Suetonius: The Twelve Caesars

Book VIII: Vespasian, Titus, Domitian

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2010 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book Eight: Vespasian (later deified)

- Book Eight: I The Flavians

- Book Eight: II Early Life

- Book Eight: III Marriage

- Book Eight: IV Military Career and Governorships

- Book Eight: V Omens and Prophecies

- Book Eight: VI Support from the Army

- Book Eight: VII Miraculous Events in Egypt

- Book Eight: VIII Strengthening the State

- Book Eight: IX Public Works

- Book Eight: X Outstanding Lawsuits

- Book Eight: XI Civil Reform

- Book Eight: XII His Modesty

- Book Eight: XIII His Tolerance

- Book Eight: XIV His Lack of Resentment

- Book Eight: XV His Clemency

- Book Eight: XVI His Cupidity

- Book Eight: XVII His Generosity

- Book Eight: XVIII His Encouragement of the Arts and Sciences

- Book Eight: XIX His Support for the Theatre

- Book Eight: XX His Appearance and Health

- Book Eight: XXI His Daily Routine

- Book Eight: XXII His Wit and Humour

- Book Eight: XXIII Quotations and Jests

- Book Eight: XXIV His Death

- Book Eight: XXV The Flavian Dynasty

- Book Eight: Titus (later deified)

- Book Eight: XXVI (I) Titus’s Birth

- Book Eight: XXVII (II) Friendship with Britannicus

- Book Eight: XXVIII (III) His Appearance and Talents

- Book Eight: XXIX (IV) Military Service and Marriage

- Book Eight: XXX (V) The Conquest of Judaea

- Book Eight: XXXI (VI) Co-Ruler

- Book Eight: XXXII (VII) His Poor Reputation versus the Reality

- Book Eight: XXXIII (VIII) His Public Benevolence

- Book Eight: XXXIV (IX) His Clemency

- Book Eight: XXXV (X) His Last Illness

- Book Eight: XXXVI (XI) His Death

- Book Eight: Domitian

- Book Eight: XXXVII (I) Domitian’s Early Life

- Book Eight: XXXVIII (II) Public Office and the Succession

- Book Eight: XXXIX (III) His Inconsistency

- Book Eight: XL (IV) His Public Entertainments

- Book Eight: XLI (V) His Public Works

- Book Eight: XLII (VI) His Campaigns

- Book Eight: XLIII (VII) His Social Reforms

- Book Eight: XLIV (VIII) His Administration of Justice

- Book Eight: XLV (IX) His Initial Moderation

- Book Eight: XLVI (X) His Degeneration

- Book Eight: XLVII (XI) His Cruelty

- Book Eight: XLVIII (XII) His Avarice

- Book Eight: XLIX (XIII) His Arrogance and Presumption

- Book Eight: L (XIV) Hated and Afraid

- Book Eight: LI (XV) Premonitions of Death

- Book Eight: LII (XVI) The Eve of Assassination

- Book Eight: LIII (XVII) His Death

- Book Eight: LIV (XVIII) His Appearance

- Book Eight: LV (XIX) His Lack of Exercise

- Book Eight: LVI (XX) His Neglect of Literature

- Book Eight: LVII (XXI) His Daily Habits

- Book Eight: LVIII (XXII) His Sexual Appetite

- Book Eight: LIX (XXIII) The Aftermath of his Death

Book Eight: Vespasian (later deified)

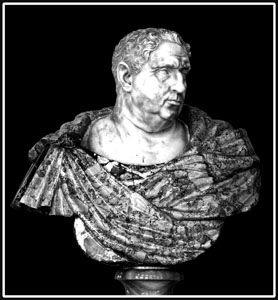

Book Eight: I The Flavians

The Flavians seized power, and the Empire, long troubled and adrift, afflicted by the usurpations and deaths of three emperors, at last achieved stability. True they were an obscure family, with no great names to boast of, yet one our country has no need to be ashamed of, even though it is generally thought that Domitian’s assassination was a just reward for his cruelty and greed.

One Titus Flavius Petro, a citizen of Reate (Rieti), a centurion or volunteer reservist under Pompey during the Civil Wars, made his way home from the battlefield of Pharsalus, and after securing his pardon and a full discharge, became a debt-collector. His son, surnamed Sabinus, took no part in military life, despite the fact that some say he was a leading centurion, others that he retired through ill-health after commanding a cohort, but collected customs-duties in Asia Minor, where for some time in various cities statues of him existed, erected in his honour and inscribed: ‘To an honest tax-collector.’ He later conducted a banking business among the Helvetii, and died there, leaving a wife, Vespasia Polla, and two sons, Sabinus, the elder, who became City Prefect, and Vespasian, the younger, the future emperor. Vespasia came of good family, her father Vespasius Pollio of Nursia (Norcia) being three times a military tribune and also camp prefect, while her brother was a Senator with praetor’s rank.

Moreover, on a hilltop, near the sixth milestone on the road from Nursia (Norcia) to Spoletium (Spoleto), at a place called Vespasiae, many monuments to the Vespasii can be seen, testifying to the family’s antiquity and renown.

I should add that some writers claim that Petro’s father, Vespasian’s paternal great-grandfather, came from beyond the River Po, and was a contractor of Umbrian labourers who crossed the river each year to work in the Sabine fields, and that he married and settled in Reate (Rieti). But I have found no evidence of this myself, despite detailed investigation.

Book Eight: II Early Life

Vespasian was born in the Sabine country, in the little village of Falacrinae just beyond Reate (Rieti), on the 17th of November 9AD in the consulship of Quintus Sulpicius Camerinus and Gaius Poppaeus Sabinus, five years before the death of Augustus. He was raised by his paternal grandmother Tertulla on her estate at Cosa and, as Emperor, would often revisit the villa he had lived in as an infant, the house being left untouched, since he wished it to remain as he had known it. He was so devoted to his grandmother’s memory that on feast days and holy days he would drink from a little silver cup that had been hers.

He waited years after his coming of age before attempting to earn the purple stripe of a Senator, already gained by his brother, and in the end it was his mother who drove him to do so, by sarcasm, rather than parental authority or entreaties, constantly taunting him with acting as his brother’s footman and merely clearing the way for him in the street.

Vespasian served in Thrace (in 36AD) as a military tribune, and as quaestor was assigned Crete and Cyrenaica by lot. He attained the aedileship (in 38AD) after a previous failed attempt, and then only in sixth place, but achieved the praetorship (in 39AD) at his first time of asking, and in the front rank. As praetor he lost no chance of winning favour with Caligula, who was then at odds with the Senate, proposing special Games to celebrate the Emperor’s German victory. He also proposed that the conspirators, Aemilius Lepidus and Lentulus Gaeticulus, should be denied public burial.

Invited to dine with the Emperor, he thanked him during a full session of the Senate, for deigning to show him such honour.

Book Eight: III Marriage

Meanwhile he had married Flavia Domitilla, formerly the mistress of Statilius Capella, a Roman knight from Sabrata in North Africa. She was only of Latin rank, but became a full citizen of Rome after her father Flavius Liberalis, a humble quaestor’s clerk from Ferentium (Ferento), established her claim before a board of arbitration. Vespasian had three children by her, Titus, Domitian, and Domitilla the Younger. He outlived his wife and daughter, both dying in fact before he became Emperor. After his wife’s death, he took up with Caenis, his former mistress, once more, she being a freedwoman and secretary to Antonia the Younger. Even after becoming Emperor, he treated Caenis as his wife in all but name.

Book Eight: IV Military Career and Governorships

Under Claudius, he was sent to Germany (in 41AD) to command a legion, thanks to the influence of Narcissus. From there he was posted to Britain (in 43AD), where partly under the leadership of Aulus Plautius and partly that of Claudius himself, he fought thirty times, subjugating two powerful tribes, more than twenty strongholds, and the offshore island of Vectis (the Isle of Wight). This earned him triumphal regalia, and a little later two priesthoods and the consulship (in 51AD) which he held for the last two months of the year. The period until his proconsular appointment he spent at leisure. in retirement, for fear of Agrippina the Younger, who held powerful influence still over her son Nero, and loathed any friend of Narcissus even after his death.

He won, by lot, the governorship of Africa (in 63AD), ruling it soundly and with considerable dignity, except when he was pelted with turnips during a riot at Hadrumetum. It is certain that he gained no great riches there, since his debts were such that he mortgaged his estates to his brother, and resorted to the mule-trade to finance his position, becoming known as the ‘Muleteer’. He is also said to have received a severe reprimand for squeezing a bribe of two thousand gold pieces out of one young man, while gaining him Senatorial rank against his father’s wishes.

He toured Greece in Nero’s retinue, but deeply offended the Emperor by leaving the room frequently while Nero was singing, and falling asleep when he was there. As a result, he was banished from favour and from court, retiring to an obscure township where he lay low, fearful of his life, until he found himself suddenly in charge of a province and in command of an army (in 66AD).

An ancient and well-established belief became widespread in the East that the ruler of the world at this time would arise from Judaea. This prophecy as events proved referred to the future Emperor of Rome, but was taken by the Jews to apply to them. They rebelled, killed their governor, and routed the consular ruler of Syria also, when he arrived to restore order, capturing an Eagle. To crush the rebels needed a considerable force under an enterprising leader, who would nevertheless not abuse power. Vespasian was chosen, as a man of proven vigour, from whom little need be feared, since his name and origins were quite obscure.

Two legions with eight divisions of cavalry and ten cohorts of auxiliaries were added to the army in Judaea, and Vespasian took his elder son, Titus, along as one of his lieutenants. On reaching his province, he impressed even the neighbouring provinces with his reform of army discipline, and his bravery in a couple of battles, including the storming of a fort at which he was wounded in the knee by a sling-stone and took several arrows on his shield.

Book Eight: V Omens and Prophecies

After the deaths of Nero and Galba, as Otho and Vitellius fought for power, Vespasian began to nurture hopes of imperial glory, which had been engendered long before by the following portents.

An ancient oak-tree, sacred to Mars, that grew on the Flavian’s suburban estate, suddenly put out a new shoot from its trunk each time that Vespasia Polla was delivered of a child, the fate of the shoot being linked to the child’s destiny. The first shoot was frail and soon withered, and so too the child, a daughter who died within a year. The second was vigorous and long indicating great future success. But the third was more like a new tree itself than a branch. Sabinus, the father, further encouraged, they say, by the favourable entrails after inspecting a sacrifice, told his mother that she now had a grandson who would become Emperor. She merely laughed, thinking, with amazement, that her son showed signs of entering his dotage while she was still of sound mind.

Later, during Vespasian’s aedileship Caligula was so angered by his dereliction of duty in not keeping the City streets clean that he ordered his guards to plaster Vespasian with mud, which they thrust into the folds of his senatorial gown. But some interpreted this as an omen that he would one day protect and embrace, as it were, his country, abandoned and trampled underfoot in the turmoil of civil war.

On one occasion a stray dog brought in a human hand that it had picked up at the crossroads, and dropped this symbol of power under the table where Vespasian was breakfasting. Again, an ox yoked for ploughing, broke free and burst into the room where he was dining, scattered the servants and, bowing its neck as if suddenly weary, fell at Vespasian’s feet. Then there was the cypress tree on his grandfather’s farm that was uprooted and levelled, despite there being no storm, yet rose again the next day greener and stronger than before.

In Greece, he dreamed that good fortune would visit him and his family when Nero next lost a tooth, and it was so the following day after the physician showed him, in the Imperial quarters, one of Nero’s teeth that he had removed.

In Judaea, Vespasian consulted the oracle of the god at Carmel, and was greatly encouraged by the promise that whatever he planned and desired, however ambitious it might seem, would be achieved. A prisoner of his, too, a nobleman named Josephus, declared that he would be released from his fetters by the very man who had ordered him chained, who would by then be Emperor.

There were omens in Rome too. Nero was warned in a dream, shortly before his death, to have the sacred chariot of Jupiter Optimus Maximus taken from its shrine to Vespasian’s house and then to the Circus. And not long after, Galba was on his way to the elections which confirmed his second consulship (69AD) when a statue of Julius Caesar turned itself to face east. Moreover, two eagles fought above the field of Betriacum before the first battle there, and when one was defeated a third flew out of the rising sun to drive off the victor.

Book Eight: VI Support from the Army

Yet Vespasian made no move, though his follower were ready and eager, until he was roused to action by the fortuitous support of a group of soldiers unknown to him, and based elsewhere. Two thousand men, of the three legions in Moesia reinforcing Otho’s forces, despite hearing on the march that he had been defeated and had committed suicide, had continued on to Aquileia, and there taken advantage of the temporary chaos to plunder at will. Fearing that if they returned they would be held to account and punished, they decided to choose and appoint an emperor of their own, on the basis that they were every bit as worthy of doing so as the Spanish legions who had appointed Galba, or the Praetorian Guard which had elected Otho, or the German army which had chosen Vitellius.

They went through the list of serving consular governors, rejecting them for one reason or another, until in the end they unanimously adopted Vespasian, who was recommended strongly by some members of the Third Legion, which had been transferred to Moesia from Syria immediately prior to Nero’s death. They had already inscribed his name on their banners, when they were recalled to their oath, and their initiative checked for a time. Nevertheless their move became known, and Tiberius Alexander, the prefect in Egypt, was the first to order his legions to swear allegiance to Vespasian, on July 1st (69AD), later celebrated as the date of Vespasian’s accession, while the army in Judaea swore allegiance to him in person on the 11th.

Momentum was enhanced by the circulation of a letter from Otho to Vespasian, whether a genuine copy or a forgery is not known, urging Vespasian to avenge him and come to the aid of the Empire; also by a rumour that Vitellius planned to move the legions’ winter quarters, transferring those in Germany to the East, and a softer and safer posting; and finally by promises of support from Licinius Mucianus, Governor of Syria, who overcame his previous hostility which had been fuelled by blatant jealousy, and committed the Syrian army to the cause, and the Parthian king, Vologases I, who offered forty thousand archers.

Book Eight: VII Miraculous Events in Egypt

So, renewing civil war, he sent his generals with their troops on to Italy, while he crossed to Alexandria to seize control of Egypt. There, dismissing his entourage, he entered the Temple of Serapis alone, to consult the auspices as to the length of his reign. After various propitiatory sacrifices, he turned at length to leave, and was greeted by a vision of his freedman Basilides, who offered him the customary sacred branches, garlands and loaves; Basilides, who had been crippled for some time by rheumatism, and who could not have been admitted to the Temple since he was far away. Almost immediately, letters arrived bearing the news that Vitellius’s army had been routed at Cremona, and the Emperor killed at Rome.

Vespasian, an unheralded and newly-forged emperor, as yet lacked even a modicum of prestige and divine majesty, but this too he acquired. As he sat on the Tribunal, two commoners, one blind the other lame, came to him, begging to be healed. Serapis had promised them in dreams that if Vespasian spat into the eyes of the one, and touched the other’s leg with his heel, both would be cured. He was dubious about attempting this, since he had little faith in the outcome, but was prevailed upon by his friends and essayed it successfully before a large crowd.

It was at this same time that, at the prompting of the soothsayers, certain antique vases were excavated from a sacred place at Tegea in Arcadia, a portrait with which they were decorated bearing a remarkable likeness to Vespasian.

Book Eight: VIII Strengthening the State

Returning to Rome (in 70AD) attended by such auspices, having won great renown, and after a triumph awarded for the Jewish War, he added eight consulships (AD70-72, 74-77, 79) to his former one, and assumed the censorship. He first considered it essential to strengthen the State, which was unstable and well nigh fatally weakened, and then to enhance its role further during his reign.

The soldiers, some intoxicated by victory, others resentful and humiliated by defeat, had abandoned themselves to every form of licence and excess. The provinces, free cities, and various client kingdoms too were riven by internal dissent. He therefore gave many of Vitellius’s men their discharge, and disciplined a host of others. However, rather than showing any special indulgence to those who had helped him secure victory, he was slow to pay them even the amounts to which they were entitled.

He seized every opportunity for improving military discipline. For example when a young man, reeking of perfume, came to thank him for the commission he had received, Vespasian turned away his head in disgust, rebuked him sternly with the words: ‘I’d rather my soldiers smelt of garlic,’ and revoked the appointment. And when the fire-brigade consisting of marines, who marched between Ostia, Puteoli (Pozzuoli), and Rome to carry out their duties, asked for an allowance to pay for footwear, he not only turned them away, but ordered that they should cover the circuit barefoot in future, which has been the practice ever since.

He abolished the free rights of Achaia (Peloponnesian Greece), Lycia, Rhodes, Byzantium and Samos, and reduced them to provincial status, along with the kingdoms of Trachean Cilicia and Commagene. He also reinforced the legions in Cappadocia against barbarian incursions, and appointed a consular governor there instead of a mere knight.

Rome was disfigured by fire-damaged and collapsed buildings, so Vespasian allowed anyone who wished to take over vacant sites and build on them, if the owners failed to do so. He personally inaugurated the restoration of the Capitol, gathering a basketful of debris and lifting it symbolically to his shoulder. He undertook to restore or replace the three thousand bronze tablets from the temple which had been damaged or lost, initiating a thorough search for copies of these venerable and beautifully-executed records of government, Senate decrees and acts of the commons, dating back to the city’s foundation, dealing with treaties, alliances, and privileges granted to individuals.

Book Eight: IX Public Works

He also undertook new public works; the Temple of Peace near the Forum; the completion (AD75) of a shrine of Claudius the God on the Caelian Mount, begun by Agrippina but almost dismantled under Nero; and an amphitheatre (the Colosseum, completed by Titus in 80AD) at the heart of the City, a project which he knew Augustus had cherished.

He reformed the Senatorial and Equestrian Orders, their ranks thinned by a series of deaths, and a long period of neglect. He increased their numbers, reviewing both lists, expelling the unworthy, and enrolling the most distinguished Italians and provincials. To make it clear that the difference between the orders was one of status rather than privilege, he decreed that in any quarrel between a knight and a Senator, the Senator must not be offered abuse, but it was right and proper to respond in kind if insulted.

Book Eight: X Outstanding Lawsuits

The list of outstanding lawsuits was excessively long, since former cases had not yet been settled due to the disruption of the legal system, and new ones had been instigated as a result of the chaos. He therefore appointed a Commission, selecting its members by lot, to settle compensation claims and whittle down the list by issuing emergency rulings in the Court of the Hundred, since it was clear that the lifetimes of the litigants would not be sufficient to resolve these matters otherwise.

Book Eight: XI Civil Reform

Licentiousness and reckless behaviour had become the order of the day, so Vespasian persuaded the Senate to decree that any woman who took up with a slave should lose her own freedom; while those lending money to sons still under their father’s legal control should be denied the right to enforce payment, even if the father died.

Book Eight: XII His Modesty

In other matters he was, from first to last, lenient, and unassuming, never trying to play down his humble origins, but even celebrating them. Indeed, when some tried to identify the origins of the Flavian family with the founders of Reate (Rieti), and with a companion of Hercules whose tomb still exists on the Via Salaria, he mocked their efforts.

He was so indifferent to pomp and outward show, that on the day of his triumph (in June AD75), wearied by the slow and tedious procession, he said openly that it served him right, for foolishly desiring a triumph in his old age, as if his ancestors were somehow owed one, or he himself were satisfying some ambition of his own.

He even delayed claiming a tribune’s powers, or adopting the title ‘Father of the Country’ until late in his reign, and even before the civil war was over he had ended the custom of searching those who attended his morning audiences.

Book Eight: XIII His Tolerance

Vespasian tolerated his friends’ outspokenness, lawyers’ quips, and the impertinence of philosophers with the utmost patience. And he only once criticised Licinius Mucianus, a notoriously lewd individual, who treated him with scant respect and traded on his past services, and then only to a friend in private, adding: ‘At least I’m a man!’

He personally commended Salvius Liberalis who while defending a wealthy client dared to ask: ‘Why should Caesar care whether Hipparchus is a millionaire?’ And when he encountered, on his travels, Demetrius the Cynic, who had been banished from Rome (in 71AD), and the philosopher made no effort to rise or salute him, merely barking out some insult, Vespasian simply addressed him as you would a dog.

Book Eight: XIV His Lack of Resentment

He was disinclined to remember, let alone repay, insults and injuries, and went out of his way to arrange a splendid match for his enemy Vitellius’s daughter, even providing her dowry and trousseau.

When, filled with trepidation, after being dismissed from Nero’s circle, he had asked an usher involved in ejecting him from the Palace what he should do and where he should go, the man had told him to go to the devil. When the same individual later begged his forgiveness, Vespasian restricted himself to a terse reply, of about the same length and content.

He was so far from inflicting death, through fear or suspicion, that when he was warned by friends to keep an eye on Mettius Pompusianus, whose horoscope indicated imperial greatness, he made the man consul, so guaranteeing his future gratitude.

Book Eight: XV His Clemency

There is no evidence of any innocent person being punished during his reign, except during his absences from Rome, and without his knowledge or at least against his wishes and by means of deception.

He was even lenient towards Helvidius Priscus, who was alone in calling him by his personal name of Vespasian, on his return from Syria, and who, as praetor (70AD) failed to honour the Emperor in superscriptions to his decrees. Vespasian showed no sign of anger until Helvidius began to undermine his status by flagrant insolence. Even then, after banishing him, and later signing his death warrant, he was still reluctant to have the execution carried out; sending men to countermand the order; and Helvidius would indeed have been saved if the messengers had not been deceived by a false report that the man was already dead.

Vespasian certainly never rejoiced at any man’s death, but rather sighed and wept over the sufferings of those who deserved punishment.

Book Eight: XVI His Cupidity

The only thing which he was guilty of was a love of money. Not content with re-imposing the taxes that Galba had repealed, he added new and heavier ones, increasing, even doubling, the tribute levy on individual provinces, and openly engaging in business dealings which would have disgraced a person of lesser rank, for instance cornering the market in certain commodities in order to offload them again at a higher price. And he thought nothing of selling public offices for cash, or pardons to those charged with offences, regardless of their guilt. He is even said to have promoted the greediest of his procurators, so that they might garner riches, before he condemned them for extortion. In fact people used to say he treated them like sponges, so they might soak up, so to speak, before being squeezed dry.

Some say Vespasian was naturally avaricious, a trait he was taunted with after he became Emperor. When an old herdsman of his begged for his freedom, and was told he must buy it, the man cried out that a fox changes its coat, but not its nature. Others however believe that necessity drove him to rob and despoil, so as to raise money, because of the desperate state of his finances and of the Privy Purse. He himself testified at the start of his reign that forty millions were needed to set the State right. Theis explanation is the more probable in that he made good use of his wealth, however questionably it was gained.

Book Eight: XVII His Generosity

He was extremely generous to all ranks, subsidising Senators who fell short of the financial requirements for office, and granting impoverished ex-consuls annual pensions of five thousand gold pieces. He also restored and improved cities damaged by fire or earthquake.

Book Eight: XVIII His Encouragement of the Arts and Sciences

Vespasian particularly encouraged men of talent in the arts and sciences. He was the first to pay teachers of Latin and Greek rhetoric a regular annual salary of a thousand gold pieces from the Privy Purse. He also awarded fine prizes and lavish gifts to eminent poets and artists, such as the restorer of the Venus of Cos and the Colossus of Nero.

When an engineer offered a low-cost contrivance enabling the transport of heavy columns to the Capitol, Vespasian paid him handsomely for his invention but declined to use the machine, saying: ‘You must allow my poor hauliers to earn their bread.’

Book Eight: XIX His Support for the Theatre

At his dedication of the new stage of the Theatre of Marcellus, he revived the former music concerts, and gave Apelles, the tragic actor four thousand gold pieces, and Terpnus and Diodorus the lyre-players two thousand each, while several actors received a thousand, the smallest gifts being four hundred. Numerous gold crowns were also distributed.

He was constantly arranging sumptuous formal dinner parties, to encourage the food and wine merchants. And he gave presents to women at the Matronalia on the 1st March and to men at the Saturnalia in December.

Nevertheless he found it hard to escape his former reputation for meanness. The Alexandrians continued to call him Cybiosactes ‘the dealer in fish-scraps’, after one of their most notoriously stingy kings. And at his death, his funeral-mask was worn by Favor a leading mimic, who gave the customary imitation of the deceased’s words and gestures in life, and called to the procurators asking how much it would all cost. When they answered a hundred thousand in gold he told them to ‘make it a thousand, and throw him in the Tiber’.

Book Eight: XX His Appearance and Health

Vespasian was well-proportioned with firm compact limbs, but always wore a strained expression on his face, such that when he prompted some wit to make a jest about him, the fellow replied: ‘I will, when you’ve finished relieving yourself.’

His health was excellent, and he took no medication, merely massaging his throat and body regularly at the ball-court, and fasting for a day each month.

Book Eight: XXI His Daily Routine

This was his daily routine. As Emperor he always arose early, before dawn in fact, read his letters and official reports, admitted his friends and received their greetings, and put on his shoes and dressed himself.

After attending to any public business, he would take a drive and then a nap, sleeping with one of the many concubines he had taken after Caenis’s death.

Following his siesta he bathed, then went off to dine, at which time they say he was at his most affable and indulgent, so that members of his household would seize the opportunity to ask their favours of him.

Book Eight: XXII His Wit and Humour

He was mostly good-natured at other times as well, not only at dinner, cracking many a joke, always ready with a quick retort, though often of a low and scurrilous nature, and not without the odd obscenity. And many of his witty remarks are remembered, among them the following.

One day an ex-consul, Mestrius Florus, took him to task for pronouncing plaustra (wagons) in the peasant manner as plostra. So the following day Vespasian greeted him as ‘Flaurus’.

Some woman declared herself dying of passion with him, so he took her to bed, giving her four gold pieces, and when his steward asked how the amount should be entered in the accounts, Vespasian told him to put down: ‘for love of Vespasian.’

Book Eight: XXIII Quotations and Jests

He was very apt with his Greek quotations, recalling Homer, for example, at the sight of a tall man with a grotesquely long penis:

‘Covering the ground with long strides, shaking his long-shadowed spear,’

And when a wealthy freedman Cerylus, changed his name to Laches and claimed to be freeborn to escape paying death duties to the State, Vespasian commented (in the spirit of Menander):

‘…O Laches, Laches,

When life’s over, once more

You’ll be Cerylus, just as before.’

But most of his wit referred to disreputable means of gaining wealth, trying to make them seem less odious with his banter, and turning them into a jest.

Vespasian once turned down a request from a favourite servant who asked for a stewardship for a man he claimed was his brother then he summoned the man himself, appropriated the commission the applicant had agreed to pay the servant, and appointed him immediately. When the servant raised the matter again, Vespasian advised him: ‘Find yourself another brother, the one you thought yours turned out to be mine.’

Suspecting, on a journey, that the muleteer had dismounted and was shoeing a mule to create a delay so a litigant could approach him, Vespasian insisted on knowing how much the muleteer had been paid to shoe the animal and promptly appropriated half.

When Titus complained about a new tax Vespasian had imposed on the public urinals, he held a coin from the first payment to his son’s nose, and asked if it smelt unpleasantly. When Titus replied in the negative, Vespasian commented; ‘Yet it’s made from piss!’

Receiving a deputation who reported that a huge statue had been voted him at vast public expense, he demanded to have it erected at once, holding out his palm and quipping that the pedestal was ready and waiting.

Even the nearness of great danger or death failed to stem the flow of his humour. When the Mausoleum of Augustus split open, he declared the portent appertained to Junia Calvina, she being of the Julian line, while the streaming tail of the comet that simultaneously appeared indicated the long-haired King of the Parthians. On his death-bed he joked: ‘Oh dear! I think I’m becoming a god.’

Book Eight: XXIV His Death

During his ninth consulship, Vespasian was taken ill in Campania, hurried back to Rome then left for his annual trip to Cutiliae and his summer retreat near Reate (Rieti). Once there, though his frequent cold baths gave him a stomach chill, worsening his illness, he still carried on his imperial duties, even receiving deputations at his bedside, until a sudden bout of diarrhoea almost caused him to faint. He struggled to get to his feet, saying: ‘An Emperor should die standing’, but expired in the arms of his attendants as they tried to help him. He died on the 23rd of June AD79, at the age of sixty-nine years, seven months, and seven days.

Book Eight: XXV The Flavian Dynasty

Everyone agrees that he had such faith in his horoscope and in those of his family that, despite a succession of conspiracies against him, he felt confident in telling the Senate no one would succeed him except his sons.

He is also said to have dreamed he saw a level pair of scales at the centre of the Palace vestibule, with Claudius and Nero standing in one pan, himself and his sons in the other. An accurate prophecy, since the total length of both sets of reigns in years was identical.

Book Eight: Titus (later deified)

(Translator’s Note: Suetonius’ chapter numbers are in brackets after mine)

Book Eight: XXVI (I) Titus’s Birth

Titus, surnamed Vespasianus like his father, possessed such an aptitude, by nature, nurture, or good fortune, for winning affection that he was loved and adored by all the world as Emperor, which was no mean task, since as a private citizen, and later when his father reigned, he had not escaped public censure, even loathing.

He was born on the 30th of December AD41, the very year of Caligula’s assassination, in a little dingy room of a humble dwelling, near the Septizonium, which is still there and can be viewed.

Book Eight: XXVII (II) Friendship with Britannicus

He grew up at court, with Brittanicus, and was taught the same curriculum by the same teachers. They say that when Narcissus, Claudius’s freedman, brought in a physiognomist to predict Britannicus’s future from his features, he was told that Britannicus would never become emperor, while Titus, who was standing nearby, surely would. The boys were so close that Titus who was dining with him when Britannicus drained the fatal dose of poison, also tasted it, and suffered from a persistent illness as a result.

Titus never forgot their friendship, and later erected a gold statue of Britannicus in the Palace, dedicating a second equestrian statue of him, in ivory, which is to this day carried in procession in the Circus, and walking ahead of it on the occasion of its first appearance.

Book Eight: XXVIII (III) His Appearance and Talents

Even as a child Titus was noted for his beauty and talent, and more so year by year. He was handsome, graceful, and dignified, and of exceptional strength, though of no great height and rather full-bellied. He had an extraordinary memory, and an aptitude for virtually all the arts of war and peace, being a fine horseman, skilled in the use of weapons, yet penning impromptu verses in Greek and Latin with equal readiness and facility. He had a grasp of music too, singing well and playing the harp pleasantly and with ability.

I have also heard from a number of sources that he could write rapid shorthand, and amused himself by competing with his secretaries for fun, and could also imitate anyone’s handwriting, often claiming he might have become a prince of forgers.

Book Eight: XXIX (IV) Military Service and Marriage

As military tribune in Germany (c57-59AD) and Britain (c60-62), he won an excellent reputation for energy and integrity, as is shown by the large number of inscribed statues and busts of him found in both countries.

After this initial army service, he pleaded as a barrister in the Forum, more for the sake of renown than as a profession. At that time he also married Arrecina Tertulla, whose father though only a knight, had commanded the Praetorian Guard (AD38-41). She died, and Titus then married (63AD) Marcia Furnilla, a lady of noble family, whom he divorced after acknowledging the daughter she bore him.

When his quaestorship ended, he commanded one of his father’s legions in Judaea, capturing the strongholds of Tarichaeae and Gamala (67AD). His horse was killed under him in battle, but he mounted that of a comrade who fell fighting at his side.

Book Eight: XXX (V) The Conquest of Judaea

He was later sent to congratulate Galba on his accession (69AD), and attracted attention throughout his journey, because of the belief that he had been summoned to Rome prior to his adoption by the Emperor.

However, he turned back after witnessing the general chaos, and consulted the oracle of Venus at Paphos regarding his voyage, the result of his visit encouraging hopes of power, which were quickly confirmed by Vespasian’s accession. His father left him to complete the conquest of Judaea, and in the final assault on Jerusalem (70AD) Titus killed twelve of the defenders with as many arrows, taking the city on his daughter’s birthday. The soldiers in their delight, hailed him with devotion as Imperator, and urged him on several occasions, with prayers and even threats, not to leave the province, or at worst to let them accompany him.

Suspicions were thus aroused that he meant to rebel against his father and make himself king in the East, a suspicion reinforced by his wearing a coronet at the consecration of the Apis bull at Memphis, on his way to Alexandria, wholly in conformance with the ceremony of that ancient religion, but nonetheless capable of an unfavourable interpretation by some.

As a result, Titus sailed on swiftly for Italy, in a naval transport, touching at Rhegium (Reggio) and Puteoli (Pozzuoli). Hurrying on to Rome, he sought to prove the rumours groundless by greeting his father unexpectedly, saying: ‘I am here, father, I am here.’

Book Eight: XXXI (VI) Co-Ruler

From then on, he acted as his father’s colleague and even protector. He shared in his Judaean triumph (of AD71), the censorship (AD73), the exercise of tribunicial power, and in seven of his consulships (AD70, 72, 74-77, 79).

Titus took it upon himself to carry out almost all official duties, issued letters and edicts in his father’s name and even executed the quaestor’s task of reading imperial speeches in the Senate.

He also assumed command of the Praetorian Guard, a post traditionally entrusted to a Roman knight, in which role he behaved in an arrogant and tyrannical manner. Whenever anyone fell under suspicion, he would send guards in secret to theatre or camp, to demand the man’s punishment, taking for granted the consent of all present, and would have him promptly executed.

Among his victims was Aulus Caecina, an ex-consul, whom he invited to dinner and then had stabbed to death as he left, almost on the very threshold of the dining room, though he was driven to it by the exigency of the moment, having intercepted an autograph copy of an address to the troops which Caecina was preparing to deliver.

Though he secured his future by such conduct, he incurred such hatred at the time that scarcely any man achieved supreme power with so adverse a reputation, or to such little acclaim.

Book Eight: XXXII (VII) His Poor Reputation versus the Reality

He was accused not only of cruelty, but of a prodigal lifestyle, involving midnight revels with riotous friends; of immorality with his troop of male prostitutes and eunuchs; and of a notorious passion for Queen Berenice, to whom he allegedly promised marriage. Another charge was that of greed, since it was well-known that he took bribes to influence cases that came to his father for judgement.

In short, it was not only suspected, but openly declared, that he would prove a second Nero. Yet his poor reputation served him well, and gave way to the highest praise, when he displayed the greatest of virtues rather than the most obvious of faults.

His dinner parties, far from being extravagant, were modest and pleasant. The friends he chose were men whom his successors retained in office, as indispensable to their service and the State’s, and of whom they made vital use. Berenice he packed off to the provinces, a move which contented neither, and he broke with several of his best-loved catamites, though they were skilful enough as dancers to find favour on the stage, and he refused to view their public performances.

He robbed no one, respecting property rights, if ever anyone did so, and indeed refused to accept rightful and traditional gifts. Nor was he inferior to his predecessors in public generosity. When the Colosseum and the hastily-erected Baths nearby were dedicated (in 80AD) he staged a magnificent and costly gladiatorial show. He also funded a mock naval battle on the old artificial lake, and used the basin for gladiatorial contests and a wild-beast show, with five thousand creatures of every species exhibited in a single day.

Book Eight: XXXIII (VIII) His Public Benevolence

Titus was naturally kind-hearted, and though, following Tiberius’s example, no emperor had previously ratified individual favours granted by their predecessors except by re-conferring them individually themselves, Titus did so with a single edict, and unprompted.

Moreover, regarding other requests, he never let any petitioner go away without a degree of hope. Even when his staff warned him he was promising more than could be performed, he said it was wrong for anyone to be disappointed by an audience with their emperor. Recalling, at dinner one evening, that he had granted no favours that day he uttered the laudable and memorable remark: ‘My friends, I have wasted a day.’

He always treated the public with great indulgence, and on one occasion declared he would give a gladiatorial show according to the audience’s wishes and not his own; and kept his word, urging them to say what they wanted and granting whatever they asked. Though he openly supported his favourites, the Thracian gladiators, he would indulge in pleasant banter with the crowd, arguing and gesturing, but without sacrificing his dignity, or his sense of fairness. And by way of seeking popular approval, he would use his newly built public baths in company with commoners.

His reign was marked by various catastrophes, such as the eruption of Vesuvius in Campania (AD79), and a disastrous fire in Rome (AD80) which burned for three days and nights, accompanied by an unprecedented outbreak of plague. He reacted not merely with an Emperor’s concern, but with an overriding paternal affection, extending consolation in published edicts and lending help to the full extent of his means.

He chose a board of commissioners by lot to organise aid relief in Campania, and employed the estates of those without heirs, who lost their lives in the eruption, to the reconstruction of destroyed towns.

His only audible comment on the fire in Rome was that he was ruined, and he furnished public buildings and temples with the contents of his villas, and appointed several knights to organise and hasten the repair work.

There was no aid, human or divine which he did not seek to relieve the plague and restrict the spread of epidemic, ensuring the distribution of medicines of every kind, and performing all manner of sacrifice.

Among the evils of the time were the agents and their controllers, who enjoyed long-standing licence. Titus had them whipped with scourges and beaten with sticks, then paraded in the Colosseum arena before being sold at auction or deported to barren islands. To discourage those who thought to engage in similar activities in future, he made it illegal, among other things, for anyone to be tried twice for the same offence on different charges, and limited the time period to a stated number of years during which enquiry could be made into the legal status of any individual.

Book Eight: XXXIV (IX) His Clemency

Having promised that he would accept the office of Pontifex Maximus, in order to keep his hands clean, he kept his word, and thereafter never ordered, or conspired to bring about, any man’s death, though he often had cause for action, swearing that rather than kill he would accept being killed himself.

He was content merely to issue a warning to two patricians with aspirations to power not to attempt anything, declaring that imperial authority was a gift of destiny, and promising them anything else they wished instead. And he sent a messenger in haste to the mother of one of them, she being some distance away, to reassure her of her son’s safety, and not only invited them both to dine along with his friends, but at the next day’s gladiatorial show seated them near to him, and shared his inspection of the contestants’ swords with them. They even say that he examined their horoscopes, and told them that danger threatened, but not from him, and at a later date, which indeed proved the case.

Though his brother, Domitian, plotted against him endlessly, openly urging the legions to rebel, and contemplating fleeing to them for support, Titus neither banished him, nor ordered his execution, but always held him in great honour. Rather he insisted on declaring, from the first day of his reign and thereafter, that Domitian was his colleague and successor, often begging him in private, amidst tears and prayers, to at least show a willingness to return his affection.

Book Eight: XXXV (X) His Last Illness

Death however intervened; bringing as great a loss to mankind as to Titus himself. At the close of the Games, he was gloomy, and wept openly in public, because a victim broke free as he was sacrificing, and because it had thundered from a clear sky. He set out for the Sabine territory but was seized by fever at the first halt, and on his way onwards from there by litter they say he drew back the curtains, gazed at the sky, and complained that life was being undeservedly taken from him, as he had no cause to regret any of his actions, but one. What this was he did not say, nor could anyone guess. Some think he was referring to an act of intimacy with his brother’s wife, Domitia, though she solemnly denied the charge, while if it had been at all true she would no doubt have declared so, and even boasted of it, as she was prone to do with all her misdeeds.

Book Eight: XXXVI (XI) His Death

He died at the same villa as his father, Vespasian, on the 13th of September AD81, at the age of forty-one, after a reign of two years, two months, and twenty days. The people mourned his loss as if he were a member of their own family. The Senators hastened to the House, without being formally summoned, while the doors were still closed, and began rendering thanks for his life, continuing to do so once the doors were opened, praising him even more lavishly after death than they had done while he was present and alive.

Book Eight: Domitian

(Translator’s Note: Suetonius’ chapter numbers are in brackets after mine)

Book Eight: XXXVII (I) Domitian’s Early Life

Domitian was born on the 24th of October AD51, a month before his father Vespasian took up office as consul, in a house in Pomegranate Street, in the sixth district of Rome, which he afterwards converted into the Temple of the Flavians.

He is said to have spent his boyhood and adolescence in scandalous poverty, without a scrap of silverware on the table. And it is well known that Clodius Pollio, an ex-praetor who was attacked in Nero’s satire The One-Eyed Man, used to show a letter in Domitian’s handwriting, in which the future emperor offered him an assignation. There are those too who say that Domitian was seduced by Nerva, his successor.

During the war against Vitellius, he took refuge in the Capitol (69AD) with his paternal uncle Flavius Sabinus and part of that general’s forces. When the enemy forced an entrance and set the shrine alight, he hid all night with the temple-keeper, and at dawn, disguised as a follower of Isis, mingled with the priests of that motley superstition, and crossing the Tiber with a single friend was hidden by the mother of one of his schoolfellows, so effectively that though closely-tracked he remained undiscovered despite a thorough search.

Only after victory was achieved did he appear, and was thereupon hailed as a Caesar, and assumed the office of City praetor with consular powers, though in name only, his colleague conducting all judicial business.

He took advantage of his position to act in a tyrannical manner, so lawlessly indeed that it became clear what his future conduct would be. Suffice it to say, that after seducing many married women, he took to wife Domitia Longina (71AD) though she already had a husband, Aelius Lamia; while his making more than a score of administrative appointments in the City and provinces, in a single day, prompted Vespasian to comment, more than once, that he was surprised he had not named the next emperor along with all the rest.

Book Eight: XXXVIII (II) Public Office and the Succession

He planned a totally unnecessary military campaign in Germany and Gaul, from which his father’s friends managed to dissuade him, solely in order to appear his brother’s equal in rank and power. He was reprimanded for it, and was forced to live with his father to emphasise his youth and unimportance. When his father and brother appeared in public, mounted on their official chairs, he followed behind in a litter, and took part in their Judaean triumph riding the customary white horse. Moreover, of his six consulships, prior to becoming Emperor, he only held one regular one (in 73AD) and then simply because his brother recommended him in place of himself.

He pretended to a remarkably temperate way of life, feigning a particular interest in poetry, an art as alien to him before as it was later despised and rejected by him, and even gave poetry readings in public. Yet when Vologases I, King of the Parthians, asked for one of Vespasian’s sons to lead a force of auxiliaries against the Alani, Domitian tried to make sure that he rather than Titus was appointed, and when the matter came to nothing tried to induce other kings in the East, with bribery and promises, to make similar requests.

When Vespasian died, Domitian considered granting his soldiers twice the bounty offered by his brother Titus, and had no qualms in claiming that his father’s will had been tampered with, since he had been due a half-share of the Empire. From then on, he plotted continually against his brother, openly and in secret. When Titus was gripped by his fatal illness, Domitian ordered him to be left for dead, before he had actually breathed his last. And after Titus’s death he failed to honour him, except to approve his deification, frequently slighting his brother’s memory by using ambiguous phrases in speeches and edicts.

Book Eight: XXXIX (III) His Inconsistency

At the start of his reign, he spent hours alone each day, doing nothing but catch flies and stab them with a razor-sharp pen. Which prompted a show of wit from Vibius Crispus, who when asked if there was anyone with Caesar, replied: ‘no, not even a fly’.

Then he awarded his wife Domitia the title Augusta. He had a son by her in his second consulship (AD73) whom he lost in the second year (AD 82) after becoming Emperor. He divorced her because of her affair with the actor Paris, but could not bear separation and soon took her back, claiming it as the people’s wish that he do so.

He governed inconsistently, displaying a mixture of virtue and vice, but after some time his virtues too gave way to vice, since he seems to have been made avaricious through lack of funds, and cruel through fear, contrary to his natural disposition.

Book Eight: XL (IV) His Public Entertainments

Domitian mounted frequent and extravagant shows in the Colosseum, including a mock sea-fight, as well as in the Circus, where he held not only two and four-horse chariot races, but an infantry and a cavalry battle. He also mounted wild-beast hunts and, at night, torch-lit gladiatorial shows, involving fights between women as well as men.

He always attended the games held by quaestors too, games which had been neglected for some time but which he revived, and granted the people without fail the privilege of calling on two pairs of gladiators from his own troop, whom he would bring out last, clad in their court livery.

During the gladiatorial shows, a little boy with an abnormally small head, dressed in scarlet, stood at his feet. He used to chat with him, sometimes in serious tones, being heard to ask him on one occasion if he knew why he had decided to make Mettius Rufus prefect of Egypt at the last appointment session.

Having dug a pool by the Tiber and ringed it with seating, he mounted frequent naval battles there which were almost full-scale, and which he would watch even during heavy rain.

He founded a quinquennial contest in honour of Jupiter Capitolinus (in 86AD), comprising the triple disciplines of music, riding and gymnastics, awarding far more prizes than nowadays, since there were competitions in Greek and Latin prose declamation as well as poetry; and in addition to competitions in singing to the lyre, there were contests in choral singing, as well as in the unaccompanied instrument; while in the stadium there were even footraces for girls. He presided at the competitions wearing half-boots, and a purple toga in the Greek fashion, a gold crown on his head engraved with images of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva. By his side sat the priests of Jupiter and of the Deified Flavians, similarly dressed, but with crowns bearing his likeness also.

He celebrated the Secular Games, once more (in 88AD), reckoning the correct interval by Augustus’s calculation and not according to the year when Claudius last held them. And in order to have at least a hundred races contested on a single day in the Circus he reduced the number of laps from seven to five.

And he celebrated the Quinquatria in honour of Minerva every year at his Alban villa, and established a college of priests for her, from which men were chosen by lot to hold, and officiate at, wild beast shows and theatrical festivals, and sponsor competitions in rhetoric and poetry.

On three separate occasions he distributed a gift of three gold pieces each to the crowd, and during one annual celebration of the Feast of the Seven Hills he distributed large baskets of food for the Senators and knights, and smaller ones for the commoners, initiating the banquet himself. On the next day he scattered gifts and tokens to be scrambled for, and as most were thrown among the commoners he had five hundred tickets distributed in the sections reserved for the Senatorial and Equestrian orders.

Book Eight: XLI (V) His Public Works

Domitian restored a number of fine buildings which had been destroyed by fire, among them the Capitol which had once more fallen to the flames (in AD80), though he replaced the original dedicatory inscriptions with his own name. In addition he built a new Temple of Jupiter the Guardian (Custos) on the Capitoline Hill, as well as the forum now called the Forum of Nerva, the Flavian Temple, a stadium, a concert hall, and an artificial lake for mock naval-battles. The stone from this latter project was later used to repair the Circus, both flanks of which had been damaged by fire.

Book Eight: XLII (VI) His Campaigns

He undertook a number of campaigns, in one case when unprovoked, in other cases from necessity. That against the Chatti was unjustified (82/83AD). Not so his campaign against the Sarmatians which was provoked by the massacre of a legion along with its commander. He directed two expeditions (86 and 88AD) against the Dacians after they had defeated (84AD) Oppius Sabinus an ex-consul, and then (87AD) Cornelius Fuscus, prefect of the Praetorian Guard, the commander entrusted with the conduct of the war. After several unsatisfactory battles, he celebrated a double triumph (89AD) over the Chatti and Dacians, his victories over the Sarmatians being commemorated merely by the offering of a laurel crown to Capitoline Jupiter.

Lucius Antonius Saturninus, the governor of Upper Germany, began a rebellion (89AD) which was quelled in Domitian’s absence by a remarkable stroke of luck: on the eve of battle, the Rhine thawed, and prevented Antonius’s barbarian allies from crossing the ice to join him. Before the news arrived, Domitian learned of his victory by means of an omen, since on the day of the battle a magnificent eagle embraced his statue at Rome with its wings, screeching triumphantly. Soon afterwards rumours of Antonius’s death were rife, and several people claimed to have seen his head being carried into Rome.

Book Eight: XLIII (VII) His Social Reforms

Domitian was responsible for a number of social reforms: he abolished the grain issue, but restored the custom of holding formal dinners. Two factions were added to the chariot teams in the Circus, gold and purple joining the four previous colours (red, white, blue and green). Actors were allowed to perform privately but not on the public stage. He also prohibited the castration of slaves and controlled the price of eunuchs still owned by dealers.

One year, after a heavy vintage but a poor grain harvest, considering that vines were taking precedence over other crops, he issued an edict forbidding their planting in Italy, and ordering that the provinces reduce their vineyards by half. However he did not carry the measure through.

He opened the most important Court positions, restricted to Senators, to freedmen and knights.

After Saturninus’s rebellion, he banned legions from sharing camps, and any soldier from depositing more than ten gold pieces at headquarters, since the soldier’s savings held in the winter quarters of the two Rhine legions had helped fund the rebellion. He also increased the legionaries’ pay by a quarter, from nine gold pieces a year to twelve.

Book Eight: XLIV (VIII) His Administration of Justice

Domitian was diligent and conscientiousness in his administration of justice, often holding special sittings on the tribunal in the Forum. He rescinded decisions of the Hundred made from self-interest; warned the arbiters not to allow fraudulent requests for the granting of freedoms; and penalized jurors found to have accepted bribes, along with all their co-jurors. He also urged the tribunes of the people to charge a corrupt aedile with extortion, and petition the Senate to appoint a special jury in the case. He was so strict in his control of the city officials and provincial governors that there has never been a greater display of honesty and justice. Since then how many of them have we seen charged with all kinds of offences.

Having undertaken (as Censor) to improve public morals, he put an end to the practice whereby the public occupied seats at the theatre reserved for knights; banned the publication of scurrilous lampoons attacking distinguished people, imposing ignominious punishments on their authors; and expelled an ex-quaestor from the Senate for acting and dancing on the stage.

He stopped prostitutes from using litters, inheriting estates or receiving legacies; erased a knight’s name from the jury list because he had divorced his wife on the grounds of adultery then taken her back again; and condemned men of both orders for breaking the Scantinian law.

He took a severe view of un-chastity among the Vestal Virgins, though it had been condoned even by his father and brother, putting offenders to death, at first in a conventional, but later in the ancient manner. So, he allowed the Oculata sisters, and also Varronilla, to choose the method of their execution (83AD), and exiled their lovers, but later (90AD) sentenced Cornelia, a head of the order, who had been acquitted but after a long interval re-arraigned and found guilty, to be buried alive, while her lovers were beaten to death with rods in the Comitium, except for an ex-praetor who was banished after admitting his guilt while the trial was in progress, though interrogation of the witnesses under torture had proved inconclusive.

And he had a tomb which one of his freedmen had erected for his son, from stones destined for the Temple of Jupiter, to be demolished by his soldiers, and the bones and ashes within thrown into the sea, in order to save the gods from being sacrilegiously insulted with impunity.

Book Eight: XLV (IX) His Initial Moderation

During the early part of his reign, he so abhorred the thought of bloodshed that in his father’s absence from the City he drafted an edict forbidding the sacrifice of bullocks, prompted by his memory of Virgil’s line:

‘Before an impious race feasted on slaughtered oxen.’

Again, in his private life, and even for some time after becoming Emperor, he was considered free of greed and avarice; and indeed often showed proof not only of moderation, but of real generosity. He was liberal with his friends, and always urged them above all to avoid meanness in their actions. He refused bequests from men with children, and even annulled a clause in Rustius Caepio’s will requiring his heir to pay an annual amount to be distributed among newly-appointed Senators.

Domitian quashed suits against debtors to the Public Treasury which had been pending for more than five years, and only allowed renewal within a year, and then only on condition that if the accuser lost his case he must suffer exile. He also pardoned the past offences of quaestors’ secretaries who customarily transacted business forbidden by the Clodian law.

Where parcels of land had been left unoccupied after the distribution of land to veterans, he granted their former owners right of ownership. He also inflicted severe punishments on informants who made false accusations designed, through the confiscation of property, to swell the Privy Purse, and he was quoted as saying: ‘A ruler who fails to punish informers, nurtures them.’

Book Eight: XLVI (X) His Degeneration

His moderation and clemency however were not destined to last, his predilection to cruelty appearing somewhat sooner than his avarice.

He had an adolescent pupil of Paris, the mimic actor, executed, despite the lad being ill at the time, merely because he resembled the actor in appearance and ability. And Hermogenes of Tarsus was put to death because of some unfortunate allusions in his History, while Domitian had the slaves who had transcribed it crucified.

One householder who happened to remark that a Thracian gladiator might be a match for his opponent but not for the patron of the Games, was dragged from his seat and sent out into the arena to be torn to pieces by dogs, with a placard round his neck reading: ‘An impious Thracian.’

Domitian put to death many of the Senate, including several ex-consuls. Three of these, the proconsul of Asia, Civica Cerealis; Salvidienus Orfitus; and the exiled Acilius Glabrio were charged with plotting rebellion, while the rest were executed on the most trivial of charges.

He had Aelius Lamia executed for a few harmless witticisms made long before at his expense. After Domitian had deprived him of his wife, and someone happened to praise his voice, Lamia replied: ‘Abstinence helps!’ and when Titus urged him to marry again, he quipped; ‘What, are you looking for a wife too?’

Domitian disposed of Salvius Cocceianus, because he celebrated his paternal uncle Otho’s birthday; and Mettius Pompusianus because his birth was accompanied by portents of imperial power, because he always carried a map of the world with him, drawn on parchment, along with speeches of kings and generals taken from Livy, and because he named two of his slaves Mago and Hannibal.

Sallustius Lucullus, the Governor of Britain, was executed for allowing a new type of lance to be named ‘Lucullan’ after him.

Junius Rusticus died because he published eulogies of Thrasea Paetus and Helvidius Priscus, praising them for their great virtues, while Domitian used the occasion to banish the philosophers from the City and all Italy.

The younger Helvidius Priscus was also done away with, on the pretext that the characters of the faithless Paris and his lover Oenone, played on stage in a farce of his composition, could be interpreted as a criticism of Domitian’s divorce.

And Domitian executed one of his cousins, Flavius Sabinus, too, because a herald inadvertently proclaimed him Imperator on the day of the consular elections, instead of consul.

It is noticeable that Domitian displayed greater cruelty after crushing the rebellion of Saturninus, inventing a new form of inquisition, toasting the genitals and severing the hands of his prisoners to discover the whereabouts of rebels in hiding. Only two leaders of the revolt were pardoned, a tribune of senatorial rank and a centurion, who boasted that their flagrant immorality meant they could not have influenced their commander or the troops.

Book Eight: XLVII (XI) His Cruelty

Domitian was not only excessive, but also cunning and sudden in his savagery. The day before crucifying him, he summoned one of his stewards to his bedchamber, made him sit with him on a couch, dismissed him in a secure and happy frame of mind, and even deigned to send him a portion of his dinner!

On the verge of having the ex-consul Arrecinus Clemens, his friend and agent, arraigned, Domitian treated him with as much or more favour as previously, and then, catching sight of the man’s accuser, as they drove out together, he turned to Arrecinus and asked: ‘Shall we listen to that worthless slave tomorrow?’

The abuse he inflicted on his victims’ patience was all the more offensive because he always prefaced his most vicious punishments with a speech of clemency, until the most certain sign of a cruel end was the leniency of the preamble. Having brought a group of men to the Senate to answer a charge of treason, he introduced the matter by declaring that it would prove a test that day of how much the House cared for him, and so he had no trouble ensuring the accused were condemned to death by flogging, in the ancient manner. Then, as if appalled at the cruelty of the penalty, he exercised his veto, to lessen the odium that might follow, and said, his exact words being of interest: ‘Fathers of the Senate, if you love me, grant me a favour, which I know it will be difficult for you to countenance, and allow the condemned to choose, freely, the manner of their own deaths; thus you will spare your own feelings, while all must perceive that I was present at this meeting.’

Book Eight: XLVIII (XII) His Avarice

His resources having been exhausted by the cost of his building programme, his entertainments, and the army’s pay rise, he tried to reduce his military expenses by reducing troop numbers, then realising the exposure to barbarian incursions implied, yet still pressed to ease his financial difficulties, he barely hesitated before resorting to all manner of theft. Throughout the empire the estates of the living as well as the dead were seized on any pretext and any informant’s word. It was sufficient to claim some action or word on the part of the accused against the Emperor’s dignity. A single declaration that a deceased individual during his lifetime had dubbed Caesar his heir was enough to guarantee confiscation of their estate, even of those with no known connection to him.

In addition to other taxes, that on the Jews was pursued with the greatest rigour, and those who lived as Jews but did not acknowledge their faith in public, as well as those who tried to hide the facts of their birth, were prosecuted if they failed to pay the tribute levied on their people. I remember in my youth being present as a ninety-year old man was examined, in front of the procurator and a densely packed courtroom, to prove whether he had been circumcised.

Book Eight: XLIX (XIII) His Arrogance and Presumption

From his earliest youth Domitian lacked affability. On the contrary, he was discourteous and highly presumptuous in word and action. When Caenis, his father’s mistress, returned from Istria, and offered him her cheek to kiss as usual, he merely extended his hand. And vexed that the attendants on his brother Titus’s son-in-law, Flavius Sabinus, were dressed in white like his own, he quoted Homer’s line:

‘…a host of leaders is no wise thing.’

On becoming Emperor, he had no qualms about boasting in the Senate that it was he who had conferred power on his father Vespasian, and his brother Titus, and that they had now simply returned to him what was his. Nor about claiming, after taking back his wife following their divorce, that he had ‘recalled her to his sacred couch.’

On his feast day, Domitian adored hearing the Colosseum crowd shout: ‘Long live our Lord and Lady.’ And during the Capitoline competition, when there was a unanimous call for the reinstatement of Palfurius Sura, winner of the prize for oratory, who had been expelled from the Senate some time previously, Domitian would not deign to reply, and sent a crier to tell them to be silent.

No less arrogance is evident in the opening of his circular issued in the name of his procurators: ‘Our Lord, our God, orders this done.’ It was customary thereafter to address him in this way in speech or writing.

Statues set up in his honour in the Capitol had to be of a given weight of gold or silver, and he erected so many vast arcades and arches, decorated with chariots and triumphal emblems, all over the City, that someone scribbled the word arci (arches) on one of them but in Greek characters, so that it read, in that language: ‘Enough!’

Domitian held the consulship seventeen times (in AD71, 73, 75-77, 79-80, 82-88, 90, 92, and 95) setting a new precedent. A group of seven consulships were in successive years, but all were in name only, and he held few beyond the 13th of January and none beyond the 1st of May.

Having adopted the surname Germanicus after his two triumphs, Domitian renamed September and October, the months of his accession and birth respectively, after himself; calling them ‘Germanicus’ and ‘Domitianus’,

Book Eight: L (XIV) Hated and Afraid

In this way he became an object of terror to all, and so hated that he was finally brought down by a conspiracy of his companions and favourite freedmen, which also involved his wife, Domitia Longina.

He had been advised long ago of the year, and even the day and hour and manner, of his death. The astrologers had predicted it all in his childhood, and his father once mocked him when he refused a dish of mushrooms at dinner, saying that he would do better given his destiny to beware of swords. As a result he was always nervous and anxious, and troubled inordinately by the slightest of suspicions. Nothing had more effect in preventing him enforcing his edict restricting the number of vineyards, than these lines that went the rounds:

‘Goat, gnaw at my root! But when you stand at the altar

There’ll be juice enough yet, to sprinkle over you.’

Because of this same anxiety, though he was always eager for honours, he chose to refuse a new one devised by the Senate when it was offered him, which would have decreed that, whenever he held the consulship, a group of knights chosen by lot, wearing the purple-striped robe (trabea) and carrying lances, should join the lictors and attendants preceding him as he walked,

As the critical moment predicted drew near, he grew daily more anxious, even having the walls of the galleries where he walked faced with translucent stone so that he could see in their highly-polished surfaces whatever was going on behind his back. Nor did he grant a hearing to prisoners except alone in private and with their chains grasped tight in his hands.

And he made an example of Epaphroditus, his confidential secretary, in order to make it plain to his household that killing a master was never justified, condemning the freedman to death on the grounds that he had helped Nero kill himself when the rest had deserted him.

Book Eight: LI (XV) Premonitions of Death

The specific action that finally hastened his own destruction, was the execution of his own second cousin Flavius Clemens, just before the end of a consulship, suddenly and on the slightest of suspicions, though Flavius was known as a ridiculously indolent individual, and even though Domitian had publicly named Flavius’s small sons as his heirs, and made them adopt the names Vespasian and Domitian.

So many lightning-storms had occurred and been reported to him over a period of eight months that he at last cried out: ‘Well, let him strike whom he wishes!’ The Temple of Capitoline Jupiter, the Flavian Temple, the Palace and even the emperor’s own bedroom were struck, and a violent storm tore the inscription plate from the base of a triumphal statue of his, and hurled it into the interior of a neighbouring tomb.

That tree which had blown down, and then revived, while Vespasian was still a private citizen, was toppled once more. And though, throughout his reign, he had always received the identical favourable response from the Goddess of Fortune at Praeneste (Palestrina) when he commended the following year to her care, she now returned him a dire one, prophesying bloodshed.

Then he dreamed that Minerva, whom he worshipped with a superstitious reverence, emerged from her shrine to say that she could no longer protect him since Jupiter had disarmed her.

Yet he felt most threatened by the astrologer Ascletarion’s prediction, and its sequel. When brought before the Emperor, Ascletarion did not deny having spoken of events, which he had foreseen by his art. Asked what his own fate would be, he replied that he would shortly be eaten by dogs. Domitian had him executed at once, and to prove the astrologer’s fallibility, ordered the body to be cremated with the greatest of care. But during the funeral, a sudden violent storm toppled the pyre, and the partly-burnt corpse was mangled by dogs. Latinus the comic mime who was passing by saw it all, and frightened Domitian by relating the details at dinner, along with all the rest of the day’s gossip.

Book Eight: LII (XVI) The Eve of Assassination

On the eve of his assassination, he was offered some apples, but asked for them to be served the following day, adding: ‘If only I am there to eat them.’ Then, turning to his companions, he said that next evening a Moon of blood would rise in Aquarius, after an event that men would speak of throughout the world.

At midnight he was so terrified he leapt from his bed, and at dawn tried and then condemned a soothsayer from Germany who had interpreted the successive storms and bursts of lightning as presaging a change of rulers. While vigorously scratching a wart on his forehead he drew blood and commented: ‘Let this be all.’ Presently he asked the time and, as they had pre-arranged, his freedmen lied that it was the sixth hour and not the fifth which he feared. Thinking the danger past, Domitian went joyfully to his bath, only to change his mind when his head valet Parthenius announced that he had an urgent visitor on some vital matter that could not be deferred. Dismissing his attendants Domitian went instead to his bedroom, where death found him.

Book Eight: LIII (XVII) His Death

Regarding the nature of the plot, and his death, the following is all that is known. When the conspirators met to decide when to attack him, and whether it should be while he was bathing or dining, Stephanus, his niece Domitilla’s steward, who had been accused of embezzlement, offered them advice and help.

To divert suspicion he feigned an injury to his left arm and, for some days, went round with it wrapped in woollen bandages. Then, concealing a dagger inside the bandages, and demanding an audience in order to give news of a conspiracy, he handed Domitian a paper to read, and while the Emperor stood there shocked by its contents, stabbed him in the groin.

As Domitian tried to resist, he received seven more wounds dealt by Clodianus a subaltern, Maximus a freedman of Parthenius, Satur a head-chamberlain, and by a gladiator from the Imperial school. A boy who was attending to the shrine of the Household Gods, in the bedroom, and witnessed the assassination, gave further details. Domitian, after the first blow, called to him to bring the dagger under his pillow, and summon the servants, but the boy found only a hilt with no blade, and the doors were locked. Meanwhile Domitian had grappled Stephanus to the floor, where they continued to struggle, Domitian trying to wrest the dagger from his assailant, or to gouge his eyes out with lacerated fingers.

He died at the age of forty-four, on the 18th of September AD96, in the fifteenth year of his reign. His body was placed on a common bier by the public undertakers, as if he were a pauper, and taken to his nurse Phyllis’s suburban villa on the Via Latina where she cremated the corpse. His ashes she secretly carried to the Flavian Temple and there mingled them with those of his niece Julia, Titus’s daughter whom she had also nurtured.

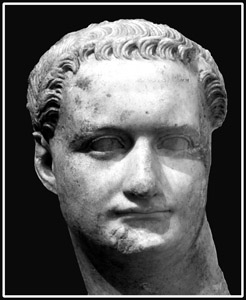

Book Eight: LIV (XVIII) His Appearance

Domitian was tall, and of a ruddy complexion, with large rather weak eyes, and a modest expression. He was handsome and attractive when young, his whole body well-made except for his feet with their short toes. Later, he lost his hair, and developed a protruding belly, while his legs became thin and spindly after a long illness.