La Vita Nuova

‘The New Life’ of Dante Alighieri

Sections XI to XX

Listen to audio-book edition sample:

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

In Memory of Jean (1922-2001)

Contents

- XI The effects on him of her greeting

- XII He dreams of the young man dressed in white

- XIII The war of conflicting thoughts

- XIV Dante faints at the marriage scene

- XV The reason why he continues to try and see her

- XVI His state on being in love

- XVII He ceases to address her in verse

- XVIII He takes praise of Beatrice as his new theme

- XIX He writes a first canzone in praise of Beatrice

- XX He is requested to say what Love is

- Index to the First Lines of the Poems

XI The effects on him of her greeting

XI The effects on him of her greeting

I say that when she appeared, in whatever place, by the hope embodied in that marvellous greeting, for me no enemy remained, in fact I shone with a flame of charity that made me grant pardon to whoever had offended me: and if anyone had then asked me anything my reply would only have been: ‘Love’, with an aspect full of humility.

And when she was on the point of greeting me, a spirit of love, suppressing all the other spirits of the senses, made the weak spirits of vision scatter, and said to them: ‘Go and honour your lady’, and it remained so in their place. And whoever had a desire to know Love, could have done so by watching the trembling of my eyes.

And when this most graceful one made things well by greeting me, it was not that Love so came between us that it could cloud in me the unbearable blessedness, but almost by overpowering sweetness it came to be such that my body, which was then wholly under its sway, often moved like a heavy and inanimate object. So it is clearly seen that all my blessedness, which often surpassed and overfilled my capacity, lay in her greeting.

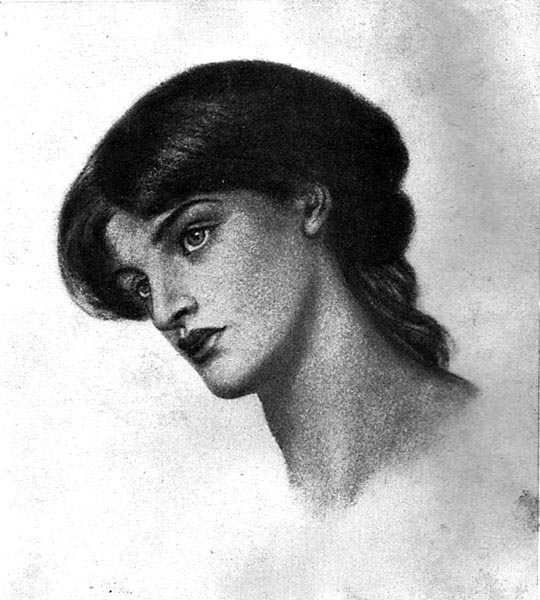

‘The Salutation of Beatrice (on Earth and in Heaven)’ - Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882)

XII He dreams of the young man dressed in white

XII He dreams of the young man dressed in white

Now, returning to the subject, I say that after my blessedness was denied me, I met with such sadness that leaving the crowd I went to a lonely place to bathe the ground with bitter tears. And when this weeping had relieved me a little I shut myself in my room where I could grieve without being heard: and there, begging pity of the lady of courtesy, and saying: ‘Love, help your faithful one’, I fell asleep weeping like a beaten child.

It happened that about the middle of my sleep I seemed to see a young man dressed in the whitest of white sitting next to me in my room, and, deeply thoughtful in his aspect, he gazed at me where I lay: and when he had gazed a while it seemed to me he called to me sighing, and said these words: ‘Fili mi, tempus est ut praetermittantur simulacra nostra: My son, it is time to set aside our pretences.’ Then it seemed to me that I knew him, because he called to me as he had many times called to me in my dreams: and regarding him it seemed to me that he was weeping piteously, and seemed to be waiting for some word from me: so that, taking heart, I began to speak to him so: ‘Lord of nobility, why do you weep?’ And he said these words to me: ‘Ego tanquam centrum circuli, cui simili modo se habent circumferentiae partes: tu autem non sic: I am as the centre of a circle, to which the parts of the circumference have a similar relation: you however are not so.’

Then, thinking about his words, it seemed to me he had spoken very obscurely: so that I forced myself to speak and said these words: ‘What is it, lord, that you say to me so obscurely?’ And he replied to me in the common tongue: ‘Do not demand more than is helpful to you.’ And so I began then to discuss the greeting which had been denied me, and I asked the reason: to which the reply came from him to me: ‘Our Beatrice heard from certain people, speaking of you, that the lady whom I named to you on the road of sighs, has met with some discourtesy from you: and so this most graceful one, who is the opposite of all discourtesy, did not deign to greet your person, fearing you might show discourtesy.

Since it is a fact that in truth your secret is partly known to her through lengthy observation, I wish you to say certain words in verse in which you will declare the power I have had over you through her, and how you were hers, wholly, from your childhood. And for that demand testimony of him who knows, and say how you beg him to tell her of it: and I, who am he, will tell her freely: and in this way she will come to know your will, knowing which she will unpick the words of the informants. Make those words act as a go-between so that you do not speak to her directly: which is not appropriate: and do not send them anywhere without me, where they might be heard by her, but have them adorned by sweet music, in which I can reside at all the times when I am needed.’

And saying these words he vanished, and my dream was broken. When I reflected on it, I found that this vision appeared to me in the ninth hour of the day: and before I went out of my room I decided to make a ballata in which I would carry out what my lord had commanded me: and later I made this ballata, that begins: ‘Ballata, i´ voi’.

Ballad, I would have you find Amor,

and go with him before my Lady,

so that my cause, that you sing,

my lord can speak of with her.

You go, ballad, so courteously,

that without companions

you may dare to go anywhere:

but if you wish to travel safely,

first find Amor,

since maybe it is not wise to go without him:

for she who is the one who must hear you,

if it is as I think, is truly angered with me:

if you are not accompanied by him,

you will be taken lightly, with dishonour.

With sweet sounds, when you are with her,

begin these words,

after you have sought her pity:

‘My Lady, he who sent me to you,

wishes, if it please you,

that if he has an excuse, I may present it.

Love is one, who through your beauty,

will make him, if you wish, change his aspect:

so if it made him gaze at another,

think you, it did not change his heart.’

Say to her: ‘My Lady, his heart is fixed

with so firm a faith,

that all his thought is set on serving you:

he was yours at first, and could not waver.’

If she does not believe you,

tell her to ask Amor, who knows the truth:

and at the end make a humble prayer,

that if it displeases her to pardon him,

let her send word, and order me to die,

and her servant will show true obedience.

And say to him, who is the key to pity,

before you take your leave,

that he knowing it plead my cause well:

‘By the grace of my sweet notes

stay you there with her,

and for your servant plead, as you will,

and if she pardon him through your prayer,

let her show an aspect of sweet peace.’

My gentle ballad, if you please,

choose the moment that will bring you honour.

This ballata is divided into three parts: in the first part I say where it should journey, and I encourage it to travel more safely, and I say what company it should be in it if wishes to go safely and without any danger: in the second I say what it is it needs to make known: in the third I license it to go when it wishes, recommending its movements to the embrace of fortune. The second part begins with: ‘Con dolze sono: With sweet sounds’: the third with: ‘Gentil ballata: Gentle ballad.’

Someone might raise an objection against me and say that it is not known whom I address in the second person, since the ballata is no more than the words that I wrote: and so I say that I intend to resolve this doubt and clarify it later in this little book regarding an even more difficult passage: and then let him who doubts understand, or let him who wishes to object do so at that time.

XIII The war of conflicting thoughts

XIII The war of conflicting thoughts

After the vision above, having already written the words that Love had commanded me to write, many diverse thoughts began to contend and struggle within me, each one almost unanswerable: amongst these thoughts four seemed most to disturb my peace of mind. One of them was this: Love’s ruler-ship is good because he draws the intent of his faithful away from all evil things. The next was this: Love’s ruler-ship is not good because the more faith his faithful demonstrate towards him the heavier and more grievous are the moments he must endure. The third was this: the name of love is so sweet to hear that it seems impossible to me that his true effects can be anything other than sweet, since it is known that names derive from the things named, as it is written: ‘Nomina sunt consequentia rerum: Names are consequent on things.’ The fourth was this: the Lady, for whom love constrains you so, is not like other ladies whose hearts are easily swayed.’

And each of these so contended in me, that I became like he who does not know which road to choose for his journey, and who wants to go and does not know which way to go: and if I thought to try and find the common path among them, in which all of them might meet, it was a way most inimical to me, it was to call on and throw myself into the arms of Pity. And remaining in this state, I felt the desire to write words of verse: and then I wrote this sonetto, which begins: ‘Tutti li mei penser’.

Every one of my thoughts speaks of Love:

and they have in them such great variance,

that one makes me wish for his ruler-ship,

another claims that his worth is nothing,

another by hoping brings me sweetness,

another makes me weep constantly,

and they only agree in asking pity,

trembling with the fear that is in the heart.

Therefore I do not know which theme to choose:

and wish to speak, and know not what to say:

so that I find myself in a lover’s maze!

And if I wish to make them all accord,

I am forced to call on my enemy,

my lady Pity, and ask her to defend me.

This sonetto can be divided into four parts: in the first I speak and declare that all my thoughts are of Love: in the second I say that they are diverse, and I describe their diversity: in the third I say in what way they seem in accord: in the fourth I say that wishing to speak of Love, I do not know which to choose as my theme, and if I wish to choose them all I am forced to call on my enemy, my lady Pity: and I say ‘my lady’ as a disdainful mode of speech. The second part begins with: ‘e hanno in lor: and they have in them’: the third with: ‘e sol s’accordano: and they only agree’: the fourth with: ‘Ond’io non so: Therefore I do not know’.

XIV Dante faints at the marriage scene

XIV Dante faints at the marriage scene

After the war of divergent thoughts it chanced that this most graceful one came where many gentle ladies were gathered: to which place I was led by a friend, thinking to give me great delight, by showing me the place where so many ladies were displaying their beauty. So I, scarcely knowing where I was being taken, and trusting in the person who had conducted his friend to the extremity of life, said to him: ‘Why have we come to these ladies?’ Then he said to me: ‘To allow them to be worthily served.’

And the truth is that they were gathered in the company of a gentle lady who had been wedded that day: and so, following the custom of the city, it was necessary for them to keep her company the first time she sat at table in her husband’s house.

So I, believing that it would please this friend, decided to stay and attend upon the ladies in her company. And at the moment of my decision I seemed to feel a strange tremor start under my left breast and spread suddenly through all the parts of my body. Then I say I quietly leaned back against a fresco that ran round the walls of the house: and fearing lest others might be aware of my trembling, I raised my eyes, and gazing at the ladies, I saw the most graceful Beatrice among them.

Then my spirits were so scattered by the force that Love gained finding himself so near to the most graceful lady, that only the spirits of sight remained alive: and even they remained lost to their visual organs since Love wished to stand in their noblest of places to see the miraculous lady. And though I was other than at first, I grieved greatly for these little spirits who were lamenting loudly and saying: ‘If he had not shot us out of our place, we could have stayed to see the marvel of this lady as all our other parts have stayed.’

I say that many of those ladies aware of my transfiguration, then began to wonder, and then speak mockingly of me with this most gentle one: at which my friend, innocent of this in all good faith, took me by the hand, and led me from the sight of those ladies, then asked what troubled me.

Then, somewhat rested, and my mortal spirits revived, and those scattered returned to their possession, I said these words to that friend: ‘I have set foot in that region of life where it is not possible to go with any more intention of returning.’ And parting from him I returned to my chamber of tears: in which, weeping and shame-faced, I said to myself: ‘If my lady knew of my condition, I do not believe she would mock my person, in fact I believe she would inwardly feel much pity.’

And whilst in this state of weeping, I decided to speak words in which, speaking to her, I would explain the cause of my transfiguration, and say that I well knew that it was not known, and that, if it were known I believed that pity would be stirred in others: and I decided to speak desiring that it might come by chance to her ears. And then I wrote this sonetto, which begins: ‘Con l’altre donne’.

With the other ladies you mock my looks,

and do not think, lady, why it is

that I am seized by such a strange appearance

when I gaze upon your beauty.

If you knew, Pity could not be

held from me in the usual way,

that Amor, when he finds me so close to you,

gains so in boldness and temerity,

that he sets upon my frightened spirits,

and some he kills, and some he scatters,

till only he remains to gaze at you:

so that I change to another form,

but not so that I cannot then still hear

the wail of those tormented scattered ones.

‘The Pious Lady on the Right (Study for Dante's Dream)’ - Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882)

I will not divide this sonetto into its parts, since the division is only made to clarify the sense of the thing so divided: so as this thing is such that in the telling the logic is clear enough, it does not need dividing. It is true that among the words in which the logic of this sonetto is shown, are written some obscure words, those where I say that Love kills all my spirits, and those of sight remain alive, except they flee their organs of vision. And this obscurity is impossible to explain to one who is not in a similar manner one of Love’s faithful: and to those who are it is obvious what clarifies the obscure words: and so it is no use for me to clarify that obscurity, since my words of clarification would be pointless, and indeed superfluous.

XV The reason why he continues to try and see her

XV The reason why he continues to try and see her

After the strange transfiguration I had an insistent thought, one that scarcely left me, indeed it continually seized me, and it reasoned with me like this: ‘Since you acquire this shameful aspect when you are near this lady, why do you try to catch sight of her? Suppose you were asked that by her: what answer could you give in reply, taking it that all your wits were free when you replied to her?’

And another humble thought echoed this, and said: ‘If I did not lose my wits, and felt free enough to be able to reply, I would tell her that as soon as I imagine her miraculous beauty, so quickly the desire to see her seizes me, which is so powerful, that it slays and destroys whatever in my memory could rise against it: and so my past sufferings do not restrain me from trying to catch sight of her.’

So, moved by these thoughts, I decided to speak certain words, in which I might excuse myself for this reprehensible thought, explaining also what happened to me near her: and I wrote this sonetto, which begins: ‘Ciò che m’incontra’.

All I encounter in my mind dies,

when I come to gaze on you, sweet joy:

and when I am near you, I feel Love

who says: ‘Run, if you care about dying’.

The face shows the colour of the heart,

that, fainting, leans for support:

and in the vast intoxicating tremor

the stones beneath me cry: Death, death.

They commit a sin who see me then,

if they do not comfort my bewildered soul,

if only by showing that they care for me,

through pity, which your mocking killed,

that is descried in the dying vision

of eyes that have wished for death.

This sonettois divided in two parts: in the first I give the reason why I do not hold myself from going near to this lady: in the second I say what happens to me from going near her: and this second part begins with: ‘e quandi´o vi son presso: and when I am near you.’ And also this second part can be divided in five, according to the five differing subjects: in the first I say what Love, counselled by reason, says to me when I am near her: in the second I show the state of my heart revealed in my face: in the third I say how I come to lose all confidence: in the fourth I say what sin they commit who do not show pity for me, since it would be some comfort to me: in the last I say why others should have pity, and that is because of the pitiful look that fills my eyes: this pitiful look is destroyed, that is does not appear to others, by this lady’s mockery, which draws to similar action those who perhaps might well see that piteousness.

The second part begins with: ‘Lo viso mostra: the face shows’: the third with: ‘e per la ebrietà: and in the vast intoxicating’: the fourth with: ‘Peccato face: They commit a sin’: the fifth: ‘per la pietà: through pity’.

XVI His state on being in love

XVI His state on being in love

After I had written this sonetto, I had the will to write yet another in which I would say four more things about my state, which it seemed to me I had not yet made clear. The first of these is that many times I was troubled, when my memory stirred my fancy to imagine what Love was doing to me. The second is that Love often attacked me so savagely that nothing was left alive in me except thoughts that spoke of my lady: the third is that when the war of Love battled in me like this I was moved all pale as I was to see this lady, believing that sight of her would defend me in this war, forgetting what happened to me when I approached such gentleness. The fourth is how that sight of her not only failed to defend me but finally discomforted what little life I had. And so I wrote this sonetto, which begins: ‘Spesse fiate’.

Often it is brought home to my mind

the dark quality that Love gives me,

and pity moves me, so that frequently

I say: ‘Alas! is anyone so afflicted?’:

since Amor assails me suddenly,

so that life almost abandons me:

only a single spirit stays with me,

and that remains because it speaks of you.

I renew my strength, because I wish for help,

and pale like this, all my courage drained,

come to you, believing it will save me:

and if I lift my eyes to gaze at you

my heart begins to tremble so,

that from my pulse the soul departs.

This sonetto is divided into four parts, in accord with the four things spoken of within it: and since they are explained above, I will not comment except to distinguish the parts by their beginnings: so I say that the second part begins with: ‘ch’Amor: since Amor’: the third with: ‘Poscia mi sforzo: I renew my strength’: the fourth with: ‘e se io levo: and if I lift’.

XVII He ceases to address her in verse

XVII He ceases to address her in verse

When I had written these three sonetti, in which I spoke to that lady, since they told almost everything about my state, I believed I should be silent and say no more, since it seemed to me I had explained sufficiently about myself, although, silent from then on in speaking to her, I was compelled to adopt new material, nobler than before. And since the occasion for the new material is pleasant to hear, I will speak of it, as briefly as I can.

XVIII He takes praise of Beatrice as his new theme

XVIII He takes praise of Beatrice as his new theme

As it was a fact that many people had guessed the secret of my heart from my face, certain ladies, gathered together in order to take delight in each other’s company, well knew my heart, since each of them was there often when I was discomforted: and I passing near them, as if led by fortune, was called to by one of these gentle ladies.

The lady who had called to me was a lady of very sweet speech: so that when I had reached them, and saw clearly that my most graceful lady was not with them, I was reassured enough to greet them, and ask their pleasure. The ladies were many, among whom certain were laughing amongst themselves: others were gazing at me waiting to hear what I should say: others again were talking among themselves.

Of these one, turning her eyes towards me and calling me by name, said these words: ‘What is the point of your love for your lady, since you cannot endure her presence? Tell us, since the point of such love must surely be a very strange one.’ And when she had spoken these words, not only she, but all the others, seemed by their faces to wait for my reply.

Then I spoke these words to her: ‘My lady, the point of my love was once that lady’s greeting, she whom perhaps you know, and in that rested the blessedness, which was the point of all my desires. But since she was pleased to deny it me, my lord Love, in his mercy, has set all my blessedness in that which I cannot lose.’

Then those ladies began to speak amongst themselves: and as we sometimes see rain falling mixed with beautiful snowflakes, so I seemed to hear their words emerge mixed with sighs. And when they had spoken a while among themselves, that lady who had spoken to me at first still said to me these words: ‘We beg you to tell us, where is your blessedness.’

And I, replying to them, said this: ‘In those words that praise my lady.’ Then she who had spoken to me replied: ‘If you were speaking truth to us, those words you have written to explain your condition would have been composed with a different intent.’

So I, thinking about those words, almost ashamed, parted from them, and went along saying to myself: ‘Since there is such blessedness in those words that praise my lady, why have I spoken in another manner?’ And so I decided to take as the theme of my words forever more those which sung the praises of that very graceful one: and thinking about it deeply, it seemed to me I had taken on a theme too high for me, so that I dared not begin: and I remained for several days with the desire to write and in fear of beginning.

XIX He writes a first canzone in praise of Beatrice

XIX He writes a first canzone in praise of Beatrice

After this while I was walking along a path by which a stream of clearest water ran, I felt so strong a will to write that I began to think of the form I should use: and I thought that in speaking of her it would not be right if I composed without speaking to ladies in the second person, and not to all ladies, but only to those who are gentle and not merely feminine.

Then I say that my tongue spoke as if it moved by itself, and said: ‘Ladies who have knowledge of love.’ These words I stored in my mind with great delight, thinking to use them for my opening: so then, returning to the city, thinking for several days, I began a canzone with that opening, ordered in a way that will be seen in its divisions. The canzone begins: ‘Donne ch’avete’.

Ladies who have knowledge of love,

I wish to speak with you about my lady,

not because I think to end her praises,

but speaking so that I can ease my mind.

I say that thinking of her worth,

Amor makes me feel such sweetness,

that if did not then lose courage,

speaking, I would make all men in love.

And I would not speak so highly,

that I succumb to vile timidity:

but treat of the state of gentleness,

in respect of her, lightly, with you,

loving ladies and young ladies,

that is not to be spoken of to others.

An angel sings in the divine mind

and says: ‘Lord, in the world is seen

a miracle in action that proceeds

from a spirit that shines up here.’

The heavens that have no other defect

but lack of her, pray to their Lord,

and every saint cries out mercy.

Pity alone takes our part,

so that God speaks of her, and means my lady:

‘My Delights, now suffer it in peace

that at my pleasure she, your hope, remains

there, where one is who waits to lose her,

and will say in the Inferno: “Ill-born ones,

I have seen the hope of the blessed.”’

My lady is desired by highest Heaven:

now I would have you know of her virtue.

I say, you who would appear a gentle lady

go with her, since when she goes by

Love strikes a chill in evil hearts,

so that all their thoughts freeze and perish:

and any man who suffers to stay and see her

becomes a noble soul, or else he dies.

And when she finds any who might be worthy

to look at her, he proves her virtue,

which comes to him, given, in greeting

and if he is humble, erases all offense.

Still greater grace God has granted her

since he cannot end badly who speaks with her.

Amor says of her: ‘This mortal thing,

how can it be so pure and adorned?’

Then he looks at her and swears to himself

that God’s intent was to make something rare.

She has the colour of pearl, in form such as

is fitting to a lady, not in excess:

she is the greatest good nature can create:

beauty is proven by her example.

From her eyes, as she moves them,

issue spirits ablaze with love,

which pierce the eyes of those who gaze on her then,

and pass within so each one finds the heart:

you will see Love pictured in her face,

there where no man may fixedly gaze.

Canzone, I know that you will go speaking

to many ladies, when I have sent you onwards.

Now I have made you, since I have raised you

to be Love’s daughter, young and simple,

to those I have sent you, say, praying:

‘Show me the way to go, since I am sent

to her of whom the praise is my adornment.’

And if you do not wish to go in vain,

do not rest where there are evil people:

try, if you can so do, to be revealed

only to ladies or some courteous man,

who will lead you there by the quickest way.

You will find Amor will be with her:

recommend me to him as you should.

‘Beatrice (Study for Dante’s Dream)’ - Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882)

This canzone, so that it may be better understood, I will divide more intricately than the other poems above. And so I will first define three parts: the first part is a prelude to the following words: the second is the subject I treat of: the third is like a servant to the preceding words. The second begins with: ‘Angelo clama: An angel sings’: the third with: ‘Canzone, io so che: Canzone I know that’.

The first part is divided in four: in the first I say to whom I wish to speak about my lady, and why I wish to speak: in the second I say what state I seem to be in when I think of her virtue, and what I would speak of if I did not lose courage: in the third I say how I believe I must speak of her in order not to be held back by diffidence. in the fourth, restating to whom I intend to speak, I give the reason why I speak to them. The second begins with: ‘Io dico: I say’: the third with: ‘E io non vo´ parlar: And I would not speak ’: the fourth: ‘donne e donzelle: ladies and young ladies’.

Next where I say: ‘Angelo clama’ I begin to treat of this lady. And I divide this part in two: in the first I say what is known of her in Heaven: in the second I say what is known of her on Earth, with: ‘Madonna è disiata: My lady is desired’. This second part is divided in two: so that in the first I speak of her regarding the nobility of her spirit, saying something of her active virtues that proceed from her spirit: in the second I speak of her regarding the nobility of her body, saying something about her beauty, with: ‘Dice de lei Amor: Amor says of her’. This second part is divided in two: as in the first I speak of certain beauties which belong to her whole person, in the second I speak of certain beauties which belong to distinct parts of her person, with: ‘De li occhi suoi: From her eyes’. This second part is divided in two: for in the one I speak of her eyes, which are the source of love: in the second I speak of her mouth, which is love’s end. And so that all evil thought may be dispersed here and now, remember you who read, that it is written above that my lady’s greeting, that which arose from the movement of her mouth, was the end of my desires, while I could receive it.

Next where I say: ‘Canzone, io so che tu: Canzone, I know that you’ I add a stanza almost as a handmaiden to the others in which I say what I desire of my canzone: and since the last part is easy to understand I will not trouble to divide it further. I agree that to understand this canzone further it would be necessary to employ more minute divisions: but anyone who has insufficient wit to be able to understand it from the divisions made will not displease me if they leave it alone, since I am afraid I have certainly communicated its meaning to too many, by the divisions I have made, if it comes about that many are able to hear it.

XX He is requested to say what Love is

XX He is requested to say what Love is

After this canzone was circulated for a while amongst people, as it happened that one of my friends heard it, his will moved him to beg me that I should tell him what Love is, having, perhaps from the words he heard, a greater faith in me than was merited. So, thinking that after treating of that subject it would be good to say something of Love, and thinking that my friend would be pleased, I decided to write a verse in which I would treat of Love: and then I wrote this sonetto, which begins: ‘Amore e´l cor gentil’.

Love and the gentle heart are one thing,

as the wise man puts it in his verse,

and each without the other would be dust,

as a rational soul would be without its reason.

Nature, when she is loving, takes

Amor for lord, and the heart for his home,

in which sleeping he reposes

sometimes a short, sometimes a longer day.

Beauty may appear, in a wise lady,

so pleasant to the eyes, that in the heart,

is born a desire for pleasant things:

which stays so long a time in that place,

that it makes the spirit of Love wake.

And likewise in a lady works a worthy man.

This sonetto is divided in two parts: in the first I say of him what he is potentially: in the second I say of him how the potentiality fulfils itself in actuality. The second begins with ‘Bieltate appare: Beauty may appear’. The first divides in two: in the first I say in what object this potentiality exists: in the second I say how this object and this potentiality come into being, and how the one enshrines the other as form content. The second begins with: ‘Falli natura: Nature takes’. Then where I say: ‘Bieltate appare’ I say how the potentiality fulfils itself in actuality: and firstly how it fulfils itself in a man, then how it fulfils itself in a lady, with: ‘E simil face in donna: And likewise in a lady works’.

Index to the First Lines of the Poems

- Ballad, I would have you find Amor,

- Every one of my thoughts speaks of Love:

- With the other ladies you mock my looks,

- All I encounter in my mind dies,

- Often it is brought home to my mind

- Ladies who have knowledge of love,

- Love and the gentle heart are one thing,