François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXXI: Paris, The Road to Rome, Resignation 1829

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXXI: Chapter 1: Return to Paris from Rome – My plans – The King and his arrangements – Monsieur Portalis – Monsieur de Martignac – Departure for Rome – The Pyrenees – Adventure

- Book XXXI: Chapter 2: Polignac’s Ministry – My dismay – I return to Paris

- Book XXXI: Chapter 3: Interview with Monsieur Polignac – I resign from the Rome Embassy

- Book XXXI: Chapter 4: Journalistic sycophancy

- Book XXXI: Chapter 5: Monsieur de Polignac’s first Cabinet

- Book XXXI: Chapter 6: The Expedition to Algiers

- Book XXXI: Chapter 7: The opening of the Session of 1830 – The speech – The Chamber is dissolved

- Book XXXI: Chapter 8: The new Chamber – I leave for Dieppe – The decrees of the 25th of July – I return to Paris – Reflections on the way – A letter to Madame Récamier

Book XXXI: Chapter 1: Return to Paris from Rome – My plans – The King and his arrangements – Monsieur Portalis – Monsieur de Martignac – Departure for Rome – The Pyrenees – Adventure

BkXXXI:Chap1:Sec1

Paris, August and September 1830, Rue d’Enfer

I took great pleasure in seeing my friends once more; I dreamt only of the pleasure of carrying them off with me, and ending my days in Rome. I had written to reassure myself regarding the little Caffarelli Palace on the Capitoline which I hoped to rent, and the cell which I had applied for at Sant’ Onofrio. I bought English horses and sent them off to the prairies of Evander. I had already said my farewells to my homeland, in my thoughts, with a joy that deserved to be punished. When one has voyaged in one’s youth and spent many years away from one’s country, one is accustomed to seeing one’s grave everywhere: traversing the seas of Greece, it seemed to me that the monuments on all the promontories I saw were hostelries where a bed was awaiting me.

I went to pay my court to the King at Saint-Cloud: he asked me when I was returning to Rome. He was convinced that I had a kind heart but poor judgement. The fact is that I am precisely the opposite of what Charles X thought me: I have a very cool and sound mind, but a questionable heart as far as nine-tenths of mankind are concerned.

‘Charles X’

La Révolution de 1830, 27-28-29 Juillet. D'Après Gervinus - Georg Gottfried Gervinus (p14, 1897)

The British Library

I found the King in a very bad mood with regard to his Ministry: he allowed it to be attacked by certain royalist journalists, or rather, when the editors of their papers went to ask him if he found them overly hostile, he said: ‘No, no, carry on.’ When Monsieur de Martignac had spoken: ‘Well,’ said Charles X, ‘have you listened to our Pasta.’ Monsieur Hyde de Neuville’s liberal opinions were antipathetic to him; he found a greater readiness to oblige in Monsieur Portalis, the Federalist, who revealed his greed in his face: it is to Monsieur Portalis that France owes its misfortunes. When I saw him at Passy, I was aware of what I had partly guessed: the Keeper of the Seals, while claiming to hold the Foreign Ministry only for the interim, was dying to retain it, even though he had been granted the position of President of the Court of Cassation. When it came to the question of the King disposing of the Foreign Ministry, he stated: ‘I do not say Chateaubriand will not be my Minister; I only say not yet.’ The Prince de Laval had refused it; Monsieur de La Ferronays could no longer turn in a consistent performance. In the hope that weary of conflict the portfolio would remain with him, Monsieur Portalis did nothing to help the King decide.

Filled with thoughts of the delights of Rome still to come, I allowed myself to drift, without sounding out the future; it suited me for Monsieur Portalis to look after the interim under cover of which my political situation remained unchanged. I never considered for a moment that Monsieur de Polignac might be invested with power: his narrow opinions, ardent and fixed, his unpopular and fateful name, his obstinacy, his religious opinions exalted almost to fanaticism, seemed to me reasons for continuing to neglect him. He had, it is true, suffered on behalf of the King; but he had been largely recompensed by his master’s friendship and the important London Embassy which I had granted him during my Ministry, despite Monsieur de Villèle’s opposition.

Not one of the Ministers I found in place in Paris, with the exception of Monsieur Hyde de Neuville, pleased me: I felt a lack of ability in them which caused me anxiety while they remained in power. Monsieur de Martignac, with a pleasing talent for speech, had a soft and gentle voice like that of a man to whom the women have lent something of their seductiveness and frailty! Pythagoras remembered having been a delightful courtesan named Alcea. Abbé Sieyès’ former Secretary to the Embassy also possessed a restrained arrogance, a cool mind with a trace of envy. In 1823, I had sent him to Spain in a significant and independent capacity, but he wanted to be Ambassador. He was upset at not receiving a post which he believed was worthy of him.

‘Sieyès’

Bernadotte, the first phase, 1763-1799 - Sir Dunbar Plunket Barton (p484, 1914)

Internet Archive Book Images

My likes and dislikes were of little consequence. The Chamber committed an error in toppling a government it should have preserved at all costs. That moderate ministry served as a rail above the abyss; it was easy to overthrow it, since it stood for nothing and the King was inimical towards it; all the more reason for not picking a quarrel with those men, and for granting them a majority with the aid of which they might have survived and given way one day, barring accident, to a stronger government. In France, they know nothing about patience; they have a horror of everything that has the semblance of power, until they possess it. Moreover, Monsieur de Martignac has nobly refuted accusations of weakness by spending the rest of his life courageously defending Monsieur de Polignac. My feet itched in Paris; I could not get used to the grey and melancholy skies of France, my fatherland; what then would I have thought of the skies of Brittany, my motherland, as the Greeks have it? But there, at least, there are sea breezes and calms: Tumidis albens fluctibus or venti posuere: whitening with swelling waves or the winds dying down. I gave orders to have changes and additions made to my house and garden in the Rue d’Enfer, necessary in order that at my death a finer house could be left, as a legacy, to Madame de Chateaubriand’s Infirmary. I intended the property as a retreat for artists and men of letters who were suffering from illness. I gazed at the pale sun and said to it: ‘I will go soon, and find your brighter face once more, and we will not part again.’

BkXXXI:Chap1:Sec2

Having taken leave of the King, and hoping to rid him forever of my presence, I entered a calash, and went first to the Pyrenees to take the waters at Cauterets; from there, crossing Languedoc and Provence, I would reach Nice and rejoin Madame de Chateaubriand. We passed along the Corniche together, and arrived at the Eternal City which we traversed without stopping, and after two months at Naples, Tasso’s cradle, we returned to his tomb in Rome. That is the only moment of my life in which I have been completely happy, of which I asked nothing more, in which my existence was complete, from which I saw only a line of peaceful days extending to my last hour. I was reaching harbour; I was entering it under full sail like Palinurus: inopia quies: suddenly drowsy.

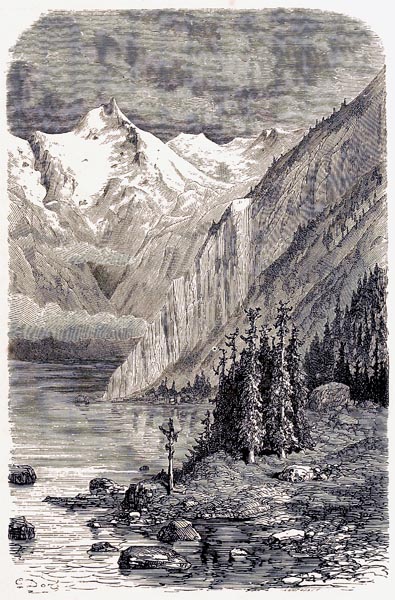

‘The Lake of Gaube’

A Tour Through the Pyrenees - Hippolyte Taine, John Safford Fiske, Gustave Dore (p316, 1875)

Internet Archive Book Images

My whole journey to the Pyrenees was a series of dreams: I stopped when I wished; my route followed the chronicles of the Middle Ages which it evoked everywhere; in Berry I saw those little hedged lanes which the author of Valentine likens to the trains of dresses, and which recalled Brittany. Richard the Lionheart was slain at Chalus, at the foot of the tower: ‘Peace there, Muslim child! Richard the King is here!’ At Limoges, I doffed my hat, in respect, to Molière; at Périgeux, the partridges in their earthenware tombs no longer uttered varying cries as in Aristotle’s day. I met my old friend Clausel de Cousserges there; he brought with him some written reminisces of my life. At Bergerac, I might have gazed at Cyrano’s nose without being obliged to fight that Guards Cadet: I left him in his own dust with those gods whom man created, who did not create man.

At Auch, I admired the choir-stalls carved according to designs made in Rome, in the great era of artistic achievement. D’Ossat, a predecessor of mine at the Court of St Peter, was born near Auch. The sun already resembled the suns of Italy. At Tarbes, I would have liked to lodge at the Star where Froissart stayed with Messire Espaing de Lyon, ‘a valiant man, a fine and knowledgeable knight’, and where he found ‘excellent hay, good oats, and a lovely river.’

When the Pyrenees appeared on the horizon, my heart quickened: from the depths of twenty-three years emerged memories embellished by those reaches of time: when, on the far side of the range, I discovered the summit of these same mountains, I recalled Palestine and Spain. I am of Madame de Motteville’s opinion; I think that Urgande la Déconnue lived in one of those castles in the Pyrenees. The past is like a museum of antiquities; one tours the vanished hours; everyone finds their own there. One day, walking in a deserted church, I heard footsteps crossing the paving stones, like those of an old man seeking his tomb. I looked around and saw no one; it was I who had been revealed to my own self.

The happier I was in Cauterets, the more the melancholy of what was past charmed me. The narrow, constrained valley is enlivened by a mountain stream; beyond the town and its mineral springs, it divides into two defiles of which one, famous for its beauty spots, ends in glaciers and the bridge into Spain. I took plenty of baths; I completed long walks alone, imagining myself on the heights of the Sabine Hills. I made every effort to be sad and failed. I composed verses about the Pyrenees; I wrote:

‘I’ve seen the waters flee from Athens and Jerusalem,

Seen the shifting sands of Nile and of Ascalon,

Carthage abandoned, with its harbour whitening:

While the gentle breeze of evening filled my sail,

and Venus’ starlight pale

Moist pearl with sunset’s purest gold was mingling.

Seated by the mast of my vessel built for speed,

My eyes sought from afar the Pillars of Hercules,

Where two angry Neptunes brandish their tridents.

Reaching the edge of Hesperia’s ancient shores

Mystery opened wide the doors

Of palaces, of the noble Abencerage, enchanted.

Like a fledgling bee that within the rose has toiled,

My Muse returned again, with her wealth of spoils,

Gathering the finest memories from the flower:

In mountains that Roland cleft by his brilliance,

I set down to his lance

All my proud adventures, undergone for pleasure.

Let us flee those shores, when misfortunes attack,

Of an age abandoned, shores marked with our track,

That make us say of time, in measuring out our ways:

“I had a brother once, a mother, and a friend;

Delights that had to end!

How many of my blood remain to me, how many days?”’

I found it impossible to finish my ode: I had draped my drum with melancholy to beat the recall of the dreams of my vanished nights; but always among my memories were mingled present thoughts whose happy mien defeated the dismal air of their old colleagues.

While poetising I saw a young girl sitting on the bank of a mountain stream; she rose and came straight towards me: she knew, by a rumour at large in the hamlet, that I was in Cauterets. I found that the unknown girl was an Occitanian, who had written to me two years previously without my ever having met her; the mysterious unknown unveiled for me: patuit Dea: the Goddess revealed herself.

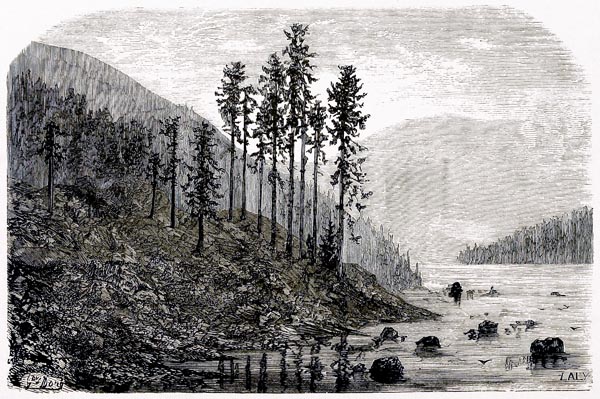

‘Near the Lake of Gaube’

A Tour Through the Pyrenees - Hippolyte Taine, John Safford Fiske, Gustave Dore (p330, 1875)

Internet Archive Book Images

I went to pay a respectful visit to the naiad of the torrent. One evening when she was with me as I was about to retire, she wished to follow; I was obliged to carry her back home in my arms. I have never felt so ashamed; to inspire such an attachment at my age seemed to me truly derisory; the more I might have been flattered by this absurdity, the more I was humiliated, treating it rationally as a joke. I would willingly have hidden myself out of shame, among the bears, our neighbours. I was far from saying what Montaigne said of himself: ‘Love restores to me my alertness, my moderation, my grace, and my care for my appearance.’ My poor Michel, you say the most delightful things, but at our age, you know, love does not restore to us what you suggest here. We have only one concern; that is to set ourselves on one side. Instead then of applying myself to sane and wise studies by means of which I may render myself more loveable, I have allowed the fugitive impression of my Clémence Isaure to fade; the mountain breeze soon carried away the flowery caprice; the witty, resolute and delightful stranger of sixteen was grateful for having been dealt with fairly; she is married.

Book XXXI: Chapter 2: Polignac’s Ministry – My dismay – I return to Paris

BkXXXI:Chap2:Sec1

Rumours of ministerial changes had reached our pine-woods. Well-informed people went so far as to speak of the Prince de Polignac; but I was completely incredulous. Finally, the newspapers arrived: I opened them and my eyes fell on the official decree which confirmed the previous rumours. I had experienced a good many changes of fortune since I had entered the world, but I had never received so great a shock. My destiny had once more put paid to my dreams; this breath of fate not only extinguished my illusions, it swept away the monarchy. This blow made me dreadfully ill; I felt momentary despair, since my mind was instantly made up, I felt I must resign. The post brought a shoal of letters; all urged me to send in my resignation. Even people I barely knew thought themselves obliged to suggest my retirement.

‘Polignac’

Histoire de la Révolution Française Depuis 1814 Jusqu'à 1830...Revue et Continuée par M. Auguis, Vol 04 - Jacques Antoine Dulaure (p850, 1838)

The British Library

I was shocked by this officious interest in my reputation. Thank heaven, I have never needed advice concerning matters of honour; my life has been a series of sacrifices which have never been dictated by anyone else; regarding questions of duty I act spontaneously. A fall from office spells ruin for me, since I own nothing but debts, debts which I contract in places where I do not live long enough to repay them; so that every time I retire from public life, I am reduced to working for a bookseller for hire. Some of those, proud, obliging people, who preached honour and liberty to me via the post, and who preached them still more loudly to me when I arrived in Paris, resigned from the Council of State; but some were rich, and the rest took care not to resign the lesser offices they held, which guaranteed them the means of existence. They were like the Protestants, who reject various parts of the Catholic dogma and retain others which are just as difficult to believe in. There was nothing total about these sacrifices; nothing of real sincerity: they surrendered an income of ten or fifteen thousand livres it is true, but they returned home rich in patrimonies, or at least provided with the daily bread they had prudently retained. In my case, there was no quibbling; they were full of self-abnegation on my behalf, they could not strip themselves sufficiently, on my behalf, of all I possessed: ‘Come now, Georges Dandin, pluck up your courage; confound it, son-in-law, don’t let us down; off with your coat! Throw two hundred thousand livres a year out the window, a position you find agreeable, an exalted and dignified post, the empire of the Arts in Rome, the happiness of finally receiving the reward for your long laborious struggle. Such is our good pleasure. At that price, you will enjoy our esteem. Just as we have taken off our cloaks, beneath which we are wearing good flannel waistcoats, throw off your velvet cloak, so you are naked. There you have perfect equality, an accord between the altar and the sacrifice.’

And, strange to relate, in their generous eagerness to push me out, the men who signified their desire to me were neither my true friends nor the co-supporters of my political opinions. I was to destroy myself on the spot for Liberalism, for a doctrine which had constantly attacked me; I was to run the risk of rocking the legitimate throne, in order to win the praises of a few cowardly enemies, who had not enough courage to go hungry.

I was to find myself swamped by my long embassy; the dinners I had given had ruined me, I had not covered the expenses of my initial establishment. But what broke my heart was the loss, for the rest of my days, of that happiness I had promised myself.

I was not obliged to reproach myself in any way with having taken that advice of a Cato, which impoverishes those who accept it not those who give it: quite convinced that such advice is useless anyway to the man who lacks depth of feeling. From the first moment, I say, my decision was made; it cost me little to make, but it was miserable to execute. When at Lourdes, instead of turning south and heading for Italy, I took the road to Pau, my eyes filled with tears, I confess my weakness. What matter that I had indeed accepted and supported the coalition which brought me my good fortune? I chose not to return quickly, so as to let time go by. I slowly unwound the thread of my journey that I had gathered up with such joy only a few weeks previously.

The Prince de Polignac feared my resignation. He felt that in leaving the Chamber I would take Royalist votes with me, and that I would question the existence of his Ministry. The thought was suggested to him of sending a despatch rider to me in the Pyrenees with an order from the King that I should go to Rome immediately, to welcome the King and Queen of Naples who had just seen their daughter married in Spain. I would have been highly embarrassed to have received such an order. Perhaps I would have considered myself forced to obey it, even if it meant giving in my resignation after it had been fulfilled. But, once in Rome, what would have happened? I would perhaps have been too late; the fatal days to come would have surprised me on the Capitol. Perhaps too the state of indecision I might have been placed in might have given Monsieur de Polignac a parliamentary majority, which he only lacked by a few votes. Then the fatal speech would not have occurred; the decrees, resulting from that speech, would not perhaps have seemed necessary to their unfortunate authors: Dis aliter visum: the gods decided otherwise.

Book XXXI: Chapter 3: Interview with Monsieur Polignac – I resign from the Rome Embassy

BkXXXI:Chap3:Sec1

In Paris I found Madame de Chateaubriand quite resigned. She had been thrilled by being the Ambassadress in Rome, and certainly a woman should have at least known that; but in moments of crisis, my wife has never hesitated to approve what she thought correct to maintain consistency in my life, and to enhance my name in public esteem: in that she shows herself finer than others. She loves position, titles and wealth; she hates poverty and thrift; she despises those sensitivities, that excess of loyalty and self-destructiveness which she considers true self-deception for which no one will thank you; she would never have cried: ‘Long live the King, even so’: but when it was a question of myself, all was different, she accepted my disgrace while cursing it with a firm spirit.

I always had to fast, watch and pray for the health of those who took great care to don the hair shirt with which they hastened to adorn me. I was the sacred donkey, the donkey burdened with the arid remains of liberty; remains which they adored with great devotion, so long as they were excused the trouble of bearing them.

The day after my return to Paris, I went to see Monsieur de Polignac. I had written him this letter on my arrival:

‘Paris, this 28th of August 1829.

Prince,

I thought it more fitting as regards our previous friendship, more suited to the noble position with which I have been honoured, and above all more respectful to the King, to come and place my resignation at his feet myself, rather than sending it to you hastily via the post. I ask a last service of you, that of asking the King to be so good as to grant me an audience, and to listen to the reasons which oblige me to renounce the Rome Embassy. Consider, Prince, what it costs me, at the moment when you are attaining power, to abandon that diplomatic career which I had the pleasure of introducing to you.

Accept, I beg you, my assurance of the feelings which I have vowed to you, and the high regard with which I have the honour to be, Prince,

Your very humble and obedient servant,

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

In reply to my letter, this note was sent to me from the Foreign Office:

‘The Prince de Polignac has the honour to offer his compliments to Monsieur le Vicomte de Chateaubriand, and requests him to come to the Ministry tomorrow, Sunday, at nine precisely, if that is possible.

Saturday, 4 o’clock.’

I replied immediately with this further note:

‘Paris, this evening of the 29th of August, 1829.

Prince, I have received a letter from your office which invites me to visit the Ministry tomorrow, the 30th, at nine precisely, if that is possible. As this letter does not inform me of the audience with the King which I have begged you to ask of him, I will wait until you have something official to communicate to me regarding the resignation which I desire to lay at His Majesty’s feet.

A thousand warm compliments,

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

Monsieur de Polignac then wrote me these words in his own hand:

‘I have received your little note, my dear Vicomte; I will be delighted to see you tomorrow at ten, if that hour suits you.

I renew the assurance of my former sincere attachment.

LE PRINCE DE POLIGNAC.’

This note seemed to me to augur badly; his diplomatic reserve led me to fear a refusal from the King. I found the Prince de Polignac in the large office which I knew so well. He hastened to me, grasped my hand with a heartfelt warmth which I would have liked to believe was sincere, and then, putting an arm round my shoulders, we began to walk slowly from one end of the office to the other. He told he would not accept my resignation; that the King would not accept it; that I must return to Rome. Each time he repeated this last phrase my heart sank: ‘Why,’ he asked me, ‘are you unwilling to do business with me as you have with La Ferronays and Portalis? Am I not your friend? I will give you all you wish in Rome; in France, you will be more of a Minister than I, and I will listen to your advice. Your resignation can only create new divisions. Do you wish to harm the government? The King will be very annoyed if you persist in your desire to resign. I beg you, dear Vicomte, do not do this foolish thing.’

I replied that it was not a foolishness; that I acted while in full possession of my reason; that his government would be very unpopular; that such prejudices might be unjust, but that they existed nevertheless; that all of France was convinced that he would attack public freedom, and that it was impossible for me, a defender of that freedom, to work with those who passed for being its enemy. I was somewhat embarrassed in my reply, since at heart I had no immediate objection to the new Ministers; I could only attack them over a future scenario whose likelihood they might properly reject. Monsieur de Polignac swore to me that he loved the Charter as much as I did; but he loved it in his own way, he loved it too nearly. Unfortunately the tenderness one shows a girl one has dishonoured served him little.

The conversation carried on in the same manner for almost an hour. Monsieur de Polignac ended by saying that, if I would consent to withdraw my resignation, the King would see me with pleasure and would listen to what I had to say against his Ministry; but that if I insisted on handing in my resignation, His Majesty thought it would be pointless to see me, and that a conversation between us could only be disagreeable.

I replied: ‘Consider my resignation as received then, Prince. I have never retracted anything in my life, and, since it does not suit the King to see his loyal subject, I no longer insist.’ After these words I withdrew. I begged the Prince to grant Monsieur le Duc de Laval the Rome Embassy, if he still desired it, and I recommended my legation staff to him. I then regained on foot, via the Boulevard des Invalides, the street containing my Infirmary, poor casualty that I was. Monsieur de Polignac seemed to me, as I left him, to possess that imperturbable confidence which made of him a mute eminently suited to strangling an Empire.

My resignation as Ambassador to Rome having been handed in, I wrote to the sovereign Pontiff:

‘Most Holy Father,

As Minister for Foreign Affairs in France in 1823, I had the pleasure of being the interpreter of the late King Louis XVIII’s sentiments regarding the wished-for elevation of Your Holiness to the chair of St Peter. As Ambassador of His Majesty Charles X at the court of Rome, I had the much greater pleasure of seeing Your Beatitude raised to the sovereign Pontificate, and of hearing His Holiness address me with those words which will be the glory of my life. In ending the noble commission which I have had the honour to fulfil towards him, I express to him the deep regret with which I shall not cease to be penetrated. It only remains for me, Most Holy Father, to lay my sincere thanks for your kindness at your sacred feet, and to ask your apostolic blessing.

I am, with the greatest veneration and most profound respect, Your Holiness’ very humble and very obedient servant,

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

I spent several days in my Utica tearing out my entrails; I wrote letters demolishing the edifice I had so lovingly constructed. As, when a man dies, it is the little details, the familiar domestic actions that move us, so in the death of a dream the small realities that destroy it are the most poignant. Eternal exile among the ruins of Rome had been my imagined goal. Like Dante, I had determined never to return to my native place. These testamentary elucidations cannot hold the interest for the readers of these Memoirs that they hold for me. The old bird falls from the branch where it had taken refuge; it leaves life for death. Caught by the current, it has merely changed streams.

Book XXXI: Chapter 4: Journalistic sycophancy

BkXXXI:Chap4:Sec1

When the swallows near the time for their departure, there is one that is first to take flight and announce the imminent journey to the others: I was the first winged messenger to anticipate the last flight of the Legitimacy. Did the praises with which the newspapers showered me delight me? Not in the least. Some of my friends thought to console me by assuring me that I was on the verge of becoming First Minister; that a round of the game freely played would decide my future: they assumed an ambition in me of which I had not a trace. I doubt that any man who lived with me for even a week would be unable to see my total lack of that passion, otherwise perfectly legitimate, which allows one to pursue a political career to the end. I was always anticipating the moment of my resignation: if I was passionate about the Rome Embassy, it is precisely because it could lead nowhere, and was a retreat into a cul-de-sac.

Finally, I had in the depths of my conscience a certain fear of already having pushed my opposition too far; I would inevitably become its location, centre, and focal point: I was afraid of it, and that fear increased my regrets for the tranquil retreat I had lost.

Be that as it may, one is obliged to burn incense before the wooden idol descended from its altar. Monsieur de Lamartine, a new and brilliant representative of France, wrote to me on the subject of his candidacy for the Academy, and ended his letter thus:

‘Monsieur de La Noue, who has just spent a few minutes with me, told me that he left you occupying your noble leisure with raising a monument to France. Each of your voluntary and courageous resignations has thus brought its tribute of esteem to your name, and glory to your country.’

‘Alphonse de Lamartine’

A Pilgrimage to the Holy Land, Comprising Recollections, Sketches, etc. Made During a Tour in the East in 1832-3 - Marie Louis Alphonse de. Lamartine (p6, 1835)

The British Library

This noble letter by the author of Poetic Meditations was followed by that of Monsieur de Lacretelle. He wrote to me in his turn:

‘What a moment they chose to insult you, a man of sacrifice, you whose fine actions cost you no less than do your fine works! Your resignation and the formation of a new government seem to me two events linked to each other in advance. You have acquainted us with acts of devotion, as Bonaparte acquainted us with victory; but he had many companions, and you have few imitators.’

Two highly literate men, writers of great merit, Monsieur Abel Rémusat, and Monsieur Saint-Martin, alone had the temerity to set themselves up against me; they were associates of Monsieur le Baron de Damas. I understand why they might have been somewhat annoyed with these people who scorn public office: there is a kind of insolence in it that they cannot abide.

Monsieur Guizot himself deigned to visit me at home; he thought he might bridge the immense distance that nature had placed between us; in approaching me he said these words full of everything that was proper: ‘Monsieur, it is all different these days!’ In that year of 1829, Monsieur Guizot needed me to aid his election prospects; I wrote to the electors of Lisieux; he was nominated; Monsieur de Broglie thanked me in this note:

‘Permit me to thank you, dear Sir, for the letter you have been good enough to address to me. I have made use of it as I ought, and am convinced that, like all which flows from you, it will bear fruit and beneficial fruit. For my part, I have also taken note of what concerns myself, since there is no event with which I am more closely identified and which inspires in me a more lively interest.’

The advent of July finding Monsieur Guizot a deputy, it transpired that I was partly the reason for his political rise; the prayer of the humble is sometimes heard in Heaven!

‘Guizot’

Nuestro Siglo. Reseña Histórica de los Más Importantes Acontecimientos Sociales, Artísticos, Científicos é Industriales de Nuestra Época - Otto von Leixner (p175, 1883)

The British Library

Book XXXI: Chapter 5: Monsieur de Polignac’s first Cabinet

BkXXXI:Chap5:Sec1

Monsieur de Polignac’s first colleagues were Messieurs de Bourmont, de La Bourdonnaye, de Chabrol, Courvoisier and Montbel.

On the 17th of June 1815, being in Ghent and staying in the Royal residence, I met a man at the foot of the stairs, in a frock coat with muddy boots, going up to see his Majesty. I recognised in that spiritual face, that slender nose and those fine mild serpent-like eyes, General Bourmont; he had deserted Bonaparte’s army on the 14th. Comte de Bourmont is a worthy officer, used to navigating difficult actions; but one of those men who, when placed in the front line, see obstacles and cannot overcome them, formed as they are to be led and not to lead: fortunate in his sons, Algiers will ensure his name survives.

‘Bourmont’

Histoire de la Révolution Française Depuis 1814 Jusqu'à 1830...Revue et Continuée par M. Auguis, Vol 04 - Jacques Antoine Dulaure (p922, 1838)

The British Library

The Comte de Bourdonnaye, once my friend, is quite the most awkward customer ever: he lets fly at you if you approach him; he attacks the speakers in the Chamber, as he does his neighbours in the countryside; he quibbles over a word, as he does over a lawsuit concerning a ditch. On the very day I was named Foreign Minister, he came to tell me he was breaking with me: I was a Minister. I smiled and let my male shrew go, who smiling himself, looked like a thwarted bat.

Monsieur de Montbel, initially Minister for Public Education, replaced Monsieur de la Bordonnaye at the Interior Ministry when the latter retired and Monsieur Guernon-Ranville took over from him at Education.

The two sides prepared for war: the government party issued ironic pamphlets against the Representative grouping; the opposition organised its affairs and spoke of refusing to pay taxes if the Charter was violated. A public association was formed to resist those in power, called the Breton Association: my compatriots had often taken the initiative in previous revolutions; Breton minds own to something of the storm-winds that torment the shores of our peninsula.

A newspaper, produced with the avowed aim of overthrowing the existing dynasty, inflamed opinion. The fine young bookseller Sautelet, driven to suicide by madness, had often wished to assist his party by dying in some startling manner; he was filled with the Republican paper’s ideas; Messieurs Thiers, Mignet and Carrel were its editors. The National’s patron, Monsieur le Prince de Talleyrand, brought not a sou to the coffers: he merely soured the journal’s spirit by pouring his share of treason and corrosion into the common fund. I received the following note from Monsieur Thiers at the time:

‘Monsieur,

Uncertain whether delivery of our new journal will be made correctly, I am sending you the first edition of the National. All my collaborators agree with me in begging you to consider yourself in truth, not as a subscriber, but as our unpaid reader. If in this first issue, a matter of great concern to me, I have succeeded in expressing opinions of which you approve, I will be reassured and certain of being on the right track.

Accept, Sir, my homage,

A. THIERS.’

I will return to the editors of the National; I will tell you how I came to know them; but for the present I must single out Monsieur Carrel: superior to Messieurs Thiers and Mignet, he had the lack of pretension to consider himself, at the time when I associated with him, as a supporter of the writers he headed: he defended with his sword the opinions those men of the pen unsheathed.

Book XXXI: Chapter 6: The Expedition to Algiers

BkXXXI:Chap6:Sec1

While they were gearing up for the fight, preparations for the expedition to Algiers were completed. General Bourmont, the Minister for War, named himself as leader of the expedition: did he wish to escape responsibility for the coup d’état he felt was coming? That is quite possible given his past history and his subtlety; but it was a disaster for Charles X. If the general had been in Paris at the time of the catastrophe, the portfolio vacated by the Minister for War would not have fallen into Monsieur de Polignac’s hands. Before striking a blow, assuming he would have consented to do so, Monsieur de Bourmont would have doubtless assembled the whole Royal Guard in Paris; he would have ensured money and provisions enough that the soldiers would have lacked nothing.

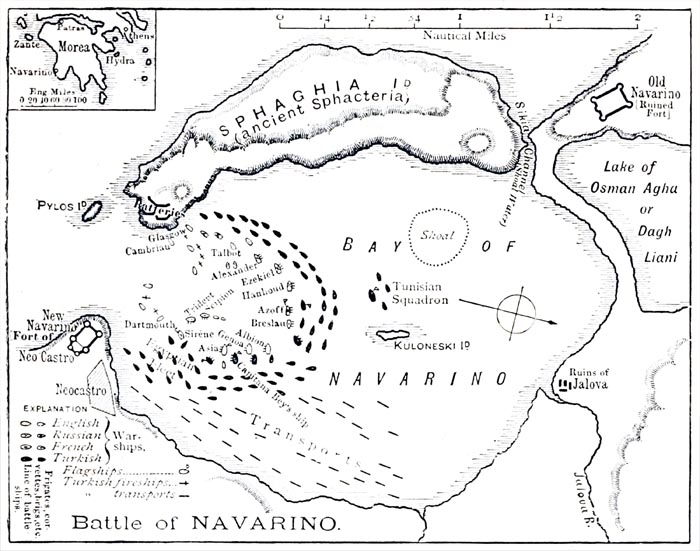

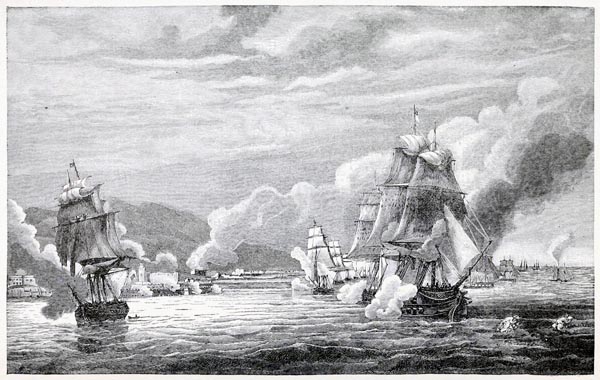

Our Navy revived by the battle at Navarino left those French harbours so neglected formerly. The roads were covered with ships that saluted the land as they departed. Steamboats, new inventions of human genius, came and went carrying orders from one squadron to another, like Sirens or aides de camp of the Admiral. The Dauphin stood on the shore, to which the entire population of the town and surrounding hills had descended: he, who having snatched his relative the King of Spain from the hands of the revolutionaries, saw the day break in which Christianity might be delivered, could he have conceived that he was so near his own eclipse?

‘Battle of Navarino’

Battles of the Nineteenth Century - Archibald Forbes, Andrew Hilliard Atteridge (p389, 1901)

Internet Archive Book Images

It was no longer that age when Catherine de Médici solicited the investiture of the Principality of Algiers for Henri III, not yet King of Poland! Algiers was to become our daughter and our conquest, without anyone’s permission, without England daring to prevent us taking that château of the Emperor, which recalled Charles V and his fluctuating fortunes. There was great happiness and joy for the French spectators assembled to salute, with Bossuet’s salute, the noble vessels ready to break the chains of slavery with their prows; a victory increased by that cry from the Eagle of Meaux, when he announced future success to the great king, as if to console him one day in the grave for the dispersal of his race:

‘You will yield, or fall to this attack, Algiers, rich in Christian spoils. You said in your avaricious heart: “My laws rule the sea, and the nations are my prey.” The agility of your vessels gives you confidence, but you will find yourselves attacked within your walls like a pretty bird that one seeks among the rocks in its nest, where it shares what it has scavenged with its brood. You already render up your slaves. Louis has broken the chains with which you burdened his subjects, who were born to be free within his glorious empire. The startled pilots cry as they advance: “What city is like Tyrus, like the destroyed in the midst of the sea.”’

‘The Bombardment of Algiers on July 4, 1830.

From a steel engraving by Skelton. (Versailles, Historical Gallery)’

A History of all Nations From the Earliest Times; Being a Universal Historical Library - John Henry Wright (p175, 1905)

Internet Archive Book Images

Magnificent words, could you not delay the collapse of a throne? The nations march to their fates, like certain of Dante’s shades, it is impossible to stop them, even amidst their good fortune.

Those vessels, which brought liberty to the shores of Numidia, carried off the Legitimacy; that fleet under its white banner was the monarchy weighing anchor, leaving the harbours where St Louis embarked, when death summoned it to Carthage. Slaves freed from the prisons of Algiers, those who returned you to your country have lost their own homeland; those who snatched you from endless exile are themselves exiled. The master of that vast fleet has crossed the sea as a fugitive in a little boat, and France might say of him as Cornelia did of Pompey: ‘It is because of my fortune, not yours, that I see you now reduced to one small boat, you who.had 500 ships with you when you sailed this sea.’

Among that crowd on the shore at Toulon who followed with their eyes that fleet departing for Africa, did I not have friends? Had not Monsieur du Plessis, my brother-in-law’s brother, taken under his wing a delightful woman, Madame Lenormant, who was awaiting the return of Champollion’s friend? What resulted from that hasty flight to Africa? Listen to Monsieur de Penhoen, my compatriot:

‘Barely two months since this same banner had been seen flying over five hundred vessels, in sight of these same shores. Sixty thousand men were then impatient to deploy on the African field of battle. Now a handful of invalids, a few wounded dragging themselves with difficulty round the bridge of our ship were its only followers. At the moment when the Guard presented arms in the customary salute to the flag, when it was raised or lowered, all conversation ceased on the bridge. I doffed my hat with the same respect I might have shown before the aged King himself. I knelt in profound tribute before the power of great misfortune at whose emblem I sadly gazed.’

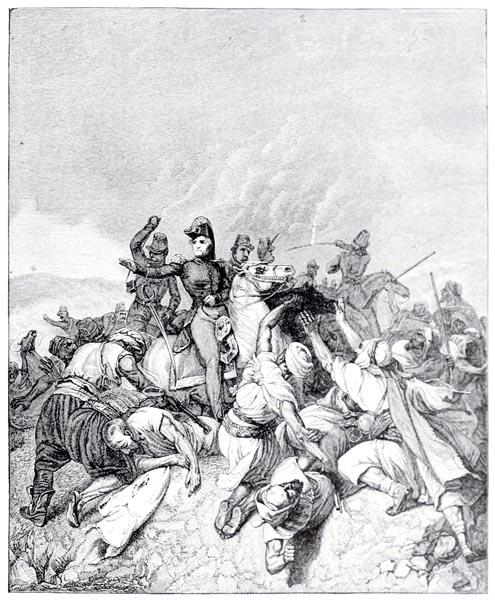

‘General Bugeaud in the Battle of Sickack. From the engraving by Samuel Cholet. Original painting by Horace Vernet (1789-1863) in the Historical Gallery at Versailles’

A History of all Nations From the Earliest Times; Being a Universal Historical Library - John Henry Wright (p256, 1905)

Internet Archive Book Images

Book XXXI: Chapter 7: The opening of the Session of 1830 – The speech – The Chamber is dissolved

BkXXXI:Chap7:Sec1

The Session of 1830 opened on the 2nd of March. The Royal speech had the King say: ‘If reprehensible manoeuvres create obstacles for my government which I could not and chose not to foresee, I will find the means of overcoming them.’ Charles X pronounced these words in the tones of a man who, by habit gentle and timid, happens to find himself angered, stirred by the sound of his own voice; the stronger the words, the weaker the resolutions that followed them.

The address in reply was written by Messieurs Étienne and Guizot. It read: ‘Sire, the Charter consecrates as a right the nation’s intervention in deliberations regarding the public interest. That intervention makes a permanent reconciliation of the views of your government with the desires of the people the indispensable condition for the harmonious progress of public affairs. Sire, our loyalty, our devotion forces us to tell you that this RECONCILIATION DOES NOT EXIST.’

The address was endorsed by a majority of two hundred and twenty-one to one hundred and eighty-one. An amendment by Monsieur de Lorgeril tried to remove the phrase regarding the denial of reconciliation. This amendment only obtained twenty-eight votes. If the two hundred and twenty-one had been able to foresee the result of their vote, the address would have been rejected by an immense majority. Why does Providence not sometimes raise a corner of the veil which hides the future? It gives certain people, it is true, a presentiment of things to come; but they see nothing clearly enough to be quite certain of the route; they fear to overstep the mark, or if they do adventure on predictions which are later fulfilled they are not believed. God never parts the clouds before the deeps in which he works; when he allows great evils, it is because he has great designs; designs which are part of a vast plan, extending to a far horizon beyond the range of our sight and the reach of our passing generations.

The King, replying to the address, declared that his resolution was immutable, that is to say that he would not dismiss Monsieur de Polignac. The dissolution of the Chamber was determined: Messieurs de Peyronnet and de Chantelauze replaced Messieurs de Chabrol and Courvoisier who retired; Monsieur Capelle was named as Minister for Commerce. There were twenty men in the offing capable of being Ministers; they could have recalled Monsieur de Villèle; they could have taken Monsieur Casimir Périer and General Sébastiani. I had already proposed the latter to the King, when after the fall of Monsieur Villèle, the Abbé Frayssinous was charged with offering me the Ministry of Education. But no; they had a horror of able men. In the ardour they felt for nobodies, they found, as if to humiliate France, whoever was most insignificant in order to place them at her head. They dug up Monsieur Guernon de Ranville, who was perhaps the bravest of the band of unknowns, and the Dauphin implored Monsieur de Chantelauze to save the monarchy.

The decree of dissolution summoned the district colleges for the 23rd of June 1830 and the departmental colleges for the 3rd July, only twenty-seven days before the end of the eldest branch of the monarchy.

The parties went to extremes, in their excitement: the Ultra-Royalists spoke of making the Crown a dictatorship; the Republicans dreamed of a Republic with a Directory or under a Convention. The Tribune, a paper affiliated to that party, appeared, and outshone the National. The great majority of the country still desired the Legitimacy, but with concessions and freedom from Court influence; ambition was rife, and everyone hoped to become a Minister; storms hatch out insects.

Those who wished to force Charles X to become a constitutional monarch thought they were in the right. They believed the Legitimacy was deep-rooted; they had forgotten the weakness of the man; Royalty could be pressurised, the King could not: the individual failed us, not the institution.

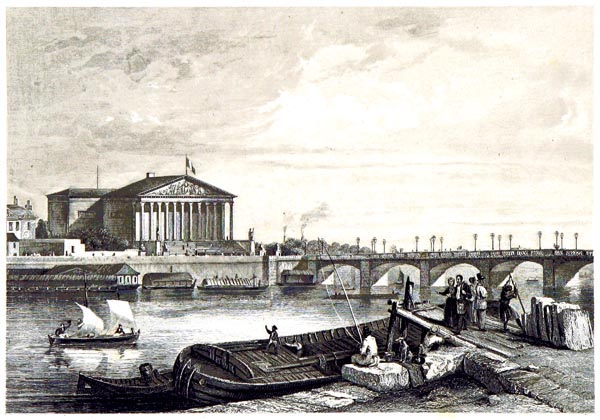

‘La Chambre des Députés’

Histoire Physique, Civile et Morale de Paris...Quatrième Édition - Jacques Antoine Dulaure (p770, 1846)

The British Library

Book XXXI: Chapter 8: The new Chamber – I leave for Dieppe – The decrees of the 25th of July – I return to Paris – Reflections on the way – A letter to Madame Récamier

BkXXXI:Chap8:Sec1

The new Chamber’s deputies arrived in Paris: of the two hundred and twenty-one, two hundred and ten had been re-elected; the opposition had two hundred and seventy votes; the government a hundred and forty-five: the party of the Court was therefore finished. The natural result was the resignation of the Government: Charles X persisted in braving all and the coup d’état was inevitable.

I left for Dieppe on the 26th of July, at four in the morning, on the very day the decrees appeared. I was quite joyful, delighted to be seeing the sea once more, and I was followed, at some hours distance, by a frightful storm. I dined and slept at Rouen without suspecting anything, regretting that I was unable to visit Saint-Ouen, and kneel before the lovely Madonna in the museum, in memory of Raphael and Rome. I arrived in Dieppe next day, the 27th, around noon. I stayed at the hotel where Monsieur le Comte de Boissy, my former secretary at the legation, had arranged lodgings for me. I dressed and went to meet Madame Récamier. She occupied an apartment whose windows opened onto the foreshore. I spent several hours there talking and watching the waves. Suddenly Hyacinthe arrived; he brought me a letter that Monsieur de Boissy had received, announcing the decrees, with a flourish of praise. A moment later, my old friend Ballanche came in; he had arrived in the coach clasping the newspapers in his hands. I opened the Moniteur and read the official news, scarcely believing my eyes. Here was a government which, with deliberate intent, was hurling itself from the towers of Notre Dame! I told Hyacinthe to request horses, so as to leave for Paris again. I took a carriage, towards seven in the evening, leaving my friends in a state of anxiety. There had been murmurings of a coup d’état for a month or so, but no one had paid attention to the rumours, which seemed absurd. Charles X had spun illusions about the throne; he had created a mirage before the Princes which deceived them by displacing objects, and inspiring them to see imaginary countries in the sky.

I brought the Moniteur with me. As soon as it was daylight, on the 28th, I read, re-read, and commented on the decrees. The report to the King serving as a prolegomenon struck me from two perspectives: the observations on the disadvantages of the Press were just; but at the same time the author of those observations showed complete ignorance of the true state of society. Doubtless the Ministries, since 1814, of whatever persuasion, had been harassed by the papers; doubtless the Press tends to smother sovereignty, and drives royalty and the Chambers to obey it; doubtless, during the final days of the Restoration, the Press, blinded by passion, had, without regard to French honour and interests, attacked the expedition to Algiers, elaborating on the reasons, means, and preparations for it, and the chances of non-success; it had divulged confidential details of the armaments, revealed the state of our forces to the enemy, tallied our troops and ships, even indicated the point of embarkation. Would Cardinal Richelieu and Bonaparte have brought Europe to its knees before France, if they had thus revealed in advance the secrets of their negotiations, or signalled the halting places of their armies?

All that is true and shameful; but what is the remedy? The Press is an element once unseen, a force previously unknown, now active in the world; it is the word as lightening; it is social electricity. Can you prevent it existing? The more you try to suppress it, the more violent the explosion will be. You must resolve to live with it, as you live with the steam-engine. You must teach it to serve you, by robbing it of its dangers, either by weakening it little by little through familiar everyday use, or by gradually adjusting your laws and manners to the principles which will rule humanity from now on. A proof of the powerlessness of the Press in certain situations emerges from the very reproach you made against it in regard to the Algiers expedition; you took Algiers, despite the freedom of the Press, just as I undertook the war in Spain in 1823 beneath the most withering fire produced by that freedom.

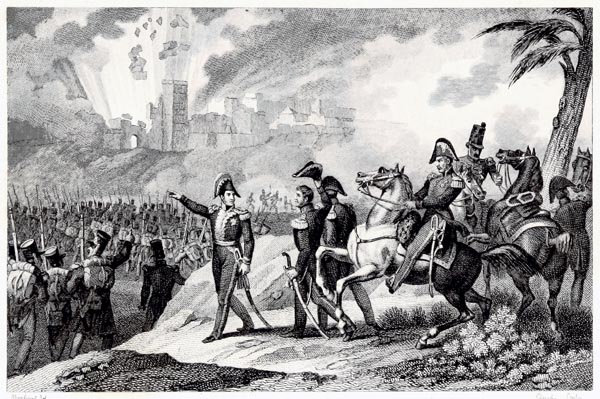

‘Prise de la Casbah d'Alger (juillet 1830)’

Histoire de la Révolution Française Depuis 1814 Jusqu'à 1830...Revue et Continuée par M. Auguis, Vol 04 - Jacques Antoine Dulaure (p947, 1838)

The British Library

But what is intolerable to read in the Ministers’ reports is that pretentious effrontery: that the KING HAS POWERS THAT PRE-DATE THE LAWS. What is the point of a constitution then? Why deceive the people with false guarantees, when the monarch can alter the established order of government at will? And yet the signatories of the report were so convinced of what they said, that they took pains to cite article 14, with the benefit of which, as I had declared long ago, they could appropriate the Charter; they mentioned it, but only for the record, and as a superfluous right which they did not need to employ.

The first decree established the suppression of Press freedom in its various forms; it was the quintessence of all that had been elaborated in the cubby-holes of the police department over fifteen years.

The second decree reworked the electoral laws. Thus the two primary freedoms, the freedom of the Press and electoral freedom, were radically harmed: this emanated not from an iniquitous though legal action of a corrupt legislative authority, but by decree, as in the days of royal whim. And five men not lacking in common sense hurled themselves, their master, the monarchy, France and Europe, with unexampled rashness, into the abyss. I was unaware what was happening in Paris. I desired a resistance movement to force the Crown, without overthrowing the throne, to dismiss the Ministers and withdraw the decrees. In the event that the latter triumphed, I was resolved not to submit, but to write and speak out against these unconstitutional measures.

If the members of the diplomatic corps did not directly influence the decrees, they favoured them with their votes; Europe had an absolute horror of our Charter. When the news of the decrees arrived in Berlin and Vienna, and for twenty-four hours they were considered a success, Monsieur Ancillon proclaimed that Europe was saved, and Prince von Metternich showed inexpressible joy. After learning the truth, the latter was as concerned as he had been delighted; he declared that he was mistaken, that public opinion was decidedly liberal, and that he was accustoming himself already to the idea of an Austrian constitution.

The nominations of the Councillors of State which followed the July ordinances threw some light on the people who, in the antechambers, by their advice or their writings, had been prepared to support the decrees. The men most opposed to representative government were signalled out. Were those fatal documents penned in the very office of the King, under the monarch’s own eyes? Were they written in Monsieur de Polignac’s office? Were they agreed in a meeting solely of Ministers or were they assisted by a few loyal anti-constitutional minds? Was it under the Leads, in some secret session of the Ten, that those decisions of July were made, in virtue of which the Legitimacy was condemned to strangulation on the Bridge of Sighs? Were the decrees Monsieur de Polignac’s own idea? Perhaps that is something history will never reveal.

Arriving in Gisors, I learnt of the uprising in Paris, and heard various alarming proposals; they proved how seriously the Charter had been taken by the population of France. At Pontoise, there was more recent news still, but confusing and contradictory. At Herblay, there were no post-horses. I waited almost an hour. I was advised to avoid Saint-Denis, because I would find it barricaded. At Courbevoie, the postilion had already abandoned his jacket with its fleur-de-lis buttons. He had spent the morning with a calash which he had conducted to Paris via the Avenue des Champs-Élysees. Consequently, he told me he would not take me that way, and would head for the Barrière de Trocadero, to the right of the Barrière de l’Étoile. From this gate Paris is revealed. I saw the tricolour flag flying; I judged that it was not merely a riot, but a revolution. I had the presentiment that my role would be altered: that having hastened to defend public freedoms, I would be obliged to defend Royalty. Clouds of white smoke rose here and there among the houses. I heard cannon-shot and the sound of muskets blended with the noise of the alarm-bells. From the height of the empty plateau destined by Napoleon as the site of the palace of the King of Rome, it seemed I was watching the ancient Louvre fall. The observation post presented one of those philosophic consolations that one disaster offers another.

My carriage descended the slope. I crossed the Pont d’Iéna, and ascended the paved avenue along the Champs de Mars. All was deserted. I found a cavalry picket posted before the railings of the Military College; the men had a sad air as if forgotten. We took the Boulevard des Invalides and the Boulevard Montparnasse. I encountered several passers-by who gazed with astonishment at a carriage led by a postilion as if these were normal times. The Boulevard d’Enfer was blocked by felled elm-trees.

In my street, my neighbours were delighted at my arrival: I seemed to offer a protection to the whole quarter. Madame de Chateaubriand was at once comforted and alarmed by my return.

On the morning of Thursday the 29th of July, I wrote this letter, lengthened by its postscript, to Madame Récamier, at Dieppe:

‘Thursday morning, the 29th of July 1830.

I write to you without knowing if my letter will arrive, since the couriers are no longer leaving.

I entered Paris in the midst of a cannonade, a fusillade, and the sounds of the tocsin. This morning, the alarm-bell is still sounding, but I can no longer hear gunfire; it seems that there is an element of organisation and that resistance will continue until the decrees are repealed. This is the immediate result (without calling it the definitive result) of the perjury by which the Ministers have wronged the Crown, at least in appearance!

The National Guard, the École Polytechnique, all are involved. I have seen nobody as yet. You may judge in what state I found Madame de Chateaubriand. Anyone, who, like her, witnessed the 10th of August and the 2nd of September, retains a permanent memory of the Terror. One regiment, the 5th of the Line, has already gone over to the side of the Charter. Certainly Monsieur de Polignac is greatly to blame; his lack of ability is a poor excuse; an ambition for which one has not the talent is a crime. They say the Court is at Saint-Cloud and ready to flee.

I will not speak of myself; my position is tiresome but straightforward. I will betray neither the King nor the Charter, neither the Legitimacy nor freedom. I have nothing more to say or do than wait and weep for my country. God only knows what will happen in the provinces; they already speak of an insurrection at Rouen. On another front, the Congregation will arm the Chouans and the Vendée. What Empires depend on! A decree and six Ministers without talent or virtue are enough to turn the most tranquil and flourishing country into one of the most troubled and unfortunate.’

‘Mid-day.

The firing has recommenced. It seems they are attacking the Louvre where the Kings troops are entrenched. The suburb I live in is beginning to revolt. They talk of a provisional government whose leaders would be General Gérard, the Duc de Choiseul and Monsieur de Lafayette.

This letter will probably not leave Paris, since the city is declared to be in a state of siege. Marshal Marmont commands for the King. They say he has been killed, but I do not believe it. Try not to worry too much. God protect you! We will meet again!’

‘Friday.

This letter was written yesterday; there was no way of sending it. All is over: the popular victory is complete; the King has yielded on all points; but I fear they will now go way beyond the concessions made by the Crown. I wrote to His Majesty this morning. Meanwhile, I have a total scheme of future sacrifice which appeals to me. We will speak of it when you arrive.

I am going to put this letter in the post myself, and reconnoitre Paris.’

End of Book XXXI