Geoffrey Chaucer

Troilus and Cressida

Book V

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2001, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

1.

Began to near the fatal destiny

that Jove has in his disposition

and to you, angry Parcae, sisters three

is committed for its execution:

by which Cressida must leave the town,

and Troilus shall live on in pain

till Lachesis cease to spin again.

‘The Three Fates’

Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1611 - 1637

The Rijksmuseum

2.

The golden-haired Phoebus high aloft

had three times, with all his sunny beams,

melted the snow, and Zephyrus as oft

had brought again the tender leaves green,

since the son of Hecuba the queen,

began to first love her for whom his sorrow

was all because she would depart the morrow.

3.

At prime of day full ready was Diomede

Cressid to the Greek host to lead,

for sorrow of which she felt her heart bleed

as she who knew not what was best, indeed.

And truly, as men in books read,

no man ever knew a woman with her cares,

or who was so loth out of the town to fare.

4.

This Troilus, without plan or lore,

like a man joyless and forlorn,

was waiting on his lady evermore

she that was every part and more,

of all his pleasure and joy before.

But Troilus, farewell now all your joy,

for you will never see her again in Troy.

5.

Truth is that while he waited in this manner

he was able manfully his woe to hide,

that it was scarcely seen in his cheer:

but at the gate where she was due to ride

out with certain folk, he hovered beside,

so woebegone, though he did not complain,

that he could scarcely sit his horse for pain.

6.

He shook with anger, his heart began to gnaw,

when Diomed his horse prepared to dress,

and said to himself this very saw:

‘Alas,’ he said, ‘this state of wretchedness,

why do I suffer it, why no redress?

Would it not be better at once to die

than evermore in languor lie?

7.

Why don’t I give at once rich and poor

something to do before I see her go?

Why do I not set all Troy in uproar?

Why do I not slay Diomed also?

Why do I not with a man or two

steal her away? Why should I thus endure?

Why do I not aid my own cure?’

8.

But why he would not do so fell a deed

that will I say, and why he left it there.

He had in his heart always a kind of dread

lest Cressid in the tumult of the affair

might be slain: lo, this was all his care.

Otherwise, for certain, as I said before,

he would have done it without a word more.

9.

Cressid, when she was ready to ride,

sighed full sorrowfully and said: ‘Alas!’

but forth she must, whatever might betide,

and forth she rode full sorrowfully apace.

There was no other remedy in this case.

What wonder is it though, she felt the smart

when she must forgo her own sweetheart?

10.

This Troilus, in the way of courtesy,

with hawk on hand and with a large crowd

of knights, rode and kept her company,

passing all the valley far without.

And would have ridden further, without doubt,

most gladly, and woe it was so soon to go:

but turn he must, as he was forced to do.

11.

And, at that moment, Antenor had come

out of the Greek host, and every knight

was glad of it, and said that he was welcome.

And Troilus, though his heart was not light,

took pains indeed as best he might

to keep from weeping, at the least,

and kissed Antenor, and was pleased.

12.

And after that he must his leave take,

and cast his eye on her piteously:

and he rode near, his cause to make,

to take her by the hand all soberly.

And lord! she began to weep so tenderly!

And he full soft and quietly began to say:

‘Now do not kill me, hold to your day.’

13.

With that he turned his courser all about

with pale face, and to Diomed

spoke no word, nor none with all the crowd:

of which the son of Tydeus took heed,

like one who knew more than the creed

in such a case, and to her rein he leant:

and Troilus, to Troy he homeward went.

14.

This Diomed, that led her by the bridle,

when he saw the folk of Troy were away,

thought: ‘All my labour shall not be idle,

if I may I’ll somewhat to her say.

For at the least ‘twill shorten the way.

I have heard it said, times twice twelve,

“He’s a fool who forgets to aid himself.”

15.

But nonetheless he thought this, well enough,

that ‘certainly I do this for naught

if I speak of love, or make it tough:

for doubtless, if she has in her thought

him whom I guess, ‘twill not be a short

time ere she forget: but I shall find the means

that she’ll not know all’s not what it seems.

16.

This Diomed, like one who knew his good,

when this was done, fell to speech

of this and that, and asked why she stood

in such unease, and began her to beseech

that if he might increase, or reach

to anything that might be her ease, she should

command it of him, and he would.

17.

For truly he swore to her, as a knight,

that there was nothing which might her please

that he’d not be at pains with all his might

to do, so as to set her heart at ease.

And prayed her sorrows she might appease,

and said: ‘You see, we Greeks can take joy

in honouring you, as well as folks of Troy.’

18.

He also said this: ‘I know, you think it strange:

and that’s no wonder, for it is new to you,

the company of Trojans to exchange

for folk of Greece, whom you never knew.

But God forbid that you do not as true

a Greek among all of us find

as any Trojan is, and just as kind.

19.

And because I swore you truly, right now

to be your friend and help you as I might,

and because I more acquaintance of you

have had than any other stranger knight,

so from this time forth I pray, day and night,

command me, however much it smart,

to do whatever pleases your heart:

20.

and that you would me as your brother treat,

and not to disdain my friendship out of spite:

and though your sorrows be for things great,

I know not why, but without more respite,

my heart to mend that would take great delight.

And if I may not your hurts redress,

I am still sorry for your heaviness.

21.

And though you Trojans with us Greeks are wrath

and will be many a day yet, you see,

one god of love in truth we serve him both.

And, for the love of God, my lady free,

whoever you hate, be not wrath with me.

For truly there can no knight you serve

who’d be half so loth your wrath to deserve.

22.

And were it not that we are near the tent

of Calchas, who may have seen us both, I say,

I would tell you, of this, all my intent:

but it must stay sealed till another day.

Give me your hand, I am, and shall be always,

God help me, while my life may endure,

your own above any other creature.

23.

This I have never said before to woman born:

for as I wish that God would glad me so,

I never loved a woman here before

as a paramour, nor never shall more.

And, for the love of God, be not my foe:

although I cannot to you, my lady dear,

speak winningly, for I have to learn that here.

24.

And wonder not, my own lady bright,

though I speak to you of love so blithe:

for I have heard of this in many a knight,

who loved one he’d never seen in his life.

Also I have not the power for strife

with the god of love, but him I will obey

always: and mercy from you I pray.

25.

There are so many worthy knights in this place,

and you so fair, that every one of them all

will take pains to stand well in your grace.

But if to me so fair a grace might fall,

that you on me as your servant would call,

so humbly but so truly would I serve

more than any, till death me unnerve.

26.

Cressid to his proposal little answered,

like one that with sorrow was oppressed so,

that in effect she naught of his tale heard

but here and there perhaps a word or two though,

She thought her sorrowful heart would break in two.

For when she began her father to espy,

she began to fall from her horse, well nigh.

27.

But nonetheless she thanked Diomede

for all his trouble and his good cheer

and that he offered her friendship in need,

and she accepted it with a good manner,

and wished to do what pleased him and was dear:

and she would trust him, and well she might,

as she said, and from her horse did alight.

28.

Her father has her in his arms at once,

and twenty time he kissed his daughter sweet,

and said: ‘O my dear daughter, welcome.’

She said she was glad with him to meet,

and stood, mute, mild and meek him to greet.

But here I leave her with her father to dwell,

and straight I will to you of Troilus tell.

29.

To Troy has come the woeful Troilus

in sorrow beyond all sorrows’ smart,

with angry look and face most hideous.

Then suddenly down from his horse he starts

and through his palace, with a swollen heart,

to his room he goes: of nothing he took heed,

and no one dared to speak to him indeed.

30.

And there his sorrows that he contained had,

he gave free issue to and ‘Death,’ he cried:

and in his throes, frenzied and mad,

he cursed Jove, Apollo and Cupid, ay,

cursed Ceres, Bacchus and Venus beside,

his birth, himself, his fate, and even nature,

and, save his lady, every other creature.

31.

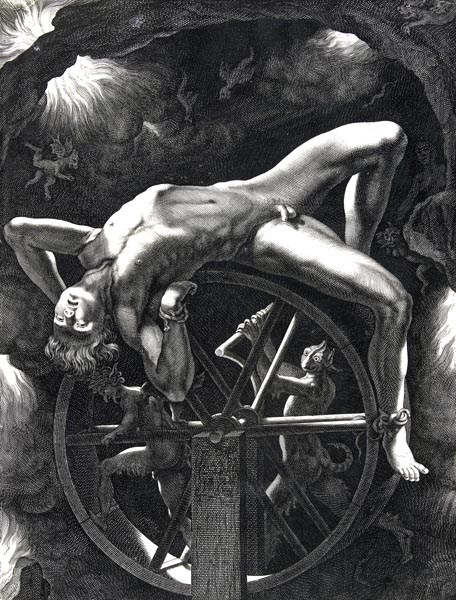

To bed he goes, and tosses there and turns

in fury, as does Ixion in hell:

and in this way nearly to dawn sojourns.

But then he his heart a little began to quell

through his tears which had begun to well:

and piteously he cried out for Cressid,

and to himself thus he spoke and said:

‘Ixion on the Wheel’

Cornelis Bloemaert (II), 1655 - 1700

The Rijksmuseum

32.

Where is my own lady beloved and dear?

Where is her white breast, where is it, where?

Where are her arms and her eyes clear

that last night at this time with me were?

Now may I weep alone with many a tear,

and grasp about I may, but in this place,

save a pillow, I find naught to embrace.

33.

What shall I do? When will she come again?

I do not know why, alas, I let her go.

Would to God, I had then been slain!

O my heart, Cressid, O sweet foe.

O my lady I love, and love no other so,

evermore my heart I give to you,

see how I die, you cannot me rescue.

34.

Who sees you now my true lodestar?

Who sits right now or stands in your presence?

Who now can comfort your heart’s war?

Now I’m gone, to whom do you grant audience?

Who speaks for me right now in my absence?

Alas, no one (and that is all my care):

for well I know, in evil, as I, you fare.

35.

How can I thus ten days endure.

when I the first night have all this pain?

How shall she do likewise, sorrowful creature?

Through tenderness, how can she sustain

such woe for me? O piteous, pale, and green

will be your fresh womanly face

for languor, before you return to this place.’

36.

And when he fell into slumberings

at once he would begin to groan

and dream of the dreadfullest things

that might be: for instance he was alone

in a horrid place, making his moan,

or dreamed that he were amongst all

his enemies, into their hands to fall.

37.

And at that his body would start

and with the start suddenly awake:

and such a tremor feel in his heart

that from the fear his body would quake:

and with that he would a noise make

that seemed as though he were falling deep

from high aloft, and then he would weep.

38.

And sorrow for himself so piteously,

that it was a wonder to hear his fantasy.

Another time he would mightily

comfort himself and say it was folly

to endure dread so causelessly,

and then begin his bitter sorrows anew,

so that all men might his sorrows rue.

39.

Who could rightly tell, or fully describe

his woe, his cries, his languor, and his pain?

Not all the men that were or are alive.

You, reader, may yourself full well divine

that such a woe my wit cannot define.

Idle to try and forge it link by link,

when it wearies my wits even as I think.

40.

In heaven yet the stars could be seen,

though waxing pale and full was the moon:

and the horizon white began to gleam

all eastward, as it is wont to do.

And Phoebus with his rosy chariot too

soon after that began to start,

when this Troilus sent for Pandar.

41.

This Pandar, that the whole day before

might not come there Troilus to see

(even if he had on his life have sworn)

for with King Priam all day was he,

so that he was not at liberty

to go anywhere. But on the morrow went

to Troilus, when he for him sent.

42.

For in his heart he could well divine

that Troilus all night from sorrow woke:

and that he would tell him how he pined

this he knew well enough without a book.

So that to his chamber his way he took,

and Troilus then soberly did greet

and on the bed quickly took a seat.

43.

‘My Pandarus,’ said Troilus, ‘the sorrow

that I suffer I cannot long endure.

I know I shall not live till tomorrow:

because of which I venture

to tell you of my sepulchre

the form: and my property do you dispose

just where you think it rightly goes.

44.

But of the fire and flame for my funeral,

in which my body shall be burnt indeed,

and of the feast and games and all

at my vigil I pray you take heed

that all be fitting, and offer Mars my steed,

my sword, my helmet: and loved brother dear,

my shield give to Pallas, who shines clear.

45.

The dust to which my burnt heart shall turn,

that I pray you take and conserve

in a vessel, that men call an urn,

of gold, and to my lady that I serve

for love of whom death I reserve,

so give it her, and do me this courtesy

to pray her to keep it in my memory.

46.

For I feel truly by my malady

and by the dreams now and times ago

that of a certainty I must die.

Also the owl they call Escalipho,

has shrieked after me two nights so,

and divine Mercury, of this woeful wretch

guide the soul, and when you wish, it fetch.

‘Proserpina Turning Ascalaphus into an Owl’

Wilhelm Janson (Holland, Amsterdam), Antonio Tempesta (Italy, Florence, 1555-1630)

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art

47.

Pandar answered and said: ‘Troilus,

my dear friend, as I have said before

it is folly to sorrow thus,

and needless: I can say no more.

But whosoever will not trust to my lore,

I can see for him no remedy

but to let him keep his fantasy.

48.

But, Troilus, I pray you tell me now

if you think that before this any man might

have loved his paramour as much as thou?

Why, God knows, from many a worthy knight

his lady has gone for a fortnight

and he not made half such an affair.

What need is there to cause yourself such care?

49.

Since day by day you yourself can see

that from his lover or else from his wife

a man must part of necessity.

Yes, though he love her as his own life,

yet he will not with himself create such strife:

for well you know, my loved brother dear

friends may not always be together here.

50.

What do folks do who see their lovers wedded

by powerful friends, as it befalls full oft.

And in their spouses’ bed see them bedded?

God knows they take it wisely, fair and soft.

Because good hopes hold up their heart aloft

and, since they can a time of sorrow endure,

as time has hurt them, so time does them cure.

51.

So should you endure, and let slide

the time, and try to be glad and light.

Ten days is not so long to abide.

And since she has promised you aright

to return, she’ll break it for no other knight.

For do not fear but she will find a way

to return: my life on that I lay.

52.

Your dreams and all such fantasy

drive out, and let them take their chance:

for they proceed from your melancholy

that makes you feel in sleep all this penance.

A straw for all such dreams’ significance!

God help me so, they are not worth a bean:

No man knows truly what dreams mean.

53.

For priests of the temple tell you this,

that dreams are the revelations

of gods: and also what they tell is

that they are all infernal illusions.

And doctors say that from complexions

they proceed, or fasts, or gluttony.

Who knows in truth then what they signify?

54.

Also others say that through impressions

(as when a man has something fixed in mind),

that from those come such visions:

and others say, as they in books find,

that according to the time of year by kind

men dream, and that the effect goes by the moon.

But believe no dream, for then wrong is done.

55.

Worthy of these dreams are old wives,

and truly to take augury from fowls:

for fear of which men think to lose their lives,

at raven’s forebodings or the shrieks of owls.

To trust in that is both false and foul.

Alas! Alas! So noble a creature

as is a man, to fear such ordure!

56.

Therefore with all my heart I beseech

that you all this to yourself forgive:

and rise up now without more speech,

and let us think how we may give

ourselves to this time, and happily live

when she returns, which will be quite soon.

God help me so, that is what’s best to do.

57.

Rise! Let us speak of the lusty life in Troy

that we have led, and contrive

to while away the time, and rejoice

at times to come, of bliss so blithe.

And with the languor of these days twice five

we shall so forget our depression,

that it will scarcely cause any oppression.

58.

This town is full of lords, all about,

and the truce lasts all this while.

Let us go play in some lusty crowd

at Sarpedon’s, from here not a mile.

And thus you shall the time well beguile,

and pass it by until that blissful morrow

when you see her, the cause of all your sorrow.

59.

Now rise, my dear brother, Troilus,

for it is no honour to you, certainly

to weep, and linger in your bed thus.

For, truly, in this one thing you can trust me,

if you lie thus a day, or two, or three,

the folk will think that you from cowardice

feign to be sick, and that you dare not rise.

60.

This Troilus answered: ‘O brother dear,

this thing folk know who have suffered pain,

that, if he weeps and makes sorrowful cheer,

who feels the harm and smart in every vein,

it is no wonder: and though forever I complain

or weep always, I am not to blame,

since I have lost the reason for the game.

61.

But since I am forced to rise,

I shall rise as soon as ever I may:

and God, to whom my heart I sacrifice,

so send us quickly the tenth day.

For there was never fowl so fond of May

as I shall be when she comes to Troy,

who is the cause of my torment and joy.

62.

But where do you advise,’ said Troilus,

‘that we may best play in all this town?’

‘By God, my counsel is,’ said Pandarus,

‘to ride and play at King Sarpedon’s.’

So they talked long of this up and down

till Troilus began at last to give assent

and rise, and forth to Sarpedon they went.

63.

This Sarpedon was as honourable a man

as any in this life, full of high prowess,

and with all that might be served at table

that was dainty, though it cost great riches,

he fed them day by day, such nobleness,

as was said by the highest and the least,

was never seen before at any feast.

64.

Nor was there in this world an instrument

delicious, through wind or touch or cord,

from whatever distant place you went,

that tongue can tell of or heart record,

that was not played at that feast’s concord:

nor of ladies also was so fair a company

in dance, before then, ever seen with eye.

65.

But what use was this to Troilus

that, in his sorrow, cared for it naught?

For ever the same way his heart piteous

full eagerly Cressid, his lady, sought:

on her was ever all that his heart thought,

now this, now that so imagining,

that indeed no feasting can gladden him.

66.

These ladies also, that at the feast be,

since he knew his lady was away,

it was his sorrow them to see,

or to hear them instruments play:

for she that of his heart bore the key

was absent. Lo, this was his fantasy,

that no knight should be making melody.

67.

Nor was there an hour of day or night

when he was there, and no knight could hear,

that he did not say: ‘O lovesome lady bright,

how have you fared since you were here?

Come safe again, my own lady dear.’

But welaway, all this is but a maze:

Fortune defends him in vain ways.

68.

The letters also that she in past time

had sent him, alone he would read

a hundred times between noon and prime,

imagining her shape of woman, indeed,

within his heart, and every word and deed

that was past: and so he reached the end

of the fourth day, and said he would wend.

69.

And said: ‘Beloved brother, Pandarus,

do you intend that we shall here breathe

till Sarpedon say farewell to us?

It would be better if we took our leave.

For God’s love, let us now soon at eve,

take our leave, and homeward let us turn,

for truly I will not thus sojourn.

70.

Pandar answered: ‘Have we come here

to fetch fire and then run home again?

God help me so, I cannot tell where

we might go, if that I truly say

where anyone is more in the way

of welcoming us than Sarpedon, and I

hold it villainy suddenly to say goodbye.

71.

Since we said that we would be

with him a week: now, thus suddenly

on the fourth day to take of him our leave

would make him wonder at it, truly.

Let us hold to our purpose firmly:

and since you promised him to abide,

hold to it now, and after let us ride.’

72.

Thus, Pandarus, with much pain and woe,

made him remain, and at the week’s end

they took their leave of Sarpedon so,

and sped on their way to again.

Troilus said: ‘Now God grace me send

that I may find, at my homecoming,

Cressida is come! and at that began to sing.

73.

‘Yes, hazel-wood!’ thought this Pandarus,

and to himself soberly he said:

‘God knows, cooled will be all this hot fare

before Calchas send Troilus Cressid!’

But nevertheless he acted otherwise, and said,

and swore, indeed, his heart knew aright

she would come as soon as ever she might.

74.

When they are to the palace come

of Troilus, from their horses they alight,

and to the chamber then their way is taken

and till the time when it began to be night

they spoke of Cressida the bright.

And after this, when they thought it best,

they sped them both from supper to rest.

75.

On the morrow as day began to clear,

this Troilus rose from his bed,

and to Pandar, his own brother dear,

‘For love of God,’ full piteously he said,

‘Let us go see the palace of Cressid.

For since there is no other feast,

let us see her palace at the least.

76.

And with that, his household to deceive,

he found a reason into town to go,

and to Cressid’s house their way they weave.

But lord! this foolish Troilus full of woe!

He thought his sorrowful heart would break in two:

for when he saw her doors barred and all,

well nigh, for sorrow, down he began to fall.

77.

When he began to be aware and to behold

how shut was ever window of the place,

his heart began, he thought, to grow ice cold:

so that, with changed and deadly pale face,

without a word he forth began to pace,

and, as God wills, he began so fast to ride

that no man his countenance espied.

78.

Then he said this: ‘O palace desolate.

O house of houses once the best, so bright,

O palace empty and disconsolate,

O lantern of which quenched is the light,

O palace, once the day, that now is night,

you truly ought to fall and I to die

since she is gone who used to be our guide.

79.

O palace, once the crown of houses all,

illumined by the sun of all our bliss,

O ring from which the ruby is let fall,

O cause of woe that has been cause of bliss!

Since I may do no better, I would kiss

your cold doors, if I dared amongst this crowd:

and farewell shrine, of which the saint is out.’

80.

At that he cast on Pandarus his eye

with changed face, and piteous to behold:

and when he could the right time espy,

as he rode, to Pandarus he told

his new sorrow and also his joys old

so piteously and with such deathly hue,

that anyone might pity his woe too.

81.

For thenceforth he rode up and down,

and everything came to his memory

as he rode by the places of the town,

which he had once delighted to see.

‘Lo, yonder I saw my own lady dance:

and in that temple with her eye clear

I first caught sight of my right lady dear.

82.

And yonder I have heard right lustily

my dear heart laugh: and yonder play

I once saw her also full blissfully:

and yonder once to me she did say,

“Now, good sweet, love me well I pray.”

And yonder she began me so to behold

that to the death my heart is hers to hold.

83.

And at that corner, in yonder house,

I heard my most beloved lady dear

so womanly, with voice melodious

sing so well, so sweetly, and so clear,

that in my soul I think I still can hear

the blissful sound. And in yonder place

my lady first took me to her grace.’

84.

The he thought this: ‘O blissful lord, Cupid,

when I recall the past in memory

how you have worried me on every side,

men might make a book of it, a story.

What need have you to seek a victory

when I am yours and suffer all your will?

What joy have you when your own folk you kill?

85.

Truly on me, lord, you have worked your ire,

you mighty god, a dreadful god to grieve.

Now mercy, lord, you well know I desire

your grace most, of all delights that be.

And I will live and die as I believe:

for which in return I ask a boon,

that you send me Cressid again soon.

86.

Constrain her heart as fast to return

as you do mine with longing her to see:

then I know well that she will not sojourn.

Now, blissful lord, so cruel you cannot be

to the blood of Troy, I pray thee,

as Juno was to the Theban blood,

which brought the folk of Thebes no good.’

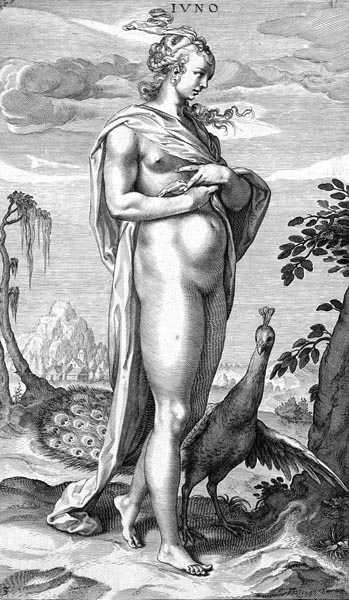

‘Juno’

Willem Isaacsz. van Swanenburg, after Michiel Jansz van Mierevelt, 1595 - 1612

The Rijksmuseum

87.

And after this he to the gate went

from which Cressid rode out at goodly pace:

and up and down there he his time spent,

and to himself often he said: ‘Alas!

from hence rode my bliss and my solace!

Would blissful God allow now, for his joy,

that I might see her come again to Troy!

88.

And to yonder hill I was her guide,

Alas, and there I took of her my leave.

And yonder I saw her to her father ride,

for sorrow of which my heart in two will cleave.

And hither home I came when it was eve,

and here I dwell an outcast from all joy,

and shall, till I see her again in Troy.’

89.

And of himself he imagined often

that he was disfigured, pale, grew less

than before, and that men often said then:

‘What can it be? Who can in truth guess

why Troilus shows all this heaviness?’

and all this was only his melancholy,

that he had of himself such a fantasy.

90.

Another time it seemed that he would

imagine everyone who went by the way

as pitying him, as if they should

say: ‘I am sorry Troilus will pass away.’

And so he spent one and another day.

As you have heard, such a life he led

as one who stood between hope and dread.

91.

So that he liked in his songs to show

the cause of his woe as best he might.

And make a song of words only a few

his woeful heart somewhat to make light.

And when he was away from all men’s sight,

he, with soft voice, of his lady dear,

who was absent, sang as you may hear:

92.

‘O star of which I have lost the light,

with sore heart I truly should bewail,

that, ever dark, in torment, night by night,

towards my death with following wind I sail:

so that if on the tenth night should fail

your bright beams’ guidance for even an hour,

my ship and me Charybdis will devour.’

93.

When he had sung this song, at once

he fell again into his sighs of old:

and every night, as before he’d done,

he stood the bright moon to behold,

and all his sorrow to the moon he told,

and said: ‘Yet, when you are horned anew

I shall be glad, if all the world be true.

94.

I saw your old horns also on the morrow,

when hence rode my true lady dear,

who is the cause of my torment and sorrow:

and so, O bright Lucina, the clear,

for love of God run quickly round your sphere!

For when your new horns begin to spring,

then she will come who will my bliss bring.’

95.

The days seemed more, and longer every night,

than they had used to be, he thought so,

and that the sun went his course awry,

by a longer way than he used to go:

and said: ‘Indeed, I think that lo!

the Sun’s son Phaethon is alive,

and amiss his father’s chariot does drive.’

‘The Fall of Phaeton’

Hendrick Goltzius, 1590

The Rijksmuseum

96.

Also fast along the walls he’d walk,

and the Greek host he would see,

and to himself like this he would talk:

‘Lo, yonder is my own lady free,

or else yonder where those tents be,

and thence comes this air that is so sweet,

that in my soul I feel it’s good complete.

97.

And certain this wind, that more and more

from time to time increases in my face,

is from my lady’s deep sighs sore.

I prove it thus, for in no other place

in all this town, save only in this space,

feel I a wind that sounds so like pain:

it says: “Alas, why parted are we twain?”’

98.

This long time he spent right thus,

till fully passed was the ninth night:

and ever beside him was this Pandarus

who busied himself with all his might

to comfort him and make his heart light,

always giving him hope of the tenth morrow

when she would come, and end all his sorrow.

99.

On the other side there was Cressid

with her few women among the Greek throng,

at which often each day: ‘Alas,’ she said,

‘that I was born! Well may my heart long

for my death, for now I have lived too long.

Alas, and I may not the thing amend,

for now ‘tis worse than I could comprehend.

100.

My father will in no way give me grace

to go again: for nothing that I can dream:

and if so be that I pass the term’s space,

my Troilus will in his heart deem

that I am false, and so it may well seem.

So shall I be complained of on every side,

for being born, so welaway what betide!

101.

And if I put myself in jeopardy

to steal away by night, and it befall

that I am caught, I shall be called a spy:

or else, lo, and I dread this most of all,

if into some wretch’s hands I fall,

I will be lost, though my heart be true.

Now, mighty God, you on my sorrow rue!’

102.

Full pale and waxen was her bright face,

her limbs delicate, as one who all the day

stood when she dared, and looked at the place

where she was born and where she lived her day.

And all the night weeping, alas, she lay,

and thus despairing, beyond all cure,

she led her life, this woeful creature.

103.

Many times a day she sighed in her distress,

and in her mind was always portraying

Troilus in his great worthiness,

and all his good words remembering

since that first day their love began to spring.

And so she set her woeful heart on fire

through remembrance of what was her desire.

104.

In all this world there’s not so cruel a heart,

that had he heard her complaining in her sorrow,

would not have wept for her pain’s smart,

so tenderly she wept both eve and morrow.

She had no need of tears to borrow.

And this was yet the worst of all her pain,

there was no one to whom she dare complain.

105.

Ruefully she looked out to Troy,

beheld the high towers and the halls.

‘Alas,’ she said, ‘the pleasure and the joy,

which is now turned into gall,

I have often had within those walls!

O Troilus, what are you doing now?’ she said:

‘Lord! Do you still think of Cressid?

106.

‘Alas, if I’d only trusted to you before,

and gone with you, as you told me ere this!

Then I would not be sighing half so sore.

Who could have said that I had done amiss

to steal away with such a one as he is?

But all too late comes the remedy

when men to the grave the corpse carry.

107.

It is too late to speak of this matter.

Prudence, alas! one of your eyes three

I always lacked before ever I came here:

time past was well remembered by me:

and present time I could always see:

but future time, before I was in this snare,

I could not see: that causes now my care.

108.

But nonetheless, let betide what betides,

I shall tomorrow at night, by east or west,

steal out of this host at one of those sides:

and go with Troilus wherever he thinks best.

This purpose will I hold to at the least,

not swayed by wicked tongues’ janglery,

for always of love wretches have had envy.

109.

For who would of every word take heed,

or be ruled by every other’s wit,

he or she will never thrive, indeed.

For the thing that some men blame, yet,

lo, other kinds of folk commend it.

And in all such variance, as for me,

what suffices is my felicity.

110.

With which, without any more ado,

to Troy I will go, in conclusion.’

But, God knows, before months two

she will still be far from that intention.

For both Troilus and Troy town

shall without hindrance from her heart slide,

for she will purpose to abide.

111.

This Diomede, of whom to tell I began,

goes now within himself ever arguing

with all the wit, and all that ever he can,

as to how best, with shortest tarrying,

Cressid’s heart into his net he might bring.

There was no end to this in his mind:

to catch her he laid out both hook and line.

112.

But nonetheless in his heart he thought

that she was not without her love in Troy:

for never, since he had her thence brought,

had he seen her laughing or in joy.

He did not know what was his best ploy.

‘But to attempt it,’ he said, ‘should not grieve:

for he that attempts nothing will nothing achieve.

113.

Yet he said to himself one night:

‘Now am I not a fool, who well know how

her woe is for love of another knight,

and yet I go to attempt her now?

I ought to know it’s vain, and that allow.

For as wise folk in books express,

‘Men cannot woo someone who is in sadness.’

114.

But whoever might win such a flower

from him whom she mourns for night and day,

he might say he was a conqueror.’

And so at once, as is the bold man’s way,

thought in his heart: ‘Come what, come may,

although I die, I will her heart seek:

I can lose nothing but the words I speak.’

115.

This Diomede, as the books declare,

was in time of need ready and courageous:

with stern voice and mighty limbs square,

hardy, headstrong, tough, and chivalrous,

in deeds like his father, Tydeus.

And some men say boastful of tongue.

And heir he was to Argos and Calydon.

116.

Cressid was of a modest stature:

and as to shape, to face, and cheer

there might have been no fairer creature,

and often times it was her manner,

to go braided, with her hair clear

down by her collar at her back behind,

which with a thread of gold she would bind.

117.

And save that her eyebrows met together,

there was no fault in aught I can espy:

but to speak of her eyes clear:

lo, truly, those who saw her write,

that Paradise stood formed in her eye.

And with her rich beauty evermore

Love strove, in her, as to which was more.

118.

She was sober, simple and wise with all,

the best nurtured also that might be,

and lovely in her speech in general,

charitable, stately, joyous, free:

and never lacking in sympathy:

tender-hearted, variable in courage:

but truly I cannot tell her age.

119.

And Troilus was well grown in height,

and completely formed so in proportion

that Nature might not improve the knight:

young, fresh, strong, and hardy as a lion:

true as steel in every condition,

one of the most virtuous creatures

that was, or will be while the world endures.

120.

And certainly in story it is found

that Troilus was never by right

in his time, in any aspect second

in daring deeds proper to a knight:

though a giant might exceed his might,

his heart with the first and with the best

stood equal, to dare whatever test.

121.

But to tell more of Diomed,

it fell out that after on the tenth day

since Cressid from the city was led,

this Diomed, fresh as a branch in May,

came to the tent where Calchas lay,

and feigned business to be done:

but what he meant I will tell you anon.

122.

Cressid, in a few short words to tell,

welcomed him, and sat him by her side:

and to stay there suited him right well.

And after this, without delay they tried

the spices and the wine that men supplied.

And they spoke of this and that together

as friends do, some of which you shall hear.

123.

He first touched on the war, in his speech,

between them and the folk of Troy town,

and of the siege he began to beseech

her to tell him what was her opinion,

from that request he descended down

to asking her if they were strange to her thought

the Greek customs and actions that they wrought:

124.

and why her father waited so long

to wed her to some worthy knight.

Cressid, who felt the pains strong

of her love for Troilus, her true light,

as far as she had cunning or might

answered him then: but as to his intent

she seemed not to realise what he meant.

125.

But nonetheless this same Diomede

began to fee assured, and thus he said:

‘If I of what you tell rightly heed,

I think this, O my lady, Cressid,

that since I first my hand on your bridle laid

when you came out of Troy on that morrow,

I have never seen you except you sorrow.

126.

I cannot see what the cause might be,

unless for love of some Trojan it were:

which would be a sore thought to me

that you for any knight that lives there

would spill a quarter of a tear,

or piteously yourself so beguile,

for certain, it is not worth the while.

127.

The folk of Troy, so to say, all and some

are in prison, as you yourself see.

From thence shall not one alive come

for all the gold between the sun and sea.

Trust this well, and understand me,

there shall not one in mercy go alive,

though he were lord of worlds twice five.

128.

Such vengeance on them for Helen again

will we take before from here we wend,

that the Manes, who are the gods of pain

will be fearful lest the Greeks put them to shame.

And men shall dread, to the world’s end

from henceforth, the ravishing of a queen,

so cruel shall what we wreak on them be seen.

129.

And unless Calchas speaks ambiguous phrases

(that is to say, with double words and sly,

such as men call “words with two faces”),

you will know well that I did not lie,

and see all this thing with your own eye,

and that anon: you do not know how soon.

Now take heed because it will be done.

130.

Why else do you think you father would

have given Antenor for you anon,

unless he knew the city should

be destroyed? Why, if I lie strike me down!

He knew full well that there will not be one

Trojan who escapes: and from that great fear

he did not dare leave you living longer there.

131.

What more will you have, lovesome lady dear?

Let Troy and Trojan from your heart fade.

Drive out that bitter hope, and make good cheer,

and recall once more the beauty of your face

that you with salt tears so deface.

For Troy is brought to such jeopardy

that to save it now there is no remedy.

132.

And think well, you will in a Greek find

a more perfect love, before tonight,

than any Trojan is, and more kind,

and who will serve you better with all his might.

And if you allow it, my lady bright,

I will be he who serves you, myself,

yes, rather than be lord of Greeces twelve.

133.

And with that word he began to blush red,

and in his speech, his voice a little shook,

and he turned aside a little way his head,

and ceased a while: and afterwards awoke,

and soberly on her he threw his look,

and said: ‘I am, though to you it be no joy,

as noble a man as any knight in Troy.

134.

For if my father, Tydeus,’ he said,

‘had lived, I would have been before this,

a king of Argos and Calydon, Cressid:

and I hope that I shall yet be so, yes

for he was slain, alas! the more harm is,

unhappily, at Thebes, you understand

to Polynices’s harm and many a man.

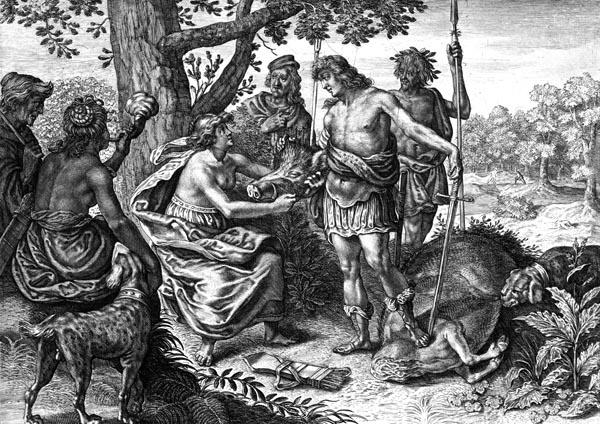

‘Eteocles and Polynices, Admonished by their Mother Jocasta’

Pieter Franciscus Martenasie, after Andries Lens, 1774

The Rijksmuseum

135.

But, my heart (since I am your man,

and you the first from whom I seek grace

to serve you as devotedly as I can,

and ever will while I to live have space),

so, I pray, before I leave this place,

that you will grant that I may to-morrow

at better leisure tell you all my sorrow.

136.

How should I tell all the words he said?

he spoke enough for one day at least:

it served him well, he spoke so that Cressid

granted, on the morrow, at his request,

to speak with him again, though it were best

if he did not speak of such a matter.

And thus she said to him, as you may hear,

137.

like one whose heart was set on Troilus

so firmly that none might that erase:

and distantly, she spoke and said thus:

‘O Diomede, I love that very place

where I was born, and Jove, of his grace

deliver it soon from all its care.

God, of your might, leave it fair.

138.

That the Greeks would vengeance on Troy wreak

if they could, I know that truly, yes:

but it will not fall out as you speak.

And God willing, and besides all this,

I know my father wise and ready is,

and because he has bought me, as you told,

so dear, I am the more his to hold.

139.

That the Greeks are of high condition

I know well: but certainly men shall find

as worthy folk within Troy town,

as able, and as perfect, and as kind,

as are between the Orcades and Ind.

And that you could well your lady serve,

I know well also, her thanks to deserve.

140.

But as to speech of love, indeed,’ she sighed,

‘I had a lord to whom I wedded was,

who was all my heart until he died:

and no other love (so help me Pallas)

is in my heart, nor ever was,

and that you are of noble and high kin,

I have well heard it said, for certain.

141.

And so that makes me more greatly wonder

that you would scorn any woman so.

God knows, love and I are far asunder:

I am more disposed, I swear it though,

until my death, to weep and make woe.

What I shall do hereafter I cannot say:

but truly as yet I do not wish to play.

142.

My heart is now in tribulation,

and you in arms busy day by day.

Hereafter, when you have won the town,

perhaps then so it happen may,

that when I see what I have never seen, yea,

then will I do what I have never wrought!

This should be enough for you, it ought.

143.

Tomorrow gladly I will speak you plain,

so long as you do not touch on this matter.

And when you wish you may come here again:

and, before you go, this I say here:

so help me Pallas with her tresses clear,

if for any Greek I would have ruth,

it would be for yourself, by my truth.

144.

I do not say therefore that I will you love,

nor say no: but in conclusion

I mean well, by God that sits above.’

And therewithal she cast her eyes down,

and began to sigh, and said : ‘O Troy town,

I still ask God that in quiet and in rest

I may see you, or let my heart burst.’

145.

But in effect, and in short to say,

this Diomede afresh and new again

began to press her, and her mercy pray.

And after this, the truth to relay,

he took her glove, gladdening his day:

and finally, when it was nearing eve

and all was well, he rose and took his leave.

146.

Bright Venus followed and ever lead

the way, where great Phoebus began to alight:

and Cynthia her chariot horses sped

to whirl out of the Lion, if she might:

and Zodiac showed his candles bright,

when Cressida to her bed went

within her father’s fair bright tent.

147.

Turning over in her soul up and down

the words of this forceful Diomede,

his great rank, and the peril of the town,

and that she was alone, and in need

of friends’ help: so began to breed

the reason why (truth to tell)

she fully decided there to dwell.

148.

The morrow came, and devotedly, to speak,

this Diomede is come to Cressid,

and shortly, lest you your reading break,

he for himself spoke so well and said,

that all her bitter sighs to rest he laid.

And finally, the truth to say again,

he reft her of the great part of her pain.

149.

And after this the story tells us

that she gave him the fair bay steed,

that he had once won from Troilus:

and also a brooch (of that there was no need)

that was Troilus’s, she gave this Diomede.

And also, the better from sorrow him to relieve,

she made him wear a pennon of her sleeve.

150.

I find also in the stories elsewhere,

when, through the body, hurt was Diomede

by Troilus, then she wept many a tear,

when she saw his wide wounds bleed:

and that to care for him she took good heed,

and to heal him of his sorrow’s smart.

Men say, not I, that she gave him her heart.

151.

But truly, so the story tells us,

there was never woman more full of woe

than she, when she betrayed Troilus.

She said: ‘Alas, for now I see clearly go

my name for truth in love, for ever though!

For I have betrayed one, the noblest

that ever was, and one the worthiest.

152.

Alas! of me, to the world’s end,

shall neither be written nor be sung

one good word, for these books will end

in reproach: O, rolled on many a tongue,

throughout the world my bell will be rung

and women will hate me most of all.

Alas that such a fate on me should fall!

153.

They will say, as much as in me strength is,

I have done them dishonour, welaway!

Though I am not the first that did amiss,

what help is that in taking blame away?

But since I see there is no better way,

and that it is too late for me to rue,

To Diomede at least I will be true.

154.

But Troilus, since no better to do I may,

and since we thus are parted you and I,

yet I pray God to give you each good day,

as to the noblest man, truly,

that ever I saw, who served faithfully,

and who best can his lady’s honour keep

(and with those words she began to weep).

155.

And for certain, I will hate you never:

and friend’s love, that you shall have from me,

and my good word, though I live for ever.

And, truly, I would sorry be

to see you in adversity.

And guiltless you I well know I leave:

but all will pass, and so I take my leave.’

156.

But truly, how long it was before

she forsook him for this Diomede,

no author tells of that, I am sure.

Let everyone now, of their books, take heed:

they shall no statement of it find, indeed,

for though he began to woo her at once,

before he won her more was to be done.

157.

Nor do I wish this foolish woman to chide

more than the story will describe.

Her name, alas, is published so wide,

that for her guilt it ought to suffice.

And if I might excuse her in any wise

since she was so sorry for her untruth,

well I would excuse her still from ruth.

158.

This Troilus, as before I have told,

passed the time so, as best he might:

but often his heart was hot and cold,

and especially on that very ninth night,

when on the morrow she had promised aright

to come to him again. God knows little rest

had he that night: he wished not to be sleep’s guest.

159.

The laurel-crowned Phoebus with his heat

began, on his upward course as he went,

to warm the Eastern Sea’s waves wet:

and Nisus’s daughter sang with fresh intent,

when Troilus for his Pandarus sent:

and on the walls of the town they waited,

to see if they could see aught of Cressid.

160.

Till it was noon they stood there to see

who came there: and everyone that might

have come from afar, they said that it was she,

until they could see them aright.

Now their hearts were dull, now they were light:

and thus deceived they stood and stared

after nothing, this Troilus and Pandar.

161.

To Pandarus this Troilus then said:

‘For aught I know, before noon, truly,

into this town comes not Cressid.

She has enough to do, assuredly,

to part from her father, so think I:

her old father will yet make her dine

before she go: God make his heart pine!’

162.

Pandar answered: ‘It may well be, for certain:

and therefore let us dine, I beseech:

and after noon you may then come again.’

And home they went without more speech:

and came again, but long may they seek

before they find what they desire to meet:

Fortune intends to treat them with deceit.

163.

Troilus said: ‘I see well now that she

is delayed by her old father so,

that before she comes it will nigh evening be.

Come now, I will to the gate go.

These porters are they not witless though:

and I will make them hold the gate

without a reason, though she come late.’

164.

The day goes fast, and after comes the eve,

and yet came not to Troilus Cressid.

He looked out to hedge, and grove, and tree,

and far his head beyond the wall he set,

and at the last he turned him and said:

‘By God, I know her meaning now, Pandar!

Almost, indeed, renewed was all my care.

165.

Now without doubt this lady knows what’s good

I think, she means to ride secretly.

I commend her wisdom, by my blood!

She will not make people foolishly

gaze at her when she comes: but softly

by night into the town she thinks to ride.

And, dear brother, we have not long to bide.

166.

We have nothing else to do but this.

And Pandarus, now, will you believe me?

By my truth, I see her! There she is!

Raise up your eyes man: do you not see?’

Pandar answered: ‘No, as I might rich be.

All wrong, by God: what see you, by what art?

What I see yonder is but a travelling cart.’

167.

‘Alas, you see truly aright,’ said Troilus:

‘but certain it is not all for aught

that in my heart I rejoice thus.

Of some future good I have a thought.

I know not how, but since I was wrought

I never felt such comfort, I dare say:

she comes tonight, my life on that I lay.’

168.

Pandar answered: ‘It may be, well enough:

and agreed with him in whatever he said:

but in his heart he thought and softly mocked,

and to himself full soberly he said:

‘From the hazel-wood where Jolly Robin played,

will come whatever you wait for here.

Yes, farewell all the snows of yester-year.’

169.

The warden of the gates began to call

to the folk who beyond the gates were,

and asked them to drive in their beasts, all,

or all night they must remain there.

And very late at night, with many a tear,

this Troilus began the homeward ride:

for he could see it was no help to abide.

170.

But nonetheless he cheered himself like this:

he thought he had miscounted the day,

and said: ‘I have understood it all amiss.

For the very night before Cressid went away

she said: “I shall be here, if I may,

before the moon, O dear sweetheart, sees

the Lion, passing from this Aries.”

171.

So that her promise she may yet keep.’

And on the morrow to the gate he went,

and up and down, by West and then by East,

upon the walls he made many an ascent.

But all for naught: his hope was spent.

So that at night, in sorrow with sighs sore,

he went home without one hope more.

172.

Thus hope all clean out of his heart was fled:

he had nothing left to which he could hang:

but with the pain he thought his heart bled,

so sharp were his throes and wondrous strong.

For when he saw that she delayed so long,

he knew not how to judge of it aright,

since she had broken promise, or she might.

173.

The third, fourth, fifth, sixth day

after those ten days, of which I told,

between hope and dread his heart lay,

yet trusting to her promises of old.

But when she did not her appointment hold,

he could see now no other remedy,

but to shape him soon to die indeed.

174.

At which the wicked spirit (God us bless!)

which men call mad jealousy,

began to creep in him through all this heaviness:

because of which, as he’d soon die indeed,

he neither ate nor drank from melancholy,

and also from all company he fled.

This was the life that all the time he led.

175.

He was so changed, that all manner of men

scarcely recognised him, where he went.

He was so lean, and also pale and wan

and feeble that he walked on crutches, bent:

and he thus injured himself with ill intent.

And whoever asked him what gave him smart,

he said the harm was all about his heart.

176.

Priam often, and also his mother dear,

his brother, and his sisters asked again

why he was so sorrowful in his cheer,

and what was the cause of all his pain

but all for naught: he would not explain,

but said he felt a grievous malady

about his heart, and fain would die indeed.

177.

So one day he lay down to sleep,

and it happened that in his sleep he thought

that he walked in a deep forest to weep

for love of her who these pains in him wrought.

And as, up and down, his way he sought,

he dreamed he saw a boar, with tusks so great,

that slept against the bright sun’s heat.

178.

And by this boar, fast in its limbs’ fold,

and ever kissing it, his lady bright, Cressid.

For sorrow of which, when he did behold,

for grief, out of his sleep he fled,

and loud he cried to Pandarus and said:

‘O Pandarus, now I know this, all about:

I am a dead man: there is no way out.

179.

My lady bright, Cressid, has me betrayed,

in whom I trusted most of any knight,

she elsewhere has now her heart laid.

The blissful gods through their great might

have in my dream showed me it aright.

So in my dream Cressid I did behold.’

And all this thing to Pandarus he told.

180.

‘O my Cressid, alas! what subtlety,

what new desire, what beauty, what science,

what wrath justly caused have you towards me?

What guilt towards me, what fell experience

has reft from me, alas, your adherence?

O trust, O faith, O deep assurance bright,

who has reft Cressid, from me, all my delight?

181.

Alas, why did I let you from this place go,

from which well nigh out of my wits I fled?

Who will trust now in any other oath?

God knows I thought, O lady bright, Cressid,

that every word was gospel that you said.

But who can better beguile us when they must,

than those in whom men place their greatest trust?

182.

What shall I do, my Pandarus, alas!

I feel now anew so sharp a pain,

since there is no remedy in this case,

it is better that with my hands twain

I slay myself, than ever thus complain.

For through my death my woe will have an end,

while I ruin myself with each day of life I spend.’

183.

Pandar answered and said: ‘Alas the day

that I was born: have I not said before this,

that dreams will many a man betray?

And why? Because folk read them amiss.

How dare you say that false your lady is,

because of some dream, simply through your fear?

Let that thought be, of dreams, you’re no interpreter.

184.

Perhaps since you dreamed of a boar,

it may be there so as to signify

her father, who is also old and hoar,

lying against the sun, about to die,

and she for sorrow begins to weep and cry,

and kisses him, where he lies on the ground:

thus should you your dream rightly expound.’

185.

‘What can I do then,’ said Troilus,

to know if this is true, however slight?’

‘Now you say wisely,’ said this Pandarus,

‘my advice is this, since you compose aright,

that hastily a letter to her you write,

through which you will easily bring about

your knowing the truth of what it is you doubt.

186.

And see now for why: this I well dare say,

that if it is so that she is untrue indeed,

I cannot believe that she’ll write back again.

And if she writes, you will quickly see,

whether she is in any way at liberty

to return again, or else in some clause

of it, if she cannot, she’ll assign a cause.

187.

You have not written to her since she went,

nor she to you: and this I dare lay,

that there may be such a reason for her intent,

that you yourself will scarcely say

it is not best for you both that she delay.

Now write to her then, and you will know soon

the truth of it all. There’s no more to be done.’

188.

They reached accord in this conclusion,

and that at once, these same lords two:

and hastily Troilus sat down,

and turned in his mind to and fro

how he might best describe to her his woe:

and to Cressid, his own lady dear,

he wrote thus, and said what you may hear:

189.

‘Right fresh flower, whose I have been and shall,

never serving elsewhere in any guise,

in heart, body, life, desire, thought and all:

I, woeful knight, humble in every wise

that tongue can tell or heart devise,

as truly as matter occupies space,

recommend myself to your noble grace.

190.

May it please you to think, sweetheart,

of what you know, how much time has gone

since I was left in bitter pain’s smart,

by your going, and relief there is none

that I have had, but ever worse become

from day to day, and so I must dwell

while you wish it, you of joy and woe my well.

191.

Because of which, with fearful heart true,

I write (as one that sorrow drives to write)

my woe, that every hour increases new,

lamenting as much as I dare, or can write.

And stained this is, that you may have sight

of the tears which from my eyes rain,

that would speak, if they could, and complain.

192.

I first beseech you that your eyes clear,

looking at this, defiled you will not hold:

and besides this, that you, my lady dear,

will deign this letter to behold.

And also because of my cares cold,

that numb my wit, if aught amiss seems part,

forgive it me, my own sweetheart.

193.

If any lover were to dare, or ought by right,

unto his lady, to piteously complain,

then I believe that I should be that knight,

considering that these two months twain

you have delayed, though you said again

but ten days with the Greeks you’d sojourn,

and yet in two months you do not return.

194.

But inasmuch as I must needs like

all that you wish, I dare not complain more,

but humbly with sorrowful sighs sigh.

I write to you my unquiet sorrows sore,

from day to day desiring evermore

to know fully how you fare,

if it’s your will, and what you do there.

195.

Whose welfare, and health also, God increase

in honour such, that upward in degree

it always grows and may it never cease:

as much as your heart can, my lady free,

devise, I pray to God so may it be.

And grant that you may pity me too,

as sure as I, in all, am true to you.

196.

And if you wish to know how I fare

whose woe no one can describe,

I can say no more, but that, full of every care,

at the writing of this letter I was alive

but ready from me my woeful ghost to drive:

which I delay, holding back, you understand,

pending the sight of a message from your hand.

197.

My two eyes, with which in vain I see,

of sorrowful salt tears are grown the wells:

my song is turned to sighs of my adversity:

my good to harm: my ease has become a hell.

my joy is woe: I can say to you nothing else,

but every joy or ease is turned, I see,

(for which I curse my life) to its contrary.

198.

Which with your coming home again to Troy

you might redress, and a thousand times in me

more than ever I had before increase the joy.

For there was never yet a heart so happy

to be alive, as I shall truly be

when I see you: and though no pity in sooth

may move you, yet think of keeping truth.

199.

And if it be my guilt has death deserved,

or if you no longer wish to see me,

in return for how I have served,

I beseech you, my heart’s lady free,

that hereupon you would write to me,

for love of God, my true lode-star,

when death brings an end to all my war.

200.

Or if any other cause makes you there dwell

that with your letter you bring me comfort:

for though to me your absence is a hell,

with patience I’ll endure woe as I ought ,

and with hope of your letter myself support.

Now write, sweet, and let me not complain:

with hope or death deliver me from pain.

201.

Indeed, my own dear heart true,

I know that, when you next me see

(I have so lost my health and my hue)

Cressid will not even know me.

Indeed, my heart’s day, my lady free,

so thirsts my heart ever to behold

your beauty, that to life I barely hold.

202.

I say no more, though I have things to say

to you, many more than I can tell:

but whether you cause me to live or die,

yet I pray God to give you each good day.

And fare you well, lovely, fair, fresh may,

you who life or death may me command:

and to your truth I ever set my hand,

203.

with well-being such that, unless you give me

the same well-being, I’ll no well-being have.

It lies in you to say, when you wish it to be,

that day when I’ll be clothed by the grave.

In you my life, in you the power to save

me from the misery of all pain’s smart.

And farewell now, my own sweetheart.’

204.

This letter was sent onwards to Cressid.

To which her answer in effect was this:

full piteously she wrote again and said

that just as soon as she might, that is,

she would come, and mend all that was amiss.

And finally she wrote and told him then

she would come, yes, but she knew not when.

205.

But in her letter she went to such excess,

it was a wonder, and swore she loved him best,

which he found were but empty promises.

But Troilus, you may now, East or West,

go pipe in an ivy leaf, if you so wish.

Thus goes the world: God shield us from mischance

and every one that holds to truth advance.

206.

The woe increased from day to night

of Troilus from this tarrying of Cressid:

And his hopes began to lessen and his might,

though which all down on his bed he laid.

He neither ate nor drank, nor slept, nor said

a word, imagining her unkind,

from which he well nigh lost his mind.

207.

This dream, of which I told you before,

was never lost from his remembrance.

He thought he had his lady never more,

and that Jove, from his providence,

had shown him in sleep the significance

of her untruth and his misadventure,

and that the boar was but a figure.

208.

Because of which for Sibyl, his sister, he sent,

she who was called Cassandra thereabouts:

and told her all the dream that he was sent,

and beseeched her to relieve him of his doubts

concerning the strong boar with tusks stout:

and finally, in a little while he found

Cassandra thus his dream began to expound.

‘Cassandra’

The Stratford gallery (p247, 1859) - Palmer, Henrietta Lee, b. 1834

Internet Archive Book Images

209.

She began to smile, and said: ‘ O brother dear,

if the truth of this you wish to know,

you must first a few old stories hear,

concerning Fortune’s overthrow

of lords of old: so that, within a throw,

you well this boar shall know, and of what kind

he is, as men in books may find.

210.

Diana, who was wrathful and in ire

because the Greeks had failed her sacrifice,

nor burnt the incense on her altar fire,

because the Greeks began her to despise,

revenged herself in a truly cruel wise.

For with a boar as large as ox in stall

she devoured their corn and vines all.

211.

To slay this boar the whole country was raised,

among whom there came, this boar to see

a maid, one of the world’s most praised:

and Meleager, lord of that country,

loved so this fresh maiden free,

that with courage, before he went

he slew the boar, and her the head he sent.

‘Meleager gives the Head of the Calydonian Boar to Atalanta’

Crispijn van de Passe (II), after Antonio Tempesta, c. 1636 - 1670

The Rijksmuseum

212.

From which, as the old books tell us,

there arose strife and great envy.

And from this lord descended Tydeus

by line, or else the old books lie,

but how this Meleager was caused to die,

through his mother’s act, I will not tell,

for it would take too long on that to dwell.

213.

She also told how Tydeus went,

to the strong city of Thebes,

to claim the kingdom his intent,

on behalf of his friend Lord Polynices

whose brother, Lord Eteocles,

wrongfully of Thebes held the strength:

she told all this slowly and at length.

214.

She also told how Haemonides with art

escaped when Tydeus slew fifty knights:

she also told all the prophecies by heart,

and how seven kings with their host’s might

besieged the city in that fight,

and of the holy serpent and the well,

and of the Furies, she began to tell.

215.

Of Archemorus’s burial, and the games,

and how Amphiaraüs fell through the ground,

how Tydeus Lord of Argos was slain,

and how Hippomedon quite soon

drowned, Parthenopaeus died of his wound.

and also how Capaneus, the proud,

was slain by a thunderbolt, that cried aloud.

216.

She told him then how each brother,

Eteocles and Polynices also,

in a skirmish slew the other,

and of Argeia’s weeping and her woe,

and how the town was burnt, and so

she descended down from stories old

to Diomede, and thus she spoke and told:

217.

This same boar betokens Diomede,

Tydeus’s son, that down descended is

from Meleager who made the boar to bleed.

And your lady, wherever she be, I say this,

Diomede has her heart, and she has his,

weep if you will, or not, but without doubt

this Diomede is in, and you are out.’

218.

‘You tell no truth,’ he said, ‘sorceress,

with all your false spirit of prophecy!

You think you are a great prophetess:

now do you not see this fool of fantasy

takes pains to give ladies the lie?

Away!’ he said: ‘may Jove bring you sorrow!

You’ll be proved false, perhaps tomorrow.

219.

As well tell lies about Alceste

who was of creatures (unless men lie)

the kindest there ever was, and the best.

For when her husband was in jeopardy

of death, unless she would accept to die,

she chose to die for him and go to hell,

and die she did, as us the books tell.’

‘Alceste’

Ertinger, Franz, 1640-ca. 1710

The New York Public Library

220.

Cassandra went, and he with cruel heart

forgot his woe, with anger at her speech,

and from his bed all suddenly he starts

as though he is made whole by some leech.

And day by day he began to enquire and seek

the truth of it, with all his energy:

and thus he brings on his destiny.

221.

Fortune, who all the permutation

of things controls (as is committed

to her through providence and disposition

of high Jove, as how kingdoms are fitted

to pass from folk to folk, or be unseated),

began to pluck the bright feathers of Troy

from day to day, till it was bare of joy.

222.

Amongst all this, the end and destiny

of Hector began to near him, in full might:

the fate that willed his soul to un-body

had shaped the means to drive it forth in flight:

against which fate helped him not to fight:

but on a day when to war he did intend,

that day, alas! he met his life’s end.

223.

Because of which I think that everyone

who takes up arms ought to bewail

the death of knight so noble, such a man.

For, while over some king he did prevail,

Achilles, suddenly, through his mail

and through his body pierced him in the strife

and thus this worthy knight was robbed of life.

‘Achilles vents his rage on Hector’

Domenico Cunego, after Gavin Hamilton (1766)

The Rijksmuseum

224.

For whom, as old books tell us,

was felt such woe, that of it tongue may not tell:

and especially the sorrow of Troilus,

who was next to him in worthiness, as well.

And in this woe Troilus began to dwell,

that what through sorrow and love and unrest,

he often every day bid his heart burst.

225.

But nonetheless, though he began to despair

and dreaded that his lady was untrue,

yet ever his heart would return to her:

and, as lovers do, he sought anew

to gain again Cressid, bright of hue.

And in his heart her he went excusing

that Calchas caused all her delaying.

226.

And often times he was in purpose set

himself like a pilgrim to disguise,

to see her: but he could not counterfeit

enough to be unknown by people wise

to it, nor find an excuse that would suffice

if he were recognised by Greeks there:

for which he would often weep many a tear.

227.

Yet he often wrote to her anew

full piteously (he did not fail through sloth),

beseeching her that, since he was true,

she should return again, and hold to her truth.

So that Cressid one day, out of ruth,

(I judge it so), touching this matter

wrote to him again as you may hear:

228.

‘Cupid’s son, example of all goodness,

O sword of knighthood, source of nobleness!

How may someone in torment and distress,

and lacking health, still send you gladness?

I heartbroken, sick, I joyless,

since you with me nor I with you may deal,

I may neither send you my heart nor heal.

229.

Your letter full, the paper all complaint,

has aroused my heart’s pity.

I have seen with tears all stained

your letter, and how you require me

to return again, which yet cannot be.

But why, lest this letter were found there,

I make no mention of now, out of fear.

230.

Grievous to me, God knows, is your unrest,

your hastiness, and the gods’ ordinance

it seems you will not take it for the best.

Nothing else is in your remembrance,

as I think, but only your own indulgence.

But do not be angered, I beseech:

for I delay on account of wicked speech.

231.

For I heard more than I hoped in the end

touching us two, how things might stand:

which I shall, by dissembling, amend.

And (don’t be angry) I was made to understand

that you were only toying with my hand.

But now no matter, I cannot in you guess

aught but all truth and all nobleness.

232.

I will come, yet things are so disjointed

as I stand now, that what year or day

it shall be is not yet appointed.

But in effect I pray you, as I may,

to let your good word and your friendship stay.

For truly, while my life may endure,

as a friend, of me you may be sure.

233.

Yet, that it’s short, I pray you not to take

ill, that which to you I write.

I dare not, where I am, letters make,

and never could compose as I might.

Still great matters men write in letters slight.

The intent is all, and not the letter’s space.

And now farewell: God have you in His grace.’

234.

Troilus thought this letter was all strange

when he had read it, and sorrowfully sighed.

He thought it was the beginning of a change:

but finally he could not believe she might

not do what she had promised him aright:

for he will think it evil in truth to leave

off loving, who loves well, though he grieve.