François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book III: Adolescence, Combourg 1784-1786

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book III: Chapter 1: Life at Combourg – Days and Evenings

- Book III: Chapter 2: My keep

- Book III: Chapter 3: The passage from childhood to adulthood

- Book III: Chapter 4: Lucile

- Book III: Chapter 5: First breath of the Muse

- Book III: Chapter 6: A manuscript of Lucile’s

- Book III: Chapter 7: The last lines written at the Vallée-aux-Loups – A disclosure concerning my secret life

- Book III: Chapter 8: Phantom of love

- Book III: Chapter 9: Two years delirium – Occupations and dreams

- Book III: Chapter 10: My autumn joys

- Book III: Chapter 11: Incantation

- Book III: Chapter 12: Temptation

- Book III: Chapter 13: Illness – I am afraid and refuse to enter into the ecclesiastical state – A planned passage to India

- Book III: Chapter 14: A moment in my native town – Memory of La Villeneuve and the tribulations of my childhood – I am recalled to Combourg – Last interview with my father – I enter the service -Farewell to Combourg

Book III: Chapter 1: Life at Combourg – Days and Evenings

Montboissier, July 1817. (Revised December 1846)

BkIII:Chap1:Sec1

After my return from Brest, four masters (my father, mother, sister and I) inhabited the château of Combourg. A cook, a chambermaid, two footmen and a coachman comprised the whole domestic staff: a hunting dog and two old mares were hidden away in a corner of the stable. These twelve living beings were swallowed up by a manor house where one might not have noticed a hundred knights, their ladies, squires and varlets, with King Dagobert’s chargers and hounds.

In the course of a year never a stranger presented themselves at the château, except for a few noblemen, such as the Marquis de Montlouet, or the Comte de Goyon-Beaufort, who sought hospitality on their way to plead at the High Court. They arrived in winter, on horseback, pistols at their saddle-bows, hunting-knives at their sides, followed by a man-servant also on horseback, with a big livery trunk behind him.

My father, always very formal, would receive them, bare-headed, on the steps, in the midst of wind and rain. These country gentlemen, once inside, would talk about their Hanoverian campaigns, family affairs and the progress of their law-suits. At night they were shown to the north tower, to Queen Christina’s chamber, a guest room occupied by a seven foot square bed, with two sets of curtains in green muslin and crimson silk, and supported by four gilt Cupids. Next morning, when I descended to the great hall, and looked out of the windows at the countryside, inundated, or blanketed with frost, all I would see were two or three travellers on the lonely road beside the pond: they would be our guests riding towards Rennes.

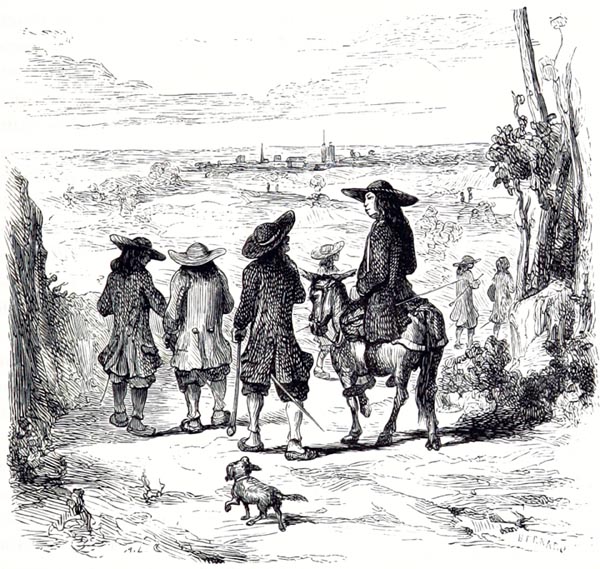

‘Gentilshommes des États’

La Bretagne Ancienne et Moderne. Illustré - Pitre-Chevalier (p499, 1859)

The British Library

These strangers knew little of the affairs of life; nevertheless our view was extended, because of them, for a few miles beyond the horizon of our woods. When they had left we were reduced on weekdays to family conversation, and on Sundays to the society of the village notables and the local gentry.

BkIII:Chap1:Sec2

On Sundays, if the weather was fine, my mother, Lucile, and I went to the parish church through the Little Mall, and along a country lane; when it rained we used the abominable Rue de Combourg. We were not carried, like the Abbé de Marolles, in a light chariot drawn by four white horses, captured from the Turks in Hungary. My father only attended church once a year to perform his Easter duties; for the rest of the year he heard Mass in the chapel of the château. Sitting in the lord of the manor’s pew, we received the incense and prayers in front of the black marble tomb of Renée de Rohan, next to the altar: a symbol of mortal honours; a few grains of incense in front of a sepulchre!

These Sunday entertainments expired with the day: they were not even guaranteed. During the worst of the seasons, whole months passed by without a single human creature knocking on our castle door. If the gloom was great on the heaths round Combourg, it was greater still in the château: one experienced, penetrating its vaults, the same sensation as on entering the Charterhouse at Grenoble. When I visited it in 1805, I traversed a wasteland which was perpetually in growth; I thought it would terminate at the monastery; but they then showed me, within the sacred walls, the gardens of the Charterhouse which were even more overgrown than the woods. Finally, at the centre of the monument, enveloped in the shrouds of all those solitudes, I found the ancient cemetery of the coenobites; a sanctuary where eternal silence, the divinity of the place, extended its power over the mountains and forests around.

The bleak tranquillity of the Château of Combourg was increased by my father’s taciturn and unsociable nature. Instead of gathering his family and servants around him, he had scattered them to every corner of the building. His bedroom was situated in the small east tower, and his study in the small west tower. The furniture in this study consisted of three chairs in black leather, and a table covered with title-deeds and parchments. A genealogical tree of the Chateaubriand family hung over the chimney-piece, and in one window-corner one could see all sorts of fire-arms from pistol to blunderbuss. My mother’s room was above the great hall, between the two small towers: it had a parquet floor and was decorated with faceted Venetian mirrors. My sister occupied a closet adjoining my mother’s room. The chambermaid slept a long way off, in the main building between the two large towers. As for myself, I was tucked away in a sort of isolated cell, at the top of the staircase turret which connected the inner courtyard with the various parts of the château. At the foot of this staircase, my father’s valet and manservant slept in vaulted cellars, while the cook was garrisoned in the great west tower.

BkIII:Chap1:Sec3

My father rose at four in the morning, winter and summer alike: he went into the inner courtyard to call for, and wake, his valet, at the entrance to the turret staircase. A small coffee was brought to him at five: he then worked in his study until midday. My mother and sister each breakfasted in their rooms, at eight. I had no fixed time, for rising or breakfasting; I was supposed to study till noon: most of the time I did nothing.

At half past eleven, the bell rang for dinner which was served at midday. The great hall acted as both dining and drawing room: we dined and supped at one end of the east side; after the meal we went and sat at the other end of the west side, in front of an enormous fireplace. The great hall was wainscoted, painted in pale grey and decorated with old portraits from the reigns of François I to Louis XIV; among the portraits one could make out those of Condé and Turenne: a painting, representing Hector, slain by Achilles beneath the walls of Troy, hung over the chimney-piece.

Dinner over, we stayed together till two. Then, if it was summer, my father entertained himself fishing, inspected his kitchen-gardens, or took a walk ‘to the extent of a capon’s flight’; if it was autumn or winter he went hunting, and my mother retired to the chapel where she spent several hours in prayer. This chapel was a sombre oratory, embellished with fine paintings by the greatest masters, which one hardly expected to find in a feudal castle, in the depths of Brittany. I have in my possession today a Holy Family by Albani, painted on copper, taken from this chapel: it is all that remains to me of Combourg.

Once my father had set out, and my mother was at her prayers, Lucile shut herself in her room; I returned to my cell, or went off to roam the fields.

At eight, the bell rang for supper. After supper, on fine days, we sat out on the steps. My father, armed with a shotgun, fired at the owls that flew from the battlements as night fell. My mother, Lucile, and I, gazed at the sky, the woods, the dying rays of the sun, the first stars. At ten we went in to sleep.

BkIII:Chap1:Sec4

Autumn and winter evenings had a different character. Supper over, and the four diners having moved from table to fire-place, my mother sank, sighing, onto an old day-bed covered with Siam; a little table with a candle was placed before her. I sat near the fire with Lucile; the servants cleared the table and withdrew. My father then set off on a walk which lasted till he retired to bed. He was dressed in a thick white woollen robe, or rather a sort of cloak, that I have never seen on anyone else. His head, which was half-bald, was covered with a big white bonnet which stood upright. When, while walking, he strayed far from the fire-place, the vast hall was so badly lit by a single candle that he could not be seen; he could only be heard walking among the shadows; then he returned slowly towards the light and emerged little by little from the darkness, like a spectre, with his white robe, white bonnet, and long pale face. Lucile and I would exchange a few words in a low voice, while he was at the other end of the hall; we fell silent as he approached us. He would say in passing: ‘What are you talking about?’ Seized by terror we could not reply; he would continue his walk. For the rest of the evening, nothing met the ear but the measured sound of his steps, my mother’s sighs, and the murmur of the wind.

Ten o’clock sounded on the château clock: my father would stop; the same spring which had raised the hammer of the clock seemed to have suspended his steps. He pulled out his watch, wound it, took a large silver candlestick holding a tall candle, went into the small west tower for a moment, then returned, candle in hand, and headed for his bedroom, adjoining the small east tower. Lucile and I stood in his way; we kissed him and wished him goodnight. He offered us his dry, hollow cheek without replying, walked on, and withdrew into the depths of the tower, the doors of which we heard closing behind him.

The spell was broken; my mother, my sister and I, transformed to statues by my father’s presence, recovered the functions of life. The first effect of our disenchantment revealed itself in a torrent of words: if silence had oppressed us, we made it pay dearly.

The flow having ceased, I would call the chambermaid, and escort my mother and sister to their rooms. Before I left, they made me look under the beds, up the chimneys and behind the doors and inspect the stairs, passages and neighbouring corridors. All the traditions of the château, of robbers and ghosts, returned to their thoughts. The servants were convinced that a particular Comte de Combourg, with a wooden leg, three centuries dead, appeared at certain times, and that he had been met with on the great staircase of the turret; and sometimes his wooden leg walked, by itself, accompanied by a black cat.

Book III: Chapter 2: My keep

Montboissier, August 1817.

BkIII:Chap2:Sec1

These stories occupied all the time my mother and sister spent preparing for bed: they climbed into bed dying of fright; I retired to the heights of my turret; the cook returned to the great tower, and the servants descended to their vaults.

The window of my keep opened on the inner court; by day, I had a view of the battlements opposite, where hart’s-tongue ferns flourished and a wild plum-tree grew. The martins which, during the summer, dived with shrill cries into holes in the walls were my sole companions. By night I could only see a little patch of sky and a few stars. When the moon was shining, sinking in the west, I knew it by the rays that shone through the diamond-shaped window panes onto my bed. Screech-owls, gliding from one tower to the other, passed to and fro between the moon and I, casting the moving shadow of their wings on my curtains. Banished to the loneliest corner, at the entrance to the galleries, I did not lose a murmur among the shadows. Sometimes the wind seem to scamper lightly; sometimes it let groans escape; suddenly my door would be shaken violently, the cellars gave out bellowing sounds, then the noises would die away only to commence again. At four in the morning, the voice of the master of the château, calling his valet at the entrance to the ancient vaults, echoed like the voice of night’s last phantom. That voice for me took the place of the sweet harmony of sounds with which Montaigne’s father woke his son.

The Comte de Chateaubriand’s insistence on making a child sleep alone at the top of a tower may have had its inconveniences; but it worked to my advantage. This harsh manner of treating me gave me a manly courage without destroying that liveliness of imagination of which nowadays they try to deprive youth. Instead of trying to convince me that ghosts did not exist, I was forced to confront them. When my father, with an ironic smile, said: ‘Is Monsieur the Chevalier afraid?’ he could have made me sleep with the dead. When my excellent mother said: ‘My child, nothing happens without God’s permission: you have nothing to fear from evil spirits, as long as you are a good Christian’, I was more reassured than by all the arguments of philosophy. My success was so complete that the night winds in my lonely tower, served merely as playthings for my fancies, and wings for my dreams. My imagination was kindled, and spreading to embrace everything, failed to find adequate nourishment anywhere and would have devoured heaven and earth. It is that moral state which I must now describe. Immersed again in my youth, I am going to try and capture my past self, to show myself as I was, such as perhaps I regret no longer being, despite the torments I endured.

Book III: Chapter 3: The passage from childhood to adulthood

BkIII:Chap3:Sec1

I had barely returned from Brest to Combourg than a revolution took place in my existence; the child vanished and the man appeared with all his passing joys and lasting sorrows.

To begin with everything became a passion with me, pending the arrival of the passions themselves. When, after a silent dinner at which I had not dared to speak or eat, I succeeded in escaping, my delight was incredible; I could not descend the staircase with the same breath: I would have flown headlong. I was obliged to sit on a step to allow my excitement to subside; but as soon as I had reached the Green Court and the woods, I began running, jumping, leaping, skipping, gambolling about until I fell down, my strength exhausted, panting, drunk with frolics and freedom.

My father took me with him hunting. A taste for the sport gripped me and I pursued it with fury; I can still see the field where I killed my first hare. In autumn I would often stand up to my waist in water for four or five hours, waiting for wild duck at the edge of a pond; even today, I cannot stay calm when a dog halts and points. However, in my first ardour for the chase, there was a measure of independence; crossing ditches, tramping through fields, marshes, and moors, finding myself with a gun in a deserted spot, possessing strength and solitude, was my way of being close to nature. In my travels, I would stray so far that I could walk no further, and the gamekeepers were obliged to carry me on a litter of branches.

Yet the pleasures of the chase no longer satisfied me; I was stirred by a yearning for happiness, which I could neither control nor understand; my heart and mind ended by forming in me two empty temples, without altars or sacrifices; it was not yet known which god would be worshipped there. I grew up with my sister Lucile; our friendship filled our whole life.

Book III: Chapter 4: Lucile

BkIII:Chap4:Sec1

Lucile was tall and of a remarkable, but grave beauty. Her pale face was framed by long black tresses; she often fixed her gaze on the sky or cast around her looks full of sadness or fire. Her walk, her voice, her smile, her features held something of the dreamer and the sufferer.

Lucile and I were useless to one another. When we spoke of the world, it was of that we bore within ourselves, and which scarcely resembled the real world. She saw me as her protector, I saw her as my friend. She had fits of gloomy thought that I had difficulty in dispelling; at seventeen she mourned the passing of her youth; she wished to bury herself in a convent. To her everything was care; sorrow; suffering: an expression she sought, or a chimera she created, tormented her for months on end. I have often seen her, one arm thrown above her head, dreaming, motionless and inanimate; drawn towards her heart, her life ceased to appear on the surface; even her breast no longer rose and fell. In her attitude, her melancholy, her classical beauty, she resembled a funereal Genius. I would try at those times to console her, and the next moment I would plunge into inexplicable despair.

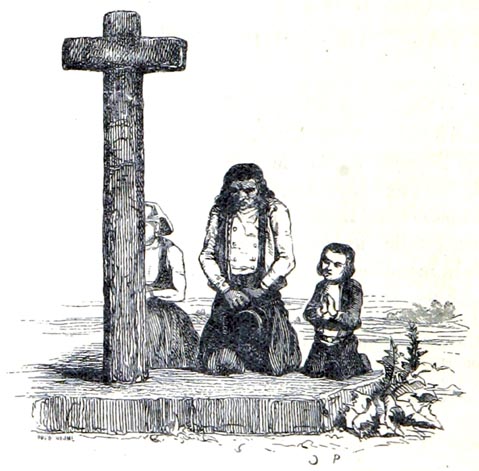

Lucile loved to enjoy some pious text, at evening, in solitude: her favourite oratory was the junction of two country roads, marked by a stone cross, and a poplar whose tall column rose into the sky like an artist’s brush. My devout mother, enchanted, said that her daughter reminded her of a Christian girl of the primitive Church, praying at one of those stations called laures.

La Bretagne Ancienne et Moderne. Illustré - Pitre-Chevalier (p22, 1859)

The British Library

From the concentration of soul in my sister there were born extraordinary spiritual effects: in sleep, she had prophetic dreams; awake, she seemed to read the future. On one of the landings of the staircase in the great tower, there was a clock which struck the hours in the silence; Lucile unable to sleep, would go and sit on a step, facing the clock: she would watch its face by the light of her lamp placed on the ground. When the two hands met at midnight giving birth, at their formidable conjunction, to the hour of crime and disorder, Lucile heard sounds which revealed distant death. Finding herself in Paris a few days before the 10th of August, staying with my other sisters in the neighbourhood of the Carmelite Convent, she cast her eyes on a mirror, gave a cry and said: ‘I have just seen Death enter.’ On the moors of Scotland, Lucile would have been one of Walter Scott’s mystic women, gifted with second sight; on the moors of Brittany, she was only a solitary creature blessed with beauty, genius and misfortune.

Book III: Chapter 5: First breath of the Muse

BkIII:Chap5:Sec1

The life which my sister and I led at Combourg heightened the exaltation natural to our age and character. Our principal distraction consisted of walking side by side in the Great Mall, in spring on a carpet of primroses, in autumn on a bed of dry leaves, in winter on a sheet of snow embroidered with the tracks of birds, squirrels, and stoats. Young as the primroses, sad as the withered leaves, pure as the fresh snow, there was harmony between us and our pastime.

It was during one of these walks that Lucille, listening to me speaking rapturously about solitude, said to me: ‘You ought to write all that down.’ This remark revealed the Muse to me; a divine breath passed over me. I began stammering out verse, as if it had been my native language; day and night I sang of my pleasures, that is to say my woods and valleys; I composed a host of little idylls or portraits of nature. (See my Complete Works. Note: Paris, 1837) I wrote in verse long before writing in prose: Monsieur de Fontanes claimed that I had been equipped with both abilities.

Did this talent promised to me by friendship ever show itself in me? How many things I have waited for in vain! In the Agamemnon of Aeschylus, a slave, posted as sentry on the heights of the palace of Argos; strains his eyes to make out the agreed signal for the return of the fleet; he sings to relieve the tedium of his vigil, but the hours pass, the stars set, and the beacon does not shine. When after many years its tardy flame appears over the waves, the slave is bent beneath the weight of years; nothing remains to him but to reap misfortune, and the Chorus tells him that: ‘an old man is a shadow wandering in the light of day.’ Όναρ ήμερόφαντον νλαίνει.

Book III: Chapter 6: A manuscript of Lucile’s

BkIII:Chap6:Sec1

In the first flush of inspiration, I invited Lucile to imitate me. We spent days in mutual consultation, communicating to each other what we had done, and what we intended to do. We undertook works in common; guided by our instincts, we translated the finest and saddest passages in Job and Lucretius on life: the Taedet animam meam viae meae: my soul is weary of life, the Homo natus de muliere: man that is born of woman, the Tum porro puer, ut saevis projectus ab undis navita: then the new-born, like a seafarer abandoned to the pitiless waves, etc. Lucile’s thoughts were nothing but feelings; they emerged with difficulty from her soul; but when she succeeded in expressing them, they were incomparable. She has left behind some thirty pages in manuscript; it is impossible to read them without being profoundly moved. The elegance, the sweetness, the dreaminess, the passionate sensibility revealed in these pages offers a combination of the Greek genius and the Germanic genius.

‘Dawn

What tender brightness comes to light the East! Is it the young Aurora who half-opens her lovely eyes on the world, full of the languor of sleep! Graceful Goddess, hasten! Leave your nuptial couch, put on your crimson robe; let a soft sash bind you in its knots; let no sandals press your delicate feet; let no adornment profane your lovely hands made to gently open the doors of day. But you have already risen on the shadowy hill. Your golden hair falls in damp tresses on your rosy neck. From your mouth a pure and perfumed breath exhales. Tender deity, all Nature smiles in your presence; you alone shed tears and flowers are born.’

‘To the Moon

Chaste goddess! Goddess, so pure that no blush of shame ever mingles with your tender light, I dare to adopt you as the confidante of my feelings. I have no more reason than you to feel shame in my heart. But often the memory of the injustice and blindness of men veils my brow with cloud, as yours is veiled. Like you, the errors and miseries of this world shape my dreams. But happier than I, citizen of heaven, you always retain your serenity: the storms and tempests that stir our globe glide beneath your tranquil orb. Goddess sympathetic to my sadness set your chill repose on my heart.’

‘Innocence

Daughter of Heaven, sweet innocence, if I dared to attempt a feeble portrait of your nature, I would say that you serve as virtue in childhood, as wisdom in the springtime of life, as beauty in old age, and as happiness in misfortune; that, a stranger to our errors, you only shed pure tears, and that your smile owns nothing that is not celestial. Lovely innocence! How, with danger all around you, desire shapes all its features towards you: do you tremble, modest innocence? Do you seek to hide from the perils that menace you? No, I see you standing there, asleep, your head resting on an altar.’

My brother sometimes granted a few brief moments to the hermits of Combourg: he had the habit of bringing with him a young counsellor at the High Court of Brittany, Monsieur de Malfilâtre, a cousin of the unfortunate poet of that name. I think that Lucile, unknown to herself, had conceived a secret passion for this friend of my brother’s, and that this stifled passion lay at the root of my sister’s melancholy. She was afflicted moreover with Rousseau’s obsession, but without his pride: she believed the whole world was conspiring against her. She travelled to Paris in 1789, accompanied by that sister Julie whose death she had deplored with a tenderness tinged with the sublime. All who knew her admired her, from Monsieur de Malesherbes to Chamfort. Thrown into the Revolution’s crypts at Rennes, she was close to being re-incarcerated in the Château of Combourg, which had been turned into a gaol during the Terror. Released from prison, she married Monsieur de Caud, who left her a widow a year later. On return from my emigration, I was reunited with the friend of my childhood: I will tell you how she vanished, when it pleases God to afflict me.

Book III: Chapter 7: The last lines written at the Vallée-aux-Loups – A disclosure concerning my secret life

Valleé-aux-Loups, November 1817.

BkIII:Chap7:Sec1

Back from Montboissier, these are the last lines I will write in my hermitage: I am forced to leave it, filled with fine striplings which in their serried ranks already hide and crown their father. I will never again see the magnolia which promised its blossom for my girl of Florida’s tomb, the Jerusalem pine and cedar of Lebanon consecrated to the memory of Jerome, the laurel of Grenada, the Greek plane-tree, the Armorican oak, at the foot of which I depicted Blanca, sang of Cymodocée, invented Velléda. These trees were born and grew with my dreams; of which they were the Hamadryads. They are about to pass under another’s power: will their new master love them as I have loved them? He will let them die, or cut them down, perhaps: I can keep nothing on this earth. In bidding farewell to the woods of Aulnay, I will recall the farewell which I bade to the woods of Combourg: all my days are farewells.

BkIII:Chap7:Sec2

The taste for poetry which Lucile inspired in me was like oil thrown onto the fire. My feelings acquired a new degree of strength; vain ideas of fame passed through my mind; for a moment I believed in my talent, but soon recovering a proper mistrust of myself, I began to doubt that talent, as I have always doubted it. I regarded my work as an evil temptation; I was angry with Lucile for engendering in me an unfortunate tendency: I stopped writing, and began to mourn my future glory, as one mourns a glory that has gone.

Returning to my former idleness, I became more aware of what my youth lacked: I was a mystery to myself. I could not look at a woman without being stirred; I blushed if she addressed a word to me. My shyness, already excessive with everyone, was so great with a woman that I would have preferred any torment to being left alone with that woman: she was no sooner gone than to recall her was my deepest wish. The portraits drawn by Virgil, Tibullus, and Masillon, presented themselves to my memory of course; but the images of my mother and sister, covering everything with their purity, made those veils denser which nature tried to lift; filial and brotherly tenderness deceived me as to any less disinterested tenderness. If the loveliest slaves of the seraglio had been handed over to me, I would not have known what to ask of them: chance enlightened me.

A neighbour of the Combourg estate came to spend a few days in the château with his very pretty wife. Something occurred in the village; everyone ran to the windows of the great hall to see. I arrived first; our fair guest was hard on my heels, and wishing to yield her my place I turned towards her: she involuntarily blocked my way, and I felt myself pressed between her and the window. I no longer knew what was happening around me.

At that moment, I became aware that to love and be loved in a manner as yet unknown to me, must be the supreme happiness. If I had done what other men do, I would have soon have learnt of the pains and pleasures of that passion whose seeds I carried; but everything in me took on an extraordinary character. The ardour of my imagination, my shyness, and my solitariness were such that instead of going abroad I fell back upon myself; lacking a real object of love, I evoked, through the power of my vague longings a phantom which never left me. I do not know if the history of the human heart offers another example of this kind.

Book III: Chapter 8: Phantom of love

BkIII:Chap8:Sec1

Thus I imagined a woman derived from all the women I had seen: she had the figure, the hair and the smile of the guest who had pressed me against her breast; I gave her the eyes of one young girl from the village, the complexion of another. The portraits of great ladies of the age of François I, Henri IV, and Louis XIV, with which the drawing-room was decorated, furnished me with other characteristics, and I stole certain graces from the pictures of the Virgin hung in church.

This invisible charmer followed me everywhere; I talked to her as if she was a real person; she varied according to my mood: Aphrodite without a veil, Diana clothed in dew and air, Thalia with her laughing mask, Hebe with the cup of youth, she often became a fairy who subjected Nature to my control. I retouched my canvas, endlessly; I took one grace from my beauty to replace it with another. I also changed her finery; I borrowed from every country, every age, every art; every religion. Then, when I had created a masterpiece, I dispersed my lines and colours once more; my unique woman was transformed into a multitude of women, in whom I idolised separately the charms I had adored in unison.

Pygmalion was less enamoured of his statue: my problem was how to please mine. Not recognising in myself any of the qualities that inspire love, I lavished upon myself all that I lacked. I sat a horse like Castor or Pollux, I played the lyre like Apollo; Mars wielded his arms with less strength and skill: a hero of history or romance, what fictitious adventures I heaped upon those fictions! The shades of Morven’s daughters, the Sultans of Baghdad and Granada, the ladies of ancient manor houses; baths, perfumes, dances, Asiatic delights, were all appropriated by me with a magic wand.

A young queen would come to me, decked in diamonds and flowers (it was always my sylph); she sought me at midnight, through gardens filled with orange-trees, in the galleries of a palace washed by the sea’s waves, on the balmy shores of Naples or Messina, under a sky of love that Endymion’s star bathed with its light; she walked, a living statue by Praxiteles, among motionless statues, pale pictures, and silent frescoes whitened by the moon’s rays: the soft sound of her movement over the marble mosaic mingled with the imperceptible murmur of the waves. Royal jealousy surrounded us. I fell at the knees of the sovereign of Enna’s plain; the silken tresses loosed from her diadem caressed my brow, as she bent her sixteen-year old head over my face, and her hands rested on my breast, throbbing with respect and desire.

‘Luxe Français en Bretagne’

La Bretagne Ancienne et Moderne. Illustré - Pitre-Chevalier (p527, 1859)

The British Library

Emerging from these dreams, finding myself again a poor obscure little Breton, without fame, beauty, or talent, who would attract no one’s attention, who would go unnoticed, whom no woman would ever love, despair seized me: I no longer dared lift my eyes to the dazzling image I had conjured to my side.

Book III: Chapter 9: Two years delirium – Occupations and dreams

BkIII:Chap9:Sec1

This delirium lasted two whole years, during which my mental faculties reached the highest pitch of exaltation. I used to speak little, I no longer spoke at all; I still studied, but tossed aside my books; my taste for solitude intensified. I possessed all the symptoms of violent passion; my eyes grew hollow; I grew thin; I no longer slept; I was distracted, sad, ardent, and unsociable. My days rolled by in a manner that was wild, strange, insensate, maddened, and yet full of delight.

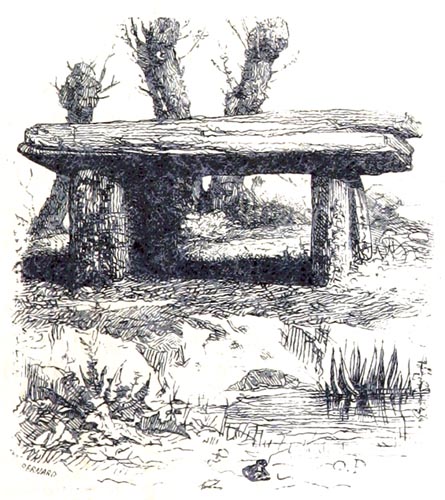

To the north of the château extended a terrain dotted with Druidic stones; I would go and sit on one of these stones at sunset. The golden summit of the wood, the splendour of the earth, the evening star glittering among the rose-coloured clouds, sent me back to my dreams: I would have wished to enjoy the spectacle with the ideal object of my yearnings. I followed the star of day in thought; I gave him my beauty to lead along, so that he might present her, radiant beside him, to the universal homage. The evening breeze which stirred the web woven by a spider between the grass-tips, the moor-land lark settling on a stone, called me back to reality: I made my way back home, heart constricted, face lowered.

La Bretagne Ancienne et Moderne. Illustré - Pitre-Chevalier (p27, 1859)

The British Library

On stormy days in summer, I would climb to the top of the great west tower. The rumble of thunder in the garrets of the chateau, the torrents of rain that pounded down on the cone-shaped roofs of the towers, and the lightning furrowing the clouds and marking out the brass weathercocks with electric flame, excited my enthusiasm: like Ismen on the ramparts of Jerusalem, I invoked the thunder; I hoped it might bring me Armida.

Was the sky clear? I crossed the Great Mall, around which lay meadows separated by hedges of willow-trees. I had made a seat, like a nest, in one of these willows: there, alone between heaven and earth, I spent hours with the warblers; my nymph was at my side. I associated her image equally with the beauty of those spring nights filled with the freshness of dew, with the plaints of the nightingale, and the murmur of the breeze.

At other times, I would follow an abandoned track, or a stream adorned with its water-plants; I listened to the sounds that emanate from unfrequented places; I put my ear to every tree; I thought I might hear the moonlight singing in the woods: I wanted to tell of these pleasures and words died on my lips. I do not know how often I rediscovered my goddess in the tones of a voice, the tremors of a harp, in the velvet or liquid sounds of a horn or an organ. It would take too long to tell of the lovely voyages I made with my flower of love; how hand in hand we visited famous ruins, Venice, Rome, Athens, Jerusalem, Memphis, Carthage; how we crossed the seas; how we demanded happiness from the palm-trees of Tahiti, from the balm-filled groves of Ambon and Timor; how we went to wake the dawn on a summit of the Himalayas; how we descended the sacred rivers whose waves extended round pagodas with golden domes; how we slept on the banks of the Ganges, while the Bengali, perched on the mast of a bamboo craft, sang his Indian barcarole.

Heaven and earth no longer meant anything to me; I forgot the former especially: but if I no longer addressed my prayers to it, it heard the voice of my secret misery, since I suffered, and suffering is prayer.

Book III: Chapter 10: My autumn joys

BkIII:Chap10:Sec1

The sadder the season, the more it matched my mood: cold weather, by making travel less easy, isolated the inhabitants of the countryside: one felt better in human shelter.

A moral character is attached to autumn scenes: those leaves which fall like our years, those flowers which fade like our hours, those clouds that flee like our illusions, that light which weakens like our intellect, that sun which cools like our love, those waves that freeze like our life, have a secret sympathy with our destiny.

I viewed with inexpressible pleasure the return of the stormy season, the flight of swans and wood-pigeons, the gathering of rooks on the meadow by the pond, and their perching at the fall of night on the highest oaks of the Great Mall. When evening raised a bluish mist at crossroads in the forests, when the moans or whistles of the wind wailed in the withered mosses, I entered into complete ownership of my natural sympathies. Did I meet with some labourer in the depths of a fallow field? I would stop to look at that man engendered in the shade of those ears of corn among which he must be harvested, and who turning the earth of his tomb with the blade of the plough mingled his hot sweat with the cold rains of autumn: the furrow he dug was the monument destined to survive him. What had my elegant daemon to do with that? Through her magic, she transported me to the banks of the Nile, showed me the Pyramids of Egypt buried in sand, as one day the Armorican furrow would be hidden by heather: I congratulated myself on having set my fables of happiness beyond the circle of mortal realities.

In the evening I embarked on the pond, steering my boat alone, in the midst of bulrushes and the large floating water-lily leaves. There, the swallows gathered again preparing to leave our climes. I did not lose a single note of their twittering: Tavernier as a child would have been less attentive to a traveller’s tale. They played above the water at sunset, chasing insects, hurling themselves together through the air, as if to test their wings, fell towards the surface of the lake, then came and hung on the reeds that their weight scarcely bent down, and which they filled with their confused song.

Book III: Chapter 11: Incantation

BkIII:Chap11:Sec1

Night fell: the reeds agitated their fields of distaffs and two-edged swords, among which the feathered caravan, moorhens, teal, kingfishers, and snipe fell silent; the lake beat at its margins; autumn’s great voice rose from the marshes and woods: I moored my boat on the shore, and returned to the château. Ten o’clock sounded. Scarcely having retired to my room, opening my windows, and fixing my gaze on the sky, I would begin an incantation. I mounted with my sorceress towards the clouds: tangled in their nets and tresses, I would travel, as the storms willed, stirring the tops of the forests, shaking the mountain summits, or whirling above the seas. Plunging through space, descending from the throne of God to the gates of the abyss, worlds were delivered up to the force of my passion. In the midst of the elemental chaos, I drunkenly married the sense of danger with that of pleasure. The breath of the north wind only brought me the sighs of sensual delight; the murmur of the rain invited me to slumber on a woman’s breast. The words I addressed to that woman would have given old age back its senses, and warmed marble tombs. Ignorant of all, knowing all, at once virgin and lover, innocent Eve, and fallen Eve, the enchantress through whom my madness arose was a blend of mysteries and passions: I set her on an altar and adored her. The pride of being loved by her increased my love still more. Did she walk? I prostrated myself to be trodden by her feet. I was flustered by her smile; I trembled at the sound of her voice; I quivered with desire, if I touched what she had touched. The air, exhaled from her moist mouth, penetrated the marrow of my bones, flowed in my veins instead of blood. A single one of her looks sent me flying to the ends of the earth; what desert would not have sufficed for me, with her there!! By her side, the lions’ den had become a palace, and millions of centuries would have been too short to exhaust the fires by which I felt myself inflamed.

To this fury a moral idolatry was joined: through another quirk of my imagination, that Phryne, who clasped me in her arms, was also to me glory, and above all honour; the virtue with which she achieved her noblest sacrifices, the genius with which it gave birth to the rarest thought, would scarcely yield an idea of that other kind of happiness. In my marvellous creation I found at the same moment all the delights of the senses and all the pleasures of the soul. Overwhelmed, as if submerged, by this double joy, I no longer knew what my true existence was; I was human and not human; I became cloud, wind, sound; I was a pure spirit, an aerial being, singing sovereign happiness. I stripped myself of my nature to merge with the daughter of my desires, to transform myself into her, to touch beauty most intimately, to be at the same moment passion given and received, love and the object of love.

Suddenly, struck by my madness, I flung myself on my couch; I rolled about with grief; I drenched my bed with bitter tears which no one saw and which flowed pitifully, for one who did not exist.

Book III: Chapter 12: Temptation

BkIII:Chap12:Sec1

Soon, unable to rest in my tower, I descended through the shadows, opened the stairway door furtively like a murderer, and went off to wander in the great wood.

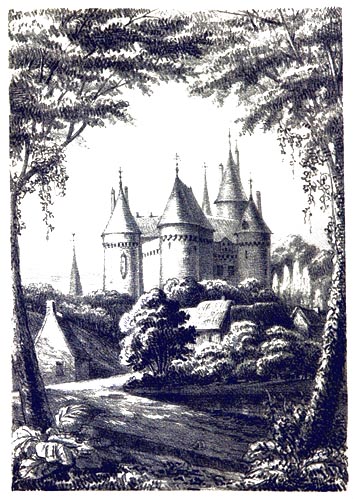

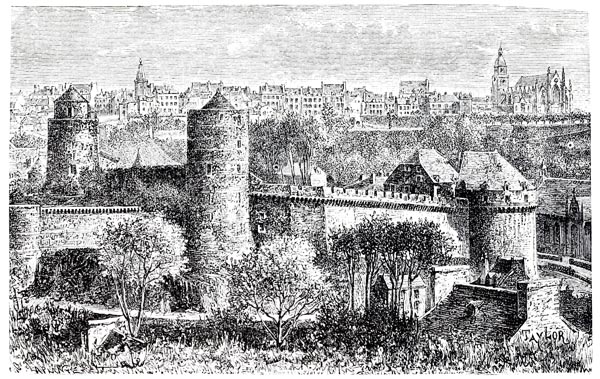

‘Combourg’

La Bretagne Catholique. Description Historique et Pittoresque - Léon Louis Buron, A. Devaux (p12, 1856)

The British Library

Having marched towards adventure, throwing my arms about, grasping the breezes that escaped me like the shade that was the object of my pursuit, I leant against the trunk of a beech-tree: I watched the crows that I forced to fly from one tree to settle on another, or the moon moving through the naked heights of the plantation: I should have liked to inhabit that dead world, which mirrored the pallor of a sepulchre. I felt neither the chill, nor the moisture of the night; not even dawn’s glacial breath would have dragged me from my thoughts, if the village clock had not made itself heard at that moment.

In most of the villages of Brittany, it is usual to ring the chimes for the dead at daybreak. This peal, of three repeated notes, creates a little monotonous air, rural and melancholy. Nothing was better suited to my sick and wounded soul, than to be returned to the tribulations of existence by the bell which announced its end. I pictured to myself the shepherd expiring in his un-regarded hut, then buried in a cemetery no less unknown. What had he achieved on this earth? What had I myself done in this world? Since I must vanish at last, would it not be better to depart in the freshness of morning, and arrive in good time, than make the voyage under the burden and in the heat of the day? The blush of desire mounted to my face; the idea of no longer being seized my heart in the manner of a sudden joy. In my times of youthful error, I had often wished not to survive happiness: there is in first success a degree of felicity that made me long for destruction.

Bound ever more tightly to my phantom, unable to enjoy what did not exist, I was like those mutilated men who dream of bliss unattainable by them, and who conjure a dream whose pleasures equal the torments of hell. Moreover I had a presentiment of the wretchedness of my future fate: ingenious in contriving suffering for myself, I had placed myself between two sources of despair; sometimes I considered myself no more than a cipher, incapable of rising above the common herd; sometimes I seemed to detect in myself qualities which would never be appreciated. A secret instinct warned me that in making my way in the world I would find nothing of what I sought.

Everything nourished the bitterness of my self-disgust: Lucile was unhappy; my mother did not console me; my father made me aware of the horrors of life. His gloominess increased with the years; age stiffened his soul as it did his body; he spied on me ceaselessly in order to reprimand me. When I returned from my wild excursions and saw him sitting on the steps, I would rather have died than enter the château. But this would only serve to delay my torture: obliged to appear at supper, I would sit guiltily on the edge of my chair, my cheeks wet with rain, my hair tangled. Under my father’s gaze, I sat motionless with sweat bathing my brow: the last glimmer of reason left me.

BkIII:Chap12:Sec2

Now I come to a moment when I need strength to confess my weakness. The man who attempts his own life shows the feebleness of his character rather than the power of his soul.

I owned a hunting rifle whose worn trigger often fired when un-cocked. I charged this gun with three bullets, and went to a remote part of the Great Mall. I cocked the weapon, placed the muzzle in my mouth, and struck the butt on the ground: I repeated the attempt several times: the gun did not fire; the appearance of a gamekeeper altered my resolution. An unconscious and involuntary fatalist, I concluded my hour had not yet come, and I deferred the execution of my plan to another day. If I had killed myself, all I have achieved would have been buried with me; nothing would have been known of the tale which led to my catastrophe; I would have swelled the crowd of nameless unfortunates, I would not have induced anyone to follow the trail of my sorrows, as a wounded man leaves a trail of blood.

Those who might be troubled by these scenes, and be tempted to imitate these follies, those who might attach themselves to my memory by means of my illusions, must remember that they hear only a dead man’s voice. Reader, whom I shall never know, nothing remains: nothing is left of me but that which I am in the hands of the living God who has judged me.

Book III: Chapter 13: Illness – I am afraid and refuse to enter into the ecclesiastical state – A planned passage to India

BkIII:Chap13:Sec1

An illness, the fruit of this disordered life, put an end to the torments through which the first inspirations of the Muse and the first assault of the passions touched me. These passions which taxed my spirit, these passions as yet ill-defined, resembled storms at sea that rush on from every point of the compass: a pilot lacking experience, I did not know how to trim my sail to the uncertain breeze. My chest swelled, fever seized me; they sent for an excellent doctor, named Cheftel, whose son played a role in the Marquis de la Rouërie affair, from Bazouches, a little town fifteen or so miles from Combourg (As I advance in life I meet again people from my Memoirs: The widow of Doctor Cheftel’s son came to me to apply for entry into the Marie-Thérèse Infirmary: one more witness to my veracity. Note: Paris, 1834). He examined me carefully, prescribed certain remedies and declared that above all it was necessary to remove me from my current mode of life.

I was in danger for six weeks. One morning my mother came and sat on my bed, and said: ‘It is time for you to decide; your brother is able to obtain a benefice for you; but before you enter the seminary you must think about it carefully, for though I desire you to embrace the ecclesiastical state, I would rather see you a man of the world than a scandalous priest.’

Having read this, one can judge whether my pious mother’s suggestion came at a timely moment. In the major events of my life, I have always known immediately what to evade: a sense of honour prompts me. An abbé? I would consider myself ridiculous. A bishop? The majesty of my office would overawe me and I would respectfully recoil from the altar. As a bishop should I make an effort to acquire virtue, or content myself with concealing my vices? I felt too weak to play the first part, too honest for the second. Those who call me hypocritical and ambitious know little of me: I shall never succeed in the world, precisely because I lack a passion and a vice, ambition and hypocrisy. At most the first would be, in me, wounded self-esteem; I might sometimes desire to be minister or king so as to mock my enemies; but after twenty-four hours I would throw my portfolio or crown out of the window.

So I told my mother that my calling to the ecclesiastical state was not strong enough. I was altering my plans for the second time: I had not wished to become a sailor; I no longer wished to be a priest. A military career remained; I liked the idea: but how would I tolerate the loss of my independence and the constraints of European discipline? A ridiculous idea entered my head: I declared I would go to Canada to clear forests, or to India to take service in the army of one of that country’s princes.

By one of those contrasts that one remarks in all men, my father, so prudent normally, was never greatly shocked by an adventurous project. He complained to my mother about my changeableness, but he decided to support my passage to India. I was sent to Saint-Malo; they were fitting out a vessel for Pondicherry.

Book III: Chapter 14: A moment in my native town – Memory of La Villeneuve and the tribulations of my childhood – I am recalled to Combourg – Last interview with my father – I enter the service -Farewell to Combourg

BkIII:Chap14:Sec1

Two months rolled by: I found myself alone again in my native isle; La Villeneuve had just died there. On going to weep for her beside the poor empty bed where she had expired, I noticed the little wicker go-cart in which I had learned to stand upright on this sad globe. I pictured my old nurse, fixing her feeble gaze on that wheeled basket at the foot of her bed: this first memorial of my life facing the last memorial of the life of my second mother, the thought of the prayers for her charge that dear Villeneuve addressed to heaven on leaving this world, that proof of an attachment so constant, so disinterested, so pure, moved my heart with tenderness, regret, and gratitude.

There was nothing else of my past in Saint-Malo: I searched the harbour in vain for the boats in whose rigging I had played; they had gone or been dismantled; in the town the house where I had been born had been transformed into an inn. I had scarcely left my cradle and already a whole world had vanished. A stranger in my childhood haunts, those who met me asked who I was, for the sole reason that my head had had risen a few inches higher from the ground towards which it will bow again in a few years. How swiftly and how frequently we change our existence and our illusions! Friends leave us, others take their place; our relationships alter: there is always a time when we possessed nothing of what we possess, and a time when we have nothing of what we had. Man does not have a single, consistent life; he has several laid end to end, and that is his misfortune.

BkIII:Chap14:Sec2

Now without a companion, I explored the arena that once saw my castles of sand: campos ubi Troia fuit: the fields where Troy once stood. I walked along the empty sea-shore. The beaches abandoned by the tide offered me the image of desolate spaces that illusions leave around us when they fade. My compatriot Abelard gazed at the waves as I did, eight hundred years ago, remembering Héloïse; as I did he watched the vessels flee (ad horizontis undas: to the horizon’s waters) and his ear was lulled like mine by the harmony of the waves. I exposed myself to the breakers while giving myself up to the gloomy fancies that I had brought from the woods of Combourg. A headland, named Lavarde, put an end to my wanderings: sitting on the point of this headland, lost in the bitterest thoughts, I remembered that these same rocks had served to hide me in my childhood, at times of festivity; I swallowed my tears there, while my friends were drunk with joy. I felt myself no more loved or happy now. Soon I would leave my homeland to eke out my days in varied climes. These thoughts sickened me to death, and I was tempted to throw myself into the waves.

A letter recalled me to Combourg: I arrived, I supped with my family; my father did not utter a word, my mother sighed, Lucile looked dismayed; at ten we retired to bed. I questioned my sister; she knew nothing. Next morning at eight I was sent for. I descended: my father was waiting for me in his study.

‘Monsieur le Chevalier,’ he said to me: ‘you must renounce your follies. Your brother has obtained a second-lieutenant’s commission for you in the Navarre Regiment. You are to go to Rennes and from there to Cambrai. Here are a hundred louis; be careful with them. I am old and ill; I have not long to live. Conduct yourself like a man of honour, and never disgrace your name.’

He kissed me. I felt that stern and wrinkled face press tenderly against mine: it was the last paternal embrace I received.

The Comte de Chateaubriand, a man so formidable in my eyes, appeared at that moment simply as a father completely worthy of my affection. I seized his emaciated hand and wept. He was beginning to suffer from paralysis; it brought him to his grave. His left hand would jerk convulsively and he was obliged to restrain it with his right. It was holding his arm in this way, and having handed me his old sword, that without giving me time to recover, he led me to the cabriolet which was waiting for me in the Green Court. He made me get up, in front of him. The postilion drove off, while I said farewell with my eyes to my mother and sister, dissolved in tears on the steps.

I drove along the causeway by the pond; I saw the reeds inhabited by my swallows, the mill-stream and the meadow; I cast a look at the château. Then, like Adam after sinning, I went out into an unknown land: ‘and the world was all before him’.

BkIII:Chap14:Sec3

Since that day, I have only seen Combourg three times: after my father’s death, we all met there in mourning, to divide our inheritance and say adieu. On another occasion I accompanied my mother to Combourg; she was concerned with furnishing the chateau; she expected my brother there, who was bringing my sister-in-law to Brittany. My brother never arrived; with his young wife, he was soon to receive, at the executioner’s hands, a different support for his head than the pillow my mother’s hands had prepared. Finally, I passed through Combourg a third time, on the way to Saint-Malo to embark for America. The château was deserted; I was obliged to go down to the steward’s lodge. When, wandering down the Great Mall, I saw, at the end of a dark alley, the empty steps, the closed doors and windows, I felt ill. With difficulty, I made my way back to the village; I sent for my horses, and left in the middle of the night.

After fifteen years absence, before leaving France again to travel to the Holy Land, I went to Fougères to embrace what was left of my family. I had not the heart to make a pilgrimage to the fields with which the most vital part of my existence is connected. It was in the woods of Combourg that I became what I am, that I began to feel the first assault of that ennui which I have dragged with me through life, of that sadness which has been my torment and my bliss. There, I searched for a heart that could understand mine; there, I saw my family reunite, then disperse. My father dreamt there of seeing his name re-established, the fortunes of his house revived: another illusion which time and revolution have dispelled. Of the six children we were, there are now only three: my brother, Julie and Lucile are no more, my mother has died of grief; my father’s ashes have been snatched from his grave.

‘Fougères’

Géographie du Département d'Ille-et-Vilaine - Adolphe Laurent Joanne (p52, 1881)

Internet Archive Book Images

If my works survive me, if I am to leave a name behind, perhaps one day, guided by these Memoirs, some traveller will visit the places I have described. He might recognise the château; but he would search in vain for the great wood: the cradle of my dreams has vanished like those dreams. Left standing alone on its rock, the ancient keep mourns the oaks, old companions which surrounded it, and protected it against the tempest. Solitary, like that keep, I too have seen the family that adorned my days and lent me its shelter fall around me: happily my life is not founded on earth as solidly as those towers where I spent my youth, and man resists the storm less strongly than the monuments raised by his hands.

End of Book III