Osip Mandelshtam

On Dante

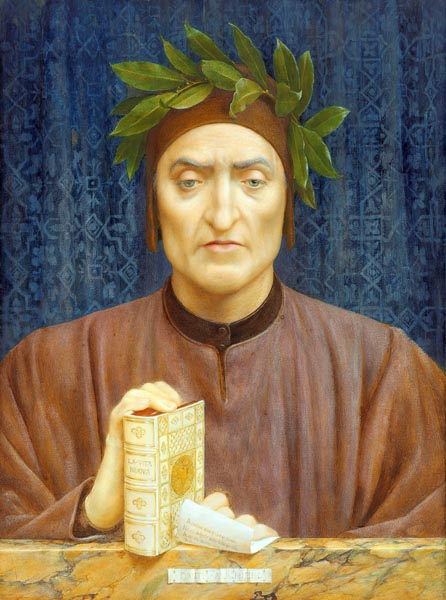

‘Dante Alighieri’

Henry James Holiday (English, 1839-1927)

Artvee

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2022 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

I

‘Cosi gridai colla faccia levata...’ (‘So, I cried, with lifted face…’)

(Inferno, XVI, 76)

Poetic speech is a dual process, producing sound in a dual manner – the first of its modes is an audible transformation of the very tools of poetic speech itself, arising in flight, through its very expression; the second is that of speech proper, that is the intonational and phonetic effort performed by the aforesaid instruments.

Understood in this way, poetry – even the most select – is not a part of Nature, and even less a reflection of it, which would make a mockery of the law of identity, but, with amazing independence, it resides in a new extra-spatial field of action, not so much speaking Nature but enacting Nature, aided by those tools colloquially referred to as images.

Poetic speech can only be referred to as producing ‘sound’ conditionally, because we hear it in the merging of these two modes, of which the one, considered by itself, is wholly mute, while the other, if regarded as free of instrumental metamorphosis, is devoid of any significance and interest, and lends itself to ‘retelling’, which in my opinion is the surest sign of the absence of poetry: for where a thing is commensurable with its retelling, there the sheets are unwrinkled, so to speak, there poetry did not pass the night.

Dante is rather a maker of tools, than a maker of images. He is a strategist of transformation and dual-process, and least of all a poet in the ‘common European’, and culturally external, sense of the title.

His wrestlers coiled in a ball in the arena can be viewed as in harmony with instrumental transformation, ‘wheeling about, as champion wrestlers, naked and oiled, do, looking for a hold or an advantage, before they grasp and strike one another…’ (Inferno XVI, 22-24)

In contrast, modern cinema, with the powers of metamorphosis of a tapeworm, achieves a vicious parody of the instrumentality of poetic speech, since, within it, frames move without a struggle, one simply replaced by another.

Conceive of something understood, seized on, torn from the darkness, in a language that is voluntarily and willingly forgotten, immediately after the clarifying act of understanding has been fulfilled.

In poetry only the fulfilled understanding is important – never passive, not concerned with replicating or retelling. The semantic satisfaction is equivalent to the feeling of a command having been executed.

The semantic wave-forms vanish, having done their work: the stronger they are, the more compliant, the less they are inclined to linger.

Otherwise, repetition, the hammering-in of ready-made nails termed ‘culturally-poetic’ images, is inevitable.

External and explanatory figurativeness is incompatible with tool-making.

The qualitative nature of poetry is determined by the speed and decisiveness with which it introduces its directed performance into the tool-free, lexical, purely quantitative process of word-formation. On a river, crammed with Chinese junks moving in every direction, it is necessary to cross the river leaping from boat to boat – that is how meaningful poetic speech is created. The route cannot be acquired by questioning the boatmen: they cannot say how or why they take any particular leap.

Poetic speech is a carpet-fabric based on many threads, differing from each other only in the colours created by means of the series of constantly-changing commands given to the loom.

It is an enduring carpet woven from liquid, a carpet in which the Ganges’ streams, considered as a thematic thread, are separate from those of the Nile or Euphrates, but create multi-coloured layers, figures, ornamentation, only not in pre-determined patterns, for that is the same as retelling. The ornamentation is excellent, because it retains traces of its origin, like a piece of nature in play. Animal, vegetable, mineral, Egyptian or Scythian, emblematic of a nation or barbarous, it is always speaking, visible, active.

The ornamentation is strophic.

The pattern is woven.

Gorgeous the poetic hunger of the ancient Italians, their brutal youthful appetite for harmony, their sensual desire (il disio) for rhyme!

The mouth works, a smile energises the verse, the lips purse happily and skilfully, the tongue is pressed trustingly against the palate.

The internal form of the verse is inseparable from the countless changes of expression that flicker on the face of the speaker, or anxious narrator.

It is the art of speech that distorts the face, explodes its calm, shatters its mask…

Once I had begun to study the Italian language and became familiar with its phonetics and prosody, I suddenly realised that the centre of gravity of my speech had shifted: nearer to the lips, the outer lips. The tip of the tongue was suddenly held in high esteem. Sound rushed to the barrier of the teeth. Another thing that struck me was the infantile nature of Italian phonetics, its beautiful childishness, close to the babble of infants, a kind of eternal Dadaism.

‘E consolando usava l’idioma

Che prima i padri e le madri trastulla;

................................................

Favoleggiava con la sua famiglia

De’ Troiani, di Fiesole, e di Roma’

‘And speaking in that soothing way,

that is the first delight of fathers and mothers

...............................................

Would tell her family

Of Troy, of Rome, of Fiesole.’

(Paradiso XV, 122-123, 125-126)

Would you like to become acquainted with an Italian rhyming dictionary? Seize any Italian dictionary and flip through it as you wish…there everything rhymes with everything else. Every word begs to be part of the concord.

There’s a marvellous abundance of marriageable endings. The Italian verb intensifies towards its ending, and is alive only through its ending. Each word hastens to explode, fly from the lips, depart and make room for others.

When it is necessary to depict a circle of time, to which a millennium is less than the blink of an eyelash,

Dante introduces childish absurdity into his astronomical, concordant, intensely public, oratorical dictionary.

Dante’s creation is primarily an exit into the public arena of contemporary Italian speech – as a whole, as a system.

The most Dadaistic of the Romance languages is promoted, internationally, to first place.

II

It is necessary to say something of Dante’s rhythm. People have little idea, yet need to be aware, of it. Whoever states that Dante is sculptural is in the grip of a meagre definition of ‘the great European’. Reading Dante is, first of all, an endless labour, which, insofar as we succeed, moves us further from our goal. If a first reading simply causes you shortness of breath and a healthy fatigue, then, for the subsequent one, equip yourself with a pair of indestructible Swiss boots, complete with nails. The question that seriously comes to mind is how many boot-soles, how many pieces of cowhide, how many sandals, Alighieri wore out during his poetic work, travelling the goat-paths of Italy.

The Inferno, and especially the Purgatorio celebrate the human when walking, the size and rhythm of the steps involved, the foot, and its shape. Each step, associated with the breath, and saturated with thought, Dante comprehends as the beginning of prosody. To denote walking, he employs a wealth of varied and charming phrases.

With Dante, philosophy and poetry are always on the move, always on their feet. Even stopping is a kind of accumulated movement: the platform for conversation is created by Alpine effort. A ‘foot’ of such verse – inhalation and exhalation – is a step. The step is inferential, aware, syllogizing.

Education is a school of the quickest of associations. You grasp on-the-fly, you are sensitive to hints – this gains Dante’s most ready praise.

In Dante’s sense, the teacher is younger than the student because he ‘runs faster.’

‘... Then he turned back, and seemed like one who runs for the green cloth, at Verona, through the open fields: and seemed one of those who wins, not one who loses.’ (Inferno XV, 41-44)

The rejuvenating power of metaphor recalls for us the educated and aged Brunetto Latini, in the form of a young man – a winner in the race in Verona.

What is Dante’s erudition?

Aristotle, like a butterfly made of towelling, is hemmed with the Arabian border of Averroes.

‘Averrois, che il gran comento feo...’

‘Averroes who wrote the vast commentary…’

(Inferno. IV, 144)

In this case, the Arab, Averroes, accompanies the Greek, Aristotle. They are part of the same picture. They fit together on the membrane of a single wing.

The end of the fourth canto of the Inferno provides a veritable feast of quotations. I find here, clean and unalloyed, a full display of Dante’s piano-keyboard of references.

His keyboard progresses around the horizon of antiquity. A kind of Chopin polonaise, where a fully-armed Caesar with the bloodshot eyes of a vulture, and a Democritus who disintegrated matter into atoms, perform nearby.

An extract is not a quotation. A quotation here is a cicada. Its characteristic is its relentlessness. It clings to the air and refuses to let go. Erudition is far from being the same as this keyboard of references, which is the very essence of education.

I would say that the whole composition is formed, not as a result of the accumulation of particulars, but by the fact that one detail, after another, breaks free of it, moves from it, flies off, splits from the system, entering into its functional space, its dimension, but each time in a strictly controlled manner and in the context of an adequately matured and unique situation for its existence.

We are at first ignorant of the details themselves, but are very sensitive to their position. And when reading Dante’s cantos, we receive information, as it were, reports from the field of military operations, and from them we perfectly guess how the war’s symphony of sound is being fought, although each bulletin of itself only slightly, in some specific place, strategically moves a flag, or reveals some changes in the timbre of the cannonade.

Thus, the whole thing arises as a result of the single differentiating impulse with which it is permeated. Not for a single moment does it retain a fixed self. If a physicist who decomposed an atomic nucleus wanted to assemble it again, he would be like the supporters of descriptive, explanatory poetry, for whom Dante is eternal plague and lightning.

If we had learned how to listen to Dante, we would have overheard the development of the clarinet and trombone, we would have heard the transformation of the viol into the violin, and the lengthening of the valve of the horn. And we would be audience to how the shifting core of a future homophonic three-part ensemble formed around the lute and the theorbo.

Again, if we had heard Dante, we would have inadvertently been plunged into a powerful stream, sometimes termed composition – an integral whole, metaphorically and in detail, and then comparatively elusive – generating definitions such that they return to it, enrich it with their own dissolution, and, having barely experienced the initial joy of becoming, instantly robbed of their birthright, re-joining the matter tossed between meanings, are washed away.

At the start of the tenth canto of the Inferno, Dante thrusts us into the blind inwardness of the compositional nexus:

‘Now my Master goes, and I, behind him, by a secret path between the city walls and the torments.’ (Inferno X, 1-2)

All efforts are aimed at combating the heaviness and darkness of the place. Forms of light erupt like teeth. Conversation is as necessary here as a torch in a cave.

Dante never enters into a single combat with matter without having prepared a means to capture it, without being armed with a meter to mark some specific period of pouring or melting. In poetry, in which all is measure, and everything proceeds from that measure and revolves around it, for its own sake, meters are instruments of a special nature, performing a uniquely active function. Here, the quivering compass needle not only proclaims the magnetic storm, but also creates its very being.

And so, we see that the dialogue of the tenth canto of the Inferno is magnetized by transient verb forms – the imperfect and past perfect, the past subjunctive, the present itself, and the future tense are employed in the tenth canto categorically; categorically and authoritatively.

The whole canto is built on several verbal attacks that boldly jump out of the text. Here, a table of conjugations unfolds, like a table of fencing moves, as it were, and we literally hear the tenses of the verbs.

First move:

‘La gente che per li sepolcri giace

Potrebbesi veder?’ –

‘Can those people, who lie in the sepulchres, be seen?’

(Inferno X, 7-8)

Second move:

‘Volgiti, che fai?’

‘Turn round: what are you doing?’

(Inferno X, 31)

It contains the horror of the present tense, a kind of ‘terror praesentis’. Here the unalloyed present is deemed nonsense. Completely severed from the future and the past, the present is conjugated as pure fear, as danger.

Three aspects of the past tense, relinquishing responsibility for what has already happened, are given in the terza rima:

‘I had already fixed my gaze on him, and he rose erect in stance and aspect, as if he held the Inferno in great disdain.’ (Inferno X: 34-36)

Then, like the notes of a powerful tuba, the past breaks through, with Farinata’s question:

‘...Chi fur li maggior tui?’ —

‘…Who were your ancestors?’

(Inferno X, 42)

How the auxiliary verb is stretched out here – a small chopped off ‘fur’ instead of ‘furon’! Isn't that how the horn was formed by an extension of the valve?

Next comes a slip of the tongue, a past perfect. This fells old Cavalcanti: of his son, the still living poet Guido Cavalcanti, he hears something from his peer and comrade – from Alighieri – as if from the fatal perfect past: ‘ebbe’ (Inferno X, 63)

And how wonderful that it is precisely this slip of the tongue that opens the way for the main flow of dialogue: Cavalcanti’s voice is washed away like the sound of an oboe or clarinet that has ceased to play, and Farinata, like a ponderous chess player, continues the interrupted move, resumes the attack:

‘And if my party have learnt

that art of return badly,

it tortures me more than this bed.’

(Inferno X, 77-78)

This dialogue in the tenth canto of the Inferno is an unanticipated clarification of the situation. It flows of itself from the watershed.

All the useful information, of an encyclopaedic nature, has already been communicated in the opening verses of the canto. The amplitude of the conversation slowly and steadily expands; crowd scenes, and images of people en masse, being indirectly introduced.

When Farinata rises up, scorning Hell, like some great nobleman who has ended by being imprisoned, the pendulum of the conversation is already traversing the full diameter of this gloomy plain intersected by fiery streams.

The concept of scandal is much older, in literature, than Dostoevsky, and in the thirteenth century, in Dante’s art, was far stronger. Dante experiences this unwanted and dangerous encounter with Farinata in exactly the same manner as Dostoevsky’s offenders experience their encounters with their tormentors – in the most inappropriate places. A voice floats towards us – whose, is as yet unknown. It becomes more and more difficult for the reader to anticipate the swelling song. This voice, that of Farinata, introduces the first theme – a little arioso of Dante’s, of a beseeching nature, most typical of the Inferno:

‘O Tuscan, who goes alive through the city of fire, speaking so politely, may it please you to rest in this place. Your speech shows clearly you are a native of that noble city that I perhaps troubled too much.’ (Inferno X, 22-24)

Dante is impoverished. Dante, of ancient Roman blood, is, within, a commoner. Gentility is not characteristic of him, quite the opposite. One would have to be blind as a mole not to notice that, in the Divina Commedia, Dante has no idea how to behave, how to advance, what to say, how to bow. I am not inventing this, I learn it from Alighieri’s own numerous confessions, scattered throughout the Divina Commedia.

The inner restlessness and heavy, clumsy awkwardness, that of a tortured and driven person, that accompanies at every step this man unsure of himself, uneducated, as it were, and unable to apply an external etiquette to his inner experience – they give the poem all its charm, all its drama, working together in the background to create something in the nature of a psychological primer.

If Dante had been allowed to enter the Inferno alone, without his ‘dolce padre’ (‘sweet father’) – without Virgil that is – scandal would have inevitably erupted from the very beginning, and rather than progressing through the torments and sights, we would be witnessing the most grotesque buffoonery.

The awkwardness Virgil works to prevent, systematically straightens and corrects the course of the poem. The Divina Commedia allows us to enter the laboratory of Dante’s spiritual awareness. What to us appears outwardly as that eagle profile in its impeccable hood, from within reveals an awkwardness painfully overcome, a purely Pushkinian struggle of the young nobleman, the young poet, for social dignity and position. The image, the shadow, enough to strike fear into children and old women, was itself full of fear – as Alighieri was hurled from the fire to the cold: from wondrous fits of conceit to an awareness of his complete insignificance.

Dante’s fame has, hitherto, been the greatest hindrance to knowledge and deep study of his works, and will remain so for a long time to come. His lapidarity, his conciseness and expressiveness, is the product of nothing less than an enormous inner imbalance, which manifests itself as dream performances, imaginary meetings, premeditated and exquisitely-turned remarks, nurtured by bile and aimed at the complete destruction of his enemies when the Day of Judgement comes.

Virgil, that sweetest of fathers, mentor, wise man, guardian, once again restrains the fourteenth century commoner within one who so painfully sought his place in the social hierarchy, at the same time as Boccaccio –

his close-contemporary – was enjoying a like social system, plunging into it, frolicking within it.

‘Che fai?’ – ‘What are you doing?’ – it indeed sounds like a teacher’s cry – ‘You’re mad!’

To imagine Dante's poem as a story, or even as a voice extended in one continuous flow, is absolutely wrong. Long before Bach, and at a time when large monumental organs were not yet built, but only very modest embryonic prototypes of those future monsters, when the zither was still the leading instrument, accompanying the voice, Alighieri built an infinitely powerful organ in verbal space, and already employed all its conceivable registers, exercised the stops, and roared and cooed through all its pipes.

‘Come avesse lo inferno in gran dispitto.’ (‘As if he held the Inferno in great disdain’: Inferno X, 36) is the line of verse that heralds all European demonism and Byronicism. At the same time, instead of raising his edifice on a plinth, as, for example, Hugo would have done, Dante wraps it in muteness, envelops it in dove-grey twilight, hides it at the very bottom of a misty bag of sounds.

It is played in a descending register, it falls, it sinks into the window-glass.

In other words, the phonetic light is dimmed. The grey shadows are blended.

The Divine Comedy does not so much take the reader’s time, as elevate it, like a piece of music being performed.

As it lengthens, the poem recedes from its end, and the end itself arrives by accident, and sounds much like a beginning.

The structure of the Dante monologue, founded as if on the registers of an organ, can be best understood by an analogy with stone, the purity of which is marred by intrusive foreign bodies.

Grainy admixtures, and veins of lava, point to an isolated shift, or some catastrophe, as a common source of morphogenesis.

Dante’s verses are formed, and given precise colours, in a geological manner. Their material structure is infinitely more important than their famous sculptural quality. Imagine a monument of granite or marble which, in its symbolic intent, aims not at depicting a horse or rider, but at revealing the inner structure of the marble or granite itself. In other words, imagine a granite monument erected in honour of granite, and apparently carved to reveal that concept – in that manner you may obtain a fairly clear idea of how Dante’s form and content are related.

Any unit of poetic speech – whether it be a line, a stanza, or a whole lyrical composition – must be considered as a single word. When we pronounce, for example, the word ‘sun’, we do not emit a ready-made meaning from within ourselves – this would be a semantic error – but we experience a kind of orbit.

Any word is like a bundle of sticks, that point out of it in different directions, and do not hasten one to a single publicly-endorsed point. Saying ‘sun’, we make, as it were, a vast journey, to which we are so accustomed that we travel in a dream. Poetry differs from casual speech in that it rouses us, and shakes us, in the middle of a word. Then our journey turns out to be much longer than we thought, and we remember that speaking means being forever on the road.

The semantic orbits of Dante’s cantos are constructed in a manner that approximates to starting with pit and ending with pity, beginning with axe, and ending with axis.

When he has occasion to, Dante calls the eyelids eye-lips. This is when ice crystals of frozen tears hang on the eyelashes and form a crust that makes it difficult to weep.

‘Gli occhi lor, ch’eran pria pur dentro molli,

gocciar su per le labbra, e ’l gelo strinse

le lagrime tra essi e riserrolli.’

‘Their eyes, which were only moist, inwardly, before,

gushed at the lips, and the frost iced fast the tears,

between them, and sealed them up again.’

(Inferno, XXXII, 46-48)

So, suffering crosses the senses, creates hybrids, leads to a lipped eye.

Dante employs not one form, but many forms. They are squeezed, one out of another, and can only conditionally be penned as one another.

He himself says:

‘Io premerei di mio concetto il suco’

(Inferno XXXII, 4)

‘I would squeeze the juice out of my idea, out of my concept,’ that is, the form appears to him as a process of squeezing, not as a carapace, a thing.

Thus, strange as it may seem, the form is squeezed out of the content, or concept, which, as it were, envelops it. This is a clearly Dantean idea.

But you can only squeeze something from a damp sponge, or a rag. No matter how we twist the concept about, we will fail to squeeze any form from it if it is not already a form in itself. In other words, any shaping in poetry presupposes series, periods, or cycles of forms, sounded in exactly the same way as a semantic unit is individually pronounced.

A scientific description of Dante’s Commedia, treated as a process, as a flow, would inevitably take the form of a treatise on metamorphosis, and would seek to penetrate into multiple states of poetic matter, just as a doctor who makes a diagnosis listens to the diverse unity of an organism. Literary criticism would take a methodical approach akin to that of medicine with regard to living beings.

III

Delving as far as I can into the structure of the Divina Commedia, I arrive at the conclusion that the whole poem is one single, unified, and indivisible stanza. Or rather, not a stanza, but a crystallographic figure, that is, a body. The poem is pierced, through and through, by a continuous shaping energy. It is the strictest stereometric body, one continuous development of a crystallographic theme. It is impossible to grasp with the eye, or visually conceive of this thirteen-thousand-faced thing, in all its monstrous exactness.

My lack of any clear understanding of crystallography – revealing the customary ignorance of my circle regarding that field, as regarding so many others – deprives me of the pleasure of comprehending the true structure of the Divina Commedia, but such are Dante’s amazing powers of stimulation that he awakened in me a specific interest in crystallography, and as a grateful reader – lettore – I will try to satisfy it.

This shaping of the poem transcends our understanding of writing and composition. It is much more correct to recognize instinct as its leading principle. Least of all should the approximate definitions proposed involve metaphorical improvisation. Here there is a struggle for the conceivability of the whole, for the visibility of the conceivable. Only with the help of metaphor is it possible to find a specific equivalent for the formative instinct with which Dante accumulated and poured out his terza rima.

One must imagine that it is as if bees, gifted with a brilliant stereometric instinct, were working on the creation of a thirteen-thousand-faced polyhedron, attracting more and more bees as needed. The work of those bees – all the time with an eye to the whole – varies in difficulty at different stages of the process. Their cooperation increases, and becomes more complex, as the formation of the honeycomb takes place, through which space, as it were, emerges from itself.

The bee analogy was suggested, incidentally, by Dante himself. These three lines are at the beginning of the sixteenth canto of the Inferno:

‘Gia era in loco ove s’udia il rimbombo

Dell’acqua che cadea nell’altro giro,

Simile a quel che l’arnie fanno rombo,’

‘I was already in a place where the booming

of the water, that fell, into the next circle,

sounded like a beehive’s humming,’

(Inferno XVI, 1-3)

Dante's comparisons are never descriptive, that is, purely pictorial. They always pursue the specific task of yielding an image of the structure, the internal energy. Let us take the extensive group of ‘bird’ comparisons – all those stretched-out caravans of cranes, the rooks, the classic military phalanxes of swallows, the anarchic and disorderly crows, incapable of Roman order – this group of extended similes always corresponds to an instinctive complex involving pilgrimage, travel, colonization, resettlement. Or, for example, let us take a no less extensive group of river similes depicting the birth in the Apennines of the Arno, which irrigates its Tuscan valley, or the descent into the Lombardy plain of that Alpine offspring the Po. The latter group, characterized by extraordinary spaciousness, and a gradual falling cadence from verse to verse, always leads to a complex involving culture, homeland, and sedentary citizenship, a political and national complex conditioned thus by its watersheds, as well as by the power and direction of its rivers.

The power of Dante’s similes, strange as it may seem, is directly proportional to the possibility of doing without them. They are never dictated by meagre logical necessity. Tell me, please, what was the need to equate the poem nearing the end with a garment – ‘gonna’ (in modern speech – ‘skirt’, and in medieval Italian – at best ‘cloak’ or in general ‘dress’), and to liken oneself to a tailor (Paradiso XXXII, 141-142), who – pardon the expression – has run out of material?

IV

As Dante passed further and further beyond the reach of both the audience of later generations, and of the poets themselves, he became veiled in greater and greater mystery. The author himself strove for clear and distinct understanding. For contemporaries, the process was difficult, tedious, but they were rewarded for it with knowledge. Then matters deteriorated. The ignorant cult of Dantean mysticism unfolded, magnificently devoid, like the very concept of mysticism, of any concrete content. The ‘mysterious’ Dante of French engravings appeared, consisting of a hood, an aquiline nose, and a search for something amidst the rocks. In Russia, one victim of this wilful ignorance on the part of those enthusiastic adherents of Dante who failed to read him, was none other than Blok:

‘Dante’s spirit, with aquiline profile,

Sings of the New Life to me’.

(From Alexander Blok’s poem: Ravenna)

The inward illumination of Dantean space, deduced only from structural elements, was of no interest to anyone.

Now I will show how little Dante’s first readers were occupied with his so-called mystery. I have before my eyes a photograph from a miniature of one of the earliest Dante copies of the mid-fourteenth century, in the collection of the Library of Perugia (the Biblioteca Augusta). Beatrice is revealing the Trinity to Dante. Its bright background with peacock patterns is like a cheerful piece of chintz. The Trinity is depicted above a circle of palm-trees – in the form of three ruddy, red-cheeked, merchant-like characters. Dante Alighieri is depicted as a daring young man, and Beatrice a lively, and chubby, girl. Two absolutely everyday figures: a schoolboy bursting with health addressed by an equally flourishing townswoman.

Spengler, who devoted excellent pages to Dante, nevertheless viewed him from an opera box of the German Burgtheater, and when he says ‘Dante’, one must often understand – ‘Wagner’, in the Munich production.

A purely historical approach to Dante is just as unsatisfactory as a political or theological one. The future of Dante commentary belongs to the natural sciences, when they become sufficiently sophisticated for this and develop their imaginative thinking.

I wish to refute, with all my strength, the disgraceful legend about the unrestrictedly dull coloration, the notorious Spenglerian brownness of Dante. To begin with, I will refer to the testimony of a contemporary illuminator. This miniature is from the same collection of the Perugia Library. It illustrates the first canto of the Inferno: ‘Behold the creature that I turned back from,’

Here is a description of the colours of this wonderful miniature, in a finer manner than the previous one, and quite appropriate to the text.

‘Dante’s clothes are a bright blue (‘adzura chiara’). Virgil has a long beard and grey hair. His toga is also grey. His cape is pink. The mountains are bare and grey.’

Thus, here we see bright azure and pink colours amidst smoke-grey rock.

In the seventeenth canto of the Inferno a monster named Geryon transports Dante and Virgil to the eighth circle below – a kind of super-powerful tank, besides being winged. He offers the poets his services, having been suitably attired by the sovereign hierarchy for the delivery of his passengers.

‘Due branche avea pilose infin l’ascelle:

Lo dosso e il petto ed ambedue le coste

Dipinte avea di nodi e di rotelle.

Con piu color, sommesse e soprapposte,

Non fer mai drappo Tartari ne Turchi,

Ne fur tai tele per Aragne imposte.’

‘Both arms were covered with hair to the armpits;

The back and chest and both flanks

Were adorned with knots and circles.

Tartars or Turks never made cloths

With more colour, background and embroidery:

Nor did Arachne spread such webs on her loom.’

(Inferno XVII, 13-18)

We are talking about the color of Geryon’s skin. The monster’s back, chest, and sides are covered with a variegated ornamentation of knots and shields. No brighter colours, Dante explains, are used for their carpets by either Turkish or Tartar weavers...

The brilliance of manufacture displayed by this simile is dazzling, while the perspective on commerce and manufacture granted us is, in the last degree, unexpected.

As regards theme, that of the seventeenth canto of the Inferno, dedicated to usury, is closely related to both commercial production and financial profit. Usury, in the absence of the banking system that was already urgently needed, was an evil of the age, but also a necessity, facilitating the circulation of goods around the Mediterranean. Usurers were shamed in the church and in literature, yet were nevertheless resorted to. Noble houses also indulged in usury – acting as bankers, but operating from a landowning, agrarian base – which especially angered Dante.

The landscape of the seventeenth canto is hot sandy desert, that of the Arabian caravan routes. The usurers of highest rank sit on the sand – Gianfigliacci and Ubbriachi from Florence, Scrovigni from Padua. On the neck of each of them hang bags – or amulets, or purses – their family coats of arms embroidered on a coloured background: an azure lion on a gold background for one; a goose, whiter than freshly churned butter, on a blood red background, for another; and a blue sow on a white background for a third.

Before climbing aboard Geryon and gliding into the abyss, Dante surveys this strange array of family crests. I draw your attention to the fact that the moneylenders’ bags are given to us like paint samples. The energy of the colourful epithets and the manner in which they adorn the verse eclipse the heraldry. The hues are named with a degree of professional accuracy. In other words, they are colours displayed when still on the artist’s palette, in his workshop. And what is so strange about that? Dante was familiar with painting, being a friend of Giotto, and closely followed the development of the painting schools, the changes and trends of fashion.

‘Credette Cimabue ne la pittura

tener lo campo, e ora ha Giotto il grido,

sì che la fama di colui è scura…’

‘Cimabue thought to lead the field, in painting,

and now Giotto is the cry,

so that the other’s fame is eclipsed.’

(Purgatorio XI, 94)

Having seen enough of the usurers, they seat themselves aboard Geryon. Virgil wraps his arms around Dante’s neck and tells the monstrous guardian to: ‘Make large circles, and let your descent be gentle: think of the strange burden that you carry.’ (Inferno XVII, 97-99).

The thirst for flight tormented and exhausted the people of Dante’s era no less than alchemy. It was a hunger for the penetration of space. All sense of orientation lost the poets can see nothing. Ahead is only the ‘Tartar’ ornamentation – the terrible silk robe of Geryon’s skin. Speed and direction can only be judged by the air streaming past their faces. The flying machine had not yet been invented, none of Leonardo designs for such yet existed, but the problem of gliding descent has already been solved.

And finally, a simile from falconry is employed. The manoeuvres of Geryon, in slowing down their descent, are likened to the return of an unsuccessful falcon, which, having hunted in vain, hesitates to return to the falconer's call and, once descended, flies off and perches sullenly at a distance.

Now let us attempt to analyse this seventeenth canto as a whole, but from the point of view of the organic chemistry of Dante’s imagery, which has nothing in common with allegory. Instead of retelling what is termed the content, we will look at this link in Dante’s work as a continuous transformation of the material of the poetic substratum, preserving its unity, and striving to penetrate deeper into itself.

Figurative thinking in Dante, as in any true poetry, is carried out with the help of a property of poetic matter, which I propose to call convertibility or reversibility. This development of an image can only conditionally be termed development. Indeed, imagine an aeroplane – disregarding technical feasibility – which, while travelling at full speed, constructs and launches a second machine. This flying machine, while just as precisely maintaining its own course, yet manages to assemble and release a third. For the purposes of accuracy, I will add that the assembly and launching of such a, currently infeasible, new machine, thrown out during passage, is not, for our purpose, to be deemed an additional and extraneous function of these aeroplanes in flight.

Clearly, only by stretching the term can this series of projectiles be called development, which are constructed on the move, and emerge one from the other, for the sake of preserving the integrity of the initial movement.

The seventeenth canto of the Inferno is a brilliant confirmation of the reversibility of poetic matter in the sense just described. The shape of this reversibility can be depicted in a manner something like this: knots and shields on the motley Tartar skin of Geryon – ornamented silk carpets scattered on a Mediterranean counter-top – a view of maritime trade, banking and piracy – usury and a return to the subject of Florence by means of heraldic bags with samples of unused fresh colours – a thirst for flight, prompted by oriental ornamentation, that directs the matter of the canto towards Arabian fairy tales with their deployment of flying carpets – and, finally, a second return to Florence with the help of a falcon, irreplaceable precisely because of its ineffectiveness.

Not satisfied with this truly wonderful demonstration of the reversibility of poetic matter, leaving far behind all the associative workings of the latest European poetry, Dante, as if in mockery of the slow-witted reader, after everything is unloaded, everything is exhaled, given away, lowers Geryon to the ground and is already suitably equipping him for a fresh journey, as if adjusting the feathers of an arrow yet to be set to the bowstring.

V

Of course, Dante’s drafts have not come down to us. We have no opportunity to work on the history of his text. But it does not follow from this, of course, that there were no scribbled manuscripts or that the text hatched already-formed, like Leda from the egg, or Pallas Athena from the head of Zeus. But the unfortunate distance of six centuries, as well as the incomplete nature of drafts, has played a cruel joke on us. For centuries, Dante has been written and spoken about as if he spoke directly in print.

Dante’s laboratory? That is of no concern. What does it matter to the ignorantly pious? They argue as if Dante had before his eyes a completely finished whole, before he started the work, and was engaged in the technique of casting a statue: having modelled it first in plaster, transferring its form to bronze. At best, they place a chisel in his hands and allow him to carve, or, as they like to say, ‘sculpt’. However, one little detail is forgotten: a chisel simply removes the excess, the sculptor’s draft leaves no material traces (which the public prefers) – while the progress of the sculptor’s work itself corresponds to a series of drafts.

Drafts, in that sense, are never destroyed.

In poetry, in plastic art, and in art in general, there are no ready-made things.

Here we are hindered by a habit of grammatical thinking – of putting the concept of art in the nominative case. We subordinate the process of creativity to our Russian prepositional case, and think of it as if a tailor’s dummy with a leaden heart were swaying about in various directions, undergoing sundry fluctuations according to our questioning: ‘about what?’; ‘about whom?’; ‘what?’; and ‘who?’ – in the end, affirming it in our ‘Buddhistic’ Gymnasium in the nominative case. At the same time, the finished ‘thing’ obeys indirect as well as direct cases to the same extent. Add to this, that our entire doctrine of syntax is a powerful remnant of scholasticism, and, while it has been put in its proper, serviceable place in philosophy and the theory of knowledge, and been completely replaced in mathematics, which has its own independent, original syntax – in art history we have failed to overcome this scholastic syntax, which causes colossal damage every hour.

In European poetry, those furthest away from Dante’s method and – frankly speaking – employing its polar opposite are those who are called Parnassians: Heredia, and Lecomte de Lisle. Much closer to his method is that of Baudelaire. Even closer is Verlaine, and the closest in all of French poetry is Rimbaud. Dante is by nature a mover and shaker of meaning, and a violator of the integrity of the image. The composition of his songs is reminiscent of the workings of a radio network, or the relentless circulation of mail by pigeon-post.

The safety of the vessel, the draft, in this manner, is the law of conservation of energy of the whole work. In order to reach the goal, you need to accept and take into account the wind as it blows from various, slightly different, directions. That is the law of sailing – manoeuvring.

Let us remember that Dante Alighieri lived during the heyday of sailing, and the noble art of sailing. Let us not disdain to keep in mind that he contemplated examples of how to tack and jibe while sailing. Dante deeply revered the art of contemporary navigation. He was a student of that most subtle and plastic skill, known to mankind since ancient times.

I would like to point out here one of the remarkable features of Dante’s psyche – his fear of direct answers, perhaps due to his political situation in that most dangerous, confusing and treacherous of centuries.

While the entire Divina Commedia, as has already been said, is like a vast process of being put to the question, each answer, each direct statement produced by Dante, is literally tortuous: extracted either by the midwife – Virgil, or later through the participation of the wet-nurse – Beatrice.

In the Inferno’s sixteenth canto, the conversation is conducted with the passion of prisoners: no matter how small an interval of time has gone by. Three eminent Florentines ask a question? About what? About the present state of Florence, of course. Their knees are shaking with impatience, and they are afraid to hear the truth. The answer turns out to be lapidary and cruel – and takes the form of a cry. For, Dante himself, after a desperate effort, twitches his chin, and throws back his head – and the effort in the author’s remark is no less expressive:

‘Cosi gridai colla faccia levata...’ (‘So, I cried, with lifted face…’)

(Inferno, XVI, 76)

Sometimes, Dante knows how to describe a phenomenon in such a way that absolutely nothing remains to be said. To do this, he uses a device that I would like to call Heraclitean metaphor, emphasizing the fluidity of a phenomenon with such force, and erasing it with such a flourish, that direct contemplation, after the work of the metaphor is essentially done, gains no profit from its labour. More than once I have had occasion to say that Dante’s metaphorical devices surpass our concept of composition, since our art history, enslaved to syntactic thinking, is powerless before it.

‘The eighth chasm was gleaming with flames, as numerous as the fireflies the peasant sees, as he rests on the hill, when the sun, who lights the world, hides his face least from us, and the fly gives way to the gnat down there, along the valley, where he gathers grapes, perhaps, and ploughs.

As soon as I came to where the floor showed itself, I saw them, and, as Elisha, the mockery of whom by children was avenged by bears, saw Elijah’s chariot departing, when the horses rose straight to Heaven, and could not follow it with his eyes, except by the flame alone, like a little cloud, ascending, so each of those flames moved, along the throat of the ditch, for none of them show the theft, but every flame steals a sinner.’

(Inferno XXVI, 25-42)

If you are not dizzy from this wonderful crescendo, worthy of a Bach organ fugue, then try indicating which is the second term, which the first term of the comparison here, what is being compared with what, what is the main thing here, and what is the secondary which explains it.

A form of Impressionist preparation is found in a number of Dante’s cantos. Its goal is to give in the form of a scattered alphabet, in the form of a vibrant, luminous, splash of letters, those very elements that, according to the law of the reversibility of poetic matter, ought to be combined in its semantic formulation.

So, in this introduction we behold the flickering luminous dance of the Heraclitean summer midges, preparing us for our perception of the important and tragic speech of Ulysses.

The twenty-sixth canto of the Inferno is of all Dante’s compositions the most to do with navigation, the farthest navigation, and the finest. In its resourcefulness, subtlety, exercise of Florentine diplomacy, and a kind of Greek cunning, it has no equal.

Two main parts are clearly distinguishable in the canto: a light, impressionistic preparatory section, and then the harmonious yet dramatic story told by Ulysses of his last voyage, of his entry to the Atlantic deep, and of a terrible death under the stars of an alien hemisphere.

This canto, analysed with regard to the free flow of thought, is very close to improvisation. But if you listen more carefully, it turns out that the author improvises, internally, in his beloved and cherished Greek language, using for this – only as phonetics and fabric – his native Italian dialect.

If you give a child a thousand rouble note, and then offer to exchange it for a ten-kopek coin then, of course, he will choose the exchange, and, in this manner, you can relieve him of well-nigh the whole amount by giving him something seemingly more tangible. Exactly the same thing happened with European art criticism, which nailed Dante to the engraved landscapes of Hell. No one has yet approached Dante with a geological hammer in order to reveal the crystalline structure of his rock, to study its dissemination, its opacity, its clarity, in order to evaluate it as rock-crystal, subject to the most colourful of accidents.

Our science says: distance oneself from the phenomenon – and one can comprehend it and master it. ‘Remoteness’ (Lomonosov’s expression) and comprehension are, for it, almost indivisible.

Dante’s images are always separating, and passing by. It is difficult to navigate the flow of his multi-streamed verse.

Even before we have had time to contemplate his Tuscan peasant, admired the phosphoric dance of fireflies and failed to follow Elijah’s chariot with our eyes, except by the flame alone, like a little cloud, ascending, Eteocles’ pyre has already been referenced, Penelope has already been named, the Trojan horse has already been left behind, Demosthenes has already lent Ulysses his republican eloquence, and the ship of the ancients has been fully-equipped.

Ancient times, in Dante’s understanding, sought above all, a wide perspective, the broadest view, the circumnavigation of the world. In the Ulysses Canto, the earth is already round.

This canto is about the composition of human blood, which contains ocean brine. The beginning of the journey lies in the system of blood vessels. Blood is planetary, solar, saline...

With all the convolutions of his brain, Dante’s Ulysses despises the hardening of the arteries, in the same way as Farinata despises Hell.

‘O my brothers, who have reached the west, through a thousand dangers, do not deny the brief vigil your senses have left to them, experience of the unpopulated world beyond the Sun. Consider your origin: you were not made to live like brutes, but to follow virtue and knowledge.’ (Inferno XXVI, 112-120)

A planetary metabolism is performed in the veins – and the Atlantic sucks in Ulysses, swallowing his wooden ship.

It is unthinkable to read Dante’s cantos without applying them to the present. They are made for this purpose. They are projectiles aimed at capturing the future. They require comment in the Futurum.

Time for Dante is the content of history, understood as a single synchronistic act, and vice versa: its content is the mutual grasping of time – by his companions, explorers, co-discoverers.

Dante is an anti-modernist. His modernity is inexhaustible, incalculable, and unbounded.

That is why Ulysses’ speech, convex, like the lens of a burning glass, is applicable to the war of the Greeks against the Persians, the discovery of America by Columbus, the daring experiments of Paracelsus, and the global empire of Charles the Fifth.

Canto twenty-six, dedicated to Ulysses and Diomedes, is a perfect introduction to the anatomy of Dante’s eye, so naturally adapted to revealing the very structure of the future tense. Dante had the visual accommodation of birds of prey, not adapted to being directed at a small radius: their hunting area being too large.

The words of the proud Farinata apply to Dante himself:

‘Noi veggiam, come quei ch’ha mala luce’.

‘We see like one who has imperfect vision’

(Inferno X, 100)

That is: we – sinful souls – are able to see and distinguish only the distant future, having a special gift for this. We become absolutely blind, as soon as the door to the future slams shut in front of us. And in this capacity, we are like one who struggles with twilight and, while distinguishing distant objects, fails to discern what is close by.

The commencement of a dance is strongly expressed in the rhythm of this verse of the twenty-sixth canto. Here the noblest freedom of rhythm applies. The feet fit the motion of the waltz:

‘E se gia fosse, non saria per tempo.

Cosi foss’ei, da che pure esser dee;

Che piu gravera, com’piu m’attempo.’

‘And, if it were come already, it would not be too soon:

would it were so, now, as indeed it must come,

since it will trouble me more, the older I am.’

(Inferno XXVI, 10-12)

It is difficult for us to penetrate into the last secret of a language foreign to us. It is not for us to judge; we do not have the last word. But it seems to me that precisely herein is the captivating pliability of Italian speech, which only the ear of a native Italian can fully comprehend.

Here I quote Marina Tsvetaeva, who mentions the ‘compliancy of Russian speech’ ...

If you follow, carefully, the movements of an intelligent reader’s mouth, it will seem as if they are communicating with the deaf, that is, working in such a way as to be understood even without sound, articulating each vowel with pedagogical clarity. And it is enough to see how the twenty-sixth canto sounds in order to hear it. I would say that the canto has restless, twitchy, vowels.

The waltz is primarily a flowing dance. Anything remotely similar would be impossible in ancient Hellenic or Egyptian, but conceivable in Chinese, culture – while it is the rule in modern Europe (I owe this comparison to Spengler). At the heart of the waltz is a purely European predilection for repetitive oscillatory movement, that very attention to the wave-form that pervades our entire theories of sound and light, our entire theory of matter, all our poetry, and all our music.

VI

Poetry, envy Crystallography! Bite your nails in anger and impotence! After all, it is recognized that the mathematical combinations necessary for crystal formation cannot be derived from three-dimensional space alone. You are denied the elementary respect that any piece of rock crystal enjoys!

Dante and his contemporaries were ignorant of geological time. They knew nothing of paleontological clocks carbon-dating, ciliated limestone clocks – grainy, granular, multi-layered clocks. They orbited the calendar, dividing the days into quadrants. However, the Middle Ages did not simply adopt the system of Ptolemy – it cloaked itself with it.

Aristotle’s physics was added to biblical genetics. Those two ill-adapted things refused to merge. The enormous explosive power of the Book of Genesis – the idea of spontaneous genesis – attacked the tiny island of the Sorbonne from all sides, and we would not be mistaken in saying that Dante’s people lived in the archaic world, whose whole circumference modernity’s waves washed, just as Tyutchev’s Ocean embraces the globe of the earth. (cf. his poem beginning ‘As Ocean embraces the globe, so earthly life is embraced by dreams and fancies’) It is already difficult for us to imagine how things absolutely familiar to everyone – the contents of a school primer that was a compulsory part of their education – how the whole biblical cosmogony with its Christian appendages could be perceived by educated people then quite literally, as a fresh newspaper is now, as a special issue.

And if we approach Dante from this point of view, it turns out that in the Biblical stories he saw not so much their fixedly sacred aspect, but more objects, to be played with aided by fresh reportage and passionate experimentation.

In the twenty-sixth canto of the Paradiso, Dante even conducts a personal conversation with Adam, a genuine interview. He is assisted by Saint John the Divine, the author of the Book of Revelation.

I maintain that all the elements of modern experimentation are present in Dante’s approach to tradition. Namely: the deliberate creation of a special environment for the experiment, the use of instruments the accuracy of which cannot be doubted, and the verification of the result, with its summons to clarity.

The environment of this twenty-sixth canto can be described as a solemn examination in a musical setting, and with optical instruments. Music and optics are the essence of the thing.

The paradoxical nature of Dante's ‘experimentation’ lies in his darting back and forth between example and experiment. Examples are drawn from the patriarchal sack of ancient ‘knowledge’ in order to be returned to it as soon as the need is over. The experiment, extracting from the sum of past experience these or other ‘facts’ it needs, no longer returns what it has borrowed according to the letter, but places it in circulation.

The gospel parables, the scholastic examples of elementary science, are pieces of bread that are eaten and thereby destroyed. His experimental science, removing such examples from their coherent whole, forms from them, as it were, a store of seeds – secured, inviolable, and constituting, as it were, the properties of unborn and imminent time.

The position of the experimenter in relation to his factology, insofar as he strives to link to its unique certainty, is essentially rapid, agitated, with the face turned to one side. The process is reminiscent of the positions of the waltz, I have already mentioned, since after each half-turn, the dancer’s heels, although they are together, are each time in a new and qualitatively different place. The Mephisto-waltz of experimentation that whirls our heads around was conceived, in the thirteenth-century and perhaps long before it, as a process of poetic shaping, proceeding in wave-form, through the reversibility of poetic matter, the most exacting of all matters, the most prophetic, and most indomitable.

Beneath the theological terminology, that school-primer of primitive allegory, we have overlooked the experimental dance of Dante’s Commedia – we have awarded Dante the status of a dead science, while his theology is in truth a dynamic vessel.

To a tactile hand placed on the neck of a warm jug, the jug takes on its shape precisely because it is warm. Warmth in this case is more important than form, and it is that which performs the sculptural function. In its chill form, forcibly detached from its intensity, Dante’s Commedia is suitable only for parsing with mechanical tweezers, not for reading or performing.

‘Come quando dall’acqua o dallo specchio

Salta lo raggio all’opposita parte,

Salendo su per lo modo parecchio

A quel che scende, e tanto si diparte

Dal cader della pietra in egual tratta,

Si come mostra esperienza ed arte...’

‘Just as when a ray of light bounces

from the water’s surface towards the opposite direction,

ascending at an equal angle to that at which it falls,

and travelling as far from the perpendicular line

of a falling stone, in an equal distance,

as science and experiment show…’

(Purgatorio XV, 16-21)

At the moment when Dante began to feel the need for an empirical verification of the data of tradition, when he first had a taste for what I propose to call sacred – in quotation marks – induction, the concept of the ‘Divina Commedia’ was already unfolding, and its success was already, internally, guaranteed.

The poem has its most baroque side tuned to authority – it is loudest, most orchestral when dogma, the canon, the firm words of a Chrysostom inform it. Yet the problem for us is that in authority, or, more precisely, in authoritarianism, we see only an attempted insurance against error, and do not at all understand the grandiose music of innocent trust, subtle as an Alpine rainbow, those nuances of probability and belief that Dante employs.

‘Col quale il fantolin corre alla mamma’

‘That faith, with which a little boy runs to his mother’

(Purgatorio XXX, 44)

With that trust, is how Dante flirts with authority.

A number of the cantos of the Paradiso are conducted as if within the strict environment of an oral exam. In some places one even hears the hoarse bass of the examiner and the nervous voice of the examinee. The background insertion of this grotesque genre painting (‘the oral exam’) is a necessary attribute of those noble and orchestral compositions of this third part of the Commedia. And an initial example is given already in the second canto of the Paradiso (a dispute with Beatrice about the origin of the dark spots on the moon).

In order to understand the very nature of Dante’s relationship with authority, that is, the form and method of its cognition, it is necessary to take into account both the orchestral setting of the examinee-cantos of the Comedy and the preparation of the organs of perception themselves. I am not speaking of the remarkable experiment with a candle and three mirrors, where it is proved that apparent brightness does not alter with distance, yet I cannot but note this preparation of the eye for the apperception of new things.

This preparation develops into real anatomy: Dante guesses the layered structure of the retina: ‘di gonna in gonna’ (‘from layer to layer’)

Music here is not an invited guest from the outside, but a participant in the dispute; more precisely, it promotes the exchange of opinions, links it, favours syllogistic absorption, stretches the premises, and compresses the conclusions. Its role is both as absorbent and solvent – its role is wholly chemical.

When you read Dante in depth, and with complete conviction, when you enter, wholly, the active field of poetic matter; when you match and measure your intonations with the echoes of orchestral and thematic groupings that appear every minute above that pitted and quivering semantic surface; when you begin to detect, through the smoky-crystalline stony layers of sound, the inclusions embedded in them, that is, the overtones and imaginings assigned to it not by the poetic, but by the geological mind, then the purely vocal intonational and rhythmic work is replaced by a more powerful, coordinating activity – the hegemony of the conductor’s guiding baton exerts its power over the space of the voices launched at him, standing above the voices like a more complex mathematical dimension projecting from the spatial three.

Which comes first, listening or conducting? If conducting is just an addition to the flow of the music, then what is its purpose, if the orchestra is fine in itself, if it plays flawlessly? An orchestra without a conductor, cherished like a dream, belongs to the same category of ‘ideals’ of pan-European banality as the world language Esperanto, symbolizing the linguistic ‘teamwork’ of all mankind.

Let us examine how the conductor’s baton first appeared, and we will see that it came neither too late nor too early, but exactly when it should have arrived, and it came as a new, original type of activity, creating its new regime through the air alone.

Let us hear how the modern conductor’s baton was born, or rather hatched from the orchestra.

1732 – Time (tempo, or beat) – previously marked with the foot, now usually with the hand. Conductor, conducteur, anführer (Walther, ‘Musicalisches Lexicon’)

1753 – Baron Grimm calls the conductor of the Paris Opera a chopper-of-wood, in accordance with the custom of beating time for all to hear, a custom that has dominated French opera since the time of Lully (Schünemann, ‘Geschichte der Dirigierens’, 1913).

1810 – At the Frankenhausen Music Festival, Louis Spohr conducted with a stick rolled out of paper, ‘without the least noise, and without the slightest contortion of countenance.’ (Louis Spohr’s ‘Autobiography’, cf. Adam Kars ‘History of Orchestration’, published, in Russian, by ‘Muzgiz’, the Soviet State Music Publishing House, 1932)

The conductor’s baton was born very late – a chemically active orchestra preceded it. The usefulness of the conductor’s baton is far from exhausted in its mere application. In the dance of the conductor, standing with back to the audience, the chemical nature of orchestral sounds finds expression. And this wand is far from being an external, administrative appendage or a kind of symphonic policeman that can be eliminated in an ideal state. It is nothing more than the dance of a chemical formula integrating audible actions. I also ask you not to consider it as merely an additional mute instrument, invented for greater clarity and delivering additional pleasure. In a sense, this invulnerable stick contains qualitatively all the elements of the orchestra. But how does it contain them? It lacks the scent of them, and cannot scent them. It has no scent in the same way that the chemical sign for chlorine lacks the scent of chlorine, just as the formula for ammonia lacks ammonia or the scent of ammonia.

Dante was chosen as the subject of this talk, not because I proposed to focus attention on him in order to study the classics, and sit him down at some kind of Valerii Kirpotin (the Soviet Literary historian) table d’hôte of ‘Literature’ along with Shakespeare and Leo Tolstoy, but because he is indisputably the greatest master of reversible, circulating poetic matter, the earliest, and at the same time the strongest, chemical conductor who exists only in the influxes and waves, only in the ups and downs, of poetic composition.

VII

Dante’s cantos are the scores of a specialised chemical orchestra, in which the similes are distinguishable to the outer ear, and are equivalent to impulses; and the solo parts, that is, arias and ariosos, are unique self-confessions, self-flagellations or autobiographies, sometimes short and fitting in the palm of your hand, sometimes lapidary, like epitaphs; sometimes unfolded, like a letter of commendation issued by a medieval university; sometimes highly developed, articulated, and reaching a dramatic operatic maturity, such as Francesca’s famous cantilena.

The thirty-third canto of the Inferno, containing Ugolino’s tale of how he and his three sons were starved to death in the prison tower by the Archbishop of Pisa, Ruggieri, sounds with a cello’s timbre, dense and heavy, like rancid, poisoned honey.

The density of the cello timbre is best suited to rouse expectation, and an agonized impatience. There is no force in the world that could accelerate the movement of honey flowing from a tilted bottle. Therefore, the cello could take shape, and did take shape, only when the European analysis of time had achieved sufficient success, when the thoughtless sundial, that former observer of a shadow moving over Roman numerals on the sand, had turned into a passionate accomplice in diverse torments, a martyr to the infinitesimal. The cello slows the tempo no matter how fast it is. Ask Brahms – he knows it is so. Ask Dante – he hears it.

Ugolino’s story is one of the most significant of Dante’s arias, one of those cases where a person, having received a unique opportunity to be heard, which will never arise again, is completely transformed before the eyes of the listener, plays on his misfortune like a virtuoso, and extracts from his troubles an unknown timbre hitherto unheard by anyone, even himself.

It should be firmly remembered that timbre is a structural property, like the alkalinity or acidity of a particular chemical compound. The flask is not merely a space in which a chemical reaction takes place. That would be too simple.

The cello-like voice of Ugolino, who is cloaked in an overgrown prison beard, starving, and incarcerated with his three little sons, one of whom bears the acute violin-like name Anselmuccio, pours out from a

‘Breve pertugio dentro dalla muda’

‘a narrow crack inside the tower’

(Inferno XXXIII, 22),

It swells from the sounding-box of that cell – here the cello is deeply in accord with its prison. Il carcere, the tower, complements and acoustically conditions the speech-work of this autobiographical cello.

In the Italian subconscious, prisons played an eminent role. Nightmares involving imprisonment were absorbed with the mother’s milk. The thirteenth century cast people into prison with amazing nonchalance. Ordinary prisons were open to the public, like churches or museums. The people’s concern with regard to prison was exploited both by the jailers themselves, and by the intimidating apparatus of even small Italian states. Between the prison and the free outside world there was a lively communication, reminiscent of a process of diffusion – a mutual percolation.

And here is the story of Ugolino – one of those casual anecdotes, a nightmare with which mothers frighten children – one of those pleasing horrors that is happily murmured, tossing and turning in bed, as a remedy for insomnia. It is a familiar ballad, like Bürger’s ‘Lenora’, the ‘Lorelei’ or Goethe’s ‘Erlkönig’.

In this form, it corresponds to a glass flask, readily accessible and comprehensible, regardless of the qualities of the chemical process taking place within it.

But the cello’s ‘largo’, presented by Dante on behalf of Ugolino, has its own space, its own structure, revealed through its timbre. The familiar flask, the familiar ballad, is shattered to smithereens. Chemistry begins within its architectonic drama.

‘I’non so chi tu sei, ne per che modo

Venuto se’quaggiu; ma Fiorentino

Mi sembri veramente quand’io t’odo.

Tu dei saper ch’io fui Conte Ugolino...’

‘I do not know who you are,

nor by what means you have come down here,

but when I hear you, you seem to me, in truth, a Florentine.

You must know that I am Count Ugolino…’

(Inferno XXXIII, 10-14)

‘You must know’ – ‘tu dei saper’ – the first thrust of the cello, the first protrusion of the theme.

The second cello thrust: if you don't cry now, then I don't know what can squeeze tears out of your eyes...

Here truly boundless horizons of compassion are revealed. Moreover, the compassionate one is invited to be a new partner to the tale, and this vibrating voice is already resounding from the distant future.

Moreover, I did not mention the ballad-form accidentally. Ugolino’s story is precisely a ballad in its chemical essence, although it is enclosed in a prison retort. Here are the following elements of the ballad: a father's conversation with his sons (remember Goethe’s ‘Erlkönig’: ‘The Forest King’); the pursuit of elusive speed, continuing the parallel, that is, with the ‘Forest King’; in the one case – a frantic gallop with a trembling son in his arms, in the other – a prison scene, that is, the count of dripping beats, bringing the father with four children close to being mathematically representable, but the father’s consciousness to the impossible threshold of starvation. The same leaping rhythm is given here in a hidden form – in the deaf howls of the cello, which strives with all its might to escape its situation, and gives a portrait in sound of an even more terrible, slow-speed chase, decomposing into the finest fibres.

Finally, as the cello speaks madly to itself, and squeezes question and answer from itself, Ugolino’s story is interrupted by the touching and helpless remarks of his son:

‘...ed Anselmuccio mio

Disse: “Tu guardi si, padre: che hai?”’ —

‘…and my little Anselm said to me:

“Father, you stare so, what is wrong?”’

(Inferno XXXIII, 30-31)

That is, the dramatic structure of the story itself follows from its timbre, and it is not the timbre itself that is sought for and then adopted en bloc.

VIII

It seems to me that Dante carefully studied various speech defects, listened to stutterers, lisping ill-pronounced letters, and learned much from them.

Thus, I wish to speak about the sound colours of this thirty-second canto of the Inferno.

There is a strange music from the lips: ‘abbo’ – ‘gabbo’ – ‘babbo’ – ‘Tebe’ – ‘plebe’ – ‘zebe’ – ‘converrebbe’. It is as if a wet-nurse is involved in the creation of phonetics. The lips now protrude childishly, then stretch to meet the tongue.

The labials form, as it were, a ‘figured bass’ – a basso continuo that is, the chordal basis of harmonization. Smacking, sucking, whistling, as well as chattering and clicking teeth are attached to them.

I pull out only one thread to choose from: ‘cagnazzi’ – ‘riprezzo’ – ‘quazzi’ – ‘mezzo’ – ‘gravezza’ ...

This pinched, explosive, smacking of the lips does not cease for a second.

Interspersed throughout this canto is a dictionary, what I would call an assortment of student taunts or bloodthirsty school jibes: ‘cuticagna’ – take by the nape, of the neck; ‘dischiomi’ – to strip the hair behind; ‘sonar con el mascelle’ – bark like a dog. With the aid of this deliberately shameless, deliberately infantile orchestration Dante crystallizes the soundscape of Giudecca (the circle of Judas) and Caina (the circle of Cain).

‘Non fece al corso suo si grosso velo

D’inverno la Danoia in Osteric,

Ne Tanai la sotto il freddo cielo,

Com’era quivi: che, se Tambernic

Vi fosse su caduto, o Pietrapana,

Non avria pur dall’orlo fatto cric.’

‘The Danube, in Austria, never formed

so thick a veil for its winter course,

nor the Don, far off under the frozen sky, as was here:

if Mount Tambernic in the east,

or Mount Pietrapana, had fallen on it,

it would not have even creaked at the margin.’

(Inf., XXXII, 25-30)

Suddenly, for no reason at all, a Slavic duck quacks: ‘Osteric’, ‘Tambernic’, ‘cric’ (an onomatopoeic – ‘creak’).

The ice gives forth a phonetic explosion, and cracks, yielding the names of the Danube and Don. The craving for cold of the thirty-second canto came from introducing physics to the moral idea: betrayal – frozen conscience – the chill of shame – absolute zero.

The thirty-second canto in tempo is a modern scherzo. But of what? An anatomical scherzo pursuing the degeneration of speech through onomatopoeic infantile material.

Here a new connection is revealed – food and speech. Speech is shamefully reversed, retracted – to gnaw, bite, gurgle – masticate.

The articulation of speech and eating almost coincide. A strange cicada-like phonetics is created:

‘…mettendo i denti in nota di cicogna.’

" …chattering with their bills, like storks.’

(Inferno XXXII, 36)

Finally, it should be noted that the thirty-second canto is overflowing with anatomical voluptuousness: there is one ‘whose chest and shadow, were pierced, at one blow’ (Inferno XXXII,61-62). In the same place, with a purely surgical, delight:

‘... di cui segò Fiorenza la gorgiera’

‘…whose throat was slit by Florence’.

(Inferno XXXII, 120)

And again: ‘and the uppermost set his teeth into the other, as bread is chewed, out of hunger, there where the back of the head joins the nape.’ (Inferno XXXII, 127-129)

All this dances, like to a Dürer skeleton on hinges, and leads to German anatomy.

One who kills is, after all, somewhat like an anatomist.

The executioner in the Middle Ages is, after all, something of a scientist.

The arts of war, and the executioner’s skill, haunt the threshold of the anatomical theatre.

IX

The Inferno is a pawnshop where all the countries and cities known to Dante are pledged without ransom. Its powerful design, that of infernal circles, possesses a solid frame. Its form cannot be conveyed by portraying it as a funnel. It cannot be depicted on a relief map. His ‘Hell’ hangs from an iron frame of urban selfishness.

It is wrong to think of the Inferno as something voluminous, as some kind of combination of huge circuits, deserts with burning sands, stinking swamps, Babylonian columns, and burning-hot mosques. Hell does not contain anything in itself, and has no volume, just as an epidemic, an outbreak of an ulcer or a plague, just as any infection simply spreads, without itself being spatial.

Urbanity, urbanism, hatred of a city – this is the matter of the Inferno. The circles of Hell are merely Saturn’s rings, here those of emigration. For the exile, his one forbidden, and irretrievably lost city is scattered everywhere – he is surrounded by it. I would say that the Inferno is surrounded by Florence. Dante’s Italian cities – Pisa, Florence, Lucca, Verona – those lovely civic planets – are stretched into monstrous rings, stretched into belts, returned to a foggy, gaseous state.

The anti-landscapes of the Inferno constitute, as it were, the condition for its visibility.

Imagine Fouquet’s grand experiment being performed, not by one but by many pendulums, swinging one above another. Here, space exists only insofar as it is a receptacle for their amplitudes. To crystallize Dante’s images is as unthinkable as to list the names of people who participated in the migration of peoples.

‘Just as the Flemings between Bruges and Wissant make their dykes to hold back the sea, fearing the flood that beats against them; and as the Paduans do, along the Brenta, to defend their towns and castles, before Carinthia’s mountains feel the thaw; so those banks were similarly formed, though their creator, whoever it might be, made them neither as high or as deep.’ (Inferno XV, 4-12).

Here the arcs of the polynomial pendulum swing from Bruges to Padua, delivering a course in European geography, and a lecture on engineering, urban security, organization of public works, and the national significance of the Alpine watershed for Italy.

We – crawling on our knees before such lines of verse – what have we kept from this wealth? Where are his successors, where are his disciples? What to do with our poetry, shamefully lagging, as it does, behind science?

It is terrible to think that the dazzling explosions of modern physics and kinetics were employed six hundred years before their thunder sounded, while there are no words to stigmatize the shameful, barbaric indifference towards them of the sad compositors of ready-made meaning.

Poetic speech creates its tools as it goes, and destroys them as it goes.

Of all our arts, only painting, in the new French mode, has not yet ceased to hear Dante. This is a mode of painting that elongates the bodies of horses approaching the finish line at the hippodrome.

Every time a metaphor rouses the vegetal colours of being to an articulate impulse, I remember Dante with gratitude.

We describe exactly what cannot be described, that is, the motionless texture of nature, and we have forgotten how to describe the only things that lend themselves to poetic representation by their very structure, that is, impulses, intentions, and fluctuations in amplitude.

Ptolemy has returned by the back-door!... There was no need to burn Giordano Bruno at the stake!...

Our creations are known to everyone in the womb, while Dante’s many-limbed, multi-winged and kinetically heated similes still retain their charm by not having been retold to anyone.

His ‘reflexology of speech’ is amazing – a whole science, as yet undeveloped, regarding the spontaneous psycho-physiological effect of the word on the interlocutor, on the speaker themself and on those around them – as well as the means by which he conveys the impulse for speech; signals that is, with light, a sudden desire to speak.

Here he comes closest to the wave theory of sound and light, and determines their relationship.

“Sometimes a creature struggles under a cloth, so that its intent is visible, because what covers it follows its movement: and, similarly, that primal soul made the joy, with which it came to serve my pleasure, apparent through its surface.’ (Paradiso XXVI, 97-102).

In the third part of the Commedia (the Paradiso) I find a real kinetic ballet. There are all kinds of light dance figures, including the tapping of heels at a wedding.

“The four torches stood burning in front of my eyes, and the first one, that had neared me, began to grow more intense: and became like Jupiter, if he and Mars were birds, and exchanged plumage, his silver-white for Mars’ warlike red.’ (Paradiso XXVII, 10-15).

Is it not strange? A man who is about to speak is ‘armed with a tightly drawn bow’, ‘stockpiles feathered arrows’, ‘prepares mirrors and convex lenses’, and ‘squints at the stars like a tailor threading a needle’s eye’...

This combined quotation, bringing together different parts of the Commedia, I have compiled as a naive characterization of the preparation for speech in Dante’s poetry.

These preparatory moves are even more his sphere than articulation itself, that is, the act of speaking.

Remember the wondrous supplication addressed by Virgil to the most cunning of the Greeks.

The whole of it vibrates with the softness of Italian diphthongs. With the curling, fawning, stuttering tongues of oil-lamps, murmuring round their unprotected wicks...

‘O voi, che siete due dentro ad un foco,

S’io meritai di voi mentre ch’io vissi,

S’io meritai di voi assai o poco...’

‘O you, who are two in one fire,

if I was worthy of you when I lived,

if I was worthy of you, greatly or a little…’

(Inferno XXVI, 79-81)

By their voice, Dante determines the origin, fate and character of a person, as modern medicine deduces health from the colour of the urine.

X