François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book VII: Travels in New York State 1791

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book VII: Chapter 1: Journey from Philadelphia to New-York and Boston - Mackenzie

- Book VII: Chapter 2: The Hudson River – A passenger’s recital – Mr Swift – Departure for Niagara Falls with a Dutch guide – Monsieur Violet

- Book VII: Chapter 3: My savage outfit– Hunting– The Carcajou or Wolverine– The Muskrat – Water dogs – Insects – Montcalm and Wolfe

- Book VII: Chapter 4: Encampment by the Lake of the Onondagas – Arabs – The Indian and the cow

- Book VII: Chapter 5: An Iroquois – The Sachem of the Onondagas – Velly and the Franks – A ceremony of hospitality – The Ancient Greeks

- Book VII: Chapter 6: Journey from the Lake of the Onondagas to the River Genesee – Bees – Clearings – Hospitality – A bed – A rattlesnake charmed by a flute

- Book VII: Chapter 7: An Indian Family – Night in the forest – The family departs – The savages of Niagara Falls – Captain Gordon – Jerusalem

- Book VII: Chapter 8: Niagara Falls – A rattlesnake – I fall over the edge of the gorge

- Book VII: Chapter 9: Twelve days in a cabin – Changing customs among the savages – Birth and death – Montaigne – Song of the adder – The little Indian girl, the original of Mila

- Book VII: Chapter 10: DIGRESSIONS - Ancient Canada – The Indian population – The decline of customs – The true civilisation spread by religion; the false civilisation spread by trade – The Métis or Burntwoods – The Wars between the Companies – The death of the Indian languages

- Book VII: Chapter 11: The former French possessions in America – Regrets – Obsession with the past – A note from Francis Conyngham

Book VII: Chapter 1: Journey from Philadelphia to New-York and Boston - Mackenzie

London, April to September 1822. (Revised December 1846).

BkVII:Chap1:Sec1

I was impatient to continue my journey. It was not Americans I had come to see, but something totally different from the men I understood, something more in accord with the customary nature of my ideas; I longed to throw myself into an enterprise for which I was equipped with nothing but my imagination and courage.

When I framed the idea of discovering the North-West Passage, it was not known whether North America extended towards the Pole joining itself to Greenland, or whether it terminated in some sea contiguous with Hudson Bay and the Behring Straits. In 1772, Hearne had discovered the sea at the mouth of the Copper Mine River, in latitude 71 degrees 15 minutes North, and longitude 119 degrees 15 minutes West of Greenwich (Both latitude and longitude are now known to be too great by four and a quarter degrees: Note, Geneva 1832).

On the Pacific Coast, the efforts of Captain Cook and other later navigators had left certain doubts. In 1787, a ship was said to have entered an inland sea of North America; according to the narrative of the captain of this vessel, what had been taken for an uninterrupted coastline to the north of California, was really just a closely-linked chain of islands. The British Admiralty sent Vancouver to verify these reports, which proved false. Vancouver had not yet made his second voyage.

In the United States, in 1791, there was growing talk of the route taken by Mackenzie: starting from Fort Chippeway on Mountain Lake, on the 3rd June 1789, he descended the river to which he gave his name and reached the Arctic Ocean.

This discovery might have made me change direction and head due north; but I would have had scruples about altering the plan agreed between myself and Monsieur de Malesherbes. So I decided to travel west, so as to strike the north-west coast above the Gulf of California; from there, following the trend of the continent, and keeping the sea in sight, I hoped to explore the Behring Straits, double the northernmost cape of America, descend by the eastern shores of the Polar Sea, and return to the United States by way of Hudson Bay, Labrador, and Canada.

What means did I possess to execute this prodigious peregrination? None. Most French explorers have been solitary men, abandoned to their own resources; only rarely has the Government or some company employed or assisted them. Englishmen, Americans, Germans, Spaniards and Portuguese have accomplished, with the support of the national will, what in our case impoverished individuals have attempted in vain. Mackenzie, and others after him, have made conquests in the vast expanses of America, to the benefit of the United States and Great Britain, which I dreamt of making in order to extend the possessions of my native land. If I had succeeded, I would have had the honour of giving French names to unknown regions, of endowing my country with a colony on the Pacific Ocean, taking the rich fur trade from a rival power, and preventing that rival from opening up a shorter route to the Indies, by putting France herself in possession of that route. I have recorded these plans in my Essai historique, published in London in 1796, the plans being taken from my manuscript account of my travels in 1791. These dates show that I was ahead of the latest explorers of the Arctic ice-fields in my intentions and my writings.

I found no encouragement in Philadelphia. I recognised then that the object of this first voyage would not be achieved, and that my journey was only the prelude to a second, longer voyage. I wrote to this effect to Monsieur de Malesherbes, and while awaiting future events, I dedicated to poetry whatever would be lost to science. Indeed, if I failed to find in America what I sought, the Polar world, I did find a new Muse there.

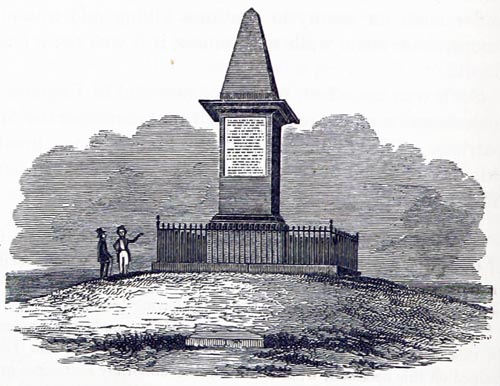

A stage-coach, like the one which had brought me to Baltimore, carried me from Baltimore to New-York, a lively, crowded, commercial city, which was nevertheless far from what it is today, far from what it will be in a few years time: for the United States grows faster than this manuscript. I went on a pilgrimage to Boston to salute the first battlefield of American liberty. I saw the plains of Lexington; I sought there, as since at Sparta, the tomb of those warriors who died in obedience to the sacred laws of their country. A memorable example of the links between human affairs! A finance bill, passed in the English Parliament in 1765, engendered a new power in the world in 1782, and caused the disappearance of one of the oldest kingdoms of Europe in 1789!

‘Lexington Monument’

History of the Siege of Boston, and of the Battles of Lexington, Concord and Bunker Hill - Richard Frothingham (p114, 1849)

The British Library

Book VII: Chapter 2: The Hudson River – A passenger’s recital – Mr Swift – Departure for Niagara Falls with a Dutch guide – Monsieur Violet

London, April to September 1822.

![The State of New York [Detail]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Chateaubriand/interior_chateaubriand_memoirs_bk7chap2sec1c.jpg)

‘The State of New York [Detail]’

Travels in New England and New York - Timothy Dwight (p20, 1823)

The British Library

BkVII:Chap2:Sec1

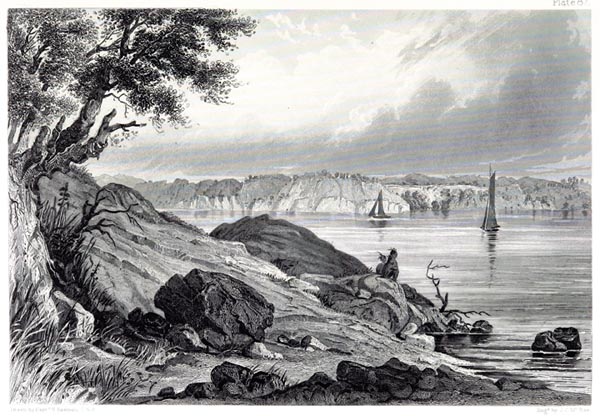

At New-York I embarked on the packet sailing for Albany, on the upper reaches of the Hudson River. The company was numerous. Towards evening on the first day, we were served a collation of fruit and milk; the women sat on the benches and the men on the deck, at their feet. Conversation was not long maintained: at the sight of a beautiful natural picture one involuntarily falls silent. Suddenly someone called out: ‘There is the place where Asgill was captured.’ They asked a Quaker girl from Philadelphia to recite the ballad called Asgill. We were among the mountains; the passenger’s voice was lost over the waters, or it swelled in volume when we sailed closer to the shore. The fate of a young soldier, a brave and poetic lover, honoured by Washington’s interest, and the generous intervention of an unfortunate Queen, added a romantic charm to the scene. The friend I lost, Monsieur de Fontanes, let fall courageous words in memory of Asgill, when Bonaparte was about to ascend the throne on which Marie-Antoinette had sat. The American officers seemed moved by the Pennsylvanian ballad: the memory of their country’s past troubles made them more aware of the calm of the present moment. They contemplated, with emotion, those places formerly swarming with soldiers, ringing with the sound of warfare, buried now in profound peace; those places gilded by the last light of day, alive with the whistling of redbirds, the cooing of blue wood-pigeons, the song of the mocking-birds, and whose inhabitants resting their arms on the fences of their enclosures, fringed with cross-vines, watched our boat pass by.

‘Esopus Landing, Hudson River’

The Indian Tribes of the United States - Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (p97, 1891)

The British Library

Arriving at Albany, I went to find Mr Swift, for whom I had a letter of introduction. This Mr Swift traded fur with the Indian tribes in the territory ceded to the United States by England; for the civilised powers, both republican and monarchist, unceremoniously apportion land in America between themselves which does not belong to them. After listening to me, Mr Swift raised some very reasonable objections. He told me that I could not undertake a journey of this importance on the spur of the moment, alone, without help, without support, and without letters of recommendation for the English, American, and Spanish posts through which I was forced to pass; that, if I had the good luck to cross such desolate wastes, I would reach frozen regions where I would die from cold and hunger: he advised me to begin by acclimatising myself, urging me to learn the Sioux, Iroquois, and Eskimo languages, to live with the trappers in the woods and the agents of the Hudson Bay Company. With this preliminary experience gained, I might then, in four or five years’ time, with the assistance of the French Government, proceed on my hazardous mission.

This advice, whose validity I inwardly recognised, annoyed me. If I had believed in myself, I should have left for the Pole right away, as one sets off from Paris for Pontoise. I hid my displeasure from Mr Swift; I asked him to find me a guide and some horses to take me to Niagara and Pittsburg: from Pittsburg, I would descend the Ohio and gather useful ideas for future projects. I had my original route plan always in mind.

Mr Swift engaged a Dutchman for me who spoke several Indian dialects. I bought a pair of horses and left Albany.

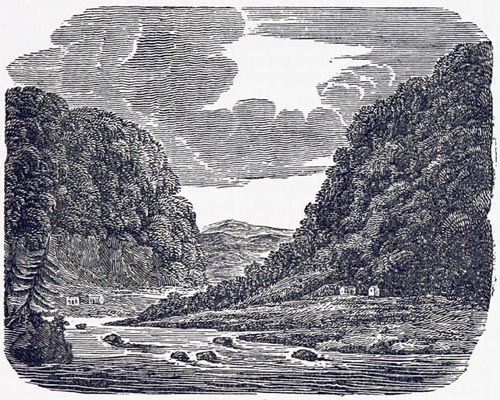

The whole stretch of country between that town and Niagara is now cleared and inhabited; the New York canal crosses it; but then a large part of the territory was wilderness.

When the Mohawk had been crossed, and I had entered woods where no trees had ever been felled, I was seized with a sort of intoxication of freedom: I went from tree to tree, left and right, saying to myself: ‘Here there are no more roads, no more towns, no monarchies, no republics, no presidents, no kings, no human beings.’ And, to see if I was truly re-possessed of my original rights, I indulged in wild antics which enraged my guide, who in his heart, thought me mad.

‘Valley of the Mohawk’

A Book of the United States - Grenville Mellen (p35, 1839)

The British Library

Alas! I thought I was alone in that forest where I held my head so high! Suddenly, I almost bruised my nose on the side of a shelter. Once beneath it, I set astonished eyes on the first savages I had ever seen. There were a score of them, men and women, painted like sorcerers, bodies half-naked, ears slit, crows’ feathers on their heads, and rings through their noses. A little Frenchman, hair curled and powdered, in an apple-green coat, a woollen jacket, and a muslin shirt-frill and ruffles, was scraping a pocket-fiddle, and making the Iroquois dance to Madelon Friquet. Monsieur Violet (for so he was called) was dancing-master to these savages. They paid for his lessons in beaver skins and bears’ hams. He had been a scullion in the service of General Rochambeau, during the American War. Remaining in New York, after the departure of our army, he had resolved to instruct the Americans in the fine arts. His ambition had grown with his success, and the new Orpheus was carrying civilisation to the savage hordes of the New World. Speaking to me of the Indians, he always said to me: ‘These savage ladies and gentlemen.’ He took great pride in the agility of his pupils; indeed I have never seen such capering. Monsieur Violet, holding his little violin between chest and chin, would tune the fatal instrument and call to the Iroquois: ‘Take your places!’ And the whole troop would leap about like a band of demons.

Was it not a devastating experience for a disciple of Rousseau, this introduction to savage life via a dancing-lesson given to the Iroquois by General Rochambeau’s scullion? I was greatly tempted to laugh, though I felt cruelly humiliated.

Book VII: Chapter 3: My savage outfit – Hunting – The Carcajou or Wolverine – The Muskrat – Water dogs – Insects – Montcalm and Wolfe

London, April to September 1822.

BkVII:Chap3:Sec1

I bought a complete outfit from the Indians: two bearskins, one to serve as a half-toga; the other as a bed. I added to my new apparel the red cap in ribbed cloth, the cloak, the belt, the horn for calling in the dogs, and the bandolier of a trapper. My hair hung down over my bare neck; I sported a long beard, I was savage, hunter, and missionary all in one. They invited me to a hunt taking place next day, to track down a carcajou, or wolverine. This species is almost entirely extinct in Canada, like the beaver.

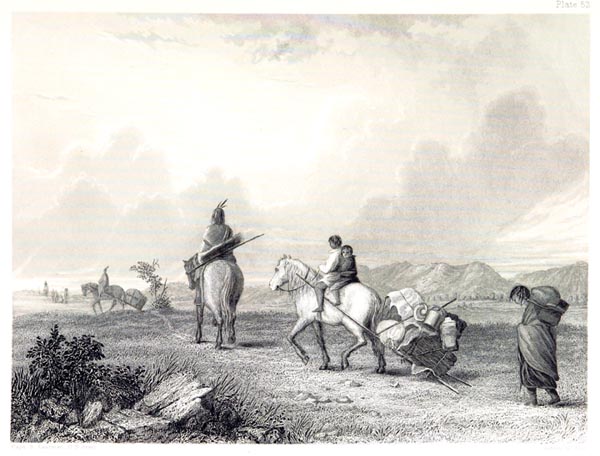

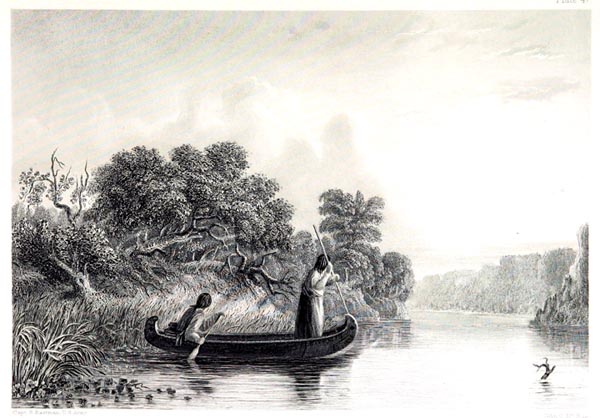

We embarked before dawn, to ascend a river flowing from the woods where the wolverine had been seen. There were thirty or so of us, Indians as well as American and Canadian trappers: part of the group walked the bank beside the flotilla, with the dogs, and the women carried our provisions.

‘Indians Travelling’

The Indian Tribes of the United States - Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (p339, 1891)

The British Library

We found no trace of the carcajou; but we killed some lynxes and muskrats. The Indians would go into deep mourning, when they accidentally killed any of the latter, since the female muskrat is, as they all know, the mother of the human race. The Chinese, being even better observers, maintain with certainty that the rat can turn into a quail, the mole into an oriole.

Our table was furnished with an abundance of river-birds and fish. The dogs are trained to dive; when they are not hunting they go fishing: they throw themselves into the rivers and seize the fish from the very bottom of the water. The women cooked our meals on a large fire, round which we took our places.

We had to lay flat, faces to the earth, to protect our eyes from the smoke, clouds of which, floating above our heads, preserved us to some degree from mosquito bites.

The various carnivorous insects, seen through a microscope, are formidable creatures. They were those winged dragons perhaps whose fossils are met with: diminished in size, in the way that matter loses energy, those hydras, griffons and the rest, are found today in an insect state. The antediluvian giants are the little men of our own day.

Book VII: Chapter 4: Encampment by the Lake of the Onondagas – Arabs – The Indian and the cow

London, April to September 1822.

BkVII:Chap4:Sec1

Monsieur Violet offered me letters of credence for the Onondagas, the remnant of one of the six Iroquois nations. I came first of all to the Lake of the Onondagas. The Dutchman chose a suitable place to pitch camp: a river flowed from the lake; our shelter was set up in the bend of this river. We drove two forked stakes into the ground, six feet apart; we suspended a long pole horizontally in the forks of these stakes. Strips of birch bark, one end resting on the ground, the other on the transverse pole, formed the sloping roof of our palace. Our saddles had to serve as pillows and our cloaks as blankets. We fastened bells to our horses’ necks and turned them loose in the woods near our camp: they did not wander far.

![The State of New York [Detail]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Chateaubriand/interior_chateaubriand_memoirs_bk7chap4sec1b.jpg)

‘The State of New York [Detail]’

Travels in New England and New York - Timothy Dwight (p20, 1823)

The British Library

Fifteen years later, when I bivouacked among the sands of the desert of Saba, a few steps from the Jordan, on the edge of the Dead Sea, our horses, those slight offspring of Arabia, looked as though they were listening to tales of the Sheiks, and taking part in the story of Antar or Job’s steed.

It was scarcely four hours after midday when we completed our camp. I took my gun and went to explore the neighbourhood. There were few birds. Only a solitary pair flew up in front of me, like the birds I hunted in my native woods; from the colour of the male I recognised the white sparrow, passer nivalis of the ornithologists. I also heard the osprey, so well characterised by its call. The flight of that exclamator, led me through the woods to a valley hemmed in between bare and rocky heights; half-way up stood a wretched cabin; a lean cow was grazing in a meadow below.

I like such little shelters: ‘A chico pajarillo, chico nidillo: for a little bird a little nest.’ I sat down on the slope facing the hut planted on the opposite slope.

After a few minutes, I heard a voice in the valley: three men were driving five or six fat cows along; they set them to grazing and drove the lean cow off with blows from their switches. An Indian woman came out of the hut, went towards the frightened animal, and called to it. The cow ran towards her stretching out its neck and lowing. The settlers threatened the woman from the distance, as she returned to the cabin. The cow followed her.

I rose, descended the slope on my side, crossed the valley, and climbing the opposite hill, arrived at the hut.

I pronounced the greeting I had been taught: ‘Siegoh! I am come.’ The Indian woman, instead of replying to my greeting by repeating the usual phrase: ‘You are come’, failed to reply at all. Then I stroked the cow: the sad yellow face of the Indian woman showed signs of feeling. I was moved by those mysterious acquaintances in adversity: there is tenderness in grieving over ills which no one else has ever grieved over.

The woman gazed at me for some time with lingering doubt then she came forward and placed her own hand on the brow of her companion in misery and solitude.

Encouraged by this mark of confidence, I said in English, since I had exhausted my Indian: ‘She is very thin!’ The Indian replied in bad English: ‘She eats very little’ – ‘She was badly treated,’ I continued. And the woman replied: ‘We are both accustomed to it; Both.’ I said: ‘This field is not yours then?’ She answered: ‘The field belonged to my dead husband. I have no children, and the pale-skins drive their cattle into my field.’

I had nothing to offer God’s creature. We parted. The woman said many things to me which I could not understand; no doubt wishes for my prosperity; if they were not heard in heaven, it was not the fault of the one who offered them, but the fault of him for whom the prayers were offered. Every soul does not possess an equal capacity for happiness, just as every field does not bear the same harvest.

I returned to my ajoupa (shelter), where a meal of potatoes and maize awaited me. The evening was magnificent; the lake, smooth as an un-silvered mirror, showed never a wrinkle; the river, murmuring, bathed our almost-island that the spice-bushes (calycanthus floridus) perfumed with the scent of apples. The whippoorwill repeated its cry: we heard it, now near, now far away, as the bird altered the location of its amorous calls. It was not my name being called. Weep, poor Will!

‘Spearing Fish from a Canoe’

The Indian Tribes of the United States - Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (p311, 1891)

The British Library

Book VII: Chapter 5: An Iroquois – The Sachem of the Onondagas – Velly and the Franks – A ceremony of hospitality – The Ancient Greeks

London, April to September 1822.

BkVII:Chap5:Sec1

Next day, I went to visit the sachem of the Onondagas; I reached his village at ten in the morning. Immediately, I was surrounded by young savages who spoke to me in their language, intermixed with English phrases and a few French words; they made a great noise, and seemed happy, like the first Turks I saw later at Modon, when I disembarked on the soil of Greece. These Indian tribes, restricted to clearings made by the whites, have horses and cattle of their own; their huts are full of utensils bought in Quebec, Montreal, and Detroit, on the one side, and the markets of the United States on the other.

Those who explored the North American interior found all the different forms of government known to civilised peoples, among the various savage nations. The Iroquois belonged to a race which seemed destined to conquer all of the Indian races, if strangers had not arrived to bleed his veins dry, and arrest his genius. That intrepid creature was not awed by firearms, when they were first used against him; he stood firm while bullets whistled and cannon roared, as if he had heard them all his life; he seemed to pay them no more attention than a passing storm. As soon as he could procure a musket, he employed it more effectively than a European. He did not abandon the tomahawk, scalping-knife, or bow and arrow, because of it; he added to them the carbine, pistol, dagger and hatchet: he seemed never to have enough weapons to match his valour. Doubly equipped with the murderous instruments of Europe and America, head decorated with feathers, ears slit, face daubed with diverse colours, arms tattooed and blood-smeared, this champion of the New World became as redoubtable in appearance as in battle, on the shores which he defended foot by foot against the invaders.

The sachem of the Onondagas was an old Iroquois in the full meaning of the word; in his person he guarded the ancient traditions of the wilderness.

English writers never fail to call the Indian sachem the old gentleman. Now, the old gentleman is completely naked; he sports a feather or a fishbone piercing his nostrils, and sometimes covers his head, smooth and round as a cheese, with a three-cornered hat edged with lace, as a European mark of honour. Does Velly not portray history with the same realism? The Frankish chieftain Chilpéric rubbed his hair with rancid butter, infundens acido comam butyro, painted his cheeks with woad, and wore a striped jacket or a tunic of animal skins; Velly represents him as a prince magnificent to the point of ostentation as to his furniture and retinue, voluptuous to the point of debauchery, scarcely believing in God, whose ministers were subjected to his mockery.

The sachem of the Onondagas received me courteously and invited me to be seated on a mat. He spoke English and understood French; my guide knew Iroquois: the conversation was relaxed. Among other things, the old man told me that though his nation had warred with mine, he had always respected it. He complained of the Americans; he found them unjust and covetous and regretted that in the partition of Indian territories his tribe had not augmented the share that went to the English.

The women served us a meal. Hospitality is the last virtue retained by the savages in the midst of the vices of European civilisation; what that hospitality once was is well-known; the hearth was as sacred as the altar.

When a tribe was driven from its woods, or when a man came seeking hospitality, the stranger began what was called the dance of the suppliant; the youngest child in the hut touched the threshold and said: ‘Here is the stranger!’ And the chief replied: ‘Child, bring him into the hut.’ The stranger, entering into the child’s protection, went to sit among the ashes of the hearth. The women sang a song of consolation: ‘The stranger has found a wife and a mother. The sun will rise and set for him as before.’

These customs appear as if borrowed from the Greeks: Themistocles, calling on Admetus, kisses the penates and his host’s young son; (At Megara I trod perhaps on the poor woman’s hearthstone, under which Phocion’s cinerary urn was hidden); and Ulysses, in Alcinous’ palace, implores Arete: ‘Noble Arete, daughter of Rhexenor, after suffering cruel misfortune, I throw myself at your feet.’ Having spoken these words, the hero goes and sits among the ashes of the hearth. – I took leave of the old sachem. He had been present at the siege of Quebec. Among the shameful years of Louis XV’s reign, the episode of the Canadian War consoles us, as if it were a page of our ancient history discovered in the Tower of London.

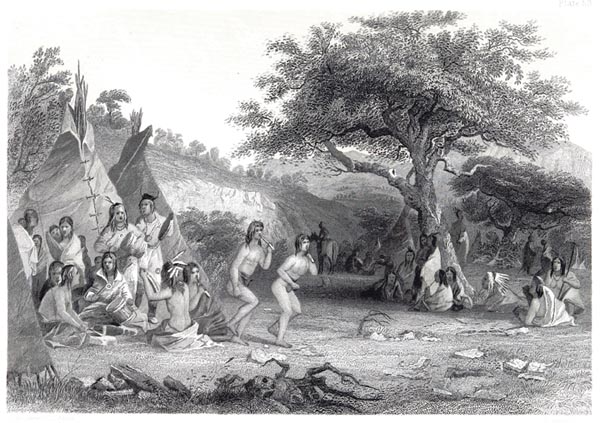

‘Worshipping the Sun’

The Indian Tribes of the United States - Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (p345, 1891)

The British Library

Montcalm, charged with defending Canada unaided, against forces four times his in number and continually replenished, fights successfully for two years; he defeats Lord Loudon and General Abercrombie. At last fortune deserts him; wounded beneath the walls of Quebec, he falls, and two days later breathes his last: his grenadiers bury him in a crater made by a shell, a grave worthy of the honour of our arms! His noble opponent Wolfe dies facing him. He pays with his own life for Montcalm’s, and for the glory of expiring on a few French flags.

Book VII: Chapter 6: Journey from the Lake of the Onondagas to the River Genesee – Bees – Clearings – Hospitality – A bed – A rattlesnake charmed by a flute

London, April to September 1822.

BkVII:Chap6:Sec1

Now my guide and I remounted our horses. Our trail became more difficult, marked only by a line of felled trees. The trunks of these trees served as bridges over the streams, or as fascines through the quagmires. At this time Americans were settling nearer to the Genesee concessions. These concessions fetched a higher or lower price depending on the condition of the soil, the quality of the trees, and the course and force of the water.

It has been observed that settlers are often preceded in the woods by bees: the vanguard of the farmers, they are symbols of the civilisation and industry they herald. Strangers to America, arriving in the wake of Colombus, these peaceful conquerors have only robbed this new world of flowers of treasures whose use was unknown to the natives: they have only employed these treasures to enrich the soil they took them from.

The clearings on both sides of the road along which I travelled, offered a curious blend of the natural and civilised state. In one corner of a wood which had only ever known the yell of the savage and the calls of wild creatures, one came across a ploughed field; from the same viewpoint one saw an Indian wigwam and a planter’s cabin. Some of these cabins, already finished, recalled the neatness of Dutch farm-houses; others only half-complete, had no roof but the sky.

I was received in these dwellings, the result of a morning’s work; there I often found a family surround by European elegance: mahogany furniture, a piano, carpets and mirrors, a few paces from an Iroquois hut. In the evening, when the farm-workers had returned from the woods and fields armed with axes and hoes, the windows were opened. My host’s daughters, their lovely blonde hair in ringlets, accompanied at the piano would sing the duet from Paisiello’s Pandolfetto, or a cantabile by Cimarosa.

In the better districts, small towns were established. The spire of a new church rose from the heart of an old forest. As the English take their customs with them wherever they go, when I had crossed a region without a trace of inhabitants, I would come across an inn-sign swinging from the branch of a tree. Trappers, planters and Indians, met together at these caravanserais: the first time I stayed at one, I swore it would be my last.

On entering one of these hostelries, I stood amazed at the sight of an immense bed, built in a circle round a post: each traveller took his place in this bed, his feet against the post in the middle, his head at the circumference of the circle, so that the sleepers were arranged symmetrically, like the spokes of a wheel or the sticks of a fan. After some hesitation, I climbed into this contraption, since I could see no one else within. I was beginning to doze, when I felt something slide against me: it was the leg of my big Dutchman; I’ve never in my life experienced a greater sense of horror. I leapt from the hospitable receptacle, cordially cursing the customs of our good forefathers. I went and slept in my cloak in the moonlight: that voyager’s bedfellow at least was all sweetness, freshness, and purity.

On the bank of the Genesee, we found a ferry. A troop of settlers and Indians crossed the river with us. We camped in meadows bright with butterflies and flowers. In our varied clothing, our different groups around the fire, our horses tethered or grazing, we had the look of a caravan. It was there I made the acquaintance of the rattlesnake, which allows itself to be charmed by the notes of a flute. The Greeks would have made an Orpheus of my Canadian; a lyre of the flute; Cerberus, or perhaps Eurydice of the snake.

Book VII: Chapter 7: An Indian Family – Night in the forest – The family departs – The savages of Niagara Falls – Captain Gordon – Jerusalem

London, April to September 1822.

![The State of New York [Detail]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Chateaubriand/interior_chateaubriand_memoirs_bk7chap7sec1.jpg)

‘The State of New York [Detail]’

Travels in New England and New York - Timothy Dwight (p20, 1823)

The British Library

BkVII:Chap7:Sec1

We rode on to Niagara. We were no more than twenty miles or so distant, when we saw, in an oak-grove, the camp-fire of some savages who had halted beside a stream, where we ourselves thought of bivouacking. We profited from their prior efforts: after grooming the horses, and preparing for night, we approached the group. Legs crossed in the manner of tailors, we seated ourselves among the Indians, round the fire, to roast our maize-cakes.

The family comprised two women, two infants at the breast, and three braves. The conversation became general that is to say a great many gestures were interspersed with a few words from me; later they all fell asleep where they were sitting. The only one left awake, I went to sit by myself on a tree root which stretched alongside the stream.

The moon showed above the treetops; a balmy breeze, which that Queen of the Night brought with her from the Orient, seemed to precede her through the forest, as if it were her cool breath. The solitary light rose higher and higher in the sky: now following her course, now traversing banks of cloud that resembled the summits of some snow-crowned mountain chain. All would have been silence and peace, but for the fall of a few leaves, the passage of a sudden breeze, the hooting of a tawny owl; far off, the dull roar of Niagara Falls could be heard, echoing from wild to wild, in the still of night, before dying away among the lonely forests. It was in nights like these that a previously unknown Muse appeared to me; I gathered some of her inflections; I noted them in my book, by starlight, as a commonplace musician might transcribe the notes dictated to him by a great master of harmonies.

Next day, the Indians armed themselves, while the women collected the baggage. I distributed a little gunpowder and some vermilion amongst my hosts. We parted, touching our foreheads and chests. The braves gave out a cry as a signal to march, and set off in front; the women walked behind, carrying children, who, slung in furs from their mothers’ backs, turned their heads to look at us. I followed their departure with my eyes, until the whole troupe vanished among the forest trees.

The savages of Niagara Falls in the English dependency were charged with policing that side of the frontier. This bizarre constabulary, armed with bows and arrows, prevented us from crossing. I was obliged to send the Dutchman to Fort Niagara for a permit to enter the British Government’s area of control. This saddened my heart somewhat, when I remembered that France had once controlled Upper and Lower Canada. My guide returned with the permit: I still have it, signed: Captain Gordon. Is it not singular that I discovered the same British name on the door of my cell in Jerusalem? ‘Thirteen pilgrims had inscribed their names on the room’s door and walls: the first was Charles Lombard, and he visited Jerusalem in 1669; the last was John Gordon, and the date of his stay was 1804.’ (Itinéraire).

Book VII: Chapter 8: Niagara Falls – A rattlesnake – I fall over the edge of the gorge

London, April to September 1822.

BkVII:Chap8:Sec1

I spent two days in the Indian village, from which I wrote another letter to Monsieur Malesherbes. The Indian women occupied themselves in various tasks; their babies were slung in nets from the branches of a large copper beech. The grass was covered with dew, the breeze emerged from the forest all scented, and the cotton plants, their bolls inverted, resembled white rose-bushes. The breeze rocked the aerial cradles with an almost imperceptible motion; the mothers rose from time to time to see that their children were asleep, and had not been woken by the birds. It was ten miles or so from the Indian village to the falls: it took me and my guide half as many hours to reach them. Already, six miles away, a column of mist indicated the position of the waterfall. My heart beat with joy mingled with terror on entering the wood which hid from view one of the greatest spectacles that Nature has offered mankind.

We dismounted. Leading our horses by the bridle, we made our way through heaths and copses, to the bank of the Niagara River, seven or eight hundred paces above the falls. As I was still going forward, the guide seized my arm; he arrested my course at the very edge of the water, which swept by with the speed of an arrow. It did not foam, it glided in a solid mass over the rocky slope; its silence prior to falling contrasted with the fall itself. Scripture often compares a nation to mighty waters; this was a dying nation, which robbed by agony of its voice, was hurling itself into the abyss of eternity.

The guide held me fast, for I felt drawn, so to speak, towards the flood, and had an involuntary desire to hurl myself into it. Now I gazed at the river banks upstream, now downstream at an island that separated the waters, and the point where those waters suddenly ceased, as if they had been cut off in mid-air.

After a quarter of an hour of perplexity, and an indefinable admiration, I went on to the falls. You can find the two descriptions of them I have given, in the Essai sur les révolutions, and in Atala. Today, wide highways lead to the cataract; there are inns on the American side, and the British, and mills and factories below the chasm.

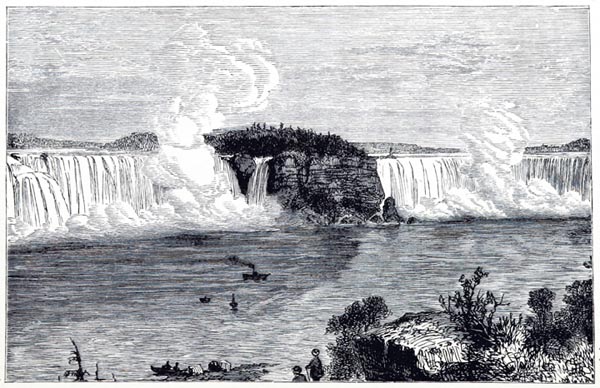

‘Niagara Falls’

Great Waterfalls, Cataracts, and Geysers, Described and Illustrated - John Gibson (p25, 1887)

The British Library

I cannot convey the thoughts that stirred in me at the sight of such sublime disorder. In the wildernesses of my early existence, I was forced to invent people to adorn them; I drew from my own substance beings I found nowhere else, that I carried within me. So I placed the remembrances of Atala and René beside Niagara Falls, as if they were an expression of its sadness. What is a cataract, falling eternally beneath the senseless gaze of earth and sky, if human nature is not there with its misfortunes and destiny? To sink into that solitude of water and mountains, and know not whom to tell of that great spectacle! The waves, rocks, woods, torrents there for itself alone! Give the soul a companion, and the smiling finery of the hills, the breath of fresh air from the flood, becomes wholly delightful: the day’s travels, the sweetest of rests at the end of the journey, the passage of the waves, sleep on a bed of moss, elicit the deepest tenderness from the heart. I seated Velléda on Armorica’s shores; Cymodocée under Athenian porticos; Blanca in the Alhambra’s halls. Alexander created cities everywhere he passed: I have left dreams everywhere I have trailed my life.

BkVII:Chap8:Sec2

I have seen the cascades of the Alps with their chamois, and those of the Pyrenees with their lizards; I have not ascended high enough up the Nile to view its cataracts, which are merely rapids; and I say naught of the azure zones of Terni and Tivoli, elegant settings for ruins, or subjects for the poet’s song:

Et praeceps Anio ac Tiburni lucus:

‘And swift Anio and the sacred groves of Tibur’

Niagara eclipses them all. I considered this cataract which was revealed to the old world, not by feeble travellers of my sort, but by missionaries, who, searching the solitude for God, threw themselves on their knees at the sight of some wonder of nature, and accepted martyrdom as they ended their hymn of praise. Our priests saluted the beautiful landscapes of America, and consecrated them with their blood; our soldiers clapped their hands at the ruins of Thebes and presented arms to Andalusia: all the genius of France is in its twin militia of camp and altar.

I was holding my horse’s bridle twisted round my arm; a rattlesnake started rustling among the bushes. The frightened horse reared and backed towards the falls. I could not free my arm from the reins; the horse ever more terrified, dragged me with him. His forefeet already off the ground, on his haunches at the edge of the abyss, he held position only by the strength of his loins. It was all over with me, when the animal himself astonished by his new peril, pirouetted backwards to safety. Dying in the Canadian woods, would my soul have borne, to the supreme tribunal, sacrifices, good works, virtues like those of Père Jogues and Père Lallemand, or wasted days and wretched fantasies?

This was not the only danger I ran at Niagara: a ladder of creepers allowed the savages to climb down to the lower basin; it was broken. Wishing to view the falls from below, I ventured, despite my guide’s protests, onto the flank of an almost perpendicular rock. In spite of the roar of the water foaming below me, I kept my head and got to within forty feet of the bottom. At that point, the stone being bare and vertical, offered me no foothold; I remained clutching a last root with one hand, feeling my fingers opening under the weight of my body: few men have spent two minutes such as I counted then. My weary hand let go: I fell. By extraordinary good luck, I found myself on the edge of a rock, on which I should have been smashed to a thousand pieces, without feeling myself greatly injured; I was a few inches from the abyss, and had not rolled into it; but when the cold and damp began to penetrate I saw that I had not escaped so lightly: I had broken my left arm above the elbow. The guide, who could see me from above and to whom I made signs of distress, ran to find the savages. They hoisted me up with ropes by an otters’ path, and carried me to their village. I had only a simple fracture: a pair of splints, a bandage, and a sling, was sufficient for my cure.

Book VII: Chapter 9: Twelve days in a cabin – Changing customs among the savages – Birth and death – Montaigne – Song of the adder – The little Indian girl, the original of Mila

London, April to September 1822.

BkVII:Chap9:Sec1

I stayed for twelve days with my doctors, the Indians of Niagara. I saw tribes there who had come from Detroit or from the country to the centre and east of Lake Erie. I enquired about their customs; for a few small gifts I obtained re-enactments of their ancient rites, since the rites themselves scarcely exist now. Nevertheless, at the beginning of the American War of Independence, the savages still ate their prisoners, or rather the dead ones: an English captain, ladling some soup from an Indian woman’s cooking pot with a ladle, retrieved a hand.

The Indian customs associated with birth, and death, are the least eroded, since they have not been thoughtlessly lost, like those of the segments of life which separate them; they are not things of passing fashion. In order to honour him, the new-born child still has the most ancient name of his family bestowed upon him; that of his grandmother for instance: since names are always taken from the maternal line. From that moment, the child occupies the place of the woman whose name he has received; in speaking to him, one grants him the status of the relative brought to life again by the name; so an uncle may address his nephew by the title of grand-mother. This custom, laughable thought it may seem, is nevertheless touching. It resurrects the ancient dead; it recreates in the feebleness of the first years of life, the feebleness of the last; it brings together the extremities of life, the beginning and end of a family; it confers a species of immortality on their ancestors and imagines them present in the midst of their descendants.

In what concerns the dead, it is easy to find signs of the savage’s attachment to sacred relics. Civilised nations, in order to preserve their country’s memories, have the mnemonics of writing and the arts; they have cities, palaces, spires, columns, obelisks; they have the marks of the plough on once-cultivated fields; their names are cut in bronze and marble, their actions recorded in their histories.

Nothing of that appertains to the peoples of the wilderness: their names are not written on the trees; their huts, built in a few hours, vanish in a moment; the sticks with which they labour barely scratch the earth, and cannot even raise a furrow. Their traditional songs die with the last memory that retains them, vanishing with the last voice that repeats them. The tribes of the New World have only one monument: their graves. Take the bones of their fathers from these savages, and you take from them their history, their laws and even their gods; you remove from those men, for future generations, the proof of their existence as that of their extinction.

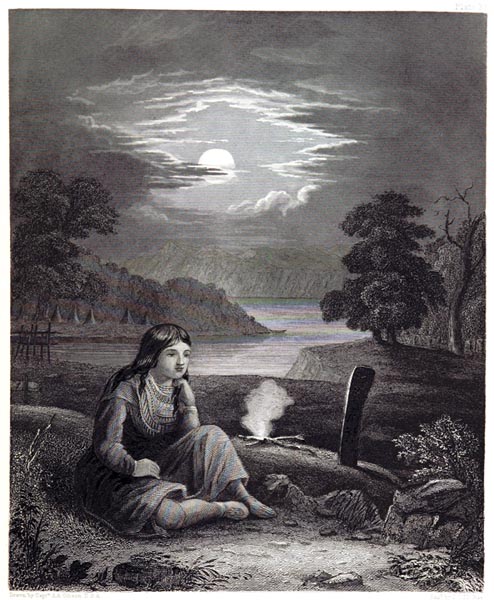

‘Nocturnal Grave Light’

The Indian Tribes of the United States - Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (p233, 1891)

The British Library

I wished to hear the songs of my hosts. A little fourteen-year old Indian girl, called Mila, a very pretty girl (Indian women are only pretty at that age) sang something quite delightful. Was this not the very couplet cited by Montaigne? ‘Adder stay now! Stay now, Adder, so my sister may take from the pattern of your markings, the embroidery and style of a fine belt I may give my beloved: so shall your beauty and decoration be preferred forever above all other snakes.’

The author of the Essais met with Iroquois at Rouen who, according to him, were very reasonable people: ‘But, still,’ he adds, ‘they do not wear breeches!’

If I ever publish the stromateis or follies of my youth, as Saint Clement of Alexandria did, Mila will appear there.

Book VII: Chapter 10: DIGRESSIONS - Ancient Canada – The Indian population – The decline of customs – The true civilisation spread by religion; the false civilisation spread by trade – The Métis or Burntwoods – The Wars between the Companies – The death of the Indian languages

London, April to September 1822.

BkVII:Chap10:Sec1

The Canadians are no longer such as were described by Cartier, Champlain, La Hontan, Lescarbot, Lafitau, Charlevoix and the Lettres édifiantes: the sixteenth century and the start of the seventeenth century were still an era of powerful imagination and simple customs; the wonder of the former reflected virgin nature, and the candour of the latter recreated the simplicity of the savage. Champlain, at the finish of his first voyage to Canada, in 1603, recounts that close ‘to the Baye des Chaleurs, to the south, is an island, where a dreadful monster lives, that the savages call Gougou.’ Canada had its giant just as the Cape of Good Hope did. Homer is the true father of all these inventions; There are always the Cyclopes, Charybdis and Scylla, ogres and gougous.

The savage population of North America, not including the Mexicans or Eskimos, comprises today no more than four hundred thousand souls, on both sides of the Rocky Mountains; travellers even put it as low as a hundred and fifty thousand. The decline of Indian customs has gone hand in hand with the depopulation of the tribes. Their religious traditions have become confused; the instruction spread by Canadian Jesuits has mingled foreign ideas with the native ideas of the indigenous peoples: one finds, in their crude fables, Christian beliefs disfigured; most of the savages wear a cross as an ornament, and the protestant traders sell them what the Catholic missionaries give them. Let me say, to the honour of our country and the glory of our religion, that the Indians are strongly attached to us; that they never cease to mourn our absence, and that a robe noire (a black robe, a missionary) is still the subject of veneration in the American forests. The savage continues to love us beneath the trees where we were his first guests, on the soil we have trodden, and where we have consigned to him our graves.

When the Indian was naked, or dressed in skins, he had something great and noble about him; in our time, European rags, without covering his nakedness, are a witness to his wretchedness: he is a beggar at the inn-door, no longer a savage in the forest.

In the end, an intermediate race, the Métis, formed, born of colonists and Indian women. These men, nicknamed Boisbrûlés (Burntwoods), because of the colour of their skin, are the exchange-brokers between the creators of their twin origin. Speaking the languages of both their fathers and their mothers, they possess the vices of both races. These bastards of a civilised and a savage nature, sell themselves now to the Americans, now to the English, so that they might grant them the fur monopoly; they fuel the rivalry between the English Hudson’s Bay and North West companies, and the American companies, Columbian-American Fur, Missouri Fur and the rest: they hunt themselves, as paid specialists, and with the hunters paid by the companies.

Only the great war of American Independence is famous. We forget that blood also flowed on account of the minor interests of a handful of merchants. The Hudson’s Bay Company sold, in 1811, to Lord Selkirk, land along the Red River; it was settled in 1812. The North-West or Canada Company took umbrage at this. The two companies, allied to different Indian tribes and supported by the Boisbrûlés, came to blows. This domestic conflict, horrid in its details, took place amongst the frozen wildernesses of Hudson Bay. Lord Selkirk’s colony was destroyed in June 1815, exactly at the time of the Battle of Waterloo. In these two theatres of warfare, so different in their brilliance and obscurity, the woes of the human species were the same.

Search no longer, in America, for those artistically constructed political constitutions of which Charlevoix has recounted the history: the Huron monarchy, or the Iroquois Republic. Something of that destruction has been accomplished and is still being accomplished in Europe, under our very eyes; a Prussian poet, at a banquet given by the Teutonic Order, recited, in old Prussian of about 1400, the heroic deeds of his country’s ancient warriors: no one understood him, and they gave him, in recompense, a hundred empty walnut shells. Today, Breton, Basque, Gaelic die out from cottage to cottage, with the vanishing goat-herds and ploughmen.

In the English county of Cornwall, the native language was extinct by about 1676. A fisherman said to some travellers: ‘I scarcely know four or five people who speak Breton, and they are old timers like me, sixty to eighty years old; all the youngsters no longer understand a word.’

The small tribes of the Orinoco no longer exist; of their dialect there only remain a dozen or so words uttered in the tree-tops by parakeets that have been freed, like Agrippina’s thrush that chirped Greek words from the balustrades of the Roman palaces. Such will be, sooner or later, the fate of our modern tongues, the ruins of Greek and Latin. What raven, freed from a cage, belonging to the last Franco-Gallic priest, will croak, to a foreign people, our successors, from the heights of some ruined bell-tower: ‘Hear the accents of a voice once known to you: you will bring an end to all such speech.’

Live on so, Bossuet, that in the end your masterpiece may outlast, in a bird’s memory, your language and your remembrance among men!

Book VII: Chapter 11: The former French possessions in America – Regrets – Obsession with the past – A note from Francis Conyngham

London, April to September 1822.

BkVII:Chap11:Sec1

Speaking of Canada and Louisiana, or looking, on the old maps, at the extent of the former French colonies in America, I have asked myself how the government of my country could have allowed those colonies to perish, that today would have been an inexhaustible source of prosperity for us.

From Acadia and Canada to Louisiana, from the mouth of the St Lawrence to that of the Mississippi, the territory of New France surrounded that which formed the confederation of the first thirteen united states: eleven others, with the district of Columbia, the territory of Michigan, the North-West, Missouri, Oregon and Arkansas, belonged to us, or would have belonged to us, as they do belong to the United States after their transfer by the English and Spanish, our successors in Canada and Louisiana. The region between the Atlantic to the north-east, the Arctic Sea to the north, the Pacific Ocean and the Russian possessions to the north-west, and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, that is to say more than two thirds of North America, acknowledged French law,

I fear that the Restoration has simply lost its way among ideas contrary to those which I express here: its obsession with holding onto the past, an obsession which I never ceased to oppose, would not have been a disaster if it had merely overthrown me by removing a prince’s favour from me; but it might in fact overthrow the throne. Stasis is impossible in politics; power must advance with human intelligence. Let us respect the greatness of time; let us contemplate with veneration the flow of the centuries, made sacred by the memory and footsteps of our forefathers; however let us not try to progress backwards towards them, because they no longer possess anything of our real being, and if we attempt to seize them, they vanish. The Chapter of Notre Dame d’Aix-la-Chapelle opened Charlemagne’s tomb, they say, around 1450. They found the emperor seated on a golden chair, holding in his skeletal hands the Book of the Gospels written in letters of gold: before him were set his sceptre and his shield of gold; at his side was his sword Joyeuse, sheathed in a golden scabbard. He was dressed in Imperial robes. On his head, which a gold chain held upright, was a veil that covered what had been his face, surmounted by a crown. They touched the phantom; it fell to dust. We owned vast countries overseas: they offered a refuge for our excess population, a market for our trade, a source of supply for our navy. We are excluded from a new universe, where the human race is starting again: the English, Portuguese, and Spanish languages serve, in Africa, Asia, Oceania, the South Sea Islands, and on the continent of the two Americas, to convey the thoughts of many millions of men; while we, disinherited of the conquests achieved by our courage and our genius, are at pains to hear the language of Colbert and Louis XIV spoken in some little town of Louisiana and Canada, under foreign domination: it remains only as a witness to our reverses of fortune, and our political mistakes.

‘Charlemagne’

The History of the French Revolution, 1789 to 1795; or a Country Without a God - Henry H. Northrop (p29, 1890)

The British Library

And who is the king whose power now replaces that of the King of France in the Canadian forests? He who long ago had this note penned to me:

Royal Lodge, Windsor, 4th June 1822

Monsieur Le Vicomte,

I am commanded by the King to invite Your Excellency to dine and stay overnight here on this Tuesday 6th.

Your very humble and very obedient servant,

Francis Conyngham

It was my destiny to be tormented by princes. I broke off; I re-crossed the Atlantic once more; I restored the arm broken at Niagara; I stripped myself of my bearskin; I put on my gilded vestments again; I returned from an Iroquois wigwam to the Royal Lodge of his Britannic Majesty, monarch of three united kingdoms, and Emperor of India; I left behind my hosts with pierced ears and the little beaded native girl; wishing Lady Conyngham the sweetness of Mila, and her years which still belong only to the earliest moment of spring, to those days which precede the May month, and which our Gallic poets call l’Avrillée.

End of Book VII