliary cohorts, and a thousand cavalry, upon whose arrival the Ninth legion was supplemented.

The cohorts and cavalry were stationed in new winter quarters, and the tribes which appeared neutral or hostile were harried with fire and sword. But nothing afflicted as badly as famine those who had neglected to sow their crops and, devoting old and young alike to the war, had destined our supplies for themselves.

The more impetuous of the tribes were reluctant to make peace, because Julius Classicus, sent as successor to Catus, and at loggerheads with Suetonius Paulinus, was impeding the affairs of the province with his private feuding, and had spread the view that it was best to await a new governor, who, lacking the irascibility of an opponent and the arrogance of a conqueror, might show clemency towards those who surrendered.

At the same time he spelt out to Rome that no end to the fighting could be anticipated until Suetonius Paulinus was replaced, whose defeats were due to his own perversity, his successes to good fortune.

Book XIV:XXXIX Peace achieved through moderation

Polyclitus, one of the imperial freedmen, was therefore sent to assess the situation in Britain, Nero cherishing high hopes that through Polyclitus’ influence, not only might harmony between the governor and procurator be achieved, but the rebellious spirits of the barbarians be reconciled to peace.

Polyclitus, his immense entourage having weighed heavily on Italy and Gaul, did not fail to instil dread in our troops too, once he had crossed the Channel. But to the enemy he was an object of derision, they, with the fires of liberty still burning, not yet having met with the power of freedmen, amazed that a general and his army who had fought such a war, could obey mere servants.

Nevertheless, all was reported favourably to the emperor; Suetonius Paulinus was retained in charge, but when a few vessels and the oarsmen in them ran aground and were lost, he was ordered, on the pretext of an ongoing campaign, to transfer his troops to Petronius Turpilianus, who had by now retired from the consulate.

He, by not provoking the enemy, nor being provoked, conferred the honourable name of peace on this quiet inaction.

End of the Annals Book XIV: I-XXXIX