François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXXVI: Journey to Prague 1833

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXXVI: Chapter 1: The Marie-Thérèse Infirmary

- Book XXXVI: Chapter 2: A Letter to Madame la Duchesse de Berry

- Book XXXVI: Chapter 3: Reflections and Resolutions

- Book XXXVI: Chapter 4: My journal Paris to Prague from the 14th to the 24th of May 1833 – Departure from Paris – Monsieur de Talleyrand’s carriage - Basel

- Book XXXVI: Chapter 5: The banks of the Rhine – The Rhine Falls – Moskirch – A storm

- Book XXXVI: Chapter 6: The Danube – Ulm

- Book XXXVI: Chapter 7: Blenheim – Louis XIV – The Hercynian Forest – The Barbarians – The sources of the Danube

- Book XXXVI: Chapter 8: Regensburg – Maker of Emperors – The decrease in social life the further one gets from France – Religious sentiment in Germany

- Book XXXVI: Chapter 9: Arrival at Waldmünchen – The Austrian Customs – Entry to Bohemia denied

- Book XXXVI: Chapter 10: My stay in Waldmünchen – A letter to Count Choteck – Holy Communion

- Book XXXVI: Chapter 11: A Chapel – My room at the inn – A description of Waldmünchen

- Book XXXVI: Chapter 12: A letter from Count Choteck – The peasant girl – Departure from Waldmünchen – The Austrian Customs – Entering Bohemia – The pine forest – A conversation with the moon – Pilsen – The highways of the north – The sight of Prague

Book XXXVI: Chapter 1: The Marie-Thérèse Infirmary

Paris, Rue d’Enfer, the 9th of May 1833.

BkXXXVI:Chap1:Sec1

I have brought the sequence of preceding events up to date: am I at free to resume my work? That work consists of the various parts of these Memoirs as yet incomplete. I shall have some difficulty in continuing ex abrupto (impromptu), since my mind is preoccupied with the things of the moment; I am not in a suitable state to retrieve my past from the repose in which it lies, agitated though it was when it was actually in being. I have picked up my pen to write; of what and with regard to what? I am not sure.

Casting a glance over the journal in which, for six months, I have kept an account of what I have done and what has happened to me, I see that most of the pages are headed Rue d’Enfer.

The house I live in near the city gate may be worth sixty thousand francs; but at a time of rising land prices, I bought it for much more, and have never been able to pay off the debt: there is the matter of preserving the Infirmerie de Marie-Thérèse founded through the efforts of Madame de Chateaubriand and adjacent to the property; a group of entrepreneurs proposed opening a café and building a roller-coaster on the said property, the noise hardly according with the sound of death-throes.

Am I unhappy with my sacrifices? Of course, one is always happy to aid the unfortunate; I willingly shared the little I possessed with the needy; but I am not sure my benevolent disposition amounts to a virtue at home. I am virtuous as a condemned man is who gives away what will not be his for more than an hour. In London, the victim they are going to hang sells his skin for drink; I do not sell mine, I give it to the gravediggers.

My house once bought, I have done my best to live in it; I have made it such as it is. From the drawing-room windows one’s first view is of what the English call a pleasure-ground, a proscenium formed by a lawn and banks of shrubs. Beyond this enclosure, over a retaining wall topped by white lattice fencing, is a field variously cultivated and dedicated to providing fodder for the Infirmary’s cattle. Beyond this field is another piece of ground separated from the field by another retaining wall, with a green trellis interwoven with clematis and Bengal roses; that end of my estate consists of a clump of trees, a little meadow and a poplar alley. The corner is extremely secluded: it does not smile at me as Horace’s corner did: angulus ridet. Quite the contrary, I have often wept there. The proverb says: Youth must pass. Late autumn also has several extravagances to pass through:

‘Tears and pity,

A kind of love, possessing its charms.’

My trees are of various kinds. I have planted twenty-three cedars of Lebanon and two druid oaks: they mock their master with his slender longevity, brevem dominum. An avenue, a double alley of chestnut-trees, leads from the upper to the lower garden: along the intermediate field the ground slopes steeply.

I have not selected these trees as I did at the Vallée-aux-Loups in memory of places I have visited. He who delights in memories preserves his hopes, but when one lacks children, youth, and homeland what attachment can one have to trees whose leaves, flowers and fruits are no longer mysterious symbols used to count the days of illusion? In vain they say to me: ‘You look younger’, do they think I could confuse wisdom teeth with milk teeth though? The former were given me to eat bitter bread under the monarchy of the 7th of August. Moreover my trees scarcely know if they serve as a calendar for my pleasures or as death certificates for my years; they grow each day, as I shrink: they marry themselves to those of the Foundlings enclosure and the Boulevard d’Enfer which envelop me. I see not one house; I would be less divorced from the world six hundred miles from Paris. I hear the bleating of the goats that nourish the abandoned orphans. Oh! If only I had been as they are in the arms of Saint Vincent de Paul! Born of frailty, obscure and unknown as them, I would now be some nameless workman, having nothing to discuss with mankind, not knowing why or how I came into this life, or how and why I am to leave it.

The demolition of a wall has put me in communication with the Marie-Thérèse Infirmary; I find I am simultaneously part of a monastery, a farm, an orchard and a park. In the morning I wake to the sound of the Angelus; I hear in my bed the chanting of the priests in the chapel; from my window I can see a Calvary which rises between a walnut and an elder tree: cows, chickens, pigeons, and bee-hives; the sisters of charity in their robes of dark muslin and their white cotton caps, convalescent women, and aged ecclesiastics wander among the garden’s lilacs, azaleas, calycanthuses and rhododendrons, among the rose-bushes, redcurrants, raspberries and kitchen-garden vegetables. Some of my octogenarian priests were exiles when I was: after having shared my misery with them on the lawns of Kensington, I offer them the grassy tracts of my hospice; they drag their religious age behind them like the folds of the sanctuary veil.

For companion I have a fat tabby cat, red with black transverse stripes, born in the Vatican in Raphael’s Loggia: Leo XII carried it in a section of his robe, where I spied it, enviously, when the Pontiff gave me my audiences as an Ambassador. St Peter’s successor dying, I inherited the cat without a master, as I have recounted in speaking of my Rome embassy. He is called Micetto, and nicknamed the Pope’s cat. He enjoys on that account excessive attention from pious souls. I seek to make him forget his exile, the Sistine Chapel and the sunlight of that cupola of Michelangelo’s over which he would prowl, far from the ground.

My house and the various Infirmary buildings with their chapel and Gothic sacristy have the air of a colony or a hamlet. On ceremonial days, religion, hidden away in my house, and the old monarchy hidden away in my hospital, set to marching. Processions, composed of all our invalids, preceded by the young girls of the neighbourhood, pass by with the Holy Sacrament, cross and banner, singing, beneath the trees. Madame de Chateaubriand follows them rosary in hand, proud of the participants, the object of her concern. The blackbirds flute, the warblers twitter, and the nightingales compete with the hymns. I think back to the Rogations whose rural pomp I have described: from the theory of Christianity, I passed to the practice.

My home faces west. In the evening, the crowns of trees, lit from behind, engrave their dark silhouetted indentations on the golden horizon. My youth returns at that hour; it revives those lost days which time has reduced to the insubstantiality of phantoms. When the constellations pierce the blue vault, I remember the splendours of the firmament I admired from the depths of the American forests, or the surface of the Ocean. Night is more favourable than day for a traveller’s reminiscences; she hides the landscape from him that reminds him of the place where he lives; she only allows him to see the stars, similar in aspect at different latitudes of the same hemisphere. Then he recognizes the stars he saw in such and such a country, at such and such a time; the thoughts he had, the feelings he experienced in various parts of the earth rise again, fixed to the same point in the heavens.

In the Infirmary, we only have news of the world outside at two public charity collections and to some extent on Sundays: on those days our hospice is turned into a kind of parish. The Sister Superior claims that the fine ladies come to Mass in hopes of seeing me; an industrious treasurer, she turns their curiosity into contributions: by promising to display me to them, she lures them into the dispensary; once caught in her net, they yield their money to her, willingly or unwillingly, for sugar-pills. She has me selling chocolate made here, to the profit of the invalids, as La Martinière once involved me in the flow of redcurrant syrup in which he drank to the success of his love affairs. The saintly piper also removes the used quills from Madame de Chateaubriand’s inkwell: she trades them amongst the Royalists of noble race, claiming that these precious quills wrote the superb Memoir on the Captivity of Madame la Duchesse de Berry.

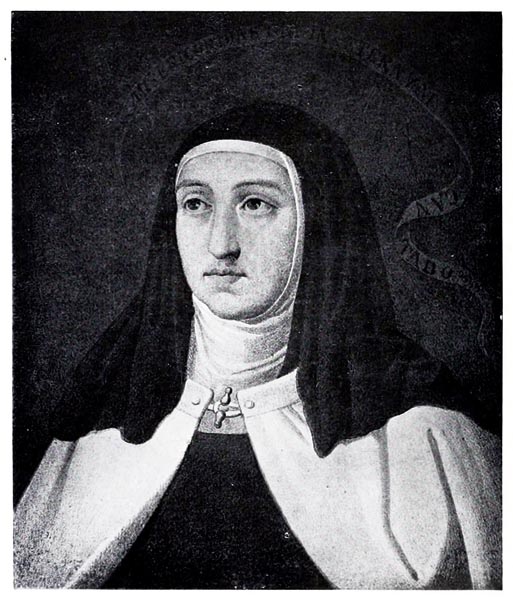

Various fine paintings of the Spanish and Italian Schools, a Virgin by Guérin, and a St Theresa, the last masterpiece of the painter of Corinne, display our attachment to the arts. As for history, we soon saw the Marquis de Favras’ sister and Madame Roland’s daughter enter our hospice: monarchy and republic entrusted us with expiating their ingratitude and nurturing their invalids.

‘St. Theresa’

Life and Death: Being an Authentic Account of the Deaths of one Hundred Celebrated Men and Women, with their Portraits - Thomas Herbert Lewin (p133, 1910)

Internet Archive Book Images

All are welcome at the Marie-Thérèse. The poor women who are obliged to leave when they have recovered their health lodge close to the Infirmary, priding themselves on falling ill again and re-entering it. Nothing proclaims it a hospital; Jews, Protestants, or Catholics, French people or foreigners receive a tactful charity’s care disguised as an act of affection: each patient thinks to have found a tender mother. I have seen a Spanish girl, as beautiful as Dorothea, the pearl of Seville, dying at sixteen of consumption, in the common dormitory, congratulating herself on her good fortune, gazing smilingly, with great black half-extinguished eyes, at a pale slim figure, that of Madame la Dauphine, asking her for news and assuring her that she would soon be well. She died that very evening, far from the mosques of Cordoba and the banks of the Guadalquivir, her native river: ‘Where are you from? – Spain. – Spain, and here!’ (Lope de Vega)

A large number of widows of Knights of Saint-Louis are regular guests; they bring with them all that remains to them, portraits of their husbands in the uniforms of Infantry Captains: a white coat, the lining red or sky-blue, hair extravagantly curled ‘à l’oiseau royal’. The portraits are hung in the attic. I cannot view that ‘regiment’ without smiling; if the former monarchy had survived, I would have added one to the number of such portraits, in some neglected corridor I would have proved a consolation to my great-nephews: ‘It’s your great-uncle François, Captain in the Navarre Regiment: he was full of spirit! He had a riddle printed in the Mercure which began with the words: ‘Take off my head’ and an ephemeral piece in the Almanach des Muses: ‘The Cry from the Heart.’

When I am weary of my garden, the plain of Montrouge replaces it. I have seen the plain alter: what have I not seen alter! Twenty-five years ago it was when travelling to Méréville, to Marais, to the Vallée-aux-Loups, I passed through the Barrière du Maine; to right and left of the road one saw only windmills, the wheels of lifting gear in the quarry pits, and the nursery created by Monsieur Cels, a former friend of Rousseau. Desnoyers built his salons of a hundred covers for the soldiers of the Imperial Guard who came to clink glasses in the intervals between successful battles, between the subjugation of kingdoms. Various small restaurants with music and dancing rose around the mills, from the Barrière de Maine to the Barrière du Montparnasse. Higher up was the Moulin Janséniste and Lauzun’s little house by way of contrast.

Near the restaurants false acacias were planted, the indigent’s shade as soda-water is the poor man’s champagne. A fairground site attracted the nomadic population of the dance-floors; a village emerged with paved streets, cabaret artists and gendarmes, Amphions and Cecrops of the police.

As the living became established here, the dead claimed their place. Not without opposition from the drinkers, a cemetery was enclosed on ground containing a ruined mill, like a hunting tower: it is there the dead each day bring the grain they have garnered; a simple wall separates the dance, the music, the nocturnal din, the noise of the moment, and the marriages of an hour, from the silence without term, the night without end and the eternal wedding.

I often go to the cemetery which is younger than I, where the maggots that feed on the dead are still alive; I read the epitaphs: let women from sixteen to twenty become death’s prey! Happy to have lived only when young! The Duchesse de Gèvres, last drop of the blood of Du Guesclin, skeleton from another age, takes her rest among the plebeian sleepers.

In this new exile, I already have old friends: Monsieur Lemoine lies here. Secretary to Monsieur de Montmorin, he was bequeathed to me by Madame de Beaumont. Every evening, when I was in Paris, he used to bring me his art of simple conversation, something which pleases me so much when united to goodness of heart and steadiness of character. My sick and weary spirit relaxes alongside a healthy and restful mind. I have left the remains of Monsieur Lemoine’s noble patroness by the banks of the Tiber.

My walks are shared between the cemetery and the boulevards that surround the Infirmary: I no longer dream there: having no future, I no longer have dreams. A stranger to the new generations, I seem to them like a powdered mendicant, quite naked; I am barely clothed now by these scraps of days, cut short by gnawing time as the herald at arms trims the tunic of an inglorious knight: I am happy to live apart. It pleases me to live a stone’s throw from the city gate, beside a highroad and always ready to depart. From the foot of the milestone, I watch the courier pass, a likeness of myself and of life: tanquam nuntius percurrens: like a messenger hurrying by.

When I was in Rome, in 1828, I conceived the idea of constructing a greenhouse and a garden house at the bottom of my hermitage in Paris; all from the proceeds of my embassy and the fragments from antiquity found in my excavations at Torre Vergata. Monsieur de Polignac arrived in the Ministry; I sacrificed a place that delighted me to my country’s freedom; fallen into poverty again, goodbye my greenhouse: fortuna vitrea est: fate is made of glass.

The wretched habit of employing paper and ink makes it impossible to stop scribbling. I took up my pen not knowing what I should write, and I have produced this description, too long by at least a third: if I had time, I would abridge it.

I must ask pardon of my friends for the bitterness of some of my thoughts. I only know how to smile with the lips; I have spleen, a physical melancholy, a true illness; whoever reads these Memoirs has seen what my fate has been. I’d barely set sail from my mother’s womb and already torments assailed me. I have voyaged from shipwreck to shipwreck; I feel a curse lies on my life, a weight too heavy for this cabin of reeds. May those I love then not think badly of me; may they forgive me, and allow my fever to ebb: between these fits, my heart is all theirs.

Book XXXVI: Chapter 2: A Letter to Madame la Duchesse de Berry

BkXXXVI:Chap2:Sec1

I was here amongst these disjointed pages, thrown pell-mell about my table, and blown away by the wind that my windows allowed to enter, when I was brought the following letter and note from Madame la Duchesse de Berry; let us enter once more into the second part of my dual life, the positive part.

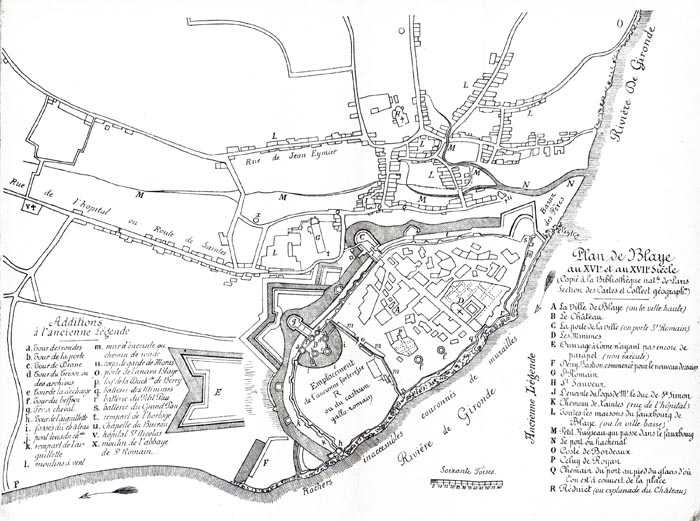

‘From the Citadel of Blaye, 7th of May 1833.

I am painfully thwarted by the refusal of the government to allow you to visit me despite having twice requested it of them. Of all the vexations without number that I am forced to experience, this is without doubt the most painful. I have so many things to say to you! So much advice to ask of you! Since I must forgo seeing you, I will at least try, using the only means left me, to tell you of the errand I wish to send you on and which you will accomplish: for I count, without reservation, on your attachment to me and your devotion to my son. I therefore charge you especially, Sir, with going to Prague and telling my relatives that if I refused to make known my secret marriage until the 22nd of February, I thought to benefit my son’s cause and show that a mother, a Bourbon, was not afraid to risk her life. I counted on revealing my marriage only on my son’s majority; but government threats, and mental torture, pushed to the furthest degree, forced me to make my declaration. In the state of ignorance I am in regarding the date at which I might be freed, after so many false hopes, it is time to give my family and the whole of Europe an explanation which might prevent injurious suppositions. I would have desired to be able to give it earlier; but an imprisonment which is absolute and the insurmountable difficulties of communicating with the outside world have prevented me until now. You will say to my family that I was married in Italy to Comte Hector Lucchese-Palli, of the Princes of Campo-Formo.

I ask you, O Monsieur de Chateaubriand, to bear to my children all my expression of tenderness for them. Be sure to tell Henri that I count, more than ever, on his efforts to become day by day worthy of the admiration and love of the French people. Tell Louise how happy I would be to embrace her and that her letters have been my sole consolation. Lay my homage at the King’s feet and offer my tender friendship to my brother-in law and my good sister-in-law. I beg them to communicate their future intentions to you. I ask you to report my family’s wishes to me wherever I may be. Enclosed by the walls of Blaye, I find consolation in having such a spokesman as Monsieur de Chateaubriand; he can, at all times, count upon my attachment.

MARIE-CAROLINE.

NOTE.

I have experienced great satisfaction at the harmony that reigns between you and Monsieur le Marquis de Latour-Maubourg, placing great value on it with regard to my son’s interests.

You may communicate the letter I have written you to Madame la Dauphine. Assure my sister-in-law that as soon as I am set at liberty I will waste no time in sending her all the papers relative to my political affairs. All my wishes would be to go to Prague as soon as I am free; but the sufferings of all kinds that I have experienced have so destroyed my health that I will be obliged to stay in Italy for some time to recover a little and avoid frightening my poor children too much with how altered I am. Study my son’s character, his qualities, his inclinations, his faults even; tell the King, Madame la Dauphine and myself what needs correcting, changing, perfecting, and make known to France what she may expect from her young King.

Through my various contacts with the Emperor of Russia, I know he has strongly welcomed repeated suggestions of marrying my son to Princess Olga. Monsieur de Choulot will give you more precise information regarding the people you will meet in Prague.

Wishing to remain French above everything, I ask you to obtain permission from the King for me to keep my title as a French Princess and my name. The mother of the King of Sardinia is always known as the Princesse de Carignan despite having married Monsieur de Montléar, to whom she gave the title of Prince. Marie-Louise, Duchess of Parma, has kept her title of Empress in marrying Count von Neipperg, and she has remained the tutor of her sons: her other children are also named Neipperg.

I beg you to leave for Prague as soon as possible, desiring more fervently than I can say that you may arrive in time for my family to learn all the details from you alone.

I would appreciate more than anything that no one may know of your departure or at least that no one may know you are carrying a letter from me, in order that my sole means of correspondence, which is so precious to me however infrequent, may not be discovered. Count Lucchesi, my husband, is descended from one of the four greatest and most ancient families of Sicily, the only remaining offshoots of the twelve companions of Tancred. His family has always been outstanding for the noblest devotion to the cause of royalty. The Prince of Campo-Franco, Lucchesi’s father, was First Gentleman of the Chamber to my father. The present King of Naples, having complete confidence in him, has placed him with his young brother the Viceroy of Sicily. I do not speak to you of their sentiments; they conform to ours at all points.

Convinced that the only way of being understood by the French is to speak to them only of honour and lead them to dream of glory, I have thought of marking the beginning of my son’s reign by bringing Belgium and France closer. Count Lucchesi has been charged by me with making initial overtures on this subject to the King of Holland and the Prince of Orange; he has contributed powerfully to making them feel welcome. I have not been fortunate enough as to complete this treaty, the object of all my wishes; but I still think it has a chance of success; before leaving the Vendée, I gave Marshal de Bourmont the authority to continue the negotiations. No one is more capable than he is of concluding them successfully, because of the esteem he enjoys in Holland.

Blaye, this 7th of May 1833.

M.-C.

Because I am uncertain of being able to write to the Marquis de Latour-Maubourg, try and see him before you leave. You may tell him all that you judge appropriate, but in the most absolute secrecy. Agree with him as to the management of the Press.’

‘Plan de Blaye’

Histoire de la Ville de Blaye Depuis sa Fondation par les Romains Jusqu'à la Captivité de la Duchese de Berry - E. Bellemer (p779, 1886)

The British Library

Book XXXVI: Chapter 3: Reflections and Resolutions

BkXXXVI:Chap3:Sec1

I was moved on reading these documents. A daughter of so many kings, this woman fallen from such a height, after having shut her ears to my advice, had the courage in her nobility to address me, and pardon me for having predicted the failure of her enterprise: her faith in me went to my very heart and honoured me. Madame de Berry had not judged ill; the very nature of that enterprise which had lost her everything had not estranged me. To play for a throne, glory, the future, destiny is no common thing: the world knows a Princess may prove a heroic mother. But that they should indulge in an abuse without example in history, that is a shameful torment inflicted on a feeble woman, alone, deprived of aid, overwhelmed by all the forces of government raised against her, it is as if they were trying to overcome some mighty power. Her own parents handing over their daughter to the ridicule of lackeys, holding her by all four limbs in order that she might give birth in public, calling on the local officials, gaolers, spies, and passers-by to watch the child emerge from their prisoner’s womb, just as France had been called on to watch the birth of her king! And which prisoner: a descendant of Henri IV! And which mother: the mother of an exiled orphan whose throne they occupied! Could one find in a penal colony a family so base born that they would dream of branding a child of theirs with such ignominy? Would it not have been nobler to murder Madame la Duchesse de Berry than make her submit to such tyrannical humiliation? Whatever leniency was shown in that cowardly business is owing to our century: whatever infamy was shown is owing to the government.

Madame la Duchesse de Berry’s letter and note are remarkable not merely for where they were written: the section concerning the re-union of Belgium and Henri V’s marriage show a mind capable of serious matters; the section concerning her family in Prague is touching. The Princess fears she will be obliged to remain in Italy to recover a little and avoid frightening her children by the change in her. What could be sadder or more melancholy! She adds: ‘I ask you, O Monsieur Chateaubriand (!) to bear to my children all my tenderness for them, etc.’

O Madame la Duchesse de Berry! What can I do for you, I, a feeble creature already half-destroyed? But how can I refuse such words as these: ‘Enclosed by the walls of Blaye, I find consolation in having such a spokesman as Monsieur de Chateaubriand; he can, at all times, count upon my attachment.’

Yes: I will leave on the last and most glorious of my embassies; I will go on behalf of the prisoner of Blaye to seek the prisoner of the Temple; I will negotiate a new family pact, bear a captive mother’s affection to her exiled children, and hand over the letters in which courage and misfortune shall present my accreditation to innocence and virtue.

Book XXXVI: Chapter 4: My journal Paris to Prague from the 14th to the 24th of May 1833 – Departure from Paris – Monsieur de Talleyrand’s carriage - Basel

BkXXXVI:Chap4:Sec1

A letter for Madame la Dauphine and a note for the two children were included in the letter addressed to me.

A coupé remained to me from my past grandeurs in which I once shone at the Court of George IV, and a travelling calash formerly constructed for the Prince de Talleyrand. I had the latter re-furbished, in order to make it fit for unusual journeying: since, by origin and custom it was hardly prepared for chasing after fallen kings. On the 14th of May, the anniversary of Henri IV’s assassination, at eight thirty in the evening, I left to seek Henri V, orphan and exile.

I was not without some concerns regarding my passport; obtained from the Foreign Office, it lacked a personal description, and was eleven months old; issued for Switzerland and Italy it had already allowed me to leave and re-enter France; various visas attested to these different occasions. I did not wish to have it renewed or to request a replacement. The police would have been alerted, all the telegraph stations would have been put in play, and my carriage, trunk and person would have been searched at every customs post. If my papers had been seized, imagine the pretexts for harassment, house search, and arrest! Perhaps even an extension to the Princess’ term of imprisonment, for it was not yet known that she had a secret means of correspondence with the outside world! It was therefore impossible for me to ask for a passport and thereby signal my departure; I trusted in my stars.

Avoiding the Frankfurt route which was too well policed, and that of Strasbourg which followed the line of telegraph stations, I took the road to Basel with Hyacinth Pilorge my secretary, who was wedded to my fortunes, and Baptiste, valet de chambre, when I was Monseigneur, and now plain valet again on the fall of His Lordship: we ascend and descend together. My cook, the famous Montmirel, resigned on my departure from government, declaring to me that he would not start up in business again except for me. He had wisely decided, after being introduced to the nature of ambassadors during the Restoration, that a defunct ambassador should return to private life; Baptiste had returned to domesticity.

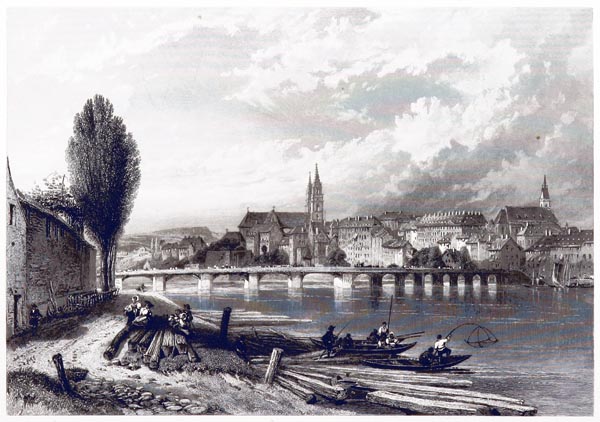

Arriving at Altkirch, the frontier post, a gendarme approached and asked for my passport. On seeing my name, he told me that he had been a captain in the Dragoon Guards, under command of my nephew Christian during the Spanish campaign of 1823. Between Altkirch and Saint-Louis I met a priest with his parishioners; they were holding a procession to ward off cockchafers, unpleasant insects that swarm during the days of July. At Saint-Louis, the customs officials, who knew me, allowed me to pass. I happily arrived at the gates of Basel, where the old drum-major awaited me who had inflicted on me un bedit garandaine d’in guart d’hire: a little quarantine for a quarter of an hour the preceding August; but there was no question of cholera and I went to lodge at The Three Kings on the banks of the Rhine; it was ten in the morning on the 17th of May.

‘Basel’

The Upper Rhine: the Scenery of its Banks, and the Manners of its People, Vol 02 - Henry Mayhew, Myles Birket Foster (p242, 1858)

The British Library

The hotel manager procured me a local servant called Schwartz, a native of Basel, to serve as my interpreter in Bohemia. He spoke German, as my good Joseph, the Milanese ironmonger, spoke Greek in Messenia when inquiring after the ruins of Sparta.

On the same day, the 17th of May, at six in the evening, I left port. Climbing into the calash, I was astounded to see the Altkirch gendarme in the midst of the crowd; I was not sure if he had been dispatched to follow me: but he had simply been escorting the French mail-sacks. I gave him a toast to his former captain.

A student approached me and threw me a note with this inscription: ‘To the 19th Century Virgil’; on it was written this amended passage from the Aeneid: Macte animo, generose puer: bless your courage, noble child. Then the coachman whipped up the horses, and I departed proud indeed of my great fame in Basel, astonished indeed to be cast as Virgil, and delighted indeed to be called child, generose puer.

Book XXXVI: Chapter 5: The banks of the Rhine – The Rhine Falls – Moskirch – A storm

BkXXXVI:Chap5:Sec1

I crossed the bridge, leaving the peasants and the bourgeois of Basel at war in the midst of their republic, fulfilling in their own manner the role they were called upon to play in the general transformation of society. I ascended the right bank of the Rhine and gazed with a certain amount of sadness at the high hills of the Canton of Basel. The exile I had come to seek in the Alps the year before seemed to me a pleasant way to end my life, a sweeter fate than this business of empire on which I was re-engaged. Did I nourish the slightest hope for Madame la Duchesse de Berry or her little boy? No: moreover I was convinced that, despite my recent service, I would find no friends in Prague. Those who had sworn oaths to Louis-Philippe, and who praised the fatal decrees regardless, were more agreeable to Charles X than I who had never perjured myself. It is far too much for royalty for one to have been right twice running: royalty prefers flattering treason to cool devotion. So I was off to Prague as the Sicilian soldier, hung at Paris in the time of the League, went to the gallows: the Neopolitans’ confessor sought to put courage in his belly and cheered him on the way with: ‘Allegramente! Allegramente! Merrily! Merrily! So my thoughts wandered while the horses carried me onwards; but when I thought of the misfortunes of Henri V’s mother, I reproached myself for my regrets.

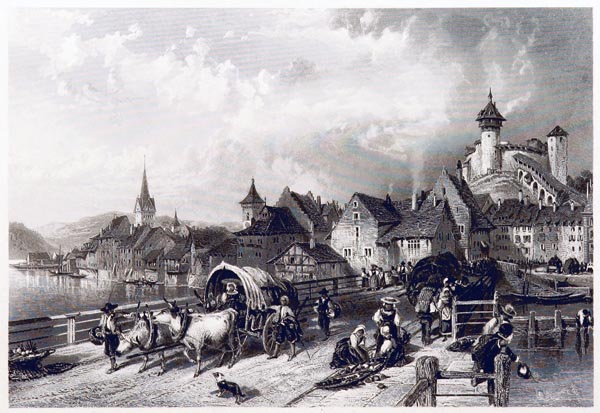

The banks of the Rhine fleeing behind my carriage provided a pleasant distraction for me: when one sees a country from a window, though one may be dreaming of other things, a reflection of the image before the eyes still enters the thoughts. We bowled along through the meadows painted with May flowers; there was fresh green on the orchards, woods, and hedges. Horses, donkeys, cows, sheep, pigs, cats and dogs, chickens and pigeons, geese and turkeys roamed the fields along with their masters. The Rhine, a warrior’s river, seemed happy in the midst of this pastoral scene, like an old soldier dropping in to visit his neighbours.

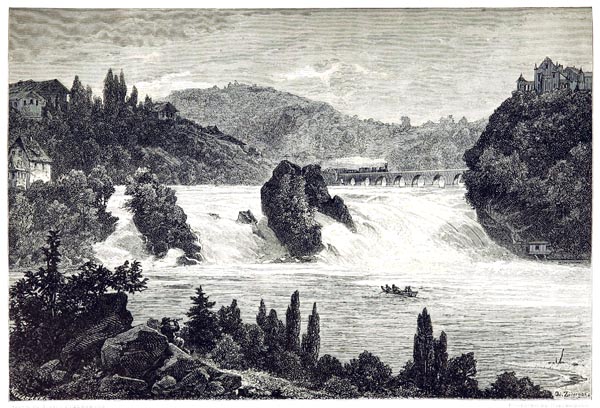

‘Schaffhausen’

The Upper Rhine: the Scenery of its Banks, and the Manners of its People, Vol 02 - Henry Mayhew, Myles Birket Foster (p346, 1858)

The British Library

On the next day, the 18th of May, before arriving at Schaffhausen, I was guided to the Rhine Falls; I stole a few moments from the fall of kings to consider its symbolism. It would have been better for me to have ended my days in the castle which overlooks the chasm. Since I had set Atala’s not-yet-realised dream at Niagara, since at Tivoli I had met with another dream already vanished from the earth, who knows whether I might not have found, in the tower by the Rhine Falls, a more lovely vision still, wandering its banks long ago, which might have consoled me for all the shades I have lost!

‘Falls of the Rhine at Schaffhausen’

Switzerland: its Scenery and People - Theodor Gsell-Fels (p469, 1881)

The British Library

From Schaffhausen I continued my route towards Ulm. The countryside displays cultivated basins into which wooded hillocks, separated one from another, plunge their feet. In the woods which were being harvested at that time, there were oaks to be seen, some felled, others standing; the former lying on the ground stripped, their trunks and branches white and naked like the skeletons of some strange creature; the latter bearing the fresh verdure of spring on hairy boughs garnished with black moss: they united, in a way never seen among human beings, the dual beauty of age and youth..

In the fir plantations of the plain, clearings had left empty spaces; the land had been converted to meadows. These grassy racecourses amidst the slate-grey woods have something both smiling and serious about them, and are reminiscent of the New World savannahs. Yet the huts still have a Swiss character; the hamlets and the inns are distinguished by that delightful neatness unknown in our country.

Halting for dinner, between six and seven in the evening at Moskirch, I mused at the window of my inn: cattle were drinking at a fountain, and a heifer leapt and frolicked like a deer. Everywhere where animals are treated well, they are happy and fond of man. In Germany and England they do not strike horses, they do not abuse them; the creatures accustom themselves to being harnessed; they move and halt at the least utterance, the slightest twitch of the reins. The French are the most inhuman of nations: have you seen our coachmen hitching up their horses? They drive them to the shafts by kicking them in the flanks with their boots, and with blows from their whip-handles to the head, bruising their mouths with the bit to drag them backwards, accompanying the display with curses, shouts and insults aimed at the poor animal. All in all, they force the beasts to bear burdens which exceed their strength, and slash their hides by lashing them with the whip to make them go; a Gallic ferocity has remained with us: it is merely hidden by our silk stockings and cravats.

I was not the only one gaping; the women were doing as much at the windows of their houses. I am often asked as I pass through unknown hamlets: ‘Would you like to live here?’ I always reply: ‘Why not?’ Who, during the madcap days of his youth has not said with the troubadour Pierre Vidal:

‘Don n’ai mais d’un pauc cordo

Que na Raymbauda me do,

Quel reys Richartz ab Peitieus

Ni ab Tors ni ab Angieus.

Richer am I with a ribbon though

Given me by the sweet Raimbaude

Than King Richard with Poitiers

Or with Tours, or with Angers.’

Subjects for poetry exist everywhere; pleasure and pain exist in every place; had not those women of Moskirch gazing at the sky or at my carriage, gazing at me or gazing at nothing, joys and sorrows, affairs of the heart, fortune, or family, just as they have in Paris? I would have been far away in the depths of my neighbours’ histories, if dinner had not been announced poetically to the sound of a thunderclap: it was a lot of noise for such a small matter.

Book XXXVI: Chapter 6: The Danube – Ulm

19th of May, 1833.

BkXXXVI:Chap6:Sec1

At ten in the evening, I clambered into my vehicle; I slept to the patter of rain on the hood of my calash. The sound of my coachman’s little horn woke me. I heard the murmuring of a river I could not see. We had arrived at the gate of a town; the gate opened; and someone enquired about my passport and my luggage. We were entering the vast empire of His Majesty the King of Württemberg. I saluted the memory of Grand-Duchess Hélène, a graceful and delicate flower now shut in the greenhouses of the Volga. There was a day when I understood the prize of high rank and fortune: it was at the reception I gave for the young Princess of Russia in the gardens of the Villa Medici that I realised how the magic of the sky, charm of place, and the prestige of beauty and power could intoxicate; I imagined myself to be at once Torquato Tasso and Alfonso d’Este; I was worth more than the prince, less than the poet; Hélène was more beautiful than Leonora. As representative of the heir of Francis I and Louis XIV, I dreamt of being King of France.

No one searched me, here: though I had nothing against the rights of sovereigns, I who recognized those of a young monarch when sovereigns themselves no longer recognized them. The vulgarity, the modernity of the customs officer and passport contrasted with the storm, the Gothic gateway, the sound of the horn and the noise of the torrent.

Instead of a lady in distress whom I was prepared to rescue, I found, on leaving the town, an old fellow who, raising a lantern in his left hand to the level of his grey head, and holding out his right hand to Schwartz sitting on the coachman’s seat, opened his mouth like the jaws of a pike caught on a hook, and demanded six kreutzers: Baptiste, ill and wet, could not prevent himself laughing.

And this torrent I had just crossed, what was it? I asked the coachman, who shouted back: ‘Donau (the Danube).’ Another famous river which I had passed over without knowing it, as I lit without knowing it on the site of the oleanders of the Eurotas! What use has it been to me to drink the waters of the Mississippi, Po, Tiber, Cephisus, Hermus, Jordan, Nile, Guadalquivir, Tagus, Ebro, Rhine, Spree, Seine, and Thames and a thousand other rivers celebrated or obscure? Unknown, they have failed to grant me their peace; renowned, they have not communicated to me their glory: they can only say they have seen me pass by as their own banks watch the waves pass.

I arrived quite early, on Sunday the 19th of May, at Ulm, having traversed Moreau’s and Bonaparte’s theatres of war.

Hyacinthe, a member of the Legion of Honour, wore his ribbon: that decoration brought us incredible respect. Having only a little flower in my buttonhole, as is my custom, I passed, before anyone heard my name, as a mysterious being: my Mamelukes, at Cairo, wished me, whether I would or no, to be one of Napoleon’s generals disguised as a scholar; they refused to give up the idea and waited hour after hour for me to noose Egypt in the belt of my caftan.

Yet it is among the nations whose villages we have burnt and whose fields we have ravaged that such sentiments exist. I enjoyed the glory; if we had done Germany nothing but good would they have missed us so? Inexplicable human nature!

The evils of war are forgotten: we have left the flame of life alive in the soil we have conquered. That inert mass once activated continues to ferment, because intellect is working there. Travelling today one notices that the people are alert, knapsacks on their backs; ready to leave, they seem to be waiting for us to head up the column. A Frenchman is always taken for an aide-de-camp bringing the order to march.

Ulm is a tidy little town with no particular character; its ruined ramparts have been converted into kitchen gardens and walks, which is what happens to all ramparts. Their fate is somewhat similar to that of military men; soldiers bear arms in their youth; invalided out, they turn into gardeners.

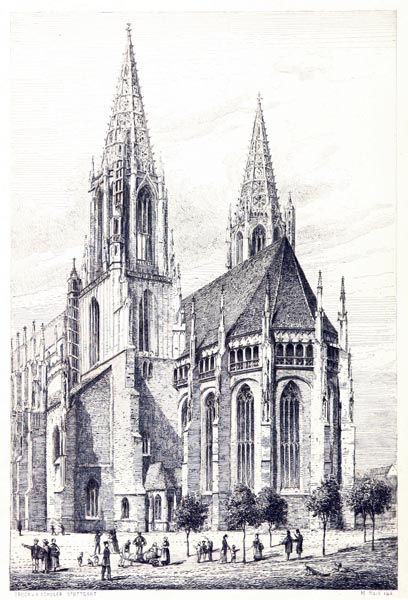

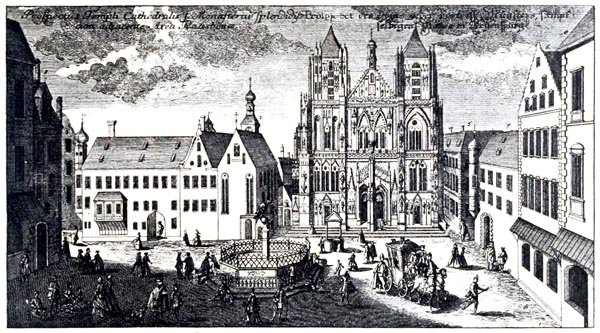

I went to look at the Cathedral, a Gothic vessel with an elevated spire. The side aisles are split into narrow double vaults, supported by a single row of pillars, such that the interior of the edifice smacks of both cathedral and basilica.

‘Münster in Ulm’

Ulm und sein Münster. Festschrift zur Erinnerung an den 30 Juni 1377 - Friedrich Pressel (p8, 1877)

The British Library

The pulpit has an elegant steeple for a dais, tapering at the top like a mitre; the interior of this steeple is composed of a central core around which winds a helical vault with stone filigree. Symmetrical needles piercing the exterior seemed to have been designed to bear candles; they illuminate this tiara when the Pontiff preaches on feast days. Instead of the officiating priests I saw little birds hopping about in this granite foliage; they celebrated the Word which gave them voice and wings on the fifth day of Creation.

The nave was deserted; in the apse of the church two separate groups of boys and girls were receiving instruction.

The Reformation (as I have already said) was wrong to display itself among the Catholic monuments it invaded; there it is mean and ashamed. Those high porticos demand numerous clergy, solemn pomp, hymns, paintings, ornaments, silken veils, draperies, lace, silver, gold, lamps, flowers and altar incense. Protestantism would have said indeed that it had returned to primitive Christianity, the Gothic churches reply that it has disowned its ancestors: the Christian architects of these marvels were not the children of Luther and Calvin.

Book XXXVI: Chapter 7: Blenheim – Louis XIV – The Hercynian Forest – The Barbarians – The sources of the Danube

19th of May, 1833.

BkXXXVI:Chap7:Sec1

On the 19th of May, at midday, I left Ulm. At Dillingen there was a lack of horses. I waited for an hour in the main street, having for recreation a view of a stork’s nest planted on a chimney as if on an Athenian minaret; a multitude of sparrows had insolently made their nests in the bed of this peaceable queen with the long neck. Below the stork, a lady, resident on the first floor, gazed at the passers-by with the gloom of a barely concealed envy, below the lady was a wooden saint in a niche. The saint will be hurled from his niche onto the pavement, the lady from her window into the tomb: and the stork? She will fly away: thus the three stories will end.

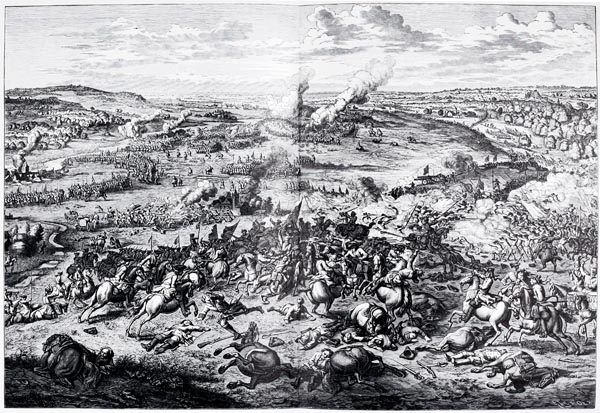

Between Dillingen and Donauwörth, you cross the battlefield of Blenheim. The tread of Moreau’s armies over the same soil has not effaced those of Louis XIV; the Great King’s defeat overshadows in this country the success of the Grand Emperor.

‘The Battle of Höchstädt, 13th August 1704’

The History of the World; a Survey of a Man's Record - Hans Ferdinand Helmolt, Viscount James Bryce (p591, 1902)

Internet Archive Book Images

The coachman who drove me was from Blenheim: arriving at the top of the village he sounded his horn: perhaps he was announcing his passage to the peasant-girl he loved; she would have trembled with joy in the midst of the very fields where twenty-seven French battalions and twelve squadrons were taken prisoner, where the Navarre Regiment, whose uniform I once had the honour of wearing, buried its standards to the mournful sound of trumpets: these are the commonplaces of the succeeding centuries. In 1793 the Republic took back from the church at Blenheim the flags torn from the Monarchy in 1704: she avenged royalty and killed a king; she culled the head of Louis XVI, but would allow France alone to rip apart the white banner.

Nothing reveals Louis XIV’s grandeur more than discovering a token of him in the depths of the ravines cut by the torrent of Napoleonic victories. That monarch’s conquests left our country with borders that we still retain. The Brienne student, to whom the Legitimacy gave a sword, locked Europe in his ante-chamber for a moment; but she escaped: Henri IV’s grandson placed that very Europe at France’s feet; there she remains. That does not mean I seek to compare Napoleon to Louis XIV: men of diverse destinies, they belonged to unlike centuries, to different nations; the one perfected an era, the other created a world. One can say of Napoleon what Montaigne said of Caesar: ‘I forgive Victory her inability to free herself of him.’

The unworthy tapestries of Blenheim House, which I viewed with Peltier, represent Marshal Tallart doffing his hat to the Duke of Marlborough, who postures like Rodomont. Tallart nevertheless remained the old lion’s favourite: a prisoner in London, he conquered, to Queen Anne’s mind, Marlborough who had beaten him at Blenheim, and died a member of the Académie des Sciences: according to Saint-Simon: ‘He was a man of average height with vigilant eyes, full of fire and spirit, but endlessly troubled by the demon of his ambition.’

I wrote history in my calash: why not? Caesar certainly wrote in his litter; and if he won the battles he tells of, I did not lose those of which I speak.

From Dillingen to Donauwörth there is a rich plain with varying levels where fields of corn mingle with meadows: you approach and retreat from the Danube according to the curves of the road and the windings of the river. At this altitude the waters of the Danube are as yellow as those of the Tiber.

You have scarcely left one village before you see another; clean and welcoming; often the house walls are decorated with frescoes. A certain Italianate character becomes evident the nearer you approach Austria: the dweller by the Danube is no longer a peasant.

‘His chin to bushy beard gives welcome:

And his whole hairy person’s

The image of a bear, but badly groomed.’

But the Italian skies are lacking here: the sun is pale and low; these market towns so thickly seeded are not the little towns of the Romagna brooding over the artistic masterpieces they hide; there you scratch the earth, and your labour produces, like a blade of wheat, some marvel from an ancient chisel.

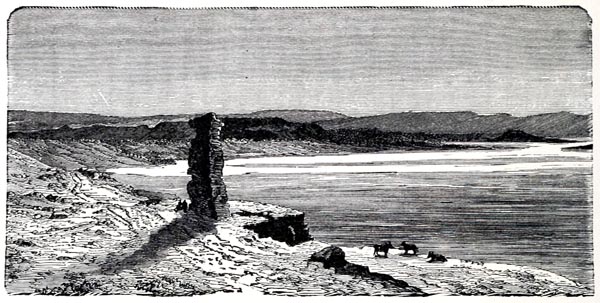

At Donauwörth, I regretted arriving too late in the evening to enjoy the fine view of the Danube. On Monday the 20th, the countryside appeared the same; yet the soil became less fertile, and the peasants seemed poorer. Pine woods and hills appeared again. The Hercynian Forest began here; the trees of which Pliny has left us a singular description were felled by the generations now buried beside the ancient trees.

‘The Danube at the Bridge of Trajan’

History of Rome and of the Roman people, from its Origin to the Invasion of the Barbarians - Victor Duruy (p323, 1882)

Internet Archive Book Images

When Trajan threw a bridge across the Danube, Italy heard for the first time a name so fatal to the ancient world, that of the Goths. The path lay open to the savage multitudes who marched to sack Rome. Attila and his Huns built their wooden palaces to match the Coliseum, on the banks of this river that rivalled the Rhine, and like them was an enemy of the Tiber. Alaric’s hordes crossed the Danube in 396 to overthrow the civilisation of the Greek empire, at the same spot where the Russians crossed it in 1828 with the object of overthrowing the barbarian empire squatting amid the ruins of Greece. Would Trajan have imagined that a new kind of civilisation would establish itself on the far side of the Alps, within the confines of the river he had almost discovered? Born in the Black Forest, the Danube flows on to vanish into the Black Sea, Where is its principal source? In the courtyard of a German Baron who employs the naiad to wash his laundry. A geographer having been ill-advised enough as to deny the fact, the gentleman proprietor started proceedings against him. Judgement was given that the source of the Danube was in the aforesaid courtyard, and was not known to be elsewhere. How many centuries it has taken to progress from Ptolemy’s errors to this important truth! Tacitus has the Danube descend from Mount Abnoba, montis Abnobae. But the chiefs of the Hermunduri, Cherusci, Marcomani and Quadi tribes, who are the authorities on which Roman history depends, were not as convinced as my German baron. Eudore did not know as much, when I had him voyage to the mouths of the Ister, to which the Euxine, according to Racine, would carry Mithidrates in two days. ‘Having crossed the Ister near its mouth, I discovered a stone tomb on which a laurel grew. I pulled away the plants which covered a row of Latin letters, and soon I was able to read this first line of the elegies of an unfortunate poet:

‘Little book, you’ll go to Rome, and go to Rome without me.’

The Danube, in losing its solitariness, has seen evils inseparable from society take place along its banks: plague, famine, fire, the sacking of towns, wars, and the endless divisions arising from passion or human error.

‘We’ve seen before, Danube, the inconstant,

Which serves, now Catholic now Protestant,

Both Rome and Luther with its wave,

Yet later sets at naught the Lutheran,

and likewise sets at naught the Roman,

Ending at last its wandering way

By even failing to be Christian..

Book XXXVI: Chapter 8: Regensburg – Maker of Emperors – The decrease in social life the further one gets from France – Religious sentiment in Germany

BkXXXVI:Chap8:Sec1

After Donauwörth one reaches Burkheim and Neuburg. At lunch, in Ingolstadt, I was served venison: it is a great pity to eat the flesh of so delightful a creature as the deer. I have always read with horror the description of the feast at the installation of George Neville, Archbishop of York, in 1466: four hundred swans were roasted, as a choir, singing their own funeral hymn! There was also a matter of three hundred and four porkers: I can well believe it!

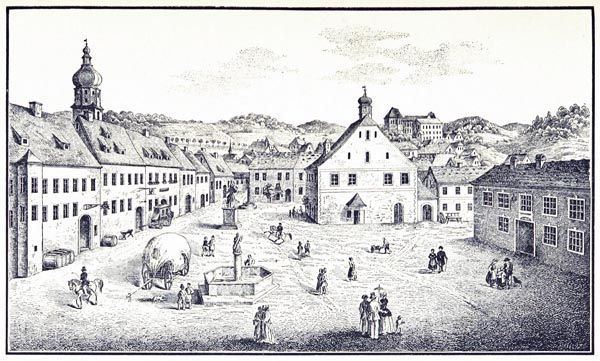

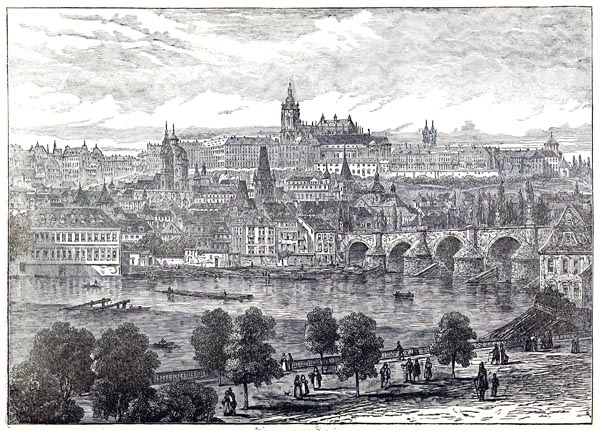

On arriving via Donauwörth, Regensburg, which we call Ratisbon, offers a pleasant aspect. Two o’clock struck, on the 20th, as I arrived at the post house. While the horses were being hitched, which always takes a long time in Germany, I entered a neighbouring church called the Alte Kapelle, newly whitened and gilded. Eight old priests in black, with white hair, were singing Vespers; I once prayed in a chapel in Tivoli for a man who himself prayed at my side; in one of the cisterns at Carthage I offered vows to Saint Louis, who died not far from Utica, more of a philosopher than Cato, more sincere than Hannibal, more pious than Aeneas: in the chapel at Ratisbon, I thought of recommending to Heaven the young king I came to seek; but I feared God’s wrath too greatly to solicit a crown; I begged the dispenser of all grace to grant the orphan happiness, and make him disdainful of power.

I hastened from the Old Chapel to the Cathedral. Smaller than that of Ulm, it is more religious in feeling and finer in style. Its stained glass shrouds it in that darkness proper to meditation. The white chapel better suited my wishes on behalf of the innocent Henri; the sombre basilica filled me with emotion for my former king, Charles.

‘Cathedral and Cathedral Square of Regensburg’

Das Fürstliche Haus Thurn und Taxis in Regensburg - Johannes Baptist Mehler (p100, 1898)

Internet Archive Book Images

I was unmoved by the mansion in which they once elected Emperors, which at least proves that they created elected sovereigns, even sovereigns whom they brought to justice. The eighteenth clause of Charlemagne’s will reads: ‘If any of our grandsons, living or yet to be born, are accused, let it be ordained that no one shave their head, blind them, cut off a limb, or condemn them to death without proper discussion and investigation.’ I forget which deposed German Emperor demanded sovereignty only of a vineyard which he was fond of.

At Ratisbon, once the maker of sovereigns, they often minted emperors of low estate; that commerce has lapsed: one of Bonaparte’s battles and a princely Primate, dull sycophant of our universal policeman, were unable to resuscitate the dying city. The citizens of Regensburg dress like Parisians and as dirty have no distinguishing feature. The city, with no great number of inhabitants, is gloomy; weeds and thistles besiege its suburbs: they will soon have raised their plumes and lances above its defences. Kepler who, as Copernicus did, made the earth revolve rests forever in Ratisbon.

We left by way of the bridge on the road to Prague, a bridge much praised and very ugly. Leaving the Danube Basin, you climb the escarpments. Kirn, the first relay station, is perched on a rough slope, at the summit of which, through rain-filled clouds, I saw dreary hills and pale valleys. The peasants are of a different appearance; the children, sallow and swollen, look ill.

From Kirn to Waldmünchen the barrenness of the countryside increases: hardly any hamlets; only pine-wood cabins, bonded with clay, as in the poorest Alpine passes.

France is the heart of Europe; the further one travels from it the more social life diminishes; you could estimate the distance you are from Paris by the greater or lesser languor of the region in which you are staying. In Spain and Italy the diminution of movement and the progress of death are less obvious: in the former country another people, another society, of Christian Arabs attends to you; in the latter the charm of the climate and the arts, the enchantment of love and ruins, prevents the weather feeling oppressive. In Austria and Prussia the military yoke weighs on your mind, as the darkened sky weighs on your head; something warns you that you cannot write, or speak, or think freely; that you must eliminate the noblest part of your being, and leave the highest human faculties idle, as a useless gift of the divinity. The arts and the beauty of nature fail to while away your hours, and it only remains for you to plunge into gross debauchery or into those speculative studies that the Germans enjoy. For a Frenchman, at least for me, that way of life is impossible; without nobility, I cannot comprehend existence, which is difficult enough to comprehend with all the seductions of liberty, glory and youth.

Yet one thing charms me about the German people, their religious sentiments. If I were not too tired, I would quit the inn at Nittenau where I am pencilling this journal; I would go this evening and pray with the men, women and children whom the sound of bells summons to church. That congregation, seeing me on my knees among them, would welcome me by virtue of our mutual faith. When will the day ever come on which philosophers in their temple will bless a philosopher arriving by coach, and offer up a similar prayer, with that stranger, to a God about whom all philosophers are in disagreement? The priest’s rosary is more certain: I will hold to it.

Book XXXVI: Chapter 9: Arrival at Waldmünchen – The Austrian Customs – Entry to Bohemia denied

BkXXXVI:Chap9:Sec1

Waldmünchen, at which I arrived on the morning of Tuesday the 21st of May, is the last village in Bavaria this side of Bohemia. I congratulated myself on being able to fulfil my mission promptly; I was no more than a hundred and fifty miles from Prague. I plunged myself into icy water, I washed at a spring, like an Ambassador preparing for a triumphal entry; I left and a few miles from Waldmünchen I approached the Austrian Customs, full of confidence. A lowered barrier closed off the road; I clamber down with Hyacinthe whose red ribbon blazes. A young customs officer, armed with a rifle, leads us to the ground floor of a house, and into a vaulted chamber. There a fat old German customs officer-in-chief sits at his desk as though at a tribunal; with red hair, red moustache, thick slanted eyebrows over two half-open greenish eyes, and a nasty look about him; a blend of Viennese police spy and Bohemian smuggler.

He takes our passports without saying a word; the young customs officer timidly brings me a chair, while his chief, before whom he trembles, examines the passports. I do not sit down and I go and look at the pistols hanging on a wall and a carbine placed in a corner of the room; it recalls the rifle which the Agha of the Isthmus of Corinth fires at the Greek peasant. After a five minute silence, the Austrian barks out a few words which my interpreter from Basle translates thus: ‘You cannot enter.’ What, I cannot enter, and why?

An explanation commences:

‘Your signature is not on the passport – My passport is a Foreign Office passport. – Your passport is out of date. – It has no year on it; it is legally valid. – It has not been stamped by the Austrian Ambassador in Paris. – You are wrong, it has. – The stamp is not embossed. – A lapse on the part of the Embassy; you can see elsewhere the visas issued by other foreign legations. I have just traversed the Canton of Basle, the Grand-Duchy of Baden, the Kingdom of Württemberg, and the whole of Bavaria, without the slightest difficulty. At the simple declaration of my name, no one even opened my passport. – Are you a public person? – I have been a Minister of France, Ambassador to His Very Christian Majesty to Berlin, London and Rome. I am known personally to your sovereign and Prince von Metternich. – You cannot enter. – Do you wish me to deposit a guarantee? Do you wish to grant me an escort who will answer for me? – You cannot enter. – May I send a courier to the Government of Bohemia? – As you wish.’

Patience failed me; I began to wish the customs officer to the devil. As ambassador of a reigning king, it would have mattered little if I had lost a few hours; but as ambassador of a Princess in chains, I considered myself disloyal to misfortune, a traitor to my captive sovereign.

The man kept writing: the interpreter from Basel had not translated my monologue, but there are a few French words that our soldiers have taught the Austrians that they have not forgotten. I said to the interpreter: ‘Explain to him that I am going to Prague to offer my homage to the King of France.’ The customs man, without interrupting his scribbling, replied: ‘To Austria Charles X is not King of France.’ I replied: ‘He is to me.’ These words spoken to Cerberus appeared to have some effect; he looked me up and down. I thought that the lengthy script might finally result in a satisfactory visa. He scribbled something else on Hyacinthe’s passport, and gave the lot to the interpreter. It transpired that the visa was an explanation of the reasons why I was not allowed to continue my journey, such that not only was it impossible for me to proceed to Prague, but my passport was marked invalid for anywhere else I might present myself. I climbed back into the calash, and told the coachman: ‘To Waldmünchen.’

Book XXXVI: Chapter 10: My stay in Waldmünchen – A letter to Count Choteck – Holy Communion

27th of May, 1833.

BkXXXVI:Chap10:Sec1

My return surprised the innkeeper not a whit. He spoke a little French, he told me that a similar thing had happened before; foreigners had been obliged to stop at Waldmünchen and send their passports to Munich to be stamped with a visa by the Austrian Legation. My host, a very fine man, who was the postmaster, undertook to transmit a letter, a copy of which follows, to the Supreme Burgrave of Bohemia.

‘Waldmünchen, the 21st of May 1833.

Monsieur le Gouverneur,

Having the honour to be known personally to His Majesty the Emperor of Austria and Prince von Metternich, I thought I would be able to travel in the Austrian States with a passport, which having no year of expiry is still legally valid and has been stamped by the Austrian Ambassador in Paris with visas for Switzerland and Italy. Indeed, Monsieur le Comte, I have crossed Germany and my name has sufficed to allow me through. Yet this morning the head of the Austrian customs post at Haselbach did not consider himself authorised to be so obliging, for the reasons spelled out in his visa on my enclosed passport, and on that of Monsieur Pilorge, my secretary. To my great regret, he has forced me to return to Waldmünchen where I await your wishes. I dare to hope Monsieur le Comte that you will resolve the little difficulty which detains me, by sending me, via the courier whom I have the honour to send you, the necessary permit for me to travel to Prague and from there to Vienna.

I am with the deepest consideration, Monsieur le Gouverneur, your very humble and obedient servant.

CHATEAUBRIAND.

Monsieur le Comte, pardon the liberty I am taking of adding an open message for Monsieur le Duc de Blacas.’

A degree of pride is apparent in this letter: I felt hurt; I was as humiliated as Cicero when, on returning in triumph from his Governorship of Asia, his friends asked him whether he had come from Baiae or his house at Tusculum. What! My name, which had flown from Pole to Pole, had not reached the ears of a customs officer in the mountains of Haselbach, a fact rendered all the more cruel given my success in Basel! In Bavaria, I had been saluted as Monseigneur or Your Excellency; a Bavarian officer, in the inn at Waldmünchen, said loudly that my name required no visa from the Austrian Ambassador. This was a great consolation, I agree, but ultimately the sad truth remained: there existed on this earth a man who had never heard my name.

Yet who was to know whether the Haselbach customs officer actually knew of me! The police of all countries work hand in glove! A politician who neither approves nor admires the Treaties of Vienna, a Frenchman who loves only liberty and the honour of France, and who remains loyal to fallen greatness, might well be on the index in Vienna. What noble vengeance to handle Monsieur de Chateaubriand like one of those travelling clerks so suspicious to agents! What sweet satisfaction to treat an envoy, entrusted with treacherously bearing greetings from a captive mother to her exiled child, as a vagabond whose papers are not in order!

The courier left Waldmünchen on the 21st, at eleven in the morning; I calculated that he might return by twelve-fifteen on the next day but one, the 23rd; but my imagination was working vigorously: What would become of my message? If the Governor was strong-minded and a student of life, he would send the permit; if he was a timid man lacking in spirit he would reply that my request was not within his jurisdiction, and that he was obliged to refer it to Vienna. This little incident might both please and displease Prince von Metternich at one and the same time. I knew how he feared the Press; I had seen at Verona how he left the most important discussions to shut himself up all distraught with Monsieur de Gentz, to work on an article replying to the Constitutionnel or to the Débats. How many days would pass before the Imperial orders were transmitted? What would become of me? How anxious would it make my Paris friends? When the news leaked out, what would the papers not make of it? What extravagances would they not churn out? Equally, would Monsieur de Blacas be happy to see me in Prague? Would Monsieur de Damas not believe I came to displace him? Would Cardinal de Latil be at all concerned? Might that triumvirate not profit from this misfortune by having the gates closed to me rather than opened? Nothing easier: one word in the Governor’s ear, a word I would never know about, would suffice.

And what if the courier returned empty-handed? What if the package were lost? What if the Supreme Burgrave judged it inappropriate to reply to me? What if he were absent? What if no one dared to act on his behalf? What would become of my passport? Where could I win recognition? Munich? Vienna? What post station would grant me horses? I would be imprisoned in Waldmünchen.

These were the dragons that flew through my mind; I thought the more of my separation from all I held dear: I had too little time left to live to waste that little. Horace says: ‘Carpe diem: seize the day.’ A counsel of pleasure at twenty, it is a counsel of commonsense at my age.

Weary of chewing over all these options in my mind, I suddenly heard the noise of a crowd outside; my inn was in the village square. Through the window I saw a priest bearing the last sacrament to a dying man. What did the affairs of kings, their servants, or the world matter to the dying? Everyone left their work and followed the priest; young girls, old women, children, mothers with infants in arms, repeated the prayers for those in their death throes. Arriving at the dying man’s door, the priest gave the benediction with the viaticum. His assistants fell to their knees, making the sign of the cross and bowing their heads. The passport to eternity will not be disregarded by He who distributes the bread and opens the inn to the traveller.

‘Marktplatz zu Waldmünchen 1850’

Geschichte der Oberpfälzischen Grenzstadt Waldmünchen - Franz Xaver Lommer (p123, 1888)

The British Library

Book XXXVI: Chapter 11: A Chapel – My room at the inn – A description of Waldmünchen

21st of May, 1833.

BkXXXVI:Chap11:Sec1

Though I had been seven days without sleep, I could not stay in my room; after barely an hour, leaving the village in the direction of Ratisbon I noticed a white chapel, to the right, in the midst of a wheat field; I directed my steps there. The door was shut; through a slanting window an altar with a cross was visible. The date the sanctuary had been built, 1830, was written over the doorway; a monarchy was overthrown in Paris and a chapel constructed at Waldmünchen. Three banished generations had been about to enter exile a hundred and fifty miles from this new chapel erected to a crucified king. Millions of events are played out at the same moment: what then of the Negro sleeping beneath a palm tree on the banks of the Niger, the white man falling at the same instant to a dagger-blow on the banks of the Tiber? What of he who weeps in Asia or he who laughs in Europe? What of the mason who built this chapel, the Bavarian priest who exalted Christ in 1830, and the demolisher of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois, he who pulled down the cross in 1830? Events only matter to those who suffer or profit from them; they are a matter of indifference to those who know nothing of them, or those they do not touch. Some race of shepherds, of Abruzzo, without descending from the mountains, has seen the Carthaginians, the Romans, the Goths, the generations of the Middle Ages, and the men of the present age pass by. That race has never merged with the successive inhabitants of the valley, and only religion has ascended to them.

‘Waldmünchen im Schwedenkrieg’

Geschichte der Oberpfälzischen Grenzstadt Waldmünchen - Franz Xaver Lommer (p139, 1888)

The British Library

Returning to the inn, I propped myself between two chairs in the hope of sleeping, but in vain; the stirrings of my imagination overcame my tiredness. I thought ceaselessly of my courier: dinner had nothing to do with it. I lay there amongst the lowing of herds being driven back to the fields. At ten at night another noise arose; the watchman sang out the time; fifty dogs barked; after which they went off to their kennels as if the watchman had ordered them to be silent; I recognized German discipline.

Civilisation has progressed in Germany since my trip to Berlin: the beds are now almost long enough for a man of average height; but the top-sheet is always sewn to the coverlet, and the bottom-sheet, too narrow, ends by wrinkling and rolling itself into a ball in a very bothersome manner. But since I am in Auguste Lafontaine’s country I will imitate his genius; I wish to inform farthest posterity of the contents, in my day, of my room in the inn at Waldmünchen. Know then distant cousin, that the chamber is in the Italian style, with bare whitewashed walls, without panelling or tapestries, with a wide skirting board or coloured surround at the base, the ceiling with a triple-circled rose, a cornice painted with blue rosettes with a garland of chocolate-coloured bay leaves, and below the cornice, on the wall, leafage in a red design on an American green background. Here and there, little French and English framed engravings: two windows with white cotton curtains: between the windows, a mirror: in the middle of the room a table to seat at least twelve, furnished with an oilcloth covering, its background olive printed with roses and other flowers: six chairs with cushions in red tartan material: a chest of drawers and three beds around the walls; and in a corner, near the door, an earthenware stove glazed black, its sides presenting the arms of Bavaria in relief, surmounted by a container in the shape of a Gothic crown. The door is furnished with a complex iron contraption capable of securing prison doors while foiling skeleton-keys, lovers, and thieves. I point out, to travellers, this excellent room, where I wrote the above inventory which rivals that in The Miser; I recommend it to future Legitimists who may be brought to a halt by descendants of the wild red Alpine goat of Haselbach. This page of my Memoirs will delight the modern school of literary realism.

Having counted, by the light of my lamp, the mouldings on the ceiling, gazed at the engravings of the Milanese Girl, the Beautiful Swiss Girl, the French Girl, and the Russian Girl, the former King of Bavaria, and the former Queen of Bavaria, who looks like a lady I know but whose name I find it impossible to remember, I snatched a few moments sleep.

Emerging from my bed, on the 22nd at seven, a bath removed the rest of my fatigue, and I had only to amuse myself with my little market town, like Captain Cook with some Pacific isle he had discovered.

Waldmünchen is built on the slope of a hill; it resembles a decayed village in the State of Rome. Several house fronts painted with frescoes, a vaulted gateway at the entrance and exit to the main street, no visible shops, and a dried-up fountain in the square. Dreadful paving is interspersed with large slabs and cobbles, such as one no longer sees in the neighbourhood of Quimper-Corentin.

The people, whose appearance is rural, wear no particular costume. The women have their heads bare or wrapped in a kerchief like Parisian dairy-maids; their skirts are short; they have bare feet and legs like the children. The men are dressed partly like the labourers in our towns, partly like the ancient peasantry. God be praised! They only wear hats, and the infamous cotton caps of our bourgeois are unknown here.

Every day in Waldmünchen there is, ut mos (according to custom), an interesting spectacle at which I was present for the early stages. At six in the morning, an old shepherd, tall and lean, goes round the village to various locations; he sounds a straight horn, six feet long, which from afar looks like a speaking trumpet or a shepherd’s crook. He first sounds three quiet melodious metallic notes then he blows a kind of gallop or cattle-call (ranz des vaches), imitating the lowing of oxen and the grunting of pigs. The fanfare ends on a sustained note rising in pitch.

Suddenly from every gateway pour cows, heifers, calves and bulls; lowing, they invade the village square; they climb or descend from all the surrounding streets, and, formed up in column, they take their usual route to pasture. A squadron of pigs grunting like wild boars wheels round after them. Sheep and lambs, bleating, herded in line, compose the third section of the band; geese form the reserve: in a quarter of an hour all have vanished.

In the evening, at seven, the horn is heard again; the herds return. The order of the troop has altered: the pigs form the vanguard, to the same musical accompaniment; some, sent out as scouts, run around randomly or halt in every corner. The sheep file by; the cows, with their sons, daughters and husbands, end the procession; the geese waddle alongside. All these creatures regain their dwellings, none mistakes its own gate; but there are Cossacks who maraud around, scatter-brains who frisk about and balk at entering, bullocks that refuse to stay with a group that is not from their stable. Then come the women and children with their little goads; they force the laggards to rejoin the crowd, and the refractory to submit to rule. I rejoiced at the spectacle, as once Henri IV at Chauny was amused by a cowherd named Everyman who gathered in his herd to the sound of a trumpet.

Many years ago, at Madame de Custine’s residence, the Château de Fervaques in Normandy, I occupied Henri IV’s room; my bed was enormous: the Béarnais had slept there with some Florette; I acquired a love of royalty there, since I did not possess it naturally. Water-filled moats surround the château. The view from my window extended over meadows which border the little river of Fervaques. In the meadows one morning I saw an elegant sow of extraordinary whiteness; she had the look of Prince Marcassin’s mother. She was lying on fresh dewy grass at the foot of a willow tree; a young boar was gathering a little fine ragged moss with his ivory tusks, and depositing it over the sleeper; he repeated this operation until the white sow was entirely hidden: only her black feet emerged from the coverlet of verdure in which she was shrouded.

There is a tribute to a creature of ill repute that I would be ashamed to have written about at such length, if Homer had not sung it. Indeed I realise that this section of my Memoirs is nothing less than an Odyssey: Waldmünchen is Ithaca; the shepherd is the faithful Eumaeus with his swine; I am the son of Laertes, returning from my travels on land and sea. I would perhaps have done better to get drunk on the nectar of Evanthe, to eat the flower of that plant moly, to languish in the land of the Lotus Eaters, rest with Circe or obey the song of the Sirens singing: ‘Come, come to us.’

BkXXXVI:Chap11:Sec2

22nd of May 1833.

If I were twenty, I would seek adventures in Waldmünchen as a means of shortening the hours; but at my age one no longer has a silken ladder except in memory, and one only climbs walls with the shades. Once I was a great friend of my body; I advised him to live wisely, in order to show himself a fine and vigorous fellow in forty years time. He mocked these soulful sermons, insisted on amusing himself and would not have given two figs to reach the day when he might be called a well-preserved individual: ‘To the Devil!’ he cried, ‘what would I gain by sparing myself in youth in order to enjoy life’s delights when no one wanted to share them with me?’ And he made himself happy enough.

So I am forced to take him as he is now: I took him out walking on the 22nd to the south-east of the village. Among the marshlands we followed a little stream of water that drives the mills. They make cotton fabrics at Waldmünchen; lengths of these fabrics were laid out in the meadows; girls, charged with dampening them ran up and down in bare feet on the white zones preceded by the water spurting from their watering cans, like gardeners watering a flower bed. Beside the brook I thought of my friends, I was moved at memory of them then I asked myself what they might be saying about me in Paris: ‘Has he arrived? Has he seen the Royal Family? Will he soon be home?’ And I deliberated on whether to send Hyacinthe in search of fresh butter and brown bread, to eat with cress beside a spring under a pollarded alder. My life has never been more ambitious than that: why has fortune hitched my coat-tails to her wheel, along with a piece of royal mantle?

Returning to the village, I passed the church; two shrines outside border the road; one shows St Peter in Chains with a collection box for prisoners; I gave a few kreutzers in memory of Pellico’s gaol and my cell at the Police Prefecture. The other shrine offered a scene from the Garden of Olives: a scene so moving and sublime that here it is not spoilt even by the grotesque treatment of the figures.

I hurried my dinner and rushed off to evening prayers, summoned by bells. Turning the corner of the narrow street by the church, a glimpse can be had of the distant hills: a gleam of light still showed on the horizon and that dying light shone from the direction of France. A profound sentiment pierced my heart. When will my pilgrimage end? I was wretched enough crossing German territory while returning from the Army of the Princes, triumphant enough when as Ambassador to Louis XVIII I travelled to Berlin; after so many diverse years, I have penetrated surreptitiously into the depths of that same Germany to seek the King of France, exiled once more.

I entered the church: it was utterly dark; with not even a lamp alight. Through the darkness, I only made out the sanctuary, in a Gothic recess, by its deeper obscurity. The walls, altars, pillars, seemed charged with ornamentation and shadowy paintings; the nave was full of dense rows of benches.

An old woman was telling the paternoster on her rosary in a loud voice in German; women young and old, whom I could not see, replied with Ave Maria. The old woman articulated well, her voice was distinct, her accents grave and full of pathos; she was two rows away from me; her head bowed slowly in the shadows each time she pronounced the word Christo, in adding a prayer to her paternoster. The rosary was followed by Litanies of the Virgin; the ora pro nobis, chanted in German (bitte für uns) by the invisible worshippers, sounded in my ears like the word hope (espérance, espérance, espérance!) We scurried off; I went to my bed with hope; I have not held her in my arms for a long time; but she never ages, and one always loves her despite her infidelities.

According to Tacitus the Germans believed night to be more ancient than day: nox ducere diem videtur. Yet I have counted brief night and never-ending days. The poets tell us also that Sleep is the brother of Death: I am not so sure of that, but certainly Old Age is his closest relative.

BkXXXVI:Chap11:Sec3