François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book VI: To America 1791

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book VI: Chapter 1: Prologue

- Book VI: Chapter 2: Ocean Passage

- Book VI: Chapter 3: Francis Tulloch – Christopher Columbus - Camoëns

- Book VI: Chapter 4: The Azores – The Island of Graciosa

- Book VI: Chapter 3: Ocean customs – The Island of Saint-Pierre

- Book VI: Chapter 6: The Virginian Coast – The setting sun – Peril – I land in America – Baltimore – The passengers disperse - Tulloch

- Book VI: Chapter 7: Philadelphia – General Washington

- Book VI: Chapter 8: Comparison of Washington and Bonaparte

Book VI: Chapter 1: Prologue

London, April to September 1822. (Revised December 1846).

BkVI:Chap1:Sec1

Thirty-one years after embarking, as a mere second-lieutenant, for America, I embarked for London with a passport conceived in these terms: ‘Allow passage,’ said this passport, ‘allow passage to His Lordship the Vicomte de Chateaubriand, Peer of France, Ambassador of the King to His Britannic Majesty, etc., etc.’ No description; my grandeur was apparently such as to make my face known everywhere. A steamship, chartered for my sole use, brought me from Calais to Dover. In setting foot on English soil, on the 4th April 1822, I was saluted by the guns of the fort. An officer arrived on behalf of the Commandant to offer me a guard of honour. Reaching the Ship Inn, the landlord and servants received me with bare heads and hanging arms. Madame the Mayoress invited me to a soiree, in the name of the most beautiful ladies of the town. Monsieur Billing, attaché to my embassy, was waiting for me. A dinner of huge fish and monstrous quarters of beef revived Monsieur l’Ambassadeur, who had no appetite and was not in the least tired. The locals, gathered under my windows, filled the air with loud hurrahs. The officer returned, and without asking posted sentries at my door. Next day, after a lavish distribution of my master the King’s money, I set off on the road to London, to the roar of canon, in a light carriage, drawn by four fine horses driven at a lovely trot by two elegant postilions. My staff followed in other coaches; couriers dressed in my livery accompanied the cavalcade. We passed through Canterbury, attracting the eyes of John Bull, and the carriages we overtook. At Blackheath, a common once frequented by highwaymen, I found a newly built village. Soon the immense cap of smoke that covers the city of London appeared.

Plunging into the gulf of dark vapour, as if into one of the mouths of Tartarus, and crossing the whole town, whose streets I recognised, I arrived at the Embassy in Portland Place. The chargé d’affaires, Monsieur le Comte Georges de Caraman, the Embassy secretaries, Monsieur le Vicomte de Marcellus, Monsieur le Baron Élisée Decazes, Monsieur de Bourqueney, and the attachés welcomed me with dignified politeness. All the ushers, porters, valets and footmen of the Embassy were assembled on the pavement. I was handed the cards of the English ministers and foreign ambassadors who had already been informed of my imminent arrival.

On the 17th of May in the year of grace 1793, I had disembarked at Southampton for this same city of London, as an obscure and humble traveller from Jersey. No Mayoress had noticed my arrival; the Mayor of the town, William Smith, gave me, on the 18th, a travel permit for London, to which was attached an extract from the Aliens Bill. My description read as follows: ‘François de Chateaubriand, French officer in the emigrant army, five feet four inches high, thin shape, brown hair and pitted with the smallpox.’ I humbly shared the cheapest of carriages with several sailors on leave; I changed horses at the meanest of inns; I entered poor, ill, and unknown, the rich and famous city where Mr Pitt reigned; I lodged, at six shillings a month, under the laths of a garret which a Breton cousin had found for me, at the end of a little street off the Tottenham Court Road.

‘Ah! Monseigneur, how your life

Today, with every honour rife,

Differs from those happy times!’

However a different kind of obscurity has enveloped me in London. My political status has overshadowed my literary fame; there is not a fool in the three kingdoms who has not preferred Louis XVIII’s ambassador to the author of Le Génie du Christianisme. We will see how things turn out after my death, or after I have ceased to fill Monsieur the Duc Decazes’ place at the Court of George IV, a succession as strange as the rest of my life.

Since arriving in London as French Ambassador, one of my greatest pleasures has been to leave my carriage at the corner of the street, and wander on foot through the side streets that I once frequented, those poor working-class suburbs, where misfortune takes refuge under the protection of a like suffering, those obscure shelters which I haunted with my companions in distress, not knowing if I would have bread to eat next day, I whose table in 1822 groans under three or four courses. At all of those narrow, humble doors which in the past were open to me, I see only unfamiliar faces. I no longer meet my compatriots in the street, recognisable by their gestures; their walk; the age and style of their clothes; no longer notice those priestly martyrs, wearing their clerical collars; large three-cornered hats; and long threadbare black coats, whom the English would salute as they passed. Wide streets have been cut, lined with palaces, bridges constructed, walkways planted: Regent’s Park, near to Portland Place, occupies the site of the old meadows with their herds of cattle. A cemetery, seen from the window of one of my attic rooms, has vanished within the precincts of a factory. When I go to see Lord Liverpool, I find it hard to discover the place where Charles I’s scaffold stood; new buildings, closing in around the statue of Charles II, have encroached like forgetfulness itself on memorable events.

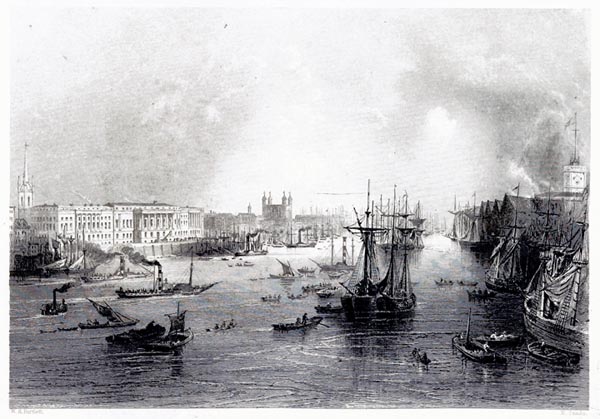

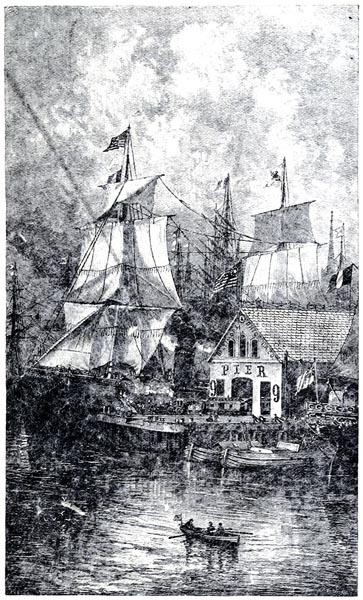

How I regret, in the midst of my insipid grandeur, that world of tribulation and tears, those times when my sorrows mingled with those of a colony of unfortunates! It is true then that everything changes, that misfortune ends even as prosperity does! What has become of my émigré brothers? Some are dead, others have suffered various fates: they have seen their friends and families vanish; they are less happy in their native country than they were in a foreign land. Had we not, in this country, our reunions, our diversions, our celebrations, above all our youth? Mothers, and young girls beginning their life in adversity, brought home the fruits of their labours, and went to join in some dance of their homeland. Attachments were formed after work, during the evening conversations, on the grass at Hampstead or Primrose Hill. In chapels, decorated by our own hands in old tumbledown buildings, we prayed together on the 21st of January and on the day of the Queen’s death, moved by a funeral oration given by the emigrant priest from our village. We strolled beside the Thames, to watch vessels charged with the world’s riches entering the docks, or to admire the country houses at Richmond, we so poor, we deprived of our paternal roof: all these things were true happiness!

‘The Port of London’

London, edited by C. K. - Charles Knight (p448, 1875)

The British Library

BkVI:Chap1:Sec2

When in 1822 I return home, instead of being met by a friend, shivering with cold, who opens the door of an attic to me familiarly, who beds down on a pallet next to mine, covering himself with a thin coat, with the moonlight for his lamp – I pass between two rows of lackeys, to the light of torches, to reach five or six respectful secretaries. I arrive, riddled with words along the way: Monseigneur, Milord, Your Excellency, Monsieur the Ambassador, at a drawing room draped with gold and silk.

– I beg you, Gentlemen, leave me! A truce to these Milords! What do you wish me to do? Go away, laugh in the Chancery, as if I were not here. Do you imagine you can make me take this masquerade seriously? Do you think me such a fool as to believe that I have changed my nature because I have changed my coat? The Marquis of Londonderry is coming to visit, you say; the Duke of Wellington has asked for me; Mr Canning is seeking me; Lady Jersey expects me to dinner with Lord Brougham; Lady Gwydir expects me at ten in her box at the Opera; Lady Mansfield at midnight at Almack’s –

Mercy! Where can I hide? Who will deliver me? Who will rescue me from this persecution? Return, you lovely days of misery and solitude! Live once more, companions of my exile! Come, old comrades of pallet and camp-bed, come to the countryside, to the little garden of some quiet tavern, drink a cup of bad tea on a wooden bench and talk of our foolish hopes, and our ungrateful land, speaking of our troubles, searching for ways to help one another, or to succour a relative of ours even more deserving than ourselves.

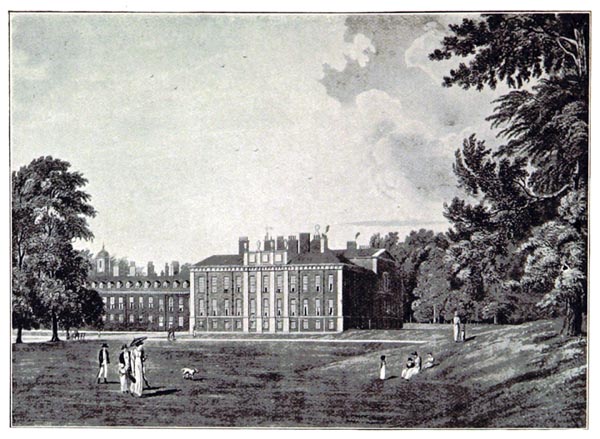

This is what I have felt, and what I have said to myself in these first days of my London embassy. I can only escape the melancholy that assails me beneath my own roof by saturating myself in the less oppressive melancholy of Kensington Gardens. The gardens have not changed, as I was able to reassure myself in 1843; only the trees have grown; always a solitary place, the birds build their nests here in peace. It is not even the fashion to meet here any more, as in the days when that loveliest of Frenchwomen, Madame Recamier, walked here accompanied by a throng. From the edge of the deserted lawns of Kensington, I love to watch the files of horses crossing Hyde-Park, and the carriages of fashionable young men, among which in 1822 appears my empty Tilbury, while I, once more the poor little émigré gentleman walk the path where the exiled confessor used to say his breviary.

‘South Front of Kensington Palace in 1819’

Kensington Palace, the Birthplace of the Queen, Illustrated - Ernest Law (p65, 1899)

The British Library

It was in Kensington Gardens that I planned the Essai Historique; it was there where, re-reading the journal of my travels overseas, I drew on it for the loves of Atala; it was there too, after wandering far and wide over the fields under a lowering sky, which turned yellow as if filled with polar light, that I pencilled out the first sketch of René’s passions. At night I deposited the fruit of my daydreams in the Essai Historique and Les Natchez. The two manuscripts advanced side by side, though I often lacked the money to buy writing paper, and for want of thread fastened the pages together with tacks pulled from the battens in my attic.

The site of my early inspirations commands me to feel its power; it casts the gentle light of my memories over the present: – I feel like taking up my pen once more. So many hours are wasted in embassies! I have no less time than in Berlin to continue my Memoirs, this edifice I am constructing from dead bones and ruins. My secretaries here in London want to go on picnics in the mornings and to balls at night; gladly! The footmen, Peter, Valentine, Lewis, in their turn head for the tavern, and the maids, Rose, Peggy, Maria, go for a walk through the streets; I am delighted. They have left me the key of the outer door: Monsieur the Ambassador remains in charge of the house; if anyone knocks, he will open for them. Everyone has gone; here I am, alone: let us set to work.

It was twenty-two years ago, as I have said, that I sketched out Les Natchez and Atala; I am at the precise point in my Memoirs at which I sailed for America: it is a perfect fit. Let us erase those twenty-two years, as they have in fact been erased from my life, and set off for the forests of the New World: the story of my Embassy will appear in its proper place, when God pleases; but provided I remain here for a few months, I shall have the time to travel from Niagara Falls to the Army of the Princes in Germany, and from the Army of the Princes to my retreat to England. The Ambassador of the King of France can recount the story of the French émigré in the very place where the latter spent his exile.

Book VI: Chapter 2: Ocean Passage

London, April to September 1822.

BkVI:Chap2:Sec1

The previous book ended with my embarkation at Saint-Malo. Soon we left the Channel, and immense waves from the west proclaimed the Atlantic to us.

It is hard for those who have never voyaged to gain an idea of the feelings one experiences on board ship, seeing nothing on every side but the solemn face of the deep. In the perilous life of a sailor there is an independence which is absent on land; one leaves the passions of men behind on shore; between the world one leaves and that which one seeks, one has for friendship and country only the element that supports one: mo more duties to fulfil, mo more visits to make, no more newspapers, no more politics. Even the language of sailors is no ordinary language: it is a language that speaks of oceans and skies, calms and storms. You inhabit a universe of water among creatures whose clothes, tastes, manners, faces resemble no earth-dwelling people: they possess the hardness of sea wolves and the lightness of birds; there is no trace of the worries of society on their brows; the wrinkles that traverse them resemble the pleats in a furled sail, and are less hollowed out by age than by the wind, as the waves are. The skin of these creatures, impregnated with salt, is reddened, rough as the surface of a reef lashed by the tide.

The sailors have a passion for their vessel; they cry with regret on leaving her, with tenderness on re-embarking. They are unable to remain with their families; after having sworn a hundred times not to expose themselves to the sea, it is impossible for them to ignore it, as a young man cannot tear himself from the arms of a faithless and volatile mistress.

On the dockside in London or Plymouth, it is not unusual to find sailors born on board ship: from infancy to old age, they never go on shore; they never see the land except from their floating cradle, spectators of a world they never enter. In that life reduced to small a space, under the clouds and above the depths, everything is alive to a mariner: an anchor, a sail, a mast, a canon are living things one has affection for and each of which has its history.

The sail was split on the coast of Labrador; the sail-maker added the patch you can see.

The anchor saved the vessel when it had dragged its other anchors, among the coral reefs of the Sandwich Isles.

The mast was broken in a squall off the Cape of Good Hope; it is not a single spar; it is much stronger since it was fashioned from two sections.

The canon is the only one not dismounted at the battle of the Chesapeake.

The news on board is most interesting: the lead has been cast; the ship is making ten knots.

The sky is clear at midday; the sun’s elevation has been taken; one is at such and such latitude.

Our position has been established: so many leagues have been gained along our ideal route.

The needle’s declination is so many degrees: we are reaching northwards.

The sand in the hourglass flows poorly: we will have rain.

Procellaria, stormy petrels, have been seen behind the vessel’s wake: we can expect a sharp gust.

Flying fish have appeared to the south: the weather will be calmer.

A break in the clouds has formed towards the west: it is the source of the wind; tomorrow the wind will blow from that quarter.

The water has changed hue; wood and sea-wrack can be seen floating; sea-gulls and ducks are visible; a little bird came and perched on a yard: the headland must be left behind, since we are nearing shore, and it is a bad idea to berth at night.

In the chicken-coop, there is a favourite cockerel that is sacred, so to speak, and has survived all others; he is famous for having crowed during battle, as if in the farmyard amongst his hens. Below deck a cat lives: its fur streaked with green, with a mangy tail, hairy whiskers, firm on its feet, countering the pitch and roll with its balancing act; it has been round the world twice, and was saved from shipwreck riding on a barrel. The ships’-boys give the cockerel biscuits soaked in wine, and Tomcat has the privilege of sleeping, when it pleases him, on the second captain’s fur mantle.

Old sailors resemble old ploughmen. The fruits of their labour are different, it is true; the sailor has led a wandering life, the ploughman has never left his fields; but they both know the stars and predict the future while cutting their furrow. To the one belongs the skylark, the red-breast, the nightingale; to the other the petrel, the curlew, the halcyon – their prophets. They retire for the night, one to his cabin, the other to his cottage; frail habitations, where the hurricane that shakes them has no effect on tranquil consciences.

‘If the wind tempestuous is blowing,

Still no danger they descry;

The guileless heart its boon bestowing,

Soothes them with its Lullaby.’

The sailor knows not where death will surprise him, on which shore he will lose his life: perhaps, when he has given his last sigh to the breeze, he will be thrown into the heart of the waves, attached to two oars, to continue his voyage, perhaps he will be cast on some desert island that no one will never find again, just as he has slumbered alone in his hammock, in the midst of the ocean.

The lone vessel is a fine sight: responding to the lightest touch of the tiller, a hippogriff or winged courser, obedient to the pilot’s hand, like a horse under the hand of a rider. The elegance of the masts and rigging, the agility of the sailors as they scramble along the yards, the different aspects in which the ship presents itself, leaning into a hostile southerly, or fleeing swiftly before a favourable northerly, make this sentient structure one of the wonders of human ingenuity. Now the foaming wave strikes and spurts against the hull; now the peaceful waters divide, without resistance, before the prow. Flags, flames, sails complete the beauty of this palace of Neptune: the lowest sails, deployed to their full width, swell like vast cylinders; the topsails, reefed in the middle, resemble the breasts of a Siren. Animated by an impetuous breeze, the ship with its keel, as with the blade of a plough, cuts with a loud noise through the fields of the sea.

On this pathway through the ocean, along whose length one sees neither tree nor village, town nor turret, spire nor tomb; on this road without signposts or milestones, which has only the waves for markers, only the winds for intermediaries, only the stars for lanterns, the finest of events, when one is not in search of unknown lands and seas, is the meeting of two vessels. Each discovers the other far-off on the horizon; they steer towards each other. The passengers and crew rush to the bridge. The two boats draw near, hoist their flags, and furl their sails to lie parallel. When all is quiet, the two captains, standing on the poop, hail each other with a megaphone: ‘What name? Out of what Port? Your captain’s name? Where from? How many days crossing? Latitude and longitude? Adieu, away!’ They let go a reef; the sail unfurls. The sailors and passengers from the two vessels watch each other depart, without saying a word: these go to seek the sun of Asia; those, the sun of Europe, which will equally oversee their death. Time carries off and separates voyagers on land, still more swiftly than the wind carries them away and separates them on the ocean; they make a sign from afar: Adieu, away! The common harbour is Eternity.

And what if the vessel met with was that of Cook or La Pérouse?

BkVI:Chap2:Sec2

The boatswain of our vessel was an old supercargo named Pierre Villeneuve, whose name itself pleased me because of my own kindly nurse Villeneuve. He had served in India under Bailli de Suffren, and in America under the Comte d’Estaing; he had been involved in countless engagements. Leaning against the bows of the ship, near the bowsprit, like an army veteran sitting beneath a garden trellis in the moat of the Invalides, Pierre, chewing a plug of tobacco that swelled his cheek like a gumboil, described the moment when the decks are cleared, the effect of gunfire below-deck, and the havoc caused by cannonballs ricocheting against the gun-carriages, guns and timber-work. I made him tell me of the Indians, Negroes and planters. I asked him how the people were dressed, about the nature of the trees, the colour of earth and sky, the taste of the fruit; whether pineapples were superior to peaches, palm-trees finer than oaks. He explained all this to me by means of comparisons with things I knew: the palm-tree was a giant cabbage, an Indian woman’s dress like my grandmother’s; camels looked like hunch-backed donkeys; all the peoples of the Orient, especially the Chinese, were cowards and thieves. Villeneuve was a Breton, and we never failed to end by praising the incomparable beauty of our native land.

The bell would interrupt our conversations; it struck the watches, and the hours for dressing, roll-call and meals. In the morning, at a signal, the crew lined up on deck, stripped off their blue shirts, and donned others drying in the shrouds. The discarded shirts were immediately washed in tubs, in which this school of seals also soaped their sunburnt faces and tarry paws.

At the midday and evening meals, the sailors, sitting in a circle round the mess-can, dipped their spoons, one after the other and without cheating, into the soup which splashed about to the rolling of the ship. Those who were not hungry sold their share of biscuit and salt meat to their mates, for a plug of tobacco or a glass of brandy. The passengers ate in the captain’s cabin. When it was fine, a sail was spread above the stern, and we ate with a view of the blue sea, flecked here and there with white marks where it was stirred by the breeze.

Wrapped in my cloak, I stretched out at night on deck. My eyes contemplated the stars above. The swollen sail conveyed the coolness of the breeze to me, which rocked me beneath the celestial dome: half-asleep and driven onwards by the wind, the sky changed with my changing dreams.

The passengers on board ship offer an alternative society to that of the crew: they belong to another element; their destinies are earthbound. Some hasten to seek their fortunes, others rest; those return to their homeland, these leave theirs behind; still others voyage to research the ways of other peoples, to study the sciences and the arts. One has the leisure to learn in this floating hotel that travels with the traveller, to hear of many things, to conceive antipathies, and contract friendships. When those young women come and go, born of English and Indian blood, who combine the beauty of Clarissa and the delicacy of Sakuntala, then those necklaces are formed which knot and un-knot the perfumed breezes of Ceylon, as light and gentle as they are themselves.

Book VI: Chapter 3: Francis Tulloch – Christopher Columbus - Camoëns

London, April to September 1822.

BkVI:Chap3:Sec1

Among my fellow-passengers was a young Englishman. Francis Tulloch had served in the artillery; painter, musician and mathematician, he spoke several languages. The Abbé Nagot, the Superior of the Sulpiciens, had met the Anglican officer and made him a true Catholic: he was taking his neophyte to Baltimore.

I befriended Tulloch: as I was a convinced free-thinker at that time, I urged him to return to his parents. The sight we had before our eyes aroused his admiration. We would rise at night, when the deck was given over to the officer of the watch and a few sailors silently smoking their pipes: Tuta aequora silent: the sea calm and silent. The ship rolled at the mercy of the slow and noiseless waves, while sparks of fire coursed with the white foam along her sides. Thousands of stars shining in the sombre azure of the celestial dome, a shore-less sea, infinity in the sky and on the waters! God never impressed me with his greatness more than in those nights when I had immensity over my head and immensity under my feet.

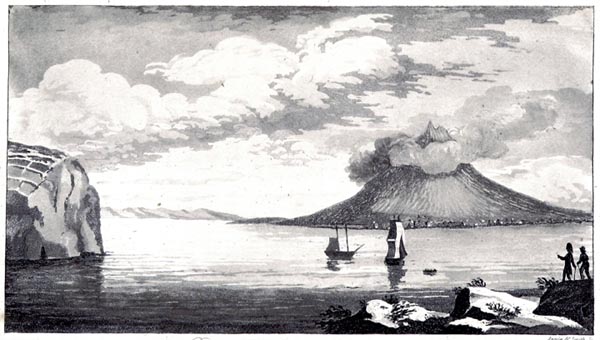

Westerly winds, interspersed with calms, delayed our progress. By the 4th of May we had got no farther than the Azores. On the 6th, at about eight in the morning, we caught sight of the island of Pico; this volcano long dominated unknown seas: a vain beacon by night, an unseen landmark by day.

‘Pico and St George from Fayal’

A Description of the Island of St. Michael - John White Webster (p257, 1821)

The British Library

There is something magical in the sight of land rising from the depths of the sea. Christopher Columbus, in the midst of his mutinous crew, ready to return to Europe without having achieved the purpose of his voyage, saw a little light, on a beach hidden from him by the night. The flight of birds had guided him towards America; the glow from a savage hearth revealed a new universe to him. Columbus must have experienced the kind of feeling that Scripture grants to the Creator, when, having drawn the earth from nothingness, he saw that his work was good: vidit Deus quod esset bonum. Columbus created a world. One of the first lives of the Genoan navigator is that which Giustiniani, in publishing his Hebrew Psalter, placed as a note beneath the psalm: Caeli enarrant gloriam dei: the heavens declare the glory of God.

Vasco da Gama must have been no less amazed, when in 1498 he touched the coast of Malabar. Then, everything in the world altered: nature appeared anew; the curtain, which had hidden part of the earth for thousands of centuries, lifted: the house of the sun was discovered, the place from which he rose each morning ‘like a bridegroom, or a giant, tanquam sponsus, ut gigas’. The wise and gleaming Orient was seen in all its nakedness, that Orient whose mysterious history involved the voyages of Pythagoras, the conquests of Alexander, the memory of the crusades, and whose perfumes crossed the deserts of Arabia and the seas of Greece to reach us. Europe sent a poet there to praise it: the swan of the Tagus sounded his sad and beautiful voice on the shores of India; Camoëns borrowed their brilliance, their renown and their misfortune; he only left them their riches.

Book VI: Chapter 4: The Azores – The Island of Graciosa

BkVI:Chap4:Sec1

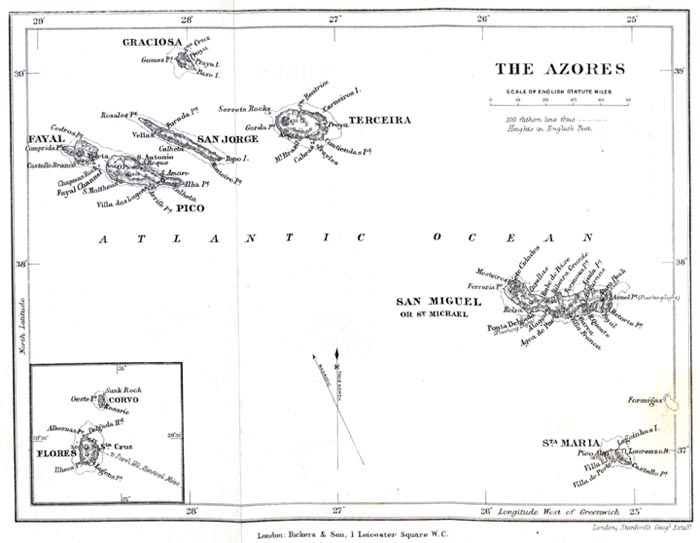

When Gonzalo Villo, Camoëns’ maternal grandfather, discovered part of the Azores archipelago, he should, if he had foreseen the future, have reserved a six foot plot of earth to cover the bones of his grandson.

‘The Azores’

A Visit to the Azores. With a Chapter on Madeira - Julia Anne Elizabeth Roundell (p20, 1889)

The British Library

We anchored in a poor roadstead with a rocky bottom, in forty-five fathoms of water. The island of Graciosa, in front of which we moored, displayed hills swelling a little in outline like the ellipses of an Etruscan amphora: they were draped in the green of their cornfields, and gave off a pleasant odour of wheat peculiar to the harvests of the Azores. In the midst of these tapestries we could see the boundaries of the fields, formed of volcanic stone, half-black and half-white, and piled one on top of another. An abbey, monument of an old world on new soil, crowned the summit of a mound; at the foot of this mound, the red roofs of the town of Santa Cruz were mirrored in a pebbly creek. The whole island, with its indentations of bays, capes, coves and promontories, replicated its inverted landscape in the sea. As an outer defence it had a girdle of rocks jutting vertically from the waves. In the background, the volcanic cone of Pico, planted on a cupola of clouds, pierced the aerial perspective beyond Graciosa.

It was decided that I should go ashore with Tulloch and the mate; the longboat was lowered into the water: it was rowed to the shore which was about two miles away. We saw some movement on the beach; a flat-bottomed boat advanced towards us. As soon as it was within earshot, we made out a number of monks on board. They hailed us in Portuguese, Italian, English and French, and we replied in all four languages. The alarm bell was ringing: our vessel was the first large sailing ship that had ventured to anchor in the dangerous roadstead where we were riding the tide. What is more, the islanders were seeing a tricolour flag for the first time: they wondered if we were corsairs from Algiers or Tunis! Neptune had not recognised the standard carried so proudly by Cybele. When they saw we had human forms, and understood what was said to us, their joy was extreme. The monks helped us into their boat, and we rowed gaily towards Santa Cruz: we landed there with some difficulty, because of the violence of the surf.

The whole island ran to meet us. Four or five alguazils (Portuguese warrant-officers), armed with rusty pikes, took charge of us. The uniform of His Majesty attracted the honours in my direction, and I was taken for the most important member of the delegation. We were escorted to the Governor’s residence, a hovel, where His Excellency wearing a shabby green uniform, which had once possessed gold lace, granted us solemn audience: he gave us permission to re-victual.

The monks took us to their monastery, a roomy well-lit building with balconies. Tulloch had found a fellow countryman: the principal brother, who did everything to accommodate us, was a sailor from Jersey, whose ship had gone down with all hands off Graciosa. Sole survivor of the wreck, and not lacking in intellect, he had become a willing pupil of the catechists; he had learnt Portuguese and a few words of Latin; his English origins had told in his favour, they had converted him and made a monk of him. The sailor from Jersey found it much more to his liking to be lodged, clothed and boarded at the altar than to climb the rigging to take in the mizzen topsail. He still remembered his former trade: since it was a long time since he had heard his language spoken, he was delighted to meet someone who understood it; he laughed and swore like a true acolyte. It was he who showed us over the island.

The houses in the villages, built of wood and stone, were adorned with outer galleries which gave a clean look to these huts because they let in a great deal of light. The peasants, nearly all of them vine-growers, were half-naked, and bronzed by the sun; the women, small and yellow-skinned like mulattoes, but lively, were naively coquettish with their bouquets of mock-orange, and their rosaries worn as coronets or necklaces.

The hillsides were covered with vine-stocks, the wine obtained from which resembled that of Fayal. Water was scarce, but wherever a spring welled a fig tree grew and there was an oratory with a portico painted in fresco. The arches of the portico framed views of the island and the sea. It was on one of these fig trees I saw a flock of blue teal settle, a species lacking webbed feet. The tree had no leaves, but it bore red fruit set like crystals. When it was adorned with the cerulean birds, with wings at rest, its fruits appeared bright crimson, while the tree seemed to have suddenly sent out azure foliage.

It is likely that the Azores were known to the Carthaginians; certainly Phoenician coins have been uncovered on the island of Corvo. They say that the modern navigators who first landed on the island found an equestrian statue, the right arm extended and pointing towards the west, if, that is, the statue is not merely the engraved design which decorates ancient prints of harbours.

I have it, in the manuscript of Les Natchez, that Chactas returning from Europe touched land at the island of Corvo, and that he there encountered the mysterious statue. He expresses the feelings which filled me on Graciosa, recalling the legend: ‘I approached this extraordinary monument. On its base, bathed with foam from the waves, unknown characters were engraved: the moisture and saltpetre of the waters had eaten into the surface of the ancient bronze; the Halcyon, perched on the helmet of the colossus, uttered, at intervals, languid cries; molluscs had stuck to its sides and in its steed’s bronze mane, and when one approached the grooves of its flaring nostrils, one imagined one heard confused rumours.’

A good supper was served to us by the monks, after our excursion; we spent the night drinking with our hosts. Next day, about noon, our stores having been loaded, we returned on board. The monks were entrusted with our letters for Europe. The ship had been placed in danger by a strong south-westerly which had risen. We weighed anchor: but it was caught and lost among the rocks as anticipated. We set sail; the wind continued to freshen, and soon we left the Azores behind.

Book VI: Chapter 3: Ocean customs – The Island of Saint-Pierre

London, April to September 1822.

BkVI:Chap5:Sec1

‘Fac pelagus me scire probes, quo carbasa laxo: Muse, help me show how I know this sea where I deploy my sail.’

Those are the words of Guillaume le Breton, my compatriot, six hundred years ago. At sea again, I began to contemplate its solitudes once more; but across the ideal world of my reveries, like stern instructors, France and real events passed. My daily retreat, when I wished to evade the other passengers, was the maintop; I climbed to it nimbly to the applause of the sailors. I sat there overlooking the waves.

Space laid out in dual azure had the look of a canvas ready to receive some great painter’s imminent creation. The colour of the waves was like liquid glass. Broad and deep undulations appeared in their ravines, escaping from sight in the deserts of the Ocean: those quivering landscapes made the comparison meaningful to me that Scripture draws between the Earth reeling before the Lord, and a drunken man. Sometimes, one would have said that space was narrow and bounded, without projecting points; but if a wave chanced to raise its head, the flood curved in imitation of a distant shore, until a school of dog-fish swam past on its horizon, so creating a scale of measurement. Its expanse revealed itself, especially when mist, creeping over the pelagian surface, seemed to increase its immensity even further.

Descending from the mast’s eyrie, as I once used to descend from my nest in the willow-tree, forever constrained to my solitary existence, I would eat a ship’s biscuit, and a little sugar and lemon; then, I would lie down to sleep, on deck wrapped in my cloak, or below deck in my bunk: I had only to stretch my arm to reach from my bed to my coffin.

The wind forced us northwards and we made the Banks of Newfoundland. Floating icebergs were drifting in the midst of a pale cold drizzle.

![Newfoundland [Detail]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Chateaubriand/interior_chateaubriand_memoirs_bk6chap5sec1.jpg)

‘Newfoundland [Detail]’

The British Colonies; Their History, Extent, Condition, and Resources - Robert Montgomery Martin (p259, 1851)

The British Library

The men of the trident have customs handed down to them by their predecessors: when you cross the Line, you must resign yourself to receiving baptism; the same ceremony takes place in the Tropics as on the Banks of Newfoundland, and wherever the location, the leader of the masque is always the Old Man of the Tropics. Tropical and dropsical are synonymous terms to sailors: so the Old Man of the Tropics has an enormous paunch; he is dressed, even when he is in his native Tropics, in all the sheepskins and fur jackets the crew can muster. He squats in the maintop, giving a roar every now and then. Everybody gazes up at him: he starts to clamber down the shrouds, clumsy as a bear, stumbling like Silenus. As he sets foot on deck, he utters fresh roars, gives a bound, seizes a pail, fills it with sea-water, and empties it over the heads of those who have never crossed the Equator or never reached the latitude of icebergs. You may flee below deck, leap onto the hatches, or climb the masts: the Old Man pursues you; they end with a generous tip, these games of Amphitrite, that Homer would have celebrated, just as he sang of Proteus, if old Oceanus had been known in his entirety in Ulysses’ time; but at that time only his head was visible at the Pillars of Hercules; his body, hidden, covered the world.

BkVI:Chap5:Sec2

We steered for the islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, seeking a new port of call. When we approached the former, one morning between ten and midday, we were almost on top of it; its coast showed like a black hump through the mist.

We anchored in front of the capital of the island: we could not see it but we could hear the noises onshore. The passengers hastened to disembark; the Superior of Saint-Sulpice, continuously plagued by sea-sickness, was so feeble he had to be carried to land. I took lodgings apart from the others; I waited for a squall to blow away the fog, and show me the place I inhabited, and the faces so to speak of my hosts in this country of shadows.

The port and roadstead of Saint-Pierre are set between the east coast of the island and an elongated islet called the Île aux Chiens, the Isle of Dogs. The port, known as the Barachois, stretches inland and ends in a brackish pool. Some barren rounded hills are crowded together in the centre of the island: one or two, standing apart, overhang the sea; the rest have a fringe of levelled peaty moor-land at their feet. The look-out hill can be seen from the town.

‘Saint-Pierre: Vue Générale’

La France et les Colonies, Illustré - Onésime Reclus (p501, 1887)

The British Library

The Governor’s house faces the wharf. The church, the rectory, the chandler’s shop are all in the same area; next there are the houses of the naval commissioner and the harbour-master. Then the town’s only street begins, which runs across the pebbles along the beach.

I dined with the Governor two or three times, an extremely polite and obliging officer. He grew European vegetables on the hillside. After dinner he showed me what he called his garden.

A sweet and delicate scent of heliotrope rose from a small bed of flowering beans; it was not wafted to us by a breeze from home, but by a wild Newfoundland wind, unrelated to that exiled plant, and lacking the kindliness of reminiscence and delight. In this perfume, no longer breathed in by beauty, purified in its breast, nor diffused in its wake, in this perfume of another dawn, another world, another culture, was all the melancholy of regret, absence, youth.

From the garden, we ascended the hills, and halted at the foot of the flagpole in front of the lookout. The new French flag floated over our heads; like Virgil’s women we gazed at the sea, flentes, in tears. It separated us from our native land! The Governor was troubled; he belonged to the defeated side; moreover he was bored in this retreat, which was fine for a dreamer like me, but a harsh abode for a man interested in public affairs, unaffected by that all-absorbing passion which can banish the rest of the world from sight. My host enquired about the Revolution, while I asked him for news of the North-West Passage. He was at the edge of the wilderness, but he knew nothing of Eskimos and received nothing from Canada but partridges.

BkVI:Chap5:Sec3

One morning, I went alone to the Cap-à-l’Aigle, to see the sun rise in the direction of France. There, a glacial stream formed a waterfall whose last leap reached the sea. I sat on a rocky ledge, feet dangling over the water that foamed at the base of the cliff. A young fisher-girl appeared on the upper slopes of the hill; she had bare legs, despite the cold, and was walking through the dew. Tufts of her dark hair showed through from under the Indian kerchief in which her head was bound; over this kerchief she wore a hat made of local reeds shaped like a boat or a cradle. A bunch of purple heather showed at her breast which was outlined by the white fabric of her chemise. From time to time she stooped to gather the leaves of an aromatic plant known in the islands as natural tea. With one hand she dropped these leaves into a basket which she held in the other. She saw me: unafraid, she came to sit beside me, with her basket next to her, and began watching the sun as I was, her legs dangling above the sea.

We remained without speaking for a few minutes; at last, I showed myself the bolder, and said: ‘What are you gathering, there? The season for blueberries and cranberries is over.’ She raised two large dark eyes, shyly and proudly, and replied: ‘I was picking tea.’ She showed me her basket. ‘You are taking the tea home to your mother and father? – My father is away fishing with Guillaumy. – What do you do on this island in winter? – We make nets, we fish the lakes by breaking holes in the ice; on Sundays, we go to Mass and Vespers, where we sing hymns; and then we play in the snow and watch the boys hunting polar bears. – Will your father be back soon? –

Oh, no! The captain is taking the boat to Genoa with Guillaumy. – But Guillaumy will be back? – Oh, yes! Next season, when the fishermen return, amongst his novelties, he is going to bring me a striped silk bodice, a muslin petticoat, and a black necklace. – And you will be adorned for the wind, the mountain and the sea. Would you like me to send you a bodice, a petticoat and a necklace? – Oh, no!’

She rose, took up her basket, and ran down a steep path, beside a fir-grove. She was singing a Mission hymn in a sonorous voice:

‘All burning with immortal ardour,

It is toward God my wishes tend.’

On her way she scattered some lovely birds called egrets because of the tufts on their heads; she looked as though she was one of their number. Reaching the sea, she leap into a boat, loosed the sail, and sat down at the rudder; one might have taken her for Fortune: she sailed away from me.

Oh, yes! Oh, no, Guillaumy! The image of the young sailor out on a yard, in the midst of the wind, changed the dreadful rock of Saint-Pierre into a land of delights:

‘L’isola di Fortuna ora vedete: Now you may see the Fortunate Isles.’

We spent fifteen days on the island. From its desolate shores one can see the even more desolate coast of Newfoundland. The hills inland extend in divergent chains, of which the most elevated stretches north towards Rodrigue Bay. In the valleys, granite rock, containing red and greenish mica, is colonised by mats of sphagnum moss, lichen, and broom mosses (dicranum).

Small lakes are fed by the inflow of streams from La Vigie, Le Courval, Le Pain de Sucre, Le Kergariou, and La Tête Galante. These pools are known as Les Étangs du Savoyard, Le Cap Noir, Le Ravenel, Le Colombier, and Le Cap à l’Aigle. When gusts of wind stir these lakes they divide the shallows laying bare here and there stretches of drowned meadowland which are suddenly hidden again by the re-woven veil of water.

The flora of Saint-Pierre is like that of Lapland and the Straits of Magellan. The count of plant species diminishes towards the Pole; at Spitsbergen, one finds less than forty species of flowering plant (phanerogams). Species of plants vanish with changing location: northern ones, growing on the frozen steppes, become in the south the offspring of mountains only; others, nourished by the calm atmosphere of the densest forests, decreasing in height and strength, die on storm-tossed ocean shores. On Saint-Pierre, the marsh blueberry (vaccinium fuliginosum) is reduced to the state of knotgrass; it is soon lost in the wads and pads of moss that serve as humus. A wandering plant, I have made my own preparations for merging into the seacoast where I was born.

The slopes of the hillocks on Saint-Pierre are clothed with balsam fir, amelanchier, gaultheria, larch, and black fir, whose buds are used to produce anti-scorbutic ale. These ‘trees’ do not exceed the height of a man. The ocean winds pollard them, rock them, and bend them like ferns; then gliding beneath these forests of undergrowth, raise them again; but it finds no trunks, branches, arches, no echo of its moaning and makes no more noise there than it does over a moor.

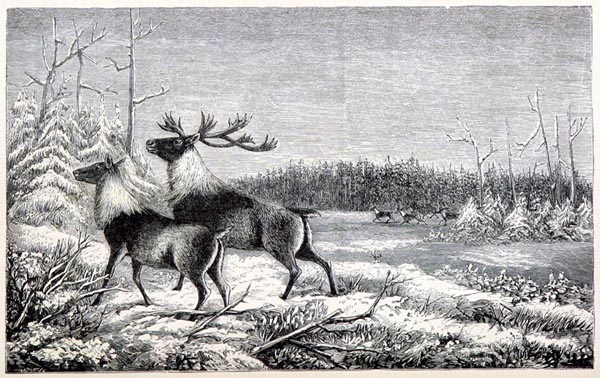

These stunted woods contrast with the tall woods of Newfoundland on the neighbouring shore, whose firs carry silvery lichen (alectoria trichodes): the polar bears seem to have snagged their fur on the branches of these trees, making strange climbers of themselves. The swamps of that island explored by Jacques Cartier, reveal paths trodden by these bears: you think you are looking at the rural tracks round a sheep-fold. The calls of hungry creatures sound all night; the traveller is only reassured by the no less sad sound of the sea; those waves, so harsh and unsociable, become friends and companions.

‘On the Barrens’

Newfoundland, its History, Present Condition and Prospects - Joseph Hatton (p178, 1883)

The British Library

The northern tip of Newfoundland is at the same latitude as Labrador’s Cape Charles; a few degrees higher the Polar landscape begins. If we are to believe the travellers, there is a charm to these regions: in the evening, the sun, touching the earth, seems to halt motionless, and soon climbs the sky again instead of dropping below the horizon. The mountains covered in snow, the valleys embroidered with white moss browsed by the reindeer, the seas full of whales and dotted with icebergs, the whole landscape glowing as if illumined simultaneously by the fires of the setting sun and the light of dawn: one does not know if one is present at the beginning of the world or its end. A little bird, similar to one which sings at night in our own woodlands, makes his plaintive song heard. Then love draws the Eskimo onto the frozen rocks where his companion waits: these human nuptials, at the ends of the earth, are not lacking in joy or ceremony.

Book VI: Chapter 6: The Virginian Coast – The setting sun – Peril – I land in America – Baltimore – The passengers disperse - Tulloch

London, April to September 1822.

BkVI:Chap6:Sec1

After taking on provisions and replacing the anchor lost at Graciosa, we left Saint-Pierre. Sailing south, we reached 38 degrees latitude. We were becalmed not far off the coasts of Maryland and Virginia. The misty skies of the northern regions had been succeeded by the clearest of skies; we could not see land, but the odour of the pine-forests reached us. Daybreak and dawn, sunrise and sunset, dusk and nightfall were all admirable. I was never weary of gazing at Venus, whose rays seemed to envelop me as my sylph’s tresses had long ago.

One evening, I was reading in the captain’s cabin; the bell sounded for prayers: I went to add my vows to those of my companions. The officers occupied the poop with the passengers; the chaplain, book in hand, was a little way from us near the tiller: we were standing, facing the prow of the vessel. All the sails were furled.

The sun’s disc, ready to plunge into the waves, appeared amongst the rigging in the midst of boundless space: one would have said, because of the motion of the ship, that the radiant star altered its relationship to the horizon each instant. When I drew this picture, which you can re-read in its entirety, in Le Génie du Christianisme, my religious sentiments were in harmony with the scene; but, alas, when I was there in person, the unconverted man was alive in me! It was not God alone whom I contemplated above the waves in the magnificence of his works. I saw an unknown woman and the miracle of her smile; the beauties of the heavens seemed born from her breath; I would have given eternity for one of her caresses. I imagined that she was throbbing behind that veil of the universe which hid her from my eyes. Oh! If it had only been in my power to tear away that curtain and press that ideal woman to my heart, and be consumed on her breast in that love, the source of my inspiration, my despair and my existence! While I was indulging in these impulses so fitting to my future career as a trapper, it nearly happened that an accident put an end to my dreams and plans.

The heat was overpowering; the vessel, in a dead calm, and weighed down by its masts, was rolling heavily: roasting on deck and wearied by the motion of the ship I decide to bathe, and though we had no boat out, I dived from the bowsprit into the sea. All went well to begin with, and several passengers followed my example. I swam about without glancing at the ship; but when I chanced to turn my head, I saw that the current had carried her some way off. The sailors, alarmed by this, had thrown a rope to the other swimmers. Sharks appeared in the ship’s wake, and shots were fired at them to scare them off. The swell was so heavy, that it prevented my return, while exhausting my strength. There was a whirlpool beneath me, and at any moment the sharks might have made off with an arm or a leg. On board, the boatswain tried to lower a boat into the sea, but the tackle had to be rigged first, and this took a considerable time.

By the greatest good luck, an almost imperceptible breeze sprang up; the ship, answering a little to the helm, approached me; I was able to catch the end of the rope; but my companions in foolhardiness were already clinging to it; when we were dragged to the ship’s side, I was at the end of the line, and they bore down on me with all their weight. They fished us up in this way one by one, which took a long time. The rolling continued; at every alternate roll, we plunged six or seven feet in the water, or were suspended as many feet in the air, like fish on the end of a line: at the last immersion I felt as I were about to faint; one more roll, and it would have been all over. I was hoisted on deck half-dead: if I had been drowned, what good riddance for me and everyone else!

BkVI:Chap6:Sec2

Two days after this incident, we were in sight of land. My heart beat wildly when the captain pointed it out to me: America! It was barely indicated by the tops of a few maple trees above the horizon. The palm-trees at the mouth of the Nile have indicated the shores of Egypt to me since, in the same way. A pilot came on board; we entered Chesapeake Bay. That evening a boat was sent ashore to obtain fresh provisions. I joined the party and soon trod American soil.

Casting my gaze around me, I remained motionless for a few moments. This continent, possibly unknown to both ancient times and a series of modern centuries; the first savage destiny of that continent, and its second destiny since the arrival of Christopher Columbus; the supremacy of the European monarchies shaken by this new world; an old social order ending in this young America; a republic of a new kind announcing a change in the human spirit; the part my country had played in these events; the seas and shores owing their independence in part to French blood and the French flag; a great man issuing from the midst of wilderness and discord; Washington at home in a flourishing city, on the same spot where William Penn had bought a patch of forest; the United States passing to France that Revolution which France had supported with her arms; lastly my own plans, the virgin muse I had come here to deliver to the passion of a new Nature; the discoveries I hoped to make in the deserts that still extended their vast kingdom behind the limited rule of a foreign civilisation: such were the thoughts that revolved in my mind.

We walked towards a house. Woods of balsam and Virginian cedar, mocking-birds and cardinal tanagers proclaimed, by their shade and appearance, their song and colour, another clime. The house, which we reached after half-an-hour, was a mixture of English farm house and Creole hut. Herds of European cattle grazed in pasture land enclosed by fencing on which striped squirrels were playing. Black people were sawing timber, whites were tending tobacco plants. A Negress, thirteen of fourteen years old, almost naked and singularly beautiful, opened the gate of the enclosure for us like a young Night. We bought some maize cakes, chickens, eggs and milk, and returned to the ship with our baskets and demijohns. I gave my silk handkerchief to the little African girl: it was a slave who welcomed me to the land of liberty.

BkVI:Chap6:Sec3

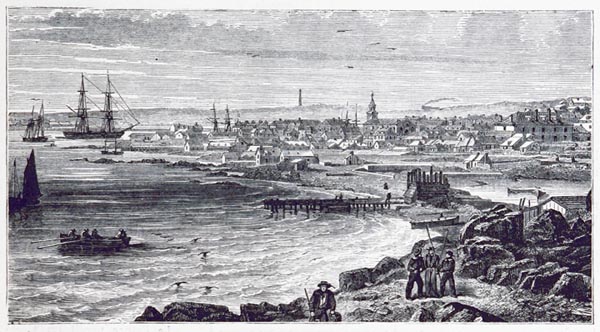

We weighed anchor to head for the roads and port of Baltimore: approaching them the waters narrowed; they were smooth and still; we seemed to be sailing up an indolent river lined with Avenues. Baltimore appeared as if it lay at the far end of a lake. Facing the town was a wooded hill, at the foot of which they were beginning to build. We moored alongside the quay. I slept on board and did not go ashore till the next day. I went with my luggage to the inn; the seminarists retired to the establishment prepared for them, from which they have since scattered throughout America.

‘Locust Point, Baltimore’

The Port of Baltimore in 1882, Including a Chart of the Chesapeake Bay - Henry O Haughton (p33, 1882)

The British Library

What became of Francis Tulloch? The following letter was delivered to me in London, on the 12th of April 1822:

‘Thirty years have passed, my dear Viscount, since the era of our voyage to Baltimore, and its quite possible you have even forgotten my name; but if I trust to the sentiments of my heart, which have always remained loyal and true to you, it is not so, and I flatter myself you would not be unhappy at seeing me once more. Though we live opposite one another (as you will see from the address of my letter), I am only too well aware how many things separate us. But witness the least desire to see me, and I will be happy to prove to you, as far as I can, that I am still as I have always been, your faithful and devoted,

Francis Tulloch

P. S. The distinguished rank you have achieved and which has conferred on you so many titles is before my eyes; but the memory of the Chevalier de Chateaubriand is so dear to me, that I cannot write to you (at least on this occasion) as Ambassador etc.,etc. So, forgive the style for the sake of our old friendship.

Friday 12th April,

Portland Place, No. 30’

So Tulloch was in London; he did not become a priest at all, he is married; his adventures have ended like mine. The letter weighs in favour of the truth of my Memoirs and the accuracy of my memories. Who could have evidenced an alliance and friendship formed thirty years ago at sea, if the other party had not re-appeared? And what a sad backward perspective this letter unrolls! Tulloch, in 1822, lived in the same city as me, in the very same street; the door of his house faced mine, just as we met on the same vessel, on the same deck, our cabins facing one another. How many other friends of mine I shall never see again! Every night as he goes to his rest, a man can count his losses: only his years never leave him, even though they pass; when he reviews them and calls their numbers, they reply: ‘Present!’ Not one fails the call.

Book VI: Chapter 7: Philadelphia – General Washington

London, April to September 1822.

BkVI:Chap7:Sec1

Baltimore, like all the other capitals of the United States, did not then possess its present extent: it was a pretty little Catholic town, ordered and lively, whose social mores bore a close resemblance to those of Europe. I paid the captain my passage-money, and gave him a farewell dinner. I booked my seat in a stage-coach which made the journey to Pennsylvania three times a week. At four in the morning I climbed in, and found myself rolling along the highways of the New World.

The route we followed, more marked out than made, crossed fairly flat country: there were hardly any trees, few farms, and scattered villages, the climate being French, with swallows flying over the water as they did over the pond at Combourg.

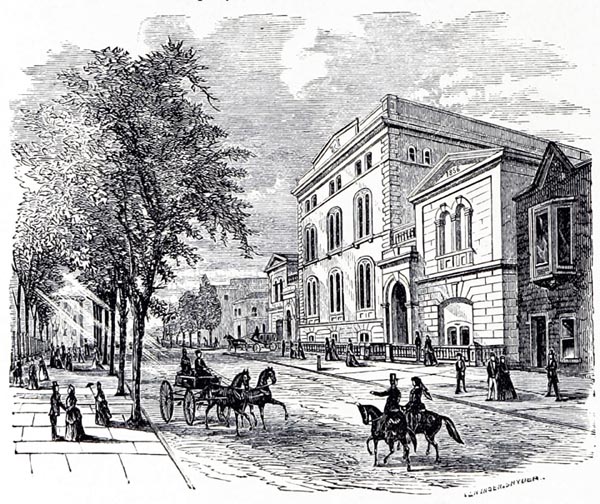

Near Philadelphia, we met farm-workers going to market, and public and private carriages. Philadelphia struck me as a fine town, with wide streets, some planted with trees, intersecting at right-angles in a regular pattern, north-south, and east-west. The Delaware River runs parallel to the street which follows its west bank. This river would be regarded as considerable in Europe: in America they barely mention it; its banks are low, and not picturesque.

‘East Rittenhouse Square’

Philadelphia and its Environs, Appendix (p50, 1876)

The British Library

At the time of my journey in 1791, Philadelphia had not yet been extended as far as the Schuylkill River; the ground, in the direction of that tributary, was divided into lots, on which houses were being built here and there.

Philadelphia’s appearance is monotonous. In general, what are lacking in the Protestant cities of the United States are great works of architecture: the Reformation, young in years, sacrificing nothing to the imagination, has rarely erected those domes, airy naves, and twin spires with which the Catholic religion has garlanded Europe. Not one monument in Philadelphia, New York, or Boston, soars above the mass of roofs and walls: the eye is saddened by this uniform level.

First putting up at an inn, I later took a room in a boarding-house where San Domingo planters, and Frenchmen who had emigrated, possessing other ideas than mine, lodged. A land of liberty offered asylum to those fleeing from liberty: nothing proves the high worth of generous institutions more than this voluntary exile of the supporters of absolute power to a pure democracy.

Anyone, arriving like myself in the United States, full of enthusiasm for the people of classical times, a Cato, seeking everywhere the severity of early Roman life, was bound to be shocked by the luxurious carriages, the frivolous conversation, the inequality of wealth, the immorality of the banks and gaming houses, and the noisy ballrooms and theatres. In Philadelphia I could easily have thought myself in Liverpool or Bristol. The people there were attractive: the Quaker girls with their grey dresses, their uniform little bonnets, and their pale faces, looked lovely.

At that stage of my life, I had a great admiration for Republics, though I did not consider them achievable in the era we had reached: I thought of liberty after the manner of the ancients, or liberty as the daughter of the methods of a new-born society; but I knew nothing of liberty as the child of enlightenment and an old civilisation, liberty which the representative republic has shown to be a reality: God grant it my prove durable! It is no longer necessary to plough one’s own small field, to curse the arts and sciences, or to have pointed nails and a dirty beard to be free.

BkVI:Chap7:Sec2

When I arrived in Philadelphia, General Washington was not available; I was obliged to wait a week to see him. I saw him go by in a carriage drawn by prancing horses, driven four-in-hand. Washington, according to my ideas at the time, was of course Cincinnatus; Cincinnatus in a chariot, clashed a little with my Republic of the Roman year 296. Should the dictator Washington be other than a rustic, prodding his oxen with a goad, while grasping the handle of his plough? But when I went to him with my letter of recommendation, I re-discovered the simplicity of the ancient Romans.

A small house, resembling the neighbouring houses, was the palace of the President of the United States: no sentries, not even any footmen. I knocked; a young maidservant opened the door. I asked her if the General was at home; she told me he was. I replied that I had a letter to deliver to him. The maid asked my name, which is difficult to pronounce in English, and which she could not master. Then she said softly: ‘Walk in, sir,’ and led the way along one of those narrow corridors which serve as entrance-halls in English houses: she showed me into a parlour where she asked me to wait for the General.

I was not greatly moved: greatness of soul or fortune do not impress me; I admire the former without being overawed; the latter fills me more with pity than respect: no man’s face will ever disturb me.

After a few minutes, the General entered: tall in stature, with a calm, cool air rather than one of nobility, he looked like his portraits. I handed him my letter in silence; he opened it, going straight to the signature which he read aloud, exclaiming: ‘Colonel Armand!’ This was the name he knew him by, and with which the Marquis de la Rouërie had signed the letter.

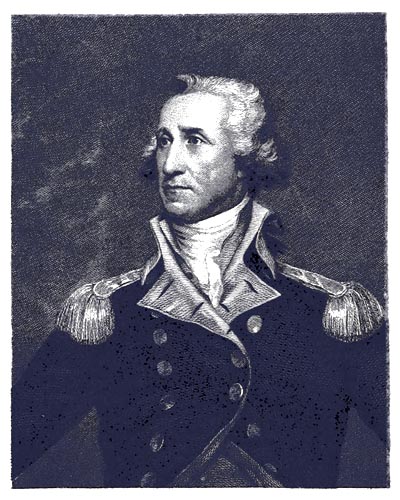

‘George Washington’

American Facts. Notes and Statistics Relating the Government, Resources...of the United States of America - George Palmer Putnam(p12, 1845)

The British Library

We were seated. I explained to him as best I could the motive for my journey. He replied in monosyllables in English and French, and listened to me with a kind of astonishment; I noticed this, and said to him with a degree of vivacity: ‘But it is less difficult to discover the North-West passage than to create a nation as you have done.’ – ‘Well, well, young man!’ he exclaimed, giving me his hand. He invited me to dinner on the following day, and we parted.

I took good care to be there. We were only five or six guests. The conversation turned to the French Revolution. The General showed us a key from the Bastille. These keys, as I have already remarked, were foolish toys which were widely distributed. Three years later, the exporters of locksmiths’ wares could have sent the President of the United States the bolt from the prison of that monarch who gave France and America liberty. If Washington had seen the conquerors of the Bastille in the gutters of Paris, he would have had less respect for his relic. The seriousness and force of the Revolution did not derive from its bloody orgies. At the time of the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, in 1685, the same populace from the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, demolished the Protestant church at Charenton, with the same zeal with which they devastated the church of Saint-Denis in 1793.

I left my host at ten in the evening, and never met him again; he departed the next day, and I continued my travels.

Such was my meeting with the soldier-citizen, the liberator of the world. Washington descended into his grave before even a little fame attached itself to my footsteps; I came before him as the most insignificant of beings; he was in all his glory, I in all my obscurity; my name may not even have lingered a day in his memory: though I am happy that his gaze should have rested on me! I have felt warmed by it for the rest of my life: there is a virtue in the gaze of a great man.

Book VI: Chapter 8: Comparison of Washington and Bonaparte

BkVI:Chap8:Sec1

Bonaparte is not long dead. Since I have come knocking on Washington’s door, the parallel between the founder of the United States and the Emperor of the French naturally springs to mind; even more appropriately, at the moment I trace these lines, Washington himself is no more. Ercilla, fighting and singing in Chile, stopped in the midst of his journey to tell of the death of Dido; I halt at the beginning of my travels, in Pennsylvania, in order to compare Washington and Bonaparte. I would rather not have concerned myself with them until the point where I had met Napoleon; but if I came to the edge of my grave without having reached the year 1814 in my tale, no one would then know anything of what I would have written concerning these two representatives of Providence. I remember Castelnau: like me Ambassador to England, who wrote like me a narrative of his life in London. On the last page of Book VII, he says to his son: ‘I will deal with this event in Book VIII,’ and Book VIII of Castelnau’s Memoirs does not exist: that warns me to take advantage of being alive.

Washington did not belong, as Bonaparte did, to that race of beings that exceed human stature. There was nothing astonishing about him; he was not placed in a vast theatre; he did not deal with the most able generals and the most powerful monarchs of his time: he did not speed from Memphis to Vienna, from Cadiz to Moscow: he acted defensively with a handful of citizens in a land not yet famous, within a narrow circle of domestic hearths. He did not give himself over to battles that recalled the triumphs of Arbela and Pharsalus; he did not overthrown thrones in order to create others from their ruins; he never said to kings at his door:

‘That they were long overdue, and that Attila was bored.’

A degree of silence envelops Washington’s actions; he moved slowly; one might say that he felt charged with future liberty, and that he feared to compromise it. It was not his own destiny that inspired this new species of hero: it was that of his country; he did not allow himself to enjoy what did not belong to him; but from that profound humility what glory emerged! Search the woods where Washington’s sword gleamed: what do you find? Tombs? No; a world! Washington has left the United States behind for a monument on the field of battle.

Bonaparte shared no trait with that serious American: he fought amidst thunder in an old world; he thought about nothing but creating his own fame; he was inspired only by his own fate. He seemed to know that his project would be short, that the torrent which falls from such heights flows swiftly; he hastened to enjoy and abuse his glory, like fleeting youth. Following the example of Homer’s gods, in four paces he reached the ends of the world. He appeared on every shore; he wrote his name hurriedly in the annals of every people; he threw royal crowns to his family and his generals; he hurried through his monuments, his laws, his victories. Leaning over the world, with one hand he deposed kings, with the other he pulled down the giant, Revolution; but, in eliminating anarchy, he stifled liberty, and ended by losing his own on his last field of battle.

Each was rewarded according to his efforts: Washington brings a nation to independence; a justice at peace, he falls asleep beneath his own roof in the midst of his compatriots’ grief and the veneration of nations.

Bonaparte robs a nation of its independence: deposed as emperor, he is sent into exile, where the world’s anxiety still does not think him safely enough imprisoned, guarded by the Ocean. He dies: the news proclaimed on the door of the palace in front of which the conqueror had announced so many funerals, neither detains nor astonishes the passer-by: what have the citizens to mourn?

Washington’s Republic lives on; Bonaparte’s empire is destroyed. Washington and Bonaparte emerged from the womb of democracy: both of them born to liberty, the former remained faithful to her, the latter betrayed her.

Washington acted as the representative of the needs, the ideas, the enlightened men, the opinions of his age; he supported, not thwarted, the stirrings of intellect; he desired only what he had to desire, the very thing to which he had been called: from which derives the coherence and longevity of his work. That man who struck few blows because he kept things in proportion has merged his existence with that of his country: his glory is the heritage of civilisation; his fame has risen like one of those public sanctuaries where a fecund and inexhaustible spring flows.

Bonaparte might have enriched public life equally; he acted on the most intelligent, bravest, most brilliant nation on earth. What a ranking he would have today if he had joined magnanimity to whatever he possessed of the heroic, if, at once Washington and Bonaparte, he had appointed liberty as the sole legatee of his glory!

But that giant never linked his own destiny to that of his contemporaries; his genius belonged to the modern age: his ambition was that of ancient times; he could not see that the miracles of his life were worth more than a coronet, and that such Gothic ornaments suited him ill. At one moment he launched himself at the future, at another he fell back into the past; and whether he stirred or followed the current of his time, with his prodigious force he drove on or held back the waves. Men were in his eyes only a means to power; no identification was established between their happiness and his own: he promised to deliver them, and he enchained them; he isolated himself from them, they distanced themselves from him. The Egyptian Pharaohs sited their funeral pyramids not among flowering meadows, but in the midst of sterile sands; those great tombs stand like eternity in the solitude: Bonaparte built the monument to his fame in their image.

End of Book VI