Francisco de Quevedo

Selected Sonnets

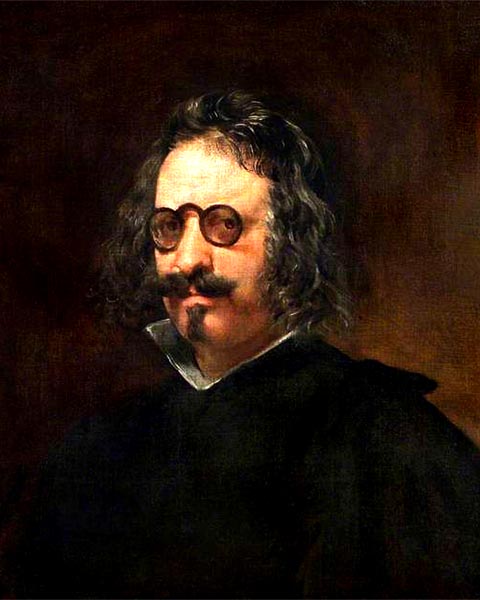

‘Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas’

Currently attributed to Juan van der Hamen, (17th century) Wikimedia Commons

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2023 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction.

- Cease your gleaming flow, O winding Tagus (Frena el corriente, ¡oh Tajo retorcido!)

- Since you flee from me, lovely Lisida (Ya que huyes de mí, Lísida hermosa)

- The golden touch of avaricious Midas (Rizas en ondas ricas del rey Midas)

- I view the mount that January ages (Miro este monte que envejece enero)

- You, the lovely princess of the dawn (Tú, princesa bellísima del día)

- Departing, languid, from his western tomb (Diviso el sole partoriva il giorno)

- In a tempest of crisp undulating gold (En crespa tempestad del oro undoso)

- If whoever paints you must first behold you (Si quien ha de pintaros ha de verso)

- It’s burning ice, it’s an icy fire (Es hielo abrasador, es fuego helado)

- You show so much courage and endeavour (¡Mucho del valeroso y esforzado)

- If you’re a god, Amor, where is your heaven? (Si dios eres, Amor, ¿cuál es tu cielo?)

- I grant the fleeting shadows my embrace (A fugitivas sombras doy abrazos)

- If my eyelids, Lisis, were parted lips (Si mis párpados, Lisi, labios fueran)

- You, that trouble the sea’s peace, Navigator (Tú, que la paz del mar, ¡oh navegante!)

- Unruly locks, curling and entangled (Crespas hebras, sin ley desenlazadas)

- High, among the mountains of Segura (Aquí, en las altas sierras de Segura)

- In a narrow compass I bear imprisoned (En breve cárcel traigo aprisionado)

- Twisting unevenly, soft yet sonorous (Torcido, desigual, blando y sonoro)

- The splendour which died, convincingly (La lumbre, que murió de convencida)

- How strong, how deep, the sorrow is within (¿Cómo es tan largo en mí dolor tan fuerte)

- Boreas now churns Pontus with his tumult (Molesta el Ponto Bóreas con tumultos)

- A musician weeping in sonorous lament (Músico llanto en lágrimas sonoras)

- It pains me not to die, I’ve not declined (No me aflige morir, no he rehusado)

- In the cloisters of my soul, the wound is quiet (En los claustros del alma la herida)

- Amor occupies my mind and senses (Amor me ocupa el seso y los sentidos)

- You waste your time, Death, in wounding me (Pierdes el tiempo, Muerte, en mi herida)

- The burning sun has robbed me of ten years (Diez años de mi vida se ha llevado)

- They may well grant life to the daylight (Bien pueden alargar la vida al día)

- If the noose was beautiful, the bait sweet (Si hermoso el lazo fue, si dulce el cebo)

- A tree-trunk, hard, inanimate, burns not (Arder sin voz de estrépito doliente)

- Ah, Floralba, I dreamed…shall I say it? (¡Ay Floralba! Soñé que te ... ¿Dirélo?)

- The beauty I perceive in Floralba (No es artífice, no, la simetría)

- If memory can recall diverse things (Si de cosas diversas la memoria)

- Sometimes a curved ship’s prow may be seen (Tal vez se ve la nave negra y corva)

- Most lovely, yet wintry, beauty of my life (Hermosísimo invierno de mi vida)

- To the gold of your hair, carnations bring (Al oro de tu frente unos claveles)

- The last shadow that the bright day brings me (Cerrar podrá mis ojos la postrera)

- The springtime of the year, the ambitious (La mocedad del año, la ambiciosa)

- It was ordained that I should love Flora (Mandóme, ¡ay Fabio! que la amase Flora)

- These are the very last tears, and will be (Éstas son y serán ya las postreras)

Translator’s Introduction

Francisco de Quevedo (1580 –1645) was a Spanish politician and writer, born in Madrid, to a family descended from Castilian nobility, his father and mother both attached to the royal courts. Quevedo was physically challenged, handicapped by a club foot, and severe myopia, and as he always wore spectacles, his name in the plural, quevedos, came to signify ‘pince-nez’ in Spanish. Studying at the universities of Alcalá and Valladolid from 1596 to 1606, he became expert in several languages.

In 1613 he was nominated as a counsellor to the Duke of Osuna, viceroy of Sicily and later of Naples, whom he served with distinction for several years. On the ascension of Philip IV of Spain, Osuna fell from favour and Quevedo was placed under house arrest. He thereafter refused political appointment, devoting himself to authorship. In 1639 he was again arrested, ostensibly for a satirical poem, and was confined to a monastery. Released in 1643, in ill-health, he died shortly after.

With his lifelong rival, Luis de Góngora, whom he fiercely satirised, Quevedo was one of the most prominent poets of Spain’s Golden Age in literature. His style is characterized by conceptismo, in contrast to Góngora’s culteranismo, the former based on the skilful association of concepts and ideas, subtlety being sought through compression and artifice; the latter primarily concerned with formal beauty, sensory richness, and ornamentation. The poems of the two collections represented here, Las tres musas últimas castellanas: The three last Castilian Muses and El Parnaso español: The Spanish Parnassus were published posthumously.

Cease your gleaming flow, O winding Tagus

(Frena el corriente, ¡oh Tajo retorcido!)

(‘He tells the river that it signifies his pain, since it swells with his tears’)

Cease your gleaming flow, O winding Tagus,

You that rich and golden reach the sea,

While I must seek (oh, could I but find it!)

Oblivion for a harshly-scorned affection.

Quell your gentle murmurs, for you see

That he who drank your waters once, is lost;

Behold my crystal tears of deep dismay,

That you now bear to the widening ocean.

Since my troubles drown me in sorrows,

Cease to sparkle with the new-born light,

Or nourish aught but thorns, on your shores.

For there’s no reason, when your chill waters

Are but the rain that pours now from my eyes,

For you to smile, when all within me cries.

Since you flee from me, lovely Lisida

(Ya que huyes de mí, Lísida hermosa)

(‘To Lisida, asking for the flowers in her hand, exhorting her to imitate a flowing stream’)

Since you flee from me, lovely Lisida,

Now imitate the manner of this stream,

That flees between its shores forever,

Ever generous in the favour it yields.

Flee from me, courteous and disdainful,

Like to the flow that pours from my eyes;

Though, in passing, so much ardent fire,

Is surely worth a leaf or two, and a rose.

Cause of my sorrow, since your lips smile

At the heart-breaking cries I now utter

As a sacrifice to their rubied cloister,

Forgive me, for the sake of what I love,

And as, you wander on, disdainfully,

Bear on the voice with which I call to you.

Note: The name Lisida, often shortened to Lisi, in Quevedo’s sonnets, appears to be derived from the name of Virgil’s pastoral shepherd, Lycidas, in the Eclogues.

The golden touch of avaricious Midas

(Rizas en ondas ricas del rey Midas)

(‘To Lisi, a coronet of crimson carnations in her hair’)

The golden touch of avaricious Midas,

Set waves of rich curls, Lisi, in your hair;

Carnations burn now, in its bright circuit,

Conspicuous as blood, wounded splendours,

Incendiaries, embedded midst a garden,

Seeming miracles of love, a rare portent,

Hybla tinting the marble, such that I halt

To view the flowers ablaze, in its smoothness.

Those rich blooms, whose blood-stained beauty,

In that generous head of hair, gives offence

To your resplendent, and glorious mane,

Grant to lips, that guard their pearly cloister,

Already sonorous carnation, knowing coral,

A ruby eloquence, and rich, purpled beauty.

Note: Mount Hybla in Sicily was noted for its honey-producing bees; Hybla was the Sicilian mother-goddess, after whom a number of towns were also named.

I view the mount that January ages

(Miro este monte que envejece enero)

(‘He says the sun melts the Alpine ice but Lisi’s eyes temper not the ice of her disdain’)

I view the mount that January ages,

And the snow that covers, in white hair,

Its summit, that the sun, dim and cold,

Is first to touch with its warming light.

I see that, grateful for his brief mercy,

Many a pleasing spring drinks the ice,

Gifting fragments onwards, in its journey,

Free and talkative, a sparkling musician.

Yet in the Alps that form your angry heart,

Your eyes, though orbs of fire, yet refuse

To grant, in welcome, a like flow of ice.

My own flames wax in the freezing cold,

As, chilled, I burn beneath my own ashes,

While envying those streams’ rare happiness.

You, the lovely princess of the dawn

(Tú, princesa bellísima del día)

(‘He asks Aurora, the Dawn, to stay, so he may view his lover’s image in the sky’)

You, the lovely princess of the dawn,

Conqueror of the nocturnal shadows,

Joyful painter, of the melancholy sky,

With deepest purple and smiling gold,

Since you’re the flagrant, rich precursor

Of the sun that sends you forth, and follows;

Since, to ennoble you, I call that lovely,

And that peerless, girl of mine, Aurora;

Since the night deprived me of her light,

And she, most piously, escaped my eyes;

Show me her image, in the morning star.

Deny the sun this hour; without envy,

Let one, whose fair light exceeds yours,

Hide, in you, her burning snow and rose.

Departing, languid, from his western tomb

(Diviso el sole partoriva il giorno)

(‘Sonnet in the Tuscan language’)

Departing, languid, from his western tomb,

The sun, gave birth to day, as ardent light

Rose, in the heavens, from his sepulchre

Crowned with his coronet of shining rays.

Adorned with an imperious majesty,

Was my lord, who, with fiery intent,

So idly plunders my afflicted life,

To help illuminate his sojourn here.

He gives life to the day, yet steals from me,

(Harsh with me, generous to the twilight)

She that I loved, to honour as a goddess;

The blonde hair loosens, that bound my heart

That learnt what cruelty is from his gaze,

And, now protesting, looks upon fair Venus.

In a tempest of crisp undulating gold

(En crespa tempestad del oro undoso)

(‘Various of his heart’s affections riding the waves of Lisis’ hair’)

In a tempest of crisp undulating gold

Borne amid gulfs of pure and burning light,

My ardent heart swims, thirsting for beauty,

Whenever you seek to free your rich hair.

Leander, amidst a sea of stormy fire,

Proclaimed his love, while shortening his life.

Icarus, on a perilous golden course,

Melted his waxen wings, in glorious death.

With pretension to phoenix-like powers,

My perished hopes ablaze, I shed tears.

Intent on dying to engender life,

Rich yet avaricious, poor in treasure,

In my longing, and torment, a Midas;

Tantalus, to that golden fount in flight.

If whoever paints you must first behold you

(Si quien ha de pintaros ha de verso)

(‘The difficulty of portraying a great beauty’)

If whoever paints you must first behold you

Yet cannot do so without being blinded,

Who then will have the power to depict you,

Without offending both your sight and you?

I sought your flowering in snow and roses,

But honouring the roses would slight you.

A pair of stars for eyes I wished to grant you,

But how could mere stars dream of doing so.

A sketch proclaimed the thing impossible,

But then the mirroring of your own light,

Captured your essence through reflection,

Owning the power to render you fittingly,

Your own self, born of you, in the mirror,

As artist, model, brush, and portrait too.

It’s burning ice, it’s an icy fire

(Es hielo abrasador, es fuego helado)

(‘A definition of love’)

It’s burning ice, it’s an icy fire,

It’s a wound, whose pain you fail to feel,

It’s a happy dream, a sad reality,

It’s a brief rest, that greatly wearies.

It’s a carefreeness, that brings us care,

A coward that pretends to bravery,

A solitary path amidst the crowd,

An affection to engender affection.

It’s a freedom that’s incarceration,

That endures till the last paroxysm,

An infirmity that worsens if it’s cured.

It’s Love, a child; and yet is your abyss:

(Behold, its true kinship with the void)

And, in sum, the opposite of its own self.

You show so much courage and endeavour

(¡Mucho del valeroso y esforzado)

(‘Pointless and cowardly, Love’s victory, when the lover is already conquered’)

You show so much courage and endeavour

Yet seek to show it through my surrender!

Enough, Love, that I’ve thanked you for my woes,

Of which I might have readily complained.

What blood remains that I have not offered?

What bolt from your quiver have I not felt?

Behold how the patience of the sufferer

Yet overcomes the weapon fired in anger!

I’d like to see you matched against your equal,

For I find my ardour raised, in such a manner

That the greater the ill the more my strength.

What use is there in kindling what is burning,

Unless you would deal death to Death itself,

And proclaim through me that the dead can die?

If you’re a god, Amor, where is your heaven?

(Si dios eres, Amor, ¿cuál es tu cielo?)

If you’re a god, Amor, where is your heaven?

If a lord, where are your rents, your estates?

Where is your household, and your servants?

Where, in this world, your customary place?

If you go disguised in a mortal veil,

Where are your lands, your apartments?

If you are rich, where is your treasury?

Why do I find you naked in sun and ice?

Love, do you know how all this seems to me?

In showing you blindfolded, and with wings,

That’s how the world, and its artists, see you.

And I too, since merely the honest face

Of my Lisis, has so filled you with fear

You seem no more than a blind chick, Amor.

I grant the fleeting shadows my embrace

(A fugitivas sombras doy abrazos)

(‘Seeking tranquility, in love in vain’)

I grant the fleeting shadows my embrace

Wearying my spirit lost in dreams.

Night and day I pass fighting, alone,

With an imp that I’m clasping in my arms.

When I want to grasp it more tightly,

Seeing me sweat, it sends me astray.

Stubbornly, I return with greater force,

And loving thoughts tear me to pieces.

I’ll take vengeance on those vain images,

That I’ve failed to banish from my eyes,

That mock me and, mocking coyly, vanish.

Though I lack the courage to chase after,

Yet my desire to capture them is such,

My tears pursue them, flowing streams.

If my eyelids, Lisis, were parted lips

(Si mis párpados, Lisi, labios fueran)

(‘Communication of invisible love through the eyes’)

If my eyelids, Lisis, were parted lips

Then their kisses would be visual rays

From my two eyes, that, as eagles, gaze

On the sun; kissing, rather than seeing.

Of your beauty they’d drink, dropsically;

Of crystal, thirsting for the crystalline

Depths of your eyes, those celestial fires

Nourishing them, dying, granting life.

Maintained thus by invisible commerce,

Free of the body, my powers and senses,

Might then proceed to enjoy their favours;

Mute, flirting together, in their ardour,

Apart, they would perceive their love, as one,

And as secret, though they did so publicly.

You, that trouble the sea’s peace, Navigator

(Tú, que la paz del mar, ¡oh navegante!)

(‘He seeks to gorge himself, covetously, on Lisis’ treasure’)

You, that trouble the sea’s peace, Navigator,

Covetous, and diligent in your travels,

Eager to bleed the veins of the Orient

Of its richest and most brilliant metals,

Halt here, refrain from sailing onwards,

Gorge yourself, momently, on treasure,

Where lovely Lisis combs, from her brow,

Those subtle strands, in fulminating waves.

If you seek pearls, her happy laughter

Reveals more than Columbus ever found,

If vermilion, her lips are Tyrian purple.

If flowers are sought, her lovely cheeks

Outdo the spring, or the sky at dawn,

If the heavenly lights, her eyes are stars.

Unruly locks, curling and entangled

(Crespas hebras, sin ley desenlazadas)

(‘An uncommon portrait of Lisis’)

Unruly locks, curling and entangled,

That Midas once held in his two hands;

A pair of burning embers in the snow,

Remaining, of her courtesy, at peace.

Early roses, born in April and May,

Defended from the injuries of time;

Auroras of the dawn in her laughter,

Stolen, greedily, from the carnations.

Living planets in an animated sky,

For which Lisis aspires to be queen

Of the liberties bound by their light.

A rational orb that lights the Earth,

Where Love reigns in her least glance,

And where Love lives as she slays.

High, among the mountains of Segura

(Aquí, en las altas sierras de Segura)

(‘He sheds tears in the infant Guadalquivir, so that it can bear them to Lisis when full grown’)

High, among the mountains of Segura,

Blending their pure sapphire with the sky’s,

You are born, in a cradle of liquid ice,

Amidst the fitting grandeur of such heights.

Born of a pure source, Guadalquivir,

Whence a stream of your crystalline flow,

Having thrown itself from the solid stone,

Twists, and turns across the ground below.

Here, I grant you a tribute of my tears,

A first offering to the fair Lisis’ beauty,

Tears that will serve now to swell your flow.

Yet I fear that, reaching her, a swelling river,

Your powerful current cannot but forget

This gift your infant stream is grateful for.

In a narrow compass I bear imprisoned

(En breve cárcel traigo aprisionado)

(‘A portrait of Lisis, adorning a ring’)

In a narrow compass, I bear imprisoned,

With all its lineage of burning gold,

A blazing circle of resplendent light,

Enclosing a mighty empire of love.

I bring the starry field in which creatures

With gleaming coats, peacefully, graze;

And, concealed from the Eastern skies,

The dawn of light, and a brighter beginning.

I bring all the Indies, borne on my hand;

Pearls, that, in diamonds, through rubies,

Utter their sonorous ice, with disdain.

Speaking perhaps of tyrannical flames,

Lightning-bolts of crimson laughter,

Auroras, splendours, presumptions of heaven.

Twisting unevenly, soft yet sonorous

(Torcido, desigual, blando y sonoro)

(‘His lover’s speech compared to the voice of a flowing stream’)

Twisting unevenly, soft yet sonorous,

Slipping, secretly, among the flowers,

Your current stealing by in the heat,

Whitened by foam, and as blonde as gold.

In drops of crystal dispensing treasure,

A liquid plectrum for rustic lovers,

For nightingales, a tempering of strings,

You swell into laughter at my lament.

Playful as glass seems, in your blandishments,

Joyful you flow from the mountain ledge,

Then turn to grey, in dishevelled foam.

No differently does my troubled heart

Arrive in captivity, to shed fresh tears,

Cheerful, and confident, and unaware.

The splendour which died, convincingly

(La lumbre, que murió de convencida)

(‘To a lady blowing out a candle, and relighting it in a breath)

The splendour which died, convincingly,

With the light of your eyes, and vanished,

Lest, in the smoke, it showed signs of mourning,

Obsequies for your now-darkened flame,

Might represent the transience of life

All-conquering beauty so encouraged,

Which, in the firmament’s disastrous fall,

Thus, signifies the wound with every ray.

You, who doused it, now regretting

Your harshness, with a mischievous gesture

Restore to it an even greater beauty.

A breath of yours, impressed on the smoke,

That from your mouth creates a miracle,

An aureole that seems fashioned like a kiss.

Note: As regards the linguistic complexity built on a slight idea, in this and other sonnets, compare the poetry of Mallarmé, for example: ‘Toute l’âme résumée: all summarised, the soul’.

How strong, how deep, the sorrow is within

(¿Cómo es tan largo en mí dolor tan fuerte)

(‘The danger of speaking or saying nothing, and of the voice of silence’)

How strong, how deep, the sorrow is within,

Fair Lisis; if I speak the ills I feel,

What excuse have I for my audacity?

If silent, what can then excuse my death?

How without speaking to you, face to face,

Can I reveal my haggard countenance?

Feelings find a voice, even in silence,

Tears that are shed are full of eloquence.

Whoever lights a flame comprehends it;

The angered comprehend their accuser;

He that remains silent, they understand.

And sighs, too, the mute remains of sorrow

The mouth utters forth, they comprehend,

As they do tears, and the unspeaking eyes.

Boreas now churns Pontus with his tumult

(Molesta el Ponto Bóreas con tumultos)

(‘The lover shipwrecked amidst disdain’)

Boreas now churns Pontus with his tumult,

To cerulean crests, and foaming breakers,

The peaceful surface of the sea disfigured,

Torn, in formidable watery gouts, asunder.

The nearby shore yet threatens the reprieved,

Blandly, with a cruel incarceration;

The light of the sun, obscured, flickers,

Warily, in fear of some fresh insult.

The voyager is abandoned to the storm;

The sails yield to the spirit out of Thrace,

The masts groan, no less the passengers.

I too, shipwrecked, a lover and a pilgrim,

Am dying, in a storm of love for Lisis,

Pursuing the mad fury of a noble fate.

Note: Boreas is (the god of) the northern wind from Thrace (a region now split between Greece, Bulgaria and Turkey); Pontus is the Black Sea.

A musician weeping in sonorous lament

(Músico llanto en lágrimas sonoras)

(‘The lover taught about love by inanimate teachers’)

A musician weeping in sonorous lament,

Drawing stony echoes from cold caverns,

While distilling a liquid harmony,

Turns the rocks into sounding zithers.

At all hours, pleasantly concealed

In the deep shade, hosting little light,

It admits no company to its secrets,

Only you, uttering your sad cries.

Your name, colour, and sorrowful voice,

Denote not some strange bird, but a lover:

A listener might learn from your pain.

Compare your laments and countenance,

With these sighs, and this stony brow;

And become a student of my sorrows.

It pains me not to die, I’ve not declined

(No me aflige morir, no he rehusado)

(‘The lover’s amorous lament, and ultimate feelings’)

It pains me not to die, I’ve not declined

An end to life, nor have I attempted

To delay this dying, that was born

In the same hour as life, and sorrow.

I regret my leaving tenantless

A body that has housed a loving spirit,

A heart deserted, ever blazing,

That has hosted all the realm of love.

My ardour points to the eternal flames,

And it seems my tender cry alone

Will mark my long, distressing story,

Yet, Lisis, memory tells me, that since

I must suffer hell through your glory,

Glory demands – tormented suffering.

In the cloisters of my soul, the wound is quiet

(En los claustros del alma la herida)

(‘He perseveres in an excess of loving affection and suffering’)

In the cloisters of my soul, the wound is quiet;

And yet life still feeds hungrily inside

Every vein, now; the life that is summoned

From my bones, the very depths of my marrow.

My life drinks the dropsical ardour;

A life already thinned to loving ashes,

The dead remainder of the lovely fire

That smoulders in smoke and deathly night.

I shun others; in horror of the daylight,

I voice all this dark weeping aloud,

My fierce grief sends to an unhearing sea.

I grant a singing voice to my sighs,

While confusion inundates my soul,

My heart a wasted kingdom of fear.

Amor occupies my mind and senses

(Amor me ocupa el seso y los sentidos)

(‘The same state of his affections continues’)

Amor occupies my mind and senses,

I’m absorbed in amorous ecstasy.

This civil war within the very self,

Grants me neither truce nor repose.

The flowing river of my sighs expands

Through the vast region of the heart,

Content to suffer, in its great sorrow,

And drown memory, now, in oblivion.

All ruin am I, and all destruction;

The deathly scandal of those lovers

That seek to construct their joy from pity.

Those to come, like to those that went before,

If they are constant, may envy my tears,

And recognise their state in my sobbing.

You waste your time, Death, in wounding me

(Pierdes el tiempo, Muerte, en mi herida)

(‘Skilful evasion of death, if it succeeds; and, meanwhile, most ingenious’)

You waste your time, Death, in wounding me,

For he that lacks all life can scarcely die;

If you would end my life, you must return

To those two eyes in which my life resides.

Though you’re merciless, you’ll not dare to go

To that holy place, where it dwells, withdrawn.

Were I to see you there, then you’d prove alive,

And, in being so, would fail to know yourself.

I am the ash; the glowing fire’s remains.

No fuel is left for the flames to consume,

That once were spilled in amorous burning.

Return to some other wretched soul, whose plea

Summons you now, that you might ease his pain;

For the life I no longer own, I cannot yield.

The burning sun has robbed me of ten years

(Diez años de mi vida se ha llevado)

(‘Love, born at first sight, lives, increases, and self-perpetuates’)

The burning sun has robbed me of ten years,

Snatched away in swift, unheeding flight,

Since I viewed the Orient in your two eyes,

My Lisis, double its beauty mirrored there.

Absent for those ten years, I yet have fed

With my blood the sweet fire that still lingers

In my veins. Ten years, those twin lights of yours,

Have reigned, imperiously, in my mind.

Enough – to view the noblest beauty once,

That, stamped on the soul, endures eternally,

Igniting this eternal blaze, once seen;

A flame that transcends this poor mortal life,

Unafraid of interment with the body;

A flame time neither lessens nor offends.

They may well grant life to the daylight

(Bien pueden alargar la vida al día)

(‘To Lisis’ eyes, returning after a long absence’)

They may well grant life to the daylight,

Replace the dawn, and supplant the sun,

And conceal the night at any hour,

Those lovely eyes of yours, my Lisis.

They are the sovereigns of light and fire,

With whom great empires hide their treasure,

Twin deities that, with avenging flame,

Punish, or deign not to punish, boldness.

I shall return to view you, if one can

Retrieve a soul from where it lies,

And if this absentee be yet alive.

I grant you, at the very least, that this,

If it is aught, that yet remains of me,

They’ll see reduced to an ardent shade.

If the noose was beautiful, the bait sweet

(Si hermoso el lazo fue, si dulce el cebo)

(‘A metaphorical expression of his loving feelings, till allegorically consumed’)

If the noose was beautiful, the bait sweet,

The net’s tyrannical, the prison harsh;

Your captive lover, I owe this, Lisis

To my ill-fortune, and your beauty.

Phoebus and Jove envy me the noose,

Winged Amor the sweetness of the bait,

My ill-fortune worsens net and prison,

Since I, in adoring them, renew them.

I adore them, and know no suffering,

And bound in prison, tied in your net,

Abhor the life I lived without them.

Scorched, yet filled with joy, equally,

I adore the flame, and the swelling fire,

So high a cost my true affection brings.

A tree-trunk, hard, inanimate, burns not

(Arder sin voz de estrépito doliente)

(‘Complaining of love’s sorrows must be permitted, and profanes not the secret’)

A tree-trunk, hard, inanimate, burns not

Without its voicing a mournful roar;

The oak laments the fire, and the pine

Sighs, within the flames it fails to feel.

Can you demand, then, Flora, that my heart,

A victim brought, obedient, to your altar,

Sensitive, and feeling, should be burnt

To silent ashes in your ardent flame?

Let your fire concede to me the whole

Of what the greedy flames grant oak and pine;

What’s divine shows mercy in its burning.

From the Etna yet erupting in my veins,

My fulminating woe pours out its ardour,

Though glory’s oblivious to its voice.

Ah, Floralba, I dreamed…shall I say it? (¡Ay Floralba! Soñé que te ... ¿Dirélo?)

(‘A lover grateful for the flattering lies of a dream’)

Ah, Floralba, I dreamed…shall I say it?

Yes, for a dream it was…that I enjoyed you.

And who, but for a lover that was dreaming,

Could so unite both heaven thus and hell?

My fire with your snow, and with your ice;

As Amor will choose contrasting arrows,

Combining them, in transparent manner,

As he does my adoration, her vigilance.

I said: ‘Seek Amor, seek my good fortune:

Never to sleep again, if I’m awake,

Never to wake again, if I am dreaming.

And yet, aroused from that sweet discord,

I found that, being dead, I was alive,

I found that, though yet living, I was dead.

The beauty I perceive in Floralba

(No es artífice, no, la simetría)

(‘He longs for that beauty which consists of movement’)

The beauty I perceive in Floralba

Is not that of artifice, symmetry,

Or of some statue, wrought by number,

That disdains to meet the light of day.

It’s not the work of harmonious music

(Despite the wonders Orpheus achieved)

That sees my hidden longing recognise

The majesty, in her, that heaven sends.

One can suffer from, yet not come to know,

One can long for, and yet not discover,

The soul, that is perceived in movement.

It is not found in some deathly stillness,

That beauty which is a moving flame,

A living thing, that cannot be quieted.

If memory can recall diverse things

(Si de cosas diversas la memoria)

(‘He seeks to prove, philosophically, that one person can love two at the same time’)

If memory can recall diverse things,

And past and present, joined together,

Can ease it, and grant it consolation,

Both pain and glory confined within,

And if, to the understanding, an equal

Power makes the created intelligible;

While to our free will it is granted

To make numerous, transitory, choices.

Why cannot Love, which is not merely

Powerful but omnipotent over all

That lives and feels, on this Earth of ours,

Create an ardent flame in one person,

(With two burning arrows from his bow),

Born of two diverse enkindling stars?

Sometimes a curved ship’s prow may be seen

(Tal vez se ve la nave negra y corva)

(Verifying the above, as regards his two lovers)

Sometimes a curved ship’s prow may be seen

Struggling, darkly, between conflicting winds,

Northerly, and easterly, and the more

The one hinders the other drives the waves.

This one, rams her, fiercely, with its forehead,

That, restrains her; while, suspended there,

And threatened by the ill-managed topsail,

Her keel fears the strait’s voracious thirst.

Likewise, my ardent heart burns and sighs

Driven astray, amorously shipwrecked,

Between Rosalba and the lovely Flora.

Torn by these two affections, I suffer,

While one victorious beauty awaits

A double triumph from a single conquest.

Most lovely, yet wintry, beauty of my life

(Hermosísimo invierno de mi vida)

(‘Amazement that Flora, being all fire and light, is wholly ice’)

Most lovely, yet wintry, beauty of my life,

Lacking summer’s heat, an unending frost,

To whose snow, heaven courteously grants

The violet tones of tender flowers ablaze;

How could that sphere of enriched light

That takes the god of Delos for its star,

Defend itself in a war of earthly elements,

Against the mighty queen of its enemies?

To the adoring soul, you are a Scythia,

That being gazed upon, inflames the sight;

An Etna treasuring its burning snows.

Except in its renowned fragility,

You appear like to glass, my Flora,

That though ice, is yet the child of flame.

To the gold of your hair, carnations bring

(Al oro de tu frente unos claveles)

(‘To Flora, her blonde hair adorned with carnations’)

To the gold of your hair, carnations bring

Their hues of bloodied, flowing wounds;

They die of love; of our life’s fragility,

Their warning gives notice to the faithful.

Fair examples, that show cruelty and pity,

Bright jewels, giving notice of dark crimes,

Well-published notices of flowery deaths,

Crimsoned canopies now fraying in the sun.

Yet they remain, blushing like your lips,

(Their petals competing not with rubies)

While paling afterwards, as if from fear.

And, with the lightning of your laughter,

As cowards, with ambition, we see them,

Their scarlet blazons withering in the flame,

The last shadow that the bright day brings me

(Cerrar podrá mis ojos la postrera)

(‘Love constant beyond death’)

The last shadow that the bright day brings me

May possess the power to close my eyes

And, that hour, release this soul of mine

To its eagerly, anxiously awaited favours,

Yet, on the other side, upon that shore,

It will not leave its memories behind;

Their ardent flame will conquer icy water,

Paying scant respect to the harshest law.

Soul that has been godlike in its prison –

Of veins that gave moisture to the fire,

Of marrow that once gloriously burned:

The body, you’ll abandon, not its cares;

They will be ash, but ash that yet feels;

Dust they will be, but an amorous dust.

The springtime of the year, the ambitious

(La mocedad del año, la ambiciosa)

(‘Examples of beauty’s transience pointed out to Flora, so they might not be wasted’)

The springtime of the year, the ambitious

Blush of the garden, the incarnate

Perfumed ruby-red, the mass, in short,

Of the beautiful boldness of the hour:

The ostentatious display of the rose,

Goddess of the field, star in the hedge,

The almond tree in its snowy bloom,

That dares to anticipate warmth to come:

Are mute rebukes, reprimands, O Flora,

To mortal beauty, and to human pride,

Both subject to the law that rules the flowers.

Your time will pass, though you doubt it,

Your yesterday you’ll regret tomorrow,

And, too late, and sadly, learn discretion.

It was ordained that I should love Flora

(Mandóme, ¡ay Fabio! que la amase Flora)

(‘Love, that without stopping at affectionate feelings, passes onwards to the intellect’)

It was ordained that I should love Flora,

Yet refrain from longing for her, Fabio;

And that, being fragmented and tainted,

I admire her, thus, while free of desire.

What human affection feels and longs for,

The understanding of the eternal spirit

Enjoys in a rarer manner, imprisoned

In this mortal cloister, its dull treasury.

To love is to know an ardent virtue;

While desire is but the directed will,

Gross, and deathly, in its discourtesy.

The body is earth; was, and will be, nothing.

Divinely, the mind’s inspired, eternally;

I, an eternal lover, born of eternity.

These are the very last tears, and will be

(Éstas son y serán ya las postreras)

(‘Surrender of an exiled lover to the power of his own sorrow’)

These are the very last tears, and will be,

That, with the power of my living voice,

I’ll see lost to the swift-flowing fountain,

That bears them to slake some brutish thirst.

Happy am I, if on a foreign shore,

Nurturing a pain so hard to elude,

I find a merciful death to topple

So vain, so chimerical, an edifice.

A naked spirit, a lover pure in love,

I will burn in the sun; let my cold flesh

Lost to earthly dust, yet appease Amor.

To the passer-by, I’ll yield an epitaph,

For, to him, my lifeless face will declare:

‘Love’s glory, it was, to make war on me.’

The end of the Selected Sonnets of Francisco de Quevedo