Suetonius: The Twelve Caesars

Book III: Tiberius

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2010 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book Three: Tiberius

- Book Three: I The Claudii

- Book Three: II Good and Bad

- Book Three: III The Livii

- Book Three: IV His Father

- Book Three: V Birth

- Book Three: VI Childhood and Boyhood

- Book Three: VII Marriage and Family Matters

- Book Three: VIII His Civil Career

- Book Three: IX His Military and Official Appointments

- Book Three: X Withdrawal from Rome

- Book Three: XI Retirement at Rhodes

- Book Three: XII Under Suspicion

- Book Three: XIII Recall to Rome

- Book Three: XIV Omens of Destiny

- Book Three: XV Adoption by Augustus

- Book Three: XVI Campaigning in Illyricum

- Book Three: XVII Recognition in Rome

- Book Three: XVIII Return to Germany

- Book Three: XIX Discipline and Caution

- Book Three: XX Triumphant Return to Rome

- Book Three: XXI The Succession

- Book Three: XXII The Death of Postumus

- Book Three: XXIII The Reading of Augustus’ Will

- Book Three: XXIV His Accession

- Book Three: XXV Mutiny and Conspiracy

- Book Three: XXVI His Political Discretion

- Book Three: XXVII His Dislike of Flattery

- Book Three: XXVIII His Support of Free Speech

- Book Three: XXIX His Courtesy

- Book Three: XXX His Support of the Senate

- Book Three: XXXI His Support of the Consuls and the Rule of Law

- Book Three: XXXII His Modesty and Respect for Tradition

- Book Three: XXXIII His Regulation of Abuses

- Book Three: XXXIV His Cost and Price Controls

- Book Three: XXXV His Strictures Regarding Marriage and Rank

- Book Three: XXXVI The Banning of Foreign Rites and Superstitions

- Book Three: XXXVII His Suppression of Lawlessness

- Book Three: XXXVIII His Dislike of Travel

- Book Three: XXXIX His Withdrawal to Campania

- Book Three: XL His Crossing to Capreae

- Book Three: XLI His Final Retirement to Capreae

- Book Three: XLII His Moral Decline

- Book Three: XLIII His Licentiousness on Capri

- Book Three: XLIV His Gross Depravities

- Book Three: XLV His Abuse of Women

- Book Three: XLVI His Frugality

- Book Three: XLVII His Lack of Public Generosity

- Book Three: XLVIII Rare Exceptions

- Book Three: XLIX His Rapacity

- Book Three: L His Hatred of his Kin

- Book Three: LI His Later Enmity Towards Livia

- Book Three: LII His Lack of Affection for Drusus the Younger and Germanicus

- Book Three: LIII His Treatment of Agrippina the Elder

- Book Three: LIV His Treatment of His Grandsons Nero and Drusus

- Book Three: LV His Treatment of His Advisors

- Book Three: LVI His Treatment of His Greek Companions

- Book Three: LVII His Inherent Cruelty

- Book Three: LVIII His Abuse of Lese-Majesty

- Book Three: LIX Satires Directed Against Him

- Book Three: LX His Cruelty on Capreae

- Book Three: LXI The Increasing Cruelty of His Reign

- Book Three: LXII The Effects of Drusus the Younger’s Death

- Book Three: LXIII His Insecurity

- Book Three: LXIV His Treatment of Agrippina and Her Sons

- Book Three: LXV The Downfall of Sejanus

- Book Three: LXVI Public Criticism

- Book Three: LXVII His Ultimate Self-Disgust

- Book Three: LXVIII His Appearance and Mannerisms

- Book Three: LXIX His Fear of Thunder

- Book Three: LXX His Literary Interests

- Book Three: LXXI His Use of Latin for Public Business

- Book Three: LXXII His Two Attempts to Re-Visit Rome

- Book Three: LXXIII His Death

- Book Three: LXXIV Portents of his Death

- Book Three: LXXV Public Response to his Death

- Book Three: LXXVI His Will

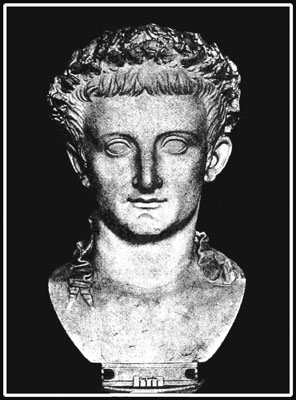

Book Three: Tiberius

Book Three: I The Claudii

The patrician branch of the Claudians – there being a plebeian branch too, no less influential and distinguished – was originally from Regillum, a Sabine town. The family moved to Rome, with a large throng of dependants, either shortly after the foundation of the city (in 753BC), at the instigation of Titus Tatius, who ruled jointly with Romulus or, as is more generally accepted, at the instigation of the head of the family, Atta Claudius, about six years after the expulsion of the kings (in 504BC).

The Claudians were enrolled among the patricians, and granted land by the State, on the far side of the Anio, for their dependants, and a family burial-ground at the foot of the Capitoline. In the course of time they were honoured with twenty-eight consulships, five dictatorships, seven censorships, six triumphs and two ovations.

The family bore various forenames and surnames, though they agreed to drop the forename Lucius, after one Lucius Claudius was convicted of highway robbery, and a second of murder. However they added the surname Nero, meaning ‘strong and vigorous’ in the Sabine tongue.

Book Three: II Good and Bad

Many of the Claudians did the State great service, though many others were guilty of committing great crimes.

To quote a few examples of the former; Appius Claudius Caecus, ‘the Blind’, warned against any alliance with King Pyrrhus (in 280BC); while Appius Claudius Caudex, was first to sail a fleet across the Straits of Messina, and subsequently drove the Cathaginians from Sicily (240BC); and Claudius Tiberius Nero crushed Hasdrubal, who had brought an army from Spain, preventing him from reinforcing that of his brother Hannibal (207BC).

An example of the latter, however, is Claudius Crassus Regillensis, one of the Decemvirs appointed to codify the laws, whose wicked attempt to enslave a freeborn girl, for whom he lusted, caused the second secession of the plebeians from the patricians (in 449BC). Then there was Claudius Russus, who erected a statue (c268BC) of himself in the town of Forum Appii, with a crown on its head, and tried with an army of dependants to gain possession of Italy. And Claudius Pulcher, too, who on taking the auspices before a naval battle off Sicily (Drepana, in 249BC), and finding the sacred chickens refused to feed, defied the omen and threw them into the sea, crying: ‘Let them drink, if they won’t eat!’ He was subsequently defeated. When recalled, and asked by the Senate to appoint a dictator, he nominated Glycias his messenger, as if in mockery of the country’s dire situation.

The Claudian women too have equally diverse records. There was the famous Claudia Quinta who (c204BC) re-floated the boat carrying the sacred image of the Idaean Mother-Goddess, Cybele, hauling it from the shoal in the Tiber where it was stranded. She had prayed for the goddess to grant success, as proof of her perfect chastity. But there was also the notorious Claudia who, in a case without precedent since it involved a woman, was tried for treason by the people (in 246BC). Angered by the slow progress of her carriage through a crowd, she expressed the wish that her brother Claudius Pulcher were still alive, to lose another fleet, and thin the population of Rome.

All the Claudii were aristocrats, and notoriously upheld the power and influence of the patrician party, with the sole exception of Publius Clodius, who became the adoptive son of a plebeian younger than himself, in order to oppose Cicero and drive him from the City (in 59BC). The Claudians were so wilful and stubborn in their attitude towards the commons that they refused to dress as suppliants or beg for mercy even when on trial for their lives; and in their constant disputes and quarrels with the tribunes even dared to strike them.

There was even the occasion when a Claudian celebrated a triumph (Appius Claudius Pulcher, in 143BC) without first seeking the people’s permission, and his sister, a Vestal Virgin, clambered into his chariot and rode with him all the way to the Capitol, making it an act of sacrilege for the tribunes to exercise their veto and halt the procession.

Book Three: III The Livii

Such were the roots of Tiberius Caesar, who was of Claudian descent on both sides, on his father’s from Claudius Tiberius Nero, and on his mother’s from Publius Claudius Pulcher, both being sons of Appius Claudius Caecus.

Tiberius was also a member of the Livii, into whose family his maternal grandfather (Livius Drusus) had been adopted. The Livians were of plebeian origin, but so prominent as to have been honoured with eight consulships, two censorships, and three triumphs, as well as the offices of dictator and master of the horse. The family was particularly famous for four of its most distinguished members, Marcus Livius Salinator, Livius Drusus, Marcus Livius Drusus the Elder, and his son of the same name.

Livius Salinator was convicted of malpractice while consul, and fined, yet he was nevertheless re-elected consul by the commons for a second time and appointed censor (in 204BC) whereupon he placed a note (nota censoria) against the name of every tribe on the electoral roll, to register their vagaries.

The Livius Drusus who first gained the hereditary surname, did so by killing an enemy chieftain, Drausus, in single combat (c283BC). It is said that when propraetor of Gaul, he brought back the amount in gold paid to the Senones as a ransom to lift their siege of Rome (a century earlier c390BC), which had not in fact, as tradition claimed, been wrested back from them by the dictator Camillus.

Livius Drusus’ great-great-grandson, Marcus Livius Drusus the Elder, known as ‘The Patron of the Senate’ for his stubborn opposition (in 122BC) to the Gracchi brothers and their reforms, left a son, Marcus Livius Drusus the Younger, who was treacherously assassinated by the opposing party while actively pursuing comprehensive plans at a time of like dissent (91BC).

Book Three: IV His Father

Tiberius’ father, Nero, commanded Julius Caesar’s fleet (48BC), as quaestor, during the Alexandrian War and contributed significantly to his eventual victory. For this he was made a priest in place of Publius Scipio, and sent to establish colonies in Gaul, including those of Narbo (Narbonne) and Arelate (Arles).

Nevertheless, after Caesar’s murder, when the Senate, in order to prevent further violence, voted for an amnesty for the tyrannicides, Tiberius Nero went much further and supported a proposal that they be rewarded. Later a dispute arose between the triumvirs Antony and Lepidus, just as his term as praetor (42BC) was ending, leading him to retain his badge of office beyond the appointed time, and follow Antony’s brother, Lucius Antonius, who was then consul, to Perusia (Perugia, in 41BC). When the town fell and others capitulated, he stood by his allegiances, and escaped to Praeneste (Palestrina), and then Naples.

After failing to raise an army of slaves, by promising them freedom, he took refuge in Sicily. Offended however at not being given an immediate audience with Sextus Pompeius, and at being denied the use of the fasces (his emblems of office), he crossed to Greece and joined Mark Antony, and when peace was concluded, returned with him to Rome (in 40BC). There (in 39BC), he surrendered his wife Livia Drusilla, who had borne him a son, and was pregnant with another, to Augustus, at his request. On his death (in 33BC), he was survived by his sons, Tiberius, and Drusus the Elder.

Book Three: V Birth

It has been conjectured that Tiberius was born at Fundi (Fondi), but with no better evidence than that his maternal grandmother, Aufidia, was a native of the place, and that a statue of Good Fortune was later erected there by Senate decree. The vast majority of reliable sources place his birth in Rome, on the Palatine, on the 16th of November 42BC, in the consulships of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who had been consul previously in 46BC, and Lucius Munatius Plancus; and during the Civil War that ended at Philippi.

So both the calendar and the official gazette state, but some still insist that he was born in the preceding year, in the consulships of Hirtius and Pansa, and others that he was born in the following year, in the consulships of Servilius Isauricus and Lucius Antonius.

Book Three: VI Childhood and Boyhood

In his childhood and boyhood he experienced hardship and difficulty, his parents (Nero and Livia) taking him everywhere with them, as they fled (from Augustus). At Naples, as the enemy burst into the city, they secretly took ship (in 40BC), and the infant all but gave them away twice by his crying, as their companions in danger snatched him from his nurse’s breast and then Livia’s arms, in their effort to share the burden.

They sailed to Sicily and then Greece, where he was entrusted to the public care of the Spartans, dependants of the Claudii, but when Livia fled Sparta too, at night, he almost died when they were encircled by a forest fire, in which her robe and hair were scorched.

The presents that Pompeia Magna, Sextus Pompey’s sister, gave him in Sicily, namely a cloak, a brooch, and some gold charms, were preserved and are exhibited at Baiae.

On his parents return to Rome (in 40BC), he was adopted as heir according to the will of a Senator, Marcus Gallius. Though accepting the inheritance, he later gave up the adopted name, since Gallius had been of the opposite party to Augustus.

At the age of nine (in 32BC), Tiberius delivered the eulogy from the rostra at his father’s funeral, while three years later (in 29BC) he took part in Augustus’ (triple) triumph after Actium, riding the left trace-horse of the triumphal chariot, while Marcellus, Octavia the Younger’s son, rode the right. He presided at the City festival as well, and led the cavalry troop of older boys in the Troy Game at the Circus.

Book Three: VII Marriage and Family Matters

The principal domestic events between his coming of age and his accession to power are these. On separate occasions he honoured the memory of his father, Tiberius Nero, and his maternal grandfather, Livius Drusus, with a gladiatorial show, the first being given in the Forum and the second in the amphitheatre, persuading retired gladiators to appear by a payment per head of a thousand gold pieces. He also gave, but did not attend, theatrical performances. His mother, Livia, and stepfather, Augustus, funded this lavish expenditure.

Tiberius first married (after 19BC) Vipsania Agrippina, the daughter of Agrippa, and granddaughter of Caecilius Atticus, the Roman knight to whom Cicero addressed many of his letters. Though she was a congenial partner, and had borne him a son, Drusus (the Younger, in 13BC), he hurriedly divorced her (in 11BC), despite her being again pregnant, to marry Julia the Elder, Augustus’ daughter. He was greatly distressed, being happy in his marriage to Agrippina, and disapproving of Julia’s character, having recognised, as many others did, her illicit passion for him while her former husband (and his own father-in-law), Agrippa, was still alive. Even after the divorce, he bitterly regretted separating from Agrippina, and on the one occasion he saw her again, he gazed after her so intently, and tearfully, that care was taken to prevent him ever seeing her again.

At first, he lived amicably enough with Julia, and returned her love, but he soon grew distant, and eventually, after the severing of the tie between them formed briefly by a child who died in infancy (10BC) at Aquileia, he ceased to sleep with her.

His brother Drusus the Elder, died in Germany (in 9BC), and Tiberius brought the body back to Rome, walking before it the whole way.

Book Three: VIII His Civil Career

His civil career began with his advocacy, in separate cases with Augustus presiding, on behalf of King Archelaus (of Cappadocia); the citizens of Tralles (Aydin, in Turkey); and the Thessalians.

He also appeared before the Senate to support pleas by the inhabitants of Laodicea, Thyatira and Chios, who requested help after a devastating earthquake on the coast of Asia Minor.

When Fannius Caepio conspired with Varro Murena against Augustus, it was Tiberius who arraigned him on charges of high treason, and secured his condemnation (in 23BC).

Meanwhile he had undertaken two special commissions; a re-organisation of the defective grain supply, and an investigation into the slave-farms, in Italy, whose owners had acquired an evil reputation by confining lawful travellers, and also harbouring men who hid there as slaves, out of an aversion to military service.

Book Three: IX His Military and Official Appointments

His first campaign was as military tribune, against the Cantabrians (in 25BC). He then led an army to Asia Minor and restored Tigranes III to the throne of Armenia (in 20BC), personally investing him as king on the official dais; and also recovered the standards lost to the Parthians by Marcus Crassus.

He became Governor of Transalpine Gaul (Gallia Comata) a few years later (in 16BC) and held the post for a year or so, quelling unrest due to barbarian incursions and feuding between the Gallic chieftains.

Later he subdued the Raeti and Vindelici in the Alps (15BC), the Breuci (12BC) and Dalmatians (11-9BC), in Pannonia, and finally captured forty thousand prisoners of war in Germany (8BC) and re-settled them along the Gallic banks of the Rhine. He was rewarded for these exploits by an ovation (9BC) in Rome, followed by a regular triumph (in 7BC), having previously had the triumphal regalia conferred on him, as a new form of honour.

He held the offices, in turn, of quaestor (23BC), praetor (16BC), and consul (13BC), before the minimum ages normally required, and with scant regard to the prescribed intervals. Later he was again consul (in 6BC), at the same time holding the powers of a tribune for five years.

Book Three: X Withdrawal from Rome

Yet, with fortune at the flood, while in the prime of life, and in excellent health, he suddenly decided (in 6BC) to retire, and remove himself as far as possible, from the centre of affairs. Perhaps the motive was his loathing for Julia, his wife, whom he dare neither bring charges against nor divorce, though he could no longer tolerate her presence; or perhaps, to prevent familiarity breeding contempt among the populace, he sought by his absence to maintain or even enhance his prestige, against the moment when his country might need him.

Some speculate that when Gaius and Lucius, Augustus’ grandchildren and adopted sons, were both of age, he chose to relinquish his role, and the long-term position he had virtually assumed of second-in-command of the Empire, in much the same way as Marcus Agrippa had. Agrippa retired to Mytilene (in 23BC), when Marcellus began his official career, so as not to overshadow him or diminish him by his presence. And such was indeed the reason Tiberius later gave.

At the time, he simply asked for leave of absence, on the grounds that he was wearied by office and needed to rest. He refused to be swayed by Livia’s urgent entreaties to stay, or Augustus’ open complaint to the Senate that Tiberius was deserting him. On the contrary, when they tried their utmost to detain him, he responded by refusing food for four days.

With freedom to depart at last granted, he set out immediately for Ostia, leaving his wife, Julia, and his son (by Agrippina), Drusus the Younger, behind in Rome, granting the odd kiss as he left but barely saying a word to those who saw him off.

Book Three: XI Retirement at Rhodes

As he sailed south from Ostia, along the Campanian coast, news arrived that Augustus was ill, and he anchored for a while. But as rumours spread that Tiberius was delaying in hope of realising a desire for supreme power, he sailed on to Rhodes, regardless of the opposing winds. He had fond memories of that beautiful and salubrious island after touching there on his return voyage from Armenia.

Once there, and established in a modest house, and with an equally humble suburban villa, he was content to live in an unassuming manner, often strolling about the gymnasium unaccompanied by lictors or messengers, and trading pleasantries with the Greeks, almost as if they were peers of his.

It chanced on one occasion that, while agreeing his program that morning for the day ahead, he expressed a wish to visit all those in the city suffering from illness. Through a misunderstanding on the part of his staff, orders went out to bring all patients to a public colonnade, where they were grouped according to their ailments. Startled by encountering them, Tiberius was somewhat at a loss, but ended by apologising individually, even to the humblest and least significant, for the inconvenience he had caused.

He only exercised his rights as a tribune publicly once. He used to frequent the philosophy schools and the halls where the professors lectured, and one day when a fierce dispute had arisen among rival sophists, one daring fellow abused him roundly for interfering and taking sides. Tiberius retreated calmly to his house, then suddenly re-appeared with his lictors, and ordered a herald to bring the slanderer before his tribunal, before having him consigned to jail.

Not long afterwards, he learned of his wife Julia’s banishment (in 2BC) for adultery and immoral behaviour, and that a bill of divorce had been issued in his name, on Augustus’ authority. Welcome as the news was, he thought it his duty to attempt, in a stream of letters, to try and effect reconciliation between father and daughter. He also asked that, whatever punishment she merited, she be allowed to keep any gifts he himself may have made her.

When the term of his powers as tribune ended, he asked permission to visit his family in Rome, whom he greatly missed, maintaining that the sole reason for his withdrawal from the City had been to avoid any suspicion of rivalry with Gaius and Lucius, and that since they were now adults and had undisputed right of succession, his reason was no longer valid. Augustus however rejected his plea, and he was advised to relinquish all thought of visiting the family he had so readily abandoned.

Book Three: XII Under Suspicion

He therefore remained, unwillingly, in Rhodes; securing grudging permission, thanks to Livia’s help, that while absent from Rome he could assume the title of ambassador for Augustus, so as to mask his ignominy.

Indeed he now lived a life that was not merely private, but shadowed by danger and fear, deep in the countryside and far from the sea, seeking to avoid the attention of travellers touching at the island, though that was difficult since generals and magistrates on the way to their provinces broke their journey at Rhodes as a matter of routine.

Moreover he had even greater reason for anxiety on finding his stepson Gaius Caesar, Governor of the East, whom he visited on Samos (c1BC), somewhat cool towards him, due to slanders spread by Marcus Lollius, who was attached to Gaius’ staff as his guardian.

Also, some centurions Tiberius had appointed, on their return to camp from leave, were said to have sent questionable messages to various people, which seemed designed to foment rebellion. Augustus informed him of these claims, prompting Tiberius to demand the presence on Rhodes of someone else of rank who could quell any suspicions regarding his words or actions.

Book Three: XIII Recall to Rome

Tiberius gave up all his usual forms of exercise, on horseback or with weapons, and abandoned Roman dress for Greek cloak and slippers. This was his mode of life for two years or so, during which he grew daily more despised and shunned, to the point where the citizens of Nemausus (Nîmes, in his former province in Gaul, Gallia Comata) toppled his statues and busts.

Once, at a private dinner party attended by Gaius Caesar, a guest rose to his feet when Tiberius’s name was mentioned, and offered to sail for Rhodes, if Gaius would only say the word, and bring back the head of ‘the Exile’ as he was commonly designated. This incident, specifically, which rendered his position not merely disquieting but downright perilous, drove Tiberius to plead urgently for his recall to Rome, a prayer in which Livia joined, and partly due to circumstances, he obtained his request. Augustus had resolved to leave the final decision to his elder son, and Gaius now chanced to be on bad terms with Marcus Lollius, and much more sympathetic towards Augustus’ entreaty. With Gaius’ consent, Tiberius was recalled, on the strict understanding that he would maintain no further interest or involvement in politics.

Book Three: XIV Omens of Destiny

So, eight years after his withdrawal from Rome, he returned (2AD), still with a strong and unshaken belief in his own destiny, which the omens and prophecies of his childhood had fostered. For instance, Livia, while pregnant with him, had tried to predict the sex of her child, by taking an egg from a brood hen, which she and her women then warmed in their hands till it hatched, when a male with a fine comb emerged.

In his infancy, Scribonius, the astrologer, prophesied an illustrious career for him, and that he would be the king of Rome yet wear no crown; and this when the reign of the Emperors had not yet begun.

Again, in his first command, as he led his troops through Macedonia (in 20BC) on his way to Syria, the altars at Philippi consecrated decades ago by the victors (in the year of his birth, 42BC) burst spontaneously into flame.

Later, on his way to Illyricum he visited the oracle of Geryon near Patavium (Padua), and drew a lot which advised him to throw golden dice into the fountain of Aponus, if he wanted his questions answered. He made the highest possible cast, and the dice can still be seen beneath the surface.

A few days before he was notified of his recall from Rhodes, an eagle of a species not seen before on the island, perched on the roof of his house; and on the very eve of notification, the tunic he was donning seemed to glow. His change of fortune convinced Tiberius that Thrasyllus, the astrologer, attached to his household as a man of learning, did indeed have genuine powers. They had been strolling together on the headland, when Tiberius, thinking all the man’s claims false, his predictions being contradicted by the adverse nature of events; and anxious at having rashly confided secrets to him; suddenly resolved to push him from the cliff. At that very instant Thrasyllus, seeing a ship, cried out that it brought good news.

Book Three: XV Adoption by Augustus

Having introduced his son Drusus the Younger to public life, Tiberius, after his recall to Rome, changed his residence on the Esquiline Hill, moving from the house of the Pompeys on the Carinae (the ‘Keel’ on its south-western slopes) to one in the Gardens of Maecenas. There he led a retired life, carrying out no public functions, but simply attending to his personal affairs.

Within three years, however, both Lucius Caesar and Gaius Caesar were dead (in AD2 and 4 respectively), and Augustus now adopted both their brother Agrippa Postumus, and Tiberius, who was first required to adopt his nephew Germanicus (in 4AD).

Tiberius ceased to act as head of the Claudians, and surrendered all the privileges of that position, making no gifts and freeing no slaves, and only accepting gifts or legacies as an addition to the personal property he held (which was technically owned by Augustus).

From that moment onwards, Augustus did all he could to enhance Tiberius’ prestige, especially after the disowning and banishment of Postumus (c6AD) made it obvious that Tiberius was the sole heir to the succession.

Book Three: XVI Campaigning in Illyricum

Tiberius was granted another three years of the powers a military tribune wielded, with the task of pacifying Germany (AD4-6), and the Parthian envoys, who presented themselves to Augustus in Rome, were commanded to appear before Tiberius in that province.

However, on the news of rebellion in Illyricum, he was transferred there to command the campaign, fighting the most damaging war since those with Carthage. He had control of fifteen legions and an equivalent force of auxiliaries for three years (AD7-9), in arduous conditions, and with grossly inadequate supplies. But though he was frequently summoned to Rome, he never allowed the massed enemy forces to push back the Roman lines, and take the offensive.

As just reward for his perseverance, he conquered the whole of Illyricum, a stretch of country bounded by Italy, Noricum (Austria/Slovenia), the Danube, Macedonia, Thrace and the Adriatic, and reduced the tribes there to complete submission.

Book Three: XVII Recognition in Rome

His exploits garnered greater glory from circumstance, since the loss of Quinctilius Varus and his three legions in Germany (in 9AD), would have allowed the victorious Germans to have made common cause with the Pannonians, if Illyricum had not already submitted.

In consequence he was voted a triumph and other distinctions. Some proposed he be granted the name ‘Pannonicus’, others favoured ‘Invictus’ (Unconquered) or ‘Pius’ (Devoted), which Augustus vetoed, however, repeating his promise that Tiberius would be content with the name he would receive at Augustus’ death.

Tiberius postponed the triumph, himself, given the public mourning over Varus’s disaster. Nevertheless he made his entry to the City wreathed with laurel and wearing the purple-bordered toga, and mounting a tribunal platform which had been built in the Saepta (Enclosure) took his seat beside Augustus. The two consuls seated themselves either side, with the Senators standing in an arc behind. He then greeted the crowd from his chair, before doing the rounds of the various temples.

Book Three: XVIII Return to Germany

The following year (10AD) he returned to Germany. Recognising that Varus’s rashness and carelessness was the cause of his disaster Tiberius did nothing without the approval of his military council, consulting a large body of advisors regarding the course of the campaign, contrary to his previous habits of independence and self-reliance.

He was also more cautious than before. For instance, at the Rhine crossings he set a limit to the amount of baggage each wagon could carry, and refused to start until the wagons had been inspected, to ensure the contents were essential and permissible.

Once beyond the Rhine he behaved as follows: he ate his meals seated on bare turf, and often slept without protection of a tent; he gave all orders in writing, whether the next day’s plans or emergency procedures; and he always added a note that anyone in doubt of anything should consult him personally at any hour of the day or night.

Book Three: XIX Discipline and Caution

Tiberius imposed the strictest discipline on his troops, reviving past methods of punishment and degradation, even down-rating a legionary commander for sending a few of his soldiers over a river to escort his freedman while hunting.

Though he left little to chance, he fought battles more confidently if his lamp suddenly guttered, without being touched, while he was working the previous night, since he trusted in an omen, he would say, that had always brought his ancestors good luck on their campaigns.

And yet, despite his caution, he narrowly escaped death at the hands of a warrior of the Bructeri, who had gained access disguised as a servant. The man was only betrayed by nervousness, but confessed under torture to planning an assassination.

Book Three: XX Triumphant Return to Rome

After a two-year campaign, he returned to Rome (in AD12), and celebrated his postponed Illyrian triumph, accompanied by his generals for whom he had obtained triumphal regalia. Before climbing to the Capitol, he dismounted from his chariot and knelt at Augustus’ feet, the latter presiding over the ceremonies.

He showered rich gifts on Bato, chieftain of the Pannonians, who had once allowed him to escape when he and his troops were caught on dangerous ground, and settled him at Ravenna.

He also gave a thousand-table public banquet, and three gold pieces to every male guest, and out of the value of his spoils he re-dedicated the Temple of Concord (which he had restored between 7 and 10AD), as well as re-dedicating that of Pollux and Castor (which he had restored and re-dedicated in 6AD), in the name of his dead brother, Drusus the Elder, and himself.

Book Three: XXI The Succession

In accordance with the consuls’ decree that he should assist Augustus with the five-year census, and govern the provinces jointly with him, Tiberius waited for the completion of the lustral rites before setting out once more for Illyricum (in 14AD). However Augustus’s last illness caused his recall. Finding Augustus still alive at his return, he then spent the entire day in private conversation with him.

I am aware of the widespread belief that when Tiberius finally left the room, Augustus was heard by his attendants to murmur: ‘Alas, for the people of Rome, doomed to such slow-grinding jaws!’ I know authors too who say that Augustus would freely and openly show his disapproval of Tiberius’s dour manner by breaking off his relaxed and easy mode of conversation mid-flow, whenever Tiberius appeared; and that he only decided to adopt Tiberius on his wife’s insistence, or because he selfishly foresaw that he might only be the more regretted in contrast with such a successor. Yet I refuse to believe such a prudent and far-sighted Emperor could have acted without due consideration in so vital a matter.

In my opinion, Augustus decided having weighed Tiberius’s good and bad points that the good predominated. He did, after all, attest publicly that his adoption of Tiberius was in the national interest, and refers to him in several letters as outstanding in military affairs and the sole defence of the Roman people. To illustrate these points, I give a few extracts from his correspondence:

‘….Farewell, dearest Tiberius, and fortune go with you, as you fight for me and the Muses: Dearest and bravest of men, as I live, and most conscientious of generals, farewell.’

‘I must truly praise your summer campaigns, my dear Tiberius. I am certain no one else could have acted more wisely than you did, in the face of so many difficulties and with so weary an army. All who accompanied you agree that this line might speak of you: One vigilant man restored to us what was ours.’

‘If anything arises that calls for careful consideration, or annoys me, I swear by the god of Truth, I long for my dear Tiberius, and Homer’s verse comes to mind:

What though the fire should rage: if he is with me,

Both will win home, so wise he is and knowing.’

‘When I read, or hear, that you are worn down by continual effort, may the gods curse me, if my flesh does not shudder too; and I beg you to take care of yourself, for if we were to hear you were ill, it would kill your mother and I, and any illness in Rome’s high command would place the Roman people in danger.’

‘It it is no matter whether I am well or no, if you are not.’

‘I beg the gods, if they hate not the people of Rome, to preserve you to us, and grant you health, now and always.’

Book Three: XXII The Death of Postumus

Tiberius suppressed the news of Augustus’ death (in 14AD) until young Agrippa Postumus had been executed by the military tribune appointed as his jailor, whose authority to do so was given in writing. Whether Augustus left the order at his death, as a means of eliminating a future source of trouble, or whether Livia signed it in her husband’s name, with or without Tiberius’s complicity, is not known. In any event, when the tribune reported that he had done as Tiberius commanded, Tiberius denied that he had so ordered, and that the man must account to the Senate for his actions. It appears that Tiberius was merely trying to avoid immediate unpopularity, and subsequent silence on the matter consigned it to oblivion.

Book Three: XXIII The Reading of Augustus’ Will

He then convened the Senate, by virtue of his powers as tribune, and broke the news in a speech, which he had barely begun before he moaned aloud as if overcome by grief, and handed the text to his son Drusus the Younger to finish, with the wish that his life, not merely his voice, might leave him.

Augustus’ will was brought forward and read by a freedman, the Senators who had witnessed it acknowledging their seals, the non-Senatorial witnesses doing so later outside the House. The will commenced: ‘Since cruel fate has carried off my sons Gaius and Lucius, Tiberius Caesar is to be heir to two-thirds of my estate.’ The wording strengthened the conviction of those who believed he had named Tiberius as successor not from choice but out of necessity, without which they felt he would not have written such a preamble.

Book Three: XXIV His Accession

Though Tiberius assumed and exercised Imperial authority at once and without hesitation, providing himself with a bodyguard as an actual and external sign of sovereign power, he refused the title of Emperor for some long while, reproaching, in an unapologetically farcical manner, the friends who urged him to accept it, saying that they had no idea what a monstrous creature the empire was; and keeping the Senators in suspense, with evasive answers and calculated delay, when they fell at his feet begging him to give way.

Some Senators finally lost patience, and in the confusion one shouted: ‘Let him take it or leave it!’ Another openly taunted him saying that, while some were slow to do what they agreed to do, he was slow to agree to do what he was already doing.

At last he did accept the title of Emperor, but only as if he were being forced to, and complaining all the while that they were compelling him to live as a miserable overworked slave, and in such a manner as to betray his hope of one day relinquishing the role. His actual words were: ‘until the day when you think it right to grant an old man rest.’

Book Three: XXV Mutiny and Conspiracy

His hesitation was caused by fear of the dangers that so threatened him from every side, that he often said he was gripping a wolf by the ears.

Clemens, one of Agrippa Postumus’s slaves, had recruited a not insignificant force to avenge his dead master, while Lucius Scribonius Libo, a nobleman, secretly plotted revolution.

Meanwhile soldiers in both Illyricum and Germany mutinied (AD14). The two army groups demanded a host of special privileges, the main one being that they should receive a praetorian’s pay. In addition the army in Germany was disinclined to support an Emperor not of their making, and begged their commander, Germanicus, to seize power, despite his clear refusal to do so. It was the fear above all of such a possibility that led Tiberius to ask the Senate to parcel out the administration in any way they wished, since no man could bear the load without a colleague, or even several. He pretended to ill-health too, so that Germanicus might more readily anticipate a swift succession, or at least a share of power.

The mutinies were quelled, and Clemens, trapped by deception, fell into his hands. But it was not till the second full year of his rule (16AD) that Libo was arraigned before the Senate, since Tiberius was afraid to take extreme measures till his power-base was secure, and was content meanwhile to be on his guard. So he had a lead knife substituted for the double-edged steel one, when Libo accompanied the priests in offering sacrifice, and would not grant Libo a private audience except with his son Drusus the Younger present, even grasping Libo’s right arm throughout, as though he needed to lean on him for support, as they walked to and fro.

Book Three: XXVI His Political Discretion

Free of these anxieties, Tiberius acted like a traditional citizen, more modestly almost than the average individual. He accepted only a few of the least distinguished honours offered him; it was only with great reluctance that he consented to his birthday being recognised, falling as it did on the day of the Plebeian Games in the Circus, by the addition of a two-horse chariot to the proceedings; and he refused to have temples, and priests dedicated to him, or even the erection of statues and busts, without his permission; which he only gave if they were part of the temple adornments and not among the divine images.

Then again, he refused to allow an oath to be taken by the citizens supporting his actions now and to come; and vetoed the renaming of September as ‘Tiberius’ and October ‘Livius’ after his mother Livia. He also declined the title ‘Imperator’ before his name or ‘Father of the Country’ after it, and the placing of the Civic Crown (conferred on Augustus) over his palace door. He was also reluctant to employ the title ‘Augustus’ in his letters, though it was his by right of inheritance, except in those addressed to foreign kings and princes.

After becoming Emperor, he held only three consulships (in AD18, 21, and 31), one for a few days, the second for three months, and a third during his absence (on Capri) only until the Ides of May.

Book Three: XXVII His Dislike of Flattery

He was so averse to flattery that he refused to let Senators approach his litter, whether on business or even simply to pay their respects, and when an ex-consul, apologising for some fault, tried to clasp his knees in supplication, he drew back so sharply he tumbled backwards. Indeed if anyone in a speech or conversation spoke of him in exorbitant terms, he immediately interrupted, reproached the speaker, and corrected his language there and then.

On one occasion, when addressed as ‘My lord and master’ he told the man never to insult him in that fashion again. Another spoke of Tiberius’s ‘sacred’ duties which he amended to ‘burdensome’, and when a second man, appearing before the Senate, claimed he was there ‘on the Emperor’s authority’ Tiberius substituted ‘advice’ for authority.

Book Three: XXVIII His Support of Free Speech

Moreover, in the face of abuse, libels or slanders against himself and his family, he remained unperturbed and tolerant, often maintaining that a free country required free thought and speech.

When, on one occasion, the Senate demanded redress for such offences from those guilty of them, he replied: ‘We lack the time to involve ourselves in such things; if you open that door every thing else will fly out the window; it will provide the excuse for every petty quarrel to be laid at your feet.’

And in the Senate proceedings we may read this unassuming remark: ‘If so-and-so were to take me to task, I would reply with a careful account of my words and deeds; if he persisted, the disapproval would be mutual.’

Book Three: XXIX His Courtesy

And this attitude was the more noteworthy because he showed well-nigh excessive courtesy himself when addressing individual Senators, or the Senate as a whole. On one occasion, when disagreeing with Quintus Haterius, in the House, he said: ‘I ask your pardon if, in my role as Senator, I speak too freely against what you say.’ Then he addressed the House; ‘As I have often said before, honourable members, a well-disposed and right-minded prince, with the great and unconstrained power you have vested in him, must always be a servant of the Senate, and frequently of the people also, and even on occasions of the individual. I do not regret having spoken thus, since I have found you, and still find you, kind, fair and indulgent ‘lords and masters.’

Book Three: XXX His Support of the Senate

He even introduced a species of liberty, by maintaining the traditional dignities and powers of the Senate and magistrates. He laid all public and private matters, small or great, before the Senate consulting them over State revenues, monopolies, and the construction and maintenance of public buildings, over the levying and disbanding of troops, the assignment of legions and auxiliaries, the scope of military appointments, and the allocation of campaigns, and even the form and content of his replies to letters from foreign powers.

When, for example, a cavalry commander was accused of robbery with violence, he forced him to plead his case before the Senate.

He always entered the House unattended, except for one occasion when he was ill, and carried in on a litter, when he at once dismissed his bearers.

Book Three: XXXI His Support of the Consuls and the Rule of Law

He made no issue of the matter when decrees were passed containing views counter to his own. For example, he contended that city magistrates should confine themselves to the City so as to attend personally to their duties, yet the Senate allowed a praetor to travel abroad, with an ambassador’s status. Again, there was an occasion when a legacy provided for the building of a new theatre in Trebia (Trevi), and despite his recommendation that it be used instead to build a new road, the testator’s wishes prevailed. And once, when the Senate divided to vote on a decree, he went over to the minority side and not a soul followed him.

A large amount of business was left solely to the magistrates, and the normal legal process. Meanwhile the Consuls were accorded great importance, such that Tiberius himself rose to his feet in their presence, and made way for them in the street, so that it was no surprise when on one occasion the African envoys complained to the Consuls, face to face, that Caesar, to whom they had been sent, was merely wasting their time.

Book Three: XXXII His Modesty and Respect for Tradition

His respect for the traditions of office is apparent in his reproach of some military governors, themselves ex-consuls, for addressing their despatches to himself and not the Senate, and referring recommendations for military awards to him, as if unaware of their right to grant all such honours themselves. He also congratulated a praetor who, on assuming office, revived the custom of giving a public eulogy of his own ancestors. And he would attend the funerals of distinguished citizens, even witnessing the cremation.

He showed a like modesty and respect for ordinary people and in lesser matters. He summoned the magistrates of Rhodes to appear, because their reports on various matters of public interest omitted the usual prayers for his welfare at the end, but neglected to censure them, and merely sent them home with an order not to repeat their error.

Once, on Rhodes, Diogenes, the grammarian, who used to lecture on the Sabbath, refused to respond to Tiberius when he arrived on a different day of the week, and sent him a message by a slave telling him to return ‘on the seventh day’. When Diogenes appeared in Rome, and waited at the Palace door to pay his respects, Tiberius took his revenge, simply telling Diogenes to return ‘in the seventh year’.

His respect for the people is evident in the answer he gave to a number of provincial governors who had recommended a heavy increase in taxation, writing that it was part of a good shepherd’s duty to shear his flock, but not skin it.

Book Three: XXXIII His Regulation of Abuses

The ruler in him was revealed only gradually, and for a time his conduct, though inconsistent, showed him as benevolent and devoted to the public good. And his early interventions were limited to the elimination of abuse.

For instance, he revoked certain decrees of the Senate, and occasionally would offer the magistrates his services as advisor, sitting beside them on the tribunal, or at one end of the dais. Also, if he heard rumours that influence was being exerted to gain an acquittal, he would appear without warning, and speak to the jury from the floor or from the judge’s tribunal, reminding them of the law and their oath, as well as the nature of the case they were involved in.

In addition, if public morality was threatened by negligence or slipshod habits he undertook to address the situation.

Book Three: XXXIV His Cost and Price Controls

Tiberius cut the cost of public entertainments by reducing actors’ pay and limiting the number of gladiators involved.

Protesting bitterly at the vastly inflated market for Corinthian bronzes, and a recent sale of a trio of mules at a 100 gold pieces each, he proposed a ceiling on the value of household ornaments, and the annual regulation of market prices by the Senate.

In addition, the aediles were ordered to restrict the luxury foods offered in cook-shops and eating-houses, even banning items of pastry from sale. And to set a personal example of frugality, he often served yesterday’s half-eaten leftovers at formal dinners, or half a boar claiming a whole one tasted just the same.

He issued an edict too forbidding the exchange of good luck gifts after the New Year, as well as promiscuous kissing. And though it had been his custom when given a present at that time, to give one back, in person, of four times the value, he discontinued the practice, claiming he was interrupted all January by those denied an audience at New Year.

Book Three: XXXV His Strictures Regarding Marriage and Rank

One ancient Roman custom he revived was the punishment of married women, guilty of impropriety, by decision of a council of their relatives, in the absence of a public prosecutor.

When faced with a Roman knight who had sworn never to divorce his wife, but had found her committing adultery with her son-in-law, he absolved the man of his oath and allowed him to divorce her.

Some married women were notoriously evading the laws on adultery by openly registering as prostitutes and abandoning their rank and privileges. And profligate youths of both the Senatorial and Equestrian orders were voluntarily relinquishing theirs, in order to evade the Senate decree against their appearance on stage or in the arena. Tiberius punished both sets of evaders with exile, as a deterrent to others.

One Senator he downgraded on hearing he had moved to his garden lodge just before the first of July (when terms expired, and rentals were increased), with a view to hiring a house in the City for himself more cheaply later. And he removed another as quaestor, because he had taken a wife before casting lots (to determine his subsequent assignment) but divorced her the day after.

Book Three: XXXVI The Banning of Foreign Rites and Superstitions

Tiberius banned foreign rites (19AD), especially those of the Egyptian and Jewish religions, forcing the adherents of those ‘superstitions’ to burn their religious dress and trappings. On the pretext of their serving in the army, Jews of military age were assigned to provinces with less healthy climates, while others of that race or with similar beliefs he expelled from the City, threatening them with slavery if they refused.

He banished all the astrologers as well, pardoning only those who begged his indulgence and promised to abandon their art.

Book Three: XXXVII His Suppression of Lawlessness

Special measures were taken to protect against highway robbery and outbreaks of lawlessness. Tiberius increased the density of military posts throughout Italy, and in Rome he established an army barracks for the praetorian guards who had previously been billeted in a scattering of lodging houses.

He was careful to deter disturbances in the City, and quelled any which did occur, with the utmost severity. On one occasion, when rival factions quarrelled in the theatre he banished their leaders, as well as the actors over whose performances they were fighting, and refused to recall them despite public entreaties.

When the citizens of Pollentia (Pollenzo) refused to allow the body of a leading centurion to be removed from the forum until the heirs agreed, under threat of violence, to fund a gladiatorial show, Tiberius engineered some pretext to despatch a cohort from Rome, and summon another from the Alpine kingdom of Cottius I. The two forces converged on the city and entered through different gates, then sounded the trumpets and drew their weapons. He condemned a majority of the citizens and the members of the local senate to life imprisonment.

He abolished the traditional right to religious sanctuary throughout the Empire. When the people of Cyzicus perpetrated an outrage against Roman citizens, he stripped them of their freedom earned in the Mithridatic War.

After his accession he refrained from campaigning himself, reluctantly delegating the quelling of rebellions to his generals, when action was unavoidable. He preferred to employ reprimands and threats, rather than force, against foreign kings suspected of disaffection; or as in the cases of Marobodus the German (18AD); Rhescuporis of Thrace (19AD); and Archelaus of Cappadocia (17AD), he lured them with flattery and promises, and then detained them, in the last instance reducing Cappadocia from a kingdom to a province.

Book Three: XXXVIII His Dislike of Travel

For a full two years after his accession as Emperor, Tiberius never once set foot outside the gates of Rome; and only visited neighbouring towns thereafter, the furthest being Antium (Anzio), and then only occasionally for a few days at a time.

Yet he frequently promised to visit the provinces and review the troops there, and every year, almost without fail, he chartered transport and ordered the free towns and colonies to be ready with supplies for his journey. He even went so far as to allow prayers for his safe journey and speedy return, which earned him the ironic nickname ‘Callipides’, after the Athenian mime, famous among the Greeks for his imitation of a runner, pounding away furiously, but never moving an inch.

Book Three: XXXIX His Withdrawal to Campania

However, after the death of his adopted son Germanicus in Syria (19AD), and then his son Drusus the Younger in Rome (23AD), he finally withdrew to Campania, the public believing, and openly stating, that he was likely to die soon, and so would never return. The prediction was almost fulfilled a few days later, as he narrowly escaped death at Terracina, where he was dining in a villa called the Grotto, when a rock-hewn ceiling above collapsed killing several guests and servants. Certainly, he never returned to Rome.

Book Three: XL His Crossing to Capreae

Once Tiberius had dedicated the temples of Capitoline Jupiter at Capua and Augustus at Nola, which was the pretext for his Campanian trip (of AD26), he crossed to Capreae (Capri). He was attracted by the island’s limited access, which was confined to one small beach, the rest of its coast consisting of massive cliffs plunging sheer into deep water.

However after a catastrophe at Fidenae (27AD), where more than twenty thousand spectators were killed when part of the amphitheatre collapsed during a gladiatorial show, he was entreated to visit the mainland. There he gave audiences to all who asked, the more readily as he was making amends for having given orders on leaving the city that he must not be disturbed on his journey, and having sent away those who had tried to approach him regardless.

Book Three: XLI His Final Retirement to Capreae

Returning to Capreae, he abandoned all affairs of state, neither filling vacancies in the Equestrian Order’s jury lists, nor appointing military tribunes, prefects, or even provincial governors. Spain and Syria lacked governors of Consular rank for several years, while he allowed the Parthians to overrun Armenia, Moesia to be ravaged by the Dacians and Sarmatians, and Gaul by the Germans, threatening the Empire’s honour no less than its security.

Book Three: XLII His Moral Decline

Furthermore, with the freedom afforded by privacy, hidden as it were from public view, he gave free rein to the vices he had concealed for so long, and of which I shall give a detailed account from their inception.

At the very start of his military career, his excessive liking for wine caused him to be dubbed Biberius Caldius Mero (‘Drinker of Hot Neat Wine’) for Tiberius Claudius Nero. Then, as Emperor, while busy reforming public morals, he spent two days, and the intervening night, swilling and gorging with Pomponius Flaccus and Lucius Piso, appointing one immediately afterwards Governor of Syria (32AD), and the other City prefect, and describing them in their commissions as the most delightful of friends at all hours.

Again, he invited himself to dinner with Cestius Gallus, an extravagant old lecher, whom Augustus had once down-graded and whom he himself had reprimanded a few days before in the Senate, insisting that Cestius arrange everything as he usually did, including the naked girls waiting at table.

And he preferred an obscure candidate as quaestor, over men of noble family, because, when challenged at a banquet, the man successfully drained a huge amphora of wine.

He paid Asellius Sabinus two thousand gold pieces for penning a dialogue which included a contest between a mushroom, a warbler, an oyster and a thrush, and established a new Office of Pleasures run by a knight, Titus Caesonius Priscus.

Book Three: XLIII His Licentiousness on Capri

In retirement, on Capreae (Capri) he contrived his ‘back-room’, a place for hidden licentiousness, where girls and young men, selected for their inventiveness in unnatural practices, whom he dubbed spintriae (sex-tokens), performed before him in groups of three, to excite his waning passions.

Its many little cubicles were adorned with the most lascivious paintings and sculptures, and equipped with the works of Elephantis, in the event that any performer required an illustration of a prescribed position.

In the woods and glades, he contrived various places where boys and girls, acting as Pans and Nymphs, prostituted themselves, among the caves and rocky hollows, so that the island was openly, and punningly, called Caprineum, ‘The Old Goat’s Garden’.

Book Three: XLIV His Gross Depravities

He indulged in greater and more shameful depravities, things scarcely to be told or heard, let alone credited, such as the little boys he called his ‘fry’ whom he trained to swim between his thighs to nibble and lick him; or his letting un-weaned healthy babies suck his penis instead of their mother’s nipple, he being, by age and nature, fond of such perversions.

When a painting by Parrhasius was bequeathed to him, showing Atalanta giving head to Meleager, the art work to be substituted by ten thousand gold pieces instead if he disliked it, he not only kept it but had it attached to his bedroom wall.

There’s a story too, that drawn to the incense-bearer’s beauty at a sacrifice, and unable to contain himself, he barely allowed the ceremony to end before hurrying the boy and his flute-playing brother off, and abusing them both. When they protested at the rape, Tiberius had their legs broken.

Book Three: XLV His Abuse of Women

His habit of being pleasured by fellatio with even high-born women is highlighted by the death of a certain Mallonia, who was summoned to his bed. When she refused vigorously to comply, he turned her over to his informers, and even in court could not refrain from demanding ‘whether she was sorry’. Once home, after the trial, she stabbed herself, after a tirade against the stinking, hairy foul-mouthed old goat. A reference to him in the next Atellan farce was greeted with loud applause, and quickly went the rounds: ‘The old he-goat licks the does with his tongue.’

Book Three: XLVI His Frugality

Close-fisted and miserly in financial matters, he paid his staff’s keep on campaign and during foreign tours but no salary. Only once did he treat them well, and that was due to Augustus’s generosity. On that occasion, Tiberius divided them into three categories, according to rank; giving the first six thousand gold pieces each, the second four thousand, and the third, whom he called his Greeks not his friends, two thousand.

Book Three: XLVII His Lack of Public Generosity

No fine public works marked his reign, since the only ones he started, namely the Temple of Augustus and the restoration of Pompey’s Theatre, were still incomplete at his death.

He avoided giving public shows, and hardly ever attended those given by others, for fear some request would be made of him, more so after he was obliged to buy the freedom of a comic actor named Actius.

After relieving the debts of a few Senators, he ceased such aid later, unless they could prove just cause to the Senate for their financial state. Diffidence and a sense of shame then prevented many from applying, including Hortalus, the grandson of Quintus Hortensius the orator, who though quite poor had fathered four children at Augustus’s urging.

Book Three: XLVIII Rare Exceptions

There were only two occasions on which he showed generosity to the public. He did respond to pressure at a time of great financial distress, by providing a three-year interest-free loan of a million gold pieces, after a failed attempt to resolve the situation by decree had ordered money-lenders to invest two thirds of their capital, and the debtors to redeem two thirds of their debt, in land. And again, he relieved the great loss and hardship caused to the owners when blocks of houses on the Caelian Mount were destroyed by fire (in AD27), though he made so much of his generosity that he insisted on the Caelian being renamed the ‘Augustan’ Mount.

The legacies left to the army in Augustus’ will, Tiberius doubled, but thereafter he never handed out gifts to the men, except for ten gold pieces to each praetorian who refused to follow Sejanus, and awards to the Syrian legions because they chose not to place consecrated images of Sejanus among their standards.

He rarely granted veterans their discharge, reckoning on saving the associated bounty, if they died in service.

And his sole act of generosity towards the provinces was occasioned by the damage caused to various cities in Asia Minor during an earthquake.

Book Three: XLIX His Rapacity

As time went by, he became rapacious: it is well known for example that he hounded the wealthy Gnaeus Lentulus Augur into naming him as sole heir, and then by inspiring fear drove the terrified man to suicide (in 25AD). Then there was a noblewoman, Aemilia Lepida, the divorced wife of Publius Quirinius, a rich and childless ex-consul. She was tried (in 20AD) and executed solely to gratify Quirinius, who accused her of having tried to poison him twenty years previously.

Again, Tiberius behaved shamelessly, in confiscating the property of leading provincials of Spain, Gaul, Syria and Greece, on trivial charges, some accused of no more than holding suspiciously large amounts of cash. He deprived many individuals and states of their ancient immunities, mineral rights and taxation powers, too. And he treacherously stole the vast treasure that Vonones, the Parthian king, had brought to Antioch, when dethroned by his subjects. Though Vonones believed himself under Rome’s protection, Tiberius had him executed regardless.

Book Three: L His Hatred of his Kin

His hatred of kin first showed in his disloyalty to his brother, Drusus the Elder, when he disclosed the contents of a private letter in which Drusus had suggested forcing Augustus to restore the Republic. Later he turned against the rest of his family.

On becoming Emperor, far from showing the courtesy or kindness to his wife Julia, in her exile, which one might have anticipated, he was more severe than Augustus who had simply confined her to Rhegium (Reggio) while Tiberius now refused to allow her to leave her house, or enjoy company. He even deprived her of the income and allowances her father, Augustus, had permitted her to receive, under pretext of applying the common law as Augustus failed to mention them in his will.

As for his mother, Livia, he claimed she wished to rule equally with himself, and was so annoyed at this that he avoided frequent meetings and long conversations lest he appeared to be receiving her advice, though he did in fact follow it from time to time. The Senate so offended him by their decree adding ‘Son of Livia’ to ‘Son of Augustus’ as one of his honorific titles, that he refused to allow her to be called ‘Mother of the Country’ or receive any other notable public honour. Moreover he warned her, as a mere woman, not to interfere in affairs of state, and emphasised the point after hearing of her attendance at a fire near the Temple of Vesta, where she had urged the populace and military to greater efforts, just as she would have done if Augustus were still alive.

Book Three: LI His Later Enmity Towards Livia

Later he quarrelled with her openly; and the reason, they say, was as follows. She urged him repeatedly to enter a new citizen as a juror, he saying he would, but only if his action was recorded in the list as down to her. At this, Livia lost her temper, and produced a bundle of Augustus’s letters from her shrine to him, letters written to her, which she read aloud, regarding Tiberius’s harsh and stubborn nature.

Tiberius was so disconcerted at her hoarding them so long, and confronting him with them so spitefully, that some consider this as the prime reason for his retirement (to Capri). In any event, after he left Rome he only saw her once during the remaining three years of her life, and then only on a single day for a few hours. When she fell ill shortly afterwards, he chose not to visit her. Then when she died (in 29AD), he delayed several days, despite a promise to attend, until the corruption and putrefaction of the corpse made an immediate funeral essential, whereupon he prohibited her deification, claiming he was acting on her own instructions.

He went on to annul the provisions of her will, then quickly conspired the downfall of her friends and confidants, not even sparing those to whom, on her deathbed, she had entrusted her funeral arrangements, and actually condemning a knight among them to the treadmill.

Book Three: LII His Lack of Affection for Drusus the Younger and Germanicus

He lacked affection not only for his adopted son Germanicus, but even for his own son Drusus the Younger, whose vices were inimical to him, Drusus indeed pursing loose and immoral ways. So inimical, that Tiberius seemed unaffected by his death (in 23AD), and quickly took up his usual routine after the funeral, cutting short the period of mourning. When a deputation from Troy offered him belated condolences, he smiled as if at a distant memory, and offered them like sympathy for the loss of their famous fellow-citizen Hector!

As for Germanicus, Tiberius appreciated him so little, that he dismissed his famous deeds as trivial, and his brilliant victories as ruinous to the Empire. He complained to the Senate when Germanicus left for Alexandria (AD19) without consulting him, on the occasion there of a terrible and swift-spreading famine. It was even believed that Tiberius arranged for his poisoning at the hands of Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso, the Governor of Syria, and that Piso would have revealed the written instructions at his trial, had Tiberius not retrieved them during a private interview, before having Piso put to death. As a result, the words: ‘Give us back Germanicus!’ were posted on the walls, and shouted at night, all throughout Rome. The suspicion surrounding Germanicus’ death (19AD) was deepened by Tiberius’s cruel treatment of Germanicus’s wife, Agrippina the Elder, and their children.

Book Three: LIII His Treatment of Agrippina the Elder

When Agrippina, his daughter-in-law, was a little too free with her words after her husband’s death, he grasped her hand and quoted the Greek line: ‘Think you some wrong is done you, little one, should you not reign?’ From then on, he never deigned to speak to her. Indeed, he even ceased to invite her to dinner, after she showed fear of accepting an apple he offered her, on the pretext that she had accused him of poisoning her; whereas he had determined on the whole business beforehand, in the expectation that if he offered the fruit she would refuse it as containing certain death.

Ultimately he charged her with seeking sanctuary in the temple of her grandfather Augustus, or with the army abroad, and exiled her to Pandataria (in 29AD). When she reviled him, he had her flogged by a centurion, causing her to lose an eye. When she resolved to starve herself to death, he had her forcibly fed, and when through pure determination she succeeded in ending her life, he attacked her memory with vile slanders, persuaded the Senate to declare her birthday a day of ill omen, claimed credit for not having had her strangled and her body thrown down the Stairs of Mourning, and even permitted a decree to be passed, in recognition of his outstanding clemency, congratulating him, and voting a golden gift for consecration to Capitoline Jupiter.

Book Three: LIV His Treatment of His Grandsons Nero and Drusus

By his adopted son Germanicus he had three grandsons, Nero Julius Caesar, Drusus Julius Caesar, and Gaius Julius Caesar (Caligula), and by his son Drusus the Younger one grandson, Tiberius Gemellus. Death having bereft him of his son Drusus the Younger (in 23AD), he recommended Nero and Drusus, the eldest sons of Germanicus, to the Senate, and celebrated their coming of age by distributing gifts to the people. But when he found that prayers for their well-being were added to his at the New Year, he referred the issue to the Senate, suggesting that such honours were only suitable for those who were mature and of proven character.

By showing his true dislike for them, he exposed them thereafter to false accusations from all and sundry, and by contriving various ruses to provoke their resentment while ensuring their condemnations of him were betrayed, he was able to file bitter accusations against them. Both were pronounced public enemies, and starved to death; Nero on the island of Pontia (30AD) and Drusus (33AD) in a cellar of the Palace.

Some believe that when the executioner, who pretended to be there on Senate authority, showed him the noose and hooks (for dragging away the body), Nero chose to commit suicide, while it is said Drusus was so tormented with hunger that he ate the flock from his mattress, and that their remains were so widely scattered that gathering them, in later years, for burial proved a challenging task.

Book Three: LV His Treatment of His Advisors

In addition to various old friends and intimates, Tiberius had asked the Senate to select a council of twenty senior men to advise him on State affairs. Of all these he spared only two or three, ruining the rest on various pretexts, including Aelius Sejanus, whose downfall precipitated that of many others. Sejanus he had granted plenary powers, not out of liking for the man, but because he seemed loyal and cunning enough to compass the destruction of Germanicus’ sons, and secure the succession for his son Drusus the Younger’s boy, Tiberius Gemellus.

Book Three: LVI His Treatment of His Greek Companions

He was no kinder towards his Greek companions, whose society he especially appreciated. One of them, Xeno, happening to speak in a somewhat affected manner, Tiberius asked what annoying dialect that might be. When Xeno replied that it was Doric, Tiberius thinking he was being taunted with his old place of exile Rhodes, where Doric Greek was spoken, immediately exiled him to Cinaria (Kinaros).

It was his habit to pose questions, at the dinner table, suggested by his reading. Hearing that Seleucus the grammarian had enquired of the Imperial attendants what works the Emperor was then reading, so as to be prepared, Tiberius first dismissed him from his company, and later drove him to suicide.

Book Three: LVII His Inherent Cruelty

Even in boyhood, his cold and cruel temperament was not totally hidden. Theodorus of Gadara, his teacher of rhetoric had the wit to recognise it early, and characterised it clearly, calling him, when reproving him, in Greek: ‘mud kneaded with blood.’ But once he was Emperor, even at the start when he was still behaving temperately and courting popularity, it became more noticeable.

On one occasion, as a cortege was passing by, some joker called to the corpse to let Augustus know that his bequests to the people were still unpaid. Tiberius had the man dragged before him, and told him he should have what he was owed, and to go report the truth to Augustus himself; whereupon, he ordered the man’s execution.

Not long afterwards, a knight called Pompeius vigorously opposed some action of his in the Senate. Tiberius threatened him with prison, declaring he’d make ‘a Pompeian of Pompeius’, in a cruel pun on the man’s name, and the fate of Pompey’s faction in days gone by.

Book Three: LVIII His Abuse of Lese-Majesty

At about this time, a praetor asked whether the courts should be convened to consider cases of lese-majesty, to which he answered that the law should be enforced, and so it was, rigorously.

One man, who had removed the head from a statue of Augustus in order to replace it with someone else’s, was tried in the Senate, and because the witnesses’ evidence was in conflict they were tortured. He was found guilty, and a spate of accusations followed, such that the following actions became capital crimes: to strike a slave, or change one’s clothes, near a statue of Augustus; to be found carrying a ring or coin engraved or stamped with his image in a toilet or brothel; and to criticise anything he had ever said or done.

It culminated in a man being executed simply for letting an honour be voted him, in his home town, on a day when honours had once been voted to Augustus.

Book Three: LIX Satires Directed Against Him

Under the guise of a strict reform of public morals, Tiberius perpetrated so many other cruel and merciless actions merely to gratify his natural temperament that satirists resorted to expressing their hatred of those dark days, and their prophecies of evils to come, in verse:

‘Merciless, cruel, want it all spelt out, in a line or two?

I’ll be damned if your own mother feels any love for you.’

‘You’re no knight, and why? You don’t own a cent;

No citizen, what’s more: Rhodes was your banishment.’

‘Caesar, you’ve transformed Saturn’s Golden Age;

Iron the age is; now, that you command the stage.’

‘No wine now for one who finds blood just as fine,

He drinks blood eagerly, as he once drank the wine.’

‘See Sulla the Fortunate: for himself, my friend, not you;

Or Marius, if you like: see here, retaking Rome too;

Or a Mark Antony, not just once, rousing civil war,

See, time and time again, his hands deep-dyed in gore;

And cry now: Rome is done! They all reign bloodily,

Who out of exile come to rule, with like authority.

At first, Tiberius wished them thought the work of dissidents, unable to stomach his reforms, voicing their anger and frustration rather than considered judgement, and from time to time would say: ‘Let them hate me, as long as they respect me.’ But later he himself proved their views only too certain and correct.

Book Three: LX His Cruelty on Capreae

Not long after he retired to Capreae (Capri), he was alone on the cliff-top, when a fisherman who had clambered over the rough and pathless crags at the rear of the island, suddenly intruded on his solitude to offer him a huge mullet he had caught. Startled, Tiberius had his guards scrub the man’s face with the fish. Because in his torment, the simpleton gave thanks for not offering Tiberius the enormous crab he had caught, instead, Tiberius sent for that too, and had the man’s skin scraped with its claws as well.

He had a praetorian guardsman executed merely for stealing a peacock from his gardens, and again, when his litter was obstructed by brambles when making a trip, he had the centurion, charged with finding a clear path, pegged on the ground and flogged almost to death.

Book Three: LXI The Increasing Cruelty of His Reign

He increasingly indulged in every kind of cruelty, never lacking the pretext, and persecuting firstly his mother’s friends and acquaintances, then those of his grandsons and daughter-in-law, and finally those of Sejanus. After Sejanus’ death he behaved more cruelly than ever, showing that his ex-favourite had not corrupted him but merely provided the opportunities he himself sought. Yet in his brief and sketchy autobiography we find him writing that he punished Sejanus for venting his hatred on Germanicus’s children, when it was he himself in fact who had Nero killed while Sejanus was newly under suspicion, and then Drusus after Sejanus had fallen.

A detailed account of his cruelties would make a long story, and it suffices simply to give examples of the barbarous forms they took. There was never a day without an execution, not even sacred days and holidays; for even New Year’s Day saw its victims. Many were accused and condemned alongside their children, and even by their children, while the relatives were forbidden from mourning them. The informant’s word was law, and special rewards went to the accusers and even the witnesses.

One poet was charged with slandering Agamemnon in his tragedy, and a historian with calling Brutus and Cassius the ‘Last of the Romans’. The authors were promptly executed and their works destroyed, though the texts had been read publicly, and with approval, in the presence of Augustus himself some years earlier.

Of those consigned to prison, some were denied not only the consolation of books, but even the ability to converse and exchange thoughts. Though some of those summoned to present their defence, certain of being convicted, and wishing to avoid the mental pain and humiliation of a trial, slashed their wrists at home, yet, if they were still alive, their wounds were bandaged, and they were dragged to prison still twitching, more dead than alive. Others took poison in open session before the Senate.

The corpses of those executed, as many as twenty a day, and including those of women and children, were thrown down the Stairs of Mourning then dragged with hooks to the Tiber. Immature girls, since sacred tradition deemed it impious to strangle virgins, were violated first by the executioner and then strangled.