Publius Cornelius Tacitus

Germania

‘Gothic Buckle’

The Arts and Crafts of Our Teutonic Forefathers - Gerard Baldwin Brown (p204, 1910)

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2015 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Section 1: The land of the Germans

- Section 2: Their origins

- Section 3: Hercules and Ulysses

- Section 4: The German physique and nature

- Section 5: Natural resources

- Section 6: Weapons and warfare

- Section 7: Military structure

- Section 8: The role of women

- Section 9: Worship of Mercury, Mars, Isis and Hercules

- Section 10: Divination

- Section 11: Their method of government

- Section 12: Crime and punishment

- Section 13: Rank and status

- Section 14: Their eagerness for warfare

- Section 15: Their idleness in peace

- Section 16: Housing

- Section 17: Clothing

- Section 18: Marriage

- Section 19: Female chastity

- Section 20: Raising of children

- Section 21: Reparation and hospitality

- Section 22: Their banquets

- Section 23: Their diet

- Section 24: Their pastimes

- Section 25: Slaves and freedmen

- Section 26: Land management

- Section 27: Funeral rites

- Section 28: Migrations of the Germans and Gauls

- Section 29: The Batavi and Mattiaci

- Section 30: The Chatti – military capabilities

- Section 31: The Chatti – military customs

- Section 32: The Usipi and Tencteri

- Section 33: The Bructeri, Chamavi and Angrivarii

- Section 34: The Dulgubnii, Chasuarii, and Frisii

- Section 35: The Chauci

- Section 36: The Cherusci and Fosi

- Section 37: The Cimbri

- Section 38: The Suebi

- Section 39: The Semnones

- Section 40: The Langobardi and others

- Section 41: The Hermunduri

- Section 42: The Marcomani, Naristi and Quadi

- Section 43: The Marsigni, Luigi and others

- Section 44: The Suinones

- Section 45: The Aestii and Sitones

- Section 46: The Peucini, Venethi, and Fenni

Section 1: The land of the Germans

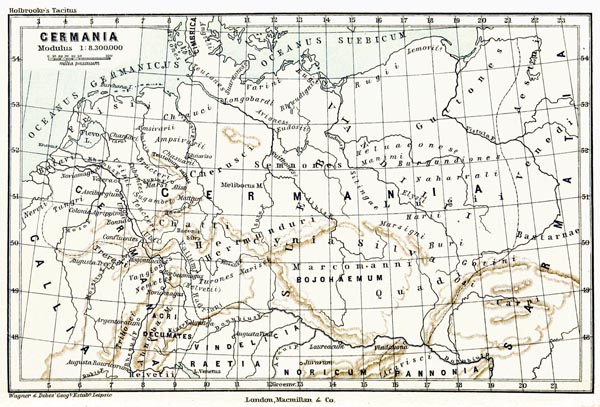

Germany, in its entirety, is separated from the Gauls, Raetians, and Pannonians by the Rhine and the Danube; and from the Sarmatians and Dacians by mountain ranges and mutual distrust: the remainder being bordered by the ocean, which washes broad peninsulas and islands of wide extent, various of whose peoples and leaders are only recently known to us, and whom warfare has revealed. The Rhine, rising from the precipitous and inaccessible heights of the Raetian Alps, after flowing in a slightly westerly direction, joins the North Sea. The Danube falling gently and gradually from the ridge of Mount Abnoba (the heights of the Black Forest) visits further peoples, until it flows, through six of its outlets, into the Black Sea: its seventh mouth being lost in the marshes.

‘Germania’

The Annals of Tacitus. Edited, with Notes, by G. O. Holbrooke - Cornelius Tacitus, George O. Holbrooke (p106, 1882)

The British Library

Section 2: Their origins

As for the Germans themselves, I believe them to be indigenous and only minimally diluted through immigration by, or alliance with, other races, since those who have previously sought to change their homeland have arrived in ships and not by land, while the vast ocean beyond, and at the opposite end of the earth, so to speak, from us, is rarely visited by vessels from our world. Moreover, even ignoring the dangers of fearful unknown seas, who would leave Asia Minor, Africa or Italy to seek out Germany, a wild land with a harsh climate, dismal in aspect and culture unless it is one’s own homeland?

Their traditional chants, the only kind of record or history they possess, celebrate a god, Tuisto, born of the earth. To him they assign a son Mannus, the origin of their race, and to him in turn three sons, the founders, from whose names the tribes nearest the ocean derive their appellation of Ingaevones, those in the centre that of Herminones, and the rest that of Istaevones. Some, with the licence due antiquity, declare the existence of further sons of the god, and additional tribal appellations, the Marsi, Gambrivii, Suebi, and Vandilii, and that these are the true and ancient names. Moreover, that the designation ‘Germany’ is a recent and late addition, and indeed the first tribes to cross the Rhine and drive out the Gauls, now called the Tungri, were then called Germans: the tribal name, while not yet the name of a nation, gradually increasing in usage, as they became known by the adopted name of ‘Germans’ first to their conquerors, on account of the apprehension roused, and later among themselves.

Section 3: Hercules and Ulysses

They also claim that Hercules appeared amongst them, and on the eve of battle they sing of that bravest of all men. They also have a species of chant, they call baritus, the repetition of which inspires courage, and they divine the outcome of an imminent battle from the cry itself; they instil or show fear depending on the sound the warriors make, seeming to them not so much a concord of voices as of hearts. They principally affect a harshness of sound, a subdued roaring, their shields close to their mouths so that the voice echoing might achieve a fuller and deeper note.

To continue, Ulysses also, in the opinion of some authorities, during his long and fabulous wanderings was carried into this ocean, and reached the shores of Germany. Asciburgium (Asberg), sited on the banks of the Rhine and inhabited today, was founded and named by him; and also an altar dedicated by Ulysses, with the name of his father Laertes inscribed, was found in the same place, and tumuli and memorial stones carved with Greek letters are still extant in the borderlands between Germany and Raetia. I am not minded to confirm or refute these statements: each according to his opinion may diminish or augment their credibility.

Section 4: The German physique and nature

For myself I agree with the opinion of those who hold that the German peoples show no traits of intermarriage with other races, being individual, pure, like none other but themselves, such that all, so far as is known with regard to their extensive population, share a common physique: eyes which are fierce and blue in colour, reddish hair, and large frames unsuited to sustained effort: not being therefore tolerant of labouring and working hard, and little able to stand heat and thirst; but used to hunger and cold given their soil and climate.

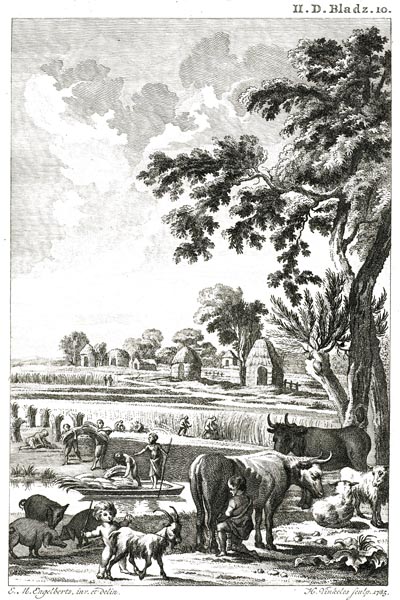

Section 5: Natural resources

There are variations in the appearance of their terrain, but generally speaking it consists of either dense forest or unhealthy marsh, damper towards Gaul, windier towards Noricum and Pannonia: good for cereal crops, hostile to fruit trees, rich in livestock though the animals are, for the most part, undersized. The cattle are neither handsome nor possess majestic brows: boasting numbers only, but are the people’s sole and welcome means of wealth.

‘Germanic Livestock and Agriculture’

Harmanus Vinkeles, 1785

The Rijksmuseum

The gods have them denied gold and silver, whether from mercy or in anger I cannot say (not that I would claim Germany devoid of gold or silver bearing veins, for who has explored it thoroughly?), though the people scarcely miss the possession or use of such metals. Silver vases may be seen there, gifted to their envoys and chieftains, but treated as of no more value than if they were made of clay; nevertheless the tribes closest to us treat gold and silver as precious metals for trade purposes, recognising and accepting certain coins of ours; though in the interior they simply barter goods in the primitive and ancient way. They prefer old and long-familiar coinage, for example the denarii with notched edges, stamped with a two-horse chariot. They rate silver more than gold, not because they are weak-minded, but because small silver coinage is more useful for common, low-cost purchases.

Section 6: Weapons and warfare

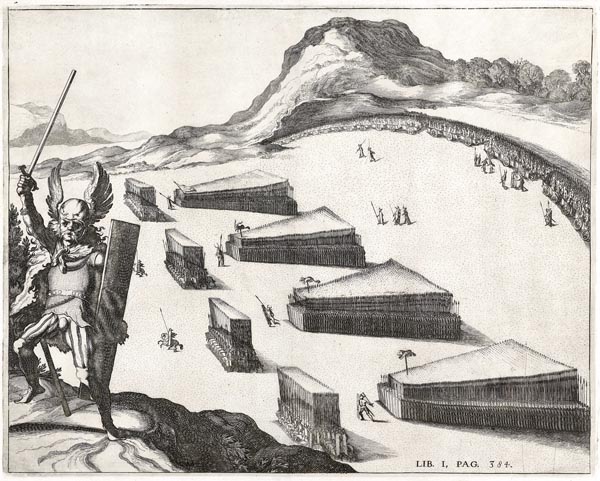

Even iron is not abundant, as may be seen from their types of weaponry. Swords or the longer style of lance are rarely employed: they carry short spears, frameae in their vocabulary, with a short narrow blade, but so sharp and effective in use that they fight with the same weapon at close quarters or a distance, as circumstances demand. Their horsemen too are content with a shield and a framea: while the foot soldiers, naked or wearing only a light cloak, launch showers of the missiles, each hurling a volley over a wide space.

They boast no ornamentation, except that their shields are adorned with various colours. They own few breast-plates, while one or two at most have casques or helms. Their horses are noted neither for form nor speed; nor are they trained like ours to manoeuvre in a variety of directions: they are ridden straight forwards, or wheeling in a single movement to the right, turning together so that none are left behind. By common judgement more strength is accorded their foot-soldiers, and so all forces combine, with swift-footed warriors, skilled and apt for cavalry actions, being selected from the ranks of infantry. Their numbers are maintained at one hundred men from each canton: and that force labelled as such, ‘the hundred’, amongst them, so that what was once a mere number is now a badge of honour. Their armies are disposed in wedge formation. Yielding ground they consider a tactic and not evidence of cowardice, so long as one attacks again. They carry off their dead and wounded even in battles having an uncertain outcome. To abandon one’s shield is the height of disgrace, men so shamed refused attendance at religious rites or council gatherings: many survivors of warfare end their shame with a noose.

‘Germanic Troops’

Simon Frisius, 1616

The Rijksmuseum

Section 7: Military structure

They acknowledge chieftains on grounds of birth, but appoint their generals on grounds of courage, nor is a chieftain’s power unlimited or exercised arbitrarily, while their generals lead rather by example than command, through admiration for their energy, and conspicuousness in the front rank. For the rest only their priests are allowed to inflict capital punishment, imprisonment, or flogging, and then not as a penalty on a general’s orders, but as a command from the god whom they believe accompanies them to war. Certain effigies and emblems, brought from sacred groves, they carry into battle: but their greatest incitement to courage is that neither chance nor random association constitutes a squadron or a wedge, but rather family and kinship; and their partners are close by, so the woman’s wail and the children’s cries can be heard. These are the witnesses most precious to them, this is their greatest source of praise: to mothers, to wives they show their wounds, who do not shrink from demanding a sight of them, numbering the blows, and delivering food and encouragement.

Section 8: The role of women

Their tradition tells that the uncertain and wavering ranks have sometimes been given new strength by the women’s constant prayers, resolute front, and demonstration nearby that captivity, which they dread more on their women’s account than their own, is at hand, so that a tribe’s loyalty is more easily guaranteed when, with other hostages, a high-born daughter’s presence is demanded.

Moreover they believe that women possess certain sacred and prophetic powers, so they are neither scornful of consulting them, nor neglectful of their answers. We know that, under Vespasian, Veleda was long-considered a deity by many; and they once revered Albruna too, and a host of others, and not merely out of flattery or as if they were about creating goddesses.

Section 9: Worship of Mercury, Mars, Isis and Hercules

They worship Mercury (Wotan) as greatest among the gods, he whom they hold it right to propitiate on certain days with human sacrifice. Hercules (Donar) and Mars (Tiu) they placate with whatever animal life is permissible. Some of the Suebi also sacrifice to Isis: though I have not discovered the source of, and reason for, this alien worship, only that its religious emblem, in the shape of a Liburnian galley, shows that the ritual was adopted from abroad.

‘Germanic Offering’

Simon Frisius, 1616

The Rijksmuseum

They also judge, from the greatness of the divine, that a god should not be enclosed within walls, nor given the likeness of a human face, rather they consecrate woods and groves, and give sacred names to a mystery which only awe can behold.

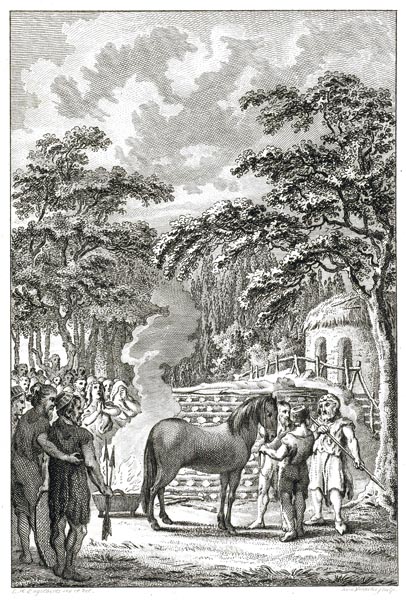

Section 10: Divination

They practise divination by lot, as readily as any people does: using a single method. A twig is cut from a nut-bearing tree, and split into slips: these are each uniquely marked, and then scattered randomly on a white sheet: next an official priest, on behalf of the people, or a patriarch in person, on behalf of his family, gazing at the sky and praying to the gods, selects three slips, one at a time, and interprets his choice according to the distinguishing marks they reveal: if the reading is negative, no further enquiry is made that day; if the reading is auspicious further confirmation by divination is sought. Though the Germans are also known to interpret the flight and calls of birds, their peculiar method is to consider the omens and premonitions arising from the behaviour of horses. Certain white ones are pastured at public expense amongst the woods and groves mentioned, and never harnessed for mundane human purposes; these they yoke to a sacred chariot bearing the priest, king or other chief of state, and they observe the horses’ neighs and snorts. Not only the people, but their leaders, and priests place their greatest reliance on such divination; regarding themselves as servants, but the horses as messengers, of the gods.

They have one further method of divination, by which they foretell the outcome of major battles. A member of the tribe with whom they are at war is captured by one means or another, and pitted against a chosen champion of their own, each man wearing his tribe’s armour. The victory of one or the other is taken as a presage of the wider result.

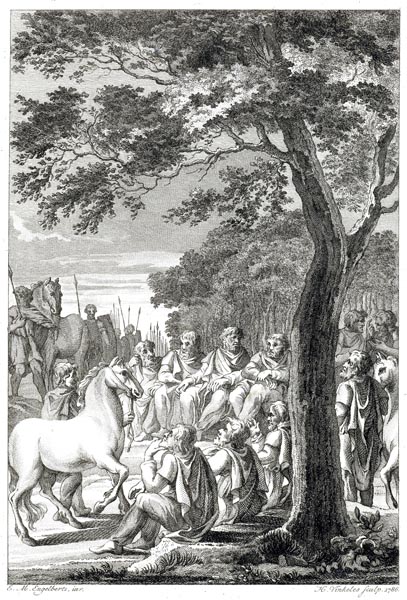

Section 11: Their method of government

The chiefs resolve minor matters, the whole tribe major ones, but with this caveat, that even those matters which the people decide are first considered by their leaders. Unless there is some sudden emergency, they gather on particular days when the moon is new or at the full, believing those to be the most auspicious moments to initiate discussion. They reckon not by the days, as we do, but by the nights. So they appoint things, so they frame their agreements: the prior night being seen to determine the requisite day.

It is the fault of their love of liberty that they do not meet at once when commanded to do so, but two or three days may be wasted by their tardiness in assembling. Those gathered take their seats when it pleases them, fully armed. The priests, owning the right to insist, demand silence. Then chiefs or other leaders speak, according to seniority, status, military achievement, or eloquence, with authority to advise rather than power to command. If their suggestion displeases, it is rejected with groans; if it finds favour there is a clashing of spears: such expression of assent by martial acclaim is the most esteemed.

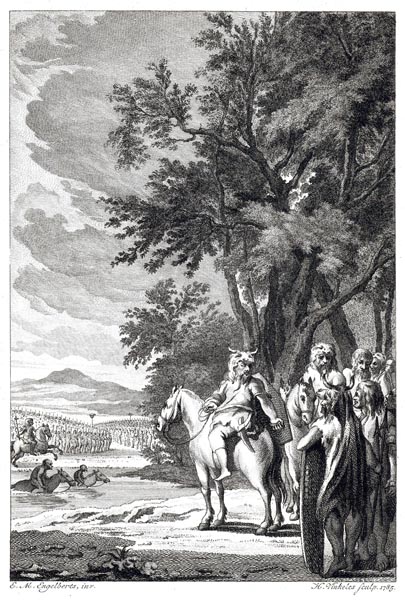

‘Germanic Council Meeting’

Harmanus Vinkeles, 1786

The Rijksmuseum

Section 12: Crime and punishment

Accusations may be made, and capital charges laid at this council meeting also. The death penalty varies with the offence. Deserters and traitors are hung from trees; cowards, objectors and deviants are drowned in muddy marshes under a wooden hurdle. The difference in method of execution reflects this: that certain crimes should be highlighted by the punishment, but the most shameful concealed. Lighter offences are punished accordingly: those convicted pay a fine of horses or cattle, part of which goes to the chief or the tribe, part to the victim or his relations. They also elect, among others, at these gatherings, the chiefs who will maintain the law through the villages and cantons, each man being assigned a hundred assistants from the people to act as his authorised advisors.

Section 13: Rank and status

They undertake no business, public or private, without being armed, though it is the custom that no man is allowed weapons until the community has approved his competence. His father, or relations, or one of the chiefs presents the young warrior with shield and spear: it is the equivalent of granting the toga, the first youthful honour. Prior to that he is seen as part of the household, afterwards a subject of the state. High birth, or great paternal merit, win distinction from the leadership, even for the very young. They mix with the stronger, more mature warriors, proven by previous service, and are not ashamed to be seen among their followers. Rank is indeed observed among such a retinue, which depends on the leader’s favour, such that there is great rivalry among his comrades as to who shall be second only to the chief, and likewise among the chieftains as to which has the largest and bravest set of followers. This is status, this is power, to be always surrounded by a large select band of young men, an adornment in peace, a defence in war. It not only brings fame and glory to a warrior among his own people, that his retinue is known for its numbers and bravery, but also among neighbouring tribes; such men being requested as ambassadors, honoured with gifts, and often their very name is enough to resolve conflict.

Section 14: Their eagerness for warfare

Once engaged in battle, it is shameful for a chieftain to be outdone in courage, shameful for his followers not to match the bravery of their leader. To desert the field and survive one’s prince indeed means a lifetime of reproach: to defend and protect him, to devote one’s deeds to his greater glory, is recognised in their primary oath of allegiance: the leader fights for victory, the followers for their leader.

If the tribe in which they are born is becalmed in a long period of peace and quiet, many noble youths, of their own will, seek tribes engaged in some war or other, because peace is unwelcome to their race, and it is easier to gain renown in troubled times. Moreover, a large retinue demands war and violence, since it is their prince’s liberality that provides the mighty warhorse, the murderous all-conquering spear, the banquets and, though coarsely-wrought, the still lavish accoutrements that serve as their pay. The basis of such munificence is through war and rapine. You will find it harder to persuade them to till the land and await the harvest, than challenge the enemy and earn their wounds. On the contrary, it seems weak and shiftless to them to acquire by sweat what you can win with blood.

‘Germanic War Exercises’

Harmanus Vinkeles, 1785

The Rijksmuseum

Section 15: Their idleness in peace

Whenever they are not engaged in war, they spend much time in hunting, more in idleness, given to food and sleep, the strongest and bravest warriors doing nothing, delegating the care of hearth and home, as well as the cultivation of their fields, to the women, the aged, and the most infirm of their household. They themselves vegetate, through that strange paradox of nature by which the same individuals both love idleness and loathe peace.

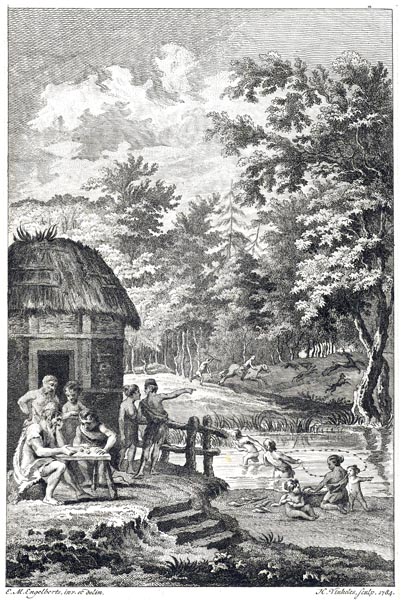

‘Hunting, Fishing and Relaxation’

Harmanus Vinkeles, 1784

The Rijksmuseum

It is a custom among the tribes for each man, freely, to grant some portion of his cattle or crops to his chieftain, which is received as an honour but also serves his needs. Their leaders value the gifts of neighbouring tribes even more highly, since they are offered by whole peoples not merely by individuals, for example choice steeds, magnificent armour, roundels and torques; while we have now accustomed them to accept coins also.

Section 16: Housing

It is well known that none of the German tribes are urbanised, homes among them not being allowed in close proximity. They live apart, scattered, as fountain, field and grove appeal to them. Their villages are not built after our fashion with buildings near together and connected, rather each man surrounds his house with a clear space, either as a precaution in case of fire, or through lack of expertise in construction. They use neither quarry-stones nor tiles, while the timber they employ for everything is uncarved, without ornament or decoration, though certain areas are coated carefully, and are bright and gleaming enough to substitute for paint and frescoes. They also excavate subterranean fogous, piling dirt on the roof, as a store and winter-shelter for produce, since such places mitigate the frost’s rigour, and if enemies attack they will lay waste all above ground, but what is hidden below is either not known of, or escapes by its very nature, its discovery requiring a thorough search.

Section 17: Clothing

All wear a cloak for clothing, fastened with a brooch or, failing that, a thorn: and otherwise naked will spend whole days round the hearth and its fire. The richest are distinguished by undergarments, not loose like Parthians or Sarmatians, but tight and moulded to the limbs. They also wear the pelts of wild creatures, those tribes by the Rhine and Danube in casual mode, the remoter tribes giving them more attention, since such are not available from merchants. The hides are choice, and those selected are ornamented with the variegated pelts of sea-creatures from the far ocean and its unknown waters.

The women’s clothing is similar to the men’s, except that the women are often veiled in linen garments striped with purple, the upper part without sleeves so that the shoulders and arms are bare, and the adjoining portion of the breast is visible.

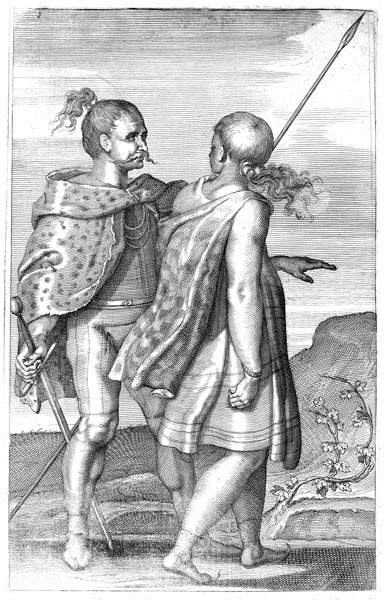

‘Two Germans’

Anonymous, 1614 - 1616

The Rijksmuseum

Section 18: Marriage

However, the marriage laws are strictly observed among them, and you will find nothing more laudable in their customs. They, almost alone among barbarians, are content with a single wife: the very few exceptions being embraced not out of libidinous desire, but to strengthen the nobility by multiple ties.

A dowry is not offered by the wife to the husband, but by the husband to the wife. The parents and relations gather round to approve the gifts, ones not designed to delight women or adorn the bride, but oxen, a horse and bridle, a shield, spear, or sword. The wife is received with these gifts, and she in turn offers some piece of weaponry to her husband. Thus marriage is sealed by an ultimate bond, a mysterious sacrament, by the gods themselves: lest the wife think herself absolved from considerations of bravery, and the fortunes of war, she is warned by the very rituals with which her marriage begins that she is to share effort and danger, to toil and venture together whether in peace or amongst conflict. This is what the yoked oxen, or bridled horse, or gift of arms denote. So must she live, so bear children: accepting what shall be handed on intact and honoured, to be received by her daughters-in-law, and passed down in turn.

Section 19: Female chastity

So the women exist, fenced-in and chaste, without seductive display, uncorrupted by the incitements of the dinner-table. The exchange of secret letters is unknown to male or female. Adultery by a married woman is infrequent considering the size of population, and its punishment is swift, being the husband’s prerogative: the husband drives her, her head shaved and her body stripped naked, from his house, in front of the relatives, and whips her through the village; there is no pardon for publicly acknowledged loss of chastity: neither beauty, youth nor wealth will find her a husband. No one laughs at vice there, no one calls corrupting or being corrupted the nature of the times. Better still are the tribes where only virgins wed, and seal it once and for all with the vows and prayers of marriage. Thus they accept one husband only, so that, as one flesh and one being, without lingering thoughts or belated desires, they might love not simply the man, but marriage itself. To limit the number of their children, or do away with a later-born child is held as an abomination, while among them fine morals have more force than fine laws elsewhere.

Section 20: Raising of children

Thus the children of every house flourish, despite nakedness and squalor, to acquire that size of body and limb at which we marvel. The mother suckles a child at her own breast, without wet-nurses and maids.

Master and servant are not distinguished by any niceties of upbringing: they live on the same earth-floor among the same cattle, until the years separate nobleman from commoner, and manhood claims them.

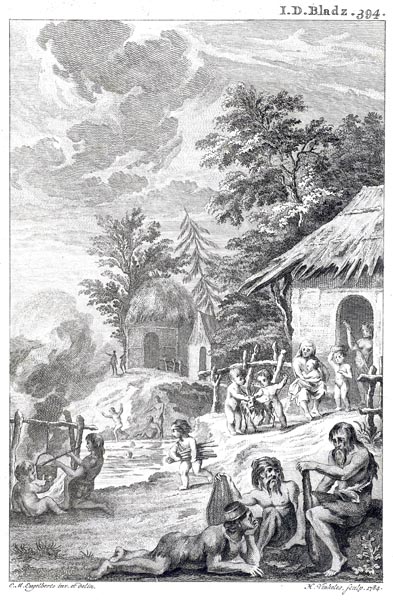

‘Domestic Life’

Harmanus Vinkeles, 1784

The Rijksmuseum

Sexuality comes late to young men, and puberty is not enfeebled; nor is girlhood forced; they are of similar stature, equals in age and maturity when they are mated, and the children reflect the parents’ vigour. A sister’s offspring are as honoured by her brother as by her husband. Some tribes hold this blood-tie as closer and more sacred than that between father and son, and give it the greater stress when taking hostages, as though they thereby grasp a house more comprehensively and its ruling spirit more securely.

Yet, each man’s offspring are his heirs and successors, even without a will. If there are no children, the closest relatives to inherit are brothers, paternal uncles, then maternal uncles. The more relations a man has, and the greater the number of his connections by marriage, the more influential he is when old; there is no prize there for being without ties.

Section 21: Reparation and hospitality

A father’s or kinsman’s enmities must be pursued, no less than his friendships, though such feuds do not remain unresolved for ever: even murder is appeased by a certain number of cattle and sheep, and a whole house receives satisfaction to everyone’s advantage, since feuds are more dangerous when conjoined with freedom of action.

No people indulge more lavishly in feasting and hospitality. It is a crime to close the door to any human being. Everyone offers a well-appointed table, according to their wealth. When the time comes, he who has been your host, points out your next port of call, and accompanies you. You go to a nearby house, without invitation but that is no matter: you are received there with equal kindness. No one distinguishes between strangers or acquaintances where the laws of hospitality are concerned. It is usual to offer the parting guest anything he fancies: there is the same readiness to make requests in turn. They delight in the exchange of gifts, but neither take account of what they have given nor feel obliged to reciprocate what they have received. Manners between host and guest are always courteous.

Section 22: Their banquets

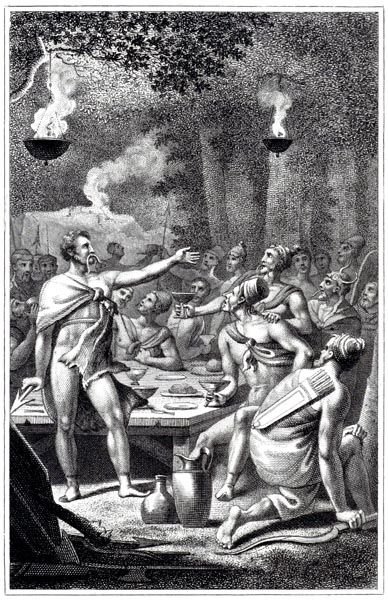

Waking from sleep, which they usually extend into the daylight hours, they wash, generally in warm water, since winter dominates so much of their lives. Having washed, they take food: each seated apart at their own table. Then to business, or as often to enjoyment, weapon in hand. It is no reproach to spend day and night drinking. Quarrels are frequent, as usual among the inebriated, seldom ended merely with invective, more often with bloodshed and wounds. Yet reconciliation between enemies, the forming of family alliances, the appointment of leaders, even questions of peace or war, are commonly debated at these banquets, as though at no time are their minds more open to honest thought or more greatly inspired. A race without cunning or guile, in the liberty such gatherings allow they expose things previously hidden in the heart; so every thought is laid bare. The next day all is reviewed, and its rightness on each occasion justified: they deliberate when incapable of pretence, and decide when free from illusions.

‘Germanic Banquet’

Philippus Velijn, 1825

The Rijksmuseum

Section 23: Their diet

They drink distillations of wheat and barley, fermented to something resembling wine: the tribes nearest the Rhine and Danube buying wine itself. Their diet is simple, wild fruits, fresh game, and curdled milk: they satisfy their hunger without undue preparation or blandishment. But there is not the same moderation where drink is concerned. If you indulge their thirst by supplying what they crave, they will be conquered by that vice as easily as they are in battle.

Section 24: Their pastimes

Their pastimes are all of one kind, and the same whatever the gathering. Youths, for whom this is sport, leap and bound between swords and menacing spears. Practice makes them skilful and skill brings grace, but not for gain or reward: however bold the sport, their only prize is the spectators’ pleasure. Gambling, surprisingly, they indulge in as a serious pastime while sober, so reckless in winning or losing, that when all else is gone, they will stake their own freedom on one further and final throw. The loser faces voluntary servitude: though the younger and stronger man, he allows himself to be bound and sold. To such an extent is their pig-headedness or, as they would term it, their honour involved in this wicked practice. Slaves, so created, they put up for sale, to absolve themselves also of the shame of such a victory.

Section 25: Slaves and freedmen

Their other servants are not, as with us, given precise roles within a household: each rules his own house and home, while his master demands a certain amount of grain or clothing or a number of cattle from him, as if he were a crofter, and with this the servant complies. The rest, the household tasks, are performed by the master’s wife and children. To beat a servant, or oppress him by hard labour or imprisonment, is rare: the death of a slave is not usually a matter of disciplinary severity but the result of a blow struck in anger, as against an enemy except that no penalty is incurred.

Freedmen are not much higher in status than slaves: rarely of much account in the household, and of none in public life, except among the predominant tribes, where they may rise above the free-born and even nobles. Elsewhere, the freedman’s inequality attests to others freedom.

Section 26: Land management

To utilise capital and increase it by levying interest is unknown; and the avoidance of it is therefore more strict in the observance than if it were prohibited. The land is claimed, area by area, by whole communities according to their number of farmers, and then allocated among these on the basis of rank, the distribution facilitated by the wide tracts of country available. They change the fields under cultivation annually, and there is still land to spare. Nor do they task the soil’s fertility and yield by planting orchards, setting apart water-meadows, or irrigating market gardens. Grain is their only harvest, so that the year is not split into as many agricultural seasons as ours: winter, spring and summer are acknowledged and so designated, but the name and the fruits of autumn are unknown.

Section 27: Funeral rites

Their funerals are unostentatious: their only observance is to cremate the bodies of their prominent men on a pyre made of choice woods, but free of perfumes and palls: to each man is his armour, while for some the body of their charger helps fuel the flames. The tomb is a mound of turf: they reject the labour and difficulty of building a monument that would weigh too heavily on the dead. They soon cease weeping and lament; while sorrow and sadness linger. It is honourable for the women to mourn, while the men simply remember those gone.

All this we have established regarding the common origins and customs of the German people: I will now describe the customs and habits of the various tribes, in as much as they differ from one another, and explain which of them have migrated from Germany to the Gallic provinces.

‘Germanic Funeral Rites’

Reinier Vinkeles, 1788 - 1790

The Rijksmuseum

Section 28: Migrations of the Germans and Gauls

It is recorded, on the supreme authority of Julius Caesar, now worshipped as divine, that the Gauls were once more powerful than the Germans; and therefore it is credible that they crossed into Germany. There was little likelihood of the rivers preventing each tribe, as it grew in strength, from seizing the common land, not yet divided into mighty kingdoms, and occupying it in turn. So, the country between the Hyrcanian Forest and the rivers Rhine and Main was taken by the Helvetii, and that beyond by the Boii, both Gallic tribes. The name Bohemia is still in use, a historical witness to its ancient occupants, despite the changes.

It is however uncertain whether the Illyrian Aravisci migrated into Pannonia from the region of the Osi, or the Osi into Germany from that of the Aravisci, since their language, customs and manners remain the same, there being originally an equal degree of freedom and equal deprivation on either bank of the river, the same advantages and disadvantages.

Conversely the Treveri and Nervii are keen to claim a Germanic origin, as though this noble ancestry distances them from any affinity with the sluggish Gauls.

Along the banks of the Rhine itself live tribes that are indisputably German: Vangiones, Triboci, Nemetes. Not even the Ubii, though they have earned the right to form a Roman colony (Cologne), and prefer to be called Agrippinenses from their founder, are embarrassed by their origins, having previously crossed the river and, after proving their loyalty, been stationed on the banks of the Rhine, not so as to be under observation, but as a barrier to others.

Section 29: The Batavi and Mattiaci

The bravest of all these tribes are the Batavi, scarce along the Rhine, but occupying an island fork in its stream. Once part of the Chatti, they crossed the river, due to domestic conflict, to a region that brought them into the Roman Empire. That distinction and the mark of ancient alliance persists; since they are not insulted by having to pay tribute, and are not oppressed by taxes. Exempted from the burden of contribution, singled out only for battle, they are reserved for war, like weapons and armour. The tribes of the Mattiaci, are part of the same system of alliances; for the greatness of the Roman people has inspired reverence beyond the Rhine, our former frontier. By location and boundaries they belong to the far bank, but in mind and spirit they act with us, similar to the Batavi in other respects except in so far as the climate and soil of their land of themselves induce in them greater animation.

‘The Coming of the Batavians’

Simon Fokke, 1725 - 1784

The Rijksmuseum

I will not number those tribes who cultivate the ‘ten cantons’ among the German peoples, even though they have established themselves beyond the Rhine and Danube. All the most fickle of the Gauls, rendered audacious by deprivation, occupied that doubtful region; which is, now the frontier has been extended and the garrisons pushed forward, regarded as a corner of the Empire and part of a province (Upper Germany).

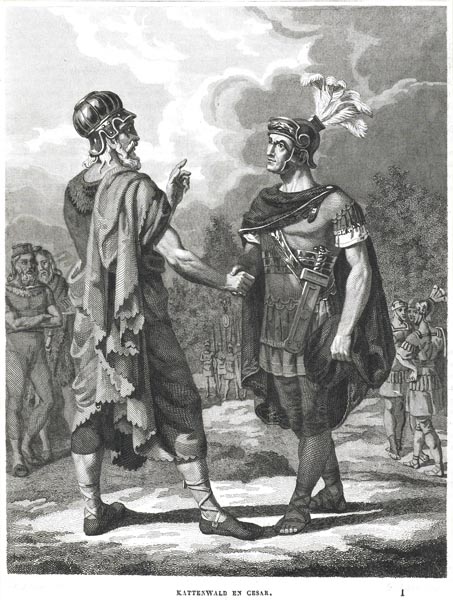

Section 30: The Chatti – military capabilities

Beyond, with the Hercynian uplands, begin the first settlements of the Chatti. Their land is not as level and marshy as that of the other territories comprising Germany; but though the hills are extensive they gradually thin out, and the Hercynian forest after embracing its Chatti finally deposits them in the plain. The tribe has a tougher physique, with tight-knit limbs and a threatening look, than the others, and greater mental vigour. They show a substantial degree of method and expertise, for Germans: they appoint men of their own choice, listen to those appointed, observe rank, perceive opportunities, delay their attacks, organise during daylight hours, retrench at night, distrust luck and depend on courage, and rarest thing of all, except where Roman discipline pertains, rely more on the commander than on his men.

Their whole strength is in their infantry, whom beside their weapons they weigh down with iron implements and baggage: other tribes seem prepared for a fight, the Chatti for a war. Forays and chance encounters are infrequent: the latter being a strength more of cavalry squadrons, suddenly winning ground and as suddenly retiring: while for infantry speed may become panic, just as caution is allied to steadiness.

‘Kattenwald, Leader of he Chatti, Shakes Hands with Julius Caesar’

Dirk Jurriaan Sluyter, 1826 - 1886

The Rijksmuseum

Section 31: The Chatti – military customs

One practice, adopted by other German tribes only rarely, and by courageous individuals, is customary among the Chatti, namely for youths to let their hair and beard grow long on reaching manhood, and only rid themselves of what cloaks the face, and is vowed and pledged to courage, once they have killed an enemy combatant. They reveal their shorn aspect above the bloody spoils, and only then declare they have repaid the debt due their birth and are worthy of their kind and country: cowards and weaklings must remain unkempt. The bravest also wear an iron collar (a badge of shame among this people) as if fettered, until freed from it on killing an enemy: this custom is widely adopted among the Chatti, and men already grown grey are distinguished so by friends and enemies alike. Every battle is initiated by these warriors: they always form the front rank, a curious sight: and even in peacetime they submit to no tamer way of life. None has house or land or occupation: wherever they go they are feted, profligate of other’s wealth, indifferent to possessing wealth themselves, until the debility of age renders them unequal to so harsh a display of virtue.

Section 32: The Usipi and Tencteri

Closest neighbours to the Chatti are the Usipi and the Tencteri, along the Rhine where the river’s course is fixed enough as to act as a frontier. The Tencteri, besides the customary fitness for war excel in the skilled disciplines of horsemanship; the fame of the Chatti’s foot-soldiers not exceeding that of the Tencteri’s cavalry. As their ancestors appointed, so their descendants follow in turn. In such practices lie the child’s games, the rivalries of youth, and the lasting interest of old-age. Their horses are passed down along with the house, the servants, the rights of succession: but in the case of the horses not, as otherwise, to the first-born son, but to the one who is fiercest in war, and the finer warrior.

Section 33: The Bructeri, Chamavi and Angrivarii

The Bructeri used to live alongside the Tencteri: now the Chamavi and Angrivarii are said to have moved in, the Bructeri having been expelled, banished by a consensus of neighbouring tribes who hated their arrogance or were attracted by the delights of plunder, or because the gods favoured us Romans, not even begrudging us sight of the conflict. More than sixty thousand warriors fell, and not to our swords and spears, but more magnificently still simply to feast our eyes. I pray that it may last, long enduring among the nations though no source of love for us, this firm hatred of each other, since, the destiny of empire urging us on, Fortune can grant us nothing better than discord between our enemies.

Section 34: The Dulgubnii, Chasuarii, and Frisii

The Angrivarii and the Chamavi are bordered on the south by the Dulgubnii and the Chasuarii and other tribes as little known, while to the north are the Frisii, called Lesser and Greater according to their strength of numbers. These two tribes inhabit the Rhine down to the sea, and also border the large lakes that Roman fleets have navigated. We have even attempted the ocean waves themselves, and tradition suggests that there are equivalents to the Pillars of Hercules beyond, either because Hercules was actually there, or because we consent to the attribution of all such wonders to him. Germanicus was not short of daring, but the ocean denied him extensive inquiry regarding itself or Hercules. Further attempts were abandoned, it being thought more pious and reverential to believe in the works of the gods than to try and fathom them.

Section 35: The Chauci

Up to this point we have been considering western Germany; now the land sweeps away in a vast northwards curve. The first tribe encountered is the Chauci, who though occupying a stretch of the seaboard also border on the tribes mentioned, and skirt south as far as the Chatti. This immense area of land is not merely held by the Chauci, but densely populated by them. They are the noblest of German tribes, choosing to defend their vast territory through the rule of law alone. Neither grasping nor violent, living in peace and quiet, they provoke no wars, nor do they raid and plunder their neighbours. The prime argument for their virtue and strength is this, that their superiority is not founded on injustice. Yet they are prompt with arms, and if circumstances demand them, armies, with a wealth of men and horses; maintaining that reputation in peacetime.

Section 36: The Cherusci and Fosi

Bordering the Chauci and Chatti are the Cherusci, who, undisturbed for many years, have nourished an excessive and enervating placidity: a delightful but unsafe policy, since peace bordered by power and lawlessness is illusory: where force acts, discipline and righteousness are titles given to the strongest. Thus, the Cherusci, once called just and generous, are now described as spineless fools, while the victorious Chatti’s good fortune is ascribed to wisdom. The Cherusci’s decline, dragged down the Fosi, their neighbours, who are now their equals in adversity, having been merely their inferiors in prosperous times.

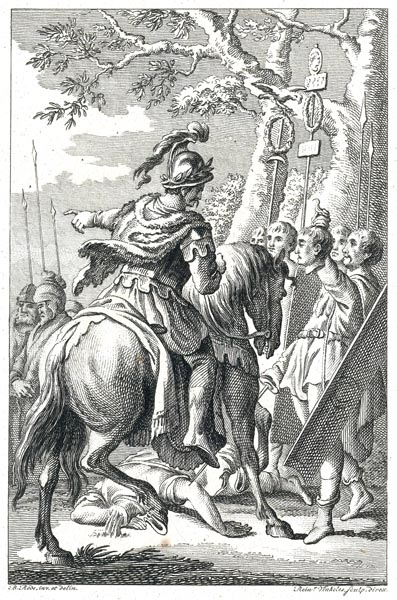

‘The Cherusci Commander Arminius Defying the Romans’

Reinier Vinkeles, 1751 - 1799

The Rijksmuseum

Section 37: The Cimbri

The Cimbri inhabit this same arm of Germany nearest the sea, a small tribe now but great in fame. Wide traces of their ancient glory remain, large encampments on both banks of the Rhine, by whose size you can gauge even today the strength and numbers of that people, witness to a vast exodus.

Rome was in its six hundred and fortieth year (114/113BC), Caecilius Metellus and Papirius Carbo being consuls, when the Cimbrian forces were first heard of. Counting from that date to the time of Emperor Trajan’s second consulship (AD98) is a space of about two hundred and ten years: so long has it taken to conquer Germany. Throughout that vast period there have in turn been many losses. The Samnites, the Carthaginians, Spain, Gaul, not even the Parthians have taught us more costly lessons: the German struggle for freedom has been fiercer than Arsaces’ for Parthian dominance.

What taunt can the East deliver, other than Crassus’ defeat (53BC), having itself lost Pacorus, a prince falling at the feet of Ventidius (38BC). While the Germans instead defeated or captured Carbo (at Noreia, 113BC) and Cassius Longinus (Garonne Valley, 107BC), Servilius Caepio and Maximus Mallius (Orange, 105BC), broke five of Rome’s consular armies in one campaign, and even snatched Varus and three legions from Augustus Caesar. It was not with impunity that Marius struck them in Italy (Raudine Plain, 101BC), the deified Julius in Gaul (58-55BC), and Drusus, Tiberius and Germanicus on German soil (12BC-AD16). Later Caligula’s vast threats turned to farce. Then little, until taking advantage of our dissension and civil war (AD69) they stormed the legions’ winter quarters, and even aimed at the Gallic countries. Finally repulsed, they have, in recent times, more often found defeat than victory.

Section 38: The Suebi

Now I must speak of the Suebi peoples, not merely a single tribe like the Chatti or Tencteri. They hold the greater part of Germany, and though generally called Suebi have also their individual tribal names. A mark of these peoples is to comb and tie their hair aslant into a dangling knot: this distinguishes the Suebi from other Germans, and the free-born Suebi from the slave. The same thing may be found in other tribes, either due to their relations with the Suebi, or from imitation, as so often happens, but it is rare and confined to youth. Among the Suebi, even till the hair turns grey, the coarse locks are twisted back, and often knotted on the crown of the head itself. The chieftains wear theirs ornamented, mindful of their appearance but in all innocence; not with a view to admiring or being admired, but being more fittingly adorned for enemy eyes, when facing battle, if they achieve a somewhat terrifying height.

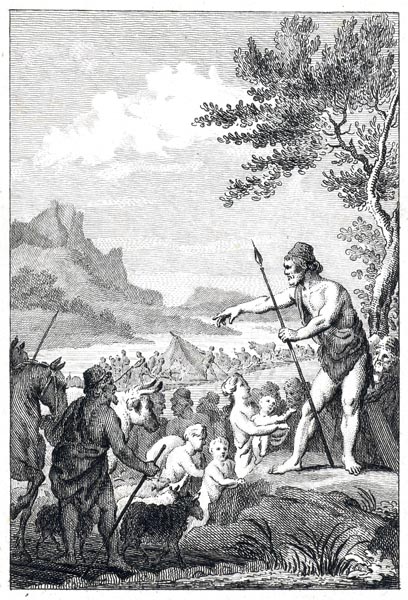

Section 39: The Semnones

They regard the Semnones as the most ancient and noblest of Suebi; the proof of their antiquity confirmed by religion. At certain times, in age-old reverence for their ancestral prophetic lore, all those of the same names and blood gather in delegations at the sacred grove, and publicly offer up a human life, as a dreadful beginning to their barbarous rites. And there is another respect they pay the grove: no one enters unless bound with rope: acknowledging by this their inferiority and the power of the deity. If they chance to stumble, they must not rise or be lifted: but crawl out over the ground: the whole superstition derives from this, that here the race arose, here dwells the god of all; all else obeys and is submissive. The Semnones’ wealth adds to this authority: they possess a hundred cantons, a number whose size leads them to believe themselves the leaders of the Suebi.

Section 40: The Langobardi and others

The Langobardi, on the other hand, are famous despite their lack of numbers: surrounded by numerous powerful tribes, they are rendered secure by a willingness to take risks and by conflict. Then there are the Reudigni, Aviones and Anglii, the Varini, Eudoses, Suarines and Nuitones, protected by rivers and forest. There is nothing notable about them individually, but they all worship Nerthus, or Mother Earth, and conceive her as intervening in human affairs, by riding among the peoples. For on an island in the sea lies a sacred grove, and in it a chariot covered with a robe, which a single priest is allowed to handle. It is he who detects the presence of the goddess in her sanctuary, following with reverence as she is drawn away in her chariot by heifers. Then there are days of rejoicing, in whichever festive places are worthy to receive and host her. They make no war, assume no arms, lock up their weapons, only then are peace and quiet known and loved, until she is sated with human society, and the priest returns her to her sanctuary. Then chariot, robe, and if you wish to believe so, the goddess herself are washed in a hidden pool: the slaves who minister to her being immediately swallowed by the waters. Hence arises a secret terror and a sacred mystery, as to what that might be that they witness only to die.

Section 41: The Hermunduri

These tribes of the Suebi extend into more distant parts of Germany: nearer to us, if I now follow the Danube’s course as a moment ago I followed the Rhine’s, is the territory of the Hermunduri, allies of Rome; with them alone among the Germans we trade not only along the river but in the interior, and with the province of Raetia’s most illustrious colony. The Hermunduri traverse the river unwatched, and while we only let others see our fortified encampments, we reveal our houses and homes to them, who are not covetous. Among the Hermunduri the River Albis (Elbe) rises, once familiar to us and famous, now little heard of.

Section 42: The Marcomani, Naristi and Quadi

Close to the Hermunduri are the Naristi, then the Marcomani and Quadi. The fame and power of the Marcomani are pre-eminent: their very land itself was won by their former expulsion of the Boii. Nor are the Naristi or Quadi inferior. These tribes are, if you wish, Germany’s brow, wreathed, so to speak, by the Danube. The Marcomani and the Quadi were ruled by kings of their own race down to our own times, the noble houses of Maroboduus and Tudrus (now they submit to foreign rulers), but the strength and power of such kings depends on Roman influence. On occasion we aid them with troops, more often with cash, which is no less valuable to them.

Section 43: The Marsigni, Luigi and others

Beyond them are the Marsigni, Cotini, Osi and Buri, enclosing the Marcomani and Quadi on their rears. Of these the Marsigni and Buri recall the Suebi in language and culture: while the Cotini’s Gallic tongue and the Osi’s Pannonian show them not to be German, as does the payment of tribute, part to the Sarmatae, part to the Quadi, which is imposed on them as foreigners. though the Cotini, more to their shame, mine iron-ore for weapons. All these tribes possess few flat areas, and mainly occupy the mountain passes and summits. An unbroken range, in fact, divides Suebia, beyond which exist a host of tribes, of the whom the most widespread by name are the Lugii, extending over several states.

It suffices to identify the strongest: the Harii, Helvecones, Manimi, Helisii, and Naharvali. Among the Naharvali a grove is shown, the seat of ancient ritual. A priest in female attire presides, but according to Roman interpretation Castor and Pollux are the gods commemorated there, that is the meaning of the divine powers, named the Alci. There are no images, no signs of imported religion, but as brothers and youths they are venerated.

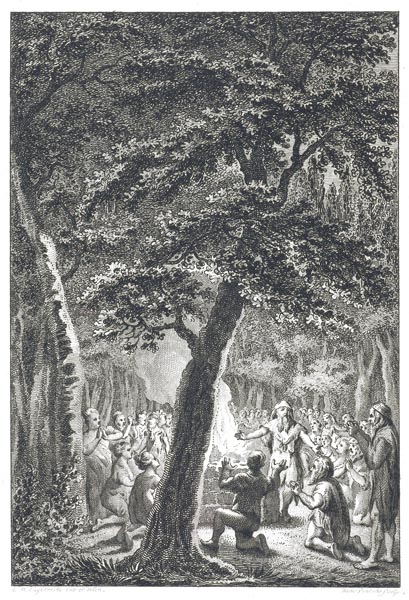

‘Worship in the Sacred Grove’

Reinier Vinkeles, 1788 - 1790

The Rijksmuseum

As for the other tribes, the Harii not only exceed those mentioned in strength but are innately fierce, enhancing their ferocity with art and timing: blackening their shields and dyeing their bodies, they choose dark nights for battle, and awful in the shadows, a deathly army, they bring terror, a novel and hellish vision no enemy dare face, for in every battle defeat first enters through the eyes.

Beyond the Lugii, the Gotones (Goths) are ruled a little more tightly than other German tribes, but not yet beyond all sense of liberty. Immediately following, by the coast, are the Rugii and Lemovii: all of these tribes display round shields, short swords, and submissiveness before their kings.

Section 44: The Suinones

Beyond there, in the very waves themselves, are the territories of the Suiones (Swedes), strong in men, arms and ships. The form of their vessels is unusual, in that a beak at either end is always ready to act as the prow driven forward. They employ neither sails, nor oars in banks at the sides, but paddle freely, as is done on certain rivers, reversing in either direction, as need arises.

Among these peoples, respect is shown to wealth, and in that matter one man rules without exception, his right to being obeyed unchallengeable. Nor is there indiscriminate bearing of arms, as among other Germans, rather they are kept under guard, and by a slave, since the sea inhibits sudden enemy incursion, and armed men without employment easily lend themselves to trouble. Nor is it, indeed, safe for the king to place a nobleman, freeman, or even freedman in charge of the weapons.

Section 45: The Aestii and Sitones

Beyond the Suiones lies another sea, dense and almost motionless, by which the land is circled and bounded; as shown by the extreme brightness of the declining sun which is so bright as to persist until dawn, dimming the stars: belief also has it that the sound of his rising is heard, and the shapes of his horses and the spikes of his crown are seen. As far as here, rumour proving true, does the natural world extend.

So, to the right-hand coastline of the Suebic Sea (Baltic), that washes the shores of the Aestii peoples, whose manners and dress are Suebic, but whose language is nearer to that of Britain. They worship the mother of the gods. As a mark of their religion they wear the emblem of the wild boar: this rather than armour or human protection renders the follower of the goddess safe even when among enemies. They use swords rarely, clubs more often. Grain and other crops they cultivate with more patience than usual among the lethargic Germans. They harvest the sea too, and they alone gather amber, which they call glesum there, in the shallows and along the shore.

Being barbarians, they have not learned or even enquired as to its nature and origin; it lay there disregarded amongst the rest of what the sea ejects, until it found fame among us as a luxury item. To them is appears useless: it is gathered in lumps and sent to Rome unshaped, and they are amazed to receive payment. Yet you may know it is tree-resin, because certain insects, even winged ones, are frequently embedded therein, which caught in its liquid state were later imprisoned there as it hardened. I would suppose therefore that as in the secret places of the East where frankincense and balsam are exuded, so in the lands and islands of the West there are certain fecund glades and groves whose resin is liquefied and, milked by the sun’s proximity, oozes into the sea, where storms deposit it on the opposing shores. If you test the nature of amber by setting fire to it, it lights like a torch and supports an oily odorous flame; later melting as if to pitch or resin.

The tribes of the Sitones adjoin those of the Suiones. Similar in other respects, they differ in this, that the women rule: in this respect they are not only inferior to freemen but even to slaves.

Section 46: The Peucini, Venethi, and Fenni

Here Suebia ends. I doubt whether to count the tribes of the Peucini, Venethi, and Fenni as German or Sarmatian, though the Peucini, whom some call Bastarnae, behave as Germans in language, manners, house, and home. All are dirty, and their chieftains lethargic; degraded somewhat in the manner of Sarmatians, through intermarriage. The Venethi have adopted much of such ways; infesting, as robbers, all the mountains and forests between the tribes of the Peucini and the Fenni.

Yet these peoples may be included among the Germans, since they have fixed abodes, carry shields, and delight in their swiftness on foot: which are all traits distinguishing them from the Sarmatians, who spend their lives in wagons or on horseback.

The Fenni live in a state of amazing savagery, and vile poverty: without armour, horses, or homes; wild plants are their food, animal pelts their clothing, the ground their bed: they place their reliance on bows and arrows, the latter tipped with sharpened bone for lack of iron. This method of hunting supports the women as well as the men; since they freely accompany the men and seek a share of the spoils. Not even their infants have any protection against wild beasts and weather, except the covering of a few woven branches: to these the young return, these are the refuge for old age. Yet they consider this better than groaning over the furrows, labouring at building huts, or involving their own fate with that of their neighbours’, in alternating hope and fear. Indifferent to human affairs, indifferent even to the gods above, they have attained that most difficult of states to achieve, they feel no need even for prayer.

All else is the stuff of fables: that the Helusii and Oxiones have the bodies and limbs of beasts, but human faces and features: that, being unknown for certain, I shall leave unresolved.

End of the ‘Germania’