Geoffrey Chaucer

Troilus and Cressida

Book IV

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2001, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

1.

But all too short a time (alas the while!)

lasts such joy, thanks to Fortune

who seems truest when she beguiles,

and can to fools so her song attune

that she catches and blinds them, traitress soon:

and when a man is from her wheel thrown

then her laughs and grimaces are shown.

2.

From Troilus she began her bright face

to turn away, and took of him no heed,

but cast him clean out of his lady’s grace,

and on her wheel she set up Diomede:

at which my heart right now begins to bleed,

and now my pen, alas, with which I write

quakes for dread of what I bring to light.

3.

For how Cressid Troilus forsook,

or, at the least, how she was unkind,

must henceforth be the matter of my book,

as the folk write through which it comes to mind.

Alas that they should ever cause find

to speak harm of her: and if they lie,

they themselves are the guilty ones, say I.

4.

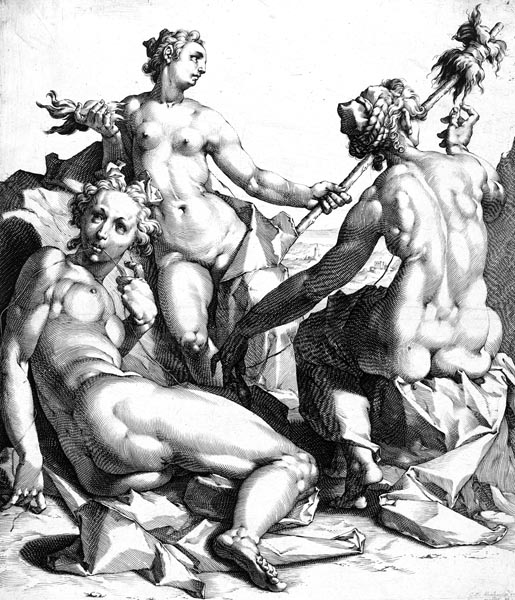

Oh you Holy Ones, Night’s daughters three,

who endlessly complain ever in painfulness,

Megaera, Alecto, and Tisiphone:

you cruel Mars too, father of Quirinus,

this fourth book help me finish, just,

so that the loss of life and love together

of Troilus may be fully showed here.

‘The Furies Encourage Althaea to Burn Meleager's Branch’

Bernard Picart, after Charles Le Brun, 1683 - 1710

The Rijksmuseum

‘The Discovery of Romulus and Remus, with the She-Wolf’

Bouzonnet Stella, Antoinette, 1641-1676

The New York Public Lbrary

5.

Lying, as a host, as I have said before this,

the Greeks, in strength, around Troy town,

it befell that when Phoebus shining is

upon the breast of Hercules’s Lion,

that Hector, with many a bold baron,

set on a day with the Greeks to fight,

as he tried to grieve them when he might.

‘Hercules Fighting the Nemean Lion’

Giovanni Antonio da Brescia, after Andrea Mantegna, after 1507

The Rijksmuseum

6.

I do not know how long it was between

this purpose, and the day of their intent:

but on a day well armed, bright to be seen,

Hector and many a worthy man forth went

with spears in hand and great bows bent:

and face to face, without delay or let,

their foemen in the field at once they met.

7.

All day long, with spears well ground,

with arrows, darts, swords, and maces fell,

they fight and bring horse and man to ground,

and with their axes out the brains spill.

But in the last assault, truth to tell,

the folk of Troy themselves so badly did

that being worsted, home by night they fled.

8.

On which day was taken Antenor,

not to mention Polydamas and Monesto,

Xanthippus, Sarpedon, Polynestor,

Polites, and the Trojan Lord Ripheo,

and other lesser folk like Phebuso.

So that for harm that day the folk of Troy

feared they had lost the greater part of joy.

9.

By Priam was given, at the Greeks request,

a time of truce, and then they began to treat

concerning exchange of prisoners, least and best,

and for the surplus to give ransoms great.

This thing was soon known in every street,

in the beseigers’ camp, town, everywhere,

and among the first it came to Calchas’s ear.

10.

When Calchas knew the treaty would hold,

in council, among the Greeks, he soon

began to crowd forth with lords old,

and sat down where he was wont to do:

and with a changed face begged of them a boon,

for love of God, to show him reverence,

to quiet their noise, and give him audience.

11.

Then he spoke thus: ‘Lo, my lords, I was

Trojan, as is known to you indeed:

and if you remember, I am that Calchas,

who, first of all, brought comfort in your need,

and told that you would certainly succeed.

For, without doubt, by you, it will be found,

Troy will be burnt and beaten to the ground.

12.

And in what form and in what manner of wise

to take the town, and all your ends achieve,

you have before now heard me advise:

this you know my lords, as I believe.

And as the Greeks were so beloved of me,

I came myself in my own person

to teach you how this thing could best be done.

13.

Giving no consideration to my rents,

or my treasure, but only to your ease,

thus I lost all my goods as I went,

thinking in this you lords to please.

But all that loss gives me no unease.

I undertake, as I hope for joy,

to lose for you all that I have in Troy.

14.

Save for a daughter that I left, alas,

sleeping at home when I from Troy parted.

O stern and cruel father that I was!

How could I have been so hard-hearted?

Alas! In her shift she should have departed.

For sorrow of which I will not live tomorrow

unless you lords take pity on my sorrow.

15.

Because I saw no chance before now

to free her, I have held my peace:

but now or never, if you choose so,

I may have her here right soon, with ease.

O help and grace! Among all Greece

take pity on this old wretch in distress,

since I bear for you all this heaviness!

16.

You now have captive and fettered in prison

Trojans enough: and if your will it be,

my child for one of them can have redemption.

Now for the love of God and generosity,

one of so many, alas, give him to me.

What point would it be this prayer to refuse,

since you’ll have folk and town soon, as you choose.

17.

On peril of my life I would not lie,

Apollo has told it to me faithfully:

I have also found it out by astronomy,

by lot, and also indeed by augury,

I dare well say the time is nigh

when fire and flame through all the town will spread,

and so shall Troy turn to ashes dead.

18.

For sure, Phoebus and Neptune both,

that built the walls of the town,

have always been with the folk of Troy so wrath,

that they will bring it to confusion

out of spite for King Laomedon:

because he would not pay their hire

the town of Troy shall be set on fire.’

19.

Telling his tale through, his beard so grey

humble in manner and in speech,

the salt tears from his two eyes play

in quick running streams down either cheek.

So long he did for succour them beseech

that to heal him of his sorrows true

they gave him Antenor without more ado.

20.

But who was glad then as Calchas though?

And to this end soon his requests laid

on those who would to make the treaty go,

and, exchanged for Antenor, them demanded

to bring home King Thoas and Cressid:

And when Priam his safe-guard sent

the ambassadors to Troy directly went.

21.

Told the cause of their coming, old

Priam, the king at once issued a call

so that a parliament he could hold:

to tell you the effects of which I shall.

The ambassadors were answered that all

the exchange of prisoners and their need

was acceptable, and could proceed.

22.

This Troilus was present in his place

when for Antenor was asked Cressid,

at which there was a swift change in his face

as if at those words he were well nigh dead:

but nonetheless against it he no word said

lest men should his affection spy:

with manly heart he endured his sorrow dry,

23.

And full of anguish and bitter dread

waited to hear what the lords would say:

and if they would grant (God forbid!)

the exchange of her, then his thoughts stray

to how to save her honour first, and what way

he might the exchange of her best prevent

and cast about for a means to his intent.

24.

Love made him eager for it to be denied

and he would rather die than that she go:

but Reason told him, on the other side,

‘Without her assent do not do so,

lest for your efforts she become your foe,

and say that through your meddling was revealed

the love between you which had been concealed.’

25.

Because of which he decided for the best

that though the lords wished that she be sent

he would let them grant what they wished,

and tell his lady first what was meant:

and when she had told him her intent,

thereafter he could work to prevent it

though all the world might strive against it.

26.

Hector, who had clearly the Greeks heard

and how for Antenor they would have Cressid,

began to oppose it and soberly answered:

‘Sirs, she is no prisoner,’ he said,

‘I know not who on you this charge has laid,

but for my part you may at once him tell,

it is not our custom women for to sell.’

27.

The people’s noise started up at once

as quick as the blaze of straw set on fire:

though misfortune willed in this instance

that they their own ruin did desire.

‘Hector,’ they said, ‘what spirit you inspires

to shield this woman thus and have us lose

Lord Antenor – a wrong path now you choose –

28.

who is so wise and so bold a baron?

And we have need of folk, as men may see:

he is one of the greatest in this town.

O Hector, let those fantasies be!

O King Priam, ‘they said, ‘thus say we,

that with once voice we part with Cressid’:

and to deliver Antenor they prayed.

29.

O Juvenal, lord! true is your sentence,

that folk so little know what they should yearn

for, that in their desire they see not the offence:

since clouds of error let them not discern

what’s for the best: and lo, here’s an example, learn.

This folk desire now deliverance

of Antenor, that will bring them to mischance:

30.

for he was afterwards a traitor to the town

of Troy. Alas, they ransomed him too fast.

O foolish world, behold your discretion:

Cressid, that never brought harm to pass,

shall have her bliss no longer last:

but Antenor, he shall come home to town,

and she shall go: so one and all set down.

31.

And so it was decreed by parliament

for Antenor to yield up Cressid,

and it was pronounced by the president,

though Hector’s ‘no’ was often repeated:

and finally, whoever it gainsaid,

it was for naught, it must be and it would,

for the majority in parliament said it should.

32.

Departing out of parliament everyone,

this Troilus, without more ado,

to his chamber sped him fast, alone

(unless there were a man of his or two,

whom he ordered out quickly to go,

because he would sleep, or so he said),

and hastily down on his bed he laid.

33.

And as in winter leaves are reft

one after another till the tree is bare,

so there is only bark and branches left,

so Troilus lies bereft of comfort there,

bound into the black bark of care,

likely to breed madness in his head,

so sorely he felt this exchange of Cressid.

34.

He rose up, and every door he shut,

and window also, and then this sorrowful man

on his bed’s side down him sat,

just like a lifeless image, pale and wan:

and in his breast the heaped woe began

to burst, and he to behave in this wise

in his madness as I shall describe.

35.

Just as a wild bull leaps without restraint,

now here, now there, pierced to the heart,

and roars of his death in complaint,

so he began about the chamber to dart,

striking his breast with his fists hard,

his head against the wall, his body on the ground

often he flung it, himself to confound.

36.

His two eyes, for pity of his heart,

stream down as swift streams play:

the high sobs of his sorrows start

to rob him of speech, he can only say:

‘O death, alas, why not let me pass away?

Accursed be the day on which nature

shaped me to be a living creature!’

37.

But after, when the fury and the rage

which his heart twisted and oppressed,

in time began somewhat to be assuaged,

upon his bed he laid him down to rest.

But then his tears began in his breast,

that it is a wonder that the body may suffice

to bear half this woe that I describe.

38.

Then he said thus: ‘Fortune, alas the while,

what have I done, what is then my guilt:

how can you, for pity, me so beguile:

is there no grace, and shall my life be spilt?

Shall Cressid be sent away because you will it?

Alas! How can you it in your heart find

to be so cruel to me and unkind?

39.

Have I not honoured you all my life,

as you well know, above the gods all?

Why will you me of joy thus deprive?

O Troilus, what may men now you call

but wretch of wretches, who out of honour fall

into misery, in which I will bewail

Cressid, alas, till my breath does fail?

40.

Alas, Fortune, if my life in joy

displeased you, and roused this foul envy,

why did you not from my father, king of Troy,

reft the life, or let my brothers die,

or slain myself who complain thus and cry?

I, world’s encumbrance, that may for nothing serve,

but be dying ever, and never death deserve.

41.

If Cressid alone to me were left,

I would not care where you might me steer:

and yet of her, alas, you have me bereft.

But evermore, lo, this is your manner,

to deprive a man of what to him is most dear,

to prove by that your sudden violence.

So am I lost, and there is no defence.

42.

O very lord of love, O God, alas,

who best knows my heart and all my thought,

what will my sorrowful life be in this case

if I forgo what I have so dearly bought?

Since you, Cressid and I, have fully brought

into your grace, and both our hearts sealed,

how can you suffer it to be repealed?

43.

Whatever I may do, I, while I may endure

to live on in torment, and cruel pain,

will of this misfortune and this misadventure,

alas, that I was born, indeed complain:

nor will I ever see it shine or rain,

but I will end, like Oedipus, in darkness,

my sorrowful life, and die in distress.

44.

O weary ghost, that flits to and fro,

why will you not fly from the woefullest

body that ever on the ground might go?

O soul lurking in this woe, leave your nest,

flee out of my heart, and let it rest,

and follow always Cressid your lady dear.

Your rightful place is no longer here.

45.

O twin woeful eyes, since your sport

was only to see Cressid’s eyes so bright,

what will you do but, to my discomfort,

avail me naught, and weep out your sight?

Since she is quenched who used to give you light,

in vain have I from this time two eyes, I say,

formed for me, since your virtue goes away.

46.

O my Cressida, O lady sovereign,

of this woeful soul that so cries,

who shall now give comfort to its pain?

Alas, no one: but when my heart dies,

my spirit, which towards you flies,

receive with favour, for it will ever you serve:

no matter that this body death deserve.

47.

O you lovers, who high upon the wheel

of Fortune are set, at good venture,

God grant that you find love as strong as steel,

and long may your life in joy endure.

But when you come by my sepulchre

remember that your fellow lies here,

for I loved also, though I unworthy were.

48.

O old, unwholesome, and treacherous man

(I mean Calchas), alas, what ails thee

to become a Greek though born a Trojan?

O Calchas, who my bane will be,

in a cursed time you were born, for me!

Would that blissful Jove might grant in his joy

that I had you where I wish you, in Troy!’

49.

A thousand sighs hotter than coals indeed

out of his breast one after another went,

mixed with new complaints, his woe to feed,

so that his woeful tears were never absent.

And shortly, his pains so him rent,

and he grew so exhausted, joy nor penance

could he feel, but lay there in a trance.

50.

Pandar, who in the parliament

had heard what every burgess and lord said,

and how it was all granted in one assent,

for Antenor, to yield up Cressid,

began well nigh to go out of his head,

so that, for woe, he knew not what he meant,

but in haste to Troilus he went.

51.

A certain knight, that at the time kept

the chamber door, undid it for him at once:

and Pandar, who full tenderly wept,

into the dark chamber, still as stone,

towards the bed began to softly go,

so confused he knew not what to say,

for very woe his wits were all astray.

52.

And with his face and look all distraught,

for sorrow of this, and with his arms folded,

he stood this woeful Troilus before,

and his piteous face began to behold.

But lord! So often did his heart turn cold,

seeing his friend in woe, whose heaviness

slew his heart, as he thought, from distress.

53.

This woeful man, Troilus, when he felt

his friend Pandar come in, him to see,

began, as the snow in the sun, to melt.

At which this sorrowful Pandar, from pity,

began to weep as tenderly as he.

And speechless thus the two were they,

that neither could one word for sorrow say.

54.

But at the last this woeful Troilus,

near dead of grief, began an outpour,

and with a sorrowful noise he said thus,

among his sobs and his sighs sore:

‘Lo, Pandar, I am dead and more:

have you not heard in parliament,’ he said,

for Antenor, how lost is my Cressid?’

55.

This Pandarus, full dead and pale of hue,

full piteously answered and said: ‘Yes,

I wish it were as false as it is true,

what I have heard, and know how it all is.

O mercy, God, who would have thought this?

Who would have thought that in a throw

Fortune would our joy overthrow?

56.

For in this world there is no creature

I think, who ever saw ruin hit

stranger than this through accident or venture.

But who may escape everything or divine it?

Such is this world: for so I define it:

no man should trust to find in Fortune

sole property, her gifts are communal.

57.

But tell me this, why you are so mad

with sorrow so? Why do you lie there in this wise,

since your desire completely you have had,

so that by rights it ought to suffice?

But I, that never felt in my service

a friendly face, or the gaze of an eye,

let me so weep and wail till I die.

58.

And beside all this, as you well know yourself,

this town is full of ladies all around,

and, to my mind, fairer than twelve

such as she ever was I’ll find in some crowd,

yes, one or two, without any doubt.

So be glad, my own dear brother:

If she be lost, we shall discover another.

59.

What, God forbid, always that pleasure chance

to be in one thing, and in no other might!

If one can sing, another well can dance:

if this one’s lovely, she is glad and light:

and this one’s fair, and that one reasons right.

Each for his own virtue is held dear,

both heron-hawk and falcon of the air.

60.

And then, as Zeuxis wrote who was full wise,

the new love often chases out the old

and a new case requires new advice.

Think then, save yourself, as you are told.

Such fire will by due process turn to cold:

for since it is but pleasure come by chance,

something will put it from remembrance.

61.

For as sure as day comes after night,

the new love, labour, or another woe,

or else seldom having her in sight

will an old affection overthrow.

And, for your part, you shall have one of those

comforts to abridge your bitter pain’s smart:

absence of her will drive her from your heart.’

62.

These words he said for the moment all

to help his friend, lest he for sorrow died:

doubtless to cause his woe to fall,

he cared not what nonsense he replied.

But Troilus, who nigh for sorrow died,

took little heed of anything he meant:

one ear heard it, at the other out it went:

63.

But at the last he answered, and said: ‘Ah, friend,

this medicine, or healed this way to be,

were well fitting if I were a fiend,

to betray her who is true to me.

I pray to God, this counsel never see

the light of day, rather let me die here

before I do as you would have me, sir.

64.

She that I serve, yes, whatever you say,

to whom my heart is devoted by right,

shall have me wholly hers till I die.

For, Pandarus, since I swore truth in her sight,

I will not be untrue though I might:

but as her man I’ll live and die, nor swerve

nor any other living creature serve.

65.

And where you say you will as fair find

as she, let be, make no comparison

to creature formed here of Nature’s kind.

O my dear Pandarus, in conclusion,

I will never be of your opinion

touching all this: so you I beseech

hold your peace, you slay me with your speech.

66.

You tell me that I should love another

all freshly new, and let Cressid go.

It lies not in my power, dear brother:

and though I might, I would not do so.

And can you play racquets to an fro

with love, nettle, dock, now this, now that Pandar?

Ill luck for her, who for your woe has care.

67.

Also, you do for me, you Pandarus,

as he that, when a man is woebegone,

comes to him readily and says thus:

“Think not of pain, and you will feel none.”

You must first transmute me to a stone,

and deprive me of my passions all

before you easily make my woe so fall.

68.

Death may well from my breast part

life, so long may last this sorrow of mine:

but from my soul shall Cressid’s dart

never be out, but down with Proserpine,

when I am dead, I will go dwell and pine:

and there I will eternally complain

of my woe and how we part again.

69.

You have made an argument, that’s fine,

how it should a lesser pain be

to forgo Cressid because she has been mine,

and live in ease and felicity.

Why do you gab so, who said this to me,

that “it is worse for him who from joy’s thrown

than if he had none of that joy ever known”?

70.

But tell me now, since you think it right

to change so in love, to and fro,

why have you not tried with all your might

to change from her who brings you all your woe?

Why will you not let her from your heart go?

Why will you not love another lady sweet

who might yet bring your heart to peace?

71.

If you in love have always had mischance

and cannot it out of your heart drive,

I, that have lived in joy and pleasant chance,

with her, as much as any creature alive,

how should I forget, and be so blithe?

Oh, where have you been hid so long in mew,

that you so well and formally argue?

72.

No, No, God knows, worth naught is all you said,

despite of which, regardless what may fall,

without more words, I will be dead.

O Death, who are the ender of sorrows all,

come now, since I so often on you call:

for happy is that death, truth to say,

that, oft invoked, comes and ends our pain.

73.

I know it well, while my life was at peace,

to stop you slaying me, I would have given hire:

but now your coming is to me so sweet,

that in this world I nothing so desire.

O Death, since with this sorrow I am on fire,

either at once let me in tears die drenched,

or with your cold stroke, my heat quenched.

74.

Since you slay so many in ways so various,

against their will, unasked-for, day and night,

do me, at my request, this service,

take now the world (and you do right)

from me, who am the woefullest knight

that ever was: for it is time I passed away,

since in this world I have no part to play.’

75.

At this Troilus’s tears began to distill,

like liquor from a retort full fast:

and Pandarus held his tongue still,

and down to the ground his eyes cast.

But nonetheless, thus thought he at the last:

‘What, by heaven! Rather than my friend die

yet I will somewhat more to this reply.’

76.

And said: ‘Friend, since you are in such distress,

and since you think my arguments to blame,

why not yourself help provide redress,

and with your manliness prevent this game?

Go take her: you cannot not do so: for shame!

and either let her from the town go

or keep her, and let foolishness alone.

77.

Are you in Troy and have no courage then

to take a woman who loves thee,

and would herself give her assent?

Now is this not foolish vanity?

Rise up now, and let this weeping be

and show you are a man, for in this hour

I will be dead or she will remain ours.’

78.

To this Troilus answered him full soft,

and said: ‘By heaven, beloved brother dear,

all this I have thought of myself, and oft,

and more things than you speak of here.

But why it cannot be, you shall well hear,

and when you have give me an audience

afterwards you can pronounce sentence.

79.

First, since (you know) this town is at war

through the taking of a woman by might,

it would not be suffered for me so to err,

as things stand now, or do what was not right.

I should have blame also from every knight

if I against my father’s ruling stood,

since she’s exchanged for the town’s good.

80.

I have thought also, if she were to assent,

to ask my father for her, of his grace:

yet this would accuse her to all intent,

since I know well I may not her purchase.

For since my father, in so high a place

as parliament, has her exchange sealed,

he will not for me see his decree repealed.

81.

Yet most I dread her heart to perturb

with violence, if I play such a game:

for if I were this to openly disturb

it must seem a slander on her name.

And I would rather die than her defame.

God forbid that I should not have

her honour dearer than my life to save.

82.

So am I lost, for aught that I can see,

for certain it is, since I am her knight,

I must hold her honour dearer than I to me

in any case, as a lover ought, of right.

So in my mind desire and reason fight:

desire to trouble her advises me clear,

and reason forbids it, as my heart fears.’

83.

Thus weeping, as if he could never cease,

he said: ‘Alas, how will I, wretch, fare?

For I feel my love always to increase,

and hope is always less and less, Pandar.

Increasing also the causes of my care,

so why does my heart not burst in my breast?

For in love like this there is but little rest.’

84.

Pandar answered: ‘Friend, you may, you see

do as you wish for my part: but if I were hot

and had your power, she should go with me

though all this town cried out on one note:

for all that noise I would not give a groat,

for when men have cried a while there is no sound.

A wonder never lasts more than nine nights in town.

85.

Probe not in reasoning so deep

or courtesy, but help yourself soon.

It is better that others weep,

and especially since you two be one.

Rise up, for, by my head, she will be gone:

and rather be in blame, a little, found

than die here like a gnat, without a wound.

86.

It is no shame to you, nor a vice,

to take her who you love most.

Perhaps she might think you were too nice

to let her go thus to the Greek host.

Think also, Fortune, as you know’st,

helps hardy men in their enterprise,

and scorns wretches for their cowardice.

87.

And though your lady might a little grieve,

you can your peace full well hereafter make.

But as for me, for certain, I can’t believe

that she would now it for an evil take:

why then for fear should your heart quake?

Think also how Paris has (who is your brother)

a love, and why should you not have another?

88.

And Troilus, one thing I dare swear,

is that Cressid, who is your love in chief,

now loves you as well as you do her,

God help me so, she will not think it grief,

if you do something to avoid mischief,

and if she wishes from you to pass,

then she is false: so love her less, alas.

89.

Therefore take heart, and think as a true knight.

Through love is broken everyday each law.

Now show your courage somewhat and your might,

have mercy on yourself for sure:

let not this wretched woe your heart gnaw.

But manfully risk all on a six or seven,

and if you die a martyr, go to heaven!

90.

I will myself be with you in your need,

though I and all my kin on the ground

may in a street, like dogs, lie dead, indeed.

Pierced through with many a wide and bloody wound,

in every case, I will a friend be found.

And if you choose to die here like a wretch,

adieu, the devil take him who cares so much!’

91.

At these words Troilus began to quicken,

and said: ‘Friend, have mercy: I assent:

but certainly you cannot prick me then,

nor can any pain so me torment,

that in any way it would be my intent,

in a word, though die I should,

to take her, unless she herself would.

92.

Why, so I mean too,’ said Pandar, ‘any day.

But tell me then, have you question of her made,

that you sorrow thus?’ And he answered: ‘Nay.’

‘Why then are you, ‘said Pandar, ‘so afraid

(who do not know she’ll be at all dismayed)

to take her, since you have not been there,

unless Jove whispered it in your ear?

93.

So, rise, as if naught were amiss, right soon,

and wash your face, and to the king wend,

or he may wonder where you are gone.

You must deceive him and others wisely then,

or, maybe, he will after you send

before you are aware: and in short brother dear,

be glad: and let me work at this matter.

94.

For I shall shape it that assuredly

you shall this night, sometime, in some manner,

come to speak with the lady privately:

and by her words and also by her cheer

you will soon perceive and hear

all her intent, and in this case the best:

and farewell now, for at this point I rest.’

95.

The swift rumour that false things

reports equally with the true,

was throughout Troy spread on ready wings,

from man to man, and made ever new,

how Calchas’s daughter, with her bright hue,

in parliament, without words more,

was given in exchange for Antenor.

96.

The which tale as soon as Cressid

heard, she who of her father never thought,

in this case, nor when he might die,

constantly of Jupiter besought

to send ill luck to whom the treaty brought.

But in short, lest that these tales true were,

she dare not ask anyone for fear.

97.

As one who had her heart and all her mind

set on Troilus, tied so wonderfully fast,

that all the world could not her love unbind

nor Troilus out of her heart cast,

she wished to be his, while her life should last,

and thus she burned both in love and dread

so knew not by what counsel to be led.

98.

But as men see in town and all about,

that of their friends women like to have sight,

so to Cressid of women came a crowd

in joyful sympathy, thinking it her delight,

and with their tales, hardly worth a mite,

these women, who in the city dwell

sit themselves down, and speak as I shall tell.

99.

Said one at first: ‘I am glad, truly,

because of it you will your father see.’

Another answered: ‘Well, I am not, I,

for all too little has she been in our company.’

Then said a third: ‘I hope, then, that she

will bring for us a peace on either side,

so, when she goes, Almighty God be her guide.’

100.

Those words and those womanish things,

she heard them just as though she absent were,

for, God knows, her heart on another thing is:

although her body sits among them there,

her attention is always elsewhere.

For Troilus completely her heart sought,

without a word, always of him she thought.

101.

These women, that thus think her to please,

on nothing began all their tales to spend:

such foolishness can afford her no ease,

as one who all this while burned

with other passion than they understand,

so that she almost felt her heart die

for woe and weariness of that company.

102.

Because of which she could no more restrain

her tears (they began so to well)

that were the signs of the bitter pain

in which her spirit was, and must dwell:

remembering from heaven into what hell

she was fallen, since she must forgo the sight

of Troilus, and sorrowfully she sighed.

103.

And those fools, sitting her about,

thought that she wept and sighed sore

because she should depart from that crowd

and never play with them any more,

and those who had known her before

saw her weep, and thought it naturalness,

and each of them wept also for her distress.

104.

And so they busily gave her comfort

for something, God knows, of which she little thought,

and with their tales to amuse her thought,

and to be glad they often her besought

but such an ease with this they her wrought

as much as a man is eased when he feels

that for a headache you scratch him on the heel.

105.

But after all this foolish vanity

they took their leave and home they went all.

Cressid, full of sorrowful pity,

went up into her chamber from the hall:

and on her bed she began as if dead to fall,

with the purpose from there never to rise:

and thus she wrought as I shall you describe.

106.

Her waving hair, that sunlit was of hue,

she rent, and then her fingers long and small

she wrung often and prayed God to show her rue,

and with death to heal her misfortunes all.

Her colour once bright, that now began to pall,

gave witness of her woe and her constraint:

and thus she spoke, sobbing with complaint.

107.

‘Alas!’ she said, ‘out of this region

I, woeful wretch and unfortunate sight,

born under a cursed constellation,

must go, and part from my knight.

Woe, alas, on that day’s light

on which I first saw him with eyes twain,

that causes me (and I him) all this pain!’

108.

At that the tears from her eyes two

fell down, as showers in April’s season:

her white breast she beat, and for woe,

cried on death with a thousand sighs then,

since he that used her woes to lighten

she must forgo, for which misadventure

she held herself as a lost creature.

109.

She said: ‘How will he do, and I also?

How should I live if from him I un-twin?

O dear heart, you that I love so,

who will that sorrow quench that you are in?

O Calchas, father, yours be all this sin!

O my mother, who was called Argive,

woe on the day that you bore me alive!

110.

To what end should I love and sorrow thus?

How should I, fish out of water, endure?

What is Cressid worth without Troilus?

How should a plant or living creature

live without its kind’s nurture?

To which a frequent proverb here I say,

that “rootless: green things must fall away.”

111.

I shall do thus: since neither sword nor dart

dare I handle, for their painful cruelty,

that day on which I from him depart,

if sorrow at that is not my death to be,

then shall no meat or drink come in me

till I my soul out of my breast un-sheath,

and so myself I would do to death.

112.

And Troilus, my clothes every one

shall be black in token, heart sweet,

that I am as if out of this world gone,

I, who used to bring you peace:

and in my Order, yes, till death me meet,

the observance ever, in your absence,

shall sorrow be, complaint, and abstinence.

113.

My heart, also the woeful ghost within,

I bequeath, with your spirit, to complain

eternally, for they shall not part again:

for though on earth we are parted, we twain,

yet in the fields of pity, beyond pain,

they call Elysium, we shall be together

as Orpheus and Eurydice his lover.

‘Orpheus and Eurydice’

Girodet-Trioson, Anne-Louis, 1767-1824, Gérard, François-Pascal-Simon, 1770-1837

The Getty Open Content Program

114.

Thus, my heart, for Antenor, alas,

as I think, I soon shall be exchanged.

But what will you do in this sorrowful case:

how will your tender heart this sustain?

Yet, my heart, forget this sorrow and pain,

and me also, for in truth say I,

if you fare well, I care not if I die.’

115.

How it could ever be read, or sung,

the complaint she made in her distress,

I know not: but as for me my poor tongue

if I tried to describe her heaviness,

would only make her sorrow seem less

than it was, and childishly deface

her high complaint, and therefore I beg grace.

116.

Pandar, who was sent by Troilus

to Cressid, as you have heard me say,

agreed that is was better thus,

and he glad to perform the task that day,

to Cressid, in a quite secret way,

where her torment and grief did rage,

came to tell all wholly his message.

117.

And found she had begun herself to treat

quite piteously, for with her salt tears

her breast, her face, bathed was full wet:

the long tresses of her sunlit hair,

unpinned, hung all about her ears:

which gave him notice that she desired

death’s martyrdom, that her heart required.

118.

When she saw him she began for sorrow at once

her tearful face between her arms to hide,

at which this Pandar was so woebegone,

that he could scarcely in that house abide,

as he felt pity for her on every side,

for if Cressid had complained deeply before

she began to complain a thousand times more.

119.

And in her bitter plaint then she said:

‘Pandarus first, of joys more than two,

was prime cause to me Cressid,

that have now been transmuted to cruel woe.

Should I then say to you “welcome” or no,

who first of all brought me to the ties

of love, alas, that ends in such wise?

120.

Does love end, then, in woe? Yes, or man lies,

and all worldly bliss, it seems to me,

the end of bliss, ever sorrow, occupies:

and who believes that not to be,

let him me, a woeful wretch, see,

who hate myself and my own birth curse,

feeling always from woe I go to worse.

121.

Who sees me, he sees all sorrow in one,

pain, torment, plaint, woe and distress.

Out of my woeful body harm is none

but anguish, languor, cruel bitterness,

trouble, pain, dread, fury, and sickness.

I think, indeed, from heaven tears rain

in pity for my bitter and cruel pain.’

122.

‘And you, my niece, full of discomfort,’

said Pandarus, ‘what do you think to do?

Surely some true regard to yourself you ought

to have? Why will you destroy yourself too?

Leave all this work, and take now heed to

what I say, listen with full intent

to this which, by me, your Troilus has sent.’

123.

Cressid turned then, a woeful face making

so that it was deathly her to see.

‘Alas!’ she said, ‘what words do you bring?

What will my dear heart say to me,

whom I dread never more to see?

Will he have plaints or tears before I wend?

I have enough, if for those he send.’

124.

She was such to see in her visage,

as is the one that men on a bier mind:

her face, like Paradise in its image,

was all changed to another kind.

The play, the laughter, men used to find

in her, and also her joys every one

were fled, and thus Cressid lies alone.

125.

Around her two eyes a purple ring

encircled in true token of her pain,

that to behold it was a deadly thing,

at which Pandar might not restrain

the tears from his eyes to rain.

But nonetheless, as best he might he said

from Troilus these words to Cressid.

126.

‘Lo, niece, I know you have heard how

the king with other lords, all for the best,

has set an exchange of Antenor for you,

which is the cause of this sorrow and unrest.

But how this thing does Troilus molest,

is what no earthly man’s tongue can say:

for very woe his wits are all astray.

127.

For all this we have so sorrowed, he and I,

it nearly wore us down until we were no more:

but through my counsel this day finally

he has from weeping learnt a little to withdraw:

It seems to me he desires, being unsure,

to be with you a night to devise

a remedy for this, if there is one anywise.

128.

This, short and plain’s the content of my message,

as far as my wits can comprehend:

for you, who are in such torment of grief’s rage,

won’t wish to hear the prologue extend:

and now you may an answer send.

And for the love of God, my niece dear,

leave off this woe before Troilus is here.’

129.

‘Great is my woe,’ she said, and sighed sore

as one that felt a deadly sharp distress,

‘but yet to me his sorrow is much more,

that love him better than he himself, I guess,

alas, through me he has such heaviness:

can he for me as piteously complain?

Truly, his sorrow doubles all my pain.

130.

Grievous to me, God knows, it is to part,’

she said, ‘but yet it is harder for me

to see the sorrow that afflicts his heart,

for well I know it will my bane be:

and I will die, for certain,’ then said she.

‘But bid him come, before death who me mistreats

drives out my spirit, that he in my heart beats.’

131.

These words said, she, on her arms two

fell prone and began to weep piteously.

Said Pandarus: ‘Alas, why do you so,

since you well know the time is close by

when he shall come? Rise, hastily,

that he you free of weeping thus shall find,

or you will make him lose his mind.

132.

For, if he knew you fared in this manner,

he would slay himself: and if I had known

this would be the fare, he’d not come here

for all the wealth that Priam may own.

For on what end he would determine soon,

that I know well, and therefore I still say,

leave off this sorrow or he will die today.

133.

And set yourself his sorrow to abridge

and not increase, dear niece, my sweet:

be rather to him the flat than the edge,

and with some wisdom, his sorrows greet.

What help’s it if your weeping fills the street,

or you both in salt waves are drowned?

Better a time of cure than sorrow’s sound.

134.

I mean this: when I him here bring,

since you are wise and both of one assent,

shape how you might prevent this going

or return again soon after you are sent:

women are wise in quick agreement.

And let’s see now how your wits avail,

and if I can help I shall not fail.’

135.

‘Go,’ said Cressid, ‘and, uncle, truly

I will do all I can myself to restrain

from weeping in his sight, and busily

to make him glad I will take great pain,

and of my heart search in every vein:

if to this hurt there may be found a salve

it shall not lack, for certain, on my behalf.

136.

Pandarus goes, and Troilus he sought,

till in a temple he found him alone,

like one who of his life no longer thought

but to the merciful gods every one

he prayed most tenderly and made his moan,

to send him soon out of this earthly place,

for he truly thought there could be no other grace.

137.

And in brief, the truth to say,

he was so fallen into despair that day

that for certain he prepared the way:

for this was his argument always:

he said he was truly lost, welaway –

‘For all that comes, comes of necessity:

therefore to be lost, it is my destiny.

138.

For certainly I know this well,’ he said

that the foresight of divine providence

has known always I would forgo Cressid,

since God sees all things, in all assurance,

and disposes of them, through his ordinance,

each according to their merits, to be,

as they shall come to pass, by destiny.

139.

But, nonetheless, whom shall I believe?

since there are great clerks, many a one,

that destiny through arguments conceive

and prove, and some say there is none,

but that free choice is given us everyone.

Oh welaway, so clever were clerks of old,

that I know not whose opinion to hold.

140.

For, so men say, if God sees all before,

and God may not be deceived, as we see,

then things must happen, whatever men have sworn,

as foreknowledge has seen them before to be.

Therefore I say that if from eternity He

has known our thoughts before and our deeds,

we have no free choice, as these clerks teach indeed.

141.

For no other thought, nor other deed also,

could ever be, but such as providence

(which cannot be deceived for evermore)

has known before, free of ignorance:

for if there might be a variance

that could escape God’s surveying,

He would not have prescience of what was coming:

142.

but that would make His then an opinion

uncertain, and not a steadfast foreseeing.

And certainly that would be a delusion,

that God should have imperfect knowing

just as we men, who have doubtful seeing.

But such an error upon God to guess

were false and foul and cursed wickedness.

143.

Also this is an opinion held by some

that have their heads full and smoothly shorn:

they say thus: that a thing is not to come

because God’s prescience has seen before

that it shall come: but they say because therefore

it must come therefore providence

knows it before, free of ignorance.

144.

And in this manner then necessity

reverses the matter once again:

for it is not necessary for it to be

that those things happen for certain

that are foreseen: but, as they maintain,

necessary that all things that befall

have for certain been foreseen, in all.

145.

I intend, although I labour in this,

to enquire which thing the cause of the other be:

as whether that the prescience of God is

the certain cause of the necessity

of things that come to be, as God may see:

or if necessity of things coming hence

is the certain cause of providence.

146.

But for now I do not intend showing

how the order of causes stands: but well know I

that it must be that the befalling

of things known beforehand, and certainly,

is necessary, even though it follows not thereby

that prescience makes the befalling necessary there

of the thing to come, be it foul or fair.

147.

For if a man sits there on a fallen tree,

then by necessity it behoves it

that your opinion truthful be

that knows or conjectures that he sits.

And furthermore now against it,

lo, so is the truth of the contrary,

as thus – now listen close for I will not tarry.

148.

I say that if the opinion of thee

is true because he sit, then I say this,

that he must be sitting, of necessity:

and so necessity in either surmise is,

for in him the necessity of sitting is, yes,

and in you necessity of truth: and thus forsooth

there must be necessity in you both.

149.

But, you may say, the man therefore

does not sit because your opinion is:

but rather because the man sat there before,

therefore your opinion is true, yes.

And I say, though the cause of truth of this

comes from his sitting, yet necessity

is interchangeable in him and thee.

150.

So, in the same way, with all sense,

I may well make, as it seems to me,

my reasoning of God’s providence

and of the things that come to be:

by which reasoning men may see

that those things that on earth befall,

by necessity come they all.

151.

For that a thing must come, yes,

means therefore it is foreseen in certainty,

and not that it comes because it foreseen is,

yet nevertheless it must be, necessarily,

that the thing to come be foreseen truly.

That is to say, things that foreseen be

happen indeed through necessity.

152.

And this suffices right enough, for certain,

to destroy our free choice, and our will:

and also now it is blasphemy, to say

that the falling out of things temporal

is the cause of God’s prescience eternal:

now truly that is a false sentence,

that things to come should cause his prescience.

153.

What could I be saying, in such a thought,

but that God foreknows the things to come

because they are to come, and else knows naught?

So I might think, that all things and some,

that have happened before and now are gone,

are the cause of that sovereign prescience

that foreknows all, free of ignorance.

154.

And, beside all this, I say this there-to,

that just as when I know there is a thing,

then that thing must necessarily be so,

so also, when I know a thing is coming,

so it must come: and thus the befalling

of things that are known before they arrive,

can not be evaded on any side.’

155.

Then he said thus: ‘Almighty Jove enthroned,

who know of all things the truthfulness,

take pity on my sorrow, and let me die soon,

or lead Cressid and I from this distress.’

And while he was in all this heaviness,

disputing with himself in this matter,

Pandarus came, and spoke as you may hear.

156.

‘O mighty God,’ said Pandarus, ‘enthroned,

whoever yet saw a wise man fare so?

Why, Troilus, what do you think to have done,

have you such desire to be your own foe?

What, by heaven, Cressid is not yet to go?

Why then desire to doom yourself in dread,

that in your head you even seem dead?

157.

Have you not lived many a year before

without her, and fared full well at ease?

Are you for her, and for no other born:

Has nature made you only her to please?

Let be, and think aright in your unease,

that in the dice as there fall chances,

just so in love come and go joy’s dances.

158.

And yet this is a wonder, most of all,

why you sorrow so, since you know not yet

touching her going, how that it will fall,

nor if she can herself prevent it.

You have not yet tested all her wit:

it’s time enough for a man his neck to bend

when it shall be cut off: sorrow as needs then.

159.

Therefore take heed of what I shall say:

I have spoken with her at length you see,

as was agreed between her and me,

and ever more I think thus, that she

has something in her heart’s privacy

with which she can, if I shall rightly read,

prevent all this of which you are in dread.

160.

For such my counsel is, when it is night

go you to her, and make of this an end:

and blessed Juno, in her great might,

shall, as I hope, her grace to us send.

My heart says for certain she shall not wend,

and therefore let your heart awhile rest

and hold your purpose, that is the best.’

161.

This Troilus answered and sighed sore:

‘You speak right well, and I will do so’:

and he added what he wished to say more.

And when it was time for him to go

full privately himself, without more ado,

he came to her as he used to do:

and how they wrought I shall tell you too.

162.

True it is, that when they first meet

so the pain in their hearts begins to twist,

so that neither might the other greet:

but they embraced each other, and after kissed.

Which was the most woeful or the least

they knew not, nor could they one word bring

forth as I said before, for woe and sobbing.

163.

The woeful tears that they let fall

were as bitter and out of nature’s kind,

through pain, as is aloe wood or gall.

Such bitter tears wept not, as I find,

the woeful Myrrha through the bark and rind:

so in this world there is not so hard a heart

that it would not have pitied their pain’s smart.

‘Cinyras Discovers that he has Slept with his Daughter Myrrha’

Crispijn van de Passe (II), after Pieter Lastman, Jan Tengnagel, c. 1636 - 1670

The Getty Open Content Program

164.

But when their woeful weary ghosts again

had returned to where they ought to dwell,

and somewhat to weaken began the pain,

through long complaint, and to ebb began the well

of their tears, and the heart un-swell,

with broken voice, all hoarse with crying, Cressid

to Troilus these words she said:

165.

‘O Jove, I die, and mercy I beseech!

Help, Troilus!’ And, at that, her face

on his breast she laid and lost her speech,

her woeful spirit from its proper placing

at every word, on the point of passing.

And so she lies there with hue pale and green,

who was once fresh and fairest to be seen.

166.

This Troilus, who began her to behold,

calling her name (and she lay as if dead,

without answering), and felt her limbs cold,

(her eyes thrown upward in her head),

this sorrowful man knew not what instead

he might do, but oft her cold mouth kissed.

Whether he was woeful, God and he know this.

167.

He rose, and straight her out he laid:

for sign of life (for aught he can or may)

he can nowhere find in Cressid,

so that his song is often ‘welaway.’

But when he saw that speechless she lay,

with sorrowful voice and heart of bliss all bare

he said that she was gone from the world there.

168.

So after he had long for her complained,

wrung his hands, and said what was to say,

and with his salt tears her breast had stained,

he began to wipe those tears away,

and piteously for her soul began to pray,

and said: ‘O Lord, who are set on your throne,

have pity on me also, for I shall follow her soon.

169.

She was cold, and without sensation,

for aught he knew, for breath he felt none:

and this was to him a pregnant confirmation

that she was forth out of this world gone:

and when he saw there was no more to be done,

he began to dress her limbs in such manner

as men do those who are laid on bier.

170.

And after this, with stern and cruel heart,

his sword at once out of his sheath aright

he drew to slay himself, however it smart,

so that his soul her soul to follow might,

wherever the doom of Minos might indite:

since Love and cruel Fortune did not will

that in this world he should live still.

‘Scylla en Minos’

Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1602 - 1607

The Rijksmuseum

171.

Then said he thus, full of high disdain:

‘O cruel Jove, and you, Fortune adverse,

this is the whole, that falsely have you slain

Cressid, and since you can do me no worse,

fie on your power and works so diverse.

Thus cowardly you shall me never win:

no death shall part me from my lady then:

172.

For I this world (since you have slain her thus)

will leave, and follow her spirit low or high:

never shall lover say that Troilus

dared not, for fear, with his lady to die:

for certain I will bear her company.

But since you will not suffer us to live here,

yet allow our souls to be together there.

173.

And you, city that I leave in woe,

and you, Priam, and brothers here,

and you, my mother, farewell, for I go:

and Atropos make ready my bier!

And you, Cressid, O sweet heart dear,

receive now my spirit,’ with a sigh,

with sword at heart ready to die.

‘Three Fates’

Jan Harmensz. Muller, after Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem, 1587 - 1591

The Rijksmuseum

174.

But, as God wished, from her swoon she did

recover, and began to sigh, and, ‘Troilus!’ cried:

and he answered: ‘Lady mine, Cressid,

live you yet?’ and let his sword down glide.

‘Yes, my heart, thanks be to Cupid!’ she sighed.

And at that she began more deeply to sigh,

and he began to comfort her as best he might:

175.

took her in his two arms, and kissed her oft,

and to comfort her set his best intent:

at which her ghost, that flickered aloft,

into her woeful heart again it went.

But at the last, as her glance bent

aside, at once his sword she spied,

as it lay bare, and began with fear to cry.

176.

And asked him why he had it taken:

and Troilus at once the cause her told,

and how himself with it he would have slain.

At which Cressid began him to behold,

and began him in her arms to quickly fold,

and said: ‘O mercy, God, lo, such a deed!

Alas, how near death we both were, indeed.

177.

What if I had not spoken, by God’s grace it was,

you would have slain yourself,’ said she.

‘Yes, certainly’: and she answered: ‘Alas!

for by the same God that made me

I would not a furlong longer seek to be,

after your death, not to be crowned queen

of all the lands where the sun casts its sheen.

178.

But with this same sword that is here

I would have slain myself,’ she said, ‘Oh

stop! for we have made enough of this,

and let us rise and straight to bed go,

and there let us speak of our woe.

For by the lamp that I see burn intense,

I know right well that day is not far hence.

179.

When they were in their bed, in arms embraced,

it was not like the nights they had before:

for piteously each the other faced

as they that had all their bliss lost and more,

bewailing ever the day that they were born,

till at the last this sorrowful one, Cressid,

to Troilus these very words said:

180.

‘Lo, my heart, you know this well,’ said she,

‘that if anyone at their woe always complains,

and seeks not how they might helped be,

it is but folly and increase of pain.

And since that we are here assembled again,

to find a remedy for the woe we’re in

it were time enough to begin.

181.

I am a woman, so you know full well

that I have intuitions suddenly,

so while this one is hot, I will tell.

I think thus, that neither you nor I

ought to show half this woe, sensibly,

since there is art enough to redress

what is amiss, and lift this heaviness.

182.

Truth is, the very woe that we are in,

for aught I know, for no reason is

but because we have to part again.

Considering all, there is no more amiss.

But what is then a remedy for this,

why that we set ourselves soon to meet.

That is all, my dear heart sweet.

183.

Now that I shall easily bring it about

that I come again soon after I go,

I do not have a shadow of a doubt,

for certainly within a week or two

I shall be here: and that it shall be so

in all justice, and in words few,

I can you easily a heap of ways show.

184.

Because of which I’ll not make a long sermon,

for time once lost will not recovered be,

but I will go straight to my conclusion

(and the best one, for aught that I can see).

And, for the love of God, forgive me

if I speak anything that gives your heart unrest,

for truly I speak it for the best.

185.

Making always a protestation

that now these words that I shall say

are only to explain my proposition

to find for our help the best way.

And do not take it otherwise, I pray:

For, in effect, whatsoever you command,

I will do, without questioning the demand.

186.

Now, listen to this, you well understand

that my going is decreed by parliament

so firmly, that we cannot it withstand

for all the world, in my judgment.

And since there is no arrangement

to help stop it, let it pass from mind,

and let us try a better way to find.

187.

The truth is that to part us two again

will torment us and cruelly annoy:

but he must sometimes feel the pain

who serves Love, if he would have the joy.

And since I’ll be no further from Troy

that I can ride again in half a morrow,

it ought to be less cause to us of sorrow.

188.

So, as I shall not be hid as in mew,

day by day, my own heart dear

(since you know well there is a truce)

you will all the news of my state hear.

And before the truce is done I will be here,

and then you will have Antenor won

and me also: be glad now, if you can.

189.

And think like this: “Cressid is now gone,

but what! she will return quickly again”:

and when alas? by God, lo, right soon,

before ten days, this dare I maintain.

And then as before we’ll be right as rain,

so that we shall together ever dwell,

that all the world might not our bliss tell.

190.

I see that often, where we are now,

for the best, our counsel to hide,

you speak not with me nor I with you

a fortnight: nor see you walk or ride.

May you not ten days then abide,

for my honour, in such a venture?

If not there’s little that you can endure.

191.

You know also that all my kin are here,

unless it be my father, and too

all my other wealth, all together,

and namely, my dear heart, you,

of whom I would not lose the view

for all this world, as wide as it has space,

or else let me never see Jove’s face.

192.

Why think you that my father, in this wise,

so desires to see me, but for dread

lest in this town folk me despise

because of him, for his unhappy deed?

What does he know of the life I lead?

If he knew how well in Troy I fare,

for my going we’d have no need to care.

193.

You see that every day, and more and more,

men treat of peace, and it supposed is

that we the queen Helen will restore,

and the Greeks restore what we miss.

So even if there were no comfort but this,

that men propose peace on every side,

you should with an easier heart abide.

194.

For if there is a peace, my heart dear,

the nature of the peace must needs drive

men to communication together,

and to and fro also to ride and go as blithe

all day, and thick as bees flown from a hive,

and every one have liberty to live

where he best wishes, without needing leave.

195.

And even if of peace there is none,

yet here (though the peace never were)

I must return: for where would I be gone,

or by what mischance should I dwell there

among those men of arms ever in fear,

so that, as God my soul may lead,

I cannot see why you should be afraid.

196.

Have here another thought, if so it be

that all these things do not you suffice:

my father, as you know well, indeed,

is old, and covetousness is old age’s vice.

And I right now have found the device,

without a net, where I shall have him pent:

and listen now, if you will assent.

197.

Lo, Troilus, men say full hard it is

the wolf filled and the sheep whole to have:

that is to say that men often, in this,

must spend a part, the remnant to save:

for always with gold men may the heart engrave

of him in whom covetousness is a vice,

and what I plan I shall to you describe.

198.

The goods that I have in this town

I will take to my father and say

that out of trust and for their salvation

they are sent from a friend of his today.

The which friends fervently him pray

to send for more, and that hastily

while the town stands thus in jeopardy.

199.

And that will be a huge quantity,

so I will say, but lest folk it espy,

it may be sent by no one but me:

I shall also tell him, if peace arrived,

the friends that I have on every side

near the Court, to cause the wrath to abate

of Priamus, and let him return to grace.

200.

So, what with one thing and another, sweet

I shall enchant him so with my discourse,

that he will think his soul in heaven complete.

For all Apollo, or his servants’ laws,

or calculation, are not worth two straws:

desire for gold shall his soul so blind,

I will achieve the end I have in mind.

201.

And if by divination he tried to weave

a tale that I lie, I certainly have planned

to trouble him, and pluck him by the sleeve

while divining, and take a stand

that he does not the gods well understand,

for gods speak in amphibologies,

and for one truth they tell twenty lies.

202.

Also fear first found the gods, I suppose,

so I will say, and that his coward heart

made him mistake the god’s text, who knows,

when he, for fear, did our Delphic shrine depart.

And, if I don’t make him soon, by my art,

convert to my advice in a day or two,

to have me put to death I’ll invite you.’

203.

And truly, and well written down I find,

that all this thing was said with good intent,

and that her heart was true and kind

towards him, and she spoke as she meant,

and nearly died of woe when she went,

and was of purpose ever to be true:

so they wrote who of her actions knew.

204.

This Troilus, with heart and ears heard

all this thing discussed to and fro:

and truly it seemed to him he had

the same opinion, but yet to let her go

his heart misgave him ever so.

But finally he compelled his heart to rest,

and trusted her, and took it for the best.

205.

At which the great fury of his penance

was quelled with hope, and them between

began, for joy, the amorous dance,

and, as the birds when the sun gleams

delight in their song in the leaves green,

just so the words that they spoke together

delighted them and gave their hearts clear weather.

206.

But nonetheless the going of Cressid,

for all the world, would not leave his mind,

so that often he piteously prayed

that in her promise he might her true find,

and said to her: ‘Certainly, if you are unkind,

and do not come on the day set to Troy,

I will have nor honour, health or joy.

207.

For as truly as the sun will rise tomorrow,

(and, God, so may Thou me, woeful wretch,

bring to peace out of this cruel sorrow),

I will slay myself if you linger much.

And though my death’s not worth a lot as such,

yet before you cause me so to smart,

rather dwell here, my own sweetheart.

208.

For truly, my own lady dear,

those clevernesses I hear you declare,

are likely to all fail together.

For thus men say: “one thing thinks the bear,

another thing completely thinks his master.”

Your father’s wise, and it is said, from dread,

“The wise may be outrun, but not outwitted.”

209.

It is hard to feign a limp, and not be spied

by a cripple, since he knows the craft.

Your father is, in cunning, Argus-eyed,

for all that of his treasures he’s bereft:

he has plenty of his old cunning left,

you will not blind him, for all that’s in your head,

nor feign with skill enough, that is my dread.

‘Mercury and Argus’

Schelte Adamsz. Bolswert, after Jacob Jordaens (I), 1596 - 1659

The Rijksmuseum

210.

I know not if peace shall come to pass beside:

but peace or not, in earnest or in game,

I know, since Calchas on the Greek’s side

has been once, and foully lost his name,

he dare come here no more out of shame:

because of which, that way, for aught I see,

to trust in that, is but a fantasy.

211.

You will also find your father raise the matter

of your marrying: and as he can preach,

he will praise so some Greek and well flatter,

that he will ravish you with his speech,

or compel you by force, as he shall teach.

And Troilus, on whom you have no ruth

will innocently die so, in his truth.

212.

And besides all this, your father will despise

us all, and say this city is but lost,

and that the siege will never, in his eyes,

be raised, because the Greeks have all so sworn,

till we are slain, and down our walls are torn.

All this he’ll make you with his words fear,

so that I dread now you will remain there.

213.

You will see too many a lusty knight,

among the Greeks, full of worthiness:

and each of them with heart, wit and might

to please you will go about love’s business,

that you will grow tired of the roughness

of us simple Trojans, unless ruth

makes you relent, or your power of truth.

214.

And this is so grievous to me to think,

that from my breast it will my soul rend:

nor indeed into my mind could ever sink

any good opinion of it, if you went:

because your father’s cunning will us end.

And if you go, as I have said before,

then think me dead, I will soon be no more.

215.

So that with humble, true and piteous heart

a thousand times for mercy to you I pray:

take pity on my bitter pain’s smart,

and do somewhat as I to you now say,

and between us two let’s steal away:

and think that it is folly when men choose,

to chance the substance they may forever lose.

216.

I mean this, that since before the day

we can steal away and be together so,

what sense is there in making an assay

(in case you do to your father go)

of whether you can return or no?

Thus I mean, that it would be great folly

to put that security in jeopardy.

217.

And vulgarly to speak of wealth and substance,

of treasure we may carry in its stead

enough to live in honour and indulgence

until the time that both of us are dead.

And thus we may free ourselves of this dread:

for every other way you can afford,

my heart, indeed, may not with it accord.

218.

And certainly not dread poverty,

for I have kin and friends elsewhere,

so though we come in our bare shirts, we

would lack neither gold nor gear,

but be honoured while we dwell there.

And let us go soon, for, as is my intent,

this is the best for us, if you will assent.’

219.

Cressid, with a sigh, right in this wise

answered: ‘Well, my dear heart true,

we well may steal away as you advise,

and find such unprofitable ways new:

but afterwards sorely we will it rue.

And as God may help in my greatest need,

causelessly you suffer this dread, indeed.

220.

For the very day that I (through cherishing

or fear of father, or for any other thing, delight

in pleasure, or rank, or wedding)

am false to you, my Troilus, my knight,

Saturn’s daughter, Juno, through her might,

maddened as Athamas, send me to dwell

eternally in Styx, the pit of hell!

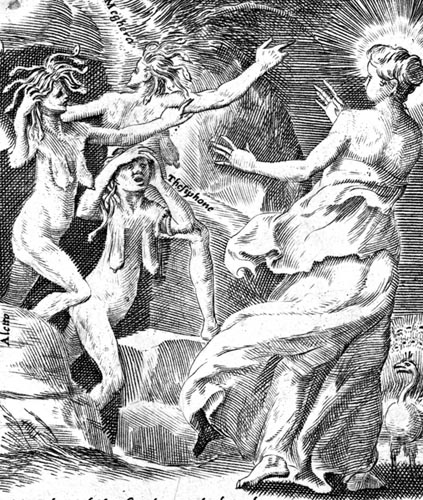

‘Juno Descends into Hades to ask the Furies to drive Athamas Mad’

Giulio Bonasone, 1501 - 1580

The Rijksmuseum

221.

And this, by every god celestial,

I swear to you, and also each goddess,

by every nymph and deity infernal,

by satyrs and fauns, greater ones and less

(that are the demi-gods of wilderness):

and Atropos my thread of life shall break

if I be false: now trust me, for your sake.

222.

And you Simois, that straight as an arrow, clear

through Troy run ever downward to the sea,

bear witness to this word that is said here,

that on that day that I untrue be

to Troilus, my own heart free,

you shall return backward to your well,

and I with body and soul sink to hell!

223.

But when you say that we away should go

and leave all your friends, God forbid

that for any woman you should do so,

and especially since Troy has now such need

of help: and also of another thing take heed,

if this were known, my life were in the balance,

and your honour: God shield us from mischance!

224.

And if peace is afterwards displayed,

as mirth comes after anger every day,

why lord! sorrow and woe you would have made,

so that you’d not dare return for shame.

And before you so risk your name

be not too hasty with your heated airs,

for a hasty man never wants for cares.

225.

What do you think the people all about

would say of it? That’s an easy one to read!

They would say, and swear it, without doubt,

that it was not love that drove you to this deed,

but voluptuous lust and coward fear, indeed.

So would be lost, truly, my heart dear,

all your honour that shines now so clear.

226.

And also think of my pure honesty

that flowers yet, how I would it rend,

and with what filth it would spotted be

if I were with you in this way to wend,

not, though I lived to the world’s end,

should I my good name ever again win:

so I were lost, and that were pity and sin.

227.

And therefore cool with reason all this heat:

men say: “the patient man conquers,” and “he,”

“who will have joy, must let joy go,” also.

So make a virtue of necessity

by patience, and think that lord is he

of Fortune ever that naught from her expects:

and she defeats no man but a wretch.

228.

And trust in this, for certain, heart sweet,

before Phoebus’s sister, Diana, her gleam

passes from Aries now, the Lion to greet,

I will be here without a doubt. I mean

(so help me Juno that is heaven’s queen)

on the tenth day, unless death me assail,

I will see you again without fail.’

‘Diana’

Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1611 - 1637

The Rijksmuseum

229.

‘And now, so this be true,’ said Troilus,

‘I will suffer it till the tenth day,

since I see we needs must have it thus:

but, for the love of God, if still we may,

let us steal secretly away,

for ever one, so as to live at rest:

my heart says it will be for the best.’

230.

‘O merciful God! What life is this?’ said she,

‘alas, you slay me thus with very woe.

I see well now, that you mistrust me,

for by your words I see it to be so.

Now for the love of Cynthia’s bright glow,

do not mistrust me causelessly, for ruth,

since I have sworn myself to you in truth.

231.

And think, that truly it is sometimes wise

to spend some time, in order time to win:

nor, by heaven, am I lost yet to your eyes.

Though we’ll be parted a day or two again,

drive out the fantasy you have within,

and trust me, and leave off your sorrow,