François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXXV: Arrest, Switzerland, Trial 1832-1833

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXXV: Chapter 1: Madame la Duchesse de Berry’s 12000 francs

- Book XXXV: Chapter 2: General Lamarque’s cortege

- Book XXXV: Chapter 3: Madame la Duchesse de Berry goes to Provence and arrives in the Vendée

- Book XXXV: Chapter 4: My arrest

- Book XXXV: Chapter 5: The journey from my thief’s lodging to Mademoiselle Gisquet’s dressing-room – Achille de Harlay

- Book XXXV: Chapter 6: The Examining Magistrate – Monsieur Desmortiers

- Book XXXV: Chapter 7: My life at Monsieur Gisquet’s – I am set at liberty

- Book XXXV: Chapter 8: A letter to the Justice Minister and his reply.

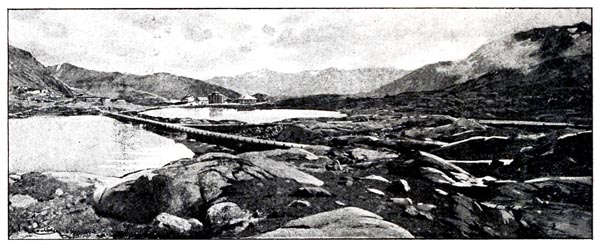

- Book XXXV: Chapter 9: Charles X offers to pay me a Peer’s pension: my response

- Book XXXV: Chapter 10: A note from Madame la Duchesse de Berry – A letter to Béranger – Departure from Paris

- Book XXXV: Chapter 11: Journal from Paris to Lugano

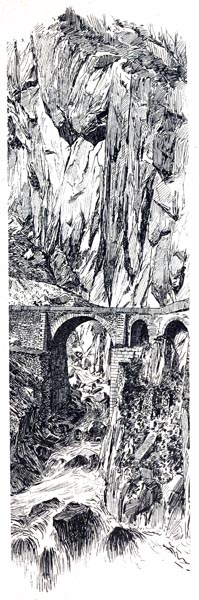

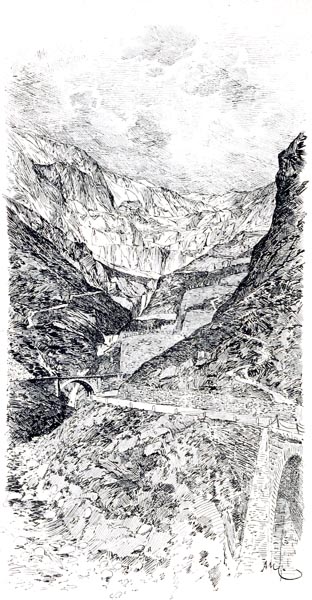

- Book XXXV: Chapter 12: The Saint-Gothard Pass

- Book XXXV: Chapter 13: The Schöllenen Gorge – Devil’s Bridge

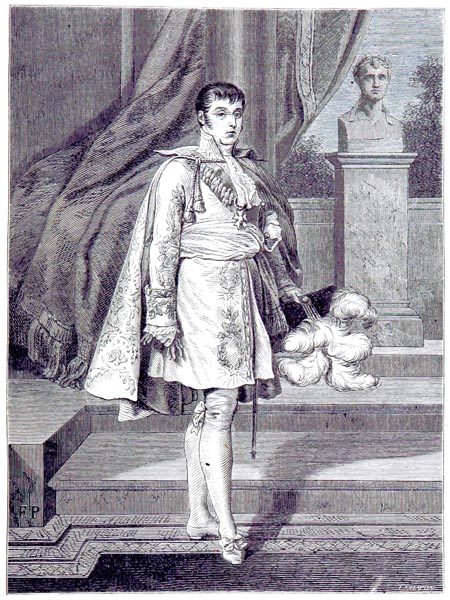

- Book XXXV: Chapter 14: The Saint-Gothard

- Book XXXV: Chapter 15: A description of Lugano

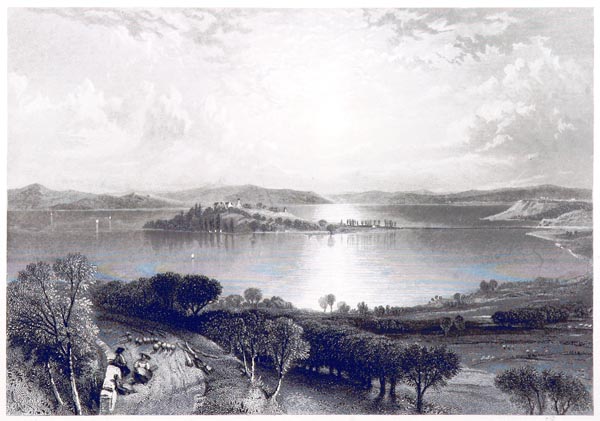

- Book XXXV: Chapter 16: The mountains – Trips around Lucerne – Clara Wendel - Peasant prayers

- Book XXXV: Chapter 17: Monsieur Alexandre Dumas – Madame de Colbert – A letter from Monsieur de Béranger

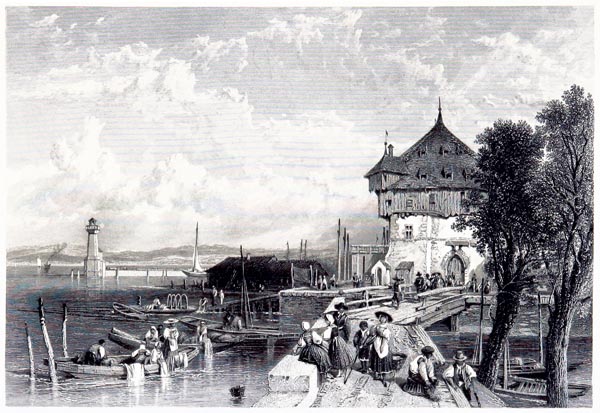

- Book XXXV: Chapter 18: Zurich – Constance – Madame Récamier

- Book XXXV: Chapter 19: Madame la Duchesse de Saint-Leu

- Book XXXV: Chapter 20: Arenenberg – Return to Geneva

- Book XXXV: Chapter 21: Coppet – Madame de Staël’s tomb

- Book XXXV: Chapter 22: A walk

- Book XXXV: Chapter 23: A letter to Prince Louis-Napoleon

- Book XXXV: Chapter 24: A circular to the editors-in-chief of the newspapers – Letters to the Minister of Justice, the President of the Council, and Madame la Duchesse de Berry – I write my Memoir on the Princess’ captivity

- Book XXXV: Chapter 25: Extract from my Memoir on the Captivity of Madame la Duchesse de Berry

- Book XXXV: Chapter 26: My trial

- Book XXXV: Chapter 27: Popularity

Book XXXV: Chapter 1: Madame la Duchesse de Berry’s 12000 francs

Paris, Rue d’Enfer, May 1832.

BkXXXV:Chap1:Sec1

Madame de Berry had her little group of advisers in Paris, as Charles X had his: they received small sums of money in her name to assist poverty-stricken royalists. I proposed to distribute a sum of twelve thousand francs to the cholera victims on behalf of Henri V’s mother. They wrote to Massa, and not only did the Princess approve the distribution of funds, but she wished it could be a more considerable amount: her letter agreeing this arrived on the same day that I sent the money to the mayoralties. Thus, everything I said about the exile’s gift is strictly correct. On the 14th of April I sent the Prefect of the Seine the full amount to be distributed to the poorest section of the population of Paris afflicted by contagion. Monsieur de Bondy was not at the Hotel de Ville when my letter was delivered to him. The Secretary General opened my missive, but did not consider himself authorised to accept the money. Three days passed. Monsieur de Bondy at last replied to me saying that he could not accept the twelve thousand francs because in the guise of charity it was evidently a political device, which the whole population of Paris would protest against, by its refusal. My secretary then approached the twelve district mayors. Of the five mayors present, four accepted the gift of a thousand francs; one refused. Of the seven mayors not present, five maintained their silence: two refused.

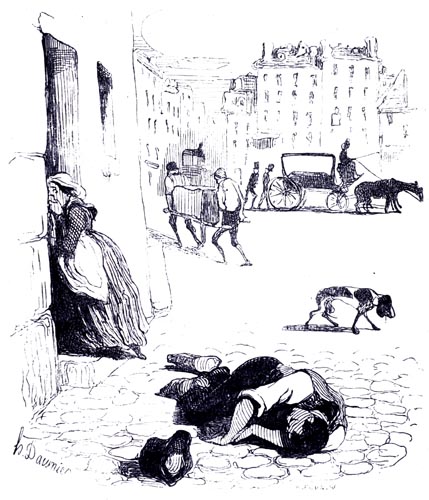

‘Souvenirs du Choléra-Morbus’

Némésis Médicale Illustrée: Recueil de Satires - François Fabre, Honoré Daumier (1840)

Images from the History of Medicine - US National Library of Medicine

I was immediately besieged by an army of indigents: charitable foundations, workers of all kinds, women and children. Italian and Polish exiles, writers, artists, soldiers, all wrote, and all claimed a part of the donation. If I had possessed a million, it would have gone in a few hours. Monsieur de Bondy was wrong in saying that the whole population of Paris would protest by its refusal: the population of Paris will accept money from anyone. The government’s agitation was laughable; one would have thought this treacherous legitimist cash would cause an uprising among the cholera victims, and excite an insurrection of the dying in the hospitals, who would march to assault the Tuileries, beating their coffins, tolling the death-knell, deployed in their shrouds under the command of Death. My correspondence with the mayors was lengthened by the complication caused by the Prefect of Paris’ refusal. Some of them wrote to me to return my money or to ask me for a receipt regarding the return of Madame la Duchess de Berry’s gift. I duly sent them and delivered this acknowledgement to the Mayor of the twelfth district:

‘I have received from the Mayor of the twelfth arrondissement the sum of one thousand francs which he had previously accepted and which he has returned to me by order of the Prefect of the Seine.

Paris, this 22nd of April 1832.’

The Mayor of the ninth district, Monsieur Cronier, was more courageous: he kept the thousand francs and was relieved of his duties. I wrote him this note:

‘29th of April 1832.

Sir,

I learn with distress of your dismissal, of which Madame la Duchesse de Berry’s gift was the cause, or for which it was the pretext. You have for consolation the public’s esteem, your feelings of independence and the knowledge of your self-sacrifice in the victims’ cause.

I have the honour, etc, etc.’

The Mayor of the fourth district was quite another sort: Monsieur Cadet de Gassicourt, the poet-pharmacist, maker of little verses, creating in his age, the age of liberty and Empire, a pleasantly classical statement opposing my romantic prose and that of Madame de Staël, was the hero who took by assault the cross from above the porch of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois, and who, in a proclamation regarding the cholera, stated that the wicked Carlists may well have been those who poisoned the wine, to whom the people had already meted out justice. The illustrious champion then wrote me the following letter:

‘Paris, the 18th of March 1832.

Sir,

I was absent from the city hall when the person you sent presented himself: that will explain my delay in replying.

Monsieur le Préfet de la Seine, having refused to accept the money which you were charged with offering him, seems to me to have laid down the mode of conduct which the Members of the Municipal Council should adopt. I follow Monsieur le Préfet’s example even more strongly in that I believe in and share entirely the sentiments which led him to refuse.

I will merely mention in passing the title Royal Highness bestowed with affection on the person of whom you are appointed agent: the daughter-in-law of Charles X is no more a Royal Highness in France, than her father-in-law is king! Yet, Sir, there is no one who is not morally convinced that this lady is an active agitator, and expends sums much more considerable than those she has trusted you to employ, in stirring up trouble in our country and instigating civil war. The alms which she has the pretension to bestow are merely a means of attracting attention to herself and her party and are a kindness which her intentions are far from justifying. You will not find it strange then that a magistrate firmly attached to the constitutional monarchy of Louis-Philippe should refuse help which comes from such a source, and will find, among true citizens, purer acts of generosity addressed with sincerity to humanity and our country.

I am, with the greatest respect, Sir, etc.

F. CADET DE GASSICOURT.’

This attack of Monsieur Cadet de Gassicourt’s on the lady and her father-in-law displays great pride: what progress enlightenment and philosophy have made! What an invincible show of independence! Messieurs Fleurant and Purgon would only have dared gaze at people on their knees; to them, Monsieur Cadet says like the Cid: Let us rise then! His liberty is all the more courageous in that this father-in-law (otherwise a descendant of Saint Louis) is proscribed. Monsieur de Gassicourt is above all that; he scorns the nobility and the misfortunes of the age equally. It is with the same disdain for aristocratic prejudices that he misses out my de in addressing me, and takes it as a victory over the gentry. Yet, was there not some ancient rivalry, some ancient historic dispute between the House of Cadet and the House of Capet?

Henri IV, ancestor of this father-in-law who is no more king than the lady is a Royal Highness, was traversing the forest of Saint-Germain one day; eight Leaguers lay in ambush to murder the Béarnais; they were seized. ‘One of these gallants,’ says L’Estoile, ‘was an apothecary who demanded to speak to the King, and on His Majesty enquiring of what rank he was, he replied that he was an apothecary. “What!” said the King, “is there a rank of apothecary round here? Do you lie in wait for passers-by to give them enemas?”’ Henri IV was a soldier, immodest speech scarcely bothered him, and he no more retreated from a word than from an enemy.

I suspect Monsieur de Gassicourt, given his ill-humour towards Henri IV’s descendant, of being a descendant of that pharmacist Leaguer. The Mayor of the fourth district no doubt wrote to me in the hope that I would cross swords with him; but I do not wish to do battle with Monsieur Cadet: may he forgive me for leaving him a little mark of my remembrance here.

Since those days when I witnessed great revolutions and great revolutionaries, everything has shrivelled. Men who toppled an oak tree, too old to take root if replanted, addressed themselves to me; they demanded a few pounds from the widow in order to buy bread; this letter from the Committee for the July Medal-Winners is a useful document to note for future reference.

‘Paris, the 20th of April 1832.

RSVP, to Monsieur Gibert-Arnaud, Managing-Secretary of the Committee, 3 Rue Saint-Nicaise.

Monsieur le Vicomte,

The Members of our Committee write in confidence to ask you if you would honour them with a gift for the July medal-winners, unfortunate family men; in this time of plague and misery, your kindness would inspire the most sincere gratitude. We dare to hope that you will consent to set your illustrious name beside those of Messieurs le General Bertrand, General Exelmans, General Lamarque, General Lafayette, various Ambassadors, Peers of France, and Deputies.

We beg you to honour us with a word in reply, and if, contrary to our hopes, a refusal follows our request, be good enough to return this note to us.

With the purest of sentiments we beg you, Monsieur le Vicomte, to accept the homage of our respective greetings.

The active Members of the Committee for the July Medal-Winners:

Visiting Member: Faure.

Special Commissioner: Cyprien-Desmaret.

Managing-Secretary: Gibert-Arnaud.

Assistant Member: Tourel.’

I took care not to relinquish the advantage that the July Revolution here granted me over itself. In distinguishing between people, it had created islands of unfortunates, who, because of certain political opinions, were not to be helped. I quickly sent the gentlemen a hundred francs, with this note:

‘Paris, this 22nd of April 1832.

Gentlemen,

I thank you deeply for contacting me with regard to my coming to the aid of various unfortunate family men. I hasten to send you the sum of one hundred francs; I regret not having a more substantial gift to offer.

I have the honour, etc.

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

The following receipt was sent to me immediately:

‘Monsieur le Vicomte,

I have the honour to thank you and to acknowledge receipt of one hundred francs which you kindly destine for relief of the July unfortunates.

Salutations and respect.

The Managing-Secretary of the Committee:

GIBERT-ARNAUD.

23rd of April.’

Thus, Madame la Duchesse de Berry gave alms to those who had pursued her. These transactions lay bare the heart of things. Consider the reality of a country where no one cares for their party’s casualties, where the heroes of yesterday are cast adrift tomorrow, where a little gold attracts a crowd, as farmyard pigeons flock to the hand that throws them grain.

Four thousand francs of the twelve thousand remained. I addressed myself to religion; Monsignor the Archbishop of Paris wrote me this noble letter:

‘Paris, the 26th of April 1832.

Monsieur le Vicomte,

Charity like faith is catholic, a stranger to human passions, independent of their politics: one of the primary characteristics which distinguish it, according to St Paul, is to think no evil: non cogitate malum. She blesses the hand that gives and the hand that receives, without attributing to the generous benefactor any motive other than that of doing a good deed, and without asking from the poor sufferer any condition other than need. She accepts with profound and heart-felt thanks the gift that the august widow has charged you with conferring on her, for the relief of our unfortunate brothers who are victims of the scourge which has afflicted the capital.

She will distribute the four thousand francs you have give me for her with faithful care, and this letter is a fresh receipt, but I will have the honour to inform you of the details of the distribution when the benefactress’ intentions have been fulfilled.

Monsieur le Vicomte, please convey to the Duchesse de Berry the gratitude of a shepherd and father who offers his life to God, every day, on behalf of his lambs and his children, and who calls to everyone for aid sufficient to meet their needs, Her royal heart has doubtless already found within herself recompense for the sacrifice she has made for our unfortunates; religion assures her moreover of the efficacy of the divine promise committed to delivering blessings upon those who show mercy.

A distribution has been carried out immediately among the priests of the twelve main parishes of Paris, to whom I am addressing the letter of which I here enclose a copy.

Accept, Monsieur le Vicomte, the assurance, etc.

Hyacinthe, Archbishop of Paris.’

It is always wonderful to see how religion creates its own style, and gives even to commonplaces a gravity and propriety which one feels at once. It contrasts with the tone of those anonymous letters which were mingled with the letters I have just cited. The orthography of these anonymous letters is correct enough, the writing fine; they are, properly speaking, literary, like the July Revolution. They show the jealousies, hatreds and vanities of hacks protected by the inviolability of a cowardliness which never showing its face cannot be revealed by a slap.

SAMPLES

‘Tell us when you grease your moccasins, you old Republican! We can easily find you some Chouan grease, and some of your friends’ blood to write their history with if you like, there’s plenty in the Paris mud, it’s their element.

Ask your rascally and worthy friend Fitz-james, Old Brigand, if the stone he received in the feudal cause gave him pleasure. You pile of scoundrels, we’ll rip your guts out, etc, etc.’

In another missive, can be seen a neatly draw gallows with these words:

‘Get on your knees to a priest, and make contrition, as we want your old head to end its treason.’

Anyway, the cholera is still with us: the reply I might send a known, or unknown, adversary might perhaps arrive when he was dying at the threshold of his house. If on the other hand he was destined to live, where would his reply reach me? Perhaps in that place of rest which no one fears these days, above all we whose lives span the Terror, and the Plague, the first and last of our life’s horizons. Enough: let the coffins go by.

Book XXXV: Chapter 2: General Lamarque’s cortege

Paris, Rue d’Enfer, 10th of June 1832.

BkXXXV:Chap2:Sec1

General Lamarque’s cortege lead to two blood-stained days and the victory of the Quasi-Legitimacy over the Republican Party. The latter, fragmented and disunited, carried out a heroic resistance.

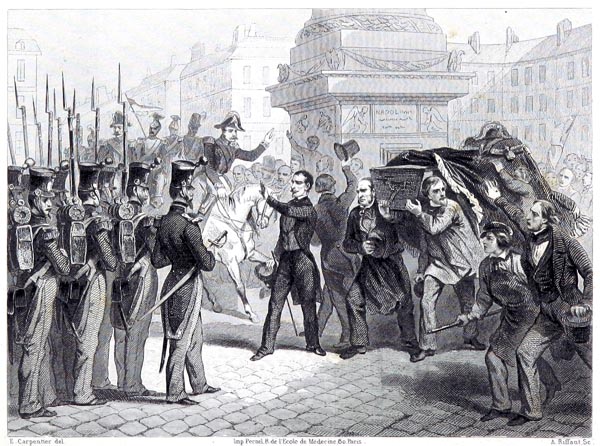

‘Convoi du Général Lamarque’

Le Dernier Roi - Alexandre Dumas (p446, 1854)

The British Library

Paris was placed in a state of siege: it was censure on the largest possible scale, censure in the style of the Convention, with this difference that a military commission replaced the revolutionary tribunal. In June 1832 they shot the men who brought them victory in July 1830; they sacrificed that same École Polytechnique, that same artillery of the National Guard, who had conquered the powers that be, on behalf of those who now struck at them, disavowed them and cast them off! The Republicans were certainly wrong to have espoused the methods of anarchy and disorder; but should we not rather have deployed such noble arms on our frontiers? They would have delivered us from the yoke of the stranger. Generous and exalted spirits would not thereby have remained in Paris fermenting trouble, inflamed by our shameful foreign policy and the disloyalty of our new monarchy. You have shown no mercy, you who, without sharing the dangers of the Three Days, reaped the rewards. Go, with their mothers, now, and seek the bodies of those medal-winners of July, whose positions, wealth and honours you have taken. You, our young men, have met differing fates on the same shore! You possess both tombs beneath the colonnade of the Louvre and places in the Morgue; some for having seized, others for having granted a crown. Who knows your names, you makers of sacrifice and you victims, forever unknown, of a memorable revolution? Who remembers those whose blood cements the monuments men admire? The workers who built the Great Pyramid, to hold the body of an inglorious pharaoh, sleep forgotten in the sand, among the sparse roots that nourished them during their labour.

‘Les Grandeurs de Désespoir, A. de Neuville (Les Misérables p381 vol. 05)’

Cent Dessins: Extraits des Oeuvres de Victor Hugo: Album Specimen - Victor Hugo (p98, 1800)

Internet Archive Book Images

Book XXXV: Chapter 3: Madame la Duchesse de Berry goes to Provence and arrives in the Vendée

Paris, Rue d’Enfer, the end of July 1832.

BkXXXV:Chap3:Sec1

Madame la Duchesse de Berry had no sooner sanctioned the expenditure of her 12000 francs than she embarked on her notorious adventure. An attempt to rouse Marseilles failed; only the West remained open to an attempt: but the glory of the Vendée is another thing; it lives on in the splendour of our history, yet nine tenths of France chose a different glory, the object of jealousy and antipathy; the Vendée is an Oriflamme, venerated and admired, in the treasury of Saint-Denis, beneath which youth and the future no longer range themselves.

‘Oriflamme’

History of the Battle of Agincourt, and of the Expedition of Henry the Fifth into France in 1415 - Sir Nicholas Harris Nicolas (p146, 1833)

Internet Archive Book Images

Madame, disembarking like Bonaparte, on the coast of Provence, saw no white banners flying from steeple to steeple: deceived in her expectations, she found herself almost alone with Monsieur de Bourmont in the field. The Marshal wanted her to cross the frontier again immediately; she asked for a night to consider; she slept well on the cliffs to the sound of the sea; on waking in the morning she pursued a noble dream with the thought: ‘Since I am on French soil, I will not leave: let us go to the Vendée.’ Monsieur de Villeneuve-Bargemont, warned by a loyal follower, took her in his carriage with his wife, crossed the whole of France, and deposited her at Montaigu, where she stayed for a while, in a château, without being recognised except by a priest of the place; Marshal Bourmont was to rejoin her in the Vendée, by another route.

Informed of all this in Paris, it was easy for us to foresee the result. The enterprise presented another problem for the royalists; it would reveal the weakness of their cause and dispel illusions. If Madame had not gone to the Vendée, France would have continued to think there was, in the West, a Royalist force-in-waiting, as I dubbed it.

But there was still, in the end, a means of rescuing Madame and casting a fresh veil over the reality: the Princess must leave immediately; meeting with danger and peril, like a brave general reviewing an army, tempering impatience and ardour, she could have declared that she had hastened there to tell the soldiers that the time for action was not yet favourable, and that she would return to place herself at their head when the occasion demanded. Madame would at least have shown the inhabitants of the Vendée a Bourbon for once; the shades of Cathelineau, d’Elbée, Bonchamp, La Rochejaquelein, and Charette would have rejoiced.

Our committee assembled; while we were in discussion, a captain arrived from Nantes who told us where our heroine was staying. The captain was a fine young man, tough as a sailor, a Breton original. He disapproved of the enterprise; he thought it was foolish; but he said: ‘If Madame does not leave, it will prove mortal and that’s that; then, gentlemen of the council, you may hang Walter Scott, it will be he who is the guilty party.’ I was advised to write and inform the Princess of this sentiment. Monsieur Berryer, who was arranging to go to Vannes to plead a case, generously proposed to carry the letter and see Madame if he could. When it became necessary to pen the note, no one cared to write it: I took on the task.

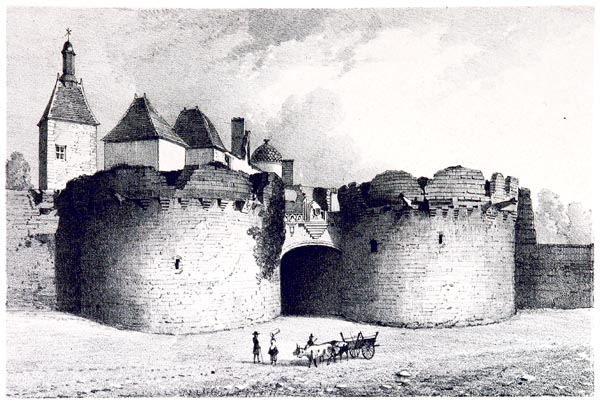

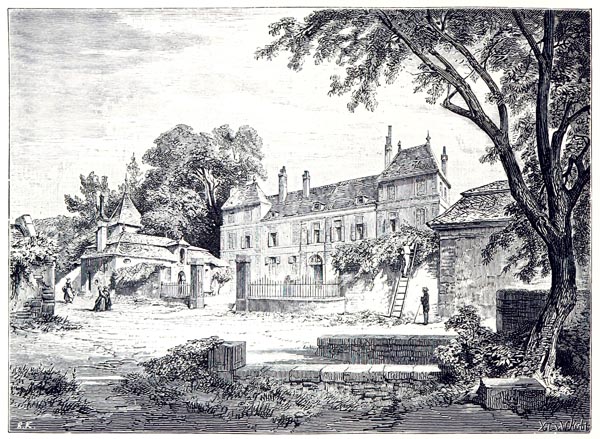

‘Le Château d'Ancenis, Nantes’

Histoire d'Ancenis et de ses Barons - Em Maillard (p221, 1860)

The British Library

Our messenger left, and we waited on events. I soon received the following letter, by post, which had not been concealed and had doubtless passed beneath the eyes of the authorities:

‘Angoulême, the 7th of June.’

Monsieur le Vicomte,

I had received and transmitted your letter of last Friday, when on Sunday the Prefect of the Lower Loire invited me to leave Nantes. I was en route and at the gates of Angoulême; I have just been brought before the Prefect who has informed me of an order of Monsieur de Montalivet’s which requires me to be taken back to Nantes under police escort. Since my departure from Nantes, the department of the Lower Loire is in a state of siege: by this illegal action they are subjecting me to the laws of ‘exception’. I have written to the Minister asking him to have me summoned to Paris; he has my letter by this courier. The aim of my journey to Nantes seems to have been completely misinterpreted. Judge whether in your prudence it would be appropriate to speak to the Minister. I ask your pardon for making this request of you; since I can address no one but you.

Believe, Monsieur le Vicomte, in my sincere and lasting attachment, as in my profound respect.

Your devoted servant,

BERRYER THE YOUNGER.

P. S. – There is no time to be lost if you wish to see the Minister. I am on my way to Tours, where his fresh orders would find me on Sunday; he could transmit them by telegraph or despatch rider.’

I informed Monsieur Berryer, in this reply, of the action I had taken:

‘Paris, the 10th of June 1832.

Sir, I have received your letter dated from Angoulême on the 7th of this month. It was too late to see the Minister of the Interior, as you would have wished me to; but I wrote to him immediately and passed him your letter enclosed with mine. I hope that the mistake which has led to your arrest will soon be acknowledged, and that you will be returned to freedom and your friends, among whom I beg to be included. A thousand compliments to you, and a fresh assurance of my sincere and complete devotion.

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

This was my letter to the Minister of the Interior:

‘I have just received the enclosed letter. As it is likely that I will be unable to see you as swiftly as Monsieur Berryer desires, I have adopted the course of sending you his letter. His summons seems right to me: he will be as innocent in Paris as at Nantes; the authorities will acknowledge this, and will, by allowing Monsieur de Berryer’s recall, avoid applying the law retrospectively. I dare to rely totally, Monsieur le Comte, on your impartiality.

I have the honour, etc, etc.

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

Book XXXV: Chapter 4: My arrest

Paris, Rue d’Enfer, the end of July 1832.

BkXXXV:Chap4:Sec1

An old Scottish friend of mine, Mr Frisell, had just lost his only daughter, of seventeen, at Passy. On the 15th of June I went to the funeral of poor Élisa, whose portrait pretty Madame Delessert was finishing when death set there the last mark of the brush. Returning to my solitude, in the Rue d’Enfer, I retired to bed full of melancholy thoughts arising from the conjunction of youth, beauty and the grave. On the 16th of June, at four in the morning, Baptiste, who had been many years in my service, approached my bed and said: ‘Sir, the courtyard is full of men placed at all the doors who forced Desbrosses to open the wicket, and there are three gentlemen who wish to speak to you.’ As he finished speaking, the gentlemen entered, and their leader, very politely approaching my bed told me he had orders to arrest me and take me to the Police Prefecture. I asked him if the sun had yet risen, as the law required, and if he carried a legal order: he did not reply in regard to the sun, but he showed me the following document:

Copy:

‘PREFECTURE OF POLICE.

By command of the King;

We, a Councillor of State, and Prefect of Police,

Acting on information received;

In virtue of Article 10 of the Criminal Code;

Require the Superintendent, or another if he is unavailable, to go to Monsieur le Vicomte de Chateaubriand’s, or anywhere else as needs be, to prevent a plot against the State, with the aim of making of a search there and seizing all papers, correspondence, and writings containing incitements to crime or offences against the public peace, where open to examination, as well as all seditious objects or weapons which he may possess.’

While I was reading this declaration of a great plot against the security of the State, of which little I was accused, the police chief said to his subordinates: ‘Gentlemen, do your duty!’ These gentlemen’s duty was to open all the cupboards, to rummage in all my pockets, to seize all my papers, letters and documents, to read them, if they could, and discover all weapons, as required by the terms of the aforesaid order.

After a reading of the document, I addressed myself to the respectable leader of these takers of men and freedom: ‘You know, Sir, that I do not recognise your government, and that I protest against the violence done to me; but as I am not the stronger and have no desire to grapple with you, I will get up and follow you: have the goodness, I beg you, to take a seat.’

I dressed, and taking nothing with me, I said to the venerable Superintendent: ‘Sir, I am at your disposal: are we going on foot? – No, Sir, I have taken the trouble to get you a cab. – That is very good of you: Sir, let us depart; but allow me to say goodbye to Madame de Chateaubriand. Will you allow me to go into my wife’s room alone? – Sir, I will accompany you to the door and wait for you there – Very well, Sir.’ And we descended.

In the street, there were sentries everywhere; they had even placed a cavalry picket on the boulevard, at a little door which opened onto the end of my garden. I said to their chief: ‘These precautions were quite useless; I have not the least intention of fleeing you and escaping.’ The gentlemen had jumbled my papers but not taken anything. My great Mameluke sabre caught their attention; they talked in low voices and ended by leaving the weapon under a heap of dusty folios, in the midst of which lay a crucifix of yellow wood which I had brought from the Holy Land.

This pantomime would have almost roused me to laughter, but I was cruelly tormented in regard of Madame de Chateaubriand. Whoever knows her, also knows the tenderness she shows towards me, her fears, the liveliness of her imagination and the wretched state of her health; the police swoop and my arrest must have given her a great shock. She had already heard the noise and I found her sitting on her bed, listening in fear, when I entered her room at that extraordinary hour.

‘Oh, dear God!’ she cried: ‘are you ill? Oh, dear God, what is it? What is it?’ And she took to trembling. I embraced her, barely restraining my tears, and said: ‘It is nothing, they have sent for me to take my statement as a witness to some business concerning a censorship trial. It will all be finished in a few hours, and I will return to dine with you.’

The agent had remained by the open door; he saw this scene, and as I placed myself in his hands once more, I said: ‘You see, Sir, the effects of your morning visit.’ I crossed the courtyard with my escort; three of them climbed into the cab with me, the rest of the squad accompanied the prisoner on foot and we arrived without delay in the courtyard of the Prefecture of Police.

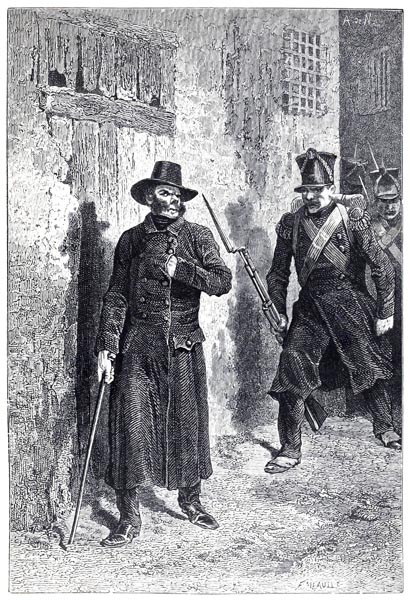

‘Javert a la poursite de Jean Valjean et de Cosette, A. de Neuville (Les Misérables p217 vol. 02)’

Cent Dessins: Extraits des Oeuvres de Victor Hugo: Album Specimen - Victor Hugo (p82, 1800)

Internet Archive Book Images

The gaoler who ought to have admitted me to a holding cell was not up yet; they woke him by knocking on his wicket, and he went off to prepare my residence. While he was occupied with his work, I walked to and fro in the yard with Monsieur Léotaud who was guarding me. He spoke to me amicably, since he was very honest, saying: ‘Monsieur le Vicomte, it is a great honour to meet you; I presented arms before you several times when you were a Minister and you came to see the King: I served in the Bodyguards: but there it is! I have a wife and children; one must live! – You are right, Monsieur Leotard: how much does it bring in? – Ah! Monsieur le Vicomte, that depends on the prisoners. There are bonuses, sometimes good, sometimes poor, as in war.’

‘Le Sergent de Ville’

Les Français Peints par Eux-Mêmes (p761, 1853)

Internet Archive Book Images

During my stroll, I saw agents in various disguises like maskers on Ash Wednesday on the slopes of the Courtille: they came to give their account of their deeds during the night. Some were dressed as greengrocers, street criers, coal vendors, market porters, traders in second-hand clothes, rag and bone men, and organ-grinders; others were wearing wigs, from beneath which poked hair of a different colour; others had beards, moustaches and false sideburns; others limped along as respectable cripples wearing a bright red ribbon in their buttonholes. They vanished into a little courtyard, and soon re-appeared in different costume, without moustaches, beards, sideburns, wigs, baskets, wooden legs, and arms in slings; this whole flock of police birds flew off at dawn and vanished with the rising sun. My cell was ready, the gaoler came to tell us so, and Monsieur Léotaud, doffing his hat, led me to the door of my honest lodging and, as he left me in the hands of the gaoler and his helpers, said: ‘Monsieur le Vicomte, I have been honoured in welcoming you: till we meet again.’ The door closed behind me. Preceded by the gaoler who carried the keys and his two lads who followed me to prevent me turning back, I reached the second floor by a narrow stairway. A dark little corridor led me to a door; the keeper opened it: I followed him into my cell. He asked me if I needed anything: I replied that I would like breakfast in an hour. He advised me there was a kitchen which furnished prisoners with all they could wish, at a price. I asked my gaoler to have me sent some tea, and if possible, hot and cold water and napkins. I gave him twenty francs in advance: he withdrew respectfully promising to return.

Left alone, I inspected my prison: it was a little longer than it was wide, and its height was seven or eight feet. The walls, discoloured and bare, were sprinkled with prose and verse by my predecessors and especially with scribbles by a woman who gave the ‘Centre Ground’ plenty of abuse. A pallet with dirty sheets occupied half the lodging; a plank, supported by two wooden brackets, set against the wall, two feet above the bed, served as a wardrobe for the detainee’s linen, boots and shoes; a chair and a vile appurtenance comprised the rest of the furnishings.

My faithful guard brought me the napkins and jugs of water I had asked for; I begged him to take away the dirty sheets, the blanket of yellow wool, to remove the bucket whose smell was choking me, and to sweep out my cell after swilling it down. All the works of the ‘Centre Ground’ having departed, I shaved; I washed myself with water from my jug, and changed my linen, Madame de Chateaubriand having given me a small supply; I laid out all my possessions on the plank above the bed, as in a cabin on board ship. When that was done, my breakfast arrived and I took my tea at my well-scrubbed table which I covered with a white napkin. Someone arrived shortly to remove the utensils from my morning feast and left me alone duly imprisoned.

My cell was lit only by a window-grill which opened at a height; I placed my table beneath this grill and climbed on the table to get some air and enjoy the light. Through the bars of my thief’s cage I could see a courtyard or rather a narrow shadowy passage, the darkened buildings around it aquiver with bats. I heard the clinking of keys and chains, the sound of policemen and spies, the tread of soldiers, the movement of weapons, shouts, laughter, the wild songs of my fellow prisoners, curses from Benoît, condemned to death for murdering his mother and his lover. I distinguished these words of Benoit’s among his confused cries of fear and repentance: ‘Oh My mother, my poor mother!’ I saw the reverse side of society, the pleas of humanity, and the hideous machines that move the world.

I thank the men of letters, the great partisans of freedom of the Press, who formerly took me as their leader and fought under my command; without them, I would ended my life without knowing what prison was like, and would have missed the experience. I recognise in that delicate attention the genius, goodness, generosity, honour and bravery of the leading writers. But after all, what did this brief trial amount to? Tasso spent years in a dungeon, yet I complain! No; I have not the pride or foolishness to compare my few hours of discomfort with the lengthy sacrifices of those immortal victims whose names history has preserved.

Moreover, I was not at all unhappy; the spirit of greatness past and a glory thirty years old never troubled me; but my Muse of yesteryear, all poor and unknown, came shining to embrace me through the window: she was charmed by my residence and inspired; she found me as she had seen me in my London poverty, when the first idea of René entered my mind. What should we create, that solitary from Pindus and I? A song on the lines of that of the unfortunate poet Lovelace who, in the prisons of the English Commonwealth, sang of King Charles I, his master? No; a prisoner’s voice would have seemed a poor augury for my little King Henri V: hymns to misfortune should be addressed from the foot of the altar. So I did not sing of the crown fallen from an innocent brow; I contented myself with speaking of another crown, also pale, placed on a young girl’s coffin; I remembered Élisa Frisell, whose funeral I had seen the previous day in Passy cemetery. I began some elegiac verses of a Latin epitaph; but then the correct quantity of a word baffled me; quickly I leapt down from the table on which I had been perched, leaning against the bars of the window, and ran to the door on which I beat heavily. The caverns round about echoed; the terrified gaoler ascended followed by two gendarmes; he opened my wicket and I shouted as Santeuil would have done: ‘A Gradus! A Gradus!’ The gaoler stared wide-eyed, the gendarmes thought I was revealing the name of one of my accomplices; they would willingly have handcuffed me; I explained; I gave them money to buy the book, and they went off to ask a Gradus ad Parnassum of the astonished police.

While they were occupied with my commission, I climbed on my table again, and inspired afresh by my tripod, I set to composing verses for Elisa; but in the midst of my inspired flight, about three o’clock, here came the bailiffs into my cell and apprehended my body on the banks of Permessus: they led me before the examining magistrate who drew up his documents in an obscure office, facing my gaol, on the other side of the courtyard. The magistrate, a young robe, well-fed and conceited, asked me the usual questions as to my name, forenames, age, and place of residence. I refused to reply or sign anything, not recognising the political authority of a government which had on its side neither hereditary right nor popular election, since France had not been consulted and there had been no gathering of any national congress. I was led back to my cell.

At six they brought me my dinner, and I continued to work and re-work the lines of my stanzas in my head, improvising at the same time an air which seemed to me to be quite charming. Madame de Chateaubriand sent me a mattress, bolster, sheets, a cotton blanket, candles and the books I like to read at night. I made my bed singing all the while:

The coffin is lowered, the roses without stain,

My romance of the sweet girl and the sweet flower composed itself:

The coffin is lowered, the roses without stain

A father placed there, a tribute to his grief;

Earth, you bore them, hide them now, again,

Sweet girl, sweet flower.

Oh! Do not return them to this world of pain,

This world, profane, of sorrow and despair;

Wind will wither them; sun will make them fade,

Sweet girl, sweet flower.

You sleep, my poor Élisa, so tender of years,

No longer burdened by the heat of day!

You discover a fresher morning here,

Sweet girl, sweet flower.

But Élisa, your father bends towards your grave;

From your brow to his the pallor ascends.

Old oak tree! ...Time uproots the strong and brave,

Sweet girl, sweet flower!

Book XXXV: Chapter 5: The journey from my thief’s lodging to Mademoiselle Gisquet’s dressing-room – Achille de Harlay

Paris, Rue d’Enfer, the end of July 1832.

BkXXXV:Chap5:Sec1

I began to undress; the sound of voices was heard; my door opened and the Prefect of Police accompanied by Monsieur Nay, appeared. He made me a thousand excuses for the length of my detention at the station; he informed me that my friends, the Duke of Fitz-James and Baron Hyde de Neuville had been arrested as I had and that, with the log-jam in the Prefecture, no one knew where the people with whom justice was occupied had been placed. ‘But,’ he added, ‘you must come home with me, Monsieur le Vicomte, and choose which room will best suit you.’

I thanked him and begged him to leave me in my hole; I was already quite charmed by it, as if it were a monk’s cell. The Prefect refused my entreaties and was forced to unearth me. I saw those rooms again which I had not seen since the day when Bonaparte’s Prefect of Police had asked me to visit so he could invite me to leave Paris. Monsieur and Madame Gisquet opened up all their rooms while begging me to say which one I would occupy. Monsieur Nay proposed to yield me his. I was embarrassed by so much politeness; I accepted a little out-of-the-way room looking onto the garden and which, I think, served as a dressing room for Mademoiselle Gisquet; I was allowed to retain my servant who slept on a mattress outside my door, at the entrance to a narrow stairway down to Madame Gisquet’s grand apartment. Another stairway led to the garden; but the latter was forbidden me, and every evening a sentry was posted below by the railing separating the garden from the quay. Madame Gisquet is the nicest woman on earth, and Mademoiselle Gisquet is very pretty and a very competent musician. I had nothing but praise for my hosts’ care: they seemed to wish to recompense me for the twelve hours of my initial imprisonment.

The morning after my taking up residence in Mademoiselle Gisquet’s dressing room, I rose quite contented, remembering Anacreon’s poem on the young Greek girl; I stuck my head out of the window: I could see a little garden, full of greenery, and a high wall hidden by Japanese lacquer-work; on the right, at the end of the garden, were offices where pleasant clerks of the police service could be glimpsed, like lovely nymphs among the lilacs; on the left, the banks of the Seine, the river, and an ancient corner of Paris, in the parish of Saint-André-des-Arts. The sound of Mademoiselle Gisquet’s piano reached me mixed with the voices of agents asking for the divisional heads in order to make their reports.

How the whole world changes! This little romantic English garden assigned to the police was a tiny winding fragment of the French garden, its arbours closely pruned, that belonged to the first President of the Parliament of Paris. This ancient garden occupied the site of that parcel of houses which limits the view to the north and west, and extended to the banks of the Seine. It was here after the day of the barricades, that the Duc de Guise came to visit Achille de Harlay: ‘He found the first President walking in his garden, who was so little astonished by his arrival that he deigned neither to turn his head nor discontinue the walk he had begun, which being achieved, and he being at the end of the path, he returned, and on returning saw the Duc de Guise advancing towards him; then that grave magistrate, raising his voice, said: ‘It is a great pity that the valet has chased his master away; as for the rest, my soul is God’s, my heart is my King’s, and my body is in the hands of rogues; let them do what they will.’ The Achille d’Harlay who walks in the garden today is Monsieur Vidocq, and the Duc de Guise is Coco Lacour; we have exchanged great men for great principles. How free we are these days! Above all how free I was at my window, witness the fine gendarme at the foot of my stairs who was ready to shoot me in flight if I had spread my wings! There were no nightingales in my garden, but there were plenty of lively sparrows, cheeky and quarrelsome, found everywhere, in town and country, palaces and prisons, perching as cheerfully on the instruments of death as on a rose-bush: to those who can fly, what do the sufferings of the earth matter!

Book XXXV: Chapter 6: The Examining Magistrate – Monsieur Desmortiers

Paris, Rue d’Enfer, the end of July 1832.

BkXXXV:Chap6:Sec1

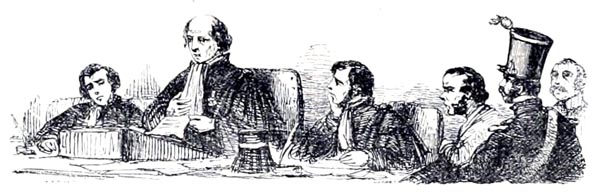

Madame de Chateaubriand obtained permission to see me. She had spent three months, during the Terror, in prison at Rennes with my two sisters Lucile and Julie; her imagination, still sensitive to it, could not bear the idea of prison. My poor wife had a violent attack of nerves on entering the Prefecture, and that was one more thing for which I was obliged to the ‘Centre Ground’. On my second day of detention, the examining magistrate, Monsieur Desmortiers, arrived accompanied by his clerk.

Monsieur Guizot had named a certain Monsieur Hello as public prosecutor as the Royal Court of Rennes, a writer and hence envious and irritable as all are who scribble on paper in a victorious cause.

Monsieur Guizot’s protégé, finding my name and that of Monsieur Hyde de Neuville mixed up in the trial he was pursuing at Nantes against Monsieur Berryer, wrote to the Minister of Justice, saying that if he were in charge, he would lose no time in arresting us and including us in the trial, both as accomplices and exhibits. Monsieur de Montalivet thought he should bow to Monsieur Hello’s advice; there had been a time when Monsieur de Montalivet had come to my house, humbly, to seek my advice and ideas on the elections and the freedom of the Press. The Restoration, which made a Peer of Monsieur de Montalivet, could not make a man of him, and that is no doubt why it sickens him these days.

Monsieur Desmortiers, the examining magistrate, thus entered my little chamber; his sugary manner hid, like a layer of honey, a tense and violent face.

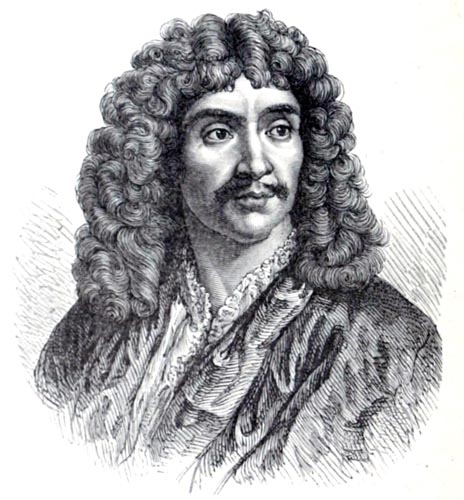

‘My name it is Loyal, I come from Normandy,

And I’m Sergeant of the Rod, despite your enmity.’

‘Molière’

Zigzag Journeys in Europe: Vacation Rambles in Historic Lands - Hezekiah Butterworth (p321, 1880)

Internet Archive Book Images

Monsieur Desmortiers was formerly of the congregation, a great communicant, a great legitimist, a great partisan of the decrees, and became a fanatical supporter of the Centre Ground. I begged this creature to take a seat with all the politeness of the ancien régime; I pulled up an armchair for him; I placed a little table before his clerk, with pen and ink on it; I sat facing Monsieur Desmortiers, and he, in a benign voice, read me the petty accusations which, duly proven, would have tenderly cut my throat: after which, he began his interrogation.

I declared once more that, as I did not recognise the existing political order, I had nothing to say, that I would sign nothing, that all this judicial process was superfluous, that they could spare themselves the effort and go; that, as for the rest, I was always charmed to receive Monsieur Desmortiers. (I set an initial example in refusing to recognize the judges which several Republicans have since followed. Note: Paris, 1840)

I saw that this manner of proceeding enraged the saintly man, who, having once shared my opinions, found my conduct made a mockery of his own; to this resentment was added the pride of a magistrate who thinks he is blessed by his function. He wished to argue with me; I could never have made him comprehend the difference between the social order and the political order. I would submit, I explained to him, to the former, since it represents natural law; I would obey civil, military and financial laws and those of the police and public order; but I owed no allegiance to political laws except in as much as they derived from Royal authority consecrated by the centuries, or from the sovereignty of the people. I was not stupid enough or devious enough to believe that the nation had been summoned, or consulted, and that the political order established had been the result of a national decision. If I were put on trial for theft, murder, arson or other social crimes and offences, I would respond to justice; but since a political process had been started against me, I had nothing to say to an authority which had no legal power, and in consequence, nothing to demand of me.

A fortnight passed away in this manner. Monsieur Desmortiers, whose fury I detected (a fury which he tried to communicate to the judges), tackled me with a confiding air, saying: ‘So you will not even tell me your illustrious name?’ During one of his interrogations, he read me a letter from Charles X to the Duke of Fitz-James, in which there was a phrase honouring myself. ‘Well, Sir,’ I said, ‘what does this letter signify? It is widely known that I remain loyal to my former King, and that I did not take the oath to Philippe. Apart from that, I am deeply moved by this letter of my exiled sovereign’s. In the course of his prosperity, he never said anything similar to me, and that sentence rewards me for all my efforts.’

Book XXXV: Chapter 7: My life at Monsieur Gisquet’s – I am set at liberty

Paris, Rue d’Enfer, the end of July 1832.

BkXXXV:Chap7:Sec1

Madame Récamier, to whom so many prisoners have owed consolation and deliverance, was brought to my new retreat. Monsieur de Béranger came over from Passy to tell me in song, during his friends’ rule, what it was like to be in gaol during that of mine: he could not have thrown the Restoration in my face more harshly. My great friend Monsieur Bertin came to administer the ministerial sacraments; an enthusiastic lady hastened from Beauvais in order to admire my glory; Monsieur Villemain performed a courageous action; Monsieur Dubois, Monsieur Ampère, Monsieur Lenormant, my wise and generous young friends, did not forget me; the Republican defence lawyer, Monsieur Charles Ledru, did not forsake me: in hopes of a trial, he exaggerated the affair, and would have foregone all his fees to have had the pleasure of defending me.

‘Madame Récamier’

Les deux France. Histoire d'un Siècle, 1789-1889. Récits d'une Aïeule Centenaire [i.e. Mme Loyseau de Laubespin] - Mathurin François Adolphe de Lescure (p33, 1889)

The British Library

Monsieur Gisquet had made me free of all of his rooms, as I mentioned; but I did not abuse the privilege. Only on a single evening did I descend to listen, while seated between him and his wife, to Mademoiselle Gisquet playing the piano. Her father scolded her and pretended that she had not played the sonata as well as usual. This little concert given by my host, en famille, with only myself as audience, was quite singular. While this pastoral scene was played out in fireside intimacy, police officers kept me away from my colleagues with blows from rifle butts and steel-tipped batons; yet what peace and harmony reigned in the policemen’s hearts!

I had the happiness of being able to enlist a favour, the favour of prison, similar to the one which I enjoyed, on behalf of Monsieur Charles Philippon; condemned for his talent to some months in detention, he was spending them in a sanatorium at Chaillot; summoned to Paris as a trial witness, he profited from the occasion and did not return to his lodgings; but he repented of it: in his hiding place, he was no longer free to see his child whom he loved: he regretted his prison, and not knowing how to return to it, he wrote me the following letter begging me to negotiate the thing with my host:

‘Sir,

You are a prisoner and will understand, or you would not be Chateaubriand. I am a prisoner too, a voluntary prisoner, since placing myself in a state of siege at a friend’s house, a poor artist like myself. I wished to flee the justice of the military tribunal with which I was threatened by the seizure of my newspaper on the 9th of this month. But, in order to remain in hiding, I have foregone the embraces of a child I idolize, an adopted daughter aged five, my joy and delight. This deprivation is a torment which I cannot long endure, it is death to me! I will give myself up, and they will throw me in Sainte-Pélagie, where I can only see my poor child infrequently, if they will still allow it, and only at set times, and where I will tremble for her health, and die of anxiety, if I cannot see her every day.

I, a whole-hearted Republican, address myself to you, Sir, a Legitimist, a serious man and a parliamentarian, I a caricaturist and a partisan of the most incisive political character, address you whom I do not know and who are a prisoner like myself, begging you to ask the Prefect of Police if he will let me return to the sanatorium to which they transferred me. I engage on my honour to present myself whenever I am required and I renounce any attempt to escape whatever tribunal there may be, if they will leave my poor child with me.

You will believe me, Sir, when I speak of honour and swear not to flee, and I am sure you will be my advocate, though the deepest politicians might see there a fresh proof of alliance between Legitimist and Republicans, men whose opinions match so well.

If my request is refused to such a guest, such an advocate, I will know I have nothing more to hope, and that I must be separated from my poor Emma for nine months.

Whatever, Sir, may be the result of your generous intervention, my thanks will be no less eternal, since I have no doubts of the urgent solicitations which your heart will suggest to you.

Accept, Sir, the expression of my sincere admiration and believe me your very humble and very devoted servant.

CH. PHILIPPON,

Proprietor of La Caricature (journal),

condemned to thirteen months in prison.

Paris, the 21st of June 1832.’

I obtained the favour Monsieur Philippon asked for: he thanked me in a note which demonstrates, not the magnitude of the service (which reduced to my client being watched over at Chaillot by a gendarme), but the hidden delights of love, which cannot be truly understood except by those who have felt them.

‘Sir,

I leave for Chaillot with my darling child.

I wish to thank you, but I feel words are too cold to express the gratitude I feel; I have reason to believe, Sir, that your own heart will suggest some eloquent phrases. I am sure I will not be mistaken in thinking it will inform you that I am not ungrateful, and will portray for you better than I can the storm of happiness in which your goodness has placed me.

Accept, I beg you, Sir, my sincerest thanks and deign to regard me as your servant, and the most affectionate of your servants.

CHARLES PHILIPPON.’

To this singular mark of my credit, I will add this strange witness to my fame: a young employee in Monsieur Gisquet’s office addressed some fine verse to me which was passed on to me by Monsieur Gisquet himself; since in the end justice was demanded: if a literate government attacked me nobly, the Muses defended me nobly. Monsieur Villemain courageously pronounced in my favour and in the Journal des Débats itself my great friend Bertin protested, signing an article against my arrest. Here is what the poet, who signed himself J. Chopin, office-worker wrote to me:

TO MONSIEUR DE CHATEAUBRIAND

AT THE POLICE PREFECTURE.

Bowing to your genius, I dare

To dedicate my lines to thee

And bear, a streamlet flowing to the sea,

This tribute to the god of metre there.

Misfortune now has fallen on your brow

Serene as ever in the tempest’s blast.

What cares the poet for this fleeting Now?

Your glory will remain.our hatreds pass.

Gracious enemy, your voice, its power,

Have even lent a charm to error,

Yet your eloquence at such an hour

Absolves your heart of it forever.

A King struck once before at your freedom;

You showed, at his severity,

Your greatness: he fell: and is gone,

Yet you see only his misery!

Oh, who could sound your endless loyalty

And force the tide to turn aside again?

But while one party may applaud your zeal,

Your glory is for all...take back your pen.

J. CHOPIN,

Office-worker.

Mademoiselle Naomi (I think that is Mademoiselle Gisquet’s Christian name) often walked alone in the little garden book in hand. She would steal a glance towards my window. How sweet to have been delivered from my chains, as in Cervantes, by my gaoler’s daughter! While I was taking the romantic air, young and handsome Monsieur Nay came to dissipate my dream. I saw him talking with Mademoiselle Gisquet in that manner which cannot deceive us, we creatures of other sylphs. I fell from my clouds, closed the window and abandoned the idea of letting my white moustaches be blown about by the winds of adversity.

After a fortnight, a decree dismissing the case set me at liberty on the 30th of June, to Madame de Chateaubriand’s great happiness: she would have died, I fear, if my detention had continued. She came in a cab to fetch me; I filled it with my bit of luggage so swiftly that I was already leaving the Ministry, and I returned to the Rue d’Enfer with that something achieved which misfortune grants to virtue.

If Monsieur Gisquet is known to posterity through history, perhaps he has arrived there in a sorry enough state; I desire what I have just written about him to serve as a counter-balance on behalf of a renowned enemy. I have nothing but praise for his kind attentions: Doubtless, if I had been condemned he would not have let me escape, but he and his family treated me with the propriety, the good grace, the sense of my position, of who I was and had been, that an educated administration had not shown, nor lawyers all the more brutal in that they acted against the weak and showed no fear.

Of all the governments which France has suffered in forty years, that of Philippe is the only one that has thrown me in gaol; it placed its hand on my head, on a head respected even by an angry conqueror; Napoleon lifted his arm but did not strike. And why that anger? I will tell you: I dared to protest in favour of right, against the tide of events, in a country in which I demanded liberty under the Empire, and glory under the Restoration; in a country where I alone take account not of brothers, sisters, children, joys, pleasures, but of graves. The recent political changes have parted me from my friends: some have gone on to make their fortunes, and they pass by my poverty swollen with dishonour; others have abandoned their homes exposed to insult. The generation so greatly in love with freedom has been sold: mean in their conduct, intolerable in their pride, mediocre or foolish in their writings, I expect nothing but disdain from that generation and I return it in kind; they have nothing about them that I understand, they know nothing of loyalty to a given oath, love of generous institutions, respect for one’s own opinion, scorn of success or gold, the felicity of sacrifice, the religion of weakness and misfortune.

Book XXXV: Chapter 8: A letter to the Justice Minister and his reply.

Paris, the end of July 1832.

BkXXXV:Chap8:Sec1

After the decree dismissing the case, I was left with one duty to fulfil. The offence of which I had been accused was linked to that for which Monsieur Berryer had been detained in Nantes. I had been unable to explain this to the examining magistrate since I had refused to recognize the tribunal’s competence. In order to repair the damage my silence may have caused Monsieur Berryer, I wrote the letter you are about to read, to the Minister of Justice, and made it public through the newspapers.

‘Paris, this 3rd of July 1832.

Monsieur le Ministre de la Justice,

Allow me, in writing to you, to fulfil a duty of conscience and honour in the interests of a man who has been deprived of his liberty for too long.

Monsieur Berryer the Younger, during his interrogation by the examining magistrate in Nantes on the 18th of last month, replied: That he had seen Madame la Duchesse de Berry; that he had advised her with the respect due to her rank, her courage and her misfortunes, of his personal opinions and that of his honourable friends regarding the present situation in France, and on the consequences of her Royal Highness’ presence in the West.

Monsieur Berryer, expanding on this vast subject with his usual skill, had summarised it for her in this way: No war, foreign or civil, even supposing it crowned with success, can suppress or rally opinion

Questioned about the honourable friends of whom he had just spoken, Monsieur Berryer said markedly: That serious men having maintained in the present circumstances an opinion in agreement with his own, he had thought it a duty to support his advice with their authority; but that he could not name them without their consent.

Monsieur le Ministre de Justice, I am one of those people Monsieur Berryer consulted. Not only did I approve his advice, but I even wrote a letter construed in that sense. It would have been handed to Madame la Duchesse de Berry, in the event that the Princess had really been on French soil, which I did not believe to be the case. That first note being unsigned, I wrote a second which I signed and in which I begged that intrepid mother of Henri IV’s scion, with more insistence, to leave a land split by such discord.

Such is the statement I owe Monsieur Berryer. The true guilt, if there is guilt, is mine. This statement will serve I hope to initiate a prompt deliverance for the prisoner of Nantes; it will only leave the burden of a deed weighing on my head which was innocent without doubt, but whose consequences, in the final result, I accept completely.

I have the honour to be, etc.

CHATEAUBRIAND.

84, Rue d’Enfer-Saint-Michel.

Having written to Monsieur le Comte de Montalivet, on the 9th of last month, regarding the affairs of Monsieur Berryer, Monsieur le Ministre de l’Interieur did not even think it necessary to let me know he had received my letter; as I am greatly concerned to learn the fate of this one, which I have the honour to write to Monsieur le Ministre de Justice today, I would be infinitely obliged to him if he would have his office acknowledge its receipt.

CH.’

The Justice Minister’s reply was prompt; here it is:

‘Paris, the 3rd of July.

Monsieur le Vicomte,

The letter which you have addressed to me, containing information which may aid the course of justice, I have had sent on immediately to the King’s Prosecutor on the Nantes tribunal, so that it may be included in the evidence in the case that has commenced against Monsieur Berryer.

I am with respect, etc,

Keeper of the Seal,

BARTHE.

By this response Monsieur Barthe graciously reserved the right to institute fresh proceedings against me. I remember the proud disdain of the great men of the ‘Centre Ground’ when I let slip the possibility of violence against myself or my writings. What! Goodness, why ward off imaginary dangers? Who could be embarrassed by my opinions? Who would dream of touching a single hair of my head? Friends and supporters of the cooking-pot, intrepid heroes of peace at any price, nevertheless you must own to your Terror, that of the police and the law, your Paris under siege, your thousand Press trials, your military commission to condemn the author of Cancans to death; you still plunged me into gaol; the punishment applicable to my crime was nothing less than capital punishment. It would have been a pleasure to lose my head, if, thrown into the scales of justice, that might have tilted them towards the side of honour, glory and my country’s freedom!

Book XXXV: Chapter 9: Charles X offers to pay me a Peer’s pension: my response

Paris, Rue d’Enfer, end of July 1832.

BkXXXV:Chap9:Sec1

I was more than ever determined to resume my exile; Madame de Chateaubriand, frightened by my adventure, already wished to be far away; it was not a question of deciding where to pitch our tents. The great difficulty was to find enough money to live in a foreign land and firstly to pay my debts which were attracting threats of pursuit and seizure.

The first year of an Embassy always ruins the Ambassador: that is what happened to me in Rome. I resigned at the advent of Polignac’s Ministry, and had added to my usual poverty sixty thousand francs in loans. I knocked at all the Royalist banks, none opened to me: I was advised to try Monsieur Lafitte. Monsieur Lafitte advanced me ten thousand francs which I immediately gave to my most hard-pressed creditors. From the proceeds of my pamphlets I recovered that amount which I repaid him with thanks; but thirty thousand francs still remained unpaid besides my old debts, some of which had grown beards they were so aged; unfortunately those beards were golden ones, whose annual trim came from my chin.

Monsieur le Duc de Lévis, returning from his trip to Scotland, told me on behalf of Charles X that the Prince wished to resume paying me a Peer’s pension; I thought I should refuse the offer. The Duc de Lévis returned to the issue when he saw that on leaving prison I was in the deepest embarrassment, gaining nothing by my house and garden in the Rue d’Enfer, and harassed by a swarm of creditors. I had already sold my silverware. The Duc de Lévis brought me twenty thousand francs, telling me in a noble manner that it was merely the two years of income which the King realised he owed me, and that my debts in Rome were simply debts of the Crown. That sum set me free, and I accepted it as a temporary loan, writing the King the following letter (You will read about my conversation with Charles X on the subject of this loan during my first trip to Prague. Note: Paris, 1834):

‘Sire,

In the midst of the disasters with which it has pleased God to sanctify your life, you have not forgotten those who suffer at the foot of Saint-Louis’ throne. You deigned, some months ago, to convey to me your generous suggestion of resuming my Peer’s pension which I renounced on refusing to take the oath to an illegitimate power; I know Your Majesty has servants poorer than I am and worthier of your kindness. But the last works I published have caused me difficulties and have excited persecution; I have tried in vain to sell the few things I possess. I am forced therefore to accept, not the annual pension which Your Majesty proposes I should levy on Royal poverty, but a temporary aid to free me from the embarrassments which prevent my regaining a sanctuary where I might live by my own labour. Sire, I must be very unfortunate to have become a burden, for even a moment, on the Crown which I have supported with all my efforts and which I will continue to serve for the rest of my life.

I am with the profoundest respect, etc.

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

Book XXXV: Chapter 10: A note from Madame la Duchesse de Berry – A letter to Béranger – Departure from Paris

Paris, Rue d’Enfer, 1st to the 8th of August 1832.

BkXXXV:Chap10:Sec1

My nephew Count Louis de Chateaubriand, for his part, advanced me a similar sum of twenty thousand francs. Thus freed of material obstacles I made preparations for my second departure. But a matter of honour restrained me: Madame la Duchesse de Berry was on French soil; what would become of her, and should I not stay in the country to which her perils might summon me? A note from the Princess which arrived from the depths of the Vendée served to set me free.

‘Portrait of Marie Caroline Ferdinande Louise de Naples, Wife of Charles Ferdinand, Duke de Berry, in the Park de Bagatelle in the Bois de Boulogne, Paris’

François Pascal Simon Gérard (Baron), 1820 - 1837

The Rijksmuseum

‘I am writing to you, Monsieur le Vicomte, regarding that provisional government, which I had thought to form when I was ignorant as to when, and even if, I might return to France, and in which I was told you had consented to take part. It did not in fact exist, since it never met, and some of its members only agreed in order to offer me advice which I could not follow. I am not at all ungrateful to them for it. You judged, according to the report made to you, my situation, and that of those regions which have better reason than I to understand the effects of a fatal influence, in a manner which I did not choose to accept, and I am sure that if Monsieur de Chateaubriand had been with me, his noble and generous heart would have equally rejected it. I nonetheless rely on the good offices of various individuals and even on the advice of people who formed part of the provisional government, the choice of whom was dictated by their known zeal and devotion to the Legitimacy in the person of Henri V. I hear that it is still your intention to leave France, and I would regret it greatly if I were able to draw you closer to me; yet you have weapons which strike from a distance and I hope you will not cease to fight for Henri V.

Believe wholly, Monsieur le Vicomte, in my esteem and friendship.

M. C. R’

In this note, Madame neglected my services to her, and accepted nothing of the advice I had dared to give her in the note of which Monsieur Berryer had been the bearer; she even seemed a little wounded by it, even though she recognised that a fatal influence had lead her astray.

Thus, set at liberty and disengaged from everything, today the 7th of August, having nothing left to do but go, I wrote a farewell letter to Monsieur de Béranger, who had visited me in prison.

‘Paris, the 7th of August 1832.

To Monsieur de Béranger,

Sir, I wish to say farewell and to thank you for remembering me; time is short and I am forced to leave without having the pleasure of seeing and embracing you. I am ignorant of the future: is there an obvious future for anyone these days? We are not in an age of revolution, but of social transformation: now, transformations take place slowly, and the generations which are part of the period of metamorphosis perish wretchedly and obscurely. If Europe (as she may well be) is in an age of decrepitude that is another matter: she will produce nothing, and will fade away in an impotent chaos of passions, morals and doctrines. In that case, Sir, you will have sung over a tomb.

I have fulfilled all my engagements, Sir: I returned to your singing; I have defended what I came to defend; I have survived the cholera: I am returning to the mountains. Do not break your lyre as you threatened; I owe to it one of my most glorious titles to human remembrance. Keep France smiling and weeping: since, by a secret you alone know, it seems that in your popular songs the words are happy yet the music is plaintive.

I recommend myself to your friendship, and to your Muse.

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

I am to set out tomorrow. Madame de Chateaubriand will join me at Lucerne.

Book XXXV: Chapter 11: Journal from Paris to Lugano

Basel, 12th of August 1832.

BkXXXV:Chap11:Sec1

Many men die without losing sight of their neighbouring steeple; I cannot find the steeple which will see my death, In quest of a sanctuary in which to finish my Memoirs, I set off again, dragging behind me an enormous trunk full of papers, diplomatic correspondence, confidential notes, and letters from Ministers and Kings; it was History carried pillion by Romance.

I saw Monsieur Augustin Thierry at Vesoul, in retirement at his brother the Prefect’s house. As he has previously sent me, in Paris, his History of the Norman Conquest, I went to thank him. I found a youngish man in a room with half-closed blinds; he was almost blind; he tried to rise to welcome me, but his legs no longer bore his weight and he fell into my arms. He blushed when I expressed my sincere admiration for him: it was then that he told me that his work was based on mine, and that it had been while reading the Battle of the Franks in Les Martyrs that he conceived the idea of a new way of writing history. When I took my leave of him, he tried hard to follow me and dragged himself as far as the door by leaning on the wall: I left moved by so much talent and such misfortune.

Via Vesoul, Charles X, had returned after his long exile, he who was now making sail towards a fresh exile which would be his last.

I passed the frontier without incident with all my clutter: let us see whether, on the far side of the Alps, I cannot enjoy Swiss freedom and Italian sun, needed by my opinions and my years.

On entering Basel, I encountered an old Swiss, a customs officer; he made me undergo un bedit garandaine d’in guart d’hire: a little quarantine for a quarter of an hour; my luggage was taken into a cavern; something was set in motion which sound like a loom down below; a smell of vinegar arose, and thus free of French contagion, the good Swiss released me.

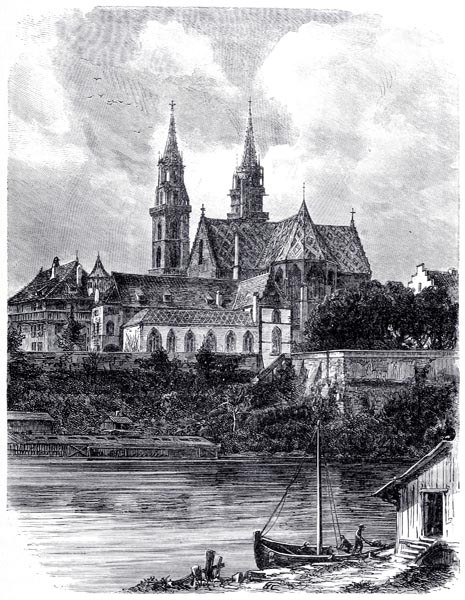

‘The Pfalz Terrace and the Cathedral Basel’

Switzerland: its Scenery and People - Theodor Gsell-Fels (p425, 1881)

The British Library

I said, in the Itinerary, while speaking of the storks of Athens: ‘From the heights of their nests, that revolution cannot touch, they saw the human race changing beneath them: while impious generations rose on the tombs of religious generations, the young storks always fed their aged fathers.’

I found a stork’s nest at Basel which I had left behind six years previously; but the hospital on whose roof the stork had built its nest was no Parthenon, and the sun over the Rhine is not that which shines on the Cephisus, the Council House is not the Aeropagus. Erasmus is not Pericles: yet there is something Roman and Germanic about the Rhine, the Black Forest, and Basel. Louis XIV extended the borders of France to the gates of this city, and three hostile monarchs passed through it in 1813 in order to sleep in Louis le Grand’s bed, defended in vain by Napoleon. Let us go and view Holbein’s The Dance of Death; it expresses human vanity.

The Dance of Death (if there was not already an accurate painting of it by then) took place in Paris, in 1424, in the Cemetery of the Innocents: it came to us from England. The representation of the spectacle was set down in fresco paintings; they were on view in the cemeteries of Dresden, Lübeck, Minden, La Chaise-Dieu, Strasbourg, and Blois in France, and Holbein’s pen immortalised those funereal delights in Basel.

‘Such is the Power, & Such is the Strife, That Ends the Masquerade of Life’

The English Dance of Death, from the Designs of Thomas Rowlandson - William Combe, Thomas Rowlandson (p228, 1903)

Internet Archive Book Images

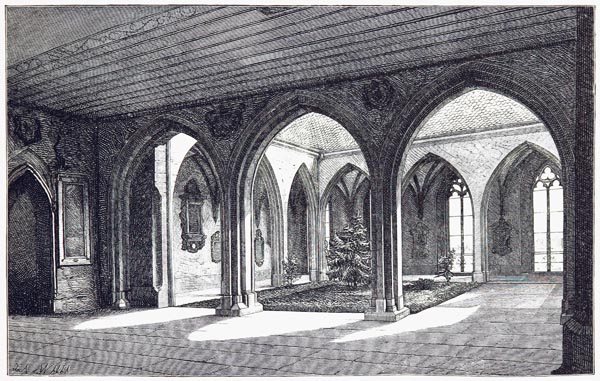

These danses macabres by great artists have in turn been carried off by Death, who spares not its own follies: of the work in Basel there only remain six truncated sections, on the walls of the cloister and deposited in the University library. A watercolour has preserved the overall design of the work.

These grotesques, in essence terrifying, have a Shakespearean quality, a mixture of the comic and the tragic. The characters display vivid expressions: rich and poor, young and old, men and women, Popes, Cardinals, priests, Emperors, Kings, Queens, Princes, Dukes, nobles, magistrates, soldiers, all struggle and argue with and against Death; none accept it with a good grace.

Death is infinitely varied, but always a farce like life, which is merely a grave comedy. This Death satirically painted is minus a leg like the wooden-legged beggar he accosts; he affects a mandolin at his bony back, like the musician he drags along. He is not always bald; strands of hair, blond, brown, grey hang down the skeleton’s neck making it more dreadful by rendering it more lifelike. In one of the panels Death almost has flesh, is almost a young man, and carries a young girl away with him who gazes at herself in a mirror. In his satchel Death has a schoolboy’s jeering tricks: he cuts a cord with scissors by which a dog leads its blind owner, and the blind man is two steps away from an open ditch; elsewhere, Death in a little cloak, approaches one of his victims with satirical gestures, like a Pasquin. Holbein was able to capture the idea of the very essence of this tremendous mockery: in reliquaries skulls always seem to be smirking because their teeth are revealed; it is a smile without lips to frame it and form the smile. What do they smile at: nothingness, or life?

Basel Cathedral pleased me, and especially the ancient cloisters. Walking around the latter, dense with funeral inscriptions, I found the names of various reformers. Protestantism chose its time and place badly when it located itself among Catholic monuments; what is has reformed is less visible than what it has destroyed. Those dry pedants who thought to recreate primitive Christianity, within a Christianity that has moulded society for fifteen centuries, proved unable to erect a single monument. What would such a monument have echoed? How could it relate to its time? Men in the age of Luther and Calvin were not made like Luther and Calvin; they were formed like Leo X with the spirit of Raphael, or Saint Louis with a Gothic spirit; a minority believed in nothing, the majority believed in everything. Has not Protestantism for temples only schoolrooms, and for churches the cathedrals it has devastated? There its nakedness is revealed. Jesus Christ and his apostles doubtless failed to resemble the Greek and Romans of their era, but they did not come to reform an ancient religion; they came to establish a new religion, to replace gods by the One God.

‘The Cloisters of the Cathedral of Basel’

Switzerland: its Scenery and People - Theodor Gsell-Fels (p429, 1881)

The British Library

BkXXXV:Chap11:Sec2

Lucerne, 14th of August 1832.

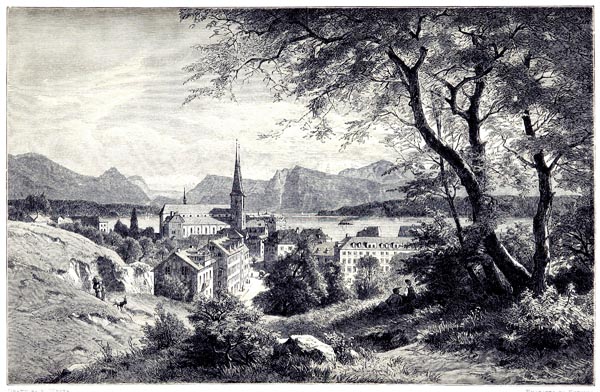

The road from Basel to Lucerne through Aargau, offers a series of valleys some of which resemble the valley of Argèles, without the skies of the Spanish Pyrenees. At Lucerne, mountains variously grouped, tinted, stacked in tiers, outlined against the heavens, end by retiring behind one another and vanishing into the distance, in the neighbouring snows of Saint Gothard. If you removed Mount Rigi and Mount Pilatus, but retained the hills clothed with greenery and fir trees which immediately border the Lake of the Four Cantons (Lake Lucerne), you would create an Italian lake.

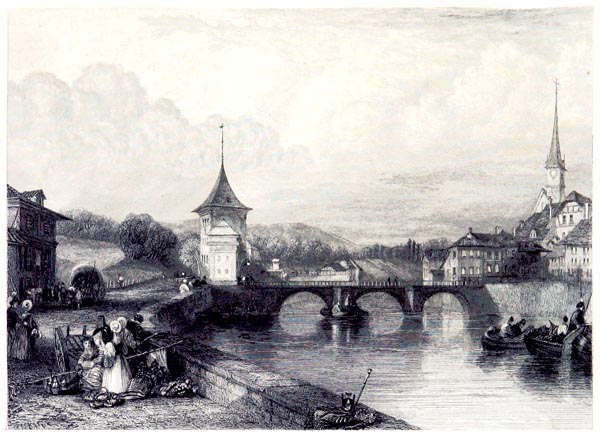

‘Lucerne’

Switzerland: its Scenery and People - Theodor Gsell-Fels (p237, 1881)

The British Library

The arcades of the cemetery cloister with which the Cathedral is surrounded are like boxes from which you enjoy this view. The cemetery monuments have as standard a little iron cross carrying a gilded Christ. In the sun’s rays they are like so many points of light escaping from the tombs; at intervals there are fonts of holy water in which branches are soaking with which one can bless the ashes of the departed. I wept for no one in particular there, but I made the purifying dew descend on that silent community of unfortunate Christians, my brothers. One epitaph told me: Hodie mihi, cras tibi: I today, you tomorrow; another: Fuit homo: this was a man; another: Siste Viator, abi, viator: stop passer-by; go passer-by. And I wait on tomorrow; and shall have been a man; and passer-by I halt; and passing by I go. Leaning against an arcade of the cloister, I gazed for hours at William Tell’s and his companions’ theatre of action: the theatre of Helvetic freedom so well sung and pictured by Schiller and Johannes von Müller. My eyes searched that vast picture for the presence of the most illustrious dead, and my feet trampled the ashes of the most anonymous of them.

Seeing the Alps again four or five years ago, I asked myself what I had come for: how would I answer today? How would I answer tomorrow or the next day? Pity me who cannot grow old and is forever ageing!

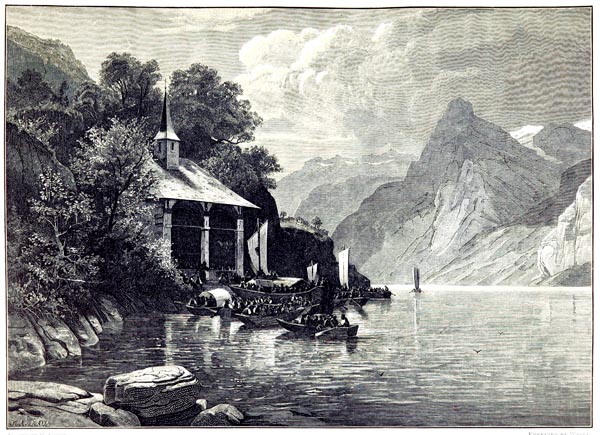

Lucerne, 15th of August 1832.