Federico García Lorca

Doña Rosita the Spinster and the Language of Flowers

(Doña Rosita la soltera o el lenguaje de las flores)

Act I

A Granadine poem of the 19th Century, divided into several gardens with scenes of song and dance - 1935

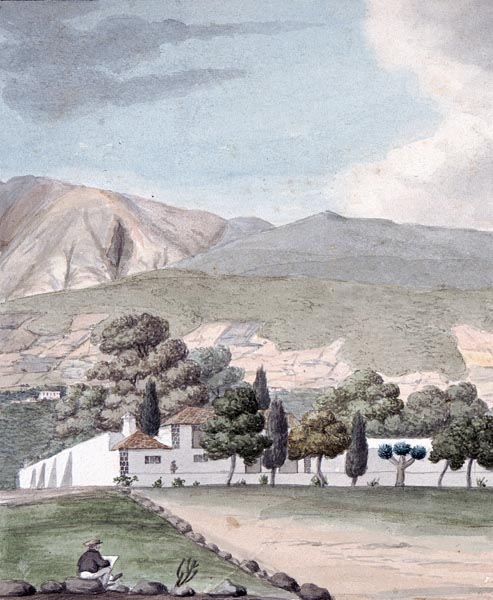

‘The Botanical Garden near Port Orotava, Tenerife’

Alfred Diston, active 1818–1829

The Yale Centre for British Art

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright, All Rights Reserved. Made available as an individual, open-access work in the United Kingdom, 2008, via the Poetry in Translation website. Published as part of the collection ‘Four Final Plays’, ISBN-10: 1986116565, March 2018.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply. Permission to perform this version of the play, on stage or film, by amateur or professional companies, and for commercial purposes, should be requested from the translator.

Please note that Federico García Lorca's original, Spanish works may not be in the public domain in all jurisdictions, notably the United States of America. Where the original works are not in the public domain, permissions should be sought from the representatives of the Lorca estate, Casanovas & Lynch Agencia Literaria.

Contents

Cast List

Doña Rosita

The Nurse/Housekeeper

The Aunt

First Girl/Coquette

Second Girl/Coquette

Third Girl/Coquette

First Spinster

Second Spinster

Third Spinster

The Spinsters’ Mother

First Ayola daughter

Second Ayola daughter

The Uncle

The Nephew

The Professor of Economics/Señor X

Don Martín

A Boy

Two Working Men

A Voice

Act I

(A room with an exit to a conservatory)

Uncle And my seeds?

Nurse They were there.

Uncle Well, they’re not now.

Aunt Hellebores, fuchsias, and chrysanthemums, violet-coloured Louis Passy roses and silver-white Altairs with streaks of heliotrope.

Uncle You should be careful with flowers.

Nurse If you mean me…

Aunt Hush. Don’t answer back.

Uncle I mean all of you. I found dahlia seeds trampled into the soil. (He goes into the conservatory.) You don’t appreciate my conservatory enough; since the eighteenth century, when the Countess de Vandes grew the first musk rose, no one in Granada has managed it except me, not even the botanist at the University. You must have more respect for my plants.

Nurse Well, don’t I respect them?

Aunt Ha! You’re the worst.

Nurse Yes, Señora. But I say drench the flowers like that and sprinkle water everywhere and we’ll soon have toads in the sofa.

Aunt Well you like the scent of flowers.

Nurse No, Señora. To me flowers smell of dead children, or a flock of nuns, or a church altar. Sad things. Give me an orange or a fine quince, and you can forget all the roses in the world. But here….it’s roses to the right, basil to the left, anemones, salvias, petunias and those flowers of today, the fashionable ones, chrysanthemums, ruffled like the hair of gipsy girls. How I’d love to see a pear-tree planted in this garden, or a cherry, or a persimmon!

Aunt So you could eat them!

Nurse Since I’ve a mouth…As they sang in my village;

The mouth is there for eating,

the feet are there for dancing,

and a woman has something…

(She stops goes, over to the Aunt, and whispers to her.)

Aunt Jesus! (Crossing herself)

Nurse It’s village vulgarity. (Crossing herself)

Rosita (Entering rapidly. She is in red: her dress is nineteenth century, with mutton sleeves and trimmed with ribbons.) And my hat? Where’s my hat? San Luis’ bells have already chimed thirty!

Nurse I left it on the table.

Rosita Well it’s not there. (Looking for it)

(The Nurse exits.)

Aunt Have you tried the cupboard?

(The Aunt exits.)

Nurse (Entering) I can’t find it.

Rosita Can it be possible that no one knows where my hat is?

Nurse Wear the blue one with daisies.

Rosita You’re crazy.

Nurse Not as crazy as you.

Aunt (Returning with it) Here it is, be off with you!

(Rosita takes it and runs out.)

Nurse Everything has to be done on the wing. Today wants now what will happen tomorrow. It takes flight, and slips through our hands. When a little girl has to count the days she begins when she’s already old: ‘My Rosita is eighty now’…it’s always so. How often has she sat down to watch you do tatting or frivolité, or point de feston, or draw threads to adorn a dressing gown.

Aunt Never.

Nurse Always in and out, and out and in; in and out, and out and in.

Aunt Mind what you’re saying!

Nurse Whatever it means, it’s nothing new.

Aunt Of course I’ve never liked to oppose her. How can one hurt an orphaned creature?

Nurse Neither father nor mother, nor dog to defend her, but she has an uncle and aunt who are treasures. (She embraces her.)

Uncle (Within) Now this is the end!

Aunt Holy mother of God!

Uncle It’s fine that they crush my seeds underfoot, but it’s intolerable that they tear the leaves from a rosebush I love so much: more than all the other roses, the musk or the hispid or the pompon or the damascene or the eglantine or the Queen Isabel. (To the Aunt) Come, come and see.

Aunt It’s broken?

Uncle No, no the worst hasn’t happened, but it might have.

Aunt We’ll get to the bottom of this!

Uncle I wonder who knocked its pot over?

Nurse Don’t you stare at me.

Uncle Was it me, then?

Nurse Why not a cat, or a dog, or a gust of wind through the window?

Aunt Go, and sweep the conservatory.

Nurse In this house it’s clear no one’s allowed to speak.

Uncle (Entering) It’s a rose no one has seen before; a surprise I’ve prepared for you. Because it’s unbelievable this ‘rosa declinata’ with drooping buds, and defenceless because it lacks thorns; What a marvel, eh? Not one thorn! Because there’s the myrtifolia that comes from Belgium and the sulphurata that shines in the dark. But this surpasses them all in rarity. The botanists call it ‘rosa mutabile’, which means mutable, changeable…There’s a description and a picture in this book, look! (He opens the book.) Red in the morning, it whitens in the afternoon, and fades at nightfall.

When it opens in the morning,

It glows as red as blood.

The dew won’t touch it

Afraid of being burnt.

Open wide at noon

It’s hard as the coral.

The sun leans through windows

To gaze at its gleaming.

When the birds begin

To sing in the branches

And the afternoon faints

In violet light, off the sea,

It turns white, as white

As a grain of white salt.

And when night chimes

Its white horn of metal

And the stars all appear

As the breezes die,

In a ray of darkness

It starts to fade.

Aunt And has it flowered yet?

Uncle One flower has opened.

Aunt And it only lasts a day?

Uncle Just one. But I think I’ll spend the day beside it to watch how it whitens.

Rosita (Entering) My parasol.

Uncle Your parasol.

Aunt (Loudly) The Parasol!

Nurse (Appearing) Here’s the parasol!

(Rosita takes the parasol and kisses her uncle and aunt.)

Rosita How do I look?

Uncle Beautiful.

Aunt There’s not another like you.

Rosita (Opening the parasol) And now?

Nurse For the love of God, close that parasol, you mustn’t open one indoors. It brings bad luck!

By Saint Bartholomew’s wheel

And Saint Joseph’s staff

And the sacred laurel bough,

Darkness, get thee

To Jerusalem’s four corners.

(The others laugh. The uncle exits.)

Rosita (Closing it) It’s closed.

Nurse Don’t do that again! Holy….saints!

Rosita Oops!

Aunt What were you going to say?

Nurse But I didn’t say it.

Rosita (Leaving, with a smile.) See you later!

Aunt Who’s going with you?

Rosita (Bowing her head) I’ll be with the girls. (She exits.)

Nurse And the boyfriend.

Aunt The boyfriend I believe I had to accept.

Nurse I don’t know which I like better, whether it’s the boyfriend or her. (The Aunt sits down to her lace-making.) A pair of cousins to be put on a shelf of sugar, and if they die, God help them, be embalmed, and set in a niche with crystal and snow. Which do you prefer? (She begins sweeping up.)

Aunt I love them both, as nephew and niece.

Nurse One for the top sheet and one for the bottom, but…

Aunt Rosita grew up here with me…

Nurse Of course. As if I didn’t believe in family. With me it’s law. Blood runs in our veins, but unseen. She loves a second cousin she sees every day more than a brother far away. For what, we’ll see.

Aunt Woman, get on with the cleaning.

Nurse I see it now. Here you’re not allowed to open your mouth. You nurse a lovely girl like that. You abandon your own children, in a shack, quivering with hunger.

Aunt It’s ‘quivering with cold’.

Nurse Quivering with everything, so they can say to you: ‘Be silent!’ And since I’m a servant I can do no more than be silent, so that’s what I do, and I can’t answer and say…

Aunt And say what..?

Nurse Oh…leave that bobbin alone with its clicking: you’re making my head burst with your clicking.

Aunt (Laughing) Go, and see who’s there.

(There is a silence on stage, in which we hear the sound of the bobbin with which the Aunt is lace-making.)

Voice (A street-vendor’s call) Camomile….from the mountains!

Aunt (Speaking to herself) One must buy camomile sometimes. On some occasions it’s needed….Another day goes by…. (counting the points in her lace) thirty-seven, thirty-eight.

Voice (Further off) Camomile…from the mountains!

Aunt (Taking a pin) And…forty.

Nephew (Entering) Aunt.

Aunt (Without looking at him) Hello, have a seat if you want. Rosita has gone out already.

Nephew Who is she with?

Aunt With the girls. (A pause. She looks at the Nephew.) Something’s happened.

Nephew Yes.

Aunt (Anxiously) I can almost guess. I hope I’m wrong.

Nephew No. Read this.

Aunt (Reading) Well: it’s natural. That’s why I opposed your relationship with Rosita. I knew that sooner or later you would have to join your parents. And how close it is! Forty days travel to reach Argentina, to reach Tucumán. If I were a man and younger, I’d slap your face.

Nephew It’s no sin to love my cousin. Do you imagine that I want to leave? Precisely when I want to stay, this arrives.

Aunt Stay? Stay? You have to go. There are acres of land, and your father is old. I’m here to insist you make the voyage. But you’ll leave me a life of bitterness. I don’t want to think about your cousin. You’re about to fire an arrow with purple ribbons into her heart. Now she’ll find that cloth doesn’t only serve to make flowers, but to soak up tears too.

Nephew What do you advise me to do?

Aunt You must go. Remember your father is my brother. Here you are no more than a stroller among gardens, while there you will be a farmer.

Nephew But I would prefer…

Aunt To marry? Are you mad? When your future’s already laid out? And take Rosita with you, no doubt? Over our dead bodies, your uncle’s and mine.

Nephew That’s just words. I know only too well I can’t. But I want Rosita to wait for me. I’ll soon be back.

Aunt If you don’t hit it off with a girl from Tucumán first. The words stuck to the roof of my mouth before I consented to your friendship with her; because my little girl will be left alone behind these four walls, while you’ll be free to travel the seas, the rivers, the groves of grapefruit trees: my little one will be here, her every day like another, and you’ll be there with horse and a gun shooting pheasants.

Nephew You’ve no reason to speak to me in this way. I gave my word and I’ll keep it. My father is in America keeping his word, and you know…

Aunt (Gently) Hush.

Nephew I have hushed. But don’t take my respect as a sign of shame.

Aunt (With Andalusian irony) Pardon me! I forgot: you’re a man now.

Nurse (Entering weeping) If he was a man he wouldn’t be going.

Aunt (Forcefully) Silence!

(The Nurse weeps with great sobs.)

Nephew I’ll return again in an instant. You tell her.

Aunt Don’t mind her. The old have to suffer difficult times.

(The Nephew leaves.)

Nurse Ah, what a tragedy for my little girl! A tragedy! A tragedy! Such are the men of today! I’ll be gathering gold coins in the street based on his promise. Once again tears fill this house. Ay! Señora! (Attacking him) If only a sea-serpent would swallow him!

Aunt For God’s sake!

Nurse By the sesame plant

By the three holy questions

And the cinnamon flower,

May your nights be evil

And your sowing be evil.

By the well of Saint Nicholas

May your salt turn to poison.

(She picks up a jug of water, and makes a cross in the salt)

Aunt No curses. Go about your business.

(The Nurse leaves. They hear laughter. The Aunt exits.)

First girl/coquette (Entering, and closing her parasol) Ay!

Second girl (Ditto) Ay! It’s chilly!

Third girl (Ditto) Ay!

Rosita (Ditto) My three pretty girls

Whom do you sigh for?

First girl For no one.

Second girl For the breeze.

Third girl For a lover, to court me.

Rosita What then will bring

A cry to your lips?

First girl The wall.

Second girl A true portrait.

Third girl The lace of my bedspread.

Rosita I long to sigh too,

My friends! My beauties!

First girl Who’ll receive it?

Rosita Two eyes

That the shadows whiten,

With lashes like vines,

Where the dawn’s sleeping.

And, though dark they’re

Afternoons of poppies.

First girl A ribbon for that sigh!

Second girl Ay!

Third girl Happy girl!

First girl Happy!

Rosita If I’m not mistaken, then I’ve

Heard certain things about you.

First girl Rumours are wild plants.

Second girl The murmur of the waves.

Rosita I’m going to tell…

First girl Here goes!

Third girl Rumours are garlands.

Rosita Granada, Calle de Elvira,

That’s where the girls live,

Who go to the Alhambra,

Three or four alone.

One dressed in green,

One in mauve, the other

In a Scottish corselet –

With ribbons at their tails.

Those in front are, herons;

The one behind’s a pigeon;

Open to the poplars

Mysterious the muslins.

How dark the Alhambra!

Where will the girls go

While suffering the shadow

The fountain and the rose?

What lovers do they hope for?

What myrtles will hide them?

What hands steal the perfume

From their swelling breasts?

No one’s with them, no one;

Two herons and a pigeon.

Yet the world has lovers

Hidden in the bushes.

The Cathedral still scatters

Bronze taken by the breeze.

The Genil lulls its oxen:

Its butterflies, the Darro.

The night comes charged

With its hills of shadow;

One shows off her shoes

Beneath silk lace flounces;

The eldest’s eyes are open

The youngest’s narrowed.

Whose will these three be

High-breasted long-tails?

To whom are they waving?

Now, where are they going?

Granada, Calle de Elvira,

That’s where the girls live,

Who go to the Alhambra,

Three or four alone.

First girl May the waves of rumour

Spread through Granada.

Second girl Do we have lovers?

Rosita Not one.

Second girl Is that the truth?

Rosita Yes, indeed.

Third girl Laces of frost adorn

Our bridal nightgowns.

Rosita But…

First girl The night delights us.

Rosita But…

Second girl In streets full of shadow.

First girl We climb to the Alhambra,

Three or four alone.

Third girl Ay!

Second girl Hush!

Third girl Why?

Ay!

First girl Ay, let no one hear her!

Rosita Alhambra, jasmine of sadness

Where the moonlight rests.

Nurse Child, your Aunt is calling you. (Very sadly.)

Rosita Have you been crying?

Nurse (Controlling herself) No…it’s just something, something I…

Rosita I’m not afraid. What’s happened? (She goes in swiftly, gazing at the Nurse. When Rosita has gone, the Nurse breaks into silent weeping.)

First girl (In a loud voice) What’s going on?

Second girl You tell us.

Nurse Be quiet.

Third girl (In a whisper) Is it bad news?

(The Nurse goes to the door and looks towards the point of Rosita’s exit.)

Nurse She’s telling her now!

(Pause, while they all listen.)

First girl Rosita is crying, let’s go inside.

Nurse Come back, and you’ll hear. Go! You can leave through the gate. (They leave.)

(The stage is left empty. A piano faintly plays a study by Czerny. A Pause. The cousin enters and on arrival halts centre stage as Rosita enters. The two remain gazing at each other. The cousin advances. He takes her by the waist. She leans her head on his shoulder.)

Rosita Why are your treacherous eyes

Intertwined with mine?

Why do your hands weave

Flowers above my head.

To what grief of nightingales

Do you condemn my youth,

For since my life and aim’s

Your figure and your presence,

You’ll shatter with cruel absence

The strings of my lute!

Cousin Oh, my cousin, my treasure,

Nightingale on the mountain,

Cease your singing of

Imaginary cold;

There’s no ice in my going,

For, though I cross the sea,

The waters must lend me

Nard of spume and calm

To contain the fire in me,

For I’m about to burn.

Rosita One night, half-slumbering,

On my balcony of jasmine,

I saw two cherubs plunging

Towards an amorous rose;

Being white in colour

It flushed incarnadine;

But, like a tender flower,

Its petals, all reddened,

Fell from it wounded

By the kiss of love.

So I, the innocent cousin,

In my garden of myrtle,

Gave my longings to the air,

My whiteness to the fountain.

Sweet, thoughtless gazelle

I raised my eyes, I saw you

And in my heart I felt

Sharp needles inside me

That are like open wounds

Crimson as wallflowers.

Cousin I shall return, my cousin,

To take you to my side

In a boat filled with gold

And with sails of happiness;

Light and shadow, day and night,

Thinking only of love for you.

Rosita But the poison love distils

In the isolated spirit,

Will weave with earth and water

A shroud for me when I’m dead.

Cousin When my tardy stallion eats

The stems bowed with dew,

When the mist from the river

Veils the rampart of the wind,

When the violence of summer

Paints me nature’s crimson

And the frost leaves in me

Pinpricks of the morning star,

I’ll say, for I love you,

That I would die for you.

Rosita Anxiously, I see you coming

One afternoon to my Granada

And all the light brine-filled

With nostalgia for the sea;

A yellow conjoined,

A jasmine bleeding,

Since the tangle of stones

Will impede your journey,

And a swirl of nard

Maddening the rooftops.

You’ll return?

Cousin Yes, I’ll return!

Rosita What bright dove will declare

You’re here, what annunciation?

Cousin The bright dove of my faith will.

Rosita See how I’ll embroider

Sheets for us, for us two.

Cousin By the diamonds of God,

The carnation in His side,

I swear I’ll come to you.

Rosita Farewell, Cousin!

Cousin So, farewell!

(They embrace facing each other. A distant piano is heard. The Cousin leaves. Rosita is weeping. The Uncle appears, who crosses the stage towards the conservatory. Seeing her Uncle, Rosita takes up the book of roses which is in reach of her hand.)

Uncle What were you doing?

Rosita Nothing.

Uncle You were reading?

Rosita Yes.

(The Uncle exits. Rosita reads.)

When it opens in the morning,

It glows as red as blood.

The dew won’t touch it

Afraid of being burnt.

Open wide at noon

It’s hard as the coral.

The sun leans through windows

To gaze at its gleaming.

When the birds begin

To sing in the branches

And the afternoon faints

In violet light, off the sea,

It turns white, as white

As a grain of white salt.

And when night chimes

Its white horn of metal

And the stars all appear

As the breezes die,

In the ray of darkness

It starts to fade.

Curtain