La Vita Nuova

‘The New Life’ of Dante Alighieri

Sections XXI to XXX

Listen to audio-book edition sample:

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

In Memory of Jean (1922-2001)

Contents

- XXI How Beatrice wakens Love

- XXII The death of Beatrice’s father

- XXIII Dante’s vision of Beatrice’s death

- XXIV His sonetto to Guido Cavalcanti

- XXV His justification of his personification of Love

- XXVI His further praise of Beatrice

- XXVII Her effect on Dante

- XXVIII What he will say concerning the death of Beatrice

- XXIX The number nine

- XXX His letter to the Rulers

- Index to the First Lines of the Poems

XXI How Beatrice wakens Love

XXI How Beatrice wakens Love

After I had treated of Love in the above verse, I had the will to desire to write again, in praise of this so graceful lady, in which I would show how Love is wakened through her, and not only wakened where he is sleeping, but where he potentially is not, she, working miraculously, making him come to be. And then I wrote this sonetto, which begins: ‘Ne li occhi porta’.

In her eyes my lady bears Love,

by which she makes noble what she gazes on:

where she passes, all men turn their look on her,

and she makes the heart tremble in him she greets,

so that, all pale, he lowers his eyes,

and sighs, then, over all his failings:

anger and pride fleeing before her.

Help me, ladies, to do her honour.

All sweetness, all humble thought

are born in the heart of him who hears her speak,

and he who first saw her is blessed.

How she looks when she smiles a little,

can not be spoken of, or held in mind,

she is so rare a miracle and gentle.

This sonetto has three parts: in the first I say how my lady fulfils what is potential in actuality through that most noble part, her eyes: and in the third I say how she does the same through that most noble part, her mouth: and between these two parts is a brief part, which is almost a demand for help from the preceding and following parts, and begins with: ‘Aiutatemi, donne: Help me, ladies’. The third begins with: ‘Ogni dolcezza: All sweetness’.

The first is divided in three: in the first part I say how virtuously she makes noble all she sees, and that is as much as to say that she brings love into existence potentially where he is not: in the second I say how she brings love to actuality in the hearts of those whom she sees: in the third I say how her power operates virtuously on their hearts. The second begins with: ‘ov´ella passa: where she passes’: the third with ‘e cui saluta: and in him she greets.’

Next where I say: ‘Aiutatemi, donne’ is shown to whom it is my intention to speak, calling on ladies to help me honour her. Then where I say: ‘Ogne dolcezza’ I say the same as I said in the first part, in respect of two movements of her mouth: one of which is her speech so sweet, and the other her marvellous smile, except that I do not say what effect the latter has in other’s hearts, because the memory cannot retain it or its effect.

XXII The death of Beatrice’s father

XXII The death of Beatrice’s father

Not many days after this, as it so pleased the glorious Lord who did not deny death even to himself, he who was the father of this miracle who was seen to be this most noble Beatrice, in truth himself ascended from this life into glory.

It is the case that such a parting is saddening for those who are left behind, and are friends of the one who has gone from them: and there is no more intimate friendship than between a good father and a good daughter, a good daughter and a good father: and this lady was of the highest degree of goodness, and her father, as many believe and it is true, was to a high degree a good man: it is clear that this lady was filled with the most bitter of sorrows.

And because it is customary, following the manners of that city, for lady with lady, and gentleman with gentleman, to gather at such mourning, many ladies gathered where this Beatrice wept piteously: so that I, seeing some of the ladies returning from her, heard them talking about that most beautiful lady, and how she grieved: among their words I heard it said: ‘Certainly she weeps so, that anyone who gazes at her would die of pity.’

Then those ladies passed by: and I was left in such sadness that many tears bathed my face, such that I covered my face with my hands many times: and if it were not that I waited to hear more of her, since I was in a place where most of the women who left her would pass, I would have hidden myself as soon as the tears overpowered me.

So I remained in that same place, other ladies passing close by me,

among whom I heard these words mentioned as they went: ‘Who of us can ever be happy again, who have heard the piteous speech of this lady?’ After them other ladies passed, who went by saying: ‘This man is one who weeps no less then if he had seen her, as we have.’ Still others said of me: ‘Look at this man: who does not seem to be himself, he is so changed!’

And so as these ladies passed, I heard words about her and myself, in the manner I have written. Afterwards, thinking of them, I decided to write verses, considering I had a fitting reason for speech, in which I would compose all that those ladies had mentioned: and since I would have liked to have questioned them if it were not reprehensible to do so, I arranged the matter as if I had questioned them and they had answered.

And I made two sonettos: in the first I question, in the way I wished to question: in the other I speak their reply, taken from what I heard them say, as if they had answered so. And I began the first: ‘Voi che portate la sembianza humile’, and the other: ‘Se´tu colui c´hai trattato sovente.’

You who bear a humble look,

with eyes cast down, displaying sadness,

where do you come from that your colour

seems to have changed to that of pity?

Have you seen our gentle lady

bathing the face of Love with tears?

Tell me, ladies, what my heart tells me,

since I see you going by so nobly.

And if you come from all that sorrow,

I beg you to stay with me a while,

and how it goes with her, do not hide from me.

I see that your eyes are full of tears,

and I see you return so transfigured,

that my heart trembles at having seen.

This sonetto is divided in two parts: in the first I call to and ask of these ladies if they come from her, saying I believe it to be so, since they return so ennobled: in the second I beg them to speak to me of her. The second begins with ‘E se venite: And if you come from’. After it is the other sonetto, as I have said before.

Are you him that so often spoke

of our lady, talking to us alone?

You well resemble him in voice,

but the face seems to us another man’s.

And why do you weep so bitterly,

who from yourself stir pity in others?

Did you see her weeping, that you cannot

hide your sorrowing mind within?

Let us weep and go by sadly

(who tries to comfort us commits a sin),

for in her weeping we have heard her speak.

She has a face so filled by pity,

that he who wished to gaze on her

weeping, would fall dead before her.

This sonetto has four parts, in accord with the four modes of speech of the ladies on whose behalf I reply: and as they are set out clearly enough above, I do not intend to spell out the content of each part, but only indicate them. The second begins with: ‘E perché piangi: And why do you weep’: the third: ‘Lascia piangere noi: Let us weep’: the fourth: ‘Ell´ha nel viso: She has a face.’

XXIII Dante’s vision of Beatrice’s death

XXIII Dante’s vision of Beatrice’s death

A few days after this it happened that a grievous illness affected a certain part of my body, from which I continually suffered for nine days from the most bitter pain: this made me so weak, that I was forced to stay like one who could not move. I say that on the ninth day, feeling almost intolerable grief, a thought came to me that was about my lady.

And when I had thought of her a while, I returned to thinking about my weakened existence: and seeing how fragile our strength is, even in health, I began to weep about our miserable state. Then, sighing deeply, I said to myself likewise: ‘Of necessity it must be that some time the most graceful Beatrice must also die.’

And it threw me into such intense bewilderment that I closed my eyes, and began to be tormented by imagining this, like a delirious person: so that at the start of the wanderings of my imagination, the faces of certain women with dishevelled hair appeared to me, who said to me: ‘You will surely die’: and then, after these women, diverse other faces appeared to me, terrible to look on, that said to me: ‘You are dead’.

So, my imagination beginning to wander, I came to a place not knowing where I was: and it seemed to me I saw women, weeping, with dishevelled hair, going through the street, in extreme sadness: and the sun seemed to me to be darkened, so that the stars showed themselves of a colour such that I judged they were weeping: and it seemed to me that birds flying in the air fell dead, and there were massive tremors.

And marvelling in this fantasy, and very fearful, I imagined that a friend came to me saying: ‘Do you not know? Your miraculous lady has departed this world.’ Then I began to weep most piteously, and I did not only weep in imagination, but wept with my eyes, bathing them in real tears. I imagined I was gazing at the sky, and I seemed to see a multitude of angels who were returning to their place, and in front of them they had the whitest of little clouds. It seemed to me these angels were singing gloriously, and the words of their singing I seemed to hear were those of: ‘Osanna in excelsis: Hosanna in the highest’: and I could hear no more.

Then it seemed to me that my heart, where there was so much love, said to me: ‘It is true, our lady lies dead.’ And at this I seemed to go to gaze on the body in which that most beautiful and noble spirit had lived: and the wanderings of my imagination were so intense that dead lady was shown to me: and it seemed to me that women covered her, her head that is, with a white veil: and it seemed to me that her face has such a look of humility, that she seemed to say: ‘I am gazing on the source of peace.’

In this imagining I felt so much humility at seeing her, that I called Death, and said: ‘Sweetest Death, come to me, and do not be cruel to me, for you must have become gentle, after being in such a place! Now come to me, who desire you greatly: and you will see that I already wear your colours’.

And when I had seen the sad offices completed that are usually performed for the bodies of the dead, it seemed I returned to my room, and there I seemed to gaze at the sky: and my imagination was so intense that, weeping, I began to say in my true voice: ‘O most beautiful soul, how blessed is he who beholds you!’ And while I was speaking these words, with a painful anguish of tears, and calling to Death to come to me, a young and gentle lady, who was beside my bed, thinking that my tears and my words were solely from grief at my infirmity, began to weep herself, with great fearfulness. So that other women who were in the room realised that I wept because of the distress that they saw created in her: so making her, who was closely related to me, leave me, they came to me to wake me, thinking that I was dreaming, and said: ‘Sleep no more’ and ‘Do not be troubled’.

And by their speaking this powerful imagining was broken off, at the moment that I was about to say: ‘O Beatrice, you are blessed!’ and I had already said the words: ‘O Beatrice!’ when I opened my eyes, suddenly, and realised that I had been imagining. And though I spoke her name, my voice was so broken by sobbing that I felt these ladies had not understood.

I was very much ashamed, but through Love’s counsel I turned my face towards the ladies. And when they saw me, they began to say: ‘He looks like a dead man’ and said amongst themselves: ‘Let us see if we can comfort him’. At which they said many things to soothe me, and questioned me about the reason for my fear. When I felt somewhat comforted, realising it had been a fantasy, I said to them: ‘I will say what came to me’ and I told them what I had seen from beginning to end, but withholding the name of the most graceful lady.

Afterwards when I had recovered from my illness, I decided to write some verses about these things, as it appeared appropriate to my theme. So I wrote this canzone which begins with: ‘Donna pietosa’ the ordering of which is made clear in the explanation that follows.

A lady, youthful and piteous,

greatly graced with human gentleness,

who was there where I called to Death,

seeing my eyes full of pity,

and listening to my empty words,

was moved by fear to intense weeping.

And other ladies who were made aware

of my state by her who wept with me,

made her go away,

and pressed about me to comfort me.

One said: ‘Do not sleep’,

and one said: ‘Why are you troubled?’

Then I left off my strange fantasy

calling out the name of my lady.

My voice was so full of grief

and broken by the anguish of my weeping,

that the name was only heard in my heart:

and with all my aspect filled with shame

that was so apparent in my face,

Love made me turn towards them.

They saw my colour to be such,

that they thought me like the dead:

‘Alas, let us comfort him’

they prayed, humbly, one then the others:

and often said:

‘What have you seen, that you have lost courage?’

And when I was a little comforted,

I said: ‘Ladies, I will tell you.

Lying there, thinking of my fragile life,

and seeing how slight its substance is,

Amor began to weep where he lies in the heart:

at which my spirit was so distressed

that sighing I said in my thoughts:

“Truly it will be, that my lady dies.”

Then I was so filled by distress,

I closed my eyes heavy with that evil,

and so scattered

were my spirits, they all went wandering:

and then imagination,

roaming wildly and far from truth,

showed me women’s faces hurrying by

that cried to me: “You will die, you will die.”

Then I saw many fearful things,

in the empty dream that I had entered:

I seemed to be in a place I did not know,

and saw women going by in the street, dishevelled,

some full of tears, and some giving cries,

that flew like fires of sadness.

Then it seemed to me little by little

the sun darkened and the stars appeared,

and wept one to another:

the birds fell as they flew through the air,

and the earth trembled:

And a man appeared pale and hoarse,

saying to me: “What? Have you not heard the news?

Your lady is dead, who was so lovely.”

I lifted my eyes, bathed in tears,

and saw, what seemed like manna raining,

angels returning to the sky,

and a little cloud went before them,

behind which they all cried: “Hosanna”:

and if they had said more, I would tell you.

Then Amor said: “I will hide nothing from you:

come and see our lady, lying”.

This fantastic dream

carried me to see the dead lady:

and when I was brought there,

I saw that ladies covered her with a veil:

and she had a look of true humility,

that it seemed as if she said: “I am at peace.”

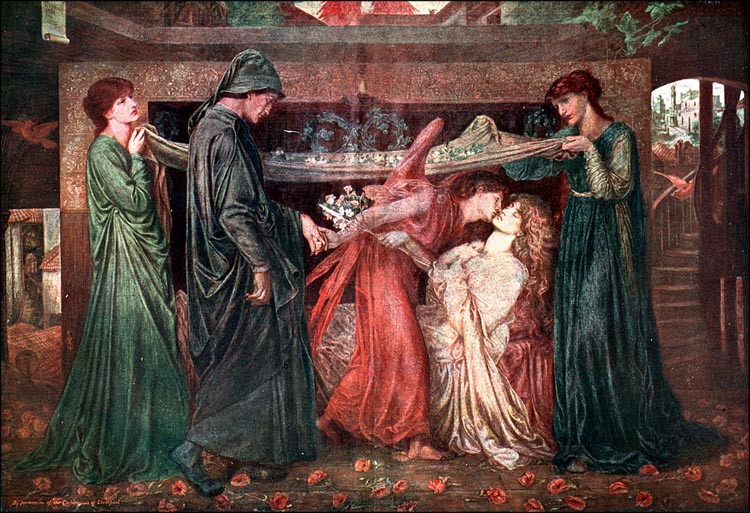

‘Dante's Dream at the Time of the Death of Beatrice’ - Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882)

I became so humble in my grief,

seeing such humility there in her,

that I said: “Death, I hold you so sweet:

now you will be a gentle thing,

since you have entered in my lady,

and will possess pity and not disdain.

See how I so much long to be

yours, that I resemble you in feature.

Come to me, as the heart begs you.”

Then I departed, all the mourning done:

and when I was alone,

I said, gazing to the highest regions:

“Blessed is he, lovely soul, who sees you!”

Then you woke me, out of mercy.’

This canzone has two parts: in the first I say, speaking to an unknown person, how I was roused from a vain fantasy, by certain ladies, and how promised to tell them of it: in the second I say what i told them. The second part begins with: ‘Mentr´io pensava: Lying there, thinking’. The first part is divided in two: in the first part I say what certain ladies, and one of them especially, said and did because of my fantasy, and before I had returned to a normal condition: in the second part I say what they said to me when I had left that delirium: and that part begins with: ‘Era la voce mia: My voice was’

Next where I say: ‘Mentr´io pensava’ I say how I told them that dream. And in this there are two parts: in the first I relate my dream in order: in the second, saying at what moment they woke me, I hint at my gratitude to them: and this part begins with: ‘Voi mi chimaste: Then you woke me’.

XXIV His sonetto to Guido Cavalcanti

XXIV His sonetto to Guido Cavalcanti

After this vain imagining, it happened one day that, while I was sitting somewhere thinking, I felt a tremor beginning in my heart, as if I was in the presence of that lady. Then I say that a vision of Love came to me: and he seemed to come to me from the place where my lady lived, and it seemed to me that he said in my heart, joyfully: ‘Think blessedly of the day that I seized on you, because you ought to do so.’ And indeed my heart seemed so joyful, that it did not seem to be my heart, in this new state.

And not long after these words, that my heart spoke to me with the tongue of Love, I saw a gentle lady coming towards me, who was famous for her beauty, and who had long been my best friend’s lady. And the name of this lady was Giovanna, except that because of her beauty, as others believe, she was also named Primavera (Spring, the first greenness): and called so. And after her, as I gazed, I saw the miraculous Beatrice come by.

These ladies passed near me one after the other, and it seemed that Love spoke in my heart, and said: ‘The first is named Primavera, only because of what happened today: since I inspired the originator of the name to call her Primavera, she who first passes (prima verrà), on the day that Beatrice shows herself to the imagination of her faithful one. And if you also consider her first name, it also says ‘she who first passes’, since Giovanna comes from Giovanni (John) who preceded the true light, saying: “Ego vox clamantis in deserto: parate viam Domini: I am a voice crying in the wilderness: prepare the way of the Lord”’.

And after that it seemed to me that he said these words also: ‘Anyone who considers carefully would call Beatrice Love for the great similarity she has to me.’ Later, reflecting, I decided to write to my best friend in verse (withholding certain words it seemed best to withhold), believing that his heart still marvelled at the beauty of this gentle Primavera: and I wrote this sonetto, which begins: ‘Io mi senti´ svegliar.’

I felt a stirring in my heart

of a spirit of love which slept:

and then I saw Love coming from afar

so happy, that I scarcely recognised him,

saying : ‘Now think only to honour me’:

and he was smiling at every word.

And while my lord was standing by me,

I, gazing at the road that he had come,

saw lady Vanna and lady Bice

approaching the place where I was,

one miracle behind the other:

and as my mind repeats it to me,

Amor said to me: ‘That lady is Primavera,

and this lady has Love’s name, so resembling me.’

This sonetto has a number of parts: the first of them says how I felt a familiar tremor stirring in my heart, and how Love seemed to appear to me from afar, happy and in my heart: the second says how it seemed to me that love spoke to me in my heart, and how he looked to me: the third says how, when he had been with me a while, I saw and heard certain things. The second part begins with: ‘dicendo: “Or pensa”: saying: “ Now think”’: the third with: ‘E poco stando: And while’. The third part is divided in two: in the first I say what I saw: in the second I say what I heard. The second begins with: ‘Amor mi disse: Amor said to me.’

XXV His justification of his personification of Love

XXV His justification of his personification of Love

It might be that a person might object, one worthy of raising an objection, and their objection might be this, that I speak of Love as though it were a thing in itself, and not only an intelligent subject, but a bodily substance: which, demonstrably, is false: since Love is not in itself a substance, but an accident of substance.

And that I speak of him as if he were corporeal, moreover as though he were a man, is apparent from these three things I say of him. I say that I saw him approaching: and since to approach implies local movement, and local movement per se, following the Philosopher, exists only in a body, it is apparent that I make Love corporeal.

I also say of him that he smiles, and that he speaks: things which properly belong to man, and especially laughter: and therefore it is apparent that I make him human. To make this clear, in a way that is good for the present matter, if should first be understood that in ancient times there was no poetry of Love in the common tongue, but there was Love poetry by certain poets in the Latin tongue: amongst us, I say, and perhaps it happened amongst other peoples, and still happens, as in Greece, only literary, not vernacular poets treated of these things.

Not many years have passed since the first of these vernacular poets appeared: since to speak in rhyme in the common tongue is much the same as to speak in Latin verse, paying due regard to metre. And a sign that it is only a short time is that, if we choose to search in the language of ocand that of si, we will not find anything earlier than a hundred and fifty years ago.

And the reason why several crude rhymesters were famous for knowing how to write is that they were almost the first to write in the language of si. And the first who began to write as a poet of the common tongue was moved to do so because he wished to make his words understandable by a lady to whom verse in Latin was hard to understand. And this argues against those who rhyme on other matters than love, because it is a fact that this mode of speaking was first invented in order to speak of love.

From this it follows that since greater license is given to poets than prose writers, and since those who speak in rhyme are no other than the vernacular poets, it is apt and reasonable that greater license should be granted to them to speak than to other speakers in the common tongue: so that if any figure of speech or rhetorical flourish is conceded to the poets, it is conceded to the rhymesters. So if we see that the poets have spoken of inanimate things as if they had sense and reason, and made them talk to each other, and not just with real but with imaginary things, having things which do not exist speak, and many accidental things speak, as if they were substantial and human, it is fitting for writers of rhymes to do the same, but not without reason, and with a reason that can later be shown in prose.

That the poets have spoken like this is can be evidenced by Virgil, who says that Juno, who was an enemy of the Trojans, spoke to Aeolus, god of the winds, in the first book of the Aeneid: ‘Aeole, namque tibi: Aeolus, it was you’, and that the god replied to her with: Tuus, o regina, quid optes, explorare labor: mihi jussa capessere fas est: It is for you, o queen, to decide what our labours are to achieve: it is my duty to carry out your orders’. In the same poet he makes an inanimate thing (Apollo’s oracle) talk with animate things, in the third book of the Aeneid, with: ‘Dardanidae duri: You rough Trojans’.

In Lucan an animate thing talks with an inanimate thing, with: ‘Multum. Roma, tamen debes civilibus armis: Rome, you have greatly benefited from the civil wars.’

In Horace a man speaks to his own learning as if to another person: and not only are they Horace’s words, but he gives them as if quoting the style of goodly Homer, in his Poetics saying: ‘Dic mihi, Musa, virum: Tell me, Muse, about the man.’

In Ovid, Love speaks as if it were a person, at the start of his book titled De Remediis Amoris: Of the Remedies for Love, where he says: ‘Bella mihi, video, bella parantur, ait: Some fine things I see, some fine things are being prepared, he said.’

These examples should serve to as explanation to anyone who has objections concerning any part of my little book. And in case any ignorant person should assume too much, I will add that the poets did not write in this mode without good reason, nor should those who compose in rhyme, if they cannot justify what they are saying, since it would be shameful if someone composing in rhyme put in a figure of speech or a rhetorical flourish, and then, being asked, could not rid his words of such ornamentation so as to show the true meaning. My best friend and I know many who compose rhymes in this foolish manner.

XXVI His further praise of Beatrice

XXVI His further praise of Beatrice

This most graceful lady, of whom I have spoken in preceding words, found so much favour among people, that when she passed along the street, they ran to catch sight of her: which filled me with marvellous joy. And when she was near anyone, such purity filled his heart that he did not dare to raise his eyes, or to respond to her greeting: and of this, having experienced it, many might give witness to those who did not credit it.

She went crowned and clothed with humility, showing no arrogance because of what she saw or heard. Many, when she passed, said: ‘She is no woman, but one of the most beautiful of Heaven’s angels.’ And others said: ‘She is a marvel: how blessed is the Lord, who can create such miracles!’

I say that she appeared so gentle and so full of all that was pleasing, that those who gazed at her comprehended in themselves a pure and soothing sweetness, that they could not describe: nor was there anyone who could gaze at her without immediately sighing.

These, and more marvellous things, arose from her virtues: so that thinking of it, wanting to repeat my style of praising her, I decided to write verse in which I would reveal her miraculous and excellent effect, so that not only those who could physically see her, but others might know of her what words can show. Then I wrote this sonetto, which begins: ‘Tanto gentile’.

So gentle and so pure appears

my lady when she greets others,

that every tongue trembles and is mute,

and their eyes do not dare gaze at her.

She goes by, aware of their praise,

benignly dressed in humility:

and seems as if she were a thing come

from Heaven to Earth to show a miracle.

She shows herself so pleasing to those who gaze,

through the eyes she sends a sweetness to the heart,

that no one can understand who does not know it:

and from her lips there comes

a sweet spirit full of love,

that goes saying to the soul: ‘Sigh.’

This sonetto is so simple to understand, from what is said above, that it needs no division: and so, leaving it, I say that my lady came into such grace that not only was she honoured and praised, but through her many were also honoured and praised. Then, seeing this, and wanting to reveal it to those who had not seen it, I decided to write further verses that would make it known: and I then wrote this next sonetto that begins: ‘Vede perfettamente onne salute’

They have seen perfection of all welcome

who see my lady among the other ladies:

those who go by with her are moved

to render thanks to God for lovely grace.

Her beauty is of such virtue,

that no envy can arise from it,

but makes them go clothed with

nobility, with love and with loyalty.

The sight of her makes all humble:

and does not only make her appear pleasing,

but all receive honour through her.

And she is so gentle in her effect,

that no one can recall her to mind.

who does not sigh in sweetness of love.

This sonetto has three parts: in the first I say among which people that lady seemed most miraculous: in the second I say how gracious was her company: in the third I say what things her power brought about in others. The second part begins with: ‘quelle que vano: those who go by’: the third with: ‘E sua bieltate: Her beauty is’.

This last part is divided in three: in the first I say what she brought about in ladies, that is through their own selves: in the second I say what she brought about in them in the eyes of others: in the third I say how not only in the ladies, but in everyone, and not only in her presence but in remembrance of her, she worked miraculously. The second begins with: ‘La vista sua: The sight of her’: and the third with: ‘Ed è ne li atti: And she is so’.

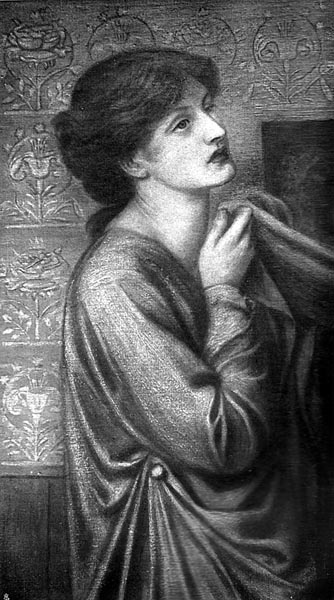

‘The Pious Lady on the Left (Study for Dante's Dream)’ - Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882)

XXVII Her effect on Dante

XXVII Her effect on Dante

After this I began to think one day about what I had written of my lady, that is in the two preceding sonetti: and realising in my thoughts, that I had not written about what she was bringing about in me at the present moment, it appeared to me that I had spoken inadequately. And so I decided to write verse in which I would say how I seemed to be sensitive to her effect, and how her virtue affected me: and not believing that I could say it in a brief sonetto, I then started a canzone, which begins: ‘Sì lungiamente’.

So long has Love held power over me

and accustomed me to his lordship,

that as he seemed harsh to me at first,

so now he seems sweet in my heart.

And so when he takes away my courage,

and my spirits seem to fly away,

then I feel throughout my soul

such sweetness that my face pales,

and then Love holds such power over me,

that he makes my spirits go speaking,

and always calling on

my lady to grant me greater welcome.

That happens to me whenever I see her,

and is so humbling, no one can understand.

XXVIII What he will say concerning the death of Beatrice

XXVIII What he will say concerning the death of Beatrice

‘Quomodo sedet sola civitas plena populo! facta est quasi vidua domina gentium: How solitary lies the city filled with people! it has become as a woman widowed, in the world.’

I was still composing this canzone and had completed the stanza given previously, when the Lord of Justice called this most gentle one to glory under the sign of that queen, the Blessed Virgin Mary, whose name was held in greatest reverence in the words of this blessed Beatrice.

And although it might perhaps be right at present to say something of her departure from us, it is not my intention to say anything for three reasons: the first is that it is not part of my present theme, if one considers the introduction that opens this little book: the second is this, even if it were part of the present theme, my tongue is not sufficiently knowledgeable to treat of it as it should be treated: the third is this, even if one or the other were not the case, it is not fitting for me to treat of it, because treating of it would require me to praise myself, which is the most reprehensible thing one can do: and therefore I leave it to be treated of by another commentator.

However, since the number nine has appeared a number of times in my previous words, and it appears that this is not without meaning, and it seems that in her departure this number played a large part, it is fitting to say something as it seems necessary to my theme. So I will first say what part it played in her departure, and then I will give some reasons why this number was so closely tied to her.

XXIX The number nine

XXIX The number nine

I say that, following Arabic usage, her most noble spirit departed from us in the first hour (6am) of the ninth day of the month (the nineteenth): and following Syrian usage she departed from us in the ninth month of the year (June), because their first month is First Tixryn which is October to us: and following our usage she departed from us in that year of our era, that is of the years of Our Lord, in which the perfect number (ten) had been completed nine times in the century in which she lived in this world, and she was a Christian of the thirteenth century (1290).

As to why this number was so closely tied to her, this might provide a reason: since, following Ptolemy and following Christian truth, there are nine revolving heavens, and following common astrological opinion these heavens must affect what is beneath them according to their aspects together, this number was closely linked to her in order to show that at her birth all the nine revolving heavens were in perfect accord.

This is one reason: but thinking more subtly, and following infallible truth, this number was she, herself: I say it symbolically, and I will explain it so. The number three is the root of nine, because, without any other number, of itself it creates nine, as can be clearly seen in that three times three is nine.

Therefore if three is of itself the only maker of nine, and the only maker from itself of miracles is threefold, that is the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, who are three and one, that lady was accompanied by this number nine to reveal that she was a nine, that is a miracle, of which the root, that is of the miracle, is solely the miraculous Trinity.

Perhaps a more subtle person could find in it a more subtle reason: but this is the one that I see, and that pleases me most.

XXX His letter to the Rulers

XXX His letter to the Rulers

After she had departed this life, the whole city was left as though widowed, shorn of all dignity: so that I, still weeping in the desolate city, wrote to the rulers of the Earth something of its condition, taking the beginning from the Prophet Jeremiah which says: ‘Quomodo sedet sola civitas: How solitary lies the city.’

And I say this so that no one might wonder why I have written it previously, almost as an introduction to the new theme that follows it. And if anyone wants to criticise me for this, that I do not write the words that followed that quotation, I will excuse myself in that I intended from the first to write nothing except in the common tongue: so that, since the speech that follows that which is quoted is all in Latin, it would be against my intentions to write it. And likewise it is the intention of my best friend for whom I write this, also, that I should write it only in the common tongue.

Index to the First Lines of the Poems

Index to the First Lines of the Poems

- In her eyes my lady bears Love,

- You who bear a humble look,

- Are you him that so often spoke

- A lady, youthful and piteous,

- I felt a stirring in my heart

- So gentle and so pure appears

- They have seen perfection of all welcome

- So long has Love held power over me