A Honeycomb for Aphrodite

Reflections on Ovid’s Metamorphoses

Part III

A. S. Kline © Copyright 2003 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- XI Magic and Prophecy

- XII Fate and Error

- XIII Lust, Love, Sexuality and Betrayal

- XIV Loyalty and Marriage

- XV Pride and Vanity

XI Magic and Prophecy

Destiny is a weight on life and the spirit. Necessity weighs us down. The slow churning of epic and tragedy can feel like death to the soul, rather than catharsis. While fantasy and the story can free us, the working out of a foredoomed reality could only be destructive of the psyche. Who has not felt the weariness of a life too clearly seen? Who has not escaped into the world of art or fresh personal relationship in order to destroy their sense of the inevitable? There are even texts that are too painful to read again, stories that are too inexorable to endure. Nowhere is the contrast between the web of destiny and the desire to alter destiny more apparent than in the contrast between the sorceresses of myth and the seers, the witches and the prophetesses. That they are usually both female suggests that woman embodies both aspects of life, as on the one hand the inevitable chain of procreation, the constant cycle of birth, life, death and new birth, the cycle of the moon, and the mother, and on the other the magical power of erotic love, and the intense desire to possess the loved freely through whatever means are available. Woman is a daughter of a daughter back to the beginning, a prophetic cave within a cave, enfolding wombs of myth out of which spring heroes and gods. Man is a product of her body. She is also the unpredictable transformation of the erotic: that which attracts man, entices and delays him, and from which he may seek to free himself, and may succeed, though not without cost.

As we might anticipate, Ovid expends far more words on the witches than on the seers. His prophetesses appear in order to add colour to his stories, rather than to initiate major events. The prophetic episodes are brief. The Sibyl confirms Aeneas’ fate (Book XIV:101) but we hear none of her ravings from the cave that Virgil conjures for us. Ocyrhoë warns Aesculapius and tells of his fate and that of her own father Chiron (Book II:633) only to be stopped by the Fates from further prophecy. Ovid does not give us the chilling effects such a prophecy might have had on Chiron. Tiresias, we hear, receives prophetic powers (Book III:316) and warns Narcissus’ mother Liriope of her son’s potential for self-intoxication, while Manto, Tiresias’ daughter calls the women of Thebes to prayer (Book VI:146). Themis, possibly an ancient moon-goddess of Thebes to whom the sphinx was sacred (Book VII:759), prophesies for Deucalion, to guide the rebirth of the earth (Book I:313), and overrules Juno to give a condensed version of the tales surrounding the War of the Seven against Thebes (Book IX:394) and to trigger Jupiter’s comments on the way fate binds the gods. She too had prophesied the theft of Atlas’ golden apples from the Garden of the Hesperides (Book IV:604). Themis represents that ancient world of oracular destiny that drives the epic and the tragic. But oracle and prophecy though touched on lightly in the Metamorphoses do not stir Ovid’s interest deeply. Prophetic words lead into heaviness and the closing of iron portals. Ovid is in favour of light, and the opening of the door into the garden. The Raven proclaims ‘I spurn empty prophecies’ though to be sure it meets the predictable fate of the informer, in a tale that has subtle echoes of Ovid’s own fate (Book II:531).

The witches, the sorceresses are more interesting to him. Here is woman with the power to create magical and erotic change, to enhance and defy fate, even if only temporarily. So Circe, and Medea, are given extended magical roles, while Mestra (Book VIII:843) and Thetis (Book:XI:221, though strictly a goddess) appear as erotic shape-shifters, gifted such powers by volatile Neptune.

Medea (Book VII:1), a face of the triple moon-goddess (Diana: Luna: Hecate) is infatuated by Jason, as, like Circe, she experiences desire for a mortal man. Her herbs and magic, inspired by Hecate, protect her lover from the fiery bulls, create conflict among his enemies, and send the dragon to sleep. She has the power to extend Aeson’s life, and does so, to attack Jason’s enemy Pelias and does so, though here she overreaches herself and has to flee. But still she is in the end forsaken by Jason, her erotic nature thwarted, and she commits crime in Corinth (where she destroys his new bride with fire) and Athens, eventually vanishing, escaping death ‘in a dark mist, raised by her incantations.’ The power of the erotic therefore works for good or for evil, depending on circumstances, essentially geared to the object of love as long as that object is mutually committed to her as the lover. Medea is portrayed as elusive, in contact with occult powers, devious (her name may mean ‘cunning’) and passionate.

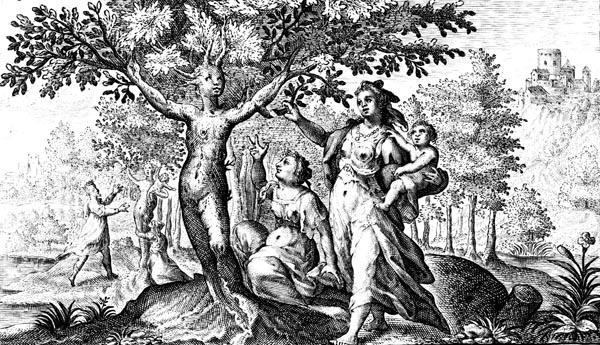

Circe, daughter of the fiery sun (Book XIV:1) is first seen enamoured of Glaucus. She is erotically charged ‘no one has a nature more susceptible to such fires’, perhaps by Venus herself. Spurned by Glaucus she too punishes his preferred love, Scylla. Walking the waves, she then poisons Scylla’s bathing place with the juice of harmful roots. Later we find her capturing and enticing Ulysses, and transforming his crew to wild beasts. Again the use of magic is ambiguous, both erotically helpful to her, and yet harmful against those who are not her lovers. Ulysses eventually escaped her delaying tactics, but we see her again enamoured, this time of Picus of Laurentum, spurned by him, and revenging herself on him and his lover Canens with all her occult resources.

‘Picus and Circe’

Magic then can aid the erotic, but as we have seen it fails in the end to hold the lover, and the witch is frequently spurned or abandoned, finding satisfaction only in her powers of revenge. Magic is here a temporary overcoming of fate, a command that is usually doomed to fail, but, as Ovid portrays it, a bold attempt at erotic freedom, especially for woman in the face of male choice, and male dominance. While Thetis submits in the end to Peleus, having run through all her forms, Mestra is sold repeatedly to men, but is able to escape them.

XII Fate and Error

Circumstance and character are fate. While heroes as we have seen are caught in the toils of pre-determined destiny, ordinary mortals are more often the victims of chance events beyond their control, or are the perpetrators of unwitting error. Ovid is strongly focused on the drama of human beings caught in the net of misfortune, on their emotions and decisions, the stress and strain on their characters, and the pathos of their suffering. These are tragedies in the sense not of something inescapable, ineluctable and pre-ordained, but tragedies in the sense of the damaged life, of hurt that is undeserved, and of pathos that generates spontaneous empathy. These people are innocent, and yet they suffer, as Ovid declared himself innocent of the crime for which he was exiled, claiming that it was ‘an error’. He was in the wrong place at the wrong time, as so many characters are in the myths, punished for being who they are, or where they are, or for their attributes.

‘Apollo seduces Leucothoe’

So beauty is fate for all those mortal girls loved by the gods. Daphne (Book I:438) and Io (Book I:587), Syrinx (Book I:689) and Callisto (Book II:401), Europa (Book II:833) and Semele (Book III:273), Leucothoe (Book IV:214) and Arethusa (Book V:572). They are transformed, or enter into the divine, or give birth to men and gods. And beauty can be a fate for mortal boys too, as it is for Ganymede and Hyacinthus (Book X:143). Beauty is something beyond. It is a mantle that falls over the mortal body, shining, characterless, but unique and fatal. It is the power of appearance, the attractive force of that magnet the human form is for us. It may hide cruelty and coldness, or warmth and innocence: it may be a hollow statue or a living inspiration, a decoration or a symbol. It may be a vanishing moment that shows us the heart-aching transience of what we love, or a consummation pregnant with destiny. The gods, those human-like forces enter the early world, and as a fire or a shadow, or disguised as a creature, they penetrate reality. They destroy and they inseminate, and they wrench lives apart. And the girl or the boy is a victim of his or her own loveliness. ‘Destroy this beauty that pleases too well!’ cries Daphne (Book I:525). Ovid’s attitude is empathy for the victim. His aim in the retelling is to evoke pity and the girls are portrayed as innocent, persecuted, a quarry in the hunt, escaping only in transformation, their beauty returning to the beauty of nature, or in death. Failure to escape means becoming a pregnant vehicle of the future: giving birth to a hero or a god.

‘Dryope picking the blossom’

Fate may equally be to be caught up in the affairs of the gods, to be condemned to speak or act, and to be punished as Tiresias is for speaking the truth (Book III:316), or by being taken too literally as the Sibyl was, condemned to endless life but without youth (Book XIV:101). It may be fatal to trespass into the sacred realm, too. Actaeon does, seeing Diana naked, and is punished for his error (Book III:138), as is Dryope, straying beyond the accepted bounds (Book IX:324). Or to cross the paths of the wielder of magic as a rival in love, as Scylla and Canens are afflicted by the angry Circe (Book XIV:1, Book XIV:397), or Glauce (Book VII:350). The divine, the superhuman, is cruel, and innocence is no defence.

‘Pyramus and Thisbe’

Fate may descend on the innocent mysteriously, too, through sheer mischance, through that malignancy that sometimes seems to inhere in events or in nature. So Eurydice treads on a snake (Book X:1). So Pyramus and Thisbe are thwarted, in that sweet story (Book IV:55) which Shakespeare mutilated in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and redeemed himself by transmuting into Romeo and Juliet. So Deianira unwittingly sends the shirt of Nessus to Hercules (Book IX:89). And so the storm descends on Ceyx (Book XI:410), out of the blue.

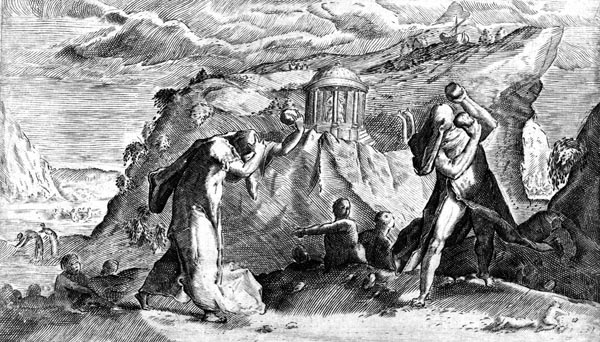

Or others may be our fate. It is enough to be born in the wrong place, to be a person caught up in human affairs, in the destinies of the great. So Ovid evokes pathos for Ino, innocent victim of Juno’s enmity against the House of Cadmus (Book IV:416), and Andromeda, punished for her mother’s failings (Book IV:663), for Hecuba, blameless queen of fallen Troy, and her courageous daughter Polyxena, doomed to be a sacrifice to the ghost of Achilles (Book XIII:429) and for Cassandra, raped in Troy, and murdered later alongside Agamemnon (Book XIII:399).

‘Ulysses drags Hecuba from the graves of her sons’

Worst of all is to be the innocent victim of another’s failing: another’s sin: another’s crime. To be a victim, is to be a sacrifice, to a god, to a shade, to the fragility of human life. The Greek light falls with the indifferent power of the sun, benign or merciless, over human affairs, and we are caught in the flow. Guiltless we are caught up in the fate of the guilty. Phaethon’s sisters will be turned to poplars in their grief (Book II:31): Niobe’s children will die through her pride (Book VI:146): innocent Philomela will be the victim of Tereus’ lust, and so in a sense will the child, Itys (Book VI:401): while Hesperie will be lost through Aesacus’ pursuit of her (Book XI:749).

‘Aesacus pursues Hesperia’

Ovid’s emotions are excited by innocence, by the pathos of the undeserved fate more than by that of the guilty. It is a core dimension of his feminine, secular, irreligious set of values. The incident of Polyxena hints at his attitude to sacrifice ‘No god will be appeased by such a rite as this!’ she cries. He depicts the questionable behaviour of the gods as if it were merely an exercise in aesthetics, and the movement of forces, the faces of power: he is sceptical as to their morality. After all, he may imply, anyone, regardless of morality, a Hercules, or a Caesar, for example, can become a god. Only with his treatment of Isis (Book IX:666), and perhaps Bacchus (Book IV:1, Book XI:85), is there the feeling of a mystery, a truly divine side to experience. Only there is there a feeling of invocation. But, I would argue, what Ovid is in fact invoking is the power of pity, what he finds enchanting is Isis, champion of the abused woman, and the unborn child, and Dionysus who rewards and forgives his followers. Rome was ready for a god of pity, a god of the innocent sacrifice, but here all is predominantly human and secular: and mortal emotion, mortal sadness is greater than divine power.

I would claim Ovid as a humanist, and a transmitter of human values from out of the heart of the myths. Nowhere is that more evident than in his attitude to women. He sympathised with the fate of women, as the Heroides revealed, women constrained in their roles, victims and subjects, punished merely for being there, and punished too for trying to be other than their lot dictated. He has a quiet admiration for Medea and Circe, for Polyxena (‘take the hands of man from virgin flesh!’ Book XIII:429), and Daphne( ‘free from men, and unable to endure them’ Book I:473). His heroes are often faintly ridiculous, creatures of force and bombast, his true heroes, his ‘heroides’, are women, mostly modest, reticent, brave, victimised, sometimes courageous, passionate, forceful. And Ovid avoids the more deliberately criminal women of the myths: there is no picture of adulterous and murderous Clytemnestra here, or perjuring obsessive Phaedra, only echoes of their activities. His women of terror are the Maenads, or Procne: maddened Furies, the agents of conscience and retribution, enacting vengeance for the violation of the sacred.

‘The Furies visit Tereus and Procne on their wedding night’

XIII Lust, Love, Sexuality and Betrayal

Venus-Aphrodite gave birth to the god of love, Cupid, or Eros as the Greeks knew him. His father was Mars, the war-god who committed adultery with Venus in her husband Vulcan’s bed, and who was caught with her in that smith’s bronze net (Book IV:167). Hence derives the aggression of lust, and the wars of love. Or in another version Hermes-Mercury, a phallic god, was the father, and love was also filled with that mental agility of wooers and wooed. Or the goddess committed incest with her father Jupiter-Zeus, and passion inherits that excess and disdain for boundaries. Cupid with his bow and arrows is Venus’ wayward child, causing even the gods to be blinded by passion, just as he is depicted blind: making Apollo desire Daphne (Book I:438), Dis be filled with a passion for Proserpine (Book V:332), and his own mother Venus fall in love with Adonis (Book X:503).

‘Mercury and Herse’

Venus-Aphrodite is the goddess of the whole spectrum of love, from lust and sexual obsession, through desire and mutual attraction, to long and faithful affection, and even a loving mourning for what is lost. She attends weddings, and she hovers over adulterers. She binds the loyal, and she encourages to betrayal. Myrtle is her plant, and Aphrodite’s ‘berry’ is the clitoris, as well as the fruit of that tree. The Metamorphoses is a work implicitly dedicated to her, as goddess of the Roman race, but also as goddess of that love, that admiration for the feminine, that is the core of Ovid’s writing. The inscription on the statue of Aphrodite, sculpted by Alkamenes, standing near her shrine in the Gardens at Athens, proclaimed that: ‘Heavenly Aphrodite is the oldest of the Fates.’ (Pausanias I.19.2)

‘Tereus cuts out Philomela’s tongue’

The Metamorphoses begins almost with that early world where the lust of the older gods sweeps down like the shadow of a bird across the earth, and where the azure sky flashes lightning to possess a mortal girl, or the god takes the emblematic form of a horse or a bull, a swan or an eagle. The animal kingdom is one with the human. Aphrodite, that Astarte of the East, is also the Lady of the Creatures, before Artemis-Diana is split away from her. And the gods are erotic possession, the flailing arms and twisting bodies of all those ensnared virgins who writhe beneath the god’s adopted form, pierced and taken by the primeval urge, like Io caught in the mist (Book I:587): like Callisto, betrayed by Jupiter (Book II:417) ‘as far as a woman could she fought him’: like Proserpine snatched by Dis, crying to her mother ‘with piteous mouth’: like Neptune raping Medusa, even in the temple of Minerva itself (Book IV:753). It is, as Sappho says ‘A whirl of wings from above, beating down through the heart of the air’, it is ‘the wind on the mountain pouring through the oak trees’, and what occurs creates ‘the demented heart’ and the mind of a woman who will ‘love against her will’ (Sappho LP: 1). That is one end of the spectrum. Gods who must satisfy themselves with mortal women, or one step down, and one move less permissible, women who like Medea and Circe lust after mortal men. What is acceptable for the gods is dangerous for mortal witches, and it may end in deceit and betrayal. A step further down again, and it is an urge, obsessive and fraught with risk that runs hand in hand with violence and crime. It is the lust of Tereus, the Thracian ‘savage’, for Philomela that rapes and cuts its way to the mute objectification of woman, in a denial of all she is (Book VI:486). It is the passion of Phaedra for Hippolytus, inspired by Eros who ‘heats my marrow with greedy fire’ (Ovid: Heroides IV), she who is ‘swept away, like the Maenads’, who declares ‘I have no shame’. Phaedra, who in the end commits a crime of perjury to condemn her lover to exile, and his father’s curse (Book XV:479). This is passion, obsessive and destructive, tearing apart human relations, filled with erotic charge. It is man and woman, dazed, inflamed, maddened, or in a conflicting phase rejected, stunned, and angered. It is sexual power in excess, loosed and frenzied. It is the monstrous Aphrodite, the ravening goddess, the equivalent of the Hindu Kali, that female incarnation of Siva to whom human sacrifice was made, or that Diana of the Chersonese whose altars were death to strangers, and ‘stained with murder’ (Ovid Tristia IV.IV:43). It lies behind the myth of Atalanta (Book X:560) who was truly ‘pitiless, but such was the power of her beauty a rash crowd of suitors came, despite the rules.’ The inconstant god descends, the inflamed goddess stretches out her hand, and in the flash of lightning, the click of the shutter, the single profile of the beloved is cast darkly on the white screen of time, the same profile, the one silhouette.

‘Atalanta and Hippomenes’

And Venus-Aphrodite is the goddess of the forbidden, the force that breaks human conventions. Incest is her dark doing. Byblis loves her brother Caunus, and, as she soliloquises, there is divine precedent in that ‘the gods have possessed their sisters’ (Book IX:439), while Myrrha sneaks into her father’s bed: after all, do not ‘the creatures mate indiscriminately’, and surely it is only ‘human concern that has made malign laws.’ (Book X:298).

But Venus is not merely lust, no mere sexuality. Though she is the prostitute and the goddess of prostitutes, she is the deeper movement of love also. She is committed passion that dies of love for its object: she is a tenderness that stirs the god to pity, and the goddess to heart-broken mourning. She is the betrayed and the betrayer but also the faithful and the entangled. She is the body’s remorseless stirring, but she is also the mind and spirit’s sweet embrace. So Echo wasted away with love for Narcissus (Book III:359) ‘the more she followed the closer she burned’: and Salmacis fused with Hermaphroditus (Book IV:346) ‘hanging there’, twined round his head and feet: and indeed beauty may be loved by the beast, Galatea by poor Polyphemus. ‘Oh, Gentle Venus’, says Ovid, ‘how powerful your rule is over us!’ (Book XIII:738).

And there is the pity of love, too. Apollo, betrayed by Coronis, repented of killing her and ‘groaned from the depths of his heart’ (Book II:612), and so Jupiter groans as he hears Semele’s request (Book III:273) and Venus herself suffers, and complains to the Fates, as she bends over the bloodless body of her Adonis (Book X:708).

Love flirts always with betrayal, eroticism may overpower the heart, the magnetic power of sexuality may defeat the mind. Jealousy may corrupt the lover: that yearning for a wrongful possession of the beloved, a reduction of person to object. The idea of adultery may pierce the loving soul. The adulterer may reject and scorn and abandon the once beloved. Envy or greed or garrulity may prompt the informer to betray the lovers. Theseus forsakes Ariadne (Book VIII:152), Jason abandons Medea (Book VII:350), Aglauros is touched by Envy, jealous of Mercury’s love, for her sister Herse, and is ‘eaten by secret agony’ (Book II:787). The Raven betrays Coronis to Apollo (Book II:596) and truth is his downfall. Scylla betrays her father and her city, Megara, for love of Minos (Book VIII:1), while Clytie condemns her rival Leucothoe, for the sake of the dazzling Sol (Book IV:214) and his daughter Circe condemns the other Scylla in her jealous desire for Glaucus (Book XIV:1).

‘The reconciliation of Cephalus and Procris’

One of Ovid’s saddest tales is that of Cephalus and Procris, a complex meditation on suspicion, jealousy and the fatal power of mistrust. Cephalus, himself resisting the passion of Aurora, the Dawn, for love of his Procris, indulges in a fatal test of his wife’s loyalty, almost tempting her to adultery. She flees, and later the situation is rescued, but then Procris is led by an informant to suspect Cephalus, erroneously. She spies on him, and he through a tragic accident, unintentionally kills her (Book VII:661). The story gave Shakespeare, directly or indirectly, at least two of his plots.

Venus then spans the gamut of emotions, and the whole range of actions within the sphere of love. From the violent, erotic acts of possession of the old gods, through the increasing tenderness and affection of the younger gods and goddesses: from the excessive passions of mortals, their incest, adultery and jealousy, to the spontaneous and graceful consent of mutual ‘true’ love, and the enduring bonds of longstanding commitment, and enduring marriage. From aggression to care: from violence to empathy and compassion: from betrayal to unbreakable loyalty.

XIV Loyalty and Marriage

‘Fortunate bridegroom’, Sappho sings, ‘the marriage you prayed for has come about, and the bride you dreamed of is yours…Lovely bride, the sight of you is joy: your eyes are honey, and love flows over your gentle face…Aphrodite has honoured you above all the rest.’ (Sappho: LP 112) Ovid was three times married (one marriage was a difficult failure, his second wife died, the third outlived him as far as is known, see Tristia IV.X:41), and he gives great weight to marriage in the Metamorphoses. By doing so, he both offsets the effects of his earlier work in the Amores, and the Art of Love, and the memory of all those betrayed, forsaken and passionate women of the Heroides, and he extends the tradition of Homer’s Odyssey as he did in the very first of the Heroides. ‘…Nothing is greater or better than this’ says Odysseus as he speaks to Nausicaa (Odyssey Book VI:180) ‘than a man and woman keeping house together, sharing one mind and heart, a grief to their enemies and a joy to their friends..’. Odysseus is returning to his faithful wife Penelope, while Alcinous, Nausicaa’s father and King of the Phaeacians lay down in his chamber and ‘beside him that lady, his wife (Arete), brought him love and comfort.’ (Odyssey VII:345).

Ovid produces some of his best effects in the Metamorphoses with stories that contain the warmth, tenderness and enduring loyalty of married love. There is the voice with which Deucalion speaks to Pyrrha his ‘dear wife’ after they alone survive the Flood (Book I:348), there is the pathos of Cadmus and Harmonia’s end (Book IV:563) where both are transformed into serpents, ‘two snakes there, with intertwining coils’. There is the love, equally shared, of the Centaurs, Cyllarus and Hylonome, who sadly die together (Book XII:393). There is the marriage between Perseus and Andromeda, where we see the ‘happy evidence of joyful hearts’ (Book IV:753) a scene which is ancestor to Shakespeare’s resolution of many of his comedies in happy marriages.

‘Deucalion and Pyrrha create a new race of men’

And Ovid is moved enough to broaden out into extended stories when he finds real beauty in the situation. So, there is the beauty of the marriage of Baucis and Philemon, the touching nature of their wish, and the sweetness of their ending, transformed into trees (Book VIII:611): there is the pathos of the story of Ceyx and Alcyone, their expressions of married love, the disaster of that tempest, another source of Shakespearean effects, and the sadness of loss and grief at the death of a partner (Book XI:410), an echo of that of Procris: and there is Orpheus finding his Eurydice again in the fields of Elysium (Book XI:1). Each of these scenes benefit from Ovid’s real feeling for enduring love, and he pours some of his sweetest words into the idea of marriage.

And when the bonds are broken, as they are between Procne and Tereus, we see the power of revulsion, the terrible reaction of the wife and her sister to the depths of his betrayal (Book VI:401).

In the Metamorphoses Ovid proves himself the true ‘master of love’ in a manner that goes beyond the witty social commentary, and the dance of lovers, as he portrays it in the Art of Love, and the Cures for Love. I think here he justifies his statements, from exile, that his life was not his art, and that his work had never been designed to corrupt. Reading the Metamorphoses we obtain as strong a view of the beauties of married love, and mutual human commitment, as Augustus himself, in later life, might have desired. And his portrait of the Emperor and his Livia, in the infidelities and bickering of Jupiter and Juno, is itself a witty commentary on yet another aspect of marriage, the frequently non-destructive sparring of partners, the little bouts of anger and spite indulged in by married lovers and friends, tolerated because of a depth of mutual understanding.

Tenderness and irony, realism woven with sensitivity and empathy, that is Ovid’s hallmark, and the sign of his subtlety and the greatness of his art. How badly he has been understood, and how inadequately he has been praised, a master of words so skilful, that it seems easy to do what he does, simple to imitate, whose grace of style can seem, to the careless, a superficial smoothness, and whose beauties can seem, to the unsympathetic, a mere conventional music. Yet it was he who alerted us, in a cultivated Roman way, to that grace and beauty, and whose own literary legacy has made the music seem ‘conventional’, by itself creating the convention that the Renaissance seized on.

It is not always the clashing of weapons in epic, or the extremes of human emotion in tragedy, that express the depths of human experience. They can come to seem like effects for the sake of effect, horror for the sake of horror, and occasionally like attacks of self-indulgent histrionics. Ovid is all for balance, all for the middle way, and the avoidance of that excess. Though he sometimes exploits the effects too, his heart is not in it. He can stray near to bathos and melodrama with his attempts at violence and horror. Ovid speaks more effectively when he speaks about the mythical in terms of the ordinary life, and of the depths of love and pathos as they strike common mortals. Does that make him a poet of the bourgeoisie, the tame middle-classes, of the easily satisfied reader looking for entertainment rather than profundity? I think not. The more I read him, the greater I think the miracle he performed. And all good creative literature is in a sense entertainment. That is its first task. Ovid’s gleaming visual surfaces are not shallows: they are reaches of crystal clear water, their depths seeming near enough to touch.

XV Pride and Vanity

When the gods step down among human beings, and take on mortal form they run a risk: that of going unrecognised, or worse still of being treated as mere mortals indeed. The Greek gods are jealous gods, jealous of their own attributes and powers, and their supremacy in the areas under their control. Though no god can reverse the actions of another, though the gods of the sky and earth have no powers on the sea or in the underworld, within their own sphere they countenance no opposition. For a mortal to take too much pride in his or her own capabilities, or to feel too much security, to consider themselves immune from the vicissitudes of fate, is hubris. And that bloated human pride in success and wealth, or that vanity derived from great beauty or great skill, is a form of excess. Ovid is a follower of the middle way, and the stories of the Metamorphoses are filled with examples of hubris and counter-examples of a proper humility, a proper recognition of the fragility of human life, and the limited nature of our powers.

Phaethon begins it, asking a fatal request of his father Sol, the sun god. And a god’s oath once sworn on the Styx, that river of the underworld that is the gods’ conscience, cannot be retracted. Sol grants his son command of the sun chariot, and Phaethon unable to manage the reins, unable to hold the god’s fiery horses, soars high towards the stars, then plunges down, far from the middle course towards the earth, scorching it in passing. Phaethon’s inflated idea of himself and his abilities, derived from his divine parentage, has led him to hubris, to excess. Jupiter restores order by sending the fire of lightning to end the fiery flight, and Phaethon plunges deep into the river Eridanus. Note Ovid’s touch of pity even here as the river god ‘takes him from the air, and bathes his smoke-blackened face’, while his sisters are turned to poplar trees, weeping tears of amber. Ovid’s vivid visual gifts are in evidence throughout (Book II:1).

Vain Narcissus continues it, spurning poor Echo to fall in love with his own face in the fountain, that ‘fleeting image’. And Ovid fittingly gives the mind intoxicated with itself a soliloquy in which to indulge the sentiment. Narcissus melts away at last, leaving behind the narcissus flower gazing at itself in the clear waters (Book III:339).

Then the nine sisters, the Pierides, challenge the supremacy of the Muses in singing, and for their part sing their mockery of the gods, how they fled to Egypt and took on animal forms (Book V:294), while Calliope’s reply is instead an assertion of divine mystery, the myth of Demeter and Proserpine, the Mother and the Maid. Beautiful and profound: so that the Pierides in their laughter and ridicule are transformed to chattering magpies. Those who, in their vanity, mock at what they do not comprehend, must expect to be punished by fate (Book V:642). Impiety and pride are inextricably interwoven. To challenge the gods is also to scorn the gods: to believe oneself greater than them, is also to deny them their due respect.

Ovid is warming to the theme. Book VI recounts three famous stories of pride punished, Arachne, challenging the goddess Minerva to a weaving contest, only to end as a spider forever web-bound (Book VI:1), Niobe, daughter of a Pleiad (and its seven main stars, so she is associated with the number seven), child of Tantalus, boasting of her status, her seven sons and seven daughters, her riches, calling herself ‘greater than any whom Fortune can harm’, challenging Latona, whose own two children are more powerful than an army of mortals. It is Apollo and Diana who kill her offspring with their cruel arrows, and Niobe herself is transformed to weeping stone. (Book VI:146).

So it goes on, this human excess, and its nemesis, its punishment, since all skill and beauty, all surplus, is a gift of fate, of life, of nature, of the graces, of the powers outside us, and hidden within us, and so must be appreciated, understood, cherished, and respected, not as something of ours, but something given, something shared. And do we not understand this, even in a secular age, that there is a tactfulness of the heart, and a proper humility of the spirit? That the greatest crime of those endowed by fate, is to fail to give back, to fail to give thanks, to fail to open full hands to a world of poverty and deprivation, and then multiply the good by sharing it, by giving, silently, invisibly and tenderly, in that gesture of the third Grace (the trio of Graces are Aglaia, Euphrosyne, and Thalia: giving, receiving and thanking), that gesture of the mother with her child, and the lover with the beloved, delighting in the presence that comes, almost miraculously it seems, from the sources of being, and in our own ability to give to that presence.

‘Apollo flays Marsyas’

But still Marsyas, the satyr, will compete with Apollo, only to be loosed from the sheath of his skin, mourned by the nymphs and the woodland gods, and the fauns and his brother satyrs, and end as all life is accustomed to end in a river of tears (Book VI:382). Still, Icarus will fly too near the sun in his sudden ecstasy of flight (Book VIII:183), and Chione, mother of Autolycus, will criticise Diana’s beauty and receive an arrow in exchange (Book XI:266), and Ancaeus ‘swollen with pride’ will challenge Diana’s power and gain his death wound in the fields of Calydon (Book VIII:376). Phoebus-Apollo, Diana-Artemis, Minerva-Athene, the remote gods, the detached ones, art, nature, skill, the divinities of what is given to us, our natural and innate capabilities, our hidden powers: these are not good divinities to mock or to oppose. They are the givers, we are the takers, and so a proper respect, a proper distance, and a proper humility are needed in addressing what we do not yet understand, the faculties of mind: the structures of the brain: the processes of our inner selves.