François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXXII: The July Revolution 1830

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXXII: Chapter 1: The July Revolution: the 26th of July

- Book XXXII: Chapter 2: The July Revolution: the 27th of July

- Book XXXII: Chapter 3: The July Revolution: military action on the 28th of July

- Book XXXII: Chapter 4: The July Revolution: civil action on the 28th of July

- Book XXXII: Chapter 5: The July Revolution: military action on the 29th of July

- Book XXXII: Chapter 6: The July Revolution: civil action on the 29th of July – Monsieur Baude, Monsieur de Choiseul, Monsieur de Sémonville, Monsieur de Vitrolles, Monsieur Lafitte and Monsieur Thiers

- Book XXXII: Chapter 7: I write to the King at Saint-Cloud: his verbal response – The aristocratic corps – The pillage of the Missionaries’ House on Rue d’Enfer

- Book XXXII: Chapter 8: The Chamber of Deputies – Monsieur de Mortemart

- Book XXXII: Chapter 9: A trip through Paris – General Dubourg – A funeral ceremony beneath the Colonnades of the Louvre – The young men carry me to the Chamber of Peers

- Book XXXII: Chapter 10: The Meeting of Peers

- Book XXXII: Chapter 11: The Republicans – The Orléanists – Monsieur Thiers is sent to Neuilly – Another gathering of Peers at the Grand Referendary’s: the note reaches me too late

- Book XXXII: Chapter 12: Saint-Cloud – A Scene: Monsieur le Dauphin and the Duke of Ragusa

- Book XXXII: Chapter 13: Neuilly – Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans – Le Raincy – The Prince arrives in Paris

- Book XXXII: Chapter 14: A deputation of the Elective Chamber offers Monsieur le Duc d’Orleans the Lieutenant-General-ship of the Kingdom – He accepts – Republican efforts

- Book XXXII: Chapter 15: Monsieur le Duc d’Orleans goes to the Hôtel de Ville

- Book XXXII: Chapter 16: The Republicans at the Palais-Royal

Book XXXII: Chapter 1: The July Revolution: the 26th of July

BkXXXII:Chap1:Sec1

The decrees, dated the 25th of July, were published in the Moniteur on the 26th. The secret had been so well kept that neither the Marshal Duke of Ragusa, Major-General of the Guard, who was in command, nor Monsieur Mangin, Prefect of Police, were appraised of it. The Prefect for the Seine only knew of his orders via the Moniteur, as did the Under-Secretary of State for War, though it was these various leaders who had the disposition of the various armed forces. The Prince de Polignac, charged in the interim with Monsieur de Bourmont’s portfolio, was so unconcerned with this trivial business of the decrees, that he spent the 26th presiding at an award ceremony at the War Ministry.

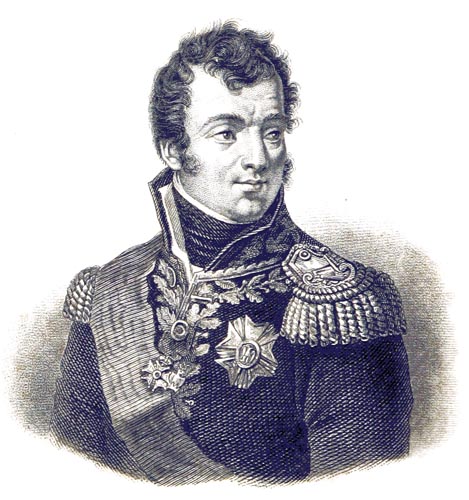

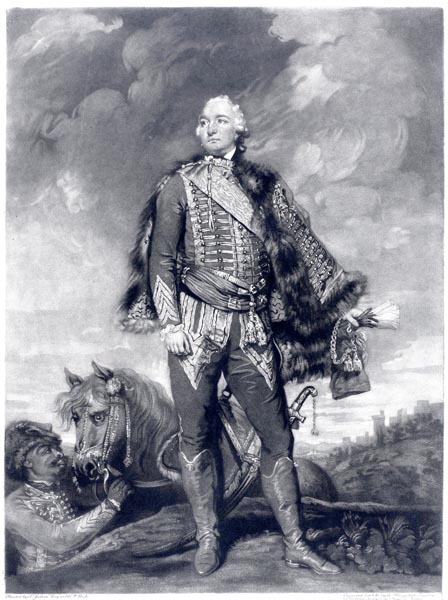

‘Marmont’

Histoire de la Révolution Française Depuis 1814 Jusqu'à 1830...Revue et Continuée par M. Auguis, Vol 01 - Jacques Antoine Dulaure (p486, 1838)

The British Library

The King left for the hunt on the 26th, before the Moniteur had arrived at Saint-Cloud, and he did not return from Rambouillet until midnight.

At last the Duke of Ragusa received word from Monsieur de Polignac:

‘Your Excellency is aware of the extraordinary measures which the King, in his wisdom and his feelings of affection for his people, has judged necessary to maintain the rights of the Crown and public order. In these vital circumstances, His Majesty counts on your zeal to ensure order and calm in the whole area under your command.’

This audacity displayed by the weakest of men, against a force which was about to crush an empire, could never be explained except as a kind of hallucination, resulting from the advice of a miserable clique who are never to be found when danger threatens. The newspaper editors, having consulted Messieurs Dupin, Odilon Barrot, Barthe, and Mérilhou, resolved to publish their papers without clearance, in order to be arrested and then plead the illegality of the decrees. They met at the offices of the National: Monsieur Thiers drafted a protest which was signed by forty-four journalists, and which appeared, on the morning of the 27th, in the National and Le Temps.

At the end of the day a handful of Deputies met at the house of Monsieur Laborde. They agreed to meet the following day at Monsieur Casimir Périer’s. There appeared, for the first time, one of the three powers which would occupy the scene: the Monarchy was located in the Chamber of Deputies, the Usurpation at the Palais-Royal, and the Republic at the Hôtel de Ville. In the evening, crowds assembled at the Palais-Royal; they threw stones at Monsieur de Polignac’s carriage. When the Duke of Ragusa saw the King at Saint-Cloud, on his return from Rambouillet, the King asked him the news from Paris: ‘Stocks are down. – By how much?’ the Dauphin asked. ‘By three francs’, the Marshal replied. ‘They will recover’, the Dauphin replied; and everyone left.

Book XXXII: Chapter 2: The July Revolution: the 27th of July

BkXXXII:Chap2:Sec1

The 27th had begun badly. The King had invested the Duke of Ragusa with command of Paris: which was tempting misfortune. At one o’clock, the Marshal installed himself in the Guard Headquarters on the Place du Carrousel. Monsieur Mangin sent men to seize the National’s presses; Monsieur Carrel resisted; Messieurs Mignet and Thiers, thinking the game was up, disappeared for two days: Monsieur Thiers went into hiding in the Montmorency Valley, at the house of a certain Madame de Courchamp, a relative of the two Messieurs Béquet, of whom one worked for the National and the other for the Journal des Débats.

At Le Temps, the thing took a more serious turn: the true journalistic hero was incontestably Monsieur Coste.

In 1823, Monsieur Coste ran Les Tabelettes universelles: accused by his collaborators of having sold the paper, he fought a duel and received a sword-thrust. Monsieur Coste was presented to me at the Foreign Ministry; speaking to him of the freedom of the Press, I said: ‘Monsieur, you know how much I love and respect that freedom; but how do you expect me to defend it to Louis XVIII when every day you attack royalty and religion! I beg you, in your own interest and to preserve my forces intact, do not sap the ramparts which are three parts demolished, and which in truth a brave man would be ashamed to attack. Let us do a deal: no longer attack a few weak old men whom the throne and the sanctuary barely protect: I will hand myself over to you in exchange. Attack me day and night; say what you will of me, I will never complain; I will thank you for your legitimate and constitutional attack on a Minister, and for keeping the King out of it.’

Monsieur Coste retained from this interview a measure of esteem for me.

A confrontation regarding the constitution took place at the office of Le Temps between Monsieur Baude and a Police commissioner.

The Attorney-General issued forty-four warrants against the signatories to the journalists’ protest.

Around two o’clock, the Revolution’s monarchist party met at Monsieur Périer’s, as they had agreed to do the day before: nothing was concluded. The Deputies adjourned the meeting till the following day, the 28th, at Monsieur Audry de Puyraveau’s house. Monsieur Casimir Périer, a man of order and means, did not wish to fall into the hands of the people; he still cherished hopes of coming to terms with the Legitimacy; he said sharply to Monsieur de Schonen: ‘You are ruining us by flouting the law; you are losing us a superb position.’ This spirit of legality ruled everywhere; it appeared during two contrasting meetings, one at Monsieur Cadet-Gassicourt’s, the other at General Gourgaud’s. Monsieur Périer belonged to that middle class which appointed itself heir to the people and the army. He had courage, and fixity of purpose; he flung himself bravely athwart the revolutionary torrent to damn it; but he was over-pre-occupied with his health and too careful of his wealth. ‘What can you do with a man,’ said Monsieur Decazes to me, ‘who is always inspecting his tongue in the mirror?’

The crowd grew and began to arm, and the Commander of the Gendarmerie came to warn the Duke of Ragusa that he had insufficient men and was fearful of being overwhelmed. The Marshal then made his military dispositions.

It was already half past four on the afternoon of the 27th, before the barracks received orders to take up arms. The Paris Gendarmerie, supported by a few Guards detachments, tried to re-open the Rue Richelieu and the Rue Saint-Honoré. One of these detachments was assailed in the Rue du Duc-de-Bordeaux (Rue du Vingt-Neuf-Jeuillet) by a shower of stones. The leader of this detachment was holding fire, when a shot rang out from the Hôtel Royal on the Rue des Pyramides, and decided the matter: it seems that a certain Mr Folks, staying at this hotel, had armed himself with his shooting-piece, and fired at the Guards from his window. The soldiers replied with a volley towards the house, and Mr Folks and two servants were killed. This is the way that these English, who live a sheltered life in their island, transport revolution elsewhere; you find them mixed up in quarrels which are no concern of theirs, in the four corners of the world: if they can sell a piece of calico what matter if it plunges a nation into endless calamities. What right had this Mr Folks to shoot at French soldiers? Had Charles X violated the British Constitution? If anything could tarnish the struggles of July it would be for them to have been started by an English bullet.

The first battles, which did not begin until about five in the afternoon of the 27th ended at dusk. The gunsmiths handed their weapons to the crowd, the street-lamps were either broken or remained unlit; the tricolour flag was hoisted in the darkness on the towers of Notre Dame: the storming of the guard-houses, the taking of the Arsenal and the powder-magazines, and the disarming of the militiamen, was completed without opposition on the morning of the 28th, and by eight everything was over.

The Revolution’s democratic and proletarian party in smocks or half-naked was under arms; it did not spare its rags and poverty. The people, represented by electors chosen from various groupings, managed to call a meeting at Monsieur Cadet-Gassicourt’s.

The party of Usurpation had not yet shown itself: its leader, hiding outside Paris, was uncertain whether to go to Saint-Cloud or the Palais-Royal. The middle-class or monarchical party, the Deputies, deliberated and refused to be drawn into the movement.

Monsieur de Polignac took himself to Saint-Cloud and at five in the morning on the 28th persuaded the King to sign the decree placing Paris under martial law.

Book XXXII: Chapter 3: The July Revolution: military action on the 28th of July

BkXXXII:Chap3:Sec1

On the 28th the crowds re-grouped in greater numbers; with the cry of ‘Long live, the Charter!’ which could still be heard, were already mingled cries of ‘Long live, Liberty! Down with the Bourbons!’ They also shouted: ‘Long Live, the Emperor! Long live, the Black Prince!’ that mysterious shadowy Prince who appears in the popular imagination in all revolutions. Memories and previous passions were forgotten; they dragged down and burnt the arms of France; they hung them from the cords of broken street-lamps; they tore the fleur-de-lis badges from the coachmen’s and postmen’s uniforms; the notaries took down their escutcheons, the bailiffs removed their badges, the carriers their official signs, the Royal suppliers their warrants. Those who had previously covered their oil-painted Napoleonic eagles with Bourbon lilies in distemper only needed a sponge to wipe out their loyalty; nowadays empires and gratitude are effaced with a little water.

The Duke of Ragusa wrote to the King saying that it was essential to bring about calm, and that by the next day, the 29th, it would be too late. A messenger from the Prefect of Police came to ask the Marshal if it was true that Paris had been placed under martial law: the Marshal, who knew nothing about it, looked surprised; he hurried to the President of the Council’s residence; there he found the Ministers gathered, and Monsieur de Polignac handed him the decree. Because the man who had trampled the world underfoot had placed cities and whole provinces under martial law, Charles X thought he could imitate him. The Ministers told the Marshal that they were about to install themselves at the Guard Headquarters.

No orders having arrived from Saint-Cloud, at nine in the morning on the 28th, when there was no longer time to retain anything, but there was time to recapture everything, the Marshal ordered the troops, who had already shown themselves the day before, from barracks. No precaution had been taken to lay in provisions at the Headquarters in the Carrousel. The storehouse, which they had forgotten to guard adequately, was taken. The Duke of Ragusa, a man of intellect and merit, a brave soldier, and a wise but unlucky general, proved for the thousandth time that military ability is insufficient to handle civil disturbance; any police officer would have had a better idea than the Marshal as to what should be done. Perhaps his thoughts were paralysed by memories; he remained as if stifled by the weight of fatality associated with his name.

The Marshal, who had only a handful of men with him, devised a plan which would have needed thirty thousand soldiers for its execution. Columns were deployed over vast distances, while one was ordered to occupy the Hôtel de Ville. The troops, having completed their operations to restore order everywhere, were to converge on the municipal building. The Carrousel became the headquarters: orders emerged from it, and information ended up there. A Swiss battalion, pivoting on the Marché des Innocents, was charged with opening communications between the forces of the centre and those which covered the circumference. The soldiers from the Popincourt Barracks prepared to descend by various routes on positions from which they could be deployed. General Latour-Mauborg was lodged in the Invalides. When he saw things were going badly, he proposed to house the regiments in Louis XIV’s edifice; he claimed he could feed them, and defy the Parisians to take it. Not for nothing had he left a limb on the Imperial field of battle, and the Borodino redoubts knew how he kept his word. But what did the courage and experience of a crippled veteran count for? They ignored his advice.

Under the command of the Comte de Saint-Chamans, the first Guards column left the Madeleine to follow the boulevards as far as the Bastille. After a few paces a squad commanded by Monsieur Sala was attacked; the Royalist officer repelled the attack in a lively manner. As they advanced, the communication posts established en route, being too weakly defended and too far apart, were isolated by the mob, and separated from one another by fallen trees and barricades. There was a bloody business at the Saint-Denis gate and at that of Saint-Martin. Monsieur de Saint-Chamans, traversing the theatre of Fieschi’s future exploits, encountered numerous groups of men and women in the Place de la Bastille. He invited them to disperse, giving them money; but they did not cease pillaging the neighbouring houses. He was forced to relinquish the attempt to reach the Hôtel de Ville by the Rue Saint-Antoine, and having crossed the Pont d’Austerlitz he regained the Carrousel from the southern boulevards. Turenne in front of the still-extant Bastille had been more fortunate on behalf of the mother of the young Louis XIV.

The column entrusted with occupying the Hôtel-de-Ville followed the Quais des Tuileries, du Louvre, and de l’École, crossed the Pont Neuf to its mid-point, took the Quai de l’Horlogue, and the Flower Market, and reached the Place de Grève by the Pont Notre-Dame. Two platoons of Guards created a diversion by making for the new suspension bridge. A battalion of the 15th Light Infantry supported the Guards, and was to leave two platoons at the Flower Market.

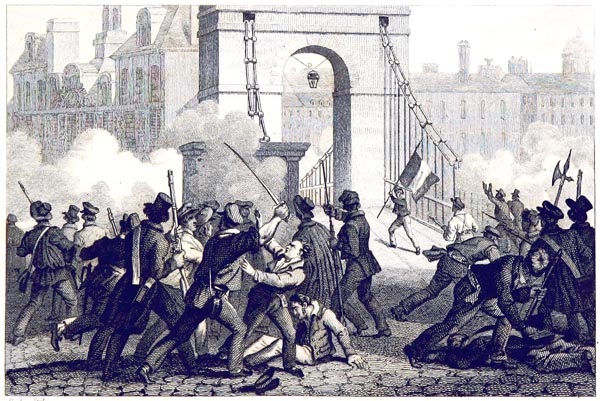

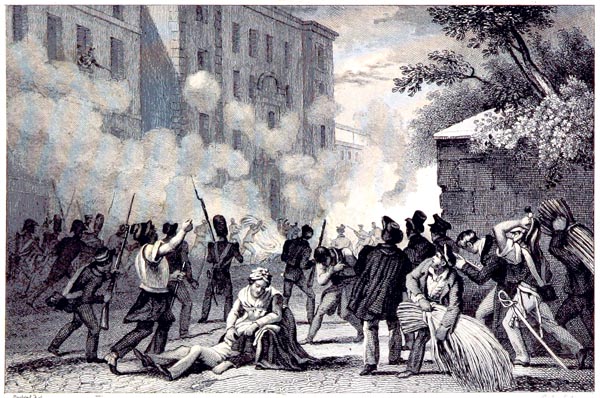

‘Dévouement du Jeune Darcole (juillet 1830)’

Histoire de la Révolution Française Depuis 1814 Jusqu'à 1830...Revue et Continuée par M. Auguis, Vol 04 - Jacques Antoine Dulaure (p1054, 1838)

The British Library

The passage of the Seine via the Pont Notre-Dame was disputed. The mob, with drums beating, faced the Guards bravely. The officer in command of the Royal Artillery pointed out to the mass of people that they were risking their lives pointlessly, and that without cannon they would be shot down without any chance of their succeeding. The crowd stood firm; the guns were fired. The soldiers streamed onto the embankments and into the Place de Grève, where two more Guards platoons joined them via the Pont d’Arcole. They had been obliged to force their way through crowds of students from the Faubourg Saint-Jacques. The Hôtel de Ville was duly occupied.

A barricade was raised at the entrance to the Rue du Mouton; a brigade of Swiss Guards carried this barricade; the people, rushing from adjacent streets, retook the position with loud cries. The barricade ultimately remained in the hands of the Guards.

In all those poor working-class districts the people fought spontaneously without ulterior motives: French recklessness, mocking, intrepid and joyful, had filled everyone’s head; for our nation, glory possesses the effervescence of Champagne. Women at the windows urged on men in the streets; notes promised a Marshal’s baton to the first Colonel who would go over to the people; crowds marched along to the sound of the violin. There were scenes of tragedy and comedy, circus-antics and triumphal displays: oaths and shouts of laughter could be heard amid musket-shots, clouds of smoke, and the dull roar of the crowd. Carriers with improvised permits signed by unknown leaders, bare-footed, and with forage-caps on their heads, drove convoys of wounded through the combatants, who parted for them.

In the wealthy districts a totally different spirit prevailed. The National Guard, having resumed the uniforms that had previously been taken from them, assembled in vast numbers at the Mairie of the 1st Arrondissement to maintain order. In encounters the Guards suffered more than the mob, being exposed to fire from enemies concealed in the houses. Others can name the drawing-room heroes who recognising various Guards officers amused themselves by shooting them down, from the safety of a shutter or a chimney-stack. In the street, animosity between workman and soldier barely went beyond striking a blow: when wounded, they helped each other. The people rescued several of their victims. Two officers, Monsieur de Goyon and Monsieur Rivaux, after a heroic defence, owed their lives to the generosity of their conquerors. A Guards captain, Kaumann, was struck on the head by an iron bar: stunned and with blood-filled eyes, he beat up with his sword the bayonets of his soldiers who were taking aim at the workman responsible.

The Guard was full of Bonaparte’s grenadiers. Several officers lost their lives, among them Lieutenant Noirot, a man of exceptional courage, who had received the cross of the Legion of Honour from Prince Eugène in 1813 for a feat of arms performed in one of the redoubts at Caldiera. Colonel de Pleinneselve, mortally wounded at the Porte Saint-Martin, had fought in the Empire’s wars in Holland and Spain, with the Grand Army and in the Imperial Guard. At the Battle of Leipzig, he captured the Austrian General von Merveldt. Carried to the hospital of Gros-Caillou by his soldiers, he refused to have his wounds dressed until last. Dr. Larrey, whose father he had known on other battlefields, amputated his leg at the thigh; it was too late to save him. Those noble adversaries who had seen so many cannonballs pass over their heads were fortunate if they avoided a bullet from one of those freed convicts whom justice has found once more, following the day of victory, in the ranks of the victors! Those galley-slaves could not defile the national Republican triumph; they have merely tarnished Louis-Philippe’s royalty. Thus there perished, obscurely, in the streets of Paris, the last of those famous soldiers who had escaped the cannon-fire at Borodino, Lützen and Leipzig: under Charles X, we massacred those brave men we had so admired under Napoleon. One victim more was missing: that man had disappeared at St Helena.

At night-fall, a junior officer in disguise brought an order for the troops at the Hôtel de Ville to fall back on the Tuileries. The retreat was made hazardous by the wounded they would not abandon, and the artillery which had to be manoeuvred with difficulty through the barricades. However it was completed without incident. When the troops returned from the various districts of Paris they expected to find the King and Dauphin standing with them: seeking in vain for a sight of the white banner on the Pavillon d’Horlogue, they expressed themselves in the vigorous language of the military camps.

It is not true, as is said, that the Hôtel de Ville had been taken from the people by the Guard, and was taken back by the people from the Guard. When the Guard arrived, they experienced no resistance, since there was no one there, even the Prefect had left. These boasts lessen and cast doubt on the real dangers. The Guard was badly deployed in winding streets; the advance, first by its stance of neutrality, and then through defection, completed the evil that the deployment, fine in theory but hardly executable in practice, had begun. The 50th of the Line arrived, during the engagement, at the Hôtel de Ville; dropping with fatigue, they hastened to withdraw within the defences of the Hotel, and gave their weary comrades their unused and useless cartridges.

The Swiss battalion still at the Marché des Innocents was extricated by a second Swiss battalion; they both ended up at the Quai de l’École, and stationed themselves at the Louvre.

Now the barricades are sanctuaries that belong to Parisian invention: they have appeared during all our disturbances, from the days of Charles V to our own.

‘The people seeing the forces deployed through the streets,’ says L’Estoile, ‘began to rouse themselves, and built barricades in the manner everyone knows of: several Swiss, who went to earth in a ditch in the square in front of Notre Dame, were killed; the Duc de Guise being on his way through the streets, whoever was there shouted: “Long live Guise!” and he, doffing his large hat, said: “My friends, enough; gentlemen, you go too far; you must shout Long live the King!”’

Why have these recent barricades of ours, whose effect has been so powerful, been so little spoken of, while the barricades of 1588, which delivered almost nothing, are so interesting to read about? Therein lies the difference in century and personalities: the sixteen century had all before it; the nineteenth has left all behind: Monsieur de Puyraveau is not Le Balafré.

Book XXXII: Chapter 4: The July Revolution: civil action on the 28th of July

BkXXXII:Chap4:Sec1

If you ignore the fighting, the civil and political revolution ran parallel to the military one. The soldiers detained at the Abbaye were set at liberty; the debtors imprisoned at Saint-Pélagie escaped, and those condemned for political errors were freed: a revolution is a jubilee; it absolves all crimes and permits greater ones.

The Ministers took council at headquarters: they decided to arrest, as the ring-leaders of the movement, Messieurs Lafitte, Lafayette, Gérard, Marchais, Salverte and Audry de Puyraveau; the Marshal gave the order; but when they were sent to him later as representatives, he thought it beneath his honour to execute his own order.

A meeting of the monarchist party composed of Peers and Deputies took place at Monsieur Guizot’s: the Duc de Broglie was there; Messieurs Thiers and Mignet, who had re-emerged, and Monsieur Carrel, though of a different opinion, arrived. It was there that the party of Usurpation pronounced the name of the Duc d’Orléans for the first time. Monsieur Theirs and Monsieur Mignet went to see General Sébastiani to talk to him about the Prince. The General replied in an evasive way; the Duc d’Orléans, he assured them, had never entertained any such ideas and had authorised nothing.

Around noon, still on the 28th, the general meeting of Deputies took place at Monsieur Audry de Puyraveau’s residence. Monsieur de Lafayette, leader of the Republican Party, had returned to Paris on the 27th; Monsieur Lafitte, leader of the Orléanist Party, did not arrive until the night of the 27th; he went to the Palais-Royal, where he found no one; he left for Neuilly: the King-in-waiting was not there.

At Monsieur de Puyraveau’s they discussed a planned protest against the decrees. This more than moderate protest evaded the main issues entirely.

Monsieur Casimir Périer advised that someone should hasten to see the Duke of Ragusa; while the five Deputies chosen to do so were getting ready to leave, Monsieur Arago was already at the Marshal’s: he had decided, following a message from Madame de Boigne, to anticipate the representatives. He suggested to the Marshal the need to put an end to the disturbances in the capital. The Duke of Ragusa went to discuss it at Monsieur de Polignac’s; the latter, informed of the troops’ reluctance, declared that if they went over to the people, they should be fired on as insurgents. General Tromelin, who was a witness to this conversation, lost his temper with General d’Ambrugeac. Then the deputation arrived. Monsieur Lafitte spoke for them: ‘We come,’ he said, ‘to ask you to stop the letting of blood. If the struggle continues, it will not only result in disastrous cruelty, but utter revolution.’ The Marshal confined himself to the question of military honour, maintaining that the people must be the first to cease fighting. He added however this postscript to a letter he wrote to the King: ‘I think it urgent that Your Majesty profit without delay from the overtures that have been made.’

The Duke of Ragusa’s aide de camp, Colonel Komierowski, escorted to the King’s office at Saint-Cloud, handed him the letter; the King said: ‘I will read the letter.’ The Colonel withdrew and awaited orders; finding that they did not arrive, he begged Monsieur le Duc de Duras to go and ask them of the King. The Duke replied that, according to etiquette, it was impossible to enter the office. At last, summoned by the King, Monsieur Komierowski was told to urge the Marshal to stand firm.

General Vincent, for his part, hastened to Saint-Cloud; having forced open the door which had been refused him, he told the King that all was lost: ‘My dear sir,’ Charles X replied, ‘you are a fine general, but you do not understand any of this.’

Book XXXII: Chapter 5: The July Revolution: military action on the 29th of July

BkXXXII:Chap5:Sec1

The 29th saw the appearance of fresh combatants: the students of the École Polytechnique, in collaboration with one of their old comrades, Monsieur Charras, forced the issue and sent four of their number, Messieurs Lothon, Berthelin, Pinsonnière and Tourneux, to offer their services to Messieurs Lafitte, Périer and Lafayette. These young men, distinguished in their studies, were already known to the Allies, when they presented themselves before Paris in 1814; during the Three Days they became popular leaders, the crowd placing them at their head with perfect trust. Some students went to the Place de l’Odéon, others to the Palais-Royal and the Tuileries.

The order of the day published on the morning of the 29th offended the Guard: it announced that the King, wishing to show his satisfaction with his brave servants, granted them a month and a half’s pay; an unseemly action which the French soldiers resented: it valued them like the English who would not march, or rebelled, if they had not received their money.

During the night of the 28th, the people had stripped the paving stones from the streets for twenty yards on either side and the next day, at day-break, four thousand barricades had been erected in Paris.

The Palais-Bourbon was guarded by troops of the Line, the Louvre by two Swiss battalions, the Rue de la Paix, the Place Vendôme, and the Rue Castiglione by the 5th and 53rd of the Line. Nearly twelve hundred infantrymen arrived from Saint-Denis, Versailles and Rueil.

The military position improved: the troops were more concentrated, and they had to cross large empty spaces to reach each other. General Exelmans, who had judged these deployments well, arrived, at eleven o’clock to place his courage and experience at the disposition of the Duke of Ragusa, while for his part General Pajol presented himself to the Deputies in order to take command of the National Guard.

The Ministers had the idea of convoking the Royal Court at the Tuileries, so far were they from understanding the needs of the moment! The Marshal urged the President of the Council to repeal the decrees. During their conversation, Monsieur de Polignac was summoned; he went out and found Monsieur Bertier, the son of the first victim sacrificed in 1789, who having crossed Paris, declared that everything was going better as far as the Royalist cause was concerned: it is a fatality that the members of that race, who were entitled to revenge, were hurled into the grave during our first troubles, and invoked in our recent misfortunes. Those misfortunes were nothing new; since 1793, Paris had grown accustomed to watch events and Kings pass by.

While, according to the Royalist reports, everything was going well, the defection of the 5th and 53rd regiments of the Line was announced, who joined forces with the people.

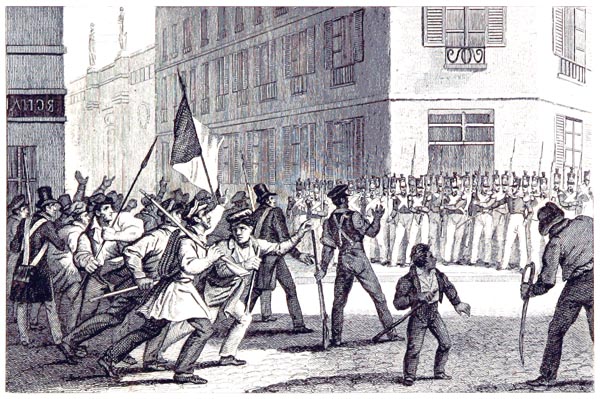

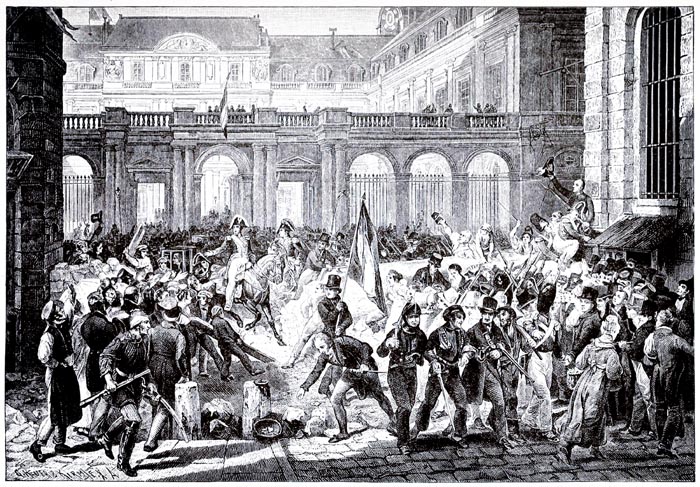

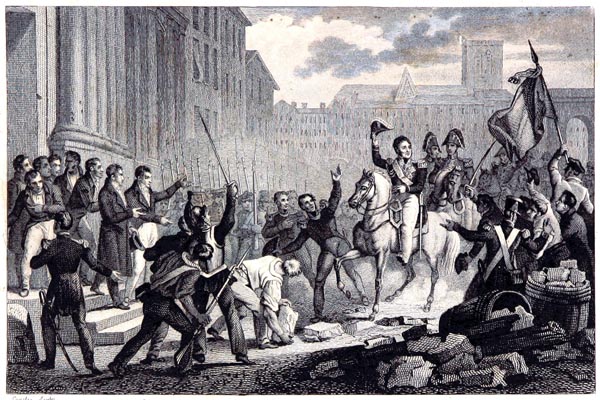

‘Le 5ème de Ligne Refuse de Tirer sur le Peuple’

Histoire de la Révolution Française Depuis 1814 Jusqu'à 1830...Revue et Continuée par M. Auguis, Vol 04 - Jacques Antoine Dulaure (p1065, 1838)

The British Library

The Duke of Ragusa proposed a suspension of the fighting: it was carried out in some places and not executed in others. The Marshal had sent for one of the two Swiss battalions stationed at the Louvre. He was sent the battalion which was garrisoning the colonnade. The Parisians, seeing the colonnade deserted, approached the walls and entered via the imitation doors which led to the inner Garden of the Infanta; they gained the crossroads and fired on the battalion stationed in the courtyard. Terrified by the memory of the 10th of August, the Swiss rushed from the palace and threw themselves among their third battalion which was situated facing the Parisians outposts, but was observing the suspension of fighting. The people, who had reached the Gallerie Musée of the Louvre, began to fire, from amidst masterpieces, on the lancers lined up in the Carrousel. The Parisians outposts, carried away by their example, broke the armistice. Driven beneath the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, the Swiss pushed the lancers into the portico of the Pavillon de l’Horlogue and emerged pell-mell into the Tuileries Garden. Young Farcy was killed in this skirmish: his name is inscribed on the corner of the café near where he fell; and a beetroot processing plant exists today at Thermopylae! The Swiss had three or four soldiers wounded or killed: this handful of dead has been portrayed as an incredible butchery.

The crowd, with Messieurs Thomas, Bastide, and Guinard entered the Tuileries by means of the wicket-gate at the Pont Royal. A tricolour flag was planted on the Pavillon de l’Horloge, as in Bonaparte’s time, apparently in memory of freedom. The furniture was torn apart, the paintings hacked by sabre blows; in the armoury the diary of the King’s hunts was found and that of the fine slaughter executed on partridges: an old custom of the royal gamekeepers. A corpse was placed on the empty throne in the Throne Room: that would be dreadful if the French, these days, were not always indulging in theatricals. The Artillery Museum, at Saint-Thomas-d’Aquine, was pillaged, and the centuries passed along the riverbank, beneath the helmet of Godfrey de Bouillon, and the lance of Francis I.

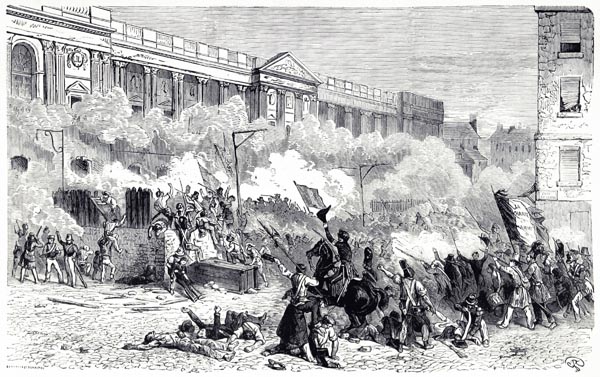

‘Révolution de 1930 - Prise du Louvre et des Tuileries’

Paris à Travers les Siècles. Histoire Nationale de Paris et des Parisiens Depuis la Fondation de Lutèce Jusqu'à Nos Jours, Vol 02 - Gourdon de Genouillac, Nicolas Jules Henri (p1239, 1879)

The British Library

Then the Duke of Ragusa quitted headquarters, leaving behind a hundred and twenty thousand francs in sacks. He left by the Rue de Rivoli and went to the Tuileries Garden. He gave the order for the troops to withdraw, first to the Champs Élysées and then as far as l’Étoile. It was thought peace had been made, and that the Dauphin was coming; several carriages from the stables, and a wagon, crossed the Place Louis XV: it was the Ministers leaving their posts.

Arriving at l’Étoile, Marmont received a letter: it announced to him that the King had appointed Monsieur le Dauphin commander-in-chief of the troops, and that he, the Marshal, was to serve under his command.

A company of the 3rd Guards Regiment had been overlooked in the house of a hatter on the Rue de Rohan; after lengthy resistance the house was taken. Captain Meunier, struck by three bullets, leapt from a third-floor window, fell onto the roof below, and was carried to the Gros-Caillou hospital: he survived. The Babylone barracks, attacked between noon and one by three students from the École Polytechnique, Vaneau, Lacroix and D’Ouvrier, was only defended by a depot of Swiss recruits about a hundred strong; Major Dufay, of French origin commanding: for thirty years he had served with us; he had been an actor in the highest dramas of the Republic and Empire. Called on to surrender, he refused to accept any conditions and shut himself in the barracks. Young Vaneau perished. Incendiaries set fire to the barrack-room doors; the door collapsed; immediately, Major Dufay emerged through this flaming maw, followed by his mountaineers with fixed bayonets; he fell to musket-fire from the keeper of an inn nearby: his death saved his Swiss recruits; they regained the various corps to which they belonged.

‘Prise de la Caserne de Babylone (juillet 1830)’

Histoire de la Révolution Française Depuis 1814 Jusqu'à 1830...Revue et Continuée par M. Auguis, Vol 04 - Jacques Antoine Dulaure (p1069, 1838)

The British Library

Book XXXII: Chapter 6: The July Revolution: civil action on the 29th of July – Monsieur Baude, Monsieur de Choiseul, Monsieur de Sémonville, Monsieur de Vitrolles, Monsieur Lafitte and Monsieur Thiers

BkXXXII:Chap6:Sec1

Monsieur le Duc de Mortemart arrived at Saint-Cloud on Wednesday the 28th, at ten in the evening, to take up his post as Captain of the Cent-Suisses: he was unable to see the King until the following day. At eleven o’clock on the 29th he made a tentative approach to Charles X urging him to repeal the decrees; the King said: ‘I do not wish to ride in a tumbril with my brother; I will not retreat a step.’ A little while later, he had retreated from a kingdom.

The Ministers arrived: Messieurs de Sémonville, d’Argout, and Vitrolles were there, Monsieur de Sémonville recounts that he had a long conversation with the King; and that he only managed to weaken his resolution by stirring his heart in speaking of the risk to Madame la Dauphine. He said: ‘Tomorrow, at noon there will no longer be a King, a Dauphin, or a Duke of Bordeaux.’ And the King replied: ‘You will surely give me till one.’ I don’t believe a word of all that. Bragging is a fault of ours: question a Frenchman and listen to his tales, he will always have done everything. The Ministers went in to see the king behind Monsieur de Sémonville; the decrees were revoked, the government dissolved, and Monsieur de Mortemart was named President of the new Council.

In the capital, the Republican Party had at last found a home. Monsieur Baude (the gentlemen involved in the struggle at the offices of Le Temps), while traversing the streets, found the Hôtel de Ville only occupied by a couple of individuals, Monsieur Dubourg and Monsieur Zimmer. He immediately claimed to be the envoy of the provisional government which was about to be installed. He called together the employees of the Prefecture; he ordered them to set to work, as if Monsieur de Chabrol were present. When government has become automatic, the wheels are soon in motion; everyone hastened to secure the empty seats: who would be secretary general, who head of division, who would make himself agreeable, who would appoint staff and distribute the staff amongst his friends; there were those who slept there in order not to be wrong-footed, and to be ready to immediately seize any position that might become vacant. Monsieur Dubourg, nicknamed the General, and Monsieur Zimmer, were deemed to be leaders of the military section of the provisional government. Monsieur Baude, representing the civil side of this previously unknown government, made the decisions and issued the proclamations. However posters emanating from the Republican Party had been seen, spelling out the formation of an alternative government, comprising Messieurs de Lafayette, Gérard and Choiseul. It is difficult to associate the last name with the other two; as Monsieur Choiseul has himself protested. That aged Liberal, who, to stay alive, had held himself stiff as a corpse, as an émigré shipwrecked at Calais, found nothing left of his paternal home, on returning to France, but a box at the Opera.

At three in the evening, there was fresh confusion. An order of the day called a meeting of the Deputies, in Paris, at the Hôtel de Ville, to confer on the measures to be adopted. The mayors were to return to their mayoralties; they were also to send one of their assistants to the Hôtel de Ville in order to form a consultative commission. This order of the day was signed: J. Baude, for the provisional government, and Colonel Zimmer, by order of General Dubourg. This audacity carried out by the three, speaking in the name of a government which only existed as advertised by themselves at the street-corners, proves the rare intelligence of the French during revolutions: men like these are clearly leaders destined to direct others. What misfortune that in delivering us from similar anarchy, Bonaparte snatched away our liberty!

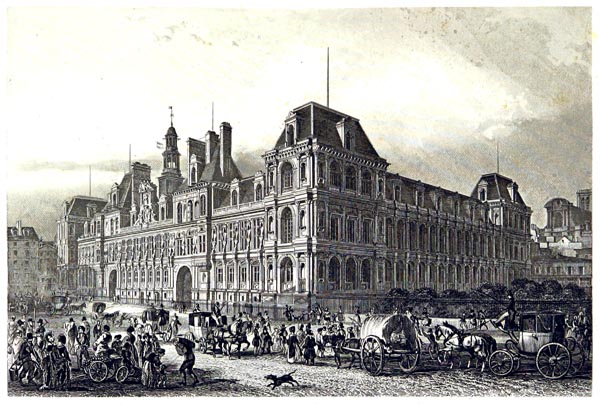

‘July 28, 1830, In Paris; Liberty Leading the People. Painting by Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix (1799-1863). (Paris, Luxembourg Palace).’

A History of all Nations From the Earliest Times; Being a Universal Historical Library - John Henry Wright (p178, 1905)

Internet Archive Book Images

The Deputies met again at Monsieur Lafitte’s. Monsieur de Lafayette, resuming where he left off in 1789, declared that he would resume command of the National Guard as well. He was applauded, and went off to the Hôtel de Ville. The Deputies appointed a municipal commission composed of five members, Messieurs Casimir Périer, Lafitte, de Lobau, de Schonen, and Audry de Puyraveau. Monsieur Odilon Barrot was elected secretary of this commission, which installed itself at the Hôtel de Ville as had Monsieur de Lafayette. All this sat awkwardly with Monsieur Dubourg’s provisional government. Monsieur Mauguin, sent on a mission to the commission, stayed there. The friend of Washington had the black flag that decorated the Hôtel de Ville, an idea of Monsieur Dubourg’s, removed. At half past eight in the evening Monsieur de Sémonville, Monsieur d’Argout and Monsieur de Vitrolles arrived from Saint-Cloud. As soon as they had learned of the repeal of the decrees at Saint-Cloud, the recall of the former Ministers, and the nomination of Monsieur de Mortmart as the President of the Council, they had hastened to Paris. They presented themselves there as representatives of the King to the Municipal Commission. Monsieur Mauguin asked the Grand Referendary if he had written credentials; the Grand Referendary replied that he had not thought to bring them. The negotiation with the official commissioners ended there.

The meeting at Monsieur Lafitte’s having learnt of what had gone on at Saint Cloud Monsieur Lafitte signed a pass for Monsieur de Mortemart, adding that the Deputies assembled at his house would wait for him until one in the morning. The noble Duke failing to arrive, the Deputies withdrew.

Monsieur Lafitte, with only Monsieur Thiers remaining, concerned himself with the Duc d’Orléans and the proclamations to be issued. Fifty years of revolution in France had provided practical people with skills in government re-organisation, and found the theorists used to drawing up charters, and preparing the tackle and cradle by means of which governments are docked, and with which they are launched.

‘Portrait of Louis Philippe, Duke of Orleans’

John Raphael Smith, Joshua Reynolds, 1762 - 1812

The Rijksmuseum

Book XXXII: Chapter 7: I write to the King at Saint-Cloud: his verbal response – The aristocratic corps – The pillage of the Missionaries’ House on Rue d’Enfer

BkXXXII:Chap7:Sec1

The day of the 29th, following my return to Paris, was not without occupation as far as I was concerned. My plans were stalled: I wished to act, but only wished to do so with orders, from the King’s own hand, granting me the necessary powers to deal with the immediate authorities; to involve myself with it all and do nothing unsuitable. I had reasoned wisely, witness the affront suffered by Messieurs d’Argout, Sémonville and Vitrolles.

I then wrote to Charles X at Saint Cloud. Monsieur de Givré agreed to deliver my letter. I begged the King to tell me his wishes. Monsieur de Givré came back empty-handed. He had handed my letter to Monsieur le Duc de Duras, who had passed it to the King, who sent the reply that he had named Monsieur de Mortemart as his First Minister, and that he invited me to meet with him. Where to find the noble Duke? I searched for him on the evening of the 29th in vain.

Repulsed by Charles X, my thoughts turned to the Chamber of Peers; it could, as a sovereign court, invoke proceedings and judge disputes. If it was unsafe to convene in Paris, it was free to move elsewhere, even to the King’s residence, and there declare a national arbitration process. It had some chance of success; there is always room for daring. After all, in succumbing, it would suffer a useful defeat where principles were concerned. But would I find a score of men in that Chamber prepared for self-sacrifice? Of those twenty, might there be four who agreed with me regarding public freedoms?

Aristocratic assemblies rule gloriously when they are a sovereign power, alone invested with its rights and machinery: they offer the strongest security; but in collaborative government, they lose their value, and are useless when major crises erupt.powerless against the King, they will not prevent despotism; powerless against the people, they will not stop anarchy. In public disturbances, they only buy their continued existence at the cost of perjury or subservience. Did the House of Lords save Charles I? Did it save Richard Cromwell, to whom it had sworn an oath? Did it save James II? Will it save the Hanoverian Princes now? Can it even save itself? A presumed aristocratic counterweight only upsets the balance and sooner or later is thrown out of the pan. An ancient and wealthy aristocracy accustomed to public business, has only one means of holding onto power when it is slipping away: that is, to pass from the Capitol to the Forum, and set itself at the head of the new movement, unless it thinks itself not strong enough to risk civil war.

‘Portrait of Charles I, King of England’

Anonymous, c. 1650

The Rijksmuseum

While I was awaiting the return of Monsieur de Givré, I was busy defending my quarter of the city. The suburbanites and quarrymen of Montrouge flowed through the Barrière d’Enfer. The latter resembled those quarrymen of Montmartre who caused such great distress to Mademoiselle de Mornay as she was fleeing the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre. Passing by the community of Missionaries situated on my street, they entered it: a score of priests were forced to save themselves: the den of fanatics was systematically pillaged, and their books and beds were burned in the street. No one spoke about this misfortune. Had they loaded themselves with whatever the propagandists had lost? I offered hospitality to seven or eight fugitives; they stayed hidden under my roof for several days. I obtained passports for them through the intermediary of my neighbour, Monsieur Arago, and they went off to preach the word of God elsewhere. ‘The flight of saints has often been useful to nations, utilis populis fuga sanctorum.’

Book XXXII: Chapter 8: The Chamber of Deputies – Monsieur de Mortemart

BkXXXII:Chap8:Sec1

The Municipal Commission, established at the Hôtel de Ville, named Baron Louis as provisional Commissioner for Finance, Monsieur Baude to the Interior, Monsieur Mérilhou to Justice, Monsieur Chardel to Postal Services, Monsieur Marchal to Telegraphic Services, Monsieur Bavoux to the Police, and Monsieur de Laborde to the Prefecture of the Seine. Thus the volunteer provisional government was in reality destroyed by Monsieur Baude’s promotion, which made him a member of the government. The shops re-opened; and public services renewed their course.

During the meeting at Monsieur Lafitte’s it had been agreed that the Deputies would assemble at noon, in the Palais de la Chambre: there they found themselves sixty or so strong, presided over by Monsieur Lafitte. Monsieur Bérard announced that he had met Messieurs d’Argout, de Forbin-Janson and de Mortemart, who had gone to Monsieur Lafitte’s, thinking to find the Deputies there; he had invited the gentlemen to follow him to the Chamber, but Monsieur le Duc de Mortemart, dropping with fatigue, had gone off to see Monsieur de Sémonville. Monsieur de Mortemart, according to Monsieur Bérard, had said that he had a free hand and that the King consented to everything.

In fact, Monsieur de Mortemart was carrying five decrees about with him: instead of communicating them to the Deputies immediately, his tiredness obliged him to return as far as the Luxembourg. At noon, he sent the decrees to Monsieur Sauvo; the latter replied that he could not publish them in the Moniteur without the authorisation of the Chamber of Deputies or the Municipal Commission.

Monsieur Bérard being in the process, as I have said, of providing an explanation to the Chamber, a discussion arose as to whether to admit Monsieur de Mortemart or no. General Sébastiani insisted on the affirmative; Monsieur Mauguin declared that if Monsieur de Mortemart were present, he would demand that he be heard, but that matters were pressing and they could not await Monsieur de Mortemart’s good pleasure.

They named five Commissioners charged with conferring with the Peers: these five Commissioners were Messieurs Augustin Périer, Sébastiani, Guizot, Benjamin Delessert and Hyde de Neuville.

But a little later the Comte de Sussy was introduced into the Elective Chamber. Monsieur de Mortemart had entrusted him with presenting the decrees to the Deputies. Addressing the Assembly he said: ‘In the absence of Monsieur the Chancellor, a small number of Peers met at my house; Monsieur le Duc de Mortemart handed us this letter, addressed to Monsieur le General Gérard or Monsieur Casimir Périer. I ask your permission to read it.’ This is the letter; ‘Monsieur, leaving Saint Cloud during the night, I have sought to meet with you in vain. Please tell me where I may find you. I beg you to give cognisance to the decrees of which I have been the bearer since yesterday.’

Monsieur le Duc de Mortemart had left Saint Cloud during the night; he had had the decrees in his pocket for twelve to fifteen hours, since yesterday, according to his statement; he had not found General Gérard or Monsieur Casimir Périer: Monsieur de Mortemart had been very unlucky! Monsieur Bérard made the following observation on the letter as communicated:

‘I cannot prevent myself,’ he said, ‘from noting here a lack of frankness: Monsieur de Mortemarte, who arrived at Monsieur Lafitte’s this morning while I was with him, told me formally that he was on his way here.’

The five decrees were read out, the first repealing the decrees of the 25th of July, the second summoning the Chambers for the 3rd of August, the third naming Monsieur de Mortemart Minister of Foreign Affairs and President of the Council, the fourth granting General Gérard the War Ministry, the fifth granting Monsieur Casimir Périer the Finance Ministry. When I finally found Monsieur de Mortemart at the residence of the Grand Referendary, he assured me that he had been forced to halt at Monsieur de Sémonville’s, because while returning on foot from Saint Cloud, he had been forced to make a detour and enter the Bois de Boulogne through a gap: his boot or shoe had blistered his heel. It is to be regretted that before producing the royal ordinances, Monsieur de Mortemart did not try to see the influential men inclined to the royal cause. The decrees suddenly emerged in front of Deputies who had not been forewarned, no one daring to declare himself. They attracted this lethal response from Benjamin Constant: ‘We know in advance what the Chamber of Peers will say, that they accept the revocation of the previous decrees purely and simply. For my part, I can make no positive pronouncement on the question of the dynasty; I will only say that it would be all too convenient for a King to open fire on his subjects and then be quit of it by claiming: He did nothing.’

Would Benjamin Constant, who could make no positive pronouncement on the matter of the dynasty, have ended his sentence in this manner if one had spoken to him beforehand in terms tailored to his talents and his own ambition? I feel sincerely sorry for a man of courage and honour like Monsieur de Mortemart, when I reflect that the Legitimacy was overthrown perhaps because the Minister entrusted with the King’s powers failed to find two Deputies in Paris, and that, wearied with covering three leagues on foot, he had a blistered heel. The decree nominating him Ambassador to St Petersburg has replaced the decrees given to Monsieur de Mortemart by his old master. Ah! Why did I refuse to become Louis-Philippe’s Foreign Minister and pursue again my deeply-beloved Rome Embassy? But, alas! What would I have made of my deeply-beloved on the banks of the Tiber? I would always have thought her gazing at me in embarrassment.

Book XXXII: Chapter 9: A trip through Paris – General Dubourg – A funeral ceremony beneath the Colonnades of the Louvre – The young men carry me to the Chamber of Peers

BkXXXII:Chap9:Sec1

On the morning of the 30th, having received a note from the Grand Referendary inviting me to the meeting of Peers, at the Luxembourg, I wanted to discover the latest news beforehand. I went through the Rue d’Enfer, to the Place Saint-Michel, and the Rue Dauphine. There was still some excitement round the damaged barricades. I compared what I saw with the great revolutionary movement of 1789, and it seemed orderly and silent to me: the difference was obvious.

On the Pont-Neuf, the statue of Henri IV, held a tricolour flag, like a standard-bearer of the League. Gazing at the bronze King, someone in the crowd said: ‘You would never have done anything so stupid, you old rascal.’ Groups of people were gathered on the Quai de l’École; in the distance I made out a general accompanied by two aides de camp all on horseback. I went in that direction. As I pushed through the crowd, I kept my eyes on the general: across his coat he wore a tricolour sash, and his hat was reversed and cocked to one side. He saw me in turn and called out: ‘Heavens, it’s the Vicomte!’ And I, with surprise, recognised Colonel or Captain Dubourg, my companion in Ghent, who on our way back to Paris had taken a succession of undefended towns in the name of Louis XVIII, and brought us half a sheep for our dinner in a hovel in Arnouville. He was the officer whom the newspapers had represented as an austere Republican soldier with a grey moustache, who had refused to serve under Imperial tyranny, and who was so poor they had been obliged to buy him a shabby uniform from the days of La Réveillère-Lepaux at an old clothes shop. And I for my part cried: ‘Why! It’s you! How come.’ He held out his arms, and shook hands with me over Flanquine’s neck; a circle formed round us: ‘My dear sir’, said the military head of the Provision Government to me in a loud voice, pointing to the Louvre, ‘there were twelve hundred of them in there: we peppered their behinds, and how they ran, how they ran!...’ Monsieur Dubourg’s aides de camp burst into hearty laughter; the crowd laughed in unison; and the General spurred his nag that caracoled like a weary animal, and was followed by two other Rosinantes, slipping on the paving stones and ready to collapse between their riders’ legs.

Thus, proudly ensconced, there parted from me that Diomedes of the Hôtel de Ville, moreover a man of courage and wit. I have seen men who, taking the events of 1830 seriously, blushed at this story, because it assailed their heroic credulity. I myself was ashamed to see the comic side of the most serious revolutions and how easily one can mock the people’s good faith.

‘Hôtel de Ville’

Histoire Physique, Civile et Morale de Paris...Quatrième Édition - Jacques Antoine Dulaure (p375, 1846)

The British Library

Monsieur Louis Blanc, in the first volume of his excellent Histoire de dix ans, published after the material I have just written, confirms my tale: ‘A man,’ he says, ‘in a General’s uniform, of medium height, with an expressive face, was crossing the Marché des Innocents, followed by a considerable number of armed men. It was from Monsieur Évariste Dumoulin, journalist on the Constitutionnel, that this individual had received his uniform, taken from an old-clothes shop; and the epaulets he wore had been given to him by Perlet the actor: they came from the property-room of the Opéra-Comique. ‘Who is that General?’ everyone asked. And when those around him replied: ‘It is General Dubourg’, the crowd who had never heard his name before cried: ‘Long live, General Dubourg!’ (I received a letter, on the 9th of January of this year, 1841, from Monsieur Dubourg: which contained the following: ‘How I have longed to see you again since our meeting on the Quai du Louvre! How often I have wished to pour into your heart the sorrows which lacerate my soul! How wretched it is to love one’s country, honour, goodness, glory, with passion when one lives at such a time! . Was I wrong, in 1830, to refuse to submit to what was being enacted? I clearly saw the odious future they were preparing for France; I explained how only evil could come from such fraudulent political structures: but no one understood me.’ On the 5th of July of that same year 1841, Monsieur Dubourg wrote to me again to send me the draft of a letter which he wrote to Messieurs de Martignac and de Caux urging them to admit me to the Council. I have not set down anything about Monsieur Dubourg, then, which is not of the highest verity. Note: Paris, 1841)

A little further on, another sight met my eyes: a ditch had been dug in front of the Colonnade of the Louvre; a priest, in surplice and stole, was praying beside the ditch: the dead were being laid to rest there. I took off my hat and made the sign of the cross. The crowd watched this ceremony, which would have meant nothing if religion had not appeared in it, in respectful silence. So many thoughts and memories came to mind that I remained in a state of immobility. Suddenly I felt the crowd around me; someone shouted: Long live, the defender of Press freedom!’ I had been recognised by the way my hair was dressed. Some young men immediately grasped me, saying: ‘Where are you going, we’ll carry you there?’ I had no idea what to answer; I thanked them: I struggled: I begged them to let me go. The time fixed for the meeting in the Chamber of Peers had not yet arrived. The young men continued shouting: ‘Where are you going? Where are you going?’ I replied at random: ‘All right then, to the Palais-Royal!’ I was immediately escorted there to shouts of: ‘Long live, the Charter! Long live, the liberty of the Press! Long live, Chateaubriand!’ In the Cour des Fontaines, Monsieur Barba, the bookseller, emerged from his house to embrace me.

We arrived at the Palais-Royal; I was bundled into a café, and under its wooden arcade. I was dying from the heat. I reiterated my plea for remission of glory, with clasped hands: no result: the young people refused to let me go. There was a man in the crowd wearing a jacket with turned-up sleeves, with dirty hands, a sinister face, and burning eyes, the sort I had often seen at the start of the Revolution: He was continually trying to approach me, and the young men kept pushing him away. I learnt neither his name nor what he wished of me.

In the end I was forced to say I was going to the Chamber of Peers. We left the café; the cheering recommenced. In the courtyard of the Louvre various cries rang out: some shouted: ‘To the Tuileries! To the Tuileries!’ others; ‘Long live, the First Consul!’ apparently wishing to make me heir to the Republican, Bonaparte. Hyacinthe, who was with me, received his own share of handshakes and embraces. We crossed the Pont des Arts and went along the Rue de Seine. People rushed to see us go by; they crowded the windows. I found all these honours painful, as my arms were being pulled from their sockets. One of the young men pushing me on from behind suddenly put his head between my legs and lifted me onto his shoulders. Fresh cheering; they called out to the spectators in the street and at the windows: ‘Hats off! Long live, the Charter’ and I replied: ‘Yes Gentlemen, long live the Charter, but above all long live the King!’ My cry was not repeated, but it failed to provoke any anger. And that is how the game was lost! Everything could still have been arranged, but it was essential only to present popular men to the people: in revolutions, fame achieves more than an army.

I implored my young friends so feelingly that they at last set me down. In the Rue de Seine, opposite Monsieur Lenormant’s, my publisher’s, an upholsterer offered me an armchair to be carried in; I refused it, and arrived in triumph in the courtyard of the Luxembourg. My generous escort then left me having uttered fresh cries of: ‘Long live, the Charter! Long live, Chateaubriand!’ I was touched by the sentiments of these noble youths: I had shouted: ‘Long live, the King!’ amongst them, as safely as if I had been in my own house; they knew my opinions; they themselves carried me to the Chamber of Peers where they supposed I was going to speak, while yet remaining loyal to my King; and yet it was the 30th of July, and we had just passed close by the ditch where citizens, killed by the bullets fired by Charles X’s soldiers, were being buried.

Book XXXII: Chapter 10: The Meeting of Peers

BkXXXII:Chap10:Sec1

The noise I left behind me contrasted with the silence which reigned in the vestibule of the Luxembourg Palace. That silence increased in the dark gallery which led to Monsieur de Sémonville’s rooms. My presence disturbed the twenty five to thirty Peers who were gathered there: I stifled the mild effusions of fear, the tender consternation which they evinced. There I finally met with Monsieur de Mortemart. I told him that, in agreement with the King’s wishes, I was ready to work with him. He replied, as I have already mentioned, that while returning he had blistered his heel: he went back to join the main assembly. He made known to us the decrees he had communicated to the Deputies via Monsieur de Sussy. Monsieur de Broglie declared he had just crossed Paris; that we were sitting on a volcano; that the employers could not restrain their workers; that if Charles X’s name was even pronounced, they would cut all our throats, and would demolish the Luxembourg as they had the Bastille: ‘It’s true! It’s true!’ the prudent ones murmured in a low voice nodding their heads. Monsieur de Caraman, who had been made a Duke, apparently because he had been Prince von Metternich’s lackey, maintained heatedly that the decrees could not be acknowledged: ‘Why not, Monsieur?’ I asked him. That calm question froze his eloquence.

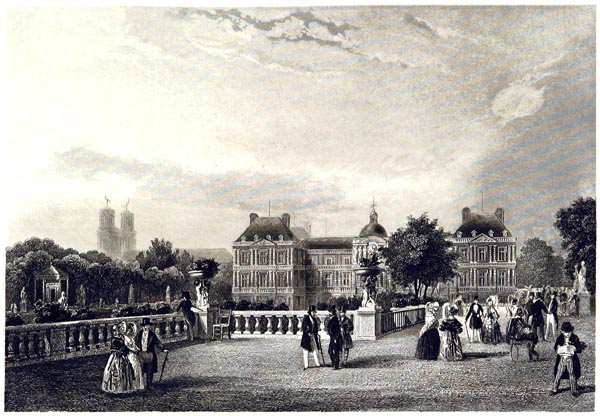

‘Palais du Luxembourg’

Histoire Physique, Civile et Morale de Paris...Quatrième Édition - Jacques Antoine Dulaure (p521, 1846)

The British Library

The five Deputy Commissioners arrived. General Sébastiani began with his usual phrase: ‘Gentlemen, it’s a serious matter.’ Then he eulogised Monsieur le Duc de Mortemart’s noble moderation; he spoke of the danger to Paris, pronounced a few words in praise of His Royal Highness Monseigneur le Duc d’Orléans, and concluded with the impossibility of considering the decrees. I and Monsieur Hyde de Neuville were the only Peers of a contrary opinion. I was allowed to speak: ‘Gentlemen, Monsieur le Duc de Broglie, has told us, that he has walked through the streets, and that he has seen hostile demonstrations everywhere: I also have traversed Paris, three thousand young people escorted me to the courtyard of this palace: you may have heard their shouts: are they, who thus saluted one of your colleagues, thirsting for your blood? They were shouting: ‘Long live, the Charter!’ I replied: ‘Long live, the King!’ They showed no anger and have deposited me amongst you safe and sound. Is this evidence of public opinion so threatening? I maintain, myself, that nothing is lost, that we can accept the decrees. The question is not one of considering whether there is any danger or no, but of keeping the oaths we have taken to that King from whom we derive our dignity and some among us their fortunes. His Majesty, in withdrawing his decrees and replacing his government, has done everything that he should: let us in turn do as we should. What? In the course of our whole lives a single day presents itself on which we are obliged to enter the field of battle, and shall we refuse to fight? Let us show France an example of loyalty and honour; let us prevent her falling into a state of anarchy, in which peace, her true interests and her liberty would be lost: danger vanishes when one dares to look it in the face.’

No one replied; they hastened to close the session. There was an impatience, amongst that gathering, to perjure themselves which made fear intrepid; all wished to preserve their scrap of life, as if time was not about to tear off our old skins, tomorrow, for which a sensible broker would not give a brass farthing.

Book XXXII: Chapter 11: The Republicans – The Orléanists – Monsieur Thiers is sent to Neuilly – Another gathering of Peers at the Grand Referendary’s: the note reaches me too late

BkXXXII:Chap11:Sec1

The three parties began to organise themselves and act against one another: the Deputies who supported a monarchy of the elder branch were the strongest legally; all who were for order rallied to their cause; but, morally, they were the weakest: they hesitated, they failed to take decisions: it became obvious, through the Court’s tergiversation, that they would accept a usurpation rather than see themselves swallowed up by the Republicans.

The latter had a placard designed which read; ‘France is free. She accords to the provisional government only the right to consult her, while waiting for her will to be expressed in fresh elections. No more royalty: Executive power entrusted to a temporary President: Direct or indirect involvement of all citizens in the election of Deputies: Freedom of religion.’

This placard summarised the only valid element of Republican opinion; a fresh assembly of Deputies would have decided whether it was good or bad to cede to that wish, no more royalty; everyone could have made their case, and the election of a new government by a National Congress would have possessed the character of legality.

On another Republican poster of that same day, the 30th of July, you could read in large letters: ‘No more Bourbons. That is the key to greatness, peace, public prosperity, liberty.’

At length an address appeared from the members of the Municipal Commission composing a provisional government; it demanded: ‘That no proclamation be issued naming a leader, while the very form of government was not yet determined; and that the provisional government would remain in operation until the wishes of the majority of the French people were known; all other measures being untimely and unacceptable.’

This address emanating from members of a commission nominated by a large number of citizens, from the various districts of Paris, was signed by Messieurs Chevalier, as President, Trélat, Teste, Lepelletier, Guinard, Hingray, Cauchois-Lemaire, etc.

In this popular meeting, it was proposed, by acclamation, to turn the presidency of the Republic over to Monsieur de Lafayette; they relied on the principles that the representative Chamber of 1815 had proclaimed on dissolution. Various printers refused to publish these proclamations, saying they had been forbidden to do so by Monsieur le Duc de Broglie. The Republic brought to earth Charles X’s throne; it feared the interdictions of Monsieur de Broglie, who was spineless.

I have told you that, on the night of the 29th, Monsieur Lafitte with Messieurs Thiers and Mignet, were all set to draw public attention to Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans. On the 30th appeared proclamations and addresses, the fruits of those discussions: ‘Let us avoid a Republic,’ they said. Then came references to the feats of arms at Jemmapes and Valmy, and they assured us that Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans was no Capet, but a Valois.

However when Monsieur Thiers, sent by Monsieur Lafitte, rode to Neuilly with Monsieur Scheffer, His Royal Highness was not there. There was a flurry of words between Mademoiselle d’Orléans and Monsieur Thiers: it was agreed that they should write to Monsieur le Duc d’Orleans to persuade him to rally to the Revolution. Monsieur Thiers wrote a note to the Prince himself, and Madame Adélaïde promised to pre-empt his family in Paris. Orléanism had made progress, and from the evening of that very day the question of conferring the powers of Lieutenant-General on Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans was discussed.

Monsieur de Sussy, with the decrees from Saint-Cloud, had been even less well-received at the Hôtel de Ville than in the Chamber of Deputies. Furnished with a receipt by Monsieur de Lafayette, he sought out Monsieur de Mortemart who cried: ‘You have done more than save my life; you have saved my honour.’

The Municipal Commission issued a proclamation in which it declared that the crimes of his reign (Charles X) were over, and that the people would have a government that owed its origin to itself (the people): an ambiguous phrase that one could interpret as one wished. Messieurs Lafitte and Périer did not sign this act. Monsieur de Lafayette, somewhat late in his alarm at the idea of an Orléanist monarchy, sent Monsieur Odilon Barrot to the Chamber of Deputies to announce that the people, the authors of the July revolution, would not agree to it ending in a simple change of leader, and that the blood spilt merited some display of liberty. There was a question of a proclamation by the Deputies inviting His Royal Highness the Duke of Orléans to return to the capital; after communicating with the Hôtel de Ville, this idea of a proclamation was abandoned. They drew lots nevertheless to select a deputation of twelve members to go and offer the Lord of Neuilly the Lieutenant-General-ship which had not found its way into a proclamation.

In the evening, the Grand Referendary gathered the Peers together at his residence; his letter through negligence or political expediency reached me too late. I hastened to make the rendezvous; they opened the gate in the Allée de l’Observatoire for me; I crossed the Luxembourg Gardens; when I arrived at the Palace, I found no one there. I made my way back among the flowerbeds my eyes fixed on the moon. I thought with regret of the mountains and seas where she had appeared to me, the forests in whose summits she concealed herself in silence, with the aspect of one repeating to me Epicurus’ maxim: ‘Hide your life.’

Book XXXII: Chapter 12: Saint-Cloud – A Scene: Monsieur le Dauphin and the Duke of Ragusa

BkXXXII:Chap12:Sec1

I left the troops, on the 29th, falling back on Saint-Cloud. The bourgeois of Chaillot and Passy attacked them, killed a captain of carabineers, and two officers, and wounded a dozen soldiers. Lemotheux, the captain of the guard, was struck by a shot from a child whom he chose to spare. This captain had given in his resignation at the time when the decrees were published; but, seeing the fighting on the 27th, he rejoined his corps to share in his comrades’ danger. Never, to the glory of France, has there been a nobler contest of opposing parties between liberty and honour.

The children, bold because they were unaware of danger, played a melancholy role during the Three Days: sheltering behind their youth, they fired at point-blank range on the officers who would have considered themselves dishonourable in firing back. Modern weapons place death at the disposal of the weakest of hands. Ugly and sickly monkeys, libertines before possessing the power to be so, cruel and perverse, those little heroes of the Three Days gave themselves over to assassination with all the abandon of innocence. Let us beware, through imprudent praise, of generating the emulation of evil. The children of Sparta went out hunting Helots.

Monsieur le Dauphin received the soldiers at the gate of the village of Boulogne, in the woods, then he returned to Saint-Cloud.

Saint-Cloud was guarded by four companies of Bodyguards. A battalion of students from Saint-Cyr had arrived: out of rivalry, and in contrast to the École Polytechnique, they had embraced the Royal cause. The exhausted troops, returning from a three day battle, wounded as they were and in a sorry state, spoke of nothing but their astonishment at the titled, gilded and sated domestics who ate at the King’s table. No one thought of cutting the telegraph lines; couriers, travellers, mail-coaches and carriages passed freely on the roads, showing the tricolour flag which stirred the villages they traversed to insurrection. Attempts to bribe the soldiers to desert, by means of money and women, began. The proclamations of the Paris Commune were hawked here and there. The King and his Court did not wish to be persuaded that they were yet in danger. In order to show that they scorned the actions of a few mutinous bourgeois, and that there was no Revolution, they allowed everything to continue: the hand of God was visible in it all.

‘View of the Park and the Castle of Saint-Cloud’

Louis Rolland Trinquesse, 1787

The Rijksmuseum

At nightfall on July 30th, about the same hour that the commission of Deputies was leaving for Neuilly, an aide, a major, announced to the troops that the decrees had been repealed. The soldiers shouted: ‘Long live, the King!’ and went cheerfully to their quarters; but this announcement of the aide’s, initiated by the Duke of Ragusa, had not been communicated to the Dauphin, who a great amateur disciplinarian, entered in a rage. The King said to the Marshal: ‘The Dauphin is unhappy: go and explain to him.’

The Marshal could not find the Dauphin at his residence, and waited for him in the billiard-room with the Duc de Guiche and the Duc de Ventadour, aides de camp to the Prince. The Dauphin re-appeared: seeing the Marshal he reddened to the eyes, crossed his ante-chamber with those giant strides of his, which were so singular, arrived at his salon and said to the Marshal: ‘Enter!’ The door closed once more: a great row could be heard; the volume of his voice increased; the Duc de Ventadour, anxiously opened the door; the Marshal emerged, pursued by the Dauphin, who called him doubly traitorous. ‘Give me your sword! Give me your sword!’ and, throwing himself upon him, wrested away his sword. The Marshal’s aide de camp, Monsieur Delarue, wanted to intervene between him and the Dauphin, but was restrained by Monsieur de Montgascon; the Prince tried hard to break the Marshal’s sword and cut his hands. He shouted: ‘To me, Bodyguards! Arrest him!’ The Bodyguards rushed in; if the Marshal had not moved his head, their bayonets would have touched his face. The Duke of Ragusa was led to his apartment, under arrest.

The King resolved the matter as best he could, it being all the more regrettable in that the participants inspired no great interest. When Le Balafré’s son killed Saint-Pol, Marshal of the League, that sword blow evidenced the pride and race of the Guise; but when Monsieur le Dauphin, a more powerful lord than a Prince of Lorraine, wished to cleave Marshal Marmont in two, what did that signify? If the Marshal had killed Monsieur le Dauphin, it would only have been a little strange. Caesar, the descendant of Venus, and Brutus, great-nephew of Junius, might pass in the street and no one would notice. Nothing is great these days, because nothing is noble.

That is how the monarchy’s last hour was spent at Saint-Cloud: that pallid monarchy, disfigured and blood-stained, resembled the portrait d’Urfé paints for us of a great person dying: ‘His eyes were wild and sunken; the lower jaw, clothed only by a little skin, seemed to have shrunken; the beard bristling, the complexion yellow, the gaze wandering, the breath laboured. From his mouth there now no longer issued human words, but oracles.’

Book XXXII: Chapter 13: Neuilly – Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans – Le Raincy – The Prince arrives in Paris

BkXXXII:Chap13:Sec1

Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans had the desire, throughout his life, that all high-born spirits have for power. That desire varies according to character: impetuous and aspiring, or weak and insidious; imprudent, overt, assertive in some, circumspect, hidden, bashful and humble in others: one, in order to rise, may indulge in every crime; another, to climb, may descend to any baseness. Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans belonged to the latter class of ambitious men. Examine this Prince’s life, and he never says or does anything fully, always leaving the door open to evasion. During the Restoration, he flatters the Court and encourages liberal opinion; Neuilly is a rendezvous for dissatisfaction and malcontents. They sigh, they shakes hands while raising their eyes to the heavens, but fail to pronounce a single word important enough to be mentioned in high places. If a member of the opposition dies, they add their carriage to the procession, but the carriage is empty; their livery is admitted at every door and grave. If, at the time of my disgrace at Court, I find myself on the same path as Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans at the Tuileries, and he has to salute me from the right-hand side in passing, I being on the left, he does it in such a manner as to turn his shoulder away. It will be noticed, and it is sufficient.

Did Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans know about the July decrees in advance? Was he told by someone who had the secret from Monsieur Ouvrard? What did he think? What were his hopes and fears? Had he conceived a plan? Did he urge Monsieur Lafitte to do what he did, or merely allow him to do so? From Louis-Philippe’s character one would assume that he made no decisions, and his political timidity, shrouded in duplicity, waited on events as a spider waits for a fly to be caught in its web. He allowed the moment to conspire; he himself only conspired in his desires, which he probably feared.

Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans had two courses of action open to him: the first, and most honourable, was to hasten to Saint-Cloud, and interpose himself between Charles X and the nation, in order to save the Crown for the one, and liberty for the other; the second was to hurl himself onto the barricades, tricolour flag in hand, and place himself at the head of the popular movement. Philippe had a choice between being an honest man and a great man: he preferred to conjure away the King’s crown and the people’s liberty. A criminal, during the disturbance and misfortune of a fire, will quietly rob the burning palace of its most precious contents, without hearing the cries of a child surprised in its cradle by the flames.

Once the rich prize had been trapped, it was necessary to set the dogs on the quarry: then all the old corruptions of previous regimes appeared, those receivers of stolen goods, foul toads half-crushed, on which one has stamped a hundred times, and which live on, flattened though they may be. Yet these are the men they praise, whose cleverness is lauded! Milton thought otherwise when he wrote this passage from a sublime letter: ‘Whatever the Deity may have bestowed upon me in other respects, he has certainly inspired me, if any ever were inspired, with a passion for the good and the beautiful. Hence, I feel an irresistible impulse to cultivate the friendship of him, who, despising the prejudiced and false conceptions of the vulgar, dares to think, to speak, and to be that which the highest wisdom has in every age taught to be the best. But if my disposition or my destiny were such that I could without any conflict or any toil emerge to the highest pitch of distinction and of praise; there would nevertheless be no prohibition, either human or divine, against my constantly cherishing and revering those, who have either obtained the same degree of glory, or are successfully labouring to obtain it.’

Charles X’s blinkered mind never knew where it was or who it was dealing with: they could have summoned Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans to Saint-Cloud, and it is probable that in the heat of the moment he would have obeyed; they could have removed him from Neuilly on the day of the decrees: they took neither course.

On being given the information Madame de Bondy carried to him at Neuilly on the night of Tuesday the 27th, Louis Philippe rose at three in the morning, and withdrew to a location known only to his family. He had the dual fear of being affected by the insurrection in Paris or arrested by a Guards captain. So he went off to listen, in Raincy’s solitude, to the sound of distant cannon fire from the fighting at the Louvre, as I, beneath a tree, had listened to that of the battle of Waterloo. The feelings which no doubt agitated the Prince would scarcely have resembled those which oppressed me in the Ghent countryside.