Cornelius Tacitus

The Annals

Book IV: I-XXXIII - The rise of Sejanus, the death of Drusus

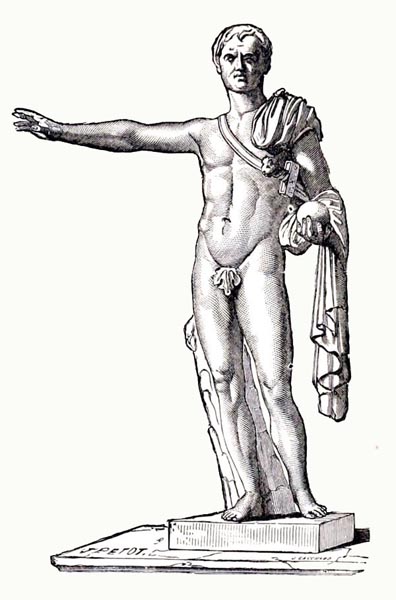

‘Pompey’

History of Rome and the Roman people, from its origin to the establishment of the Christian empire - Victor Duruy (1811 - 1894) (p52, 1884)

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2017 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book IV:I The origins of Aelius Sejanus.

- Book IV:II Sejanus builds his forces.

- Book IV:III Sejanus and Livilla (Claudia Livia Julia)

- Book IV:IV Tiberius reviews the state of the military.

- Book IV:V The allocation of Roman forces in AD23.

- Book IV:VI The management of public affairs in AD23.

- Book IV:VII Drusus disapproves of Sejanus.

- Book IV:VIII Drusus murdered by poisoning.

- Book IV:IX The funeral of Drusus.

- Book IV:X A rumour concerning Drusus’ death.

- Book IV:XI Tacitus rejects the oral tradition.

- Book IV:XII Sejanus works to discredit Agrippina.

- Book IV:XIII Tiberius conducts state business.

- Book IV:XIV Religious asylum, and expulsion of the actors from Italy.

- Book IV:XV The trial of Lucilius Capito.

- Book IV:XVI The appointment of the Flamen of Jupiter (Flamen Dialis)

- Book IV:XVII Tensions regarding the possible succession.

- Book IV:XVIII Sejanus attacks Gaius Silius and Titius Sabinus.

- Book IV:XIX Silius and his wife Sosia Galla condemned.

- Book IV:XX Sosia exiled.

- Book IV:XXI Charges against Calpurnius Piso and Cassius Severus.

- Book IV:XXII Plautius Silvanus murders his wife Apronia.

- Book IV:XXIII The situation in North Africa.

- Book IV:XXIV Dolabella moves against Tacfarinas.

- Book IV:XXV The death of Tacfarinas.

- Book IV:XXVI Dolabella denied triumphal insignia.

- Book IV:XXVII A slave revolt.

- Book IV:XXVIII A son accuses his father.

- Book IV:XXIX Tiberius relentless.

- Book IV:XXX Tiberius supports the informers.

- Book IV:XXXI The contrasting sides of Tiberius’ nature.

- Book IV:XXXII Not all history is filled with glorious events.

- Book IV:XXXIII Modern and ancient times.

Book IV:I The origins of Aelius Sejanus

The consulate of Gaius Asinius and Gaius Antistius seemed destined, for Tiberius, to deliver a ninth year of public order and domestic prosperity (since he counted the death of Germanicus amongst his blessings) when fate brought sudden turbulence, revealing him as a tyrant or at least a force for tyranny. The origin and cause were to be found in Aelius Sejanus, prefect of the praetorian guard, whose influence I have mentioned before: now I will speak of his beginnings, character, and the criminal actions by which he set out to gain power.

Born at Volsinii (Bolsena), his father being Seius Strabo, a Roman knight, Sejanus was in early youth a follower of Gaius Caesar, grandson of the divine Augustus, and was rumoured to have sold his virtue to that wealthy lover of excess Apicius. He soon captured Tiberius, by his various arts, such that the man who was an enigma to others proved open and unreserved with Sejanus alone, yet it was achieved not so much by his own ingenuity (since he was ultimately defeated by those very arts) than by divine anger against the Roman State, to whose corresponding misfortune he rose and fell.

Physically he could endure hard work, mentally he was audacious; hiding his role, to incriminate others; at once fawning and insolent; a figure outwardly modest, within possessed by the desire for absolute power, which sometimes prompted him to bribery and excess, but more often to an effort and vigilance no less harmful for being adapted so often to the winning of a throne.

Book IV:II Sejanus builds his forces

Sejanus added to the prefect’s power, which was previously constrained, by gathering in one encampment the cohorts dispersed throughout Rome, so that they might receive their orders simultaneously, and gain confidence from their numbers, strength, and visibility, while generating fear in others. He justified this by claiming that troops when dispersed became unruly; that if an emergency occurred help was more effective when they were concentrated; and that discipline could be maintained if their camp was at some distance from the city’s attractions.

Their quarters complete, he gradually made his presence felt among the soldiers, meeting and greeting them by name; by the same token he himself selected the centurions and tribunes. Nor did he fail to tempt the senators with the honours and governorships available to his supporters, while Tiberius, was ready and willing to praise this ‘partner in his labours’ not only in conversation, but also to the Senate and people, and allowed statues of Sejanus to be honoured in the theatres, forums, and at legionary headquarters.

Book IV:III Sejanus and Livilla (Claudia Livia Julia)

Yet an Imperial House filled with Caesars, namely Tiberius himself, an adult son (Drusus the Younger), and maturing grandsons (Nero Julius, Drusus Julius, Caligula, and the Gemelli), gave his ambitions pause, since a determined attack on all of them simultaneously was risky, while guile favoured an interval between treacherous actions. He decided to proceed yet more secretly beginning with Drusus the Younger, against whom he bore fresh resentment. For Drusus, impatient of rivals, and excitable of spirit, had raised his hand against Sejanus during a chance encounter and, when he responded, had struck him in the face.

On considering every possibility, it seemed easiest to make use of Drusus’ wife, Livilla (Claudia Livia Julia), Germanicus’ sister, an ugly child in her youth, but later of outstanding beauty. Playing the hot lover, he drew her into adultery, and then after the first sinful encounter (a woman who has once put aside shame will thereafter refuse nothing) he brought her to dreams of marriage, of partnership in power, and so to the murder of her husband.

Livilla, grand-niece to Augustus, daughter-in-law to Tiberius, the mother of Drusus’ children, dishonoured herself, her ancestors, and her offspring, with a small-town adulterer, so exchanging for a virtuous present the expectations of an uncertain and criminal future. Eudemus, friend and physician to Livilla, was in the know, his role a pretext for frequent private meetings. Sejanus closed his doors to his wife Apicata, who had borne him three children, to allay his mistress’ suspicions. But the magnitude of their deceit brought anxieties, postponements, and an occasional divergence of views.

Book IV:IV Tiberius reviews the state of the military

Meanwhile, at the start of the year, Drusus Julius, the son of Germanicus, had assumed the adult toga, the Senate repeating the compliments decreed to his brother, Nero Julius. Tiberius then spoke, praising his own son, Drusus the Younger, highly, for showing the benevolence of a father towards his brother Germanicus’ family. For Drusus, hard though it is for power and harmony to exist together, was held to be equable towards, or at least not hostile to, the lads.

Then the old, oft-repeated pretence of a planned trip to the provinces was discussed. The emperor gave his excuses, the multitude of (disaffected) veterans and the (unpopular) requirement for conscripts to supplement the forces, since there was a lack of volunteers for service, and even when there were sufficient the old discipline and bravery was absent, those who enlisted of their own free will being beggars and vagrants.

He briefly covered the list of legions, and the provinces they protected, a subject which I think I should also pursue, involving the Roman forces then under arms, the allied kings, and the narrower extent of our empire at that time.

Book IV:V The allocation of Roman forces in AD23

Italy was defended, in eastern and western waters, by the fleets based at Misenum (Miseno) and Ravenna, respectively, and the adjoining coast of Gaul by a flotilla of war-vessels, captured by Augustus (Octavian) at the battle of Actium, and transferred with a full complement of oarsmen to Forum Julii (Fréjus).

Our main strength, however, was on the Rhine, eight legions equally ready to relieve the German provinces or Gaul, while three legions held the recently-subdued (19BC) Spanish provinces.

King Juba II (of Numidia) had received Mauretania as a gift from the people of Rome. Two legions held the rest of North Africa, and the same number held Egypt. Then from Egypt’s north-eastern boundary to the Euphrates, four legions covered the immense extent of those lands, while on the north-western borders the Albanian (Azerbaijan), Iberian (Georgia) and other kingdoms were protected from enemy forces by the might of Rome.

Thrace was held by Rhoemetalces II and the sons of Cotys VIII; the banks of the Danube by two legions in Pannonia and two in Moesia, with two more located in Dalmatia to the rear of these, near enough to be called upon if Italy requested emergency aid.

However, Rome had its own troops, nine praetorian and three urban cohorts, customarily recruited from Etruria and Umbria, ancient Latium, and the oldest Roman colonies. And at appropriate provincial locations there were allied warships, cavalry and auxiliary cohorts, in strength not much inferior to these: difficult to keep track of, since they were moved hither and thither, increasing or sometimes diminishing in numbers, according to the needs of the moment.

Book IV:VI The management of public affairs in AD23

It would be appropriate, I think, to review the other offices of State, and how they were run, up to this point, since the year (AD23) saw a change for the worse in Tiberius’ rule.

Firstly then, public matters, and in exceptional cases private ones, were brought before the Senate, for discussion by the leading members, any lapse into sycophancy being curtailed by the emperor himself. In bestowing honours, he bore in mind the nobility of a man’s ancestors, military distinction, and outstanding civic ability, so that it was quite clear no better choice could be made. The consulate, the praetorship still made a show, and the powers even of the minor magistrates were exercised; while the laws, apart from cases of treason, were properly applied.

Next, the corn-distribution and the tax revenues along with other public income were handled by companies of Roman knights. His own affairs Tiberius entrusted to proven individuals, sometimes outside the nobility, based on their reputation; and once appointed, men held office, almost indefinitely, many growing old in such service.

The people were, indeed, troubled with the high cost of food, but none of the blame for that lay with the emperor: he spared neither effort nor expense in countering the effects of poor harvests and turbulent seas. And he ensured that the provinces were not troubled by fresh burdens, and that those which existed were imposed without greed or excessive severity by the magistrates: physical violence and the forfeiture of assets were done away with.

His holdings of land in Italy were few, his number of slaves limited, his household run by a small number of freedmen; and any arbitration required between himself and private citizens was decided in court and according to the law.

Book IV:VII Drusus disapproves of Sejanus

All this Tiberius still observed, not indeed with a courteous manner, but in a brusque and often terrifying fashion, until it was overturned by the death of Drusus the Younger: for it held while his son lived, since Sejanus, as yet in the infancy of his power, wished to be known for his wise counsel, and feared vengeance from one who failed to conceal his hatred and complained endlessly that with the succession assured an outsider was nevertheless called upon to assist in governing.

And how long, asked the complainant, before helper became colleague? The first steps towards power are arduous: but once made, followers and servants gather round. Now an encampment had been laid out, according to the prefect’s wishes; the guards were at his command; his portrait had appeared in Pompey’s Theatre; his grandsons would be of the House of the Drusi: restraint was to be prayed for beyond that, in the hope that he might rest content.

Such views Drusus proclaimed, often and to many a hearer, while even his private thoughts were betrayed by his adulterous wife.

Book IV:VIII Drusus murdered by poisoning

Sejanus, therefore, judging the moment ripe, settled upon a poison that worked so slowly as to simulate a chance infection. This concoction was administered to Drusus by the eunuch Lygdus, as was only determined some eight years later. Tiberius continued to attend the Senate, moreover, throughout the illness, either confident of his son’s recovery or to show his strength of mind.

He continued to do so even when Drusus was dead but not yet interred. The consuls having seated themselves on the ordinary benches as a sign of mourning, he suggested they resume their place in the seats of honour, and as the senators continued to shed tears he suppressed their lamentation, and encouraged them with a formal speech.

Even he was not unaware, he said, that he might be criticised for appearing before the Senate with a grief so fresh: mourners were often unable to bear their own relatives’ condolences, could scarcely bear the sight of day, nor were they to be condemned as lacking in fortitude: yet he himself sought greater solace in embracing affairs of state.

Saddened as he was, by Livia’s extreme old age, his own declining years and his grandsons’ immaturity as yet, he nevertheless asked that Germanicus’ elder sons (Nero Julius and Drusus Julius) be introduced. The consuls exited, spoke reassuringly to the youths, brought them in and stood them beside Tiberius.

Clasping their arms, he said; ‘Senators Elect, their father lost, I gave them into their uncle Drusus’ care, and begged him, though he had children of his own, to treat them as his own flesh and blood, educate them, and shape them after himself and for posterity. Now Drusus is taken from us, I direct my request towards you, in the sight of your country and the gods: protect these great-grandchildren of Augustus, born of illustrious ancestors, guide them, perform your duty and my own. Nero Julius and Drusus Julius, these shall be your parents. Your birth determines that your fate, for good or ill, concerns the State.’

Book IV:IX The funeral of Drusus

All this was heard amidst copious tears, then prayers for future happiness; and if he had only set a limit to his oratory, he would have filled the minds of his audience with sympathy and pride: but by reverting to his usual comments, idle and so often ridiculed, concerning the restoration of the Republic with the consuls or others taking the reins, he destroyed the credibility even of that which was true and honourable in his speech.

The same honours were decreed for Drusus the Younger as those for Germanicus, with the further additions that sycophancy normally loves to grant the second time around. The most notable feature of the funeral procession was the long line of ancestral images to be seen, from Aeneas, the origin of the Julian line, through all the Alban kings, Romulus the founder of Rome, and the Sabine nobility, to Appius Claudius Sabinus (consul 495BC, founder of the Claudian line) and the rest of the Claudian House.

Book IV:X A rumour concerning Drusus’ death

In relating the death of Drusus, I have given the version recorded by most authors, and of those the most trustworthy: but I should not omit a rumour current at the time, so strong indeed that it has not yet faded. It claims that Sejanus, after seducing Livilla to his wicked ways, attached himself also to the eunuch Lygdus, whose age and looks endeared him to his master, Drusus, and placed him among the latter’s foremost servants.

Then, it is said, once the conspirators had agreed a place and time to administer the poison, he carried his audacity to the point of ascribing the plot to Drusus, warning Tiberius privately that Drusus aimed to poison him, and to avoid the first cup offered when dining with his son.

Deceived by the lie, the tales goes, the ageing emperor, on seating himself at the banquet, took the drink and passed it to Drusus. He, as a young man would, drank deep, unknowingly creating the suspicion that, from fear and shame, he had condemned himself to a fate intended for his father.

Book IV:XI Tacitus rejects the oral tradition

The commonly repeated tale above, supported by no firm evidence, may be swiftly refuted. What man of even moderate prudence, let alone Tiberius with his vast experience, would inflict death on his son without a hearing, and that by his own hand, while denying all chance of repentance? Why not torture the servant who delivered the poisoned chalice, search out his prompter, and employ, in short, the customary delay and reluctance Tiberius showed even to strangers, in the case of an only son, never before charged with any crime?

Yet since Sejanus was held to be the source of all evil, and Tiberius held him in extreme affection while others hated them both, the monstrous and fantastic was readily believed, rumour being never so wild as at the death of princes. And then the stages in the crime had been betrayed by Apicata, Sejanus’ wife, and revealed by Eudemus and Lygdus under torture. Nor was a single historian found so hostile as to charge Tiberius with the crime, though all else was being uncovered and exaggerated.

My own motive for recording and refuting this tale it in order to reject, with this one striking example, the unreliability of oral tradition, and to ask those, into whose hands my work might fall, not to prefer, in their eagerness, some widely-held yet incredible story to truth uncorrupted by myth.

Book IV:XII Sejanus works to discredit Agrippina

Nevertheless, while Tiberius praised his son from the Rostra, the Senate and people of Rome assumed the dress and accent of mourning more as a matter of pretence than out of willingness, and secretly rejoiced at the revival of the House of Germanicus. This growing support and Agrippina’s barely-hidden maternal hopes hastened its downfall.

For when Sejanus found that no vengeance was sought on those who had brought about Drusus’ death, that it was indeed unlamented by the public, he grew more daring in wickedness, and succeeding in his first venture, now debated with himself as to the best means of destroying Germanicus’ sons, whose succession seemed certain.

I was impossible to use poison against the three of them, since they were more than well protected and Agrippina’s integrity was unassailable. He therefore attacked her for her insolence, and by playing on Livia’s former animosity towards her, and Livilla’s recent guilty involvement, induced them to denounce her to Tiberius, as a woman over-proud of her offspring, high in public favour, and covetous of the crown.

Also, Livilla worked to further the estrangement between an old woman, naturally anxious to retain her power, and her grandson’s widow, employing covert spies, among whom was Julius Postumus, one of her grandmother’s intimates due to his adulterous connection with Mutilia Prisca, and therefore suited to her scheming, since Prisca had great influence over Livia’s thoughts. Agrippina’s closest friends too were seduced by scurrilous gossip into provoking her excitable spirit.

Book IV:XIII Tiberius conducts state business

Meanwhile, Tiberius, without pause in his attention to public affairs, found solace in his labours, dealing with legal cases at home, and petitions from the provinces. At his prompting, the Senate decreed that the towns of Cibyra (Golhisar, Turkey) in Asia Minor and Aegium (Aegio, Greece) in Achaia, damaged by earthquake, would be excused paying tribute for a period of three years.

Also, Vibius Serenus, the proconsul of lower Spain (Hispania Ulterior), was convicted of State violence and was deported, due to his aggressive nature, to the Aegean island of Amorgus (Amorgos, Greece). Carsidius Sacerdos, accused of aiding an enemy, Tacfarinas, by supplying grain, was acquitted, as was Gaius Gracchus on a similar charge.

Gaius Gracchus, when an infant, had been taken to share his father Sempronius’ exile on the island of Cercina (Kerkennah, off Tunisia). There, as an adult, among exiles and ignorant of the liberal arts, he maintained a precarious living by trading with North Africa and Sicily: yet had still failed to evade the hazard of a great name. And if Aelius Lamia and Lucius Apronius, who had governed North Africa, had not proclaimed his innocence, he would have been dragged down by the notoriety of his unfortunate house and his father’s disaster.

Book IV:XIV Religious asylum, and expulsion of the actors from Italy

This year (AD23) also saw delegations from two Greek communities seeking confirmation of their ancient rights of asylum, the Samians in the Temple of Juno, the Coans in that of Aesculapius.

The Samian case depended on a decree of the Amphictyonic Council, the primary court of justice for all matters in the days when the Greeks founded colonies in Asia Minor and ruled the coast. The Coans had no less ancient a claim, the place gaining additional merit for having sheltered Roman citizens in the temple of Aesculapius, at a time (88BC) when they were being slaughtered throughout the islands and townships of Asia Minor, at the instigation of King Mithridates.

Then, after many and varied complaints in vain from the praetors, Tiberius, eventually raised the question of the licence indulged in by actors: they often incited sedition in public, and debauchery in private: the old Oscan farces, light-hearted amusements for the masses, had reached such heights of virulence and indecency, he claimed, that the authority of the Senate was needed to repress them. The actors were consequently expelled from Italy.

Book IV:XV The trial of Lucilius Capito

This same year (AD23) also brought the emperor further grief, in the death of one (Tiberius Claudius Gemellus) of the twin sons of Drusus, and no less in the death of his friend Lucilius Longus, his comrade in both sad and joyful times, and the only member of the Senate to have shared his retirement to Rhodes (6BC-AD2). Hence a censor’s funeral, despite his being of modest birth, and his statue in the Forum of Augustus, erected at public expense, and decreed by the senators by whom all matters were still discussed.

So much so that Lucilius Capito, the procurator of Asia Minor, was obliged to plead cause before them, having been accused by the province, the emperor strongly asserting that Capito held no authority except over the slaves and revenues of the imperial estates, and that if he had usurped the governor’s powers and employed military force, he had flouted Tiberius’ orders: thus the provincials must be heard.

The defendant was therefore condemned according to the evidence presented. For this judgement, and the punishment accorded Gaius Silanus the previous year, the cities of Asia Minor decreed a temple to Tiberius, Livia, and the Senate. Permission to build was granted, and Nero Julius expressed thanks in the matter, to the senators and his grandfather Tiberius, a pleasing moment for his listeners, whose memory of Germanicus was fresh enough for them to imagine it was his features they saw, his voice they heard. And the youth indeed possessed a modesty and beauty worthy of a prince all the dearer for the danger in which he stood, given Sejanus’ notorious hatred of him.

Book IV:XVI The appointment of the Flamen of Jupiter (Flamen Dialis)

At about the same time, Tiberius raised the matter of the appointment of the Flamen Dialis to succeed the late Servius Maluginensis, while also proposing new legislation, since, by an outdated custom, three patricians, born of parents wedded in the most solemn manner (confarreatio) had to be jointly nominated, of whom only one was selected, yet there were not, as there once had been, sufficient candidates now that the old neglected marriage ritual was adhered to by very few families.

He referred to several reasons for this, the principal one being the disinterest in it shown by both men and women, adding that there was a deliberate avoidance of the difficulties of the ceremony itself, and a parental dislike of the fact that the man granted the priesthood and the woman passing into a flamen’s legal control were no longer under paternal jurisdiction.

Therefore, a senate decree or special legislation was required, in the same manner that Augustus had modified several aspects of hoary antiquity to suit present usage. It was then decided, after considering issues of religion, to make no changes in the stipulations for selection to the flamenship: however, a law was instituted, by which the wife of the Flamen Dialis though subject to her husband’s authority in sacred matters should otherwise be entitled to the same rights as other women.

Maluginensis’ son was duly elected in place of his father. And to enhance the dignity of the offices of religion, and encourage the readier performance of the rituals, twenty thousand gold pieces were voted to the Vestal Virgin Cornelia, who took the place of Scantia, while Livia, on visiting the theatre, was to occupy a place among the Vestals.

Book IV:XVII Tensions regarding the possible succession

In the consulate of Cornelius Cethegus and Visellius Varro (AD24) the pontiffs and, following their example, the priests, while offering prayers for the health of the emperor, also commended Nero Julius and Drusus Julius to the same gods, not so much out of love for the princes as from sycophancy, the absence or excess of which is equally dangerous in a corrupt society. For Tiberius, never reconciled to the house of Germanicus, now found it insufferable that a pair of youths should command the respect due to his years.

Summoning the pontiffs, he enquired whether this addition was due to Agrippina’s entreaties, or her threats. The pontiffs, despite their refusal to acknowledge either, were only mildly admonished, since most of them were either his relatives or leading citizens. However, he gave warning in the Senate that no one should prompt arrogance in impressionable young minds with such premature honours. Indeed, Sejanus was urging him to action, claiming that the state was divided as in a civil war: there were those who declared themselves of Agrippina’s party, and if nothing was done, there would be others; nor was there an alternative to the growing discord but the destruction of one or more of the most energetic of them.

Book IV:XVIII Sejanus attacks Gaius Silius and Titius Sabinus

For this reason, he launched attacks on Gaius Silius and Titius Sabinus. Their previous friendship with Germanicus was fatal to both, and because Silius had commanded a major army for seven years, earned his triumphal insignia (AD15) in Germany, and proved victorious in the war with Sacrovir (AD21), the greater the impact of his fall and the wider the resulting anxiety would spread among others.

Many thought that Silius’ indiscretions had added to his offence, he having boasted immodestly that his troops had maintained discipline while others rushed to mutiny, and that Tiberius could not have held the throne if his legions too had shown a desire for revolution. Tiberius considered his position threatened by such statements, and unequal to the claim made upon it. For services are welcome inasmuch as it seems possible to repay them: go far beyond that and hatred not gratitude is the return.

Book IV:XIX Silius and his wife Sosia Galla condemned

Silius was married to Sosia Galla, who was disliked by Tiberius because of her affection for Agrippina. It was decided they should both be accused and an attack on Sabinus delayed. Varro the consul was let loose, who on the pretext of continuing his father’s feud gratified Sejanus’ ill-intent though dishonouring himself.

Silius asked for a brief adjournment until his accuser relinquished the consulate, but Tiberius refused, saying that it was quite in order for magistrates to impeach private citizens: nor should there be any constraint on the consul’s rights, on whose vigilance they depended ‘to keep the republic from harm’. It was typical of Tiberius to cloak his new-found wickedness with a phrase of our ancestors.

Thus, with great solemnity, as if Silius were being dealt with lawfully, or Varro was a consul of that thing, a republic, the Senate was convened. With the defendant silent, or in offering a defence not hiding whose resentment it was that oppressed him, the charges were presented: his long-hidden complicity in Sacrovir’s rebellion, a victory stained by avarice, and his wife’s involvement. There was little doubt that the extortion charges held, but the whole proceeding was pursued under the treason laws, and Silius pre-empted the guilty verdict by suicide.

Book IV:XX Sosia exiled

However, his estate was not exempted. Though nothing was refunded to the provincial tax-payers, none of whom lodged a claim, the Augustan bounty paid was recovered, and the demands of the treasury itemised. This was the first time Tiberius showed himself so diligent in the matter of another’s property.

Sosia was driven into exile at the instigation of Asinius Gallus, who suggested that half the estate was confiscated, while the rest was given to her children. Opposing this, Manius Lepidus proposed that one quarter be assigned to the prosecutors, according to law, the rest to go to the children.

This Lepidus, I understand, was, for his times, a man of gravity and wisdom: since he often modified the sycophantic harshness of others for the better. Nor did he lack discretion, since he still retained influence and favour with Tiberius to an equal degree.

From this, I am driven to wonder whether the inclinations and antipathies of princes towards each of us are determined by destiny and our situation at birth, or whether something is left to our own will, and that between pure defiance and vile servility we might find a path free of danger or obsequiousness.

But Messalinus Cotta, with no less distinguished a lineage, yet a very different character, proposed a senate decree proclaiming that a magistrate even though innocent himself and knowing nothing of his wife’s guilt should be punished for her wrongdoings in the provinces as if they were his own.

Book IV:XXI Charges against Calpurnius Piso and Cassius Severus

The next charge involved Calpurnius Piso, a man of noble birth and courageous, since, as I have said, he announced in the Senate his retirement from Rome to avoid the gangs of informers and, scorning Livia’s power, had dared to drag Urgulania before the courts, having her summoned from the imperial palace.

At the time, Tiberius treated the matter with civility: but, brooding over his anger, while the initial force of the offence lessened, the memory remained strong. Quintus Granius charged Piso with words spoken in private against the emperor’s majesty, adding that Piso kept poisonous substances in his house, and had worn a sword on entering the Senate House. The last charge was dropped as being too outrageous to be true; he was arraigned for prosecution on the other two, which were greatly elaborated, and was spared the trial by opting for suicide.

There was the matter also of the exiled Cassius Severus, of base origins and dubious life but a powerful orator, who had made so many enemies he was relegated to Crete by verdict of the Senate. There too, by acting in a similar manner, he stirred so many hatreds past and present he was stripped of his possessions, ‘denied fire and water’, and consigned to the rocky island of Seriphos (Serifos, Greece), there to grow old.

Book IV:XXII Plautius Silvanus murders his wife Apronia

Around this time, Plautius Silvanus the praetor, for reasons unknown, threw his wife from a window, and when brought by his father-in-law, Lucius Apronius, before Tiberius gave a confused reply to the effect that he had been soundly asleep and had no knowledge of what had occurred, but thought that his wife must have committed suicide.

Tiberius, without hesitation, went to the house and viewed the bedroom, in which evidence of force employed and resistance made was visible. He referred the matter to the Senate but with a trial date appointed, Urgulania, Silvanus’ grandmother, sent her grandson a dagger, which was taken as a hint from the emperor, given Urgulania’s friendship with Livia.

The defendant, after a vain attempt with the weapon, had his arteries opened. His first wife, Numantina, who had been charged with driving her ex-husband insane by the use of drugs and sorcery, was shortly afterwards judged innocent.

Book IV:XXIII The situation in North Africa

This year (AD24) finally freed the Roman people from the lengthy war with the Numidian Tacfarinas. For the generals leading the earlier campaigns against him, once they thought their actions sufficient for the grant of triumphal insignia, had ceased to harry the enemy. There were now three laurelled statues (of Camillus, Apronius and Blaesus) adorning the city, yet Tacfarinas was still ravaging North Africa, reinforced by the Moors, who during the neglectful youth of Juba II’s son Ptolemy exchanged warfare for subservience to the rule of royal freedmen.

The king of the Garamantes acted as partner in Tacfarinas’ predations and receiver of his plunder, not deploying an army but sending lightly armed warriors, whose numbers were magnified by distance; and every indigent man, and wild character, rushed to join him, the more readily since Tiberius, following Blaesus’ success, had ordered the Ninth legion transferred elsewhere as though hostilities in North Africa had ended, nor had Publius Dolabella dared to retain it, he being proconsul for the year but more fearful of the emperor’s orders than the fortunes of war.

Book IV:XXIV Dolabella moves against Tacfarinas

So, Tacfarinas, after spreading the rumour that other tribes aimed to destroy Roman power and for that reason the Romans were withdrawing gradually from North Africa, while those who remained might be isolated if all who preferred liberty to servitude opposed them, added to his strength, set up camp, and besieged the town of Thubuscum (Tubusuptu, Algeria).

But Dolabella, gathering all available forces, because of the Numidians’ fear of the name of Rome and inability to withstand an infantry line, raised the siege at his first advance and fortified the exposed points. At the same time, he beheaded those Musulamian chieftains who attempted to desert.

Then, because several campaigns against Tacfarinas had shown that a nomadic enemy could not be pursued by heavily-armed troops in a single body, he summoned King Ptolemy and his people, and organised four columns, commanded by legates or tribunes, and bands of raiders with select Moorish leaders, while he himself acted as strategic advisor to them all.

Book IV:XXV The death of Tacfarinas

Shortly afterwards, news came that the Numidians had pitched camp and taken up position near a half-ruined fort, named Auzea (Sour El-Ghozlane, Algeria) which they had at some time previously set alight. They were confident of their position since it was surrounded by large groves of trees.

The light-infantry and cavalry, ignorant of their destination, were sent forward in racing columns. As dawn broke, with fierce shouts and a blast of trumpets they came upon the half-wakened barbarians while the Numidian horse were still tethered or roaming the scattered pastures. The Roman infantry were in close order, the cavalry massed, and every provision made for battle, while the enemy, by contrast, taken by surprise, unarmed, in disarray, and lacking a response, were dragged like cattle to the slaughter, taken and killed.

The Roman soldiers, filled with the memory of past efforts to bring to long-sought battle this elusive foe, wrought, every man of them, a bloody revenge. The word was spread to the maniples to seek out Tacfarinas, well-known from so many engagements: there being no rest from war till that leader was dead.

Tacfarinas, with his retinue slain around him, his son already in chains, and the Romans flooding in from all sides, ran upon the spears, escaping captivity by a death which did not go unavenged, and this brought an end to hostilities.

Book IV:XXVI Dolabella denied triumphal insignia

Tiberius refused the triumphal honours Dolabella sought, as a gesture towards Sejanus lest praise for the latter’s uncle, Blaesus, faded. But that did nothing to embellish Blaesus, and the denial of honours added to Dolabella’s glory: since with a smaller army he had won a reputation by taking important prisoners, killing their leader, and ending the war.

He was attended also, a rare sight in Rome, by a Garamantian delegation, whom that people, stunned by the death of Tacfarinas, and conscious of their errors, had sent to offer redress to the Roman people.

As the campaign had proven Ptolemy to be an ally, a traditional style of honour was revived, whereby a senator was sent to present the ancient Senate gifts to him, an ivory sceptre and the embroidered toga, and greet him as king, ally, and friend.

Book IV:XXVII A slave revolt

That same summer, an incipient slave rebellion throughout Italy was by chance aborted. The author of the revolt was Titus Curtisius, once a soldier in a praetorian cohort, Initially at clandestine meetings in Brundisium (Brindisi) and the surrounding towns, and then by openly displayed manifestos, he had called on the fierce rural slaves from the outlying pastures to seek their freedom, when a gift of providence, three biremes destined for the defence of cargo vessels, arrived.

Cutius Lupus, the quaestor, was also in the area, who by ancient custom had been assigned the trackways: he then commandeered a group of marines and vigorously uprooted the conspiracy at its inception. Staius, the tribune sent hurriedly by Tiberius, with a sizeable force, dragged the leader and his more audacious followers to Rome, where there was already trepidation at the rapidly growing multitude of slaves while the free-born populace dwindled by the day.

Book IV:XXVIII A son accuses his father

In that same consulate, a dreadful example of wretchedness and savagery arose, when a son as prosecutor, father as defendant, appeared before the Senate, both bearing the name of Vibius Serenus (the father having been proconsul of Hispania Ulterior). The latter, dragged out of exile, filthy and squalid and now in chains, faced condemnation by his son, a most elegant youth, with a ready countenance, who spoke of treasonous plots against the emperor, and emissaries of war sent into Gaul, adding that funds had been provided by the ex-praetor, Caecilius Cornutus, who weighed down by anxiety, and with this accusation implying ruin, hastened to commit suicide.

But the defendant, his spirit unbroken, facing his son, shook his chains and replied by summoning the gods in vengeance, crying out that as for himself they might return him to his exile, where he might live far from such evil manners, and as for his son let retribution find him when it would. He insisted that Cornutus had been innocent, made fearful without cause; and that would be easily evidenced if the others were named: for he had certainly not contemplated rebellion and the murder of an emperor with only a single ally.

Book IV:XXIX Tiberius relentless

The son then named Gnaeus Lentulus and Seius Tubero, to the emperor’s great embarrassment, since two prominent citizens, close friends to himself, Lentulus far gone in years, Tubero in failing health, were charged with armed affray and troubling the peace of the State. However, these two were promptly exonerated.

In the case of the father, his slaves were tortured, which proved unhelpful to the son, who tormented by his conscience and fearful of mass hostility that threatened him with prison, the Tarpeian Rock, or the parricide’s fate (of being thrown into the sea sewn in a sack with a dog, cockerel, viper and ape) fled the city.

But, dragged back from Ravenna, he was forced to continue the prosecution, Tiberius not concealing his former hatred of the exile; for Serenus, after the sentencing of Libo, had written to the emperor complaining that his efforts had gone unrewarded, ending on too defiant a note to strike safely with a proud and easily offended recipient.

Tiberius now returned to that matter, eight years later, invoking various offences during the intervening period, even though the firmness of the slaves under torture had seemingly thwarted him.

Book IV:XXX Tiberius supports the informers

When views were expressed that Serenus should be punished according to ancient custom, Tiberius interceded to restrain the hatred expressed. He also rejected Asinius Gallus’ proposal of confinement on the island of Gyarus (Gyaros, Greece) or Donusa (Donoussa, Greece), reminding him that both islands lacked fresh water, and that if you grant life you must also grant the means to live. The elder Serenus was therefore returned to Amorgus.

And because Cornutus had died by his own hand, it was proposed that the accuser’s reward should be forfeited if a defendant charged with treason took his own life before the completion of his trial. They were proceeding to a vote, when Tiberius, with greater asperity and frankness than was his custom, complained on behalf of the accusers, that the law would be rendered null and void, the State on the verge of destruction: it were better to abolish the rule of justice than remove its guardians.

So, the informers, a tribe of men invented for the nation’s ruin, never sufficiently restrained even by penalties, were now lured on by rewards.

Book IV:XXXI The contrasting sides of Tiberius’ nature

This pattern of gloomy events was interrupted by a relatively optimistic one, when Tiberius showed mercy to Gaius Cominius, a Roman knight convicted of a poetical satire on himself, yielding to the pleas of Cominius’ brother, who was a senator.

This action of Tiberius aroused all the more wonder that seeing the kinder road, and that his reputation was improved by showing clemency, he preferred the harsher one. Nor did he err through thoughtlessness; nor is it anything but obvious when an emperor’s actions are praised with sincerity as opposed to a feigned enthusiasm. And indeed, he to whom oratory was alien and speech seemingly a struggle was all the more prompt and eloquent when he was merciful.

However, when Publius Suillius Rufus, formerly Germanicus’ quaestor, was sentenced to banishment from Italy charged with corrupt legal practices, Tiberius moved, and with such vigour that he even swore on oath that the interests of the State required it, that Suillius be deported to an island,. Criticised severely at the time, his decision accrued praise on Suillius’ later return, when the man was seen by the following generation, all-powerful and venal under Claudius, exploiting that emperor’s friendship, and never for the better.

The same mode of exile was to be inflicted on Firmius Catus, a member of the Senate, for falsely accusing his sister of the crime of treason. It was Catus, as I have said previously, who drew Libo into a trap and then ruined him with the evidence. Tiberius, remembering that service, though offering other reasons, saved Catus from exile, though not objecting to his expulsion from the Senate.

‘Emperor Tiberius’

Joos Gietleughen (Dutch, 1559)

The Rijksmuseum

Book IV:XXXII Not all history is filled with glorious events

Many of the events I have related and have yet to relate may perhaps seem trivial and not worth the mention; I am not unaware of that, but my annals in no way compare with the works of those authors who recorded the ancient history of the Roman people. They told, and freely digressed regarding, immense wars, the storming of cities, the downfall and capture of kings, or if they turned to matters at home, conflicts between consul and tribune, land laws and corn laws, the quarrels between the masses and the aristocracy.

Mine is a narrow and inglorious labour; for what I speak of was an age of unbroken or barely-troubled peace, dull events in Rome, and an emperor indifferent to the expansion of empire. Yet it may not be without benefit to investigate things, slight at first sight, which often set in motion great happenings.

Book IV:XXXIII Modern and ancient times

For every nation or city-state is governed by the people, the aristocracy, or certain individuals: a government chosen from among these yet united is of a form easier to praise than bring about, or if brought into being it can scarcely be long-lasting.

Thus, when formerly the masses proved strong, or alternatively the nobility held power, it was necessary to know, on the one hand, the nature of the populace and how to control its influence, while on the other hand, those who knew by heart the inmost character of the senate and the aristocracy were thought the shrewdest and wisest of their age. So also, regarding this changed situation, where the Roman State is nothing other than one-man rule, it may serve a purpose to collect and relate these things. For few discern right from wrong, the expedient from the ruinous; the majority learn from others’ experience.

Yet while such matters bring profit, they are poor in entertainment. For the location of peoples, the vicissitudes of battle, leaders dying gloriously, such things hold the reader and excite the mind: while I tell of brutal instructions, continual accusation, treacherous friendships, innocence destroyed, of many causes leading to the same ends, everywhere a sameness and satiety of things.

And then, ancient authors have few detractors, and it is no matter whether you praise with more enthusiasm Roman or Carthaginian arms: yet many descendants of those subjected to punishment or disgrace in Tiberius’ reign, are still alive. And even if the families themselves are extinct, you will nevertheless find those who, from likeness of character, consider the wrongdoings of others a reproach aimed at themselves. Even glory and virtue create enemies, in revealing their opposites by too sharp a contrast. But I will return to my labours.

End of the Annals Book IV: I-XXXIII