François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXXVII: Charles X in exile 1833

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXXVII: Chapter 1: The Castle of the Kings of Bohemia – A first interview with Charles X

- Book XXXVII: Chapter 2: Monsieur le Dauphin – The Children of France – The Duke and Duchess de Guiche – The Triumvirate - Mademoiselle

- Book XXXVII: Chapter 3: A conversation with the King

- Book XXXVII: Chapter 4: Henri V

- Book XXXVII: Chapter 5: Dinner and an evening at the Hradschin

- Book XXXVII: Chapter 6: Visits

- Book XXXVII: Chapter 7: Mass – General Skrzynecki

- Book XXXVII: Chapter 8: Dinner at Count Choteck’s

- Book XXXVII: Chapter 9: Whit Sunday – The Duc de Blacas

- Book XXXVII: Chapter 10: DIGRESSIONS: A description of Prague – Tycho Brahe - Perdita

- Book XXXVII: Chapter 11: MORE DIGRESSIONS: Of Bohemia – Slavic and Neo-Latin Literature

- Book XXXVII: Chapter 12: I take leave of the King – Farewells – A letter from the children to their mother – A Moneychanger – The Saxon servant

- Book XXXVII: Chapter 13: What I left behind in Prague

- Book XXXVII: Chapter 14: The Duc de Bordeaux

Book XXXVII: Chapter 1: The Castle of the Kings of Bohemia – A first interview with Charles X

Prague, the 24th of May 1833.

BkXXXVII:Chap1:Sec1

Entering Prague on the 24th of May at seven in the evening, I arrived at the Hôtel des Bains, in the old town on the left bank of the Moldau. I wrote a note to Monsieur le Duc de Blacas to alert him to my arrival; I received the following reply:

‘If you are not too tired, Monsieur le Vicomte, the King would be delighted to receive you this evening, at nine forty-five; but if you wish to rest, it would give His Majesty great pleasure to see you tomorrow morning at eleven thirty.

Accept, I beg you, my deepest compliments.

This Friday, the 24th of May, at seven.

BLACAS D’AULPS.’

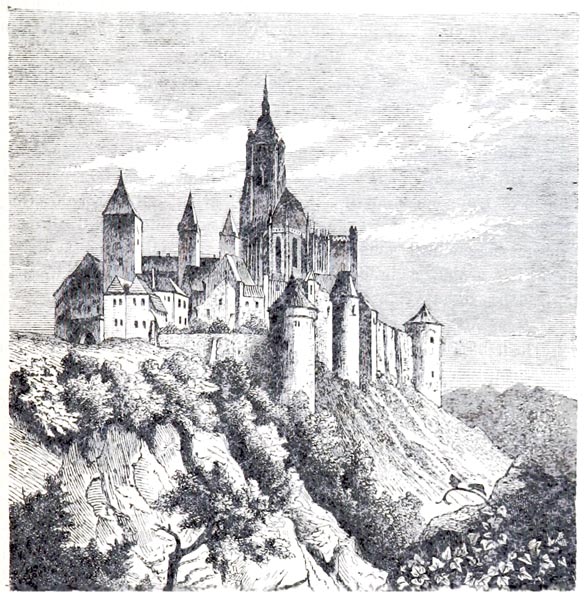

I did not wait to profit from the alternative offered me: at nine thirty I set off: an employee of the inn, who knew a few words of French, escorted me. I climbed through silent, sombre streets, with barely an echo, to the foot of the tall hill crowned by the Castle of the Kings of Bohemia. The edifice etched its dark mass on the sky; no light shone from the windows: it possessed something of the solitariness, the setting, and the grandeur of the Vatican, or of the Temple Mount of Jerusalem seen from the Valley of Jehoshaphat. The only sound was that of my footsteps and those of my guide; I was obliged to stop at intervals on the staged stone landings, so fast was the pace.

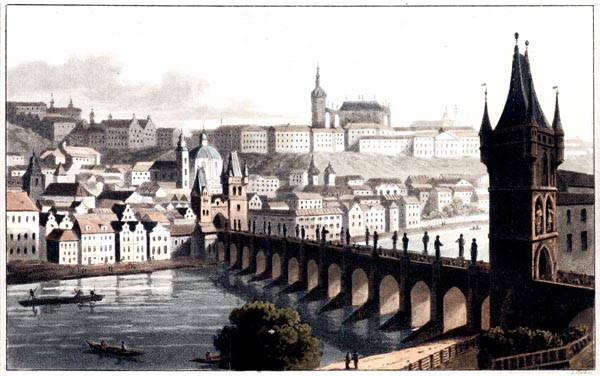

‘Prague’

Travels through some parts of Germany, Poland, Moldavia, and Turkey - Adam Neale, John Clark (p111, 1818)

Internet Archive Book Images

The more I climbed the more I could see of the city below. The chain of history, the fate of mankind, the destruction of empires, the designs of Providence presented themselves to my mind, mingling themselves with memories of my own life: having explored dead ruins I was summoned to the sight of living ones.

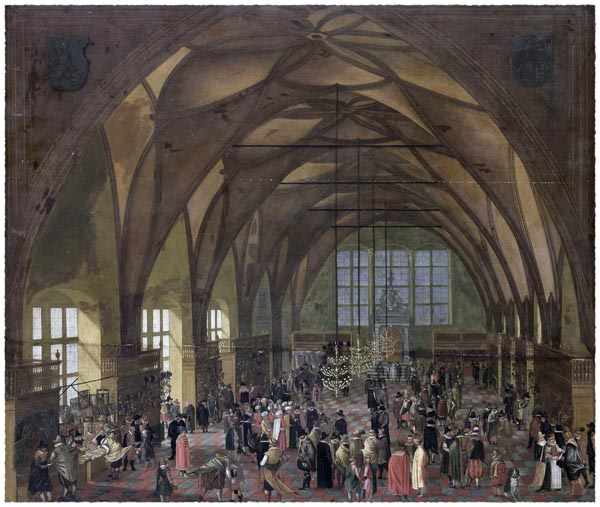

Arriving at the summit on which the Hradschin is built, we passed through an infantry post whose guards were positioned next to the exterior wicket. Beyond this door we penetrated a square courtyard, surrounded by battlements, uniformly deserted. We filed to the right down a long corridor on the ground floor lit at intervals by glass lanterns attached to the face of the walls, as in a barracks or a convent. At the end of this corridor a staircase ascended, at the foot of which two sentries walked to and fro. As I was climbing to the second storey, I met Monsieur de Blacas who was descending. With him I entered Charles X’s apartments; there, two more grenadiers were on guard. Those foreign guardsmen, those white uniforms at the King of France’s door made a painful impression on me: the idea of a prison rather than a palace came to mind.

‘Large Hall in the Prague Hradschin Castle’

Anonymous - c. 1607 - 1615

The Rijksmuseum

We passed three darkened, virtually unfurnished rooms: I imagined I was wandering in the dreaded Monastery of the Escorial. Monsieur de Blacas left me in the third room in order to go and alert the King, according to the etiquette of the Tuileries. He returned to seek me, led me to His Majesty’s office, and withdrew.

Charles X approached me, and held out his hand cordially saying: ‘Good day, good day, Monsieur de Chateaubriand, I am delighted to see you. I was waiting for you. You had no need to come tonight, as you must be very tired. Do not remain standing: let us sit. How is your wife?’

Nothing tugs at the heart more than simple words among the highest ranks of society, and in the great catastrophes of life. I began to weep like a child; I had difficulty stifling the sound of my crying with my handkerchief. All the harsh things I had determined to say, all the vain and merciless philosophy with which I counted on arming my discourse, failed me. I, to become an instructor to misfortune! I, to dare lord it over my King, my white-haired King, my proscribed and exiled King, preparing to leave his mortal remains on foreign soil! My aged Prince took me again by the hand seeing the distress of his merciless enemy, of that fierce opponent of the July decrees. His eyes were moist; he made me sit beside a little wooden table on which there were two candlesticks; he sat near the same table, turning his good ear towards me to hear me more clearly, alerting me in that way to his years which united common infirmity with the extraordinary calamities of his life.

‘Charles X’

Histoire de la Révolution Française Depuis 1814 Jusqu'à 1830...Revue et Continuée par M. Auguis, Vol 04 - Jacques Antoine Dulaure (p588, 1838)

The British Library

I found it impossible to recover my voice, as I gazed, in the residence of the Emperors of Austria, at the sixty-eighth King of France bent beneath the weight of those reigns and his seventy-six years: of those years, twenty-four had been spent in exile, five on a tottering throne; the monarch was ending his last days in a last exile, with a grandson whose father had been assassinated and whose mother was a prisoner. Charles X, in order to relieve the silence, asked me a few questions. Then I explained the object of my journey, briefly: I told him I was bearing a letter from Madame la Duchesse de Berry, addressed to Madame la Dauphine, in which the captive of Blaye confided the care of her children to that prisoner of the Temple, as one having experience of misfortune. I added that I also had a letter for the children. The King replied: ‘Do not give it to them; they are partly unaware of what has happened to their mother; you shall give me the letter. Anyway we will talk about all this tomorrow at two: go and get some rest. You will see my son and the children at eleven, and dine with us.’ The King rose, wished me goodnight and withdrew.

I left; I rejoined Monsieur de Blacas in the ante-room; my guide was waiting on the stairs. I returned to my inn, descending the streets, over the slippery paving stones, with as much rapidity as I had shown slowness in ascending.

Book XXXVII: Chapter 2: Monsieur le Dauphin – The Children of France – The Duke and Duchess de Guiche – The Triumvirate - Mademoiselle

Prague, the 25th of May 1833.

BkXXXVII:Chap2:Sec1

Next day, the 25th, I received a visit from Monsieur le Comte de Cossé, who was lodging in my inn. He told me about the arguments at the Palace regarding the education of the Duke of Bordeaux. At half past ten I climbed to the Hradschin; the Duc de Guiche led me to the Dauphin’s apartments. I found him thin and aged; he was dressed in a threadbare blue coat, buttoned to the chin, and which, too large for him, seemed to have been bought at a second-hand clothes store: the poor Prince made me feel extremely sorry for him.

Monsieur le Dauphin needed courage; his obedience to Charles X alone prevented him from showing himself to be, at Saint Cloud and Rambouillet, what he had shown himself to be at Chiclana: his unsociability has increased. He can hardly bear the sight of a new face. He often asks the Duc de Guiche: ‘Why are you here? I need no one. There is no mouse-hole small enough to hide me.’

He has often said: ‘Let no one speak of me; let no one be concerned about me; I am nothing; I wish to be nothing. I have an income of twenty thousand francs: it is more than I need. I need only think about my health and about making a good end.’ He often says: ‘If my nephew needs me, I will serve him with my sword; but I have signed my abdication, against my wishes, in order to obey him; I will not repeat it; I will sign nothing more; let them leave me in peace. My word is enough: I never lie.’

And that is true: his lips have never proffered an untruth. He reads much; he is quite learned, even in languages; his correspondence with Monsieur de Villèle during the War in Spain is prized, and his correspondence with Madame la Dauphine, intercepted and printed in the Moniteur, makes one love him. His probity is unshakeable; his religiosity is profound; his filial piety shows true virtue; but an unconquerable shyness inhibits the Dauphin’s proper employment of his abilities.

To put him at his ease, I avoided discussion of politics and only enquired after his father’s health; a subject on which he was voluble. The change in climate between Edinburgh and Prague, the King’s long-standing gout, the waters of Teplitz which the king would take, and the good they would do him, was the content of our conversation. Monsieur le Dauphin watched over Charles X as if he were an infant; he kissed his hand when he approached, asked how he had slept, picked up his handkerchief, talked loudly so he might hear, prevented him from eating what might disagree with him, made him put on or take off his coat depending on the coldness or warmth of the weather, accompanied him on his walks and brought him back. I was careful to speak of nothing else: of the July Days, the fall of an empire, the future of the monarchy, not a word. ‘It is eleven o’clock,’ he said to me: ‘You shall go and see the children; we will meet at dinner.’

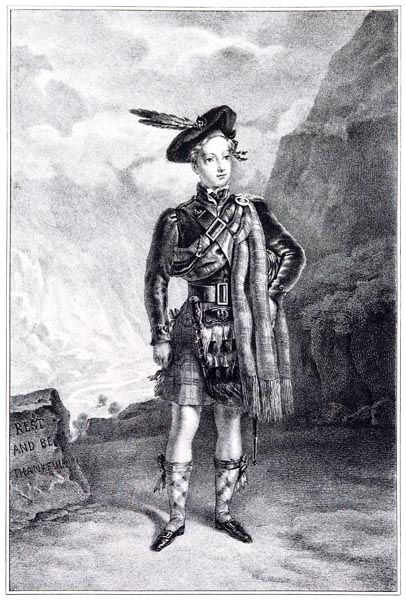

Escorted to the tutor’s apartments, the doors opened: I saw Baron de Damas, with his pupil; Madame de Gontaut with Mademoiselle, Monsieur Barrande, Monsieur Lavilatte and other devoted followers; everyone rose. The young Prince, who was frightened, looked askance at me, and looked at his tutor as if to ask what he should do, in what manner he should act in this peril, or how to obtain permission to speak to me. Mademoiselle smiled a half-smile with a shy but independent air; she seemed attentive to her brother’s actions and gestures. Madame de Gontaut seemed proud of the education she had given her. Having saluted the two children I advanced towards the orphan and said: ‘May Henri V permit me to lay my respectful homage at his feet. When he recovers his throne, he may remember that I had the honour to say to his illustrious mother; Madame, your son is my King. Thus I was the first to proclaim Henri V King of France, and a French jury, by acquitting me, has allowed my proclamation to stand. Long live the King!’

‘Henri V en Costume de Highlander, Site de Glen Croe’

Souvenirs des Highlands. Voyage à la Suite de Henri V. en 1832 - Harles Achille d'Hardivillier (p10, 1835)

The British Library

The boy, astounded to hear himself saluted as King, to hear me speak of his mother whom no one spoke of, recoiled into the arms of Baron de Damas, while pronouncing a few words emphatically but in a low voice. I said to Monsieur de Damas:

‘Monsieur le Baron, my speech seems to have astonished the King. I see he knows nothing of his mother’s courage and is unaware of what his servants have had the happiness to do on occasion for the cause of the Royal Legitimacy.’

The tutor replied: ‘We teach Monseigneur what loyal subjects, such as you are yourself Monsieur le Vicomte...’ He failed to complete the sentence.

Monsieur de Damas hastened to announce that the moment for study had arrived. He invited me to the riding lesson at four.

I went to see Madame la Duchesse de Guiche, who lodged some distance away in another part of the Palace; it took more than ten minutes to find the way there from corridor to corridor. As Ambassador to London, I had given a small supper for Madame de Guiche, then in all the brilliance of her youth and followed by a crowd of admirers; in Prague I found her altered, but her facial expression pleased me more. Her coiffure became her beautifully; her hair, plaited in little tresses like those of an odalisque or a Sabine medallion, fastened with a headband, adorned both sides of her brow. In Prague, the Duchess and Duke de Guiche represented beauty linked to adversity.

Madame de Guiche had been informed of what I had said to the Duc de Bordeaux. She told me that they would part with Monsieur de Barrande; that it was a question of summoning the Jesuits; that Monsieur de Damas had suspended but not abandoned his plans.

There was a triumvirate composed of the Duc de Blacas, Baron de Damas, and Cardinal Latil; this triumvirate wished to control any future reign by isolating the young King, having him raised according to principles, and by men, antipathetic to France. The remaining inhabitants of the Palace conspired against the triumvirate; the children themselves were at the head of the opposition. However the opposition took on various nuances; the Gontaut party was absolutely not the Guiche party; the Marquise de Bouillé, a defector from the Berry Party, ranged herself on the side of the triumvirate with the Abbé Moligny. Madame la Dauphine, as the head of the group of impartial observers, was not exactly favourable to the party of Young France, represented by Monsieur Barrande; but as she spoiled the Duc de Bordeaux, she often inclined to his side, and supported him against his tutor.

Madame d’Agoult, devoted body and soul to the triumvirate, had no other influence with the Dauphine than that of her presence and persistence.

Having paid my court to Madame de Guiche, I went to see Madame de Gontaut. She was waiting for me with Princess Louise.

Mademoiselle resembles her father a little: her hair is blonde; her blue eyes have a fine expressiveness; small for her age, she is not as well-formed as her portraits show. Her whole person is a mixture of child, young woman and Princess: she gazes, lowers her eyes, and smiles with a naive coquetry allied with art: one does not know whether to read her fairy stories, make a declaration, or talk to her with the respect due to a queen. Princess Louise supplements agreeable talents with considerable knowledge: she speaks English and has started to learn German; she even has something of a foreign accent and exile has already influenced her speech.

Madame de Gontaut presented me to my little King’s sister: innocent fugitives, they looked like two gazelles hiding amongst the ruins. Mademoiselle Vachon, the assistant governess, an excellent and distinguished woman, arrived. We sat down, and Madame de Gontaut said: ‘We can speak, Mademoiselle knows everything; she deplores what we see just as we do.’

Also Mademoiselle said to me: ‘Oh, Henri was very stupid this morning: he was afraid! Grandpapa said to us: “Guess who you will see tomorrow: he is a power on this earth!” We replied: “Well, is it the Emperor?” “No,” said Grandpapa. We tried, but could not guess. He said: “It is the Vicomte de Chateaubriand. I slapped my forehead for not having guessed.” And the Princess slapped her forehead, blushing like a rose, smiling spiritually with her lovely moist and tender eyes; I was dying of a respectful desire to kiss her little white hand. She went on:

‘You did not hear what Henri said to you when you recommended him to remember you. He said: “Oh yes, always!” But he said it so quietly! He was afraid of you and afraid of his tutor. I was making signs to him, did you see? You will be happier this evening; he will speak; just wait.’

This solicitude of the Princess on behalf of her brother was charming; I was almost guilty of lèse-majesté. Mademoiselle noticed it, which gave her a sweet and graceful air of conquest. I reassured her as to the impression Henri had made upon me. ‘I was very pleased’, she said, ‘to hear you speak of Mama before Monsieur de Damas. Will she soon be released from prison?’

You know I had a letter from Madame la Duchesse de Berry for the children, but did not speak of it to them since they were unaware of the latest details of her captivity. The King had demanded the letter of me; I considered that I was not permitted to hand it to him, and ought to take it to Madame la Dauphine, to whom I had been sent, and who was then taking the waters at Carlsbad.

Madame de Gontaut repeated to me what Madame de Cossé and Madame de Guiche had said. Mademoiselle groaned with childish gravity. Her governess having spoken of Monsieur Barrande’s dismissal and the probable arrival of a Jesuit, Princess Louise crossed her hands and said with a sigh: ‘That will be very unpopular!’ I could scarcely prevent myself from smiling; Mademoiselle began to smile also, still blushing.

A few moments remained before my audience with the King. I clambered back into my calash and went to find the Supreme Burgrave, Count Choteck. He lied in a country house a few miles outside the city, on the Palace side. I found him at home and thanked him for his letter. He invited me to dine with him on Monday, the 27th of May.

Book XXXVII: Chapter 3: A conversation with the King

BkXXXVII:Chap3:Sec1

Returning to the Palace at two, I was conducted to the King by Monsieur de Blacas as on the previous evening. Charles X received me with his usual kindness and that elegance of manner that his years made more noticeable in him. He made me sit down once more at the little table. Here are the details of our conversation: ‘Sire, Madame la Duchesse de Berry ordered me to seek you out and present a letter to Madame la Dauphine, I do not know what the letter contains, even though it is unsealed; it is written with lemon-juice, as is that to the children. But in my two letters of instruction, the one ostensible, the other confidential, Marie-Caroline explained her intentions. She places her children, during her captivity, as I said to Your Majesty yesterday, under the especial protection of Madame la Dauphine. Madame la Duchesse de Berry charged me moreover with giving her an account of the education of Henri V, whom they call the Duc de Bordeaux here. Finally, Madame la Duchesse de Berry declares that she has contracted a secret marriage with Count Hector Lucchesi-Palli, of an illustrious family. These secret marriages of Princesses, of which there are several examples, have not deprived them of their rights. Madame la Duchesse de Berry asks to retain her rank as a French Princess, the Regency and her guardianship. When she is freed, she proposes to come to Prague to embrace her children and lay her respects at Your Majesty’s feet.’

The King responded harshly to me. I took his reply, for better or worse, as a complaint.

‘Pardon me, Your Majesty, but it seems that someone has inspired prejudice against her: Monsieur de Blacas must be my august client’s enemy.’

Charles X interrupted me: ‘No, but she treated him badly, because he prevented her committing various stupidities, and undertaking foolish enterprises.’ – ‘It is not given to everyone’, I replied, ‘to commit stupidities of that kind: Henri IV fought like Madame la Duchesse de Berry, and like her he had not always enough forces.’

‘Sire,’ I continued, ‘though you may not wish Madame de Berry to be a French Princess, she will be one despite you; everyone will always call her the Duchesse de Berry, the heroic mother of Henri V; her courage and her suffering tower above all; you cannot place yourself in the ranks of her enemies; you cannot follow the Duc d’Orléans’ example, and wish to destroy the mother and her children with one blow: is it so hard for you to forgive a woman her glory?’

‘– Well, Monsieur l’Ambassadeur,’ said the King with a kindly emphasis, ‘let Madame la Duchesse de Berry wing her way to Palermo; let her live there maritally with Monsieur Lucchesi, in the whole world’s sight, then we can tell the children their mother is married; she can come and embrace them.’

I felt I had pushed the matter hard enough; the principal points were three-quarters won, the preservation of her title and admission to Prague at a more or less distant time: sure of completing my work with Madame la Dauphine, I changed the subject of conversation. Stubborn spirits balk at pressure; with them one spoils everything by trying to carry everything to a final conclusion.

In the interest of the future, I turned to the Prince’s education; on that subject, I was barely understood. Religion has made a solitary of Charles X; his ideas are cloistered. I slipped in a few words on the capacity of Monsieur Barrande and the incapacity of Monsieur de Damas. The King said: ‘Monsieur Barrande is a learned man, but he takes too much on; he was selected to teach the exact sciences to the Duc de Bordeaux, and he teaches everything, history, geography, Latin. I summoned the Abbé MacCarthy, in order to share Monsieur Barrande’s labour; he has died; I have cast my eye on another instructor; he will arrive soon.’

These words made me shudder, since the new instructor could evidently only be a Jesuit replacing a Jesuit. That, in the current state of French society, the idea of placing a disciple of Loyola with Henri V should have entered Charles X’s head is reason to despair of that race.

When I had recovered from my astonishment, I said: ‘Does the King not fear the effect on public opinion of an instructor chosen from a celebrated but slandered society?’

The King cried out: ‘Bah! Aren’t they with the Jesuits even so?’

‘Loyola’

History of the Jesuits: Their Origin, Progress, Doctrines, and Designs - Giovanni Battista Nicolini (p7, 1854)

Internet Archive Book Images

I spoke to the King about the elections and the Royalists’ desire to know his wishes. The King replied: ‘I cannot say to someone: Take the oath against your conscience. Those who believe they ought to swear it are no doubt acting with good intentions. I have no objection to anyone, my dear friend; their past matters little to me, if they wish sincerely to serve France and the Legitimacy. Republicans have written to me in Edinburgh; I accepted, as to their person, all they asked of me; but they wished to impose on me conditions of government, and I rejected them. I will never yield my principles; I wish to leave my grandson a throne more solidly founded than mine. Are the French any happier and freer today than they were under me? Do they pay less tax? What a milch cow France is! If I were permitted a fraction of the things permitted to Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans, what an outcry! What maledictions! They conspired against me, they confessed it: I chose to defend myself.’

The King paused as if embarrassed by the multitude of thoughts, and for fear of saying something that would offend me.

It was all very well, but what did Charles X understand by principles? Was he taking account of the cause of the conspiracies, true or false, hatched against his government? He resumed, after a moment’s silence: ‘How are your friends the Bertins? They have not protested on my behalf, you know: they are very harsh towards an exiled man, who did them no harm as far as I know. But, my dear friend, I wish none to anyone; everyone behaves according to his understanding.’

This sweetness of temperament, this Christian indulgence on the part of a King, hounded and slandered, brought tears to my eyes. I wanted to say a few words about Louis-Philippe. ‘Oh!’ the King responded. ‘Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans.he decided.what would you have? ...men are like that.’ Not a bitter word, not one reproach, not one complaint emerged from the lips of an old man three times exiled. And yet French hands had cut off his brother’s head and pierced his son’s heart; so implacable have those hands been for him in re-invoking the past!

I praised the King, great-hearted and compassionate of voice. I asked him if it had entered his mind to finish with all those secret correspondences, to dismiss all those agents who, for forty years, had deceived the Legitimacy. The king assured me that had resolved to put an end to those impotent machinations; he had already, he said, named several serious individuals, among whom I was one, to compose a sort of council in France fit to establish the truth. Monsieur de Blacas would explain it all to me. I begged Charles X to gather his followers and grant me a hearing: he referred me to Monsieur de Blacas.

I drew the King’s attention to the arrival of Henri V’s majority; I told him that a declaration made then would be useful. The King, who privately did not want such a declaration, invited me to present him with a draft. I replied with respect, but firmly, that I would never formulate a declaration at whose foot my signature did not appear below that of the King. My reason was that I did not wish to have placed to my account later changes introduced into some act by Prince Metternich and Monsieur de Blacas.

I suggested to the King that he was too far from France, that they would have time to carry out two or three revolutions in Paris before he could know of them in Prague. The King replied that the Emperor had left him free to choose his place of residence anywhere in the Austrian States, except the Kingdom of Lombardy. ‘But,’ His Majesty added, ‘the inhabitable cities in Austria are all much the same distance from France; in Prague I live rent-free, and my situation obliges me to take account of that.’

A noble calculation that for a Prince who for five years had enjoyed a civil list of twenty millions, without mentioning his royal residences; for a Prince who had left to France the Algerian colony and the ancient heritage of the Bourbons, worth twenty-five to thirty millions in revenue!

I said: ‘Sire, you loyal subjects have often thought that impoverished royalty might be in need; they are ready to contribute, each according to his wealth, in order to free you from dependence on a foreign power.’ – ‘I think, my dear Chateaubriand,’ said the King, smiling, ‘that you are scarcely richer than I. How did you pay for your journey?’ – ‘Sire, it would have been impossible for me to reach you, if Madame la Duchesse de Berry had not ordered her banker, Monsieur Jaugé, to advance me six thousand francs.’ – ‘That’s too little!’ cried the King, ‘do you need more?’ – ‘No, Sire; I ought rather to do the right thing, and return something to the poor prisoner; but I scarcely know how to economise.’ – ‘You were a magnificent Signor in Rome?’ – ‘I always consumed conscientiously whatever the King gave me; there are barely two sous left.’ – ‘You know that I still hold your Peer’s salary on your behalf: you did not want it.’ – ‘No Sire, because you have followers poorer than I. You resolved the matter of twenty thousand francs that remained of my debts as Ambassador with your great friend Monsieur Lafitte.’ – ‘I owed it to you,’ said the King, ‘you had not forgone your salary merely by resigning as Ambassador, which, by the way, did me harm enough.’ – ‘That’s as may be, Sire, owing to me or no, Your Majesty, by coming to my aid, did me a service at that time, and I will return the money when I can; but not at present, since I am poor as a rat; my house in the Rue d’Enfer is not paid for. I live any old how with Madame de Chateaubriand’s paupers, while waiting for those lodgings I have already visited, on behalf of Your Majesty, at Monsieur Gisquet’s. When I pass through a town, I first discover if there is a hospice; if there is one, I rest easy: board and lodging, what more does he need?’

‘– Oh, it shall not rest there. How much do you need, Chateaubriand, to be rich?’

‘– Sire, you would be wasting your time; you might give me four millions in the morning, and I would have not a groat by evening.’

The King patted my shoulder with his hand: ‘A fine thing! But what the devil do you do with your money?’ ‘Faith, Sire, I have no idea, for I’ve no vices and never spend anything: it’s incomprehensible! I am so foolish that on entering the Foreign Office I would not take the twenty-five thousand francs on a new appointment, and on leaving I scorned to pocket any profound secrets! You speak of my wealth, to avoid speaking of your own.’

‘It’s true,’ said the King, ‘here, in turn, is my confession: in consuming my capital in equal amounts year by year, I calculated that by the age I am now I would be able to live my life out without needing help from anyone. If I should find myself in any distress, I would prefer, as you suggest, to have recourse to Frenchmen rather than foreigners. They have offered me loans, among others one for thirty millions, which would be honoured in Holland; but I knew that such a loan, placed on the principal European markets, would devalue French funds; that prevented me endorsing the plan: nothing which would affect public wealth in France would suit me.’ Nobel sentiments expressed by a King!

In this conversation, one notes Charles X’s generosity of character, gentleness of manner, and commonsense. For a philosopher, it would have been a curious sight, that of a subject and a sovereign interrogating each other as to their wealth and making a mutual confession of their poverty in the depths of a Palace borrowed from the Kings of Bohemia!

Book XXXVII: Chapter 4: Henri V

Prague, the 25th and 26th of May 1833.

BkXXXVII:Chap4:Sec1

Emerging from this meeting, I attended Henri’s riding lesson. He rode two horses, the first trotting, without stirrups, the second executing with stirrups various turns, without holding the reins, and with a stick passed behind his back between his arms. The boy is daring and altogether elegant in his white breeches, jacket, little ruff, and cap. Monsieur O’Hegerty the elder, his riding instructor, shouted: ‘What’s with that leg there! It’s like a stick! Relax your leg! Good! Detestable! What’s the matter with you today? etc. etc. The lesson over, the young page-king reined in his horse in the middle of the riding school, and brusquely doffing his cap to salute me where I stood, in the gallery with Baron Damas and a few Frenchmen, leapt lightly and elegantly to the ground like a little Jehan de Saintré.

Henri is slender, agile, well made; he is blond; he has blue eyes with a look in his left one which recalls his mother’s gaze. His movements are brusque; he addresses you freely; he is curious and questioning; he has none of that pedantry the newspapers attribute to him; he is just a little boy like all little boys of twelve. I complimented him for his fine appearance on horseback: ‘You’ve seen nothing,’ he said to me, ‘you should see me on my black horse; he is a wicked devil; he kicks and throws me, I remount, we leap the fence. The other day, he knocked himself and his leg swelled up as big as that. Isn’t the horse I rode last a beauty? But I was not on form.’

Henri detests Baron Damas at the moment, whose appearance, character and ideas are antipathetic to him. He often becomes very angry with him. Following these fits of temper the Prince has to do penitence; he is sometimes condemned to remain in his room: a foolish punishment. Abbé Moligny comes to confess the rebel and tries to make him fear the devil. The obstinate lad chooses not to hear and refuses to eat. Then Madame la Dauphine reasons with Henri who eats and mocks the Baron. This form of education creates a vicious circle.

What Monsieur le Duc de Bordeaux lacks is a light hand which would lead him without his feeling the rein, a tutor who was his friend rather than his master.

If the race of Saint Louis was, like that of the Stuarts, a specific family driven out by revolution, and confined on an island, the destiny of the Bourbons would soon be something foreign to fresh generations. Our former royal power is not of that kind; it represents ancient royalty: the political, moral and religious past is born of that power and gathers around it. The fate of a race which was so involved in the social order as was, and so related to the social order which is to be, can never be a matter of human indifference. But any destiny that race was to endure, the situation of the individuals that formed it, and to whom an inimical fate could offer no respite, would be deplorable. In perpetual adversity, those individuals must travel in obscurity a course parallel to that of their family’s glorious past.

There is nothing sadder than the lives of fallen Kings; their days are no more than a tissue of reality and fiction: remaining sovereigns at their own hearth, among their servants and their memories, they no sooner cross the threshold of their home than they find ironic truth at the door: James II or Edward Stuart, Charles X or Louis d’Angoulême within, without they become James or Edward, Charles or Louis, without title, like those men of sorrows their neighbours; they have the dual inconvenience of living a Court life and a private life: the flattery, favouritism, intrigue and ambition of the one, the affronts, distress, and gossip of the other: it is a continuous masquerade with valets and ministers changing clothes. Moods are embittered by the situation, hopes weakened, regrets increased; the past is recalled; there are recriminations; there is self-reproach all the more bitter in that its expression is no longer surrounded by good taste derived of noble birth and the propriety of superior wealth; one becomes common through common suffering; the cares of a lost kingdom degenerate into the machinations of a household: Popes Clement XIV and Pius VI could never establish peace in the Pretenders’ ménages. Those un-crowned interlopers remained on guard in the midst of society, spurned by Princes as infected with adversity, suspect to nations as tainted by power.

‘Clement XIV (Ganganelli)’

History of the Jesuits: Their Origin, Progress, Doctrines, and Designs - Giovanni Battista Nicolini (p459, 1854)

Internet Archive Book Images

Book XXXVII: Chapter 5: Dinner and an evening at the Hradschin

BkXXXVII:Chap5:Sec1

I went off to dress: I had been warned that I could retain my frock coat and boots when dining with the King; but misfortune is too noble in rank for one to approach it with familiarity. I arrived at the Palace at a quarter to six; the table was laid in an ante-room. I found Cardinal Latil there. I had not met him since he had been my guest in Rome, at the Ambassador’s residence, during the meeting of the Conclave, after the death of Leo XII. What a change in my fate and that of the world between the two dates!

He was ever the priestling with rounded belly, pointed nose, and pallid visage, such as I had seen it, angered, in the Chamber of Peers, an ivory knife in his hand. It was said he had no influence and was fed in a corner while taking knocks; perhaps so; but there are other sorts of credit; that of a Cardinal is no less certain though hidden; he acquired it, this credit, through long years in residence with the King and from his character as a priest. The Abbé de Latil had been an intimate confidante; the memory of Madame de Polastron attached itself to the confessor’s surplice; the charm of his last human weakness and the sweetness of his first religious feeling endured in the old monarch’s heart.

Monsieur de Blacas, Monsieur Alfred de Damas, brother of the Baron, Monsieur O’Hegerty the elder, and Madame de Cossé arrived in succession. At six o’clock precisely the King appeared, followed by his son; they hastened to table. The King placed me on his left; he had Monsieur le Dauphin on his right; Monsieur de Blacas sat facing the King, between the Cardinal and Madame de Cossé; the other guests were distributed at random. The children only dine with their grandfather on Sundays: which is to deprive them of the only happiness that remains in exile, the intimacy of family life.

The dinner was meagre and quite poor. The King praised a fish from the Moldau to me, which was worthless. Four or five valets de chambre in black prowled about like lay brothers in a refectory; there was no maitre d’hôtel. Each took what was before him and offered it from the dish. The King ate well, asked for what he wished and himself served whatever he was asked for. He was in a good humour; any fear he may have had of me had passed. The conversation consisted of a round of commonplaces, on the Bohemian climate, the health of Madame la Dauphine, her journey, the celebration of Whit Sunday which would take place the following day; not a word of politics. Monsieur le Dauphin, his nose deep in his plate, occasionally emerged from his silence, and addressed Cardinal Latil: ‘Prince of the Church, was not the gospel for this morning according to St Matthew? – No, Monseigneur, according to St Mark. – What? St Mark?’ A grand dispute between St Mark and St Matthew, and the Cardinal was beaten.

Dinner lasted almost an hour; the King rose; we followed him to the salon. There were newspapers on a table; everyone sat down and began reading this and that as in a café.

The children entered, the Duc de Bordeaux led by his tutor, Mademoiselle by her governess. They ran to embrace their grandfather then sped towards me; we ensconced ourselves in a window seat with a superb view overlooking the city. I renewed my compliments on the riding lesson. Mademoiselle hastened to tell me once more what her brother had said to me, which I had not caught, namely that one could not come to a judgement since the black horse was lame. Madame de Gontaut came and sat with us, Monsieur de Damas nearby, lending an ear, in an amusing state of anxiety, as if I would eat his pupil, let fall some phrase concerning the freedom of the Press, or to the glory of Madame la Duchesse de Berry. I would have laughed at the fears I inspired in him, if I could have laughed at any poor wretch after Monsieur de Polignac. Suddenly Henri said to me: ‘Have you seen any diviner’s snakes?’ – ‘Monseigneur must mean boa constrictors: there are none in Egypt nor at Tunis the only places in Africa I have visited; but I saw plenty of snakes in America.’ – ‘Oh, yes’, said Princess Louise, ‘the rattlesnake, in the Génie du Christianisme.’

I bowed to Mademoiselle, in thanks. ‘But you have seen other snakes?’ Henri continued. ‘Are they very nasty?’ – ‘Some of them, Monseigneur, are very dangerous others have no venom and can be taught to dance.’

The two children drew close to me in delight, fixing their fine bright eyes on mine.

‘And then there are glass-snakes,’ I said. ‘They are superb and not harmful; they have the transparency and fragility of glass; they shatter when they are touched.’ – ‘Can the pieces not be joined together again?’ said the Prince. – ‘No, brother’, Mademoiselle replied for me. – ‘You went to Niagara Falls?’ Henri continued. ‘Was there a terrible roaring? Can you go down it in a boat?’ – ‘Monseigneur, an American delighted in launching himself down it in a large canoe; another American, they say, threw himself into the cataract; he did not perish the first time, but he tried again and was killed at the second attempt.’ The two children raised their hands and cried: ‘Oh!’

Madame de Gontaut spoke: ‘Monsieur de Chateaubriand has been to Egypt and Jerusalem,’ Mademoiselle clapped her hands and drew near me again. ‘Monsieur de Chateaubriand’, she said, ‘tell my brother about the Pyramids and the Tomb of Our Lord.’

As best I could I told them about the Pyramids, the Sacred Tomb, the Jordan and the Holy Land. The children’s attentiveness was striking: Mademoiselle cupped her pretty face in her hands, her elbows almost resting on my knees, and Henri, perched on a tall chair, wriggled, his legs dangling.

After this fine conversation on serpents and cataracts, pyramids and the Holy Tomb, Mademoiselle said: ‘Will you ask me a history question?’ – ‘So, history is it?’ – ‘Yes, question me about a year, the most obscure year in the whole history of France, except the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries which we have not started yet.’ – ‘Oh’, cried Henri, ‘I prefer a famous year: ask me something about a famous year.’ He was less sure of the matter than his sister.

I began by obeying the Princess and said: ‘Well, can Mademoiselle tell me what was happening and who ruled France in 1001?’ Behold brother and sister thinking, Henri clutching his cheek, Mademoiselle covering her face with her hands, in a manner customary with her, as if she were playing hide and seek, then she suddenly revealed her youthful happy expression, her lips smiling, her gaze limpid. She was the first to reply: ‘It was Robert who reigned, Gregory V was Pope, Basil III Emperor of the East.’ – ‘And Otto III was Western Emperor’ cried Henri desperate not to be left behind by his sister, and he added: ‘Veremond II in Spain.’ Mademoiselle cutting him short said: ‘Ethelred in England.’ – ‘Not at all,’ said her brother, ‘it was Edmund Ironside.’ Mademoiselle was right; Henri was wrong by a few years favouring Ironside who delighted him; but it was no less remarkable.

‘What of my famous year, then?’ Henri asked in a half-angry tone. – ‘That’s right, Monseigneur: what happened in 1593?’ – ‘Bah’, cried the young Prince. ‘That was Henri IV’s recantation.’ Mademoiselle blushed at not being able to answer first.

‘Henri IV’

The Last of the Valois (Henry III), and accession of Henry of Navarre 1559-1589, Vol 02 - Lady Catherine Charlotte Jackson (p225, 1888)

The British Library

Eight o’clock struck: the voice of Baron de Damas cut short our conversation, as the hammer of the timepiece, striking ten, once suspended my father’s paces in the great hall of Combourg.

Sweet children! The old crusader related his adventures in Palestine to you, but not by the hearth of Queen Blanche’s castle! To find you, he came to tread an icy foreign threshold, with his palm branch and his dusty sandals. Blondel sang in vain at the foot of the tower of the Dukes of Austria; his voice could not re-open the gates of your country to you. Young exiles, the voyager in distant lands has hidden from you a part of his story; he has not told you that, poet and prophet, he crossed the wilds of Florida and the mountains of Judea with as much desperation, sadness and passion as you possess of hope, joy, and innocence; that there was a day when, like Julian, he sent his blood towards Heaven, blood of which the God of Mercy kept a few drops, to purchase those he had delivered to the god of curses.

The Prince, led away by his tutor, invited me to his history lesson, set for the Sunday, at eleven in the morning; Madame de Gontaut withdrew with Mademoiselle.

Then another kind of scene commenced: future royalty, in the person of a child, had just involved me in his games; past royalty, in the person of an old man, now had me attend on his. A Whist party was begun, illuminated by two candles in the corner of a dark room, between the King partnering the Dauphin, and the Duc of Blacas partnering Cardinal Latil. I was the only spectator except for O’Hegerty the riding instructor. Through the open window-shutters twilight mingled its pallor with that of the candle-light: the monarchy waned between those two expiring flames. A profound silence reigned, except for the fall of the cards and an occasional annoyed exclamation from the King. Playing cards were modelled on those of the Latins to enliven Charles VI’s adversity, but under Charles X there was no longer an Ogier or a Lahire to give their names to these distractions of misfortune.

The game over, the King wished me goodnight. I passed by the empty sombre rooms I had traversed the previous day, the same stairs, the same guards, and descending the terraces of the hill, regained my inn despite getting lost among the night-time streets. Charles X remained shut in the dark mass of buildings I had left behind me: nothing could convey the melancholy of his isolation and his years.

Book XXXVII: Chapter 6: Visits

Prague, the 27th of May 1833.

BkXXXVII:Chap6:Sec1

I greatly needed a rest; but Baron Capelle, arriving from Holland, took a room next to mine, and was in haste.

‘G.-A.-B., Baron Capelle, 1775-1845, Copie d'un Tableau à l'Huile de Robert Fleury’

Bulletin - Institut National Genevois (p212, 1852)

Internet Archive Book Images

When a torrent falls from a great height, the abyss it creates and by which it is swallowed draws the gaze and renders us dumb; but I have neither patience with nor pity for Ministers whose foolish hands allowed Saint Louis’ crown to fall into the gulf, as if the waves would return it! Those Ministers who claim to be opposed to the decrees are the most culpable; those who say they have been the most moderate are the least innocent; if they saw so clearly, why did they not resign? ‘They did not wish to desert the King; Monsieur le Dauphin would have considered them cowards.’ A poor excuse; they could not tear themselves away from their portfolios. Whatever they may say, nothing else was at the root of that immense disaster. And what superb tranquillity since the event! One of them scribbles a History of England, after having neatly settled the history of France; another mourns the life and death of the Duc de Reichstadt, having despatched the Duc de Bordeaux to Prague.

I knew Monsieur Capelle: it is right to remember that he was left impoverished; his claims did not exceed his worth; he would willingly have said like Lucian: ‘If you read me in hopes of breathing amber and hearing the song of the swans...I swear by the gods I have never spoken in such an elevated strain.’ These days modesty is a rare enough virtue, and Monsieur Capelle’s only mistake was being made a Minister.

I received a visit from Monsieur le Baron de Damas: the virtues of that brave officer had gone to his head; religious congestion had addled his brains. He makes fateful alliances: the Duc de Rivière on his deathbed recommended Monsieur de Damas as the Duc de Bordeaux’s tutor; the Prince de Polignac was a member of that set. Incapacity is a kind of Freemasonry with lodges in every land; its delving creates pits from which shafts lead, into which States vanish.

Domesticity is so natural at Court that Monsieur de Damas, in selecting Monsieur de Lavillate, decided to grant him no title but that of First Valet of the Chamber to Monseigneur le Duc de Bordeaux. On first meeting, I took a liking to this military man with greying teeth, a faithful mastiff, charged with barking at the sheep. He belonged to that troop of loyal grenade-bearers whom the terrifying Marshal de Montluc esteemed, and of whom he said: ‘There’s nothing of the back-office about them.’ Monsieur de Lavilatte will be dismissed for his sincerity not his brusqueness: barrack room brusqueness can be tolerated; often adulation in camp swells an independent character’s pride. But with the old soldier of whom I speak it was merely frankness; he would have redeemed his moustache with honour, if he had borrowed thirty thousand piastres against them as Juan de Castro did. His forbidding expression was simply that of liberty; his manner merely warned that he was prepared. Before putting their army in the field, the Florentines warned the enemy by ringing the bell called Martinella.

Book XXXVII: Chapter 7: Mass – General Skrzynecki

Prague, the 27th of May 1833.

BkXXXVII:Chap7:Sec1

I had formed the intention of hearing Mass in the Cathedral, in the precincts of the Palace; detained by visitors, I only had time to visit the basilica of the erstwhile Jesuits. There was singing accompanied by an organ. A woman, near me, possessed a voice whose tones made me turn my head. At the moment of Communion, she covered her face with both hands and did not go up to the altar table.

‘Prague Royal Castle’

Malebné Cesty po Praze - Edvard Herold (p13, 1884)

The British Library

Alas! I have explored so many churches in the four corners of the globe, without ridding myself, even at the Saviour’s tomb, of the rough hair-shirt of my thoughts. I described Aben-Hamet wandering in the Christian mosque at Cordoba: ‘He glimpsed a motionless figure at the base of a pillar, which he at first mistook for a statue on a tomb.’

The original of the knight Aben-Hamet glimpsed was a monk I encountered in the church of the Escorial, whose faith I envied. Yet who knows the tempests in the depths of that meditative soul, or what pleas rose towards the Holy and Innocent Pontiff? I had just admired, in the empty sacristy of the Escorial, one of Murillo’s loveliest Virgins; I was with a lady; she was first to point out to me this monk deaf to the sound of the passions that passed before him in the sanctuary’s tremendous silence.

After Mass in Prague I looked for a calash: I took the road laid out among the old fortifications by which carriages climbed to the Palace. Gardens were being created on the ramparts: the harmonious sound of the trees will replace the din of the Battle of Prague: all will be delightful in forty years or so: may it be hoped that Henri V will not remain here long enough to enjoy the shade of their unborn leaves!

Before dining next day at the tutor’s, I thought it would be polite to go and visit Countess Choteck: I would have found her charming and beautiful, even if she had not quoted passages of my writings from memory.

I went to Madame de Guiche’s in the evening: there I met General Skrzynecki and his wife. He gave me an account of the Polish Insurrection and the battle of Ostrolenka.

When I rose to leave, the General asked permission to shake my venerable hand and embrace the patriarch of liberty and the Press; his wife wished to embrace me as the author of the Génie du Christianisme; the monarchy generously received a fraternal kiss from the republic. I experienced the satisfaction due an honest man; I was happy to waken a variety of titles to noble sympathy in the hearts of strangers, to be pressed to the breast of husband and wife in turn for the sake of liberty and religion.

On Monday the 27th, in the morning, the opposition came to inform me I would not be seeing the young Prince: Monsieur de Damas had tired his pupil, dragging him from church to church obeying the stations of the Jubilee. That exhaustion served as pretext for a holiday and motivated a course of action: they would hide the boy from me.

I employed the morning wandering around the city. At five I went to dine with Count Choteck.

Book XXXVII: Chapter 8: Dinner at Count Choteck’s

BkXXXVII:Chap8:Sec1

Count Choteck’s mansion, built by his father (who was also Supreme Burgrave of Bohemia) has the external appearance of a Gothic chapel; nothing is original these days, everything is copied. From the drawing room there is a view of the gardens; they slope downwards into a valley: the light is always insipid, a greyish sun as in the rocky depths of the Northern mountains where gaunt Nature wears a hair shirt.

The table was set in the pleasure-ground, beneath the trees. We dined hatless: my head, which so many storms have insulted while carrying off my hair, was sensitive to the sighs of the breeze. While I tried to do justice to the meal, I could not prevent myself from watching the birds and the clouds flying above our feast; travellers embarked on the winds and secretly connected to my destiny; voyagers, the objects of my envy, whose aerial flight my gaze cannot follow without a kind of tenderness. I was more akin to those intruders wandering the skies than the earthbound guests sitting beside me: happy those anchorites who had a crow to serve them their food!

I cannot tell you about Prague society, since I only experienced it at this dinner. There was a lady there much in vogue in Vienna, and very spiritual they assured me; she seemed bitter and foolish, though there was still something youthful about her, like those trees in summer that retain the dried fruit from flowers they bore in the spring.

Thus I only know the manners of that country as they were in the sixteenth century, as recounted by Bassompierre: he was in love with Anna-Esther, aged eighteen, widowed six months previously. He spent five days and six nights, in disguise, concealed in a room with his mistress. He played court tennis with Wallenstein at the Hradschin. Being neither Wallenstein nor Bassompierre, I pretended neither to empire nor love: modern Esthers want an Ahasueras who can, disguised though he may be, rid himself of his domino at night: one cannot lay aside the mask of the years.

‘François de Bassompierre’

An Address to the Good Sense and Candour of the People, in Behalf of the Dealers in Corn - Sir Thomas Turton (p256, 1800)

The British Library

Book XXXVII: Chapter 9: Whit Sunday – The Duc de Blacas

Prague, the 27th of May 1833.

BkXXXVII:Chap9:Sec1

Leaving the dinner, at seven, I went to see the King; there I found the same people as on the previous day, except for Monsieur le Duc de Bordeaux, who they said was suffering from his Sunday exertions. The King was reclining on a sofa, and Mademoiselle was sitting on a chair at Charles X’s knee, he stroking his grand-daughter’s arm while telling her stories. The young Princess listened attentively: when I appeared, she looked at me with a smile, like a person saying in a rational way: ‘Really, I must amuse grand-papa.’

‘Chateaubriand,’ cried the King, ‘I did not see you yesterday?’ – ‘Sire, I was advised too late that Your Majesty had done me the honour of inviting me to dinner: and then, it was Whit Sunday, a day on which it is not permitted me to see Your Majesty.’ – Why is that?’ said the King. ‘Sire, it was on Whit Sunday, nine years ago, that on presenting myself to pay my court to you, they forbade my entrance.’

Charles X appeared moved: ‘No one will drive you from the Palace in Prague.’ – ‘No, Sire, since I see none of those faithful servants here, who dismissed me in the days of prosperity.’ Whist commenced, and the day ended.

Following the game I returned the Duc de Blacas’ visit. ‘The King tells me we should talk,’ he said. I replied that the King not having judged it appropriate to convoke his council before whom I would have been able to develop my ideas on the future of France and the Duc of Bordeaux’s coming of age, I had nothing to say. ‘His Majesty has no council’, monsieur de Blacas replied with a tremulous laugh, his eyes full of self-satisfaction, ‘there is only myself, myself alone.’

The Grand Master of the Wardrobe had the highest opinion of himself: a French malady. To listen to him, he has done everything, he can do anything; he arranged the Duchesse de Berry’s marriage; he disposes of kings; he leads Metternich by the nose; he has Nesselrode by the throat; he rules Italy; his name is engraved on an obelisk in Rome! He has the keys of the Conclave in his pocket; the last three Popes owe their exaltation to him; he is so knowledgeable about public opinion, he tailors his ambition to his abilities so well, that through attending on Madame la Duchesse de Berry, he was presented with a diploma naming him Chief Councillor to the Regency, First Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs! And this is how those poor wretches understand France and the century.

Yet Monsieur Blacas is the most intelligent and moderate of that crowd. In conversation he is reasonable: he is always of your opinion: You think so! That’s precisely what I was saying yesterday. We have exactly the same idea! He complains of his servitude; he is weary of affairs, he would like to live in some unknown corner of the earth, to die there at peace with the world. As for his influence over Charles X, don’t speak of it; people imagine he controls Charles X: what error! He can do nothing with the King! The King will not listen; the King refuses something in the morning; in the evening he agrees it, without knowing why he has changed his mind, etc. While it is Monsieur de Blacas who tells you this nonsense, it is true, because he never thwarts the King; but he is not sincere, because he only inspires in Charles X wishes which agree with that Prince’s inclinations.

For the rest, Monsieur de Blacas has courage and honour; he is not without generosity; he is loyal and devoted. In assuming high aristocracy and entering into riches, he has taken on their allure. He is very well born; he came from a poor but ancient house, known for poetry and warfare. His stiff manner, his aplomb, and his rigorous sense of etiquette have preserved for his masters that nobility which can easily be lost in adversity: at least, in the Museum that is Prague, inflexible armour holds upright a body which would otherwise fall. Monsieur de Blacas does not lack a certain amount of energy; he handles business affairs expeditiously; he is ordered and methodical. A connoisseur, well-versed in various branches of archaeology, an amateur of the arts with no imagination, and an icy libertine, he is not stirred even by his own passions: his sang-froid would be an attribute of the Statesman, if his sang-froid were other than his confidence in his own genius, and his genius betrays his confidence: one senses in him a great lord aborted, as one feels with his compatriot La Valette, Duc d’Épernon.

Whether there is a Restoration or no; if there is to be a Restoration Monsieur de Blacas returns with titles and honour; if there is not, the fate of the Grand Master of the Wardrobe lies outside France completely; Charles X and Louis XIX will die; he will be old, that is Monsieur de Blacas; his children will remain companions to the exiled Prince, illustrious visitors to foreign courts. God be praised for everything!

Thus the Revolution, which elevated and destroyed Bonaparte, enriches Monsieur de Blacas: that is some compensation. Monsieur de Blacas, with his long immobile and colourless face, is the contractor of funeral pomp to the monarchy; he buried it at Hartwell, he buried it at Ghent, he re-buried it in Edinburgh and will bury it again in Prague, or elsewhere, always watching over the spoils of the high and noble dead, as the peasants on the coast gather shipwrecked objects that the sea throws on their shores.

Book XXXVII: Chapter 10: DIGRESSIONS: A description of Prague – Tycho Brahe - Perdita

Prague, the 28th and 29th of May 1833.

BkXXXVII:Chap10:Sec1

On Tuesday, the 28th of May, the history lesson at which I was to be present, at eleven, not taking place, I found myself free to wander or rather review the city which I had already seen more than once in my coming and going.

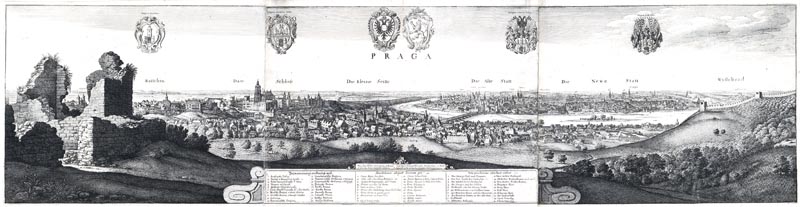

I do not know why I imagined Prague as nestling in a gap in the mountains casting dark shadows over a cauldron of houses: Prague is a smiling city overlooked by twenty-five to thirty elegant towers and steeples; its architecture recalls a Renaissance town. The lengthy domination of the Emperors over Cisalpine countries has filled Germany with artists from those countries; the Austrian villages are villages of Lombardy, Tuscany or the drier parts of Venice; you would think yourself in a region of Italy, if, in the farms with their great bare rooms, a stove did not replace the sun.

‘The Great View of Prague’

Wenceslaus Hollar (1649)

National Gallery of Art - Open Access

The view from the Palace windows is very pleasant; on one side you can see orchards in a cool valley with green slopes, enclosed by the city battlements, which fall to the Moldau, rather as the walls of Rome descend from the Vatican to the Tiber; on the other side, you discover the city itself traversed by the river, the river adorned upstream by an island with plantations, and embracing an isle downstream in leaving behind the northern suburbs. The Moldau flows into the Elbe. A boat taking me on board at the Prague Bridge could land me by the Pont-Royal in Paris. I am not the work of centuries and kings; I have neither the weight nor the duration of the obelisk that the Nile is sending to the Seine at this very moment; to tow my galley the sash of the Tiber Vestal would suffice.

The bridge over the Moldau, built in wood in 795 by Mnata was, at various times, rebuilt in stone. While I took the bridge’s measure, Charles X walked by on the pavement; he carried an umbrella under his arm; his son accompanied him like a hired cicerone. I said in the Conservateur that they went to the window to watch the monarchy pass by: I saw it pass by on the bridge in Prague.

In the buildings that compose the Hradschin Palace, you can view the historic rooms of a museum hung with the restored portraits and burnished weapons of the Dukes and Kings of Bohemia. Not far from the formless mass a pretty building is outlined against the sky adorned with one of those elegant cinquecento porticos: its architecture has the disadvantage of being at odds with the climate. If only one could slide those Italian palaces into a warm greenhouse with palm trees, during the Bohemian winter. I was always preoccupied with the idea of how cold they must be at night.

Prague, often besieged, taken and re-taken, is known to us militarily by the battle of that name and by the retreat in which Vauvenargues found himself involved. The city boulevards have been demolished. The Palace moats, on the side of the elevated plain, form deep straight notches planted with poplars. At the time of the Thirty Years War, these moats were full of water. The Protestants, entering the Palace on the 23rd of May 1618, flung two Catholic lords and the Secretary of State from the windows: the three swimmers were rescued. The Secretary, knowledgeable about human kind, asked a thousand pardons of one of the lords for having the misfortune to fall on top of him. In this month of May 1833, no one is quite so polite: I know only too well what I would have said in similar case, I who have moreover been a Secretary of State.

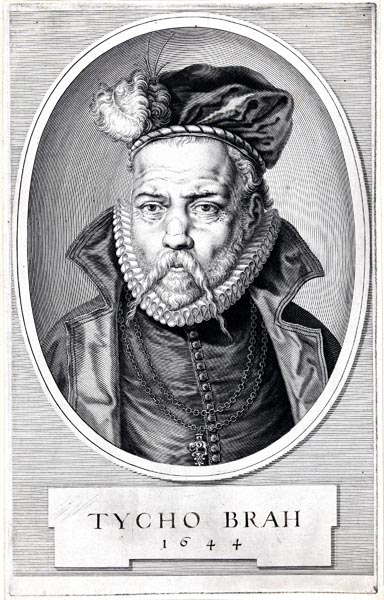

Tycho Brahe died in Prague: would you, for all his science, want a false nose of leather or silver like his? Tycho consoled himself in Bohemia, like Charles X, by contemplating the heavens; the astronomer admired their workings, the King adored their maker. The star which appeared in 1572 (fading out in 1574) which altered successively from brilliant white to the yellowish-red of Mars to the leaden white of Saturn, offered Tycho’s observations the spectacle of a world consumed by fire. What was the Revolution whose blast blew Louis XVI’s brother to the tomb of the Danish Newton compared with the destruction of a globe, accomplished in less than two years? General Moreau came to Prague to concoct a Restoration with the Emperor of Russia which he, Moreau, would never see.

‘Portrait of Tycho Brahe’

Jeremias Falck (1644)

The Rijksmuseum

If Prague was beside the sea nothing would be more delightful; as Shakespeare struck Bohemia with his wand and made it a maritime country:

‘Thou art perfect then,’ says Antigonus to a mariner, in The Winter’s Tale, ‘our ship hath touch’d upon the deserts of Bohemia?’

Antigonus lands, charged with exposing to the elements a little girl to whom he addresses these words: ‘Blossom, speed thee well! ...The storm begins. Thou’rt like to have a lullaby too rough!’

Does it not seem as if Shakespeare has recounted in anticipation the history of Princess Louise, that young blossom; that new Perdita; transported to the deserts of Bohemia?

Book XXXVII: Chapter 11: MORE DIGRESSIONS: Of Bohemia – Slavic and Neo-Latin Literature

Prague, the 28th and 29th of May 1833.

BkXXXVII:Chap11:Sec1

Confusion, blood, catastrophe, that is Bohemia’s history; its dukes and its kings, embroiled in civil and foreign wars, struggled with their subjects, or grappled with the dukes and kings of Silesia, Saxony, Poland, Moravia, Hungary, Austria and Bavaria.

During the reign of Wenceslas VI, who roasted his cook because he grilled a hare badly, Jan Huss appeared, who having studied at Oxford, imported Wycliffe’s doctrines. The Protestants, who search everywhere for ancestors without finding any, report that from the heights of his pyre Jan sang, prophesying the coming of Luther.

‘The world full of bitterness,’ says Bossuet, ‘bore Luther and Calvin, whose teachings spread throughout Christendom.’

The Christian and Pagan conflicts, Bohemia’s precocious heresies, the import of foreign interests and foreign manners, resulted in a state of confusion favourable to tricksters. Bohemia passed for a land of sorcerers.

The ancient poems, discovered in 1817 by Monsieur Hanka, the librarian of the Prague museum, in the church archives of Königinhof, are celebrated. A young man I am delighted to cite, the son of an illustrious scholar, Monsieur Ampère, has communicated the spirit of these songs, while Celakowsky has given us many popular songs in the Slavic idiom.

‘Ampère’

Caractères Phrénologiques et Physiognomoniques des Contemporains les Plus Célèbres, Selon les Systèmes de Gall, Spurzheim, Lavater, etc. - Théodore Poupin (p384, 1837)

Internet Archive Book Images

Poles find the Bohemian dialect effeminate; it is a quarrel between the Dorian and the Ionic. A Breton from Vannes considers a Breton from Tréguier a barbarian. The Slavic like the Magyar lends itself to endless imitation: my poor Atala was dressed in a robe of Hungarian embroidery (Point de Hongrie); she also wore an Armenian dolman and an Arab veil.

Another kind of literature has flourished in Bohemia, a modern Latin literature. The Prince of this literature, Bohuslas Hassenstein, Baron Lobkowitz, born in 1462, taking ship at Venice in 1490, visited Greece, Syria, Arabia and Egypt. Lobkowitz preceded me to those celebrated places by three hundred and sixteen years, and like Lord Byron he sang of his pilgrimage. With what different spirits, hearts, thoughts and manners have we meditated, more than three centuries apart, on the same ruins and the same sunlight, Lobkowitz the Bohemian; Lord Byron the Englishman; and I a child of France!

At the time of Lobkowitz’s voyage, marvellous monuments, now overthrown, were still standing. It must have been an astonishing sight that of the Barbarians in all their power, civilisation laid low beneath their feet, the Janissaries of Mehmed II intoxicated with opium, victory and women, scimitars in hand, brows festooned with blood-stained turbans, lined up for the assault on the ruins of Egypt and Greece: and I saw the same barbarians, among those same ruins, struggling beneath the march of civilisation.

In wandering the city and suburbs of Prague, the things I have just said printed themselves on my mind, as pictures from a projector do on a screen. But, whichever corner I found myself in, I could still see the Hradschin, and the King of France leaning from the windows of that Palace, like a phantom overlooking all those shades.

Book XXXVII: Chapter 12:I take leave of the King – Farewells – A letter from the children to their mother – A Moneychanger – The Saxon servant

Prague, the 29th of May 1833.

BkXXXVII:Chap12:Sec1

My review of Prague over, I went to dine at the Palace on the 29th of May at six o’clock. Charles X was in good humour. On leaving the table, and occupying a sofa in the sitting-room, he said: ‘Chateaubriand, did you know that the National, which arrived this morning, claims that I had the right to issue my decrees?’ – ‘Sire,’ I replied, ‘Your Majesty can throw stones at me with impunity.’ – The King, unsure, hesitated; then taking up the case: ‘I have taken a certain matter to heart: you mistreated me devilishly badly in the first part of your speech to the Chamber of Peers.’ Then the King suddenly cried, without allowing me time to respond: ‘Oh! It’s finished! It’s finished! ...An empty tomb at Saint-Denis. That’s fine! ...Very well! Very well! ...Let’s speak of it no more. I did not wish to hang on to it. It’s over. It’s done with.’ And he excused himself for having dared chance those few words.

I kissed the Royal hand with pious respect.

‘Let me say to you’ Charles X continued, ‘that I may have been wrong not to defend myself at Rambouillet; I still had great resources.but I did not wish bloodshed on my behalf; I abdicated.’

I did not challenge that noble excuse; I replied:

‘Sire, Bonaparte twice abdicated like Your Majesty, in order not to prolong the ills of France.’ Thus I sheltered my King’s weakness behind Napoleon’s glory.

The children entered, and approached us. The King spoke of Mademoiselle’s age: ‘Now, little scrap,’ he cried, ‘you are fourteen already! – ‘Oh to be fifteen!’ said Mademoiselle. – ‘Well, what will you do then?’ said the King. Mademoiselle remained silent.

Charles X spoke of something: ‘I don’t remember that,’ said the Duc de Bordeaux.’ – I know, said the King, it happened the very day you were born. – ‘Oh,’ replied Henri, ‘a long time ago then!’ Mademoiselle leaning her head on his shoulder a little, raising her face towards her brother, said with a little ironic glance: ‘You were born a long time ago then?’

The children withdrew; I saluted the orphan: I was to leave that night. I said goodbye to him in French, English and German. How many languages will Henri learn in which to recount his wretched wanderings, and ask for bread and sanctuary from a stranger?

When the whist party began, I had my orders from His Majesty. ‘Go and see Madame la Dauphine in Carslbad, said Charles X. Farewell, My dear Chateaubriand. We shall have news of you from the papers.’

I went from door to door offering my last respects to the inhabitants of the Palace. I saw the young Princess again with Madame de Gontaut; she gave me a letter for her mother at the end of which were written a few lines from Henri.

I was to leave on the 30th at five in the morning; Count Choteck had the kindness to have horses ordered for the journey: a mishap delayed me till midday.

I was carrying a letter of credit for two thousand francs payable at Prague; I presented myself at the house of a plump little Jew who gave cries of admiration on seeing me. He called his wife to help; she hurried in, or rather rolled to my feet; she sat down, short, dark and fat, opposite me, her arms like wings, gazing at me wide-eyed: if the Messiah had entered through the window, this Rachel could not have looked more joyous; I thought I might be threatened with a cry of Hallelujah! The money-changer offered me his fortune, letters of credit for the whole extent of the Israelite diaspora; he added that he would send the two thousand francs to my hotel.

The sum was not available on the evening of the 29th; on the morning of the 30th, when the horses were already harnessed, a clerk arrived with a parcel of bills, paper from various sources, which was discounted more or less on the spot, and which was useless outside the Austrian States. My account was detailed on a note which showed against the balance, in good coin. I was dumbfounded: ‘What do you expect me to do with this?’ I asked the clerk. ‘How am I to pay for the horses and the cost of the inns with this?’ The clerk ran off to obtain an explanation. Another clerk came, and carried out endless calculations for me. I sent the second clerk away; a third brought me Brabant gold-pieces. I left, on my guard against the tenderness I might inspire, in future, in the daughters of Jerusalem.

My calash was surrounded, under the archway, by the hotel staff, among whom was one pretty Saxon girl who played a piano, whenever she had the chance between chimes of the bell: try asking some Leonard in Limousin or Fanchon in Picardy to play Tanti palpati or Moses’ Prayer for you on the piano, or sing them!

Book XXXVII: Chapter 13: What I left behind in Prague

Prague and en route, the 29th and 30th of May 1833.

BkXXXVII:Chap13:Sec1

I entered Prague with great apprehensions. I said to myself: ‘For us to fail it only needs God to place our fate in our own hands; God works miracles on behalf of men, but he entrusts their conduct to themselves, else he would be running the world in person: now, men can abort the fruit of these miracles. Sin is not always punished in this world; errors always are. Sin belongs to Mankind’s common and eternal nature; Heaven alone knows the truth, and sometimes reserves the right to punish. Faults of a limited and accidental nature are within the competence of the world’s narrow justice; that is why it is possible that the monarchy’s recent errors will be severely punished by mankind.’

I said to myself further: ‘Royal families have fallen into irreproachable error through being infatuated with a false understanding of their own nature: they sometimes view themselves as families do who are mortal and private; as occasion demands they place themselves above the common law or inside the boundaries of that law. Have they violated the political constitution? They cry that they have the right, that they are the source of the law, that they cannot be judged by ordinary rules. Do they choose to commit a domestic fault, for example to provide the heir to the throne with a dangerous education? Their reply to criticism: “A private person can act as they wish towards their children, and we cannot!”

Well, no, you cannot! You are neither a divine family nor a private family; you are a public family; you belong to society. Royal errors do not harm royalty alone; they are damaging to the whole nation: a King makes a mistake and departs; but can the nation depart? Can it feel no pain? Do not those who remain attached to absent royalty, victims of their sense of honour, find their careers interrupted, their relatives hounded, their liberty constrained, and their existence threatened? Again, royalty is not in private ownership, it is common property, undivided, and third parties are involved in the fate of the throne. I fear that in the troubled situation inseparable from misfortune royalty has not understood these realities and has done nothing to permit its return at an advantageous moment.

Another point: while recognising the immense advantages of the Salic Law, I do not deceive myself that the longevity of a race has serious disadvantages for nations and kings: for nations, because it links their destiny to that of their kings; for kings, because unending power intoxicates; they lose their sense of reality; everything which is not brought to their altar as suppliant prayer, humble wish, deep abasement, is impiety. Misfortune teaches them nothing; adversity is merely a plebeian coarseness lacking in respect, and disaster for them is merely insolence.’

Happily I was in error: I found that Charles X had not fallen into the noble errors born of high society; I simply found him mired in the common illusions that attend on unexpected accident, and which are more understandable. Everything serves to solace the self-esteem of Louis XVIII’s brother: he sees his political world destroyed, and attributes that destruction rightly to his epoch, not his person: did not Louis XVI perish? Did not the Republic fall? Was not Bonaparte twice constrained to abandon the theatre of glory did he not die a prisoner on an island? Are not the thrones of Europe threatened? What more then could he, Charles X, do than these fallible powers? He wished to defend himself against his enemies; he was alerted to danger by the police and symptoms of public unrest; he took the initiative; he attacked in order not to be attacked. Have not the heroes of the Three Days’ riots confessed that they conspired, that they had been playing out a comedy for fifteen years? Well! Charles thought it a duty to make an effort; he tried to save the French Legitimacy and with it the European Legitimacy: he engaged in battle, and he lost; he sacrificed himself to save the monarchy that is all. Napoleon had his Waterloo, Charles X his July Days.

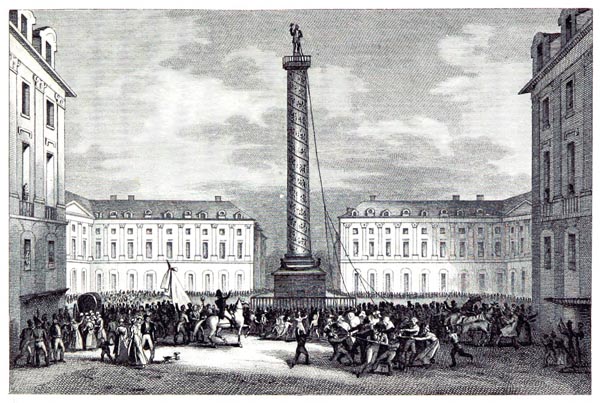

‘Les Royalistes et la Colonne’

Histoire de la Révolution Française Depuis 1814 Jusqu'à 1830...Revue et Continuée par M. Auguis, Vol 01 - Jacques Antoine Dulaure (p137, 1838)

The British Library

So things presented themselves to the unfortunate monarch; he remained immutable, waiting on events which abased and humbled his spirit. Through a refusal to be moved, he attains a certain amount of grandeur: a man of imagination, he listens to you, he is not angered by your ideas: he has the air of entering into them, without entering into them at all. General axioms one sets in front of oneself like gabions; sheltering behind them, one fires on the intellects that march by.

The mistake many people make is to be persuaded, if events recur in history, that the human race is still in a primitive state; they confound passions and ideas: the former are the same in all centuries, the latter change with successive ages. Though the material effects of various actions are the same at various epochs, the causes which produce them are different.

Charles X considers himself a principle, and indeed there are men who, through living according to fixed ideas, identical from generation to generation, are no more than monuments. Certain individuals, through the lapse of time and their preponderance, become things transformed into people; the individuals perish when the things perish: Brutus and Cato were each the Roman Republic incarnate; they could not survive its destruction, no more than the heart can keep beating when exhausted of blood.

I have painted a portrait of Charles X elsewhere:

‘You have observed this faithful subject, for six years, this respectful brother, this tender father, so greatly afflicted by the death of one of his sons, so greatly consoled by the other! You know him, this Bourbon, noble heir of old France, the first to arrive after our misfortunes to set himself between you and Europe, a lily stem in his hand! Your eyes rest with love and kindness on this Prince, who, in middle age, has retained the charm and elegance of youth, and who now, decked with the crown, is still merely one more Frenchman among you! You repeat with emotion so many happy phrases uttered by this new monarch, who derives his grace in speaking from the loyalty of his heart!