Horace: The Satires

Book I: Satire II

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- BkISatII:1-22 When it comes to money men practise extremes

- BkISatII:23-46 And in sexual matters some prefer adultery

- BkISatII:47-63 While others avoid wives like the plague

- BkISatII:64-85 The sin’s the same, but wives are more trouble

- BkISatII:86-110 Wives present endless obstacles

- BkISatII:111-134 No married women for me!

BkISatII:1-22 When it comes to money men practise extremes

The guild of girl flute-players, the quacks who sell drugs,

The beggars, the jesters, the actresses, all of that tribe

Are sad: they grieve that the singer Tigellius has died:

He was so generous they say. But this fellow over here,

Afraid of being a spendthrift, grudges his poor friend

Whatever might stave off the pangs of hunger and cold.

And if you ask that man there why, in his greedy ingratitude,

He’s squandering his father’s and grandfather’s noble estate

Buying up gourmet foodstuffs with money he’s borrowed,

It’s so as not to be thought a mean-spirited miser.

By some men that’s praised and by others condemned.

While Fufidius, rich in land and the money he’s lent,

Afraid of earning the name of a wastrel and spendthrift,

Charges sixty per cent per annum, docked in advance,

And presses you harder the nearer you are to ruin.

He gathers in debts from young men with harsh fathers

Kids who’ve just taken to wearing the toga: ‘Great Jove’

All cry on hearing it, ‘but surely he spends on himself

In line with his earnings? Well, you’d scarcely believe

How bad a friend he is to himself. That father who exiled

His son, whom Terence’s play depicts as living so

Wretchedly, never tortured himself more than he does.

‘Jove and the Gods’

Georg Andreas Wolfgang, the Elder (German, 1631 - 1716)

National Gallery of Art

BkISatII:23-46 And in sexual matters some prefer adultery

If you ask now: ‘What’s your point in all this? Well,

In avoiding one vice a fool rushes into its opposite.

Maltinus ambles around with his tunic hanging down:

Another, a dandy, hoists his obscenely up to his crotch.

Rufillus smells of lozenges, and Gargonius of goat.

There’s no happy medium. Some will only touch women

Whose ankles are hidden beneath a wife’s flounces:

Another only those who frequent stinking brothels.

Seeing someone he knew exit from one, Cato’s

Noble words were: ‘A blessing on all your doings, since

It’s fine when shameful lust swells youngsters’ veins

For them to wander down here, and not mess around

With other men’s wives.’ ‘I’d hate to be praised for that,’

Says Cupiennius though, an admirer of white-robed snatch.

If you wish bad luck on adulterers, it’s worth your while

To listen how they struggle in every direction,

And how their pleasure is marred by plenty of pain,

And how in the midst of cruel dangers it’s rarely won.

One man leaps from a roof: another, flogged, is hurt

To the point of death: another in flight falls in with

A gang of fierce robbers: a fourth pays gold for his life,

A fifth’s done over by lads, it’s even happened

That a husband with a sword’s reaped the lover’s

Lusty cock and balls. ‘Legal’ all cried: Galba dissenting.

BkISatII:47-63 While others avoid wives like the plague

How much safer it is to trade in second class wares,

I mean with freedwomen, whom Sallust runs after

As insanely as any adulterer. Yet if he wished

To be kind and generous in accord with his means,

With reason’s prompting, as modest liberality allows,

He’d give just enough, not what meant shame and ruin

For himself. But no he hugs himself and admires himself

And praises himself for it, because: ‘I never touch wives.’

As Marsaeus, Origo’s lover, who gave the house and farm

He inherited to an actress, once said: ‘May I never

Have anything to do with other men’s wives.’

But you have with prostitutes and actresses, and so

Your reputation suffers more than your wealth. Or

Is it enough for you to avoid the tag, but not what

Causes harm on every side? To throw away a good name,

And squander an inheritance, is always wicked.

What matter whether you sin with a wife or a whore?

BkISatII:64-85 The sin’s the same, but wives are more trouble

Villius, Sulla’s ‘son-in-law’, suffered enough and more

Because of Fausta – he, poor wretch, deceived by her name –

He was punched, and attacked with a sword, and shown

The door, while his rival Longarenus was there inside.

In the face of such problems if a man’s lust were to say:

‘What are you up to? In all my wildness did I ever insist

On a cunt in a robe descended from some mighty consul?’

Would he really reply: ‘But she’s a great man’s daughter.’

If you’d only manage things sensibly, and not confuse

What’s desirable with what hurts you, how much wiser

The opposite advice Nature, rich in her own wealth, gives.

Do you think it’s irrelevant whether your problems

Are your fault or fate’s? Stop angling for wives if you don’t

Want to be sorry, you're more likely to gain from it pain

And effort, rather than reaping the fruits of delight.

Cerinthus, her leg is no straighter, her thigh no softer,

Among emeralds or snowy pearls, whatever you think,

And it’s often better still with a girl in a cloak.

At least she offers her goods without disguise, shows

What she has for sale openly, won’t boast and flaunt

Whatever charms she has, while hiding her faults.

BkISatII:86-110 Wives present endless obstacles

It’s like rich men buying horses: they inspect them

When they’re blanketed, so that if, as often happens,

The hoof supporting a beautiful form is tender, the buyer

Gazing isn’t misled by fine haunches, long neck, small head.

In this they’re wise: don’t study her bodily graces

With Lynceus’ eyes, yet blinder than Hypseae

Ignore her imperfections. ‘Oh, what legs, what arms!’ True,

But she’s narrow-hipped, long-nosed: short waist, big feet.

With a wife you can only get to see her face:

Unless she’s a Catia long robes hide the rest.

If you want what’s forbidden (since that is what excites you),

What walls protect, there’s a host of things in your way,

Bodyguards, closed litters, hairdressers, hangers-on,

A dress-hem down to her ankles, a robe on top,

A thousand things that stop you gaining an open view.

With the other type, no problem: You can see her almost

Naked in Coan silk, no sign there of bad legs or ugly feet:

And check her out with your eyes. Or would you rather

Be tricked, parted from your cash before the goods are

Revealed? Callimachus says how ‘the hunter chases

The hare through deep snow, but won’t touch it at rest’,

Adding: ‘That’s what my love is like, since it flies past

What’s near, and only chases after what runs away.’

Do you hope with such verses as those to keep

Pain, passion, and a weight of care from your heart?

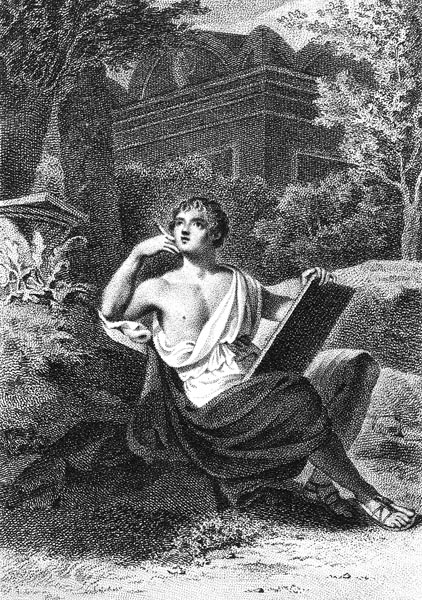

‘The Greek poet Callimachus’

Lambertus Antonius Claessens (Belgian, 1763 - 1834)

The Rijksmuseum

BkISatII:111-134 No married women for me!

Wouldn’t it be better to ask what boundaries Nature

Sets to desire, what privations she can stand and what

Will grieve her, and so distinguish solid from void?

Do you ask for a golden cup when you’re dying

Of thirst? Do you scorn all but peacock, or turbot

When you’re starving? When your prick swells, then,

And a young slave girl or boy’s nearby you could take

At that instant, would you rather burst with desire?

Not I: I love the sexual pleasure that’s easy to get.

‘Wait a bit’, ‘More cash’, ‘If my husband’s away’, that girl’s

For the priests, Philodemus says: requesting, himself,

One who’s not too dear, or slow to come when she’s told.

She should be fair and poised: dressed so as not to try

To seem taller or whiter of skin than nature made her.

When a girl like that slips her left thigh under my right,

She’s Ilia or Egeria: I name her however I choose,

No fear, while I fuck, of husbands back from the country,

Doors bursting, dogs howling, the whole house echoing

With the sound of his knocking, the girl deathly pale,

Leaping the bed, her knowing maid shouting afraid

For her limbs, the adulteress for her dowry, I for myself.

Nor, clothes awry, of having to flee bare-foot, scared

For my cash, my skin, or at the very least my reputation.

It’s bad news to be caught: even with Fabio judging.

End of Book I Satire II