A Honeycomb for Aphrodite

Reflections on Ovid’s Metamorphoses

Part I

A. S. Kline © Copyright 2003 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- I. The Golden Honeycomb

- II The Dual Paths of Art

- III The Structure of the Metamorphoses

- IV Ovid’s Interest in Myth

- V Nature,The Matrix

I. The Golden Honeycomb

There is a myth that is at the heart of the myths. It is a myth of Crete, but annexed to a myth of Athens, and it contains a metaphor, a set of metaphors, about art. Beautiful in itself, and ultimately mysterious in the power of its associations it refers beyond itself to the whole artistic, perhaps also the whole scientific project. The central myth is about Theseus, and Ariadne and the Labyrinth at Cnossos, but parallel to it and interwoven with it is the myth of Daedalus, the maker.

Daedalus, sculptor and inventor, craftsman, and artist, is said to have been an Athenian, a son of the royal house of Athens, so that, from the first, he represents Pallas Athene’s values, Mind and Intellect, the gifts of the virgin goddess, she who grants clarity to the eye and resilience to the heart, who gives deftness of hand, and inspires simplicity of line, she who fuels the Athenian desire for form, for inner dialogue, for transcendence. Daedalus’s statues are said to have been almost living. He is the creator of the sculptural third dimension, the wide-open eye, the extended arms and stride. A myth is made, that Ovid partially retells (Book VIII:236) explaining how Daedalus in jealousy flung the boy, Talos, his apprentice, and son of his sister Perdix (or Polycaste), from the heights of the Athenian citadel, sacred to Pallas Athene herself. Talos had invented many things including the saw, and compasses. He is transformed into a partridge, a sacred bird. This story gives a pretext for Daedalus’s banishment from Athens . Driven away from mainland Greece he takes his art to Crete, to the court of King Minos, son of Jupiter the divine, and Europa, that girl whom the god, disguised as a bull, stole from Phoenicia, from Asia . Minos is the lawgiver, and ruler of a hundred cities, lord of Crete the beautiful, cradle of Greek civilisation.

‘Minerva transforms Talos into a partridge’

The story reverses history. Athens gives arts to Crete, whereas Minoan Crete, joyful and full of the graces of life, gave its arts, in truth, to mainland Greece . It gave delight in the word and the dance, in ritual and decoration, it gave lightness of touch, and above all its understanding of feminine values, of the Great Goddess, that lady of the wild creatures, of honey and the hive. She is the Phoenician Astarte, and the laughter-loving Aphrodite her Greek equivalent, she is Cybele and Artemis, she is the triple-goddess at the core of the oldest myths. She is shadowy and magical, glimpsed in faience figurines, in the forms of the bull-leapers, and in the ivory knots, and the golden bees, of Minoan art. Perhaps it was her figure, now lost, that once crowned the lion gate at Mycenae, supported by those wild beasts on either side. Perhaps it was her conical carved stone, taken toGreece, that became the navel stone of oracular Delphi, the centre of the earth. Mainland Greece absorbed Crete . Crete, in turn, gave a swift-flowing delight, and passed on that flow to Greek civilisation, a richly female set of values, contrasting with the masculine dynamics of the sky-gods of Olympus. The Goddess became Aphrodite, and Artemis, Hera, and Athene, or in Ovid’s terms Venus and Diana, Juno and Minerva, the goddess as virgin and as wife, as magic power and fatal presence, the goddess in her many manifestations, wearing her many masks, showing her many faces. That Cretan legacy appeals to Ovid. It is his natural mind-set. It is where his heart lies.

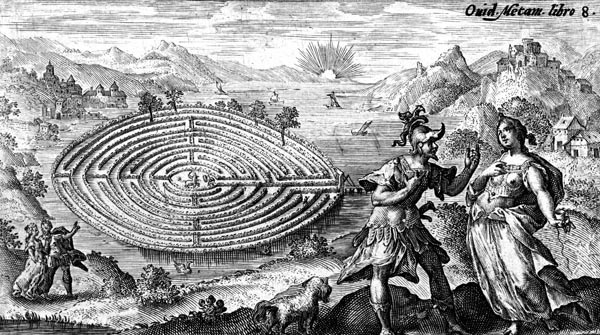

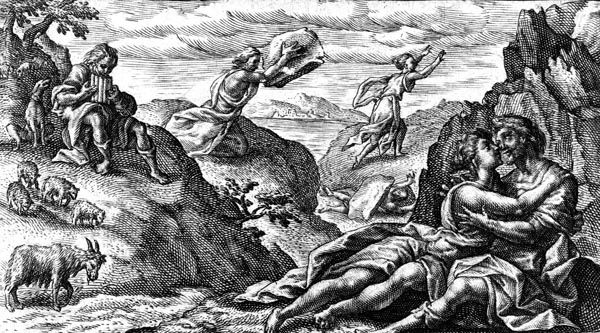

‘Theseus and Ariadne’

In Crete, the first of Daedalus’ creations was the wicker-frame in which Pasiphae, Minos’ Queen, driven by passion, disguised as a heifer, mated with Neptune-Poseidon’s white bull from the sea. Crete of the bull-leaper frescoes, and the double-headed moon-bladed axes, gives also this mysterious story of unnatural love and procreation, the dream of passion creating monsters, creating the Minotaur half-human, half-bull, a metaphor for Minos’ power. Daedalus then made a Labyrinth (Book VIII:152) beneath the palace of Cnossos, in which Pasiphae’s child, the Minotaur, Asterion, might be imprisoned. The self of humanity, part creature, part human, is locked away inside the maze of inner being. An image of that buried continuity with the animal world, which is also a buried challenge to our civilised existence. Outside, in the free air, Daedalus also created a dancing floor for Ariadne, the creature’s half-sister, daughter of Pasiphae and Minos, sister of Phaedra. It was a space where the Cretan delight of ritual movement might be exhibited, in that society where women, as Plutarch says, in his Life of Theseus, took part freely in the games, as at Sparta. Ariadne is one more incarnation of the Great Goddess, her dance a bird-dance perhaps, of the ritualistic mating partridges of Phoenicia, or a maze dance, echoing the labyrinth beneath her feet, or a dance of stars and constellations, or a dance of the bees in front of the hive, signalling the path to their flowered pastures.

Athens arrives, male assertive power, in the form of Theseus, to suborn the goddess and end the tributes of mainland Greece to Minos and Crete. Ariadne betrays her country and her father, but, acting as the goddess, gives Theseus the means to enter the labyrinth of self, destroy the creature within, and return, so destroying the emblematic power of Minos. Theseus in turn then abandons and betrays her (BookVIII:169), Athenian power and indifference scorns the goddess that gave it values. Ariadne is rescued by Bacchus-Dionysus. They are related, since he is a grandson of Cadmus through Semele, while she is a granddaughter of Cadmus’s sister, Europa, through Pasiphae. He sets her diadem among the dancing stars, as the Northern Crown, the Corona Borealis.

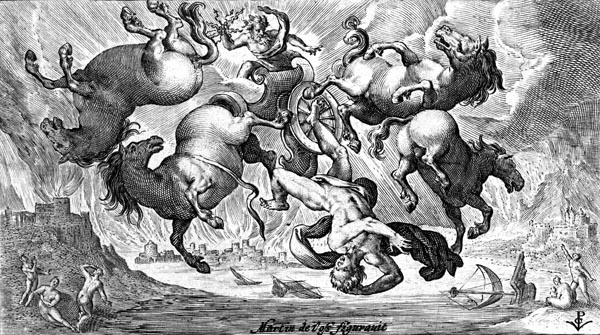

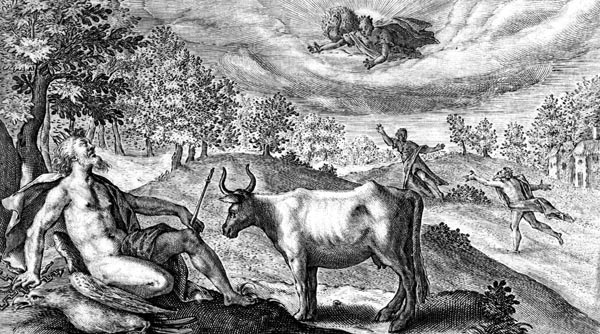

Daedalus meanwhile, persecuted by Minos, has made wax wings for himself and Icarus, his son by Naucrate, one of Minos’ slaves (Book VIII:183). Warning his son to keep to the middle way, far from the extremes of the heavens and the earth, they take to the sky, flying eastward. But Icarus in pride, curiosity, and the first intoxication of this new artistry, flies too high, too near the sun, the wax melts, and he plunges down into the waters that are named after him, the Icarian Sea.

‘The fall of Icarus’

Daedalus buried him on the island of Icaria, and then turned westward, touching down over Italy, at Cumae, near Circe’s Mount Circeo, a peninsula, once an island cut-off by marshes from the mainland, north of modern Naples. There, Daedalus dedicated the waxen wings to Apollo, the god of art and prophecy, and built a golden-roofed temple for the god, in which his prophetess the Sibyl might live. There, Aeneas will come to speak with her (Book XIV:101) and be guided on the paths of the dead, to the dim regions of the underworld, to pluck the golden bough, and meet with his dead father, Anchises (See also Virgil: Aeneid Book VI).

From Italy, Daedalus flew on, and reached Sicily, and the court of King Cocalus, at Camicus, where he built a fortress (perhaps the site of the ancient city of Acragas, by Agrigento), and solved the task, set him by the King, of threading a Triton shell, by luring an ant, with honey, through its windings. Finally Daedalus created a golden honeycomb for the goddess at Eryx. This shrine of Venus-Aphrodite, and her red doves (both her sacred birds and a name for her priestesses), in the northwest of Sicily, famous in the ancient world, is situated on a high and isolated hilltop on the coast, visible from land and sea for many miles. Diodorus Siculus, Diodorus the Sicilian, tells the story. Daedalus made for the Greek goddess, she an incarnation of the Cretan goddess of the creatures, of the sacred doves and bees, a golden image, a symbol of the hive of art, with its waxen cells, artificial and elaborate, made by the living industry of the bees, and filled with flower pollen, to create the honeyed liquids of the goddess of love, her dripping comb. Bees were of the Goddess, and the priests, the king-bees, were also guest-masters to Ephesian Artemis. (Pausanias Book VIII.13.1). And the bees are emblems of creative art, those bees that made their wax on Pindar’s lips as he slept just above the road on the way to Thespiai (Pausanias IX.23.1). The complex myth of Daedalus ends here, in fragmentary myths that take him ultimately to Sardinia, where we finally lose trace of him. He has become a component in the wider stories of Theseus the hero, and of Athens.

The myth cluster is ancient and powerful. Daedalus the maker is inextricably bound up with the story of Minos and Pasiphae, Ariadne and Theseus, which in turn links Crete through Europa to Phoenicia, and the Theban story of Cadmus. Asia, Crete, Athens, Italy and Sicily are tied together. Though Minoan Cretan civilisation antedates the Athenian, the Cretan myths have been incorporated into the mainland Greek myths, and juxtaposed with the heroic tales of Theseus, a later Athenian King. So Daedalus finds his place in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, not at the beginning of Ovid’s historical sequence, but at the apex, Book VIII, at the centre of the whole work. There is the artificer: the artist: the maker, at the very core. The myth complex associates him with the Goddess and her worship, she appearing as Pasiphae, Ariadne and Aphrodite, the multiple masks. It associates him with the arts, and with their symbol the hive, and the honey of the hive, product of a living creative act, of discipline and ritual, of intelligence and industry. It associates him also with the dance of mind, with the dancing floor of the heavens and the earth, with the starry goddess and the sacred circuit of her crown, she the half-sister of the bi-formed Minotaur, and a consort of Dionysus, the wild and untamed. And it associates him with the prophetic oracular powers of Apollo’s priestess, at Cumae, so that Apollo, the civiliser, and Dionysus the inspirer are both present, the two poles of art, frenzy and form. Within the one myth, then, are many metaphors, but above all there is the division between Crete and Athens, between Dionysus and Apollo, between feminine and masculine values, between on the one hand the dancing floor and the golden honeycomb, and on the other the labyrinth and the temple. Between the fluid and free, and the highly-wrought and constrained. The free-flowing honeyed dance and the buzzing golden hive are set against the introspective and tragic journey of self, against the uplifted pillar of worship, and the created house of binding destiny for mind and the gods. ‘They say the oldest shrine of Apollo was built of laurel with branches brought from the groves of Tempe . This shrine must have been in the form of a hut. The Delphians say the second shrine was made by the bees, from bees’ wax and feathers.’ (Pausanias Book X.5.5).

II The Dual Paths of Art

Ovid is a transmitter of myths in the Metamorphoses, but not of all the Greek myths or all the modes of those myths. What fails to interest him is as vital as what does, and even his choice of main theme, the changes undergone by human beings and others, the metamorphoses of men and women into creatures and trees and flowers and natural forms, of gods occasionally into creatures, and heroes into gods, that choice of theme is consonant with his values and sympathies. I would suggest that Ovid is primarily a transmitter of values I would identify with the Great Goddess, with the feminine pole of experience, with the fluid and mortal and graceful and sacred, and that he largely steers away from the values embodied in Greek tragedy, and away from the Epic values of masculine force and power, of cunning and intellect. The Metamorphoses disappoints those who look to it for dark explorations in the labyrinth, for Aeschylus, or Sophocles or even Euripides. It equally disappoints those who look to it for the formal constructions and workings of destiny, religion and empire, for the epic values of the Iliad or Aeneid, or the towering structures later evident in the Divine Comedy. The closer links are to the Odyssey, and its meandering narrative, its story of the hero returning from Troy linking fascinating incidents, though Ovid himself is less interested in Odysseus, than in the wanderings among myth, less interested in masculine ingenuity and power, than in feminine beauty and that dance which lacks a fixed central character: the descendants of the thread of the Metamophoses are the journey of Chaucer’s pilgrims, the garden and the days of Boccacio’s tales, or Rabelais’s literary voyaging. Ovid is a Cervantes without a Don Quixote, a Goethe without a Faust.

Approach Ovid from the wrong angle and he appears slight, a mere tale-teller. Where are Homer’s Troy and Achaea, Virgil’s Roman Empire, Dante’s cities of Dis, Italy and God? Where is that grappling with human extremes of the Greek tragedians, or Shakespeare’s tragedies? Searching for those themes in him is I think a fundamental error, an error of perspective, perhaps a certain lack of sympathy for the complex of values that Ovid represents. Those values were understood, perhaps subconsciously, by Western civilisation. Not only have Ovid’s charming tales, with their strong visual impact, entered the European bloodstream, but the values of the Goddess entered too, along with them, and tempered the European world-view: emerging in Shakespeare for example as the profound perspective of his heroines as the ‘souls’ of his male protagonists, much as Beatrice is an aspect of Dante’s soul, and tempers his political harshness and formal intensity with the softness of love, and mercy.

Indeed the aspects of the myths that interest Ovid are not wholly determined by his choice of theme. He selects carefully, he retells carefully, and he returns again and again to his core values, not in a rigid and monolithic way, but in the fluid and graceful patterns of the dance. Ovid flies on Daedalus’ wings, but constructs no deceptive infernal labyrinth, and builds no solid temple to a pre-determined prophetic destiny. Ovid lays out that choral space for the goddess, and he builds her a honeycomb of gold, filling each cell with something sweet and nurturing, something closer to the dancing Graces, the three who give, receive and thank, and closer too to that living Minoan hive where the Cretan Lady of the Creatures could take her place among the beauties of nature and the loving mind.

I want, in this work, to identify the values around which the dance of the Metamorphoses takes place, and examine the honeyed cells that are its beauty and charm. Ovid does not laugh out loud with, and at, the world as he did in the Amores and the Art of Love, he smiles instead, throughout the Metamorphoses, with the smile of acceptance and delight.

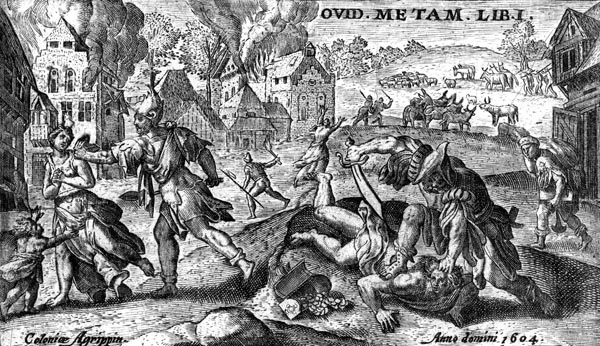

Of the dual ways, that of tragedy and epic on the one hand, dealing with the extremes of human experience, and that of moderation and humane values on the other, Ovid chooses the latter, the ‘middle’ way that Daedalus advises Icarus to choose in his flight, though to no avail. Ovid’s keynotes I suggest are three, Nature, the Goddess (and her values) and Pathos. Nature, primarily as beauty and refuge, the place of resolution: the Goddess as love and compassion, magic and feminine power: and the pathos of fate which is suffered and endured. Ovid wishes to engender not awe and catharsis, not the clash of giant forces, but the awareness of beauty, empathy, and the normal human condition. And he does it because it is his own innermost pre-disposition. It is the natural mode of his mind And in identifying with those values, so that they are almost disguised beneath the surface of his thread of stories, he transmits them to Western culture, so that they re-emerge constantly, and flow towards the values of the Renaissance, the Enlightenment and Modernity. His focus is on men and women, gods and goddesses, entangled in love and fate, flawed by the common failings of pride and jealousy, desire and anger, caught up in a pattern of harm, or potential harm, and resolution, but without the extreme anguish and crushing guilt of tragedy, or the grim power of epic. Certainly he re-tells myths which have immense tragic potential, and were treated by tragedians elsewhere, Pentheus’ death (Book III:511) at the hands of the Bacchae for example, or Niobe’s fate (Book VI:146), both of them victims of their own pride and impiety. But the majority of the stories he recounts are gentler, softer, and subtler. He is interested in charm, beauty, and decorative values, morally in empathy and pity rather than ruthlessness, in kindness rather than cruelty, in loyalty as well as disloyalty, in moderation, forgiveness and acceptance as well as excess and punishment. And those values are not lesser, more trivial, less worthy of interest, they are in fact the fundamental values of a modern society bound together by the recognition of rights, the workings of compassion, and the acceptance of the unequal and perverse workings of chance and intent. Ovid’s way is an almost Taoist understanding, partly visible in Epicureanism and Stoicism, of the inexorable flow of all things, a realisation of the dangers, and consequences of mindless action, an instinctive humaneness, empathy and love of peace, and a delight in Nature (including human nature) as the matrix of birth, life, sexuality and death. Even without the complex enhancements (and distortions) of Christianity, those ‘pagan’ values, existing in the Greek and Roman world, would have been passed on into the life of the European intellect. They emerge for example in Venetian painting, in Mozart’s music, in Tolstoy’s novels, in the Romantic Movement, in some form in most of the great art of Europe.

‘The death of Niobe's children’

III The Structure of the Metamorphoses

But surely ‘The Metamorphoses’ has no structure? Certainly it is not the Divine Comedy, nor does it unfold like a Shakespearean plot. The approach is different, but neither the dance nor the honeycomb is an unstructured entity.

The thread of the dance, the necklace on which Ovid strings the myths and stories is History, the mythological history of Ovid’s world: and each tale must be threaded in its proper place so that it can all be told, ‘from the world's first origins to my own time’.

The result of each story is a transformation. Caught in some way by fate, his mythical characters end in a natural resolution. They find refuge from their unhappiness in nature, or are made part of nature in punishment for their sin, or, if they are heroes identified with Rome, they are raised to the skies as gods. And Ovid returns again and again to the same themes within the stories, each set of the dance circling around the central atmosphere he wishes to create, one that transmits his values. The dancing floor belongs to Ariadne, the values are the values of the Goddess, and the dance is hers: the necklace, which is also an encircling crown, is hers.

A thread of time: a necklace of stories: a series of dances. Each cell of the honeycomb, of history, is filled, with the honey of myth. How long does it take to complete the dance, to fill the honeycomb with sweetness? Fifteen nights, fifteen books, from the dark of the moon, from Chaos, to the full moon, the shining splendour of Augustan Empire. The moon is the Goddess, and her light that waxes, and will wane, is the light of alteration, change, the transformations of the world. Ariadne and her Maidens dance, while the Fates, the Goddess in triple-form, spin the thread of that dance, the dance of events, and the story of humanity. And at the end what is left is the honeycomb, the golden creation, its cells filled with sweetness: the creative act has led to the ‘timeless’ creation. Yet by opening the work, to read it once more, the thread is taken up, the dance unfolds again, time is conquered through time, the music repeats, the story is told.

Muthos , is an utterance. Muthoi are the traditional stories of the gods and heroes. Plato first uses muthologia, mythology, to mean the telling of stories. Collections of Greek mythological tales existed before Ovid. Aemilius Macer, a friend of his, translated the Ornithogonia of Boios. Nicander of Colophon had written another. Parthenius, the Greek, tutor to Virgil and Tiberius, had written a Metamorphoses. And there are mythological references throughout Homer, Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns, the Greek dramatists, Pindar, and the other Greek poets. Ovid’s sources were many, the selection process his own. The theme of transformation is strung on the thread of history. Not a formal history, since Ovid is dealing mostly with the pre-history of myth, but a loose history. He places myths in the sequence accepted by the poets, starting with ‘ancient’ times, and progressing through the tales of the gods and early heroes from Thebes, Argos, Athens and Crete, until we reach the hero cycles of Hercules, the Seven Against Thebes, and the Trojan War. Along the way we see the effects of Greek expansion across the Mediterranean, and into the Black Sea, as tales are set in the colonies of Sicily and Lydia, Caria and Thrace. We have glimpses too of the Theban Confederacy and the Minoan Federation. Then we have the myths of Rome and its supposed Trojan origins, of Aeneas and Romulus, ending in the genuinely historical material of the Caesars. Combined with skilful connections between the stories, the effect is of a seamless tapestry of tales, a work of art in a very visual sense. The weaving of the tales is part of the charm of the work.

‘Cygnus battles with the Trojans against the Greeks’

Ovid tightens the structure, with echoes between the books. In Book X two thirds of the way through Orpheus sings the stories, while in the earlier corresponding Book V, his mother Calliope, the Muse, sings them. The mock-heroic fight scenes of Perseus and Phineus, the Calydonian Boar hunt, and the Lapiths and Centaurs, are placed in Books V, VIII and XII, to balance and weigh the narrative. And, by pure chance, there is a humble image of the whole work, at its heart, in Book VIII:611, on the table of Philemon and Baucis. ‘In the centre was a gleaming honeycomb.’

‘Eurytus seizes Hippodames’

Within a largely pre-determined historical sequence, through careful selection and skilful presentation, Ovid creates the effect of continuous flow. What he is creating is a dancing floor, and a honeycomb, not a temple or a labyrinth. The structure has the permanence and transience of history, it is a necklace where one can pick up a bead at any point and examine it independently, or pass over all the beads on the thread, or step back and look at the whole effect, diversity in unity. Or it is a garden, where between the entrance and the exit you can find every kind of flower, so long as it charms and delights. It is an Odyssey without Odysseus.

Woven within the history are the gods and goddesses, and they provide a strong element of continuity, the goddess and the god in their many manifestations, returning and displaying their characteristics. They too are a part of the dance, a vital part, and as masked dancers they afford us recognition of similar forces acting throughout the tales, forces of ‘human’ interaction and passion. Disguised as humans the divinities cause havoc, and interfere with human affairs. Piety is a real need, to be able to recognise, and respect, the divine and sacred. Failure to do so leads to disaster, a result of hubris, of pitting oneself against the greater forces. The gods and goddesses enter into human life: the world of the divine and the human is a continuum. In such a continuum it is easy to fall foul of a deity.

‘Venus immortalises Aeneas’

The structural effect of the ever-present gods is echoed in the Roman dimension. Ovid, lightly, displays Augustus and Livia as his Jupiter and Juno. It was Venus-Aphrodite after all who mated with a human, Anchises, to produce her beloved Aeneas, and Aeneas the Trojan was the ancestor of Augustus the Roman. It is Venus-Aphrodite who ensures the deification of Aeneas (Book XIV:566), of Julius Caesar (Book XV:843) and, we might anticipate, Augustus also. It is Venus-Aphrodite for whom the golden honeycomb was made. And it is Venus-Aphrodite, goddess of love, who is Ovid’s goddess, the Muse of the Amores, the Heroides, and the Art of Love. So the doings of Jupiter and Juno and their amusing married antagonisms, provide a mirror image of the ‘gods’ of Imperial Rome, to whom Ovid has the same ironic affectionate half-mocking attitude as Homer and the Greeks displayed to their deities. We might go on to speculate that a few other members of the Imperial family take their place as Greek divinities, Julia the Younger, perhaps, as Venus herself, Tiberius as Mars. Ovid hints at Julia the Younger’s possible role as his Muse, his Corinna, in the later poems from exile (Tristia IV:I:1-48 et al), and involvement with her set may have been the reason for that disastrous banishment.

Given the looser and less-structured approach to his material that was dictated by his interests, the form Ovid adopted, which uses the thread of history, the theme of metamorphosis, the repeated appearance of the Gods and Goddesses, and the echo of the Imperial family, along with a few building block devices to create internal echoes, is extremely successful, and reading the Metamorphoses through gives a satisfying feeling of continuity rather than a sense of unrelated material. Interestingly the mythological content of Homer’s Odyssey is also loosely integrated into the narrative, and the continuity there is often provided by the presence of Odysseus and Athena his protecting goddess. The episodes and locations can seem gratuitous, but are there to fill out the story with interesting incident, and amplify the notion of the Mediterranean voyage. Homer of course relied on his audience filling in further detail behind the mythological references. Ovid’s work, also, delights in the way a well-made necklace does, or a solid stone floor, where individual beads or stones have their own shape and character, while fitting onto the thread or into the space, and making a varied whole. Ingenuity and charm of detail are essential to their harmonious creation. Perhaps his own ideal was the carefully designed mosaic or a clever tapestry, like those Arachne and Minerva weave. (Book VI:70).

IV Ovid’s Interest in Myth

The myths for Ovid were the perfect raw material, to be used to reflect a world of Fate, where human beings are subject to external and internal forces, and where the emotions generated form patterns to stir empathy in the spectator. His gods are superior forces, with predominantly human characteristics and behaviours amplified by their divinity. They too are partially subject to Fate, as we shall see later. Nature too can act as force, though natural forces are most often divinely initiated. Behind every numinous aspect of the natural world may be the influence for good or ill of a god or a goddess. And within the human being are the same drives and forces that exist, amplified, in the gods. These are the attractive forces of love and passion, the thwarted forces of jealousy and anger, to which are added the human and selfish forces of pride and greed, the thrill of fear, the agonies of loyalty, the conflicts of inner imperatives, leading to the great ocean of empathy, pity and compassion as flight or punishment, fate and overwhelming force take effect.

Ovid takes over the Greek world of myth, as Roman culture itself did, and identifies himself with that backcloth of Nature, with the overriding force of Fate, with the drives and emotions of divinities and mortals, but with his emphasis on transient humanity, hemmed in by realities, whose lives generate reaction in us, empathy, and understanding. His approach is not religious in any conventional sense, nor is Ovid interested in extreme behaviour, except as the artist in him, or us, might stare at a grotesque horror in an exhibition, at a murderous Thyestes or a blinded Oedipus. Ovid wishes to create empathy rather than tragic terror. He wants us to identify with the protagonists and feel for them, as he does. So he is more interested in heroines than heroes, in ordinary mortals rather than tragic monstrosities. Likewise it is not the vast sweep of events that draws him, not epic moments, not the wars of the Iliad, or Aeneas’s battles. Ovid is interested more by the possibilities of emotion and experience, psychic changes, and individual reaction. The gods are humanised. Human values are essentially civilised, the raw is cooked, and the wild tamed wherever possible. The human defence against the disorder that breaks in on us is affection, loyalty, endurance, and trust. Nature is ambiguous, often beautiful and beneficent, occasionally cruel and indifferent, a marvellous flow. Ovid is a proponent of civilisation, and of the gentler values of the Goddess, her benign moods and masks. Disorder finds its resolution in renewed order through transformation, rather than catharsis. Tragic terror is evaded, as a response, in favour of pathos, a saddened recognition of human frailty, and the greater powers outside us and within us.

‘Latona turning the Lycian farmers into frogs’

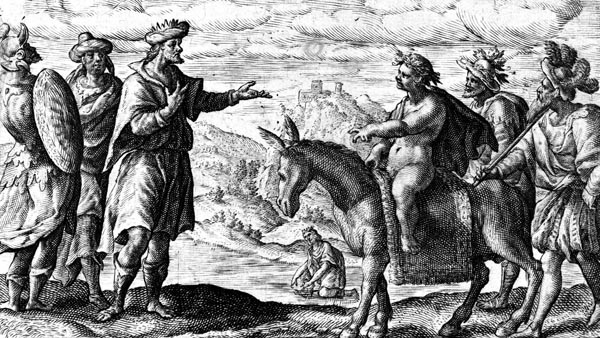

Despite his lateness in antiquity Ovid is content to tell the myths without analysing them in any way. There is no suggestion that he is interested in the myths as explanations of natural phenomena, other than the ways in which the colours and shapes and behaviours of creatures are charmingly ‘explained’ by their being the results of a transformation. So the swallow, Philomela (Book VI:401), and the woodpecker Picus (Book XIV:320) show markings that reflect their fate. And the frogs, the transformed Lycian farmers (Book VI:313), and the magpies, the Pierides (Book V:642) echo in their behaviour the humans from whom they derived. Nor is Ovid interested in religious ritual per se, or the patterns of social behaviour that might be reflected in a myth. Rites of passage and human sacrifice, for example, are not central to his focus. Even animal sacrifice disturbs Ovid, the vegetarian. Heroic quasi-religious quest too is outside his scope, despite the appearance of Perseus, Theseus and Hercules, in vignettes from their hero cycles. When the rituals of religion do appear, those of Isis for example (Book IX:666), they are already softening towards the religion of the personalised deity, of the gods and goddesses of every-man and every-woman, precursors to Christianity. It is interesting that at the holiest sanctuary of Isis in Greece at Asclepios, no one could enter the holy place except those personally chosen by Isis and summoned by visions in their sleep (Pausanias X.32.9). In the Metamorphoses, Isis asserts female rights, and reveals the human face of the goddess, before bringing mercy to Telethusa, and Iphis, in just such a vision. In a similar instance of personal communion Bacchus forgives Midas (Book XI:85) by prompting him to a ritual cleansing akin to baptism.

‘Bacchus honours the wishes of King Midas’

It would be right to say that Ovid allows the myths to speak for themselves, and transmits what they contain without comment, except that it should also be said that he is both highly selective in what he presents, and is ever-present in the detail of that presentation, so that he creates by a multitude of little effects the ambience and environment through which his own humane, civilised values are reiterated and reinforced.

V Nature,The Matrix

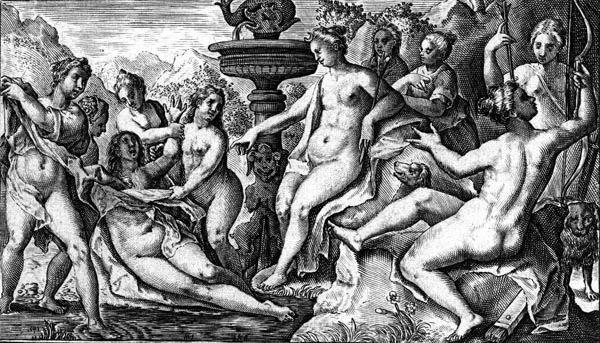

‘Peleus and Thetis’

Most of the scenery in Ovid’s theatre is pastoral. The stories take place in the open air, or in ancient Greek cities, the size of our small towns, open to the sky, and continuous with nature. It is the world before modernity. Nature is beauty and charm, a place of delight, out of which the gods and goddesses emerge with fatal force, involving themselves in human lives, and evoking a response. Nature is the goddess, in her most ancient, her Palaeolithic and Neolithic, form, and Ovid is telling us that as such she is sacred and enticing, inviolable and nurturing. She is the matrix of humanity and its erotic root. As such she is passive and welcoming. In her sacred and inviolable mode, nature as given to humanity, untouched and mysteriously present, she is virgin, she is Diana-Artemis, the Lady of the Wild Creatures, or Minerva-Artemis, goddess of Mind and invention, of womens’ arts and crafts. In her seductive and erotic role, nature as passion and procreation, she is Venus-Aphrodite, and the magical witches and shape-shifters who are her masks, Circe (Book XIV:1) and Medea (Book VII:1), Thetis (Book XI:221) and Mestra (Book VIII:725). In her maternal and nurturing role, nature as life-giver, she is Juno-Hera, sister-wife of Jupiter-Zeus, goddess of brides and women in labour, she is Ceres-Demeter, guardian of the crops, and mother of Proserpine-Persephone the force of seasonal change, and she is Cybele, ancient fertile mother goddess of Asia, and Isis, grieving wife and mother of Egypt.

‘The Great Flood’

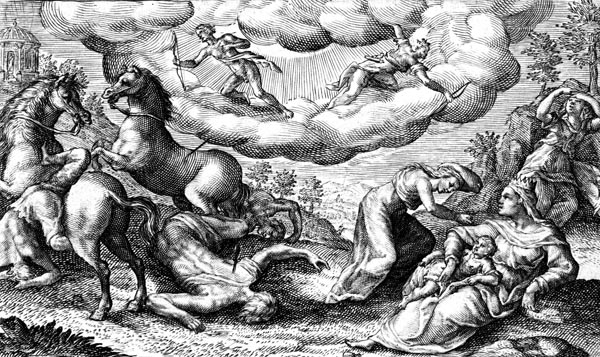

This last mode, as Isis, gives a hint as to Ovid’s preferred role for Nature in the Metamorphoses. It is primarily a place of refuge and resolution. True there is also the experience of the floods that affect Deucalion and Pyrrha (Book I:244) and Baucis and Philemon (Book VIII:611) and the plague that decimates the island of Aegina and torments Aeacus (Book VII:453), but these are initiated by deities, that is by the unnatural forces of the gods and goddesses, applying themselves for ‘human’ reasons to human affairs. Nature itself is mother Earth, the passive matrix of life, whom we see disturbed by Phaethon’s passage (Book II:31), and a sanctuary, a receptacle for that series of trees and rivers, birds, beasts, and flowers, stars, and stones into which mortals are transformed, finding there a refuge from unhappiness, or a mode of punishment that is a resolution, almost a final forgiveness.

‘The fall of Phaethon’

Ovid’s interest in an afterlife, and some place of retribution hereafter, is minimal, his views reflected perhaps in the doctrine of the transmigration of souls that Pythagoras teaches (Book XV:143), certainly he is no Virgil or Dante, dwelling on the possibilities of the Underworld. Aeneas’s journey there (Book XIV:101) is passed over swiftly, and Orpheus’s visit (Book X:1) is mainly captured in conventional references to some of the famous inmates of Tartarus. His perception is rather of a natural world, where fate takes a hand, and where the final resolution is not so much judgement as re-absorption, the spirit taken back into the realm of nature from which it came, only transformed. The ancient Greek animist world with its continuity, all aspects of nature even rocks and stars possessing ‘life’, is transmitted through his work, and the natural world of the Metamorphoses therefore feels older than the world of the tragedians, older in many respects than Homer, though in the retelling a Roman veneer is added to the surface.

Nature has a pre-scientific fecundity. Creatures can arise out of matter by autogenesis. They do so in the beginning, after the flood, when, men and women have been re-created from stones, and animal life is born spontaneously from the marshy ground. (Book I:416). Pythagoras, in a structural echo, asserts the doctrine again in his teachings at the end of the work (Book XV:361). Nature too can be violated. The people of the Iron Age reveal the rapacity of the human race, tearing their way into the bowels of the earth, and the land moves from common access, to the light of the sun and the air for example, to private possession. (Book I:125). This is echoed again by Latona (Book VI:313) who declares that sunlight, air, and water are a universal right, free to all. Nature has granted them in common: only humanity creates ownership. The text is asserting that ancient view of things held by nomadic and hunting peoples, an inability to understand how land can be owned, a focus on the paths across territory, and the knowledge of where best to find resources, rather than on demarcation, boundaries and surveying.

‘The Iron Age’

Spontaneity may be a feature of a given metamorphosis as well. True, it is often a god or a goddess who initiate a transformation: Jupiter turns Io to a heifer to hide her from Juno (Book I:601), Minerva punishes Arachne’s hubris, then, when the girl cannot bear her punishment, and attempts suicide, pities her and turns her into a spider (Book VI:129), Circe transforms Scylla into a monster out of jealousy over Glaucus, poisoning the pool where the girl bathes (Book XIV:1). But there are occasions when the final re-absorption by nature happens seamlessly, an organic mutation, apparently without any divine intervention. The sisters of Phaethon become poplar trees weeping amber (Book II:344), Procne, Tereus and Philomela are transformed into birds after the horrors of their murderous tale (Book VI:653), Hecuba becomes a howling dog, and is pitied by all the gods (Book XIII:481), and the city of Ardea a grey heron (Book XIV:566). It is as though Nature is capable, with minimum intervention by the divine forces, of triggering the resolution of their story.

‘Jupiter transforms Io into a heifer to hide her from Juno’

The Greeks, and Ovid, show a predilection for certain types of change. Of the hundred and thirty or so major transformations of the Metamorphoses, sixty or more are into birds (many of these are lesser known tales), traditionally symbolic of the soul or spirit, and with individual characteristics and markings that allow variety of description and situation. Among the better known, Alcyone and Ceyx, drowned by the waters, become the mythical Halcyons (Book XI:710), Cycnus, mourning for Phaethon, the swan (Book II:367), the Pierides, defeated in their contest with the Muses become magpies (Book V:642), and Scylla, who betrayed her father and city to Minos, becomes the rock-dove (Book VIII:81).

Changes into creatures account for a further dozen or so of the transformations. Actaeon is torn to pieces as a stag, for trespassing on Diana’s sacred pool and seeing her naked (Book III:232), while Iphigenia transformed to a deer is concealed by Diana at Aulis (Book XIII:123). Arachne becomes a spider, altered by Minerva (Book VI:129), Callisto a bear (Book II:466), Hippomenes and Atalanta lions (Book X:681), the Lycian farmers frogs (Book VI:313). And half a dozen intriguing changes reverse the ‘natural’ order creating human beings from ants, the Myrmidons (Book VII:614), or from inert matter like Galatea, the statue that turns into a living girl (Book X:243), and even creating dolphins from Aeneas’ fleet of ships (Book XIV:527).

‘Diana and Actaeon’

The remaining third of the metamorphoses, forty or so, are mainly dedicated to the gentler changes into flowers and trees, or to those of a less gentle kind, into water, or, harshest of all, stone, while a handful of girls simply waste away. There are a few transformations into star clusters. A few mortals are deified. And then there is the intriguing handful of changes in sexuality.

The trees are fairly numerous, with a dozen or so instances. Notable among them are the Heliades, the mournful sisters of Phaethon, who become poplars (Book II:344), Cyparissus beloved of Apollo, who is changed into the cypress tree (Book X:106), the incestuous Myrrha who bears Adonis (Book X:431) and oozes myrrh, Dryope the lotus, who unwittingly offends the nymphs (Book IX:324), and loveliest tale of all, Philemon and Baucis who, dying together, are transformed simultaneously to oak tree and lime tree, to remain priests of the temple of the gods after their death (Book VIII:679).

‘Apollo pursues Daphne’

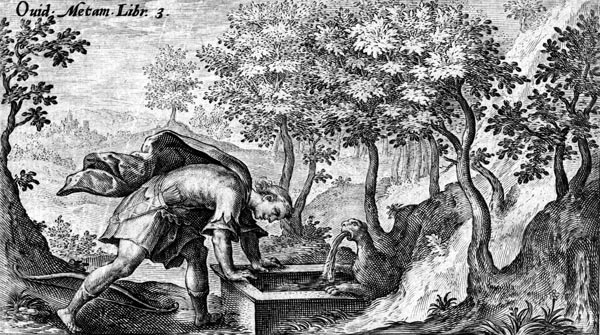

Of the handful of flowers Hyacinthus (Book X:143), who shares his flower identity with Ajax (Book XIII:382), Crocus, whose lover Smilax becomes the flowering bindweed (Book IV:274), and Narcissus (Book III:474) are obvious examples, while Adonis becomes the anemone (Book X:708), and Clytie the heliotrope (Book IV:256). All are ‘lovers’ except Ajax, he being chosen to account for the markings on his flower. Hyacinthus is loved by Phoebus, Crocus by Smilax, Narcissus loves himself, Adonis is Venus’ consort, Clytie loves Sol.

‘Narcissus falls in love with his own reflection’

There are eight or more transformations to water, including Marsyas, loser in his music contest with Apollo, who becomes a river (Book VI:382), as does Arethusa pursued by the river-god Alpheus (Book V:572), and Acis, destroyed by Polyphemus (Book XIII:870). Helle, falling from the golden ram (Book XI:194), and Icarus (Book VIII:183), whose waxen wings melted, give their names to seas. The incestuous Byblis becomes a fountain (Book IX:595).

‘Alpheus and Arethusa’

Stones, islands: a dozen or more mortals reach the inertness of matter. That fate is often attendant on some form of sinfulness. Aglauros is petrified by Mercury for her sin of envy (Book II:812): Battus (Book II:676), and Mercury’s son Daphnis (Book IV:274) for disloyalty. Niobe is punished for her boastful pride (Book VI:267), and Anaxarete for her hard-hearted rejection of Iphis (Book XIV:698). The Propoetides, the sacred prostitutes, are condemned for their lost sense of shame (Book X:220). The Gorgon’s head transforms Perseus’ enemies (Book V:149). Lichas is hurled from the cliffs and turned to stone merely for being an unlucky servant (Book IX:211), while Sciron meets the fate he has offered others, and is altered to a sea-cliff (Book VII:425).

‘Anaxarete and Iphis’

Cyane, whose pool is desecrated (Book V:425), and Canens devastated by the loss of Picus (Book XIV:397) simply waste away, while Semele, mother of Dionysus-Bacchus is consumed by fire (Book III:273), and Echo (Book III:359) and the Sibyl (Book XIV:101) are fated to become voices only.

Arcas and his mother Callisto (the Bears: Book II:466), and Erigone (Virgo: Book X:431) are set among the stars, along with Ariadne’s crown (Corona Borealis: Book VIII:152). While Glaucus, the grass-eater (Book XIII:898) and Ino and Melicertes, persecuted by Athamas (Book IV:512) become gods, as do the heroes of Rome, namely Hercules, patron God of the site of the City (Book IX:211), Aeneas the mythical creator of the race (Book XIV:566), Romulus the Founder and his wife Hersilia (Book XIV:829), and Julius Caesar, creator of the Empire (Book XV:843).

Lastly there are the fascinating transformations of sexuality. Iphis (Book IX:764) and Caeneus (Book XII:146), are girls who become boys: Salmacis and Hermaphroditus merge bodies (Book IV:346): and Tiresias, experiences life as a woman and then is transformed back into a man, making him uniquely qualified to testify to the superior pleasure women derive from sexual intercourse (Book III:316). Ovid subversively both attests to the fluidity of sexuality, and to the possibilities of female erotic delight, even self-sufficiency.

‘Salmacis and Hermaphroditus’

The mix of transformations leans towards the terrestrial, birds outnumbering creatures, and trees and flowers offsetting the waters and stones. Stars and divinities are less evident. Ovid’s and the Greeks’ sights are on the natural world of earth rather than on the starry heavens, love and passion outweigh punishment, and beauty is a beauty of this life rather than some other. So Nature emerges from the tales and surrounds them. It is the matrix from which things arise, spontaneously on occasion, from the nurturing soil and the moisture of generation. The ancient goddess is passively and implicitly present within it, ready to take back into herself failed, unhappy or remorseful spirits, those whom fate pursues or has maltreated, those who have reached their apotheosis, or their stony termination, the unfortunate and the sinful, the loving and the loved.

Ovid evokes nature constantly through pastoral description, sheer visual charm that prompted later a wealth of Renaissance landscape imagery. There is Daphne pursued by Apollo, through the pathless woods and the windblown fields, and along the banks of the Peneus, in that vale of Tempe beneath Parnassus. The girl destined to be laurel: to hurl herself into ‘shining beauty’, into the silence of her own leaves, so that Phoebus held his cool immortal hand against the bark, to feel her still-beating heart (Book I:525). There is Diana, bathing in the still, immaculate pool, where Callisto unveils and reveals her shame (Book II:441), or where Actaeon, stumbling upon the sacred inwardness of nature, sees the goddess naked. (Book III:165). There is Europa, drawn out to sea by sly Jupiter, sitting astride the bull’s white form, while her clothing blows behind her in the breeze (Book II:833). There is Narcissus by another ‘unclouded fountain, with silver-bright water’ that is untouched and inviolate, watching his reflection under the shadows of the trees, and falling for himself, chasing the fleeting and intangible image (Book III:402). Salmacis entwines Hermaphroditus in the pool ‘clear to its very depths’, clasping his ivory-white neck (Book IV:346). Perseus rescues the virgin Andromeda, blushing through her warm tears while chained to the rock above the waves, where he hovers in his light armour, wings fluttering on his ankles (Book IV:706).

‘Diana and Callisto’

There is Proserpine in the sad vale of Enna, that space of Sicilian flowers at the heart of the island, spilling the petals from the folds of her clothing, snatched up by the dark God to vanish with his chariot and horses through the depths of Cyane’s trembling waters (Book V:385). There is Medea at midnight, hair unbound, robes unclasped, stretching her arms above her head to invoke the triple goddess, Hecate, and the powers of the Moon (Book VII:179). There is Atalanta, the warrior girl from Tegea, chasing the Calydonian boar through the deep valley (Book VIII:260). Philemon and Baucis are shown turning back to see their humble cottage transformed, and the countryside sinking beneath the waves (Book VIII:679). Orpheus gathers the trees and creatures around him (Book X:86). He sings the fate of Adonis ‘dying on the yellow sand’ transformed to the anemone flower, ‘lightly clinging, easily fallen’ (Book X:708)

‘Medea invokes Hectate’

There is Midas, purging himself in the waterfall of Pactolus (Book XI:85). There is the House of Sleep, where no door dares to creak (Book XI:573). There is Polyphemus’s pastoral landscape, the monster and the lovers, beauty and the beast (Book XIII:789), and there is Glaucus lost to the waves (Book XIII:898). There is the house of Circe, who wears ‘a shining robe’ of witchcraft (Book XIV:223). There is Hippolytus, travelling the shore of the Isthmus, meeting the bull from the sea, ending as a king of the wood at sacred Nemi, where the nymph Egeria ‘melted away in tears’ (Book XV:479). There is Venus, goddess of the whole work, of the leading passion that drives so many of its characters, Aphrodite of Eryx, mistress of the golden honeycomb, loosing Caesar, as a comet, from her breast, to climb above the full Moon, and shine over a resplendent City (Book XV:843). Scene after scene reinforces the feeling of natural beauty, of pastoral setting, of the charm and resilient stillness of nature, its ability to soothe and inspire and transform us.

‘Polyphemus and Acis, beloved by the nymph Galatea’

And Nature is overwhelmingly benign, a sanctuary, a place of refuge, where girls can flee from the god, where desolate mothers and wives can sink to rest, where sins of passion are redeemed in forgetfulness and transformation, where crimes are expunged in the silence of stone, or the muteness of birds and beasts. Only once perhaps does Nature itself cause havoc without a seeming cause, when the tempest overtakes Ceyx, and Alcyone finds his returning body, carried to her by the tide. Nature is repetition: ages, cycles, seasons, circuits, masks. The same gods and goddesses perform similar actions, fresh mortals undergo new but familiar emotions. The same faces possess different names, or different forms have the same, hidden, name. The breeze that rustles through Ovid’s groves and sighs across his meadows and fields is the wind that stirs the oak leaves at Dodona, the secret whisperings of the ancient natural goddess-filled world, of that Dione behind Zeus, of Themis and Latona behind the later goddesses, or of that Lady of the Wild Creatures on Crete, of that lady of the grassy Neolithic plains, or she of the Paleolithic meadows below the cliff-walls, leading to the limestone caves, and their secretive art.

The mood of the Metamorphoses, its lasting impression, is not that of power, of the harsh bright Aegean sunlight, of the dark fires of tragedy, of the bloody sand below the walls of Troy, the blinded agony of Oedipus, the murdered corpses of Cassandra and Agamemnon, Clytemnestra and Aegisthus. It is not torment in Tartarus, or the epic struggles of Aeneas. It is not Odysseus visiting a bloodless underworld where the ghosts twitter like bats in the unfulfilled darkness, or while away the tedium of eternity on the lifeless fields of Elysium. The atmosphere of the Metamorphoses is of human life, on this earth, here and now, in nature, and appreciating nature, describing it, embracing it, finding refreshment within it, taking nurture and sustenance from it, while holding it sacred and inviolable, revering the primal Goddess, and seeing her shining face among the leaves.