François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXXIII: A Farewell to Office 1830

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXXIII: Chapter 1: The King leaves Saint-Cloud – Madame la Dauphine arrives at the Trianon – The diplomatic corps

- Book XXXIII: Chapter 2: Rambouillet

- Book XXXIII: Chapter 3: Opening of the Session of the 3rd of August – A letter from Charles X to Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans

- Book XXXIII: Chapter 4: The crowd departs for Rambouillet – The flight of the King - Reflections

- Book XXXIII: Chapter 5: The Palais-Royal – Conversations – A last political temptation – Monsieur de Saint-Aulaire

- Book XXXIII: Chapter 6: The Republican Party’s last gasp

- Book XXXIII: Chapter 7: The 7th of August – A session of the Chamber of Peers – My speech – I leave the Luxembourg Palace never to return – My resignations

- Book XXXIII: Chapter 8: Charles X embarks at Cherbourg

- Book XXXIII: Chapter 9: How the July Revolution will be viewed

- Book XXXIII: Chapter 10: The end of my political career

Book XXXIII: Chapter 1: The King leaves Saint-Cloud – Madame la Dauphine arrives at the Trianon – The diplomatic corps

BkXXXIII:Chap1:Sec1

You have just seen Royalty on the Place de Grève, powdered and breathing hard, marching in the midst of its arrogant supporters; now watch Royalty at Rheims withdrawing at a measured pace in the midst of its chaplains and guards, walking with the correctness prescribed by etiquette, hearing not one disrespectful word, and revered even by those who detest it. The soldier who considered it of little worth, was prepared to die for it; the white banner, draped over his coffin before being folded forever, said to the breeze: Salute me: I was at Ivry; I saw Turenne die; the English knew me at Fontenoy; I fought for freedom’s victory under Washington; I freed Greece, and I still wave above the walls of Algiers!

On the 31st, at daybreak, at the very hour when the Duc d’Orléans, after arriving in Paris, was preparing to accept the Lieutenant-Generalship, the servants from Saint-Cloud presented themselves at the camp near the Pont de Sèvres, declaring that they had been dismissed, and that the King had left at three-thirty in the morning. The soldiers were anxious, but grew calmer on seeing the Dauphin; he appeared on horseback, as if to inspire them with one of those speeches that leads the French to death or victory; he halted in front of the line, stammered a few phrases, turned abruptly and re-entered the Château. It was not courage that failed him, but words. The wretched education that the princes of the elder branch received, since Louis XIV, rendered them incapable of maintaining an argument, expressing themselves like others, or mixing with the rest of mankind.

Meanwhile the heights of Sèvres and the terraces of Bellevue were crowned with representatives of the people: there were several exchanges of fire. The captain who commanded the vanguard at the Pont du Sèvres went over to the enemy: he led a party of soldiers and a piece of cannon to a group gathered on the Point du Jour road. Then the Parisians and the Guards agreed that there would be no hostilities until the evacuation of Saint-Cloud and Sèvres had been achieved. The withdrawal commenced; the Swiss were surrounded by the citizens of Sèvres, and threw down their arms, though they were relieved almost immediately by the Lancers, the Lieutenant-Colonel of whom was wounded. The troops passed through Versailles, where the National Guard had been positioned since the previous day along with La Rochejaquelin’s Grenadiers, the former under the tricolour cockade, the latter under the white. Madame la Dauphine arrived from Vichy and rejoined the Royal Family at Trianon, once Marie-Antoinette’s favourite place. At Trianon, Monsieur de Polignac parted from his master.

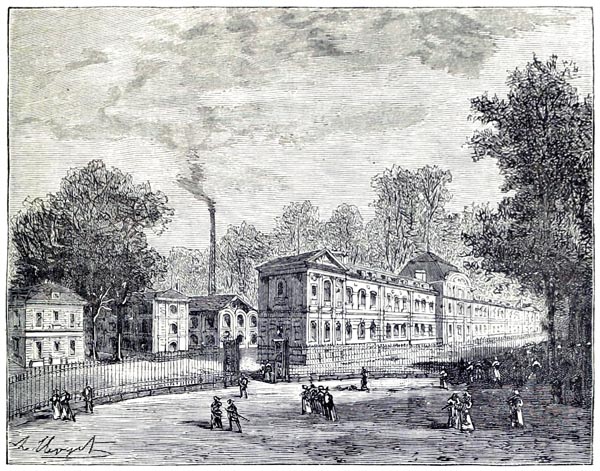

‘Manufacture de Sèvres’

La France Illustrée: Géographie, Histoire, Administration, Statistique - Victor Adolfe Malte-Brun (p652, 1881)

Internet Archive Book Images

It has been said that Madame la Dauphine was opposed to the decrees: the only means of judging such matters is to consider them in their essentials; the people will always be for freedom, princes inclined towards power. It is neither a crime nor a merit in them; it is their nature. Madame la Dauphine would perhaps have desired the decrees to have appeared at a more opportune moment, so that better precautions could have been taken to ensure their success; but in truth they pleased her and ought to have done so. Madame la Duchesse de Berry was delighted by them. Those two Princesses thought that unfettered royalty was at last free of the shackles that representative government attaches to the feet of kings.

It is astonishing that there was no sign of the diplomatic corps during these events of July, they who were consulted far too much by the Court, and were involved in all our affairs. There is twice a reference to foreign ambassadors during the disturbances. A man was arrested at the gates, and the package he was carrying was sent to the Hotel de Ville: it was a despatch from Monsieur de Loevenhielm to the King of Sweden. Monsieur Baude had this despatch returned to the Swedish legation without opening it. Lord Stuart’s correspondence fell into the hands of the popular leaders, it was also returned without being opened, which amazed London. Lord Stuart, like his fellow countrymen, adored disorder abroad: his diplomacy was that of a policeman, his despatches were police reports. He like me when I was Minister, because I dealt with him without any fuss, and because my door was always open; he entered the residence at any hour in his boots, muddy and dressed like a thief, after chasing about the boulevards and through houses of ladies whom he rewarded badly, who called him Stuart.

I had conceived a new way of conducting diplomacy: having nothing to hide, I spoke out loud; I would have shown my despatches to the first-comer, because I had no project for the glory of France that I was not determined to accomplish despite all opposition.

I told Sir Charles Stuart a hundred times, with a smile, yet speaking seriously: ‘Don’t pick a quarrel with me. If you throw down your glove, I shall pick it up. France has never made war on you with a proper understanding of your circumstances; that is why you have beaten us; but don’t rely on it.’ (That is pretty much what I wrote to Mr Canning in 1823. See Le Congrès de Vérone.)

Lord Stuart regarded our July disturbances therefore in a good-natured way while delighting in our misery; but the other members of the diplomatic corps, inimical to the popular cause, had more or less urged Charles X to issue the decrees, and yet, when they appeared, they did nothing to rescue the monarchy; so that if Monsieur Pozzo di Borgo showed anxiety about a Coup d’État it was not on behalf of the king or the people.

Two things are certain:

Firstly, the July Revolution acted against the treaties of the Quadruple Alliance: Bourbon France was party to that alliance: the Bourbons could not be violently dispossessed without placing Europe’s new political rule in danger.

Secondly, in a monarchy, foreign legations are not accredited to the government; but to the monarch. The strict duty of those legations was therefore to gather around Charles X, and follow him wherever he went on French soil.

Is it not strange that the only ambassador who took account of this idea represented Bernadotte, a king who did not belong to an ancient royal family? Monsieur de Loevenheilm converted Baron Werther to his opinion, while Monsieur Pozzo di Borgo opposed a step which would have taxed letters of credit and which demanded they be honoured.

If the diplomatic corps had gone to Saint-Cloud, Charles X’s position would have been different: the partisans of the Legitimacy would firstly have gained the power in the Elective Chamber which they lacked; the fear of possible war had alarmed the industrialists; the idea of keeping the peace while protecting Henri V had brought a considerable mass of people over to the Royal infant’s side.

Monsieur Pozzo do Borgo held back in order not to compromise his funds on the Bourse or with the banks, and especially not to expose his position. He had gambled at five per cent on the death of the Capetian legitimacy, a death which will communicate itself to other living kings. People will be sure, in this age of ours, to attempt, as usual, to pass off this irreparable crime of personal interest as a profound scheme.

Ambassadors who are left at the same Court for too long take on the manners of the country they reside in: charmed to be living in the midst of honours, failing to see things as they are, they fear to let slip in their despatches any reality that might lead to an alteration in their status. It is another thing, in effect, to be Messieurs Apponyi, Werther, and Pozzo in Vienna, Berlin and St Petersburg, than to be their Excellencies the Ambassadors to the Court of France. It is said that Monsieur Pozzo had a grudge against Louis XVIII and Charles X, regarding the blue sash and a peerage. They were wrong not to satisfy his wishes; he had rendered the Bourbons good service, through hatred of Bonaparte his fellow-countryman. But if at Ghent he had decided the issue of the throne by urging the rapid departure of Louis XVIII for Paris, he can pride himself on having contributed, by preventing the diplomatic corps from doing its duty during those July days, to the toppling from Charles X’s head of the crown, which he had helped to place on that of Charles’ brother.

I have thought for a long time that the diplomatic corps born in an age subject to another order of society is no longer in tune with the new order: public government, and swift communication means that nowadays cabinets are able to handle affairs directly or with no other intermediary than the consular agents, whose numbers should be increased and whose lot should be improved: since Europe is now industrialised. Titled spies, with exorbitant pretensions, who interfere in everything in order to acquire an importance they lack, only serve to trouble governments to which they are accredited, and nourish their masters’ illusions. Charles X was wrong, for his part, in not inviting the diplomatic corps to attend his Court; but what he saw resembled a dream to him; he stumbled from astonishment to astonishment. It is thus that he failed to order Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans to join him; since, believing only in dangers from the Republican side, the risk of usurpation never entered his head.

Book XXXIII: Chapter 2: Rambouillet

BkXXXIII:Chap2:Sec1

Charles X left in the evening for Rambouillet with the Princesses and Monsieur le Duc de Bordeaux. Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans’ new role gave birth in the King’s mind to the first thoughts of abdication. Monsieur le Dauphin, always in the rear-guard, but never mixing with the soldiers, had what remained of the food and wine distributed to them at Trianon.

At eight-fifteen in the evening, the various corps began marching. There the loyalty of the 5th Light Infantry expired. Instead of following the route, they returned to Paris: their flag was taken to Charles X who refused to accept it, as he had refused to accept that of the 50th.

The brigades were in confusion, their sections intermingled; the cavalry overtook the infantry and made a separate halt. At midnight, as the 31st expired, they arrived at Trappes. The Dauphin slept in a house behind the village.

On the next day, the 1st of August, he left for Rambouillet leaving the troops bivouacked at Trappes. They struck camp at eleven. Some soldiers, having gone to buy bread in the hamlets, were massacred.

Arriving at Rambouillet, the army was billeted around the Château.

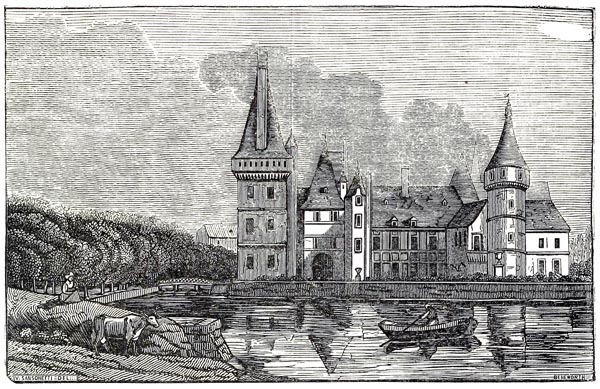

‘Rambouillet’

Hendrik Schwegman, 1771 - 1816

The Rijksmuseum

During the night of the 1st, three regiments of heavy cavalry set out for their former garrisons. They thought that General Bordesoulle, commanding the Guards heavy cavalry, had surrendered at Versailles. The 2nd Grenadiers also left on the morning of the 2nd of August, after sending their pennants to the King. The Dauphin encountered these deserting grenadiers; they formed line in order to render honours to the Prince and then continued on their way. A strange mixture of disloyalty and ritual! In that Three Day revolution no one was passionate; everyone acted according to his own idea of right or duty: the right won, the duty fulfilled, no enmity remained and likewise no affection, some fearing lest rights carry them too far, others lest duty exceed its boundaries. Perhaps there has never been a time, and will never be another, in which a people has halted before achieving victory, and soldiers who have defended a king, as long as he seemed willing to resist, have returned their standards to him before abandoning him.

The decrees had freed the nation of its oath; this retreat, on the field of battle, freed the grenadier of his flag.

Book XXXIII: Chapter 3: Opening of the Session of the 3rd of August – A letter from Charles X to Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans

BkXXXIII:Chap3:Sec1

With Charles X withdrawing, and the Republicans falling back, nothing prevented the elected monarchy from advancing. The provinces, ever like sheep, and the slaves of Paris, at every twitch of the telegraph and every tricolour flag waving from the summit of a carriage, shouted: ‘Long live, Philippe!’ or: ‘Long live, the Revolution!’

For the opening of the Session, fixed for the 3rd of August, the Peers moved to the Chamber of Deputies: I went along, since everything was still provisional. There another act of the melodrama was played out: the throne was empty and the anti-King sat to one side. Someone had mentioned a Chancellor opening a session of the English Parliament by proxy, in the sovereign’s absence.

Philippe spoke of the dire necessity of his accepting the Lieutenant-Generalship to protect us all, of the revision of Article 14 of the Charter, of freedom which he, Philippe, bore in his heart and which he would extend to us, and of peace in Europe. Tricks performed with language, and with the constitution, which had been repeated at each phase of our history for the previous half century. But attention was drawn to this declaration of the Prince:

‘Peers and Deputies, Gentlemen,

As soon as the two Chambers have been constituted, I will bring forward for your attention the Act of Abdication of His Majesty King Charles X. By this same act, Louis-Antoine de France, Dauphin, also renounces his rights. This act was placed in my hands yesterday, the 2nd of August, at eleven o’clock at night. I ordered it to be deposited in the archives of the Chamber of Peers this morning, and have had it inserted in the Moniteur’s official announcements.’

By a miserable ruse, and with cowardly reticence, the Duc d’Orléans here suppressed the name of Henri V, in whose favour the two kings had abdicated. If every citizen of France has been individually consulted at that time, it is probable that the majority would have pronounced in favour of Henri V; some republicans would even have accepted him, while appointing Lafayette as his mentor. The seed of the Legitimacy remaining in France, and the two old kings departing to end their days in Rome, any difficulties surrounding the usurpation, and rendering it suspect to various elements, would have ceased to exist. The adoption of the junior Bourbon line was not only a risk, it was a political nonsense; modern France is Republican; it does not want a king, at least not a king of the ancient race. Let a few years go by, and we shall see what becomes of our freedoms and what that peace constitutes in which the world is to rejoice. If one judges from the newly elected leader’s conduct, given what one knows of his character, it is likely that this Prince will see the way to preserve his monarchy only by oppression at home, and fawning abroad. (Was I wrong? Note: Paris, 1840)

Louis-Philippe’s real crime was not in accepting the crown (an act of ambition of which there are thousand of examples, and which merely attacked the political institutions); his true offence was in being a faithless master, in despoiling the infant and the orphan, an offence against which the Scripture cannot rail enough: now, moral justice (which is called fatality or Providence, and which I call the inevitable consequence of evil) never fails to punish infractions of the moral law.

‘Louis Phillip I, King of the French’

Full Annals of the Revolution in France, 1830 - William Hone (p8, 1830)

The British Library

Philippe, his government, all that realm of impossible and contradictory things, perished, in a timescale more or less retarded by chance events, by internal and external complexities of interest, by the apathy and corruption of individuals, and by the superficiality, indifference and evasion of men of influence; but, whatever the actual duration of the regime, it will not be long enough for the Orléans branch to become deep-rooted.

Charles X, learning of the progress of the revolution, possessing nothing in his own character or experience capable of arresting that progress, thought to ward off the blow executed against his line by abdicating with his son, as Philippe announced to the Deputies. On the 1st of August he had written a note approving the opening of the session, and counting on his cousin the Duc d’Orléans’ sincere affection for him, he named him, for his part, Lieutenant-General of the Kingdom. He went further on the 2nd, asking no more than to embark on board ship, and asking for commissioners to escort him as far as Cherbourg. This suggestion was not well received initially by the military. Bonaparte had also had commissioners as guards, on the first occasion Russians, on the second Frenchmen; but he had not asked for them.

Here is Charles X’s letter:

‘Rambouillet, this 2nd of August 1830.

Dear cousin, I am far too deeply grieved by the ills which afflict or might threaten my nation not to seek means of preventing them. I have therefore resolved to abdicate the crown in favour of my grandson the Duc de Bordeaux.

The Dauphin, who shares my sentiments, also renounces his rights in favour of his nephew.

You will then, in your role as Lieutenant-General of the Kingdom, proclaim the advent of Henri V to the crown. Moreover you will take all measures within your remit to organise the government during the new king’s minority. Here I limit myself to making these dispositions known; as a means of avoiding further ills.

You will communicate my intentions to the diplomatic corps, and let me know at the earliest moment of the proclamation by which my grandson is recognised as King under the name of Henri V.

I renew to you, dear cousin, my assurance of the sentiments with which I remain your affectionate cousin.

CHARLES.’

If Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans had been capable of emotion, or remorse, would not that phrase, your affectionate cousin, have stirred his heart? At Rambouillet they had so little faith in the efficacy of abdication, that they readied the young prince for the voyage: the tricolour cockade, his aegis, had already been prepared by the hands of those who had been most eager for the decrees. Suppose that Madame la Duchesse de Berry, leaving swiftly with her son, had been presented to the Chamber of Deputies at the moment when Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans was delivering the opening speech, then a chance would have remained; a slim chance, but at least, in the event of disaster, the child lost to Heaven would not have dragged out wretched days on a foreign soil!

My advice, my wishes, and my cries, were powerless; in vain I urged Marie-Caroline to act: Bayard’s mother, preparing to leave the paternal castle, ‘wept’ says the Loyal Servant. ‘The good gentlewoman left by the rear entrance to the tower and came to her son to whom she spoke these words: “Pierre, my dear, be gentle and courteous while subduing all pride; be humble and helpful to all people; be faithful in word and deed; aid the poor widow and orphan, and God will protect you.” Then the good lady took from her sleeve a small purse in which there were only six gold crowns and a piece of silver which she gave to her son.’

The Chevalier ‘sans peure et sans reproche’ left with his six gold crowns in a little purse to become the bravest and most renowned of knights. Henri, who may have lacked even the six gold crowns, had other struggles to contend with; he had to fight against misfortune, a difficult champion to unhorse. Let us glorify mothers who teach such fine and tender lessons to their sons! Be blessed then, my mother, from whom I derive whatever has brought honour and discipline to my life.

Forgive all these recollections; but perhaps my tyrant memory, by mingling past with present, robs the latter of some of its wretchedness.

The three Commissioners deputed to escort Charles X were Messieurs de Schonen, Odilon Barrot, and Marshal Maison. Recalled by military summons, they took the road the Paris. A popular procession carried them towards Rambouillet.

Book XXXIII: Chapter 4: The crowd departs for Rambouillet – The flight of the King - Reflections

BkXXXIII:Chap4:Sec1

On the evening of the 2nd of August, in Paris, a rumour spread that Charles X refused to leave Rambouillet until his grandson had been recognised as king. A crowd assembled on the morning of the 3rd on the Champs-Élysées, shouting: ‘To Rambouillet! To Rambouillet! No Bourbon must survive.’ Wealthy men mingled among them, but come the moment they watched the rabble depart, with General Pajol, who had Colonel Jacqueminot as his chief-of-staff, at its head. The Commissioners on returning, had encountered the Colonel’s scouts, retraced their steps and were then escorted to Rambouillet. The King then questioned them about the forces of insurgency, before he withdrew and summoned Maison, who owed him his fortune and his Marshal’s baton: ‘Maison, I ask you to tell me on your honour, and on your military oath, whether what the Commissioners are saying is true or no?’ The Marshal replied: ‘You have not been told the half of it.’

At Rambouillet, on the 3rd of August, were three thousand five hundred men of the Foot Guards, and four regiments of Light Cavalry, in twenty squadrons, comprising two thousand men. The military headquarters, corps of Guards, etc, cavalry and infantry, amounted to thirteen hundred men; in total six thousand eight hundred men, and seven mounted batteries composed of forty-two pieces of cannon. At ten in the evening they sounded the signal to mount; the whole camp set out on the road to Maintenon, Charles X and his family travelling in the centre of the fatal procession dimly lit by the veiled moon.

‘Etat Actuel du Château de Maintenon’

Magasin Universel: Publié sous la Direction de Savants, de Littérateurs et d'Artistes - Antonio Cavagna Sangiuliani di Gualdana, Conte (p240, 1833)

Internet Archive Book Images

Whom did they retreat before: before a virtually unarmed crowd which arrived from Versailles and Saint-Cloud in omnibuses, four-wheeled cabs, and little carriages. General Pajol had thought himself doomed when he was forced to take command of this host, which, after all, comprised no more than fifteen thousand individuals, including those arriving from Rouen. Half of the mob was left behind on the way. A few excited, brave and generous young men, in this confused crowd, would have been killed; the rest would probably have dispersed. In the fields of Rambouillet, in open country, they would have had to face infantry and artillery fire; a victory, according to all the evidence, would have been achieved. Negotiations could have been established between the people, victorious in Paris, and the King, victorious at Rambouillet.

What! Amongst all those officers, was there not one resolute enough to seize command in the name of Henri V? For, after all, neither Charles X nor the Dauphin was now king!

If they did not wish to fight, why did they not retreat to Chartres? There they would have been well out of reach of the Paris mob: better still to Tours, relying on the Legitimist provinces. With Charles X still in France, the majority of the army would have remained loyal. The camps at Boulogne and Lunéville would have risen and marched to his aid. My nephew, Comte Louis, was in command of a regiment, the 4th Chasseurs, which had not disbanded on news of the retreat from Rambouillet. Monsieur de Chateaubriand was reduced to escorting the monarch on a pony to his place of embarkation. If, from one of those towns, maintaining the initiative, Charles X had convoked the two Chambers, more than half of each Chamber would have obeyed. Casimir Périer, General Sébastiani and a hundred others would have attended, being opposed to the tricolour cockade; they dreaded the dangers of a popular revolution: what am I saying? The Lieutenant General of the Kingdom, summoned by the King, and not realising the battle was won, would have been stripped of his followers and would have obeyed the Royal command. The diplomatic corps, which failed in its duty, would then have carried it out by rallying to the monarch. The Republic, instituted in Paris in the midst of total disorder, would not have lasted a month, faced by a proper constitutional government, established elsewhere. Never was a game lost so easily, and when it is lost in that way, there is no opportunity for revenge: talk then to citizens about freedom and about honour to soldiers, after the July decrees and the retreat from Saint-Cloud!

Perhaps a time will come, when a new social order will have replaced existing society, when war will seem a monstrous absurdity, when principles will no longer be compromised; but we are not there yet. Among armed struggles, there are philanthropists who distinguish different kinds, and are ready to find civil war alone evil: ‘Compatriots who kill each other, brothers, fathers, sons who face one another!’ Without doubt, all that is very sad; yet a nation is often refreshed and reinvigorated by internal discord. No country has vanished through civil war, often they have vanished in wars with other countries. Look at Italy at the time of its divisions, and look at her today. It is deplorable to be forced to ravage your neighbour’s property, to see your hearth blood-drenched by that neighbour; but, frankly, is it any more humane to massacre a family of German peasants whom you do not know, who have never quarrelled with you in any way, whom you rob, whom you kill without remorse, whose wives and daughters you dishonour with an easy conscience, merely because that is war? Whatever they say, civil war is less unjust, less repulsive, and more natural than war abroad, when the latter is not undertaken to save the nation’s independence. At least civil wars are founded on individual grievances, on acknowledged and recognised aversions; they are duels with seconds, or at least the adversaries know why they have a sword in their hand. If the passions do not justify evil, they excuse them, they explain them, and they allow one to understand why it exists. How can one justify a foreign war? Nations are at each other’s throats often because some king is bored, because some ambitious person wishes to rise, because a minister seeks to supplant a rival. It is time to render justice to these old commonplaces of sensibility, more fitting for poets than historians. Thucydides, Caesar, Livy content themselves with a word of mourning then pass on.

Civil war, despite its calamities, has only one real danger: that is if the factions have recourse to a foreign power, or the foreign power, profiting from national division, attacks the nation; conquest may be the result of such a situation. Great Britain, Spain, Ottoman Greece, in our time, and Poland offer examples that should not be forgotten. However, during the League, the two parties called for aid from the Spanish, the English, the Italians, and the Germans, these counter-balancing and not disturbing the equilibrium that the French armies maintained between themselves.

Charles X was wrong to use bayonets to maintain the decrees; his ministers could not justify, whether obeying orders or not, the shedding of the people’s and the soldiers’ blood, without any hatred dividing them, just as Terrorists willingly recreated the system of the Terror when there was no longer a Terror. But Charles X was also wrong not to accept a fight when, after conceding on all points, the fight was brought to him. He had no right, having set the crown on his grandson’s forehead, to say to that new Joas: ‘I have placed you on the throne to train you for exile, so that unfortunate, exiled, you can bear the weight of my years, my proscription and my sceptre.’ He should not have at the same moment granted Henri V a crown and robbed him of France. In making him King, he had marked him to die on this soil where the dust of Saint-Louis and Henri IV is mingled.

Well, after this blood-letting, I have recovered my senses, and in these things I merely see the completion of human destiny. The Court, triumphant by means of force, would have destroyed public freedom; it would have been erased just the same one day; but it would have retarded the development of society by many years; all that comprised the monarchy writ large would have been opposed by the re-established congregation. In the final result, events have followed the drift of civilisation. God made powerful men suit his secret purposes: he gave them faults which destroyed them when they needed to be destroyed, because he did not wish qualities badly applied by an erring mind to oppose the decrees of Providence.

Book XXXIII: Chapter 5: The Palais-Royal – Conversations – A last political temptation – Monsieur de Saint-Aulaire

BkXXXIII:Chap5:Sec1

The Royal family, by leaving, reduced me to my own resources. I no longer thought of what I might be called upon to say in the Chamber of Peers. To write was impossible: if an attack had come from the enemies of the crown; if Charles X had been overthrown by a conspiracy from outside, I would have picked up my pen, and having been left my independence of thought, I would have worked hard to rally a large party to the remnants of the monarchy; but the attack came from the crown itself; the ministers had violated the twin principles of liberty, they had made royalty break its oath, not intentionally doubtless, but in fact; by that they had also stolen my power. What could I dare to say in favour of the decrees? How could I still boast of the sincerity, candour, and chivalry of the Legitimacy? How could I claim that they were the best guarantee of our interests, our laws, and our freedom? A champion of the ancient royalty, that royalty had robbed me of my weapons, and left me naked to my enemies.

So I was quite surprised when, reduced to this state of weakness, I found myself sought after by the new royalty. Charles X had disdained my services; Philippe made an effort to attach me to him. First of all Monsieur Arago spoke to me in an elevated and forceful manner on behalf of Madame Adélaïde; then Comte Anatole de Montesquiou came to Madame Récamier’s one morning and found me there. He told me that Madame la Duchesse d’Orléans and Monsieur le Duc d’Orleans would be charmed to see me, if I would go to the Palais-Royal. At that time they were occupied with the declaration which would transform the Lieutenant-Generalship of the Kingdom into a monarchy. Perhaps, before I could make any pronouncements, His Royal Highness may have judged it opportune to try and weaken my opposition. He may also have thought I might consider myself freed by the flight of the three kings.

‘Queen Marie Amélie, After the Portrait by Franz Xaver Winterhalter’

Dictionary of Painters and Engravers - Michael Bryan, George Charles Williamson (p606, 1903)

Internet Archive Book Images

Monsieur de Montesquiou’s overtures surprised me. Yet I did not reject them, since, without flattering myself regarding any chance of success, I thought I might be able to communicate some honest truth. I went to the Palais-Royal with the future queen’s Knight of Honour. Escorted to the entrance giving on the Rue de Valois, I found Madame la Duchesse d’Orléans and Madame Adélaïde in their little apartment. I had been honoured by being presented to them previously. Madame la Duchesse d’Orléans made me sit beside her, and immediately said; ‘Ah! Monsieur de Chateaubriand, we are most unfortunate. If all the parties would unite, perhaps they might yet save the situation! What do you think?

‘– Madame,’ I replied, ‘nothing is so straightforward: Charles X and Monsieur le Dauphin have abdicated: Henri is now King; Monseigneur le Duc d’Orléans is Lieutenant-General of the Kingdom: let him act as Regent during Henri V’s minority and all is settled.’

‘– But, Monsieur de Chateaubriand, the people are agitating; we will descend into anarchy.’

‘– Madame may I ask you what Monseigneur le Duc d’Orléans’ intentions are? Will he accept the crown if it is offered to him?’

The two Princesses were hesitant in replying. Madame la Duchesse d’Orléans replied after a moment’s silence:

‘– Think, Monsieur de Chateaubriand of the evils that could arise. All honest people must work together to save the Republic. In Rome, Monsier de Chateaubriand, you might render great service, or even here, if you do not wish to leave France!’

‘– Madame do not forget my devotion to the young King and to his mother.’

‘– Oh, Monsieur de Chateaubriand, have they treated you so well!’

‘– Your Royal Highness would not have me deny my whole existence.’

‘– Monsieur de Chateaubriand, you do not know my niece: she is so thoughtless.poor Caroline! ...I am going to find Monsieur le Duc d’Orleans, he will be better at persuading you than I am.’

The Princess gave an order, and after a few minutes Louis-Philippe arrived. He was untidily dressed and looked extremely tired. I rose, and the Lieutenant-General of the Kingdom tackled me:

‘– Madame la Duchesse d’Orléans must have told you of the unfortunate position we are in.’

And suddenly he uttered idyllic words on the happiness which he found in the countryside, and on the tranquil life which his tastes led him to enjoy with his children. I seized the opportunity of a pause between two verses to add a respectful comment of my own, and to repeat virtually what I had said to the Princesses.

‘Ah,’ he cried, ‘that would be my wish! How I would love to be the tutor and guardian of that child! I think as you do, Monsieur de Chateaubriand: to accept the Duc de Bordeaux would certainly be the best thing to do. Only I fear that events may prove too powerful for us.’ – ‘Too powerful for us, Monseigneur? Are you not invested with every power? Let us rejoin Henri V; summon the Chambers and the army to you, outside Paris. At the first rumour of your departure, all the excitement will cease, and they will seek to shelter beneath your enlightened and protective power.’

While I was speaking, I was watching Philippe. My advice caused him great uneasiness; I saw the desire to be king written on his brow. ‘Monsieur de Chateaubriand,’ he said without looking at me, ‘the matter is more complicated than you think; it is not like that. You do not understand the danger we are in. A furious attack could be mounted on the Chambers, with every excess of force, and we have nothing left to defend ourselves with.’

That sentence falling from Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans’ lips pleased me because it furnished me with the opportunity for a peremptory reply. ‘I understand the difficulty, Monseigneur; but there is a way of surmounting it. If you find yourself unable to rejoin Henri V as I have just proposed, you can take another route. The Session is about to open: whatever may be the first proposition put by the Deputies, declare that the present Chamber lacks the necessary powers (which is indeed true) to settle the form of government; say that France must be consulted, and a new assembly must be elected with ad hoc powers to settle so great a matter. Your Royal Highness in that way will be adopting the most popular position; the Republican Party, which is a risk to you today, will praise you to the skies. During the two months it will take to form a fresh legislature, you can re-organise the National Guard; all your friends and those of the young King will work alongside you in the provinces. Let the Deputies come then and plead the cause I am defending, publicly, at the rostrum. That cause, secretly supported by you, would obtain the largest majority of the votes. The moment of anarchy having passed, you will have nothing more to fear from Republican violence. I do not even think it very difficult for you to bring General Lafayette and Monsieur Lafitte over to your side. What a role for you Monseigneur! You will reign for fifteen years in your pupil’s name; in fifteen years, it will be time for us all to rest; you will have had the glory, unique in history, of being in a position to take the throne and of having left it to the legitimate heir; and at the same time you will have helped that child become one of the luminaries of the century, and will have rendered him capable of ruling France: one of your daughters might one day bear the sceptre with him.’

Philippe’s gaze wandered vaguely somewhere over my head: ‘Excuse me, Monsieur de Chateaubriand,’ he said, ‘I have left a deputation in order to speak to you, to whom I must return. Madame la Duchesse d’Orléans will have explained to you how happy I would be to do what you desire; but, be aware, that it is only I who hold back the threatening tide. If the Royalist party is not massacred, it will owe its survival to me alone.

‘– Monseigneur,’ I replied, to this statement which was so unexpected and so far from the subject of our conversation, ‘I have witnessed massacres: those who passed through the Revolution were hardened. Greybeards do not allow themselves to be frightened by things which make conscripts fear.’

His Royal Highness withdrew, and I went to find my friends:

‘– Well?’ they cried.

‘– Well, he wants to be King.’

‘– And Madame la Duchesse d’Orléans?

‘– She wants to be Queen.

‘– They told you so?

‘– The one spoke to me of sheep-pens, the other of the perils which threaten France and the thoughtlessness of poor Caroline; both wished me to understand that I could be useful to them, and neither would look me in the face.’

Madame la Duchesse d’Orléans wished to see me again. Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans did not involve himself in this conversation. Madame Adélaïde was there as before. Madame la Duchesse d’Orléans explained clearly the favours with which Monseigneur le Duc d’Orléans proposed to honour me. She had the goodness to mention what she called my influence over public opinion, the sacrifices I had made, and the aversion which Charles X and his family had always shown for me, despite my services. She told me that if I would join the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, His Royal Highness would have great delight in re-establishing me there; but that I might perhaps prefer to return to Rome, and that she (Madame la Duchesse d’Orléans) would take great pleasure in seeing me adopt this last suggestion, in the interests of our sacred religion.

‘Madame,’ I replied immediately in a forceful manner: ‘I see that Monsieur le Duc d’Orleans’ mind is made up; I assume that he has weighed the consequences, and has seen the years of misery and danger which he will have to pass through; I have therefore nothing more to say. I have not come here to demonstrate any lack of respect for the Bourbon line; moreover I have only gratitude for Madame’s kindness. Leaving the major objections to one side, reasons deriving from principles and events, I beg Your Royal Highness to allow me to speak of what concerns myself.

You have chosen to speak of what you call my influence over public opinion. Well, if that influence is real, it is founded on public esteem; now, I would lose that esteem the moment I changed flags. Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans might consider he had acquired a supporter, but he would merely have a wretched phrase-maker in his service, an oath-breaker whose voice would no longer be heard, a renegade whom anyone would have the right to throw mud at, or spit in his face. To the wavering words he might stammer in favour of Louis-Philippe, would be contrasted whole volumes he has published in support of the line which has abdicated. Am I not the person, Madame, who wrote the pamphlet Of Bonaparte and the Bourbons, the articles on the arrival of Louis XVIII at Compiègne, the Report of the King’s Council at Ghent, and the History of the life and death of Monsieur le Duc de Berry? I do not know if there is a single page of mine in which the name of my former kings’ family does not count for something, and in which it is not surrounded by my protestations of love and loyalty; something which admits a character of personal attachment all the more remarkable, in that Madame knows I do not believe in kings. At the mere thought of desertion, a blush mounts to my face; I would go and throw myself in the Seine tomorrow. I beg Madame to excuse the force of my words; I am filled with my sense of her kindness; I will retain a deep and grateful memory of it, but she would not wish me to be dishonoured: have pity on me, Madame, have pity!’

I had remained standing and, bowing, I took my leave. Mademoiselle d’Orléans had said not a word. She rose, and as she departed, said to me: ‘I do not pity you, Monsieur de Chateaubriand, I do not pity you!’ I was astonished at those few words, and the accent with which they were pronounced.

That was my last political temptation; I could have considered myself an honourable man according to Saint Hilaire, since he affirms that men are exposed to devilish enterprises because of their holiness: Victoria ei est magis, exacta de santis: his victory is greater when won against the holy. My refusal was that of a fool; where is the public who would value it? Could I not have ranged myself with those men, virtuous sons of this earth, who serve their country before everything else? Unfortunately, I am not a creature of the present age, and never bow to fortune. There is nothing in common between me and Cicero; but his weakness is not an excuse: posterity cannot pardon a moment of weakness in one great man for the sake of another great man; what would have become of my poor life if it had lost its only virtue, its integrity, for the sake of Louis-Philippe d’Orléans?

On the evening of the conversation above at the Palais-Royal, I met Monsieur de Saint-Aulaire at Madame Récamier’s. I took no pleasure in asking about his affairs, but he asked about mine. He was fresh from the country and still full of the events he had witnessed: ‘Ah!’ he cried, ‘How pleased I am to see you! Here’s a fine thing! I hope we of the Luxembourg will do our duty. It would be strange if the Peers were to dispossess Henri V of the crown! I am sure you will not leave me to take to the rostrum alone.’

As my decision was made, I was quite calm; my response to Monsieur de Saint-Aulaire’s ardour appeared cool. He left, spoke to his friends, and left me to take the rostrum alone: long live men of spirit with light hearts and frivolous minds!

Book XXXIII: Chapter 6: The Republican Party’s last gasp

BkXXXIII:Chap6:Sec1

The Republican Party was still struggling under the feet of the friends who had betrayed it. On the 6th of August, a deputation of twenty members designated by the central committee of the twelve districts of Paris presented itself at the Chamber of Deputies to hand over an address which General Thiard, and Monsieur Duris-Dufresne spirited away from the volunteer delegation. In this address it was said: ‘that the nation could recognise as a constitutional government neither an elected Chamber nominated during the existence and under the influence of the monarchy it had overthrown, nor an aristocratic Chamber, whose institution was in direct conflict with the Princes who had placed weapons in its (the nation’s) hands; that the central committee of the twelve arrondissements granting a de facto and highly provisional power to the Chamber, as a revolutionary necessity, to carry out any urgent measures, called with all their might for a free and popular election of representatives who would truly reflect the needs of the people; and that only the primary assemblies could lead to this result. If it were otherwise, the nation would reduce to nothing all who tried to obstruct it in the exercise of its rights.’

All this was quite reasonable, but the Lieutenant-General of the Kingdom aspired to the throne, and fear and ambition had hastened to grant it to him. The people of today wanted a revolution but had no idea how to go about it; the Jacobins, whom they modelled themselves on, threw the men of the Palais-Royal and the cowards from the two Chambers into the river. Monsieur de Lafayette was reduced to impotent expressions of his wishes: delighted to have revived the National Guard, he allowed Philippe, whose nurse he had thought to be, to toy with him like a new-born babe; he was dazed with happiness. The old General represented freedom anaesthetised, while the Republic of 1793 was nothing but an empty skull.

The truth is that the Chamber truncated and without a mandate had no right to dispose of the crown: a Convention expressly gathered together, and formed from the House of Lords and a newly elected House of Commons settled the fate of James II’s throne. Moreover it is certain that the rump of the Chamber of Deputies, the 221, imbued with the traditions of hereditary monarchy under Charles X, showed no real aptitude for elective monarchy; they halted it at its inception, and forced it to revert to principles of quasi-legitimacy. Those who forged the new monarchy’s sword introduced a flaw into it which sooner or later would make it shatter.

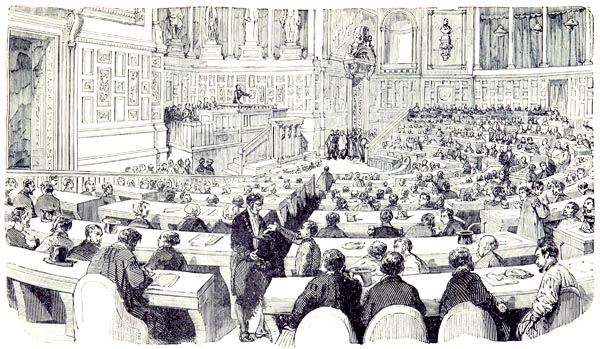

Book XXXIII: Chapter 7: The 7th of August – A session of the Chamber of Peers – My speech – I leave the Luxembourg Palace never to return – My resignations

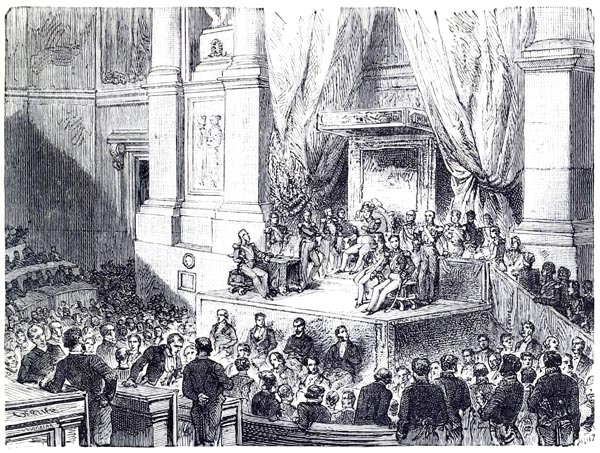

‘Séance au Luxembourg sur l'Organisation du Travail, en 1818’

Paris à Travers les Siècles. Histoire Nationale de Paris et des Parisiens Depuis la Fondation de Lutèce Jusqu'à Nos Jours, Vol 03 - Gourdon de Genouillac, Nicolas Jules Henri (p215, 1879)

The British Library

BkXXXIII:Chap7:Sec1

The 7th of August was a memorable day for me; it was the day on which I had the pleasure of finishing my political career as I had begun; a pleasure rare enough these days that one should rejoice in it. The declaration of the Chamber of Deputies concerning the vacant monarchy was carried to the Chamber of Peers. I went to sit in my place on the highest rank of chairs, facing the President. The Peers seemed to me both preoccupied and weary. If some bore the pride of their impending disloyalty on their brow, others bore the shame of a remorse they had not the courage to express. Gazing at this assembly I said: ‘So! Those who received gifts from Charles X while he prospered will now desert him in his misfortune! Shall they whose special mission was to defend the hereditary monarchy, those courtiers who enjoyed their closeness to the King, betray him? They sat at his door at Saint-Cloud; they embraced him at Rambouillet; he pressed their hands in a last farewell; will they now raise those hands, still warm from the last clasp, against him? Will that Chamber, which resounded for fifty years with their protestations of devotion, now echo to their oath-breaking? Yet, it is because of them that Charles X has fallen; it is they who urged the decrees; they stamped their feet with delight when they appeared, when they thought themselves conquerors, in that silent moment that precedes the clap of thunder.’

These thoughts swam confusedly and mournfully through my mind. The peerage had become a triple receptacle of corruptions, those of the Old Monarchy, the Republic and the Empire. As for the Republicans of 1793, transformed into Senators, and the Bonapartist Generals, from them I expected familiar behaviour: they deposed an extraordinary man to whom they owed everything: they would depose a King whom they had confirmed in possession of the goods and honours which they had heaped on their first master. Let the wind change direction and they would depose the usurper to whom they prepared to throw the crown.

I mounted the rostrum. There was a profound silence; the faces showed embarrassment, everyone turned his chair away and gazed at the ground. Save for a few Peers resolved, as I was, to resign, no one dared raise their eyes to the level of the rostrum. I record my speech here because it sums up my life, and because it is my principal title to future esteem.

‘Gentlemen,

The declaration brought to this Chamber is much simpler for me than for those of you who profess a different opinion to mine. One fact, in this declaration, above all others, sprang to my eyes, or rather pained them. If we were in normal times, I would doubtless examine carefully the changes that are proposed in the operation of the Charter. Several of those changes were proposed by me. I am astonished only that anyone could speak to this House of a reactionary measure concerning the Peers created by Charles X. I am not known for my liking for such creation of Peers in batches, and you know I have opposed even the threat of it; but to act as judges of our colleagues, to strike from the table of Peers whomever one wishes, when one happens to be strongest, smacks of proscription. Do you wish to destroy the Peerage? So be it: better to lose one’s life than beg for it.

I reproach myself already for uttering these few words concerning a detail which, important though it may be, is lost in the grandeur of present events. France is directionless, and I will concern myself with what adds or detracts from steering a vessel whose rudder is shattered! I will ignore therefore everything in this declaration of the elected Chamber which is of secondary interest, and, keeping to the sole fact, true or pretended, that it proclaims, that of the vacancy of the throne, I will come straight to the point.

A preliminary question must be dealt with: if the throne is vacant, we are free to choose our form of government.

Before offering the crown to some individual or other, it is helpful to know what kind of political structure will constitute the social order. Shall we establish a republic or a new monarchy?

ill a republic or a new monarchy offer France sufficient guarantee of longevity, strength and peace?

A republic would have against it first of all the memory of the Republic itself. Those memories are by no means erased. Those times are not forgotten when Death marched, between Liberty and Equality, its arms round both. When you fall into fresh anarchy will you waken Hercules from the marble, he alone capable of strangling the monster? Of men worthy to live in men’s minds there have been only five or six in our history: posterity may see another Napoleon in a thousand years or so, as for us, do not expect it.

Then, given the state of our morals, and our relations with the governments surrounding us, a republic, if I am not mistaken, does not seem to me to be viable at the moment. The first problem would be to obtain a unanimous vote from the French people. What right has the population of Paris to force the population of Marseilles or any other town to be part of a republic? Will they have one republic or twenty or thirty republics? Shall they be federated or independent? Let us pass over these obstacles. Let us suppose a single republic: with our in-born sense of familiarity, do you think that a President, however grave, however respectable, however able, could last for a year in charge of our affairs without being tempted to resign? Barely protected by the law and by tradition, thwarted, libelled, insulted morning and evening by hidden rivals and trouble-makers, he would inspire little confidence among the commercial and property-owning classes; he would possess neither the dignity needed to deal with foreign cabinets, nor the power necessary to maintain order at home. If he employs revolutionary measures, the republic will be rendered odious; a troubled Europe will profit from such divisions, foment them, and intervene, and we will find her once more involved in frightful struggles. Representative republicanism is without doubt the future state of the world, but those times have not yet arrived.

I pass to the monarchy.

A king, named by the Chambers or elected by the people, will always be a novelty, however he acts. Now, I assume that we wish for freedom, above all freedom of the Press by means of which, and for which, the people have achieved a remarkable victory. Well! Any new monarchy will be forced, sooner or later, to gag that freedom. Did not Napoleon himself confess it? Daughter of our miseries and slave of our glory, the freedom of the Press will have no security except under a government that is already deep-rooted. A monarchy, bastard child of a blood-stained night, has it nothing to dread from freely expressed opinion? If these people may preach a republic, and those some other system, do you not fear that you will soon be obliged to have recourse to the laws of ‘exception’, despite the anathema against censure added to article 8 of the Charter?

Then, friends of order and freedom, what will you have gained from the changes you propose? You will fall perforce into a republic, or into legal servitude. The monarchy will be inundated and swept away by the torrent of democratic laws, or the monarch by the work of factions.

In the first intoxication of success, you think everything is easy; you hope to meet all exigencies, all moods, all interests; you flatter yourself that everyone will set aside their personal views and vanities; you believe that superiority of intellect and the wisdom of government will surmount numberless difficulties: but, after a few months, practice refutes theory.

I only present to you, gentlemen, some of the problems associated with a republic or a new monarchy. If both have their dangers, there is a third way, and that way is well-worth my spending a few words on.

Weak government has tarnished the crown, and its ministers have capped violation of the law with murder; they have toyed with oaths sworn to heaven, and laws sworn to earth.

Foreigners, you who twice entered Paris without resistance, know the true cause of your success: you presented yourselves in the name of legalised force. If you rushed today to aid tyranny, do you think the gates of the capital of the civilised world would open so easily to you? The French nation has flourished, since your departure, under a constitutional legal frame-work, and our forty-year old offspring are now giants; our conscripts in Algeria, our colleges in Paris, will show you the sons of the conquerors of Austerlitz, Marengo, and Jena; but sons strengthened by all with which freedom enhances glory.

No defence was more legitimate or more heroic than that of the people of Paris. They did not rise against the law; as long as the social pact was respected, the people remained peaceful; they suffered insult, provocation and threats without complaint; they owed their wealth and their blood in exchange for the Charter, they have given both.

But when having lied to them to the end, suddenly the hour of slavery rang; when the conspiracy of stupidity and hypocrisy promptly emerged; when a Palace Terror organised by eunuchs thought to revive the Terror of the Republic and the iron yoke of Empire, then the people armed themselves with intelligence and courage; shopkeepers proved able to breathe powder-fumes as easily as others, and a corporal and four soldiers were needed to overcome them. A century could not have better nurtured the fate of a nation than the three suns which have just shone on France. A great crime has been committed; it has produced the energetic expression of a principle: should we overthrow the established order of things, because of that crime and the moral and political triumph that followed it? Let us reflect:

Charles X and his descendants are deposed or have abdicated, as it pleases you to hear; but the throne is not vacant: after them there is a child; would you condemn his innocence?

What blood cries out against him today? Would you dare to claim that it is his father’s? This orphan, raised in a patriotic school, with a love of constitutional government and imbued with the ideas of this century, would be a king who could relate to the needs of the future. It is to the administrator of his guardianship that the declaration on which you are about to vote should have been made; reaching his majority, the young monarch would renew the oath. The present King, the actual King would be Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans, Regent of the Kingdom, a Prince who has lived among his people, and who knows that monarchy today can only be a monarchy conducted with reason and consent. This natural combination seems to me to be a means of major conciliation, and would save France maybe from the disturbances which are the consequence of violent changes in a State.

Is it truly reasonable to say that a child, separated from his masters, would not have time to forget even their names before reaching manhood; or to say that he would remain infatuated with certain dogmas attached to his birth, after a lengthy popular education?

It is not because of some sentimental devotion or nursemaid’s tenderness transmitted from cradle to cradle, from Henri IV to the young Henri, that I plead a cause where everyone would once more be against me, if it triumphed. I do not wish to partake of romance, or chivalry, or martyrdom; I do not believe in the divine right of kings, I believe in the power of revolutions and events. I do not even invoke the Charter; I raise my sights higher; I draw on the sphere of philosophy of the age in which my life will end: I propose the Duc de Bordeaux simply as a necessity, with a better cause that that which has been argued.

I know that in removing that child, they wish to establish the principle of the sovereignty of the people: a foolishness of the ancient school, which shows that, in relation to politics, our former democrats have made no more progress than the veteran royalists. There is no absolute sovereignty anywhere; freedom does not flow from political rights, as was thought in the eighteenth century; it derives from natural rights, which can be seen to exist under any form of government, and may exist and exist more extensively under a monarchy than a republic; but this is neither the time nor the place to indulge in a course of politics.

I will content myself with remarking that, when a nation has dispossessed itself of its monarch, it has often dispossessed itself of liberty too; I will merely observe that the principle of hereditary monarchy, absurd at first sight, has been found, by custom, preferable to the principle of an elected monarchy. The reasons are so evident that I do not need to develop them. You will choose a king today: who will stop you choosing another one tomorrow? The law, you say? What law? Indeed, it is one you yourselves frame!

There is a much simpler way of deciding the issue, which is to say: ‘We do not want the elder line of Bourbons. And why do we not want it? Because we are victorious, we have triumphed in a just and holy cause; we are claiming a double right of conquest.’

Fine: proclaim the sovereignty of force. Then guard yourselves carefully against that force; since if it escapes your control in a few months time, you will have no room to complain. Such is human nature! The clearest minds and the most just do not always rise above success. They are the first, those spirits, to invoke the law against violence; they support that law with all the superiority of their talents, and, at the very moment when the truth of what they are saying is demonstrated by the most abominable abuse of force and by the overthrow of that force, the conquerors seize the weapons they have broken! Dangerous tools which will wound their hands without being of service to them.

I have carried the battle onto my adversaries’ ground; I am not going to dwell in the past beneath the banner of the dead, a banner not without its glory, but which is draped around the staff which bears it, because it lacks a breath of wind to raise it. When I stirred the dust of thirty-five Capets, I was not employing an argument one would wish solely to rely on. The idolatry of names is abolished: monarchy is no longer a religion: it is a form of politics preferable at this instant to any other, because it can better maintain order and freedom.

A vain Cassandra, I have wearied the Crown and the Peerage with my fruitless warnings; it only remains for me to sit amongst the fragments of a shipwreck I have so many times predicted. I recognise all sorts of forces in misfortune, except the force that could release me from my oaths of loyalty. I must also preserve a lifetime’s consistency: after all I have done, said and written in support of the Bourbons, I would be the lowest of wretches if I disowned them at the moment when they make their way into exile for the third and final time.

I leave fear to those generous loyalists who have never sacrificed their position or a single farthing to their loyalty; to those champions of the altar and the throne, who formerly treated me as a renegade, apostate, and revolutionary. Pious libellists, the renegade calls to you! Come then and stammer a word, a single word beside him, in support of that unfortunate master who heaped his gifts on you and whom you have ruined! Provokers of many a coup d’État, asserters of constitutional power, where are you? You are hiding in the mud from whose depths you valiantly raise your head to calumniate the true servants of the King; your silence today matches your language of yesterday. Let all those valiant knights whose projected exploits have caused the descendants of Henri IV to be chased with pitchforks tremble now as they squat beneath the tricolour cockade; it is natural enough. The noble colours with which they are adorned protect the person, but fail to conceal his cowardice.

Furthermore, in expressing myself freely at this rostrum, I do not at all consider it an act of heroism. We are no longer in an age when their opinions cost men their lives; if we were, I would have spoken a hundred times more loudly. The best shield is a breast that does not fear to find itself open to the enemy. No, gentlemen, we should not fear either a nation whose sense matches its courage, nor generous Youth, which I admire, with which I sympathise with all the power of my spirit, to whom I wish, as I do my country, honour, glory, and liberty.

Furthest from my thoughts above all is the idea of casting seeds of division throughout France, and that is why I have denied my speech too passionate a tone. If I had the personal conviction that a child should be left in the obscure and happy ranks of society, to assure the repose of thirty three million people, I would regard any opposition to the needs of the moment as a crime: I do not have that conviction. If I had the right to dispose of a crown, I would lay it willingly at the feet of Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans. But I only see a tomb in Saint-Denis vacant, and not a throne.

Whatever fate awaits the Lieutenant-General of the Kingdom, I will never be his enemy if he brings happiness to my country. I only ask to preserve my freedom of conscience and the right to go and die wherever I can find freedom and repose.

I vote against the proposals in the declaration.’

BkXXXIII:Chap7:Sec2

I had been calm enough when beginning my speech; but gradually emotion overcame me; when I arrived at the passage; A vain Cassandra, I have wearied the Crown and the Peerage with my fruitless warnings, words failed me, and I was forced to put my handkerchief to my eyes to wipe away tears of emotion and bitterness. Indignation gave me back my voice for the paragraph which followed: Pious libellists, the renegade calls to you! Come then and stammer a word, a single word beside him, in support of that unfortunate master who heaped his gifts on you and whom you have ruined! My gaze fell then on the ranks to which I addressed those words.

Several Peers seemed stunned; they sank into their chairs to the point where I could no longer see them behind their colleagues sitting motionless in front of them. This speech had several repercussions: all the parties there were hurt, but all kept quiet, because I had placed a great sacrifice alongside great truth. I descended from the rostrum; I left the chamber; I went to the cloakroom, I took off my Peer’s costume, my sword, and my plumed hat; I detached the white cockade from it, kissed it, and put it in the little pocket on the left side of my black frock coat which I donned, and buttoned over my heart. My servant picked up the Peer’s clothes, and I abandoned, while shaking the dust from my feet, that Palace of treason, which I have never re-entered.

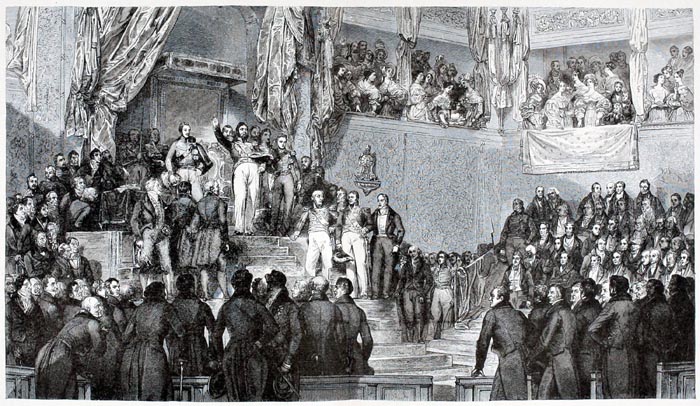

‘The Duke of Orleans (Louis Philippe I) Takes the Oath to the Constitution on August 9, 1830 in Presence of the Chambers.

Reduced facsimile of an engraving by Frilley of the painting by Eugene Deveria (1805-1875) (Versailles, Historical Gallery)’

A History of all Nations From the Earliest Times; Being a Universal Historical Library - John Henry Wright (p187, 1905)

Internet Archive Book Images

On the 10th and 12th of August, I finished despoiling myself and sent in my various letters of resignation;

‘Paris, this 10th of August 1830.

Monsieur le Président de la Chambre des Pairs,

Unable to swear an oath of loyalty to Louis Philippe d’Orléans as King of the French, I find myself legally incapacitated such as to prevent me from attending the sessions of the hereditary Chamber. A solitary mark of King Louis XVIII’s generosity and of royal munificence remains to me: that is an income as a Peer of twelve thousand francs, which was granted to me to maintain, if not in style, but at least with the freedom to satisfy my primary needs, the high dignity to which I was called. It would not be right for me to retain a favour attached to the exercise of functions which I cannot fulfil. Consequently, I have the honour to resign into your hands my income as a Peer.’

‘Paris, this 12th of August 1830.

Monsieur le Ministre des Finances,

An income as a Peer remains to me, due to Louis XVIII’s generosity and the National munificence, of twelve thousand francs, arranged as a life annuity, inscribed in the grand ledger of public debts, and only transmissible to the first generation by direct title. Being unable to swear the oath of allegiance to Monseigneur le Duc d’Orléans as King of the French, it would not be right for me to continue to accept the income attached to functions I no longer exercise. Consequently, I am resigning it into your hands: it will have ceased to accrue to me on the day (10th of August) on which I wrote to Monsieur le Président de la Chambre des Pairs telling him that it was impossible for me to swear the required oath.

I have the honour to be, with the highest esteem, etc.’

‘Paris, this 12th of August 1830.

Monsieur le Grand Référendaire

I have the honour to send you a copy of two letters which I have addressed, one to Monsieur le Président de la Chambre des Pairs, the other to Monsieur le Ministre des Finances. You will see that I renounce my income as a Peer, and that in consequence my authorised representative will only draw on that income due up to the 10th of August when I announced that I could not take the oath.

I have the honour to be, with the highest esteem, etc.’

‘Paris, this 12th of August 1830.

Monsieur le Ministre de la Justice,

I have the honour to send you my resignation as Minister of State.

I am, with the highest esteem,

Monsieur le Ministre de la Justice,

Your very humble and obedient servant.’

I was as naked as a lesser St John the Baptist; but for a long time I had been accustomed to live on wild honey, and I had no fear that Herodias’ daughter would covet my grey head.

My gilded embroidery, straps, fringes, braiding and epaulettes, sold to a goldsmith, and melted down by him, brought me in seven hundred francs, the end product of all my grandeur.

Book XXXIII: Chapter 8: Charles X embarks at Cherbourg

BkXXXIII:Chap8:Sec1

Now, where was Charles X? He was travelling towards exile, accompanied by his Bodyguards, escorted by three Commissioners, crossing France without even exciting the curiosity of the peasants ploughing their furrows beside the highroad. In two or three little towns, hostile demonstrations were mounted; in others, the bourgeois and the women showed signs of pity. One must remember that Bonaparte made no more noise passing from Fontainebleau to Toulon, that France was no more moved, and that the victor in so many battles was nearly massacred at Orgon. In this weary land, the greatest events are no more than dramas played for our amusement: they occupy the spectator while the curtain is raised, and when it falls it leaves a vain memory. Sometimes Charles X and his family halted at miserable transport-stops to eat a meal at the end of a dirty table at which the carters dined with them. Henri V and his sister amused themselves in the yard among the innkeeper’s pigeons and pullets. As I have said: the monarchy departed, and people went to their windows to watch it pass.

Heaven was pleased at this moment to insult the victors and the vanquished. While it was still being claimed that the whole of France had been indignant at the decrees, King Philippe received various addresses from the provinces, sent to King Charles X to congratulate the latter on the salutary measures he had taken which would preserve the monarchy.

The Bey of Tittery, for his part, sent to the dethroned monarch, who was travelling towards Cherbourg, the following submission:

‘In the name of God, etc, I recognize as absolute sovereign Charles X, the great and victorious; I will pay him tribute, etc.’ One could not have toyed more ironically with the fortunes of each. Today revolutions are engineered mechanically; they are manufactured so swiftly that a monarch, still king at the borders of his State, is already no more than an exile in his own capital.

In the country’s indifference to Charles X, there was something more than weariness: one must recognise the progress of democratic ideas and the assimilation of rank. In a former epoch, the fall of a King of France would have been an enormous event; time has toppled monarchy from the heights on which it was placed, kings have been brought close to us, the distance separating them from the popular classes has diminished. If one was hardly surprised to meet the descendant of Saint Louis on the highroad like the rest of the world, it was not through any spirit of hatred or design, it was quite simply through a feeling of social levelling, which had penetrated minds and acted on the masses without them being aware.

Curses, Cherbourg, on your ominous environs! It was near Cherbourg that the winds of anger deposited Edward III to ravage our country; it was not far from Cherbourg that the winds of an enemy victory shattered Tourville’s fleet; it was at Cherbourg that the winds of deceptive prosperity nudged Louis XVI towards the scaffold; it was to Cherbourg that a wind from who knows what shore carried our former Princes. The coast of Great-Britain, where William the Conqueror landed, witnessed the disembarkation of Charles the Tenth without lance or pennon; he went to find at Holyrood, the memories of his youth, hung on the walls of that palace of the Stuarts, like old engravings yellowed by time.

‘The Harbor at Cherbourg’

Berthe Morisot (French, 1841-1895)

Yale University Art Gallery

Book XXXIII: Chapter 9: How the July Revolution will be viewed

BkXXXIII:Chap9:Sec1

I have described the Three Days as they unfolded before me: a certain contemporary colouring, true at the moment when it occurs, false when the moment has gone, thus extends across the picture. There is no revolution so prodigious that, if described from minute to minute, is not reduced to smaller proportions. Events emerge from the womb of things, like men from their mothers’ wombs, accompanied by the failings of nature. Misery and grandeur are twin sisters, they are born together; but if the birth-pangs are vigorous, the pains die-away after a time, and only the grandeur remains. To judge the reality that remains impartially, one must adopt the point of view from which posterity will consider the completed event.

Detaching myself from the meanness of character and action of which I had been the witness, considering the July Days only in terms of what will remain, I spoke rightly in my speech to the Chamber of Peers: ‘the people armed themselves with intelligence and courage; shopkeepers proved able to breathe powder-fumes as easily as others, and a corporal and four soldiers were needed to overcome them. A century could not have better nurtured the fate of a nation than the three suns which have just shone on France.’

Indeed, the people, strictly speaking, had been brave and generous during the day of the 28th. The Guard had lost more than three hundred men, dead or wounded; it rendered full justice to the lower classes, who alone fought on that day, and among whom were included some tainted individuals, who nevertheless brought them no dishonour. The students from the École Polytechnique, emerging from their college too late to take part in events, were made leaders of the people on the 29th, with an admirable simplicity and naivety.

Champions absent from the people’s struggle came to join its ranks on the 29th, when the greatest danger was past; others, equally victorious, did not participate in victory until the 30th and 31st.

On the troops side, almost the same thing happened, the soldiers and officers were barely engaged; the staff, who had previously deserted Bonaparte at Fontainebleau, stood on the heights of Saint-Cloud, looking to see which way the wind would blow the powder-fumes. They formed a queue at Charles X’s accession; at his abdication no one was to be found.

The moderation of the common people matched their courage; order came swiftly out of confusion. One must have seen the half-naked workers, on guard at the gates of the public gardens, to prevent according to instructions other ragged workers from entering, to gain an idea of that power of duty which gripped the servants become masters. They could have taken the price of their blood, and let themselves be tempted by their poverty. There was no sight, as on the 10th of August 1792, of the Swiss being massacred as they fled. All views were respected; never, with a few exceptions, has victory been less abused. The victors, carrying wounded guardsmen through the crowd shouted: ‘Respect the brave!’ When a soldier died, they said: ‘Peace to the dead! The fifteen years of the Restoration, under a constitutional regime, had given birth among us to that spirit of humanity, legality and justice which twenty-five years of revolutionary and military spirit could not have produced. The right to force introduced into our conduct seemed to have become a common right.

The consequences of the July Revolution will be felt. That revolution has announced the end of all monarchies; kings cannot reign today except by strength of arms; a viable method for the moment, but who knows for how long: the age of repeated Jannissaries is over.

Thucydides and Tacitus are of little assistance to us with regard to the Three Days; we need Bossuet to explain events produced by Providence; a genius who sees all, but without transgressing the limits set by his reason and his splendour, like the sun which moves between two brilliant horizons, and which Orientals call the slave of God.

Do not seek too near to us the source of a motion placed far off: the mediocrity of men, inexplicable dissent, hatred, ambition, the presumption of some, the prejudices of others, secret conspiracies, radical factions, well or badly taken measures, courage or lack of courage; all these things are accidents, not causes of the event. When they said they no longer wanted the Bourbons, who had become odious because they were considered to have been imposed on France by foreign powers, that proud disdain explains nothing adequately.

The July actions do not belong properly to politics; they belong to the social revolution which acts ceaselessly. Linked to the general revolution, the 28th of July 1830 is merely the inevitable successor to the 21st of January 1793. The work of our upper debating chambers had been suspended, it had not been ended. During the course of twenty years, the French became accustomed, as the English did under Cromwell, to being governed by other masters than their former kings. The fall of Charles X was a consequence of the decapitation of Louis XVI, as the dethronement of James II was a consequence of the execution of Charles I. The Revolution seemed extinguished by Bonaparte’s glory, and Louis XVIII’s freedoms, but its seed was not destroyed: lurking in the depths of our society it developed as the Restoration’s mistakes grew, and soon erupted.