François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book II: Boyhood 1777-1784

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book II: Chapter 1: The School at Dol – Mathematics and Languages – The nature of my memory

- Book II: Chapter 2: Holidays at Combourg – Life in a provincial château – Feudal customs – The inhabitants of Combourg

- Book II: Chapter 3: Holidays again at Combourg – The Conti Regiment – Camp at Saint-Malo – An Abbey – The Theatre – My two eldest sisters’ marriages – Return to school – A revolution begins in my ideas

- Book II: Chapter 4: The adventure of the magpie – Three holidays at Combourg – The charlatan – Return to school

- Book II: Chapter 5: Invasion of France – Games – The Abbé de Chateaubriand

- Book II: Chapter 6: First Communion – I leave Dol College

- Book II: Chapter 7: Mission at Combourg – Rennes College – I meet Gesril again – Moreau – Limoëlan – My third sister’s marriage

- Book II: Chapter 8: I am sent to Brest to take the Navy examination – The Port of Brest – I meet Gesril again – La Pérouse – I return to Combourg

- Book II: Chapter 9: A Walk – The Ghost of Combourg

- Book II: Chapter 10: College at Dinan – Broussais – I return to my parents’ house

Book II: Chapter 1: The School at Dol – Mathematics and Languages – The nature of my memory

Dieppe, September 1812. (Revised June 1846)

BkII:Chap1:Sec1

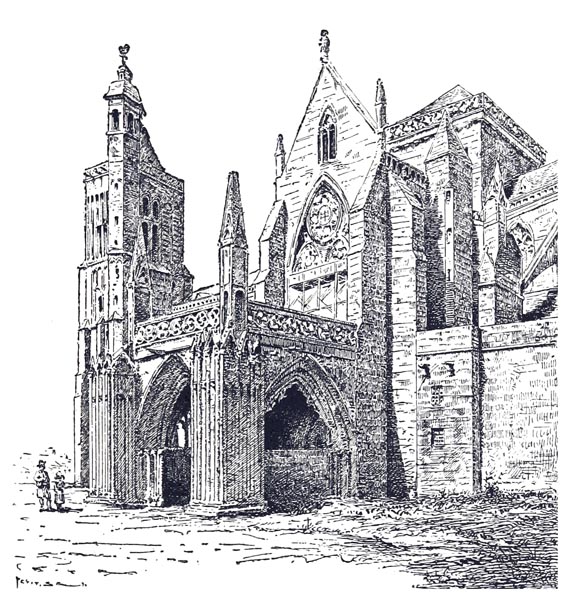

I was not a complete stranger to Dol; my father was canon there, as the descendant and representative of the house of Guillaume de Chateaubriand Sire de Beaufort, founder in 1529 of one of the first stalls in the cathedral choir. The Bishop of Dol was Monsieur de Hercé, a friend of my family, a prelate of very moderate political views, who kneeling, with crucifix in hand, was shot with his brother the Abbé de Hercé, at Quiberon, on the Field of Martyrdom. Arriving at the school, I was entrusted to the special care of Monsieur l’Abbé Leprince, who taught rhetoric and had a profound knowledge of geometry: he was a witty and handsome man, a lover of the arts, who could paint excellent portraits. He undertook to teach me my Bezout; the Abbé Égault, master of the fourth years, became my Latin master; I studied mathematics in my own room, Latin in the schoolroom.

‘Porche de la Cathédrale de Dol’

Zig-Zags en Bretagne, etc. Illustré - H. Dubouchet (p65, 1894)

The British Library

It took some time for an owl of my species to accustom itself to the cage represented by a school, and regulate its flight by the sound of a bell. I could not win the ready friends that wealth provides, since there was nothing to be gained from a poor wretch without even a weekly allowance; nor did I join any kind of clique, since I hate protectors. At games, I did not try to lead others, but I would not be led: I was not suited to be a tyrant or a slave, and so I have remained.

Nevertheless as it happened I quite quickly became the centre of a set; I exerted the same influence, later, in my regiment: simple ensign that I was, senior officers spent their evenings with me and preferred my rooms to the mess. I don’t know why this was, unless perhaps it stemmed from my ability to enter into the spirit and adopt the manners of others. I enjoyed hunting and running as much as reading and writing. It is still a matter of indifference to me whether I talk about the most ordinary matters or speak on the most elevated of subjects. Being insensitive to wit, it is almost antipathetic to me, though I am no boor. No failings shock me, except ridicule and conceit, which I find it hard not to attack; I find that others always have some superiority over me, and if by chance I sense an advantage, I am dreadfully embarrassed by it.

Qualities that my early education had left dormant awoke in me at school. My aptitude for work was remarkable, my memory extraordinary. I made rapid progress in mathematics to which I brought a clearness of thought that astonished the Abbé Leprince. At the same time I showed a decided bent for languages. The rudiments, the torment of schoolboys, cost me nothing to acquire; I waited for the Latin lessons with a kind of impatience, as a relaxation after my calculations and geometry diagrams. In less than a year I reached good second form standard. For some strange reason, my Latin phrases fell so naturally into pentameters that the Abbé Égault called me the Elegist, a name which stuck to me among my schoolmates.

BkII:Chap1:Sec2

As to my memory, two traits were visible. I learnt logarithm tables by heart: that is to say when a number was given in a geometric series I discovered from memory its exponent in the corresponding arithmetic series, and vice versa.

After evening prayers which were offered communally in the college chapel, the Principal gave his lecture. One pupil, chosen at random, was obliged to reply. We arrived at prayers tired from our games and dying to sleep; we threw ourselves onto the benches, trying to squeeze ourselves into a dark corner, in order not to be seen and consequently questioned. Above all there was a confessional that we fought over as a perfect retreat. One evening, I had the good luck to gain this refuge and considered myself safe from the Principal; unfortunately, he spotted my manoeuvre and decided to make an example of me. He elaborated on the second point of a sermon, slowly and lengthily; everyone slept. I don’t know what chance led me to stay awake in my confessional. The Principal, who could only see the soles of my feet, thought I was taking my ease like the rest, and suddenly apostrophizing me, asked me what he had been saying.

The second point of the sermon contained an enumeration of the various ways in which one might offend God. I not only repeated the essence of the thing, but I recounted the divisions in order, and repeated several pages of mystical prose, unintelligible to a child, almost word for word. A murmur of applause filled the chapel: the Principal called me, gave me a little pat on the cheek, and allowed me, as a reward, to stay in bed the following day till lunchtime. I evaded, modestly, the admiration of my schoolmates and profited fully from the grace accorded me. This memory for words, which has not wholly stayed with me, has given way to another kind of memory, more remarkable, of which I may perhaps have the opportunity to speak.

One thing humbles me: memory is often a facet of stupidity; it generally reveals itself in dull souls, making them heavier from the load with which it burdens them. Nevertheless, without memory, what would we be? We would forget our friendships, our loves, our pleasures, our business affairs; the genius could never collect his thoughts; the most affectionate heart would lose its tenderness, if it could not remember; our existence would reduce to the successive moments of a present which flowed by without cease; there would be no more past. O wretchedness that is ours! Our life is so trivial that it is no more than a reflection of our memory.

Book II: Chapter 2: Holidays at Combourg – Life in a provincial château – Feudal customs – The inhabitants of Combourg

Dieppe, October 1812.

BkII:Chap2:Sec1

I went to Combourg for the duration of the holidays. Life in a château near Paris can give no idea of life in a château in a provincial backwater.

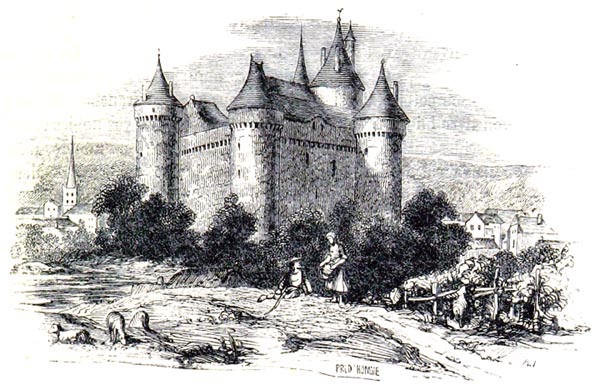

The estate of Combourg had for its whole domain only some heath land, a few mills, and two forests, Bourgouët and Tanoërn, in a part of the country where timber is almost valueless; but it was rich in feudal rights; these rights were of various kinds: some determined certain rents for certain concessions, or enshrined practices born of the old political order; others seemed to have had their origin only in amusements.

‘Château de Combourg’

La Bretagne Ancienne et Moderne. Illustré - Pitre-Chevalier (p17, 1859)

The British Library

My father had revived some of these latter rights, in order to prevent their prescription. When all the family were gathered together, we took part in these medieval pleasures: the three principal ones were the Saut des poissonniers, the Quintaine, and the fair called the Angevine. Peasants in clogs and laced breeches, men of a France that is no more, watched those games of a France that was already no more. There was a prize for the victor, a forfeit for the vanquished.

The Quintaine preserved the tradition of the tournament: it surely had some connection with the ancient military duties of the fiefs. It is well described in Du Cange (Voce, Quintana). Forfeits had to be paid in old copper coinage to the value of two moutons d’or à la coronne of 25 Parisian sols each.

The fair known as the Angevine was held in the Pond Meadow, on the 4th of September each year, my birthday. The vassals were obliged to take up arms, and came to the château to raise the banner of their lord; from there they went to the fair to keep order, and to enforce the collection of a toll due to the Counts of Combourg on every head of cattle, a sort of royalty. During that time my father kept open house. There was dancing for three days: by the masters in the grand hall to the scraping of a violin; for the vassals in the Green Court to the nasal whine of a bagpipe. They sang, cheered, and fired arquebusades. These noises mingled with the lowing of cattle at the fair; the crowds wandered through the gardens and the woods, and at least once a year Combourg saw something resembling joy.

So I enjoyed the singular distinction in life of having assisted at the races of the Quintaine and at the proclamation of the Rights of Man; of having viewed the bourgeois militia of a Breton village and the National Guard of France, the banner of the Lords of Combourg, and the flag of the Revolution. It is as if I were the last witness to feudal custom.

BkII:Chap2:Sec2

The visitors who were received at the château comprised the leading inhabitants of the village, and the local nobility: these good people were my first friends. Our vanity sets too much importance on the role we play in the world. The Parisian bourgeoisie laugh at the bourgeoisie from a small town; the Court nobility mock the provincial nobility: the famous man scorns one who is unknown, without reflecting that time serves equal justice on their pretensions, and that they are all equally ridiculous or tedious in the eyes of succeeding generations.

The most important local inhabitant was a Monsieur Potelet, a retired sea-captain of the India Company who recalled tall tales of Pondicherry. As he told them with his elbows on the table my father always wished to throw his plate in his face. After him came the tobacco bonder, Monsieur Launay de La Billardière, the father, like Jacob, of a family of twelve children, in his case nine girls and three boys, of whom the youngest, David, was a playmate of mine. This good man took it into his head to become a nobleman in 1789: he had left it rather late! In his household there was a good deal of happiness and plenty of debt. The seneschal Gébert, the fiscal attorney Petit, the tax-collector Le Corvaisier, and the chaplain the Abbé Charmel, completed Combourg society. I have met no-one more distinguished since in Athens.

Messieurs du Petit-Bois, de Chateau-d’Assie, de Tinténiac, and one or two other gentlemen, would come, on Sunday, to hear mass in the parish, and to dine afterwards with the lord of the manor. We were especially close to the Trémaudan family, comprising the husband, his very pretty wife, her sister and several children. The family lived in a tenant farm which only declared its nobility by means of a dovecote. The Trémaudans live there still. Wiser and more fortunate than I, they have never lost sight of the towers of that château which I left thirty years ago; they still live as they lived when I went to eat brown bread at their table; they have never left that refuge which I have never re-entered. Perhaps they are speaking of me at the same instant that I am writing this page: I reproach myself for dragging their name from its sheltering obscurity. They doubted for a long time as to whether the man whom they heard of was indeed their petit chevalier. The rector or curé of Combourg, the Abbé Sévin, the same whose extolling of virtue I have listened to, has shown the same incredulity; he could not be persuaded that the little rascal, the friend of peasants, was the defender of religion; he ended by believing, and quotes me in his sermons, having once held me on his knee. These worthy men, who blend not one unfamiliar concept into their portrait of me, who see me as I was in my childhood and youth, would they know me today under the disguises of time? I would be obliged to tell them my name before they would wish to clasp me in their arms.

I bring misfortune to my friends. A game-keeper, called Raulx, who was attached to me, was killed by a poacher. This murder made an extraordinary impression on me. What a strange mystery there is in human sacrifice! Why must it be that the greatest crime and the greatest glory lie in shedding human blood? My imagination showed me Raulx, holding his entrails in his hands, dragging himself to the cottage where he died. I conceived the notion of vengeance; I would have liked to attack the assassin. In this respect I was oddly endowed at birth: in the first moment of injury, I scarcely feel it; but it imprints itself on my memory; the remembrance instead of waning, waxes with time; it remains in my heart for months, entire years, then it wakes on the least occasion with fresh force, and my wound becomes more vivid than on the first day. But if I never forgive my enemies, I do them no harm; I bear a grudge but am not vindictive. Having the power to revenge myself, I lose the desire; I could only be dangerous in misfortune. Those who thought me ready to yield to their oppression were wrong; adversity is for me what the earth was to Antaeus: I gather strength at my mother’s breast. If ever good fortune has taken me in its arms, it has suffocated me.

Book II: Chapter 3: Holidays again at Combourg – The Conti Regiment – Camp at Saint-Malo – An Abbey – The Theatre – My two eldest sisters’ marriages – Return to school – A revolution begins in my ideas

Dieppe, October 1812.

BkII:Chap3:Sec1

I returned to Dol, much to my regret. The following year there was a campaign to make a landing on Jersey, and a camp was established near Saint-Malo. Troops were billeted at Combourg; Monsieur de Chateaubriand, out of courtesy, successively provided lodging for the colonels of the Touraine and Conti Regiments; one was the Duc de Saint-Simon, and the other the Marquis de Causans. (I have experienced a real pleasure in again meeting this gallant gentleman, distinguished for his loyalty and Christian virtues, since the Restoration. Note: Geneva, 1831). A score of officers were invited to my father’s table every day. The pleasantries of these officers displeased me; their walks disturbed the peace of my woodlands. It was through seeing the lieutenant-colonel of the Conti Regiment, the Marquis de Wignacourt galloping beneath the trees, that the idea of travel entered my head for the first time.

When I heard our guests talking of Paris and the Court, I was saddened; I tried to guess what Society was like: I imagined something vague and far-off; but soon became confused. Gazing at the world from the tranquil regions of innocence, I felt giddy, as one does when looking at the earth from the height of one of those towers lost in the heavens.

One thing however charmed me, the parade. Each day, the new guard, led by the drummer and band, would file past the foot of the staircase in the Green Court. Monsieur de Causans proposed showing me the camp on the coast: my father consented.

BkII:Chap3:Sec2

I was accompanied to Saint-Malo by Monsieur de La Morandais, a gentleman of good family, whom poverty had reduced to being the steward of the Combourg estate. He wore a coat of grey camlet, with a little silver band at the collar, and a cap or headpiece of grey felt with earflaps, with a peak in front. He put me behind him on the crupper of his mare Isabelle. I held on to the belt that carried his hunting knife, attached to the outside of his coat: I was delighted. When Claude de Bullion, and President de Lamoignon’s father, travelled to the country, as children: ‘They were both carried by the same donkey, in the panniers, one on one side, and one on the other, and they packed a loaf of bread next to Lamoignon, since he was lighter than his friend, to act as a counterweight.’ (Memoirs of President de Lamoignon)

Monsieur de La Morandais took shortcuts:

Gladly, in a noble manner,

On he rode by wood and river:

For no one rode more cheerfully

Than François beneath the tree.

We stopped for dinner at a Benedictine Abbey, which, for lack of a sufficient number of monks had been incorporated in a leading community of the order. We only found the bursar there, who had been charged with disposing of the furnishings, and selling the timber. He served us an excellent meal without meat, in what had been the Prior’s library: we ate a quantity of new-laid eggs with some carp and huge pike. Through the arches of a cloister I could see tall sycamores, bordering a pond. An axe struck at the foot of each tree, its crown trembled in the air, and it fell, providing us with a show. Carpenters from Saint-Malo were sawing off green branches as one trims hair on a young head, or squaring off the fallen trunks. My heart bled at the sight of those decimated woods and that deserted monastery. The general sack of religious houses has reminded me since of the despoliation of the abbey, which was for me a portent.

Arriving at Saint-Malo, I met the Marquis de Causans; under his escort I traversed the avenues of the camp. The tents, the stacks of weapons, the tethered horses, made an attractive scene together with the sea and its vessels, and the high walls and distant steeples of the town. I saw pass by, on a barb at full gallop, one of those men with whom a world draws to an end, the Duc de Lauzun. The Prince de Carignan, having joined the camp married Monsieur de Boisgarin’s daughter, charming though a little lame: it caused a great row and led to a legal case that Monsieur Lacretelle the Elder is even now defending. But what relationship do these events have to my life? ‘In proportion as the memory of my intimate friends gives them a complete view of their subject,’ says Montaigne, ‘so they push their narrative into the past, so that if the story is a good one they smother its virtues, if it is not you curse their fortunate powers of memory or their unfortunate lack of judgement...I have known some very amusing tales become most tiresome in the mouth of a certain gentleman.’ I am afraid of being that gentleman.

‘Saint-Malo’

La Bretagne Ancienne et Moderne. Illustré - Pitre-Chevalier (p448, 1859)

The British Library

BkII:Chap3:Sec3

My brother was at Saint-Malo, when Monsieur de La Morandais deposited me there. One evening he said: ‘I’m taking you to the theatre: get your hat.’ I lost my head and went straight to the cellar to find my hat which was in the attic. A troupe of strolling players had just arrived. I had seen marionettes; I imagined that at the theatre one saw puppets much superior to those in the street.

I arrive with beating heart at a wooden building on a deserted road. I entered through dark corridors, not without a certain feeling of apprehension. A little door was opened, and there I was with my brother in a box half-full of people.

The curtain had risen, the play began: they were performing Diderot’s Le Père de famille. I saw two men walking about the stage and talking, while everybody looked at them. I took them for the managers of the puppet-show, chatting outside the Old Woman’s hut, waiting for the audience to arrive: I was surprised only by the fact that they talked so loudly of their affairs, and were listened to in silence. My astonishment grew when other people arriving on stage started waving their arms about and weeping, and everyone started weeping in sympathy. The curtain fell without my understanding anything of this. My brother went downstairs to the foyer between the two plays. Left in the box among strangers, a situation which my shyness rendered a torment, I would have preferred to be in the haven of my school. Such was the first impression I gained of the art of Sophocles and Molière.

The third year of my life at Dol was marked by the marriage of my two eldest sisters: Marianne to the Comte de Marigny, Bénigne to the Comte de Québriac. They accompanied their husbands to Fougères, a signal for the dispersal of a family whose members were destined soon to separate. My sisters received the nuptial blessing at Combourg on the same day, at the same time, at the same altar, in the chapel of the château. They wept, my mother wept; I was astonished by this sadness: I understand it today. I never attend a baptism or a wedding without smiling bitterly or experiencing a contraction of my heart. After the misfortune of being born, I know none greater than that of giving birth to a human being.

BkII:Chap3:Sec4

That same year saw a revolution in my person as in my family. Chance caused two very different books to fall into my hands, an unexpurgated Horace and a history of Painful Confessions. The mental upheaval that these two books produced in me is unbelievable: a new world came into being around me. On the one hand, I suspected secrets incomprehensible to one of my age, an existence different from my own, pleasures beyond my games, charms of an unknown nature in a sex of which I had seen only a mother and sisters; on the other, spectres dragging chains along and vomiting flames announced eternal punishment for a single concealed sin. I lost sleep; at night I thought I could see black hands and white hands passing in turn across my curtains: I came to imagine that the latter hands were cursed by religion, and this idea added to my horror of the infernal shades. I searched in vain in heaven and hell for an explanation of a double mystery. Assaulted suddenly both morally and physically, I continued to struggle in my innocence against the storms of premature passion and the terrors of superstition.

From then on I felt several sparks fly from that fire which is the transmission of life. I analysed the fourth book of the Aeneid and read Télémaque: all at once I discovered in Dido and in Eucharis beauties that ravished me; I became aware of the music of those marvellous verses and of classical prose. One day I translated impromptu the Aeneadum genitrix, hominum divumque voluptas: Mother of Aeneas, delight of men and gods of Lucretius with so much liveliness that Monsieur Égault tore up the poem, and set me to work on Greek roots. I stole a Tibullus: when I reached Quam juvat immites ventos audire cubantem: What joy to hear the raging winds as I lie there, those feelings of sensual delight and melancholy showed me my true nature. The volumes by Massillon containing the sermons of the Adulteress and the Prodigal Son never left my side. I was not allowed to leaf through books since there were few doubts as to what I might discover. I would steal little bits of candle from the chapel to read, at night, those seductive descriptions of the disorders of the soul. I would fall asleep stammering incoherent phrases, in which I would try to capture the sweetness, meter, and grace of the writer who had best conveyed the Racinian euphony in prose.

If, since that time, I have depicted with some degree of truth the movements of the heart mingled with Christian remorse, I am persuaded that I have owed that success to chance, which at the same moment led me to comprehend two inimical empires. The ravages that a doubtful book inflicted on my imagination were compensated for by the terrors that another book inspired in me, and these were softened to some extent in turn by the tender thoughts which certain unveiled pictures had left with me.

Book II: Chapter 4: The adventure of the magpie – Three holidays at Combourg – The charlatan – Return to school

Dieppe, End of October 1812.

BkII:Chap4:Sec1

What one says of our misfortunes, that they never arrive singly, one can say of the passions: they appear together, like the Muses or the Furies. Accompanying the propensity which began to torment me, the sense of honour arose in me; spiritual exaltation, that renders the heart incorruptible in the midst of corruption; a kind of principle of reclamation set against one of destruction, like the inexhaustible fount of wonders that love asks of youth, and of the sacrifices which it demands.

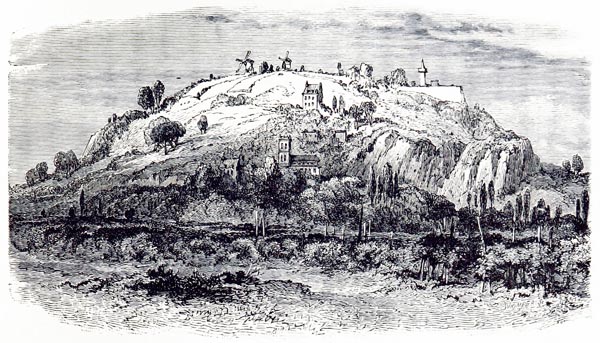

When the weather was fine, the school boarders were allowed out on Thursdays and Sundays. We often headed for Mont-Dol, on the summit of which stood some Gallo-Roman ruins: from the heights of this isolated hill the eye glided over the sea, and over the marshes where will-o’-the-wisps flickered at night, witches’ lights that burn today in our lamps. Another objective of our walks was the meadows surrounding a Seminary of Eudists, the name deriving from Eudes, the brother of the historian Mézeray, the founder of their congregation.

‘Le Mont Dol’

La France Pittoresque. Ouvrage Illustré - Jules Gourdault (p73, 1893)

The British Library

One day in May, the Abbé Égault, prefect for the week, led us to the seminary: we were allowed great freedom in our games, but were expressly forbidden to climb trees. The master, having set us on a grassy path, moved off to recite his breviary.

Elms bordered the path; right at the top of the tallest a magpie’s nest glowed: we were lost in admiration, the mother-bird sitting on her eggs visible to all of us, and we were seized by a strong desire to gain that magnificent prize. But who would dare attempt the adventure? The rule was so strict, the master so near, the tree so tall! All hope rested on me; I climbed like a cat. I hesitated: then glory inspired me: I shed my coat, I grasped the elm, and began to climb. The trunk was free of branches for two thirds of its height: there it forked, one of the limbs bearing the nest.

My friends, gathered under the tree, hailed my efforts, watching me, watching the place from which the prefect might appear, quivering with joy in hope of the eggs, dying with fear in expectation of punishment. I reached the nest; the magpie flew off; I snatched the eggs, put them inside my shirt and descended. Unfortunately I allowed myself to slip between the twin trunks, and hung astride the fork. The tree had been trimmed, I was unable to gain support for my feet on the right or left in order to raise myself and regain the outer edge: I was left hanging fifty feet in the air.

Suddenly there was a shout: ‘The prefect is coming!’ and I found myself abandoned immediately by my friends, as is customary. Only one, named Le Gobbien, tried to help me, but was soon obliged to renounce his generous attempt. There was only one way to escape my unfortunate situation; that was to hang by my hands from one of the two limbs of the fork, and try to grip the tree-trunk below the fork with my feet. I executed the manoeuvre at the risk of my life. In the midst of my tribulations, I had not let go of my treasure; though I would have been better off letting go of it, as I have since let go of many another. Sliding down the trunk I scorched my hands, scraped my legs and chest, and crushed the eggs: it was that which gave me away. The master had not seen me up the tree; I hid the scratches from him easily enough, but there was no way of concealing the bright yellow colour with which I was stained. ‘Come, Monsieur,’ he said, ‘you shall be whipped.’

BkII:Chap4:Sec2

If that gentleman had announced to me that he would commute the punishment to one of death, I would have experienced a feeling of joy. The idea of shame had not yet been part of my wild education: at every period of my life there has been no torture I would not have preferred to the horror of having to blush before a living creature. Indignation rose in my heart; I replied to the Abbé Égault, in a tone that was not that of a child, but that of a man, that neither he nor anyone else would ever lay a hand on me. This reply roused him; he called me a rebel, and promised to make an example of me. ‘We will see,’ I answered, and started playing ball with a sang-froid that astonished him.

We returned to school; the master made me go to his room, and ordered me to submit. My exalted sentiments gave way to a flood of tears. I reminded the Abbé Égault that he had taught me Latin; that I was his pupil, his disciple, his child; that he would not wish to dishonour his pupil, and make the sight of my friends insupportable to me; that he could put me in prison, on bread and water, deprive me of my amusements, set me tasks, pensums; that I would be grateful to him for his clemency and would love him the more for it. I fell at his feet; I clasped my hands; I begged him to spare me for Jesus Christ’s sake: he remained deaf to my pleas. I rose up, full of anger, and lashed out at his legs so wildly that he let out a cry. He ran to close the door of his room, double-locked it and returned to me. I took refuge behind his bed; he laid into it with blows from his iron ruler. I twisted about in my hiding place and rousing myself to combat, I cried out:

‘Macte animo, generose puer! Bless your courage, noble child!’

This comical erudition made my enemy laugh despite himself: he spoke of armistice: we concluded a treaty; I agreed to submit to the principal’s judgement. Without deciding in my favour, the principal still wished me to escape the punishment I had resisted. When the excellent priest pronounced my acquittal, I kissed the hem of his robe with such a show of feeling and gratitude, that he could not resist giving me his blessing. So ended the first struggle that made me render homage to what became the idol of my life, and to which on so many occasions I have sacrificed peace, pleasure and fortune.

BkII:Chap4:Sec3

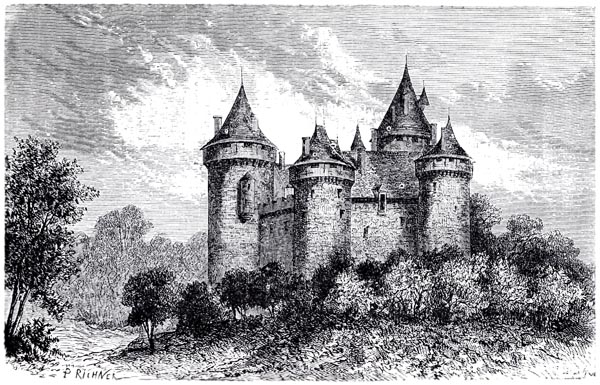

The holidays during which I entered on my twelfth year were sad ones; the Abbé Leprince accompanied me to Combourg. I never went out except with my tutor; we went for long aimless walks together. He was dying of consumption; he was melancholy and silent; I was scarcely any happier. We walked for hours, one behind the other, without speaking a word. One day we lost our way in the woods; Monsieur Leprince turned to me and said: ‘Which path shall we take?’ I replied without hesitating: ‘the sun is setting; at this moment it is striking the window of the great tower: let us go that way.’ Monsieur Leprince told my father of it that evening: the future traveller revealed himself in my decision. Many a time, seeing the sun set in the forests of America, I recalled the woods of Combourg: my memories echo one another.

‘Château de Combourg’

Géographie du Département d'Ille-et-Vilaine - Adolphe Laurent Joanne (p50, 1881)

Internet Archive Book Images

The Abbé Leprince wished for me to be given a horse; but in my father’s opinion a naval officer only needed to know how to handle a boat. I was reduced to riding two fat coach-horses or a big piebald, in secret. The latter was not, like Turenne’s Pie, one of those war-horses that the Romans called desultorios equos: circus horses, trained to help their masters; it was a temperamental Pegasus whose hooves knocked together when it trotted, and who bit my legs when I set it at a ditch. I have never cared much for horses, though I have led the life of a Tartar: and contrary to the effect that my early training should have produced, I ride with more elegance than soundness.

The tertian fever, the germs of which I had brought from the marshes of Dol, relieved me of Monsieur Leprince. A seller of remedies passed through the village; my father, who had no faith in doctors, believed in charlatans: he sent for the quack who swore he would cure me in twenty-four hours. He returned the following day in a green coat trimmed with gold braid, a large powdered wig, huge ruffles of dirty muslin, false gems on his fingers, worn black satin breeches, bluish-white silk stockings, and shoes with enormous buckles.

He opened my bed-curtains, felt my pulse, made me put out my tongue, spoke a few words of broken Italian regarding the necessity of purging me, and gave me a little piece of caramel to eat. My father approved of all this, since he maintained that all illness arose from indigestion, and for every kind of malady it was essential to purge a patient till he bled.

Half an hour after swallowing the caramel, I was seized with terrible vomiting; Monsieur de Chateaubriand was told, and wished to hurl the poor devil from the window of the tower. The latter, terrified, took off his coat, and rolled up his sleeves, making the most grotesque gestures imaginable. With every movement, his wig swung about in all directions; he echoed my cries adding after each: ‘Che? Monsou Lavandier?’ This Monsieur Lavandier was the village pharmacist, who had been called in to assist. I could scarcely tell, in the midst of my pain, whether I would die from the man’s medicines or from the bursts of laughter he drew from me.

The effects of this overdose of emetic were countered, and I was set on my feet again. All our life is spent wandering around our grave; our various maladies are so many puffs of wind that carry us nearer to or further from harbour. The first dead person I saw was a canon of Saint-Malo; he lay lifeless on a bed, his face distorted by his last convulsions. Death is beautiful, she is our friend, yet we do not recognise her, because she appears masked to us, and because her mask terrifies us.

I was sent back to school at the end of the autumn.

Book II: Chapter 5: Invasion of France – Games – The Abbé de Chateaubriand

Vallée-aux-Loups, December 1813.

BkII:Chap5:Sec1

From Dieppe where the police injunction had obliged me to take refuge, I was allowed to return to the Vallée-aux-Loups, where I continue my story. The earth trembles under the feet of foreign soldiers, who at this very moment are invading my country; I write like one of the last Romans, amidst the sounds of the Barbarian invasion. By day I trace pages as troubled as the events of the day (De Bonaparte et des Bourbons. Note: Geneva, 1831); at night, while the rumble of distant cannon expires among my woods, I return to the silence of years that sleep in the tomb, to the tranquillity of my earliest memories. How narrow and brief a man’s past is, beside the vast present of nations and their immense future!

Mathematics, Greek and Latin occupied the whole of my winter at school. What was not dedicated to study was given up to those childhood games played in ever place. The little English boy, the little German, the little Italian, the little Spaniard, the little Iroquois, the little Bedouin all bowl the hoop and throw the ball. Brothers in one great family, children lose their common features only when they lose their innocence, which is the same everywhere. Then the passions, modified by climate, government and customs, differentiate the nations; the human race ceases to speak and hear the same language: society is the true tower of Babel.

One morning I was engrossed in a game of prisoner’s base in the great courtyard of the school; someone came to tell me I was wanted. I followed the servant to the main gate. There I found a stout, red-faced man with a brusque and impatient manner, and a fierce voice, with a stick in his hand, wearing an untidy black wig, a torn cassock with the ends tucked into the pockets, dusty shoes, and stockings with holes in the heels: ‘Little scamp,’ he said, ‘aren’t you the Chevalier de Chateaubriand de Combourg?’ ‘Yes, Monsieur,’ I replied, ‘amazed by his form of address. ‘And I,’ he continued, almost foaming at the mouth, ‘I am the last of the elder branch of your family, I am the Abbé de Chateaubriand de la Guerrande; take a good look at me.’ The proud Abbé put his hand into the fob pocket of an old pair of plush breeches, took out a mouldy six-franc crown piece wrapped in dirty paper, flung it in my face, and continued his journey on foot muttering his matins with a furious air. I have since learnt that the Prince de Condé had offered this country rector the post of tutor to the Duc de Bourbon. The vain priest replied that the Prince, as owner of the Barony of Chateaubriand, ought to know that the heirs to that barony could have tutors, but not be tutors themselves. This pride was my family’s main fault; in my father it was odious; my brother took it to ridiculous lengths; it has passed in some degree to his eldest son. I am not sure, despite my republican leanings, that I am completely free from it myself, though I have carefully concealed it.

Book II: Chapter 6: First Communion – I leave Dol College

BkII:Chap6:Sec1

The time for making my first communion approached, the moment when in my family the child’s future state was determined. This religious ceremony took the place among young Christians of the assumption of the toga virilis among the Romans. Madame de Chateaubriand had come in order to be present at the first communion of a son who, after being united to God, would be separated from his mother.

My piety appeared sincere; I edified the whole school: my looks were ardent; my fasts were frequent enough to give my masters concern. They feared excessive devotion; enlightened religion sought to moderate my fervour.

For confessor I had the superior of the Eudist seminary, a man of fifty with a stern appearance. Every time I presented myself at the confessional, he questioned me anxiously. Surprised at the triviality of my sins, he did not know how to reconcile my distress with the lack of importance of the secrets I confided to him. The nearer Easter came, the more pressing the priest’s questions became. ‘Are you hiding anything from me?’ he asked. I replied: ‘No, father.’ ‘Have you committed such and such a sin?’ ‘No, father.’ It was always: ‘No, father.’ He dismissed me doubtfully, sighing, and gazing into the depths of my soul, while I left his presence pale and unnatural like a criminal.

I was to receive absolution on the Wednesday in Holy Week. I spent the night between Tuesday and Wednesday in prayer, or reading with terror the book of Painful Confessions. On the Wednesday, at three in the afternoon, we left for the seminary; our parents accompanying us. All the idle fame that has since attached itself to my name would not have given Madame de Chateaubriand one iota of the pride which she experienced, as a Christian and a mother, in seeing her son ready to participate in the great mystery of religion.

BkII:Chap6:Sec2

Arriving at the church, I prostrated myself before the altar and lay there as if annihilated. When I rose to go to the sacristy, where the superior awaited me, my knees trembled beneath me. I threw myself at the priest’s feet, and it was only in the most strangled of tones that I managed to pronounce my Confiteor. ‘Well, have you forgotten nothing?’ the man of God asked me. I remained silent. His questions continued, and always the fatal, no, my father, issued from my lips. He meditated, he asked for counsel of Him who conferred on the apostles the power of binding and loosing souls. Then, making an effort, he prepared to give me absolution.

If Heaven had shot a thunderbolt at me it would have caused me less dread. I cried out: ‘I have not confessed all!’ This redoubtable judge, this delegate of the Supreme Arbiter, whose face so inspired me with fear, became the most tender of shepherds; he embraced me, and melted with tears: ‘Come now,’ he said to me, ‘my dear boy, courage!’

I will never know such another moment in my life. If the weight of a mountain had been lifted from me, I could not have been more relieved: I sobbed with happiness. I venture to say that it was on that day that I became an honest man; I felt that I could never survive remorse: how great it must be for a crime, if I could suffer so much from hiding childish weaknesses! But how divine that religion is that can seize on our best instincts in this way! What moral precepts could ever replace these Christian institutions?

The first step having been made, the rest cost little: the childish things I had concealed, and which would have made the world smile, were weighed in the balance of religion. The superior was greatly embarrassed; he would have wished to delay my communion, but I was about to leave Dol College and would soon be entering the Navy. With great sagacity he discovered in the very character of my youthful sins, insignificant as they were, the nature of my propensities: he was the first person to penetrate the secret of what I might become. He divined my future passions; he did not hide from me the good he thought he saw in me, but he also predicted the evils to come. ‘After all,’ he added, ‘you have little time for penitence; but you have been cleansed of your sins by a courageous, though tardy, avowal.’ Raising his hand, he pronounced the formula of absolution. On this second occasion, that fearful hand showered only heavenly dew on my head; I lowered my brow to receive it; what I felt partook of the angels’ joy. I ran to fling myself on my mother’s breast where she waited for me at the foot of the altar. I no longer seemed the same person to my masters and schoolfellows; I walked with a light step, head held high, with a radiant air, in all the triumph of repentance.

BkII:Chap6:Sec3

The next day, Maundy Thursday, I was admitted to that sublime and moving ceremony whose image I have vainly attempted to describe in Le Génie du Christianisme. I might have felt my usual little humiliations there too: my nosegay and my clothes were not as fine as those of my companions; but that day all was of God and for God. I know exactly what Faith is: the Real Presence of the Victim in the Blessed Sacrament on the altar was as manifest as the presence of my mother at my side. When the Host was laid on my tongue, I felt as though all were alight within me. I trembled with veneration, and the only material thing that occupied my thoughts was the fear of profaning the sacred bread.

The bread I offer you

Serves the angels for food,

For God has made it too

From his crops good and true.

I again understood the courage of the martyrs; at that moment I would have been able to witness to Christ on the rack, or surrounded by lions.

I like to recall those felicities, which in my soul only just preceded the world’s tribulations. In comparing that ardour to the transports I am going to portray; in viewing the same heart experiencing during the interval of three of four years all that innocence and religion possess of what is sweetest and most salutary, and all that the passions possess of what is most seductive and disastrous, you may choose between two joys; you may see in what direction we should search for happiness, and above all peace.

Three weeks after my first communion, I left Dol College. A pleasant memory of that place remains with me: our childhood leaves something of itself in the places it has embellished, as a flower transfers its perfume to the objects it touches. I still feel moved to this day when thinking of the dispersal of my first schoolfellows and my first masters. The Abbé Leprince, appointed to a living near Rouen, did not survive long; the Abbé Egault obtained a curacy in the diocese of Rennes, and I saw the principal, the good Abbé Portier, die at the start of the Revolution: he was learned, gentle and simple of heart. The memory of that obscure Rollin will always be dear and venerable to me.

Book II: Chapter 7: Mission at Combourg – Rennes College – I meet Gesril again – Moreau – Limoëlan – My third sister’s marriage

Vallée-aux-Loups, End of December 1813.

BkII:Chap7:Sec1

At Combourg I found food for my piety, a mission; I followed its exercises. I received the sacrament of Confirmation on the steps of the manor, with the peasant boys and girls, from the Bishop of Saint-Malo’s hand. Afterwards, a cross was erected; I helped to support it while it was being fixed on its base. It still exists: it stands in front of the tower in which my father died. For thirty years it has seen no-one appear at the windows of that tower; it is no longer saluted by the children of the château; each spring it waits for them in vain; it only sees the swallows return, the companions of my childhood, more loyal to their nest than man to his home. How happy I would have been if my life had been spent at the foot of the mission cross, if my hair had only been whitened by the years that have covered the arms of that cross with lichen!

I did not wait long before leaving for Rennes. I was to continue my studies and complete my mathematics course in preparation for my examination as a Naval Guard at Brest.

Monsieur de Fayolle was the principal of Rennes College. In this Breton ‘Juilly’ there were three distinguished teachers, the Abbé de Chateaugiron for the humanities, the Abbé Germé for rhetoric, and the Abbé Marchand for physics. Both boarders and day-pupils were numerous, the classes hard. Later, Geoffroy and Ginguené, who graduated from this college, would have brought honour to Sainte-Barbe or Plessis. The Chevalier de Parny also studied at Rennes; I inherited his bed in the room I was assigned.

BkII:Chap7:Sec2

Rennes seemed like a Babylon to me, the school a world. The multitude of masters and boys, the extent of the buildings, gardens and playground struck me as immense; I grew used to it however. On the Principal’s name day we were given a few days off; we sang magnificent couplets of our own, at the tops of our voices, in his praise, or we recited:

O Terpsichore, O Polyhymnia,

Come, come inspire our voices;

Reason itself invites you here.

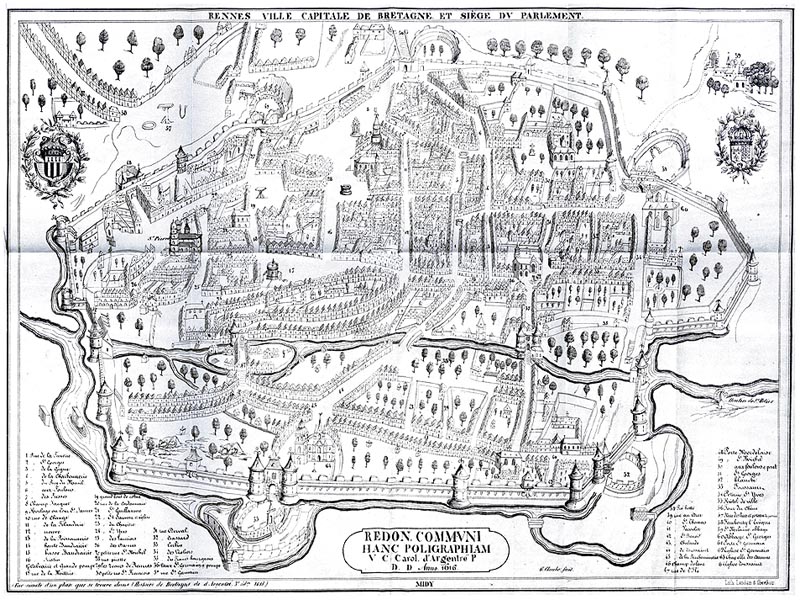

‘Rennes Ville’

Histoire de Rennes - Émile Ducrest De Villeneuve and Dominique Maillet (p563, 1845)

The British Library

I acquired over my new schoolmates the same ascendancy I had exercised over my old companions at Dol: it cost me a few blows. Breton scamps are quarrelsome; on half-holidays we exchanged invitations to fight in the shrubberies of the Benedictines’ garden, called the Thabor: we used mathematical compasses fixed to the end of a cane, or we fought hand to hand more or less treacherously or courteously according to the gravity of the challenge. There were umpires who decided whether a forfeit was due, and in what ways the champions could use their hands. The combat did not end until one of the two contestants acknowledged himself vanquished. I found my old friend Gesril here, presiding, as at Saint-Malo, over these engagements. He wanted to be my second in an affair that I had with Saint-Riveul, a young nobleman who became the first victim of the Revolution. I fell beneath my adversary, refused to surrender, and paid dearly for my pride. Like Jean Desmarets on his way to the scaffold, I said: ‘I cry mercy to God alone.’

At the College I met two men who have since become famous in different ways: Moreau, the general, and Limoëlan, creator of the infernal machine, who is now a priest in America. There is only one portrait of Lucile in existence and this poor miniature was created by Limoëlan, who turned portrait painter during the revolutionary troubles. Moreau was a day-boy, Limoëlan a boarder. Such singular destinies have rarely been found together at the same moment, in the same province, in the same small town, in the same educational establishment. I can’t help recounting a school prank that my friend Limoëlan played on the prefect for the week.

BkII:Chap7:Sec3

The prefect used to make his round of the corridors after lights out to see if all was well: to achieve this he would look through a hole cut in each of the doors. Limoëlan, Gesril, Saint-Riveul and I slept in the same room:

‘Of evil creatures it made a very good dish.’

We had stopped the holes with paper on several occasions, in vain; the prefect poked the paper out and caught us jumping on our beds and breaking chairs.

One evening, Limoëlan, without telling us his plan, persuaded us to go to bed and douse the light. Soon we heard him get up, go to the door, and then return to bed. A quarter of an hour passed, and here came the prefect on tiptoe. Since we were suspects of his, for sound reasons, he stopped at our door, listened, looked, saw no light at all, thought the hole blocked and imprudently stuck his finger in.imagine his anger! ‘Who’s done this?’ he shouted rushing into the room. Limoëlan was choking with laughter, and Gesril asked in a nasal voice, in his half innocent half mocking way: ‘What is it, Monsieur le Prefect?’ Thereupon, Saint-Riveul and I, laughing like Limoëlan, hid our heads under the bedclothes.

They could get nothing out of us: we were heroic. We were all four imprisoned in the vaults: Saint-Riveul dug out the earth beneath a door that led to the farmyard; he stuck his head into this mole-hill, and a pig ran up and made as if to eat his brains; Gesril slid into the College cellars and set a barrel of wine flowing; Limoëlan demolished a wall, while I, a new Perrin Dandin, climbing to a ventilator, stirred the mob in the street with my harangues. The fearful creator of the infernal machine, playing this school prank on a college prefect, recalls the young Cromwell, inking the face of another regicide who signed Charles I’s death warrant after him.

BkII:Chap7:Sec4

Though the regime at Rennes College was very religious, my fervour abated: the multitude of masters and school friends multiplied the occasions for distraction. I made progress in my language studies; I became strong in mathematics, for which I have always had a decided leaning: I would have made a good naval officer or engineer. All in all, I was born with a ready disposition: alert to serious as well as pleasant things, I began with poetry, before arriving at prose: the arts enraptured me; I have loved music and architecture passionately. Though quick to become bored by everything, I have been capable of plenty of fine detail; having been endowed with patience for every trial, though weary of the aim that possesses me, my persistence is greater than my distaste. I have never abandoned any matter that has been worth the effort of completion; there are things in my life I have pursued for fifteen or twenty years, as full of ardour on the last day as on the first.

This mental flexibility appeared in secondary matters. I was good at chess, skilful at billiards, hunting and fencing; I drew passably well; I would have sung well, if my voice had been trained. All this, combined with the way I was educated, and the life of a soldier and traveller, ensured I have never considered myself a pedant, have never displayed a dull or conceited manner, the awkwardness, the slovenly habits of previous men of letters, still less the arrogance and self-assurance, the envy and blustering vanity of the new authors.

BkII:Chap7:Sec5

I spent two years at Rennes College; Gesril left eighteen months before me. He entered the Navy. Julie, my third sister, was married in the course of those two years: she wedded the Comte de Farcy, a captain in the Condé Regiment, and settled at Fougères with her husband, where my two elder sisters, Mesdames de Marigny and de Québriac were already living. Julie’s marriage took place at Combourg, and I assisted at the wedding. There I met that Comtesse de Trojolif who was noted for her courage on the scaffold: a cousin and close friend of the Marquis de La Rouërie, she was involved in his conspiracy. I had not seen beauty until then, except in my own family; I was confused at finding it in the face of this stranger. Every step in my life opened a new perspective; I heard the distant seductive voice of the passions approaching me; I hurried towards those Sirens, drawn by an unfamiliar music. It so happened that like the High Priest at Eleusis I had different incense for each deity. But could the hymns I sang, while burning this incense, be called Perfumes, like the poems of the hierophant?

Book II: Chapter 8: I am sent to Brest to take the Navy examination – The Port of Brest – I meet Gesril again – La Pérouse – I return to Combourg

Vallée-aux-Loups, January 1814.

BkII:Chap8:Sec1

After Julie’s wedding I set out for Brest. I did not feel the same regret on quitting the great College of Rennes that I experienced on leaving the little College of Dol; perhaps I no longer possessed that innocence that makes everything seem attractive to us: my youth was no longer in bud, time was beginning to unfurl it. In my new position I had as mentor one of my maternal uncles, the Comte Ravenel de Boisteilleul, commander of a squadron, one of whose sons, a highly distinguished artillery officer in Bonaparte’s armies, married the only daughter of my sister the Comtesse de Farcy.

Arriving at Brest, I failed to find my cadet’s commission waiting; some accident had delayed it. I remained what was known as an aspirant, and as such was exempt from the usual studies. My uncle put me to board in the Rue de Siam, at a cadets’ hostel, and introduced me to the Naval Commander, Comte d’Hector.

Left to my own devices for the first time, instead of making friends with my future messmates, I retreated into my customary solitude. My habitual society was confined to my masters in fencing, drawing and mathematics.

At Brest, that sea which I was to meet with on so many coasts washed the tip of the Armorican peninsula: beyond this prominent cape, there lay only a boundless ocean and unknown worlds; my imagination delighted in those deeps. Often, sitting on some mast laid along the Quai de Recouvrance, I watched the movements of the crowd: shipwrights, sailors, soldiers, customs-men, and convicts passed to and fro in front of me. Voyagers embarked and disembarked, pilots controlled some manoeuvre, carpenters planed blocks of wood, rope-makers spun their cables, ship’s-boys lit fires under coppers which gave off clouds of smoke and the healthy smell of tar. Bales of merchandise; sacks of victuals; trains of artillery were carried up, carried down, rolled along from sea to magazine and magazine to sea. Here carts backed into the water to receive their cargo; there hoists lifted loads, while cranes lowered stones, and dredging machines dug out silt. Forts repeated signals, launches came and went, and vessels cast off or anchored in the docks.

‘Brest’

La Bretagne Ancienne et Moderne. Illustré - Pitre-Chevalier (p88, 1859)

The British Library

My spirit was full of vague ideas regarding society, its virtues and faults. Some malaise overcame me; I left the mast on which I had been sitting; I climbed back up along the River Penfeld that flowed into the harbour; I reached a bend where the harbour vanished. There, with nothing to see but a peaty valley, but still hearing the confused murmur of the sea and the voices of men, I lay down on the brink of the little river. Now watching the water flow, now following with my eyes the flight of a chough, enjoying the silence around me, or listening to the blows of the caulking hammers, I fell into the profoundest reverie. In the midst of it, if the wind brought me the sound of a canon fired by some vessel setting sail, I would shiver and tears would fill my eyes.

BkII:Chap8:Sec2

One day, I had set out to walk to the far end of the harbour, towards the sea: it was warm; I lay down on the beach and fell asleep. Suddenly I was woken by a tremendous noise: I opened my eyes, as Augustus did seeing the triremes in the anchorage of Sicily, after the victory over Sextus Pompey; the reports of guns followed; the roads were crowded with ships: the great French squadron was returning after the signing of peace. The ships manoeuvred under sail, hoisted their lights, showed their colours, presented their sterns, bows or broadsides to the shore, stopped short by dropping anchor in mid-course, or continued to skim the waves. Nothing has ever given me a more exalted idea of the human spirit; man seemed at that moment to have borrowed something from Him who said to the sea: ‘You shall go no further. Non procedes amplius.’

All Brest hurried to the harbour. Launches detached themselves from the fleet and came alongside the mole. The officers with which they were crowded, faces bronzed by the sun, had that foreign look one brings back from another hemisphere and an ineffable air of gaiety, pride and daring, as befitted men who had come from restoring the honour of the national ensign. This naval corps, so worthy and illustrious, companions of Suffren, La Motte-Picquet, Couëdic and D’Estaing, having escaped from enemy fire, were destined to fall to that of Frenchmen!

I was watching the brave troops file by, when one of the officers left his comrades and fell upon my neck: it was Gesril. He seemed taller, but was weak and ailing from a sword-thrust he had taken in the chest. He left Brest the same evening to rejoin his family. I saw him only once more, shortly before his heroic death; I will explain the circumstances later. Gesril’s appearance and sudden departure led me to take a decision which changed the course of my life: it was written that this young man should exert an absolute influence on my destiny.

BkII:Chap8:Sec3

Once can see how my character was shaping, what turn my ideas were taking, what the first symptoms of my genius were, since I can speak of it as an illness, whatever it may have been, rare or common, worthy or unworthy of the name I give it, for lack of another word that might express it better. I would have been happier if I had been more like other men: anyone who, without destroying my spirit, could have managed to kill what is called my talent would have done me a friendly service.

When the Comte de Boisteilleul took me to meet Monsieur Hector, I heard sailors, young and old, recounting their campaigns, and speaking of the countries they had visited: one had arrived from India, another from America; this one had to set sail for a round the world trip, that one was off to rejoin his Mediterranean station, to visit the shores of Greece. My uncle pointed out La Pérouse to me in the crowd, a new Cook, whose fate is a secret kept by the storms. I heard it all, and saw it all, without uttering a word; but there was no sleep for me that night: I spent it deep in imaginary battles, or discovering vast worlds.

Be that as it may, on seeing Gesril about to return to his parents, I decided that there was nothing to stop me going home to mine. I would have truly liked serving in the Navy, if my spirit of independence had not made me unfit for service of any kind: I have within me an inability to obey. Travel tempted me, but I felt I could only enjoy it alone, following my own whim. At last, showing the first evidence of my inconstancy, without telling my uncle Ravenel, without writing to my parents, without asking anyone’s permission, without waiting for my cadet’s commission, I left one morning for Combourg, where I arrived as if I had dropped from the sky.

I am still astonished today that given the terror my father inspired in me, I should have dared to take such a step, and what is just as astonishing is the manner in which I was received. I ought to have expected transports of violent anger, I was welcomed tenderly. My father contented himself with shaking his head as if to say: ‘Here’s a fine to-do!’ My mother kissed me, with a full heart, grumbling at the same time, my Lucile in an ecstasy of joy.

Book II: Chapter 9: A Walk – The Ghost of Combourg

Montboissier, July 1817.

BkII:Chap9:Sec1

Between the last date on these Memoirs, of January 1814 at the Vallé-aux-Loups, and today at Montboissier, in July 1817, three years and six months have passed. Did you hear the Empire fall? No: nothing has disturbed the peace of this place. Yet the Empire is destroyed; the vast ruin has collapsed while I am alive, like Roman remains tumbling into the bed of an unknown stream. But to one who considers them of no account, events are of little importance: a few years escaping from the hands of the Eternal will render justice to all these alarums with a silence without end.

The previous chapter was written under the dying tyranny of Bonaparte and by the gleam of the last lightning flashes of his glory: I begin the present chapter in the reign of Louis XVIII. I have seen kings close to, and my political illusions have vanished, like those gentler chimeras whose story I continue. Let us speak first of what led me to take up the pen: the human heart is everything’s toy, and one cannot foresee what trivial circumstance may cause its joys and its pains. Montaigne remarked on it: ‘No cause is required to agitate our soul’, he said, ‘a daydream without substance or meaning will rule and agitate it’

I am now at Montboissier, on the borders of La Beauce and Le Perche. The château on this estate belonging to Madame the Comtesse de Colbert-Montboissier, was sold and demolished during the Revolution: there are only two lodges left, separated by a fence and once forming the caretaker’s dwelling. The park, now in the English style, bears traces of its old French regularity: straight alleys, and copses trained into bowers, give it a formal air; it is as pleasing as a ruin.

Yesterday evening I took a solitary walk; the sky resembled an autumn sky; a cold wind often blew. At an opening in a thicket, I stopped to watch the sun: it sank into the clouds above the tower of Alluye, where Gabrielle, who lived in that tower, watched as I did the sun set two hundred years ago. What has become of Henri and Gabrielle? What I will have become, when these Memoirs are published.

I was drawn from my reflections by the song of a thrush perched on the topmost branch of a silver birch. In a moment, its magic brought the family home before my eyes; I forgot the catastrophes I had witnessed, and suddenly transported into the past I revisited those fields where I had so often heard the song of the thrush. When I listened to it then, I was as sad as I am now; but that first sadness was one which is born from a vague desire for happiness, while one still lacks experience; the sadness that I feel now arises from knowledge of things assessed and judged. The song of the bird in the woods of Combourg sustained that bliss in me that I thought to attain; the same song in the park of Montboissier recalled days lost in pursuit of that unachievable bliss. There is nothing more for me to learn; I have travelled faster than others, and made the tour of life. The hours fly past and carry me with them; I have not even the assurance of completing these Memoirs. In how many places have I already continued writing them, and in what place will I finish them? How many times shall I walk the wood’s edge? Let me profit from the few moments that remain to me; let me hasten to portray my youth, while I can still make contact with it: the traveller, leaving an enchanted shore forever, writes his journal in sight of a country that is departing, and will soon be lost.

Book II: Chapter 10: College at Dinan – Broussais – I return to my parents’ house

BkII:Chap10:Sec1

I have spoken of my return to Combourg, and how I was received there by my father, mother and sister Lucile.

Perhaps it has not been forgotten that my other three sisters were married, and that they lived on their new families’ estates near Fougères. My brother, whose ambition was beginning to develop, was more often in Paris than at Rennes. He first bought a post as maître des requêtes which he sold in order to take up a military career. He entered the Royal Cavalry Regiment; he then joined the diplomatic corps and accompanied the Count de la Luzerne to London, where he met André Chenier: he was on the point of obtaining the Vienna Embassy when our troubles broke out; he applied for that of Constantinople; but he faced a formidable rival, Mirabeau, to whom the embassy had been promised as a reward for joining the Court party. My brother had therefore only just left Combourg at the moment when I came to live there.

Entrenched in his manor, my father no longer left it, not even during the sittings of the States of Brittany. My mother went to Saint-Malo every year for six weeks, around Easter; she waited for that moment as one of release, since she detested Combourg. A month before the trip, it was discussed as though it was a hazardous enterprise; preparations were made; the horses were rested. On the eve of departure, they went to bed at seven in the evening, in order to rise at two. My mother, to her great satisfaction, set off at three in the morning, and spent the whole day covering thirty miles.

Lucile, who had been received as a canoness in the Chapter of L’Argentière, was to transfer to that of Remiremont: awaiting the move, she remained buried in the country.

BkII:Chap10:Sec2

As for myself, after my escape from Brest, I declared that my firm wish was to embrace the ecclesiastical state: the truth is that I was only trying to gain time, since I did not know what I wanted. I was sent to Dinan College to complete my humanities course. My Latin was better than that of my teachers; but I started to learn Hebrew. The Abbé de Rouillac was the Principal of the College, and the Abbé Duhamel was my tutor.

Dinan, adorned with ancient trees, fortified with old turrets, was built on a picturesque site, beneath a high hill at the foot of which the Rance flows, a tidal river; it overlooks pleasantly wooded sloping valleys. The mineral waters of Dinan have some renown. This town, full of history, the birthplace of Duclos, possesses among other antiquities Du Guesclin’s heart: heroic dust which, stolen during the Revolution, was on the verge of being ground down by a glazier for use in decorating stained glass; was it destined for various tableaux of victories achieved over our country’s enemies?

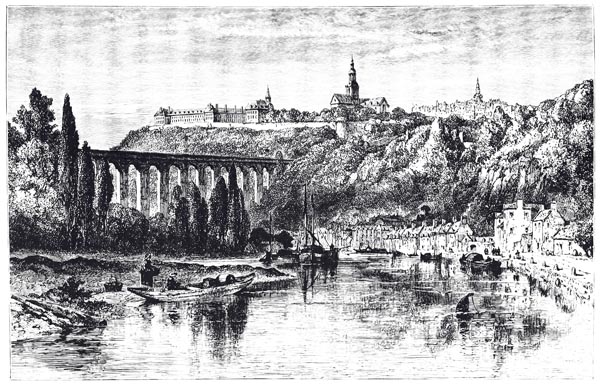

‘Dinan - Vue Prise des Bords de la Rance’

La France Pittoresque. Ouvrage Illustré - Jules Gourdault (p77, 1893)

The British Library

Monsieur Broussais, my compatriot, studied with me at Dinan; the students were taken off to bathe every Thursday, like the clerks under Pope Adrian I, or every Sunday, like the prisoners under the Emperor Honorius. Once I thought I would be drowned; on another occasion Monsieur Broussais was bitten by thankless leeches, lacking knowledge of the future. Dinan was equidistant from Combourg and Plancoët. I would go in turn to see my uncle De Bedée at Monchoix, and my family at Combourg. Monsieur de Chateaubriand, who sought economy in my upkeep, and my mother who wished me to persist in the religious vocation, but had scruples about urging me, no longer insisted on my residence at college, and I found myself, imperceptibly, a fixture in the paternal home.

I would still take pleasure in recalling my parent’s ways, were they merely a fond memory to me; but I will paint the portrait all the more readily in that it seems as if traced precisely from the vignettes in medieval manuscripts: between the present time and the time I am going to depict centuries have elapsed.

End of Book II