François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book IV: Regiment, Court, Paris 1786-1789

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book IV: Chapter 1: Berlin – Potsdam – Frederick

- Book IV: Chapter 2: My Brother – My Cousin Moreau – My sister the Comtesse de Farcy

- Book IV: Chapter 3: Julie in society – Dinner – Pommereul – Madame de Chastenay

- Book IV: Chapter 4: Cambrai – The Navarre Regiment – La Martinière

- Book IV: Chapter 5: My father’s death

- Book IV: Chapter 6: Regrets – Would my father have appreciated me?

- Book IV: Chapter 7: Return to Brittany – A stay with my eldest sister – My brother summons me to Paris

- Book IV: Chapter 8: My solitary life in Paris

- Book IV: Chapter 9: Presentation at Versailles – Hunting with the King

- Book IV: Chapter 10: Trip to Brittany – Garrison in Dieppe – Return to Paris with Lucile and Julie

- Book IV: Chapter 11: Delisle de Sales – Flins – Life of a man of letters

- Book IV: Chapter 12: Men of letters – Portraits

- Book IV: Chapter 13: The Rosanbo family – Monsieur de Malesherbes: his predilection for Lucile – Appearance and transformation of my Sylph

Book IV: Chapter 1: Berlin – Potsdam – Frederick

Berlin, March 1821. (Revised July 1846)

BkIV:Chap1:Sec1

It is a long way from Combourg to Berlin, from a youthful dreamer to an old minister. I find among the words preceding these: ‘In how many places have I already continued writing these Memoirs, and in what place will I finish them?’

Nearly four years have passed between the date when I wrote the facts just recounted and that on which I resume these Memoirs. A thousand things have happened; another man has appeared in me, the politician: I am not much taken with him. I have defended the freedoms of France, which alone can make the legitimate monarchy durable. With the Conservateur I have put Monsieur de Villèle in power; I have seen the Duc de Berry die and honoured his memory. In order to reconcile all parties, I have left France; I have accepted the Berlin Embassy.

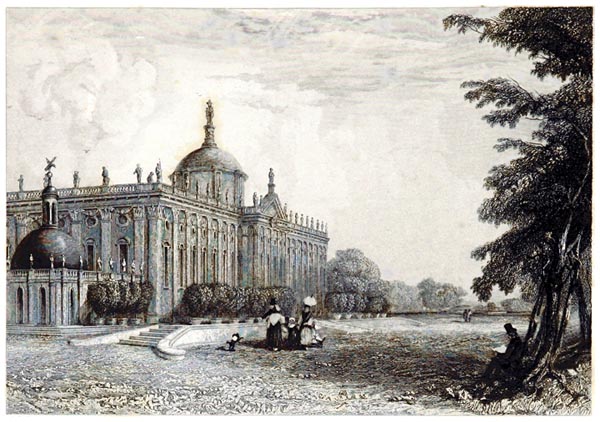

Yesterday I was at Potsdam, an ornate barracks, empty now of soldiers: I studied the imitation Julian in his imitation Athens. At Sans-Souci they showed me the table at which a great German monarch turned the Encylopedists’ maxims into little French verses; Voltaire’s room, decorated with wooden apes and parrots, the mill which he who ravaged whole provinces made a point of respecting, the tombs of the horse César and the greyhounds Diane, Amourette, Biche, Superbe and Pax. The royal infidel even took pleasure in profaning the religion of the tomb by raising mausoleums to his dogs; he had marked out a burial-place for himself, less from contempt for men, than to display his belief in nothingness.

They took me to see the new palace, already decaying. In the old palace of Potsdam they preserve the tobacco stains, the worn and soiled armchairs; indeed every relic of the renegade prince’s un-cleanliness. These places at once immortalise the dirtiness of the cynic, the impudence of the atheist, the tyranny of the despot, and the glory of the soldier.

‘The University of Potsdam’

Asher's Picture of Berlin and its Environs - Adolph Asher (p113, 1837)

The British Library

Only one thing attracted my attention: the hands of a clock frozen at the moment when Frederick expired; I was deceived by the immobility of the image: hours do not suspend their flight; it is not man that stops time, it is time that stops man. What is more, it does not matter what part we have played in life; the brilliance or obscurity of our doctrines, our wealth or poverty, our joys or sorrows make no difference to our length of days. Whether the hands of the clock circle a golden face or a wooden one, whether the face, large or small, fills the bezel of a ring, or the rose-window of a cathedral, the hour has only the one duration.

BkIV:Chap1:Sec2

In a vault of the Protestant Church, immediately beneath the chair of the defrocked schismatic, I saw the tomb of the royal sophist. The tomb is of bronze; when one strikes it, it rings. The gendarme who sleeps in that bronze bed, could not even be dragged from sleep by the noise of his fame; he will not wake till the trumpet sounds, when it will call him onto his last field of battle, face to face with the God of armies.

I had such a need to alter the impression I had received, that I sought relief by visiting the Maison-de-Marbre. The king who had ordered its construction had addressed a few honourable words to me formerly, when, as a humble officer, I passed through his army. At least this king shared the ordinary weaknesses of humanity; commonplace, like them, he took refuge in his pleasures. Do those two skeletons go any way to explain today the difference that formerly existed between them, when one was Frederick the Great, and the other Frederick-William II? Sans-Souci and the Maison-de-Marbre are equally ruins without a master.

All in all, though the enormity of the events of our day diminishes those of the past, though Rosbach, Lissa, Liegnitz, Torgau etc, etc, were only skirmishes compared with the battles of Marengo, Austerlitz, Jena, Moscow, Frederick suffers less than others when compared with the giant chained in St Helena. The King of Prussia and Voltaire are two of the oddest figures to be grouped together who ever lived: the latter destroyed a society with the same philosophy that allowed the former to found a kingdom.

The evenings in Berlin are long. I occupy a house belonging to Madame the Duchess of Dino. At nightfall, my secretaries leave me. When there is no entertainment at court for the marriage of the Grand Duke and Grand Duchess Nicholas (now the Emperor and Empress of Russia: Note, 1832), I stay in. Sitting alone in front of a cheerless stove, I hear nothing but the shouts of the sentinel at the Brandenburg Gate, and the steps in the snow of the man who whistles the hours. How shall I spend my time? Reading? I have scarcely a book. What if I were to continue my Memoirs?

BkIV:Chap1:Sec3

You had left me on the road from Combourg to Rennes: I alighted in the latter town at the house of one of my relations. He told me with great delight that a lady of his acquaintance, travelling to Paris, had a spare seat in her carriage, and that he would try hard to persuade this lady to take me with her. I accepted; cursing my relative’s courtesy. He settled the matter, and soon presented me to my travelling companion, a sprightly, unselfconscious milliner, who burst out laughing on seeing me. At midnight the horses arrived and we set off.

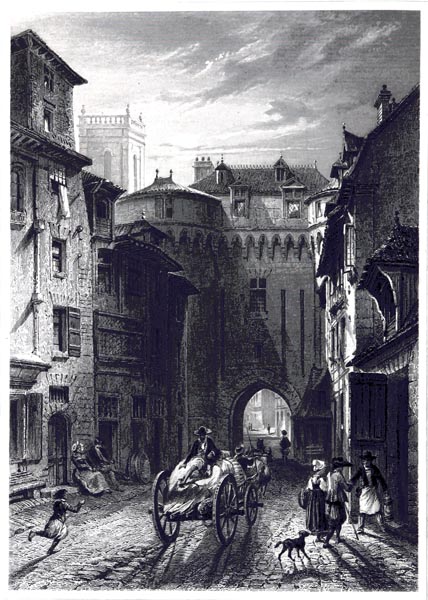

‘Rennes’

Histoire des Villes de France, Vol 03 - Aristide Guilbert (p58, 1844)

The British Library

There I was in a post-chaise, alone with a woman, in the middle of the night. How was I, who had never in my life looked at a woman without blushing, to descend from the height of my dreams to this terrifying reality? I did not know where I was; I huddled in my corner of the carriage for fear of touching Madame Rose’s dress. When she spoke to me, I stammered unable to reply. She was obliged to pay the postilion, and see to everything, since I was incapable of anything. At daybreak, she looked with fresh amazement at this booby with whom she regretted being saddled.

As soon as the local scenery began to change, and I no longer recognised the clothes and accents as those of Breton peasants, I fell into a profound depression, which increased the contempt Madame Rose had for me. I became aware of the sentiment I had inspired, and I received from this first trial in the world an impression that time has not completely effaced. I was born unsociable but unashamed; I felt the modesty of my years, but no embarrassment. When I realised that this fine aspect of my nature made me ridiculous, my unsociability turned into an insurmountable shyness. I could not speak another word: I felt I had something to hide, and this something was a virtue; I made up my mind to conceal myself in order to wear my innocence in peace.

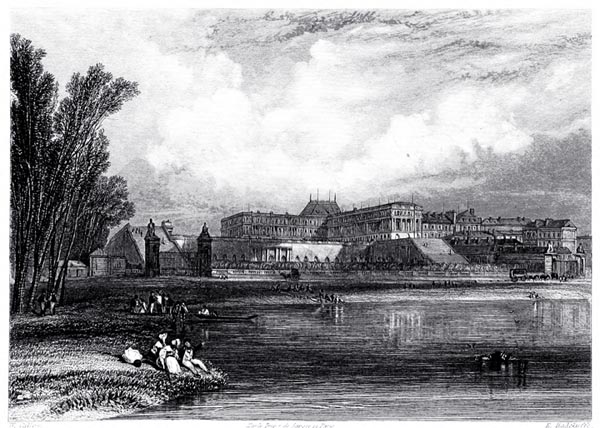

We drew nearer Paris. On the way down from Saint-Cyr, I was struck by the width of the roads and the neatness of the fields. Soon we reached Versailles: the orangery and the marble stairs amazed me. The success of the American war had garnered trophies for Louis XIV’s palace; the Queen reigned there in all the splendour of her youth and beauty; the throne, so close to its fall, seemed never to have been more stable. And I, an obscure passer-by, was destined to survive this pomp, and live to see the woods of Trianon as empty as those I had just left behind.

‘L'Orangerie de Versailles’

Les Fastes de Versailles; Son Château, Son Origine, Ses Légendes, Ses Galeries - Hippolyte Nicolas Honoré Fortoul (p258, 1858)

The British Library

At last we entered Paris. I discovered a mocking expression on every face: like the gentleman from Périgord in Moliere, I thought that they were gazing at me to make fun of me. Madame Rose had me taken to the Hôtel de l’Europe in the Rue du Mail and hastened to disburden herself of her simpleton. Scarcely had I descended from the carriage, than she said to the porter: ‘Give this gentleman a room’- She added: ‘Your servant,’ making me a slight curtsy. I have never seen Madame Rose again in my life.

Book IV: Chapter 2: My Brother – My Cousin Moreau – My sister the Comtesse de Farcy

Berlin, March 1821.

BkIV:Chap2:Sec1

A woman mounted a steep, dark staircase in front of me, holding a labelled key in her hand; a Savoyard followed me with my little trunk. Reaching the third floor, the servant opened a door; the Savoyard placed the trunk across the arms of a chair. The servant said: ‘Does Monsieur require anything? – ‘No’, I replied. Three loud whistles were emitted; the servant shouted: ‘I’m on my way!’ rushed out, closing the door, and tumbled down the stairs with the Savoyard. When I found myself shut in, alone, my heart tightened in such a strange manner I was near to taking the road back to Brittany. Everything I had heard about Paris returned to my mind; I was embarrassed in a hundred ways. I would have liked to go to bed, and the bed was unmade; I was hungry but I did not know how to dine. I was afraid of not knowing how to act: ought I to call the hotel staff? Ought I to go downstairs? To whom should I speak? I ventured to put my head out of the window: I could only see a little inner yard, as deep as a well, where people went to and fro without a thought in their life for the prisoner on the third floor. I went and sat down again near the dirty alcove where I was to sleep, reduced to contemplating the personages on the paper with which its walls were hung. A distant sound of voices was heard, grew louder, neared, my door opened: in came my brother and one of my cousins, son of one of my mother’s sisters who had made rather a poor marriage. Madame Rose had taken pity on the half-wit after all; she had sent word to my brother, whose address she had been given at Rennes, to say that I had arrived in Paris. My brother embraced me. My cousin Moreau was a large, fat man, smeared all over with snuff, who ate like an ogre, talked a great deal, was always moving about, puffing, choking, mouth half-open, tongue half-out, who knew everybody, and spent his life in gambling dens, ante-rooms, and salons. ‘Well, Chevalier,’ he cried, ‘here you are in Paris; I’m going to take you to Madame Chastenay’s! Who was this woman whose name I heard pronounced for the first time? The suggestion turned me against my cousin Moreau. ‘No doubt the Chevalier is in need of rest,’ said my brother; ‘we will go and see Madame de Farcy, then he shall return for dinner and go to bed.’

A joyful feeling entered my heart: the memory of my family in the midst of an indifferent world was like balm to me. We went out. Cousin Moreau raised a storm on the subject of my wretched room, and urged my host to install me at least one floor lower down. We climbed into my brother’s carriage, and drove to the convent where Madame de Farcy lived.

BkIV:Chap2:Sec2

Julie had been in Paris for some time, to consult the doctors. Her charming face, her elegance and her wit had soon made her much sought after. I have already said that she was born with a true poetic talent. She has become a saint, having been one of the most attractive women of her generation: the Abbé Carron has written her life. Those apostles who travel everywhere seeking souls, feel the love for them that a Father of the Church attributed to the Creator: ‘When a soul arrives at God’: said this Father, with the simplicity of heart of an early Christian, and the naivety of Greek genius, ‘God takes her on his knees, and calls her his daughter.’

Lucile has left behind a poignant lamentation: ‘To the sister I no longer have’. The Abbé Carron’s admiration for Julie explains and justifies Lucile’s words. The life written by a holy priest also shows that I spoke the truth in the preface to my Génie du Christianisme, and serves as proof of certain elements of my Memoirs.

Julie an innocent gave herself to repentance; she devoted the riches won from her austerities to redeeming her brothers; and following the example of the illustrious African woman who was her patron saint, she became a martyr.

The Abbé Carron, author of the Vie des Justes, is that ecclesiastic, my compatriot, the François de Paule of the exiles, whose fame attested to by the afflicted, even cut across the fame of Bonaparte. The voice of a poor proscribed clergyman was not stifled by the noise of a Revolution that overwhelmed society; he seemed to have been brought back expressly from a foreign country to pen my sister’s virtues: he sought amongst our ruins; he discovered a victim and a forgotten tomb.

When the new hagiography depicted Julie’s sacred sufferings, one thought one was hearing Bossuet in his sermon on Mademoiselle de La Vallière’s profession of faith.

‘Shall it dare to be concerned about that body so tender, so dear; so gentle? Is no pity to be taken on that delicate complexion? On the contrary! The soul conducts itself towards the body as towards its most dangerous seducer; the soul sets out its boundaries; straightened on all sides, it can only breathe at the side of God.’

I cannot defend myself from a certain embarrassment on finding my name, once more, in the last lines concerning Julie, traced by the hand of the venerable historian. What am I with my frailties doing juxtaposed with such great perfections? Have I adhered to all that my sister’s note made me promise, the one I received during my emigration to London? Does a book satisfy God? Is it not my life I must offer up to Him? And is that life in accord with the Génie du Christianisme? What matter that I have painted more or less brilliant pictures of religion, if my passions cast a shadow on my faith! I have not reached the ultimate; I have not adopted the hair-shirt: that tunic added to my viaticum would have drunk and dried up my sweat. But I, a weary traveller, sit by the side of the road: tired or not, I must rise again to reach the place my sister reached.

Julie’s fame lacks for nothing: the Abbé Carron has written her life; Lucile has mourned her death.

Book IV: Chapter 3: Julie in society – Dinner – Pommereul – Madame de Chastenay

Berlin, 30th March 1821.

BkIV:Chap3:Sec1

When I saw Julie again in Paris, she was in all the pomp of worldly vanity; she appeared covered with flowers, adorned with those necklaces, veiled with those scented fabrics that Saint Clement forbade the early Christians. Saint Basil wanted the middle of the night to be for the solitary what morning is for others, so they might benefit from nature’s silence. The middle of the night was the hour when Julie went to gatherings at which her verses, recited by herself with marvellous musicality, were the principle attraction.

Julie was infinitely lovelier than Lucile; she had tender blue eyes and dark hair which she wore coiled or in waves. Her hands and arms, models of whiteness and form, added by their graceful movements something even more charming to her charming appearance. She was radiant, lively, and laughed often and unaffectedly, showing pearly teeth as she laughed. A host of portraits from Louis XIV’s time resembled Julie, among others those of the three Mortemarts; but she was more elegant than Madame de Montespan.

Julie received me with that tenderness only a sister can show. I felt safe, enfolded by her arms, her ribbons, her lace and her bouquet of roses. Nothing can replace a woman’s loyalty, delicacy and devotion; one is neglected by brothers and friends; one is misjudged by one’s companions; but never by one’s mother, sister or wife. When Harold was killed at the Battle of Hastings, no one could recognise him among the piles of dead; it was necessary to call on a young girl, his beloved. She came, and the unfortunate prince was found by Edith, the swan-necked: ‘Editha swanes-hales, quod sonat collum cygni.’

BkIV:Chap3:Sec2

My brother brought me back to my hotel; he ordered my dinner, and left me. I dined alone, I went sadly to bed. I spent my first night in Paris pining for my moors, and trembling at the uncertainty of my future.

At eight the next morning, my fat cousin arrived; he was already on his fifth or sixth errand. ‘Well, Chevalier! We will breakfast: we will dine with Pommereul, and this evening I will take you to Madame Chastenay’s. This seemed to be my fate, and I resigned myself. All happened according to my cousin’s wishes. After breakfast, he proposed to show me Paris, and dragged me through the dirtiest streets round the Palais-Royal, while telling me about the dangers to which a young man was exposed. We were punctual for our dinner at an eating-house. Everything served to us seemed bad to me. The conversation and the guests revealed a new world to me. The talk was about the Court, financial proposals, sittings of the Academy, the women and intrigues of the day, the latest play, and the successes of actors, actresses and authors.

There were several Bretons among the guests, including the Chevalier de Guer and Pommereul. The latter was a good talker, who has since written about a number of Bonaparte’s campaigns, and whom I was destined to meet again as the Director of Censorship.

Pommereul under the Empire enjoyed some sort of reputation for his hatred of the nobility. When a gentleman was made a chamberlain, he cried out joyfully: ‘Another chamber-pot at the head of these nobles!’ And yet Pommereul claimed, with reason, to be a gentleman. He signed himself Pommereux, being descended from the Pommereux family mentioned in the letters of Madame de Sévigne.

After dinner, my brother wished to take me to the theatre, but my cousin claimed me for Madame de Chastenay, and I went with him to meet my fate.

BkIV:Chap3:Sec3

I saw a beautiful woman, no longer in her first youth, but still capable of inspiring love. She received me with kindness, tried to put me at my ease, and asked me about my province and my regiment. I was gauche and embarrassed; I signalled to my cousin to cut short the visit. But he, without a glance my way, never stopped talking about my merits, declaring that I had written poetry at my mother’s breast, and calling on me to celebrate Madame Chastenay in verse. She freed me from this painful situation, begged my pardon that she was obliged to go out, and invited me to return to see her the following morning, in so sweet a voice that I promised to obey without a thought.

I returned the following day alone: I found her in bed in an elegantly furnished room. She told me that she was a little indisposed, and had the bad habit of rising late. I found myself, for the first time in my life, at the bedside of a woman other than my mother or sister. She had noticed my shyness the previous evening; she overcame it so completely that I dared to express myself with a kind of abandon. I forget what I said to her; but I still seem to see her look of astonishment. She stretched out a half-naked arm to me and the most beautiful hand in the world, saying with a smile: ‘We will tame you.’ I did not even kiss that lovely hand; I withdrew quite confused. I left the next day for Cambrai. Who was that lady of Chastenay? I have no idea; she passed through my life like a charming shade.

Book IV: Chapter 4: Cambrai – The Navarre Regiment – La Martinière

Berlin, March 1821.

BkIV:Chap4:Sec1

The mail-coach took me to my garrison town. One of my brothers-in-law, the Vicomte de Châteaubourg, (he had married my sister Bénigne, the widow of the Comte de Québriac) had given me letters of recommendation to the officers in my regiment. The Chevalier de Guénan, a man who kept very good company, introduced me to a mess where a number of officers dined who were noted for their talents, Messieurs Achard, Des Maillis and La Martinière. The Marqis de Mortemarte was colonel of the regiment, the Comte d’Andrezel, major: I was placed under the special protection of the latter. I met both of them in later years: the former became my colleague in the Chamber of Peers; the other requested of me certain services which I was happy to render him. There is a melancholy pleasure in meeting again with those we have known at different periods of our life, and in considering the changes that have occurred in their existence and ours. Like markers left behind us, they trace the path we have followed through the desert of the past.

‘Cambray (Collège Héraldique)’

Histoire des Villes de France, Vol 03 - Aristide Guilbert (p11, 1844)

The British Library

Joining the regiment in civilian clothes, I had donned a soldier’s garb within twenty-four hours; I felt as if I had worn it always. My uniform was blue and white, like the clothes of my vow years ago: I marched under the same colours, as a child and as a young man. I was submitted to none of the trials which the second-lieutenants were in the habit of inflicting on new recruits; I have no idea why they did not venture to indulge in their military horseplay with me. I was with the regiment scarcely a fortnight before I Was treated as an ‘old hand’. I learnt the theory and practice of fire-arms readily; I passed through the grades of corporal and sergeant to the plaudits of my instructors. My room became the meeting-place for old captains and young second-lieutenants alike: the former went over their campaigns with me; the latter confided their love-affairs.

La Martinière would seek me out to accompany him past the door of one of Cambrai’s beauties whom he adored; this occurred five or six times a day. He was very ugly and his face was pitted with pock-marks. He would tell me of his passion while drinking large glasses of red-currant syrup, which I sometimes paid for.

Everything would have been fine but for my foolish addiction to clothes; the army then affected the severity of Prussian dress: a small cap, little curls worn close to the head, a tightly tied pig-tail, and a carefully buttoned coat. It displeased me greatly; I submitted to these shackles in the morning, but in the evening, when I hoped not to be seen by my superiors, I decked myself out in a much larger hat; the barber brushed out my curls and loosened my pig-tail; I unbuttoned and turned back the facings of my coat; and in this amorous undress I would go courting on La Martinière’s behalf, under the window of his cruel Flemish lady. Then one day I came face to face with Monsieur d’Andrezel: ‘What is this, Sir?’ said the terrible major: ‘Consider yourself under arrest for three days.’ I was humiliated somewhat; but I recognised the truth of the proverb, that every evil contains some good; it delivered me from my friend’s love-affair.

Beside Fénelon’s tomb I re-read Télémaque: I was not really in the mood for the story of the cow and the bishop.

These memories of the start of my career amuse me. Passing through Cambrai with the King, after the Hundred Days, I looked for the place where I once lived, and the coffee-house I used to frequent: I could not find them; everything had vanished, men and monuments.

Book IV: Chapter 5: My father’s death

BkIV:Chap5:Sec1

In the same year that I was serving my military apprenticeship at Cambrai, the death of Frederick II occurred: I am now ambassador to that great king’s great-nephew, and am writing this section of my Memoirs in Berlin. To that news important to the world at large, succeeded other tidings, melancholy ones for me: Lucile wrote to tell me that my father had been carried off by a stroke, on the eve of the Angevin Fair, which was one of my childhood joys.

Among the authentic documents that serve to guide me I find my parents’ death certificates. I record these certificates, which also in their particular way signify the death of an age, here, as a page of history.

Extract from the register of deaths of Combourg Parish, for 1786, in which is written what follows, folio 8, verso:

‘The body of the noble and puissant my Lord René de Chateaubriand, Knight, Count of Combourg, Lord of Gaugres, Le Plessis-l’Épine, Boulet, Malestroit en Dol, and other places, husband of the noble and puissant lady Apolline-Jeanne-Suzanne de Bedée de la Bouëtardais, Countess of Combourg, aged about sixty-nine years, who died in his Château of Combourg, on the sixth of September, at about eight in the evening, has been buried on the eighth, in the family crypt, situated in the body of our church at Combourg, in the presence of the noblemen, judicial officers and other worthy burghers undersigned. Signatories to the register: the Comte du Petitbois, de Montlouët, de Chateaudassy, Delaunay, Morault, Noury de Mauny, barrister; Hermer, prosecutor; Petit, barrister and prosecutor fiscal; Robiou, Portal, Le Douarin de Trevelec, dean of Dingé; Sévin, rector.’

In the collation issued in 1812 by Monsieur Lodin, mayor of Combourg, the nineteen words indicating titles: noble and puissant my Lord, etc, are crossed out.

Extract from the register of deaths for the town of Saint-Servan, first district of the department of Îlle-et-Vilaine, for Year VI of the Republic, folio 35, recto, in which is written what follows:

‘The twelfth Prairial, in year six of the French Republic, before me, Jacques Bourdasse, municipal officer for the district of Saint-Servan, elected as public official on the fourth of Floreal last, appear Jean Baslé, gardener, and Joseph Boulin, day labourer, who have attested that Apolline-Jeanne-Suzanne de Bedée, widow of René-Auguste de Chateaubriand, died at the house of citizeness Gouyon, situated at La Ballue, in that district, this day, at one hour after noon. After this declaration, of whose truth I am assured, I have drawn up the present certificate, which Jean Baslé alone has signed with me, Joseph Boulin having declared that he does not know how, on being questioned concerning this.

Written in the public office, on the said year and day. Signed Jean-Baslé and Bourdasse.’

In the first extract, the old society endures: Monsieur de Chateaubriand is a noble and puissant lord, etc., etc.: the witnesses are noblemen and worthy burghers; among the signatories I find the Marquis de Montlouët, who used to stay at the château of Combourg in the winter, the Abbé Sévin, who found it so hard to believe I was the author of Le Génie du Christianisme, faithful guests of my father’s even in his last abode. But my father did not lie in his shroud for long: he was thrown out of it, when the France of old was thrown on the dung-heap.

In my mother’s death certificate, the globe turns on another axis; a new world, a new era; the computation of the years and even the names of the months have altered. Madame de Chateaubriand is merely a poor woman who dies in the house of Citizeness Gouyon; a gardener, and a day-labourer who cannot sign his name, are the sole witnesses to my mother’s death: no relatives or friends; no funeral ceremony; the only bystander, the Revolution. (My nephew according to the Breton manner, Fréderic de Chateaubriand, son of my cousin Armand, bought La Ballue, where my mother died.)

Book IV: Chapter 6: Regrets – Would my father have appreciated me?

Berlin, March 1821.

BkIV:Chap6:Sec1

I mourned Monsieur de Chateaubriand: his death showed me his worth more clearly; I remembered neither his severities nor his weaknesses. I seemed to see him still, walking of an evening in the Great Hall of Combourg; I was moved by thoughts of those family scenes. If my father’s affection for me suffered from the rigidity of his character, it was none the less deep. The fierce Marshal de Montluc, who, rendered nose-less by dreadful wounds, was reduced to hiding the horror of his glory under a piece of shroud, that man of bloodshed, reproached himself for his harshness towards a son he had lost.

‘That poor lad,’ he said, ‘never saw anything of me but a grim and scornful countenance; he has died in the belief that I could neither love him nor estimate him at his proper worth. For whom was I saving the singular affection I felt for him in my soul? Was it not he who should have had all the pleasure and the obligation? I was constrained and tormented to wear that false mask, and thereby lost the pleasure of his conversation, and his affection, also, since he cannot have felt anything but cool towards me, having never received anything from me but harshness, nor experienced anything but a tyrannical manner.’

My affection was never cool towards my father, and I have no doubt that, despite his tyrannical manner, he loved me tenderly: he would have grieved for me, I am sure, if Providence had called me, before him. But if we had remained on earth together, would he have appreciated the noise my life has made? A literary reputation would have wounded his sense of nobility; he would have seen nothing in his son’s gifts but degeneration; even the Berlin embassy, won by the pen, and not the sword, would have satisfied him little. His Breton blood, moreover, made him a political malcontent, a great opponent of taxation and a violent enemy of the Court. He read the Gazette de Leyde, the Journal de Francfort, the Mercure de France, and the Histoire philosophique des deux Indes, whose declamatory style delighted him: he called the Abbé Raynal a master-mind. In diplomatic matters he was anti-Muslim; he declared that forty thousand Russian rascals would march over the Janissaries’ bellies and take Constantinople. Yet Turkaphobe though he was, my father none the less bore a grudge against the Russian rascals because of his encounters with them at Danzig.

I share Monsieur de Chateaubriand’s sentiments concerning literary and other reputations, but for different reasons to his. I don’t know in history of a fame that tempts me: if I had to stoop to pick up at my feet and to my profit the greatest glory in the world, I would not weary myself doing so. If I had moulded my own clay, perhaps I would have created myself as a woman, for love of them; or if I had created myself as a man, I would have endowed myself with beauty above all; then, as a precaution against ennui, my relentless enemy, it would have suited me to be a great artist, but an unknown one, only employing my talent for the benefit of my solitude. In life, weighed by its light weight, measured by its short measure, stripped of all deception, there are only two true things: religion coupled with intelligence, love coupled with youth, that is to say the future and the present: the rest is not worth the trouble.

With my father’s death, the first act of my life ended: the paternal halls became empty; I pitied them, as if they were capable of feeling solitude and abandonment. Henceforth I was independent and master of my fortune: the freedom scared me. What should I do with it? To whom should I give it? I mistrusted my powers; I shrank from myself.

Book IV: Chapter 7: Return to Brittany – A stay with my eldest sister – My brother summons me to Paris

Berlin, March 1821.

BkIV:Chap7:Sec1

I was given a furlough. Monsieur d’Andrezel, appointed Lieutenant-Colonel of the Picardy Regiment, was leaving Cambrai: I acted as his courier. I passed through Paris, where I did not wish to stop for even a quarter of an hour; I saw the moors of my Brittany again with more joy than a Neapolitan banished to our climes would look once more on the shores of Portici, the fields of Sorrento. My family gathered at Combourg; we divided the inheritance; that done we dispersed like birds leaving the paternal nest. My brother, who had arrived from Paris, returned; my mother settled at Saint-Malo; Lucile went with Julie; I spent part of my time with Mesdames de Marigny, de Chateaubourg, and de Farcy.

Marigny, my eldest sister’s chateau, seven miles from Fougères, is pleasantly situated between two lakes among woodland, rocks and meadows. I lived there tranquilly for a few months; a letter from Paris arrived to trouble my peace.

On the point of entering the service, and marrying Mademoiselle de Rosanbo, my brother had not yet abandoned the magistrate’s long robe; for this reason he was not entitled to ride in the royal coaches. His relentless ambition urged on him the idea of obtaining for me the enjoyment of Court honours, in order to prepare the way more readily for his own elevation. Our proofs of nobility had been drafted for Lucile, when she was admitted to the Chapter of L’Argentière; so that all was prepared: the Marshal de Duras would act as my sponsor. My brother wrote to tell me I was on the road to fortune; that I had already been granted the rank of cavalry captain, an honorary, courtesy ranking; that it would be an easy matter next to have me admitted to the Order of Malta, by means of which I would enjoy rich benefices.

This letter struck me like a thunderbolt: to return to Paris, to be presented at Court – and I someone disturbed to the point of illness when I met two or three unknown people in a drawing-room! To fill me with ambition, I who only dreamed of living in obscurity!

My first instinct was to reply to my brother that being the eldest it was for him to uphold his name; that, as for me, an obscure Breton younger son, I would not resign from the service, because there was a possibility of war; but that if the king needed a soldier for his army, he did not need a poor gentleman at his Court.

I lost no time in reading this romantic reply to Madame de Marigny, who uttered piercing cries; Madame de Farcy was sent for, who mocked me; Lucile would have genuinely supported me, but she dare not oppose her sisters. They snatched my letter away, and weak as always where I am concerned, I wrote to my brother that I was ready to go.

And so I went; I went to be presented at the first Court of Europe, to commence life in the most brilliant manner, and I had the air of a man being dragged to the galleys, or on whom a sentence of death is about to be pronounced.

Book IV: Chapter 8: My solitary life in Paris

Berlin, March 1821.

BkIV:Chap8:Sec1

I entered Paris by the same route I had followed the first time; I went to the same hotel, in the Rue du Mail: it was the only one I knew. I was lodged near my old room, but in a slightly larger apartment overlooking the street.

My brother, either because he was embarrassed by my manners, or because he took pity on my shyness, did not take me into society and did not force me to make anyone’s acquaintance. He lived in the Rue des Fossés-Montmartre; I would go there to dine with him every day at three o’clock; we parted afterwards and did not meet again until the next day. My fat cousin Moreau was no longer in Paris. I walked past Madame de Chastenay’s house two or three times, without daring to ask the porter what had become of her.

Autumn commenced. I rose at six; I went to the riding-school; I breakfasted. Fortunately I had a passion for Greek at that time: I translated the Odyssey and the Cyropaedia until two, interspersing my labours with historical studies. At two I dressed and went to my brother’s; he would ask me what I had been doing; I replied: ‘Nothing.’ He shrugged his shoulders and turned his back on me.

One day there was a noise outside, my brother ran to the window, and called me over: I refused to quit the armchair in which I was sprawling at the back of the room. My poor brother prophesied that I would die unknown, useless to myself or my family.

At four, I returned to the hotel: I sat at my casement. Two young girls of fifteen or sixteen would come and sketch at that hour at the window of a house opposite, across the street. They had noticed my punctuality, as I had theirs. From time to time they raised their heads to look at their neighbour: they were my only company in Paris.

At nightfall I went to some play or other: the desert of the crowd pleased me, though it always cost me a little effort to buy my ticket at the door and mix with mankind. I revised my idea of the theatre formed in Saint-Malo. I saw Madame Saint-Huberty in the role of Armida, I felt there had been something lacking in the sorceress of my imagination. When I failed to imprison myself in the Opera House or the Français, I would wander from street to street or along the embankments until ten or twelve at night. I cannot see the row of streetlamps from the Place Louis XV to the Barrière des Bons-Hommes, to this day, without remembering the agonies I went through as I took that route to reach Versailles for my presentation.

‘Intérieur d'une Loge de l'Opéra’

L'Été à Paris - Jules Gabriel Janin (p192, 1843)

The British Library

Returning to my lodgings, I spent part of the night with my face turned to the fire, which spoke not a word to me: I had not, as the Persians have, a rich enough imagination to liken the flame to an anemone, and its embers to a pomegranate. I heard the carriages coming and going and passing each other; their distant rumble was like the murmur of the sea on my Breton shores, or the wind in my woods at Combourg. These worldly noises which recalled those of solitude woke my regrets; I called to mind my old malady, whereby my imagination easily invented the tale of those whom the vehicles carried: I saw radiant salons, balls, love-affairs, conquests. Soon, falling back upon myself, I found myself once more abandoned to a hotel, gazing at the world through the window, and hearing it in the echoes of my abode.

BkIV:Chap8:Sec2

Rousseau thinks he owes to his sincerity, as to the education of mankind, the confession of his life’s dubious pleasures; he even supposes that he is being interrogated gravely and asked for an account of his sins with dangerous women, the donne pericolanti, of Venice. If I had whored among the Parisian courtesans, I would not have felt obliged to tell posterity about it: but I was too shy on the one hand, too exalted on the other, to allow myself to be seduced by prostitutes. When I met a crowd of those wretched women accosting passers-by in order to drag them upstairs, as Saint-Cloud cabmen try to entice travellers into their cabs, I was seized by horror and disgust. The pleasures of adventure would not have suited me as in times past.

In the fourteenth, fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, an imperfect civilisation, superstitious beliefs, alien and semi-barbarous customs, are met with everywhere in story: the characters are noble, imagination powerful, existence secret and mysterious. At night, round the high walls of cemeteries and convents, beneath the deserted town ramparts, in the channels and ditches of the market-places, at the edges of fenced areas, in the narrow noiseless streets, where thieves and assassins set up ambushes, where meetings took place now by the light of torches, now among dense shadows, one sought out the rendezvous appointed by some Héloïse at peril of one’s life. To give oneself over to disorder, it is necessary to truly love: to violate the common morality, it is necessary to make great sacrifices. It is not merely a question of confronting chance perils, and braving the blade of the law, but one is required to conquer in oneself the influence of customary habit, family authority; the tyranny of domestic custom, the opposition of one’s conscience, the terrors and obligations of a Christian. All these obstacles increase the energy of the passions.

In 1788 I would not have followed a starving wretch who tried to drag me into her hovel under the watching eye of the police; while in 1606 I would probably have pursued to the end such an adventure as Bassompierre tells so well.

BkIV:Chap8:Sec3

‘For five or six months,’ the Marshal writes, ‘every time I crossed the Petit-Point (since at that time the Pont-Neuf had not yet been built) a lovely woman, a laundry girl at the sign of the Two Angels, made me a deep curtsey and followed me with her eyes as long as she could; and as I was wary of her actions, I glanced at her too and saluted her with care.

It so happened that whenever I arrived in Paris from Fontainebleau, crossing the Petit-Pont, as soon as she saw me coming, she would stand in the entrance to her shop, and say, as I passed: “Monsieur, I am your servant.” I returned her greeting, and glancing back from time to time, I saw that she followed me with her eyes as long as she could.’

Bassompierre obtained an assignation: ‘I found there,’ he says, ‘a very lovely girl, of twenty years of age, her hair arranged for bed, clothed in nothing but a very thin chemise and a little skirt of green material, slippers on her feet, and her robe round her. She pleased me greatly. I asked her if I might see her again. “If you wish to see me again,” she said, “it shall be at my aunt’s house, she lives in the Rue Bourg-l’Abbé, close to Les Halles, near to the Rue aux Ours, behind the third door towards the Rue Saint-Martin; I will wait for you there from six till midnight, or even later; I will leave the door unlocked. At the entrance there is a little path you must pass quickly, since my aunt’s room leads off it, and you will find a stair that will take you to the second floor.” I arrived at ten, and found the door she had signified to me, with a bright light shining, not only on the second floor, but the third and first too; but the door was locked. I knocked to warn her of my arrival; but I heard a man’s voice demanding who I was. I had returned to the Rue aux Ours, and was returning a second time, when I found the door open, and climbed to the second floor, where I found that the light came from a bed of straw that had been set alight, and that there were two naked bodies laid out on a table in the room. Then I retired, completely dumbfounded, and in leaving encountered the crows (buriers of the dead) who asked me what I wanted; I, to push them aside, took my sword in hand, and ignoring them, returned to my lodgings, somewhat disturbed by the unexpected sight.’

I went in turn to find the address Bassompiere had given, two hundred and forty years later. I crossed the Petit-Pont, traversed Les Halles, and followed the Rue Saint-Denis to the Rue aux Ours on the right; the first street on the left after the Rue aux Ours is the Rue Bourg-l’Abbé. Its sign, blackened as if by time and flames, inspired me with hope. I found the third little door towards the Rue Saint Martin, to that extent the historian’s information was correct. There, unfortunately, the two and a half centuries that I thought still cloaked the street, vanished. The façade of the house was modern; no light shone from the first, second or third floor. In the attic windows, under the roof, a tangle of nasturtiums and sweet-peas flowered: on the ground floor a hairdresser’s salon offered a host of wigs, displayed behind the glass.

Disappointed, I entered this Museum of Éponine: since the Roman conquest, the Gauls have always sold their blonde tresses to those with less favoured heads: my Breton compatriots still cut their hair on certain feast days, and barter their natural covering for an Indian handkerchief. Addressing myself to the hairdresser, who was drawing a wig over an iron comb: ‘Monsieur, have you purchased the hair of a young laundry-girl, who lives at the sign of the Two Angels, near the Petit-Pont?’ He stopped, amazed, unable to say yes or no. I retired, with a thousand apologies, through a labyrinth of toupees.

I wandered afterwards from door to door; no twenty-year old washerwoman made me a deep curtsey; no young girl, candid, selfless, passionate, her hair arranged for bed, clothed in nothing but a very thin chemise and a little skirt of green material, slippers on her feet, and her robe round her. A grumpy old woman, ready to rejoin her teeth in the tomb, decided to beat me with her crutch: perhaps it was the aunt of that rendezvous.

BkIV:Chap8:Sec4

What a lovely story that story of Bassompierre’s! It helps if one understands one of the reasons why he was loved so resolutely. At that time, the French were still divided into two distinct classes, one dominant, the other subservient. The laundry-girl clasped Bassompierre in her arms, as if he were a demi-god descending to the breast of a slave: he gave her the illusion of glory, and French girls, alone among women, are capable of being intoxicated by that illusion.

But who can reveal the unknown cause of the catastrophe to us? Was it that kind little working class girl of the Two Angels whose body lay on the table with some other? Whose was the other corpse? Her husband’s or the man whose voice Bassompierre heard? Did plague (since there was plague in Paris) or jealousy rush down the Rue Bourg-l’Abbé ahead of love? The imagination easily exercises itself over such a subject. Mingle with the inventions of the poet of popular opera, the gravediggers arrival, the crows meeting Bassompierre’s sword, and a superb melodrama would be produced from the affair.

You may admire too the chastity and self-restraint of my youthful days in Paris: in that capital, it would have been permissible for me to have surrendered myself to my every whim, as in the Abbey of Thélème, where everyone did as he wished; nevertheless I did not abuse my independence: I only had commerce with a two hundred and sixteen year old courtesan, loved long ago by a Marshal of France, the rival of the Béarnais in the matter of Mademoiselle de Montmorency, and lover of Mademoiselle d’Entragues, sister of the Marquise de Verneuil, who spoke so ill of Henri IV. Louis XVI who I was going to meet, would not have suspected my secret connection with his family.

Book IV: Chapter 9: Presentation at Versailles – Hunting with the King

Berlin, March 1821.

BkIV:Chap9:Sec1

The dreaded day arrived; I was forced to set out for Versailles, more dead than alive. My brother took me there the day before my presentation and introduced me to Marshal de Duras, a worthy gentleman with a mind so ordinary that it cast something of the commonplace over his fine manners: nevertheless this good Marshal scared me terribly.

Next morning, I went alone to the palace. One has seen nothing, if one has not seen the pomp of Versailles, even after the disbanding of the old royal household: Louis XIV was still there.

Things went well so long as I only had to pass through the guardrooms: military display has always pleased me and never overawed me. But when I entered the Oeuil-de-Boeuf, the ante-chamber to the Great Hall, and found myself among the courtiers, my agony began. They gazed at me; I heard them ask who I was. One must remember the ancient prestige of royalty, to realise the importance of a presentation in those days. A mysterious sense of destiny clung to the debutant; he was spared the patronising contempt, coupled with extreme politeness, which made up the inimitable manners of the grandee. Who could tell whether this debutant might not become the master’s favourite. One respected in him the future familiarity with which he might be honoured. Today we rush to the palace with even more enthusiasm than before, and curiously, without illusions: a courtier reduced to living on truths is not far from death by hunger.

‘Grande Fête du Château de Versailles’

L'Été à Paris - Jules Gabriel Janin (p222, 1843)

The British Library

When the King’s levee was announced, those who had not been presented withdrew; I felt a moment of vanity: I was not proud of remaining, but would have felt humiliated at having to leave. The door of the King’s bed-chamber opened: I saw the King, in accord with custom, complete his toilette that is to say he took his hat from the hands of the first gentleman in waiting. The King passed on his way to Mass; I bowed, Marshal de Duras presented me: ‘Sire, the Chevalier de Chateaubriand.’ The King looked at me, returned my bow, hesitated, and appeared as if he wished to stop and say a word to me. I would have replied with a calm countenance: my shyness had vanished. To speak to the commander of the Army, the Head of State seemed simple enough to me, without my being able to explain why. The King more embarrassed than I was, finding nothing to say to me, passed on. The vanity of human destiny! This sovereign whom I saw for the first time, this monarch so powerful was Louis XVI six years from the scaffold! And this new courtier at whom he scarcely glanced, having been presented on proof of nobility to the grandeur of Saint Louis’ heir, would one day, charged with separating remains from remains, be presented on proof of fidelity to his dust! A twofold mark of respect to the twofold royalty of the sceptre and the palm! Louis XVI might have answered his judges as Christ did the Jews: ‘Many good works I have showed you’.‘for which of those works do you stone me?’

We hurried to the gallery to see the Queen pass on her return from the chapel. She soon appeared with a glittering and crowded retinue; she made us a stately curtsey; she seemed enchanted with life. And those lovely hands which bore then the sceptre of so many kings with so much grace, were destined, before being bound by the executioner, to mend the rags of the widow imprisoned in the Conciergerie!

Though my brother had obtained a concession from me, it was not in his power to make me pursue it further. He begged me in vain to remain at Versailles in order to attend the Queen’s card-play in the evening: ‘You will be presented to the Queen, ‘he told me, ‘and the King will speak to you.’ He could not have given me a better reason for flight. I hastened to go and hide my glory in my furnished room, happy to have escaped the Court, but seeing before me, still to come, the terrible day of the carriages, the 19th February 1787.

BkIV:Chap9:Sec2

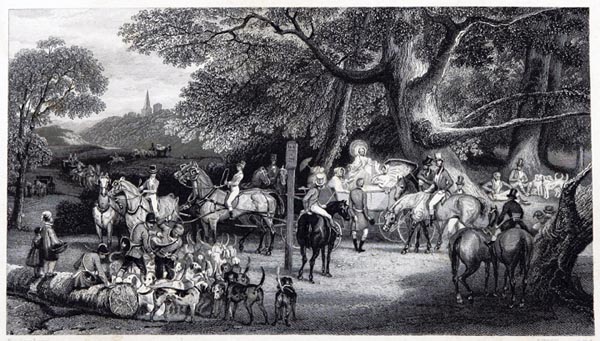

The Duc de Coigny informed me that I was to hunt with the King in the forest of Saint-Germain. Early in the morning I headed for my torment, dressed as a debutant in a grey coat, red jacket and breeches, lace-topped riding boots, a hunting knife at my side, and a little gold-laced French hat. There were four of us debutants at the Palace of Versailles, myself; the two Messieurs de Saint-Marsault, and the Comte d’Hautefeuille. (I have met Monsieur the Comte d’Hautefeuille again: he is translating a number of pieces by Byron; Madame the Comtesse d’Hautefeuille is the talented author of l’Âme exilée etc.) The Duc de Coigny gave us our instructions: he advised us not to interfere with the hunt as the King was angered if anyone came between him and the quarry. The Duc de Coigny bore a name fatal to the Queen. The meet was at Le Val in the forest of Saint-Germain, an estate leased by the crown from Marshal de Beauvau. Custom decreed that the horses of a first hunt in which debutants took part were provided by the royal stables. (The Gazette de France for Tuesday 27th February 1787 reads as follows: ‘Comte Charles d’Hautefeuille, the Baron de Saint-Marsault, the Baron de Saint-Marsault-Chatelaillon, and the Chevalier de Chateaubriand who had previously had the honour of being presented to the King, have received on the 19th, that of riding in his Majesty’s carriages, and following the chase.’)

The guard beat the salute: at the voice of command, they presented arms. There was a shout of: ‘The King!’ The King appeared, and entered his carriage: we rode in the carriages behind. It was a far cry from this expedition and hunt with the King of France, to my hunting trips on the Breton moors, and an even further cry to my hunting trips with the savages of America: my life would be full of these contrasts.

‘Le Rendezvous de Chasse’

L'Été à Paris - Jules Gabriel Janin (p116, 1843)

The British Library

We reached the rallying-point, where a number of saddle horses, held in hand under the trees, showed their impatience. The carriages with their guards drawn up in the forest; the groups of men and women; the packs barely retrained by the huntsmen; the hounds barking, horses neighing, the sound of the horns, made a very lively picture. The hunts of our kings recalled both the ancient and new customs of the monarchy, the rough pastimes of Clodion, Chilpéric, and Dagobert, the elegant enjoyments of François I, Henri IV, and Louis XIV.

I was too full of my reading not see everywhere Comtesses de Chateaubriand, Duchesses d’Etampes, Gabrielles d’Estrées, La Vallières, and Montespans. My imagination seized on the historic aspect of this hunt, and I felt at ease; besides I was in a forest, I was at home.

BkIV:Chap9:Sec3

Descending from the carriage, I gave my ticket to the huntsman. A mare called L’Heureuse had been chosen for me, a swift creature, but hard-mouthed, skittish and capricious; a fair enough likeness of my fate, which never ceases to set back its ears. The King having mounted departed; the hunt followed, taking different routes. I was left behind, struggling with L’Heureuse who would not let her new master straddle her; however, in the end, I did manage to leap on her back: the hunt was already far off.

At first I mastered L’Heureuse well enough; forced to shorten her pace, she bowed her neck, shook her bit white with foam, and bounded along sideways; but once she neared the scene of the action, there was no holding her. She stretched out her head, forcing my hand down to her neck, and galloped straight into a knot of hunters, sweeping aside all in her way, and stopping only when she collided with the mount of a woman whom she almost knocked to the ground, in the midst of shouts of laughter from some, cries of fear from others. I have tried in vain today to remember the name of the woman, who accepted my apology politely. Nothing else was spoken of but the debutant’s adventure.

I had not reached the end of my trials. About half an hour after my mishap, I was riding across a lengthy clearing in a deserted part of the woods: there was a summerhouse at the end: there I began to think about these palaces scattered about the Crown forests, in memory of the long-haired kings and their mysterious pleasures: a shot rang out; L’Heureuse veered sharply, plunged head first into a thicket, and carried me to the very spot where the roe-buck had just been killed: the King appeared.

Then I remembered, too late, the Duc de Coigny’s warning: the wretched Heureuse had done for me. I leapt to the ground, pushing my mare back with one hand and sweeping my hat off with the other. The king stared; he felt he should speak; instead of being angered, he said in a good-natured tone, and with a loud laugh: ‘He did not hold out long.’ That was the only word I ever had from Louis XVI. People arrived on every side; they were amazed to find me talking with the King. The debutant Chateaubriand made a noise with his two adventures; but as has always happened since, he did not know how to profit from his good or bad luck.

The King brought three other roe-bucks to bay. Debutants were only allowed to pursue the first animal, so I went back to Le Val to wait with my companions for the hunt to return.

The King rode back to Le Val; he was cheerful and talked of the incidents during the chase. We took the road for Versailles. There was a fresh disappointment for my brother: instead of going off to dress, in order to attend the un-booting, a moment of triumph and favour, I threw myself into my carriage, and returned to Paris, full of joy at being delivered from my honours and tribulations. I told my brother I was determined to return to Brittany.

Content with having made his name known, and hoping one day to bring to maturity by means of his own presentation what had proved abortive in mine, he did not oppose the departure of so eccentric a brother. (The Mémorial historique de la Noblesse has published an unedited document annotated in the King’s hand, taken from the Royal archives, section historique, register M813, and box M814; it contains the attendees. My name and that of my brother are found there, proving that my memory has served me well concerning the dates: Note, Paris 1840).

BkIV:Chap9:Sec4

Such was my first view of Town and Court. Society seemed even more odious than I had imagined; but though it scared me it did not discourage me; I felt, confusedly, that I was superior to what I had seen. I took an unconquerable dislike to the Court; this dislike, or rather contempt, which I have been unable to hide, will prevent my succeeding, or bring about my fall at the very summit of my career

As for the rest, if I judged the world without knowing it, the world, in its turn, ignored me. No one imagined on my debut what I might achieve, and no one was any the wiser when I returned to Paris. Since attaining my melancholy fame, many people have said: ‘How readily we would have noticed you, if we had met you in your youth!’ This kind pretension is no more than an illusion produced by an existing reputation. Men are alike on the outside: it is idle for Rousseau to tell us that he possessed a pair of small but very attractive eyes: it is no less certain witness his portraits that he looked like a schoolmaster or a crotchety cobbler.

To have done with the Court, I should say that having revisited Brittany, and returned once more to live in Paris with my younger sisters, Lucile and Julie, I plunged more deeply than ever into my solitary habits. I have been asked what came of this history of my presentation. It stopped there. – ‘You never hunted with the King again, then?’ – ‘No more than with the Emperor of China.’ – ‘You never returned to Versailles?’ – ‘I twice went as far as Sèvres; courage failed me, and I returned to Paris.’ – So you had no profit from your position?’ – ‘None at all.’ – ‘What did you do then?’ – ‘I got bored.’ – ‘So you felt no ambition?’ – ‘Indeed: by dint of worry and intrigue, I achieved the glory of publishing an idyll in the Almanach des Muses whose appearance nearly killed me with hope and fear. I would have given all the King’s carriages to have written the ballad: O ma tendre musette! (Oh my gentle air!), or De mon berger volage (My faithless shepherd)’

Good for anything on others behalf, good for nothing where I am concerned: there you have me.

Book IV: Chapter 10: Trip to Brittany – Garrison in Dieppe – Return to Paris with Lucile and Julie

Paris, June 1821.

BkIV:Chap10:Sec1

All that has been written so far of this fourth book was written in Berlin. I have returned to Paris for the baptism of the Duc de Bordeaux, and I have resigned my embassy out of political loyalty to Monsieur de Villèle who has left the Ministry. My freedom restored, let me write. The more these Memoirs are filled with the passing years, the more they remind me of the lower bubble of a sand-glass showing how many grains of my life have fallen: when all the sand has passed through, I would not turn over my timepiece of glass, even if God gave me the power to do so.

The new solitude I entered into, in Brittany, after my presentation, was no longer that of Combourg; it was neither as total, nor as profound, nor to tell the truth, as mandatory: I was free to leave; it lost some of its value. An old escutcheoned lady, an old emblazoned baron watching over the last of their sons and daughters in a feudal manor, represented what the English call characters: there was nothing provincial or limited about that life, because it was not an ordinary life.

At my sisters’ homes, the province gathered in the midst of the fields: neighbours danced at neighbours’ houses, or put on plays in which I occasionally acted badly. In winter one suffered the small town society of Fougères, with its balls, assemblies, and dinners, and I could not live forgotten, as in Paris.

On the other hand, I had not viewed the Army and the Court without a change taking place in my ideas: in spite of my natural inclinations, something in me, rebelling against obscurity, urged me to quit the shadows. Julie detested the provinces: while the instinct of genius and beauty impelled Lucile towards a wider stage.

Thus I experienced a feeling of dissatisfaction with my existence which informed me that this existence was not my destiny.

Nevertheless, I still loved the country, and that around Marigny was delightful. (Marigny has changed greatly since the time when my sister lived there. It was sold, and now belongs to the Pommereuls, who have rebuilt and embellished it, significantly.) My regiment had changed quarters: the first battalion was stationed at Le Havre, the second at Dieppe: I rejoined the latter: my presentation made me a personage. I acquired a taste for my profession; I worked at drill; I was put in charge of raw recruits whom I exercised on the pebbly beach: that sea has formed the background to almost all the scenes of my life.

BkIV:Chap10:Sec2

La Martinière occupied himself at Dieppe, with neither his namesake La Martinière, nor with Le Père Simon, who wrote opposing Bossuet, Port-Royal and the Benedictines, nor with the anatomist Pecquet, whom Madame de Sévigné called Little Pecquet; but La Martinière was in love in Dieppe as in Cambrai: he languished at the feet of a formidable lady of Normandy, whose headdress and coiffure were three feet high. She was not young: by a singular coincidence she was named Cauchie, apparently a grand-daughter of that Anne Cauchie of Dieppe, who in 1645 was a hundred and fifty years old!

It was in 1647 that Anne of Austria, looking as I did at the sea through the window of her room, enjoyed watching fire-ships consumed for her diversion. She allowed the people who had remained faithful to Henri IV to guard the young Louis XIV; she blessed them endlessly, despite their vile Norman language.

One found again at Dieppe certain feudal taxes that I had seen levied at Combourg: to a gentleman named Vauquelin were due three pig’s heads each with an orange in its mouth, and three sous stamped from the oldest known coinage.

BkIV:Chap10:Sec3

I returned to Fougères on six months’ leave. There, a noble spinster reigned, named Mademoiselle de La Belinaye, the aunt of that Comtesse de Trojolif, of whom I have spoken. A pleasant but ugly sister of an officer in the Condé Regiment attracted my attention: I would not have been bold enough to raise my eyes to beauty; it was only in the presence of a woman’s imperfections that I dared to venture a respectful homage.

Madame de Farcy, always ailing, finally resolved to leave Brittany. She persuaded Lucile to accompany her; Lucile in turn overcame my reluctance: we took the road to Paris; a sweet association of the three youngest fledglings from the nest.

My brother had married: he was living at the house of his father-in-law, Président de Rosanbo, in the Rue de Bondi. We arranged to settle in the neighbourhood: through the good offices of Monsieur Delisle de Sales, living in the Saint-Lazare villas at the top of the Faubourg Saint-Denis, we secured an apartment in these same villas.

Book IV: Chapter 11: Delisle de Sales – Flins – Life of a man of letters

Paris, June 1821.

BkIV:Chap11:Sec1

Madame de Farcy was acquainted, I know not how, with Deslisle de Sales, who had once been imprisoned at Vincennes for philosophical inanities. At that time, one became an important celebrity when one had scrawled a few lines of prose or inserted a quatrain in the Almanach des Muses. Delisle de Sales, a man of extreme kindness, a cordial mediocrity, had great mental flexibility, and let the years roll by him; this old man had employed his works to collect a fine library which he leant out to strangers and which no one in Paris read. Each year, in spring, he replenished his ideas in Germany. Fat and slovenly, he carried about a roll of filthy paper which one saw him drag from his pocket; on street corners, he consigned to it his thought of the moment. On the pedestal of his marble bust, he had traced this inscription with his own hand, borrowed from Buffon’s bust: God, Man, Nature, he explained them completely. Delisle de Sales explained completely! Those proud words are quite amusing, but quite disheartening. Who can flatter himself he has true talent? Might it not be that, as long as we live, we are all under the power of an illusion like that of Delisle de Sales? I would wager that whichever author penned that phrase thought himself a writer of genius, and yet was no better than a fool.

If I have spent too much time on my account of this worthy man of the Saint-Lazare villas, it is because he was the first literary man I met: he introduced me to the society of others.

The presence of my two sisters rendered my stay in Paris less intolerable; my affinity for study further weakened my distaste. Delisle de Sales seemed an eagle to me. I met Carbon Flins des Oliviers at his house, who fell in love with Madame de Farcy. She teased him; he took it well, since he had pretensions to being good company. Through Flins I met Fontanes, his friends, who became mine also.

Son of a head keeper of lakes and forests at Rheims, Flins education had been severely neglected; for all that he was a man of wit and occasionally talent. No one fatter could be imagined: short and corpulent, with large protruding eyes, tousled hair, blackened teeth, and despite all that a not ignoble air. His mode of life, which was that of almost all the men of letters of Paris at that time, is worth recounting.

Flins lived in an apartment on the Rue Mazarine, quite near Laharpe, who lived in the Rue Guénégaud. Two Savoyards, dressed as lackeys by virtue of their silk livery, served him: in the evenings they followed him about, and they introduced visitors to his house in the mornings. Regularly Flins attended the Théâtre-Français, then in the Place à l’Odéon, and excellent above all for comedy. Brizard was nearing the end of his career; Talma was commencing his, Larive, Saint-Phal, Fleury, Molé, Dazincourt, Dugazon, Grandmesnil, Mesdames Contat, Saint-Val, Desgarcins, Olivier, were at the height of their powers, in the wings was Mademoiselle Mars, daughter of Monvel, ready to make her debut at the Montansier Theatre. Actresses gave their patronage to authors and sometimes made their fortune for them.

Flins, whose allowance from his family was only modest, lived on credit. When Parliament was not sitting, he pawned his Savoyards’ liveries, his two watches, his rings and his linen, paid what he must with the loan, and left for Rheims, stayed there for three months, returned to Paris, redeemed, with the money his father had given him, what he had deposited at the Mont-de-Piété, and recommenced the circle of his life, always cheerful and received everywhere.

Book IV: Chapter 12: Men of letters – Portraits

Paris, June 1821.

BkIV:Chap12:Sec1

During the two years which passed between establishing myself in Paris and the opening of the States-General this social network widened. I knew by heart the elegies of the Chevalier du Parny, and I even knew the author. I wrote to him to ask permission to meet a poet whose works delighted me; he replied politely: I went to his house in the Rue de Cléry.

I found quite a young man, dressed in very good taste, tall, thin, his face marked by smallpox. He returned my visit; I presented him to my sisters. He had little liking for society and he was soon driven from it by his politics: he was then of the ‘old’ party. I have never met a writer who conformed more closely to his work; a poet and a Creole, he only lacked the skies of India, a fountain, a palm-tree and a wife. He dreaded fame, sought to glide through life without being noticed, sacrificed everything to his idleness, and was only dragged from his obscurity by his pleasures which stroked the lyre in passing:

‘Let our life so fortunate and happy

Flow in secret ’neath the wings of love,

Akin to a barely murmuring stream

Constraining its waves within its bed,

That softly seeks the leaves’ shade overhead,

And dare not show itself to all the scene.’

It was the impossibility of escaping from his indolence that turned the Chevalier de Parny from furious aristocrat to wretched revolutionary, attacking persecuted religion and priests on the scaffold, purchasing his peace at any price, and lending to the Muse that sang of Eléonore the language of those places where Camille Desmoulins went to bargain for love.

BkIV:Chap12:Sec2

The author of the Histoire de la litérature italienne, who wormed his way into the Revolution as a follower of Chamfort, met us through that cousinship that all Bretons share. Guinguené existed in the world on the reputation of a graceful enough piece of verse that was worth a minor appointment in Monsieur de Necker’s office to him; from there the piece assured his entry into the Office of Public Finance. I do not know who disputed with Ginguené his famous title, the Confession de Zulmé; but in effect it belonged to him.

The poet from Rennes was familiar with music and composed ballades. Humble as he was, we saw his pride grow, as he clung to someone well-known. Close to the time when the States-General were convened, Chamfort employed him to scribble articles for the journals, and speeches for the clubs; he became haughty. At the first Festival of the Federation he said: ‘What a lovely celebration! To shed more light we should burn four aristocrats at the four corners of the altar.’ He lacked originality in his wish; long before him, the Leaguer, Louis Dorleans, wrote in his Banquet du comte d’Arête: ‘that we must tie protestant ministers like faggots to the branches of the bonfire of Saint-Jean, and put Henry IV in the barrel where they put the cats.’

Ginguené had prior knowledge of the revolutionary atrocities. Madame Ginguené warned my sisters and my wife of the massacre which would take place at the Carmes, and gave them refuge: they were living in the Cul-de-sac Férou, near the place where throats were cut.

After the Terror, Ginguené became virtually the controller of public education; it was then that he sang l’Arbre de la liberté (The Tree of Liberty) to the crowd in the Cadran-Bleu restaurant, to the tune of; ‘Je l’ai planté, je l’ai vu naître’(I planted it, I have seen its birth.) One judges him to have admired philosophy too much to be an ambassador to one of those kings they deposed. He wrote from Turin to Monsieur Talleyrand that he had vanquished a prejudice: he had had his wife received at court in a short skirt. Tumbling from mediocrity into importance, from importance into foolishness, and from foolishness into ridicule, he ended his literary life as a noted critic, and, what is better still, an independent writer for the Décade: nature had returned him to the place from which society had dragged him at just the wrong moment. His knowledge was second-hand, his prose heavy, his poetry correct, and occasionally agreeable.

BkIV:Chap12:Sec3

Ginguené had a friend, the poet Lebrun. Ginguené protected Lebrun, as a man of talent who knows society protects the simplicity of a man of genius; Lebrun in turn shed his rays on Ginguené’s heights. Nothing was more comical than the role of those two accomplices, providing, by means of genteel exchange, all the services that two superior individuals might render in diverse genres.

Lebrun was quite simply an artificial Empire man; his wit was as cold as his enthusiasms were frozen. His Parnassus, an upper room in the Rue Montmartre, offered as its only furniture books piled haphazardly on the floor, a bed made of webbing whose curtains, formed from two dirty sheets, flapped across a rail of rusty iron, and half a water jug resting against an armchair without stuffing. It was not that Lebrun was financially embarrassed, but he was miserly and devoted to loose-living women.

At Monsieur de Vaudreuil’s classical suppers, he played the role of Pindar. Among his lyric poems, one finds vigorous and elegant verses, as in the ode on the ship Le Vengeur and his ode on Les Environs de Paris. His elegies emerged from his brain, rarely from his soul; he had a studied rather than a natural originality; he only created by virtue of artistic strength; he exercised himself in perverting the sense of words and combining them in monstrous alliances. Lebrun’s only true talent was for satire; his epistle on La bonne et la mauvaise plaisanterie has enjoyed well-merited renown. Some of his epigrams are worthy of comparing with those of Jean-Baptiste Rousseau; Laharpe influenced him particularly. One must also do him the justice to say that he remained independent during Bonaparte’s time, and there are some blood-stained verses of his, written in opposition to that oppressor of our freedoms.

BkIV:Chap12:Sec4

But, without question, the testiest man of letters I met in Paris at that time was Chamfort; suffering from that malady that created the Jacobins, he could not forgive mankind for the misfortune of his origins. He betrayed the trust of the houses to which he was admitted; he took the cynicism of his own language for a portrait of Court morals. One could not quarrel with his being a man of wit and talent, but of that kind of wit and talent that has no impact on posterity. When he realised he was achieving nothing during the Revolution, he turned against himself those hands which he had raised against society. The red cap appeared to his pride to be another sort of crown, sans-culottism a sort of nobility, of which Marat and Robespierre were great lords. Furious at finding inequality of rank even in a world of grief and tears, condemned to being no more than a serf among feudal tormentors, he wished to kill in order to escape from criminal oppression; he bungled his suicide; death mocks those who summon it and who confuse it with nothingness.

I did not meet l’Abbé Delille except in London in 1798, and have not seen Rulhière, who existed thanks to Madame d’Egmont, and who in turn gave her existence, nor Palissot, Beaumarchais, or Marmontel. So it is that I have never met Chénier either, who attacked me frequently, to whom I never responded, and to whose place at the Institute I owe one of the crises of my life.

When I re-read the writers of the eighteenth century, I am amazed at the fame they acquired, and at my old enthusiasms. Whether the language has advanced, or retreated, whether we have marched towards civilisation, or beat a retreat towards barbarism, what is certain is that I find something worn, faded, dull, inanimate, and cold in the authors that were the delight of my youth. I find in even the greatest writers of the age of Voltaire poverty of sentiment, in thought and style.

Who is to blame for my own lapses? I am fearful of having been the guiltiest party: a born innovator, perhaps I have communicated to new generations the malady with which I was infected. Terrified, I have shouted at my children: ‘Do not forget your French!’ They reply as the Limousin did to Pantagruel: ‘that they come from the alma, inclita, and celebrated academy that one vocite Lutetia.’

This mania for Graecizing and Latinizing our language is nothing new, as we see: Rabelais cures it, it reappears in Ronsard; Boileau attacks it. In our time it has been resuscitated by Science; our revolutionaries, noble Greeks by nature, have required our shopkeepers and peasants to understand hectares, hectolitres, kilometres, millimetres, decagrams: politics has been Ronsardised.

I might have spoken here of Monsieur de Laharpe, whom I still know and whom I will return to; I might have added to my portrait gallery that of Fontanes; but though my relationship with that excellent man had its birth in 1789, it was only in England that I forged a friendship with him that has grown with bad fortune, and never diminished with good; I will tell you about him later accompanied by all the outpourings of my heart. I can only describe talents that no longer solace the world. My friend’s death occurred at a moment when my memories were urging me to retrace the commencement of his life. Our existence flies past so swiftly, that if we do not write in the evening the events of the morning, the effort burdens us and we no longer have time to bring them to light. That does not prevent us wasting our lives, scattering to the winds those hours that for mankind are the seeds of eternity.

Book IV: Chapter 13: The Rosanbo family – Monsieur de Malesherbes: his predilection for Lucile – Appearance and transformation of my Sylph

Paris, June 1821.

BkIV:Chap13:Sec1

If my inclination and that of my sisters had launched me into literary society, our position obliged us to frequent another; the family of my brother’s wife was for us, as a matter of course, the centre of that latter grouping.

President Le Pelletier de Rosanbo, who later died with so much courage, was, when I arrived in Paris, a model of flippancy. At that time, everything was disrupted in mind and morals, a symptom of the approaching Revolution. Magistrates were ashamed to wear their robes, and held up to mockery their fathers’ gravity. The Lamoignons, Molés, Séguiers, and d’Aguessaus wished to fight and not to judge. The presidents’ wives, ceasing to be respected mothers of families, left their sombre houses to become women involved in glittering affairs. The priest, in his pulpit, avoided the name of Jesus-Christ and only spoke of the Christian Legislature; ministers fell one after another; power slipped from everyone’s hands. The height of good taste was to be American in town, English at Court, Prussian in the army; anything, except French. What one did, what one said, was no more than a succession of irrelevancies. One claimed to care for the priests who granted benefices, while wanting nothing to do with religion; no one could be an officer if he was not a gentleman, yet one waxed eloquent against the nobility; equality was demonstrated in the salons and beating with sticks in the camps.