A Honeycomb for Aphrodite

Reflections on Ovid’s Metamorphoses

Part IV

A. S. Kline © Copyright 2003 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- XVI Respect and Impiety

- XVII Crime and Punishment

- XVIII Ovid’s attitude to War and Violence

- XIX Tenderness, Pity, Pathos and Regret

- XX Ovid’s Civilised Values, the Sacred Other

- XXI The Later Influence of the Metamorphoses

- XXII The Wings of Daedalus

XVI Respect and Impiety

Woe to those who fail to recognise a god, or who mistake a god and worship the wrong god. These divine strangers in a human form, not caught in stone or marble, on a frieze or a tombstone, but living forces in the world, are guests to be welcomed. When the god or the goddess arrives and is known, the heart shakes and the mind is dazzled, the eyes mist and the body trembles. Life breaks in, and it is the oldest, perhaps the only sin, to fail to know or respect its power to change us, to bless us. Life, Nature is the given, the sacred, that which humankind did not create, that which we violate at our risk. Grace is the movement of the mind and heart that welcomes the gods with humility: those hidden powers: those inner forces that shape our existence. And Impiety is that lack of respect, that failure of recognition that punishes and kills the spirit.

The Metamorphoses is full of those moments of disrespect to the gods, those challenges to them from pride, that insolence that claims for itself, for its own conscious self, the powers of the psyche that are fuelled from deep within. Every art, every act of skill, every Olympian moment, every flowing phrase, every tender perfection of the loving gesture, is a gift of the psyche, of the deep spirit inside us, of the forces whose effects psychology recognises, but of whose nature it has no true idea, and for whose identity it has no meaningful names. They are not occult forces, there is only a mystery, and perhaps religion is just the response to the power of that mystery, that we barely know ourselves. Delphi gave human beings the two greatest challenges, in the inscriptions over the temple of the god, ‘Know yourself’ and ‘Nothing in excess’, the two things most difficult for the conscious mind, because the secret of both lies hidden, and within. Time after time in the Metamorphoses, in the Greek myths on which Ovid draws, the protagonists fail both tests. Through pride as we have seen, through vanity, through envy, through greed. And through lack of recognition, through an impious indifference, a wilful abuse of the sacred.

‘Cadmus and Harmonia turned into a serpent’

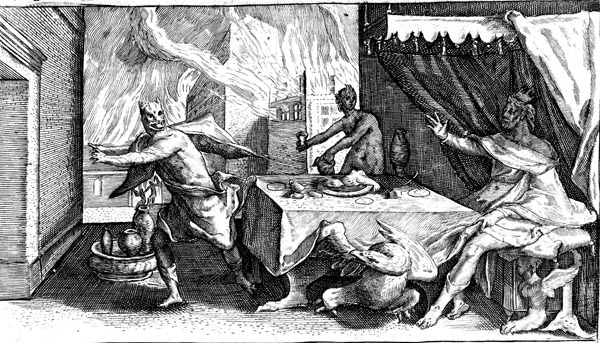

There is Pentheus, imprisoning, and threatening to torment, Bacchus, who, as Acoetes, has fallen into his hands. But just as the god’s powers transformed the sailors into sea creatures, into dolphins with tails like ‘the curved horns of a fragmentary moon’, so now ‘the doors flew open by themselves, the chains loosening without effort’ (Book III:692) and Pentheus, that ‘fighter against the gods’ (Euripides: Bacchae), angered into attacking the mysteries is torn apart on Mount Cithaeron, at the hands of the Maenads, at the hands of his own mother, Agave, his limbs scattered like leaves stripped from the branches by the autumn frost. The daughters of Minyas deny the god also, and are changed to bats, creatures of Dionysus’ twilight hour, the borderland of night and light (Book IV:389). So too the serpent of an unintentional impiety rises again to haunt and transform Cadmus and Harmonia (Book IV:563). So Erysichthon shatters the sacred tree, offending Ceres-Demeter, ancient nature goddess, and is punished by her opposite power, that of Famine (Book VIII:725). So Myrrha makes wrongful use of the festival of Ceres, sleeping with her father, Cinyras, without his knowing her identity, while the Queen is absent from his bed, observing the rites (Book X:431). So Atalanta and Hippomenes commit sacrilegious union in the cave of the Goddess (Book X:560), so Midas is punished with ass’s ears for denying the judgement of the gods (Book XI:172), the Greeks are punished for Ajax the Lesser’s rape of Cassandra in the temple of Minerva (Book XIV:445), Acmon for denying Venus (Book XIV:483), and the Apulian shepherd for mocking the nymphs (Book XIV:512).

‘Minos and Scylla’

But the gods are not mocked. Running as a thread through the Metamorphoses are Ovid’s symbols of order and moderation, law and respect, justice and piety. There is Deucalion the just man, and his wife Pyrrha, who survived the flood, ‘no one was more virtuous or fonder of justice than he was, and no woman showed greater reverence for the gods’ (Book I:313): there is Minos ‘most just of legislators’, who recoils from Scylla’s passion and her ‘impious prize’ her father’s lock of hair, Minos who ‘establishes laws for his defeated enemies’ (Book VIII:81), who thinks it ‘more useful to threaten war than to fight’ (Book VII:453), whose Cretan legal institutions, divinely inspired, were said to have been introduced into Laconia by Lycurgus (Pausanias III.2.4), and who, Homer claims, ‘spoke with great Zeus’ (Odyssey XIX:178). There is Aeacus, equally beloved of Jupiter, his people decimated by the plague sent by an unjust Juno, whose island of Aegina Jove repopulates (Book VII:614): and there is Pythagoras, the voice of Ovid’s own moderation and respect for the sanctity of life (Book XV:453).

But the crystallisation of Ovid’s thoughts he brings to life beautifully in the story of Baucis and Philemon, a charming and powerful tale that weaves together loyalty and tenderness, piety and humility, grace in poverty, and sweetness in death. The story is placed at the very heart of the Metamorphoses in Book VIII (611) at the very end of that Book, at the core of the work. It is Ovid’s most delightful and most potent expression of true moral values, an expression by now so conventional no doubt as to seem almost trite to a modern reader, but the values shine, and the words express that deep-seated response of the ancient world to the vicissitudes of fate and to its transience, a response that leaned towards moderation, hearth and home, constancy and quietude, love of peace and the ability to find beauty and contentment in little things. The Chinese poets of the turbulent T’ang Dynasty, had that same response: love of simplicity, natural beauty, reticence, modesty, respect and generosity. And it became a powerful current in European thought, a counterbalance to all the movements towards excess, all the movements of revolution, dislocating emotional intensity, religious extremism, rapacious colonisation, all the violence and anguish experienced by the European spirit and those with whom it came in contact.

Jupiter and his son Mercury travel to Phrygia disguised as mortals. There they find that strangers are not welcome, until they reach the humble cottage of Baucis and Philemon, a long-married couple who live ‘making light of poverty by acknowledging it, and bearing it without discontent of mind.’ Ovid describes the hospitality they offer, using all his literary skill to create the equivalent of a Rembrandt scene, darkness all around, but this spot existing in a shaft of light, where the natural and the human blend. Ovid the ultra-civilised Roman was a city man, and a critical attitude might claim that either Ovid was using irony here, or that he was indulging in, even establishing, a literary convention of rural scene painting that we are familiar with from Renaissance theatre and poetry, and the novelistic tradition. But there is no shadow of irony, only perhaps a very gentle empathetic smile at the corners of Ovid’s lips. And while delight in and even nostalgia for the rural is a feature of many literatures, there is a genuine feeling here for the continuity of the natural and the human.

At the centre of the table laid out for the guests, covered with the products of their simple lives, is ‘a gleaming honeycomb’. And, Ovid says, ‘Above all, there was the additional presence of well-meaning faces, and no unwillingness, or poverty of spirit.’ As the wine bowl refills itself, unaided, the old couple recognise the presence of the gods, and acknowledge them. So they are spared the destruction of their neighbours for the sin of impiety, and clambering up the mountainside they see their own house transformed into a temple of the gods. Jupiter now grants them a wish, and the essence of the story is contained in their response. They wish the piety of their lives to continue by becoming priests of the temple, and the harmony of life to be continued in death, by relinquishing their lives at the same moment. The god grants their wish, and they are metamorphosed in death into two trees, an oak and a lime tree, symbols of the two gods.

‘Jupiter and Mercury visit Philemon and Baucis’

Ovid carefully ends Book VIII with the contrasting tale of Erysicthon’s impiety, so that the two stories intertwine at the heart of his work. But the interest is less in any genuinely religious aspect of the tales, which I think was slight in Ovid’s mind, the Greek gods are already for him a kind of stage machinery, as in his endorsement of natural and moderate human values. The issue is not so much what fate brings us, as in our reaction, and Ovid is forever interested in detail, of how things work, of how we behave, and in the quality of response we make to events, the degree to which it reveals empathy, loyalty and love. Experience makes the story of Baucis and Philemon appear more valuable. As the firestorm of the Iliad fades into the past, Odysseus indeed longs for his own house and his Penelope, saying to Calypso ‘Powerful Goddess, don’t be angry with me. I know myself that Penelope, the wise, is less glorious than you in form and stature, since she is mortal while you are ageless and immortal. But even so I always wish that I might reach home, and see the day of my return.’ (Odyssey V:215). And it is Euripides writing late in the darkness of the Peloponnesian War who celebrates, in the Bacchae, most powerful of plays, ‘the life that gains the poor man’s common voice’ and declares that ‘a true and humble heart that fears the gods is man’s greatest possession’

‘Erysichthon fells Ceres’s sacred oak tree’

XVII Crime and Punishment

Many of the tales deal then with personal excess, the result of pride or passion or impiety, but treated in a manner that draws out the pathos of the innocent victim, or the appropriateness of the resolution for the protagonist. So, Nyctimene’s incest ends in her transformation into an owl, while she is ‘conscious of guilt at her crime, and flees from human sight and the light, and hides her shame in darkness, and is driven from the whole sky by all the birds.’ (Book II:566). Or there is Pyreneus, who threatens the Muses, and falls headlong to the earth below as he tries to follow their winged flight (Book V:250). Or the impious Lycians turned into frogs by Latona (Book VI:313). While Procris a victim of Cephalus’ error, dies loving her murderer, her own husband (Book VII:661), and Hesperie falls an innocent victim to Aesacus passion and a snake in the grass (Book XI:749). Ovid’s humanity is engaged by those destroyed by excess, and often his sympathy extends to the sinner as well as the sinned against.

‘Jupiter turns king Lycaon into a wolf’

Nevertheless there are crimes which extend beyond the borders of the venial, those which cause us to feel a deep repugnance, and which bring down on themselves a fiercer punishment. Murder and violence against kith and kin incur heavy retribution. Lycaon impiously tests the gods with human sacrifice, and as a result loses his humanity, and becomes a wolf but with ‘the same violent face, the same glittering eyes, the same savage image’ as he had before, his crime symptomatic of the immorality and impiety before the flood (Book I:199). Pentheus, who has men tortured and ripped apart, is himself torn apart by the followers of the god (Book III:511). Tereus suffers a terrible retribution for his mutilation and rape of his sister-in-law, Philomela, in tasting the flesh of his son (Book VI:401), while Meleager pays for the murder of his uncles ‘alight with that fire, his inner organs invisibly seared.’ (Book VIII:515). The Cerastae of Cyprus pay for their ritual sacrifice of strangers (Book X:220), and even a hero like Peleus must be exiled and troubled for the murder of his brother (Book XI:266), and Diomede for wounding the goddess Venus in the heat of battle (Book XIV:445). And there is retribution for Caesar’s assassins, whose names do not appear, but whom Augustus (Octavian) defeated, acting as his adoptive father’s avenger. Dante will reserve a special place in the lowest, most treacherous circle of the Inferno for them: Brutus and Cassius occupying two of Satan’s three mouths, with only Judas as their companion (Dante, Divine Comedy: Inferno XXXIV)

‘Althaea kills Meleager’

Nevertheless it is interesting how few of the bloodiest myths of the Greeks enter the Metamorphoses, and how peripherally those that do are handled. Ovid, seeking to show his own preferred world, steers away from the darker events of war and tragedy. The War at Troy is only indirectly touched on in the unjust sacrifices of Iphigenia and Polyxena, as is the War of the Seven against Thebes . Tantalus, Pelops, Atreus, Thyestes, the whole cycle ending in the deaths of Agamemnon, Clytemnestra and Aegisthus, and the Oresteian sequel, is barely mentioned. Phaedra is not a significant character here, except as she acts against Hippolytus himself. Oedipus is not present. There is no Creusa or Alceste. For Ovid, as for Euripides, who surely influenced him, the myths show the appalling treatment men mete out to women, the pointlessness and sadness of revenge, and the stupidity and destructiveness of violence, and in his own way, though not through Euripides’ tragic art, he seeks ‘the joys that outshine all others, and lead our life to beauty and goodness, the joy of the holy heart.’ (Euripides: Bacchae)

XVIII Ovid’s attitude to War and Violence

Greek epic and tragedy spends much of its time concerned with war and its aftermath, with conflict and the bloodiness of revenge, with political power and its casualties. The Metamorphoses has only an oblique relationship to that world, since it deals with mass violence, particularly that between men, in a fairly compartmentalised way, and human vengeance is a minor theme in the work. Ovid’s own attitude is perhaps best detected in his treatment of characters nobler perhaps than the heroes. The heroes themselves seem somewhat obtuse: they are blind forces rattling around within their myth cycles. Ovid makes no attempt to give depth to Theseus, Perseus, or Achilles, though he manages a little better with Hercules and Ulysses. The reality I think was that the heroes had little true appeal for him, other than in their picturesque qualities. Ulysses interests him the most, as an exemplar of mental ability. True to his own goddess, Venus-Aphrodite, Ovid prefers to deal with affection, beauty, and peace.

On the positive side we come across Minos, ruler of a hundred cities to whom war and vengeance is a necessary component of power and right, but who established laws for his defeated enemies (Book VIII:81), and who ‘thought it more useful to threaten war than to fight, and consume his strength too soon.’ (Book VII:453). There is Ceyx, whose brother Daedalion was warlike, but he himself cared for peace and the preservation of peace (Book XI:266), and there is Pythagoras, hating tyranny, into whose mouth Ovid puts eloquent words as to the sanctity of animal life (Book XV:453). And there is the cumulative effect of his tenderness and the pathos of his depiction of violent personal events (Pentheus, Actaeon, Philomela, and so on) that leaves the feeling behind of an unwarlike non-violent man: a feeling reinforced by his other works. Yet there is no unequivocal repudiation of violence. Rome in fact is the result of a warring culture. It was Euripides who lived through the Peloponnesian War four hundred years earlier, which tarnished forever the concept of war, and erased the heroic charms, such as they are, of the Iliad and Mycenean Greece, who presented the true ugliness and criminality of violence (Euripides: The Women of Troy, The Phoenician Women, Iphigenia in Aulis). Euripides acclaims Dionysus whose ‘dear love is Peace, the wealth-bringer, the saviour of young mens’ lives, rare goddess.’ (Euripides: Bacchae) Ovid, less powerfully, reduces male military violence to a puppet play. But perhaps it is no coincidence that it is Bacchus-Dionysus, the presiding deity of Euripides’ play, who appears early on to punish the crew of Acoetes’ ship, with almost casual power, for their violence and impiety, and to cause Pentheus’ destruction (Book III:638)

‘Phineus falls to Perseus’

Book V has the battle between Perseus and Phineus, a ‘rash stirrer-up of strife’ who as a character does not come to life, lacking meaningful attributes (Book V:1). Cepheus condemns the conflict which is opposed ‘to justice and good faith’, but what follows is a display of pointless violence, designed to allow Ovid opportunities to show pathos, but by modern standards lacking in any redeeming irony, or true distaste. Perseus terminates the affair with his use of the Gorgon’s head, and the stony end to the piece is a fair reflection of its obtuse and solid nature. Book VIII gives us the shorter and more poetic Calydonian Boar Hunt, whose violence is relieved by the presence of Atalanta, and the build-up to the fate of Meleager. Like the previous battle it no doubt appealed to the Roman delight in the physical, in fighting and hunting, and Ovid was both playing to his audience and displaying his ability to create interesting incident. His third set-piece, inserted to balance the whole work, is the Lapiths and Centaur’ battle in Book XII, preceded by Achilles, the killer on the loose, (Book XII:64) in order that the tale of Cycnus can be told. This fracas is relieved only by the pathos of the tale of Cyllarus and Hylonome (Book XII:393), otherwise it is to me an unredeemed excursion into mindless execution.

‘Meleager and Atalanta – the Calydonian Hunt’

It seems a shame that Ovid could not bring himself to clearly condemn what he patently did not enjoy or approve. But then I say that as one who finds large parts of the Iliad despite their brilliance, and a great deal of Greek and later tragedy, unpalatable and emotionally exploitative. That is a modern personal and moral judgement rather than an artistic one, and I am not denying the ‘greatness’ of much of that writing from an aesthetic viewpoint, nor even that it was precisely the writers’ intention to display the sordid ugliness of violence, of war and vengeance. It would be harsh indeed to blame Ovid, with his intense curiosity for all forms of activity, his delight in pictorial detail, and his cultural context, for displaying to a Roman public the military ethos in which they had their existence. However I would argue that the violent set pieces are inferior to the rest of the Metamorphoses, both in depth of pathos and in quality of writing, and that on aesthetic and moral grounds he failed to reach the heights. He is only too aware elsewhere of his lack of ability to write epic or tragedy, and perhaps his only real mistake here is an artistic one. If he had reduced the duration of the two outer set pieces, in the way he did with the Boar Hunt, and perhaps introduced some further elements of feminine pathos, as he does with Atalanta, and later Iphigenia and Polyxena, it would have been more successful. However it is churlish to be over-critical. All three set pieces are only minor elements of the whole work. I suppose I am merely lamenting a missed opportunity.

XIX Tenderness, Pity, Pathos and Regret

It would be sensible, after that, to remind ourselves of the grand sweep of the Metamorphoses, and contrast the relative failures of Ovid’s fighting and hunting scenes, with three of his finest moments in the work, ones which display his deepest instincts. In the tales of Cephalus and Procris (BookVII:661), Baucis and Philemon (Book VIII:611), and Ceyx and Alcyone (Book XI:410), Ovid shows his deep empathy and his delight in long-lasting affection between men and women who are equal partners, as well as the pathos of character and circumstance, and the nature of human frailty, transience, and limitation. Cephalus, ‘silent, and touched with sadness for his lost wife, tears welling in his eyes’, is filled with deep remorse for his accidental killing of a woman who loves him deeply, he, guilty of mistrust and jealousy, inadvertently causing mistrust in return. Procris flees his attempt to corrupt her, ‘hating the whole race of men,’ but returns to him and forgives, gifting him sadly with the means of her own destruction (and it is perhaps no accident that a gift of virgin Diana in a sense ‘punishes’ a woman who chooses to forgive male error). His mistrust in her has generated a tendency to reciprocal mistrust in her, so that she comes to believe him unfaithful. Ovid skilfully shows a joint undermining of faith, and by introducing an informant, also, reinforces the nature of betrayal, outside and within relationship. Everything ends in that error and accident, carelessness and loss, which compose so much of the sadness of life. The whole story is beautifully handled.

Baucis and Philemon, in contrast, is a story of exemplary human values. The old couple, generous of spirit despite their poverty, or perhaps because of it, welcome the gods, as strangers, in that oldest reflex of true civilisation. To keep a place for the stranger is to keep a space for the god. And that gift of grace towards the unknown is repaid by a gift in kind. The grace to give freely of what little they have is matched in this pious pair by a grace to choose wisely when the gods offer a gift in return. They choose to face the unknown together, in a gesture of loving human solidarity, the deep tie of affection binding in death as in life. Unlike the story of Procris and Cephalus the pain of love’s loss is almost averted, and the whole tale stands as a symbol of natural harmony, a moral grandeur close to the earth that ends in transformation into the speechless mutual harmony of the trees. It is a deep message from the oldest Greek culture, the antithesis of hubris, an exhortation to ‘make the heart small’ as the Chinese say, to embrace modesty, humility, quietude and resonance with nature. Ovid who often shows the Roman citizen’s gentle mockery of rustic behaviour, and praises civilisation, here shows that he understands the roots of true civilisation, not artifice and political power, but moral clarity, the splendour of living a life that is true, sensitive and kind.

‘Alcyone prays for the safe return of Ceyx’

The third story, of Ceyx and Alcyone, is an illustration of the vagaries of existence, the cruelty of our state, regardless of the exemplary values of the protagonists. Here is true love and affection indeed. Ceyx, who cares for peace, and for his wife, must sail away, and in doing so goes to his death separated from her. Here is ‘change, blind chance, condemning countless human lives to misery’ (Euripides: Ion). Ceyx is a son of Lucifer, and therefore of the consort of Venus, the morning star. His departure evokes the ‘loss’ of parting, and extracts from him the fatal promise to return, unfortunately without the qualifying adjective ‘alive’. The picture of Alcyone’s grief at the separation is powerful, and the description of the storm a convention-setting tour de force. The drowning of the husband here echoes the drowning of Leander in the Heroides (Heroides: XVIII and XIX). A semblance of the dead Ceyx, sent by the pitying Juno, appears to Alcyone in a dream, and her realisation of his death on waking is heart-rending. Alcyone is ‘nothing, is nothing, she has died together with her Ceyx’ (Book XI:650). She finds his body in the waves, washed to the shore. And both are transmuted to seabirds, the mythical halcyons. ‘Though they suffered the same fate, their love remained as well: and their bonds were not weakened’, possessors of ‘those affections maintained till the end.’

Among the many beautiful variations on the theme and nature of love, that Ovid gives us in the Metamorphoses, these three stories impress greatly. Here is love harmed by mistrust and error in the story of Cephalus and Procris, and ending in loss: by external mischance in the case of Ceyx and Alcyone but rescued by transformation: and triumphant in its final simplicity in the tale of Baucis and Philemon. The poet reminds us of our and love’s vulnerability to transience, to error, to disloyalty to harm. And he asserts the values of honesty, constancy, sympathy and kindness, the beauty of relationship, and the tragedy of loss. It is significant that all three stories are of married lovers. Ovid sees marriage, the relationship rather than the institution, as an opportunity for partnership that lasts, in which love, truth and beauty can abide.

XX Ovid’s Civilised Values, the Sacred Other

It might be helpful to draw together the values that Ovid subtly proclaims in the work, subtly because his primary aim is to entertain, which he does with poetic beauty, and an almost visual charm. But his values shine out, in continuity with those of the Greek culture from which he draws his content. He exemplifies the reality that all great art has a moral core, and that ‘art for art’s sake’ is a slogan with which to fight a philistine society rather than a true tenet of artistic belief. The sublime is an echo of a great spirit. And a great spirit is an intrinsically moral spirit, not in the sense of a moral code, or an imposed set of social rules, but in the sense of the instinctive knowledge of the potential of life, that engenders a deep sense, and instinct for, rightness. Truth, beauty and love, are there related to tact, grace and kindness. Plato’s somewhat hostile pillars of Idea, are transmuted into the quiet practical injunction to be true, to be sensitive, to be kind. It is remarkable that Ovid could lay aside the cloak of wit, cleverness and ironic social comment that he wears so successfully in the Amores, the Art of Love, and the Cures for Love, and show himself a sweet singer of the deepest affections as he does here.

I would argue that the Metamorphoses are primarily about Woman. Ovid has taken to heart, and it is instinctive in him, the importance of women within the mythical world of the Greeks, exemplified in the roles of the goddesses, and of women in epic and tragedy, culminating in Euripides’ deep insights into their fundamental roles as victims and civilisers, the realisation that ‘Life is harder for women than for men’. ‘Oh, the wrongs of women, the wickedness of gods!’ cries Creusa (Euripides: Ion).

So Venus-Aphrodite is the presiding goddess of Ovid’s tales. Love as passion, love as affection and tenderness, love as loyalty and partnership, and the erotic as desire, the erotic as lust and excess, the erotic as entanglement and seduction, are driving forces of many of the tales. But Venus is only one aspect of the Great Goddess who appears in her many forms, bringing with her female values, softening the arbitrary, ruthless and ambivalent nature of the divine as it cuts across human existence.

The gods are those same strangely amoral forces that Homeric literature created, representing the power of nature and fate, the way in which the world can seem to align itself with mortals, and then discard them. The gods bring passion and the embrace of something akin to love, but they also bring desertion and betrayal, an injustice that goes hand in hand with justice. They support but they also persecute, they grant gifts but they also destroy. Man humanises his postulated divine, his imagined gods, and yet, to conform to the neutrality and non-alignment of nature, they must also be pitiless and indifferent, as well as nurturing and protective. The best strategy for human beings is to follow the middle way, avoiding competition with the divine, eschewing lust, pride, vanity, greed, gratuitous violence, walking cautiously, taking care to identify and respect the presence of the gods. But avoidance is not always possible. Certain events are destined. Certain characters become protagonists in actions and tragedies beyond their own control. Certain characters have weaknesses that in the intensity of the divine light become fatal flaws that precipitate disasters. Excess results in self-created or divine vengeance. Crime that offends the gods is punished. Jupiter-Zeus presides over a rough justice, a royal justice that depends upon his desires and whims as well as on the work of the Fates.

‘Byblis and Caunus’

Within such a world of power, arbitrary force, possession and destruction, Woman struggles to hold her place. If she is fortunate she is Nausicaa, the sacred virgin (Odyssey: VI), Circe the beautiful self-sufficient sorceress (Odyssey X), or Penelope the beloved wife (Odyssey XIX). If not she is likely to experience separation, frustrated desire, failed relationship. She is Callisto, the raped victim (Book II:417), or Procris the wife annihilated by mischance and misunderstanding (Book VII:796), or Medea, betrayed and perverted (Book VII:350). Driven by a thwarted erotic passion she is Phaedra (Book XV:479) or Byblis (Book IX:439), crossed by a malign fate she is Cassandra (Book XIII:399) or Clytemnestra (Book XIII:123), or one of countless other women who become victims, criminals, or adulteresses, under the stress of events. ‘Since you possess power,’ Euripides admonishes Apollo, through the voice of Ion, ‘pursue goodness….how can it be right for you gods to make laws for men, and appear as lawbreakers yourselves?’ (Euripides: Ion) So Byblis sees precedents among the gods for her incestuous desire. So Clytemnestra, robbed of her daughter Iphigenia, by a crime against women, seeks terrible revenge against the husband who committed it. Crime begets crime. And there is the power of a god behind much that happens. The protagonists are caught in the flame of a divine interference, the light of a numinous and merciless demand upon the inadequate and innocent mortal, to whom fate in the form of the divine, says, as it does to Pentheus ‘You do not know what you are saying, or what you do, or who you are.’ (Euripides: Bacchae) The god has appeared, undefined, un-analysable, creator of joy or frenzy, passion or form, beauty or terror.

What is woman to do, how is the Goddess to act, in such a world? The divine woman, the ancient triple-goddess, wraps around herself a sacred space, a silence and a darkness, and becomes Diana-Artemis or Ceres, that Demeter of the mysteries. To violate her domain is to die like Actaeon (Book III:232), or Erysichthon (Book VIII:843). Diana defends the rights of women to live without men, inviolable and independent, and Dionysus too allows woman an expression of that deeper identification with unformed creation, with nature and the night outside human law and the civilisation that men create. His Maenads punish and sacrifice.

Or the divine woman, the Goddess, involving herself with the male, wraps herself in the beauty of the seductive and enchants men, takes them back into her womb as the maternal power, begetting where they were begot. She is Venus-Aphrodite then, the sweet and beautiful and tender, and she is that Juno-Hera who is also Cybele, the ancient Mother, who is childbirth and castration, the bed and the maddened dance of the flesh, married fulfilment and enforced celibacy. She is the conqueror of the mortal male, though no longer of the god. On a lesser and less successful plane she is a witch and sorceress, a Medea, a Circe. As Juno she is jealous of her place and punishes infidelity and betrayal, persecuting Jupiter’s girls, Io (Book I:601), Latona (Book VI:313), Aegina (Book VII:453), robbing Echo of her voice (Book III:359), weighing down Hercules with toil (Book IX:159), opposing the people of Paris, the failed judge: those Trojans (Book XIV:75). Yet as Venus she cherishes her son Aeneas (Book XIII:640), mourns her lover Adonis (Book X:708), pities the mother Ino (Book IV:512), ensures that those she loves and cares for are made divine, and as Isis, too, she supports the rights of the lover and the child, the mother and the bride (Book IX:666).

Or the Goddess aligns herself in a related but separate dimension to man and his violence, she arms herself for protection, and enters the world as mind, not body, enters it at right angles to human events, intervening but swiftly vanishing, a winged thought, in the shape of a bird. She is Minerva-Athene, to whom women can look for the skills of their domestic world. She brings the power of self-control, and awareness: she shows the paths of intellect and cunning. Apollo supports her, seeking perfection and form, metre and harmony, the bounding line and the clear light. From Apollo the tenderness of the creative flows. They care for their own, for the spirit and for the mind, and both cherish the Muses.

Through her own powers and her gift for self-protection the Goddess commands her sphere within reality, even in a world of dominant male forces. She occupies sacred distance, and the world of women. Even so she is still vulnerable when, interacting with the male world, she trespasses outside her role. Venus can still be wounded by Diomede (Book XV:745), and lose her Adonis (Book X:708).

For the mortal woman, without power, there is only an uncertain defence. Her gentleness, sensitivity, tenderness, kindness, moderation, loyalty, and natural empathy are scant protection against ruthless forces. She learns to distrust power, violence, cunning as means to human ends, though that same mistrust is corrupting, destructive of love, and of trusting surrender. Diana’s realm, Nature, and the isolation of the sacred band, is a partial refuge for her. It asserts woman’s free will and erotic self-sufficiency. But even there, as Callisto (Book II:417), or Syrinx (Book I:689), or Arethusa (Book V:572), she is vulnerable. Like the divine Thetis (Book XI:221) she can be overpowered, despite her many wiles. Only en masse, as the Maenads, do women have the power to attack the male and the male-lover, to destroy Pentheus (Book III:692) and Orpheus (Book XI:1).

Otherwise woman must enter the world of male power. She must undertake the risk of relationship. There, if she does not fail in her womanhood like the hard-hearted Anaxarete (Book XIV:698), or prostitute and objectify herself like the Propoetides (Book X:220), she is likely to become the helpless victim, Semele (Book III:273) or Echo (Book III:474), Iphigenia (Book XII:1) or Hesperie (Book XI:749). In response she may be perverted or corrupted by suffering, and retaliate, as Philomela and Procne do (Book VI:619), or Althaea (Book VIII:451), or Hecuba (Book XIII:481). Or she may die not merely bravely like the daughters of Orion (Book XIII:675), but asserting her rights as Polyxena does (Book XIII:429), or like Caenis, seek to escape woman’s fate and become male (Book XII:146). In the background Cyane cries woman’s violation (Book V:385), Latona our right to a world of compassion, where what Nature gives is shared and free to all (Book VI:313).

‘Perseus rescues Andromeda’

If she is exceptionally fortunate she will find love and affection, rescued like Andromeda (Book IV:753), finding long-lasting marriage like Harmonia (Book IV:563), or fused like Salmacis with her lover (Book IV:346). But true love also brings with it the likelihood of the loss of her lover, with his death, like Alcyone (Book XI:710) or Procris (Book VII:796), Hylonome (Book XII:393) or Thisbe (Book IV:128), echoing Venus’ loss of Adonis (Book X:708). Or it offers the cruel possibility of rejection or desertion, as Scylla (Book VIII:81), and Circe (Book IV:1), Ariadne (Book VIII:152) and Medea find (Book VII:350), or she will be betrayed like Leucothoe (Book IV:214), or Herse (Book II:708), or persecuted by another lover like Galatea (Book XIII:738) or by a rival like Canens (Book XIV:397). Even asking for the wrong gift is fatal, as the Sibyl knew (Book XIV:101), and Semele (Book III:273). And as a mother, too, the loss of her children may torment her even more deeply, regardless of the cause, as we find Hecuba (Book XIII:481) or Niobe (Book VI:267), or Ino (Book IV:512) echoing Ceres-Demeter’s archetypal loss of her child (Book V:425), and Aurora’s loss of Memnon (Book XIII:576).

And woe to the woman if she strays beyond the bounds set by a male world, and loses self-control. If she is incestuous like Myrrha (Book X:298) or Byblis (Book IX:439): or driven by dangerous passion like Phaedra: or boasts for a moment of her skill, or wealth, her status or family, or rejects the god as the daughters of Minyas do (Book IV:31), and Niobe (Book VI:146), and Arachne (Book VI:26): or commits an impiety like Atalanta (Book X:681), or Dryope (Book IX:324): she will be punished for it. Theseus (Book VIII:152), Ulysses (Book XIII:1), Hercules (Book IX:159), Perseus (Book IV:604), Peleus (Book XI:266), Jason (Book VII:100), Aeneas (Book XIV:75), those heroes commit some dark deeds, but their punishment is often delayed or averted, or falls on someone else. So for a woman to be close to a hero is as dangerous as to be near a god. For her it mostly results in grief. Creusa complains that: ‘they judge us, good and bad as one, and revile us. That is the fate we are born to.’ ‘When our oppressor has all the power, where can we go for justice?’ (Euripides: Ion)

In the face of all this suffering the Goddess can only shed her tears on the world, and show her pity. There is the pathos of innocence destroyed: the sadness of transience and mortality: the slight consolation for us, which is no consolation perhaps to the victim, of refuge in metamorphosis. There is love despite its frailties, and its losses. Venus still stirs the world she cannot rule. There is speech, for women to articulate their situation: there is courage, and endurance. And sometimes all things come together and there is happiness. Isis helps Iphis (Book IX:764), Venus transforms the statue for Pygmalion (Book X:243), Penelope reclaims her Ulysses (Odyssey XXIV), Ceyx and Alcyone (Book XI:710), Cadmus and Harmonia (Book IV:563), Baucis and Philemon (Book VIII:679), Orpheus and Eurydice (Book XI:1) are united in death or transformation, as in life. Hersilia is deified to join her Romulus (Book XIV:829).

‘Hersilia is deified’

Ovid and Rome are the heirs of that final Greek scepticism regarding the gods. How to reconcile evil and suffering with divine justice, when even the gods themselves display human failings? The world where gods and men speak together, where the Olympians attended Cadmus’ wedding, and a walk in the woods, or the opening of a door, might bring a divine visitor, is long gone. Ovid plays with a domain of legend and miracle, and the real subject, the true content, of the Metamorphoses is the nature of a world of chance and risk, fate and misfortune, of how human beings behave, and how they respond to events. At the centre are women, silent or articulate, noble or humble, virtuous or tainted, essentially powerless, but ever enduring. The Goddess survives.

Ovid in his selection of the myths and in his re-telling takes care to emphasise the moral values centred round pity and empathy, kindness and love, loyalty and moderation. He builds an image of a beautiful, harmonious and sacred Nature that surrounds the human. True there are pitiless forces at work, represented by the gods or fortune, and Nature can be used and abused. But the overwhelming feeling is of a love, beauty and truth that is attainable in the world and in human relations, even if only transiently. Woman and Nature therefore share a sacred otherness, a distance from gratuitous deliberate violence and the objectification of human beings. Through his use of Pythagoras as a mouthpiece, he even asserts a strong doctrine regarding the sanctity of animal life. Within his most beautiful stories, Ceyx and Alcyone, Philemon and Baucis, Cephalus and Procris, he gives extended treatment to enduring love, the dangers of mistrust, the beauty of loyalty and affection, the deep bond between man and woman in partnership, as well as displaying elsewhere the bonds between lovers, between man and man, woman and woman, mother and child. Venus and Adonis, Ceres and Proserpine, Cadmus and Harmonia, Orpheus and Eurydice, love is everywhere. And order and justice, moderation and consideration, grace, kindness, generosity, are all on display, the civilised values. They survive the intrusions of the wild, that serve to remind us of the inner spirit, of our continuity with Nature, and our proper place in the universe, they survive the tempest and the flood, Dionysus’ Maenads and Diana’s vengeance.

In the end the human values, the secular values survive the gods. Life remains sacred, and the other, the human other, to whom we reach out in every word and act, remains within a sacred space. The torch the Greeks lit that led to the Homeric period of literature, and which the intellectual life of Athens nurtured, in the golden fifty years of fifth-century BC Hellas, was passed on to Italy, and to Ovid above all in the literature of the later but corresponding half-century of Augustan Rome. Greek content informed Roman civilisation, but the Romans also chose the values that they passed on. They learnt from the Greek lesson, and drank at the Greek fountain. And Ovid’s Metamorphoses remains the loveliest of all the re-telling of the myths, and helped the Greek stream to flow on into European history. I would claim more for the work than that. Ovid reaches back to Cretan values and to the values of the Goddess. He, like Euripides, makes women central to experience, and he civilises and polishes the rawness of the myths, he softens cruelty and crudity to the extent that he can, making pathos of suffering, tragedy and loss, revealing love and joy, generating visual charm and poetic delight to weave these tales of dark and light. And he weaves them for all time as he knew, and as he proclaims in his closing words. He was gifted with the richness of the flowers of the Greek fields, and he made from them honey for the Goddess.

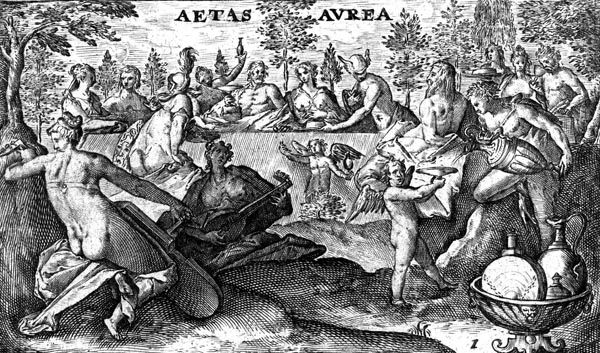

‘The Golden Age’

XXI The Later Influence of the Metamorphoses

Though Ovid’s work survived, his influence was muted during the later Empire and the early Christian era in the West. The pagan world as expressed by a true humanist, and a religious sceptic, was disapproved of, and its sexual freedom ran counter to Church teaching. The more orthodox, and more clearly Imperialist, Virgil was regarded more highly. But by medieval times, with a burgeoning love of the romantic, and increasingly the secular, tale, the power and charm of his storytelling was once more winning its way. Clearly, despite official distaste, Ovid never went un-read. Lactantius, the early Christian father quotes him, and Theodolphus, Bishop of Orleans, at the time of Charlemagne, mentions him approvingly, but it is the unorthodox and radical, the troubadours and the wandering scholars of medieval Europe who adopted him, and adapted him, wholeheartedly. The twelfth and thirteenth centuries enjoyed the tales, with translations and re-workings of the Metamorphoses in German, Spanish and French. His quality and material was compelling for the major poets, and Dante used Ovid as a source for mythological detail in the Divine Comedy, and Boccaccio, later in the fourteenth century, retells several tales in his Amorosa Visione, while towards the end of the century Chaucer makes extensive use of Ovid’s material, in the House of Fame, and constructs his Canterbury Tales in a storytelling vein influenced by both Ovid and Boccacio’s Decameron, while Gower retells several of the myths in his Confessio Amantis.

As the tradition of secular literature became re-established, the Greek myths took their place alongside ‘Celtic’ legends, and the Arthurian tales, as a potent source of stories for literary development, and the true vein of Ovidian appreciation, rather than translation and imitation, runs through the original work of the Roman de la Rose, and Chaucer’s Troilus and Cressida, where it is the atmosphere of secular freedom combined with depth of humanist moral tone that is critical rather than the story form. As Europe re-discovered literary man and woman outside the Biblical framework and as human emotional response, pathos and the vagaries of fortune became as interesting to literature and the common reader as Church teaching, or rather as they interpenetrated one another, so Ovid was re-established as a primary poet. The ‘subversive’ currents of his verse, in Latin, the international language of Europe, both opened a major path back to the Greek achievement, while entertaining the mind, and educating the secular trend within parts of society.

With the discovery of the Roman and Greek past initiated by the Florentine Renaissance, Ovid’s influence flows into the plastic arts of Italy, particularly Florence and Venice, where many characters and events from the myths are depicted in painting or sculpture, as well as into the literature of Elizabethan England, in Latin but also in Golding’s translation of 1567. Ovid’s influence on Shakespeare, Marlowe and others is incalculable. Shakespeare derives a great deal of scene painting from Ovid, but it is the attitude to women, that echoes throughout the plays. Shakespeare, struggling with the death of the Goddess in his own increasingly Protestant age, observes and comments on woman’s plight within the marriage market, and throughout the vicissitudes of romantic and married love. His heroines are some of his great creations, and it is hard to conceive of the wealth of Shakespeare’s female characters if the Heroides and the Metamorphoses had not existed, regardless of the fact that Shakespeare may have obtained variants of the myths and stories from many other sources, themselves indebted to Latin literature. By this time Ovid was a European legacy. Procris and Alcyone, rather than Penelope, convey the essence of Shakespeare’s loving, misunderstood or unlucky wives. Proserpine and the persecuted girls pursued by gods haunt the comedies and the last plays. While the voice of Woman lifted in protest, Polyxena or Cyane, Juno or Ceres, flows into his courageous heroines. Though the tragedies may refer back to Greek tragedy and non-Ovidian sources, there is often a pictorial quality within them that is certainly Ovidian. Meres, the contemporary Elizabethan critic, it was who said that ‘the sweet witty soul of Ovid lives in mellifluous, honey-tongued Shakespeare’. Ovid’s own wit is apparent in most of his works, but it is the Metamorphoses that convey his sweetness, in both his literary skilfulness and his tenderness of mind. That theme of the consecrated and loving marriage, so strong in Shakespeare and in Ovid, passes into the English novel, as the pastoral atmosphere of the Metamorphoses passed into English verse. The secular, humanist message is a strong component of the European Romantic tradition, with perhaps its greatest Classical adherents in Goethe, who looks to Italy, and back to Rome with its Ovidian softening of the Greek heritage, rather than to Greece: and Pushkin who in Eugene Onegin veers dramatically between the cruel loves of the gods, and a Russian homeliness like that of Baucis and Philemon, and who is a master of the light descriptive pastoral touch that Ovid exemplifies.

The Odyssey and the Metamorphoses, the wandering journey with and without a single hero, was a major influence on the development of literary structures looser than the traditional epic, and less intense than tragedy. The Arthurian legends, Boccaccio, Chaucer, Rabelais, and Cervantes, pave the way for the multi-form novel. And because the English novel became so influential, particularly on the Russian, and took for a central theme romantic love, the marriage market, and the vulnerability of young girls and wives, as Shakespeare had done, the Ovidian current flowed into it, and helped to form the moral attitudes of the nineteenth century. Jane Austen, Charlotte Bronte, Elizabeth Gaskell, George Eliot, Dickens, and Trollope, place the secular, humanist moral individual at the heart of their work. That influence extends to Tolstoy, Chekhov and the Russian mainstream, and to large parts of the French tradition. I would claim Dumas’ narratives of love, event and adventure, told in a witty and tender style, as a good and fine example of the literature of entertainment whose literary pedigree is Ovid, among others.

I do not say that Europe would not have found its way to the Greeks without Ovid, or that his literary forms are so specific that they uniquely influenced all subsequent literature, as might be claimed for Homer, or Aeschylus, but Ovid, by the very charm and ease and gentleness of his art, made imitation seem possible, and allowed Greek values transformed by Roman sensibility, and the polish of a great urban and Imperial culture, to slip almost unnoticed into Europe, ready to be reclaimed when the time was ripe. The Metamorphoses was there, a Pandora’s box ready to be opened, and with a pointer to its original sources, and to a wealth of culture, that would exhibit the Greeks through Latin, the common tongue of educated Europe.

XXII The Wings of Daedalus

Daedalus is the servant of Apollo, god of form and metre, of the organised notes of the lyre, of the running feet of the poetic art. Daedalus is an Athenian, and he creates and betrays that Athenian devotion to skill, structure, analysis, the search for the delineating outline in stone, and the definitive meaning in words. Apollo is the column and the luminous presence of the statue, the pure marble torso and the beautiful face. His echoes are the echoes of form, the empty cells of the honeycomb, the empty portico of the temple, the labyrinthine winding path to a centre, where anything or nothing may be hidden, either the oracle or the hollow reverberation of the cave. Daedalus made wings like a bird, symbol of the spirit, from their feathers and from the wax of the bees, those craftsmen, those artists, those industrious insect appliers of technique. He soared on, but his son, Icarus, who is all succeeding artists, all creators, went beyond his skill and strength and fell eventually from the sky. First learn the trade, the method, and then many things are possible within the content. Daedalus flew on, on the wings of the spirit, held together by the craft of the bees.

Where he landed at Cumae he dedicated his wings, the wings of art, to the god, and made a temple for Apollo. It was another labyrinth, above and below ground: where the Sibyl could be enraptured by divine inspiration. Virgil describes it at the start of Book VI of the Aeneid, the place where Daedalus first landed, he says, and describes the great cavern, where ‘the vast flank of the Euboean cliff is pitted with caves, from which a hundred wide tunnels, a hundred mouths lead, from which as many voices rush’. And Virgil then describes how Daedalus has depicted the Cretan maze within the decorations on its doors.

The labyrinth and the temple are epic and tragedy, the dark inner journey, the strange utterance in extremis, the clash of forces in the night: they are the Divine Comedy and the journey of King Lear. The edifice that contains them comes from art, but in itself is emptiness. The walls of the Chalcidian rock stare blankly at us, with their hundred open, silent mouths. The corridors of the maze are mere repetition. Even the honeycomb without its bees is only mathematical form, dead beauty. When the spirit enters it the building shakes and roars, the brazen bull sends out screams and cries. Bound in form, we marvel at the great spires and the curving arches and the rose windows of the cathedral. The temple is authority. Michelangelo paints the ceilings there. His sculptures sprawl on the tombs. Beethoven is its presiding composer. Aeschylus watches over its voices. The soul turned inside out is the cathedral and the maze. The temple and the labyrinth are Apollo’s resting places, the pedestals where the god stands and accepts homage from an awed humanity.

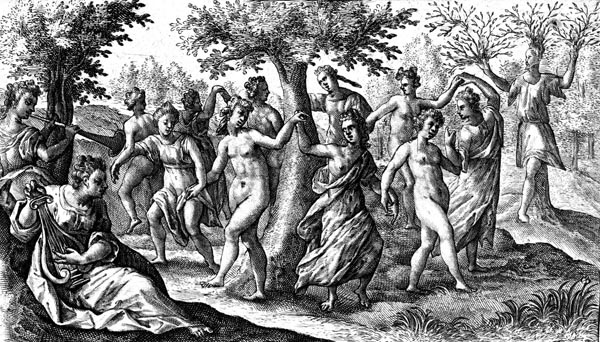

But Daedalus in Crete first of all remembered the Goddess, as he remembered her at the last, in Sicily. In Crete he made for her, as Ariadne, that dancing floor, where Cretan feet celebrated the flow of life, the fluidity of transience. The dance is life. Its music is Mozartian: its scenery is Venetian or Impressionist. Its repetitions are echoes, but each pattern is subtly different. Performed in the light of day, where nothing is concealed, it has its co-ordinated movements and its ‘soliloquies’. Every sequence is a story in itself, a flexible unfolding of a character or a moment. But the accumulation of sequences is the greater tale, the revelation of the goddess, her tenderness, her living beauty, her feminine grace, her promise of repeated, yet unique, and endless loving creation. ‘They were dancing…’ says Sappho (LP 1.a.16). It is Crete where she imagines the goddess to be when she calls to her, to lovely Aphrodite, calling her to the place where ‘far off, beyond the apple branches, cool streams murmur, and the roses shadow every corner…’ (LP 2). We can still call the Goddess from Crete. She is art, as Mandelstam recognised her in his poem ‘Silentium’, that poem of the sparkling Aegean sea, ‘She has not yet been born: she is music and word, and, therefore, the un-torn fabric of what is stirred’.

Daedalus was the first artist, the first great creator: the man who gave us the dancing floor on which the Goddess can appear. And at the end he made the golden honeycomb for her. He invented the ‘lost wax’ method, the clay mould around the bees’ structure of wax, wax that is made of the pollen of the flowers, the inspiration of life and imagination: heated by the energy of art, until the wax melts and is drawn off: and the mould is filled with molten metal, then cooled: the clay mould is broken away, the honeycomb transformed to gold. Slowly, myth after myth, Ovid fills the honeycomb of the Metamorphoses, cell by cell, filling the spaces of time, threading the levels and layers of the comb, transforming the tales to gold. The god roars in his temple, the bull bellows at the heart of the labyrinth, but here the Goddess dances across the shining floor, and the golden honeycomb drips the pure honey of the dancing bees, those intoxicated, beautiful, obsessive creatures, whose dance points the way to the meadows, the flowers, and the pollen. Some are left behind too, dead bees, living works, the traces of the artist, threaded on the necklace of the Goddess, the line of the creators, from ancient times till now. ‘For joy’s sake take my strange gift,’ says Mandelstam, ‘this simple thread of dead, dried bees, turned honey in the sun’. Don’t go to Ovid for the temple, look for that elsewhere. Ovid is the dance.

‘The Apulian Shepherd’