Ovid: The Metamorphoses

Book II

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Bk II:1-30 The Palace of the Sun

- Bk II:31-48 Phaethon and his father

- Bk II:49-62 The Sun’s admonitions

- Bk II:63-89 His further warnings

- Bk II:90-110 Phaethon insists on driving the chariot

- Bk II:111-149 The Sun’s instructions

- Bk II:150-177 The Horses run wild

- Bk II:178-200 Phaethon lets go of the reins

- Bk II:201-226 The mountains burn

- Bk II:227-271 The rivers are dried up

- Bk II:272-300 Earth complains

- Bk II:301-328 Jupiter intervenes and Phaethon dies

- Bk II:329-343 Phaethon’s sisters grieve for him

- Bk II:344-366 The sisters turned into poplar trees

- Bk II:367-380 Cycnus

- Bk II:381-400 The Sun returns to his task

- Bk II:401-416 Jupiter sees Callisto

- Bk II:417-440 Jupiter rapes Callisto

- Bk II:441-465 Diana discover’s Callisto’s shame

- Bk II:466-495 Callisto turned into a bear

- Bk II:496-507 Arcas and Callisto become constellations

- Bk II:508-530 Juno complains to Tethys and Oceanus

- Bk II:531-565 The Raven and the Crow

- Bk II:566-595 The Crow’s story

- Bk II:596-611 Coronis is betrayed and Phoebus kills her

- Bk II:612-632 Phoebus repents and saves Aesculapius

- Bk II:633-675 Chiron and Ocyrhoë’s prophecies

- Bk II:676-707 Mercury, Battus and the stolen cattle

- Bk II:708-736 Mercury sees Herse

- Bk II:737-751 Mercury elicits the help of Aglauros

- Bk II:752-786 Minerva calls on Envy

- Bk II:787-811 Envy poisons Aglauros’s heart

- Bk II:812-832 Aglauros is turned to stone

- Bk II:833-875 Jupiter’s abduction of Europa

Bk II:1-30 The Palace of the Sun

The palace of the Sun towered up with raised columns, bright with glittering gold, and gleaming bronze like fire. Shining ivory crowned the roofs, and the twin doors radiated light from polished silver. The work of art was finer than the material: on the doors Mulciber had engraved the waters that surround the earth’s centre, the earthly globe, and the overarching sky. The dark blue sea contains the gods, melodious Triton, shifting Proteus, Aegaeon crushing two huge whales together, his arms across their backs, and Doris with her daughters, some seen swimming, some sitting on rocks drying their sea-green hair, some riding the backs of fish. They are neither all alike, nor all different, just as sisters should be. The land shows men and towns, woods and creatures, rivers and nymphs and other rural gods. Above them was an image of the glowing sky, with six signs of the zodiac on the right hand door and the same number on the left.

As soon as Clymene’s son had climbed the steep path there, and entered the house of this parent of whose relationship to himself he was uncertain, he immediately made his way into his father’s presence, but stopped some way off, unable to bear his light too close. Wearing a purple robe, Phoebus sat on a throne shining with bright emeralds. To right and left stood the Day, Month, and Year, the Century and the equally spaced Hours. Young Spring stood there circled with a crown of flowers, naked Summer wore a garland of ears of corn, Autumn was stained by the trodden grapes, and icy Winter had white, bristling hair.

Bk II:31-48 Phaethon and his father

The Sun, seated in the middle of them, looked at the boy, who was fearful of the strangeness of it all, with eyes that see everything, and said ‘What reason brings you here? What do you look for on these heights, Phaethon, son that no father need deny?’ Phaethon replied ‘Universal light of the great world, Phoebus, father, if you let me use that name, if Clymene is not hiding some fault behind false pretence, give me proof father, so they will believe I am your true offspring, and take away this uncertainty from my mind!’ He spoke, and his father removed the crown of glittering rays from his head and ordered him to come nearer. Embracing him, he said ‘It is not to be denied you are worthy to be mine, and Clymene has told you the truth of your birth. So that you can banish doubt, ask for any favour, so that I can grant it to you. May the Stygian lake, that my eyes have never seen, by which the gods swear, witness my promise.’ Hardly had he settled back properly in his seat when the boy asked for his father’s chariot and the right to control his wing-footed horses for a day.

Bk II:49-62 The Sun’s admonitions

His father regretted his oath. Three times, and then a fourth, shaking his bright head, he said ‘Your words show mine were rash; if only it were right to retract my promise! I confess my boy I would only refuse you this one thing. It is right to dissuade you. What you want is unsafe. Phaethon you ask too great a favour, and one that is unfitting for your strength and boyish years. Your fate is mortal: it is not mortal what you ask. Unknowingly you aspire to more than the gods can share. Though each deity can please themselves, within what is allowed, no one except myself has the power to occupy the chariot of fire. Even the lord of mighty Olympus, who hurls terrifying lightning-bolts from his right hand, cannot drive this team, and who is greater than Jupiter?’

Bk II:63-89 His further warnings

‘The first part of the track is steep, and one that my fresh horses at dawn can hardly climb. In mid-heaven it is highest, where to look down on earth and sea often alarms even me, and makes my heart tremble with awesome fear. The last part of the track is downwards and needs sure control. Then even Tethys herself, who receives me in her submissive waves, is accustomed to fear that I might dive headlong. Moreover the rushing sky is constantly turning, and drags along the remote stars, and whirls them in rapid orbits. I move the opposite way, and its momentum does not overcome me as it does all other things, and I ride contrary to its swift rotation. Suppose you are given the chariot. What will you do? Will you be able to counter the turning poles so that the swiftness of the skies does not carry you away? Perhaps you conceive in imagination that there are groves there and cities of the gods and temples with rich gifts. The way runs through ambush, and apparitions of wild beasts! Even if you keep your course, and do not steer awry, you must still avoid the horns of Taurus the Bull, Sagittarius the Haemonian Archer, raging Leo and the Lion’s jaw, Scorpio’s cruel pincers sweeping out to encircle you from one side, and Cancer’s crab-claws reaching out from the other. You will not easily rule those proud horses, breathing out through mouth and nostrils the fires burning in their chests. They scarcely tolerate my control when their fierce spirits are hot, and their necks resist the reins. Beware my boy, that I am not the source of a gift fatal to you, while something can still be done to set right your request!’

Bk II:90-110 Phaethon insists on driving the chariot

‘No doubt, since you ask for a certain sign to give you confidence in being born of my blood, I give you that sure sign by fearing for you, and show myself a father by fatherly anxiety. Look at me. If only you could look into my heart, and see a father’s concern from within! Finally, look around you, at the riches the world holds, and ask for anything from all of the good things in earth, sea, and sky. I can refuse you nothing. Only this one thing I take exception to, which would truly be a punishment and not an honour. Phaethon, you ask for punishment as your reward! Why do you unknowingly throw your coaxing arms around my neck? Have no doubt! Whatever you ask will be given, I have sworn it by the Stygian streams, but make a wiser choice!’

The warning ended, but Phaethon still rejected his words, and pressed his purpose, blazing with desire to drive the chariot. So, as he had the right, his father led the youth to the high chariot, Vulcan’s work. It had an axle of gold, and a gold chariot pole, wheels with golden rims, and circles of silver spokes. Along the yoke chrysolites and gemstones, set in order, glowed with brilliance reflecting Phoebus’s own light.

Bk II:111-149 The Sun’s instructions

Now while brave Phaethon is gazing in wonder at the workmanship, see, Aurora, awake in the glowing east, opens wide her bright doors, and her rose-filled courts. The stars, whose ranks are shepherded by Lucifer the morning star, vanish, and he, last of all, leaves his station in the sky.

When Titan saw his setting, as the earth and skies were reddening, and just as the crescent of the vanishing moon faded, he ordered the swift Hours to yoke his horses. The goddesses quickly obeyed his command, and led the team, sated with ambrosial food and breathing fire, out of the tall stables, and put on their ringing harness. Then the father rubbed his son’s face with a sacred ointment, and made it proof against consuming flames, and placed his rays amongst his hair, and foreseeing tragedy, and fetching up sighs from his troubled heart, said ‘If you can at least obey your father’s promptings, spare the whip, boy, and rein them in more strongly! They run swiftly of their own accord. It is a hard task to check their eagerness. And do not please yourself, taking a path straight through the five zones of heaven! The track runs obliquely in a wide curve, and bounded by the three central regions, avoids the southern pole and the Arctic north. This is your road, you will clearly see my wheel-marks, and so that heaven and earth receive equal warmth, do not sink down too far or heave the chariot into the upper air! Too high and you will scorch the roof of heaven: too low, the earth. The middle way is safest.

Nor must you swerve too far right towards writhing Serpens, nor lead your wheels too far left towards sunken Ara. Hold your way between them! I leave the rest to Fortune, I pray she helps you, and takes better care of you than you do yourself. While I have been speaking, dewy night has touched her limit on Hesperus’s far western shore. We have no time for freedom! We are needed: Aurora, the dawn, shines, and the shadows are gone. Seize the reins in your hand, or if your mind can be changed, take my counsel, do not take my horses! While you can, while you still stand on solid ground, before unknowingly you take to the chariot you have unluckily chosen, let me light the world, while you watch in safety!

Bk II:150-177 The Horses run wild

The boy has already taken possession of the fleet chariot, and stands proudly, and joyfully, takes the light reins in his hands, and thanks his unwilling father.

Meanwhile the sun’s swift horses, Pyroïs, Eoüs, Aethon, and the fourth, Phlegon, fill the air with fiery whinnying, and strike the bars with their hooves. When Tethys, ignorant of her grandson’s fate, pushed back the gate, and gave them access to the wide heavens, rushing out, they tore through the mists in the way with their hooves and, lifted by their wings, overtook the East winds rising from the same region. But the weight was lighter than the horses of the Sun could feel, and the yoke was free of its accustomed load. Just as curved-sided boats rock in the waves without their proper ballast, and being too light are unstable at sea, so the chariot, free of its usual burden, leaps in the air and rushes into the heights as though it were empty.

As soon as they feel this the team of four run wild and leave the beaten track, no longer running in their pre-ordained course. He was terrified, unable to handle the reins entrusted to him, not knowing where the track was, nor, if he had known, how to control the team. Then for the first time the chill stars of the Great and Little Bears, grew hot, and tried in vain to douse themselves in forbidden waters. And the Dragon, Draco, that is nearest to the frozen pole, never formidable before and sluggish with the cold, now glowed with heat, and took to seething with new fury. They say that you Bootës also fled in confusion, slow as you are and hampered by the Plough.

Bk II:178-200 Phaethon lets go of the reins

When the unlucky Phaethon looked down from the heights of the sky at the earth far, far below he grew pale and his knees quaked with sudden fear, and his eyes were robbed of shadow by the excess light. Now he would rather he had never touched his father’s horses, and regrets knowing his true parentage and possessing what he asked for. Now he wants only to be called Merops’s son, as he is driven along like a ship in a northern gale, whose master lets go the ropes, and leaves her to prayer and the gods. What can he do? Much of the sky is now behind his back, but more is before his eyes. Measuring both in his mind, he looks ahead to the west he is not fated to reach and at times back to the east. Dazed he is ignorant how to act, and can neither grasp the reins nor has the power to loose them, nor can he change course by calling the horses by name. Also, alarmed, he sees the marvellous forms of huge creatures everywhere in the glowing sky. There is a place where Scorpio bends his pincers in twin arcs, and, with his tail and his curving arms stretched out to both sides, spreads his body and limbs over two star signs. When the boy saw this monster drenched with black and poisonous venom threatening to wound him with its arched sting, robbed of his wits by chilling horror, he dropped the reins.

Bk II:201-226 The mountains burn

When the horses feel the reins lying across their backs, after he has thrown them down, they veer off course and run unchecked through unknown regions of the air. Wherever their momentum takes them there they run, lawlessly, striking against the fixed stars in deep space and hurrying the chariot along remote tracks. Now they climb to the heights of heaven, now rush headlong down its precipitous slope, sweeping a course nearer to the earth. The Moon, amazed, sees her brother’s horses running below her own, and the boiling clouds smoke. The earth bursts into flame, in the highest regions first, opens in deep fissures and all its moisture dries up. The meadows turn white, the trees are consumed with all their leaves, and the scorched corn makes its own destruction. But I am bemoaning the lesser things. Great cities are destroyed with all their walls, and the flames reduce whole nations with all their peoples to ashes. The woodlands burn, with the hills. Mount Athos is on fire, Cilician Taurus, Tmolus, Oete and Ida, dry now once covered with fountains, and Helicon home of the Muses, and Haemus not yet linked with King Oeagrius’s name. Etna blazes with immense redoubled flames, the twin peaks of Parnassus, Eryx, Cynthus, Othrys, Rhodope fated at last to lose its snow, Mimas and Dindyma, Mycale and Cithaeron, ancient in rites. Its chilly climate cannot save Scythia. The Caucasus burn, and Ossa along with Pindus, and Olympos greater than either, and the lofty Alps and cloud-capped Apennines.

Bk II:227-271 The rivers are dried up

Then, truly, Phaethon sees the whole earth on fire. He cannot bear the violent heat, and he breathes the air as if from a deep furnace. He feels his chariot glowing white. He can no longer stand the ash and sparks flung out, and is enveloped in dense, hot smoke. He does not know where he is, or where he is going, swept along by the will of the winged horses.

It was then, so they believe, that the Ethiopians acquired their dark colour, since the blood was drawn to the surface of their bodies. Then Libya became a desert, the heat drying up her moisture. Then the nymphs with dishevelled hair wept bitterly for their lakes and fountains. Boeotia searches for Dirce’s rills, Argos for Amymone’s fountain, Corinth for the Pirenian spring. Nor are the rivers safe because of their wide banks. The Don turns to steam in mid-water, and old Peneus, and Mysian Caicus and swift-flowing Ismenus, Arcadian Erymanthus, Xanthus destined to burn again, golden Lycormas and Maeander playing in its watery curves, Thracian Melas and Laconian Eurotas. Babylonian Euphrates burns. Orontes burns and quick Thermodon, Ganges, Phasis, and Danube. Alpheus boils. Spercheos’s banks are on fire. The gold that the River Tagus carries is molten with the fires, and the swans for whose singing Maeonia’s riverbanks are famous, are scorched in Caÿster’s midst. The Nile fled in terror to the ends of the earth, and hid its head that remains hidden. Its seven mouths are empty and dust-filled, seven channels without a stream.

The same fate parches the Thracian rivers, Hebrus and Strymon, and the western rivers, Rhine, Rhone, Po and the Tiber who had been promised universal power. Everywhere the ground breaks apart, light penetrates through the cracks down into Tartarus, and terrifies the king of the underworld and his queen. The sea contracts and what was a moment ago wide sea is a parched expanse of sand. Mountains emerge from the water, and add to the scattered Cyclades. The fish dive deep, and the dolphins no longer dare to rise arcing above the water, as they have done, into the air. The lifeless bodies of seals float face upwards on the deep. They even say that Nereus himself, and Doris and her daughters drifted through warm caves. Three times Neptune tried to lift his fierce face and arms above the waters. Three times he could not endure the burning air.

Bk II:272-300 Earth complains

Nevertheless, kindly Earth, surrounded as she was by sea, between the open waters and the dwindling streams that had buried themselves in their mother’s dark womb, lifted her smothered face. Putting her hand to her brow, and shaking everything with her mighty tremors, she sank back a little lower than she used to be, and spoke in a faint voice ‘If this pleases you, if I have deserved it, O king of the gods, why delay your lightning bolts? If it is right for me to die through the power of fire, let me die by your fire and let the doer of it lessen the pain of the deed! I can hardly open my lips to say these words’ (the heat was choking her). Look at my scorched hair and the ashes in my eyes, the ashes over my face! Is this the honour and reward you give me for my fruitfulness and service, for carrying wounds from the curved plough and the hoe, for being worked throughout the year, providing herbage and tender grazing for the flocks, produce for the human race and incense to minister to you gods?

Even if you find me deserving of ruin, what have the waves done, why does your brother deserve this? Why are the waters that were his share by lot diminished and so much further from the sky? If neither regard for me or for your brother moves you pity at least your own heavens! Look around you on either side: both the poles are steaming! If the fire should melt them, your own palace will fall! Atlas himself is suffering, and can barely hold up the white-hot sky on his shoulders! If the sea and the land and the kingdom of the heavens are destroyed, we are lost in ancient chaos! Save whatever is left from the flames, and think of our common interest!’

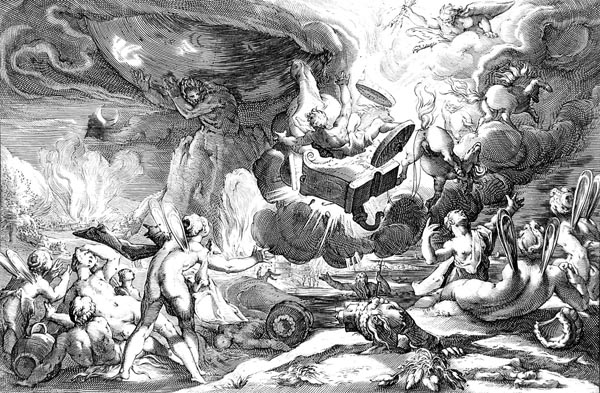

Bk II:301-328 Jupiter intervenes and Phaethon dies

So the Earth spoke, and unable to tolerate the heat any longer or speak any further, she withdrew her face into her depths closer to the caverns of the dead. But the all-powerful father of the gods climbs to the highest summit of heaven, from where he spreads his clouds over the wide earth, from where he moves the thunder and hurls his quivering lightning bolts, calling on the gods, especially on him who had handed over the sun chariot, to witness that, unless he himself helps, the whole world will be overtaken by a ruinous fate. Now he has no clouds to cover the earth, or rain to shower from the sky. He thundered, and balancing a lightning bolt in his right hand threw it from eye-level at the charioteer, removing him, at the same moment, from the chariot and from life, extinguishing fire with fierce fire. Thrown into confusion the horses, lurching in different directions, wrench their necks from the yoke and throw off the broken harness. Here the reins lie, there the axle torn from the pole, there the spokes of shattered wheels, and the fragments of the wrecked chariot are flung far and wide.

But Phaethon, flames ravaging his glowing hair, is hurled headlong, leaving a long trail in the air, as sometimes a star does in the clear sky, appearing to fall although it does not fall. Far from his own country, in a distant part of the world, the river god Eridanus takes him from the air, and bathes his smoke-blackened face. There the Italian nymphs consign his body, still smoking from that triple-forked flame, to the earth, and they also carve a verse in the rock:

HERE PHAETHON LIES WHO THE SUN’S JOURNEY MADE

DARED ALL THOUGH HE BY WEAKNESS WAS BETRAYED

Bk II:329-343 Phaethon’s sisters grieve for him

Now the father, pitiful, ill with grief, hid his face, and, if we can believe it, a whole day went by without the sun. But the fires gave light, so there was something beneficial amongst all that evil. But Clymene, having uttered whatever can be uttered at such misfortune, grieving and frantic and tearing her breast, wandered over the whole earth first looking for her son’s limbs, and then failing that his bones. She found his bones already buried however, beside the riverbank in a foreign country. Falling to the ground she bathed with tears the name she could read on the cold stone and warmed it against her naked breast. The Heliads, her daughters and the Sun’s, cry no less, and offer their empty tribute of tears to the dead, and, beating their breasts with their hands, they call for their brother night and day, and lie down on his tomb, though he cannot hear their pitiful sighs.

Bk II:344-366 The sisters turned into poplar trees

Four times the moon had joined her crescent horns to form her bright disc. They by habit, since use creates habit, devoted themselves to mourning. Then Phaethüsa, the eldest sister, when she tried to throw herself to the ground, complained that her ankles had stiffened, and when radiant Lampetia tried to come near her she was suddenly rooted to the spot. A third sister attempting to tear at her hair pulled out leaves. One cried out in pain that her legs were sheathed in wood, another that her arms had become long branches. While they wondered at this, bark closed round their thighs and by degrees over their waists, breasts, shoulders, and hands, and all that was left free were their mouths calling for their mother. What can their mother do but go here and there as the impulse takes her, pressing her lips to theirs where she can? It is no good. She tries to pull the bark from their bodies and break off new branches with her hands, but drops of blood are left behind like wounds. ‘Stop, mother, please’ cries out whichever one she hurts, ‘Please stop: It is my body in the tree you are tearing. Now, farewell.’ and the bark closed over her with her last words. Their tears still flow, and hardened by the sun, fall as amber from the virgin branches, to be taken by the bright river and sent onwards to adorn Roman brides.

Bk II:367-380 Cycnus

Cycnus, the son of Sthenelus witnessed this marvel, who though he was kin to you Phaethon, through his mother, was closer still in love. Now, though he had ruled the people and great cities of Liguria, he left his kingdom, and filled Eridanus’s green banks and streams, and the woods the sisters had become part of, with his grief. As he did so his voice vanished and white feathers hid his hair, his long neck stretched out from his body, his reddened fingers became webbed, wings covered his sides, and a rounded beak his mouth. So Cycnus became a new kind of bird, the swan. But he had no faith in Jupiter and the heavens, remembering the lightning bolt the god in his severity had hurled. He looked for standing water, and open lakes hating fire, choosing to live in floods rather than flames.

Bk II:381-400 The Sun returns to his task

Meanwhile Phaethon’s father, mourning and without his accustomed brightness, as if in eclipse, hated the light, himself and the day. He gave his mind over to grief, and to grief added his anger, and refused to provide his service to the earth. ‘Enough’ he says ‘since the beginning, my task has given me no rest and I am weary of work without end and labour without honour! Whoever chooses to can steer the chariot of light! If no one does, and all the gods acknowledge they cannot, let Jupiter himself do it, so that for a while at least, while he tries to take the reins, he must put aside the lightning bolts that leave fathers bereft! Then he will know when he has tried the strength of those horses, with hooves of fire, that the one who failed to rule them well did not deserve to be killed.’

All the gods gather round Sol, as he talks like this, and beg him not to shroud everything with darkness. Jupiter himself tries to excuse the fire he hurled, adding threats to his entreaties as kings do. Then Phoebus rounds up his horses, maddened and still trembling with terror, and in pain lashes out at them with goad and whip (really lashes out) reproaching them and blaming them for his son’s death.

Bk II:401-416 Jupiter sees Callisto

Now the all-powerful father of the gods circuits the vast walls of heaven and examines them to check if anything has been loosened by the violent fires. When he sees they are as solid and robust as ever he inspects the earth and the works of humankind. Arcadia above all is his greatest care. He restores her fountains and streams, that are still hardly daring to flow, gives grass to the bare earth, leaves to the trees, and makes the scorched forests grow green again.

Often, as he came and went, he would stop short at the sight of a girl from Nonacris, feeling the fire take in the very marrow of his bones. She was not one to spin soft wool or play with her hair. A clasp fastened her tunic, and a white ribbon held back her loose tresses. Dressed like this, with a spear or a bow in her hand, she was one of Diana’s companions. No nymph who roamed Maenalus was dearer to Trivia, goddess of the crossways, than she, Callisto, was. But no favour lasts long.

Bk II:417-440 Jupiter rapes Callisto

The sun was high, just path the zenith, when she entered a grove that had been untouched through the years. Here she took her quiver from her shoulder, unstrung her curved bow, and lay down on the grass, her head resting on her painted quiver. Jupiter, seeing her there weary and unprotected, said ‘Here, surely, my wife will not see my cunning, or if she does find out it is, oh it is, worth a quarrel!’ Quickly he took on the face and dress of Diana, and said ‘Oh, girl who follows me, where in my domains have you been hunting?’

The virgin girl got up from the turf replying ‘Greetings, goddess greater than Jupiter: I say it even though he himself hears it.’ He did hear, and laughed, happy to be judged greater than himself, and gave her kisses unrestrainedly, and not those that virgins give. When she started to say which woods she had hunted he embraced and prevented her and not without committing a crime. Face to face with him, as far as a woman could, (I wish you had seen her Juno: you would have been kinder to her) she fought him, but how could a girl win, and who is more powerful than Jove? Victorious, Jupiter made for the furthest reaches of the sky: while to Callisto the grove was odious and the wood seemed knowing. As she retraced her steps she almost forgot her quiver and its arrows, and the bow she had left hanging.

Bk II:441-465 Diana discover’s Callisto’s shame

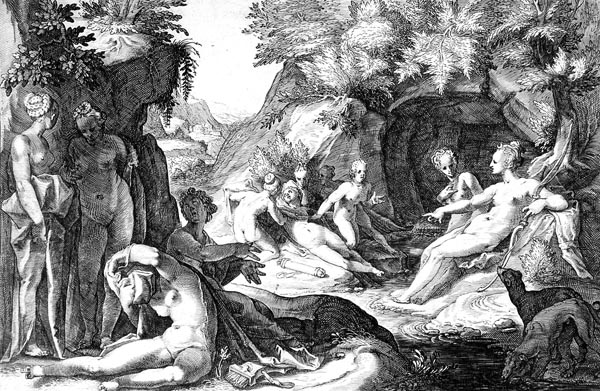

Behold how Diana, with her band of huntresses, approaching from the heights of Maenalus, magnificent from the kill, spies her there, and seeing her calls out. At the shout she runs, afraid at first in case it is Jupiter disguised, but when she sees the other nymphs come forward she realises there is no trickery and joins their number. Alas! How hard it is not to show one’s guilt in one’s face! She can scarcely lift her eyes from the ground, not as she used to be, wedded to her goddess’s side or first of the whole company, but is silent and by her blushing shows signs of her shame at being attacked. Even if she were not herself virgin, Diana could sense her guilt in a thousand ways. They say all the nymphs could feel it.

Nine crescent moons had since grown full when the goddess faint from the chase in her brother’s hot sunlight found a cool grove out of which a murmuring stream ran, winding over fine sand. She loved the place and tested the water with her foot. Pleased with this too she said ‘Any witness is far away, let’s bathe our bodies naked in the flowing water.’ The Arcadian girl blushed: all of them took off their clothes: one of them tried to delay: hesitantly the tunic was removed and there her shame was revealed with her naked body. Terrified she tried to conceal her swollen belly. Diana cried ‘Go, far away from here: do not pollute the sacred fountain!’ and the Moon-goddess commanded her to leave her band of followers.

Bk II:466-495 Callisto turned into a bear

The great Thunderer’s wife had known about all this for a long time and had held back her severe punishment until the proper time. Now there was no reason to wait. The girl had given birth to a boy, Arcas, and that in itself enraged Juno. When she turned her angry eyes and mind to thought of him she cried out ‘Nothing more was needed, you adulteress, than your fertility, and your marking the insult to me by giving birth, making public my Jupiter’s crime. You’ll not carry this off safely. Now, insolent girl, I will take that shape away from you, that pleased you and my husband so much!’ At this she clutched her in front by the hair of her forehead and pulled her face forwards onto the ground. Callisto stretched out her arms for mercy: those arms began to bristle with coarse black hairs: her hands arched over and changed into curved claws to serve as feet: and her face, that Jupiter had once praised, was disfigured by gaping jaws: and so that her prayers and words of entreaty might not attract him her power of speech was taken from her. An angry, threatening growl, harsh and terrifying, came from her throat. Still her former feelings remained intact though she was now a bear. She showed her misery in continual groaning, raising such hands as she had left to the starry sky, feeling, though she could not speak it, Jupiter’s indifference. Ah, how often she wandered near the house and fields that had once been her home, not daring to sleep in the lonely woods! Ah, how often she was driven among the rocks by the baying hounds, and the huntress fled in fear from the hunters! Often she hid at the sight of wild beasts forgetting what she was, and though a bear she shuddered at the sight of other bears on the mountains and feared the wolves though her father Lycaon ran with them.

Bk II:496-507 Arcas and Callisto become constellations

And now Arcas, grandson of Lycaon, had reached his fifteenth year ignorant of his parentage. While he was hunting wild animals, while he was finding suitable glades and penning up the Erymanthian groves with woven nets, he came across his mother, who stood still at sight of Arcas and appeared to know him. He shrank back from those unmoving eyes gazing at him so fixedly, uncertain what made him afraid, and when she quickly came nearer he was about to pierce her chest with his lethal spear. All-powerful Jupiter restrained him and in the same moment removed them and the possibility of that wrong, and together, caught up through the void on the winds, he set them in the heavens and made them similar constellations, the Great and Little Bear.

Bk II:508-530 Juno complains to Tethys and Oceanus

Juno was angered when she saw his inamorato shining among the stars, and went down into the waters to white-haired Tethys and old Oceanus to whom the gods often make reverence. When they asked her the reason for her visit she began ‘You ask me why I, the queen of the gods, have left my home in the heavens to be here? Another has taken my place in the sky! I tell a lie, if you do not see, when night falls and the world darkens, newly exalted stars to wound me, set in the sky, where the remotest and shortest orbit circles the uttermost pole. Why should anyone wish to avoid wounding Juno or dread my enmity if I only benefit those I harm? Oh what a great achievement! Oh what marvellous powers I have! I stopped her being human and she becomes a goddess! This is the punishment I inflict on the guilty! This is my wonderful sovereignty! Let him take away her animal form and restore her former beauty as he did before with that Argive girl, Io. Why not divorce Juno, install her in my place, and let Lycaon be his father-in-law? If this contemptible insult to your foster-child moves you, shut out the seven stars of the Bear from your dark blue waters, repulse this constellation set in the heavens as a reward for her defilement, and do not let my rival dip in your pure flood!’

Bk II:531-565 The Raven and the Crow

The gods of the sea nodded their consent. Then Saturnia, in her light chariot drawn by painted peacocks, drove up through the clear air. These peacocks had only recently been painted, when Argus was killed, at the same time that your wings, Corvus, croaking Raven, were suddenly changed to black, though they were white before. He was once a bird with silver-white plumage, equal to the spotless doves, not inferior to the geese, those saviours of the Capitol with their watchful cries, or the swan, the lover of rivers. His speech condemned him. Because of his ready speech he, who was once snow white, was now white’s opposite.

Coronis of Larissa was the loveliest girl in all Thessaly. Certainly she pleased you, god of Delphi. Well, as long as she was faithful, or not caught out. But that bird of Phoebus discovered her adultery and, merciless informer, flew straight to his master to reveal the secret crime. The garrulous Crow followed with flapping wings, wanting to know everything, but when he heard the reason, he said ‘This journey will do you no good: don’t ignore my prophecy! See what I was, see what I am, and search out the justice in it. Truth was my downfall.’

Once upon a time Pallas hid a child, Erichthonius, born without a human mother, in a box made of Actaean osiers. She gave this to the three virgin daughters of two-natured Cecrops, who was part human part serpent, and ordered them not to pry into its secret. Hidden in the light leaves that grew thickly over an elm-tree I set out to watch what they might do. Two of the girls, Pandrosus and Herse, obeyed without cheating, but the third Aglauros called her sisters cowards and undid the knots with her hand, and inside they found a baby boy with a snake stretched out next to him. That act I betrayed to the goddess. And this is the reward I got for it, no longer consecrated to Minerva’s protection, and ranked below the Owl, that night-bird! My punishment should be a warning to all birds not to take risks by speaking out.’

Bk II:566-595 The Crow’s story

‘And just think, not only had I not asked for her favour, she had sought me out, of her own accord! – Ask Pallas herself: though she is angry, she will not deny it even in anger. The famous Coroneus was my father, in the land of Phocis (it is said to be well known) and I was a royal virgin and wealthy princes courted me (so do not disparage me). But my beauty hurt me. Once when I was walking slowly as I used to do along the crest of the sands by the shore the sea-god saw me and grew hot. When his flattering words and entreaties proved a waste of time, he tried force, and chased after me. I ran, leaving the solid shore behind, tiring myself out uselessly in the soft sand. Then I called out to gods and men. No mortal heard my voice, but the virgin goddess feels pity for a virgin and she helped me. I was stretching out my arms to the sky: those arms began to darken with soft plumage. I tried to lift my cloak from my shoulders but it had turned to feathers with roots deep in my skin. I tried to beat my naked breast with my hands but found I had neither hands nor naked breast.

I ran, and now the sand did not clog my feet as before but I lifted from the ground, and soon sailed high into the air. So I became an innocent servant of Minerva. But what use was that to me if Nyctimene, who was turned into an Owl for her dreadful sins, has usurped my place of honour? Or have you not heard the story all Lesbos knows well, how Nyctimene desecrated her father’s bed? Though she is now a bird she is conscious of guilt at her crime and flees from human sight and the light, and hides her shame in darkness, and is driven from the whole sky by all the birds.’

Bk II:596-611 Coronis is betrayed and Phoebus kills her

To all this, the Raven replied ‘I pray any evil be on your own head. I spurn empty prophecies’ and, completing the journey he had started, he told his master he had seen Coronis lying beside a Thessalian youth. The laurel fell from the lover’s head on hearing of the charge, his expression and colour and the tone of his lyre changed, and his mind boiled with growing anger. He seized his usual weapons, strung his bow bending it by the tips, and, with his unerring arrow, pierced the breast that had so often been close to his own. She groaned at the wound, and as the arrow was drawn out her white limbs were drenched with scarlet blood and she cried out ‘Oh Phoebus it was in your power to have punished me, but to have let me give birth first: now two will die in one.’ She spoke, and then her life flowed out with her blood. A deathly cold stole over her body, emptied of being.

Bk II:612-632 Phoebus repents and saves Aesculapius

Alas! Too late the lover repents of his cruel act, and hates himself for listening to the tale that has so angered him. He hates the bird that has compelled him to know of the fault that brought him pain. He hates the bow, his hand, and the hastily fired arrow as well as that hand. He cradles the fallen girl and attempts to overcome fate with his healing powers. It is too late, and he tries his arts in vain. Later, when all efforts had failed, seeing the funeral pyre prepared to consume her body, then indeed the god groaned from the depths of his heart (since the faces of the heavenly gods cannot be touched by tears), groans no different from those of a young bullock, seeing the hammer poised at the slaughterer’s right ear, crash down on the hollow forehead of a suckling calf.

Even though she cannot know of it, the god pours fragrant incense over her breast, and embraces her body, and unjustly, performs the just rites. He could not let a child of Phoebus be destroyed in the same ruin, and he tore his son, Aesculapius, from its mother’s womb and from the flames, and carried him to the cave of Chiron the Centaur, who was half man and half horse. But he stopped the Raven, who had hoped for a reward for telling the truth, from living among the white birds.

Bk II:633-675 Chiron and Ocyrhoë’s prophecies

The semi-human was pleased with this foster-child of divine origin, glad at the honour it brought him, when his daughter suddenly appeared, her shoulders covered with her long red hair, whom the nymph Chariclo called Ocyrhoë, having given birth to her on the banks of that swift stream. She was not content merely to have learned her father’s arts, she also chanted the secrets of the Fates.

So when she felt the prophetic frenzy in her mind, and was on fire with the god enclosed in her breast, she looked at the infant boy and cried out ‘Grow and thrive, child, healer of all the world! Human beings will often be in your debt, and you will have the right to restore the dead. But if ever it is done regardless of the god’s displeasure you will be stopped, by the flame of your grandfather’s lightning bolt, from doing so again. From a god you will turn to a bloodless corpse, and then to a god who was a corpse, and so twice renew your fate.

You also, dear father, now immortal, and created by the law of your birth to live on through all the ages, will long for death, when you are tormented by the terrible venom of the Serpent, Hydra, absorbed through your wounded limbs. But at last the gods will give you the power to die, and the Three Goddesses will sever the thread.’ Other prophecies remained to tell: but she sighed deeply, distressed by the tears welling from her eyes, and cried ‘The Fates prevent me, and forbid me further speech. My throat is constricted. These arts are not worth the cost if they incur the gods’ anger against me. Better not to know the future! Now I see my human shape being taken away, now grass contents me for food, now my impulse is to race over the wide fields. I am changing to a mare, the form of my kindred. But why am I completely so? Surely my father is still half human.’ Even as she spoke, the last part of her complaint was hard to understand and her words were troubled. Soon they seemed neither words nor a horse’s neighs, but the imitation of a horse. In a little while she gave out clear whinnying noises, and her arms moved in the grass. Then her fingers came together and one thin solid hoof of horn joined her five fingernails. Her head and the length of her neck extended, the greater part of her long gown became a tail, and the loose hair thrown over her neck hung down as a mane on her right shoulder. Now she was altered in both voice and features, and from this marvellous happening she gained a new name.

Bk II:676-707 Mercury, Battus and the stolen cattle

The demi-god, son of Philyra, wept, and called to you for help in vain, O lord of Delphi. You could not re-call mighty Jupiter’s command, and, if you had been able to, you were not there. You lived in Elis and the Messenian lands. That was the time when you wore a shepherd’s cloak, carried a wooden crook in your left hand, and in the other a pipe of seven disparate reeds. And while your thoughts were of love, while you played sweetly on your pipe, your cattle, unguarded, strayed, it is said, into the Pylian fields. There, Mercury Atlantiades, son of Maia, saw them and by his arts drove them into the woods and hid them there. Nobody saw the theft except one old man, well known in that country, whom they called Battus. He served as guardian of a herd of pedigree mares, for a wealthy man Neleus, in the rich meadows and woodland pastures. Mercury found him and drawing him away with coaxing hand said ‘Whoever you are, friend, if anyone asks if you have seen any of these cattle, say no, and so that the favour is not un-rewarded, you can take a shining heifer for your prize!’ and he handed it over.

The fellow accepted it and replied ‘Go on, you are safe. That stone would betray you quicker than I’ and he even pointed out a stone. Jupiter’s son pretended to go, but soon returned in another form and voice, saying ‘Countryman, if you have seen any cattle going this way, help me, and don’t be silent, they were stolen! I’ll give you a reward of a bull and its heifer.’ The old man, hearing the prize doubled said ‘They were at the foot of the mountain, and at the foot of the mountain is where they are.’ Atlantiades laughed. ‘Would you betray me to myself, you rascal? Betray me to myself?’ And he turned that deceitful body to solid flint, that even now is called ‘touchstone’, the ‘informer’, and unjustly the old disgrace clings to the stone.

Bk II:708-736 Mercury sees Herse

The god with the caduceus lifted upwards on his paired wings and as he flew looked down on the Munychian fields, the land that Minerva loves, and on the groves of the cultured Lyceum. That day happened to be a festival of Pallas, when, by tradition, innocent girls carried the sacred mysteries to her temple, in flower-wreathed baskets, on their heads. The winged god saw them returning and flew towards them, not directly but in a curving flight, as a swift kite, spying out the sacrificial entrails, wheels above, still fearful of the priests crowding round the victim, but afraid to fly further off, circling eagerly on tilted wings over its hoped-for prey. So agile Mercury slanted in flight over the Athenian hill, spiraling on the same winds. As Lucifer shines more brightly than the other stars, and golden Phoebe outshines Lucifer, so Herse was pre-eminent among the virgin girls, the glory of that procession of her comrades. Jupiter’s son was astonished at her beauty, and, even though he hung in the air, he was inflamed. Just as when a lead shot is flung from a Balearic sling it flies on and becomes red hot, discovering heat in the clouds it did not have before. He altered course, leaving the sky, and heading towards earth, without disguising himself, he was so confident of his own looks. Nevertheless, even though it is so, he takes care to enhance them. He smoothes his hair, and arranges his robe to hang neatly so that the golden hem will show, and has his polished wand, that induces or drives away sleep, in his right hand, and his winged sandals gleaming on his trim feet.

Bk II:737-751 Mercury elicits the help of Aglauros

There were three rooms deep inside the house, decorated with tortoiseshell and ivory. Pandrosus had the right hand room, Aglauros the left, and Herse the room between. She of the left hand room first saw the god’s approach and dared to ask his name and the reason for his visit. The grandson of Atlas and Pleione replied ‘I am the one who carries my father’s messages through the air. My father is Jupiter himself. I won’t hide the reason. Only be loyal to your sister and consent to be called my child’s aunt. Herse is the reason I am here. I beg you to help a lover.’ Aglauros looked at him with the same rapacious eyes with which she had lately looked into golden Minerva’s hidden secret, and she demanded a heavy weight of gold for her services. Meanwhile she compelled him to leave the house.

Bk II:752-786 Minerva calls on Envy

Now the warrior goddess turned angry eyes on her, and in her emotion drew breath from deep inside so that both her strong breast and the aegis that covered her breast shook with it. She remembered that this girl had revealed her secret with profane hands, when, breaking her command, she had seen Erichthonius, son of Vulcan, the Lemnian, the child born without a mother. Now the girl would be dear to the god, and to her own sister, and rich with the gold she acquired, demanded by her greed. Straightaway the goddess made for Envy’s house that is filthy with dark decay. Her cave was hidden deep among valleys, sunless and inaccessible to the winds, a melancholy place and filled with a numbing cold. Fire is always absent, and fog always fills it.

When the feared war goddess came there, she stood outside the cave, since she had no right to enter the place, and struck the doors with the butt of her spear. With the blow they flew open. Envy could be seen, eating vipers’ meat that fed her venom, and at the sight the goddess averted her eyes. But the other got up slowly from the ground, leaving the half-eaten snake flesh, and came forward with sluggish steps. When she saw the goddess dressed in her armour and her beauty, she moaned and frowned as she sighed. Pallor spreads over her face, and all her body shrivels.

Her sight is skewed, her teeth are livid with decay, her breast is green with bile, and her tongue is suffused with venom. She only smiles at the sight of suffering. She never sleeps, excited by watchful cares. She finds men’s successes disagreeable, and pines away at the sight. She gnaws and being gnawed is also her own punishment. Though she hated her so, nevertheless Tritonia spoke briefly to her. ‘Poison one of Cecrops’s daughters with your venom. That is the task. Aglauros is the one.’ Without more words she fled and with a thrust of her spear sprang from the earth.

Bk II:787-811 Envy poisons Aglauros’s heart

Envy, squinting at her as she flees, gives out low mutterings, sorry to think of Minerva’s coming success. She takes her staff bound with strands of briar, and sets out, shrouded in gloomy clouds. Wherever she passes she tramples the flower-filled fields, withers the grass, blasts the highest treetops and poisons homes, cities and peoples with her breath. At last she sees Athens, Tritonia’s city, flourishing with arts and riches and leisured peace. She can hardly hold back her tears because she sees nothing tearful. But after entering the chamber of Cecrops’s daughter, she carried out her command and touched her breast with a hand tinted with darkness and filled her heart with sharp thorns. Then she breathed poisonous, destructive breath into her and spread black venom through her bones and the inside of her lungs. And so that the cause for pain might never be far away she placed Aglauros’s sister before her eyes, in imagination, her sister’s fortunate marriage, and the beauty of the god, magnifying it all.

Cecrops’s daughter, tormented by this, is eaten by secret agony, and troubled by night and troubled by light, she moans and wastes away in slow, wretched decay, like ice eroded by the fitful sun. She is consumed by envy of Herses’ happiness; just as when a fire is lit under a pile of weeds which give no flames and burn with a slow heat.

Bk II:812-832 Aglauros is turned to stone

Often she longed to die so that she need not look on, often to tell her stern father of it as a crime. Finally she sat down at her sister’s threshold to oppose the god’s entrance when he came. When he threw compliments, prayers and gentlest words at her, she said ‘Stop now, since I won’t go from here until I have driven you away.’ ‘We’ll hold to that contract’ Cyllenius quickly replied, and he opened the door with a touch of his heavenly wand. At this the girl tried to rise, but found her limbs, bent from sitting, unable to move from dull heaviness. When she tried to lift her body, her knees were rigid, cold sank through her to her fingernails, and her arteries grew pale with loss of blood.

As an untreatable cancer slowly spreads more widely bringing disease to still undamaged parts so a lethal chill gradually filled her breast sealing the vital paths and airways. She no longer tried to speak, and if she had tried, her voice had no means of exit. Already stone had gripped her neck, her features hardened, and she sat there, a bloodless statue. Nor was she white stone: her mind had stained it.

Bk II:833-875 Jupiter’s abduction of Europa

When Mercury had inflicted this punishment on the girl for her impious words and thoughts, he left Pallas’s land behind and flew to the heavens on outstretched wings. There his father calls him aside, and without revealing love as the reason, says ‘Son, faithful worker of my commands, go, quickly in your usual way, fly down to where, in an eastern land, they observe your mother’s star, among the Pleiades, (the inhabitants give it the name of Sidon). There drive the herd of royal cattle, that you will see some distance off, grazing the mountain grass, towards the sea shore!’ He spoke, and immediately, as he commanded, the cattle, driven from the mountain, headed for the shore, where the great king’s daughter, Europa, used to play together with the Tyrian virgins. Royalty and love do not sit well together, nor stay long in the same house. So the father and ruler of the gods, who is armed with the three-forked lightning in his right hand, whose nod shakes the world, setting aside his royal sceptre, took on the shape of a bull, lowed among the other cattle, and, beautiful to look at, wandered in the tender grass.

In colour he was white as the snow that rough feet have not trampled and the rain-filled south wind has not melted. The muscles rounded out his neck, the dewlaps hung down in front, the horns were twisted, but one might argue they were made by hand, purer and brighter than pearl. His forehead was not fearful, his eyes were not formidable, and his expression was peaceful. Agenor’s daughter marvelled at how beautiful he was and how unthreatening. But though he seemed so gentle she was afraid at first to touch him. Soon she drew close and held flowers out to his glistening mouth. The lover was joyful and while he waited for his hoped-for pleasure he kissed her hands. He could scarcely separate then from now. At one moment he frolics and runs riot in the grass, at another he lies down, white as snow on the yellow sands. When her fear has gradually lessened he offers his chest now for virgin hands to pat and now his horns to twine with fresh wreaths of flowers. The royal virgin even dares to sit on the bull’s back, not realising whom she presses on, while the god, first from dry land and then from the shoreline, gradually slips his deceitful hooves into the waves. Then he goes further out and carries his prize over the mid-surface of the sea. She is terrified and looks back at the abandoned shore she has been stolen from and her right hand grips a horn, the other his back, her clothes fluttering, winding, behind her in the breeze.