François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book VIII: Kentucky, Virginia, Return to France 1791-1792

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book VIII: Chapter 1: The Lakes of Canada – A fleet of Indian canoes – The history of the rivers

- Book VIII: Chapter 2: The Course of the Ohio

- Book VIII: Chapter 3: The Fountain of Youth – Muskogees and Seminoles

- Book VIII: Chapter 4: Two Floridian Women

- Book VIII: Chapter 5: The nature of the young Musgokee ladies – The King’s arrest at Vincennes – I interrupt my travels to return to Europe

- Book VIII: Chapter 6: Potential risks for the United States

- Book VIII: Chapter 7: Return to Europe - Shipwreck

Book VIII: Chapter 1: The Lakes of Canada – A fleet of Indian canoes – The history of the rivers

London, April to September 1822. (Revised December 1846)

BkVIII:Chap1:Sec1

The little beaded girl’s tribe departed; my guide, the Dutchman, refused to accompany me beyond the cataract; I paid him off, and joined some traders who were leaving to travel down the Ohio; before leaving I took a look at the Canadian lakes. Nothing is as sad as the aspect of those lakes. The expanses of the Ocean and the Mediterranean open up a path for nations, and their shores are or were inhabited by civilised peoples, numerous and powerful; the Canadian lakes reveal only the nakedness of their waters, which meet an unclothed land once more: solitudes which separate further solitudes. Uninhabited coastlines gaze at seas without vessels; you land on deserted shores from empty waves.

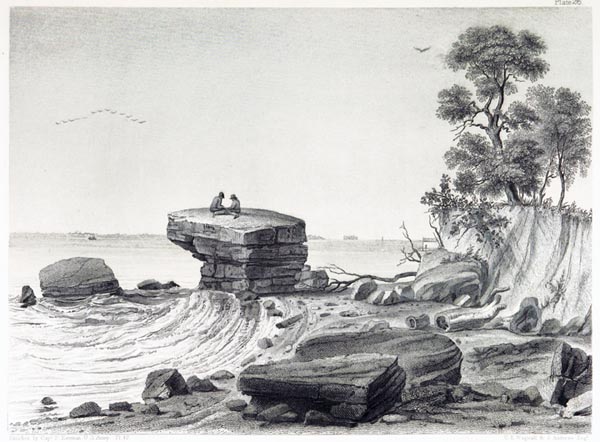

‘View of Inscription Rock on South Side of Cunningham's Island, Lake Erie’

The Indian Tribes of the United States - Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (p181, 1891)

The British Library

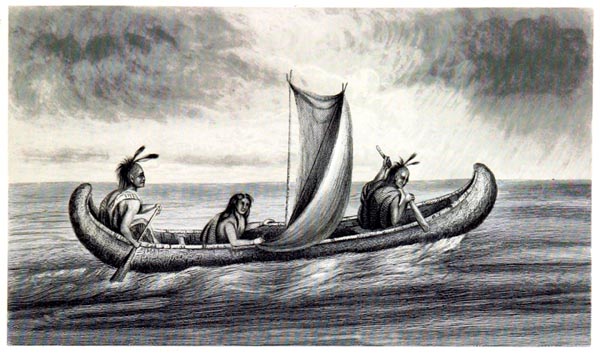

Lake Erie is more than thirty miles long. The nations of the lakeshore were exterminated by the Iroquois, two centuries ago. It is a terrifying thing to see the Indians venture out in bark canoes onto the lake, renowned for its storms, where myriads of serpents once swarmed. These Indians hang their manitous (objects possessing supernatural powers) from the stern of their canoes, and dash into the midst of the whirlpools among the towering waves. The water, level with the sides of the canoes, seems ready to swallow them. The hunting dogs bay, their paws resting on the gunnels, while their masters, keeping a profound silence, strike the waves in unison with their paddles. The canoes advance in line: at the lead prow stands a chief who repeats the diphthong oah; o on a long soft note, a in a short shrill tone. In the last canoe is another chief, who is also standing and handling an oar, shaped like a tiller. The other braves are crouched on their heels inside the boats. Through the breeze and mist, one can see only the feathers with which the Indians heads are adorned, the outstretched necks of the howling mastiffs, and the shoulders of the two sachems, the pilot and augur: they look like the gods of these lakes.

‘Ottowa Canoe’

The Indian Tribes of the United States - Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (p91, 1891)

The British Library

The Canadian rivers lack the history of the old world; the fate of the Ganges, Euphrates, Nile, Danube and Rhine is otherwise. What changes have they not seen on their banks! What blood and sweat have conquerors not shed, on their journeys to traverse those waves that a goatherd at the source can step across!

Book VIII: Chapter 2: The Course of the Ohio

London, April to September 1822.

BkVIII:Chap2:Sec1

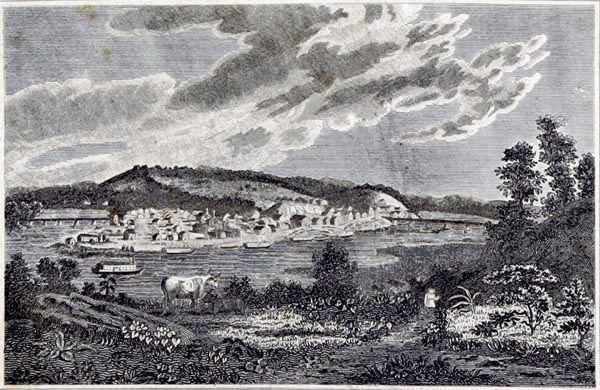

Leaving the Canadian lakes, we came via Pittsburgh to the confluence of the Kentucky and the Ohio; there, the landscape displays an extraordinary grandeur. This country of such magnificence is nevertheless called Kentucky from the name of its river which signifies river of blood. It owes its name to its beauty: for more than two centuries, the nations siding with the Cherokees and those siding with the Iroquois nations have been in dispute over the hunting grounds.

‘Pittsburgh’

The Western Pilot; Containing Charts of the Ohio River, and of the Mississippi, from the Mouth of the Missouri to the Gulf of Mexico - Samuel Cumings (p18, 1832)

The British Library

Will European generations be more virtuous and free on those shores than the lost generations of Americans? Will slaves not plough the earth beneath their masters’ whips, in those wildernesses of man’s primitive independence? Will prisons and gibbets not replace the open hut and the tall tulip tree where the bird makes it nest? Will the rich soil not give rise to new wars? Will Kentucky cease to be the field of blood, and works of art more beautiful than the works of nature adorn the banks of the Ohio?

Having passed the Wabash, the Great Cypress grove, the Winged or Cumberland River, the Cherokee or Tennessee River, and the Yellow Banks, one reaches a tongue of land often drowned by the vast waters; there the Ohio merges with the Mississippi at 36 degrees 51 minutes latitude. The two rivers meet, while an equal resistance slows their course; they slumber against each other in the same channel, without merging, for a few miles, like two great nations separated at their source, then joined to create a single race; like two illustrious rivals sharing the same resting place after a battle; like a married couple, of opposing blood, who at first had little inclination to unite their destinies in the nuptial bed.

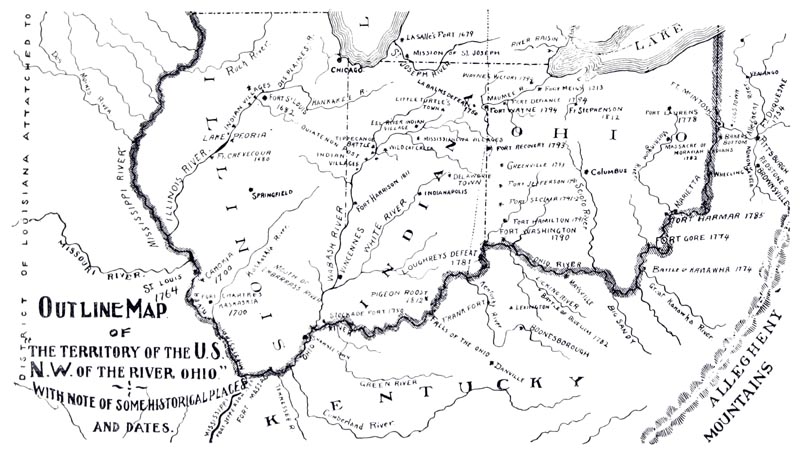

‘Outline Map of the Territory of the U.S. N.W. of the River Ohio’

Conquest of the Country Northwest of the River Ohio, 1778-1783, and life of Gen. George Rogers Clark - William Hayden English (p197, 1896)

The British Library

And I too, like the powerful flow of the rivers, have extended the little course of my life, now on one side of the mountain, now on the other; capricious in my mistakes, never wicked; preferring the bare valleys to the rich plains, halting by flowers rather than palaces. Moreover, I was so delighted by my travels, that I scarcely thought any more of the Pole. A company of traders off to visit the Creek Indians, in the Floridas, allowed me to travel with them.

We were headed for the region known at that time under the general name of the Floridas, now occupied by the states of Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina and Tennessee. There, we would more or less follow the trails that now link the grand route from Natchez to Nashville, through Jackson and Florence, with that which in Virginia, runs through Knoxville and Salem: a region little frequented at this time, but whose lakes and sites of interest Bartram had explored. The planters of Georgia and the maritime Floridas came to the various tribes of Creeks to buy horses and half-savage cattle that bred extensively in the savannahs (treeless plains) which are pierced by those well-springs on whose banks I placed Atala and Chactas. They extend even as far as the Ohio.

We were urged on now by a fresh breeze. The Ohio, swollen by a hundred rivers, now lost itself in lakes that opened before us, now in forest. Islands rose from the midst of the lakes. We sailed towards one of the largest: we landed there at eight in the morning.

I crossed a meadow dense with yellow-flowering ragwort, pink-headed hollyhocks, and abelias with purplish blooms.

An Indian ruin caught my attention. The contrast between this ruin and virgin nature, this human monument in a wilderness, caused me great emotion. What people had lived on this island? What had been their name, and race, the length of their stay? Did they still exist, as the world in whose breast they were hidden existed unknown to three quarters of the earth? The silence of that people is contemporary perhaps with the noise of great nations fallen to silence in their turn. (The ruins of Mitla and Palenque in Mexico, show today that the New World can dispute its antiquity with the Old: Note, Paris 1834)

The sandy crevices, of their ruins or tumuli, sported poppies, with red petals hanging from the tip of a peduncle tending to pale green. The stem and the flower had a scent which stayed on the fingers when one had touched the plant. The perfume of this flower remains, as a symbol of the memory of a life passed in solitude.

I observed a water-lily: it was preparing to hide its white bud in the water, at the day’s end; the weeping shrub (nyctanthe: gardenia or Malabar jasmine) waits for night to reveal itself: the wife goes to her rest at the hour when the courtesan rises.

The pyramidal oenothera (evening primrose), seven or eight feet high, with oblong greenish-black jagged leaves has another manner of behaving and another fate: its yellow flowers begin to half-open in the evening, in the space of time it takes Venus to descend below the horizon; it continues to open in starlight; dawn finds it in all its splendour; half-way through the morning it fades; it dies at midday. It only lives a few hours; but it passes those hours under a serene sky, between the sighs of Venus and dawn; what matter then the brevity of that life?

A stream is embowered with Venus fly-traps; a multitude of dragonflies buzz around. There are also hummingbirds and butterflies which, in their most glittering jewellery, joust brilliantly with iridescent flowers. In the midst of my wandering and my studies, I was often struck by their futility. What! Could the Revolution, which always weighed on me and which had driven me into the woods, inspire me with nothing more serious? What! During those days of upheaval in my native country, could I occupy myself with nothing more than descriptions of plants, butterflies and flowers? Human individuality serves to measure the littleness of the greatest events. How many men are indifferent to those same events? How many other men are ignorant of them? The total population of the globe is estimated to be eleven or twelve hundred million; a human being dies every second: so in every minute of our existence, of our smiles, our joys, sixty expire, sixty families mourn and weep. Life is a continual plague. This chain of bereavement and funerals that winds us about, never breaks, it lengthens; we ourselves form a link. And then we magnify the importance of those catastrophes of which seven-eighths of the world heard not a word! Let us hanker after a fame that will not vanish a few miles from our grave! Let us plunge into an ocean of bliss where each minute flows among sixty coffins continually re-filled!

‘Nam nox nulla diem, neque noctem aurora secuta est,

Quae non audierit mixtos vagitibus aegris

Ploratus, mortis comites et funeris atri.’

‘No night has followed day, no dawn has followed night, in which tears and mournful sounds of grief have not been heard, the companions of death and dark funerals.’

Book VIII: Chapter 3: The Fountain of Youth – Muskogees and Seminoles

London, April to September 1822.

BkVIII:Chap3:Sec1

The savages of Florida say that in the midst of a lake there is an island where the loveliest women in the world live. The Muskogees have tried to conquer it on many occasions; but this Eden flees before their canoes, a natural symbol of those dreams which retreat before our desires.

That land also boasted a Fountain of Youth: but who would wish to live again?

These fables almost took on a kind of reality to my eyes. At the moment when we least expected it, we saw a fleet of canoes emerge from a bay, some with oars others with sails. They carried two families of Creeks, one of Seminoles, the other of Muskogees, among which were Cherokees and Burnt-woods. I was struck by the grace of these savages who in no way resembled those of Canada.

The Seminoles and Muskogees are quite tall, and yet, in amazing contrast, their mothers, wives and daughters are, in America, the smallest women known.

The Indian women who landed near us, of mixed Cherokee and Castilian stock, were tall in stature. Two of them looked like the Creoles of San Domingo and Mauritius, but yellow-skinned and delicate like women of the Ganges. These two Floridian women, cousins on the father’s side, served me as models, one for Atala, the other for Céluta: they surpassed the portraits I painted of them only by that variable and fugitive truth of nature, that physiognomy of race and climate, which I could not render. There was something indefinable in the oval face, the dusky complexion that one seemed to see through light, orange coloured smoke, the hair so black and soft, the lengthened eyes, half-hidden beneath the veil of two satiny eyelids which half-opened lazily; in short in the dual attraction of the Indian and the Spanish woman.

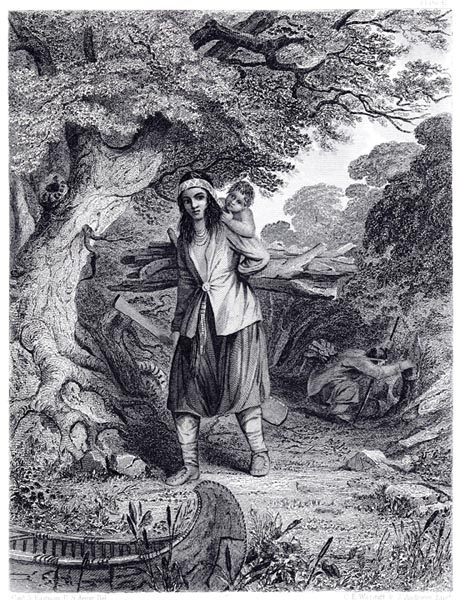

‘Indian Women Procuring Fuel’

The Indian Tribes of the United States - Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (p275, 1891)

The British Library

The meeting with out hosts somewhat altered our movements; our trading agents started to enquire about horses: it was decided that we should go and install ourselves near the studs.

The plain where we camped was full of bulls, cows, horses, bison, buffalo, cranes, turkeys and pelicans: the birds mottled the green backcloth of the savannah with white, black and pink.

Our traders and trappers were agitated by many passions: not passions of race, education or prejudice, but natural passions, direct and full-blooded, and they made straight for their goal, their course witnessed only by a tree falling in the depths of an unknown forest; an uncharted valley, a nameless river. The relations between the Spaniards and the Creek women formed the basis of their adventures: The Burnt-woods played the principal part in these romances. One story was celebrated, that of a dealer in brandy, seduced and ruined by a painted woman (a courtesan). This story put into Seminole verse under the title of Tabamica, was sung on the trail through the woods. Carried off in turn by the settlers, the Indian women soon died of neglect at Pensecola: their misfortunes went to enhance the Romanceros and be classed with Ximena’s laments.

Book VIII: Chapter 4: Two Floridian Women

London, April to September 1822.

BkVIII:Chap4:Sec1

What a delightful mother Earth is; we issue from her womb: in childhood, she holds us to her breasts swollen with milk and honey; in youth and maturity, she lavishes on us her cool waters, harvests and fruits; she offers us everywhere shade, a bath, a table, a bed; at our death, she opens her womb to us again, throwing a covering of grass and flowers over our remains, while she secretly transmutes us into her own substance, to recreate us in some graceful form. That is what I said to myself on waking, as my first glance met the sky, the canopy above my resting place.

The hunters had left for their day’s work, and I was left behind with the women and children. I never strayed far from my two wood-nymphs: the one was proud, the other sad. I understood not a word of what they said to me, nor did they understand me; but I went to fetch water for them to drink, twigs for their fire, and moss for their bed. They wore the short skirts and wide slashed sleeves of Spanish women, with Indian bodices and cloaks. Their bare legs were criss-crossed in lozenge shapes with strips of birch. They plaited their hair with garlands of flowers or threaded rushes; they strung themselves with chain and glass necklaces. In their ears hung crimson berries; they had a pretty talking parrot: the bird of Armida; they fastened it on their shoulder like an emerald, or carried it hooded at their wrist as the great ladies of the tenth century carried their hawks. To firm up their breasts and arms, they rubbed themselves with apoya or American sedge. The dancing-girls of Bengal, the bayadères, chew betel-nut, while those of the Levant, the Egyptian almes, suck the gum mastic of Chios; the Floridian women crushed, between their bluish-white teeth, tears of liquidambar and roots of libanis (alkanet), which combined the fragrances of angelica, citron, and vanilla. They lived in a perfumed atmosphere that originated from them, as orange trees and flowers do in the pure emanations of their leaves and buds. I amused myself by placing little adornments in their hair: they submitted, though slightly alarmed; sorceresses themselves, they thought I was casting a spell on them. One of them, the proud one, prayed frequently; she seemed half-Christianised to me. The other sang in a velvet voice, ending each musical phrase with a moving cry. Sometimes, they spoke sharply to each other: I thought I detected the accents of jealousy, but the sad one wept, and silence was restored.

Affected, as I was, I sought examples of affection to cheer myself. Had not Camoëns, in the Indies, loved a black slave of Barbary, and could not I in America offer homage to two young yellow-skinned Sultanas? Had not Camoëns addressed his Endechas, or lyric songs, to Barbara esclava (a barbarian slave-girl)? Did he not write?

‘A quella captiva,

Que me tem captivo,

Porque nella vivo,

Já naõ quer que viva.

Eu nunqua vi rosa

Em soaves mõlhos,

Que para meus olhos

Fosse mais formosa.

Pretidaõ de amor,

Taõ doce a figura,

Que a neve lhe jura

Que trocára a cõr.

Léda mansidaõ,

Que o siso acompanha:

Bem parece estranha,

Mas Barbara naõ.

‘This slave, who enslaves me, since I live for her, spares not my life. Never a rose in the sweetest bouquet, struck my eyes as more charming. Her dark hair inspires love; her face is so lovely the snow desires to exchange its colour with her; her gaiety is accompanied by restraint: she is a foreigner: but a barbarian, no.’

BkVIII:Chap4:Sec2

A fishing party was organised. The sun had almost set. In the foreground were sassafras, tulip-trees, catalpas, and oaks from whose boughs hung skeins of white moss. In the near background rose the most delightful of trees, the papaw, that might have been taken for a stylus of chased silver, topped by a Corinthian urn. In the far background balsam-trees, magnolias and liquidambars proliferated.

‘A View of Inscription Rock’

The Indian Tribes of the United States - Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (p81, 1891)

The British Library

The sun sank behind this scene: a ray fell across the domed crown of a group of tall trees, shedding its glow like a mounted ruby through the sombre foliage; the light spread among the trees and branches, throwing divergent columns and mobile arabesques on the grass. Below, were lilacs, azaleas, annulated creepers, in gigantic sprays; above, clouds, some stationary promontories or ancient turrets, others floating by, as pink smoke or silken flakes. In successive transformations, one saw furnaces gape open in these clouds, heaped piles of embers, flowing rivers of lava: all was brilliant, radiant, gilded, opulent, and saturated with light.

After the insurrection in the Morea in 1770, families of Greeks fled to Florida: they might have believed themselves still in that Ionian climate, which seems to be softened by human passions: at Smyrna, in the evening, nature sleeps like a courtesan wearied by love.

To our right were ruins belonging to the great fortified mounds found on the Ohio, to our left an ancient camp of savages; the island on which we stood, fixed in the water, and reproduced by a mirage, hovered before us in double perspective. In the east, the moon rested on distant hills; in the west the sky’s vault had melted into a sea of diamonds and sapphires, in which the sun half-buried, seemed to dissolve. The creatures of creation kept watch; the earth in adoration seemed to scatter incense over the sky, and the perfume of ambergris she exhaled from her breast fell back towards her as dew, as prayers descend again over those who pray.

Abandoned by my companions, I rested beside a mass of trees: its shadows, glazed with light, formed a penumbra in which I sat. Fireflies shone among the dark shrubs, and were eclipsed when they passed through the moonbeams. The sound of the lake ebbing and flowing could be heard, the golden fish leaping, and the occasional cry of a diving-bird. My gaze was fixed on the water; I gradually slid into that drowsiness familiar to those who travel the world’s highways: I lost all clarity of recollection; I felt myself to be living and vegetating with nature in a kind of pantheism. I leant against the trunk of a magnolia tree and fell asleep; my repose floated on some vague depth of hope.

When I emerged from this Lethe, I found myself between two women; the odalisques had returned; they had not wished to wake me, and had seated themselves silently by my side; then either feigning sleep, or really falling into a doze, their heads had drooped onto my shoulders.

A breeze blew through the grove and deluged us with a shower of magnolia petals. Then the younger of the Seminoles began to sing: if a man is unsure of himself he should never allow himself to be exposed to such temptation! One cannot say what passion may penetrate his heart with the melody. A harsh jealous voice responded to this voice: a Burnt-wood called to the two cousins; they started, and rose: dawn was beginning to break.

Though lacking Aspasia, I have often repeated this scene on the shores of Greece: climbing at dawn to the colonnade of the Parthenon, I have seen Mount Cithaeron, Mount Hymettus, the Acropolis of Corinth, the tombs and ruins bathed in a golden dewy light, transparent and shimmering, reflected by the waters, and wafted on the breezes from Salamis and Delos like perfume.

We finished our wordless voyage on the bank. At noon, we struck camp to visit and examine the horses that the Creeks wished to sell and the traders to buy. Women and children, all were summoned as witnesses, according to the custom of these solemn transactions. Stallions of every age and colour, foals and mares, and also bulls, cows and heifers, began racing and galloping around us. In the confusion, I was separated from the Creeks. A dense crowd of men and horses collected at the edge of a wood. Suddenly, I recognised my two Floridians amongst them; vigorous arms were seating them on the cruppers of two Barbary horses ridden bareback by a Burnt-Wood and a Seminole. O Cid! If only I had possessed your swift Babieca to rejoin them! The mares took flight, and the vast squadron followed suit. The horses galloped, reared and bounded, neighing among the horns of bulls and buffalos, their hoofs clashing in mid-air, bloodstained manes and tails flying. A whirlwind of ravenous insects enveloped this wild cavalry circle. My Floridians disappeared from view, as Ceres’ daughter vanished, snatched away by the god of the underworld.

That is how everything in my life proves abortive, and why nothing is left to me but images of what has flashed by: I will descend to the Elysian Fields with more shades than any man has ever taken with him. The fault lies in my character: I do not know how to profit from good fortune; I am not interested in anything which interests others. Except in religion, I have no beliefs. Shepherd or king, what would I have done with a sceptre or a crook? I would have grown equally tired of glory or genius, work or leisure, prosperity or misfortune. Everything wearies me: I can scarcely drag my ennui through the days, and everywhere I go I yawn away my life.

Book VIII: Chapter 5: The nature of the young Musgokee ladies – The King’s arrest at Vincennes – I interrupt my travels to return to Europe

BkVIII:Chap5:Sec1

Ronsard pictured Mary Stuart for us, ready to depart for Scotland after the death of François II:

‘You were dressed in such finery

Leaving, alas, that sweet country

(Whose sceptre you had held so fast)

Thoughtful now, bathing your breast,

In your fine crystal flow of tears,

Sad, as you walked the alleys there

Of the great garden of that royal chateau,

Whose name derives from a fountain’s flow.’

Did I resemble Mary Stuart wandering the paths of Fontainebleau, as I wandered in the savannah after this separation? What is certain is that my spirit, if not my body, was enveloped by ‘a veil, long, subtle and fine’ as Ronsard said, that old poet adopted by the new school.

The devil having carried off the two young Muskogee ladies, I learnt from the guide that a Burnt-Wood, in love with one of the two girls, had proved jealous of me, and had decided, with the help of a Seminole, the brother of the other cousin, to snatch Atala and Céluta from me. The guides, quite bluntly, called them painted women, which shook my pride. I felt myself to be all the more humiliated in that the Burnt-Wood, my favoured rival, was a mosquito, lean, dark and ugly, having all the characteristics of those insects which, according to the definition of the Grand Lama’s entomologists, are creatures whose flesh is internal, and bones external. The wilderness seemed empty after my misadventure. I gave a sour welcome to my sylph, nobly rushing to console a faithless lover, as Julie forgave Saint-Preux his Parisian Floridians. I hastened to leave the wilds, where I have since recreated my drowsy companions of that night. I do not know if I have repaid them for the moments of life they granted me; at least, I made a virgin of one, and a chaste wife of the other, in expiation.

We re-crossed the Blue Mountains, and approached the European clearings near Chillicoth. I had not shed any light on the principal object of my travels; but I was accompanied by a world of poetry:

‘From the roses’ depths, like a new-hatched bee,

My Muse returned, with new spoils, to me.’

On the banks of a stream I noticed an American house, a farm at one end, a water-mill at the other. I entered, asked for food and shelter, and was well-received.

My hostess led me up a ladder to a room above the shaft of the mill’s hydraulic mechanism. My little window, festooned with ivy and cobaea (a Mexican climbing vine) with purple bell-flowers, overlooked the stream which flowed narrow and solitary, between two thick borders of willows, elms, sassafras, tamarinds and Carolina poplars.

The mossy wheel turned beneath their shade, letting fall long ribbons of water. Perch and trout leaped in the swirling foam; wagtails flew from bank to bank, and a species of kingfisher flickered on blue wings above the flow.

How happy I might have been there with the sad girl, supposing she were faithful, sitting dreaming at her feet, my head resting against her knees, listening to the noise of the weir, the revolutions of the wheel, the rolling of the millstone, the sifting of the bolter, the even beat of the clack, breathing the water’s freshness and the fragrance from the husks of pearl-barley?

Night fell. I went down to the farm parlour. It was only lit by a blaze of maize straw and bean husks in the hearth. The miller’s firearms, resting horizontally in the gun-rack, shone in the fire-light. I sat down on a stool in the chimney-corner, near a squirrel which kept leaping between the back of a large dog and the shelf of a spinning-wheel. A small cat took possession of my knee to watch this game. The miller’s wife masked the fire with a large cooking pot, whose flames licked its black base like a radiant crown of gold. While the potatoes for my supper boiled under my watchful eye, I passed the time reading in the light of the fire, bowing my head to an English newspaper which lay on the ground between my legs: I saw, printed in large letters, these words: Flight of the King. It was the story of the attempted escape of Louis XVI, and the unfortunate monarch’s arrest at Varennes. The newspaper also told of the on-going emigration and the gathering of army officers to the banner of the French princes.

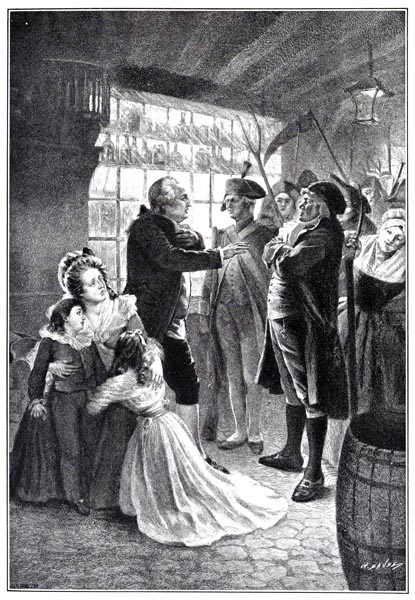

‘The Flight of Louis XVI, Checked at Varennes’

The Story of the Greatest Nations, from the Dawn of History to the Twentieth Century - Edward Sylvester Ellis, Charles Francis Horne (p288, 1900)

Internet Archive Book Images

‘Return of the Royal Family from Varennes’

The History of the French Revolution. Translated by F. Shoberl, Vol 01 - Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p230, 1881)

The British Library

A sudden conversion took place in my mind: Rinaldo saw his frailty in the mirror of honour in Armida’s gardens; whilst not being Tasso’s hero, the same looking-glass showed me my image in an American orchard. The clash of arms, the tumult of the world, echoed in my ears beneath the thatch of a mill hidden in nameless woods. I interrupted the course of my travels, abruptly, saying to myself: ‘Return to France.’

So, what I saw as my duty overthrew my original plans, causing the first of those upheavals that have marked my career. The Bourbons had no need for a younger son from Brittany to return from abroad and offer them his obscure devotion, any more than they have needed his services since he emerged from his obscurity. If I had lit my pipe with the newspaper that changed my life, and gone on with my journey, no one would have noticed my absence; my existence at that time was still invisible, and weighed as little as the smoke from my calumet. A simple dispute between myself and my conscience flung me onto the world stage. I could have done as I pleased, since I was the sole witness to the debate; but of all witnesses, that is the one before whom I most fear to blush.

Why do the solitudes of Erie and Ontario now present themselves to my mind with a charm that my memory of the brilliant spectacle of the Bosphorus lacks? It is because at the time of my voyage to the United States, I was filled with illusions; France’s troubles began at the same moment as my adult life; nothing had yet come to fruition in me, or in my country. Those days are dear to me, because they remind me of the innocent feelings inspired by my family and the delights of youth.

Fifteen years later, after my voyage to the Levant, the Republic, swollen with debris and tears, had flowed like a torrent from deluge into despotism. I no longer deceived myself with chimaeras; my memories, finding their future source in society and the passions, were no longer ingenuous. Disappointed in my pilgrimages to West and East, I had not discovered the passage to the Pole, I had not won glory on the banks of Niagara where I had sought it, and had left rooted among the ruins of Athens.

Leaving to be an explorer in America, and returning to be a soldier in Europe, I failed to complete the course in either career; an evil genie snatched the marshal’s baton and the sword from me, and placed the pen in my hand. Another fifteen years have passed, since in Sparta, gazing at the night sky, I recalled the places that had previously seen my peaceful or troubled sleep: amongst the woods of Germany, on English heaths, on Italian plains, on the high seas, and in the Canadian forests, I had already greeted the same stars I saw shining above the land of Helen and Menelaus. But what did it avail me to complain to the stars, motionless witnesses of my vagrant destiny? One day their gaze will cease to weary itself in following me: meanwhile, indifferent to my fate, I will not ask those stars to exercise a gentler influence over it, nor to offer me whatever of his life the traveller leaves behind in the places he visits.

BkVIII:Chap5:Sec2

If I were to see the United States again, today, I would no longer recognise them: where I left forests, I would find cultivated fields; where I cleared a path through the wilds, I would travel on highroads; among the Natchez, in place of Céluta’s hut, stands a town with around five thousand inhabitants; Chactas today might be a deputy to Congress. I recently received a pamphlet printed among the Cherokees, which is addressed, in the interest of those savages, to me, as a defender of the liberty of the press.

Among the Muskogees, the Seminoles, the Chickasaws there is a new city of Athens, another Marathon, another Carthage, another Memphis, another Sparta, another Florence; you find a District of Columbia, and a county of Marengo: the glory of every country has given its name to those same wilds where I met Father Aubry and the obscure Atala. Kentucky has its Versailles; a territory called Bourbon has Paris as its capital.

All the exiles, all the oppressed who fled to America carried there the memory of their homeland.

.falsi Simoentis ad undam

Libabat cineri Andromache.

(.by the waters of a second Simois,

Andromache made offering to those ashes.)

The United States offer, at their heart, under the protection of liberty, an image and a memory of most of the famous places of antiquity and modern Europe: in his garden in the Roman countryside, Hadrian had the monuments of his empire replicated.

Thirty-three highways leave Washington, as in the past the Roman roads radiated from the Capitol; in their ramifications they reach the circumference of the United States, and trace out a circuit of 25,747 miles. On a great number of these routes, post stations have been set up. You take the stagecoach for Ohio or for Niagara, as in my day you employed a guide or an Indian interpreter. The methods of transport have multiplied: lakes and rivers exist throughout the country, linked together by canals; you can voyage along beside the dirt tracks in boats with oars or sails, or in horse-drawn barges, or in steamboats. Fuel is inexhaustible, since immense forests hide surface coal mines.

The population of the United States increased every ten years, between 1790 and 1820, at a rate of thirty-five per cent. One assumes that by 1830 it will be twelve million eight hundred and sixty-five thousand. If it continues doubling every twenty-five years, in 1855 it will be twenty-five million seven hundred and fifty thousand, and twenty-five years later, in 1880, it will pass fifty million.

That human sap makes every region of the wilderness flower. The Canadian lakes, formerly free of sails, today resemble dockyards, where frigates, corvettes, cutters, and barks, encounter Indian dugouts and canoes, as the great ships and galleys mingle with pinks, rowboats and caiques in the waterways of Constantinople.

The Mississippi, the Missouri, and the Ohio are not left to flow in solitude: three-masters sail them; more than two hundred steam-boats enliven their shores.

This immense interior navigation system, which was alone enough to ensure the prosperity of the United States, does not inhibit them from distant voyages. Their vessels sail on every sea, indulge in every kind of trade, flying the star-spangled banner of the west, along those rivers of the east which have never known servitude.

To complete this amazing picture, their cities must be represented, such as Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston, Savannah, New Orleans, brilliant at night, full of horses and coaches, adorned with cafes, museums, libraries, dance-halls and theatres, offering all the delights of luxury.

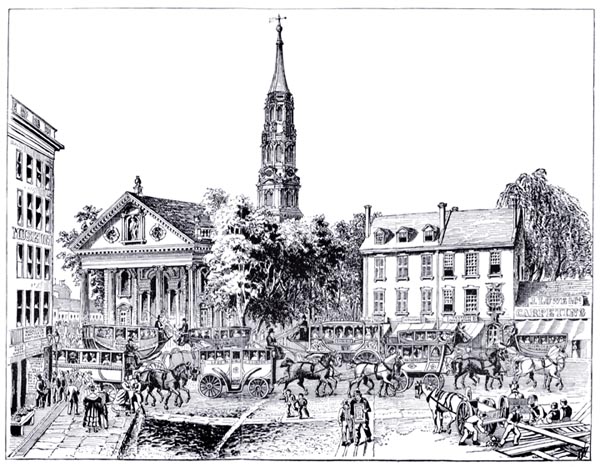

‘Broadway Stages’

The Story of the City of New York - Charles Burr Todd (p479, 1888)

The British Library

BkVIII:Chap5:Sec3

However, it is no use seeking in the United States that which distinguishes man from the other creatures of creation, that which is his share of immortality and the ornament of his days: literature is unknown in the new Republic, though it may have been called for by a host of organisations. The American has replaced intellectual action with direct action; do not attribute his mediocrity in the arts to any inferiority, since he has not directed his attention to that sphere. Flung by various forces onto uncultivated soil, agriculture and commerce have been his projects of necessity; before reflecting, one must live; before planting trees, one must fell them, in order to plough. The first colonists, their minds full of religious controversy, carried, it is true, passionate dispute into the heart of the forests; but they were first forced to go and conquer the wilderness, axe on shoulder, having for pulpit, in the interval between their labours, only the elm they were hewing. Americans have not passed through all the stages of history of other nations; they have left behind in Europe their childhood and youth; the naive babbling of the cradle was unknown to them; they have only been able to enjoy the sweetness of home through their regret for a homeland they have never seen, mourning the eternal absence of charms of which they have been told.

In the new continent there is no classic literature, no romantic literature, and no Indian literature: as to the classics, Americans have had no Middle Ages; as to the Indians, Americans scorn the savages and have a horror of the woods as if they were a prison to which they were destined.

So, there is then no separate literature, literature as properly identified, to be found in America: it is applied literature, the servant of various social needs; it is the literature of workmen, merchants, sailors, ploughmen. Americans barely succeed other than in engineering and the sciences, because the sciences are a material field of study: Franklin and Fulton seized on electricity and steam as useful to mankind. It has fallen to America to acquaint the world with the discovery by means of which no continent henceforth can escape the search of navigators.

Poetry and imagination, shared by a very small number of idlers, are regarded in the United States as are the childishness of the first and last ages of life: Americans have never experienced childhood: they have not yet known old age.

From this it follows that those men engaged in serious study have necessarily had to be involved in the affairs of their country in order to acquire knowledge of it, and that they have likewise been forced to be agents of revolution. But a sad thing is to be noted: the swift decline of talent, between the first men to be involved in America’s unrest, and the men of the present day; and yet these men have been in contact. The first Presidents of the Republic had simple, religious, noble and calm characters, which one finds no trace of in the bloody fracas of our Republic and Empire. The wilderness with which Americans were surrounded has affected their nature; they achieved their liberty in silence.

The farewell speech General Washington addressed to the people of the United States might have been made by one of the gravest characters in history:

‘How far in the discharge of my official duties,’ said the General, ‘I have been guided by the principles which have been delineated, the public records and other evidences of my conduct must witness to you and to the world. To myself, the assurance of my own conscience is, that I have at least believed myself to be guided by them. Though, in reviewing the incidents of my administration, I am unconscious of intentional error, I am nevertheless too sensible of my defects not to think it probable that I may have committed many errors. Whatever they may be, I fervently beseech the Almighty to avert or mitigate the evils to which they may tend. I shall also carry with me the hope that my country will never cease to view them with indulgence; and that, after forty five years of my life dedicated to its service with an upright zeal, the faults of incompetent abilities will be consigned to oblivion, as myself must soon be to the mansions of rest.’

Jefferson, in his house at Monticello, wrote, after the death of one of his two children:

‘The loss I have sustained is truly great. From others may be taken what they possess in abundance; but I, of my simple store, I have to regret the half. The decline of my days is supported only by the feeble thread of a human life. Perhaps I am destined to see this last tie of a father’s affection broken!’

Philosophy, rarely touching, is here in sovereign degree. And it is not the inessential grief of a man who was uninvolved with things: Jefferson died on the 4th July 1826, in his eighty-fourth year, and the fifty-fourth year of his country’s independence. His remains rest, covered by a stone, with an epitaph that contains the words: ‘Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of American Independence.’

Pericles and Demosthenes had pronounced the funeral oration of young Greeks fallen for the sake of a people that vanished soon after them: Brackenridge, in 1817, celebrated the death of young Americans whose blood had given birth to a people.

There is a four-volume octavo ‘national gallery’ of portraits of distinguished Americans, and what is most remarkable is that it contains biographical material on over a hundred of the principal Indian chiefs. Logan, chief of the Mingos, uttered these words, to Lord Dunmore: ‘Colonel Cresap, last spring without provocation murdered all the relatives of Logan.there runs not a drop of my blood in the veins of any living creature. This it is that has called on me for vengeance. I have sought it; I have killed many. Who is there to mourn for Logan? Not one.’

Without loving Nature, Americans have applied themselves to the study of natural history. Townsend, starting from Philadelphia, has journeyed on foot through the regions which separate the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Thomas Say, traveller in the Floridas and the Rocky Mountains, has given us a work on American entomology. Wilson, weaver become author, has published his part-finished engravings.

Speaking now of true literature, however slight it may be, there are a few writers to mention perhaps, among the novelists and poets. The son of a Quaker, Brown, is the author of Wieland, which is the source and model for novels of the new school. As opposed to his compatriots: ‘I would rather,’ says Brown, ‘wander through the forests than thresh corn.’ Wieland, the hero of the novel, is a Puritan whom the Deity has commanded to kill his wife: ‘“I brought thee hither,”’ he says ‘“to fulfil a divine command. I am appointed thy destroyer, and destroy thee I must.” Saying this I seized her wrists. She shrieked aloud, and endeavoured to free herself from my grasp. “Wieland. Am I not thy wife? And wouldst thou kill me? Thou wilt not. Spare me – spare.” Till her breath was stopped she shrieked for help – for mercy.’ Wieland strangles his wife and experiences ineffable delight by the dead body. The horror of our modern inventions is here surpassed. Brown was influenced by reading Caleb Williams, and in Wieland he imitates a scene from Othello.

Today, the American novelists, Cooper and Washington Irving, are forced to take refuge in Europe to find a publisher and a public. The language of the great English writers is creolized, provincialized, barbarized, without gaining anything in vigour in the midst of virgin nature; they have been obliged to draw up catalogues of American expressions.

As for American poets, their language is agreeable; but they amount to little more than the common run. However, Ode to the Evening Breeze, Sunrise on the Mountain, The Torrent, and a few other poems merit attention. Halleck has sung of the dying Bozzaris, and George Hill has wandered among the ruins of Greece: ‘O Athens!’ he writes, ‘t’is you then, solitary Queen, Queen dethroned! ...Parthenon, king of temples, you have seen monuments, contemporary with you, let time denude them of their priests and gods.’

It pleases me, a traveller myself to the shores of Hellas and Atlantis, to hear the independent voice of a land unknown to antiquity mourning the old world’s lost liberty.

Book VIII: Chapter 6: Potential risks for the United States

BkVIII:Chap6:Sec1

But will America maintain its form of government? Will the States dissolve? Has not a deputy from Virginia already supported the concept of ancient liberty, co-existent with slavery the product of paganism, against a deputy from Massachusetts, defending the cause of modern freedom without slavery, such as Christianity has engendered?

Are not the northern and southern States opposed in spirit and interest? Would not the western States, so far from the Atlantic, prefer a separate regime? Besides, if the power of the Presidency is increased, will despotism not appear with the protections and privileges of dictatorship?

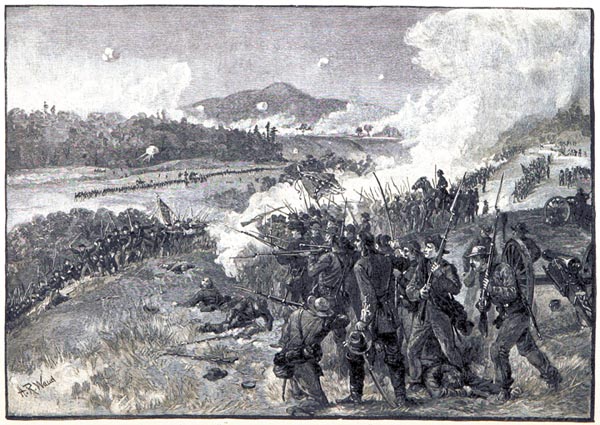

‘The Battle of Resaca, Georgia’

Battles and Leaders of the Civil War - Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel (p286, 1887)

The British Library

The isolation of the United States has permitted their birth and growth: it is doubtful whether they could have survived and flourished in Europe. The Swiss Federation exists in our midst: why? Because it is small, poor, a cluster of cantons in the heart of the mountains: a nursery of soldiers for kings, the object of walks for travellers.

Separated from the ancient world, the population of the United States still inhabits a wilderness; its wilds have guaranteed its freedom: but already its conditions of existence are altering.

The presence of democracies in Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Chile, Buenos Aires, unstable as they are, is a danger. While the United States had nothing closer to them than the colonies of a transatlantic kingdom, any kind of serious conflict was unlikely; is rivalry not now the greatest fear? When there is a rush to arms on all sides, when the military spirit grips those children of Washington, a great leader might rise to the throne: glory loves crowns.

I have said the northern, southern and western States have divided interests; each knows it: shattering the union, will they dissolve it by force of arms? Then, what can quell the enmities that spread through the body politic! Will the dissident States assert their independence? Then, what discord will not erupt among those emancipated States! Those republics beyond the seas, decoupled, will form mere debilitated atoms of no weight in the social balance, or will be successively subjugated by one amongst them. (I set aside the difficult question of alliances and foreign intervention). Kentucky, inhabited by a more rural, tougher, more military people, seems destined to be the conquering State. In that State which shall devour the others, the power of one will soon rise above the ruins of the power of all.

I have spoken of the danger of war: I must mention the dangers of a lengthy peace. The United States, since their emancipation, have enjoyed, except for only a few months, the most profound tranquillity: while a hundred battles embroiled Europe, they cultivated their fields in harmony. From that came an increase in population and wealth, with all the disadvantages of a surplus of wealth and population.

If hostilities occur in a peaceable nation, how will they be countered? Will riches and custom be ready to make sacrifices? How to forego life’s tender usages, comforts, and indolent well-being? China and India, cushioned in silk, have constantly been subject to foreign domination. What suits the constitution of a free society is a state of peace tempered by war, and a state of war moderated by peace. The Americans have already borne the olive wreath for too long: the tree which provides it is not native to their shores.

The mercantile spirit is beginning to possess them; self-interest with them is becoming a national vice. Already, the interplay among the banks of various States is hindering them, and bankruptcies threaten the communal wealth. As long as freedom makes money, an industrialised republic performs prodigies; but when the money is spent or exhausted, it loses its love of that liberty not founded on moral feeling, but rising from the thirst for profit and a passion for industry.

Moreover, it is difficult to create a country from States which have no community of religion or interests, which, arising from diverse sources at diverse times, exist on different soils and under different suns. What connection is there between a Frenchman from Louisiana, a Spaniard from the Floridas, a German from New York, or an Englishman from New England, Virginia, the Carolinas, or Georgia, all supposed Americans? This one is a nimble duellist; that one is Catholic, idle and proud; this one is a Lutheran, a ploughman owning no slaves; that one a Puritan merchant; how many centuries would it take to render these elements homogenous!

An aristocratic capitalist is ready to emerge, in love with distinctions and with a passion for titles. One might imagine that there is only one common class in the United States: that is a complete error. There are social groupings which scorn each other and never appear together; there are salons where the haughtiness of the host surpasses that of a German prince with sixteen quarters in his coat of arms. These noble plebeians aspire to caste, despite the progress made by the enlightened men who made them free and equal. Some of them speak of nothing but their ancestry, proud barons, bastards apparently and companions of William the Bastard. They display blazons of chivalry from the old world, decorated with snakes, lizards and parakeets from the new. A younger son from Gascony, landing with cloak and umbrella on the Republican shore, if he takes care to call himself marquis, is well thought of on the steamboats.

The enormous inequalities of wealth are an even more serious threat to the spirit of equality. Some Americans possess one or two millions in income; also, the Yankees of high society no longer live as Franklin did: the true gentleman, disgusted with the newness of his country, travels to Europe to seek the old; you meet him in the inns, engaged like the English, with extravagance or spleen, on his Italian tour. These prowlers from the Carolinas or Virginia purchase ruined abbeys in France, and plant, at Melun, English gardens full of American trees. Naples sends its singers and perfumers to New York; Paris its fashions and its strolling players; London its bellboys and boxers: exotic delights which make the Union no happier. They amuse themselves there by leaping into Niagara Falls, to the applause of fifty thousand planters, semi-savages that death itself can scarcely make smile.

And what is extraordinary, is that at the same time that inequality of wealth increases and an aristocracy is forming, the great egalitarian impulse beyond them obliges the owners of industry or land to hide their luxury, conceal their wealth, for fear of being set upon by their neighbours. They do not recognise the executive power; they drive out, at will, the local authorities they have chosen, and substitute new authorities for them. It does not disturb the social order; democracy is observed in practice, while they laugh at the laws decreed, in theory, by that same democracy. Family spirit barely exists; as soon as the child is fit for work, he must, like a bird with its feathers, fly with his own two wings. From the emancipated generations swiftly orphaned, and the immigrants arriving from Europe, bands of nomads are created who clear the ground, dig the canals, and exercise their industry everywhere without becoming attached to the soil; they construct houses in the wilderness in which the passing traveller stays for scarcely a few days.

A cold hard egoism rules the towns; dollars and piastres, banknotes and cash, the rise and fall of stocks, is the whole of their conversation; you would imagine yourself in the Bourse, or the counting-house of some great store. The newspapers, of huge dimensions, are full of business discussions or coarse prattle. Do Americans suffer, without knowing it, the laws of a climate where vegetable nature seems to have profited at the expense of animal nature, a law opposed by distinguished men, but whose refutation has not been put absolutely beyond question? One might enquire if the American has not become used too early to philosophic freedom, as the Russian to civilised despotism.

In summary the United States give the impression of a colony and not a mother-country: they have no past, their customs have been created by laws. These citizens of a New World took their place among the nations at the moment when political ideas were in the ascendancy: that explains why they transformed themselves at an extraordinary speed. A permanent society seems to have become impractical for them, on the one hand through the extreme ennui of individuals, on the other by the impossibility of remaining in one place, and by the necessity of movement that possesses them: for one is never rooted where the household gods stray. Placed in the path of the oceans, owning progressive opinions as new as his country, the American seems to have received from Colombus a mission aimed more at discovering other universes than creating them.

Book VIII: Chapter 7: Return to Europe - Shipwreck

London, April to September 1822.

BkVIII:Chap7:Sec1

Returning from the wilderness to Philadelphia, as I have already said, and having written on the road, in haste, what I have just related, like La Fontaine’s old man, I failed to find the bills of exchange waiting for me that I had expected; that was the start of the financial difficulties in which I have been submerged throughout my life. Fortune and I took a dislike to each other at first sight. According to Herodotus, certain Indian ants gathered heaps of gold: while Athenaeus claims the sun gave Hercules a golden vessel to carry him to the island of Erytheia, home of the Hesperides: ant though I am, I have not the honour to belong to the great Indian family, and sailor though I am, I have never crossed the sea in other than a wooden barque. It was a boat of this kind that carried me from America back to Europe. The captain allowed me to take passage on credit. On the 10th of December 1791, I embarked, along with several of my countrymen, who, for diverse reasons, were returning as I was to France. The ship’s destination was Le Havre.

A westerly gale caught us at the mouth of the Delaware, and drove us across the Atlantic in seventeen days. Often running under bare poles, we were scarcely able to heave-to. The sun never showed itself. The ship, steered by dead-reckoning, flew before the waves. I crossed an ocean in shadow; to me it had never looked so sad. I myself, even sadder, was returning disappointed from my first foray into life: ‘One cannot build a palace on the sea,’ says the Persian poet Farid ud-Din. I felt a vague heaviness of heart, as at the approach of a great misfortune. Gazing out over the waves, I asked them to prophesy my fate, or wrote, more troubled by their motion than disturbed by their threat.

Far from dropping, the gale increased in strength the nearer we came to Europe, but with a steady pressure; the uniformity of its rage produced a kind of furious calm in the livid sky and leaden sea. The captain unable to measure the sun’s altitude, was uneasy; he climbed into the shrouds, and swept the horizon with a telescope. A look-out was sent to the bowsprit, another to the top of the mainmast. The sea turned choppy, and the waves changed colour, signs that we were approaching land, but what land?

I spent two nights walking the deck, the waves slapping in the darkness, the wind moaning in the rigging, and the sea leaping as it swept to and fro over the deck; all around us was a riot of waters. Wearied by the buffeting, on the third night I went below early. The weather was foul; my hammock rocked and creaked at the impact of the waves, that breaking over the vessel, shook its very fabric. I soon heard crewmen running from one end of the deck to the other, and coils of rope being hurled down: I experienced the motion one feels when a ship begins to tack. The hatch over the betweens-deck ladder was opened, and a terrified voice called for the captain: that voice, in the midst of night and tempest sounded dreadful. I strained my hearing; I thought the sailors were discussing the cast of the coast. I leapt from my hammock; a wave broke into the stern castle, flooding the captain’s cabin, overturning tables, beds, chests and firearms, and rolling them about pell-mell; I gained the deck, half-drowned.

As my head emerged from the hatchway, I was struck by a sublime sight. The ship had tried to put about; but unable to accomplish it, had been embayed by the wind. By the light of the half-moon, which sailed out of the clouds only to plunge into them again, we could see, through the yellow fog, a coast bristling with rocks, on either side of the ship. The sea was swollen with mountainous waves, throughout the channel which had swallowed us; now they would blossom in spume and spray; now they would present an oily, vitreous surface, mottled with black, coppery, or greenish stains, according to the colour of the depths over which they roared. For two or three minutes, the moans of the abyss and those of the wind would be confused; a moment after, we could distinguish the swirling currents, the hissing of the reefs, the noise of the distant surge. From the ship’s hold came sounds that made the hearts of the bravest sailors beat faster. The prow of the vessel cut the dense mass of water with a dreadful roar, and torrents of seething water flowed past the rudder, as at the opening of a sluice. In the midst of this uproar, nothing was as alarming as a dull murmur, like that from a vase filling with water.

Lit by a lantern, and held down by weights, sailing-books, charts and log-books were spread out on a chicken-coop. A squall had extinguished the binnacle lamp. Everyone disagreed about the land. We had entered the Channel, without being aware of it; the ship, staggering under every wave, was drifting between Guernsey and Alderney. Shipwreck seemed inevitable, and the passengers grasped hold of whatever valuables they had in order to save them.

There were French sailors among the crew; one of them, in the absence of a chaplain, intoned that hymn to Our Lady of Saving Goodness, the first thing I learnt as a child; I sang it again in sight of the Brittany coast, almost under my mother’s eyes. The American Protestant sailors joined enthusiastically in the hymn sung by their French Catholic messmates: danger teaches men their weakness and unites them in prayer. Passengers and sailors were all on deck, clinging to the rigging, the planking, the capstan, or the anchor flukes, to avoid being swept away by the sea, or hurled overboard by the rolling of the ship. The captain shouted for; ‘An axe! An axe!’ to cut away the masts; and the rudder, its tiller abandoned, swung from side to side, with a harsh creaking sound.

There was one thing left to try: the lead now registered only four fathoms above a sand bank that crossed the channel; it was possible the flood might carry us over the bank and into deep water: but who had the courage to take the helm and take charge of our common safety? One false turn of the tiller, and we were done for.

One of those men thrown up by the course of events, one of those spontaneous children of peril, appeared: a sailor from New York took the place abandoned by the steersman. I seem to see him still, in shirt and canvas trousers, bare-footed, hair drenched and tangled, grasping the tiller in his strong hands, while he looked back over the stern for the wave which would save or sink us. Here came that wave, the width of the channel, tall and rolling along without breaking, as if one sea were invading another’s domain: great, white birds flew steadily before it like birds of death. The ship touched and held fast, there was complete silence; every face blanched. The swell arrived: at the moment it reached us, the sailor put down the helm; the vessel, about to fall on her side, lifted us over. The lead was heaved: it registered twenty-seven fathoms. A cheer rose to the heavens and we joined in the shout of: ‘Long live, the King!’ God did not hear that prayer for Louis XVI; it benefited us alone.

Clear of the two islands, we were still not out of danger; we could get no higher than the coast at Granville. At last the ebbing tide carried us out and we doubled the cape of La Hague. I experienced no fear during this near shipwreck and felt no joy on being saved. It is better to depart life while young than be evicted by time. Next day, we entered Le Havre. The whole population had turned out to greet us. Our top-masts were shattered, our longboats lost, the quarter-deck razed, and we shipped water with every pitch of the vessel. I climbed down onto the jetty. On the 2nd January 1792, I again trod my native soil which would soon slide from beneath my feet. I brought no Eskimos from the Polar Regions with me, only two savages of an unknown race: Chactas and Atala.

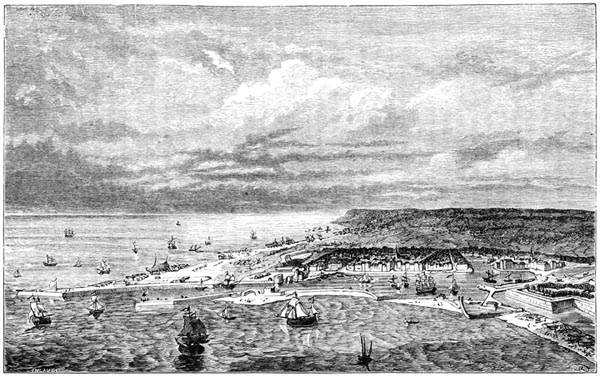

‘Le Havre en 1779’

Le Havre, son Passé, son Présent, son Avenir - Frédéric de Coninck (p105, 1869)

The British Library

End of Book VIII