François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXXIV: Geneva, Paris, Cholera 1831-1832

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXXIV: Chapter 1: Introduction

- Book XXXIV: Chapter 2: The trial of the Ministers – Saint-Germain-L’Auxerrois – The pillaging of the arch-diocese

- Book XXXIV: Chapter 3: My pamphlet on The Restoration and the Elective Monarchy

- Book XXXIV: Chapter 4: The Études Historiques

- Book XXXIV: Chapter 5: Before my departure from Paris

- Book XXXIV: Chapter 6: Letters and verses to Madame Récamier

- Book XXXIV: Chapter 7: My journal for 12th July to 1st September 1831 – Monsieur de Lapanouze’s clerks – Lord Byron – Ferney and Voltaire

- Book XXXIV: Chapter 8: My journal continued – Vain endeavours in Paris

- Book XXXIV: Chapter 9: My journal continued – Messieurs Carrel and Béranger

- Book XXXIV: Chapter 10: A song of Béranger’s: and my reply – A return to Paris for Briqueville’s proposal

- Book XXXIV: Chapter 11: Baude and Briqueville’s proposal regarding the banishment of the elder branch of the Bourbons

- Book XXXIV: Chapter 12: A letter to the author of Nemesis

- Book XXXIV: Chapter 13: The conspiracy of the Rue des Prouvaires

- Book XXXIV: Chapter 14: Incidents of Plague

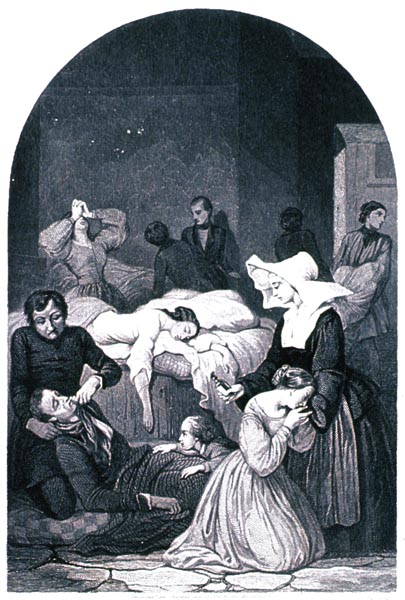

- Book XXXIV: Chapter 15: Cholera

Book XXXIV: Chapter 1: Introduction

Infirmerie de Marie-Thérèse, Paris, October 1830.

BkXXXIV:Chap1:Sec1

Emerging from the fracas of the Three Glorious Days, I was astonished at beginning the fourth part of this work with a feeling of profound calm; it seemed to me that I had doubled the Cape of Storms, and penetrated into a region of peace and silence. If I had died on the 7th of August of that year, the closing words of my speech to the Chamber of Peers would have been the last lines of my story; my catastrophe, being also that of the twelve centuries past, would have enhanced my memory. My drama would have ended magnificently.

But I am not living under threat; I have not been dragged to earth. Pierre de l’Estoile wrote this page of his journal the day after the assassination of Henri IV:

‘And here I finish, with the life of my King (Henry IV), the second book of my melancholy history and my vain and curious researches, public as well as private, often interrupted for a month at a time by the sad evenings and weary nights I have endured, especially this last, because of the death of my King.

I would have proposed to end my ephemeredes with this book; but so many new and curious occurrences have presented themselves because of that notable event, that I am continuing with another, which will be as lengthy as God pleases; and I doubt that will be very long.’

L’Estoile saw the death of the first Bourbon; I have just seen the fall of the last; should I not close here the register of my melancholy history and my vain and curious researches? Perhaps; but so many new and curious occurrences have presented themselves because of that notable event, that I am continuing with another.

Like L’Estoile, I lament the misfortunes of Saint-Louis’ line; yet, I must confess, there is a certain internal satisfaction mixed with my sadness; I reproach myself for it, but cannot avoid it: the satisfaction is that of a slave freed from his chains. When I quit being a soldier and a traveller, I felt sad; now I experience joy, a convict liberated as I am from the galleys of society and Court. Faithful to my principles and my oath, I have betrayed neither liberty nor the King; I carry away neither riches nor honour; I leave as poor as when I came. Happy to end a political career hateful to me, I return with delight to rest.

Bless you, my dear in-born freedom; the soul of my life! Come: recount to me my Memoirs, this alter ego whose confidante, ideal and Muse you are. Hours of leisure are suited to tales: shipwrecked, I will continue to tell the fishermen on shore of my disaster. Returned to my first feelings, I become again a free man and a traveller; I end my course as I began. The circle of my days, which closes, leads me back to my point of departure. On the road that I once trod as a carefree conscript I will march as an experienced veteran, demobilisation papers in my shako, stripes showing how long I have served on my arm, a haversack of years on my back. Who knows? Perhaps I will discover stage by stage the reveries of my youth? I will summon many dreams to my aid, to defend myself against that horde of realities which breeds in time past, like dragons hidden amongst the ruins. It is for me to tie together the two ends of my existence, to confound distant epochs, to intermingle the illusions of differing times, since the banished Prince I will meet on leaving my paternal hearth, I encounter now in exile in travelling to my last home.

Book XXXIV: Chapter 2: The trial of the Ministers – Saint-Germain-L’Auxerrois – The pillaging of the arch-diocese

Paris, April 1831.

BkXXXIV:Chap2:Sec1

I wrote that little introduction to this section of my Memoirs rapidly, in October last year; but could not continue the work because I had another in hand; it involved finishing the book which ends the edition of my Complete Works. I was even distracted from that work, firstly by the trial of the Ministers, then by the sacking of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois.

The trial of the Ministers and the troubles in Paris were no great thing to me: after the trial of Louis XVI and the revolutionary insurrections, every other judgement and insurrection seemed trivial indeed. The Ministers, brought from Vincennes to hear their sentence pronounced, arrived via the Rue d’Enfer. From the depths of my retreat I heard the sound of their carriage. What events have taken place outside my door! The men’s defence lawyers were not up to the job. No one took the thing seriously enough: the prosecutor over-dominated the proceedings. If my friend the Prince de Polignac had selected me as his second, how I would have glared at those oath-breakers set up as judges over an oath-breaker: ‘What,’ I would have said to them, ‘do you dare to be my client’s judges! You are the ones who, tarnished utterly by your oaths, dared to make him commit the crime of ruining his master while thinking he was serving him; you the provokers of it; you who urged him to present the decrees! Change places with him whom you pretend to judge: from accused he shall become accuser. If we have merited punishment, it is not from you; if we are guilty, it is not towards you, but towards the people: they wait for us in the courtyard of your palace, and we will let them have our heads.’

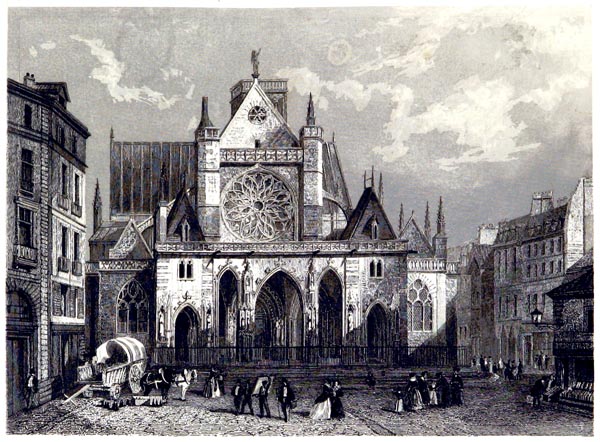

After the trial of the Ministers came the scandalous affair of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois. The Royalists, full of excellent qualities, but sometimes foolish and often provocative, never considering the consequences of their actions, always thinking to re-establish the Legitimacy by choosing to wear a coloured cravat or a flower in their buttonhole, caused deplorable scenes. It was evident that the revolutionary party would profit from the church service marking the anniversary of the Duc de Berry’s death to make trouble; now, the Legitimists were not strong enough to oppose them, and the government was not well enough established to maintain order; also the church itself was vandalised. An apothecary, a man of progress, and follower of Voltaire bravely conquered a steeple from 1300, and a cross which had already been pulled down by other Barbarians towards the end of the ninth century.

‘Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois’

Histoire Physique, Civile et Morale de Paris...Quatrième Édition - Jacques Antoine Dulaure (p325, 1846)

The British Library

The devastation of the arch-diocese, the profanation of holy things and processions imitating those in Lyons followed the noble deeds of this enlightened pharmacist. They lacked the tumbrels full of victims; but they had Punch, maskers, and all the delights of the carnival. The procession, sacrilegiously burlesqued, travelled along one bank of the Seine while the National Guard marched down the other, apparently hastening to its aid. The river separated order and anarchy. I am told that a wit looking on, seeing the books and chasubles floating in the Seine, said; ‘What a pity they didn’t throw the archbishop in too!’ A profound comment, indeed, since an archbishop drowning would have been fun to watch: it would have been a great stride towards liberty and enlightenment! We, ancient witnesses of ancient events, are forced to tell you that you see here only pale and miserable imitations. You still possess the revolutionary instinct; but you lack the energy for it; you are only criminals in imagination; you wish to do evil, but your hearts lack courage and your arms strength; you would see other massacres, but you will not set your hands to the work. If you want the July Revolution to be great and remain great, do not treat Monsieur Cadet de Gassicourt as a true hero, or Mayeux as imaginary.

Book XXXIV: Chapter 3: My pamphlet on The Restoration and the Elective Monarchy

Paris, End of March 1831.

BkXXXIV:Chap3:Sec1

I was far from correct in thinking that by leaving the July days behind me I would be entering a realm of peace. The fall of three sovereigns obliged me to justify myself to the Chamber of Peers. The proscription of those kings did not allow me to remain silent. From another direction, Philippe’s newspapers demanded to know why I had refused to serve a revolution which had consecrated the principles I propagated and defended. I was forced to utter universal truths and explain my personal conduct. An extract from a little pamphlet which was wasted (De la Restauration et de la Monarchie élective) will continue the thread of my story and that of the history of my times:

‘Stripped of the present, and having only an uncertain future this side of the tomb, it is important that my memory is not harmed by my silence. I ought not to be reticent about a Restoration in which I played so great a part, which is insulted every day, and which was finally proscribed before my eyes. In the Middle Ages, in times of disaster, they imprisoned a churchman in a tower where he lived on bread and water for the good of the people. I bear a fair resemblance to that twelfth century monk: through the skylight of my expiatory cell, I preached my last sermon to the passers-by. Here is the gist of that sermon; I foreshadowed it in my last speech at the rostrum of the Chamber of Peers: the July Monarchy has to be in a state of utter glory or one of laws of ‘exception’; it lives and dies by the Press; without glory it will be devoured by liberty; if it attacks that liberty, it will perish. It would be a fine thing to see us, after we chased three kings beyond the barricades to win Press freedom, raising new barricades against that freedom! And yet, what else is there to do? Will the redoubled action of the tribunes and the laws suffice to contain the writers? A new government is a child that cannot walk without support. Shall we return the nation to its swaddling clothes? Can the dreadful infant that sucked blood, while held in the arms of victory in so many bivouacs, not throw them off? Only an old tree-stump rooted deeply in the past can brave with impunity the storms of liberty and the Press........

To hear the proclamations these days, one would think the exiles in Edinburgh were the nicest people in the world, and had never done anything wrong. Today, the present is lacking only one thing: the past, a small matter! As though the centuries were not resting on one another and the last one to arrive could hang there in mid-air! Our pride has to be shocked by the memories, erasing of the fleur-de-lis, proscribing of the people and names, that family, heir of a thousand years, has left an immense void by its removal: it is felt everywhere. Those individuals, so weak in our eyes, have weakened Europe by their fall. If events ever produce their natural effects, and lead to serious consequences, then Charles X in abdicating will have taken with him in his abdication all the Gothic kings, the great vassals of the past in suzerainty to the Capets.............

‘Holyrood Palace’

Select Views of the Royal Palaces of Scotland - William Brown, Secretary to the Literary and Antiquarian Society of Perth (p87, 1840)

The British Library

We are marching towards universal revolution. If the transformation which is taking place follows its course and meets with no obstacles, if popular understanding continues its progressive development, if the education of the middle classes is not interrupted, the nations will achieve an equal level of freedom; if that transformation is halted, the nations will achieve an equal level of tyranny. The tyranny will not last, because of the advance of enlightenment in this age, but it will be harsh, and a lengthy period of social dissolution will follow.

Preoccupied as I am with these ideas, one can see why I have remained faithful, as an individual, to what would seem to best safeguard public freedoms, the least perilous path by which we might achieve the remainder of those freedoms.

It is not that I wish to be a whining prophet of sentimental politics, sporting the white feather and reiterating the commonplaces of Henri IV’s age. Traversing with my eyes the space which separates the tower of the Temple from the Palace in Edingburgh I would find, doubtless, as many heaped-up calamities as there are centuries accumulated by a noble race. A grieving woman above all was charged with the heaviest burden, and the greatest; there is not a heart which does not break on remembering her: her sufferings mounted so high they became one of the grandeurs of the Revolution. But in the end one is not forced to be a king. Providence sends personal afflictions to whom it wishes, always brief, because life itself is short; and those afflictions hardly count in the general destiny of nations.....

But the proposition that banishing the deposed family forever from French territory is a corollary to deposing that family, that corollary does not hold conviction with me. It would be pointless for me to seek a place among the various categories of people who are attached to the present order of things...

There are men, who, after preaching sermons to the one and indivisible Republic, to the Directory of five persons, to the Consulate of three, to the Empire of one alone, to the first Restoration, the Act additional to the Imperial constitution, and the second Restoration, still have something left to utter regarding Louis-Philippe: I am not that well-stocked.

There are men who broke their word on the Place de Grève, in July, like those Roman knights who play at odd or even, among the ruins: they consider anyone who does not reduce politics to private interest as a fool and a madman: I am a fool and a madman.

There are timorous people who would have preferred not to take the oath, but who imagined themselves, their grandparents, their grandchildren and all property owners murdered if they did not stutter it out: that is a physical infirmity which I have not yet experienced; I will wait, and if it afflicts me, I will tell you.

There are great lords of the Empire, tied to their pensions by sacred and indissoluble bonds, whoever’s hands they themselves might fall into: a pension is a sacrament in their eyes; it is stamped with the cachet of priesthood or marriage; no pensioned head can cease to be: pensions being in the care of the Treasury, they remain in the care of that same Treasury: I make it a habit to divorce myself from fortune; too old for her, I desert her, for fear lest she will not leave me.

There are noble Barons of the Throne and Altar, who did not betray the decrees; no, but the inadequate means employed to execute those decrees heated their bile; indignant that tyranny had failed, they went to seek another ante-chamber: it is impossible for me to share their indignation and their hearth.

There are men of conscience who were only oath-breakers in breaking their oath, who having yielded to force are nevertheless on the side of right; they wept for poor Charles X, whom they had first led to his doom with their advice, and then put to death according to their oath; but if ever he or his race return, they will be warriors of the Legitimacy: I have always been devoted to death, and I am the whole cortege of the old monarchy as his dog is a poor man’s.

Finally there are the loyal knights who in their pockets keep dispensations of honour and permits for disloyalty: I am not one of them.

I was a man of the potential Restoration, the Restoration of all kinds of freedom. That Restoration took me for an enemy; it is gone: I must submit to its fate. Should I attach the few years left to me to a new fortune, like the hems of those robes that women trail from place to place, and on which all the world may tread? As the leader of the younger generation, I would be suspect; to follow them is not my role. I know very well that none of my faculties have aged; I understand my century better than ever; I penetrate the future more boldly than anyone; but fate has made its pronouncement; to end one’s life fittingly is an essential task for a public man.’

Book XXXIV: Chapter 4: The Études Historiques

BkXXXIV:Chap4:Sec1

Finally, my Études Historiques have appeared; I record the Foreword here: it is a true page of my Memoirs, it continues my story to the moment when I wrote it:

Foreword

‘Remember, in order not to lose sight of the world’s course, that at that epoch (the fall of the Roman Empire). there were citizens who like me searched the archives of the past in the midst of present ruins, who wrote the annals of ancient revolutions to the sound of new ones; they and I took for a table, in the crumbling edifice, the stone fallen at our feet, while awaiting that which would crush our skulls.’

(Études Historique, Book Vb, page 175)

‘The Last of the Goths Leaving Italy’

The Story of the Greatest Nations, from the Dawn of History to the Twentieth Century - Edward Sylvester Ellis, Charles Francis Horne (p147, 1900)

Internet Archive Book Images

‘In what remains to me of life, I would not wish to re-live the eighteen months which have just passed. No one has any idea of the violence done to me; I have been forced to remain mentally detached for ten, twelve or fifteen hours a day, detached from everything happening around me, in order to give myself simply to the composition of a work of which no one will read a single line. Who will read four fat volumes, when they have enough trouble reading the pages of a newspaper? I was writing ancient history, and modern history knocked at my door: in vain I called out to it: “Wait, I will come to you”; it passed by to the sound of cannon, carrying away with it three generations of kings.

And how happily the times suited the very nature of those Studies! They pulled down crosses, they pursued priests; and the pages of my tale were a matter of crosses and priests; they banished Capets, and I am publishing a history eight centuries of which is concerned with Capets. The longest and final work of my life, that which has cost me most research, care and time, that in which I have aired perhaps the largest number of facts and ideas, appears when it would find no readers; it is if I had thrown it into a well where it will sink between the heap of rubble following it. When a society makes and unmakes itself, when the life of one and all goes into it, when one is not sure of the future for a moment, then who cares what his neighbour does, thinks, or says? Do Nero, Constantine, Julian, the Apostles, the Martyrs, the Church Fathers, the Goths, the Huns, the Vandals, the Franks, Clovis, Charlemagne, Hugh Capet and Henri IV really matter; do the problems of the ancient world really matter, when we are concerned with the problems of the modern one? Is it not a sort of wool-gathering, a sort of feebleness of mind to occupy oneself with literature at such a moment? True: but this wool-gathering has noting to do with my brain, it has its antecedents in my wretched poverty. If I had not made so many sacrifices for my country’s liberty, I would not have been obliged to enter into contracts which have had to be fulfilled in circumstances doubly deplorable to me. No author has suffered a like experience; God be thanked, it is over: I no longer have to sit amongst the ruins despising a life which I disdained to follow in my youth.

After these quite natural complaints, which escape me involuntarily, a thought comes to console me; I began my literary career with a work in which I envisaged Christianity in the context of philosophy and history: I began my political career with the Restoration, I finished it with the Restoration. It is not without a secret satisfaction that I find myself so in accord with myself.’

Book XXXIV: Chapter 5: Before my departure from Paris

Paris, April 1831.

BkXXXIV:Chap5:Sec1

I have never abandoned the resolution I conceived at the time of the July troubles. I am pre-occupied with obtaining the means of living in a foreign country, means difficult to obtain, since I have none. The editor who acquired my works has nearly bankrupted me, and my debts force me to seek someone who will make me a loan.

Whatever happens, I am going to Geneva with the money owing to me from the sale of my last pamphlet (De la Restauration et de la Monarchie élective), I leave my proxy to sell the house, in which I write this page, in short order. If I find a shopkeeper in my bed, I can find another bed outside France. Among these uncertainties and upheavals, until I am established somewhere, it will be impossible for me to pick up the tale of my Memoirs from the point at which I interrupted them. (This relates to my literary career and my political career, both left behind, lacunas which are now filled by what I have just written in recent years, 1838 and 1839. Paris: Note, 1839) I will still continue to write about the current events in my life; I will document these events by means of the letters I happen to write on the road or during my various halts; I will tie in intervening facts by means of a journal which will fill in the missing time between the dates of these letters.

Book XXXIV: Chapter 6: Letters and verses to Madame Récamier

BkXXXIV:Chap6:Sec1

To Madame Récamier

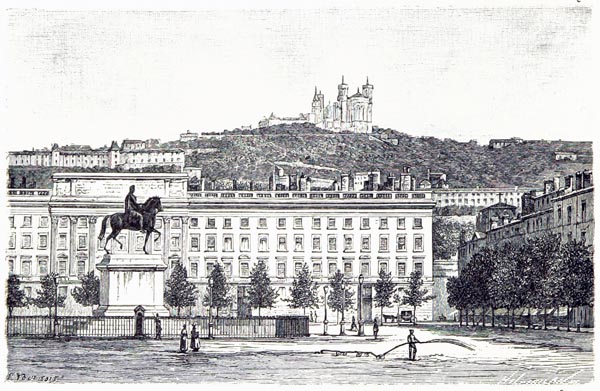

‘Lyons, Wednesday the 18th of May 1831.

Here I am, too far from you. I have never made so sad a journey: admirable weather, nature all adorned, nightingales singing, a starry night: and all for what? I should return to where you are, unless you can come to my aid.’

‘Lyons, Friday the 20th of May.

I spent yesterday wandering along the banks of the Rhône; I gazed at the city where you were born, the hill where the convent rises in which you were chosen as the most beautiful: a prediction which you have not disappointed; and you are not here, and years have rolled by, and you have long been exiled from your cradle, and Madame de Staël is no more, and I am leaving France! Only one person of former times has contacted me: I am sending you his note because it was an unexpected surprise. This person, whom I have never met, plants pines on the hills of the Lyonnais. It is a far cry from there to the Rue Feydeau and ‘A House for Sale’: how roles alter on this earth!

‘Lyon - Place Bellecour et Colline de Fourvières’

La France Pittoresque. Ouvrage Illustré - Jules Gourdault (p414, 1893)

The British Library

Hyacinthe has sent me letters of regret and newspaper articles: I place no value on all that. You know I believe that, sincerely, twenty-three hours out of the twenty-four; the twenty-fourth is consecrated to vanity, but it scarcely takes root, and soon passes. I have seen no one here; Monsieur Thiers, who is travelling in the south, knocked on my door.’

Note included with this letter.

‘A neighbour, your compatriot, who has no other claim on you than a profound admiration for your fine talent and your admirable character, would appreciate the honour of meeting you and presenting his respectful homage. This neighbour in your hotel, this compatriot, is named Elleviou.’

‘Lyons, Sunday the 22nd of May.

We leave tomorrow for Geneva where I will find so many remembrances of you. Will I ever see France again once I have crossed the frontier? Yes, if you desire it: that is to say, if you are still there. I do not wish for events which would offer me a chance to return; I would never include misfortune for my country as one of my hopes. I will write to you on Tuesday the 24th from Geneva. When will I see your delicate handwriting again younger sister of mine?’

‘Geneva, Tuesday the 24th of May.

Having arrived here yesterday, we are looking for a house. It is probable that we will take a little detached residence down by the lake. I cannot tell you how sad I am making these arrangements. Yet another future! Beginning again a life I thought was over! I count on writing you a long letter when I have a little peace; I fear that peace, since then I shall gaze without distractions at those shadowy years which I am entering with a heavy heart.’

‘9th of June 1831.

You know there is a reformed sect which has been established among the Protestants. One of the new pastors of this new Church came to see me and has written me two letters worthy of the original apostles. He wants to convert me to his faith, and I want to make a papist of him. We joust as in Calvin’s day, while loving each other in Christian brotherhood, and without burning each other. I do not despair of saving him; he is quite weakened by my arguments in favour of the Popes. You cannot imagine the heights of exaltation he achieves, and his frankness is admirable. If you arrive, accompanied by my old friend Ballanche, we will do marvels. One of the Geneva newspapers is advertising a controversial Protestant work. The authors have been urged to stand firm because the author of Le Génie du Christianisme is in the neighbourhood.

There is something consoling at finding a little tribe of free people, governed by the most distinguished men and in which religious ideas form the basis of liberty and the first concern of existence.

I have dined with Monsieur de Constant and Madame Necker, unfortunately quite deaf, but a rare woman, of the greatest distinction; we spoke only of you. I have received your letter, and told Monsieur de Sismondi of the kind things you said about him. You see I am learning from you.

Finally, here is some verse. You are my star therein, and I am waiting for you so that I can leave for that enchanted isle.

Delphine is married: O Muses! I told you in my last letter why I could not write about the Peerage or the war; I would be attacking an ignoble corps of which I was part, and I would be preaching honour to those who no longer possess any.

You need to be a sailor to read these lines and understand them. I recommend them to Monsieur Lenormant. Your intellect will enjoy the last three verses, and the explanation of the riddle is in the dedication at the end.’

The Shipwreck

Repulsed by the north wind, aground on the sands,

Shattered old vessel that will ride the waves no more,

One the cruel carpenter, pitiless Death, demands

Be cut to pieces on the shore!

On your deserted deck’s a sentinel’s lonely form:

On your fo’c’s’le, in the past, you’ve seen him,

Impatient for the reefs, for sudden storms,

And whistling aloud to rouse the wind.

Then on your bowsprit, a daring cavalier,

He laughed, as plunging through the breakers

You leapt: and then from the masthead there,

He called: ‘Land ahoy’ to the sailors!

Now, holed-up in your worn out hull, alas,

Sunburnt, white-haired, tarred hands, eyes blue-green,

The broken compass, the almost empty hourglass,

Proclaim the hermit of the seas.

You thought to end moored beside the shore

Old vessel, old Captain! Both were wrong:

The hurricane seized you, set you drifting far,

Howling, dark and azure waves among.

The first reef will set a bound to your course,

And halt you; suddenly your sides half-breached;

You sink! And all is over! Your anchor, flawed,

Slides, ploughing vainly through the deep.

That vessel is my life, the Captain, it is I:

I am rescued! And my days at sea are done:

A star I love has revealed to me its light,

Now, when other stars are gone.

That evening fire, that dissolves the storm,

And bears, so brightly, the name of beauty,

Carries my wreckage over deeps now calm,

To some enchanted island’s mystery.

To my final harbour, sweet and gentle Star,

Your rays I’ll follow, ever fresh and pure;

And when you cease to light my sails, afar,

You’ll shine on my tomb evermore.

To Madame Récamier

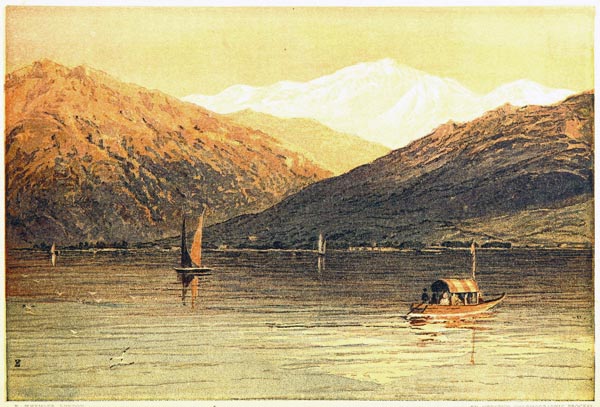

‘Geneva, the 18th of June 1831.

You have received all my letters. I wait constantly for some word from you; I know quite well that I will find nothing, but I am always surprised when the post only brings me newspapers. No one writes to me but you; no one remembers me but you, and that is very charming. I love your solitary letters which do not arrive as they did in the times of my greatness, in the midst of packets of despatches and all the letters of support, admiration and fawning which vanish with fortune. After your little letters I will see your lovely self if I do not go to meet it. You will be my testamentary executor; you will sell my humble retreat; the proceeds will allow you to travel to find the sun. At the moment it is admirable weather: while writing to you, I can see Mont Blanc in its splendour; from the summit of Mont Blanc one can see the Apennines: it seems to me that I am only three paces from Rome where we shall go, since everything in France will be arranged.

‘Mont Blanc From Above Morges’

Swiss Pictures Drawn with Pen and Pencil - Edward Whymper (p198, 1871)

The British Library

It only needed our glorious country, having passed through all her miseries, to be governed by cowards; she is: and the young have been swallowed up by doctrine, literature, or debauchery, according to their individual characters. The course of events remains; but when one drags oneself along the road of life as I have done, the most probable event is the end of the journey.

I do not work, I can do nothing: I am bored; it is my nature, and I am like a fish in water: yet if the water was a little less deep, I would perhaps please myself more.’

Book XXXIV: Chapter 7: My journal for 12th July to 1st September 1831 – Monsieur de Lapanouze’s clerks – Lord Byron – Ferney and Voltaire

At Pâquis, near Geneva.

BkXXXIV:Chap7:Sec1

I have taken up residence in Pâquis with Madame de Chateaubriand; I have made the acquaintance of Monsieur Rigaud, the leading syndic of Geneva: above his house, on the edge of the lake, while climbing the road to Lausanne, you find a villa, belonging to two clerks of Monsieur de Lapanouze’s, who spent 1,500,000 francs having it built and the gardens planted out. When I passed their house on foot, I admired that Providence which had set us all down in Geneva as witnesses to the Restoration. What a fool I am! What a fool! The Lord of Lapanouze espoused royalism and misfortune as I did: see what has happened to his clerks for having supported the alteration in interest rates which I had the wisdom to combat, and in virtue of which I was hunted down. Regard these gentlemen; they arrive in an elegant Tilbury, hat over their ears, and I am obliged to fling myself into a ditch to avoid the wheel carrying away a section of my old frock-coat. Yet I have been a Peer of France, a Minister, and an Ambassador, and I have, in a cardboard box, all the premier orders of Christianity, including the Holy Spirit and the Golden Fleece. If Lord César de Lapanouze’s clerks, millionaires, would like to buy my box of ribbons for their wives it would be a real pleasure to me.

Yet all is not roses for the Messieurs Bartholoni: they are not yet noblemen of Geneva, that is to say they are not of the second generation, and their mother still lives at the lower end of the city and has not climbed to the Saint-Pierre Quarter, Geneva’s Faubourg Saint-Germain; but, God willing, nobility will follow wealth.

I visited Geneva for the first time in 1805, if two thousand years had passed between the dates of my two visits, could they seem further apart than they do? Geneva belonged to France; Bonaparte shone in all his glory, Madame de Staël in all hers; there was no more concern with the Bourbons than if they had never existed. And Bonaparte, Madame de Staël and the Bourbons, where are they? And I, I am still here!

Monsieur de Constant, a cousin of Benjamin Constant, and Mademoiselle de Constant, his elderly daughter, full of wit, virtue and talent, live in their cottage Souterre on the banks of the Rhône: they are overlooked by another country house once belonging to Monsieur de Constant: he sold it to the Princess Belgiojoso, an exile from Milan whom I saw pass like a pale flower amidst the dinner-party I gave in Rome for Grand Duchess Hélène.

During one of my trips on the water, an old boatman told me something that Lord Byron once did, he whose house is visible on the Savoy side of the lake. The noble peer waited for a storm to rise before setting out; from the edge of his bench he dived into the waves, and swam through the tempest to Bonivard’s feudal prison: he was ever a man of action as well as a poet. I am not so original; I also love storms; but my involvements with them are private, and I have no confidence in boatmen.

Behind Ferney, I discovered a narrow valley where a stream of water flows, seven or eight fingers deep; this brook bathes the roots of several willows, conceals itself here and there beneath patches of watercress and makes the bulrushes quiver on whose tops perch damsel flies with blue wings. Did that man who lived to the sound of trumpets ever know this silent refuge opposite his echoing house? I doubt it. Well, the water is there! It still flows; I do not know its name; perhaps it has none: Voltaire’s times are gone; only his fame still makes a little noise in a little corner of our little earth, like this rivulet which makes its self heard only a dozen or so feet from its edge.

People differ: I am charmed by that hidden channel; in sight of the Alps, a fern frond I have picked delights me; a whispering among the reeds makes me happy; a tiny insect which only I will see, which dives into some moss, as if into a vast solitude, draws my gaze and sets me dreaming. Private troubles exist there, which were unknown to that great genius who, not far from here, dressed like Orosmane, acted out his tragedies, wrote to the Princes of this world and forced Europe to come and admire him in the hamlet of Ferney. But were there not troubles there too? The transitions of the world are no more than the passage of these wavelets, and as for kings, I prefer my tiny ant.

One thing always astonishes me when I think of Voltaire: with a superior, clear and rational mind, he remained completely unmoved by Christianity; he never saw what others see: that the establishment of the Gospel, human relations alone considered, was the greatest revolution that could have taken place on earth. It is true to say that in Voltaire’s century that thought never entered anyone’s head. The theologians defended Christianity as an accomplished fact, as a truth founded in laws emanating from the spiritual and temporal authorities; the philosophers attacked it as an abuse perpetrated by priests and kings: no one progressed any further. I do not doubt that if one could have presented Voltaire suddenly with the other side of the question, his quick and lucid intelligence would have been struck by it: one blushes at the thin and narrow-minded manner in which he treated a subject that embraced nothing less than the transformation of nations, the introduction of a morality, a new social principle, a further human right, another order of ideas, a total change in the human race. Unfortunately the great writer who was lost in spreading his fatal ideas dragged many less powerful minds down with him: he resembles those ancient Oriental despots on whose tomb slaves were immolated.

How many famous people rushed to Ferney, where no one goes any more, to that Ferney around which I have just roamed in solitude! They rest, gathered together forever in the recesses of Voltaire’s letters, their temple underground; the sighs of one century diminish by degrees and die away into the eternal silence just as the breathing of another begins to make itself heard.

‘Château de Voltaire à Ferney’

Histoire des Théâtres de Société - Léo Claretie (p98, 1906)

Internet Archive Book Images

Book XXXIV: Chapter 8: My journal continued – Vain endeavours in Paris

At Pâquis, near Geneva.

BkXXXIV:Chap8:Sec1

Oh money, that I have scorned so greatly and cannot love as I should, I am forced to confess that you yet have some merit: source of freedom, you provide a thousand things in our existence, where everything is difficult without you! Except glory, what can you not procure? With you everything is beautiful, young, adored: we have esteem, honours, qualities, and virtues. You will tell me that with money we only have the semblance of all that: what does it matter if I think true what is false? Deceive me cleverly and I will quit you of the rest: is life anything other than a lie? When one has no money, one is dependant on everything and everybody. Two creatures who do not suit each other might go their own ways; well, lacking funds, they must sit there face to face sulking, muttering, in a sour mood, chewing their tongues with boredom, consuming their souls to the whites of their eyes, enraged, making a mutual sacrifice of their tastes, their desires, their in-born way of life: misery grips them both, and in these beggars’ bonds, instead of embracing each other they bite each other, but not as Flora bit Pompey. Without money, there is no means of flight; one cannot go to find another dawn, and possessing a proud spirit, one bears everlasting chains. Happy you financiers, sellers of crucifixes, who govern Christendom today, who decide on peace or war, who eat like pigs on the proceeds of old clothes, who are the favourites of kings and beauties, foul and ugly as you are! Ah, if you could change places with me! If I could rummage a moment in your safes, take from you what you have stolen from the sons of the nobility, I would be the happiest of men!

I ought to have a fine means of subsistence: I could address myself to the monarchs; as I have lost everything on behalf of their crown, it would only be right for them to support me. But that idea which should strike them never does strike them; and strikes me even less. Rather than sitting at royal banquets, I would do better to take up that diet again which I followed in London with my poor friend Hingant. But the happy days of living in garrets are past, not that I would not be there again, but I would be ill at ease there, I would take up too much space with the trappings of my fame; I would no longer be there in my single shirt, with the slender waist of an unknown who has not dined. My cousin de La Bouëtardais is no longer there to play his violin on my pallet-bed in the red robe of a Councillor of the Breton Parliament, and keep warm at night clothed in a chair instead of a counterpane; Peltier is no longer there to give us dinner with King Christophe’s money, and above all the magician is no longer there, Youth, who with a smile changes poverty into wealth, who brings you her younger sister Hope for a mistress; the latter as deceptive as her elder sister, but returning still when the former has fled forever.

I was forgetting the miseries of my first emigration and I imagined that it would be enough to quit France to maintain in peace the honour of exile: roasted skylarks only fall to those who harvest the fields not those who sow them: if it was merely a matter of myself in some alms-house, I would not mind; but Madame de Chateaubriand? So I felt quite uncertain in gazing at the future, anxiety gripped me.

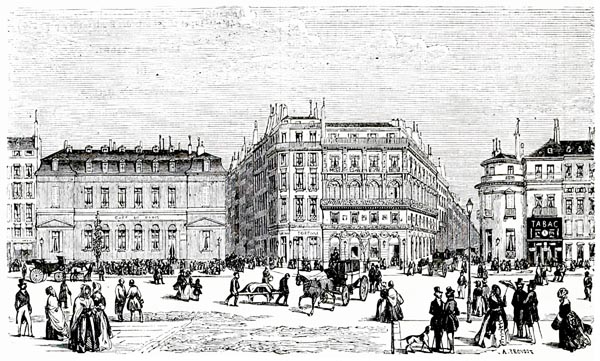

I heard from Paris that my house in the Rue d’Enfer could only be sold at a price which was insufficient to cover the mortgage with which that hermitage was burdened: but something might yet be done if I were there. After this news, I made a useless journey to Paris, since I found neither goodwill nor purchaser; but I saw the Abbaye-aux-Bois again and some of my new friends. On the eve of my return there, I dined at the Café de Paris with Messieurs Arago, Pouqeville, Carrel and Béranger, all more or less discontented and disappointed with the best of republics.

‘Cafe de Paris’

L'illustration: Journal Universel (p109, 1843)

Internet Archive Book Images

Book XXXIV: Chapter 9: My journal continued – Messieurs Carrel and Béranger

At Pâquis, near Geneva, the 26th of September 1831.

BkXXXIV:Chap9:Sec1

My Études Historiques led to a relationship with Monsieur Carrel, as it likewise brought about my meeting Messieur Thiers and Mignet. I had reproduced, in the preface to my Études, a fairly lengthy passage from Monsieur Carrell’s Catalonian War, this paragraph in particular: ‘Events, in their continual and fatal transformations, do not drag all minds along with them; they do not influence every character with equal facility; they do not even take account of all interests; that is what we must understand, and we must forgive something in those protests that are made in support of the past. When an age is over, the mould is broken, and it suffices Providence that it cannot be re-made; but there is sometimes a beauty to be beheld in the ruins left behind on earth.’

After these fine words, I added this summary myself: ‘The man who could write these words has something in sympathy with those who have faith in Providence, who respect past religion, and who have also gazed at ruins.’

Monsieur Carrel thanked me. He was at that time the genius and spirit of the National, on which he laboured with Messieurs Thiers and Mignet. Monsieur Carrel belonged to a pious royalist family of Rouen; the Legitimacy, short-sighted and rarely capable of distinguishing worth, misjudged Monsieur Carrell. Proud and aware of his own value, he took refuge in generous opinions, in which one finds a compensation for the sacrifices one imposes on oneself: what happens to all characters fit for great things, happened to him. When unforeseen circumstances oblige them to restrict themselves to a narrow circle, they consume their super-abundant talents in efforts which surpass the opinions and events of their day. Before revolutions, superior men die unknown: their public has not yet arrived; after revolutions, superior men die abandoned: their public has slipped away.

Monsieur Carrel was unfortunate; nothing was more practical than his ideas, nothing more romantic than his life. A Republican volunteer in Spain in 1823, captured on the battlefield, condemned to death by the French authorities, escaping from a thousand perils, love became enmeshed with the problems of his private existence. It required him to defend the passion which sustained his life, and that man of feeling, always ready to throw himself on the point of a sword in broad daylight, went to find the portal and shadows of night, he walks those silent fields with a beloved woman, at first light, when they beat the reveille to summon an attack on the enemy.

I leave Monsieur Carrel behind to say a few words about our celebrated song-writer. You will find my account is too brief, Reader, but I crave your indulgence: his name and his songs must be engraved in your memory.

Monsieur de Béranger is not obliged to hide his love, as Monsieur Carrell was. Having sung of liberty and the people’s virtues while braving the prisons of kings, he set his love down in a couplet, and, behold, the immortal Lisette.

Near the Barrière des Martyrs, below Montmartre, you will find the Rue de la Tour-d’Auvergne. In that street, half-built, half-paved, in a little house hidden behind a tiny garden and suited to the size of present-day incomes, you will find the famous song-writer. A bald head, a somewhat rustic air, though neat and pleasant, proclaims the poet. I rest my eyes with delight on that plebeian figure, having seen so many visages of kings; I compare those vastly different types: on the royal brow one sees something of an elevated nature, but wrinkled, powerless, worn; on the democratic face common physical traits appear, but one acknowledges a lofty intellectual character: the royal brow has lost its crown; the commoner’s brow awaits one.

One day I begged Béranger (he will forgive me for associating myself with his fame), to show me one of his unknown works: ‘Did you know,’ he said, ‘I began as one of your disciples? I was mad about Le Génie du Christianisme and I wrote Christian idylls; they were scenes with country priests, pictures of religion in villages at harvest-time.’

Monsieur Augustin Thierry told me that the Battle of the Franks in Les Martyrs had given him the idea of a new way of writing history: nothing has flattered me more than to discover the influence of my works on the careers of the historian Thierry and the poet Béranger.

Our song-writer has the varied qualities that Voltaire demanded of song: ‘In order to succeed with these little efforts,’ declared the author of so much graceful poetry, ‘there must be subtlety and sentiment in the soul, harmony in the spirit, nothing too high, or low, and knowledge of how to be brief.’

Béranger has several Muses, all charming, and though those Muses are women, he loves them all. When he is betrayed, he makes no attempt at elegy: and yet there is feeling of pious sadness at the heart of his gaiety: it is a serious face that smiles; it is philosophy praying.

My friendship for Béranger earned me much astonishment on the part of what was called my party; an old Knight of Saint Louis, who is unknown to me, wrote from the recesses of his turret: ‘Rejoice, Monsieur, in being praised by one who has insulted your King and your God.’ Very good, my fine gentleman! You are a poet too.

‘Béranger’

New Physiognomy: or Signs of Character, as Manifested Through Temperament and External Forms, and Especially in the "Human Face Divine." - Samuel Roberts Wells (p553, 1889)

Internet Archive Book Images

Book XXXIV: Chapter 10: A song of Béranger’s: and my reply – A return to Paris for Briqueville’s proposal

BkXXXIV:Chap10:Sec1

During the dinner at the Café de Paris which I have just mentioned to you, Monsieur de Béranger sang me the admirable song published as:

‘Chateaubriand, why then flee your country,

Fleeing her love, our incense and our care?’

This verse about the Bourbons caught people’s attention:

‘And would you free yourself from their fall!

Then know more of their foolish vanity:

Among the ills, they blame even Heaven for,

Their ungrateful hearts place your loyalty.’

I replied from Switzerland to this song which partakes of the history of our times, in a letter which is printed at the start of my pamphlet regarding Briqueville’s proposal. I told the songwriter: ‘From the place where I am writing, Sir, I can see the country house where Lord Byron lived and the roofs of Madame de Staël’s chateau. Where is the bard of Childe Harold? Where is the authoress of Corinne? My over-long life resembles those Roman roads bordered by funeral monuments.’

I returned to Geneva; I then conducted Madame de Chateaubriand to Paris, and brought back the manuscript countering Briqueville’s proposal regarding the banishment of the Bourbons, a proposal considered at the session of the Deputies held on the 17th of September of this year: some link their lives to success, others to misfortune.

Book XXXIV: Chapter 11: Baude and Briqueville’s proposal regarding the banishment of the elder branch of the Bourbons

Paris, Rue d’Enfer, the end of November 1831.

BkXXXIV:Chap11:Sec1

Returning to Paris on the 16th of October, I published my pamphlet towards the end of that same month; it was entitled: On the new proposal regarding the banishment of Charles X and his family, or a sequel to my last work: On the Restoration and the Elective Monarchy.

When these posthumous Memoirs appear, will the daily polemics, the events people are so impassioned about at the present moment, the opponents I am fighting against, even the act banishing Charles X and his family, count for anything at all? That is the trouble with all journals: therein lie animated discussions of topics which have ceased to be of interest; the reader sees a crowd of people pass by like shadows, whose names will not even be remembered: silent extras who fill up the background to the scene. Yet it is in these dry sections of chronicles that you find the observations on, and the facts of, the history of men and mankind.

At the beginning of the pamphlet I placed the decrees, first of all, proposed in succession by Messieurs Baude and Briqueville. Having examined the five courses of action that were to be taken after the July Revolution, I wrote:

‘The worst period we have been through seems that which we are now in, since anarchy reigns in the spheres of reason, morality and intellect. The existence of nations is longer than that of individuals: a paralysed man sometimes lies stretched out on his couch for several years before he vanishes; a sick nation lies in its bed for a long time before expiring. What the new monarchy needs is speed, youth, daring, the turning of one’s back on the past, marching alongside France to a meeting with the future.

Yet it comes offering no cure; it is presented, thin and ill, by the doctors who are treating it. It arrives pitiful and empty-handed, having nothing to give, and everything to receive, displaying its poverty, begging alms of everyone, and yet on the attack, declaiming against the Legitimacy and aping the Legitimacy, against Republicanism and yet trembling before it. This heavily-bandaged system only sees enemies in the twin oppositions it threatens. As supporters it has raised a phalanx of re-employed veterans: if they wore as many stripes on their sleeves as the oaths they have sworn, they would have arms more gaudily coloured than the Montmorency livery.

I doubt whether Freedom will long be pleased with this hotchpotch of a domestic monarchy. The Franks located Freedom, in a camp; she maintained among their descendants their love and desire for that first cradle; like ancient royalty, she wishes to be lifted high on a shield, and her deputies are soldiers.’

‘The Scene in the Throne Room’

The French Revolution of 1848; its Causes, Actors, Events and Influences - George G. Foster (p123, 1848)

The British Library

From that argument I pass to the details of the policy followed in our external relations. The immense mistake of the Congress of Vienna was to have placed a military country like France in a state of enforced hostility with the nations of the Rhine. I show all that the foreigners acquired in territory and power, all that we might have taken back in July. A fine lesson! A striking proof of the vanity of military glory and the works of conquerors! If one made a list of the Princes who have added to French possessions, Bonaparte would not figure there; Charles X would occupy a remarkable place!

Passing from item to item, I arrive at Louis-Philippe: ‘Louis-Philippe is King,’ I write, ‘he bears the sceptre for a child whose immediate heir he is, for that pupil whom Charles X has placed in the hands of the Lieutenant-General of the Kingdom, as in those of an experienced tutor, a loyal guardian, a generous protector. In that Château of the Tuileries, instead of an innocent couch, free of insomnia, rid of remorse, devoid of ghosts, what has the Prince found? An empty throne which reveals to him a headless spectre carrying another spectre’s head in its blood-stained hand.

Must he end by setting up Louvel’s blade in law, before striking a final blow at the proscribed family? If it is driven to these shores by a tempest; if, being too young as yet, Henri is not old enough for the scaffold, well, you are the masters, grant him an exemption to that age-limit on the death-penalty.’

Having spoken about the government of France, I returned to Holyrood and added: ‘May I take, respectfully, in finishing, the liberty of addressing a few words to the exiles? They have re-entered grief as if it were their mother’s womb: misfortune, a seduction I have barely been able to protect myself from, always seems to me to be in the right; I am afraid to bless its sacred authority, and the majesty which adds to their insulted grandeur which will now have only me to flatter it. But I will overcome my weakness; I will force myself to speak a language which, in days of misfortune, may prepare the way for my country’s hopes.

A Prince’s education should be suited to the form of government and the way of life of his country. Now, in France there is no longer any chivalry, no knights, no soldiers of the Oriflamme, no gentlemen cased in steel, ready to march behind the white banner. There is a nation which is no longer the nation of former times, a nation which, altering through the centuries, no longer possesses the old habits and antique way of life of its forefathers. Whether one deplores, or glories in, those social transformations, one must accept the nation as it is, events as they are, and enter into the spirit of the age, in order to affect that spirit.

All is in God’s hand, except the past which, once fallen from that potent hand, never returns to it.

The moment will certainly arrive when that orphan will leave the castle of the Stuarts, a sanctuary of ill omen, which seems to cast its fatal shadow over his youth: the last born descendant of the Béarnais must mix with the children of his own century, attend public schools, and understand everything which is now known. Let him become the most enlightened young man of his times; let him grasp the science of his era; let him join to the virtues of a Christian of the age of Saint-Louis the enlightenment of a Christian of our age. Let travel teach him about law and morality; let him traverse the oceans, comparing institutions and governments, free nations and nations enslaved; let him, if the occasion arises abroad, be a plain soldier exposing himself to the perils of war, since one is not suited to rule the French unless one has heard bullets flying. Then we will have done for him what humanly speaking can be done for him. But above all avoid nourishing in him the idea of divine right; far from encouraging him to mount to the level of his ancestors, prepare him never to ascend to it; raise him to be a man, not a king: that is the best path.

Enough; whatever God’s counsel may be, the recipient of my tender and pious loyalty, possesses the majesty of centuries that men cannot take from him. A thousand years placed on his young head adorn him always with pomp above all monarchs. If in private life he wears that coronet of years, memories and glory, if his hand lifts effortlessly that spectre of the centuries that produced his ancestors what empire has he need to regret?’

Monsieur le Comte de Briqueville, whom I contested the proposal with in this way, had printed various reflections on my pamphlet; he sent them to me with this note:

‘Sir,

I have yielded to the need, to the duty, of publishing the reflections which your eloquent pages on my proposal roused in my mind. I obey a sentiment no less real in deploring my finding myself in opposition to you, Sir, you who, to the power of genius, add so many titles to public consideration. The country is in danger, and I cannot therefore believe there is any longer serious disagreement between us: France invites us to unite to save her; aid her with your genius; our manoeuvres will aid her with our weapons. On that field, Sir, is it not true that we will soon achieve an understanding? You will be the Tyrtaeus of a nation whose soldiers we are, and it will be a joy to me to proclaim myself then the most ardent of your political supporters, as I am already the sincerest.

Your very humble and obedient servant,

Le Comte Armand de BRIQUEVILLE.

Paris, 15th of November 1831.’

I did not remain in my tent, and broke a second lance courtoise against the champion.

‘Paris, this 15th of November 1831.

Sir,

Your letter is worthy of a gentleman: forgive me this ancient word befitting your name, your courage and your love of France. Like you I detest a foreign yoke: if it is a question of defending my country, I will not ask to carry a poet’s lyre, rather a veteran’s sword in the ranks of your soldiers.

I have not yet read your reflections, Sir; but if the political situation leads you to withdraw your proposition which has greatly disturbed me, with what joy I would meet you, without reservation, on the field of freedom, of honour and of the glory of our country!

I have the honour to be, Sir, with the most distinguished consideration, your very humble and obedient servant,

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

Book XXXIV: Chapter 12: A letter to the author of Nemesis

Paris, Rue d’Enfer, The Infirmary of Marie-Thérèse December 1831.

BkXXXIV:Chap12:Sec1

A poet, mingling the censures of the Muse with those of the laws, in a vigorous improvisation, attacked the widow and the orphan. As the verses were those of a writer of talent they acquired a kind of authority which did not allow me to let them pass: I turned to face another enemy. (Monsieur Barthélemy has since adopted the centre-ground, not perhaps without imprecations from many people who rallied around, only a little too late. Note: Paris, 1837)

You cannot understand my reply without reading the poet’s libel; I invite you to cast your eyes over those lines; they are very fine and they are found everywhere. My reply has not previously been published: it appears for the first time in these Memoirs. Wretched wrangling that follows revolutions! See what disputes we arrive at, we feeble successors to those men who, weapons in hand, dealt with the great questions of glory and freedom, while rousing the universe! Now Pygmies make their puny cries heard among the tombs of giants who are buried beneath the mountains they overturned upon themselves.

‘Paris, Wednesday evening, the 9th of November 1831.

Sir,

I have received this morning the recent edition of Nemesis which you have done me the honour of sending to me. In order to avoid being seduced by those praises delivered with such splendour, grace and charm, I need to recall the barriers which exist between us. We live in separate worlds: our hopes and fears are not the same; you do not respect what I adore, and I do not respect what you adore. You have grown up, Sir, amidst the host of July abortions; but just as the influence you imagine my prose to have will not, according to you, revive a fallen race; likewise, according to me, all the power of your poetry will not diminish that noble race: are we not thus both faced with an impossible situation?

You are young, Sir, like that future you dream of and which deceives you; I am old like those times I dream of and which slip away from me. If you came to sit by my hearth, you say obligingly, you would reproduce my features with your burin: I would try hard to make you a Christian and a Royalist. Since your lyre, at the first chord from its strings, sings my Martyrs and my pilgrimage, why not complete the journey? Enter the holy place; time has only stolen some of my hair, as it strips a tree in winter, but there is still sap at the heart: I still have a firm enough hand to grasp the torch which might guide your steps beneath the arches of the sanctuary.

You claim, Sir, that a nation of poets is needed to understand my self-contradictions regarding extinct kingdoms and young republics: do you not also seek to celebrate liberty and yet find magnificent words for the tyrants who oppress it? You cite the Du Barrys, the Montespans, the Fontanges, the La Vallières; you recall royal weaknesses; but did those weaknesses cost France what the debauches of Danton and Camille Desmoulins cost her? The morals of those plebeian Catalines are reflected even in their language, they derived their metaphors from a pigsty of vileness and prostitution. Did the frailties of Louis XIV and Louis XV send fathers and husbands to the gibbet after dishonouring their wives and daughters? Do baths of blood render the impudence of a revolutionary chaste, any more than baths of milk rendered virginal sullied Poppea? When Robespierre’s second-hand dealers sought to sell the people of Paris the blood from Danton’s tubs, as Nero’s slaves sold the milk from his courtesan’s warm baths, do you think there was some kind of virtue in the hand-rinsing of the Terror’s obscene executioners?

The speed and elevation of flight of your Muse has deceived you, Sir: the sun who smiles on all misfortune will have struck a widow’s weeds, and they will have seemed gilded to you: I have seen those weeds, they are mourning clothes; they know nothing of festivals; the child, in the womb that carried it, was lulled to the sound of tears alone; if he had danced for nine months in his mother’s womb, as you write, he would only have felt joy before being born, between conception and childbirth, between the assassination and the proscription! The pallor of dreadful augury that you remarked on Henri’s face is the result of a paternal blood-letting and not the weariness from some ball lasting two hundred and seventy nights. The ancient curse has been realised for that daughter of Henri IV: in dolore paries filios: in sorrow shalt thou bring forth children. I see only the Goddess of Reason whose childbirths, quickened by adulterers, took up their places in the dance of death. From her exposed thighs foul reptiles emerged that danced, instantly, with the women knitting round the scaffold, to the sound of the blade, ascending and descending over and over, to the refrain of a devil’s jig.

Ah, my dear Sir, I beg you, in the name of your rare talent, cease rewarding crime and punishing the unfortunate with sentences improvised by your Muse; do not consign the former to Heaven the latter to Hell. If while remaining attached to the cause of freedom and enlightenment you gave sanctuary to religion, humanity, and innocence, you would see in your vigils another kind of Nemesis appear, worthy of all earth’s homage. Expecting you to pour all the ocean of your fresh ideas over virtue more effectively than I, continue, with the fury you have done, to expose our turpitudes to public contempt; overthrow the false monuments of a revolution which has built no temple appropriate to its religion; plough over their ruins with the blade of your satire; sow salt in that field to render it sterile, so that no more vileness can grow there. I recommend to you, Sir, above all, that crawling government that quivers with pride in submission, victory in defeat, and glories in our country’s humiliation.

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

Book XXXIV: Chapter 13: The conspiracy of the Rue des Prouvaires

Paris, Rue d’Enfer, the end of March.

BkXXXIV:Chap13:Sec1

The year 1831 ended for me in these travels and contests: as 1832 began there was further trouble.

The July Revolution had left the streets of Paris filled with a crowd of Swiss, with Bodyguards, with men of all stations dependent on the Court, now dying of hunger, whom fine monarchical minds, young and foolish beneath their grey hairs, thought to recruit to aid them.

In this tremendous plot, there was no lack of grave, pallid, thin, transparent, bowed personages, their faces noble, their eyes still flashing, and their hair white; this past world seemed like Honour revived in order to attempt to re-establish, with shadowy hands, a family it could not protect with its living ones. Often men with crutches try to prop up falling monarchies; but in this era of society, the restoration of a monument from the Middle Ages is impossible, because the spirit that animated that architecture is dead: one merely imitates the old while thinking to create the Gothic.

On the other side, the heroes of July, whom the happy-medium had robbed of a Republic, asked nothing better than to enter into an accord with the Carlists to take vengeance on a common enemy, even if it meant going on murdering after their victory. Monsieur Thiers having advocated the system of 1793 as a work of liberty, victory and genius, young minds were set alight at the flame of a fire of which they saw only a distant reflection; they were filled with the poetry of the Terror: a terrible and foolish parody which turns back the clock of freedom. It misjudges at the same time the age, history and humanity; it obliges the world to revert to the overseer’s whip in order to save itself from the fanatics of the scaffold.

Money was needed to feed all these malcontents, heroes of July who had been dismissed or servants without places to go to: contributions were collected. Carlist and Republican discussions took place in every corner of Paris, and the police, in touch with everything, sent spies to preach equality and legitimacy from club to garret. I was told of this conduct which I opposed. The two parties wanted to declare me their leader in the moment of certain triumph: a Republican club asked me if I would accept the Presidency of the Republic; I replied: ‘Yes, certainly; but only after Monsieur Lafayette’ which they found modest and fitting. General Lafayette sometimes visited Madame Récamier’s; I poked a little fun at his best of republics: I asked him if he would not have been better to acknowledge Henri V and be the real President of France during the royal child’s minority. He admitted it and took the pleasantry well, being good company. Every time we met, he said: ‘Oh, you are going to quarrel with me again!’ I got him to admit that no one had ever tricked him more than his good friend Philippe.

In the midst of this disturbance and these extravagant conspiracies, a man arrived at my house, in disguise, a couch-grass wig on his occiput, green-glass spectacles on his nose, shading eyes which saw quite well without spectacles. He had pockets full of bills of exchange which he showed around; and immediately on being informed I wished to sell my house and settle my affairs, he offered me his services; I could not help laughing at this gentleman (a man of spirit and resource moreover) who considered himself obliged to buy me for the Legitimacy. His offers became too pressing, he saw on my lips a disdain which forced him to retreat, and he wrote my secretary this little note which I kept:

‘Sir,

Yesterday evening I had the honour to meet Monsieur le Vicomte de Chateaubriand, who received me with his usual kindness; nevertheless I thought I noticed that he lacked his customary openness. Tell me, I beg you, what would re-establish his trust in me which I esteem more than everything; if he has heard any malicious gossip about me, I am not afraid of exposing my conduct to the light of day, and I am ready to reply to anything that may have been said; he knows the mendacity of intriguers too well to condemn me without a hearing. There are cowards who do so too; but one must hope that the day will arrive when the truly devoted people are recognised. He told me that it would be useless for me to become involved in his affairs; I am sorry for it; since I like to think they would have been arranged as he desires. I suspect I probably know the person who has influenced him in the matter; if I had been less discreet at the time, it would not have done me any harm with your excellent patron. Well, I am no less devoted to him, and you may tell him so in presenting my respectful homage. I dare to hope that the day will come when he will know and understand me.

Accept, I beg you, Sir, etc.’

Hyacinthe wrote this reply which I dictated to him:

‘My patron has nothing at all against the person who has written; but he wishes to live in private, and does not wish to accept any assistance.’

Soon after this, trouble occurred.

Do you know the Rue des Prouvaires, a narrow, dirty and busy street near Saint-Eustache and Les Halles? It was there that a famous supper was held during the third Restoration. The guests were armed with pistols, daggers, and iron bars; after the drinks, they were going to enter the Louvre Gallery, and passing between two rows of masterpieces at midnight, strike the usurping monster in the midst of a reception. The conception was romantic; the sixteenth century had returned, and one might have believed it was the age among men of the Borgias, the Medicis of Florence, and the Medicis of Paris.

On the 1st of February, at nine in the evening, I was going to bed, when an extremist, and the individual with the bills of exchange, knocked on my door, in the Rue d’Enfer, to tell me all was ready, that in two hours Louis-Philippe would be no more; they came to discover whether they could declare me leader of the provisional government, and whether I would consent to take the reins, in a Regency Council, of that provisional government, in the name of Henri V. They confessed that the matter was dangerous, but that I could not win more glory, and that, as I suited all parties, I was the only man in France in a position to play the role. I was close pressed: two hours were allowed for me to decide on my coronation! Two hours to sharpen the mighty Mameluke sabre I had bought in Cairo in 1806! Yet I found no difficulty in saying to them: ‘Gentlemen, you know I have never approved of this enterprise, which seems foolish to me. If I had chosen to be involved, I would have shared the risk, not waited for your victory in order to accept the reward for the danger you run. You know I love liberty deeply, and it is obvious to me, from the leadership of this whole affair, that they do not want liberty, that they will begin, as masters of the field of battle, to impose arbitrary rule. They would find no one, I especially, to support them in that project; their success would lead to total anarchy, and foreign powers, profiting from our discord, would dismember France. I cannot therefore be involved in all that. I admire your devotion, but mine is not of a like nature. I am going to bed; I advise you to do the same, and I have great fears of learning of your friends’ misfortunes tomorrow.’

‘The Marmaluke’

The Philopoena: or, Friendship's Offering; a Gift for all Seasons (p83, 1854)

Internet Archive Book Images

The supper took place; the host, who had prepared it with official consent, knew what was going on. Informers at the table clinked their glasses loudest, in drinking Henri V’s health; the police sergeants arrived, seized the guests and yet again overthrew the royalist legitimacy’s coup. The Rinaldo of the royalist adventurers was a cobbler from the Rue de Seine, decorated in July, who had fought valiantly during the Three Days, and who grievously wounded one of Louis-Philippe’s police agents, on behalf of Henri V, as he had killed guardsmen to oust that same Henri V and the two elder kings.

During this affair I received a note from Madame la Duchesse de Berry nominating me as a member of a secret government she had established in her name, as Regent of France. I took the opportunity to write the Princess the following letter:

‘Madame,

It is with the deepest gratitude that I received the witness of your confidence and esteem with which you have been so kind as to honour me; it imposes on my loyalty the duty of redoubling my zeal, in laying before your Royal Highness’ eyes the truth as it appears to me.

I will speak first of the so called conspiracy, rumours of which will perhaps have reached Your Royal Highness. It is claimed that it was fabricated or provoked by the police. Leaving that to one side and without insisting on whether the conspiracy (real or imagined) had anything reprehensible about it, I will content myself with remarking that our national character is at the same time too superficial and too open for such things to succeed. For forty years these kinds of criminal enterprise have continually failed. There is nothing extraordinary in hearing a French person boasting publicly that they are part of a plot; they will tell all the details, without forgetting the date, place and hour, to any spy they take for a colleague; they say aloud, or rather shout to the passers-by: “We have forty thousand men all told, we have sixty million cartridges, such and such a street, at this number, in the house at the corner.” And then this Catiline will dance around smiling.

Secret societies alone have wide scope, because they proceed by revolution and not by conspiracy; they aim to change doctrines, ideas and morals before changing men and things; their progress is slow, but the results assured. The publicity given to their thought destroys the influence of secret societies; public opinion now achieves in France what hidden gatherings accomplish among nations that are not yet emancipated.

The regions of the West and South, which they seem to want to push to the limits of endurance, by arbitrary violence, retain that spirit of loyalty which distinguishes past morality; but that section of France will not conspire in the strict sense of the word: it is a kind of armed camp in waiting. Admirable as a reserve for the Legitimacy, it would be insufficient as a vanguard and could never be successful in taking the offensive. Civilisation has made too much progress for civil war to break out with any great result, a recourse and scourge of centuries which is at the same time most Christian and least enlightened.

What exists in France is not a monarchy, it is a republic; in truth, of the worst kind. This republic is protected by royalty, like a breastplate which receives the blows and prevents them striking the government itself.

Moreover, if the Legitimacy is a considerable force, election is also a dominating power, even when it is only a fiction, especially in this country where we see only vanity: the French passion for equality prides itself on elections.

Louis-Philippe’s government indulges in excesses of both arbitrary power and obsequiousness of which Charles X’s government never dreamed. Why is such excess tolerated? Because the people more easily support the tyranny of a government they have created than the legal rigour of institutions which are not their work.

Forty years of trial have broken the firmest hearts; apathy is prevalent, egotism is rife; people shrink inwards to escape danger, to keep what they have, to struggle along in peace. After a revolution there are gangrened casualties who communicate their sickness to all, as after a battle corpses are left to pollute the air. If Henri V could be transported to the Tuileries without trouble, without a tremor, without compromising the least interest, we would be in sight of a Restoration; but if only one sleepless night is needed to achieve it, the chances diminish.

The result of those days of July has produced no benefit to the people, no honour for the army, no advantage to literature, the arts, commerce or industry. The State has become the prey of professional politicians and of that class which sees the country as its cooking pot and public affairs as its kitchen: it is difficult, Madame, for you to understand from afar what is now called the happy-medium; that His Royal Highness presents a figure completely devoid of elevation of soul, nobility of feeling, dignity of character; that he represents people inflated with their own importance, enchanted with their jobs, panicky about money, ready to die for their pensions: nothing will pry them free; it is a matter of life or death to them; they are wedded to it all, as the Gauls were to their weapons, knights to the Oriflamme, Huguenots to Henri IV’s white banner, and Napoleon’s soldiers to the tricolour flag; they will die only of exhaustion from swearing oaths to every regime, after spilling the last drop of their blood in a last battle. These eunuchs of the quasi-legitimacy dogmatize about freedom while assaulting citizens in the streets and throwing writers in gaol; they intone songs of victory while evacuating Belgium on the orders of an English Minister, and soon Ancona on the orders of an Austrian corporal. They slope between the gates of Saint-Pélagie prison and the doors of the Cabinets of Europe, stiff with liberty and encrusted with glory.

What I say regarding the state of France should not discourage Your Royal Highness; but I wish you to gain a better understanding of the path that leads to Henri V’s throne.

You know my thoughts concerning the education of my young king: my sentiments are expressed at the end of the pamphlet which I set at Your Royal Highness’ feet: I can only repeat it. Let Henri V be raised for his century, with and for men of his century; those two phrases sum up my whole policy. Above all, let him not be raised to be king. He may reign tomorrow, he may reign in ten years time, or he may never reign: for though the Legitimacy may have several opportunities to return which I will soon develop further, nevertheless the edifice may actually fall without the Legitimacy emerging from its ruins. You have a strong enough spirit, Madame, to imagine, without allowing yourself to be overcome, a judgement from God which would plunge your illustrious race back into the common stock; just as you have a heart great enough to nourish real hopes without allowing yourself to become intoxicated with them. I should now present you with the other side of the picture.