François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book V: Revolution 1789-1791

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book V: Chapter 1: First political stirrings in Brittany – A glance at the history of the Monarchy

- Book V: Chapter 2: Constitution of the States of Brittany – The meeting of the States

- Book V: Chapter 3: The royal revenues in Brittany – Revenues peculiar to the province – The fouage (feudal tax) – I attend my first political meeting – A Scene

- Book V: Chapter 4: My mother retires to Saint-Malo

- Book V: Chapter 5: Receiving the tonsure - The environs of Saint-Malo

- Book V: Chapter 6: The ghost - Illness

- Book V: Chapter 7: The States of Brittany in 1789 – Insurrection – The death of Saint-Riveul, my friend from college

- Book V: Chapter 8: The year 1789 – Journey from Brittany to Paris – Turmoil along the way – How Paris looked – Dismissal of Monsieur Necker – Versailles – The gaiety of the Royal Family - General insurrection – The taking of the Bastille

- Book V: Chapter 9: The effect on the Court of the taking of the Bastille – The heads of Foulon and Bertier

- Book V: Chapter 10: The recall of Monsieur Necker – The debate of the 4th August 1789 – The Day of the 5th October – The King is brought to Paris

- Book V: Chapter 11: The Constituent Assembly

- Book V: Chapter 12: Mirabeau

- Book V: Chapter 13: The sessions of the National Assembly - Robespierre

- Book V: Chapter 14: Society – How Paris appeared

- Book V: Chapter 15: What I did in the midst of all this chaos – My solitary days – Mademoiselle Monet – With Monsieur de Malesherbes I decide on my plan for a voyage to America – Bonaparte and I, unknown second-lieutenants – The Marquis de La Rouërie – I embark at Saint-Malo – Last thoughts on leaving my native land

Book V: Chapter 1: First political stirrings in Brittany – A glance at the history of the Monarchy

Paris, September 1821. (Revised December 1846).

BkV:Chap1:Sec1

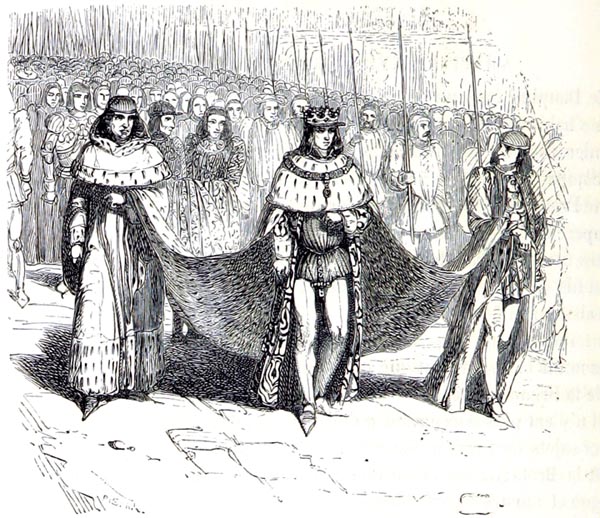

My various residences in Brittany, in the years 1787 and 1788, initiated my political education. The Provincial States presented a model of the States-General: also the specific disturbances that heralded those of the nation broke out in two regions, Brittany and the Dauphiné.

‘Le Duc de Bretagne Allant Ouvrir les États’

La Bretagne Ancienne et Moderne. Illustré - Pitre-Chevalier (p540, 1859)

The British Library

The transformation which had taken place over two centuries came to fulfilment: France having passed from feudal monarchy to the monarchy of the States-General, from the monarchy of the States-General to the monarchy of the parliaments, from the monarchy of the parliaments to absolute monarchy, tended towards representative monarchy, through the struggle between the magistracy and royal authority.

Maupeou’s parliament, the establishment of provincial assemblies, with the vote per head, the first and second assemblies of Notables, the plenary Court, the formation of grand bailiwicks, the civil reintegration of the Protestants, the partial abolition of torture, that of days of unpaid labour, and the equal distribution of tax payments, were successive proofs of the revolution which was taking place. But at that time one could not see the trend of events, each occurrence seemed an isolated accident. In all historical periods there is a driving-spirit. Seeing only one point, one cannot see the rays converging to the focus of all other points; one cannot detect the hidden agent which produces the general life and movement, like water or heat in a machine: that is why, at the start of a revolution so many people think it enough to break a wheel in order to prevent the torrent from flowing or the vapour from exploding.

The eighteenth century, the century of intellectual action, not material action, would not have succeeded in changing the laws so swiftly if it had not come across the right vehicle: the parliaments, and in particular the Paris parliament, became the instruments of a philosophical system. All opinion aborts in powerlessness and frenzy, if it is not vested in an assembly that empowers it, gives it a will, furnishes it with a language and arms. It is, and always will be, through bodies, legal or illegal, that revolutions arrive and will arrive.

The parliaments had reason for revenge: absolute monarchy had snatched from them an authority usurped on behalf of the States-General. Forced registrations, lits de justice (special sessions of the parliament over which the king presided) and imposed exile, in making the magistrates popular, drove them to demand freedoms of which they were not at heart sincere partisans. They called for the States-General, not daring to admit that they desired legislative and political power for themselves: in that way they hastened the resurrection of a body whose inheritance they had already received, which in renewing its existence, immediately limited them to their own speciality, justice. Men almost always damage their own interests when they are moved by wisdom or passion: Louis XVI restored the parliaments which forced him to call the States-General; the States-General, transformed itself into the National Assembly, and then the Convention, destroyed both throne and parliaments, putting to death both the judges and the monarch from whom justice emanated. But Louis XVI and the parliaments acted in that way because they were, without realising it, the means to engender a social revolution.

BkV:Chap1:Sec2

The idea of the States-General then was in everyone’s mind, only one could not see where it would lead. It was a question, for the masses, of making good a deficit that the lowliest banker today would take it upon himself to eliminate. So violent a remedy, applied to so trivial a problem demonstrated that we had entered unknown regions politically. For the year 1786, the only year for which the financial accounts are well-attested, receipts were 412,924,000 livres, expenditure was 593,542,000 livres: the deficit was 180, 618, 000 livres, reduced to 140 millions, by 40 million 610 thousand livres of savings. In that budget, the King’s household was reckoned at the immense sum of 37 million 200 thousand livres: the princes’ debts, the acquisition of various châteaux and the depredations of the Court were the reasons for that excess.

They wished to revive the States-General as they were in 1614. Historians always cite their form at that time, as if, after 1614, no one had ever heard a word of the States-General, nor asked for them to be summoned. Yet, in 1651, the orders of nobility and clergy, meeting in Paris, called for the States-General. A large collection of the acts passed, and speeches made, at that time, still exists. The Paris parliament, all powerful at that time, far from seconding the wishes of the two senior orders, condemned their assembly as illegal; which was correct.

And whilst I am pursuing this, I wish to note another serious matter that has escaped those who, without knowledge of it, have involved and involve themselves in French history. We speak of the three orders, as essential constituents of the States described as general. Well, it often happened that various bailiwicks only nominated deputies from one or two of the orders. In 1614, the bailiwick of Amboise nominated representatives for neither the clergy nor the nobility: the bailiwick of Chateauneuf-en-Thimerais sent no representative of the clergy or the third estate; Le Puy, La Rochelle, Le Lauraguais, Calais, La Haute-Marche, Châtellerault sent no representative of the clergy, nor Montdidier et Roye of the nobility. None the less the States of 1614 were called States-General. Also the ancient chronicles, expressing themselves in the most correct manner, say, in speaking of our national assemblies, the three States, or the notable personages, or the bishops and the barons, as appropriate, and attribute to assemblies so composed the same legislative power. In various provinces, the third estate, though summoned, appointed no delegates, and for a natural but less obvious reason. The third estate had seized the magistracy; it had driven out the men of the sword; it reigned there in an absolute manner, except in various parliaments of the nobility, as judge, advocate, prosecutor, clerk etc.; it made civil and criminal law, and with the aid of parliamentary usurpation, even exercised political power. The fortune, honour, and life of the citizen, was its concern: everyone abided by its judgements, every head bowed beneath its sword of justice. When it enjoyed such boundless power, what need for it to seek a feeble fraction of that power in assemblies where it only appeared on its knees?

The people, transformed into monks, took refuge in the cloister, and governed society through religious opinion; the people transformed into tax-collectors and bankers, took refuge in finance, and governed society through money; the people changed into magistrates, took refuge in tribunals, and governed society through the legal system. The great kingdom of France, aristocratic in its regions or provinces, was collectively democratic, under the leadership of its king, with whom it agreed perfectly, and almost always progressed in harmony. It is that which explains its long existence. There is a new history of France to write concerning all this, or rather the history of France has not yet been written.

All the great questions mentioned above were particularly at issue in the years 1786, 1787 and 1788. The minds of my compatriots found in their natural energy, in the privileges of province, clergy and nobility, in the collision between parliament and the States, abundant inflammatory matter. Monsieur de Calonne, one time steward of Brittany, had furthered division by favouring the cause of the third estate. Monsieur de Montmorin, and Monsieur de Thiard were too weak as commandants to allow the Court party to dominate. The nobility joined forces with the parliament, which itself was noble; now it resisted Monsieur Necker, Monsieur de Calonne, the Archbishop of Sens; now it repressed the popular movement that its opposition had at first encouraged. It assembled, deliberated, protested; the communes and municipalities assembled, deliberated and protested in a contrary manner. The particular matter of the fouage (a feudal tax) by becoming entangled with more general matters increased the feelings of enmity. To understand this, it is necessary to explain the constitution of the Duchy of Brittany.

Book V: Chapter 2: Constitution of the States of Brittany – The meeting of the States

Paris, September 1821. (Revised December 1846).

BkV:Chap2:Sec1

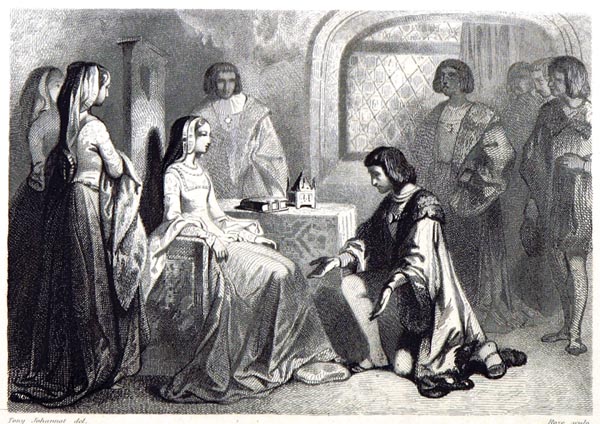

The States of Brittany were more or less varied in form, like all the feudal States of Europe which they resembled. The kings of France acquired the rights of the Dukes of Brittany. The marriage contract of Duchess Anne, of 1491, not only gifted Brittany, as part of her dowry, to the crown of Charles VIII and Louis XII, but it stipulated a transaction which led to the end of a disagreement going back to the time of Charles de Blois and the Comte de Montfort. Brittany claimed that daughters inherited the duchy; France maintained that the succession only passed through the male line; and that when the latter failed, Brittany, like a vast fiefdom, had to return to the crown. Charles VIII and Anne, then Anne and Louis XII, mutually yielded their rights or pretensions. Claude, daughter of Anne and Louis XII, who became the wife of François I, left the Duchy of Brittany to her husband at her death. François I, following the plea by the States assembled at Vannes, united, by public edict at Nantes in 1532, the Duchy of Brittany to the crown of France, guaranteeing the Duchy its freedoms and privileges.

‘Anne de Bretagne et Louis d'Orléans’

La Bretagne Ancienne et Moderne. Illustré - Pitre-Chevalier (p518, 1859)

The British Library

At that time, the States of Brittany met each year; but in 1630 their meeting became biannual. The governor proclaimed the opening of the States. The three orders assembled, according to rank, in a church or in the halls of a monastery. Each order deliberated separately: there were three private gatherings with various storms blowing, which became a combined hurricane when the clergy, nobility and third estate came together. The Court blew on the discord, and in that narrow battlefield as in a greater arena, talent, vanity, and ambition were at play.

The Capuchin friar, Le Pere Grégoire de Rostrenen, in the dedication to his Dictionnaire français-breton, speaks, in this way, to our Lords of the Breton States:

‘If it was not acceptable for a Roman orator to praise the august assembly of the Roman Senate, is it right for me to venture to eulogise your august assembly, which recreates for us so worthily the idea of what the ancient and the new Rome possessed of majesty and respectability?’

Rostrenen shows that Celtic is one of the primitive languages which Gomer, Japhet’s eldest son, brought to Europe, and that the later Bretons, despite their size, are descended from giants. Unfortunately, the Breton children of Gomer, for a long time separated from France, have allowed some of their old titles to perish: their charters, to which they gave too little importance compared with their ties to the common history, too often lack that authenticity on which the decipherers of title-deeds for their part set far too high a price.

The meeting of the Breton States was a time of galas and balls: one dined with Monsieur the Commandant, one dined with Monsieur the President of the Nobility, one dined with Monsieur the President of the Clergy, one dined with Monsieur the Treasurer of the States, one dined with Monsieur the Intendant of the Province, one dined with Monsieur the President of the Parliament: one dined everywhere: and one wined! Sitting at the long refectory tables Du Guesclin ploughmen, Duguay-Trouin sailors could be seen, old guardsman’s steel blades at their sides or little boarding-cutlasses. All the gentlemen attending the States in person resembled nothing more than a Polish Diet, Poland on foot, not on horseback, a Diet of Scythians, not Sarmatians.

BkV:Chap2:Sec2

Unfortunately, they enjoyed themselves too much. The balls continued. Bretons are noted for their dancing and the tunes to which they dance. Madame de Sévigné has described our political junkets among the moors, like those feasts of fairies and sorcerers that take place at night on the heather:

‘Now you shall have,’ she writes, ‘news of our States, and pay the price of being a Breton. Monsieur de Chaulnes arrived on Sunday evening, with all the noise Vitré can manage: on Monday morning he wrote me a letter; I responded to it by going to dine with him. We ate at two tables in the same room; there were four covers to each table; Monsieur occupied one, and Madame the other. The food was excessive, they carried away whole platters of roast meat; and for the pyramids of fruit it was necessary to raise the height of the doorways. Our forefathers never anticipated this sort of thing, since they did not even understand the need to make doorways taller than themselves. After dinner, Messieurs de Locmaria and Coëtlogon danced marvellous passe-pieds and minuets with two Breton ladies, with an air that courtiers could not approach: they demonstrated Bohemian and Bas-Breton steps with charming delicacy and exactness. There is gaming, fine eating, freedom day and night, attracting the whole of society. I had never seen the States before; it’s a very fine thing. I do not think there is a provincial gathering that has as grand an air as this one; it should be the case, at least, since there is not a single person at war or at court; only the little standard-bearer (Monsieur de Sévigné, the son) who may return one day like the others. An infinity of gifts, pensions, repairs to the roads and towns, fifteen or twenty great tables, continual gaming, balls eternally, plays three times a week, a great show: there you have the States. I omitted the three or four casks of wine that have been consumed.’

‘Un Coin de Vitré’

La France Pittoresque. Ouvrage Illustré - Jules Gourdault (p83, 1893)

The British Library

Bretons have found it hard to excuse Madame de Sévigné for her mockery. I am less severe; but I dislike the fact that she says: ‘You speak to me very amusingly of our efforts. We are no longer so broken: one day in eight suffices to maintain justice. It is true that hanging now seems a refreshing change to me.’ That is to take the flippant language of the Court too far: Barrère speaks of the guillotine with the same lightness. In 1793, the drownings at Nantes were spoken of as republican marriages: popular despotism reproduced the facile style of royal despotism.

The Parisian snobs, who accompanied the King’s gentlemen to the States, related that we country squires lined our pockets with tin-plate so as to carry Monsieur the Commandant’s fricasseed chicken home to our wives. They paid dearly for that raillery. A certain Comte de Sabran was left dead in the square not so long ago, in exchange for his unpleasant remarks. This descendant of troubadours and Provençal kings, tall as a Swiss, was killed by a little hare-courser from Morbihan, no higher than a Laplander. This Ker yielded nothing to his adversary in point of genealogy: if Saint Elzéar de Sabran was a close relative of Saint Louis, Saint Corentin, the great-uncle of the noble Ker, was Bishop of Quimper under King Gallon II, three hundred years after Jesus-Christ.

Book V: Chapter 3: The royal revenues in Brittany – Revenues peculiar to the province – The fouage (feudal tax) – I attend my first political meeting – A Scene

BkV:Chap3:Sec1

The royal revenues, in Brittany, were derived from discretionary gifts, varied according to need; the income from the crown estate, which one might put at three to four hundred thousand francs; and the stamp duty etc.

Brittany had revenues peculiar to itself, which required it to accept the charges imposed as follows: the grand and the petit devoir, which affected liquid assets and their transfers, furnished two millions a year; then there were the sums derived from the fouage. There should be scarcely any doubt of the importance of the fouage in our history; it was to the French Revolution what stamp duty was to the revolution in the United States.

Fouage (census pro singulis FOCIS exactus: a tax imposed on every home) was a feudal rent, a kind of tallage, imposed on the common people for every hearth. By gradual increases in the fouage, the province’s debt was paid. In time of war, expenditure amounted to more than seven millions from one session to another, the major source of income. The idea of creating financial capital derived from fouage was conceived and instituted as a rent benefiting the levier of fouage: whereas fouage had actually never been more than a loan. The injustice (though a lawful injustice, in terms of royal custom) was in allowing it to fall only on commoners’ property. The townships never ceased complaining; the nobility, clinging less to their money than to their privileges would not allow discussion of any charge which might make them taxable. Such were the issues, when the fiery Breton States met in the month of December 1788.

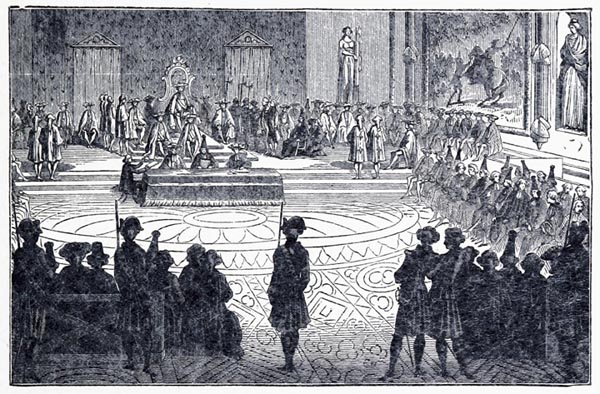

Their minds were agitated then for various reasons: the Assembly of Notables, regional taxation, the corn trade, the impending session of the States-General and the affair of the necklace, the plenary Court and The Marriage of Figaro, the Grand Bailiwicks and Cagliostro and Mesmer, and a thousand other things, serious or futile, were objects of controversy in every family.

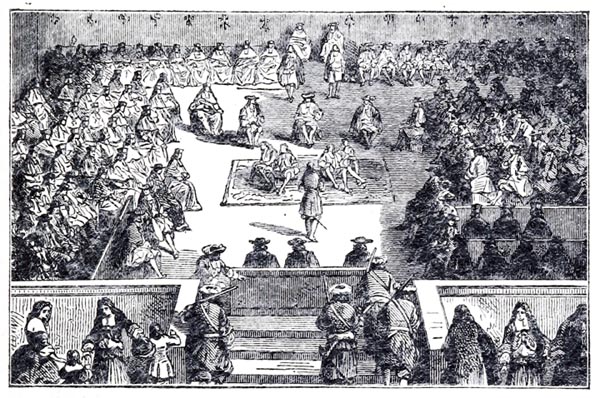

‘Assemblée des Notables’

La Veille de la Révolution - A. Picaud (p197, 1886)

The British Library

The Breton nobility, in its own right, was summoned to Rennes to protest against the establishment of the plenary Court. I went to this gathering: it was the first political meeting I attended. I was amazed and amused by the shouts I heard. They climbed on tables and chairs; they gesticulated, all spoke at once. The Marquis de Trémargat, ‘Peg-Leg’, spoke with the voice of Stentor: ‘Let us all go to the Commandant, Monsieur de Thiard’; and say to him: ‘The Breton nobility is at your door, demanding to speak with you: even the King would not refuse!’ At this stroke of eloquence cheers shook the rafters. He cried again: ‘Even the King would not refuse!’ The shouts and stamping redoubled. We went to see Monsieur the Comte de Thiard, a gentleman of the Court, erotic poet, a gentle and frivolous soul, mortally wearied by our noise; he looked at us as if we were hooting owls, wild boars, savage beasts; he burned with desire to quit our Armorica, and had no wish to refuse us entry into his hotel. Our orator told him what we desired, after which we drew up this declaration: ‘Let us declare those to be vile who would accept a place either in the new administration of justice, or the administration of the States, neither of which have been endorsed by the constitutional law of Brittany.’ Twelve gentlemen were chosen to carry this document to the King: on arrival in Paris they were imprisoned in the Bastille, from which they later emerged as heroes; they were received with laurel branches on their return. We wore coats with large mother-of-pearl buttons bordered with ermine, round which were inscribed in Latin this device: ‘Death before dishonour.’ We triumphed over the Court which all the world triumphed over and we fell with it into the same abyss.

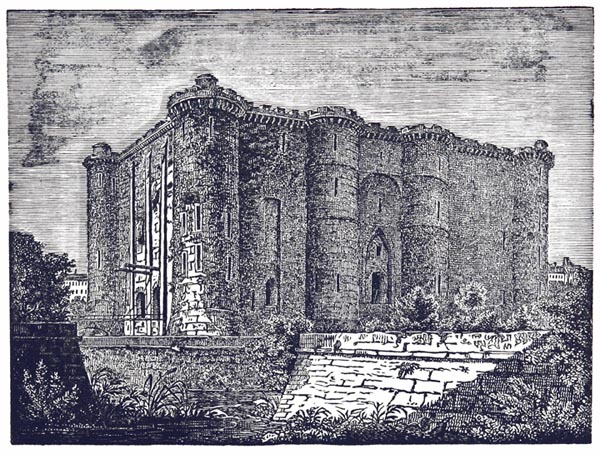

‘La Bastille’

Paris Historique et Monumental Depuis son Origine Jusqu'en 1851 - B. R[enault?] (p201, 1851)

The British Library

Book V: Chapter 4: My mother retires to Saint-Malo

Paris, October 1821.

BkV:Chap4:Sec1

At this time, my brother, pursuing his plans, decided to obtain my admission to the Order of Malta. For this it was necessary for me to receive the tonsure: it could be given by Monsieur Cortois de Pressigny, Bishop of Saint-Malo. So I went to my native city where my good mother had settled; she no longer had her children with her; she spent the days in church, the evenings knitting. Her absent-mindedness was unbelievable: I met her in the street one morning, carrying one of her slippers under her arm, by way of a prayer-book. From time to time old friends would penetrate her retreat, and talk about the good old days. When we were alone, she would improvise beautiful stories for me in verse. In one of these stories the devil carried off a chimney along with a heathen, and the poet wrote:

‘The devil in the avenue

Marched so, to and fro,

That they lost sight of it,

In less than an hour or two.’

‘It seems to me, that the devil took his time,’ I said. But Madame de Chateaubriand proved to me that I had understood nothing: she was delightful, my mother.

She had a long ballad about the True story of a wild duck, in the town of Montfort-la-Cane-lez-Saint-Malo. A certain lord had imprisoned a young girl of great beauty in the Château de Montfort, intending to steal her honour. Through a skylight she saw the church of Saint Nicholas; she prayed to the saint, her eyes full of tears, and was miraculously transported beyond the castle walls; but she fell into the hands of the criminal’s servants, who wished to use her as they supposed their master had. The poor and desperate girl, looking for help on every side, saw only some wild ducks on the château’s lake. Renewing her prayers to Saint Nicholas, she begged him to allow these creatures to testify to her innocence, so that if she should lose her life, and could not accomplish the vows she had made to Saint Nicholas, the birds might fulfil them in their own way, in her name and on her behalf.

The girl died within a year: behold, at the translation of the bones of Saint Nicholas, on the 9th of May, a wild duck accompanied by her little ducklings came to the church of Saint Nicholas. She entered and flapped about in front of the image of the blessed Redeemer, applauding Him by beating her wings; after which she returned to the lake, having left behind one of her little ones as an offering. Some time later, the duckling returned to her without anyone noticing. For two centuries or more afterwards, the duck, always the same duck, returned, on the appointed day, with her brood, to the church of the great Saint-Nicholas at Montfort. The story was written down and printed in 1652; the author justly remarking: ‘that it was an inconsiderable thing in the sight of God, only a feeble wild duck; nevertheless she played her part in order to render homage to his grandeur; Saint Francis’ cicada was even less esteemed, and yet its humming delighted the heart of a Seraphim.’ But Madame de Chateaubriand followed a suspect tradition: in her ballad, the girl imprisoned at Montfort was a princess, who was changed into a duck, to escape her assailant’s violence. I can only remember one couplet of the verses from my mother’s ballad:

‘Duck the beautiful has come,

Duck the beautiful has come,

And flown, through the gate,

Off to a lentil-filled lake.’

Book V: Chapter 5: Receiving the tonsure - The environs of Saint-Malo

Paris, October 1821.

BkV:Chap5:Sec1

As Madame de Chateaubriand was a true saint, she persuaded the Bishop of Saint-Malo to give me the tonsure; he had scruples regarding this: granting the ecclesiastical mark to a soldier and layman seemed to him a profanation that smacked of simony. Monsieur Cortois de Pressigny, today Archbishop of Besançon, and Peer of France, is a good and worthy man. He was young then, a protégé of the Queen, and on the way to fortune, which he achieved later by a better road: that of persecution.

In uniform, sword at my side, I knelt at the prelate’s feet; he cut two or three locks of hair from the crown of my head; this was called the tonsure, of which I received a formal certificate. With this certificate I could call on two hundred thousand livres of private income, as soon as my proofs of nobility had been accepted in Malta: an abuse, no question, of the ecclesiastical order, but a useful thing in the political order of the old constitution. Was it not better for a kind of military benefice to grace the soldier’s sword rather than the mantle of an abbé who would have spent the fat of his priestly revenue in the streets of Paris?

The tonsure, conferred on me for the aforementioned reasons, has led ill-informed biographers to claim that I first entered the Church.

This took place in 1788. I had horses, and rode in the countryside, or galloped beside the waves, my old mournful friends; I would dismount and play with them; all the howling brood of Scylla leapt at my knees for me to caress them: Nunc vada latrantis Scyllae: now Scylla’s howling waves. I have travelled great distances to see Nature’s landscapes; I might have been content with those my native country offered me.

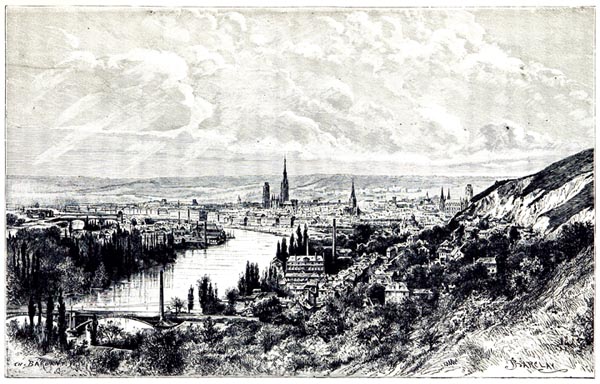

Nothing is more delightful than the twelve to fifteen miles around Saint-Malo. The banks of the Rance, as you trace the river from near its mouth to Dinan, are enough in themselves to merit the traveller’s attention; a constant mixture of rocks and greenery, sandbanks and forests, creeks and hamlets, the ancient manors of feudal Brittany and the modern habitations of commercial Brittany. These latter were constructed in the days when the merchants of Saint-Malo were so wealthy that on festive days they would scatter their piastres, throwing them red hot through the windows into the crowd. These habitations of theirs were very luxurious. Bonaban, the château of Messieurs de Lasaudre, is of marble in part, imported from Genoa, with a magnificence of which we scarcely have an idea in Paris. La Brillantais, Le Beau, Montmarin, La Balue, Le Colombier are or were adorned with orangeries, water-jets and statues. Sometimes the gardens sloped down to a river beneath arcades with lime-tree porticos, through a colonnade of pines, to the end of a lawn; above the tulip-beds the sea revealed its vessels, its calm and its storms.

‘Château de la Rance’

La France Pittoresque. Ouvrage Illustré - Jules Gourdault (p87, 1893)

The British Library

Each peasant, sailor and ploughman is the owner of a little white cottage with a garden: among the vegetables and herbs, currant-bushes, roses, irises and garden marigolds, you find a Cayenne tea-plant, a head of Virginian tobacco, and a Chinese flower, or some such souvenir of another shore and another climate: it is the owner’s chart and itinerary. The coastal tenant-farmers are of fine Norman stock; the women tall, slender, agile, wear grey woollen bodices, short petticoats of calamanco and striped silk and white stockings with coloured clocks. Their brows are shaded by a wide head-dress in dimity or cambric, with flaps that stand up in the form of a cap or float in the manner of a veil. A silver chain hangs in several loops at their left side. Every morning, in spring, these northern daughters, stepping from their boats as though they were once more invading the country, carry baskets of fruit and shells filled with curds to market: when they balance black jars full of milk or flowers on their heads, when the lace-bands of their white wimples set off their blue eyes, pink faces, and blonde hair beaded with dew, the Valkyries of the Edda of whom the youngest is Futurity,or the Canephori of Athens were never as graceful. Is this picture still a faithful likeness? Those women are doubtless no more; they exist only in my memory.

Book V: Chapter 6: The ghost - Illness

Paris, October 1821.

BkV:Chap6:Sec1

I left my mother, and went to visit my elder sisters near Fougères. I stayed a month with Madame de Chateaubourg. Her two country houses, Lascardais and Le Plessis, near Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier, known for its fortress and its battle, were situated in a country of rocks, moors and woods. My sister had Monsieur Livorel as her steward, a former Jesuit, to whom a strange thing happened.

After he was appointed as steward of Lascardais, it chanced that the Comte de Chateaubourg, the father, died: Monsieur Livorel who had not met him was installed as guardian of the castle. The first night he slept there alone, he saw a pale old man, in a dressing gown and night-cap, enter his apartment, carrying a little candle. The apparition approached the hearth, set his candlestick down on the mantelpiece, relit the fire and sat down in his armchair. Monsieur Livorel trembled all over. After two hours of silence, the old man rose, took up his candle, and left the room, closing the door.

Next day, the steward told the farmers of his adventure, who on hearing his description of the lemur affirmed that it was their old master. It did not end there: if Monsieur Livorel glanced behind him in the forest, he saw the phantom; if he had to cross a stile in the fields, the shade was straddling the stile. One day, the persecuted wretch ventured to say: ‘Monsieur de Chateaubourg, leave me alone’; the revenant replied: ‘No.’ Monsieur Livorel, a sober-minded realist, quite lacking in imagination, would retell his story to whoever might wish it, always in the same manner and with the same conviction.

Sometime later in Normandy I was in the company of a brave officer suffering from cerebral fever. We were found lodgings in a farmhouse: an old tapestry, lent by the owner of the place, separated my bed from that of the sick man. Behind the tapestry they bled the patient; to ease his suffering they plunged him in icy baths; he shivered under this torture, his fingernails turned blue, his face was a purple grimace; with teeth clenched and head bared the long beard falling from his pointed chin served to cover his wet, skinny naked chest.

When the illness touched him, he opened an umbrella, thinking to shelter from his tears: if such a method indeed protected against tears a statue would need to be erected in honour of its discoverer.

My only moments of relief were those when I would walk in the village churchyard, built on a little hill. My companions there were the dead, a few birds, and the setting sun. I would dream of society in Paris, my early years, my phantom, and those woods of Combourg which I was so near to in space, so distant from in time; I would return again to my poor wretch: it was the blind leading the blind.

Alas! A blow, a fall, a moral affliction might have robbed Homer, Newton, Bossuet of their genius, and those divine mortals, instead of exciting profound pity, bitter and eternal regrets, might have become objects of derision! Many people I have known and loved happened to have their reason disturbed when with me, as if I carried the seeds of contagion. I can only explain Cervantes’ masterpiece and its cruel cheerfulness, by a sad reflection: in considering the whole of being, in weighing good and evil, one might be tempted to wish for any event that brought forgetfulness, as a means of escaping oneself: a joyful drunkard is a happy creature. Religion aside, ignorance is bliss, to reach death without having suffered life.

I brought back my compatriot completely cured.

Book V: Chapter 7: The States of Brittany in 1789 – Insurrection – The death of Saint-Riveul, my friend from college

Paris, October 1821.

BkV:Chap7:Sec1

Madame Lucille and Madame de Farcy, having returned to Brittany with me, wished to return to Paris; but I was detained by provincial unrest. The States were summoned for the end of December 1788. The commune of Rennes, and afterwards the other communes of Brittany, had made a decree forbidding their deputies from being involved in any matter before the question of fouage had been settled.

The Comte de Boisgelin, who had to preside over the order of nobility hastened to reach Rennes. The gentlemen were summoned by individual letter, and included those who, like me, were still too young to provide an authoritative voice. We might be assailed; it was a matter of counting arms as much as votes: we took up our posts.

Several meetings were held at Monsieur de Boisgelin’s residence before the States opened. All the scenes of confusion at which I had been present recurred. The Chevalier de Guer, the Marquis de Trémargat, my uncle the Comte de Bedée, who was called Bedée the artichoke because of his fatness, in contrast to another Bedée, tall and slender, who was called Bedée the asparagus, broke several chairs while climbing onto them in order to hold forth. The Marquis de Trémargat, the wooden-legged naval officer, created many enemies for his order: one day they were discussing the establishment of a military college where the sons of impoverished nobles would be educated, when a member of the third estate shouted: ‘And what of our sons? What of them?’ – ‘The workhouse,’ Trémargat replied: a comment which, spreading among the crowd, quickly took seed.

In the midst of these meetings I noticed a trait in my character which I have recognised since in politics and military affairs: the hotter my friends and colleagues become, the cooler I become; I would watch them set light to a platform or a cannon with the same indifference: I have never saluted words or bullets.

The result of our deliberations was that the nobility would deal with general matters first, and would not discuss the fouage until after the other questions were addressed; a resolution directly opposed to that of the third estate. The nobles had no great confidence in the clergy, who often deserted them, especially when the Bishop of Rennes presided, a smooth-tongued, measured, individual, who spoke with a slight lisp which was not unattractive, and took good care to nurture his chances at Court. A newspaper, The Sentinel of the People, produced by some hack at Rennes, reached Paris, and fomented hatred.

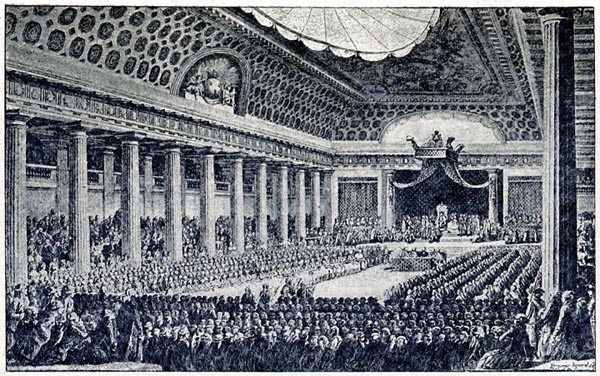

‘Séance des États de Bretagne’

La Veille de la Révolution - A. Picaud (p229, 1886)

The British Library

The States were held in the Jacobin convent, in the Place du Palais. We entered the meeting room in order of arrival: we were no sooner in session than the crowd besieged us. The 25th, 26th, 27th and 28th of January 1789 were wretched days. The Comte de Thiard had few troops; an indecisive leader, lacking in vigour, he wavered and failed to act. The law-school at Rennes, with Moreau at its head, had summoned the young men of Nantes; four hundred of them arrived and the Commandant, despite his exhortations, could not prevent them invading the town. Meetings of various kinds, on the Montmorin Field, and in the cafes, lead to bloody encounters.

Weary of being packed in our room, we decided to burst out, sword in hand; it was rather a fine spectacle. At a signal from our President, we all drew our swords at the same moment, shouting: ‘Long live Brittany!’ and like a garrison without any other recourse, we executed a wild sortie, to pass through the heart of our besiegers. The crowd received us with howls, showers of stones, blows from iron-tipped sticks, and pistol shots. We forced a gap in the massed ranks which closed over us again. Several gentlemen were wounded, dragged along, and torn, covered with bruises and contusions. We managed to disengage with great difficulty, everyone regaining his lodgings.

Duels ensued between the gentlemen and the law students, and their friends from Nantes. One of these duels took place in public on the Place Royale; honours rested with the elder Keralieu, a naval officer, who when attacked fought with amazing energy, to the applause of his young adversaries.

Another gathering formed. The Comte de Montbourcher saw a student named Ulliac in the crowd, to whom he said: ‘Monsieur, this concerns the two of us.’ The crowd made a circle round them; Montbourcher disarmed Ulliac and returned his sword: they embraced and the crowd dispersed.

At least the Breton nobility did not succumb without honour. They refused to send deputies to the States-General, because they were not convoked according to the fundamental laws of the province’s constitution; they flocked in great numbers to join the Army of Princes, to be decimated in the army of Condé, or with Charette in the fighting in the Vendée. Would it have altered the majority in the National Assembly if it had joined that assembly? That is hardly likely: in great social transformations, individual resistance, though honourable in the participants, is powerless against fate. However it is difficult to say what might have been achieved by a man of Mirabeau’s genius, if, with opposing views, he had been met with in the ranks of the Breton nobility.

The young Boishue, and Saint-Riveul, my school-friend, had died before these encounters, on their way to the Chamber of Nobles; the former was defended in vain by his father, who acted as his second.

Reader, I must detain you: witness the first drops of blood flow which the Revolution was obliged to spill. Heaven willed that they should emerge from the veins of a childhood friend. Imagine if I had fallen instead of Saint-Riveul; they would have said of me, altering only the name, what they said of the victim with whom the great immolation began: ‘A gentleman, named Chateaubriand, was killed while on his way to the Chamber of the States.’ Those two words would have replaced my long history. Would Saint-Riveul have played my role on earth? Was he destined for fame or obscurity?

Pass on, now, Reader; cross the river of blood which separates forever the old world, which you are leaving, from the new world on whose threshold you will die.

Book V: Chapter 8: The year 1789 – Journey from Brittany to Paris – Turmoil along the way – How Paris looked – Dismissal of Monsieur Necker – Versailles – The gaiety of the Royal Family - General insurrection – The taking of the Bastille

Paris, November 1821.

BkV:Chap8:Sec1

The year 1789, so notable in our history and in the history of the human race, found me on the moors of my native Brittany; indeed I could not leave the province until quite late, and did not reach Paris until after the sack of the Maison Réveillon, the opening of the States-General, the constitution of the third estate as a National Assembly, the Tennis Court Oath, the Royal Speech of the 23rd June, and the union of the nobles and clergy with the third-estate.

‘Ouverture des États Généraux à Versailles (3 mai 1789)’

Louis XVI. et la Révolution - Maurice Souriau (p179, 1803)

The British Library

There was turmoil along my route: in the villages the peasants were stopping coaches, asking for passports, interrogating travellers. The nearer one approached the capital, the more the unrest grew. Passing through Versailles, I saw troops quartered in the orangery; artillery trains parked in the courtyards; a temporary hall for the National Assembly erected in the Place du Palais, and the deputies coming and going surrounded by sightseers, palace servants and soldiers.

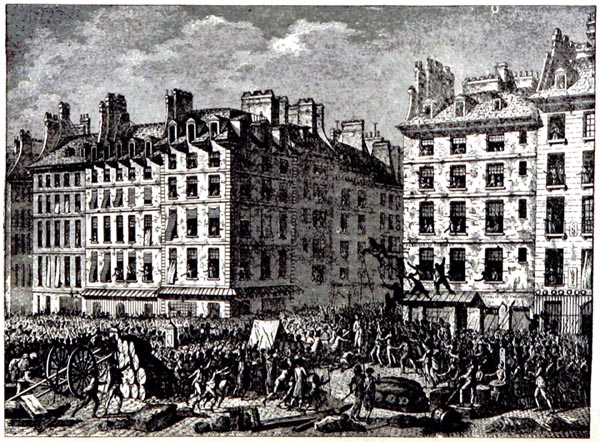

In Paris, the streets were obstructed by crowds standing at the doors of bakers’ shops: passers-by stood debating at street corners; tradesmen came from their shops to hear and tell the news on their doorsteps; at the Palais-Royal agitators congregated: Camille Desmoulins began to emerge from the crowd.

I had scarcely arrived, with Madame de Farcy and Lucile, at a hotel in the Rue de Richelieu, when a riot began: the crowd rushed to the Abbaye to release some French Guards arrested on their officers’ orders. The non-commissioned officers of an artillery regiment quartered at the Invalides joined the people. The army’s defection was beginning.

The Court, now yielding now trying to resist, in a tangle of obstinacy and weakness, bravado and fear, allowed itself to be dictated to by Mirabeau, who demanded the removal of the troops, though it did not agree to remove them: accepting the affront but not eliminating its cause. In Paris a rumour spread that an army was entering by the Montmartre sewer; that dragoons were to force the barriers. Someone suggested stripping the roadways and carrying the paving-stones to the fifth floors to hurl them down on the tyrant’s satellites: everyone set to work. In the midst of this confusion, Monsieur Necker received the order to resign. The new ministry consisted of Messieurs de Breteuil, de la Galaisière, de la Vauguyon, de Laporte, Marshal de Broglie, and Foullon. They replaced Messieurs de Montmorin, de la Luzerne, de Saint-Priest and de Nivernais.

‘Mirabeau Defying the King’

The History of the French Revolution, 1789 to 1795; or a Country Without a God - Henry H. Northrop (p81, 1890)

The British Library

A Breton poet, a new arrival, had asked me to take him to Versailles. There are people who will go and visit gardens and fountains, while empires are being overthrown: scribblers especially have this faculty of remaining abstracted, obsessed, during the greatest of events; their phrase or stanza is everything to them.

I took my Pindar to the gallery of Versailles during mass. The Court was radiant: the dismissal of Monsieur Necker had raised their spirits; they all felt sure of victory: perhaps Sanson and Simon, among the crowd, were spectators of the Royal Family’s delight.

The Queen passed by with her two children; their blond hair seeming to await the presence of crowns: Madame the Duchesse d’Angoulême, aged eleven, drew all eyes with her proud virginity; the flower of the nobility through her blood and her girlish innocence, she seemed like Corneille’s orange flower, in La Guirlande de Julie:

‘I possess the glory of my birth.’

The little Dauphin walked along, protected by his sister, and Monsieur Du Touchet followed his pupil; he noticed me and obligingly pointed me out to the Queen. Casting me a smiling glance, she gave me the same gracious nod she had given me on the day of my presentation. I will never forget that look of hers so soon to be extinguished. Marie-Antoinette, in smiling, shaped her mouth so positively, that the memory of that smile (what an appalling thing!) allowed me to recognise that jaw-bone of that daughter of kings when the head of that unfortunate woman was discovered during the exhumations of 1815.

BkV:Chap8:Sec2

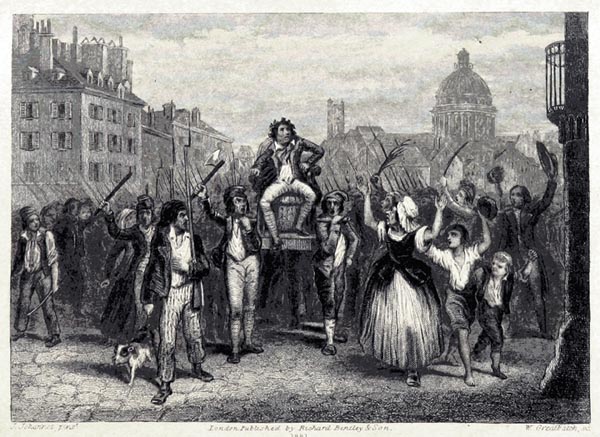

The counter-stroke to the blow struck in Versailles resounded in Paris. On my return I crossed the path of a crowd carrying busts, covered in crape, of Monsieur Necker and Monsieur the Duc d’Orléans. They shouted: ‘Long live Necker! Long live the Duc d’Orléans!’ and among those shouts could be heard one that was bolder and more unexpected: ‘Long live Louis XVII!’ Long live that child whose name would have been left out of his family’s funerary inscription, if I had not recalled it to the memory of the Chamber of Peers! If Louis XVI had abdicated, and Louis XVII been placed on the throne, with Monsieur the Duc d’Orleans declared as Regent, what would have happened?

In the Place Louis XV, the Prince de Lambesc, at the head of the Royal-Allemand Regiment, drove the crowd back into the Tuileries gardens, and wounded an old man: suddenly the tocsin sounded. The sword-cutler’s shops were forced, and thirty thousand muskets taken from the Invalides. They armed themselves with pikes, staves, pitchforks, sabres and pistols; Saint-Lazare was sacked and the city barriers burnt down. The electors of Paris took over the government of the capital, and in a night sixty thousand citizens were organised, armed, and equipped as National Guards.

‘The People Gathering Arms at Night, Paris July 13 1789’

The History of the French Revolution, 1789 to 1795; or a Country Without a God - Henry H. Northrop (p86, 1890)

The British Library

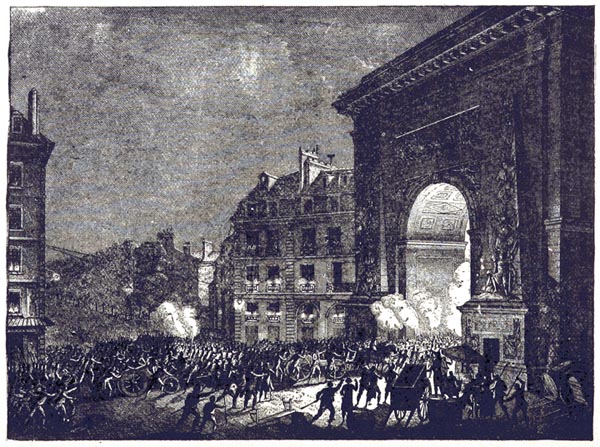

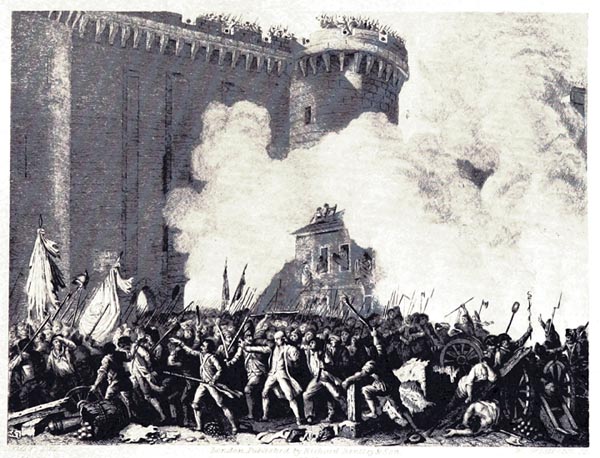

On the 14th of July the Bastille was taken. I was present, as a spectator at this attack on a few pensioners and a timid governor: if the gates had been kept closed, the crowd could never have entered the fortress. I saw two or three cannon shots fired, not by the pensioners, but by the French Guards who had climbed up to the towers. De Launay, the Governor, was dragged from his hiding place, and after suffering a thousand outrages was killed on the steps of the Hôtel de Ville; Flesselles, the provost of the merchants of Paris, had his brains blown out: this is the spectacle that heartless admirers found so admirable. In the midst of these murders, they indulged in wild orgies, as in the disturbances in Rome under Otho and Vitellius. Happily drunk, the ‘conquerors of the Bastille’, declared as such in the taverns, were driven about in carriages; prostitutes and sans-culottes, beginning their reign, escorted them. Passers-by took off their hats, with a respect born of fear, in front of these heroes, some of whom died of fatigue in the midst of their triumph. The keys of the Bastille multiplied; they were sent to all the important fools in the four corners of the world. How many times I have missed making my fortune! If, as a spectator, I had inscribed my name on the list of conquerors, I would have a pension today.

‘Attack of the Bastille and Murder of de Launay’

The History of the French Revolution. Translated by F. Shoberl, Vol 01 - Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p10, 1881)

The British Library

Experts hastened to conduct a post-mortem of the Bastille. Temporary cafes were set up in tents; people crowded them, as at the Saint-Germain fair or Longchamps; files of carriages drove by or stopped at the foot of the turrets, the stones of which were being hurled down among clouds of dust. Elegantly dressed women and fashionable young men, standing on various levels of the Gothic ruins, mingled with the half-naked workers demolishing the walls, to the acclamation of the crowd. The most famous orators could be seen at this gathering-place, the best-known writers, the most celebrated painters, the most renowned actors and actresses, the dancers most in vogue, the most illustrious foreigners, the grandees of the Court and the ambassadors of Europe: the old France came here to meet its end, the new its beginning.

Every event, however wretched or odious it may be in itself, cannot be treated lightly if it occurs in serious circumstances and ushers in an era: what should have been seen in the taking of the Bastille (and what is still not seen) is not one violent act in the emancipation of a people, but the emancipation that resulted from that act.

What was admired, the incident, should have been condemned, and people should no longer have sought in it the final destiny of a people, the change of manners, ideas, political power, renewal of the human species, whose era the taking of the Bastille opened, like a blood-stained Jubilee. Savage anger created ruins, and beneath that anger was hidden the intelligence which built among those ruins the foundations of a new building.

But the nation which erred concerning the importance of the material event did not err concerning the importance of the moral fact: the Bastille was in its eyes a monument to its servitude; it seemed to it to have been erected at the gate of Paris, facing the sixteen pillars of Montfaucon’s gibbet, like a scaffold for its liberties (After fifty-two years they have built fifteen Bastilles to suppress that liberty in whose name they destroyed the first Bastille: Note: Paris, 1841). In razing to the ground a State prison, the people thought to shatter the military yoke, and took on the tacit commitment to replace the army it dismissed: we know what wonders are born when a people become soldiers.

Book V: Chapter 9: The effect on the Court of the taking of the Bastille – The heads of Foulon and Bertier

Paris, November 1821.

BkV:Chap9:Sec1

Woken by the sound of the Bastille’s fall as at the noise presaging the fall of a throne, Versailles passed from disdain to despondency. The King hastens to the National Assembly, gives a speech from the President’s seat, announces an order to the troops to withdraw, and returns to his palace to the echo of cheers; a useless spectacle! Neither party believed they had converted the other: neither liberty which capitulates, nor power which humbles itself, obtains a jot of mercy from its enemies.

Eighty deputies left Versailles, to proclaim peace in the capital: festivities ensued. Monsieur Bailly was named as Mayor of Paris, Monsieur de Lafayette, commander of the National Guard: I never knew the former, a poor but respectable scientist, except through his misfortunes. Revolutions produce men in all their phases; some follow those revolutions through to the end, others begin them, but do not complete them.

Everyone dispersed; the courtiers left for Basle, Lausanne, Luxembourg and Brussels. Madame de Polignac, fleeing, met Monsieur Necker returning. The Comte d’Artois and his sons, and the three Condés, emigrated; they took with them the high clergy and a section of the nobility. The officers, threatened by their rebellious soldiers, yielded to the torrent that carried them away. Louis XVI alone remained to face the nation with his two children and their female attendants, the Queen, Mesdames Adélaïde and Victoire, and Madame Élisabeth. Monsieur, who remained until the flight to Varennes was little help to his brother: though in assenting to the franchise in the Assembly of Notables he had helped decide the course of the Revolution, the Revolution distrusted him; he, Monsieur, had little liking for the King, did not understand the Queen, and was not liked by them.

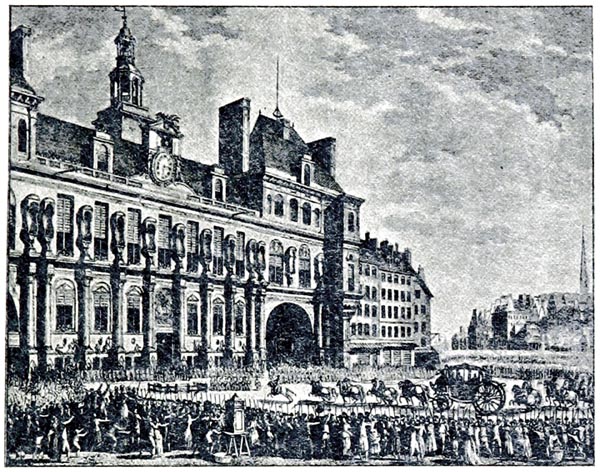

Louis XVI came to the Hôtel de Ville on the 17th: a hundred thousand men, armed like the monks of the League, received him. He was harangued by Messieurs Bailly, Moreau de Saint-Méry, and Lally-Tolendal who all wept: the latter has remained prone to tears. The King was moved in turn; he fixed an enormous tricolour cockade on his hat; and was declared there and then to be a good man, Father of the French, King of a free people, which people was preparing, by virtue of its liberty, to cut off the head of that good man, its father and king.

‘Le Roi Arrivant a l'Hôtel de Ville (17 juillet 1789)’

Louis XVI. et la Révolution - Maurice Souriau (45, 1803)

The British Library

A few days after this reconciliation, I was at the window of my hotel with my sisters and some Breton friends; we heard shouts of: ‘Lock the doors! Lock the doors!’ A ragged crowd appeared at one end of the street; two standards, difficult to see clearly at that distance, rose from their midst. As they came nearer we could make out two dishevelled, disfigured heads, which Marat’s heralds were carrying, each on the tip of a pike: they were the heads of Messieurs Foullon and Bertier. Everyone drew back from the windows; I remained. The assassins stopped in front of me, stretching their pikes towards me while singing, dancing about, jumping up in order to thrust the pale effigies in my face. An eye in one of those heads had leapt from its socket, and hung down on the unrecognisable face of the dead; the pike stuck out of the open mouth, the teeth biting on metal: ‘Brigands!’ I shouted, unable to contain the indignation I felt, ‘Is this how you understand liberty?’ If I had possessed a gun I would have shot at those wretches as one shoots at wolves. They howled, redoubling their blows on the main door in the hope of breaking in, and adding my head to those of their victims. My sisters felt faint; the cowards in the hotel heaped reproaches on me. The murderers, who were being pursued, had no time to invade the building, and made off. Those heads, and others which I encountered soon after, altered my political tendencies; I was horrified by those cannibal feasts, and the idea of leaving France for some distant country took root in my mind.

‘The Terrible Assassination of Foulon, Paris July 1789’

The History of the French Revolution, 1789 to 1795; or a Country Without a God - Henry H. Northrop (p129, 1890)

The British Library

‘The Triumph of Marat’

The History of the French Revolution. Translated by F. Shoberl, Vol 01 - Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p354, 1881)

The British Library

Book V: Chapter 10: The recall of Monsieur Necker– The debate of the 4th August 1789 – The Day of the 5th October – The King is brought to Paris

Paris, November 1821.

BkV:Chap10:Sec1

Recalled to power on the 25th July, inaugurated, welcomed with celebrations, Monsieur Necker, the third successor to Turgot after Calonne and Taboureau, was soon overtaken by events, and fell from popularity. It is one of the oddities of the time that so weighty a personality had been raised to ministerial office through the machinations of a man as mediocre and lightweight as the Marquis de Pezay. The Royal Accounts which in France replaced the system of loans with that of taxation, stirred people’s ideas; women discussed income and expenditure; for the first time one saw, or thought one saw something in the working of numbers. These calculations, painted in clear colours à la Thomas, first established the reputation of the Director-General of Finance. A skilful manager of cash, but an economist devoid of ideas; a writer noble but bombastic; an honest man but without great virtue, the banker was one of those old actors who after introducing the play to the public from the forestage vanish as the curtain rises. Monsieur Necker was the father of Madame de Staël; his vanity would scarcely have allowed him to consider that his true claim on the memory of posterity would be his daughter’s fame.

‘Monsieur Necker, Engraved by E.Thomas from the Design by H. Rousseau’

Album du Centenaire, Grands Hommes et Grands Faits de la Révolution Française (1789-1804) - Augustin Challamel, Desire Lacroix (1889)

Wikimedia Commons

The monarchy was destroyed, as the Bastille had been, in the speech in the National Assembly on the evening of the 4th August. Those who, through hatred of the past, cry out against nobility these days, forget that it was a member of that nobility, the Vicomte de Noailles, supported by the Duc d’Aiguillon and by Mathieu de Montmorency, who toppled the edifice, the subject of revolutionary prejudice. On a motion initiated by the latter aristocratic deputy, feudal rights, the rights of the chase, of dovecotes and fishponds, the tithes on crops, the privileges of the orders, towns and provinces, personal servitude, manorial injustice, veniality of office, were abolished. The greatest blows struck at the old constitution of the State were inflicted by noblemen. The aristocracy began the Revolution, the masses completed it: as the France of old owed its glory to the French nobility, the new France owed it its liberty, if liberty exists in France.

The soldiers camped on the outskirts of Paris had been dispersed, and by one of those perverse pieces of advice that muddled the King’s will, the Flanders Regiment was summoned to Versailles. The Lifeguards gave a dinner for the officers of that regiment; heads grew overheated; the Queen appeared at the banquet with the Dauphin; toasts were drunk to the Royal Family; the King appeared in turn; the military band played the moving and popular air: Ô Richard, ô mon roi! The news of this had hardly reached Paris before hostile views gripped the city; it was claimed that Louis was refusing to sanction the declaration of rights, and would flee to Metz with the Comte d’Estaing; Marat spread the rumour: he was already writing L’ami du peuple.

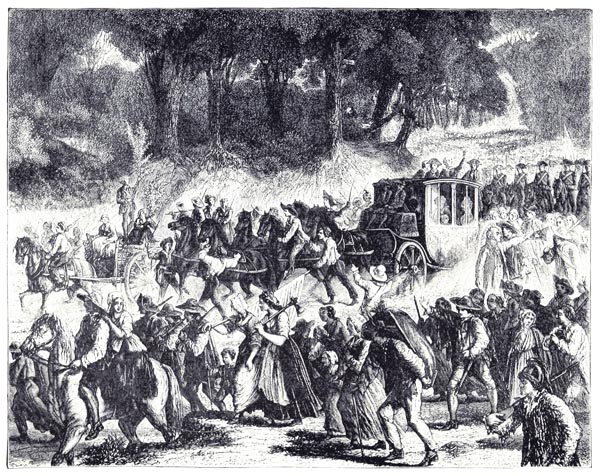

The 5th of October arrived. I did not witness the events of that day. Accounts of it reached the capital early on the 6th. We were told, at the same moment, to expect a visit from the King. Timid in the salons, I was bold in public: I felt I had been born for solitude or the forum. I hurried to the Champs-Elysées: first canon appeared, with harpies, thieves and prostitutes astride them, making the most obscene remarks and the foulest gestures. Then in the midst of a horde of people of every age and sex, the Lifeguards marched by, having exchanged their hats, swords and bandoliers with the National Guards: each of their horses carried two or three fishwives, dirty, drunk and dishevelled bacchantes. Next came the deputation from the National Assembly; followed by the Royal carriages: they rolled along in the dusty shade of a forest of pikes and bayonets. Tattered rag-pickers, and butchers, blood-stained aprons round their thighs, naked blades at their belts, shirt-sleeves rolled, clung to the carriage-doors: other dark satyrs had climbed on the roof; yet more hung on to the footboards or perched on the box. They fired muskets and pistols, shouting: ‘Here come the baker, the baker’s wife and the little baker’s boy!’ Before the descendant of Saint-Louis, as an oriflamme, Swiss halberds held high the heads of two Lifeguards, powdered and curled by some Sèvres wigmaker.

‘L'Arrivée de la Famille Royale à Paris’

Paris à Travers les Siècles. Histoire Nationale de Paris et des Parisiens Depuis la Fondation de Lutèce Jusqu'à Nos Jours, Vol 02 - Gourdon de Genouillac, Nicolas Jules Henri (p831, 1879)

The British Library

Bailly, the astronomer, told Louis XVI, in the Hôtel de Ville, that the people, humane, respectful and loyal had conquered its king, and the King on his side, greatly touched and greatly pleased, declared that he had come to Paris of his own free will: unworthy lies born of violence and fear which at that time dishonoured everyone and every party. Louis XVI was not insincere: he was weak; weakness is not insincerity, but it takes its place and fulfils its functions; the respect which the virtue and misfortune of the saintly, martyred King must inspire renders all human judgement well-nigh sacrilegious.

Book V: Chapter 11: The Constituent Assembly

BkV:Chap11:Sec1

The deputies left Versailles and held their first session on the 19th October in the great hall of the Archdiocese. On the 9th November, they transferred to the riding-school, the Manège, near the Tuileries. The rest of 1789 witnessed decrees which despoiled the clergy, dismantled the old magistracy and created assignats; the decree of the Paris commune to set up the first Committee of Investigation; and the judges’ mandate to prosecute the Marquis de Favras.

The Constituent Assembly, despite the things it can be reproached with, nonetheless remains the most illustrious popular gathering that has ever appeared among nations, as much for the importance of its transactions, as for the magnitude of their results. There was no political question so profound that it failed to touch on it and resolve it appropriately. What would it have achieved, if it had held to the lists of grievances of the States-General and not attempted to deviate from them! All that human experience and intelligence had conceived, discovered and elaborated on for three centuries was in those lists. The various abuses of the old monarchy are indicated there, and remedies proposed; every type of freedom is demanded, for industry, manufacturing, commerce, roads, the army, tax, finance, schools, public education, etc. We have crossed abysses of crime, over heaps of glorious dead, to no purpose; The Republic and the Empire have achieved nothing: the Empire has only directed the brute force of arms that the Republic set in motion; it has left us centralisation, energetic administration which I consider evils, but which alone perhaps could replace local administration once it had been destroyed and heads were full of ignorance and anarchy. As it stands we have not advanced one step since the Constituent Assembly: its efforts were like those of Hippocrates, the great physician of antiquity which, at the same time, delineated and pushed back the boundaries of science. Let me speak about a few members of that Assembly, and start with Mirabeau who summed up and dominated all the others.

Book V: Chapter 12: Mirabeau

Paris, November 1821.

BkV:Chap12:Sec1

Involved by the danger and disorder of his life in great events, and living among hardened criminals, brigands and adventurers, Mirabeau, tribune of the aristocracy, deputy for democracy, owed something to Gracchus, and Don Juan, Catiline and Guzman d’Alfarache, Cardinal de Richelieu and Cardinal de Retz, to the Regency roué and the Revolutionary savage: he possessed more than enough of Mirabeau, an exiled Florentine family that retained something of those fortified palaces and noble dissidents celebrated by Dante; a naturalised French family, in which the republican spirit of the Italian Middle Ages and the feudal spirit of our own Middle Ages were united in a succession of extraordinary men.

‘Portrait of Mirabeau’

François-Séraphin Delpech (French, 1778 - 1825)

Yale University Art Gallery

Mirabeau’s ugliness, overlaying the background of his race’s particular beauty, produced a powerful figure from the Last Judgement by Michelangelo, a compatriot of the Arrighetti. The furrows ploughed in the orator’s face by smallpox had more the look of burn-scars. Nature seemed to have moulded his head for empire or the gibbet, sculpted his arms to embrace a nation or capture a woman. When, gazing at the crowd, he shook his mane, it quietened; when he lifted his paw and showed his claws, the mob ran away swiftly. In the midst of the appalling disorder of a session, I have seen him at the rostrum, ugly, sombre, and motionless: he recalled Milton’s chaos, impassive, and formless at the heart of confusion.

Mirabeau inherited something from his father and uncle, who, like Saint-Simon, wrote immortal pages haphazardly. His speeches for the rostrum were prepared for him: he took from them whatever his spirit could amalgamate with his true substance. If he adopted them in their entirety, he chopped them about mercilessly: it was obvious they were not written by him, from those words which he added at hazard, and which revealed the man. He drew energy from his vices; those vices were not born of a cool temperament, they concerned passions, deep, fiery, and stormy. Cynicism in manners, brought back to society, by annihilating the moral sense, a tribe of barbarians: these barbarians of civilisation, ready to destroy like the Goths, lacked the power to create anything, as those men had: the latter were the giant offspring of virgin Nature; the former the monstrous abortions of Nature depraved.

BkV:Chap12:Sec2

I met Mirabeau twice at a banquet, once at the house of Voltaire’s niece, the Marquise de Villette, once more at the Palais-Royal, with opposition deputies to whom Chapelier had introduced me: Chapelier went to the scaffold, in the same tumbrel as my brother and Monsieur de Malesherbes.

Mirabeau talked a great deal, and especially about himself. This lion’s offspring, himself a lion with the head of a chimera, this man so positive in action, was full of romance, full of poetry, full of enthusiasm for imagination and language; one recognised in him the lover of Sophie, exalted in feeling and capable of sacrifice. ‘I found her,’ he said, ‘that adorable woman; I knew what her soul was, that soul formed in Nature’s hands in a moment of splendour.’

Mirabeau enchanted me with love stories, with longings for seclusion from which he fashioned arid discussions. He also interested me in another way: like me, he had been treated severely by his father, who had maintained, like mine, the inflexible tradition of absolute paternal authority. The famous guest reached out to the political newcomer, and revealed almost nothing of the politics within; though it was that which occupied his thoughts; but he did let fall a few words of sovereign disdain for those men who proclaimed themselves superior because of the indifference they showed towards tragedies and crime. Mirabeau was born generous, appreciative of friendship, quick to pardon offence. Despite his immorality, he could not betray his conscience; he was only corrupt in private matters, his firm and upright spirit refused to make murder a subject for sublime intellect; he had no admiration for abattoirs and charnel-houses.

However, Mirabeau was not lacking in pride; he boasted outrageously; though he was established as a draper in order to be an elected member of the third estate (the nobility had made the honourable mistake of rejecting him) he was obsessed with his birth: a wild bird, whose nest was made between four turrets, as his father said. He never forgot that he had appeared at Court, ridden in a carriage and hunted with the King. He demanded to be called Count; he stuck to his guns and clothed his people in livery when everyone had stopped doing so. He referred at the slightest opportunity and most inopportune moments to his ancestor, Admiral Coligny. The Moniteur having referred to him as Riquet: ‘Do you realise,’ he said angrily to a journalist, ‘that with your Riquet, you have bemused Europe for three days?’ He repeated this impudent and well-known pleasantry: ‘In any other family, my brother the Vicomte would be the intelligent man and the unruly subject; in my family, he is the fool and the philanthropist. ‘ Biographers attribute this witticism to the Vicomte himself, comparing himself with humility to the other members of his family.

BkV:Chap12:Sec3

Mirabeau’s deepest sentiments were royalist; he pronounced these fine words: ‘I would like to cure the French of superstition concerning the monarchy and substitute worship.’ In a letter, destined for Louis XVI’s eyes, he wrote: ‘I would not wish to have worked to create only a vast destruction.’ That however was his fate: Heaven, to punish us for misusing our talents, makes us repent of our achievements.

Mirabeau moved public opinion by employing two levers: on the one hand, he placed his point of leverage among the mob of which he was appointed the defender while scorning it; on the other, though a traitor to his order, he maintained sympathy for affinities of caste, and common interest. Such a thing would be impossible for a plebeian champion of the privileged classes; he would be abandoned by his own party without winning over the aristocracy, by nature ungrateful and un-winnable, when one is not born within its ranks. Besides, the aristocracy cannot just create a noble, since nobility is a child of time.

Mirabeau created a school. In liberating moral ties, they thought it transformed them into statesmen. These imitations only produced perverted little men: such as pride themselves on being corrupt thieves, and are merely debauched rogues; such as think themselves lecherous, and are merely vile; such as boast of being criminals, and are merely base.

Too soon for his own good, too late for its good, Mirabeau sold himself to the Court, and the Court completed the purchase. He put his reputation at risk for a pension and an ambassadorship. Cromwell was on the point of bartering his future for a title and the Order of the Garter. Despite his pride, Mirabeau did not value himself highly. Now that an abundance of money and positions has raised the price of conscience, there is not a promotion that does not cost hundreds of thousands of francs and the highest honours the State can offer. The grave freed Mirabeau from his commitments, and rescued him from dangers he would probably not have overcome: his life had shown his weakness for good; his death left him in possession of his power to do evil.

On our departure, after dinner, there was talk of Mirabeau’s enemies; I found myself next to him and had not said a word. He looked me in the face with his proud stare, of vice and genius, and placing his hand on my shoulder, said: ‘They never forgive me for my superiority!’ I can still feel the impression of that hand, as if Satan had touched me with his fiery claw.

As Mirabeau fixed his gaze on the silent young man, had he any presentiment of my possibilities? Did he think he might one day appear in my memoirs? I was destined to become the historian of important men: they have paraded before me, without my needing to be hung on their coat as a trophy to be dragged along with them towards posterity.

Mirabeau has already undergone the metamorphosis that occurs to those of whom memory remains; transported from the Pantheon to the gutter, and transported from the gutter to the Pantheon again, he was raised by the great heights of that age which serve him today as a pedestal. One no longer sees the real Mirabeau, only the idealised Mirabeau such as the artists created, to render him a symbol, or mythological figure, of the age he represents: thus he became both falser and truer. Among so many reputations, actors, events, ruins, only three men stand out, each attached to each of the three great revolutionary phases, Mirabeau for the aristocracy, Robespierre for democracy, Bonaparte for despotism; the monarchy has no representative: France has paid too dearly for those three celebrated men not to admit to their quality.

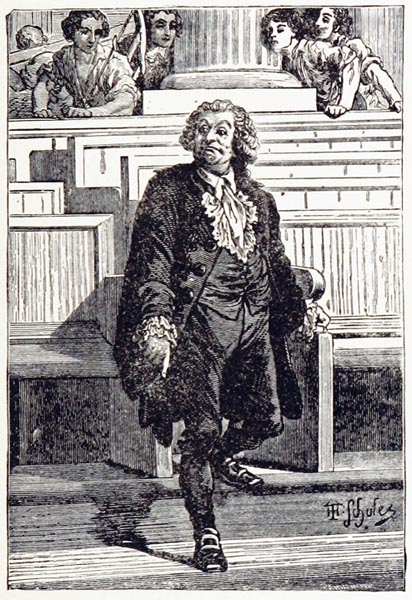

Book V: Chapter 13: The sessions of the National Assembly - Robespierre

Paris, December 1821.

BkV:Chap13:Sec1

The sessions of the National Assembly offered an interest that the sessions of our own Chambers are far from approaching. One had to rise early to secure a place in the crowded galleries. Deputies arrived eating, talking, gesturing; they grouped themselves in various parts of the room, according to their opinions. The order of the day was read; after that the agreed subject was discussed, or an extraordinary motion. It was not a question of insipid points of law; the order of the day rarely omitted some scheme of destruction. They spoke for and against; everybody improvised as best he could. Debates grew stormy; the galleries joined in the discussion, applauding and cheering, hissing and booing the speakers. The president rang his bell; the deputies shouted from one bench to another. Mirabeau the Younger seized his opponent by the collar; Mirabeau the Elder cried: ‘Silence, the thirty votes!’ One day, I was seated behind the royalist opposition; a noble from the Dauphiné in front of me, a swarthy little man, leapt on to his seat in fury, and called to his friends: ‘Let us fall, sword in hand, on those rascals there.’ He pointed to the majority side. The market women, knitting away in the galleries, heard him, rose from their seats, and shouted together, stockings in hand, foaming at the mouth: ‘To the lamp-posts, with them!’ The Vicomte de Mirabeau, Lautrec and a few other young nobles wanted to take the galleries by storm.

Soon this fracas was drowned out by another: petitioners, armed with pikes, appeared at the bar: ‘People are dying of hunger,’ they said, ‘it is time to act against the aristocrats and to rise to the level of events.’ The president assured these citizens of his respect: ‘We have our eye on the traitors,’ he replied, ‘and the Assembly will mete out justice.’ At this, fresh tumult: the deputies of the Right shouted that we were heading for anarchy; the deputies of the Left replied that the people was free to express its will, that it had the right to complain of the supporters of despotism, sitting in the midst of the nation’s representatives: they spoke thus of their colleagues to that sovereign people, which waited for them under the street lamps.

The evening sessions were more scandalous than the morning ones: people speak better and more boldly by candlelight. The hall of the Manège was then a veritable theatre, where one of the world’s greatest dramas was played out. The leading characters still belonged to the old order of things; their terrifying understudies, hidden behind them, said little or nothing. At the end of one violent discussion, I saw a common-looking deputy mount the rostrum, with a grey impassive face, neatly dressed hair, decently dressed like the steward of a good house, or the notary of a village careful of his appearance. He gave a long and tedious report; nobody listened; I asked his name: it was Robespierre. The men in shoes were ready to leave the salons, and already the clogs were kicking at the door.

‘Robespierre’

The History of the French Revolution. Translated by F. Shoberl, Vol 01 - Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p578, 1881)

The British Library

Book V: Chapter 14: Society – How Paris appeared

Paris, December 1821.

BkV:Chap14:Sec1

When, before the Revolution, I had read the history of public disturbances in various nations, I could not understand how one could survive in such times; I was astonished that Montaigne could write so cheerfully in a château he could not walk round without risking capture by bands of Leaguers or Protestants.

The Revolution allowed me to understand the possibility of such an existence. Moments of crisis produce an intensification of life in men. In a society which is dissolving and reforming itself, the struggle of two geniuses, the clash between past and future, the mingling of old ways and new, creates a transitory fusion which leaves not a moment for boredom. The passions and characters set free reveal themselves with an energy that they do not possess in a well-ordered city. Breaches of the law, emancipation from duties, customs and proprieties, even the danger, add to the interest in such disorder. The human race in holiday mood parades through the streets, free of its masters, returned for the moment to a state of nature, and does not start to feel the need for social restraint until it begins to bear the yoke of the new tyrants whom licence breeds.

I can depict the society of 1789 and 1790 in no better a way than by comparing it with the architecture of the age of Louis XII and François I, when the Greek orders were combined with Gothic style, or rather by likening it to the collection of ruins and tombs of all eras, piled up in the cloisters of the Petits-Augustins, after the Terror: only the debris I speak of was alive and ceaselessly changing. There were literary gatherings, political meetings, and public entertainments in every corner of Paris; future celebrities wandered amongst the crowd unrecognised, like the souls on the banks of Lethe before enjoying the light. I saw Marshal Gouvion-Saint-Cyr act at the Marais theatre, in Beaumarchais’s La Mère coupable. One passed from the Club des Feuillants to the Club des Jacobins, from balls and gambling houses to the meetings in the Palais-Royal, from the gallery of the National Assembly to the gallery of the open air. In the streets public deputations, cavalry pickets, and infantry patrols went to and fro. Next to a man in a French coat, with powdered hair, sword by his side, hat under his arm, in pumps and silk stockings, walked a man with cropped un-powdered hair, in an English dress-coat with an American cravat. In the theatres the actors gave the latest news; the pit sang patriotic ditties. Topical plays drew full-houses: if a priest appeared on stage the audience would shout: ‘Calotin: Holy Joe!’ and the priest would reply: ‘Gentlemen, long live the Nation!’ They flocked to hear Mandini, his wife, Viganoni and Rovedino sing at the Opera-Buffa, after hearing the strains of the Ça ira; they went to admire Madame Dugazon, Madame Saint-Aubin, Carline, little Mademoiselle Olivier, Mademoiselle Contat, Molé, Fleury, and the new talent Talma, after seeing Favras hanged.

The walks on the Boulevard du Temple and the Boulevard des Italiens, known as Coblentz, and the paths in the Tuileries Gardens were crowded with well-dressed women: three young daughters of Grétry shone there, pink and white like their dresses: all three died soon after. ‘She fell asleep for ever’, Grétry said, speaking of his eldest daughter, ‘sitting on my lap, as beautiful as when she was alive.’ A host of carriages ploughed over the muddy crossroads where the sans-culottes splashed about, and the lovely Madame de Buffon could be seen, sitting alone in the Duc d’Orléans’ phaeton, waiting at the door of some club.