Cornelius Tacitus

The Annals

Book III: XXXV-LV - Rebellion in Gaul

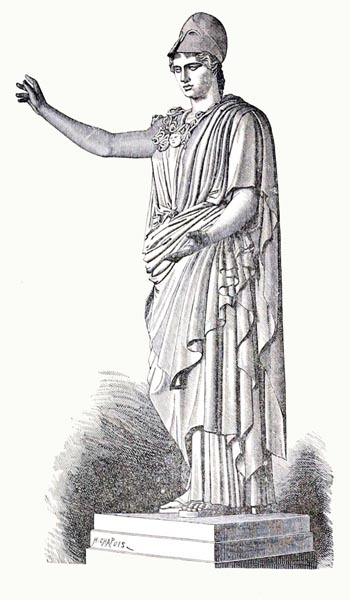

‘Pallas of Velletri’

History of Rome and the Roman people, from its origin to the establishment of the Christian empire - Victor Duruy (1811 - 1894) (p630, 1884)

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2017 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book III:XXXV Blaesus nominated to North Africa.

- Book III:XXXVI Use of the emperor’s portrait to claim immunity.

- Book III:XXXVII Drusus gains credit.

- Book III:XXXVIII Disturbances in Thrace.

- Book III:XXXIX Publius Vellaeus pacifies Thrace.

- Book III:XL Rebellion in Gaul.

- Book III:XLI Action against the rebels.

- Book III:XLII The death of Julius Florus.

- Book III:XLIII Silius takes command against the Aedui.

- Book III:XLIV The view from Rome.

- Book III:XLV Silius advances on Autun.

- Book III:XLVI The death of Sacrovir.

- Book III:XLVII Tiberius acknowledges victory.

- Book III:XLVIII Tiberius commemorates Sulpicius Quirinus.

- Book III:XLIX Accusations against Clutorius Priscus.

- Book III:L Manius Lepidus speaks against the sentence.

- Book III:LI The execution of Priscus.

- Book III:LII AD22: The problem of excessive private expenditure.

- Book III:LIII Tiberius addresses the issue.

- Book III:LIV He declines to intervene.

- Book III:LV Tacitus reflects on the outcome.

Book III:XXXV Blaesus nominated to North Africa

At the next Senate session, Tiberius, after offering an oblique reproof to the Fathers, by letter, for referring a matter which was their total responsibility to their emperor, nominated Manius Lepidus and Junius Blaesus as alternative choices for the proconsulate of North Africa. Both were then given a hearing.

Lepidus earnestly excused himself, due to the state of his health, the age of his children, and his now marriageable daughter, while it was understood, though remained unsaid, that Blaesus, as Sejanus’ uncle, was the stronger applicant.

Blaesus responded with an apparent refusal, but far less earnestly, and was encouraged to accept by a unanimous show of support.

Book III:XXXVI Use of the emperor’s portrait to claim immunity

Next, a matter arose which had been the subject of much private complaint. It was a growing practice among the mob to freely incite hatred and abuse of decent citizens, while claiming immunity from prosecution by clasping hold of a statue of Tiberius. Patrons and owners lived in fear of their freedmen and even their slaves, if they raised voice or hand against them.

Accordingly, Gaius Cestius expressed the view that though emperors were the equivalent of deities, only rightful petitions were heard by the gods, and none should seek sanctuary in the Capitol or any other temple in order to further a crime. All law was abolished, its foundations uprooted, if Annia Rufilla, whom he had convicted in court of fraud, could abuse and threaten him in the Forum, on the very steps of the Senate House, while he dare not invoke the law because of the effigy of the emperor with which she confronted him.

A clamour, spelling out similar, and sometimes more serious, occurrences arose around him, and there were calls to Drusus to exact exemplary punishment, until he finally commanded her to be summoned and, after sentencing, imprisoned in the public cells.

Book III:XXXVII Drusus gains credit

Also, two Roman knights, Considius Aequus and Caelius Cursor, who had raised false charges of treason against the praetor Magius Caecilianus, were punished by Senate decree at the emperor’s insistence.

In both the above cases, the result was credited to Drusus, his presence in Rome at gatherings and in conversation having a mitigating effect on his father’s secret purposes. His very indulgences were far from unpopular: it being regarded as better for him to summon up buildings by day and banquets by night, than to live alone without pleasurable distractions, lost in gloomy vigil amid dark concerns.

Book III:XXXVIII Disturbances in Thrace

For neither Tiberius nor his informers grew weary. Thus, Ancharius Priscus accused Caesius Cordus, the proconsul of Crete and Cyrene, of extortion, adding the usual charge of treason which now accompanied every such accusation.

Antistius Vetus, a nobleman of Macedonia, having been acquitted of adultery, Tiberius reprimanded the judges and summoned him back to stand trial for treason, as a troublemaker mixed up in Rhescuporis’ scheming who had meditated war against us after the murder of Cotys. The accused was ‘denied fire and water’, his place of exile being specified as ‘not too near Macedonia or Thrace’.

For Thrace, unused to our ways, was in a state of discord, power having been divided between Rhoemetalces II and Cotys’ children, who as minors were under the tutelage of Trebellenus Rufus, he no less than Rhoemetalces being accused of allowing the injury to their countrymen to go unavenged.

Three powerful tribes, the Coelaletae, Odrysae and Dii, took up arms, under different leaders equally undistinguished by birth, a situation which prevented their uniting to wage serious warfare. One group caused havoc nearby, another crossed the Haemus mountains to raise the remote clans, while the best organised and most numerous besieged the king in the town of Philippopolis (Plovdiv, Bulgaria), re-founded by Philip II of Macedon.

Book III:XXXIX Publius Vellaeus pacifies Thrace

On hearing of this, Publius Vellaeus (commanding the nearest military force) sent the light infantry and auxiliary cavalry against these roving bands who were after plunder or fresh recruits, while he himself led the strongest units to raise the siege.

All they attempted at once succeeded, the raiders were killed while dissent erupted among the besiegers, and the king opportunely vanished as the legion arrived. Neither engagement nor battle is a worthy term for an action where poorly-armed men and fugitives were massacred without a drop of Roman blood being shed.

Book III:XL Rebellion in Gaul

In that same year (AD21), a rebellion began among the heavily indebted communities of the Gallic provinces, promoted most fiercely by Julius Florus of the Treviri, and Julius Sacrovir of the Aedui. Both were well-born, their ancestors having been awarded Roman citizenship at a time when such action was rare and purely the result of merit.

To their secret councils they admitted the boldest spirits and those for whom poverty and fear of prosecution made of crime a necessity, agreeing that Florus should rouse the Belgae, Sacrovir the neighbouring Gauls.

So, in public sessions and among the crowd, they spoke seditiously regarding the endless tribute demanded, the burden of interest, the cruelty and arrogance of the provincial governors, and the discord among the legions following the news of Germanicus’ downfall. This was the perfect moment, they said, to regain their liberty, if their listeners would only consider their own strengths versus Italy’s weaknesses; its urban unwarlike people, its armies only powerful because of the foreigners it enlisted.

Book III:XLI Action against the rebels

There was barely a community left in which the seeds of insurrection had failed to take hold; but the first uprising was among the Andecavi and the Turoni. Of these the Andecavi’s rebellion was crushed by Acilius Aviola, the legate, who called on the services of a cohort on garrison duty at Lyon. The Turoni were quelled by Aviola again, with a legionary force sent from Lower Germany by Visellius Varro the legate, and supported by various Gallic chieftains who brought auxiliaries in order to mask their defection from Rome and then reveal it at a more favourable time for themselves.

Sacrovir was visible urging them to fight for Rome, bare-headed to reveal his courage, though captives claimed he sought recognition to avoid being showered with spears. Tiberius, consulted on the matter, was dismissive of the evidence, and by his indecision prolonged the war.

‘Scene from the Gallic Wars’

Théodore Chassériau (French, 1819 – 1856)

The Met

Book III:XLII The death of Julius Florus

Meanwhile Florus pursued his strategy, trying to entice a cavalry troop, enrolled at Treves and under our command and control, to initiate conflict by killing Roman businessmen; a few of the horsemen being seduced, but the majority staying loyal.

In addition to these few, a crowd of debtors and clients took up arms, and were heading for the forested area known as the Ardennes when the legions from Upper and Lower Germany, sent against them by Visellius and Gaius Silius respectively, advancing by separate routes, blocked their way.

Julius Indus, from the same area, at odds with Florus and all the more eager to be of use in the campaign, was sent ahead with crack troops, and dispersed the as yet disorganised rabble. Florus himself eluded pursuit by taking to various unsafe hiding-places, dying by his own hand on catching sight of the soldiers who commanded his every escape route.

Thus the uprising among the Treviri was ended.

Book III:XLIII Silius takes command against the Aedui

Among the Aedui, there was greater trouble, due to the greater resources of the area and its distance from any restraining force. Sacrovir occupied the tribal capital, Autun (Augustodunum), with his armed cohorts, aiming to enlist the support of those sons of the Gallic nobility who were pursuing their liberal studies there, and by that token their parents and relatives. At the same time, he distributed weapons, manufactured in secret, to the youths.

He had forty thousand followers, a fifth of them armed like legionaries the rest with hunting spears, knives and whatever other weapons belong to the chase. To these men were added slaves destined for the gladiatorial fights, clad in the full coats of mail customary in that nation. Such men are called cruppelarii, their armour unwieldy in inflicting blows, almost impenetrable when receiving them.

These forces steadily increased, the neighbouring districts not yet openly supportive but enthusiasm evident among individuals, while the Roman generals quarrelled, arguing over their separate claims to control the campaign.

Ultimately Visellius Varro, weakened by age, gave way to Silius the younger man.

Book III:XLIV The view from Rome

In Rome, it was said that not only the Treviri and Aedui had rebelled but all the sixty-four Gallic tribes, the Germans had joined their confederation, the Spaniards were wavering, and, as is the way with rumours, was all the more readily believed. The best grieved, concerned for the State, but many, hating the present order and eager for change, rejoiced at their own danger, and cried out against Tiberius for spending time on the scribblings of informers in such troubled times: was Sacrovir likely to stand trial in the Senate for treason? Men had finally emerged who would halt those murderous letters by force! War was a welcome exchange for this miserable peace!

Tiberius’ was all the calmer in his studied unconcern, altering neither his routine nor his manner, but acting in the usual way throughout, either from profound reticence, or because he knew the disturbances to be more contained and less serious than reported.

Book III:XLV Silius advances on Autun

Meanwhile, Silius, advancing with two legions, sent forward auxiliary troops and sacked the villages of the Sequani, on the far frontier with the Aedui and their armed allies. He then marched at full speed on Autun, the standard-bearers competing with each other and even the common soldiers protesting against any pause for the usual respite or night halt; shouting only to see the enemy and be seen: that would be enough for victory.

At the twelfth milestone (from Autun) Sacrovir and his forces appeared to view on an open space of ground. His mail-clad troops formed the front line, his cohorts the wings, his less well-armed followers the rear. He himself, on a fine steed, amongst the chieftains, addressed them, reminding them of the Gauls’ former victories, the reverses they had inflicted on the Romans: how beautiful their freedom if they won, how intolerable their servitude should they be beaten once more.

Book III:XLVI The death of Sacrovir

His speech was brief and brought little joy: since the ranks of legionaries were drawing near, and his ill-disciplined provincials, unused to warfare, could scarcely credit their ears and eyes.

Silius, on the other hand, though expectation had left no need for exhortation, shouted out that it was almost an insult to his conquerors of Germany to be sent against these Gauls instead of a real enemy. ‘Not long ago,’ he cried, ‘one cohort destroyed the rebellious Turoni, one cavalry troop the Treviri, and a few squadrons of our army the Sequani. The greater their wealth in gold, the more excessive their pleasures, the less warlike the Aedui: rout them but preserve the fugitives.’

There was a great clamour at this, the cavalry encircling the enemy, while the infantry charged their front. The flanks proved no obstacle, though the mail-clad troops caused a brief delay, their armour resisting javelin and sword: but the legionaries grasping pick and axe struck through iron and flesh as if demolishing a wall, while others with pole and pike downed the unmoving masses and left them lying, inert as the dead, making no effort to rise once more.

Sacrovir, with his most loyal men, first made for Autun, then, anxious to avoid surrender, to a villa nearby. There he died by his own hand, the others by mutual exchange of blows; the house, burnt above them, making a funeral pyre of all.

Book III:XLVII Tiberius acknowledges victory

Now Tiberius at last wrote to the Senate announcing the beginning and end of the war, neither hiding nor embellishing the facts, but stating that the loyalty and courage of his generals, and his own strategy had sufficed.

At the same time he explained why neither he nor Drusus had left for the front, extolling the extent of empire, and how unfitting it would have been for the emperor to leave the capital, which ruled all, because of disturbances in a town or two. Now, not being driven to do so by anxiety, he would go and examine the matter in person, and seal the peace.

The senators decreed vows for his return, sacrifices and other honours. Only Cornelius Dolabella, trying to outdo the rest, took sycophancy to the point of absurdity, by proposing that Tiberius should enter the city from Campania to an ovation. A letter from Tiberius then followed, proclaiming that he was not so destitute of glory, having subdued some of the fiercest nations and received or rejected so many triumphs in his youth, that now in his riper years he should seek an empty honour in progressing through the suburbs.

Book III:XLVIII Tiberius commemorates Sulpicius Quirinus

At around this time, Tiberius requested of the Senate that the death of Sulpicius Quirinius be marked by a public funeral. Quirinius, who hailed from the municipality of Lanuvium (Lanuvio) had no connection with the old patrician family of the Sulpicii, but as an energetic military man and eager servant he had won a consulate under the divine Augustus, and a little later the insignia of a triumph for capturing the Homonadensian strongholds in Cilicia, and was appointed Gaius Caesar’s advisor in Armenia.

He was also attentive to Tiberius during the latter’s time in Rhodes: as Tiberius now informed the Senate, praising Quirinius’ good offices to himself, while criticising the memory of Marcus Lollius whom he condemned as the instigator of Gaius Caesar’s perverse and argumentative attitude.

But the rest found little pleasure in recollecting Quirinius, given his intent, as I have mentioned, to ruin Lepida, and his vile abuse of power in old age.

Book III:XLIX Accusations against Clutorius Priscus

At the end of that year (AD21), a Roman knight, Clutorius Priscus, who after penning a celebrated poem bemoaning the death of Germanicus had been given a sum of money by Tiberius, was subject to accusations by an informer. It was said that during Drusus’ illness he had claimed to have composed another poem which in the event of Drusus’ death might attract an even greater reward.

Clutorius had boasted idly of this at Publius Petronius’ house, in the presence of Petronius’ mother-in-law Vitellia, and other noblewomen. When the informer appeared, the rest were terrified into giving evidence, Vitellia alone asserting that she had heard nothing. However the witnesses testifying to the fatal event were regarded as more credible, and the death penalty was invoked against the defendant, at the prompting of the consul designate, Haterius Agrippa.

Book III:L Manius Lepidus speaks against the sentence

Manius Lepidus, opposing this, began in the following manner: ‘If, Senators Elect, we consider only the single matter of that criminal utterance by which Clutorius Priscus sullied his own soul and the ears of men, no prison cell, no rope, not even a slave’s crucifixion suffices for him. Yet if, though vice and crime are limitless, the sentence and the remedy might be modified by the emperor’s clemency, and your and your ancestors’ precedents, and if there is a difference between stupidity and wickedness, between evil-speaking and evil-doing, there is the opportunity for a judgment which neither lets this man’s sin go unpunished, nor leaves us dissatisfied by either the depth of our compassion or our harshness.

I have often heard our emperor complain when someone by suicide forestalled his leniency. Clutorius’ life is still whole, the preserving of which presents no danger to the State, while the taking of it sets no great example. His literary efforts are as filled with foolishness as they are idle and transient; nor could anything grave and serious be feared in one who betrays his own shameless effusions to amuse not men but childish women. Banish him from Rome, sequestrate his goods, deny him “fire and water”: that is what I propose, as the treason laws prescribe.’

Book III:LI The execution of Priscus

Only the ex-consul Rubellius Blandus agreed with Lepidus: the rest seconded Agrippa’s judgement, Priscus being led to the cells and immediately executed. Tiberius, with a customary display of ambiguity, found fault with this action, in the Senate.

While he lauded the sense of duty of those who avenged so keenly an insult, however slight, to their head of State, he deprecated such hastiness in regard to a merely verbal offence. He praised Lepidus, but failed to blame Agrippa.

It was subsequently agreed that no Senate decree should become operative by being entered to the Treasury (at the Temple of Saturn) before the tenth day, and the life of a condemned prisoner should be spared until then.

Nevertheless, the Senate had no freedom to reverse sentence, nor was Tiberius any the more forgiving in the interim.

Book III:LII AD22: The problem of excessive private expenditure

There followed the consulate (AD22) of Gaius Sulpicius Galba and Decimus Haterius, a year of calm abroad, but concern at home that severe measures might be taken against the excessive private expenditure now rampant, the purchase of everything on which money could be squandered. It was the facilities for public wining and dining, a subject of endless gossip, rather than other more serious examples of lavishness the costs of which could mostly be hidden, that led to anxiety lest an emperor wedded to outdated frugality adopt harsher strictures.

For when Gaius Bibulus raised the issue his fellow aediles agreed that the rules against excessive consumption were being ignored, and the daily increase in prices of essentials could not be checked by any easy remedy, and the Senate when consulted passed the whole matter on to the emperor. Yet Tiberius after repeated consideration as to whether such widespread excesses could be curbed, and whether doing so now might prove a greater public evil, and what loss of dignity might be caused by a law that could not be enforced, or if enforced might bring scandal and disgrace on his noblest subjects, in the end composed a letter to the Senate, along these lines:

Book III:LIII Tiberius addresses the issue

‘Perhaps on other matters, Senators Elect, it is more expedient to raise and discuss in my presence any public issue on which I am to comment; but in this matter it is better my gaze is elsewhere, lest through your noticing the anxious looks of any member who might be charged with shameful excess, I myself might see and surprise them, so to speak.

If those active individuals, the aediles, had taken me into their confidence beforehand, perhaps I might have persuaded them to ignore long-matured and entrenched failings rather than pursue them and reveal openly an offence we are powerless to combat. But they have done their duty, such that I desire every magistrate as thorough in theirs.

For myself, it is neither right for me to remain silent nor helpful for me to speak out, since I fulfil the role neither of aedile, praetor nor consul. Something nobler and more extensive is required of an emperor; yet while everyone takes credit, rightly, for success, when all are in error one alone bears the blame. What then should I try to prohibit first, in retreating to a past way of life? The endless extent of our villas? The number and diversity of our slaves? Our masses of gold and silver? Our miraculous bronzes and paintings? The promiscuous attire of both men and women, and those feminine extravagances by which our wealth passes to foreign and hostile countries?’

Book III:LIV He declines to intervene

‘I am not unaware that these things are condemned at dinner-parties and gatherings, amid demands that some limit be set; but let a law be passed and punishment decreed, and those same voices will cry that the State is under threat, that the end of all magnificence is at hand, that no man is innocent of this crime. Yet old, enduring bodily ills can only be checked by harsh and bitter remedies: a sick and feverish mind, both corrupted and corrupting, needs cures no less severe than the passions which inflamed it.

All the laws created by our ancestors, all those the divine Augustus decreed, are lost; some to oblivion; some, to our greater shame, through contempt; granting excess its freedom. For if you desire something not as yet forbidden, you fear lest it may be; but once you have crossed the line with impunity, you are beyond fear or shame. Why was moderation once the rule? Because everyone controlled themselves; because we were citizens of a single city; nor were those temptations present even when we ruled Italy. By foreign conquest we learned to squander others’ wealth, by those at home our own.

What a small matter this which the aediles warn about! How trivial, it must be thought, if you look around you! Yet no one mentions, by Hercules, that Italy requires foreign imports, that the survival of the Roman people depends daily on the vagaries of wind and tide. If the provincial harvest ever failed to supplement that of our own landowners, our slaves and fields, no doubt our parks and villas would sustain us! That, Senators Elect, is what troubles your emperor; that is the issue which if neglected, will sink the State.

The remedy for other matters lies with each of us: out of shame, let us change for the better; the poor among us from necessity, the rich from satiety. Or if the magistrate exists who can promise sufficient energy and harshness in dealing with the matter, I will grant him my praise and confess my burdens lightened, yet if he is keen to denounce such failings and then, after reaping the glory, make trouble which he leaves to me, then, believe me, Senators Elect, neither am I eager to seek criticism. I undertake matters grievous and often iniquitous, for the sake of the State, but when they are idle, useless and of benefit neither to you nor myself, I rightly beg to be excused.’

Book III:LV Tacitus reflects on the outcome

When Tiberius’ letter had been given a hearing, the aediles were exempted from any such task, and in fact the luxurious banquets which had been indulged in at lavish expense throughout the century between the naval battle at Actium (31BC) and the conflict that brought Servius Galba to power (AD68) gradually fell out of fashion. It is interesting to seek out the causes of that change.

Once, rich families or those of illustrious distinction were ruined by a passion for magnificence. For its was still acceptable to court or be courted by the people, our allies and dependent royalty, such that the greater the wealth, residence and appurtenances the more illustrious a man’s reputation and clients.

After an age of savage executions, when great fame meant death, the survivors chose a wiser path. At the same time, newcomers from the municipalities, colonies, and even the provinces were frequently appointed to the Senate, and brought with them their own fashion of plain-living, and though many reached an affluent old age through effort or good luck their previous attitude persisted. Yet the chief proponent of a stricter morality was Vespasian, himself of the old style regarding dress and table.

Hence, respect for the emperor, and the love of emulation, proved stronger than laws and punishment. Or perhaps there is something akin to a natural cycle in all things, such that as the seasons rotate, so does our manner of living. Nor was everything better in the past, our own age too has seen many noble and artistic achievements, that posterity might well imitate. May this true competition between ourselves and our ancestors long continue.

End of the Annals Book III: XXXV-LV